1. Introduction

Entrepreneurship, as a dynamic of contemporary societies, has a positive impact on the economic growth, development and competitiveness of countries (Alcaraz & García, 2016; Pedrosa, 2015; Tarapuez et al., 2018). This recognition has sparked academic interest from various perspectives (Sánchez, 2011; Obschonka et al., 2017), generating a consensus on the need to promote entrepreneurial activity in contemporary societies (López Puga, 2012). In this vein, it has been proposed that entrepreneurship should be taught from the early stages of the education system (European Commission, n.d.), which is why its inclusion in school education has been identified as a key factor in its promotion (Huber et al., 2014).

The effectiveness of entrepreneurship education has attracted a series of studies from social psychology that have focused on assessing entrepreneurial intention (EI) in university students, increasingly in recent years (Rubio & Lisbona, 2022), and less frequently in secondary school students (adolescents) or children (Martínez-Gregorio & Oliver, 2022; Torres-Ortega et al., 2024). Ajzen's Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) (1991) has been widely used to explain EI, providing empirical evidence on the role of cognitive variables such as attitude toward entrepreneurship, subjective norm, and perceived behavioral control in shaping such intention (Liñán & Fayolle, 2015; Hernández Muñoz et al., 2025; Moriano et al., 2012).

Along the same lines, developing countries have seen a sustained increase in research measuring EI in university students (Rubio & Lisbona, 2022), taking into account the benefits of entrepreneurial activity. However, the school system has begun to establish itself as a relevant space for the early development of entrepreneurial skills, with evidence showing that participation in educational programs at this stage increases interest and the likelihood of becoming involved in entrepreneurial initiatives (Elert et al., 2015; Torres-Ortega et al., 2024).

The Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) in its 2024 global report highlights Chile as the best-rated country in Latin America and the Caribbean, ranking 21st out of 49, with physical infrastructure and government policy among the best-rated aspects. However, education for entrepreneurship, both in Chile and in other countries, continues to be poorly rated. Added to this is a decline in the intention to start a business, reaching its lowest point since 2010, mainly attributed to fear of failure (Diario Financiero, 2025).

This background reinforces the need to strengthen entrepreneurial training from an early age, highlighting the strategic role of the school system in promoting skills associated with entrepreneurship. In this regard, compulsory early education requires greater research attention (Do Paço & Palinhas, 2011), particularly through the design and validation of instruments adapted to the school context that allow for the adequate measurement of EI in adolescents (Ortuño-Sierra et al., 2021).

The purpose of this study is to validate an instrument for measuring EI in a sample of secondary school students in Chile. To this end, we first present the conceptual basis for the constructs and scales used; then we describe the methodology, including the design of the instrument, the sample, and the analysis procedures; then reports the psychometric results (confirmatory factor analysis, reliability, convergent and discriminant validity); discusses the findings and their implications; and finally presents the conclusions and projections for future research.

1.1. Theoretical Background

The study of entrepreneurial behavior and intentions has drawn on approaches from psychology to identify and understand the profile of people who decide to become entrepreneurs. In particular, Ajzen's (1991) TPB (Theory of Planned Behavior) has been adapted to the field of entrepreneurship to explain how attitude, subjective norm, and perceived behavioral control shape EI, acting as predictors of entrepreneurial behavior in various contexts (Pihie & Bagheri, 2010; Lepoutre et al., 2010; Purwana et al., 2017; Sambo, 2018; Briseño-Aguirre et al., 2024).

Other individual psychological factors that influence entrepreneurial propensity have been added to TCP, such as achievement orientation, risk propensity, autonomy, self-efficacy, innovation, stress tolerance, internal locus of control, and self-confidence (Liñán, 2008; Liñán & Chen, 2009; Kolvereid, 1996; Hu & Ye, 2017; Torres, 2020; Krueger, 2003). However, it has also been shown that contextual factors play a significant role in the development of entrepreneurial activity (Moriano et al., 2012; Monreal Garrido, 2014; Orellana & Martinez de Lejarza, 2013). In turn, their contribution to the early development of competencies that promote competitiveness in developing countries is highlighted (Cera et al., 2020; Duong et al., 2021).

School contexts, particularly those that incorporate Entrepreneurial Education (EE) programs as strategies to promote human capital and employability (Zdolsek Draksler & Sirec, 2021), are relevant for studying EE in adolescents for two fundamental reasons. First, because it is a key stage of development for the formation of entrepreneurial attitudes and the acquisition of skills (Peterman & Kennedy, 2003); and second, because of the transformative potential of EE in terms of the ability to identify opportunities, foster vision and self-confidence, and develop skills to act accordingly (Lacobucci & Micozzi, 2012). According to Fayolle et al. (2006), EE encompasses any educational program aimed at fostering entrepreneurial attitudes and skills. Along the same lines, Sánchez (2013) highlights the predictive value of entrepreneurial skills as a first step toward business creation (Liñán & Chen, 2009).

Despite growing interest in the phenomenon, studies addressing the factors that influence EI in secondary school students remain limited (Do Paço et al., 2015). Vocational development theories (Porfeli et al., 2013) reinforce the relevance of studying this stage, as adolescence and the transition to adulthood represent critical moments in the formation of interests, identity, and career paths (Furdui et al., 2021; Garrido-Yserte et al., 2020; Geldhof et al., 2014; Shahin et al., 2021).

Consequently, there is a need to design and validate instruments that consider a broader spectrum of variables related to EI, beyond individual psychological factors (Rubio & Lisbona, 2022), and including dimensions such as emotional competencies and participation in training programs (Fu et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2022; Sánchez, 2013).

1.2. Entrepreneurial Intention and the School Context

The study of EI in school students, especially in contexts of technical and vocational training, is relevant for capacity building to start businesses and improve employability, promoting competitiveness in countries with low structural competitiveness and high youth unemployment (Cera et al., 2020), due to its influence on the development of skills required for self-employment (Torres y Monzón, 2021). Despite the limited attention given to this stage of education (do Paco et al., 2011), some research has confirmed that school EE has a positive impact on the core variables of TCP: entrepreneurial attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control (Martínez-Gregorio & Oliver, 2022; Aragón-Sánchez et al., 2017). However, additional factors such as institutional support (Urban & Kujinga, 2017) or the social value of entrepreneurship (Fernández-Pérez et al., 2019), which have been studied at the university level, have been neglected.

There are numerous studies with samples of university students that have explored the relationship between EE programs on IE where it is not possible to observe conclusive results (Kim et al., 2020; Otache et al., 2021; Shahin et al., 2021), or contradictory results are observed. On the one hand, some studies reveal a positive and significant relationship (Otache et al., 2021; Rauch & Frese, 2007; Souitaris et al., 2007; Westhead & Solesvik, 2016), while other studies have shown that, although positive, the relationship is not statistically strong (Karimi et al., 2016; Liñán & Fayolle 2015; Nowiński & Haddoud, 2019), while some researchers have suggested that EI is negatively associated with EE (Nabi et al., 2018; Oosterbeek et al., 2010). Similar results, although significantly fewer in number, are observed in school- cts (Brüne & Lutz, 2020), which reveal that EE does not exert a direct positive influence (Do Paço et al., 2015; Marques et al., 2012; Thompson & Kwong, 2016; Volery et al., 2013), while others do establish this relationship (Athayde, 2009; Atienza-Sahuquillo et al., 2016; Sánchez, 2013), and one even finds no effect (Huber et al., 2014). These discrepancies are attributed to variability in cultural contexts, pedagogical approaches, assessment methodologies, and the mediating effects of other variables (Bae et al., 2014; Shahin et al., 2021).

Cortez and Hauck (2020), in a survey of 676 articles on entrepreneurial intention obtained from Web of Science and SciELO, identified only 13 documents that presented a theoretically grounded proposal for measuring EI, which were grouped into three perspectives: Entrepreneurial Event Theory (Krueger, 1993), Theory of Planned Behavior (Ajzen, 1991; Liñán & Chen, 2009; Moriano et al., 2012), and Temporal Interpretation Theory (Hallam et al., 2016). Of these, the scales designed from the TCP showed more detailed conceptual work along with reports of adequate internal validity and consistency, demonstrating greater theoretical robustness and capacity to capture empirical evidence, making them preferable for intercultural adaptations in diverse contexts. In this regard, it is necessary to design theoretically grounded instruments that have been applied in other contexts and that are validated in large study samples. In this regard, the authors found considerable variation in sample size (between 120 and 3,233 students). Considering that sample size is a crucial element for validating the psychometric properties of instruments, thus allowing for more reliable and generalizable analyses that test the internal consistency of the instruments (Cortez & Hauck, 2020, p. 10). Most instruments are based on the TCP in their designs, and there is also a predominance of university students as study populations, given that they represent a key population for studying entrepreneurial potential (Cortez & Hauck, 2020).

