1. Introduction

Marine ecosystems play a vital role in maintaining the planet’s ecological balance and supporting a diverse array of species. However, these ecosystems are under increasing threat from human activities such as overfishing, coastal development and invasive species. The often-competing demands for marine space and resources are projected to rise, creating an even more challenging environment for these ecosystems [

1]. OECD (2017) reports that costs associated with poor ocean management practices extend beyond the environmental sphere and have social ramifications.

These costs are often not factored into decision-making processes. This oversight undermines the resilience of the ecosystems that we rely on for food, income, and other, often less visible, life-support functions such as coastal protection, habitat provisioning, and carbon sequestration. Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) represent a critical policy instrument in addressing these challenges. They play a pivotal role in ensuring the conservation and sustainable use of our vast yet vulnerable marine ecosystems.

While global efforts persist to increase the coverage of MPAs, there is an urgent need to strategically locate them in areas under significant threat. At the same time, a considerable proportion of MPAs worldwide, including those in the Mediterranean, have been criticized as ‘paper parks’ where legal designation is not matched by effective management or enforcement [

2].

In Malta, MPAs are designated as part of the Natura 2000 network. Unlike cases where Natura 2000 sites have been criticized as ‘paper parks’ due to lack of management, Maltese marine Natura 2000 sites are subject to concrete management through legally binding conservation objectives and measures [

3]. These include site-specific objectives, for example, to maintain Posidonia oceanica meadows, reefs, and sandbanks at Favourable Conservation Status, together with operational and general measures to regulate human activities, improve knowledge, and ensure enforcement.; however, as discussed in later sections, challenges remain regarding enforcement and stakeholder conflicts that can hinder full implementation.

The assessment and implementation of effective management strategies, therefore, require methods capable of capturing multiple pressures simultaneously.

Despite the establishment of MPAs as a conservation strategy, the effectiveness of these areas in safeguarding marine biodiversity is contingent upon a comprehensive understanding of the diverse and escalating human pressures that impede their success. Overfishing and exploitation have intensified over the decades: the proportion of fish stocks classified as overfished rose from around 10 percent in 1974 to approximately 31 percent by 2013 [

4]. Additionally, illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing continues to extract a toll, with annual losses of 11-26 million tonnes of fish, equivalent to an 18% mean loss across all fisheries [

1].

Marine pollution, stemming primarily from land-based sources like industrial, agricultural, and residential waste, poses a pervasive threat. It not only disrupts marine ecosystems but can also facilitate biological invasions. For example, plastics and other marine litter act as rafting vectors for non-indigenous species, while eutrophication and chronically polluted harbours reduce ecosystem resistance and favor the spread of invasive macroalgae such as

Caulerpa cylindracea [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9].

Simultaneously, habitat destruction from activities such as bottom trawling, destructive fishing practices, and coastal development causes long-lasting degradation of critical habitats, including seagrass meadows, reefs, and soft-bottom ecosystems in the Mediterranean [

10,

11,

12].

Climate change compounds these pressures, impacting species and ecosystems already strained by other threats. In fact, according to the OECD (2017) report on MPAs, climate-related effects have led to the loss or degradation of 50% of salt marshes, 35% of mangroves, 30% of coral reefs, and 20% of seagrass worldwide. Invasive alien species further exacerbate the challenges, altering native ecosystems, driving flora and fauna to extinction, degrading water quality, and intensifying competition and predation among species.

A key contribution of this study is the use of cumulative, normalized vessel density across several habitat types within a single MPA. This integrated spatial approach allows not only for a more accurate representation of human pressures, but also provides policy-relevant insights for designing habitat-specific management strategies and advancing ecosystem-based marine spatial planning. It is important to note that while vessel presence and density provide a useful proxy for potential ecological pressure, this study does not directly quantify biophysical impacts. The links to ecological effects are therefore to be interpreted as indicative rather than definitive.

2. Study Area

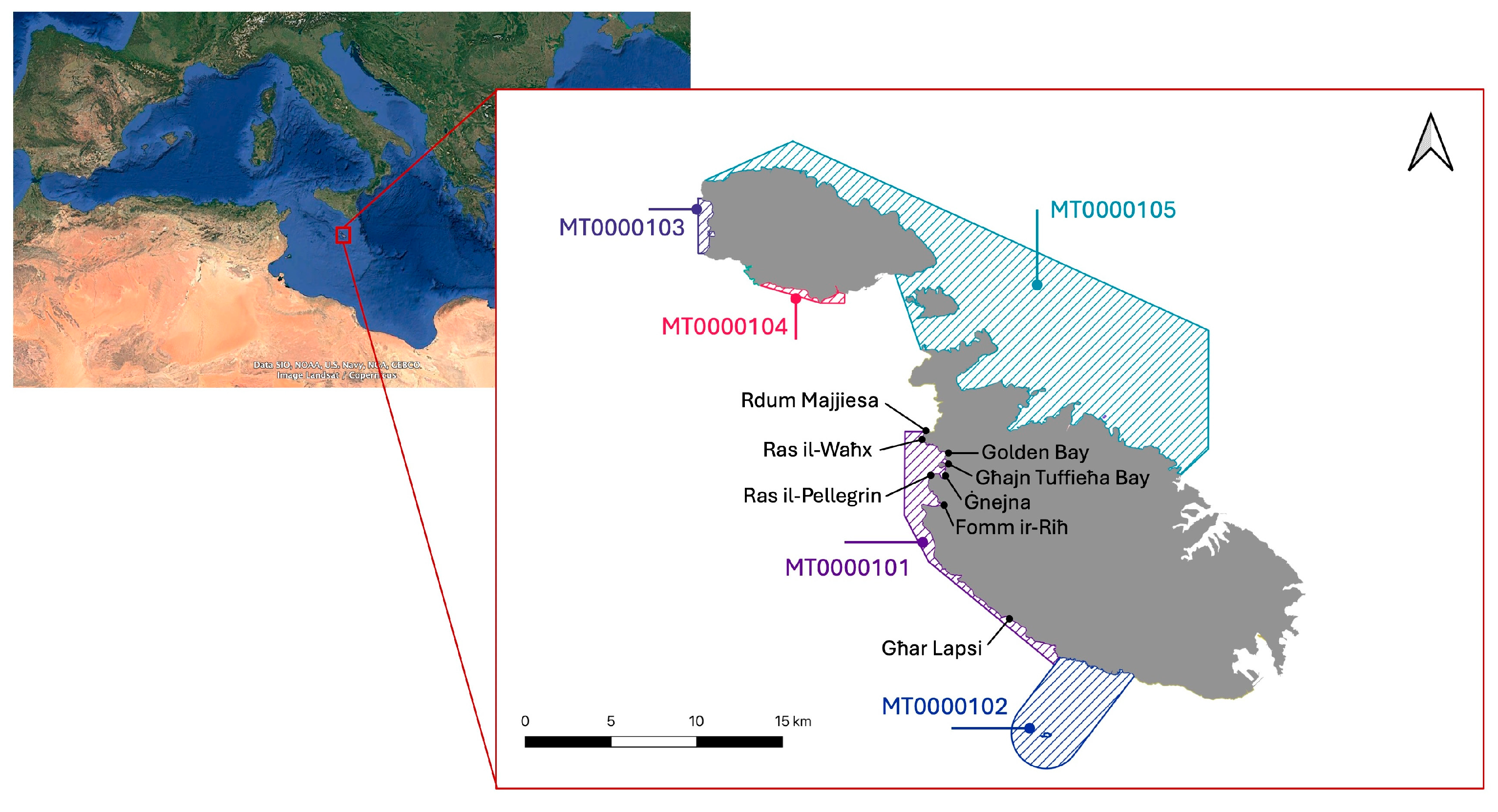

The Maltese Islands is an archipelagic European state that lies in the central Mediterranean, around 90 km to the south of Sicily and about 260 km to the north of the North African coastline. It is composed of the three main islands, i.e. Malta, Gozo, and Comino, as well as several smaller, uninhabited islets (

Figure 1). The seabed between Malta and Sicily features relatively shallow depths, averaging around 150 metres, with a gentle gradient that extends in a north–south orientation.

Malta has dedicated approximately 4,138km

2 of marine waters to the preservation of critical marine habitats and species listed in Annex I and II of the Habitats Directive and Annex I of the Birds Directive. This vast expanse accounts for over 35% of Malta’s national territory and encompasses the Fisheries Management Zone, defined by a 25 nautical mile (46.3 kilometers) boundary under the Territorial Waters and Contiguous Zone Act (Cap 226). To achieve these conservation goals, Malta has designated eighteen Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) under the framework of the Flora, Fauna, and Natural Habitats Protection Regulations (S.L. 549.44). These MPAs play a pivotal role in achieving a favourable conservation status (FCS) for marine habitats and species, as well as in safeguarding seabird populations. Notably, Malta boasts five coastal Special Areas of Conservation, denoted as MT0000101 to MT0000105 (

Figure 1).

This study focused on MPA MT0000101 (hereafter referred to as MT101 for brevity), which has four habitats falling under Article 17 of the Habitats Directive [

14]. The habitats include sandbanks (1110), which 3 are consistently covered by seawater;

Posidonia oceanica beds (1120), which are designated with ‘Priority’ status under the Habitats Directive; reefs (1170); and submerged or partially submerged sea caves (8330). This is the only other MPA hosting all four habitats, with the other being MT0000105, which is already heavily studied [

15]. While a full map is not reproduced here due to space and formatting constraints, habitat coverage is summarized in Figure A in Supplementary Material). MT101 encompasses the area between Rdum Majjiesa and Għar Lapsi, including the hotspots Għar Lapsi and Ġnejna. These selected areas are valuable focal points for this research, owing to their ecological significance and susceptibility to human pressures.

The western coastline of Malta where MT101 is located is characterised by a series of prominent bays and headlands. Golden Bay and Għajn Tuffieħa Bay are sandy beaches popular with recreational users, while Fomm ir-Riħ is a more remote bay enclosed by cliffs. The nearest small harbour is located at Ġnejna, which is used by artisanal fishers, while larger commercial harbours such as Marsaxlokk and the Grand Harbour lie outside the study area on the eastern side of Malta. These coastal indentations are frequented by a variety of vessels, including small-scale fishing boats, passenger craft, and pleasure boats during summer months, while larger vessels such as tankers and cargo ships typically transit offshore along established routes parallel to the island’s western coastline.

