1. Introduction

Livestock agriculture stands at the center of profound demographic, environmental and ethical pressures that shape the trajectory of global food systems. Rapid population growth, projected to approach 9.7 billion by mid-century, is expected to increase demand for animal-source foods, even as resource limitations and climatic instability constrain the capacity of production systems to respond effectively [

1]. Livestock are already responsible for a substantial share of anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions, with ruminant methane and manure-derived nitrous oxide recognized as significant hurdles for meeting international climate targets [

2]. Although poultry systems generate comparatively lower methane emissions, their environmental burdens remain considerable due to feed production, manure management and energy use, and they are further complicated by welfare concerns and recurring vulnerability to diseases such as avian influenza [

3]. These tensions have intensified interest in developing technological strategies that enhance productivity, resilience, welfare and sustainability while navigating the constraints imposed by biological variability and economic realities.

Over the past three decades, precision livestock farming has emerged as one response to these pressures, advancing from isolated sensor systems toward more integrated, data-enriched approaches to husbandry. In dairy production, early innovations centered on single-modality devices such as pedometers and neck-mounted accelerometers for estrus detection, in-line milk meters for continuous yield recording and research-grade rumen pH boluses designed to study subacute ruminal acidosis [

4]. These systems produced discrete indicators that supported specific management decisions but offered only partial representations of animal status. Poultry applications began with simple environmental controllers linked to temperature and humidity probes, alongside weighing platforms used to estimate flock mass. Behavioral or welfare measurements were limited, reflecting both the scale of commercial poultry houses and the perceived complexity of monitoring individuals within large flocks [

5].

As sensing technologies became more affordable and computational capacity increased, multimodal monitoring platforms emerged across both species. Dairy operations began integrating accelerometers, rumination microphones, thermal imaging and milk conductivity sensors, enabling more comprehensive assessments of physiology and behavior [

6]. In poultry houses, high-resolution cameras, dense environmental sensor arrays and microphone networks capable of capturing vocalization patterns associated with stress or respiratory disturbances were deployed, providing new avenues for inferring flock-level states [

7]. These developments marked a significant shift from isolated measurements toward richer, continuous data streams that could describe animals and environments with increasing granularity.

The conceptual leap toward digital twins occurred when these multimodal sensor platforms were re-imagined as the perceptual layer of virtual counterparts of animals or facilities. Digital twins, originally defined in aerospace engineering, describe continuously updated virtual entities that remain tightly coupled to their physical versions through live data streams [

8]. The application of this concept to livestock systems gained traction as researchers recognized that established nutrition, growth and disease-risk models—long used in the dairy and poultry sciences—could serve as the computational engines of these virtual organisms or virtual barns [

9]. In this framing, a digital twin assimilates behavioral, physiological and environmental data, updates latent states, supports scenario analysis and informs decisions aimed at improving health, welfare, or system performance.

Analogous developments in industry further catalyzed interest in agricultural digital twins. In advanced manufacturing and aerospace, digital twins have transitioned from experimental frameworks to operational tools used for structural monitoring, production optimization and lifecycle assessment [

10]. Their success has been facilitated by standardized architecture, verification protocols and reporting of system reliability and environmental impacts. The attractiveness of these industrial precedents led agriculture researchers to explore comparable models adapted to biological systems. Reviews focused on smart farming and Agriculture 5.0 highlight the significant potential of digital twins, but they also underscore the technological, infrastructural and methodological gaps that currently limit their adoption in livestock systems [

11,

12].

Despite these limitations, digital twin narratives have diffused rapidly through the livestock sector. They now appear in conference presentations, industry white papers and strategic planning documents, often framed as the logical next evolution of precision livestock farming [

13]. Yet most implementations remain at prototype or pilot stage, with notable challenges in interoperability across sensor vendors, inconsistencies in data quality and a scarcity of long-term validation studies that could demonstrate robust performance in real commercial environments [

14]. These challenges underscore the inherent complexity of biological systems and the difficulty of translating digital twin concepts from engineered domains to dynamic, heterogeneous livestock settings.

Awareness of this complexity has motivated efforts to position livestock digital twins within broader frameworks of technological development, including the Gartner hype cycle. Early enthusiasm was driven by demonstrations that computer vision, accelerometry and environmental sensing could outperform human observation in detecting health or welfare deviations [

7]. This enthusiasm contributed to a peak of expectations in which digital twins were credited with the potential to deliver large gains in efficiency, major reductions in environmental impact and near-perfect predictive accuracy, often extrapolated from controlled experiments or simulation studies. More recent work has tempered these claims, documenting the fragility of sensor networks in harsh barn environments, the difficulty of integrating heterogeneous data systems and the gap between performance in laboratory conditions and commercial practice [

14]. These findings suggest that livestock digital twins are entering a period in which inflated expectations must be recalibrated toward achievable, evidence-supported value propositions.

A further complication arises from the inconsistent use of the term “digital twin” across agricultural research and industry. Some systems labeled as digital twins are, in practice, sophisticated dashboards that aggregate sensor data without mechanistic modelling or feedback control. Others function as simulation tools only loosely connected to live data. In engineering, a digital twin is defined by persistent synchronization between virtual and physical systems, dynamic state estimation and the ability to evaluate alternative interventions that influence real-time management decisions [

8,

10]. Translating this definition to livestock farming implies a virtual dairy cow or flock that assimilates continuous behavioral, physiological and environmental data, updates predictions regarding health or performance and simulates the consequences of alternative feeding, stocking or climate-control decisions. Distinguishing such fully coupled digital twins from simpler monitoring platforms is essential because their validation requirements, reliability expectations and ethical implications differ substantially.

