Submitted:

09 December 2025

Posted:

11 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Quantitative Assessment Models for Energy Ecosystems

2.2. Hydrogen System Dynamics in Northeast Asia

2.3. System Coupling and State Estimation

3. Methodology

3.1. DCCI Framework Modeling

- Technology Synergy (TS): Represents the efficiency of knowledge transfer and technical interoperability within the ecosystem.

- Regulatory Alignment (RA): (Formerly Policy Coupling) Measures the synchronization of technical standards, safety protocols, and subsidy mechanisms to reduce system impedance.

- Supply Chain Resilience (SCR): Quantifies the robustness of material flows, redundancy, and emergency response capabilities.

3.2. Data Engineering and Preprocessing Pipeline

- Patent Data Mining: Intellectual property data were extracted quarterly via Python scripts (crawler/patent_spider.py) from WIPO PATENTSCOPE [43], utilizing specific keywords and country codes (CN/KR). API rate limits (429) were managed through an exponential backoff algorithm to ensure data completeness.

- Unstructured Text Vectorization: Regulatory documents were batch-downloaded from official government portals, including China's State Council [44] and Korea's MOTIE [45]. Scanned PDF documents underwent optical character recognition (OCR) processing using pytesseract. To mitigate linguistic bias (e.g., Korean honorifics), we applied a human-in-the-loop validation protocol, manually correcting 42 documents to reduce the error rate to 2-3% [46]. Subsequently, the Sentence-BERT model was employed to generate high-dimensional vectors for text documents. The cosine similarity between vector pairs () was calculated to quantify Regulatory Alignment:

- Trade Flow Analysis: Material flux data were extracted monthly from UN Comtrade [47] and the IEA Hydrogen Equipment Trade Database [48] for relevant HS codes: 280440 (hydrogen), 731100 (storage vessels), and 850164 (fuel cells).

- Exogenous Signal Detection: The Geopolitical Risk Index (GRI), sourced from the V-Dem Institute [49], served as the external perturbation signal input, with annual values ranging from 0.42 to 0.58 during the observation period.

3.3. Mathematical Modeling of System Dimensions

3.4. Adaptive Weighting Algorithm

- Perturbation Signal (GRI > 0.5): When the external risk signal exceeds the critical threshold (0.5, derived from V-Dem methodology [49, 56]), the system automatically prioritizes stability. The algorithm increases the Supply Chain gain () by 0.05 to reflect the structural shift towards resilience.

- Performance Feedback Signal: If the Technology subsystem shows positive gradients () for two consecutive periods (matching the 2-year R&D cycle [57]), the algorithm increases the Technology gain () by 0.02 to model the momentum effect.

3.5. Comparative Analysis of Modeling Architectures

- Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis (AHP/TOPSIS): While widely used for static assessments, AHP relies heavily on pairwise comparisons, introducing heuristic bias that is difficult to calibrate dynamically against high-frequency external signals like GRI.

- Principal Component Analysis (PCA): PCA offers an objective, data-driven weight derivation. However, the resulting principal components represent linear combinations of heterogeneous variables (e.g., combining Patent Velocity with Transport Safety), which compromises the physical interpretability of the system's state variables.

- Dynamic Bayesian Networks (DBN): DBNs are capable of modeling complex feedback loops but require extensive transition probability data. Given the limited time-series density of the current hydrogen ecosystem dataset (2020–2024), a DBN approach would suffer from overfitting.