The management of MPAs in the Maltese Islands is primarily aimed at enhancing or maximising their contribution to the Favourable Conservation Status (FCS) of habitats and species listed in the EU Habitats Directive, as well as the protection of seabirds in line with the Birds Directive [

13]. The EU Habitats Directive (Article 6) requires conservation measures and management plans tailored to the ecological needs of listed habitats and species [

16]. The management and assessment requirements stipulated by Article 6 also extend to SPAs designated under the Birds Directive, as per Article 7 of the EU Habitats Directive. Operational and site-specific conservation measures are also identified to address threats and knowledge gaps, forming part of Malta’s national management framework for marine Natura 2000 areas [

17].

While the directives provide a clear legal mandate, the practical implementation of these management strategies often face challenges such as limited resources, stakeholder conflicts, and the need for adaptive management. A robust management strategy based on continuously evaluated impact assessments is vital for biodiversity preservation and sustainability. Additionally. a targeted approach of such assessments not only contribute to advancing our understanding of marine conservation but also offer practical solutions to mitigate the effects of specific human activities on the marine biodiversity of the Maltese Islands

This investigation centres on evaluating the impacts of selected human activities, i.e., the operations of passenger, cargo, fishing, tanker, tug, and towing vessels, on MT101. These activities constitute substantial aspects of human interaction with the marine environment in the Maltese Islands and present distinct challenges to the stewardship and preservation of these vital areas.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data Acquisition

The study relied on a comprehensive dataset sourced from the European Marine Observation and Data Network (EMODnet), focusing specifically on the Human Activities theme. It analyzes five distinct vessel densities, each representing various human pressures: cargo, tug & tow, tanker, passenger, and fishing vessels. It is important to note that the dataset does not include pleasure craft or small-scale fishing vessels (< 15 m), which are generally not equipped with AIS and therefore remain outside the scope of this analysis.

Density maps were generated from ship reporting data of the Automatic Identification System (AIS).The Automatic Identification System (AIS) is a vessel-tracking technology mandated by the International Maritime Organization (IMO) for larger vessels and adopted locally through Transport Malta regulations in 2012. It uses VHF radio and satellite signals to broadcast each vessel’s identity, type, position, speed, and course at regular intervals. These data are received by coastal stations and satellites, compiled into international databases such as EMODnet, and provide a reliable means of mapping vessel traffic intensity across spatial and temporal scales. In this study, AIS data were used to calculate vessel density for different categories of vessels between 2017 and 2022.

Through the adoption of local legislation, the Vessel Traffic Monitoring and Reporting Regulations (S.L. 499.34), all fishing vessels with a length of over 15 metres operating within Maltese internal and territorial waters or visiting local ports are mandated to be equipped with an AIS (Class A). The implementation deadlines for compliance were staggered between 2012 and 2014. Fishing vessels falling within specific length categories were required to adhere to these deadlines: those with an overall length of 24 meters and above but less than 45 meters, those with a length of 18 meters and above but less than 24 meters, and those exceeding 15 meters but less than 18 meters. Additionally, newly built fishing vessels exceeding 15 meters have been subject to the AIS requirement since 30th November 2010 [

17].

Vessel density was calculated for each year between 2017 and 2022, and then averaged across the entire study period. Following the EMODnet approach, vessel trajectories were matched with 1 km x1 km grid cells in a PostgreSQL/PostGIS database. A spatial index was created to improve processing speed, and density values were expressed as hours per km² per month. These were later rescaled to 10x10 m cells to allow finer spatial analysis. This refinement ensured that small but ecologically significant features, such as Posidonia meadows, are represented accurately despite the coarse source grid.

Subsequently, spatial analysis was conducted using PostGIS’s st_intersection function to determine the grid cells crossed by each vessel trajectory line. Following this, segment length and time were calculated using st_length and a custom formula, respectively, considering the length of each segment and the total time of the vessel trajectory [

15]. The resulting density values, expressed in hours per square kilometre per month, were computed by summing the segment times within each grid square. These values were then integrated into the 1 km x1 km grid, forming a new grid table. Ultimately, this methodology provided insights into maritime activity patterns, crucial for understanding and managing marine environments effectively.

Given Malta’s limited landmass and the relatively small area of interest totalling 14.6 square kilometres, acquiring comprehensive data posed a significant challenge, resulting in sparse and sizable datasets. Consequently, to enhance data comprehensibility and analysis, the retrieved data from EMODnet underwent a transformation. Specifically, the grid cells were rescaled from 1000 meters by 1000 meters to 10 meters by 10 meters, thereby facilitating a clearer understanding of the data.

This refinement was necessary because the ecological features of interest, such as seagrass meadows, reef outcrops, and submerged sea cave, occur at scales much finer than 1x1km. A 1x1 km resolution risked masking important patterns of overlap between vessel activity and sensitive habitats, particularly in nearshore areas where the interaction between human use and ecological systems may be more concentrated. The rescaling to 10x10 m better captures the spatial scale of these habitats’ sensitivity and hence produces results that are more relevant for site-level management and policy implementation.

The additional dataset, encompassing the four habitats falling under Annex 1 of the Habitats Directive, was sourced from the European Environment Information and Observation Network (EIONET) website. This platform hosts a Central Data Repository, an integral component of the Reportnet architecture. Functioning akin to a comprehensive bookshelf, the Central Data Repository contains environment-related data reports submitted to international recipients. Each country maintains its collection of deliveries within this repository or directs to a preferred alternative repository.

Notably, Malta, as a member of the European Economic Area (EEA) who adheres to the Habitats Directive, possesses its dedicated folder within this repository. This folder houses pertinent data reports, organised according to relevant reporting obligations or agreements. Specifically, under the Habitats Directive, Malta is obliged to submit reports, including the latest iteration published in 2019 [

18]. Article 17 mandates Member States to submit reports every six years, detailing the advancements in implementing the Habitats Directive, with the upcoming report scheduled for publication in 2025. Central to the directive’s objectives is the preservation or reinstatement of a favourable conservation status for habitat types and species of community interest. Consequently, monitoring and reporting efforts under the directive are primarily geared towards this aim.

3.2. Data Integration in Spatial Output

The collected data underwent thorough processing to ensure reliability and compatibility. This involved merging shipping density data for various vessel categories—cargo, fishing, passenger, tanker, and tug and tow vessels—with spatial data delineating the boundaries of the selected Maltese Marine Protected Area (MPA). Additionally, to offer a comprehensive view of the marine ecosystem, habitat data specific to MT101 were incorporated. These habitat datasets, which included sandbanks (1110), Posidonia oceanica beds (1120), reefs (1170), and submerged or partially submerged sea caves (8330) in accordance with Annex I to the Habitats Directive, were sourced from EIONET.

A key component of the methodology involved geospatial analysis, conducted primarily using Quantum Geographic Information System (QGIS) software. Through this analytical framework, vessel route data were overlaid onto the spatial extent of the designated MPAs. This process facilitated the visualization and integration of spatial patterns and densities of maritime activities in relation with vessels within the study area. By juxtaposing vessel routes with MPA boundaries, the study aimed to delineate areas of potential conflict and pressure on the marine environment. To quantify the intensity of vessel-related maritime activities within MT101, route density metrics were calculated for each vessel category. For each vessel type, route density within the MPAs was calculated. This involved determining the maximum vessel density for each type and normalizing the data to ensure comparability. The raster calculator tool in QGIS was employed nr this purpose, scaling the route density values between 0 (no activity) and 1 (maximum observed activity).

3.3. Cumulative Impact Assessment

Another important aspect of the methodology was the evaluation of cumulative impacts resulting from maritime activities within the MPA. To achieve this, the normalised density values for each vessel category were aggregated to yield a composite measure of overall impact. This cumulative impact assessment aimed to provide a comprehensive understanding of the collective vessel-related pressures exerted by shipping activities on the marine ecosystem within MT101. Potential impact scores, ranging from 0 to 5, were assigned based on the intensity and spatial distribution of maritime activities, thereby informing subsequent management recommendations. It is worth noting that the maximum impact score varied depending on the maximum density of the particular vessel category. For instance, for passenger vessels, the maximum impact score was 1.49, resulting in a range from 0 to 2 instead of 0 to 5. This adjustment was made to prevent skewing the actual impact of vessel density on the MPA.

Values for vessel density will be expressed as hours per km2 per month in the text and tables of following sections. However, for visualization, vessel densities were normalized into relative classes (low–high) rather than mapped on an absolute scale. This approach allows comparability across vessel categories, whose absolute activity levels differ by orders of magnitude (e.g., cargo vs. passenger vessels). While absolute values (hours/km²/month) are reported in the text and tables, the use of relative scales in maps provides a consistent basis to identify spatial hotspots of vessel presence across all categories. White areas indicate no recorded density, while light blue denotes the lowest density class.

Through the use of GIS mapping techniques and comprehensive data from EMODnet, this method provided a robust framework for analyzing the impact of maritime activities on the selected MPA in Malta and helps to identify key areas of conflict and pressure within the MPAs. The findings from this analysis formed the basis for developing tailored and cost-effective management recommendations, aiming to mitigate the identified vessel-related pressures and enhance the conservation effectiveness of these crucial marine environments.

4. Results

The study yielded several significant spatial outputs that provide valuable insights about the interactions between maritime activities in Maltese protected waters and habitat conservation within the studied MPA, thereby facilitating informed decision-making for sustainable marine management practices. These maps were overlaid with selected habitat types, comprising sandbanks, Posidonia oceanica beds, reefs, and submerged or partially submerged sea caves. The resulting analysis delivered the following outcomes:

Maps illustrating the degree of overlap between each habitat code and the combined annual average densities for each shipping category;

Maps depicting the combined habitat codes and combined annual averages for each shipping category; and

A map showcasing the combined habitat codes and combined annual averages for all shipping categories. These outputs provide valuable insights into the interactions between maritime activities and habitat conservation within the studied MPA, thereby facilitating informed decision-making for sustainable marine management practices.

