1. Introduction

The 2022 global outbreak of mpox caused by monkeypox virus (MPXV) marked a turning point in the disease’s epidemiology. Previously considered a rare zoonosis, endemic to Central and West Africa, MPXV expanded rapidly into new geographies and transmission networks.

In the last few years, MPXV was described as the most significant species for humans among Orthopoxvirus genus. Following variola virus (VARV) eradication, concern was raised that MPXV might fill the vacant epidemiological niche previously occupied by VARV[

1,

2,

3]. Since 2017, the incidence of mpox in non-endemic areas has increased, and from May 2022 until August 2025, over 150000 confirmed cases were reported across more than 137 countries, most of which had no previous history of MPXV transmission[

4,

5], driven predominantly by human-to-human spread within networks of close or sexual contact[

3,

6].

The MPXV genome is a double-stranded DNA molecule, featuring two identical oppositely oriented regions of ~ 6400 bp in length, known as inverted terminal repeats (ITR)[

6,

7]. These genomic regions contain genes assumed to be involved in immune evasion[

8,

9]; conversely, genes essential for viral replication are located in the highly conserved core region[

6,

7].

Phylogenetically, MPXV comprises two major clades[

10]: clade I (with its subclades Ia and the new Ib, which emerged in 2023 in the South Kivu province), historically restricted to animal populations in Central Africa, and clade II (with its subclades IIa and IIb), restricted to West Africa[

11,

12]. On August 14, 2024, a public health emergency of international concern was declared due to the increase in mpox cases caused by clade I in the Democratic Republic of Congo and its spread to neighboring countries[

5]. Clade Ia was primarily associated with zoonotic transmission from animal reservoirs, but emerging evidence showed that human-to-human transmission has been sustained. In contrast, epidemiological and sequencing information showed that clade Ib MPXV was predominantly associated with human-to-human transmission[

5].

The 2022 outbreak was attributed to clade IIb, lineage B.1[

13], and genomic surveillance revealed a surprisingly high number of mutations, including over 40 single-nucleotide substitutions compared to the closest 2018–2019 clade IIb strains. Many of these were APOBEC3-mediated (GA>AA and TC>TT), suggesting ongoing adaptive evolution within human hosts[

6].

In the terminal regions of poxviruses genomes, gene gain and loss are key drivers of their evolution and adaptation to the hosts[

14,

15]. Studies have shown that deletions were linked to increased human-to-human transmission[

16], and gene copy number variation has been identified as a factor able to modulate viral fitness[

17]. Moreover, characterized MPXV genomes from the 2022 outbreak have chimeric sequence architectures (mosaicisms), copy-number variation in tandem repeats, and significant linkage disequilibrium among SNPs, findings that strongly suggest natural recombination acts alongside mutation and selection in shaping MPXV genomic diversity and its capacity for adaptation to new hosts[

18].

Viral genomes often contain low-complexity regions (LCRs), defined as stretches of biased or repetitive sequence with limited nucleotide diversity. These regions frequently harbor short tandem repeats (STRs), i.e. short nucleotide motifs repeated in direct succession, whose copy number can vary among genomes. STRs have been described across a broad range of viruses[

19,

20,

21,

22,

23], where they have been linked to genome plasticity, regulation of gene expression, host adaptation, and even differences in virulence or immune evasion. Despite growing evidence of tandem-repeat variability, STRs have not yet been fully characterized in MPXV. STRs enrichment in low-complexity domains of MPXV suggests they could likewise contribute to viral diversity via mechanisms such as modulation of expression, structural genome plasticity, or genome length variation. A recent study showed that STRs are widespread and highly variable across strains, notably concentrated in the ITRs, with copy-number differences even among closely related isolates[

6]. Such features suggest STRs may function as evolutionary “tuning elements,” fostering phenotypic variability in surface proteins and immune modulators with potential consequences for viral fitness, transmission, and immune escape[

6].

In this study, we investigated the genomic dynamics of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), STRs, and low complexity regions in MPXV genomes collected during the 2022 outbreak in Italy. We applied a longitudinal design, analyzing clinical specimens collected at multiple timepoints, from diagnosis through follow-up, across different biological matrices.

2. Results

2.1. QC, Read Alignment, and Hybrid Assembly

Sequencing yielded an average of 2’029’939 Illumina and 273’023 ONT reads. Sequencing metrics, QC, and coverage against the RefSeq NC_063383.1 are reported in Supplementary material,

Table S1. To better recapitulate the repeated sequences number and to increase the accuracy of the STR analysis, hybrid genome assemblies were built for each sample by combining short and long reads. The hybrid assemblies generated on average 4 contigs belonging to MPXV, covering 97% of the NC_063383.1 reference sequence.

2.2. Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms

To explore patterns of viral mutation across samples, we conducted two complementary analyses: i) exploration of novel nucleotide substitutions across patients, aimed at identifying potential convergences, and ii) an intra-patient comparison of distinct biological matrices, to assess intra-host variability. Notably, P6, P10, P11, and P12 shared a pattern of five novel mutations (C101983T, G28334A, C162816T, C170573T, and C72215T), suggesting close phylogenetic relatedness since all samples belong to the B.1.7 lineage. Similarly, patients P3 and P4 shared three unique substitutions (G37152A, C184829T, and C152445T). We observed intra-host variability in the number of novel SNPs across different sample types, despite all matrices belonging to the same individual and timepoint. In P3, the skin lesion showed a higher number of novel mutations followed by the pharyngeal swab, and the saliva, which exhibited a reduced SNP profile. Specifically, mutations such as G37152A were consistently detected across all matrices, the genital lesion carried univocally the G150394A in the pharyngeal sample. Similarly, in P4, while most matrices carried the full set of novel SNPs, the abdominal skin lesion additionally carried C1092T, G171341T and G171341T.

Figure 1 shows the localization of the identified SNPs along the MPXV genome. Detailed results are reported in Supplementary material,

Table S2.