4. Results

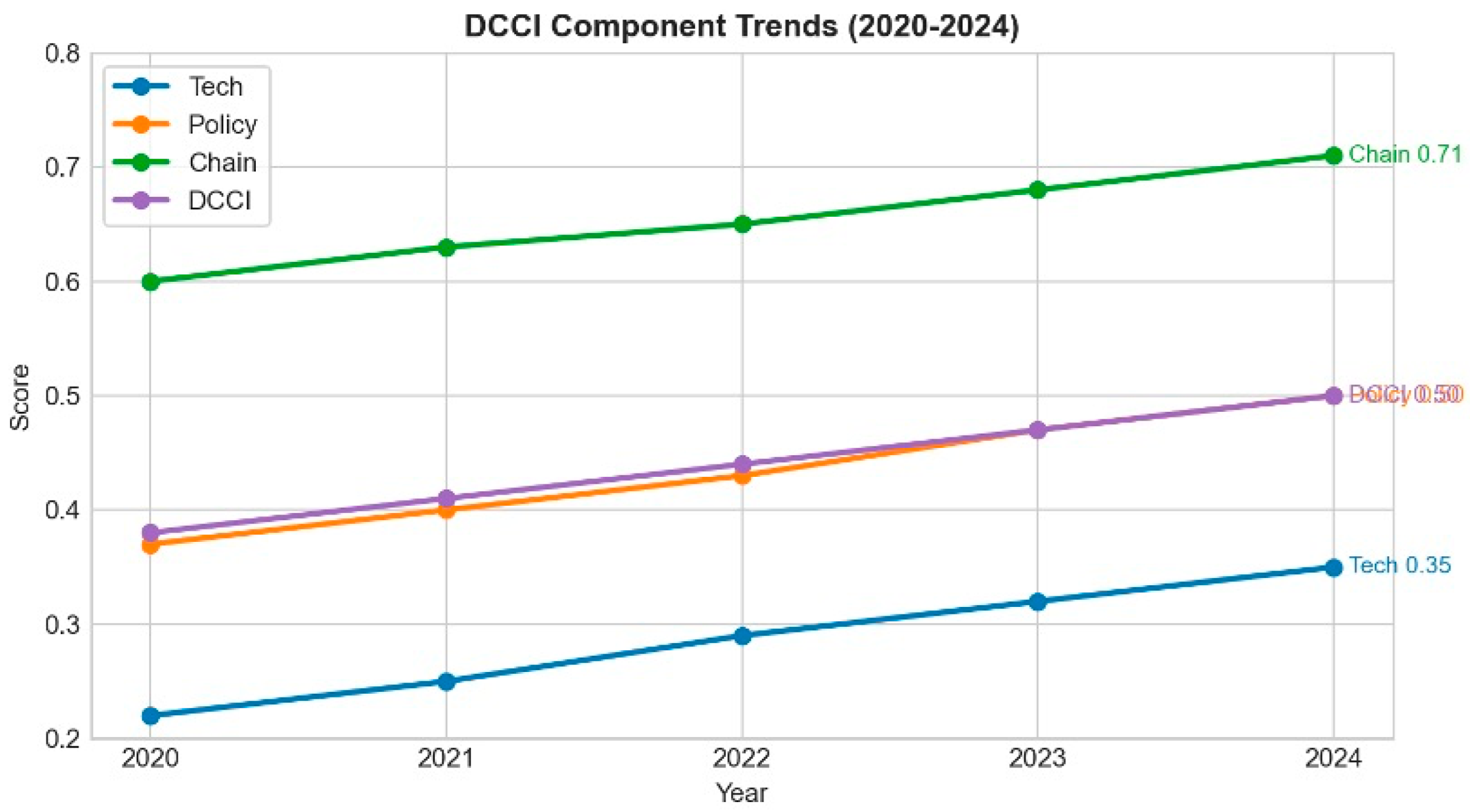

4.1. System State Analysis

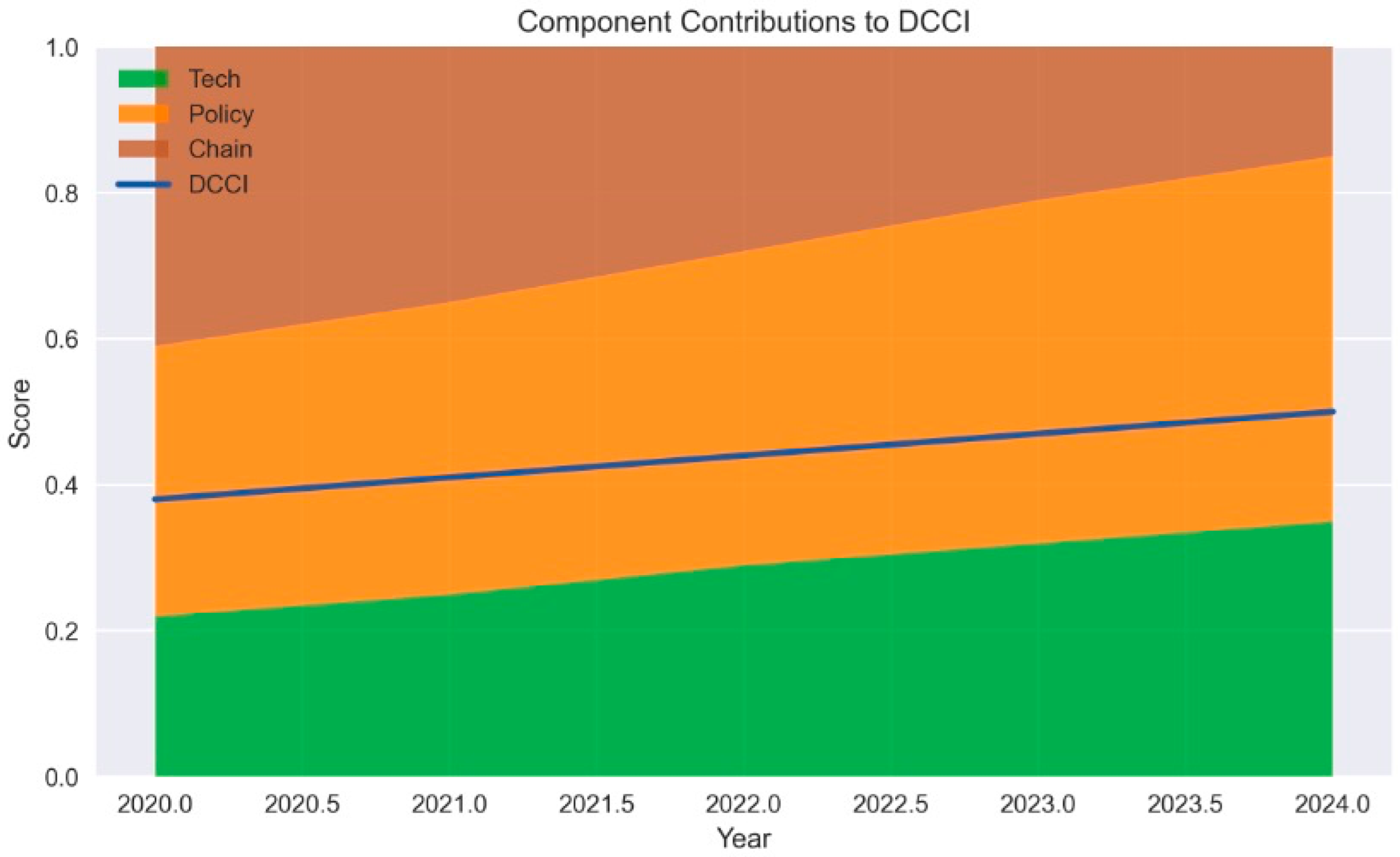

- Supply Chain Resilience (SCR): This subsystem acts as the primary stabilizer, with its state score surging to 0.71 in 2024. This performance is highly correlated (, ) with external benchmarks such as the IEA's East Asia Logistics Resilience Index [58]. The contribution analysis (Figure 3) confirms that SCR accounted for 43% of the total system synergy in 2024, driven by the expansion of cross-border material flux and redundant storage capacities.

- Technology Synergy (TS): Conversely, the Technology subsystem functions as a limiting factor, lagging significantly with a score of 0.35. The trajectory shows a dampening effect, where initial gains in 2021 were offset by the stagnation in standard alignment protocols [59].