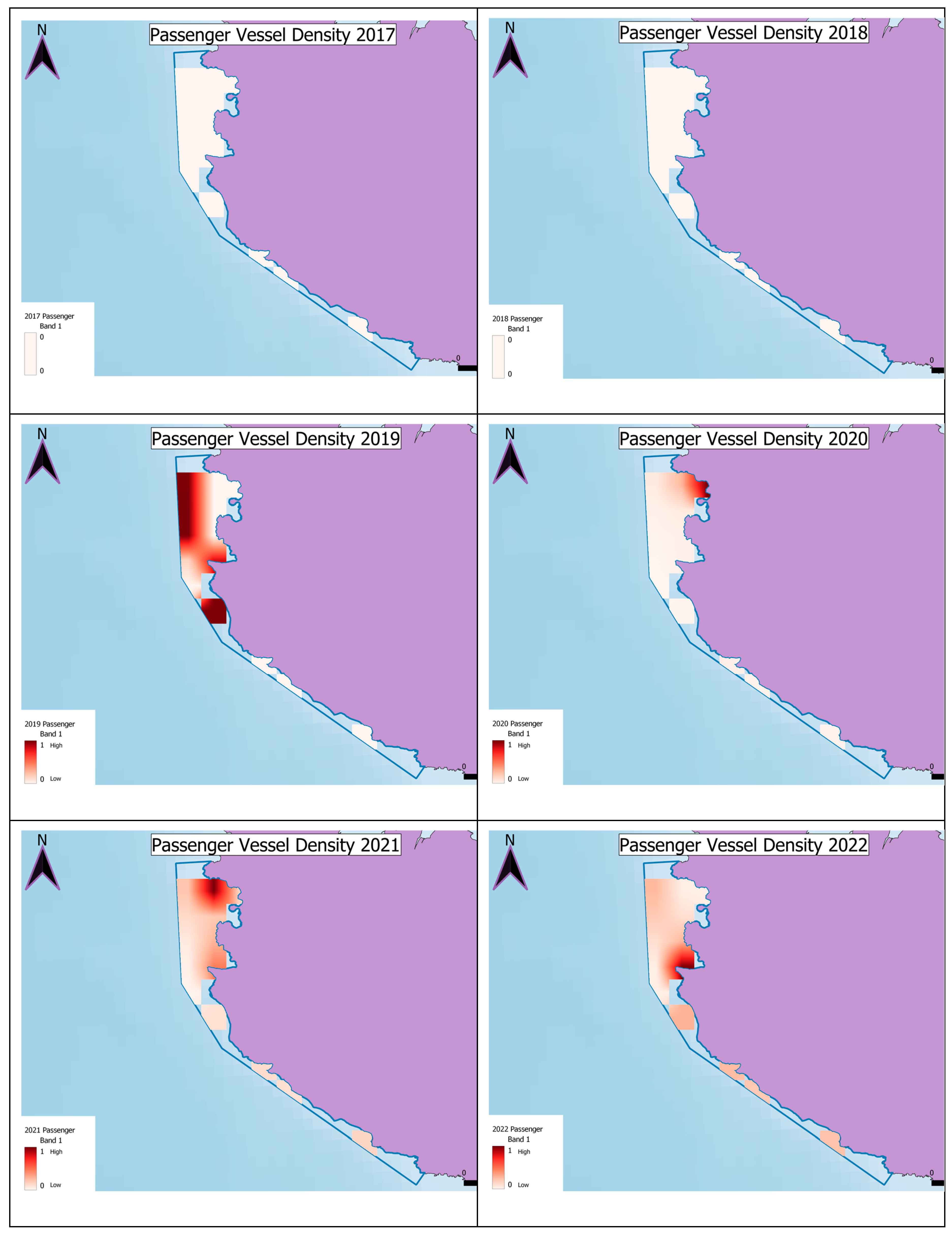

4.1. Annual Trends of Passenger Vessel Density: 2017 to 2022

All passenger ships, regardless of size, are mandated to be equipped with an Automatic Identification System (AIS) in accordance with SOLAS regulation V/19.2.4, aligning with the recommendations endorsed by the International Maritime Organization. These vessel types fall within the ship type codes from 60 to 69 in the AIS data. Over the six-year period, there has been a notable increase in passenger vessels, transitioning from negligible vessel density in 2017 and 2018, where it was recorded as zero, to a significant surge in passenger vessels, particularly evident in the Golden Bay and Fomm ir-Riħ areas. The passenger vessels depicted in the generated maps (

Figure 2) encompass a variety of types, including passenger ships, inland passenger ships, inland ferries, ferries, ro-ro/passenger ships, accommodation ships, accommodation barges, accommodation jack-ups, accommodation vessels, passenger landing crafts, accommodation platforms, air cushion passenger ships, and air cushion ro-ro/passenger ships [

18].

Each year exhibited varying maximum values for vessel density. Specifically, in 2017 and 2018, the maximum density was recorded as 0, while in 2019, it reached 0.005. Subsequently, in 2020, the maximum density peaked at 2.57, followed by 1.2 in 2021, and 2.29 in 2022. These maximum values were utilised to normalise the data, ensuring that all values fell within the range of 0 to 1. This step was crucial in obtaining a clear representation of the fluctuation in passenger vessel density within the area, aiding in the interpretation of the maps presented in

Figure 2.

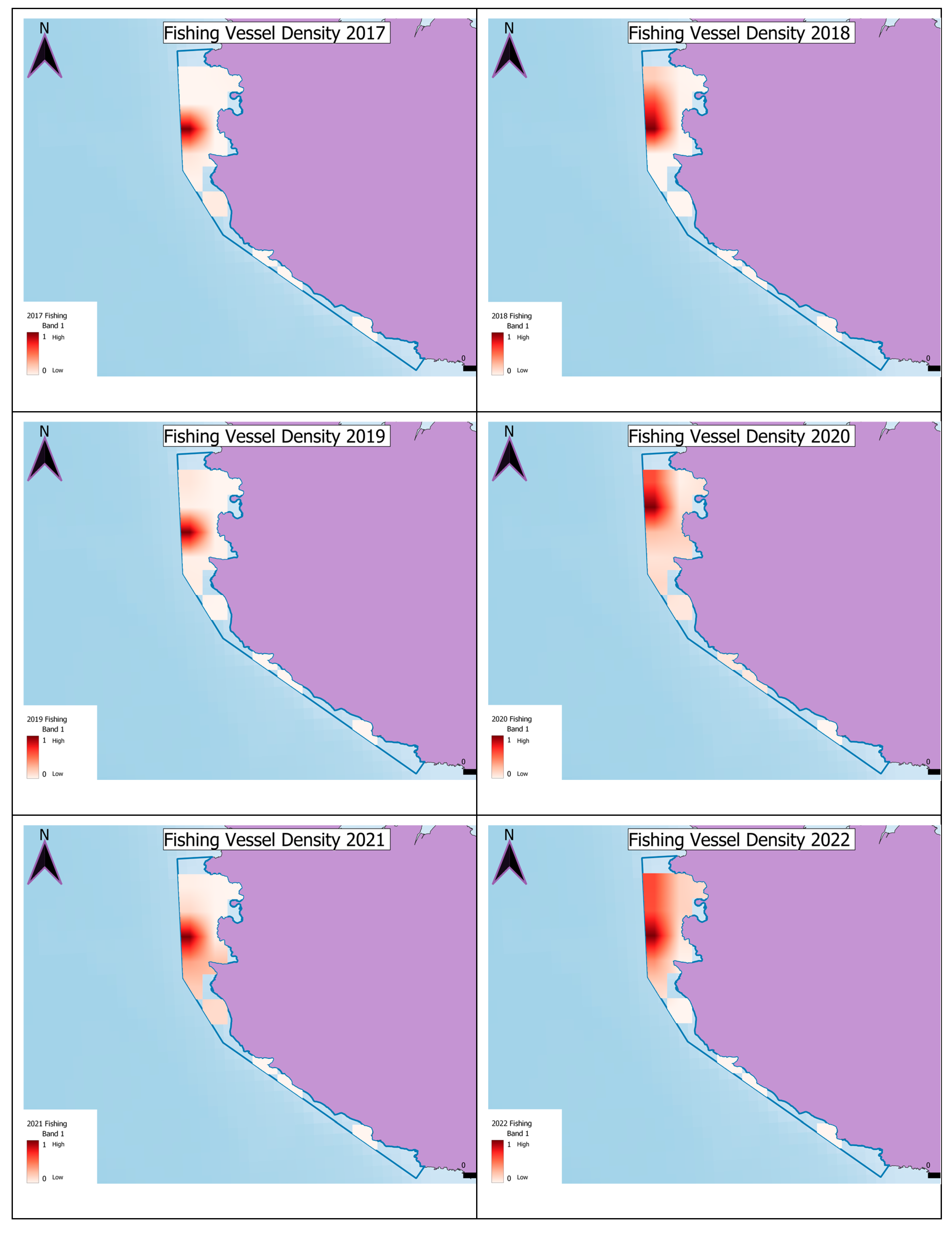

4.2. Annual Trends of Fishing Vessel Density: 2017-2022

It is mandatory for fishing vessels equipped with AIS to maintain its operational status at all times. Only, in exceptional circumstances, the vessel’s master may switch off the AIS if deemed necessary for safety or security reasons. While AIS transmission is legally mandatory for fishing vessels ≥15 m in Malta, we acknowledge that non-compliance and deliberate deactivation have been reported in fisheries globally. Our analysis is therefore constrained to recorded AIS signals and should be considered a conservative representation of fishing activity. It is important to note that, despite this potential limitation, EMODnet dataset offers comprehensive fishing vessel density data. All fishing vessels meeting the aforementioned criteria are categorised under a single ship type code in the AIS data, namely code 30, encompassing various types of fishing vessels [

18]. Over the selected years, a significant portion of fishing activity has been concentrated in the offshore Ġnejna area. The density of fishing vessels has dispersed and intensified around this hotspot area in comparison to other regions (

Figure 3).