Findings on the effects of EE remain heterogeneous, with positive, null, and even negative results depending on context, approach, and assessment method (Brüne & Lutz, 2020), underscoring the need for theoretically grounded and psychometrically robust instruments for the school level (Souitaris et al., 2007; Oosterbeek et al., 2010; Nabi et al., 2018; Brüne & Lutz, 2020). On this basis, the present study justifies the construction and validation of an instrument for Chilean secondary school students that integrates the core components of CBT and these complementary variables, adapted linguistically and culturally, and whose quality is evaluated using standard criteria (KMO and Bartlett; loadings ≥ 0.708; AVE ≥ 0.50; discriminant validity via Fornell-Larcker and HTMT; and diagnosis of multicollinearity with VIF), enabling its subsequent use in structural equation modeling (SEM) and in the evaluation of EE programs in school contexts, allowing for semantic adaptations to other sociocultural contexts that can contribute to the gathering of evidence on the relationship between EE and EI, thereby strengthening the theoretical discussion in this field.

2. Materials and Methods

This study aims to construct and validate an instrument to measure entrepreneurial intent in Chilean secondary school students, using the Theory of Planned Behavior (Ajzen, 1991) and recent evidence linked to factors associated with entrepreneurial intent, integrating psychological and contextual variables into a single instrument. A linguistic and cultural adaptation to the Chilean school context was carried out, and the application process followed the ethical guidelines of the institution hosting the research project. The instrument's design, sample characteristics, and the analytical strategy that support its metric quality and subsequent use in applied research are presented below.

2.1. Design of the Measurement Instrument

For the design of the measurement instrument, an exhaustive review of the literature related to entrepreneurial intention was carried out, identifying sixteen constructs related to the phenomenon of entrepreneurship with their respective measurement scales. The questionnaire by Liñán & Chen (2009) was taken as the main reference for the core constructs of the Theory of Planned Behavior (Ajzen, 1991) (entrepreneurial intention, attitude, subjective norm, and perceived control), ensuring compatibility with internationally validated instruments. Additionally, items from other published instruments were incorporated for the additional constructs: for example, scales of entrepreneurial self-efficacy from Chen et al. (1998), entrepreneurial ecosystem (Kolvereid, 1996; Sánchez, 2013), entrepreneurial alertness (Tang et al., 2012), and innovation capacity (Hu & Ye, 2017), traits such as need for achievement (Carter et al., 2003), internal locus of control (Craig et al., 1984), risk propensity (Ferreira et al., 2012), ability to recognize opportunities (Kim et al., 2020), proactivity (Bateman & Crant, 1993), leadership (Athayde & Hart, 2012), optimism (Scheier & Carver, 1985), and social value (Fernández-Pérez et al., 2019). The items relevant to the study are selected, translated into Spanish, and adapted to the context of Chilean secondary school students, using clear language appropriate to their level.

The final instrument took the form of a 7-point Likert-type questionnaire (1 = strongly disagree and 7 = strongly agree) for each statement, so that students could indicate their degree of agreement with statements referring to each construct. In addition, demographic and contextual variables such as gender, country of origin, age, high school, and grade were recorded.

2.2. Sample and Data Collection

This research was conducted with a sample of 1,402 secondary school students from four high schools in Chile (1: Instituto Comercial Eliodoro Domínguez - 42%; 2: Liceo Politécnico Pedro Aguirre Cerda - 18%; 3: Liceo Industrial de Angol - 28%; 4: Liceo Industrial de Nueva Imperial - 12%). The sample was composed of 68% men, 30% women, 1% non-binary, and 1% who preferred not to specify. In terms of education, the sample was distributed as follows: 33% in 10th grade, 27% in 11th grade, 18% in 12th grade, and 23% in 13th grade. Regarding nationality, 85% of the sample was Chilean, 12% was foreign, and 3% preferred not to specify.

The data was collected through a paper questionnaire administered in the classroom. All students were informed that participation in this study was voluntary and anonymous. The questionnaire included a description of the study's objective and informed consent, following the guidelines of the Institutional Ethics Committee of the University of Santiago, Chile.

2.3. Data Analysis

The data obtained through the instrument were processed and analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics (v.25) and SmartPLS (v.4.0) software, with the aim of evaluating the psychometric validity of the instrument. Initially, the database was cleaned, excluding those responses that had more than 15% of omissions in the total number of items, following established criteria to ensure the integrity and consistency of the information used in subsequent analyses (Hair et al., 2017).

For instrumental validation, a statistical procedure was developed in several stages. In the first phase of analysis, univariate descriptive statistics (mean, median, standard deviation) were calculated for each item and construct, together with the visualization of the distributions of each of them, in order to explore the general behavior of the responses and detect relevant distribution patterns. These analyses allow us to identify central trends and explore possible asymmetries that may be initially observed in the internal structure of the constructs.

For the internal validation of the instrument, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was applied, a technique that allows the empirical comparison of the adequacy of a pre-established theoretical model to the observed data (Byrne, 2010) and which is widely used for the design of structural equation models (SEM); the context in which the present instrumental validation is framed. On the other hand, this methodological decision is based on the deductive nature of the instrument's construction, based on constructs previously defined in the literature and operationalized through reflective items selected from internationally validated scales. Where it is required that, prior to CFA, the adequacy of the sample be evaluated using the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) index and Bartlett's sphericity test. KMO values greater than 0.6 were considered acceptable, as indicated by Kaiser (1974), which indicates that the partial correlations between the items are low enough to justify factor analysis. For its part, the statistical significance (p < 0.05) of Bartlett's test supports the existence of significant correlations between the variables (Bartlett, 1950), a necessary condition for the extraction of common factors. In turn, Bartlett's index is calculated for each construct, which corresponds to the quotient between the chi-square obtained and the corresponding degrees of freedom (which must be greater than 1 to justify an CFA). Confirmatory factor analysis was performed using the principal component estimation method, with Oblimin oblique rotation, given that a correlation between the factors is anticipated due to the nature of the constructs. For the evaluation of factor loadings, a minimum threshold of 0.708 was established, in accordance with individual reliability criteria (Hair et al., 2017), while for communalities, a cutoff point of 0.5 was considered as an indicator of adequacy in the proportion of variance explained (Fornell & Larcker, 1981).

Then, the reliability and internal validity of each construct was evaluated using Cronbach's alpha coefficient and composite reliability (CR), using values greater than 0.7 as acceptance criteria (Nunnally & Bernstein, 1994). Likewise, the average extracted variance (AVE) was estimated to evaluate convergent validity, considering values equal to or greater than 0.5 as acceptable, which indicates that more than 50% of the variance of the items is explained by the underlying construct (Hair et al., 2019).

Finally, a multivariate analysis was performed to demonstrate the existence of discriminant validity between the constructs, using two complementary approaches: the Fornell-Larcker criterion (1981), which compares the square root of the AVE with the correlations between constructs, and the HTMT index (Henseler et al., 2015), which provides a stricter measure of empirical discrimination. As a reference, a threshold of 0.9 was considered for HTMT, which is accepted as acceptable in exploratory contexts or with conceptually related constructs. Additionally, the variance inflation factor (VIF) was calculated for each item to identify those with possible signs of multicollinearity, using a conservative threshold of 3.3 as a reference for acceptable levels (Diamantopoulos & Siguaw, 2006).

This proposed comprehensive methodological strategy allows for the evaluation of the psychometric quality of the instrument in terms of its factor structure, internal reliability, and convergent and discriminant validity, providing sufficient empirical evidence for its use in the structural modeling of entrepreneurial intention.

