1. Introduction

Airborne electromagnetic (EM) methods based on natural-field sources have become an important tool for mapping subsurface resistivity in mineral exploration, especially in regions with rugged topography, restricted ground access, and structurally complex terranes. Modern passive airborne EM systems derive from the classical magnetotelluric (MT) method formulated by Tikhonov and Cagniard, in which subsurface conductivity is inferred from the frequency-dependent relationships between orthogonal components of naturally occurring electric and magnetic fields. Subsequent developments in magnetovariational (MV) and remote-reference MT practices demonstrated that spatially separated magnetic and electric measurements can yield stable MT transfer functions through cross-spectral analysis, provided the primary field maintains plane-wave coherence over the observation aperture.

These theoretical foundations enabled the adaptation of MT principles to airborne measurements. The airborne AFMAG prototype developed by Dr. Petr Kuzmin and collaborators introduced three-component magnetic sensing, MT-style spectral processing, and tensor-based transfer-function estimation into an airborne architecture, forming the basis for the ZTEM tipper system and later motivating the design of fully rotationally invariant airborne MT systems. MobileMT represents the culmination of these developments: it records broadband three-component magnetic-field variations in flight together with horizontal electric-field variations at a stationary reference, reconstructs the natural-field admittance tensor across 30 narrow frequency windows, and produces rotationally invariant, orientation-independent data suitable for quantitative inversion.

The ability of MobileMT to operate across a wide frequency range (≈26–21,000 Hz), and to retain broadband sensitivity to both shallow and deep structures makes it suitable for detecting porphyry-related alteration shells, feeder zones, and resistive potassic cores.

Although several studies have compared airborne AFMAG systems in specific geoelectrical settings and flat-relief environments such as the Athabasca Basin [

1,

2], the relative performance of MobileMT and ZTEM in geologically complex mineral systems and rugged relief conditions has not been previously evaluated using coincident survey data and consistent non-constrained inversion workflows. Importantly, no prior comparison has assessed system behaviour under both cultural-noise–affected and noise-free conditions within the same geological framework. The El Teniente and La Huifa porphyry centers provide such an opportunity: El Teniente lies adjacent to powerlines, whereas La Huifa is situated in a low-noise environment. This study presents the first direct system-level and field-based comparison of MobileMT and ZTEM in porphyry exploration, demonstrating that MobileMT consistently outperforms ZTEM regardless of noise conditions. In this article, we summarize the methodological foundations of MobileMT within the broader context of airborne MT, outline system-level differences affecting bandwidth, depth sensitivity, and noise susceptibility, and evaluate both systems using plan-view responses and resistivity-depth imaging. The results show that broadband total-field measurements yield superior anomaly coherence, improved depth penetration, and more geologically consistent structural resolution. These findings highlight the advantages of broadband airborne natural-field EM for porphyry exploration and support its broader application in structurally and relief complex settings.

2. MobileMT in the Framework of Airborne Natural-Field Magnetotellurics

Since late 1990s, Dr. Petr V. Kuzmin has played a key and decisive role in the modern development of airborne natural-source EM systems [

3]. His early AFMAG prototype, later documented in the Ontario Geological Survey report [

4], introduced key magnetotelluric concepts, three-component magnetic sensing, frequency-domain transfer-function estimation, and MT-style cross-spectral processing, into an airborne ‘passive’ EM field framework. This work formed the theoretical and engineering basis for Geotech Ltd.’s ZTEM system, the first widely deployed airborne AFMAG method in the last two decades. Dr. Kuzmin subsequently designed the three-component AirMT rotationally invariant system, intended as the next step beyond ZTEM, although it did not progress to full commercial operation. In personal communication, Dr. Kuzmin emphasized that he viewed ZTEM only as a transitional, trial implementation toward a complete multi-component and broadband airborne MT system. That progression ultimately culminated in MobileMT, which fully integrates broadband natural-field measurements, three-component magnetic sensing, and MT-derived admittance processing.

2.1. MobileMT Background

The MobileMT airborne electromagnetic technology applies the classical principles of the magnetotelluric (MT) method, as initially formulated by Tikhonov [

5] and Cagniard [

6], to broadband natural-field measurements acquired from an airborne platform and a stationary base station. In its classical definition, MT determines the electrical conductivity of the Earth from the ratios between orthogonal components of naturally occurring electric and magnetic fields, without requiring knowledge of the spatial distribution, geometry, or intensity of current systems in the ionosphere or magnetosphere. This principle follows the formulation summarized by Zhdanov [

7], in which subsurface conductivity is inferred entirely from the measurable relationships between the field components rather than from modeling of the unknown primary sources.