The fishing vessels depicted in the generated maps represent a variety of types, including fishing vessels, trawlers, fishery protection/research vessels, fish carriers, fish factories, factory trawlers, fish storage barges, fishery research vessels, fishery patrol vessels, and fishery support vessels [

8]. Each year exhibited varying maximum values for vessel density. For the fishing vessels the maximum values are outlined in

Table 1.

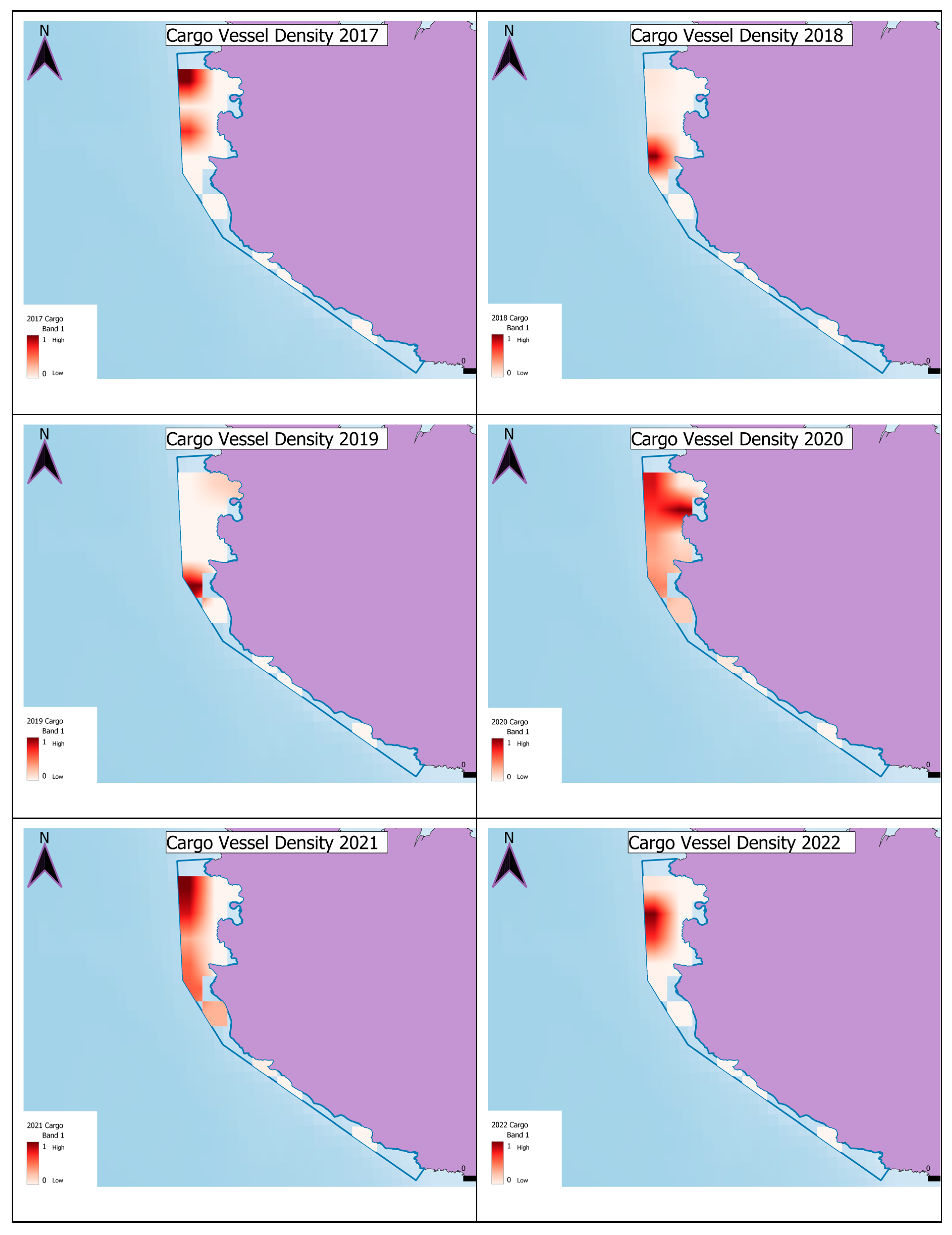

4.3. Annual Trends of Cargo Vessel Density: 2017-2022

The distribution of the cargo vessel density exhibited considerable variability throughout the years, with the location of the highest concentration as changing annually. In addition, the highest values of cargo vessel density declined overall, with 2017 recording the highest value of 1.76, decreasing to 0.33 in 2022 (Table 2). These marked inter-annual differences might be explained in terms of inter-annual differences in wind conditions, given that the MPA in question is exposed to the prevailing NW wind, rendering it untenable for anchoring during strong NW episodes and possibly in terms of inter-annual variability in shipping traffic trends and flows as well.

Under the AIS ship type code 70, various vessel types are listed, including passenger/cargo ships, livestock carriers, bulk carriers, ore carriers, general cargo vessels, wood chip carriers, container ships, ro-ro cargo vessels, reefers, heavy load carriers, barges, ro-ro/container carriers, inland cargo vessels, cement carriers, reefer/container ships, vegetable/animal oil tankers, obo carriers, vehicle carriers, inland ro-ro cargo ships, rail/vehicle carriers, pallet carriers, cargo barges, hopper barges, deck cargo ships, cargo/container ships, aggregates carriers, limestone carriers, ore/oil carriers, self-discharging bulk carriers, deck cargo pontoons, bulk carriers with vehicle decks, pipe carriers, cement barges, stone carriers, bulk storage barges, aggregates barges, timber carriers, bulkers, trans-shipment barges, powder carriers, CABU carriers, and vehicle carriers [

19]. While not all of these vessel types may pass through the chosen area of study, they are included in the EMODnet database, which was utilised to generate the maps presented in

Figure 4.

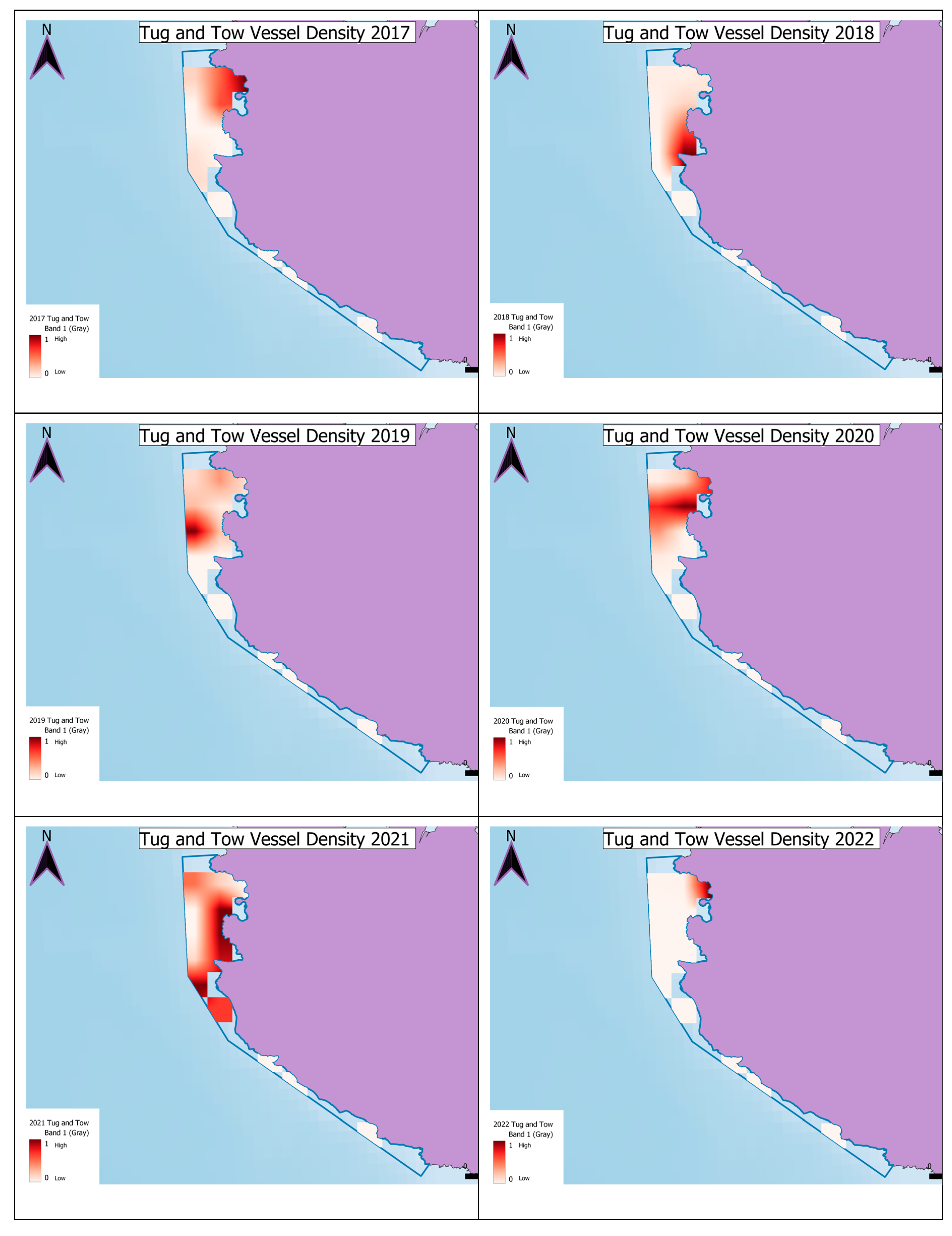

4.4. Annual Trends of Tug and Tow Vessel Density: 2017-2022

Similar to cargo vessels, the distribution of tug and tow vessel density exhibited inconsistency throughout the years, with the highest point of concentration changing annually (

Figure 5). Notably, there was an outlier in 2019, where the maximum value reached 2.56, whereas in other years, it remained below 0.7, as illustrated in

Table 1.

