1. Introduction

DNA replication is a foundational process that facilitates the precise and timely transmission of genetic information from parent to daughter cells(1). This process is critical for cellular development and disease resistance(2). However, DNA duplication events are subject to continuous challenges posed by exogenous and endogenous factors, including the dynamic landscape of redox states and cellular metabolites that fuel cancer development and aging(3). Oxidative stress is a significant endogenous stress that contributes to the disarray of several cellular processes, including DNA replication. Consequently, cells exposed to chronic endogenous oxidative stress contribute to a significant source of replication stress(4).

Hydroxyurea (HU) is a small molecule recognized in the 1960s as a potent inhibitor of ribonucleotide reductase (RNR), the enzyme that catalyzes de novo dNTP synthesis (5). Its ability to suppress DNA synthesis led to early use in cancer chemotherapy in the 1960s, where it showed efficacy against chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML), melanoma, and other malignancies (6). Today, HU remains widely used in oncology and hematologic disorders and serves as a foundational experimental tool for studying DNA replication stress, checkpoint signaling, and genome instability in both yeast and mammalian systems(7-11).

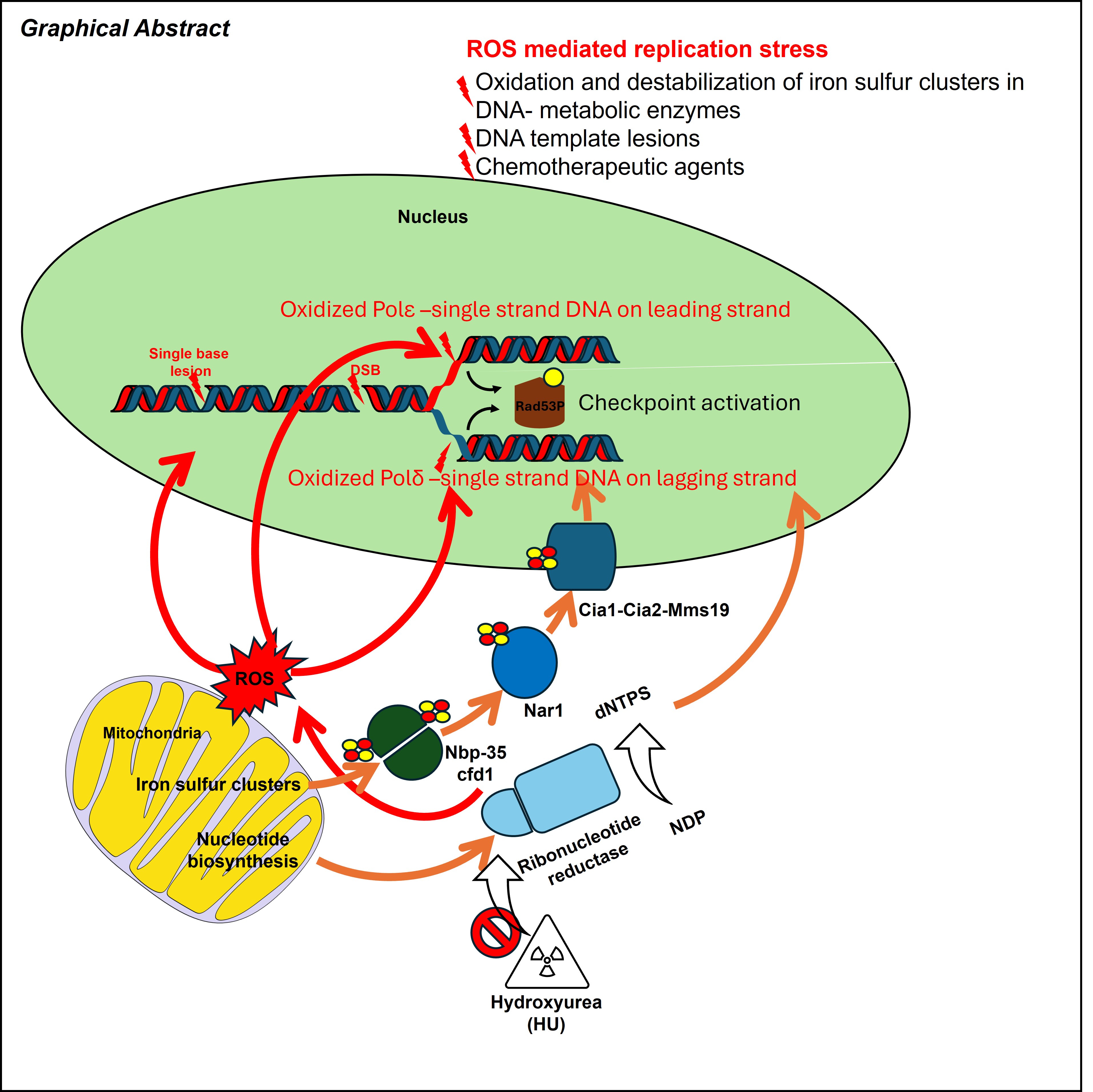

Here, we will review the basic knowledge of DNA replication process and S phase cell cycle checkpoint pathways. Then we discuss current understanding of HU’s working role on DNA forks through both Reactive oxygen species (ROS)-dependent and ROS-independent pathways and highlights emerging insights into how these mechanisms influence genome stability and may be exploited for therapeutic benefits.

2. Molecular Components of Core Eukaryotic Replisome

Eukaryotic DNA replication is performed by a highly conserved molecular machine whose core components are conserved from yeast to humans (12). The replisome coordinates the replication leading and lagging-strand synthesis, and its major structural and enzymatic modules are essential for maintaining replication accuracy and efficiency. At the heart of the replisome is the CMG helicase—an 11-subunit assembly composed of CDC45, the MCM2–7 complex, and the four-subunit GINS complex (Sld5, Psf1, Psf2, and Psf3) (13). Once activated at replication origins, the CMG helicase travels along the leading-strand template and unwinds the parental duplex DNA to initiate replication.