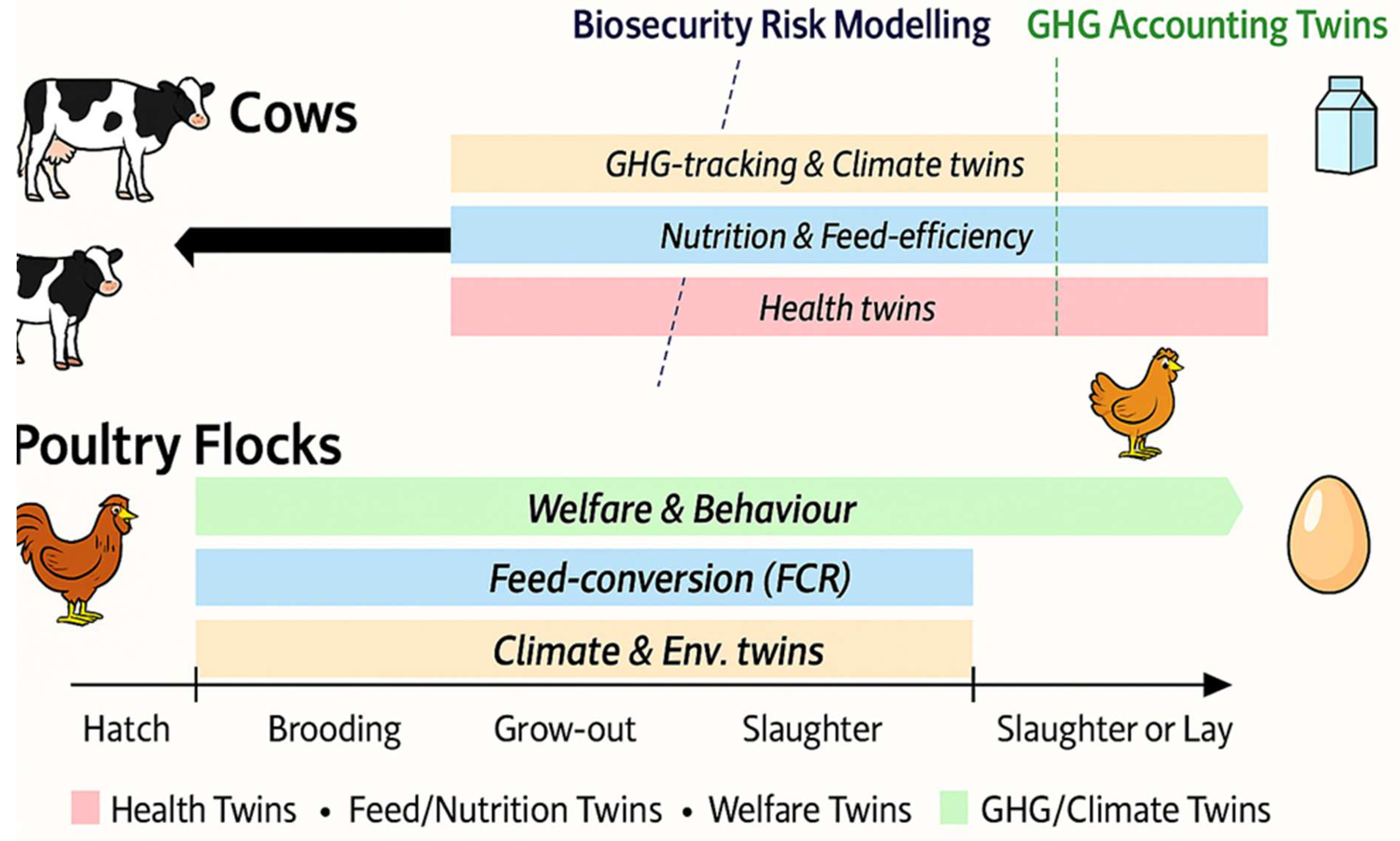

The challenges and opportunities associated with digital twins differ markedly between dairy and poultry production systems. Dairy cows are long-lived, high-value animals with chronic health challenges including mastitis, lameness and metabolic disorders. These constraints justify relatively sophisticated instrumentation such as rumen boluses, activity sensors and in-line milk analyzers, which generate rich longitudinal datasets suited to individual-level modelling and decision support [

4]. Digital twins in dairy therefore emphasize individual trajectories, including early detection of subclinical disease, optimization of feed efficiency and modelling of methane emissions grounded in metabolic physiology [

15]. Poultry production, by contrast, involves short-lived, low-value animals managed in large, uniform flocks. Disease risks are often acute and rapidly spreading, management decisions occur at flock scale and performance metrics such as feed conversion ratio dominate economic outcomes [

3,

5]. Consequently, poultry digital twins focus on flock-level dynamics, disease incursion and spread, barn microclimate regulation and feed efficiency, drawing heavily on computer vision and environmental sensing [

7,

16].

These structural contrasts shape how technological claims should be evaluated. In dairy systems, assertions regarding improved mastitis detection, ration precision or methane mitigation require demonstration of long-term, animal-level benefits. In poultry systems, claims of enhanced feed conversion or reduced mortality require evidence across multiple production cycles, housing conditions and seasons. Overstatement risks eroding trust among early adopters and slowing the broader adoption of data-driven livestock technologies [

14].

The aim of this study is to clarify the current position of digital twins for cows and chickens along the continuum from conceptual construct to practical, validated technology. Through analysis of historical developments in precision livestock farming, comparison of structural and biological differences across species and synthesis of how digital twin concepts have evolved across research and commercial narratives, the study seeks to distinguish verifiable capabilities from aspirational rhetoric. The overarching objective is to outline how livestock digital twins can advance toward systems that are biologically meaningful, economically viable and environmentally accountable.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Databases and Thematic Queries

The methodological strategy was developed to build a comprehensive and thematically structured body of evidence spanning both dairy cattle and poultry systems, reflecting the dual focus of this study on cows and chickens. The search was intentionally organized around four empirically tractable questions that interrogate key dimensions of digital twin readiness in livestock. These questions addressed the carbon footprint of digital agriculture infrastructures deployed in livestock environments, the extent of field-validated improvements in poultry feed conversion ratio attributable to digital decision systems, the performance assessment frameworks proposed or applied to livestock digital twins and the reported failure rates, data quality degradation, downtime and abandonment associated with precision livestock technologies.

To address these themes systematically, searches were conducted across Web of Science Core Collection, Scopus, PubMed, ScienceDirect, IEEE Xplore and Google Scholar, complemented by Semantic Scholar and OpenAlex. Query strings were designed to retrieve studies involving dairy cattle, beef cattle, broilers, layers and cross-species frameworks explicitly intended for livestock. For the carbon-footprint theme, search expressions combined descriptors of digital agriculture with lifecycle assessment concepts and digital-infrastructure terms capable of capturing analyses of sensor systems, embedded controllers and cloud-based platforms used in cattle barns and poultry houses. For the feed-conversion theme, queries combined digital twin, cyber-physical system and adaptive-control terminology with species-specific descriptors for broilers and laying hens and with performance indicators related to feed efficiency. These were supplemented with adaptive-control terminology to identify studies in which digital systems influenced growth trajectories or microclimate regulation.

The performance-framework theme required broader cross-sectoral expressions because many maturity models and evaluation frameworks originate in manufacturing or process-industry domains before being adapted to livestock contexts. Combinations of digital-twin terminology with performance and evaluation descriptors were used to retrieve frameworks that could plausibly apply to dairy and poultry systems. The failure-and-abandonment theme emphasized operational fragility and searched for descriptions of reliability, downtime, sensor degradation, signal loss and data-quality problems across both dairy and poultry deployments. Because reliability information is often embedded within methodological notes rather than indexed in titles or abstracts, semantic search functions within the Elicit platform were used to identify studies containing discussion of “missing data,” “sensor drift,” “signal instability” or “system downtime.”