- Regulatory Alignment (RA): This subsystem demonstrates a converging trend (Score 0.50), reflecting a gradual synchronization of policy vectors exceeding the IEA global policy maturity benchmark of 0.45 [48], though residual divergence in subsidy mechanisms persists.

4.2. Subsystem Performance Heatmap

- High-Gain Indicators (Drivers): The Transport Reliability metric recorded a near-optimal score of 0.95 in 2024. However, interpretation requires distinguishing between input and outcome variables: this score is heavily weighted by a 58% year-on-year increase in safety drill frequency () rather than solely by zero-incident rates () [60]. Similarly, Node Diversity improved consistently (0.74), validating the system's robustness against single-point failures in the supply network.

- High-Impedance Indicators (Constraints): The Standard Synchronization metric remains critically low (0.05), identifying the lack of mutual recognition for 17 key hydrogen fueling protocols as a primary blockage [59]. Furthermore, Patent Sharing Rate (0.32) exhibits a slow time-constant, indicating high friction in intellectual property transfer. Operational inefficiencies are also evident in human capital flows, where visa processing latencies have resulted in a talent arrival rate of less than 60% for joint projects [61, 62]. The Regulatory Vector Similarity (0.55) has improved but remains constrained by the misalignment of R&D subsidy calculations (Indicator 7).

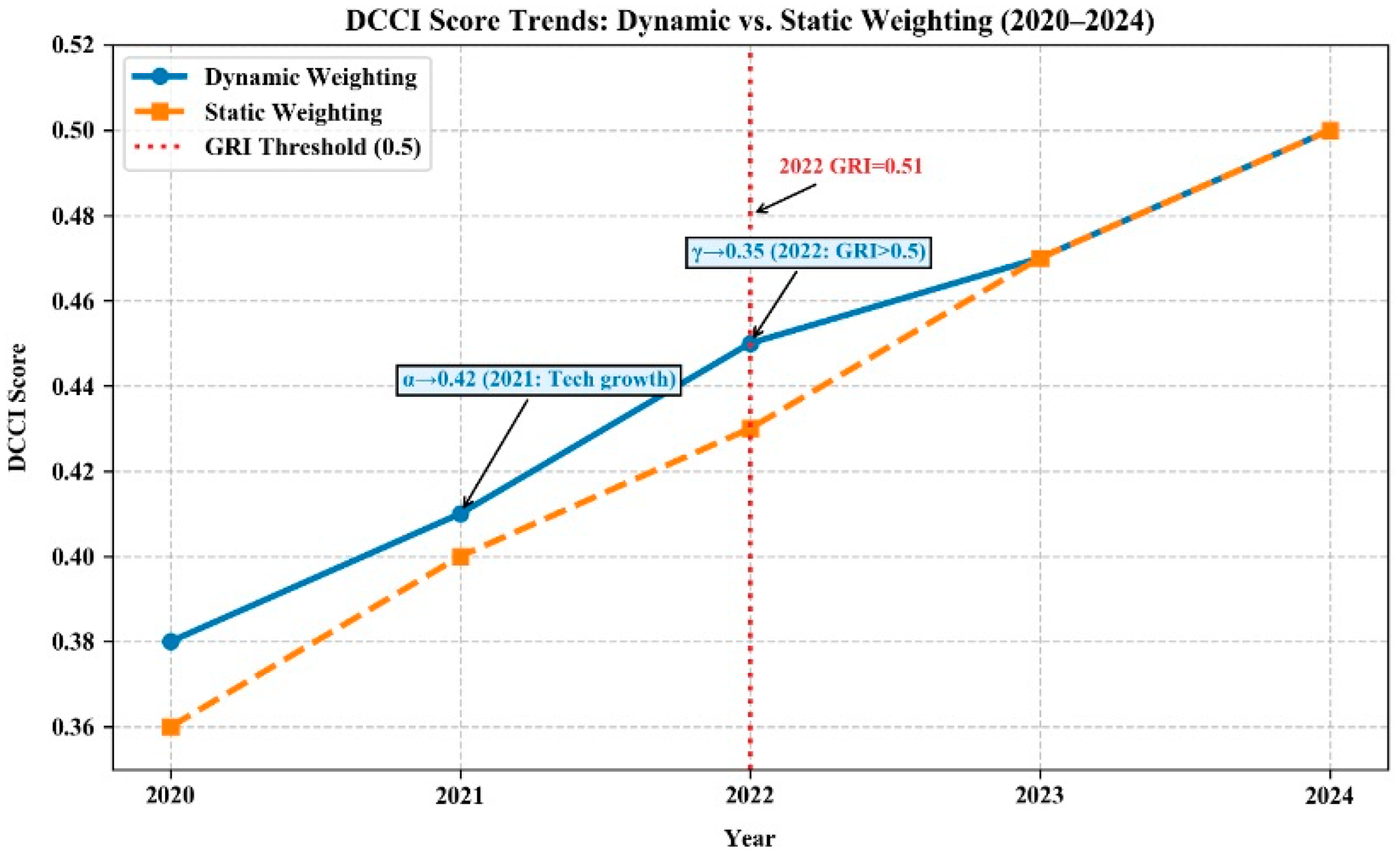

4.3. Algorithm Validation and Sensitivity Analysis

- Response to Risk Signal (2022): When the Geopolitical Risk Index (GRI) breached the critical threshold of 0.5 (GRI=0.51), the dynamic algorithm automatically triggered the Gain Scheduling mechanism, increasing the Supply Chain weight () by 0.05. This adjustment resulted in a corrected state estimate of 0.45 (vs. 0.43 in the static model), accurately reflecting the system's strategic shift towards resilience buffering.

- Response to Performance Feedback (2021): In response to consecutive positive gradients in technology output (), the algorithm amplified the Technology gain () to 0.42, capturing the momentum of early-stage pilot projects.

- Robustness: Bootstrapping analysis (1,000 resamples) and sensitivity tests on the threshold parameter () showed that the output deviation remained within , confirming algorithmic stability.