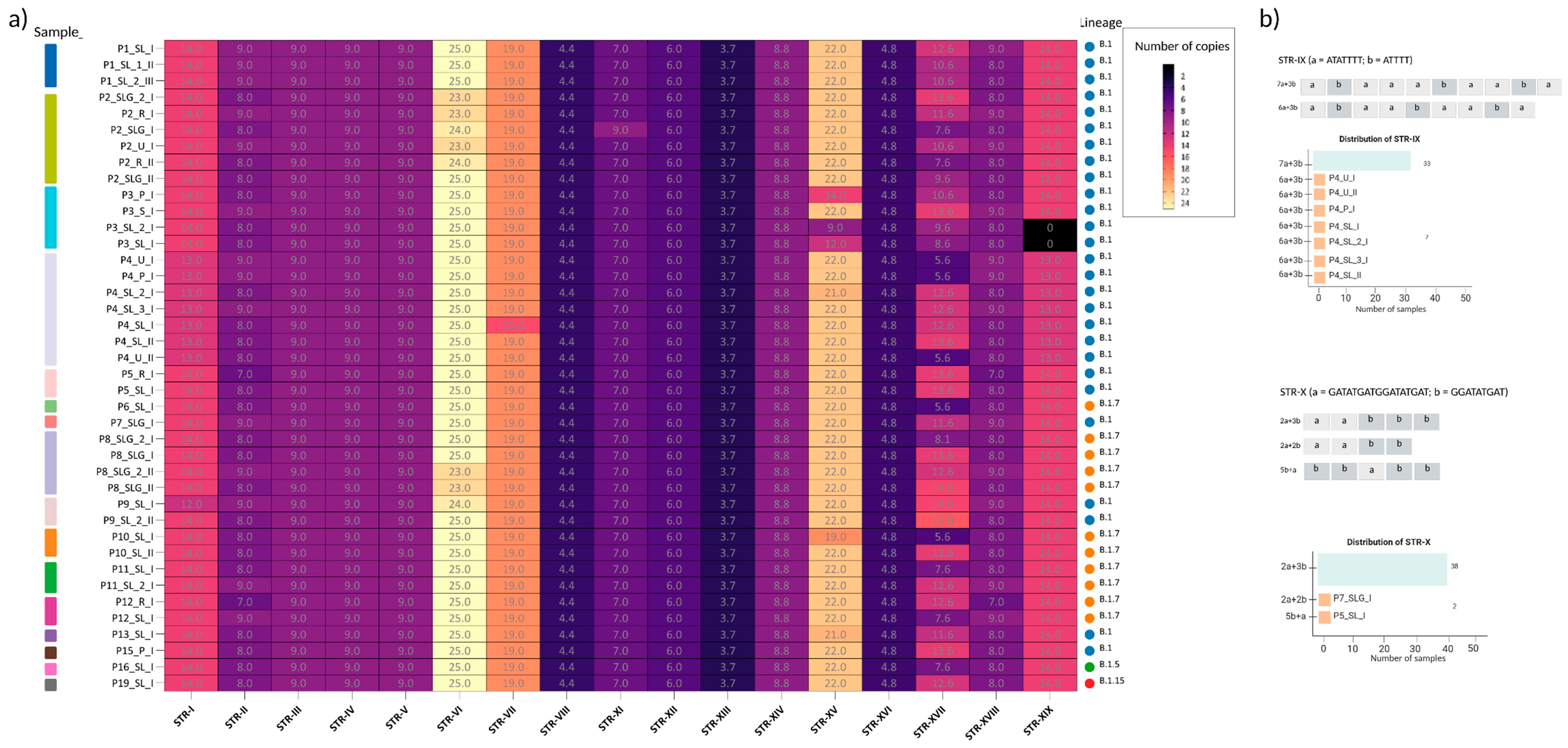

We systematically analyzed STRs using Tandem Repeat Finder. A total of 19 STRs (STR-I to STR-XIX) were identified (

Table 1). The 19 STR regions were detected across all samples, and varied in length from 9 bp to 144 bp, with repeat units ranging from mononucleotide stretches (e.g., STR-I, STR-III, STR-IV, STR-V, STR-VI, STR-XI and STR-XIX) to more composite motifs such as STR-IX and STR-X. The number of repeats spanned from 3.7 (STR-XIII) to 25 (STR-VI), with different levels of conservation across samples. Interestingly, STR-I and STR-XIX, as well as STR-II and STR-XVIII were located in the ITRs, where they were present as identical copies in reverse-complementary form. 9 STRs were located in proximity to annotated MPXV genes (OPGs), either upstream, downstream, or within ORFs. Most intragenic STRs (e.g. STR-III, IV, V, VIII, XIII, XIV, XVI) were highly conserved across patients and timepoints.

By contrast, STR-X, although stable in copy number, displayed changes in repeat architecture (e.g. 2a+3b to 2b+a+3b configurations), highlighting a high structural plasticity at these loci. Non-intragenic loci such as STR-II, STR-XV, STR-XVII and STR-XIX were the most variable, showing larger fluctuations in repeat copy number. The identified STRs and their corresponding repeat numbers are displayed in

Figure 1. A comprehensive overview of the STR loci is provided in

Figure 2: loci displaying simple repeat motifs are reported in

Figure 2a, while loci in which we detected rearrangements in the architecture, are presented in

Figure 2b.

2.3. Intra-Host STRs Variation Across Matrices and Timepoints

We investigated the distribution of the 19 identified STRs across the 40 sequenced matrices. Overall, STR profiles were highly conserved across patients and sample types. A large number of STR loci, including STR-III, STR-IV, STR-V, STR-VIII, STR-XII, STR-XIII, STR-XIV, and STR-XVI were unaltered across all samples, and STR-VI showed only minor fluctuations (23–25 repeats) in a subset of matrices. Some other STR loci presented a more variable pattern across samples. For instance, P3 exhibited copy-number variation without locus loss, with a marked reduction of STR-XV in skin lesions (14, 12 and 9 repeats vs the prevalent 22) and a slight decrease of STR-II in the saliva (8 vs 9 in other matrices). Notably, STR-XIX was absent in the two skin lesion samples (P3_SL_2_I and P3_SL_I), whereas it was present in saliva and pharyngeal swab.