Closely associated with CMG is the primase–polymerase α complex (Pol α–primase), which synthesizes short RNA–DNA primers that initiate DNA synthesis on both strands (14)(15). Pol α maintains stable contacts with multiple replisome components, including Ctf4 (human AND-1) and CMG, ensuring that primer formation is tightly coupled to helicase movement. Although CMG bypasses protein and DNA obstacles predominantly on the leading-strand template, Pol α–primase predominantly acts on the lagging strand, where repeated primer synthesis is required for Okazaki fragment formation. After primer synthesis, the two replicative DNA polymerases take over nascent-strand elongation: Pol ε primarily extends the leading strand, whereas Pol δ synthesizes most of the lagging strand(16, 17). Pol ε maintains a strong and continuous physical association with the CMG helicase (16-18), enabling its rapid and coordinated progression with DNA unwinding. In contrast, the lagging-strand machinery—Pol δ, Pol α–primase, and the clamp loader RFC—interacts more transiently with the replisome as Okazaki fragments are iteratively initiated and extended. Both DNA synthesis strands is further supported by proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA), the sliding clamp that enhances polymerase processivity. Reconstituted yeast replication systems have shown that PCNA strongly stimulates Pol δ, increasing its nucleotide incorporation rate by more than tenfold compared with Pol ε (19). This differential stimulation contributes to the inherent asymmetry between the leading and lagging strands.

In addition to the replication core components, the evolutionarily conserved fork protection complex (FPC) also plays a critical role in promoting faithful replication. In budding yeast, the FPC components Mrc1 and Csm3/Tof1 (human CLASPIN and TIMELESS–TIPIN) travel with the CMG helicase throughout S phase. These proteins stabilize the replisome during both unperturbed and stressed conditions and promote rapid fork progression (20). Csm3/Tof1 enhances CMG-mediated DNA unwinding, which in turn facilitates stable Mrc1 recruitment. Together, these factors couple helicase activity with DNA synthesis and help maintain fork integrity when replication encounters obstacles.

3. Replication Checkpoint Activation

Initiation of the S-phase checkpoint: how replication stress generates ssDNA Cells encounter many endogenous and exogenous sources of replication stress—ROS, dNTP depletion (e.g., HU), DNA lesions, protein–DNA barriers, and defective replication factors(21). Extensive work in yeast and metazoans has revealed how the replisome responds to such stress and how this response triggers activation of the S-phase checkpoint. A common consequence of replication stress is uncoupling of the helicase and polymerase. When DNA polymerases stall at lesions or impediments while the CMG helicase continues unwinding, long stretches of single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) accumulate (22, 23) . RPA rapidly coats this ssDNA and serves as the primary signal for checkpoint activation (24). The effect of DNA lesions or block depends strongly on the strand on which the block occurs. Lagging-strand blocks are often bypassed by CMG, because the helicase translocates on the leading-strand template (25, 26) . These lesions usually generate short patches of ssDNA and interfere mainly with Okazaki fragment maturation (27). Leading-strand blocks stall CMG directly. In this case, CMG may still move slowly or transiently, but polymerase stalling produces substantial ssDNA on the leading strand due to helicase–polymerase uncoupling (26). This configuration is a potent trigger for S-phase checkpoint activation. Together, these scenarios illustrate that RPA-coated ssDNA is the universal initiator of the S-phase checkpoint, regardless of whether stress arises from exogenous damage, intrinsic replisome defects, or metabolic perturbations.

Recognition of ssDNA and Mec1/ATR recruitment At stalled forks, RPA-coated ssDNA recruits the yeast Mec1–Ddc2 complex (ATR–ATRIP in humans) (27, 28). Mec1/ATR is the primary kinase activated by replication stress. Tel1/ATM, which preferentially responds to double-strand breaks, contributes to certain types of damage but plays a smaller role at stalled forks (29, 30). Importantly, checkpoint activation in S phase requires more extensive ssDNA than in G1 or G2. This higher threshold prevents normal replication intermediates from inappropriately activating the checkpoint (31). Full Mec1/ATR activation requires loading of the 9-1-1 clamp (Ddc1–Rad17–Mec3; human RAD9–RAD1–HUS1), (32) by the clamp loader Rad24–RFC2-5. The 9-1-1 complex recruits Dpb11/TopBP1, a potent activator of Mec1/ATR kinase activity (33)

Downstream effectors: Rad53/CHK2 and Chk1/CHK1 Once activated, Mec1/ATR phosphorylates the effector kinases Rad53 (CHK2) and Chk1 (CHK1). Rad53/CHK2 activation during S phase requires Mrc1/CLASPIN (34) . Mrc1/CLASPIN travels with the replisome, interacting with Pol ε, MCM, and the Csm3/Tof1 complex (35), positioning it ideally for rapid response to fork stalling. Activated Rad53/CHK2 and Chk1 orchestrate a broad protective program: (A) Inhibition of late origin firing (Sld3 and Dbf4 in yeast; CDK-regulated pre-initiation factors in humans) (36); (B) Cell-cycle arrest, allowing time for repair; CHK1 additionally blocks G2/M progression by phosphorylating and inhibiting CDC25 phosphatases (37). In yeast, Rad53 stabilizes the securin Pds1 to prevent premature anaphase onset (38); (C) Stabilization and remodeling of stalled forks, including fork reversal; (D) Upregulation of dNTP synthesis(36); (E)Transcriptional activation of DNA damage response genes. Through these combined activities, the S-phase checkpoint preserves fork integrity, prevents collapse into double-strand breaks, and ensures that cells do not enter mitosis with under-replicated or damaged DNA.