Under the MT assumption of a locally uniform, horizontally polarized plane-wave primary field, whose wavelengths in the audio-frequency band span tens to hundreds of kilometers, the natural EM field maintains coherent amplitude and phase relationships across distances far greater than typical sensor separations [

8,

9,

10]. As shown in magnetovariational (MV) and remote-reference MT (RR-MT) practice, spatially separated

- and

-field measurements can be combined via cross-spectral relationships to recover the same MT transfer functions as co-located measurements [

9,

11,

12]. These theoretical foundations support the MobileMT configuration, in which electric-field variations are recorded at a stationary ground base station while magnetic-field variations are measured continuously in flight.

Natural electromagnetic fields in the audio-frequency range are treated locally as horizontally polarized plane waves. Under this condition, the horizontal components dominate and define the measurable field relationships governing MT and MV transfer functions. MobileMT conforms to this assumption by simultaneously recording orthogonal three-component magnetic-field variations in flight and horizontal electric-field variations at a stationary ground reference station. The primary electromagnetic field is provided entirely by naturally generated sources, consistent with the MT and MV formulations described by Vozoff [

8], Berdichevsky and Dmitriev [

10], Zhdanov [

13] and Labson et al. [

9].

2.2. Airborne and Ground Components

The MobileMT airborne receiver consists of three orthogonal broadband inductive coils mounted inside a rigid fiberglass bird towed beneath the aircraft. These coils measure the time derivatives of the magnetic field (

) across a broad frequency range. The sensor is suspended on a specially designed stabilization and suspension system with an extended frequency range of protection that significantly reduces mechanical noise and moderates, but does not need to completely eliminate, attitude variations during flight. As shown in [

4,

14], the natural EM signals appear as the sharp, spiky events, and due to the nature of the EM fields, the events are much more intense in the horizontal axis coils than in the vertical.

The electric-field components are measured at a ground base station using two orthogonal pairs of grounded electric lines (“signal” and “reference”). Following Labson et al. [

9] and used RR-MT practices [

11,

12], the reference line is used for cross-spectral denoising: uncorrelated variations between orthogonal electric channels allow removal of local noise and provide a stable representation of the primary natural electric field.

Because the system records all three orthogonal magnetic components, the total magnetic-field vector is available at each moment, enabling the estimation of the admittance tensor that relates airborne magnetic variations to the horizontal reference field. Once the tensor columns are obtained in each frequency window, rotationally invariant quantities are formed by vector operations that remove the dependence on the airborne frame. In particular, the cross-product of the tensor columns produces a vector whose magnitude is unaffected by sensor orientation, providing an attitude-independent admittance measure for each frequency. Crucially, the rotational invariants arise from the admittance-tensor relations rather than replacing them; the tensor remains the fundamental representation of the MT field coupling. The invariants provide an orientation-free data product suitable for mapping and inversion, while the underlying tensor structure retains the full physical description of the electromagnetic interaction.