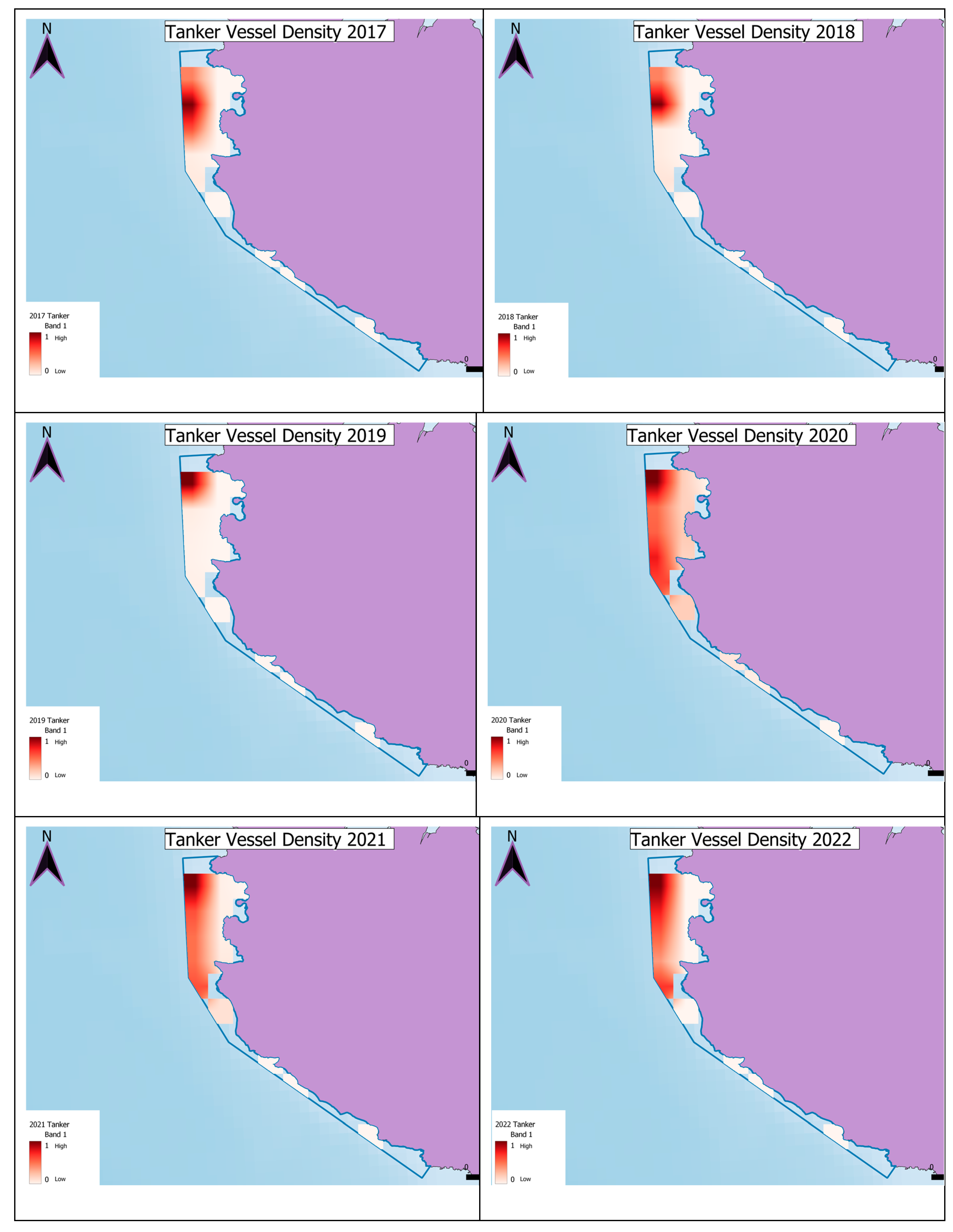

4.5. Annual Trends of Tanker Vessel Density: 2017-2022

Tanker vessels consistently exhibit high pressure in the same area, notably near Ras il-Waħx, throughout the years. However, there has been a decline in intensity over time, with 2017 and 2018 recording the highest values and a significant exponential decrease observed by 2022, where the density decreased to 0.12 (

Table 1).

Figure 6.

Tanker vessel density in MPA MT101 between 2017 and 2022.

Figure 6.

Tanker vessel density in MPA MT101 between 2017 and 2022.

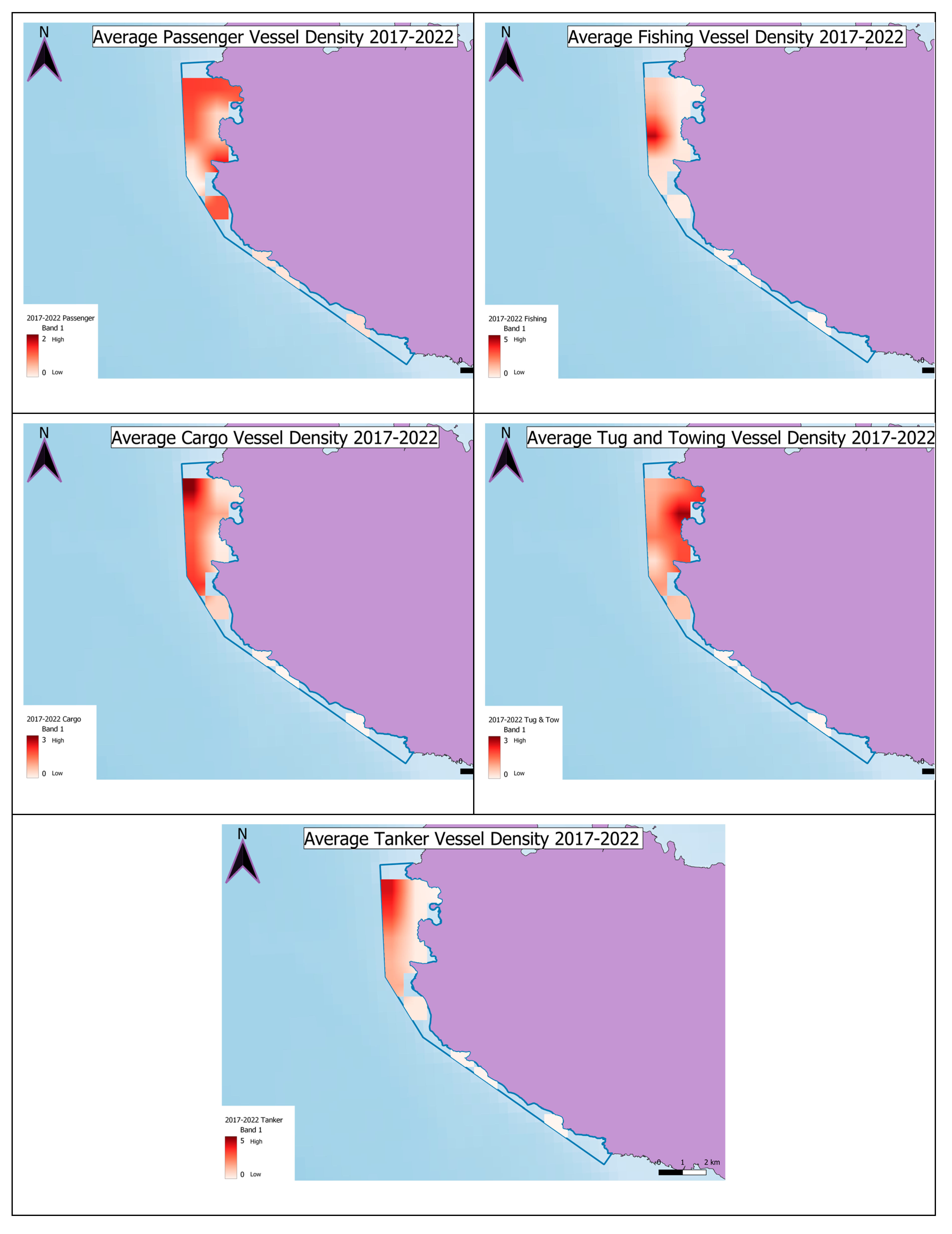

4.6. Average Vessel Density: 2017 to 2022

This section presents maps depicting the average vessel density across all years combined (2017 to 2022). It is important to note that not all vessel types share the same density range, as their maximum values vary. To ensure clarity, the maximum value for the range was determined as the next whole number from the highest recorded density value for each vessel, with the maximum set at 5. The findings from this mapping analysis are mainly the following:

Passenger Vessels: The average passenger vessel density across the SW MPA exhibited notable concentrations, particularly in bay areas such as Golden Bay, Għajn Tuffieħa Bay, and Fomm ir-Riħ, throughout the years from 2017 to 2022. The density ranged between 0 and 2, with the highest recorded value reaching 1.49.

Fishing Vessels: The average fishing vessel density within the study site demonstrated a consistent concentration, particularly in the offshore Ġnejna area, as depicted in the preceding maps. This hotspot remained prominent across all years, portraying a stable pattern evident in

Figure 7. The density of fishing vessels intensified around this area from 2017 to 2022, with values ranging between 0 and 5. Notably, the highest recorded density reached 4.42.

Cargo Vessels: The average cargo vessel density exhibited a notable concentration near Ras il-Waħx area, primarily located further out from the bays, as illustrated in

Figure 7. The average density ranged between 0 and 3, with the highest recorded density reaching 2.9.

Tug and towing vessels: a significant concentration was observed near the Ras il-Pellegrin area, gradually dispersing, particularly towards Golden Bay and Għajn Tuffieħa Bay, as depicted in

Figure 7. Similar to the average cargo vessel density, the tug and towing vessel density ranged between 0 and 3, with the highest recorded density reaching 2.82.

Tanker vessels: a significant concentration was particularly detected near Ras il-Waħx. The tanker vessel density ranged between 0 and 5, with the highest recorded density reaching 4.06.

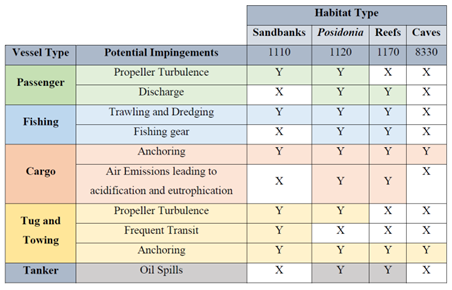

4.7. Vessel Density Overlap with Habitat

In this section the overlap between vessel density by category and the four designated habitat types - reefs, submerged or partially submerged sea caves, sandbanks and Posidonia oceanica beds - within MPA MT101 was examined. The analysis aims to elucidate the spatial relationship between marine habitats and vessel activity, providing insights crucial for informed management strategies within the MPA.