3. Results

3.1. Design of the Measurement Instrument

After reviewing the literature and evaluating existing constructs and instruments, 69 questions corresponding to 16 constructs were obtained for evaluation (see

Table 1 for more details), where 5 items correspond to the dependent variable of entrepreneurial intention and then for the independent variables: 5 items for entrepreneurial attitude, 3 items for subjective norm, 6 items for perceived behavioral behavior, 6 items for entrepreneurial self-efficacy, 6 items for institutional support, 5 items for entrepreneurial alertness, 4 items for innovation capacity, 4 items for need for achievement, 3 items for internal locus of control, 4 items for risk propensity, 4 items for ability to recognize opportunities, 4 items for proactivity, 3 items for leadership, 4 items for optimism, and 3 items for social value.

3.2. Exploration of the Responses Obtained

In general terms, the arithmetic mean values per item range from 4.237 to 6.207 points on a seven-point scale, while the medians vary between 4.0 and 7.0. This concentration in the upper part of the scale suggests a general tendency toward high levels of agreement with the statements presented, reflecting a favorable disposition of students toward the constructs measured. Particularly high scores are observed in constructs such as need for achievement (NL), subjective norm (NS), and proactivity (PRO), all with means above 5.6. In contrast, constructs such as institutional support (IS) and entrepreneurial alertness (EA) have the lowest mean values, around 4.5. Regarding the dispersion of responses, the standard deviation values range between 1.254 and 1.961, reflecting slight to moderate variability. In general, greater homogeneity is identified in constructs with high ratings (such as subjective norm and need for achievement), while those with lower scores, such as institutional support, tend to show greater dispersion. This indicates that, in the former, perceptions are relatively shared among students, while in the latter there are more diverse or polarized positions.

When analyzing the relationship between medians and means, a high degree of concordance is observed in most constructs, suggesting a symmetrical or slightly right-skewed distribution. However, certain constructs with notable differences between the two measures are identified, such as perceived behavioral behavior (PBB) and entrepreneurial alertness (EA), where the means tend to be slightly lower than the medians, which could indicate asymmetric distributions with a greater bias toward low values. In contrast, constructs such as need for achievement (NL) and optimism (OP) show great alignment between mean and median, reflecting a more symmetrical distribution. Therefore, in summary, it can be observed that asymmetry is more pronounced in constructs with lower overall scores, while those with higher scores are more balanced.