5. Discussion

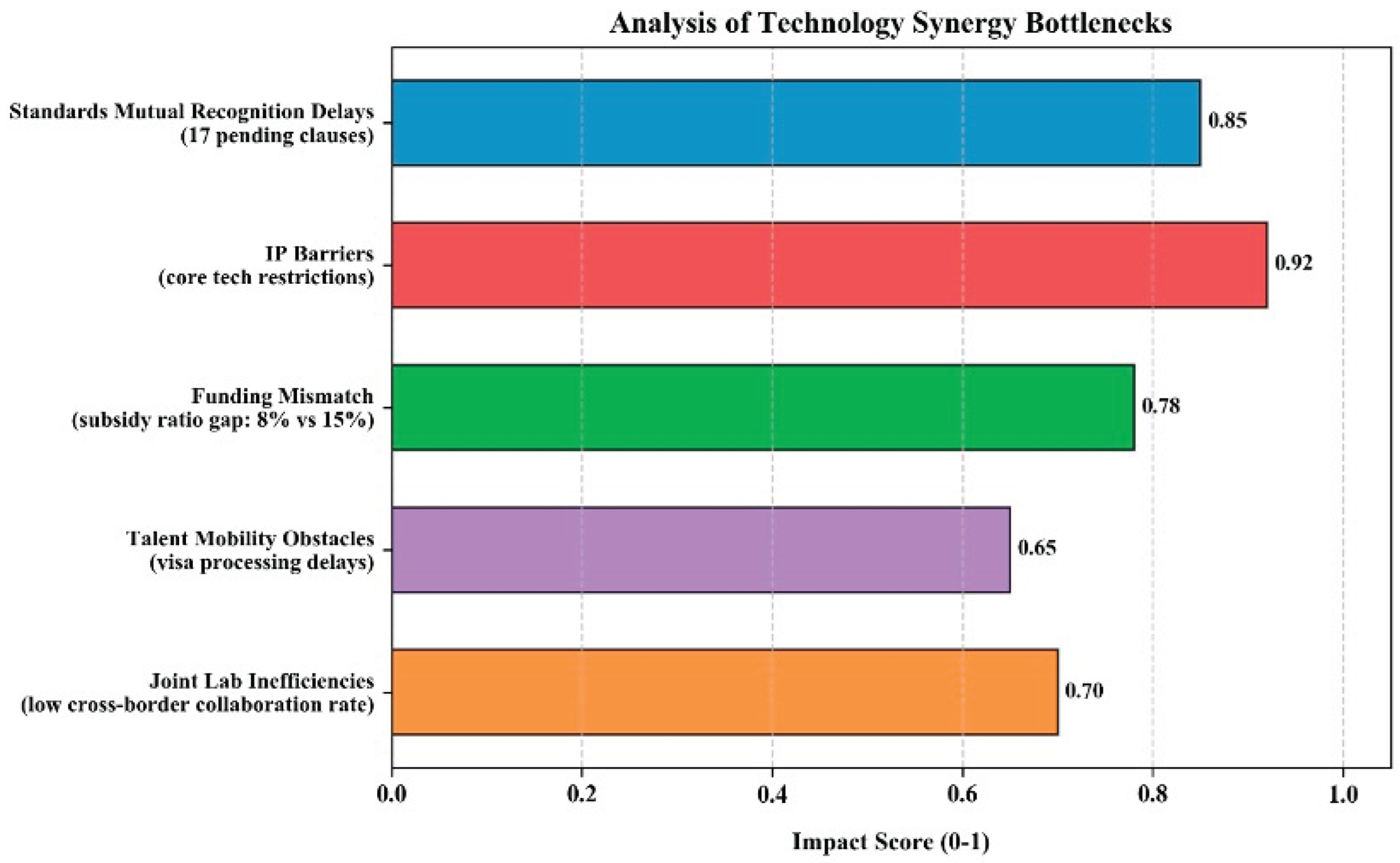

5.1. Technical Constraints Identification

- Intellectual Property (IP) Data Security (Impact Score 0.92): The lack of secure, standardized data exchange protocols constitutes the most severe constraint. Industrial stakeholders, particularly in the fuel cell sector, exhibit reluctance to share core proprietary data (e.g., MEA coating specifications) due to the absence of a trusted third-party custody mechanism. This has resulted in a high friction coefficient for technology transfer, limiting cross-border licensing efficiency.

- Protocol Latency (Impact Score 0.85): Technical interoperability is severely hampered by the lack of mutual recognition for 17 key technical standards, specifically regarding hydrogen refueling protocols and high-pressure storage vessel testing. This regulatory misalignment creates significant interface mismatches, necessitating redundant certification processes that delay project deployment by an average of 6–12 months.

- Funding Vector Mismatch (Impact Score 0.78): A divergence in R&D subsidy mechanisms reduces the viability of joint projects. The asymmetry between tax-credit-based incentives in one jurisdiction and direct-subsidy models in the other creates a "funding gap" for bilateral pilot programs, discouraging collaborative investment in high-risk, early-stage technologies.

- Operational Inefficiency in Joint Laboratories (Impact Score 0.70): despite the establishment of bilateral research platforms, their operational output remains suboptimal. Data indicates that only 40% of established joint labs achieve their annual collaboration targets, primarily due to administrative redundancies and the lack of unified project management protocols.

- Human Capital Mobility Constraints (Impact Score 0.65): The physical flow of technical expertise is constrained by procedural latencies. Visa processing delays (averaging 3–4 months) have resulted in a talent arrival rate of less than 60% for scheduled joint research initiatives [55, 56], directly impacting the continuity of long-term R&D projects.