All search activities were restricted to publications in English between January 2015 and November 2025 to capture the period during which sensor-dense livestock systems and digital-twin concepts became technically feasible. The entire search strategy was cross-checked against existing surveys of digital systems in dairy and poultry to minimise the risk of missing known landmark studies. All search strings were constructed to capture both ruminant systems centred on dairy cows and monogastric poultry systems including broilers and laying hens, reflecting the dual focus of this study on cows and chickens.

2.2. Screening and Study Selection

The combined database searches returned approximately two thousand unique records after deduplication. Screening followed a two-stage procedure aligned with PRISMA principles. In the first stage, titles and abstracts were evaluated to remove studies clearly outside the domain of livestock production, including applications in industrial engineering, crop-only digital systems and generic Internet-of-Things deployments without modelling or decision-support components. Conceptual and review papers were retained if they related to either dairy or poultry and contributed to at least one of the thematic questions. After this stage, three hundred and fifty to four hundred records remained.

In the second stage, full-text screening was undertaken using more stringent inclusion criteria. Studies were retained if they described digital, cyber-physical or near-digital-twin systems applied to dairy cattle or commercial poultry, or frameworks explicitly spanning these two species groups. Each study needed to incorporate at least two of three elements—multimodal sensing, a dynamical or statistical modelling component and some form of decision support or automated control. For feed-conversion and system-failure themes, studies needed to report quantitative endpoints such as feed conversion ratio, mortality, downtime or data-discard rates. For carbon-footprint analyses, studies needed to quantify greenhouse-gas emissions or related environmental indicators attributable to digital or sensing infrastructures rather than whole-farm management. Papers outlining purely aspirational visions without technical detail were excluded.

Approximately two hundred full-text articles were examined in depth. Roughly one hundred met all inclusion criteria for at least one thematic strand and were incorporated into a structured evidence matrix. Several studies addressed both dairy and poultry sectors or spanned multiple themes, allowing individual papers to contribute evidence to more than one strand. The final dataset therefore included empirical field trials in commercial dairy barns and poultry houses, simulations driven by real farm data, case studies of digital deployments and conceptual analyses clarifying system architecture or adoption patterns. A summary table in the full paper will map these studies by species, system archetype, study design and endpoint to illustrate the distribution of evidence and the location of the most prominent gaps.

2.3. Data Extraction and Risk of Bias

Data extraction was carried out using a structured template capturing system-level, design-level and outcome-level information across both dairy and poultry studies. Species was coded as dairy, poultry or mixed, enabling separate synthesis for cows and chickens as well as integrated interpretation where cross-cutting themes emerged. System-level fields captured species and production system (such as free-stall Holstein barns, pasture-based dairies, commercial broiler houses and enriched-cage layer facilities), scale of deployment, sensor types and placement, data sampling frequency, data-pipeline architecture and the modelling approach used by the system. Design-level fields captured study duration, number of animals or houses, the structure of comparison groups, whether randomisation or blinding was present and whether trials spanned single or multiple production cycles.

Outcome-level fields recorded all quantitative metrics relevant to the four thematic strands. For health-focused dairy systems, extracted metrics included sensitivity, specificity, predictive value and detection lead time. For nutrition and feed-conversion analyses in both cattle and poultry, recorded metrics included FCR, feed intake, weight gain, milk yield or egg production. Environmental and microclimate systems contributed data on temperature and humidity regulation, energy consumption and, where available, emissions estimates. Reliability metrics captured device failure rates, signal-loss events, percentages of discarded data, system downtime and maintenance load. When reported, economic indicators and farmer experiences, including perceived usefulness and trust, were noted to contextualize feasibility in both dairy and poultry settings.

Heterogeneity in study design precluded use of a single formal risk-of-bias tool. Recurring sources of bias included publication bias due to the scarcity of negative results, geographic skew arising from regional concentration of certain technologies, vendor involvement that limited independent benchmarking and conceptual heterogeneity in which disparate systems were labelled as digital twins. Short follow-up periods and single-cycle evaluations were common, reducing the ability to assess stability across seasons or production cycles. These considerations informed subsequent analysis and interpretation of the evidence regarding the current state of digital-twin development for dairy and poultry production systems.

2.4. Results Mapping Paragraph

The findings presented in the Results section are organised according to the four thematic strands that shaped the search strategy and screening process. Evidence for each theme is synthesized separately for dairy and poultry systems, with cross-species patterns highlighted where relevant. Quantitative outcomes for health, nutrition, environmental performance and reliability are mapped against the system-level and design-level characteristics captured during data extraction, allowing identification of recurring strengths, gaps and methodological limitations. This structure enables a coherent comparison of digital twin maturity across cows and chickens, clarifies where evidence clusters and reveals where robust field-validated data remain sparse.