Passenger vessels have demonstrated significant impacts across all habitat types, with reefs being notably affected due to its extensive coverage area. Conversely, the habitat of submerged or partially submerged sea caves experienced comparatively lesser effects, attributed to its smaller spatial extent and lower vessel density. Fishing vessels have generally exhibited a low impact across all habitat types, with particularly minimal effects observed in sandbanks and sea caves. However, Posidonia oceanica beds and reefs have experienced more significant impacts, with approximately half of the habitat area being notably affected by fishing vessel activity.

Cargo vessels, similar to fishing vessels, have generally had a limited impact across all habitat types. Minimal effects were noted in sandbanks and sea caves. However, Posidonia oceanica beds and reefs exhibited more significant impacts, with approximately half of the habitat area being notably affected by cargo vessel activity.

Tug and towing vessels have shown significant impacts across all habitat types with variations in the extent of coverage overlapping with the vessels. Among the habitat types, submerged or partially submerged sea caves exhibited the least coverage, likely due to the proximity of sea caves to the shoreline.

Tanker vessels have exhibited a limited impact across in sandbanks, and submerged or partially submerged sea caves. However, Posidonia oceanica beds and reefs experienced more significant impacts, with approximately half of their area notably affected by tanker vessel activity. When considering all four habitats per each vessel density for the whole study period, the findings can be synthesized as follows:

The impact of passenger vessels is predominantly evident across all habitat types, as depicted in

Figure 8. However, minimal effects were observed along the southern coast of Malta, where reefs and sea caves are situated.

Fishing vessels exhibit the highest impact near the border of the MPA, particularly parallel to Ras il-Pellegrin, with their intensity gradually dispersing to a medium level along the MPA border and diminishing to lower impact levels closer to the bays.

The impact of cargo vessels is most pronounced along the MPA’s border, particularly parallel to Ras il-Waħx. This impact gradually diminishes from high to medium intensity along the MPA’s border and decreases to lower levels within the bays and along the southern coast (

Figure 8).

The effect of tug and towing vessels is pronounced across all habitats, with the highest intensity of impact concentrated near Ras il-Pellegrin, extending with varying degrees of intensity into the bays and along the MPA border. This impact gradually diminishes to a lower intensity along the southern coast.

The impact of tanker vessels on all the habitats is varied across the MPA. The highest intensity of impact is concentrated along the MPA border, stretching between Ras il-Waħx and Ras il-Pellegrin, and gradually diminishing to a lower intensity within the bays and along the southern coast.

A final map,

Figure 8, was generated to illustrate the combined habitat types overlaid with the combined annual averages for all shipping categories. When overlaying the average vessels densities of the five different vessel types, the range falls between 0 and 10, with the highest recorded density reaching 9.47. The highest intensity of vessel impact on all habitats is observed along the MPA border on the west side, gradually decreasing to a medium impact as it approaches the bays. A low impact is noted on the southern coastline, likely due to fewer vessel activities in the vicinity of the area where the four habitats are located (

Figure 8).

5. Discussion

5.1. Key Findings of Results

The designation of MPA MT101 in 2006, followed by its update in 2018, represented a significant milestone in conservation efforts, covering an expansive area of 1459.6 hectares [

20]. Situated between Rdum Majjiesa and Għar Lapsi, this region holds profound ecological importance owing to its rich and diverse biota, complemented by distinctive geomorphological features. Notably, the site hosts representatives of the main marine habitat types found in the Maltese Islands, harbouring species and ecosystems of conservation significance [

21]. Large expanses of seabed are dominated by meadows of the seagrass

Posidonia oceanica within the 50-metre bathymetric region, while coastal reefs support a diverse array of marine life, including sponges, cnidarians, polychaetes, molluscs, crustaceans, and echinoderms. However, it is important to note that despite efforts, the conservation status of the four habitat types within the site remains good but not excellent, indicating the need for continued conservation efforts [

22].

Passenger vessels demonstrated consistent high impact, particularly along the bay areas such as Golden Bay, Għajn Tuffieħa Bay, and Fomm ir-Riħ. Fishing vessels exhibited a dispersed yet intensified presence, with a hotspot identified offshore in the Ġnejna bay area. Cargo vessels and tanker vessels, on the other hand, displayed varying degrees of impact, with concentrations observed near Ras il-Waħx. Tug and towing vessels demonstrated a widespread impact across all habitat types, with high intensity noted along Ras il-Pellegrin. Conversely, tanker vessels showed a limited impact across habitats, with higher intensities concentrated along the MPA border. This is clearly displayed in Table 2 denoting the impact (High, Medium or Low) of each vessel on each of the four habitat types.

The observed overlap between high vessel density and sensitive habitats suggests potential pathways of ecological impact within MT101. For instance, repeated anchoring in Posidonia oceanica meadows can fragment seagrass beds and reduce primary productivity. Similarly, increased vessel-induced turbidity and sediment resuspension can affect benthic communities. Persistent vessel noise and pollution may further stress sensitive species, potentially altering community composition. While this study does not directly quantify ecological outcomes, integrating vessel pressure hotspots with established knowledge of habitat vulnerability provides an indicative framework for understanding the mechanisms through which human activities can affect biodiversity loss and habitat degradation in MPAs.

While the presented absolute vessel density values may appear small, it is important to note that these represent monthly averages per square kilometer. When scaled to smaller habitat patches, these pressures translate into significant cumulative exposure. Similarly, interannual variability in hotspot locations reflects dynamic maritime use patterns, such as seasonal tourism peaks and ferry route adjustments, rather than inconsistencies in the methodology that was adopted.

The results highlight the complex interactions between vessel activities and marine habitats in MT101. Mapping both the distribution and intensity of traffic provides a clearer basis for marine spatial planning and targeted conservation measures. The cumulative density analysis highlights zones of high vessel activity that overlap with sensitive habitats. While the ecological consequences of this overlap are not empirically measured in this study, previous research suggests that such exposure often correlates with physical disturbance, pollution, or habitat degradation [

23,

24,

25].

Table 3. Impingements on habitats from each vessel (2017-2022), with codes corresponding as follows: sandbanks (1110), Posidonia oceanica beds (1120), reefs (1170); and sea caves (8330).

Table 3 provides a detailed overview of presence and potential impacts of various vessel types on the four selected habitats within the study area. Each habitat is evaluated for susceptibility to different impacts, with ‘Y’ indicating potential impact and ‘X’ denoting unlikely impact. This table provides valuable insights into habitat-vessel interactions, aiding in the development of mitigation strategies. Furthermore, it validates the findings of this study, aligning with the classification of vessel impacts on habitat types as high or medium, as indicated in

Table 3.

5.2. MPA Effectiveness: Recommendations of Mitigation Measures

The management of MT101 as an MPA is framed by its status as a Natura2000 site MT101 and hence covered by formal conservation objectives and measures under the Natura 2000 framework. However, the site still faces limitations typical of under-resourced MPAs, including restricted enforcement capacity and competing stakeholder interests. These challenges underline the importance of linking cumulative pressure assessments, such as those presented here, to practical enforcement and adaptive management in order to move MT101 beyond nominal protection and towards ecological effectiveness. Drawing upon the findings of this study, the following high-level mitigation measures could enhance the effectiveness of MT101 as a managed MPA:

Enhanced enforcement of Marine Protected Area (MPA) Regulations: Strengthening enforcement efforts within the existing MPA would ensure compliance with regulations governing vessel activities near sensitive habitat areas as is being done in other countries such as Canada [

26]. Additionally, the increase patrols and surveillance would deter illegal activities and enforce speed limits, no-anchor zones, and other protective measures [

27].

Habitat-specific management strategies: Such strategies would be required in order to develop tailored management practices for each habitat type, focusing on minimizing vessel impacts on reefs,

Posidonia oceanica meadows, submerged sea caves, and sandbanks. Implementing habitat-specific regulations, such as seasonal restrictions or temporary closures, would facilitate the protection of vulnerable habitats during critical life stages or sensitive periods [

28].

Collaborative stakeholder engagement: Fostering more collaboration between government agencies, local communities, marine industries, and conservation organisations would lead to better development and implementation of effective conservation measures [

29]. Randone and others (2019) also state that stakeholders should be engaged in participatory decision-making processes to ensure that mitigation measures are practical, feasible, and culturally sensitive.

Research and monitoring programs: Allocation of resources for ongoing research and monitoring programs would assess the effectiveness of mitigation measures and track changes in habitat condition and vessel impacts over time [

30]. Use scientific data and evidence to inform adaptive management strategies and refine conservation efforts based on empirical findings [

28].

5.3. Other Mitigation Measures: Recommendations According to Vessel Type

Beyond the general mitigation measures, outlined in

Section 5.2, more specific measures are necessary to address specific impacts by different vessel types. Malta is already implementing its own measures and plans to have better mitigation measures put in place for all MPAs, such as the recent formalized conservation objectives and measures for all its marine Natura 2000 sites, and aligning with the EU Habitats and Birds Directives. The measures address various pressures, such as overfishing, marine litter, and habitat degradation, and include actions like regulating human activities, enhancing enforcement, and conducting targeted research to fill knowledge gaps [

31].

The following section provides more tailored measures for each vessel type and relate impacts in the context of the SW MPA, MT101:

Passenger Vessels: Passenger vessels exert significant pressure on marine habitats through multiple pathways. Propeller turbulence disrupts sediments and seagrass beds, compromising the stability of sandbanks and seagrass ecosystems. Additionally, the discharge of sewage and pollutants from these vessels deteriorates water quality, posing severe risks to sensitive marine life such as corals and seagrasses. To mitigate these impacts, measures include enforcing speed limits and designating no-anchor zones in ecologically sensitive areas to minimise propeller wash and anchor damage; installing waste management systems on vessels to prevent pollution discharge; and raising awareness among passengers and crew about the importance of marine conservation, promoting responsible behaviour such as avoiding littering and wildlife disturbance.