4. HU Modulates Replication Fork Progression and Stability by ROS Independent Pathways (RNR Inhibition, Checkpoint Activations and Others)

RNR inhibition HU primarily acts by inhibiting ribonucleotide reductase (RNR), thereby lowering intracellular dNTP pools and slowing DNA synthesis. In budding yeast, depletion of Mec1—an activator of RNR transcription—results in reduced RNR activity(39), severely diminished dNTP levels, and pronounced replication slowing, ultimately leading to replication-fork collapse. Increasing RNR levels suppresses DNA damage in both Mec1- and ATR-depleted cells, highlighting the central role of dNTP availability in fork stability (40).

Checkpoint-mediated regulation of origin firing In budding yeast, high concentration HU suppress late origin firing through checkpoint pathway. In the timely origin system, activation of Mec1 at RPA-coated ssDNA leads to phosphorylation and activation of the effector kinase Rad53, which in turn inhibits key replication initiation factors. Rad53 phosphorylates Sld3 and Dbf4, the regulatory subunit of the Dbf4-dependent kinase Cdc7 (DDK), reducing its ability to activate MCM helicases at unfired origins. Through coordinated inhibition of both Sld3 and Dbf4, the Mec1–Rad53 checkpoint pathway prevents excessive origin firing, conserves limiting replication resources, and ensures that cells focus on stabilizing existing forks rather than initiating new ones (41, 42). This checkpoint-mediated origin suppression is essential for maintaining genome stability during HU-induced replication stress and other conditions that challenge replisome progression. Interestingly, HU’s action on late origin fire is RNR independent.

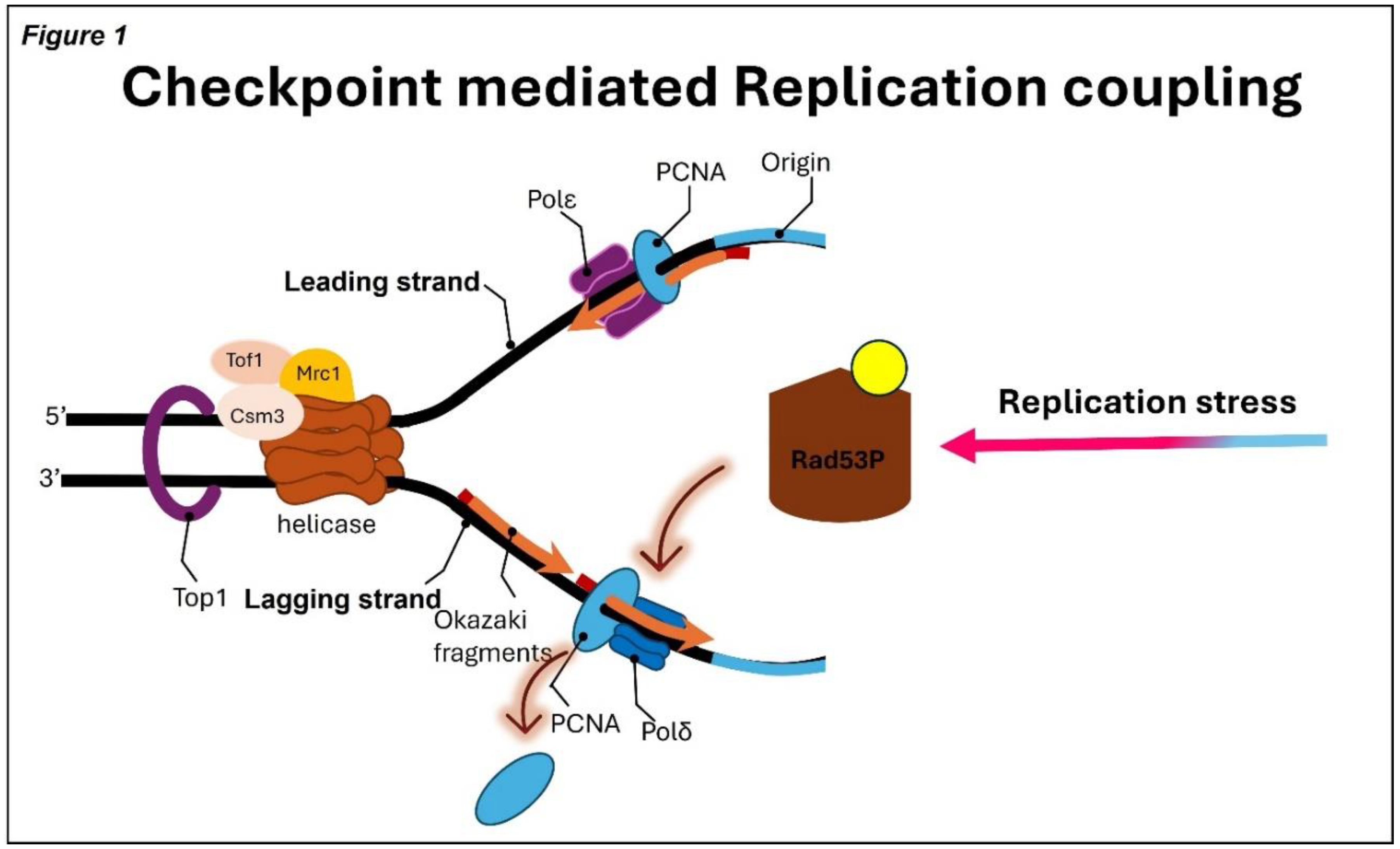

Replisome remodeling Recent strand-specific nascent DNA profiling approaches, such as eSPAN (enrichment and sequencing of protein-associated nascent DNA), have enabled high-resolution analysis of how leading and lagging-strand polymerases respond to replication stress

(43, 44). Under HU-induced replication stalling, one prominent structural alteration is the selective unloading of PCNA from the lagging strand, which reduces Pol δ processivity and slows Okazaki fragment synthesis

(45, 46). On the leading strand, Rad53 phosphorylates Mrc1, which weakens the ability of the Mrc1–Tof1–Csm3 fork protection complex to stimulate CMG helicase activity and may dampen Pol ε progression

(36) (

Figure 1). As a result, HU-treated forks frequently exhibit asymmetric synthesis, reduced lagging-strand extension, and partial uncoupling between helicase unwinding and polymerase activity. These coordinated structural changes represent protective adaptations that slow fork progression, prevent excessive ssDNA accumulation, and preserve fork integrity until replication can resume following HU removal.