3. Architecture and Enabling Technologies

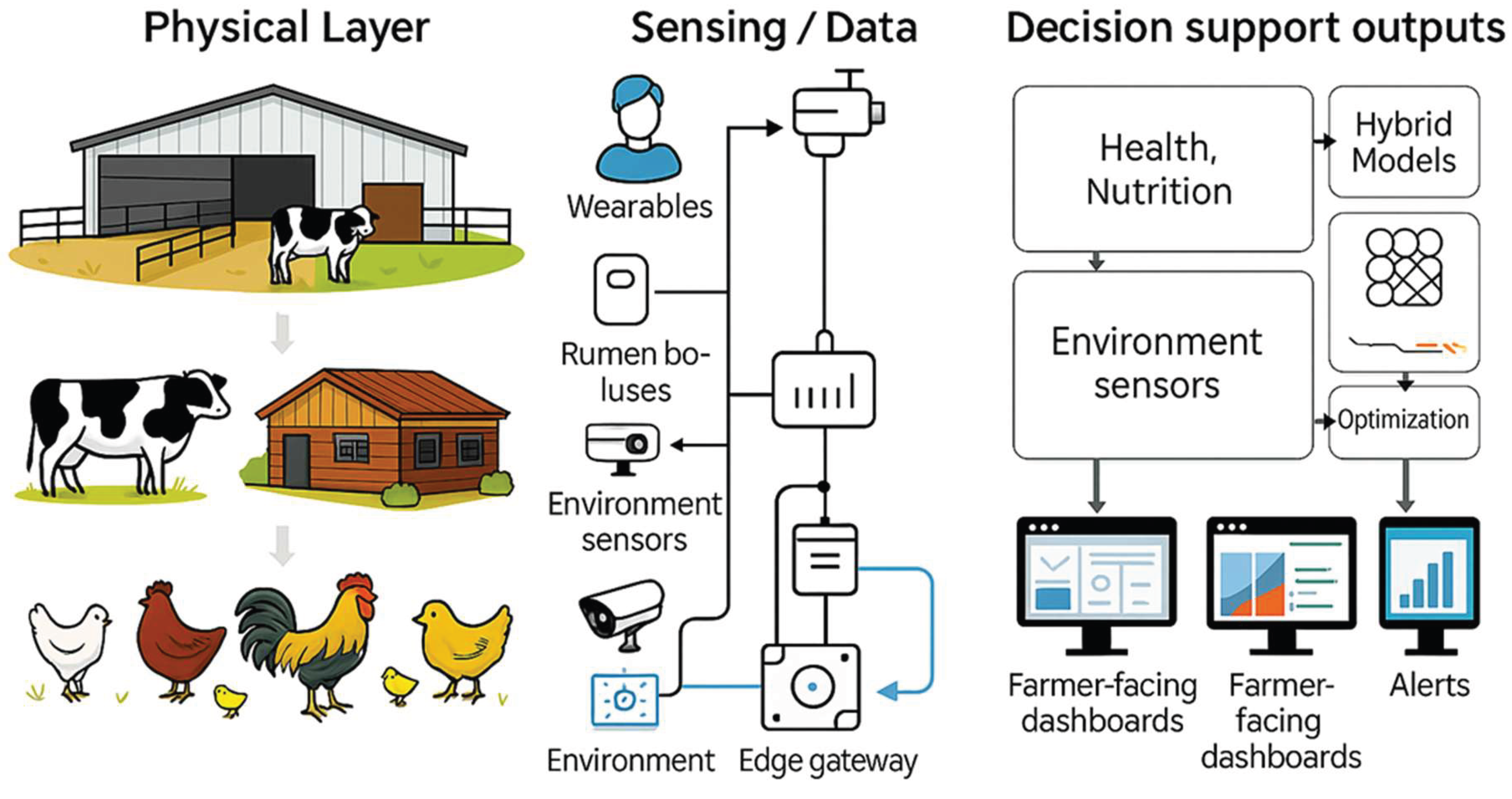

Digital twins for cows and chickens can be conceptualized as layered cyber–physical systems that couple sensing, computation, modelling and decision support into a continuously updating representation of animals and their environments. For clarity, this review organizes livestock digital twin architectures into five layers: sensing, edge and cloud data pipelines, models, control and optimization, and interfaces and human interaction [

17,

18,

19]. Each layer raises distinct design questions and is illustrated here with concrete examples from dairy and poultry systems [

17,

18,

19].

3.1. Layer 1: Sensors and Data Acquisition

The sensing layer provides the raw material from which digital twins are constructed. In dairy systems, sensors now include on-animal, in-animal and in-barn devices that capture behavior, physiology and microclimate at high temporal resolution. Wearable accelerometer collars and leg tags quantify activity, lying bouts and step counts, and can infer rumination time through acoustic or vibration signatures. These signals form key inputs to the behavior and health modules of dairy digital twins. Ingestible rumen boluses have progressed from research prototypes to commercially deployed devices capable of measuring internal temperature and pH over multiple years, providing a stable, long-term sensor node within the virtual representation of the cow. Continuous internal temperature and pH profiles can reveal drinking events, changes in feed intake, heat stress and inflammatory processes, all highly relevant latent states for digital twin models. Milking robots and parlor systems generate high-frequency data on milk yield, electrical conductivity, flow curves and, in some systems, mid-infrared spectra that provide information on udder health, metabolic status and energy balance. Barn-level sensors measuring temperature, humidity, ammonia and carbon dioxide complement animal-centric data and are essential for linking cow responses to environmental conditions.

In poultry, low unit value and high stocking density limit individual instrumentation, so sensing strategies focus on environmental and flock-level observation. Smart poultry houses deploy networks of temperature, humidity and gas sensors alongside static or pan–tilt cameras that capture flock distribution, movement and surface behavior. Several frameworks integrate camera, microphone and gas-sensor stacks to monitor behavioral and environmental indicators concurrently [

26,

27,

28]. Cameras track dispersion and locomotion, microphones capture vocalization patterns and respiratory sounds, and gas sensors quantify air quality and ventilation effectiveness. Recent poultry digital twin frameworks describe such multimodal sensing as the perceptual system of the virtual poultry house, enabling the twin to infer welfare and health states from spatial, behavioral and acoustic patterns.

Despite these advances, sensor deployment in commercial barns remains challenging. Dust, moisture and ammonia cause sensor drift and failures, and animals or equipment can damage cables and devices. Wireless signals attenuate around metal structures and dense flocks, generating blind zones and intermittent connectivity. Field studies in broiler and layer facilities report substantial proportions of unusable data due to missing timestamps, duplicated records or out-of-range values, highlighting the need for robust preprocessing and data-quality monitoring within the twin architecture.

3.2. Layer 2: Edge Computing, Cloud Infrastructure and Data Pipelines

The second layer concerns the movement, aggregation and initial processing of sensor data. Dairy and poultry farms often experience constrained connectivity, making edge and fog computing essential design choices. In dairy barns, data from collars, boluses and milking equipment are captured by local gateways that perform time synchronization, filtering, basic feature extraction and compression before transmitting summaries to a farm server or cloud platform. This reduces bandwidth requirements and enables critical alerts such as calving suspicion, mastitis risk or abnormal rumination to be generated even when connectivity is intermittent.

In poultry houses, the volume of image and audio data makes full-resolution streaming impractical and often unnecessary [

26,

27,

28]. Edge devices equipped with GPUs or NPUs can run computer vision and audio-classification models locally, extracting higher-level features such as flock activity indices, density maps or cough-event counts. These features are then forwarded to central servers or cloud platforms. Fog architectures distribute computation across barn-level nodes and a farm-level gateway, allowing multiple houses on a complex to share processing resources and synchronize their virtual models while maintaining local responsiveness.

Data pipelines must also manage heterogeneity and interoperability. Livestock facilities commonly mix sensors and equipment from different vendors, each using proprietary communication protocols. Without harmonization, the integrative potential of digital twins is undermined. Recent open frameworks, such as generic agricultural digital twin architectures and open-source farm-twin platforms, propose standardized data models and APIs to integrate heterogeneous sensor streams and external data sources. Adoption remains limited, however, and many commercial deployments still rely on bespoke integrations that complicate scaling and cross-farm comparison.

3.3. Layer 3: Mechanistic, Statistical and Hybrid Models

The modelling layer transforms sensor data into estimates of latent states and predictions of future trajectories. In dairy systems, digital twins draw on mechanistic nutrition and physiology models such as the Cornell Net Carbohydrate and Protein System and the NASEM nutrient-requirement models. These frameworks describe how feed intake and composition are partitioned into maintenance, growth, pregnancy, lactation and body reserves. They can be parameterized using individual characteristics such as body weight, parity, days in milk and milk composition, then updated continuously with observed behavior and production to estimate dynamic energy balance and metabolic risk.