2.3. Data Synchronization, Processing and Enhanced Gradient Response

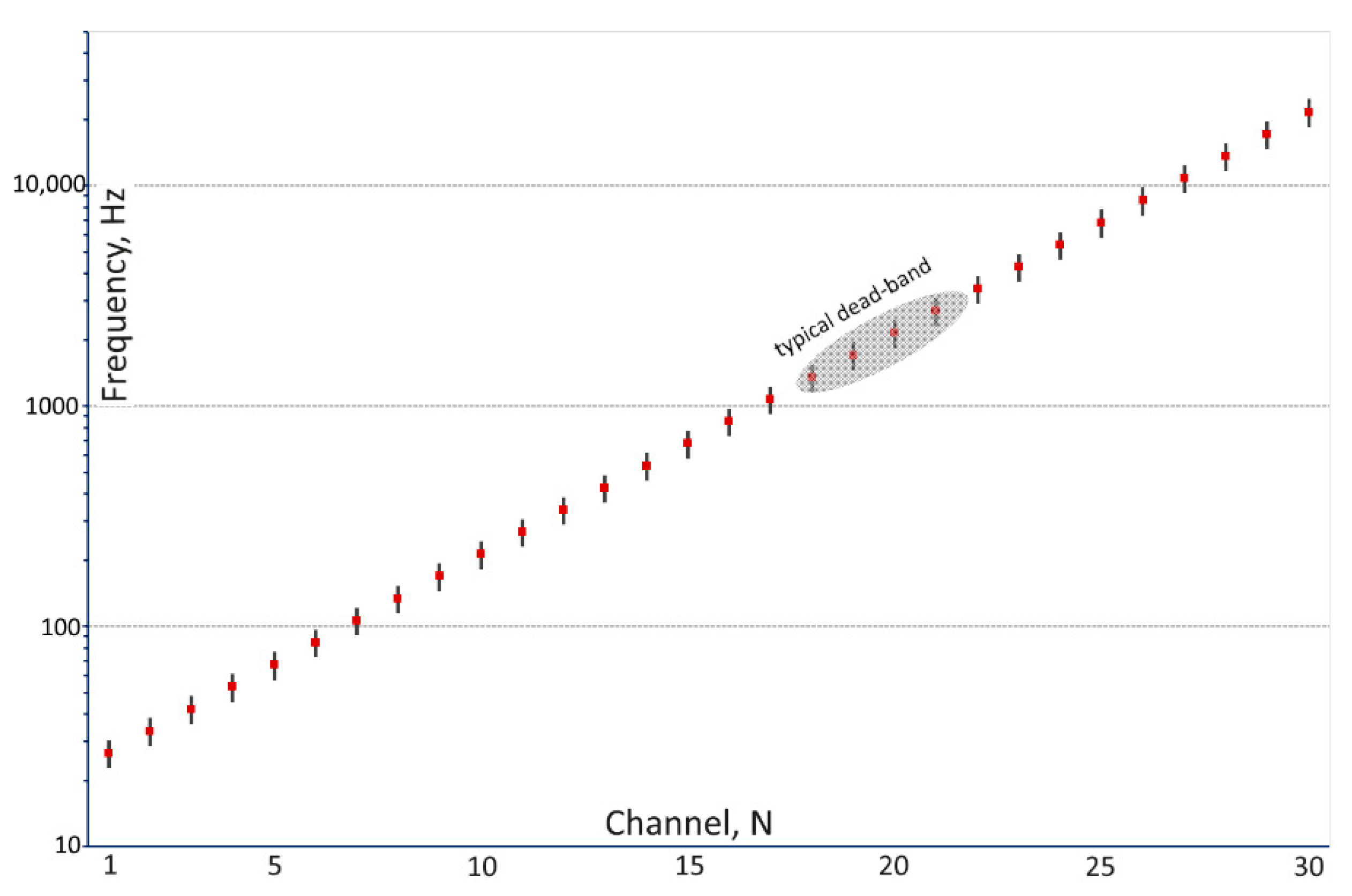

The airborne magnetic and ground electric fields are recorded synchronously at a sampling rate of 73,728 Hz. The raw time-series data sets are merged and transformed into the frequency domain using Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) algorithms. Stable spectral estimates are extracted across 30 logarithmically spaced narrow frequency windows spanning approximately 26–21,000 Hz, depending on natural field intensity and cultural noise (

Figure 1). This dense, narrow-band frequency architecture enhances system performance in several ways. First, it provides a high level of immunity to industrial 50/60 Hz noise and harmonics by isolating contaminated bands and using cross-spectral E-field referencing, producing bias-free admittance estimates. Second, the wide, continuous frequency coverage yields smooth skin-depth sampling from near-surface to >1 km, significantly improving vertical resolution in inversions. Third, the combination of high- and low-frequency windows increases lateral resolution and sensitivity to both narrow and large-scale structures. Finally, the large number of independent frequency windows enables flexible data selection tailored to specific geological targets, noise conditions, the dead-band width, and depth-of-investigation requirements.

In the MobileMTd (UAV) configuration, the lower frequency limit currently is extended to 14–20 Hz to improve sensitivity to deeper structures, especially under conductive overburdens [

2].

Individual measurement stations are formed by integrating the

data within sliding, overlapping temporal windows of customizable width (typically ~2 s). In the frames of working frequencies, the processed signal at a location

x can be presented as:

where

T is the time window length and

ψ is a weighting function which defines the shape of the moving average used to generate station values, or in the frequency-domain form:

where ω - angular frequency;

– magnetic flux density;

W(ω) – spectral window of

ψ(t).

The synchronized frequency-domain data are used to compute the magnetotelluric admittance tensor,

where

Erem is the remote electric field, and

is the total magnetic field intensity in a position

x along a survey line for an angular frequency ω . Each admittance estimate is formed from cross-spectral matrices. The admittance tensor contains complex transfer functions describing the linear relationships between the measured electric and magnetic field variations [

2].