P4 retained all STR loci across matrices, but consistently displayed lower repeat counts at specific sites compared with the predominant pattern in other patients: STR-I = 13 (vs 14), STR-IX = 9 (vs 10) in all P4 matrices, and STR-XIX= 13 (vs 14). Additional matrix-specific differences included STR-VII = 15 in P4_SL_I (vs 19 elsewhere) and STR-XV = 21 in P4_SL_2_I (vs 22 in the other P4 samples).

With the exception of P3 and P4, only sporadic changes were observed: P7_SLG_I showed STR-X = 4 (vs 5 in all other samples), P10_SL_I had STR-XV = 19, P4_SL_2_I and P13_SL_I had STR-XV = 21, P2_SLG_I showed STR-XI = 9 (vs 7 elsewhere), and P5_R_I had STR-II = 7. Several loci also exhibited modest dispersion across patients/timepoints, notably STR-XVII (range 5.6–16) and STR-XVIII (range 7–9).

For the composite STRs (i.e. STR-IX and STR-X), beyond the number of repeated sequences changes, we notice that they segregated into two different block configurations. STR-IX is composed by [ATATTTT]n + [ATTTT]n; we defined the block [ATATTTT] as ‘block a, [a]’ and [ATTTT] as ‘block b, [b]’. The majority of analyzed samples accounted a total of 10 repeats, composed as 7[a] + 3[b]. In all P4 matrices we identified a total of 9 repeats, coherently with alternative architectures, but with the loss of one block a, resulting as 6[a] + 3[b] (

Figure 2b).

Meanwhile, STR-X defined as [GATATGATGGATATGAT]n (block a) + [GGATATGAT]n (block b), at a first glance, seemed stably conserved across samples, except in one case which lost one repeat (P7_SLG_I). In 38 out 40 analyzed samples, the architecture of the STR was 2[a]+3[b], with a 2[a]+2[b] variant in P7_SLG_I, resulting in a total of 4 repeats. Interestingly, in P5_SL_I we noticed a motif rearrangement, leading to 2[b]+ [a] +3[b] (

Figure 2b). Beyond STR-IX and STR-X, sporadic variability was observed in STR-XV, STR-XVII, and STR-XIX, suggesting that most STR changes are patient- or matrix-specific rather than lineage-associated.

2.4. STRs and in Silico Protein Implications

9 out 19 STRs identified were located within annotated genes or partially overlapping the corresponding coding sequences; STR-X and -XIII were positioned in intergenic regions, outside the coding sequence. Analyzing the potential effects of STR variation on the coding sequence, no changes were observed in STR-III, IV, V, XIV, and XVI when compared with the annotated protein (Supplementary material,

Figure S1). STR-X represents one of the most intriguing regions. Although located immediately upstream of the OPG176 coding sequence, its repeat block composition (e.g., 2a+3b vs. 2b+a+3b) showed rearrangements across samples (P5_SL_I and P7_SLG_I), despite overall conservation in repeat number. This structural variability may not directly alter the encoded protein sequence but could impact transcriptional or translational regulation. In contrast, STR-XIII, located within OPG190 (encoding the secreted interferon α/β decoy receptor B19R), remained fully conserved across all samples, consistent with strong functional constraints on this essential immunomodulatory gene[

8,25].