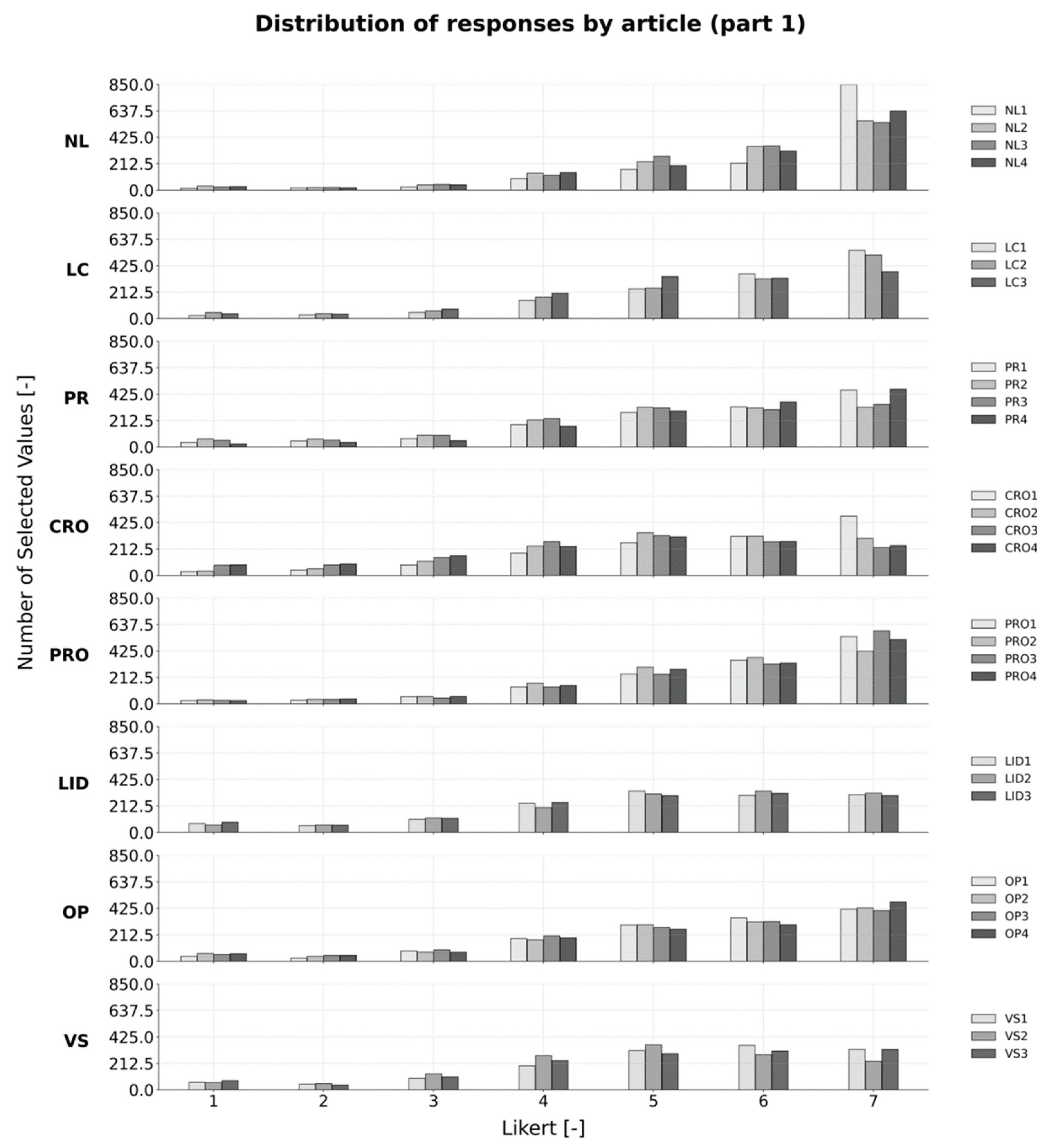

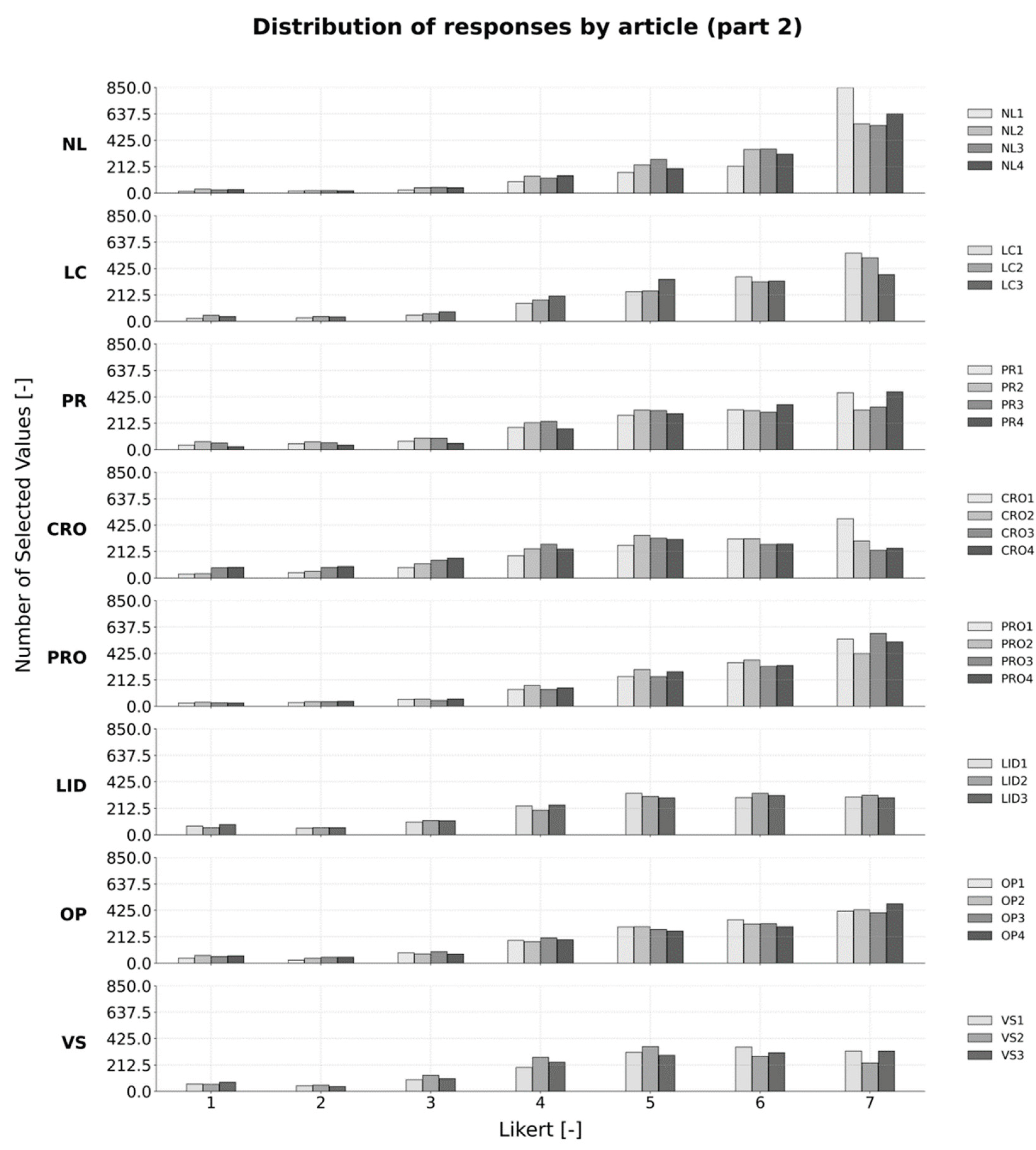

In line with the distribution trends mentioned above,

Figure 1 and

Figure 2 illustrate the distribution of responses per item grouped according to their corresponding construct. In most cases, there is a concentration of responses toward the upper levels of the scale (values 5, 6, and 7). This trend is evident in constructs such as entrepreneurial intention (INT), entrepreneurial attitude (AP), subjective norm (SN), need for achievement (NA), locus of control (LC), and proactivity (PRO), whose items reflect a strong orientation toward positive affirmation. However, some constructs behave differently. Some constructs have a flatter, more distribution with greater dispersion, such as institutional support (IS), entrepreneurial self-efficacy (ESE), and perceived behavioral behavior (PBB), showing greater diversity of perceptions among students. In addition, the figures identify certain items that deviate from the general pattern of their construct. For example, within PBB, item PBB1 shows a higher concentration of responses in values 4 and 5, unlike the rest of the items in the same construct, where levels 6 and 7 predominate. Likewise, other items with a more pronounced distribution towards higher values are observed, such as CRO1 and NL1, suggesting a particularly affirmative trend in those cases.

In addition, it should be noted that most constructs show a growing trend towards high values, with single-tailed distributions (to the left), although there are some notable exceptions. Constructs such as entrepreneurial alertness (AE), ability to recognize opportunities (CRO), leadership (LID), and social value (VS) exhibit more centered and symmetrical distributions, with more pronounced tails at both extremes, denoting greater centrality in their trend among participants.

The descriptive results reflect a pattern of responses that favors the construction of latent variables: the scores are predominantly distributed in the upper segment of the scale, with a good distribution towards trend values in most constructs and a variability that, although moderate, allows for adequate discrimination between differentiated perceptions. Therefore, the consistency between items within most constructs is assessed. However, together with the identification of some items with divergent behavior and variability in some response patterns, some possible negative effects are elucidated, which will be evaluated more precisely when analyzing the underlying structure and internal consistency of the instrument.

3.3. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

In order to validate the latent structure of the designed instrument, a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was performed. This technique allows the relationship between observable items and proposed theoretical constructs to be examined, verifying whether the empirical data are adequately adjusted for the construction of the respective latent variables. It is therefore considered a fundamental intermediate stage in the process of validating psychometric instruments, especially in research aimed at constructing structural equation models (SEM).

To assess the feasibility of applying CFA, the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) sample adequacy index was considered, whose values are generally within the acceptable range, exceeding the recommended threshold of 0.6 in most of the constructs analyzed. This supports the suitability of the data for factor analysis. However, some constructs have marginal values that should be viewed with caution, such as internal locus of control (LC) with a KMO of 0.657, need for achievement (NL) with 0.682, and social value (SV) with 0.702, suggesting a weaker structure in the intercorrelation of their items. Additionally, Bartlett's sphericity test was statistically significant in all cases (p < 0.05), confirming the existence of sufficient correlations between items to justify factor analysis. These values not only support the validity of the AFC applied, but also allow for the creation of composite constructs based on the data obtained.

The factor loadings obtained allow us to assess the contribution of each item to its respective construct. Following common criteria in the literature, a loading equal to or greater than 0.708 is considered acceptable as an indicator of adequate individual reliability of these items (Hair et al., 2017). In general terms, most items exceed this threshold, suggesting a robust and consistent factor structure. However, certain items with loadings below the critical threshold were identified, suggesting possible deficiencies in their link to the proposed theoretical construct. These include AEE6 (loading: 0.660), AE5 (0.671), and, more critically, NL2 with a loading of only 0.085, representing a significant disconnect from the rest of its dimension. On the other hand, constructs such as entrepreneurial intention (INT), subjective norm (NS), and leadership (LID) exhibit high and homogeneous loadings among their items (all above 0.75), reflecting strong internal consistency and good representation of the underlying concept. In contrast, dimensions such as innovation capacity (INN) and institutional support (AI), although adequate, show greater variability between loadings, which could affect their factor stability.

Communalities, understood as the proportion of the variance of each item explained by the set of common factors, allow us to identify possible problematic elements that could compromise the quality of the model. A value of 0.5 is commonly considered the minimum threshold. In general, the observed communalities are above this threshold, indicating that the factors explain a substantial portion of the variance of most items. However, some relevant exceptions are identified, such as NL2 (0.010), AEE6 (0.436), and AE5 (0.451), which have values below or close to the limit, suggesting weak integration of these items into the model. Likewise, it is observed that the constructs with greater internal consistency, such as NS, INT, and LID, have high average communalities, consistently exceeding the value of 0.7, which reinforces their psychometric stability.

Therefore, the results obtained allow us to affirm that, in general terms, the proposed factorial structure fits the empirical data adequately, supporting the theoretical dimensionality of the instrument. Most constructs show good internal cohesion and clear relationships between items. However, some constructs present critical elements for the construction of more complex models; these weaknesses could compromise the accuracy of the construct, so given the low loading and commonality, items NL2, AEE6, and AE5 are removed from the model. These cases require a thorough review to determine whether or not to consider them in future studies, where they will likely require adjustments or reformulation to improve their performance.

3.4. Reliability and Internal Validity

In order to evaluate the psychometric quality of the constructed instrument, an internal reliability and convergent validity analysis was performed for each of the constructs included in the model. To this end, three indicators widely accepted in the literature were used: Cronbach's alpha coefficient, composite reliability, and average variance extracted (AVE). These indices allow us to estimate the internal consistency between the items of each construct, as well as the proportion of shared variance that is explained by the corresponding latent variable.

The results, presented in

Table 2, indicate that all the constructs evaluated exceed the minimum threshold of 0.70 in reliability coefficients (both alpha and composite reliability), which supports adequate internal consistency among the items that compose them. The highest values are observed in the constructs of perceived behavioral behavior (PBB = 0.910/0.913), entrepreneurial intention (EI = 0.910/0.913), and entrepreneurial attitude (EA = 0.899/0.901), suggesting strong homogeneity among the statements corresponding to these dimensions. In contrast, the constructs with the lowest values, although acceptable, were need for achievement (NL = 0.733/0.739), leadership (LID = 0.777/0.783), and innovation capacity (INN = 0.787/0.795), which could suggest greater conceptual diversity among their items or less semantic clarity in some of them.

With regard to convergent validity, the AVE analysis showed values above the recommended threshold of 0.50 in all constructs. This result indicates that, on average, more than 50% of the variance of the items is explained by the corresponding latent construct, which supports the adequacy of the proposed measurement model. The constructs with the highest AVE were subjective norm (SN = 0.751), entrepreneurial intention (INT = 0.735), and entrepreneurial attitude (EA = 0.713), demonstrating a strong explanatory capacity of their items. On the other hand, some constructs such as innovation capacity (INN = 0.610), opportunity recognition capacity (CRO = 0.615), and leadership (LID = 0.693) had values close to the lower limit, which, while not compromising validity, suggests that they could benefit from future revision to strengthen their internal structure.