5.2. System Optimization Strategies and Technical Roadmap

5.3. Limitations and Future Work

- Proxy Variable Latency and Noise: The reliance on proxy indicators for system resilience (e.g., safety drill frequency as a proxy for transport reliability) introduces a signal-to-noise ratio challenge. Although we applied normalization techniques, these input-based metrics may not fully capture outcome-based risks, potentially leading to an overestimation of system stability during low-frequency, high-impact events (black swan events). Future iterations will integrate real-time IoT sensor data from logistics nodes to replace static proxies with dynamic telemetry.

- NLP Vectorization Bias: The Sentence-BERT model utilized for regulatory alignment analysis, while robust, may contain residual linguistic bias (estimated at 2–3% variance) when processing context-specific legal terminology in Chinese and Korean. This semantic drift could affect the precision of the Regulatory Vector Similarity score. We propose fine-tuning a domain-specific Large Language Model (LLM) on a bilingual corpus of energy law to minimize this vectorization error.

- Heuristic Initialization Constraints: The initial weight parameters () were derived from historical project distributions and expert heuristics. While the adaptive algorithm adjusts these weights dynamically, the starting state remains dependent on prior knowledge. Future research will employ Reinforcement Learning (RL) agents to autonomously optimize these initial parameters by simulating multi-year cooperation scenarios, thereby moving towards a fully unsupervised state estimation model.

- System Boundary Limitations: The current model focuses on bilateral interactions, treating global market variables (e.g., global hydrogen price fluctuations, third-party competition from Australia or the Middle East) as constant boundary conditions. Expanding the model to a multi-node network topology would allow for the assessment of how third-party perturbations propagate through the bilateral link.

6. Conclusions

- System Trajectory and Asymmetry: The China-Korea hydrogen ecosystem exhibits a recovery trajectory, with the composite synergy score rising from 0.38 (2020) to 0.50 (2024) at a CAGR of 7.1%. However, a critical structural asymmetry persists: the system is stabilized by robust Supply Chain Resilience (Contribution: 43%) but severely damped by high impedance in Technology Synergy (Score: 0.35), specifically due to protocol mismatches in fuel cell standards and IP data security.

- Algorithmic Superiority: Comparative validation demonstrates that the dynamic weighting mechanism significantly reduces state estimation error. During the high-volatility period of 2022 (GRI > 0.5), the dynamic model correctly identified a state inflection point (Score 0.45), whereas the static model failed to account for the resilience buffering effect (Score 0.43). Sensitivity analysis confirms the algorithm's stability, with output deviations remaining within under parameter perturbation.

- Engineering Implications: To optimize system synergy, we propose a technical roadmap focusing on protocol synchronization and digital trust architectures. Immediate priority should be given to establishing a secure, third-party-verified IP custody platform to lower the activation energy for technology transfer, alongside a dynamic inventory buffering mechanism to mitigate supply chain risks.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Full Data Repository

References

- Papapostolou, A.; Karakosta, C.; Mexis, F.; Andreoulaki, I.; Psarras, J. A Fuzzy PROMETHEE Method for Evaluating Strategies towards a Cross-Country Renewable Energy Cooperation: The Cases of Egypt and Morocco. Energies 2024, 17, 4904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Zhang, K. The Overall Development of the Belt and Road Countries: Measurement and Assessment. Global Journal of Emerging Market Economies 2023, 15, 165–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Tian, H.; Zhu, H.; Cai, J. China actively promotes CO2 capture, utilization and storage research to achieve carbon peak and carbon neutrality. Advances in Geo-Energy Research 2021, 6, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, M.; Wei-dong, M.; Huang, B.; Li, T. Optimal wholesale price and technological innovation under dual credit policy on carbon emission reduction in a supply chain. Frontiers in Environmental Science 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, T.; Brent, K.; Wawryk, A.; Pettit, J.; Camatta, N. Hydrogen production in Australia from renewable energy: no doubt green and clean, but is it mean? Journal of Energy & Natural Resources Law 2023, 1–45. [Google Scholar]

- Azizivahed, A.; Arefi, A.; Ghavidel, S.; Shafie-khah, M.; Li, L.; Zhang, J.; Catalão, J. Energy Management Strategy in Dynamic Distribution Network Reconfiguration Considering Renewable Energy Resources and Storage. IEEE Transactions on Sustainable Energy 2019, 11, 662–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peukert, W.; Wasserscheid, P.; Hirsch, A. From molecules to materials: the cluster of excellence "engineering of advanced materials" at Friedrich-Alexander University of Erlangen-Nuremberg. Advanced Materials 2011, 23, 2508–2513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benedek, J.; Sebestyén, T.; Bartók, B. Evaluation of renewable energy sources in peripheral areas and renewable energy-based rural development. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2018, 90, 516–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peter, S. International Conference on Carbon Capture and Utilization (ICCCU-24): A Platform to Sustainability and Net-Zero Goals. ACS Energy Letters 2025, 1139–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khorsheed, M. Saudi Arabia: From Oil Kingdom to Knowledge-Based Economy. Middle East Policy 2015, 22, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottero, M.; Mondini, G. An appraisal of analytic network process and its role in sustainability assessment in Northern Italy. Management of Environmental Quality An International Journal 2008, 19, 642–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chupryna, I.; Tormosov, R.; Predun, K. Designing an effective eco-economic integration mechanism for sectoral projects within a diversified investment program. Ways to Improve Construction Efficiency 2023, 3, 283–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulton, J. China-Saudi Arabia Relations Through the '1+2+3' Cooperation Pattern. Asian Journal of Middle Eastern and Islamic Studies 2020, 14, 516–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharti, M.; Kumari, S. China's Belt and Road Initiative in Southeast Asia and its implications for ASEAN-China strategic partnership. Asian Review of Political Economy 2024, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, N.; Areche, F.; López, J.; Araujo, V.; Cárdenas, J.; Ober, J. Synergistic evaluation of energy security and environmental sustainability in BRICS geo-political entities: An integrated index framework. Equilibrium Quarterly Journal of Economics and Economic Policy 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Grigorescu, A.; Ion, A.; Lincaru, C.; Pîrciog, S. Synergy Analysis of Knowledge Transfer for the Energy Sector within the Framework of Sustainable Development of the European Countries. Energies 2021, 15, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsyganov, V. Progressive Adaptive Mechanisms for the International Cooperation. IFAC Proceedings Volumes 2008, 41, 6697–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polzin, F. Mobilizing private finance for low-carbon innovation - A systematic review of barriers and solutions. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2017, 77, 525–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, K.; Reilly, T. Northeast Asia's Energy Transition-Challenges for a Rules-Based Security and Economic Order. In SpringerBriefs in International Relations; Springer, 2023; pp. 97–117. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X. Prospects and Problems of Russian-Chinese Cooperation on the Transition to a Low-Carbon Energy Sector in the Context of Russian Strategic Planning Documents. Vestnik Volgogradskogo Gosudarstvennogo Universiteta. Ekonomika 2023, 2, 142–153. [Google Scholar]