A model illustrating Rad53-mediated fork stalling during HU-induced replication stress. Rad53 inhibits MCM helicase activity to restrict replication fork progression. As the fork stalls, PCNA is unloaded, effectively halting Pol δ–mediated DNA synthesis on the lagging strand.

Additional impact on replication stability and genome integrity Under HU, forks typically initiate at early origins and progress only ~8–9 kb before stalling (47). This stall appears largely stochastic and does not require Mec1 or Rad53 activity (48). Checkpoint mutants, however, display different sensitivities. mrc1Δ cells, which lack both the replication-coupling and checkpoint functions of Mrc1, show slow fork progression and hypersensitivity to HU (49). By contrast, mrc1AQ mutants, which retain Mrc1’s replisome-coupling activity but lack its checkpoint function, complete S phase with near-normal kinetics and show much greater resistance to HU than mrc1Δ cells (50, 51). This distinction emphasizes that fork progression defects in mrc1Δ cells arise largely from loss of replisome-coupling activity rather than checkpoint deficiency. Similarly, rad53 mutants display asymmetric DNA synthesis and hypersensitivity to HU, indicating that HU-induced fork slowing occurs independently of Mec1/Rad53-mediated arrest (23, 52, 53).

5. General Concepts of ROS and Their Impact on DNA Replication

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are generated continuously in cells as metabolic by-products and as signaling intermediates. At low or transient levels, ROS function in physiological signal transduction (54). However, sustained or excessive ROS induce oxidative stress, damaging proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids and promoting replication stress. Elevated ROS levels generate a variety of DNA lesions—including oxidized bases (e.g., 8-oxoguanine), abasic sites, and single- or double-strand breaks—that can impede replication-fork progression and compromise genome stability (4). Defects in antioxidant pathways or aberrant ROS accumulation are commonly observed in cancers and degenerative diseases, where they contribute to genomic instability and tumor progression (55).

ROS encompass both free radical and non-radical oxygen species, generated through mitochondrial respiration, inflammatory signals, oncogene activation, redox reactions, and environmental exposures (56, 57). Species include superoxide, hydroxyl, peroxyl, and alkoxyl radicals, as well as non-radical oxidants such as hydrogen peroxide, ozone, and hypochlorous acid. Interaction with nitrogen metabolism produces reactive nitrogen species (RNS), such as nitric oxide and peroxynitrites (58).

ROS damage DNA directly but also affect replisome components, particularly proteins that depend on iron–sulfur clusters (ISCs). Many essential replication enzymes—including DNA polymerases δ and ε, primase, FANCJ, and XPD—require ISCs for catalytic activity and structural integrity (

Table 1). Because ISCs are highly sensitive to oxidation, ROS can inactivate these proteins, slow fork progression, and increase helicase–polymerase uncoupling. When polymerases stall at oxidative lesions while the CMG helicase continues unwinding, long regions of single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) accumulate. RPA binding to ssDNA recruits Mec1–Ddc2 (ATR–ATRIP), activating the S-phase checkpoint to stabilize forks, adjust replication timing, and promote repair. Chronic oxidative stress overwhelms these protective pathways, leading to fork collapse, DSB formation, mutagenesis, structural rearrangements, and oncogene activation

(59).

6. HU Contributes to Replication Stress and Genome Instability Through ROS-dependent Pathways

Hydroxyurea (HU) is widely used in research and cancer therapy and traditionally viewed as an inhibitor of ribonucleotide reductase (RNR). However, growing evidence demonstrates that HU also induces oxidative stress, and that ROS contribute significantly to HU-mediated replication defects (8, 60, 61).

ROS-mediated effects on Ribonucleotide Reductase. RNR function depends on both the ferric–tyrosyl radical and multiple ISC-containing proteins such as Dre2–Tah18 (62). Because these cofactors are sensitive to oxidation, HU-induced ROS can further impair RNR assembly and function, amplifying replication stress.