3.5. Multicollinearity Analysis

As part of the instrumental validation process, the discriminant validity between the constructs of the instrument and the presence of possible empirical redundancies are evaluated using three complementary criteria: the Fornell-Larcker approach, the heterotrait-monotrait ratio (HTMT) index, and the variance inflation factor (VIF) analysis. These tests allow us to verify whether the constructs are empirically distinguishable, a necessary condition for their future application in structural equation models.

The HTMT analysis, which estimates the ratio between heterotrait and monotrait correlations, yielded results consistent with the above criterion. In general, the values remained below the threshold of 0.9, which supports empirical discrimination between constructs. However, some relationships between constructs were observed with values approaching or exceeding this threshold, which could suggest a high empirical association between certain dimensions. This pattern, although not widespread, occurs especially among conceptually close constructs, such as perceived behavioral behavior, self-efficacy, entrepreneurial intention, locus of control, proactivity, and ability to recognize opportunities. However, it is important to consider that, given that this indicator represents a more demanding criterion than its Fornell-Larcker counterpart, its use should be interpreted with caution, especially in contexts such as the present one, where the objective is to establish the psychometric viability of relatively similar constructs for the identification of entrepreneurial intention. Therefore, it is proposed that the HTMT index be used as a warning sign in cases where there are constructs with high semantic proximity, although always taking care to evaluate causal results in highly complex models.

Table 3 presents the complete HTMT matrix for all constructs evaluated.

In contrast, the Fornell-Larcker criterion showed much more satisfactory behavior in practically all the constructs evaluated. Since, in most cases, the square root of the AVE of each construct exceeds the correlations with other constructs, that is, each dimension shares more variance with its own items than with other factors, which indicates adequate discriminant validity. However, some pairs of constructs continue to show values close to the threshold, suggesting conceptually close relationships that may require special attention or evaluation in their consideration. The detailed Fornell-Larcker discriminant validity results are shown in

Table 4.

In addition, VIF values were calculated for each item in order to detect redundancy among predictor variables. It was found that most items had VIF values below 3.3, indicating low collinearity. However, some specific items, such as CCP5 (VIF = 3.263), CCP6 (VIF = 3.083), AP (VIF = 3.218), and INT3 (VIF = 3.035), showed moderately high levels. This pattern suggests that, although a critical level of multicollinearity is not reached, there is a certain degree of overlap in constructs such as perceived behavioral behavior and entrepreneurial intention, which should be considered in subsequent applications, especially in contexts where causal relationships between multiple predictors and high-order models are modeled. The VIF values for each item are presented in

Table 5.

Overall, the results allow us to affirm that the instrument presents an acceptable level of discrimination between constructs, although close conceptual and empirical relationships are identified between some of them. These relationships do not compromise the validity of the instrument at this stage, but they do imply that, when designing future SEM models, it will be necessary to carefully evaluate the causal hypotheses and the structure of the model. A high correlation between constructs does not invalidate their joint use, but in these cases, it is essential to ensure the conceptual clarity of the constructs involved, since high collinearity can affect the stability of the estimated coefficients and distort the interpretation of the proposed causal relationships.

4. Discussion

The results support that the proposed measurement structure is, in general terms, adequate for the Chilean school level. Most items exhibit factor loadings above the threshold of 0.708, communalities are mostly above 0.50, and reliability indicators (α and CR) exceed 0.70 in all constructs. Likewise, the AVEs reach or exceed 0.50, which supports the convergent validity of the model. These findings are consistent with theoretical (Cortez & Hauck, 2020) and methodological (Hair et al., 2017; Hair et al., 2019; Fornell & Larcker, 1981) recommendations for the design and validation of SEM-oriented instruments.

At the descriptive level, a consistent pattern of high scores in IE, attitude, and subjective norm is observed, along with relatively lower levels of institutional support and entrepreneurial alertness. This contrast can be interpreted in light of the conceptual discussion. While the attitudinal determinants of TCP show internal cohesion, the more contextual or "opportunity detection" components reflect greater heterogeneity in perceptions and dispersions, probably sensitive to the specific educational experience of each high school. This reading is in line with the literature that reports non-uniform effects of EE programs and highlights the relevance of the specific pedagogical context (Souitaris et al., 2007; Do Paço et al., 2015; Brüne & Lutz, 2020).

In the internal validation, three items (NL2, AEE6, and AE5) had loadings and/or communalities below the criteria and were therefore excluded from subsequent analyses. The decision is methodologically consistent and improves the parsimony of the model, reducing potential noise in the estimation of latent variables. However, from a content perspective, it is advisable to review the wording and semantic alignment of these items with their constructs, as low saturation could be due to linguistic ambiguity, conceptual overlap, or differences in the appropriation of terms by students at different levels of secondary education (Do Paço et al., 2015; Marques et al., 2012; Thompson & Kwong, 2016). Such adjustments are common in iterative validation processes and do not compromise the overall usefulness of the instrument.

With regard to discriminant validity, the Fornell-Larcker criterion is amply met; however, the HTMT index shows high correlations between conceptually related constructs (perceived behavioral control, self-efficacy, locus of control, proactivity, opportunity recognition, and EI). This empirical proximity is to be expected given the underlying theoretical structure (determinants of agency and action), but it requires caution when specifying structural models with multiple highly correlated predictors (Bae et al., 2014; Shahin et al., 2021). In this regard, the VIFs at the item level are generally acceptable, although some items have moderately high values, suggesting some overlap that should be considered in future specifications (Henseler et al., 2015; Diamantopoulos & Siguaw, 2006).