For health monitoring, statistical and machine-learning models are increasingly used to predict events such as mastitis or lameness from multisensor time series. Studies using combinations of milk yield, electrical conductivity, activity, rumination and internal temperature have reported sensitivity exceeding eighty to ninety percent, demonstrating the potential for early, model-based alerts within dairy digital twins. Rumen-bolus data have been used to characterize drinking behavior, detect fever and identify digestive disorders before clinical signs, providing an additional data stream that feeds probabilistic estimators of health states.

In poultry, modelling focuses on growth, thermal comfort and flock-level performance [

26,

27,

28]. Broiler growth curves are often modelled with Gompertz or logistic functions that can be updated dynamically with inline or platform weight measurements. Thermal comfort models link temperature, humidity, airflow and age to welfare indices, mortality risk and growth performance. FCR trajectories are modelled using time-series or machine-learning approaches that relate feed use and weight gain to microclimate and management variables. Recent poultry digital twins combine these growth and climate models with computer-vision-derived indices such as spatial uniformity and resting behavior, creating richer virtual representations of flock state.

Hybrid modelling that combines mechanistic structures with machine learning is emerging as a promising direction. Mechanistic thermophysiological models can provide physically plausible bounds for learning algorithms, improving robustness under heat stress or unusual conditions. Similarly, mechanistic rumen or digestion models can constrain learning-based intake predictions and health-risk estimations, enhancing interpretability for farmers and veterinarians.

3.4. Layer 4: Control and Optimization

The fourth layer translates model outputs into actions, closing the loop between virtual predictions and farm management. In dairy systems, most commercial applications remain at the level of alerts and recommendations, flagging animals at risk of mastitis, identifying cows in estrus or suggesting ration changes. Some components already support semi-automatic control, such as dynamic concentrate allocation systems that adjust individual feed levels in real time based on predicted energy balance, milk yield and days in milk. A fully realized dairy digital twin could simulate alternative feeding or grouping strategies and recommend those that optimize production, health and emissions under specified constraints.

In poultry houses, closed-loop control is more advanced in climate and feeding systems [

26,

27,

28]. One digital system in commercial broiler houses combined long short-term memory neural networks with a genetic algorithm to generate daily action plans. The system predicted outcomes such as feed conversion ratio and mortality under different ventilation and feeding strategies, then selected plans that improved performance while respecting operational constraints. In field trials, this digital system achieved improved FCR compared with specialist-configured conventional plans, illustrating the potential of digital-twin-style control strategies.

Optimization in both species is inherently multiobjective, requiring trade-offs between production, welfare, environmental impact and economic performance. Multiobjective optimization algorithms and model predictive control frameworks are therefore natural tools within this layer, especially when coupled with scenario analysis for robustness under uncertainty in feed prices, weather patterns or emerging health risks.

3.5. Layer 5: Interfaces, Visualization and Human Interaction

The fifth layer concerns the interfaces through which farmers, veterinarians and advisors engage with the digital twin. Interface design strongly influences adoption and effective use. Dashboards designed primarily by engineers may expose technical metrics and dense time-series plots that overwhelm farm managers. Farmer-centered design consistently emphasizes the need for simple, actionable information such as clear alerts, prioritized task lists and concise explanations.

In dairy systems, dashboards commonly present lists of animals requiring attention with options to inspect underlying sensor trends. Digital twins can extend this by visualizing predicted trajectories, such as projected milk yield under alternative feeding strategies, and by providing interactive tools to explore hypothetical scenarios. Early work on augmented reality suggests future interfaces in which farmers viewing a pen through a tablet or smart glasses could see twin-derived indicators, such as health risks or environmental stress, superimposed on the physical scene.

In poultry houses, dashboards summarize temperature, humidity, ammonia concentration, feed and water consumption and computer-vision-derived activity indices [

26,

27,

28]. When embedded within twin frameworks, these dashboards can show predicted effects of modifying set points or stocking density, helping managers evaluate trade-offs between growth, welfare and energy use. Studies of farmer attitudes indicate concerns about opacity and over-reliance on black-box systems, highlighting the importance of explainability. Trust is strengthened when systems provide interpretable rationales for alerts, rather than opaque notifications.

Figure 1.

Schematic architecture of a livestock digital twin for dairy and poultry.

Figure 1.

Schematic architecture of a livestock digital twin for dairy and poultry.

4. Dairy Applications

4.1. Health Monitoring and Mastitis

Digital twins for dairy cows build on disease-detection capabilities developed within precision monitoring systems, with mastitis serving as a central test case due to its prevalence and economic significance. Machine-learning models trained on multisensor data, combining milk yield, electrical conductivity, milking interval, activity, rumination and internal temperature, consistently outperform single-indicator thresholds for mastitis detection [

30]. Recent studies using on-farm sensor streams reported sensitivities above eighty to ninety percent and specificities between seventy and eighty-five percent when evaluated against veterinary diagnoses or somatic cell count thresholds [

31]. These models commonly apply logistic regression, random forests or gradient-boosted trees, and more recent work explores deep-learning architectures capable of capturing complex temporal patterns in milk and behaviour data.

Rumen-bolus technology extends health monitoring into the internal environment of the cow. Continuous intra-ruminal temperature and pH records allow detection of drinking events, circadian rhythms and deviations associated with inflammation or digestive disturbance. Studies show that sustained elevation of rumen temperature above individual baseline values can precede clinical signs of fever and reduced intake, providing early warning of infectious disease, while prolonged pH depression signals risk of subacute ruminal acidosis [

32,

33]. When bolus data are fused with behavioural and milk-production traits, the resulting multimodal profiles support estimation of latent health states such as subclinical inflammation or digestive instability that influence disease risk and performance loss [

34].

Together, these elements form the health core of a dairy digital twin. The twin assimilates continuous streams from milking systems, wearables and rumen boluses, uses trained classifiers to estimate probabilities of mastitis or acidosis and projects the likely impact on milk yield and welfare if no intervention occurs. Instead of relying on single thresholds, the twin maintains an evolving, individualised baseline for each cow and flags deviations that are statistically unlikely given her history and physiology. Such a twin can also simulate intervention scenarios, such as early treatment, modified milking frequency or ration adjustment, and present predicted trajectories to the farmer, shifting mastitis management from reactive treatment toward proactive risk mitigation.

4.2. Metabolic and Reproductive Health

Digital twins can strengthen monitoring of metabolic and reproductive disorders that cluster around the transition period and early lactation, when cows experience negative energy balance and heightened disease susceptibility. Subclinical ketosis, displaced abomasum and fatty liver are often preceded by characteristic changes in intake, activity and milk composition that are difficult to discern without integrated analytics. By combining rumination time, lying behaviour, activity indices, milk fat-to-protein ratio and internal temperature, models can estimate daily energy balance and assign risk scores for metabolic disease, enabling earlier intervention or nutritional adjustment [

34].