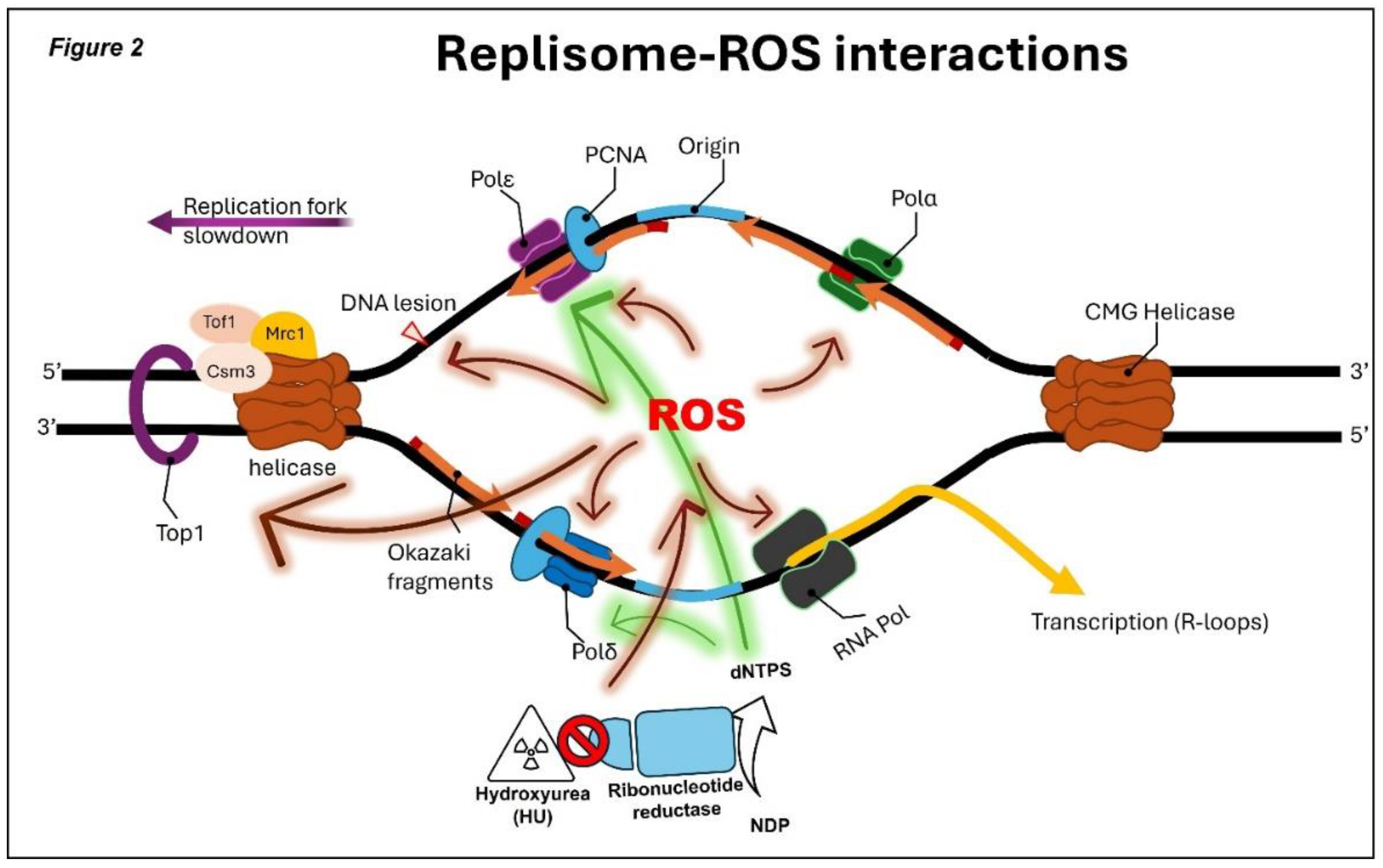

ROS effects on the replisome ROS produced during HU exposure affect replication in several ways. First, they oxidize ISCs within replicative polymerases and other DNA-metabolic enzymes, destabilizing replisome components and slowing fork progression

(7) (

Figure 2). In budding yeast, HU disrupts cytosolic ISC biogenesis via ROS generation, establishing a direct link between HU treatment and ISC pathway dysfunction

(9). Second, HU-induced ROS modulates replisome regulators. Low oxidative conditions promote oligomerization of peroxiredoxin 2, stabilizing the human TIMELESS–TIPIN complex and supporting fork progression. Higher ROS levels oxidize peroxiredoxin subunits, causing TIMELESS dissociation from chromatin and slowing fork movement. Consistent with redox involvement, HU-induced fork inhibition can be partially rescued by antioxidants such as N-acetylcysteine or ascorbic acid, but not by exogenous dNTPs

(7).

Possible roles of ROS (reactive oxygen species) in yeast replication stress response. Replication stress causes replication fork stalling. The resumption of DNA replication requires the replisome to be maintained on DNA until the stress is removed, the preservation of the replication fork structure, and DNA lesions repaired and complete DNA replication. As several Fe-S proteins are involved in these processes, the ROS pathway may contribute to replication stress by destabilizing some or all these factors by oxidation. Specifically, it could destabilize DNA polymerases on DNA or impair the activity of nucleases and helicases which participate in fork remodeling and the restoration of a functional replication fork. In addition, ROS appears to regulate the transcription on DNA that causes conflicts between replication and transcription. Lastly, ROS appear to be reason for replication stress caused by HU, although the molecular mechanism underlying this regulation remains unclear.

ROS-Induced transcription–replication conflicts and cell-cycle perturbations HU-induced oxidative stress increases transcription and promotes R-loop formation, leading to collisions between transcription and replication machinery, a major source of fork stalling in human cells (8). Yeast cells respond to oxidative stress by modulating replication timing through ROS-sensitive transcription factors such as Swi6 (63). Additionally, HU-induced ROS influence cell-cycle progression: oxidative stress can induce G2/M arrest through CHK1 activation or direct oxidation of CDC25 phosphatases (64), whereas specific mitochondrial ROS signals can oxidize CDK2 to promote S-phase entry (65).

Collectively, HU acts through multiple mechanisms to disrupt replication fork integrity and promote genome instability.

7. Conclusions Remarks and Future Perspectives

Hydroxyurea (HU) has long been used as a tool compound and anticancer drug, classically defined by its ability to inhibit ribonucleotide reductase, deplete dNTP pools, and stall replication forks. Studies using budding yeast and mammalian cells now reveal a far more complex picture in which HU-induced replication stress and genome instability arise from an interplay between nucleotide limitation, oxidative stress, and replisome remodeling. HU not only slows forks by reducing dNTP availability but also perturbs redox homeostasis, leading to ROS accumulation, oxidation of DNA and proteins, and disruption of iron–sulfur cluster (ISC)–dependent replication factors. These insults converge on the replication fork, promoting helicase–polymerase uncoupling, excessive ssDNA formation, checkpoint activation, and, when protective responses fail, fork collapse and chromosome breakage. Together, these findings support a model in which HU acts not as a single-target inhibitor, but as a multifaceted stressor that probes the robustness of replication and DNA damage response networks.