- Priya, L. Rebooting India-GCC Energy Partnerships: Hydrogen as a Fuel for the Future. Strategic Analysis 2023, 47, 235–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Jung, T.; Dai, H.; Xiang, P.; Chen, S. Transition Pathways for Low-Carbon Steel Manufacture in East Asia: The Role of Renewable Energy and Technological Collaboration. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berezkin, M.; Sinyugin, O. Okhotsk Sea Renewable Energy Options for Japan's Energy Import Diversification. American Journal of Modern Energy 2022, 8, 1–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popov, S.; Maksakova, D.; Baldynov, O.; Korneev, K. Hydrogen Energy: a New Dimension for the Energy Cooperation in the Northeast Asian Region. E3S Web of Conferences 2020, 209, 05017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Kang, B.; Kim, S.; Kwon, W.; Kovsh, A. Russia's Energy Strategy in the Northeast Asian Region and New Korea-Russia Cooperation: Focusing on the Natural Gas and Hydrogen Sectors. SSRN Electronic Journal 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, J.; Son, S.; Jang, Y.; Ho, R.; Jung, J.; Lee, S.; Lee, S. Structural Changes in the Global Energy Market and Diversification Policy in Korea's Energy Cooperation with the Middle East. SSRN Electronic Journal 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, L. China's role in scaling up energy storage investments. Energy Storage and Saving 2023, 2, 415–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Lau, A.; Gong, Y. Electric Vehicles Empowering the Construction of Green Sustainable Transportation Networks in Chinese Cities: Dynamic Evolution, Frontier Trends, and Construction Pathways. Energies 2025, 18, 1943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J. Review of China's Energy Law and Its Impact on China's Future Energy Development. Lex Localis - Journal of Local Self-Government 2025, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Chai, Q.; Sha, F.; Wen, X. Modeling the implementation of NDCs and the scenarios below 2 degrees C for the Belt and Road countries. Ecosystem Health and Sustainability 2020, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, S.; Liu, G. Green Silk Road and Belt Economic Initiative and Local Sustainable Development: Through the Lens of China's Clean Energy Investment in Central Asia. International Journal of Environment and Climate Change 2024, 14, 480–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, N.; Coninck, H.; Sagar, A. Beyond technology transfer: Innovation cooperation to advance sustainable development in developing countries. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Energy and Environment 2021, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, P.; Hei, Z. Strategic analysis and framework design on international cooperation for energy transition: A perspective from China. Energy Reports 2022, 8, 2601–2616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thaler, P. The European Commission and the European Council: Coordinated Agenda setting in European energy policy. Journal of European Integration 2016, 38, 571–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Gao, X.; Bu, S.; Chan, K.; Zhou, B.; Xia, S. Cooperative Dispatch of Renewable-Penetrated Microgrids Alliances Using Risk-Sensitive Reinforcement Learning. IEEE Transactions on Sustainable Energy 2024, 15, 2194–2208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Shi, G. How Cooperation and Competition Arise in Regional Climate Policies: RICE as a Dynamic Game. IEEE Transactions on Control Systems Technology 2023, 32, 595–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parks, B.; Roberts, J. Inequality and the global climate regime: breaking the north-south impasse. Cambridge Review of International Affairs 2008, 21, 621–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popalzay, A. Regional diplomacy and economic cooperation: Examining Uzbekistan-Taliban relations in the post-2021 Afghan geopolitical landscape. Journal of Regional Studies 2025, 23. [Google Scholar]

- Stevanović, M.; Pavlićević, P.; Vujinović, N.; Radovanović, M. International relations challenges and sustainable development in developing countries after 2022: conceptualization of the risk assessment model. Energy Sustainability and Society 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.; Luo, F.; Bi, J. Uncertainty-aware prosumer coalitional game for peer-to-peer energy trading in community microgrids. International Journal of Electrical Power & Energy Systems 2024, 159, 110021. [Google Scholar]

- Szulecki, K.; Fischer, S.; Gullberg, A.; Sartor, O. Shaping the 'Energy Union': between national positions and governance innovation in EU energy and climate policy. Climate Policy 2016, 16, 548–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Huang, J. Cooperative Planning of Renewable Generations for Interconnected Microgrids. IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid 2016, 7, 2486–2496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO). PATENTSCOPE Search. Available online: https://www.wipo.int/patentscope/en/ (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- State Council of China. Opinions on Carbon Peaking and Carbon Neutrality Work. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2021-10/24/content_5644613.htm (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- Ministry of Trade; Industry and Energy (MOTIE); South Korea. Hydrogen Economy Revitalization Roadmap (2024 Revision). Available online: http://english.motie.go.kr/ (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- Reimers, N.; Gurevych, I. Sentence-BERT: Sentence embeddings using Siamese BERT-networks. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing and the 9th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (EMNLP-IJCNLP), Hong Kong, China, 3-7 November 2019; pp. 3982–3992. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations (UN). UN Comtrade Database. Available online: https://comtrade.un.org/ (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- International Energy Agency (IEA). Hydrogen Production and Infrastructure Projects Database. Available online: https://www.iea.org/data-and-statistics/data-product/hydrogen-production-and-infrastructure-projects-database (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- V-Dem Institute. Geopolitical Risk Index (GRI) Dataset. Available online: https://www.v-dem.net/en/data/data-vdem/ (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- National Bureau of Statistics of China (NBS). Energy Statistical Yearbook 2023. Available online: https://data.stats.gov.cn/ (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- Korea Energy Statistics Information System (KESIS). Hydrogen Energy Statistics. Available online: https://www.kesis.net/eng/index.do (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- International Organization for Standardization (ISO). ISO 19880-7:2024; Hydrogen technologies — Part 7: Safety of hydrogen transport by sea. [S]. 2025.