Estrus detection remains a major application of activity monitoring, and digital twins provide a framework for integrating multiple signals to improve timing and reliability. Accelerometer collars and leg-mounted sensors capture increased locomotion during oestrus, while rumination typically declines. When combined with subtle shifts in milk yield and, where available, hormone proxies, estrus-detection algorithms can achieve sensitivities above eighty percent with acceptable false-positive rates [

35,

36]. Embedding these models within a twin allows predictions to be contextualised by parity, days in milk, fertility history and current metabolic state, generating more nuanced recommendations, for example distinguishing cows physiologically ready for breeding from those expressing estrus while still at high metabolic risk.

Because metabolism and reproduction are tightly linked, hybrid digital twins that track both domains simultaneously are particularly promising. Mechanistic energy-balance models can be driven by observed intake proxies and milk output to estimate body-reserve dynamics, while statistical models estimate probabilities of estrus expression, conception and early embryonic loss. The twin can simulate alternative management strategies, such as delaying insemination, modifying body-condition targets or adjusting transition rations, and project their impacts on milk yield, calving interval and culling risk.

4.3. Precision Nutrition and Feed Efficiency

Feed is the largest variable cost in dairy farming and a major contributor to environmental impact, making precision nutrition a central application of digital twins. Conventional rations are formulated at herd level despite substantial variation in intake capacity, production potential and health status among cows. Mechanistic nutrition models such as the Cornell Net Carbohydrate and Protein System and the NASEM nutrient-requirement models link nutrient intake to milk yield, body reserves and maintenance, providing a foundation for individualised nutritional simulation [

37]. When parameterised with cow-specific data, including body weight, parity, days in milk and milk composition, and updated continuously with intake and behavioural proxies, these models enable a twin to estimate each cow’s current and predicted energy balance.

Dynamic concentrate-feeding systems are early implementations of individualised feeding. These systems calculate concentrate allowances in real time based on predicted energy requirements, observed milk yield and production targets. Improvements in feed efficiency and reductions in concentrate use have been reported when such systems are correctly configured, although outcomes vary with management context [

37,

38]. A digital twin extends this by simulating responses to dietary changes before implementation, for example testing how increased starch, supplemental fat or methane-reducing additives might influence milk yield, body condition and rumen health over the next several weeks.

Digital twins also link nutritional strategies to greenhouse-gas outcomes. By integrating intake, milk yield and manure-production predictions with emissions models, a twin can show how ration changes shift methane intensity per litre of milk. Pilot greenhouse-gas tracking systems in several regions have demonstrated that feed-efficiency gains often provide simultaneous economic and environmental benefits, while more aggressive methane-suppression strategies require balancing production outcomes with metabolic stability.

4.4. Environmental Control and Emissions Management

Barn climate influences dairy cow welfare, health and productivity, especially under intensifying heat stress. Digital twins that link environmental sensor data such as temperature, humidity, airspeed and solar load with behavioural and physiological indicators, including panting scores, lying time and intake patterns, can estimate heat-stress risk at both cow and pen level [

39]. Such twins can simulate changes in ventilation settings, shade structures, cooling systems and stocking density to evaluate their effects on predicted body temperature and milk production.

Practical implementations often involve advanced climate-control algorithms that adjust fans, sprinklers and inlet openings based on both current conditions and predicted heat load. While many systems operate at barn level, digital twins extend this by modelling heterogeneous responses among cows and identifying individuals that remain at risk even when overall barn conditions appear acceptable. This animal-centred view supports targeted interventions such as moving susceptible cows to cooler pens or adjusting ration energy density during heat waves.

Environmental digital twins can also be coupled with greenhouse-gas accounting. Integrating predicted manure output from nutritional twins with storage-temperature profiles and handling schedules enables estimation of methane and nitrous oxide emissions under alternative manure-management strategies. A recent greenhouse-gas tracking concept for dairy farms combines these elements into a unified platform that estimates current emissions and evaluates the mitigation potential of interventions such as diet reformulation, manure cooling or anaerobic digestion. Although still at prototype stage, such twins illustrate how environmental and nutritional components can be merged to support productivity, welfare and climate objectives.

Table 1.

Representative near-digital-twin and digital-twin–inspired systems relevant to dairy and poultry.

Table 1.

Representative near-digital-twin and digital-twin–inspired systems relevant to dairy and poultry.

| Species |

System / Study |

Core Sensors and Data Sources |

Model / Analytics Approach |

Maturity (Concept / Prototype / Twin-Inspired) |

Reported Capabilities (Not Full Twins) |

Evidence Type |

| Dairy |

On-farm data integration platform (Brown-Brandl et al.) [21] |

Milking robot data (yield, conductivity, flow), activity and rumination sensors, barn climate (temperature, humidity, gases) |

Hybrid mechanistic and data-driven analytics for production, health, climate |

Twin-inspired system; no continuous bidirectional coupling |

Demonstrated integration of heterogeneous real-time streams into a unified herd/barn dashboard; illustrative health and environmental monitoring use cases [21] |

Field case studies |

| Dairy |

Mastitis risk-prediction ML systems (Steeneveld et al.) [31] |

Milk yield, conductivity, milking interval, activity, rumination, parity, days in milk |

Supervised ML classification models |

Decision-support tool; not a twin |

Sensitivity above 80–90 percent and specificity around 70–85 percent for mastitis detection versus clinical diagnosis or SCC thresholds [31] |

Retrospective and prospective evaluations |

| Dairy |

Rumen-bolus health monitoring prototypes (Hajnal et al.) [23,33] |

Rumen boluses (temperature, pH), accelerometry, milk-yield data, climate sensors |

Time-series analytics and probabilistic health-state estimation |

Prototype physiological-monitoring systems; not twins |

Early warning of fever, acidosis and intake disruption; proof of life-long in-animal sensing [23,33] |

Pilot deployments |

| Dairy |

Precision feeding and nutrition decision-support tools (Bach; CERC GHG concepts) [35,36,37] |

Milk yield, components, body weight, BCS, feeding-station logs, ration composition, manure output |

Mechanistic nutrition and energy-balance models with scenario simulation |

Simulation and decision-support systems; not twins |

Improved concentrate allocation in some herds; ability to test nutritional and methane-mitigation strategies in silico [35,36,37] |

Field experiments and simulations |

| Poultry |

Broiler FCR optimisation system (Klotz et al.) [44,45] |

House climate (temperature, humidity, ventilation), stocking density, feed and water use, management actions |

LSTM predictive model plus genetic-algorithm planner |

Twin-inspired optimisation system; partial closed-loop |

Improved feed conversion ratio in limited commercial pilots; multi-house adaptive planning [44,45] |

Field trials |

| Poultry |

IoT/ML welfare-monitoring framework (Ojo et al.) [40] |

Environmental sensors (temperature, humidity, ammonia, CO2, light), cameras, microphones |