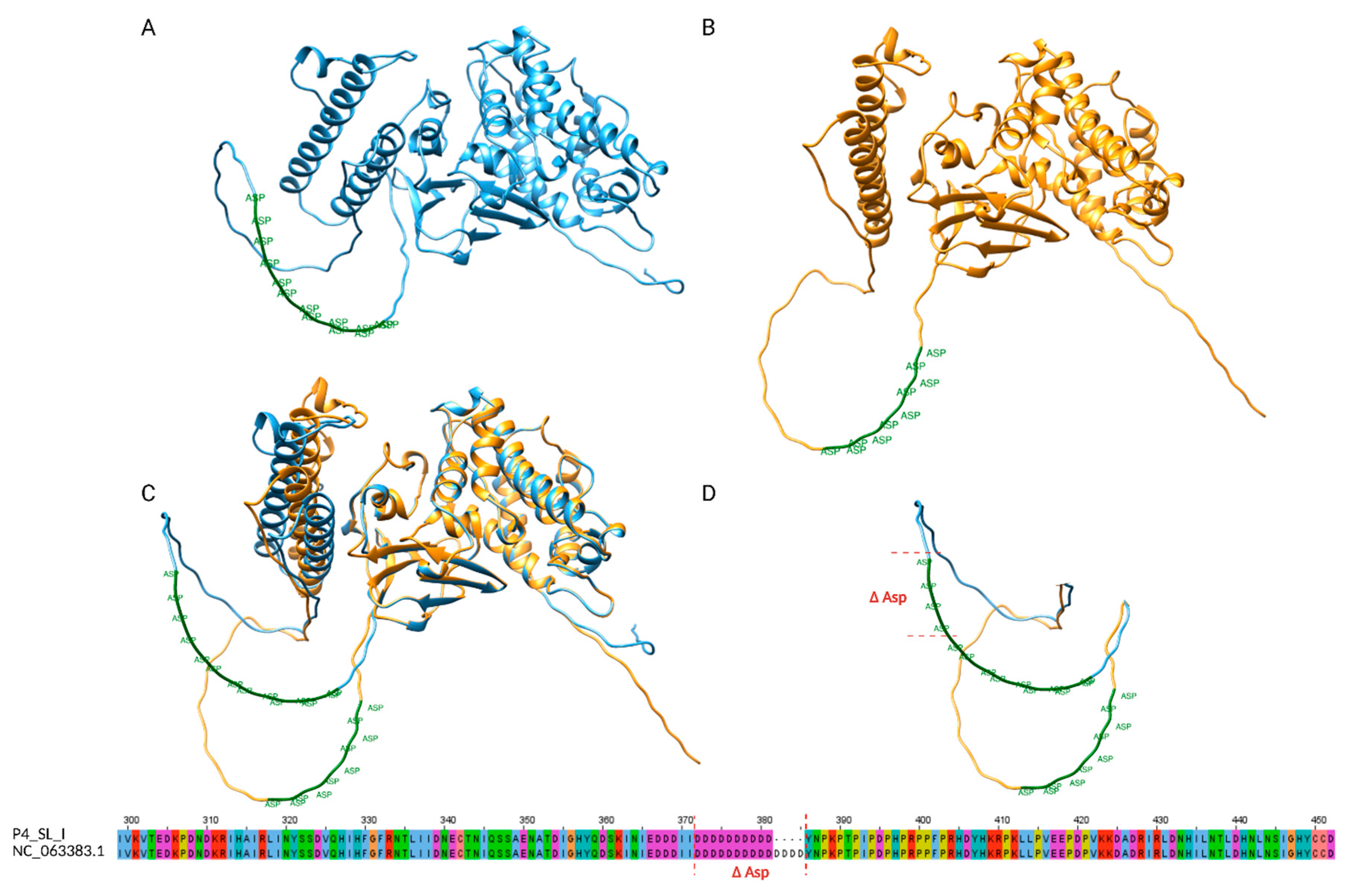

Conversely, the skin lesion sample from P4 at timepoint I (P4_SL_I) showed a lower copy number of STR-VII, which is located within the coding sequence of OPG153. Specifically, we identified a 12 nucleotide in-frame deletion that resulted in the loss of 4 aspartic acid residues in a poly-Asp tract. The OPG153 gene (GeneID: 72551547) spans 1530 bp and encodes for the envelope protein OPG153 (Uniprot ID: A0A7H0DNC4), a surface-associated viral factor implicated in attachment and fusion suppression[

9,26,27]. The STR-VII motif corresponds to a low-complexity, negatively charged region described in UniProt as a compositional bias domain. To evaluate potential structural consequences of the Δ4D deletion, both the wild-type and mutant protein sequences were modeled ab initio using AlphaFold2. Structural alignment of the two models revealed a high overlap, with the deletion confined to a disordered loop within the poly-Asp tract (

Figure 3). The shortened acidic loop of the Δ4D variant displayed a slightly more compact conformation, while the global fold remained unchanged. These observations suggest that the deletion likely alters local electrostatic properties and loop flexibility.

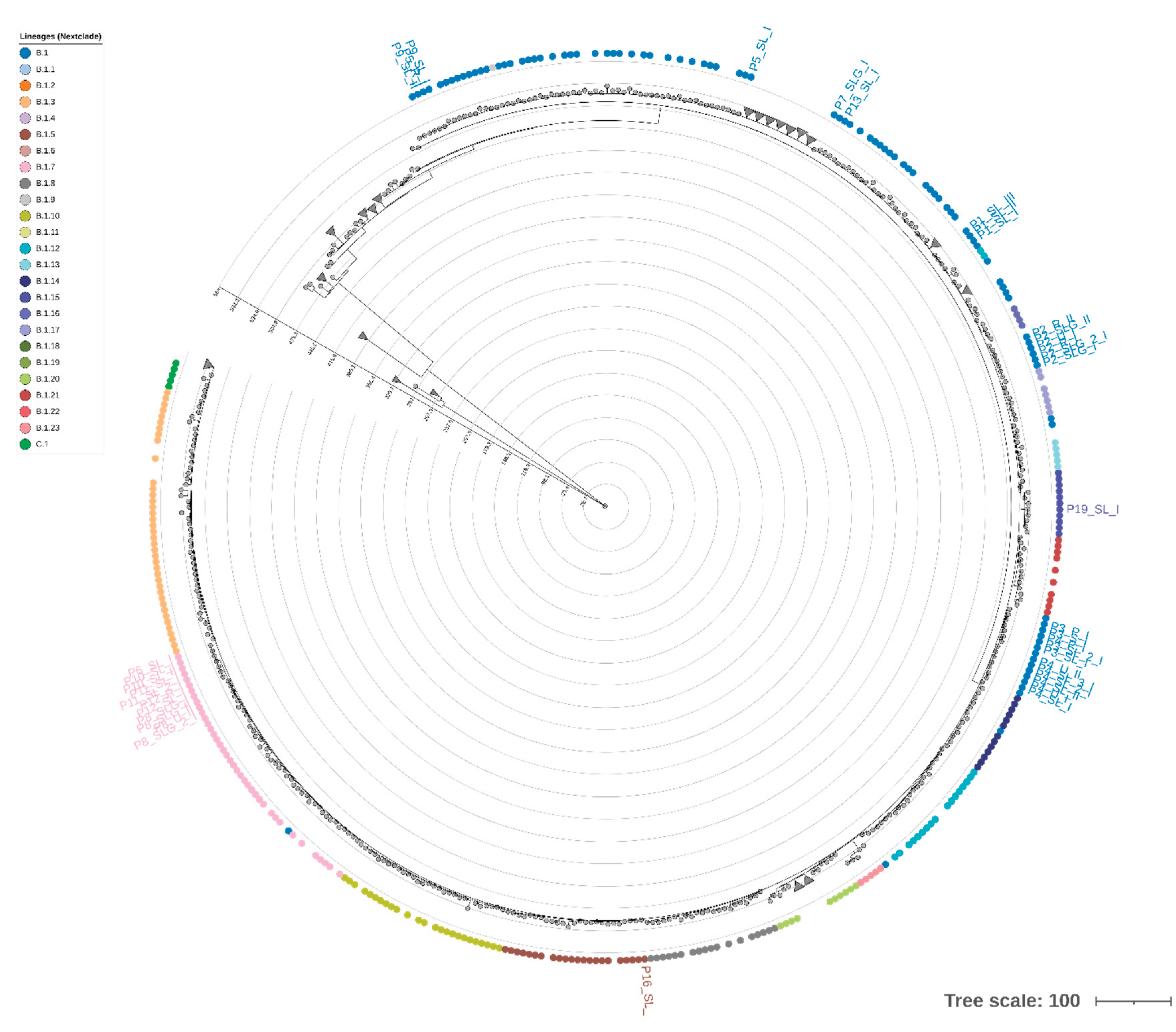

2.5. Phylogenetic Analysis and STR-Based Clustering

Phylogenetic reconstruction based on whole-genome sequences clustered all Italian samples within clade IIb, in agreement with global surveillance data from the 2022–2023 outbreak. Of the total 40 sequences, 27 clustered into lineage B.1, 11 clustered into B.1.7 sublineage, one into B.1.5, and one into B.1.15 (