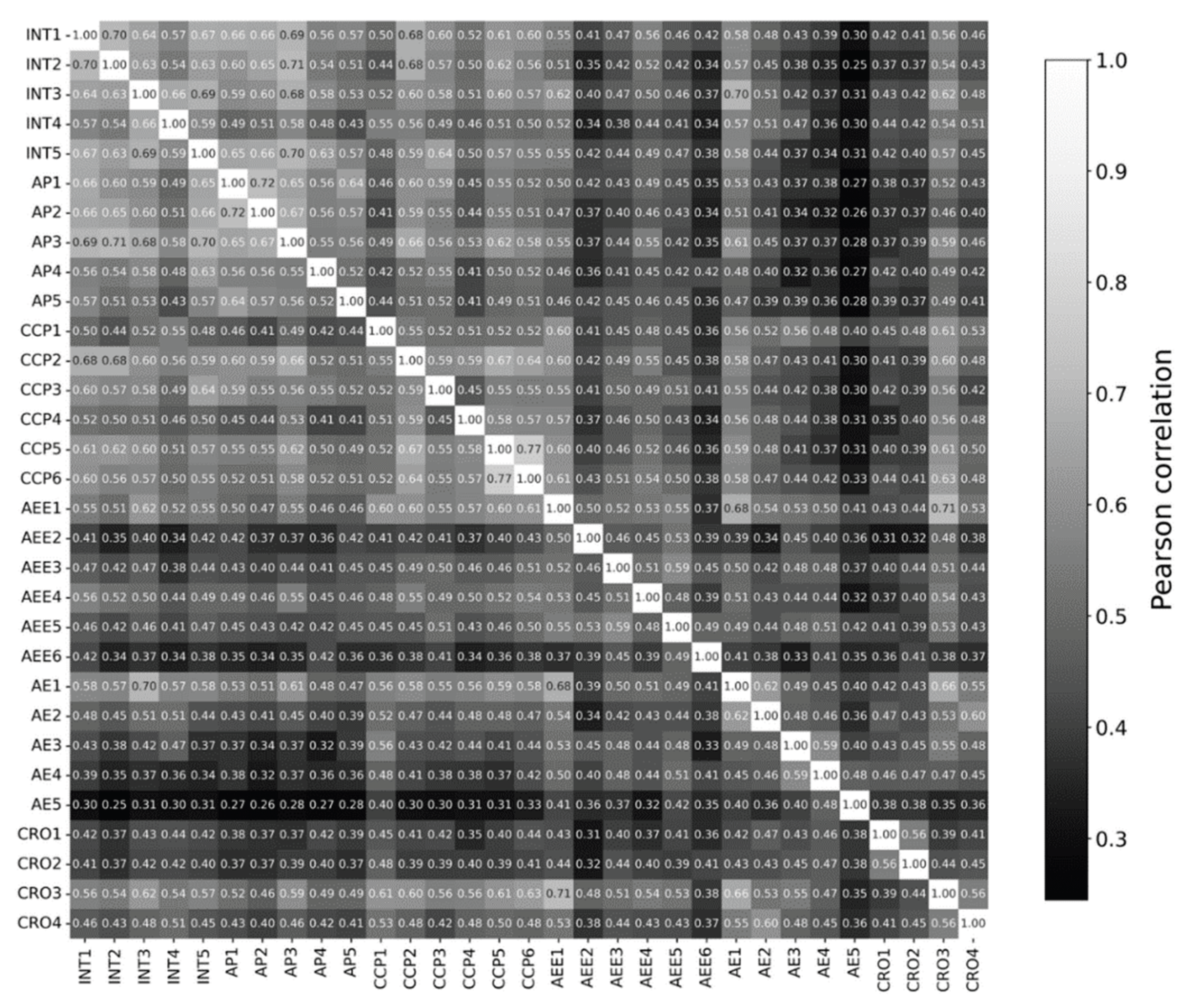

As a practical measure to strengthen the final selection of items in constructs with high multicollinearity, it is appropriate to complement the load/communal criteria with the inspection of the Pearson correlation matrix, prioritizing items that contribute non-redundant variance and maintain conceptual coverage of the domain. This procedure improves empirical discrimination without sacrificing theoretical representativit , and is especially useful when planning second-order models or seeking more parsimonious specifications for operational applications in school contexts.

Finally, the sample size (n=1,402) and the diversity of establishments strengthen the stability of the estimates and generalization in secondary education contexts, aligning with recommendations on validations with large samples (Cortez and Hauck, 2020). However, caution is advised when extrapolating to other types of schools or regions without additional evidence of measurement invariance.

As a complement to the criteria used (loadings, communalities, AVE, HTMT, and VIF), Pearson's correlation matrix (below) was used to identify clusters of indicators with high redundancy and to prioritize items that contribute non-overlapping variance within each construct (

Figure 3). Consistent with HTMT and VIF, the heat map shows dense clusters between CCP, AEE, LC, PRO, CRO, and INT indicators, i.e., the domains linked to self-agency that the literature recognizes as determining nuclei of entrepreneurial intention (Ajzen, 1991; Liñán & Chen, 2009; Moriano et al., 2012). This input supports purification decisions when two or more items present (i) very high Pearson correlations with each other, (ii) relatively high VIFs, and (iii) asymmetric loadings/communalities. In these situations, it is advisable to retain the item with the best overall performance and greatest semantic representativeness and discard its redundant counterpart. This triangulated use of Pearson–VIF–AFC/HTMT reduces noise and favors parsimonious specifications without losing domain coverage.

In substantive terms, high means in INT, AP, and NS, together with comparatively lower values in institutional support (IS) and entrepreneurial alertness (EA), are consistent with the core of the TCP—favorable attitudes and normative pressures, with greater variability in contextual perceptions and opportunity capabilities—and with previous evidence on the heterogeneity of effects in Entrepreneurial Education (EE) at the school level (Do Paço & Palinhas, 2011). This profile suggests that, in the context studied, attitudinal determinants are more consolidated than contextual and "opportunity detection" dimensions, a pattern that the literature associates with specific training experience and support from the school environment (Kolvereid, 1996; Tang et al., 2012; Hu & Ye, 2017).

Finally, the sample size (n = 1,402) and the diversity of establishments provide stability to the estimates and credentials for applications in TP/HC contexts, without prejudice to continuing to strengthen empirical discrimination in agency constructs through the combination of psychometric criteria (AFC/HTMT/VIF) and Pearson correlations with visual support, particularly when seeking models of greater causal complexity. This convergence of instrumental evidence is compatible with current methodological recommendations for validations for SEM purposes.

5. Conclusions

The study presents an instrument based on Ajzen's Theory of Planned Behavior (1991) and integrated with psychological and contextual variables from the reviewed literature, which shows a globally solid psychometric performance in Chilean secondary school students. The proposed measurement structure fits the data adequately, with factor loadings mostly above the threshold of 0.708, communalities mostly above 0.50, and reliability coefficients (Cronbach's alpha and composite reliability) above 0.70 in all constructs. In addition, AVE values reach or exceed 0.50, supporting convergent validity. Taken together, these results enable the use of the instrument in structural equation modeling and in evaluations of entrepreneurial education programs at the school level.

Discriminant validity is broadly supported by the Fornell–Larcker criterion, while the HTMT index reveals high associations between some conceptually close constructs (perceived behavioral control, self-efficacy, locus of control, proactivity, opportunity recognition, and entrepreneurial intention). This pattern does not invalidate the model, but it suggests caution when specifying models with multiple closely related predictors. Similarly, the VIFs at the item level are mostly below 3.3, although some items are in moderate ranges that should be monitored in subsequent applications. Thus, the instrument offers acceptable discrimination between dimensions, while also pointing to areas of empirical proximity consistent with the theoretical basis of the construct.

In operational terms, the elimination of items NL2, AEE6, and AE5—due to their low loadings and/or communalities—improves the parsimony of the model without undermining its overall consistency, and guides semantic adjustment priorities for future iterations. Complementarily, and given the presence of high correlations between some "agency" constructs, it is recommended to use, as a support to the classic criteria of loading and communality, the inspection of Pearson's correlation matrix, to privilege items that contribute non-redundant variance. These methodological decisions, aligned with the criteria reported in the manuscript, strengthen the instrument's ability to differentiate related dimensions without sacrificing conceptual coverage of the domain being evaluated (Souitaris et al., 2007; Oosterbeek et al., 2010).

Although this research was limited by its location in four educational institutions, the sample size contributes to the stability of the estimates and supports the instrument's applicability in secondary education TP/HC contexts. Regarding its applied use, the findings suggest that entrepreneurial education efforts at the school level could especially benefit from interventions that strengthen contextual dimensions (such as perceived institutional support) and capacities linked to opportunity recognition (Brüne & Lutz, 2020), which were the areas with the greatest relative variability compared to the high levels observed in intention, attitude, and subjective norm. These orientations derive directly from the descriptive patterns and internal validity evidence presented and pose the challenge of developing research that conducts multicenter replications and subgroup invariance tests, item refinement prioritizing non-redundant variance, and confirmatory models that test mediations between TPB and complementary variables, favoring second-order or more parsimonious models when empirical evidence warrants it.

Author Contributions

Removed for peer review.

Funding

This research was funded by Removed for peer review.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of the Removed for peer review.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent was obtained from the participants' legal guardians for participation in this study.

Data Availability Statement

Dataset available on request from the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| EI |

Entrepreneurial Intention |

| TPB |

Theory of Planned Behavior |

| GEM |

Global Entrepreneurship Monitor |

| EE |

Entrepreneurship Education |

| TCP |

Teoría del Comportamiento Planificado |

| KMO |

Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin |

| AVE |

Average Variance Extracted |

| HTMT |

Heterotrait-Monotrait ratio |

| VIF |

Variance Inflation Factor |

| SEM |

Structural Equation Modeling |

| CFA |

Confirmatory Factor Analysis |

| CR |

Composite Reliability |

| INT |

Entrepreneurial Intention |

| AP |

Entrepreneurial Attitude (Actitud Emprendedora) |

| NS |

Subjective Norm (Norma Subjetiva) |

| CCP |

Perceived Behavioral Control (Control Conductual Percibido) |

| AEE |

Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy (Autoeficacia Emprendedora) |

| AI |

Institutional Support (Apoyo Institucional) |

| AE |

Entrepreneurial Alertness (Alerta Emprendedora) |

| INN |

Innovation Capacity |

| NL |

Need for Achievement (Necesidad de Logro) |

| LC |

Internal Locus of Control (Locus de Control Interno) |

| PR |

Risk Propensity (Propensión al Riesgo) |

| CRO |

Ability to Recognize Opportunities (Capacidad de Reconocer Oportunidades) |

| PRO |

Proactivity (Proactividad) |

| LID |

Leadership (Liderazgo) |

| OP |

Optimism |

| VS |

Social Value (Valor Social) |

| S.D. |

Standard Deviation (Desviación Estándar) |

| PBB |

Perceived Behavioral Behavior (variante de CCP) |

| EA |

Entrepreneurial Alertness (variante de AE) |

| ESE |

Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy (variante de AEE) |

| NA |

Need for Achievement |

| SN |

Subjective Norm |

| IS |

Institutional Support |

| AFC |

Análisis Factorial Confirmatorio (equivalente español de CFA) |

| TP/HC |

Técnico-Profesional/Humanista-Científico |

References

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior & Human Decision Processes 1991, 50(2), 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcaraz, J.; García, F. M. Self-employment and the promotion of entrepreneurship: Myths and realities; Bomarzo: Madrid, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Aragón-Sánchez, A.; Baixauli-Soler, S.; Carrasco-Hernández, A. J. A missing link: The behavioral mediators between resources and entrepreneurial intentions. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research 2017, 23(5), 752–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athayde, R. Measuring enterprise potential in young people. Entrepreneurship Theory & Practice 2009, 33(2), 481–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athayde, R.; Hart, M. Developing a methodology to evaluate enterprise education programs. International Review of Entrepreneurship 2012, 10(3), 91–114. [Google Scholar]