Despite significant progress, many important questions remain. At the mechanistic level, we still lack detailed structural and kinetic insights into how individual replisome components—particularly ISC-containing polymerases and helicases—respond to HU-induced ROS in vivo, and whether these responses differ between leading- and lagging-strand machinery. Strand-specific nascent DNA profiling methods, such as eSPAN and related technologies, have already revealed highly asymmetric replication patterns under HU, and further refinement of such tools may elucidate how fork architecture and enzyme dynamics evolve throughout HU exposure. The concentration- and time-dependent effects of HU on fork reversal, resection, and restart also require deeper exploration, ideally with single-molecule, time-resolved, and in vitro reconstitution approaches. Additionally, the interplay among HU, ROS, and transcription–replication conflicts—including R-loop formation and resolution—represents an emerging area where yeast genetics and mammalian models will continue to provide complementary insights.

Clinically, HU remains a frontline therapy for several hematologic malignancies and sickle cell disease, yet patient responses and long-term genomic consequences are variable and incompletely understood. Integrating HU’s redox effects with its canonical role in dNTP depletion may help explain differential sensitivity among tumors with defects in checkpoint signaling, antioxidant pathways, or ISC biogenesis. Future work should explore whether modulation of ROS (for example, via antioxidants or pro-oxidants), targeting ISC assembly factors, or manipulating fork protection pathways can be exploited to enhance HU efficacy or limit HU-induced genome instability in normal tissues. Ultimately, a deeper mechanistic understanding of HU-induced replication stress in yeast and mammals promises not only to refine how we use HU therapeutically, but also to illuminate general principles of how cells maintain genome stability under conditions of metabolic and oxidative challenge.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, SK; writing—original draft preparation, SK, CY; writing—review and editing, SK and CY. Both SK and CY have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

NIH R01GM130588; Hormel Startup Fund.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We thank all lab members of Dr. Chuanhe Yu.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of Interest.

References

- Alabert, C.; Bukowski-Wills, J.-C.; Lee, S.-B.; Kustatscher, G.; Nakamura, K.; Alves, F.D.L.; Menard, P.; Mejlvang, J.; Rappsilber, J.; Groth, A. Nascent chromatin capture proteomics determines chromatin dynamics during DNA replication and identifies unknown fork components. Nat. Cell Biol. 2014, 16, 281–291. [CrossRef]

- Zoghbi, H.Y.; Beaudet, A.L. Epigenetics and Human Disease. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2016, 8, a019497. [CrossRef]

- Luo, M.; He, H.; Kelley, M.R.; Georgiadis, M.M. Redox Regulation of DNA Repair: Implications for Human Health and Cancer Therapeutic Development. Antioxidants Redox Signal. 2010, 12, 1247–1269. [CrossRef]

- Venkatachalam, G.; Surana, U.; Clément, M.-V. Replication stress-induced endogenous DNA damage drives cellular senescence induced by a sub-lethal oxidative stress. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, 10564–10582. [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, W. N., and Carbone, P. P. (1963) Hydroxyurea: Mechanism of Action, Science 142, 1069-1070.

- Kennedy, B.J. The evolution of hydroxyurea therapy in chronic myelogenous leukemia.. 1992, 19, 21–6.

- Shaw, A.E.; Mihelich, M.N.; Whitted, J.E.; Reitman, H.J.; Timmerman, A.J.; Tehseen, M.; Hamdan, S.M.; Schauer, G.D. Revised mechanism of hydroxyurea-induced cell cycle arrest and an improved alternative. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2024, 121. [CrossRef]

- Andrs, M.; Stoy, H.; Boleslavska, B.; Chappidi, N.; Kanagaraj, R.; Nascakova, Z.; Menon, S.; Rao, S.; Oravetzova, A.; Dobrovolna, J.; et al. Excessive reactive oxygen species induce transcription-dependent replication stress. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.-E.; Facca, C.; Fatmi, Z.; Baïlle, D.; Bénakli, S.; Vernis, L. DNA replication inhibitor hydroxyurea alters Fe-S centers by producing reactive oxygen species in vivo. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 29361. [CrossRef]

- Koç, A.; Wheeler, L.J.; Mathews, C.K.; Merrill, G.F. Hydroxyurea Arrests DNA Replication by a Mechanism That Preserves Basal dNTP Pools. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 223–230. [CrossRef]

- Musialek, M. W., and Rybaczek, D. (2021) Hydroxyurea-The Good, the Bad and the Ugly, Genes (Basel) 12.

- Jenkyn-Bedford, M.; Jones, M.L.; Baris, Y.; Labib, K.P.M.; Cannone, G.; Yeeles, J.T.P.; Deegan, T.D. A conserved mechanism for regulating replisome disassembly in eukaryotes. Nature 2021, 600, 743–747. [CrossRef]

- Dang, H.Q.; Li, Z. The Cdc45·Mcm2–7·GINS Protein Complex in Trypanosomes Regulates DNA Replication and Interacts with Two Orc1-like Proteins in the Origin Recognition Complex. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 32424–32435. [CrossRef]

- Aria, V.; Yeeles, J.T. Mechanism of Bidirectional Leading-Strand Synthesis Establishment at Eukaryotic DNA Replication Origins. Mol. Cell 2019, 73, 199–211.e10. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z.; Georgescu, R.; Li, H.; O’dOnnell, M.E. Molecular choreography of primer synthesis by the eukaryotic Pol α-primase. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- McElhinny, S.A.N.; Gordenin, D.A.; Stith, C.M.; Burgers, P.M.; Kunkel, T.A. Division of Labor at the Eukaryotic Replication Fork. Mol. Cell 2008, 30, 137–144. [CrossRef]

- Stillman, B. DNA Polymerases at the Replication Fork in Eukaryotes. Mol. Cell 2008, 30, 259–260. [CrossRef]

- Pursell, Z.F.; Isoz, I.; Lundström, E.-B.; Johansson, E.; Kunkel, T.A. Yeast DNA Polymerase ε Participates in Leading-Strand DNA Replication. Science 2007, 317, 127–130. [CrossRef]