Figure 4). The tree revealed short branch lengths, indicating limited nucleotide divergence among circulating strains. Minor intra-lineage clustering patterns were detected, notably among P6, P10, P11, and P12, all belonging to sublineage B.1.7, consistent with their shared SNP profiles. P3 and P4 formed a divergent branch supported by private substitutions, in line with the SNP-based variant analysis. To complement the SNP-based phylogeny, we constructed a hierarchical clustering using the STR copy number matrix (

Supplementary Figure S2). The STR dendrogram showed an overall structure consistent with the SNP-based topology, supporting a high degree of genomic conservation across patients. However, subtle rearrangements in clustering order were observed. For instance, P3 and P4, which cluster together in the ML phylogeny, appeared more distant in the STR-based dendrogram due to variation in STR-VII (OPG153), STR-IX and STR-X, while P6, P10, P11, and P12 remained closely grouped, mirroring their shared STR configuration. Notably, the dendrogram did not reveal segregation by matrix type or sampling timepoint. Overall, STR-based clustering partially recapitulates SNP-based phylogeny but provides additional resolution at the intra-lineage level. The discordance between the two approaches suggests that tandem repeat variation evolves independently of point mutations, potentially reflecting rapid, reversible changes driven by polymerase slippage or recombination. These findings support the hypothesis that STRs can act as fast-evolving molecular markers, complementing SNP analyses for high-resolution tracking of MPXV genetic diversity.

3. Discussion

In this study, we provide a comprehensive view of the genomic plasticity of MPXV in a cohort of 16 Italian patients during the 2022 outbreak, by integrating SNP-based and STR analyses, and evaluating intra-host variability across timepoints and different anatomical matrices. Our work combines hybrid assemblies reconstruction, with repeat profiling and mutational analysis, revealing interesting features potentially involved in MPXV evolution and adaptation.

The SNP-based phylogenetic reconstruction confirmed the co-circulation of multiple B.1-derived sublineages, including B.1.7, B.1.5, and B.1.15, consistent with broader genomic surveillance[

6,28]. However, our novel mutation analysis unveiled unexpected convergences between distinct patients. For instance, five novel mutations (C101983T, G28334A, C162816T, C170573T, C72215T) were shared among four unrelated patients (P10, P11, P12, and P6), all belonging to lineage B.1.7. Similarly, the shared substitutions between P3 and P4 (G37152A, C184829T, C152445T) could strengthen the hypothesis of co-circulating, under-sampled variants[29]. Functional annotation of these novel variants indicated that several mapped into or near genes potentially involved in viral fitness or host interaction. For example, OPG002 encodes CrmB, a TNF-binding protein that inhibits inflammatory responses[30; OPG105 contains ankyrin repeats often associated with inhibition of NF-κB signaling[31]. Some of these SNPs are not yet reported in GISAID or GenBank lineage-defining mutation databases[32], suggesting ongoing intra-host diversification. These subtle differences highlight the importance of sampling multiple anatomical sites to capture the full scope of intra-host viral diversity[29].

Importantly, STR profiling revealed a set of 19 conserved STRs (STR-I to STR-XIX), with high stability across most patients and matrices. STRs in genes involved in host immune interactions (e.g., OPG015, OPG204) showed minimal variability, supporting their potential function as key structural regulators[33].

When stratifying the STR profiles by timepoint (I, II, III), no systematic temporal variability was observed. The distribution of repeated sequences copy numbers remained stable across all timepoints, with the few observed differences attributable to inter-sample rather than longitudinal variation. These alterations did not correlate with coverage issues and were independent of lineage, pointing to intra-host viral dynamics. Our results indicate that intragenic STRs are overall under evolutionary constraint, remaining stable in repeat copy number. Nevertheless, STR-IX and STR-X represent notable exceptions, as they exhibit structural reorganization of repeat motifs despite numerical stability. In contrast, variability is concentrated in non-intragenic loci (e.g. STR-XV, STR-XVII, STR-XIX), which may accumulate changes more freely and contribute to inter-patient differences, accordingly with previous findings on repeat instability at specific MPXV genome sites[33]. These results support the view that STRs may act as “evolutionary tuning knobs,” modulating viral gene expression or protein structure in response to host pressures[

16,33]. The association of STRs with genes such as OPG001 (a chemokine-binding protein)[34], OPG044 (a Bcl-2–like immune modulator)[35,36], OPG104 (an entry/fusion protein)[26,37], and OPG180 (a replication-associated protein subject to APOBEC3-like pressure)[38] suggests that STR instability may intersect with functionally important loci, potentially influencing immune evasion, viral entry efficiency, and replication fidelity. The conservation of most intragenic STRs likely reflects strong functional constraints, as repeat variation within coding regions may impact protein length, domain organization, or local folding. In this context, the architectural changes we observed in STR-IX and STR-X are of particular interest, since they may influence local protein conformation despite numerical stability in repeat copy number.

A particularly interesting case was represented by STR-VII, located within the coding region of OPG153. The skin lesion sample from P4 at timepoint I (P4_SL_I) showed a 12-nucleotide in-frame deletion corresponding to the loss of four aspartic acid residues (Δ4D) in a poly aspartic acid tract. The affected motif is located in a low-complexity, acidic region annotated in UniProt as a compositional bias domain. AlphaFold2-based structural modeling revealed that both wild-type and Δ4D proteins share a highly similar global fold, with the deletion confined to a flexible loop within the poly-Asp region (

Figure 3), exhibiting a shorter and more compact loop. These results provide a framework for future investigations aimed at linking repeat architecture to protein structure and viral fitness. A recent work[39] identified broadly neutralizing antibodies targeting OPG153, highlighting its central role in poxvirus immune recognition. Although our analyses did not reveal SNP-based variability in this gene, the structural variation observed in its STR region may influence antigenicity. These findings further emphasize the importance of the integration of structural and immunological perspectives in future investigations.