Modular IoT/ML architecture linking environment, behaviour and welfare |

Conceptual framework; not a twin |

Illustrates how multimodal sensing and analytics could feed a virtual welfare model [40] |

Concept + small prototypes |

| Poultry |

Production-system twin concept (Adejinmi et al.) [41] |

House-climate sensors, feed/water meters, production and logistics records; optional vision/audio |

System-of-systems architecture covering health, nutrition, environment and economics |

Conceptual digital-twin vision |

Roadmap for flock-level integration across the production cycle [41] |

Framework descriptions |

| Poultry |

IoT house-environment platform (Jia et al.) [49] |

Distributed temperature, humidity and gas sensors; feed/water meters; optional cameras |

Cloud-based analytics and rule-based control |

Infrastructure for potential twin development; not a twin |

Real-time climate monitoring and automated control; foundation for future twin integration [49] |

Field deployment |

7. Evidence Gaps

Digital twins for dairy and poultry are advancing rapidly at the conceptual and prototype levels, yet the empirical evidence base remains narrow and uneven. Three gaps are particularly salient: the scarcity of robust field trials for key outcomes such as feed conversion, the near absence of systematic reporting on system failure and abandonment and the limited but revealing qualitative work on farmer perceptions and adoption barriers. Together, these gaps constrain movement from hype to verifiable evidence and limit the credibility of livestock twins as practical tools.

7.1. Limited Field Validation for Feed Conversion and Growth

Despite widespread claims that digital twins can improve feed efficiency, there is remarkably little field-validated evidence documenting feed conversion improvements in commercial poultry. The multi-house long short-term memory plus genetic-algorithm system developed by Klotz and colleagues remains the only peer-reviewed study reporting flock-level feed conversion gains from a twin-like control architecture under commercial conditions. Other Internet-of-Things and machine-learning studies for broilers and layers focus on predicting growth or final performance from environmental and management variables, but these typically operate offline or remain in simulation without closing the loop through on-farm control. No additional field trials have demonstrated statistically robust, repeatable improvements in feed conversion attributable specifically to digital twins, leaving a pronounced gap between marketing narratives and documented performance.

In dairy systems, evidence for feed-efficiency or methane-intensity improvements attributable to digital twins is similarly sparse. Precision feeding and decision-support systems based on mechanistic models show that individualized concentrate allocation can improve efficiency in some contexts, but these studies usually predate explicit twin terminology and rely on simpler rule-based algorithms rather than continuously updated virtual cows. Recent greenhouse-gas tracking concepts for dairy digital twins integrate ration, production and manure data into farm-level carbon dashboards, yet controlled trials comparing emission trajectories under twin-supported and conventional management remain rare. The absence of longitudinal, controlled evaluations means that mitigation claims for dairy and poultry twins continue to rely primarily on extrapolation and simulation rather than replicated field evidence.

7.2. Missing Data on Failure, Downtime and Abandonment

A second cross-cutting gap concerns the reporting of failures. Reviews of precision livestock farming and digital agriculture repeatedly note that published studies rarely include detailed statistics on sensor failure rates, communication outages, data-loss percentages or system downtime. When technical issues are mentioned, they are typically described qualitatively, such as intermittent connectivity or occasional sensor malfunction, without quantifying frequency, duration or analytic impact. The cybersecurity roadmap for digital livestock farming explicitly remarks that systematic documentation of system failures, including non-malicious outages and user-driven discontinuation, is almost entirely absent from scientific literature.

For digital twins, which depend on continuous bidirectional coupling between physical and virtual systems, this lack of reliability data is especially problematic. Without transparent reporting on how often sensors drop out, models require re-initialization or control recommendations are overridden or ignored, it is impossible to assess operational robustness in commercial barns. Early adopters report that failed or abandoned precision livestock systems are common, often due to maintenance burdens, vendor discontinuation or misalignment with farm routines, yet these experiences rarely appear in peer-reviewed papers or vendor documentation. This publication bias risks creating an overly optimistic view of twin viability and obscures essential design and support requirements for long-term use.

7.3. Under-Explored Farmer Perspectives and Social Dimensions

The social science literature on livestock digitalization lagged behind technical development for many years, but recent studies provide insight into how farmers perceive and negotiate precision technologies. Interviews and focus groups with European dairy farmers adopting or considering precision livestock systems highlight concerns about data ownership, lock-in, workload and trust in algorithmic recommendations [

57]. Some farmers report that technologies marketed as labor-saving instead increase cognitive burden by generating more alarms and dashboards to monitor, while others fear that sensor-based scoring of welfare or environmental performance may be used by processors or retailers to impose compliance demands without commensurate price premiums.

Reviews of precision poultry farming adoption indicate a similar gap between integrator enthusiasm for data-rich monitoring and growers’ reservations about autonomy, opaque decision rules and unclear value propositions [

57]. Studies in the United Kingdom and Europe show that growers view digital tools as potentially useful but emphasize that adoption requires demonstrable reductions in stress, workload or risk, along with clear procedures for assigning responsibility when automated recommendations conflict with farmer judgement. Very few digital-twin projects have incorporated participatory design or co-created evaluation metrics with farmers, veterinarians or workers, raising the risk that new twin systems will reproduce the same adoption barriers encountered earlier waves of precision livestock technologies.

9. Future Directions: Reference Farms and Green AI

Digital twins for dairy and poultry now face a pivotal moment, as the next decade must shift from proofs of concept toward independently evaluated, energy-efficient systems that demonstrably earn their carbon and welfare claims. Two strategic directions stand out: establishing multi-site reference farms for rigorous evaluation and embedding Green AI principles into perception and modelling so that twins are effective and computationally frugal [

52,

55,

60,

61,

62,

63,

64].

9.1. Reference Farms for Hard Evidence

A coordinated network of reference farms would provide the empirical backbone that livestock digital twins currently lack. These farms would function as living laboratories that host complete twin stacks from sensors and edge devices through models and control algorithms, operated over at least twenty-four months to capture seasonal variation and management changes. In dairy, a realistic configuration could include eight to ten farms per region, stratified by herd size, housing type and milking technology, with two hundred to four hundred cows per farm contributing data through milking systems, behaviour sensors and environmental monitors. In poultry, twenty to thirty houses across several complexes, spanning distinct climates and genetic lines, could host climate, welfare and feed-conversion twins across a minimum of six flock cycles per house, providing adequate statistical power for flock-level outcomes.

These reference farms would collect harmonized metrics covering production, including milk yield, feed conversion, growth and mortality; health and welfare, including clinical events, behaviour-based scores and injury indicators; environmental performance, including enteric and manure emissions and energy use; economics, including capital and operating costs and labor use; and digital-system performance, including uptime, sensor-failure rates, latency, model error and the energy consumption of edge and cloud components. This evidence base would enable robust comparisons between periods or units with and without twin support, using quasi-experimental or causal-inference designs rather than simple before–after anecdotes.