- Yeeles, J.T.; Janska, A.; Early, A.; Diffley, J.F. How the Eukaryotic Replisome Achieves Rapid and Efficient DNA Replication. Mol. Cell 2017, 65, 105–116. [CrossRef]

- Keszthelyi, A.; Mansoubi, S.; Whale, A.; Houseley, J.; Baxter, J. The fork protection complex generates DNA topological stress–induced DNA damage while ensuring full and faithful genome duplication. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2024, 121. [CrossRef]

- Saxena, S.; Zou, L. Hallmarks of DNA replication stress. Mol. Cell 2022, 82, 2298–2314. [CrossRef]

- Byun, T.S.; Pacek, M.; Yee, M.-C.; Walter, J.C.; Cimprich, K.A. Functional uncoupling of MCM helicase and DNA polymerase activities activates the ATR-dependent checkpoint. Genes Dev. 2005, 19, 1040–1052. [CrossRef]

- Serra-Cardona, A.; Yu, C.; Zhang, X.; Hua, X.; Yao, Y.; Zhou, J.; Gan, H.; Zhang, Z. A mechanism for Rad53 to couple leading- and lagging-strand DNA synthesis under replication stress in budding yeast. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2021, 118. [CrossRef]

- Feng, W.; Collingwood, D.; Boeck, M.E.; Fox, L.A.; Alvino, G.M.; Fangman, W.L.; Raghuraman, M.K.; Brewer, B.J. Genomic mapping of single-stranded DNA in hydroxyurea-challenged yeasts identifies origins of replication. Nat. Cell Biol. 2006, 8, 148–155. [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.V.; Yardimci, H.; Long, D.T.; Ho, T.V.; Guainazzi, A.; Bermudez, V.P.; Hurwitz, J.; Van Oijen, A.; Schärer, O.D.; Walter, J.C. Selective Bypass of a Lagging Strand Roadblock by the Eukaryotic Replicative DNA Helicase. Cell 2011, 146, 931–941. [CrossRef]

- Sparks, J.L.; Chistol, G.; Gao, A.O.; Räschle, M.; Larsen, N.B.; Mann, M.; Duxin, J.P.; Walter, J.C. The CMG Helicase Bypasses DNA-Protein Cross-Links to Facilitate Their Repair. Cell 2019, 176, 167–181.e21. [CrossRef]

- Maréchal, A.; Zou, L. RPA-coated single-stranded DNA as a platform for post-translational modifications in the DNA damage response. Cell Res. 2014, 25, 9–23. [CrossRef]

- Brush, G.S.; Morrow, D.M.; Hieter, P.; Kelly, T.J. The ATM homologue MEC1 is required for phosphorylation of replication protein A in yeast. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1996, 93, 15075–15080. [CrossRef]

- Clerici, M.; Trovesi, C.; Galbiati, A.; Lucchini, G.; Longhese, M.P. Mec1/ATR regulates the generation of single-stranded DNA that attenuates Tel1/ATM signaling at DNA ends. EMBO J. 2013, 33, 198–216. [CrossRef]

- Tannous, E.A.; Burgers, P.M. Novel insights into the mechanism of cell cycle kinases Mec1(ATR) and Tel1(ATM). Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2021, 56, 441–454. [CrossRef]

- Navadgi-Patil, V.M.; Burgers, P.M. Cell-cycle-specific activators of the Mec1/ATR checkpoint kinase. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2011, 39, 600–605. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, F.; Georgescu, R.E.; Yao, N.Y.; O’donnell, M.E.; Li, H. DNA is loaded through the 9-1-1 DNA checkpoint clamp in the opposite direction of the PCNA clamp. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2022, 29, 376–385. [CrossRef]

- Navadgi-Patil, V.M.; Burgers, P.M. Yeast DNA Replication Protein Dpb11 Activates the Mec1/ATR Checkpoint Kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 35853–35859. [CrossRef]

- Villa, M.; Bonetti, D.; Carraro, M.; Longhese, M.P. Rad9/53 BP 1 protects stalled replication forks from degradation in Mec1/ ATR -defective cells. Embo Rep. 2018, 19, 351–367. [CrossRef]

- Hodgson, B.; Calzada, A.; Labib, K. Mrc1 and Tof1 Regulate DNA Replication Forks in Different Ways during Normal S Phase. Mol. Biol. Cell 2007, 18, 3894–3902. [CrossRef]

- McClure, A.W.; Diffley, J.F. Rad53 checkpoint kinase regulation of DNA replication fork rate via Mrc1 phosphorylation. eLife 2021, 10. [CrossRef]

- Uto, K.; Inoue, D.; Shimuta, K.; Nakajo, N.; Sagata, N. Chk1, but not Chk2, inhibits Cdc25 phosphatases by a novel common mechanism. EMBO J. 2004, 23, 3386–3396. [CrossRef]

- Zur, A.; Brandeis, M. Securin degradation is mediated by fzy and fzr, and is required for complete chromatid separation but not for cytokinesis. EMBO J. 2001, 20, 792–801. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Muller, E.G.; Rothstein, R. A Suppressor of Two Essential Checkpoint Genes Identifies a Novel Protein that Negatively Affects dNTP Pools. Mol. Cell 1998, 2, 329–340. [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.-H.; Smolka, M.B.; Zhou, H. Mechanism of Dun1 Activation by Rad53 Phosphorylation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 986–995. [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Mosqueda, J.; Maas, N.L.; Jonsson, Z.O.; DeFazio-Eli, L.G.; Wohlschlegel, J.; Toczyski, D.P. Damage-induced phosphorylation of Sld3 is important to block late origin firing. Nature 2010, 467, 479–483. [CrossRef]

- Zegerman, P.; Diffley, J.F.X. Checkpoint-dependent inhibition of DNA replication initiation by Sld3 and Dbf4 phosphorylation. Nature 2010, 467, 474–478. [CrossRef]

- Karri, S.; Dickinson, Q.; Li, Z.; Yu, C.; Zhang, Z. Strand-Specific Analysis of Proteins at Replicating DNA Strands by Enrichment and Sequencing of Protein-Associated Nascent DNA Method. J. Vis. Exp. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Gan, H.; Zhang, Z. (2018) Strand-Specific Analysis of DNA Synthesis and Proteins Association with DNA Replication Forks in Budding Yeast, In Genome Instability: Methods and Protocols (Muzi-Falconi, M., and Brown, G. W., Eds.), pp 227-238, Springer New York, New York, NY.