The loci, OPG176 and OPG190, exemplify opposite selective regimes acting on STRs. For OPG176, STR-X was located immediately upstream of the coding sequence and maintained a stable overall repeat number, but displayed block-level rearrangements (e.g., 2a+3b vs. 2b+a+3b). This architecture plasticity within a non-coding context is consistent with a potential regulatory role, possibly modulating mRNA secondary structure, ribosome accessibility, or translation initiation efficiency (

Figure 1). Given that OPG176 encodes a putative component of the entry/fusion complex involved in membrane fusion and virion morphogenesis, even subtle alterations in its expression timing or abundance could influence virion assembly or cell tropism.[26,27] The conservation of overall repeat length despite changes in motif organization suggests potential effects operating at the transcriptional level.

In contrast, STR-XVI, located within OPG190 (encoding the secreted interferon α/β decoy receptor B19R)[

8], remained completely conserved across all samples. Maintaining the structural and quantitative integrity of B19R is likely critical for effective antagonism of host interferon responses, leaving little room for repeat drift or rearrangement. OPG176 and OPG190 represent two extremes of STR functional behavior: one permissive and regulatory, the other highly constrained and structurally essential.

Together, these findings suggest the interplay between SNPs mutations and STRs variability in shaping MPXV genomic structure and driving its evolution. While SNPs reflect cumulative mutation processes and lineage divergence, STRs appear more sensitive to intra-host forces, capturing short-term dynamics and/or anatomical compartmentalization. Most STR loci and SNP profiles were indistinguishable among patients sampled during the summer period (May–August), consistent with close epidemiological linkage. In contrast, patients sampled later in the year (P3, P4, September–December) carried additional private SNPs and showed slightly more heterogeneity at selected STR loci. This pattern may reflect temporal divergence, independent introductions, although further analyses would be required to confirm this hypothesis. The perspective of a combination of SNPs and STRs variability reveals that, even in a DNA virus with relatively low mutation rates, MPXV could exhibit notable genomic flexibility[40].

Monitoring both SNPs and STRs may improve molecular epidemiology efforts from a public health standpoint. STR configurations could be key complementary markers for phenotypic traits definition such as immune escape. The current results show for the first time the presence of matrix- and patient-dependent SNP and STR patterns within single individuals, supporting a scenario of intra-host viral microevolution. Such phenomenon, while typically associated with chronic RNA virus infections, may also occur in orthopoxviruses infections and contribute to phenotypic or transmission potential variability[

6,41].

In conclusion, our longitudinal, multi-matrix study offers an interesting glimpse into intra-host evolution of MPXV. However, late autumn cases reveal that the viral genome can undergo localized changes, potentially influenced by tissue-specific pressures or immune compartmentalization. These include not only reductions in repeat copy number but also alternative motif architectures in composite STRs (e.g., STR-IX, STR-X). These dynamic features need further investigation in larger cohorts and may have implications for transmission fitness and pathogenesis. These findings pave the way for future studies aimed at integrating genomic observations, such as matrix-specific STR patterns and novel SNP profiles, with detailed clinical data, including disease severity, symptom localization, and immune response. This integrative approach may help clarify whether intra-host genomic variability correlates with phenotypic manifestations and tissue tropism, ultimately improving our understanding of MPXV pathogenesis and transmission dynamics.

4. Materials and Methods

Clinical specimens were collected from patients presenting with skin lesions and clinical manifestations suggestive of mpox infection. Samples were initially submitted for diagnostic purposes to the regional referral laboratory at IRCCS Sacro Cuore Don Calabria Hospital, Negrar di Valpolicella (Verona, Veneto Region, Italy).

A total of 16 patients were confirmed to have mpox by qPCR (Monkeypox Virus Real-Time PCR Kit, BioPerfectus, Taizhou City, China), with cycle threshold (Ct) values ≤28. Samples yielding these Ct values were selected for full-genome sequencing.

Following diagnosis, all 16 confirmed patients were enrolled in a longitudinal follow-up protocol. Weekly samples were collected from multiple anatomical sites, including skin lesions, saliva, urine, and pharyngeal swabs, starting from the time of diagnosis and continuing until viral clearance, defined by two consecutive negative qPCR results. A total of 4 patients completed two follow-up visits, and one patient completed three visits.

In total, 40 clinical samples from 16 patients were included in the sequencing analysis. All patients were male and received a diagnosis of mpox between May and X 2022. Patients’ demographic characteristics and the types of collected specimens are summarized in

Table 2.

4.1. DNA Extraction, Library Preparation, and Sequencing

Viral DNA was extracted from 200 µL of each matrix and eluted in 60 µL using an EZ1 Advanced XL instrument and EZ1 DSP Virus Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. DNA concentration was determined using the Qubit dsDNA HS assay kit (Thermofisher, Waltham, MA, USA). For short-read sequencing, a target enrichment based on hybrid capture was carried out using the Illumina RNA prep with enrichment kit, with the VSP panel v1 (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). The quality of libraries was assessed using the genomic ScreenTape kit and the 4200 TapeStation System (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Illumina libraries were prepared according to the manufacturer’s instructions and run on a NextSeq1000 using the P1 300-cycle Illumina flow cell to perform 2×150 paired-end sequencing. For long-read Oxford Nanopore Technology (ONT) sequencing, enrichment was performed by generating 2,5 kbp-amplicons24. Shortly, two separate reactions were set up per sample as follows: 6.88 μL nuclease-free water, 0.625 μL primers pool 1 or 2 (100 μM), 12.5 μL Q5 High-Fidelity 2X master mix (New England Biolabs, USA), and 5 μL of sample DNA. Amplification reaction was set up with the following parameters: 98°C - 1 min, then 35 cycles of 98°C - 10 sec, 65°C - 30 sec, 69°C - 100 sec, and a final extension at 72°C for 2 min. Separate reactions were then pooled for each sample, and 200 fmol of DNA was used to prepare sequencing libraries with the Native Barcoding Sequencing Kit (SQK-NBD114.24 Oxford Nanopore Technologies, UK) as per manufacturer’s instructions. ONT libraries were run on a MinION Mk1d instrument using FLO-MIN114 (Oxford Nanopore Technologies, UK) flow cells to a target of 100x coverage per sample.