- Atienza-Sahuquillo, C.; Barba-Sánchez, V.; Matlay, H. The development of entrepreneurship at school: The Spanish experience. Education + Training 2016, 58(7/8), 783–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, T. J.; Qian, S.; Miao, C.; Fiet, J. O. The relationship between entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurial intentions: A meta-analytic review. Entrepreneurship Theory & Practice 2014, 38(2), 217–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, M. S. Tests of significance in factor analysis. British Journal of Statistical Psychology 3 1950, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bateman, T. S.; Crant, J. M. The proactive component of organizational behavior. Journal of Organizational Behavior 1993, 14(2), 103–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briseño-Aguirre, N. de la L.; Saavedra-García, M. L.; Velázquez-Rojas, K. G. The entrepreneurial ecosystem and entrepreneurial intention in university students. Administrative Sciences Theory and Praxis 2024, 20(2), 11–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brüne, N.; Lutz, E. The effect of entrepreneurship education in schools on entrepreneurial outcomes: A systematic review. Management Review Quarterly 70 2020, 275–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, B. M. Structural equation modeling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming, 2nd ed.; Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, N.; Brush, C.; Greene, P.; Gatewood, E.; Hart, M. Women entrepreneurs who break through to equity financing: The influence of human, social and financial capital; An International Journal of Entrepreneurial Finance: Venture Capital, 2003; Volume 5, 1, pp. 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cera, G.; Mlouk, A.; Cera, E.; Shumeli, A. The Impact of Entrepreneurship Education onEntrepreneurial Intention. A Quasi-Experimental Research Design. Journal of Competitiveness 2020, 12(1), 39–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C. C.; Greene, P. G.; Crick, A. Does entrepreneurial self-efficacy distinguish entrepreneurs from managers? Journal of business venturing 1998, 13(4), 295–316. [Google Scholar]

- Cortez, P. A.; Hauck Filho, N. Literature review of entrepreneurial intention assessment tools. Latin American Journal of Management 2020, 16(30), 80–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, A. R.; Franklin, J. A.; Andrews, G. A scale to measure locus of control of behavior. British Journal of Medical Psychology 1984, 57(2), 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diamantopoulos, A.; Siguaw, J. A. Formative versus reflective indicators in organizational measure development: A comparison and empirical illustration. British Journal of Management 17 2006, 263–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diario Financiero. The intention to start a business falls to its lowest level since 2010 and companies are less innovative. 2025. Available online: https://negocios.udd.cl/files/2025/07/whatsapp-image-2025-07-31-at-11-20-00.jpeg.

- Do Paço, A.; Palinhas, M. Teaching entrepreneurship to children: A case study. Journal of Vocational Education & Training 2011, 63(4), 593–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do Paço, A.; Ferreira, J.; Raposo, M.; Rodrigues, R.; Dinis, A. Entrepreneurial intentions: Is education enough? International Entrepreneurship & Management Journal 2015, 11(1), 57–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duong, C. D.; Le, T. L.; Ha, N. T. The Role of Trait Competitiveness and EntrepreneurialAlertness in the Cognitive Process of Entrepreneurship Among Students: A Cross-Cultural Comparative Study Between Vietnam and Poland. Journal of Competitiveness 2021, 13(4), 25–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elert, N.; Andersson, F. W.; Wennberg, K. The impact of entrepreneurship education in secondary school on long-term entrepreneurial performance. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 111 2015, 209–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. (n.d.). Entrepreneurship education. Directorate-General for Internal Market, Industry, Entrepreneurship and SMEs. Available online: https://education.ec.europa.eu/es/focus-topics/improving-quality-equity/key-competences-lifelong-learning/entrepreneurship.

- Fayolle, A.; Gailly, B.; Lassas-Clerc, N. Assessing the impact of entrepreneurship education programs: A new methodology. Journal of European Industrial Training 2006, 30(9), 701–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Pérez, V.; Montes-Merino, A.; Rodríguez-Ariza, L.; Galicia, P. E. A. Emotional competencies and cognitive antecedents in shaping students’ entrepreneurial intention: The moderating role of entrepreneurship education. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal 2019, 15(1), 281–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, J. J.; Raposo, M. L.; Gouveia-Rodrigues, R.; Dinis, A.; Do Paço, A. A model of entrepreneurial intention: An application of the psychological and behavioral approaches. Journal of Small Business & Enterprise Development 2012, 19(3), 424–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D. F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research 1981, 18(1), 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Yan, T.; Tian, Y.; Niu, X.; Xu, X.; Wei, Y.; Wu, X. Exploring factors influencing students’ entrepreneurial intention in vocational colleges based on structural equation modeling: Evidence from China. Frontiers in Psychology 13 2022, 898319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furdui, A.; Lupu-Dima, L.; Edelhauser, E. Implications of entrepreneurial intentions of Romanian secondary education students, over the Romanian business market development. Processes 2021, 9(4), 665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrido-Yserte, R.; Crecente-Romero, F.; Gallo-Rivera, M. T. The relationship between capacities and entrepreneurial intention in secondary school students. Economic Research–Ekonomska Istraživanja 2020, 33(1), 2322–2341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geldhof, G. J.; Porter, T.; Weiner, M. B.; Malin, H.; Bronk, K. C.; Agans, J. P.; et al. Fostering youth entrepreneurship: Preliminary findings from the Young Entrepreneurs Study. Journal of Research on Adolescence 2014, 24(3), 431–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F.; Babin, B. J.; Anderson, R. E.; Black, W. C. Multivariate data analysis, 8th ed.; Pearson, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J. F.; Hult, G. T. M.; Ringle, C. M.; Sarstedt, M. A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM), 2nd ed.; Sage Publications, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallam, C.; Zanella, G.; Dorantes Dosamantes, C. A.; Cardenas, C. Measuring entrepreneurial intent? Temporal construal theory shows it depends on your timing. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research 2016, 22(5), 671–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C. M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 43 2015, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández Muñoz, V.; Monzón Campos, J.L.; Torres Ortega, J. Traditional, social, and sustainable student entrepreneurship in the university context—a systematic review. REVESCO. Journal of Cooperative Studies, online advance 2025, 1–26, e104784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, R.; Ye, Y. Do entrepreneurial alertness and self-efficacy predict Chinese sports major students' entrepreneurial intention? Social Behavior and Personality: an international journal 2017, 45(7), 1187–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, L. R.; Sloof, R.; Van Praag, M. The effect of early entrepreneurship education: Evidence from a field experiment. European Economic Review 72 2014, 76–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, H. F. An index of factorial simplicity. Psychometrika 1974, 39(1), 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, S.; Biemans, H. J. A.; Lans, T.; Chizari, M.; Mulder, M. The impact of entrepreneurship education: A study of Iranian students’ entrepreneurial intentions and opportunity identification. Journal of Small Business Management 2016, 54(1), 187–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.; Kim, D.; Lee, W. J.; Joung, S. The effect of youth entrepreneurship education programs: Two large-scale experimental studies. SAGE Open 2020, 10(3), 215824402095697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolvereid, L. Organizational employment versus self-employment: Reasons for career choice intentions. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 1996, 20(3), 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, N. F., Jr. The cognitive psychology of entrepreneurship. In Handbook of entrepreneurship research: An interdisciplinary survey and introduction; Springer US, 2003; pp. 105–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, N. F. The impact of prior entrepreneurial exposure on perceptions and new venture feasibility and desirability. Entrepreneurship Theory & Practice 1993, 18(1), 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacobucci, D.; Micozzi, A. Entrepreneurship education in Italian universities: Trend, situation and opportunities. Education & Training 2012, 54(8), 673–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepoutre, J.; Van den Berghe, W.; Tilleuil, O.; Crijns, H. A new approach to testing the effects of entrepreneurship education among secondary school pupils; Vlerick Leuven Gent Working Paper Series 2010/01; Autonomous Management School, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liñán, F. Skill and value perceptions: How do they affect entrepreneurial intentions? International Entrepreneurship & Management Journal 2008, 4(3), 257–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liñán, F.; Chen, Y. Development and cross-cultural application of a specific instrument to measure entrepreneurial intentions. Entrepreneurship Theory & Practice 2009, 33(3), 593–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liñán, F.; Fayolle, A. A systematic literature review on entrepreneurial intentions: Citation, thematic analyses, and research agenda. International Entrepreneurship & Management Journal 2015, 11(4), 907–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López Puga, J. Modelos actitudinales y emprendimiento sostenible. Cuaderno Interdisciplinar de Desarrollo Sostenible 2012, (8), 111–131. [Google Scholar]