- Thakar, T.; Leung, W.; Nicolae, C.M.; Clements, K.E.; Shen, B.; Bielinsky, A.-K.; Moldovan, G.-L. Ubiquitinated-PCNA protects replication forks from DNA2-mediated degradation by regulating Okazaki fragment maturation and chromatin assembly. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Serra-Cardona, A.; Hua, X.; McNutt, S.W.; Zhou, H.; Toda, T.; Jia, S.; Chu, F.; Zhang, Z. The PCNA–Pol δ complex couples lagging strand DNA synthesis to parental histone transfer for epigenetic inheritance. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eadn5175. [CrossRef]

- Lengronne, A.; Pasero, P.; Bensimon, A.; Schwob, E. Monitoring S phase progression globally and locally using BrdU incorporation in TK+ yeast strains. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001, 29, 1433–1442. [CrossRef]

- Raveendranathan, M.; Chattopadhyay, S.; Bolon, Y.; Haworth, J.; Clarke, D.J.; Bielinsky, A. Genome-wide replication profiles of S-phase checkpoint mutants reveal fragile sites in yeast. EMBO J. 2006, 25, 3627–3639. [CrossRef]

- Koren, A.; Soifer, I.; Barkai, N. MRC1-dependent scaling of the budding yeast DNA replication timing program. Genome Res. 2010, 20, 781–790. [CrossRef]

- Naylor, M.L.; Li, J.-M.; Osborn, A.J.; Elledge, S.J. Mrc1 phosphorylation in response to DNA replication stress is required for Mec1 accumulation at the stalled fork. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2009, 106, 12765–12770. [CrossRef]

- Osborn, A.J.; Elledge, S.J. Mrc1 is a replication fork component whose phosphorylation in response to DNA replication stress activates Rad53. Genes Dev. 2003, 17, 1755–1767. [CrossRef]

- Gan, H.; Yu, C.; Devbhandari, S.; Sharma, S.; Han, J.; Chabes, A.; Remus, D.; Zhang, Z. Checkpoint Kinase Rad53 Couples Leading- and Lagging-Strand DNA Synthesis under Replication Stress. Mol. Cell 2017, 68, 446–455.e3. [CrossRef]

- Yu, C., Gan, H., and Zhang, Z. (2017) Both DNA Polymerases delta and epsilon Contact Active and Stalled Replication Forks Differently, Mol Cell Biol 37.

- Hong, Y.; Boiti, A.; Vallone, D.; Foulkes, N.S. Reactive Oxygen Species Signaling and Oxidative Stress: Transcriptional Regulation and Evolution. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 312. [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, V.; Tuli, H.S.; Varol, A.; Thakral, F.; Yerer, M.B.; Sak, K.; Varol, M.; Jain, A.; Khan, M.A.; Sethi, G. Role of Reactive Oxygen Species in Cancer Progression: Molecular Mechanisms and Recent Advancements. Biomolecules 2019, 9, 735. [CrossRef]

- Phaniendra, A.; Jestadi, D.B.; Periyasamy, L. Free Radicals: Properties, Sources, Targets, and Their Implication in Various Diseases. Indian J. Clin. Biochem. 2015, 30, 11–26. [CrossRef]

- Schieber, M.; Chandel, N.S. ROS Function in Redox Signaling and Oxidative Stress. Curr. Biol. 2014, 24, R453–R462. [CrossRef]

- Weidinger, A.; Kozlov, A.V. Biological Activities of Reactive Oxygen and Nitrogen Species: Oxidative Stress versus Signal Transduction. Biomolecules 2015, 5, 472–484. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; An, B.; Lin, Y.; Ni, Y.; Zhao, X.; Liang, X. Molecular mechanisms of ROS-modulated cancer chemoresistance and therapeutic strategies. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 165, 115036. [CrossRef]

- Somyajit, K.; Gupta, R.; Sedlackova, H.; Neelsen, K.J.; Ochs, F.; Rask, M.-B.; Choudhary, C.; Lukas, J. Redox-sensitive alteration of replisome architecture safeguards genome integrity. Science 2017, 358, 797–802. [CrossRef]

- Heinke, L. Mitochondrial ROS drive cell cycle progression. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2022, 23, 581–581. [CrossRef]

- Vernis, L.; Facca, C.; Delagoutte, E.; Soler, N.; Chanet, R.; Guiard, B.; Faye, G.; Baldacci, G. A Newly Identified Essential Complex, Dre2-Tah18, Controls Mitochondria Integrity and Cell Death after Oxidative Stress in Yeast. PLOS ONE 2009, 4, e4376. [CrossRef]

- Chiu, J.; Tactacan, C.M.; Tan, S.-X.; Lin, R.C.; Wouters, M.A.; Dawes, I.W. Cell Cycle Sensing of Oxidative Stress in Saccharomyces cerevisiae by Oxidation of a Specific Cysteine Residue in the Transcription Factor Swi6p. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 5204–5214. [CrossRef]

- Rudolph, J. Redox Regulation of the Cdc25 Phosphatases. Antioxidants Redox Signal. 2005, 7, 761–767. [CrossRef]

- Kirova, D.G.; Judasova, K.; Vorhauser, J.; Zerjatke, T.; Leung, J.K.; Glauche, I.; Mansfeld, J. A ROS-dependent mechanism promotes CDK2 phosphorylation to drive progression through S phase. Dev. Cell 2022, 57, 1712–1727.e9. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).