4.2. Bioinformatic Analysis

Read QC was performed with fastp v0.23.4 and fastqc v0.12.1. Human reads were removed using Kraken2 v2.1.3[42]. Reads were aligned to the MPXV reference genome (NC_063383.1) using BWA-MEM v2.2.1[43,44]; variants were called with bcftools v1.20[45], filtering for Q>30, mapQ>50, DP>20.

4.2.1. Hybrid Assembly

In order to explore the STRs variability, hybrid assemblies were generated using Unicycler v0.5.1[46] combining Illumina and ONT reads, oriented with MUMmer/Nucmer v4.0.1[47], finally, the oriented contigs were assembled into a single scaffold using a homemade script. This script concatenates the aligned contigs while accounting for gaps within and between them, allowing their accurate identification and distinction. The correspondence between the experimental ID (reported in this manuscript) and the GISAID IDs (EPI_IDs) is provided in the Table_S3 in Supplementary materials.

4.2.2. STR Analysis

Short tandem repeats were identified using Tandem Repeat Finder[48] (parameters “2 7 7 80 10 50 2000 -ngs”), retaining loci with entropy > 1.8, match ≥ 80%, and non-overlapping regions. Partial repeats were also considered. All loci were manually curated.

4.2.3. Global Dataset, Phylogeny and STR-Based Clustering Analysis

Complete (>196 kb) MPXV genomes (n = 2108, as of 21 Aug 2025) were downloaded from GISAID EpiPox[32], excluding low-coverage sequences (>5% Ns).

To investigate the phylogenetic evolution, a Maximum Likelihood (ML) phylogenetic tree was reconstructed using a dataset including our samples and the complete sequences available from the GISAID repository, for a total of 2148 records. Multiple alignment was performed with MAFFT v7.523[49], and ML phylogeny was inferred using IQ-TREE v2.2.2.7[50] and visualized in iTOL v6.9.1[51]. To investigate STR similarities between samples, we performed a hierarchical clustering using number of STR repeats belonging to each sample matrices (Euclidean distance, R packages ape, dendextend, and ggtree) [52,53,54].

4.2.4. Protein Translation and in Silico Structural Prediction

Genomic sequences containing STRs located within protein-coding regions were translated into amino acid sequences using the EMBOSS v.6.6.0.0 [55] executed from the command line. Translation was performed according to the standard genetic code, preserving the annotated reading frame and strand orientation. The resulting protein was compared to its corresponding wild-type reference, derived from UniProt[56] annotations of the same gene. When sequence alterations were detected relative to the reference, the affected open reading frames were subjected to three-dimensional structure prediction using AlphaFold2[57] (ab initio modeling). In particular, the OPG153 gene (GeneID: 72551547) and its Δ4D variant were modeled independently. Structural visualization and overlay were carried out using Chimera tool v.1.19[58,59].

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Table_S1. Sheet 1 – Illumina: Illumina sequencing metrics of Monkeypox virus clinical samples. This table summarizes the sequencing performance obtained using the Illumina and ONT platforms for each clinical sample. It includes the total number of reads, the number of viral reads mapped to the Monkeypox virus reference genome, the average depth of coverage, and the percentage of genome covered by sequencing reads. Sheet 2 – ONT: ONT sequencing metrics of Monkeypox virus clinical samples. This table reports the sequencing performance of clinical samples processed using the ONT platform. For each sample, the total number of reads, number of viral reads, average depth of coverage, and genome coverage percentage are provided. Sheet 3 – hybrid assembly: Hybrid genome assembly metrics combining Illumina and ONT data. This table presents the results of hybrid genome assemblies obtained by combining Illumina short reads and ONT long reads. It includes key assembly statistics such as total genome length, number of contigs, N50, GC content, and coverage depth, providing an overview of the final genome reconstruction quality. * Number of contigs required to cover at least 50% of the total assembly length (N50 value). Table_S2. Summary of genomic variants detected in Monkeypox virus isolates from clinical samples. This table lists the single-nucleotide substitutions, deletions, insertions, and frameshift mutations identified in each sample across different time points and matrices. For each patient and sample, the corresponding clade, lineage, total number of substitutions, deletions, and insertions are reported, along with the amino acid substitutions and private mutations unique to that sample. Table_S3.Data availability. List of samples included in the study, associated metadata (collection date and age), and GISAID accession IDs corresponding to the consensus sequences deposited in the GISAID EpiPox database. Figure_S1. Multiple sequence alignment of amino acid sequences corresponding to STR-containing regions. Red boxes indicate amino acid residues encoded by or directly affected by STR loci. OPG176 and OPG190 d are not shown, as their associated repeat regions are located outside the protein-coding sequence. Figure_S2. Hierarchical clustering of STR profiles. The dendrogram is based on Euclidean distances, which reflect the dissimilarity between STR repeat copy numbers. Shorter distances indicate higher similarity in STR patterns between samples, while longer distances reflect greater divergence. The clustering is derived from repeat copy numbers and does not represent nucleotide sequence relationships..

Author Contributions

MD, CC, and CP conceived the study. MD designed the study. MD and SM performed the experiments. AM performing the molecular assays. S.A. and M.G.C. was responsible for samples collection. AG., NR.FGG. and ET were responsible for patients’ enrollment and clinical evaluation. MD, EL, SM, LV, and DL performed formal data analyses. All authors interpreted and analyzed data. MD and CP drafted the manuscript. All authors revised the manuscript.