- Ministry of Trade; Industry and Energy (MOTIE); South Korea. China-Korea Hydrogen Cooperation White Paper (Chapter 3: Project Structure Analysis). Available online: http://english.motie.go.kr/ (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- National Energy Administration (NEA); China. 2018-2020 Cross-Border Hydrogen Project Record (Section 2: Investment Distribution). Available online: https://www.nea.gov.cn/ (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- Yancheng Economic and Technological Development Zone Management Committee. 2023 China-Korea Hydrogen Industry Forum: Post-Event Report (Section 4: Expert Consensus). Available online: https://kfq.yancheng.gov.cn/ (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- Bueno de Mesquita, B.; Smith, A. Institutional Change as a Response to Unrealized Threats: An Empirical Analysis. Journal of Conflict Resolution 2022, 67, 1032–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaffe, A. B.; Newell, R. G. Energy Technology Policy. Science 2003, 305, 983–987. [Google Scholar]

- International Energy Agency (IEA). Global Hydrogen Review 2023. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/global-hydrogen-review-2023 (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- China National Institute of Standardization; Korean Standards Association. Joint Report on Sino-Korean Hydrogen Standards Alignment; Technical Report; May 2024.

- Qingdao Port Group. Intelligent Logistics Platform for Hydrogen Transport. Available online: https://www.google.com/search?q=https://www.qingdaoport.net/ (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- Korean Immigration Service. Annual Report on Foreign Talent Visa Processing. Available online: https://www.immigration.go.kr (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- China-Korea Science and Technology Cooperation Center. Evaluation Report on Cross-Border Joint Laboratories 2024 Internal Report. 2024.

- Ministry of Trade; Industry and Energy (MOTIE); South Korea. 2024 Hydrogen Investment Report; Technical Report, 2024. Available online: http://english.motie.go.kr/ (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- China NEA-KEEI Joint Working Group. Policy Sandbox Framework for Sino-Korean Hydrogen Cooperation; Internal Report 2024.

- Ministry of Emergency Management (MEM); China. National Emergency Stockpile Guidelines for Strategic Energy Reserves; Policy Document 2024.

- Ministry of Emergency Management (MEM); China; Ministry of the Interior and Safety (MOIS); South Korea. Framework for Civil Emergency Logistics Coordination; Internal Policy Memo; 2025. [Google Scholar]

- China Electronics Technology Group (CETC). Bilingual DCCI Dashboard API Development Report. Available online: https://www.google.com/search?q=https://www.cetc.com.cn/ (accessed on 14 November 2025).

| Subsystem | Indicator Variable | Initial Weight | Mathematical Model / Calculation Logic |

|---|---|---|---|

| Technology Synergy (Tech) | 1. Patent Sharing Rate | 0.12 | Exponentially decayed ratio of joint patents to total patents |

| 2. Tech Transfer Efficiency | 0.10 | Ratio of licensing events to joint R&D projects | |

| 3. Standard Synchronization | 0.08 | Cosine similarity of technical standard document vectors (NLP) [46] | |

| 4. R&D Intensity | 0.10 | Normalized joint funding volume | |

| Regulatory Alignment (Policy) | 5. Regulatory Vector Similarity | 0.09 | Cosine similarity of policy document vectors (NLP) [46] |

| 6. Safety Protocol Overlap | 0.07 | Z-score standardized overlapping clauses in safety codes | |

| 7. Subsidy Correlation | 0.08 | Inverse difference of subsidy ratios: | |

| 8. Institutional Compatibility | 0.06 | Normalized score of bilateral technical mechanisms | |

| Supply Chain Resilience (Chain) | 9. Node Diversity | 0.08 | Ratio of cross-border nodes to total nodes |

| 10. Transport Reliability | 0.07 | Composite score: / Norm. Coeff. 1 [52] | |

| 11. Buffer Adequacy | 0.07 | Strategic reserve volume / 90-day consumption rate | |