Apparent conductivities σ are calculated from the determinant of the admittance tensor following the formulation adopted for MobileMT [

2,

14]:

where μ

0 is the magnetic permeability of free space. Each frequency window yields an independent estimate of apparent conductivity, producing a broadband response over a station

x.

In the context of the nature and key features of MobileMT technology, forward modelling exercises on the primitive basis assumptions, like in [

16], can not adequately predict MobileMT response and lead to wrong conclusions in the technology evaluation. Thus, the authors [

16] attribute measurement characteristics to the ‘AS2 system’ (which they associate with MobileMT, referencing [

17]) that MobileMT technology does not possess. These include treating the airborne data as a single-frequency, stationary H-field–only quantity and assuming a “real scalar” system. This contrasts fundamentally with MobileMT’s broadband, three-component dB/dt acquisition and its use of complex, frequency-dependent admittance tensors followed by rotational-invariant processing. The authors' calculated H-field dampens local anomalies, what is inherent to ground MT, not to airborne MobileMT technology.

2.4. Data Inversion Framework

The multi-frequency apparent-conductivity spectra are inverted to obtain depth-dependent resistivity models. Rapid interpretation commonly employs a conjugate-gradient 1D inversion with adaptive regularization [

18,

19], which is primarily suitable for layered geology under flat-relief conditions. For more detailed structural imaging, 2D inversion is performed using the MARE2DEM adaptive finite-element code [

15,

20,

21], which accommodates unstructured meshes and solves the 2.5D electromagnetic problem. Fully 3D resistivity models may be generated using Gauss–Newton inversion algorithms [

22] or the contraction integral equation method to calculate EM field components for an arbitrary 3D distribution of the electrical conductivity of the subsurface [

17].

3. Comparative Field Performance of MobileMT and ZTEM Systems

This section evaluates the relative field performance of MobileMT (Expert Geophysics Limited, 2018) and ZTEM (Geotech Ltd., 2006), using survey results from the El Teniente and La Huifa porphyry systems in central Chile. The comparison integrates (i) system-level differences that influence exploration efficiencies, (ii) plan-view responses, and (iii) resistivity-depth imaging along coincident or sub-parallel lines. Together, these elements demonstrate the practical advantages of MobileMT in resolving porphyry-related conductive and resistive zones, especially in rugged terrain.

3.1. Systems-Level Considerations

MobileMT records three orthogonal geometric components of magnetic-field variations, together with the horizontal electric field, at a reference station, enabling the derivation of magnetotelluric transfer functions. This configuration yields broadband sensitivity to both shallow and deep conductivity structures and maintains the complexity of the MT admittance tensor. In contrast, ZTEM utilizes only the vertical magnetic component to compute the tipper, making its response strongly dependent on lateral conductivity contrasts, while having no sensitivity to absolute resistivity and reduced sensitivity to compact 3D bodies [

23].

MobileMT typically provides 10–24 usable frequency windows for inversion, depending on natural-field strength and external noise, with a nominal system bandwidth of 26–21,000 Hz. ZTEM surveys, operating at a 2000 Hz sampling rate, generally provide no more than 6 frequency bands between 25 and 600 Hz (or 30-720 Hz) depending on natural-field strength and external noise. Because MobileMT employs rotationally invariant processing and does not require tilt correction, it avoids tilt-correction procedures, whose accuracy depends on unknown horizontal-field gradients between the reference base station and in-flight sensor [

24].

The principal comparative attributes of the two airborne EM systems are summarized in

Table 1.

3.2. Field Comparisons over El Teniente and La Huifa Porphyry Deposits

The field examples below, from central Chile over known porphyry deposits, illustrate the performance of both airborne EM passive systems.