Fishing Vessels: Fishing vessel operations pose substantial threats to marine habitats, particularly through bottom trawling and dredging, which physically damage benthic ecosystems like reefs and destabilize sediments, especially around sandbanks. More importantly, the capture of target species through fishing activities alters population structures and disrupts trophic dynamics, thereby compromising the overall functioning of marine ecosystems. These activities also result in bycatch and discards—the unintentional capture and release of non-target species—which can disrupt food webs and nutrient cycles. Additionally, gear such as gillnets and traps can entangle vulnerable species, including corals and seagrasses. To mitigate these impacts, spatial and temporal fishing restrictions are enforced in sensitive habitats. The adoption of selective, low-impact fishing gear and bycatch reduction devices is encouraged to minimize ecological disturbance and species mortality. Furthermore, awareness campaigns and increased surveillance help ensure compliance with marine protected area (MPA) regulations.

Cargo vessels pose a significant threat to marine habitats through physical disturbance, pollution, and emissions. Anchoring and groundings can severely damage benthic ecosystems, particularly fragile reef areas. The release of ballast water and cargo residues increases the risk of introducing invasive species and pollutants, destabilizing marine ecosystems and causing habitat degradation. Additionally, emissions of sulphur dioxide and nitrogen oxides from cargo vessels contribute to coastal water acidification and eutrophication, endangering sensitive habitats like seagrass beds (Posidonia) and reefs. To mitigate these impacts, vessels should use designated anchorage areas equipped with mooring buoys, implement strict ballast water management practices, and comply with emission standards to reduce air pollution and protect coastal ecosystems.

Tug and towing vessels pose a risk to sensitive marine habitats primarily through the turbulence generated by their propeller wash, especially in shallow coastal areas where seagrass beds and coral reefs are located. Their frequent movement can lead to sediment resuspension and erosion, destabilising sandbanks and other coastal features. Anchoring and mooring activities in vulnerable zones further exacerbate habitat degradation by damaging benthic communities. To mitigate these impacts, it is essential to designate and clearly mark navigational channels that direct these vessels away from sensitive areas. Additionally, best operational practices—such as reducing speed in shallow waters and avoiding abrupt manoeuvres—should be enforced to minimise wake and propeller wash. Vessels should also be required to obtain permits and comply with stringent regulations governing anchoring and mooring within designated areas to safeguard vulnerable habitats from physical disturbance.

Tanker vessels pose considerable threats to marine habitats, primarily due to the risk of oil spills and pollution incidents. Accidental discharges can have devastating impacts on marine ecosystems, resulting in habitat degradation, water and sediment contamination, and long-lasting ecological harm to sensitive environments such as coral reefs and seagrass meadows. To date, there remains a lack of scientific studies directly assessing the impact of oil spills on Posidonia oceanica meadows, despite the ecological significance of these habitats. Key studies address their impacts on sandy beaches invertebrates or microbial communities [e.g., 32,33], economic repercussions, including extensive tourism and fishing losses and high remediation costs (which can often exceed the immediate ecological damage) [e.g 34].

To mitigate these risks, stringent safety measures should be enforced, including double-hull vessel designs and onboard oil spill response equipment. Additionally, tanker operators must adhere to mandatory oil spill contingency plans and emergency response protocols, especially when operating near vulnerable habitats. Regular inspections and maintenance of vessels are also essential to prevent leaks and spills caused by equipment failures or structural deficiencies.

The investigation of user-environment interactions within sea caves was limited due to challenges in directly assessing impacts from vessels. Consequently, further research is warranted to develop comprehensive decision support tools aligned with an ecosystem-based MSP, as mandated by the MSP directive. Future work could involve conducting in situ or field surveys to validate the mitigation measures suggested in this study.

It is important to acknowledge certain limitations in the datasets used. AIS data, while comprehensive for larger commercial and passenger vessels, underrepresents smaller recreational craft and artisanal fishing boats that may operate without AIS transponders. In addition, AIS reporting can be affected by seasonal patterns, such as peaks in tourism-related vessel activity during summer months, which may not be fully captured in annual averages.

On the ecological side, while EMODnet provides standardized habitat layers, the spatial accuracy of some habitat boundaries is constrained by survey coverage and resolution. These factors need to be better addressed in order to secure a higher precision in the alignment between vessel density and habitat extent. Recognizing these caveats is essential when interpreting the results and warrants the need for complementary field validation and higher-resolution ecological mapping in future work.

5.4. Limitations of AIS Data and Vessel Coverage

It is important to recognise the limitations of the AIS-based vessel data. While AIS provides comprehensive coverage for larger commercial, cargo, and passenger vessels, it underrepresents certain segments of maritime traffic. Many smaller vessels, particularly pleasure boats and small-scale fishing vessels under 15 m in length, do not carry AIS transponders and are therefore absent from the dataset used in this study. Moreover, AIS signals are subject to biases and gaps. For instance, some vessels may at times deactivate their AIS transmitters. These factors mean that the vessel densities and patterns reported in this study are conservative estimates of actual vessel presence and pressure within the MPA. Additionally, any observed interannual fluctuations should be interpreted with these limitations in mind, as year-to-year differences may partly reflect variations in AIS usage rather than purely changes in real vessel activity. These limitations underscores the need for complementary monitoring to fully capture the contributions of smaller vessels and to validate the AIS-derived insights.

Each identified component could benefit from individual assessment, particularly in areas where coarse resolution may not be suitable. Projects like the upcoming Corallo 2 project which started in January 2025, and further data from the EMODnet website could aid in achieving this.

6. Conclusion

The aim of this study was to formulate management recommendations aimed at mitigating the impact of vessel density and improving the efficacy of a Marine Protected Area (MPA) in conserving marine biodiversity. The findings of this study are particularly valuable given the scarcity of fine-scale, long-term vessel presence data in the Mediterranean. This objective was successfully met by employing spatial analysis to pinpoint areas of significant conflict and pressure within the chosen MPA. While this work presents MT101 as a Marine Protected Area, in line with EU Habitats Directive designation and national conservation objectives, it is important to recognise the disparity between its legal protection status and its practical use. In reality, the study has shown that the site is visited by a diverse array of vessels and this tension between the designation of MPAs and their on-the-ground management, puts into question whether such sites can truly be considered ‘protected’ when vehicle-related presence remains intense.

The findings underline the potential pressures associated with vessel activity on Malta’s marine habitats and reinforce the need for stronger spatial planning measures, as well as future ecological studies to directly quantify impacts. The originality of these data lies in their ability to reveal patterns that are otherwise inaccessible to managers and policymakers, offering an important foundation for site-level management and marine spatial planning. Notably, passenger vessels exhibit consistent high impacts along bay areas like Golden Bay and Għajn Tuffieħa Bay, while fishing vessels demonstrate dispersed yet intensified presence, particularly in the Ġnejna bay area. Cargo and tanker vessels display varying degrees of impact, with concentrations observed near specific zones, and tug and towing vessels exhibit widespread impact across all habitat types.

The potential impacts on the four key habitat types within the provide critical insights into the challenges faced by these sensitive ecosystems. While some habitats face higher risks of impingement from vessel activities, all habitats deserve equal protection as there might be other human pressures which negatively impact them.

To this end, a tailored set of management recommendations was developed, guided by the study’s findings, to effectively address vessel-related potential pressures within Maltese MPA. The analysis conducted within MPA MT101 sheds light on the dynamics between vessel activities and marine habitats, offering valuable insights for conservation and management strategies. MPA MT101 stands as a significant stronghold for marine conservation efforts in Malta, covering a substantial area known for its rich biodiversity and distinctive geomorphological features.

The mitigation measures proposed in this study offer promising avenues for addressing the identified challenges and minimizing the impacts of vessel activities on marine ecosystems. By enhancing enforcement of MPA regulations, implementing habitat-specific management strategies, fostering collaborative stakeholder engagement, and conducting ongoing research and monitoring programs, MPA MT101 has the potential to have better sustainable resource management and habitat conservation.

The cumulative density scores presented in this study provide a clear basis for prioritizing management actions. For example, high passenger vessel pressure around bay areas where Posidonia oceanica beds are present suggests that enforcing no-anchoring zones and regulating tourist vessel access should be an immediate priority. Similarly, the concentration of fishing vessels offshore of Ġnejna highlights the need for seasonal restrictions or gear limitations to protect adjacent reef habitats. Cargo and tanker vessel impacts, which are most pronounced near Ras il-Waħx, indicate that routing measures or designated anchoring areas would be effective in reducing cumulative pressure. Finally. tug and towing vessel activity, widespread across habitats, calls for operational guidelines such as reduced speeds in shallow areas.

By linking vessel-specific pressures to the vulnerable habitats most affected, these management measures can be phased and targeted according to ecological urgency, with Posidonia oceanica meadows and reefs representing the most critical priorities.

In conclusion, this study presents a preliminary assessment of MSP within the SW MPA, acknowledging certain assumptions regarding ecosystem and user conflicts and human pressures. By contributing to the body of knowledge informing decision-making processes related to marine spatial planning, conservation, and sustainable resource management within MPA MT101, this study underscores the importance of continued research and adaptive management strategies.

It is recommended that the study be repeated to assess annual habitat impacts, given the available data only extends to 2022. Furthermore, further research is needed to evaluate the effectiveness of proposed mitigation measures and refine management strategies accordingly. Collaboration with stakeholders and policymakers, along with benchmarking international best practices, will be pivotal for achieving long-term sustainability and ecological integrity within MPA MT101.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.D. and A.G.; methodology, A.D. and A.G.; software, A.D., A.G. and S.A.; validation, A.D., A.G. and S.A.; formal analysis, A.D. and A.G.; investigation, A.D. and A.G.; resources, A.D. and A.G.; data curation, A.D., A.G. and S.A.; writing—original draft preparation, S.A., A.D., R.G.; writing—review and editing, R.G, A.D. S.A and A.G.; visualization, S.A. and A.G.; supervision, A.D. and A.G.; project administration, A.D. and A.G.; funding acquisition, A.D. and A.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

No direct funding was provided. This work however benefitted from the data collected by the BIODIVALUE and the AMARE (Actions for Marine Protected Areas) projects, which was partly financed by the Interreg Italia-Malta 2007-2013 and Interreg MED Programme 2014–2020, respectively.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- OECD. Marine Protected Areas: Economics, Management and Effective Policy Mixes; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2017. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/environment/resources/Marine-Protected-Areas-Policy-Highlights.pdf (accessed on 29 May 2025).