| 12. Response Latency | 0.08 | Emergency drill frequency / Disruption events |

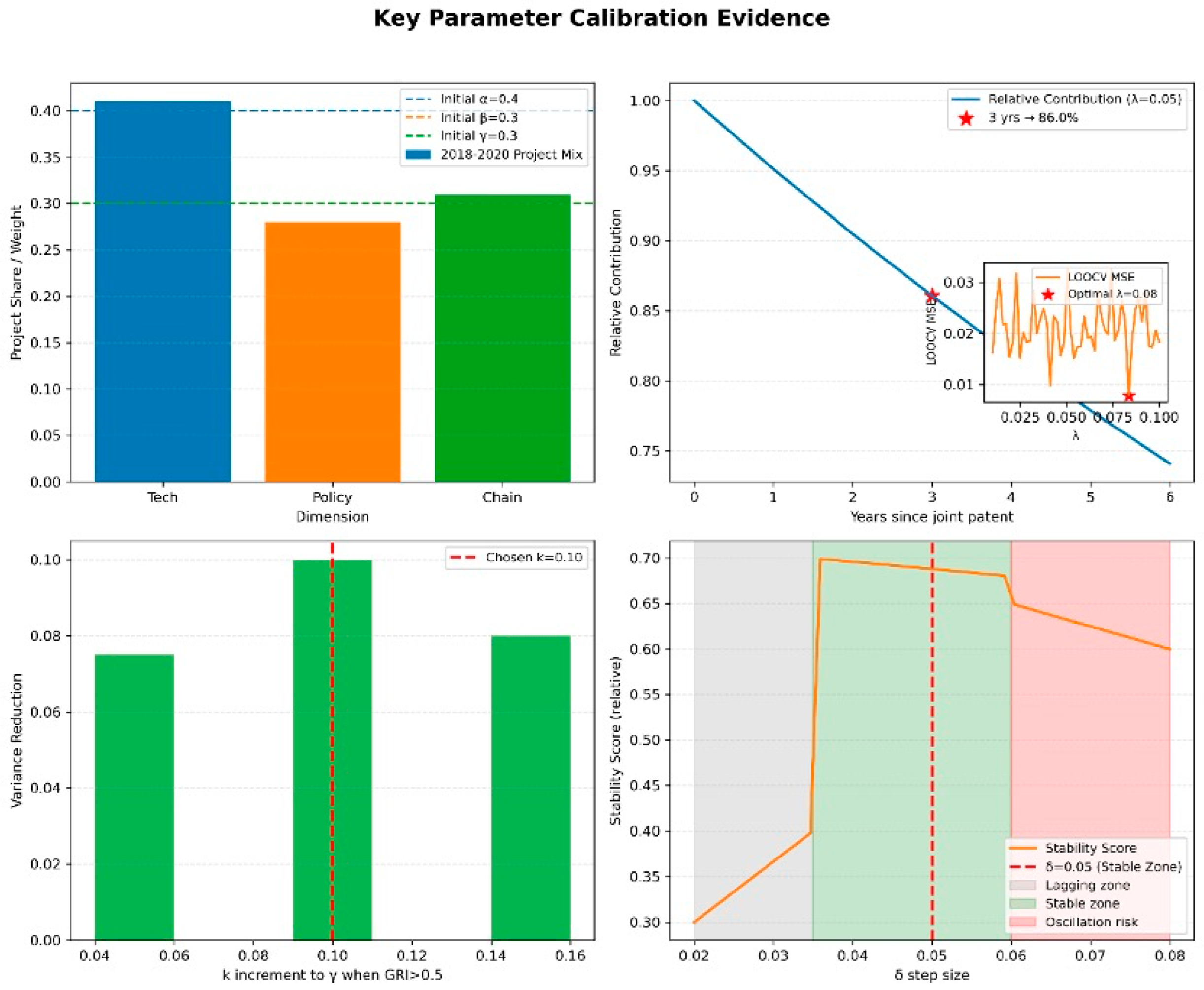

| Parameter | Value | Calibration Basis & Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Initial weights () | 0.4, 0.3, 0.3 | Mirrors 2018-2020 project mix (Tech 41%, Policy 28%, Chain 31%) and expert interviews [53-55]. |

| Technology decay rate () | 0.05 | Leave-one-out cross-validation (2015-2022 patents). Minimizes MSE (0.008) and retains 61% of 3-year contribution. |

| GRI Trigger Increment (k) | 0.10 | Simulated GRI ranges (0.42–0.58). Reduces DCCI variance by 11% without breaching weight constraints [49]. |

| Rolling Adjustment Step () | 0.05 | 5-period simulations balance timeliness (leads by 1 period) and stability (amplitude <0.12). |

| Tech Decline Penalty (p) | 0.05 | Monte Carlo simulations: 0.03-0.05 DCCI drop for "2q Tech decline + mild GRI rise" ensures timely alerts. |

| Year | GRI Value | Dynamic Weighting (Scenario A) | Static Weighting (Scenario B) | Score Difference (A-B) | Key Weight Adjustment (Scenario A) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | 0.42 | 0.38 | 0.36 | +0.02 | Initial weights () |

| 2021 | 0.45 | 0.41 | 0.40 | +0.01 | Performance trigger: Tech growth, increased to 0.42 |

| 2022 | 0.51 | 0.45 | 0.43 | +0.02 | Risk trigger: GRI>0.5, increased to 0.35; |

| 2023 | 0.55 | 0.47 | 0.47 | 0.00 | Stable weights () |

| 2024 | 0.58 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.00 | Stable weights () |

| ) | Technical / Operational Intervention | Expected System Response | Verifiable Metric |

|---|---|---|---|

| Technology Latency (Score 0.35) | 1. Protocol Synchronization: Accelerate alignment of 17 pending ISO-compatible standards. 2. Secure IP Architecture: Deploy a tiered-access IP custody platform with third-party verification. 3. Fast-Track R&D Nodes: Establish dedicated joint labs with expedited equipment clearance. | Increase Tech gain () efficiency; Raise score to 0.42. | Standards Alignment Score; Patent Velocity |

| Regulatory Divergence (Score 0.50) | 1. Subsidy Vector Alignment: Harmonize R&D credit calculations. 2. Carbon Credit Interoperability: Pilot mutual recognition of maritime carbon allowances. 3. Sandbox Testing: Joint pilot zones for experimental regulations [64]. | Stabilize Regulatory Alignment (); Reduce vector divergence. | Policy Similarity Vector |

| Resilience Risk (GRI Sensitivity) | 1. Dynamic Buffering: Implement dynamic inventory management for emergency stockpiles [65]. 2. Civil Logistics Coordination: Standardize protocols for hydrogen-powered emergency equipment [66]. 3. Data Corridor: Establish a desensitized data sharing protocol for transport safety. | Maintain Chain robustness (); Dampen perturbation shock. | Stockpile Sufficiency; Drill Frequency |

| Monitoring Latency (45 days) | 1. Real-time API: Deploy the Bilingual DCCI Dashboard API [67]. 2. Automated Reporting: Integrate project data feeds. | Reduce feedback loop latency to <7 days. | Data Update Frequency |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).