Reference farms also create a platform to institutionalize the Green AI arithmetic proposed for agricultural AI. This approach argues that systems should demonstrate that emissions avoided on farm exceed emissions generated by model training, inference and hardware manufacture and disposal [

60,

61,

62,

63,

64]. By logging the energy use of perception models, communication networks and servers, and combining this with farm-level mitigation data, reference farms can quantify whether a given twin is climate-positive, climate-neutral or climate-negative over a defined timeframe. This would operationalize recent proposals for standardised reporting of AI energy and carbon metrics in livestock systems, including transparent disclosure of training energy, inference energy, hardware lifetimes and embodied emissions [

60,

61,

62,

63,

64].

To be credible and widely accepted, reference farms should be governed through partnerships between farmers, researchers and technology providers rather than as proprietary testbeds. Work on sustainable computing for digital livestock and Green AI governance emphasizes the importance of open protocols, independent auditing and shared data-access arrangements that prevent lock-in and enable third-party re-analysis [

55,

60,

61,

62,

63,

64]. Embedding participatory impact-assessment methods, including interviews, focus groups and co-design workshops, would ensure that evaluations capture not only productivity and emissions but also labor burdens, autonomy, fairness and the distribution of benefits and risks along the value chain.

9.2. Green AI and Energy-Efficient Perception

The second opportunity lies in redesigning perception and modelling pipelines so that livestock digital twins respect planetary boundaries. Recent work on Green AI for livestock perception synthesises efficient architectures, multimodal sensing strategies and deployment practices, arguing that energy use and carbon intensity must be treated as primary performance criteria rather than afterthoughts [

60,

61,

62,

63,

64]. This research shows that many computer-vision and acoustic models used for lameness detection, body-weight estimation or poultry vocalisation analysis are significantly over-parameterised relative to the complexity of barn environments, resulting in unnecessary compute and energy consumption during training and inference. Conceptual analyses of Green AI in livestock systems further show that cumulative emissions from training large models and running them continuously across farms can be substantial, and that without explicit constraints, digital livestock systems may drift beyond safe planetary boundaries while claiming mitigation benefits.

A concrete set of design levers is now available. Model-compression techniques such as pruning, low-precision quantisation and knowledge distillation can reduce parameter counts and memory footprints by an order of magnitude, often with minimal loss of detection accuracy when guided by task-specific validation [

60,

61,

62,

63,

64]. Lightweight architectures, including depthwise-separable convolutional networks and compact transformer variants, enable on-device inference on low-power edge hardware while still capturing salient visual and acoustic cues required for health and behaviour monitoring. Work on energy-efficient edge AI for environmental monitoring demonstrates that moving inference to the edge and transmitting only high-level events can significantly reduce communication energy and data-centre load, benefits that are directly transferable to barn contexts.

Hybrid cloud–edge strategies also offer promising gains. The Green AI arithmetic framework emphasises that scheduling non-urgent analytics during periods of high renewable generation and running only time-critical inference locally can reduce total energy use by roughly one third and associated emissions by up to half, depending on electricity mix and workload [

60,

61,

62,

63,

64]. Sustainable computing frameworks for digital livestock argue that architectural choices, including where models are trained, how often they are updated and which features are computed at the edge rather than in the cloud, should be explicitly optimised against both performance and carbon budgets. Reference farms create the ideal environment for benchmarking such configurations, comparing camera-heavy twins with sparse-sensor or audio-first designs on a joint axis of welfare gains and digital footprint.

Finally, recent proposals for a standardisation roadmap for energy-efficient AI in livestock agriculture call for sector-wide metrics and reporting conventions. These include normalising energy use to functional units such as kilowatt-hours per monitored cow-day or grams of carbon dioxide equivalent per million predictions, defining acceptable trade-off curves between model accuracy and energy use and encouraging shared, open models and datasets so that training emissions are amortised across many users rather than duplicated across proprietary implementations [

60,

61,

62,

63,

64]. Coupled with governance principles from Green AI and sustainable computing, such standards would encourage vendors to compete not only on accuracy and features but also on energy and carbon performance.

In combination, reference farms and Green-AI-aware design can move livestock digital twins from speculative promise toward verifiable, fair and climate-conscious practice. The central challenge is not only to build more intelligent models, but to ensure that their intelligence is demonstrably worth the environmental and social cost [

52,

55,

60,

61,

62,

63,

64].

10. Conclusions

Digital twins for dairy and poultry are advancing rapidly in concept yet remain early in practice. Across species and production systems, the promise of continuously updated virtual counterparts that anticipate disease, optimise nutrition, fine-tune climate control and reduce emissions is compelling. However, the empirical foundation supporting these claims is still thin. Field-validated improvements in feed efficiency are limited to a small number of broiler trials, and no multi-year, multi-site evidence yet demonstrates that digital twins measurably improve milk yield, reduce methane intensity or stabilise welfare outcomes. Likewise, systematic reporting of failure rates, downtime and abandonment remains almost absent, leaving system robustness largely unknown. In many cases, the most optimistic narratives are sustained by simulation studies rather than by data from commercial barns.

At the same time, the digital infrastructures that animate twins carry material and energy costs that are rarely factored into assessments of climate benefit. Without transparent accounting of these costs, there is a risk that systems marketed as climate solutions may in practice shift energy burdens from barns to cloud platforms. The rise of Green AI highlights that performance must be evaluated alongside carbon intensity, and that lightweight, efficient architectures are essential if digital livestock technologies are to remain aligned with planetary boundaries.

Adoption dynamics further complicate the picture. Farmers across dairy and poultry systems emphasise that technologies must reduce labour, risk or cognitive load, yet many current prototypes increase the complexity of daily routines. Concerns about data rights, vendor lock-in and opaque decision pathways intersect with structural imbalances in value chains, particularly in poultry, where growers have limited leverage over data governance and platform access. Trust, transparency and independent evaluation are therefore as central to the future of livestock digital twins as any algorithmic advance.

The path forward is clear. Rigorous evidence requires reference farms that instrument full twin stacks and follow them through multiple cycles, documenting not only production and welfare effects but also system failures, energy use and carbon footprint. Green-AI-aware design must guide the development of perception and modelling pipelines so that twins earn their environmental claims through measurable efficiency, not by offloading computation to external infrastructures. And governance frameworks must ensure that benefits and risks are distributed fairly across farmers, integrators and technology providers.

Digital twins will not transform livestock systems through technical novelty alone. Their value will depend on whether they can deliver sustained improvements in health, welfare, efficiency and environmental performance under real commercial conditions while respecting the constraints of farm labour, energy use and data sovereignty. The next decade will determine whether twins mature into credible, climate-aligned tools for dairy and poultry production or remain compelling prototypes awaiting evidence. The challenge is not merely to build smarter systems, but to build systems that are demonstrably worth their environmental, economic and social cost.