- Marques, C.; Ferreira, J.; Gomes, D.; Gouveia, R. Entrepreneurship education: How psychological, demographic and behavioral factors predict entrepreneurial intention. Education + Training 2012, 54(8/9), 657–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Gregorio, S.; Oliver, A. Measuring entrepreneurship intention in secondary education: validation of the Entrepreneurial Intention Questionnaire. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment 2022, 40(4), 499–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monreal Garrido, M. Cooperative entrepreneurship and entrepreneurship theories. Analysis of cooperatives created in the Valencian Community between 2008 and 2014. 2014. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10550/50032.

- Moriano, J. A.; Gorgievski, M.; Laguna, M.; Stephan, U.; Zarafshani, K. A cross-cultural approach to understanding entrepreneurial intention. Journal of Career Development 2012, 39(2), 162–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabi, G.; Walmsley, A.; Liñán, F.; Akhtar, I.; Neame, C. Does entrepreneurship education in the first year of higher education develop entrepreneurial intentions? The role of learning and inspiration. Studies in Higher Education 2018, 43(3), 452–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowiński, W.; Haddoud, M. Y. The role of inspiring role models in enhancing entrepreneurial intention. Journal of Business Research 96 2019, 183–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J. C.; Bernstein, I. H. Psychometric theory, 3rd ed.; McGraw-Hill, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Obschonka, M.; Hakkarainen, K.; Lonka, K.; Salmela-Aro, K. Entrepreneurship as a twenty-first century skill: Entrepreneurial alertness and intention in the transition to adulthood. Small Business Economics 48 2017, 487–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oosterbeek, H.; Van Praag, M.; Ijsselstein, A. The impact of entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurship skills and motivation. European Economic Review 2010, 54(3), 442–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orellana, W.; Martínez de Lejarza, J. Theories of entrepreneurship and worker cooperatives: Theoretical foundations and empirical evidence in the creation of worker cooperatives. CIRIEC-Spain, Journal of Public, Social, and Cooperative Economy 78 2013, 11–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortuño-Sierra, J.; Gargallo-Ibort, E.; Ciarreta-López, A.; Dalmau-Torres, J. M. Measuring entrepreneurship in adolescents at school: New psychometric evidence on the BEPE-A. PLOS ONE 2021, 16(4), e0250237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otache, I.; Umar, K.; Audu, Y.; Onalo, U. The effects of entrepreneurship education on students’ entrepreneurial intentions: A longitudinal approach. Education+ Training 2021, 63(7/8), 967–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedrosa, I. Evaluation of entrepreneurial personality using a computerized adaptive test

. Doctoral thesis, University of Oviedo, 2015. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/tesis?codigo=101470&orden=1&info=link.

- Peterman, N. E.; Kennedy, J. Enterprise education influencing students’ perceptions of entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship Theory & Practice 2003, 28(2), 129–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pihie, Z. A. L.; Bagheri, A. Entrepreneurial attitude and entrepreneurial efficacy of technical secondary school students. Journal of Vocational Education and Training 2010, 62(3), 351–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porfeli, E. J.; Lee, B.; Vondracek, F. W. Identity development and careers in adolescents and emerging adults: Content, process, and structure. In Handbook of vocational psychology; Routledge, 2013; pp. 133–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purwana, D.; Suhud, U.; Rahayu, S. Entrepreneurial intention of secondary and tertiary students: Are they different? International Journal of Economic Research 2017, 14(18), 69–81. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/326836470_Entrepreneurial_Intention_of_Secondary_and_Tertiary_Students_are_They_Different.

- Rauch, A.; Frese, M. Let’s put the person back into entrepreneurship research: A meta-analysis on the relationship between business owners’ personality traits, business creation, and success. European Journal of Work & Organizational Psychology 2007, 16(4), 353–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio Hernández, F. J.; Lisbona Bañuelos, A. M. Entrepreneurial intention in university students: Systematic review of scientific production. Universitas Psychologica 21 2022, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sambo, P. M. Investigating the attitude towards entrepreneurship among business studies learners in selected secondary schools

. Master’s mini-dissertation, North-West University, 2018. Available online: https://repository.nwu.ac.za/handle/10394/31051.

- Sánchez, J. C. University training for entrepreneurial competencies: Its impact on intention of venture creation. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal 2011, 7(2), 239–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, J. C. The impact of an entrepreneurship education program on entrepreneurial competencies and intention. Journal of Small Business Management 2013, 51(3), 447–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheier, M. F.; Carver, C. S. The self-consciousness scale: A revised version for use with general populations. Journal of Applied Social Psychology 1985, 15(8), 687–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahin, M.; Ilic, O.; Gonsalvez, C.; Whittle, J. The impact of a STEM-based entrepreneurship program on the entrepreneurial intention of secondary school female students. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal 17 2021, 1867–1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souitaris, V.; Zerbinati, S.; Al-Laham, A. Do entrepreneurship programs raise entrepreneurial intention of science and engineering students? The effect of learning, inspiration, and resources. Journal of Business Venturing 2007, 22(4), 566–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Kacmar, K. M. M.; Busenitz, L. Entrepreneurial alertness in the pursuit of new opportunities. Journal of business venturing 2012, 27(1), 77–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarapuez, E.; García, M. D.; Castellano, N. Socioeconomic aspects and entrepreneurial intention in university students in Quindío (Colombia). Innovar 2018, 28(67), 123–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, P.; Kwong, C. Compulsory school-based enterprise education as a gateway to an entrepreneurial career. International Small Business Journal 2016, 34(6), 838–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres Ortega, J. A.; Monzón Campos, J. L. Future entrepreneurial intentions among Chilean and Basque secondary school students. CIRIEC-Spain, Journal of Public, Social and Cooperative Economy 103 2021, 279–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Ortega, J.; Loyola-Campos, J.; Ibarra-Pérez, D.; Hernández-Muñoz, V. Factors influencing entrepreneurial intentions among Chilean secondary vocational students. Academia Revista Latinoamericana de Administración 2024, 37(2), 265–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, J. Construction and validation of entrepreneurial personality and entrepreneurial ecosystem scales in a sample of secondary school students in Chile. Revista Espacios 2020, 41(30), 189–202. Available online: https://www.revistaespacios.com/a20v41n30/a20v41n30p16.pdf.

- Urban, B.; Kujinga, L. The institutional environment and social entrepreneurship intentions. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research 2017, 23(4), 638–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volery, T.; Müller, S.; Oser, F.; Naepflin, C.; Del Rey, N. The impact of entrepreneurship education on human capital at upper-secondary level. Journal of Small Business Management 2013, 51(3), 429–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westhead, P.; Solesvik, M.Z. Entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurial intention: Do female students benefit? International Small Business Journal 2016, 34(8), 979–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zdolsek Draksler, T.; Sirec, K. The Study of Entrepreneurial Intentions and Entrepreneurial Competencies of Business vs. Non-Business Students. Journal of Competitiveness 2021, 13(2), 171–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Zhou, B.; Tian, X. Political connections and green innovation: The role of a corporate entrepreneurship strategy in state-owned enterprises. Journal of Business Research 2022, 146, 375–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).