Funding

Please add: This work was supported by EU funding within the MUR PNRR Extended Partnership initiative on Emerging Infectious Diseases (project no. PE00000007, INF-ACT). Michela Deiana was a recipient of an Early-Career Award (ECA-INF-ACT 2024). The work was also supported by the Italian Ministry of Health “Fondi Ricerca Corrente—L1P3” to IRCCS Sacro Cuore Don Calabria Hospital.

Institutional Review Board Statement

All patients signed an informed consent form. The study received ethical clearance from the Ethical Committee of Verona and Rovigo provinces (Prot. n. 6232, 30 January 2023). Samples used in this study were stored at -80°C in the “Tropica Biobank - (bbmri-eric:ID:IT_1605519998080235)” of the IRCCS Sacro Cuore Don Calabria Hospital until use.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The sequences have been deposited in the GISAID repository. The correspondence between the experimental ID (reported in this manuscript) and the GISAID IDs (EPI_IDs) is provided in the Table_S3 in Supplementary materials. The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge all data contributors, i.e., the Authors and their Originating laboratories responsible for obtaining the specimens, and their Submitting laboratories for generating the genetic sequence and metadata and sharing via the GISAID Initiative, on which this research is based.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial conflict of interest.

References

- Reynolds, M.G.; Carroll, D.S.; Karem, K.L. Factors Affecting the Likelihood of Monkeypox’s Emergence and Spread in the Post-Smallpox Era. Curr Opin Virol. 2012, 2, 335–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lloyd-Smith, J.O. Vacated Niches, Competitive Release and the Community Ecology of Pathogen Eradication. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2013, 368, 20120150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- World Health Organization Global Commission for the Certification of Smallpox Eradication. The Achievement of Global Eradication of Smallpox: Final Report of the Global Commission for the Certification of Smallpox Eradication; WHO: Geneva; Geneva, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Naga, N.G.; Nawar, E.A.; Mobarak, A.A.; Faramawy, A.G.; Al-Kordy, H.M.H. Monkeypox: A Re-Emergent Virus with Global Health Implications - a Comprehensive Review. Trop Dis Travel Med Vaccines 2025, 11, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 2022-25 Mpox Outbreak: Global Trends. World Health Organization: Geneva, 2025. Available online: Https://Worldhealthorg.Shinyapps.Io/Mpx_global/.

- Isidro, J.; Borges, V.; Pinto, M.; Sobral, D.; Santos, J.D.; Nunes, A.; Mixão, V.; Ferreira, R.; Santos, D.; Duarte, S.; et al. Phylogenomic Characterization and Signs of Microevolution in the 2022 Multi-Country Outbreak of Monkeypox Virus. Nature Medicine 2022, 28, 1569–1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shchelkunov, SN; Totmenin, AV; Safronov, PF; Mikheev, MV; Gutorov, VV; Ryazankina, OI; Petrov, NA; Babkin, IV; Uvarova, EA; Sandakhchiev, LS; Sisler, JR; Esposito, JJ; Damon, IK; Jahrling, PB. Moss B Analysis of the Monkeypox Virus Genome Analysis of the Monkeypox Virus Genome. Virology;Virology 2002, 297 297, 172–94 172–194. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Alcami, A.; Koszinowski, U.H. Viral Mechanisms of Immune Evasion. Trends in Microbiology 2000, 8, 410–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moss, B.; Shisler, J.L. Immunology 101 at Poxvirus U: Immune Evasion Genes. Seminars in Immunology 2001, 13, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Likos, A.M.; et al. A Tale of Two Clades: Monkeypox Viruses. Journal of General Virology 2005, 86, 2661–2672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doty, J.B.; et al. Assessing Monkeypox Virus Prevalence in Small Mammals at the Human–Animal Interface in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Viruses 2017, 9, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakazawa, Y.; et al. A Phylogeographic Investigation of African Monkeypox. Viruses 2015, 7, 2168–2184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO Monkeypox Fact Sheet. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/monkeypox.

- Esteban, D.J.; Hutchinson, A.P. Genes in the Terminal Regions of Orthopoxvirus Genomes Experience Adaptive Molecular Evolution. BMC Genomics 2011, 12, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, A.L.; Friedman, R. Poxvirus Genome Evolution by Gene Gain and Loss. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 2005, 35, 186–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kugelman, J.R. Genomic Variability and Tandem Repeats in Variola Virus and Monkeypox Virus. Emerging Infectious Diseases 2014, 20, 232–239. [Google Scholar]

- Elde, N.C.; Child, S.J.; Eickbush, M.T.; Kitzman, J.O.; Rogers, K.S.; Shendure, J.; Geballe, A.P.; Malik, H.S. Poxviruses Deploy Genomic Accordions to Adapt Rapidly against Host Antiviral Defenses. Cell 2012, 150, 831–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeh, T.-Y.; et al. Recombination Shapes the 2022 Monkeypox (Mpox) Outbreak. Med 2022, 3, 824–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, N.; Yadav, V.K.; Singh, H. Identification and Analysis of Microsatellites in Coronaviridae. Virus Research 2024, 336, 199328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katoh, H.; Zheng, H.; Ono, Y. others Genome-Wide Identification and Characterization of Simple Sequence Repeats in Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). Scientific Reports 2020, 10, 15354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez-Tenorio, F.J.; Rojas-López, A.; Arias, C.F. Microsatellite Repeats in the Genome of Caliciviruses. Journal of Virology 2002, 76, 10638–10643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Zhang, J.; Liu, H. others Characterization of Microsatellites in Herpes Simplex Virus Genomes. Frontiers in Microbiology 2015, 6, 1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, X. others Characterization of Microsatellites in the Orf Virus Genome and Their Potential Role in Viral Evolution. Infection, Genetics and Evolution 2021, 90, 104752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monzón, S.; Varona, S.; Negredo, A.; Vidal-Freire, S.; Patiño-Galindo, J.A.; Ferressini-Gerpe, N.; Zaballos, A.; Orviz, E.; Ayerdi, O.; Muñoz-Gómez, A.; et al. Monkeypox Virus Genomic Accordion Strategies. Nature Communications 2024, 15, 3059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).