- Gill, D.A.; Mascia, M.B.; Ahmadia, G.N.; Glew, L.; Lester, S.E.; Barnes, M.; Craigie, I.; Darling, E.S.; Free, C.M.; Geldmann, J.; Holst, S.; Jensen, O.P.; White, A.T.; Basurto, X.; Coad, L.; Gates, R.D.; Guannel, G.; Mumby, P.J.; Thomas, H.; Whitmee, S.; Woodley, S.; Fox, H.E. Capacity Shortfalls Hinder the Performance of Marine Protected Areas Globally. Nature 2017, 543, 665–669. [CrossRef]

- Environment and Resources Authority (ERA). Conservation Objectives and Measures for Malta’s Marine Natura 2000 Sites; Environment and Resources Authority (ERA), Government of Malta: Marsa, Malta, 2021. Available online: https://era.org.mt/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/MPA-Conservation-Objectives-Measures-2021-including-annex-Final_reduced-size.pdf (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2016; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2016.

- Rech, S.; Borrell, Y.; García-Vázquez, E. Marine Litter as a Vector for Non-Native Species: What We Need to Know. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2016, 113, 40–43. [CrossRef]

- Occhipinti-Ambrogi, A.; Savini, D. Biological Invasions as a Component of Global Change in Stressed Marine Ecosystems. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2003, 46, 542–551. [CrossRef]

- Gennaro, P.; Piazzi, L.; Persia, E.; Porrello, S. Nutrient Exploitation and Competition Strategies of the Invasive Seaweed Caulerpa cylindracea. Eur. J. Phycol. 2015, 50, 384–394. [CrossRef]

- Tempesti, J.; Mangano, M.C.; Langeneck, J.; Lardicci, C.; Maltagliati, F.; Castelli, A. Non-Indigenous Species in Mediterranean Ports: A Knowledge Baseline. Mar. Environ. Res. 2020, 161, 105056. [CrossRef]

- UNEP/MAP. Marine Litter Assessment in the Mediterranean; UNEP/MAP: Nairobi, Kenya, 2015.

- Coll, M.; Piroddi, C.; Steenbeek, J.; Kaschner, K.; Lasram, F.B.R.; Aguzzi, J.; Ballesteros, E.; Bianchi, C.N.; Corbera, J.; Dailianis, T.; et al. The Biodiversity of the Mediterranean Sea: Estimates, Patterns, and Threats. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e11842. [CrossRef]

- Di Bona, G.; Gancitano, V.; Fiorentino, F.; Garofalo, G.; Micalizzi, M.; Rizzo, P.; Sinopoli, M.; Vitale, S.; et al. Application of a Quantitative Framework to Estimate Trawling Impacts on Benthic Communities of the Sicilian Continental Shelf. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2025, 82, fsaf126. [CrossRef]

- Boulenger, A.; Chapeyroux, J.; Fullgrabe, L.; Marengo, M.; Gobert, S.; Assessing Posidonia oceanica Recolonisation Dynamics in Degraded Anchoring Sites. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2025, 216, 117960. [CrossRef]

- Environment and Resources Authority (ERA). Marine Protected Areas; ERA: Malta, 2023. Available online: https://era.org.mt/topic/marine-protected-areas-2/ (accessed on 29 March 2025).

- Environment and Resources Authority (ERA.). Monitoring Factsheet: Non-Indigenous Species; ERA: Malta, 2015. Available online: https://era.org.mt/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/MonitoringFactsheet_D2_NonIndigenousSpecies-1.pdf (accessed on 29 May 2025).

- Fenech, D.; Deidun, A.; Gauci, A. A spatial prioritisation exercise for marine spatial planning implementation within MPA MT105 of the Maltese Islands. Journal of Coastal Research 2020, 95 (sp1), 790. [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Managing Natura 2000 sites: The provisions of Article 6 of the Habitats Directive 92/43/EEC (2019/C 33/01). Official Journal of the European Union, 2019, C 33/01, 1–25. Available online: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/caf47cb6-207a-11e9-8d04-01aa75ed71a1/language-en (accessed on 29 May 2025).

- Transport Malta. Use of Automatic Identification Systems (AIS) by Fishing Vessels; Ports and Yachting Directorate, Transport Malta: Valletta, Malta, 2012. Available online: https://www.transport.gov.mt/Sea-Official-Notices-amp-Marine-Weather-Information-Port-Notices-Use-of-Automatic-Identification-Systems-06-12.pdf-f189 (accessed on 29 May 2025).

- EMODnet. Human Activities: Making Use of Our Oceans—EU Vessel Density Map Detailed Method; EMODnet Human Activities: Ostend, Belgium, 2019. Available online: Vessel density maps_method_v1.5.pdf (emodnet-humanactivities.eu) (accessed on 29 May 2025).

- MarineTraffic. What is the significance of the AIS Shiptype number? MarineTraffic, 2023. Available online: https://help.marinetraffic.com/hc/en-us/articles/205579997-What-is-the-significance-of-the-AIS-Shiptype-number (accessed on 25 February 2024).

- Said, A.; Macmillan, D.; Campbell, B. Crossroads at Sea: Escalating Conflict in a Marine Protected Area in Malta. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science 2018, 208, 52–60. [CrossRef]

- ERA. Natura 2000 – Standard Data Form, MT0000101, Żona fil-Baħar bejn Rdum Majjiesa u Għar Lapsi; ERA: Malta, 2019. Available online: https://era.org.mt/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/20190923_MT0000101-Majjiesa-Lapsi-Bahar-SCI.pdf (accessed on 29 May 2025).

- ERA. Conservation objectives and measures for Malta’s marine Natura 2000 sites; ERA: Malta, 2023. Available online:https://era.org.mt/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/MPAs-Conservation-Objectives-and-Measures_final_Feb2023.pdf (accessed on 29 May 2025).

- Milazzo, M.; Badalamenti, F.; Cechherielli, G.; Chemello, R. Boat Anchoring on Posidonia oceanica Beds in a Marine Protected Area (Italy, Western Mediterranean): Effect of Anchor Types in Different Anchoring Stages. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 2004, 299, 51–62. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0022098103004428?via%3Dihub (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Di Franco, E.; Pierson, P.; Di Iorio, L.; Calò, A.; Cottalorda, J. M.; Derijard, B.; Di Franco, A.; Galvé, A.; Guibbolini, M.; Lebrun, J.; Micheli, F.; Priouzeau, F.; Risso-de Faverney, C.; Rossi, F.; Sabourault, C.; Spennato, G.; Verrando, P.; Guidetti, P. Effects of Marine Noise Pollution on Mediterranean Fishes and Invertebrates: A Systematic Review. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2020, 158, 111450. [CrossRef]

- Pergent-Martini, C.; Monnier, B.; Lehmann, L.; Barralon, E.; Pergent, G. Major Regression of Posidonia oceanica Meadows in Relation with Recreational Boat Anchoring: A Case Study from Sant’Amanza Bay. J. Sea Res. 2022, 188, 102258. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S138511012200096X?via%3Dihub.

- Kofahl, M.; Hewson, S. Navigating the Law: Reducing Shipping Impacts in Marine Protected Areas; WWF Canada: Ottawa, Canada, 2020. Available online: https://wwf.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/WWF-MPA-6-Navigating-the-Law-v5.pdf (accessed on 29 May 2025).

- NOAA. MPAs and Enforcement: Module 7 – 7.3 Traditional Law Enforcement; NOAA: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2005; pp. 7–10. Available online: https://nmssanctuaries.blob.core.windows.net/sanctuaries-prod/media/archive/management/pdfs/enforce_mod7_curr.pdf (accessed on 29 May 2025).

- ELI. Legal Tools for Strengthening Marine Protected Area Enforcement: A Handbook; Environmental Law Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. Available online: https://www.eli.org/sites/default/files/eli-pubs/legal-tools-strengthening-mpa-enforcement-eli-2016_2.pdf (accessed on 29 May 2025).

- Randone, M.; Bocci, M.; Castellani, C.; Laurent, C. Safeguarding Marine Protected Areas in the Growing Mediterranean Blue Economy—Recommendations for Maritime Transport; PHAROS4MPAs Project, 2019.

- Noble-James, T., Bullimore, R., McBreen, F., O’Connor, F., Highfield, J., McCabe, C., Archer-Rand, S., Downie, A., Hawes, J., Mitchell, P., 2023, Monitoring benthic habitats in English Marine Protected Areas: Lessons learned, challenges and future directions, Marine Policy, vol. 157. [CrossRef]

- UNEP/MAP. Common Regional Framework for Integrated Coastal Zone Management; Priority Actions Programme Regional Activity Centre (PAP/RAC): Split, Croatia, 2019. Available online: https://iczmplatform.org/storage/documents/Ab5KKfiwRSrOLYPvVRYdKBdr0GAkl0Mx14KtOfRo.pdf (accessed on 29 May 2025).

- Bejarano AC, Michel J. Oil spills and their impacts on sand beach invertebrate communities: A literature review. Environmental Pollution. 2016;218:709–722. [CrossRef]

- Thomas G E, Cameron T C, Campo P, Clark D R, Coulon F, Gregson B H, Hepburn L J, McGenity T J, Miliou A, Whitby C, McKew B A. Bacterial Community Legacy Effects Following the Agia Zoni II Oil-Spill, Greece. Frontiers in Microbiology. 2020;11:1706. [CrossRef]

- El Moussaoui N, Idelhakkar B. The impact of oil spills on the economy and the environment. European Journal of Economic and Financial Research. Vol. 7, Issue 4, 2023. https://oapub.org/soc/index.php/EJEFR/article/view/1570/2146.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).