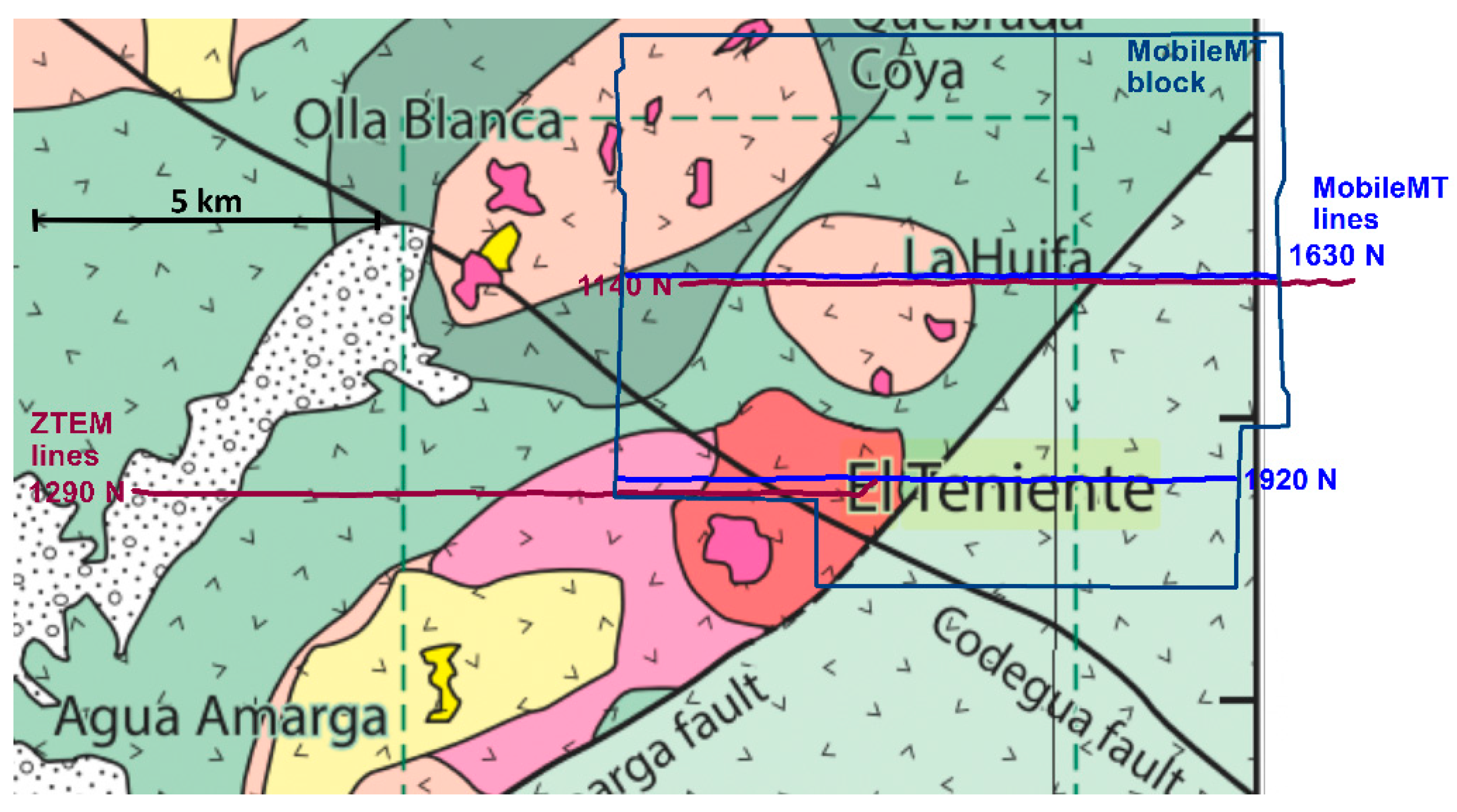

3.2.1. Brief Geology Description

El Teniente, located in the Andes of central Chile, is the world’s largest known copper-molybdenum deposit with the resource scale > 100 Mt Cu contained [

25]. A flat-lying sequence of Miocene Farellones Formation of arc-related volcanic and volcanoclastic andesitic rocks hosts El Teniente deposit. A series of felsic to intermediate intrusions was emplaced into the host rocks on the pre-mineralization (7.4-7.1 Ma), followed by porphyritic phases with peaks during the period between 6.46 and 5.48 Ma. Dacite pipes (5.5 Ma) and dacite porphyry dike (5.28 Ma) are temporally and spatially related to Cu and Mo-bearing veins and extensive potassic alteration [

26]. The Braden Pipe is a large, late- to post-mineralization breccia body with low copper grades, located at the center of the deposit. It forms an inverted cone roughly 1,200 m across at the surface, bounded by inward-dipping walls that range from about 60° to 80° [

26]. Important for the deposit formation, generally subvertical N-S, NE-SW and NW-SE crustal structures intersect at the deposit, and the actual depth to which copper mineralization extends is unknown [

25]. Another porphyry deposit, La Huifa, a quartz-diorite porphyry, is associated with hydrothermal breccias and alteration zones and is located 4 km northeast of the El Teniente deposit [

25]. A schematic geological map is shown in

Figure 2 along with MobileMT and ZTEM survey lines crossing the deposits.

3.2.2. Description and Analysis of the Systems’ Performance

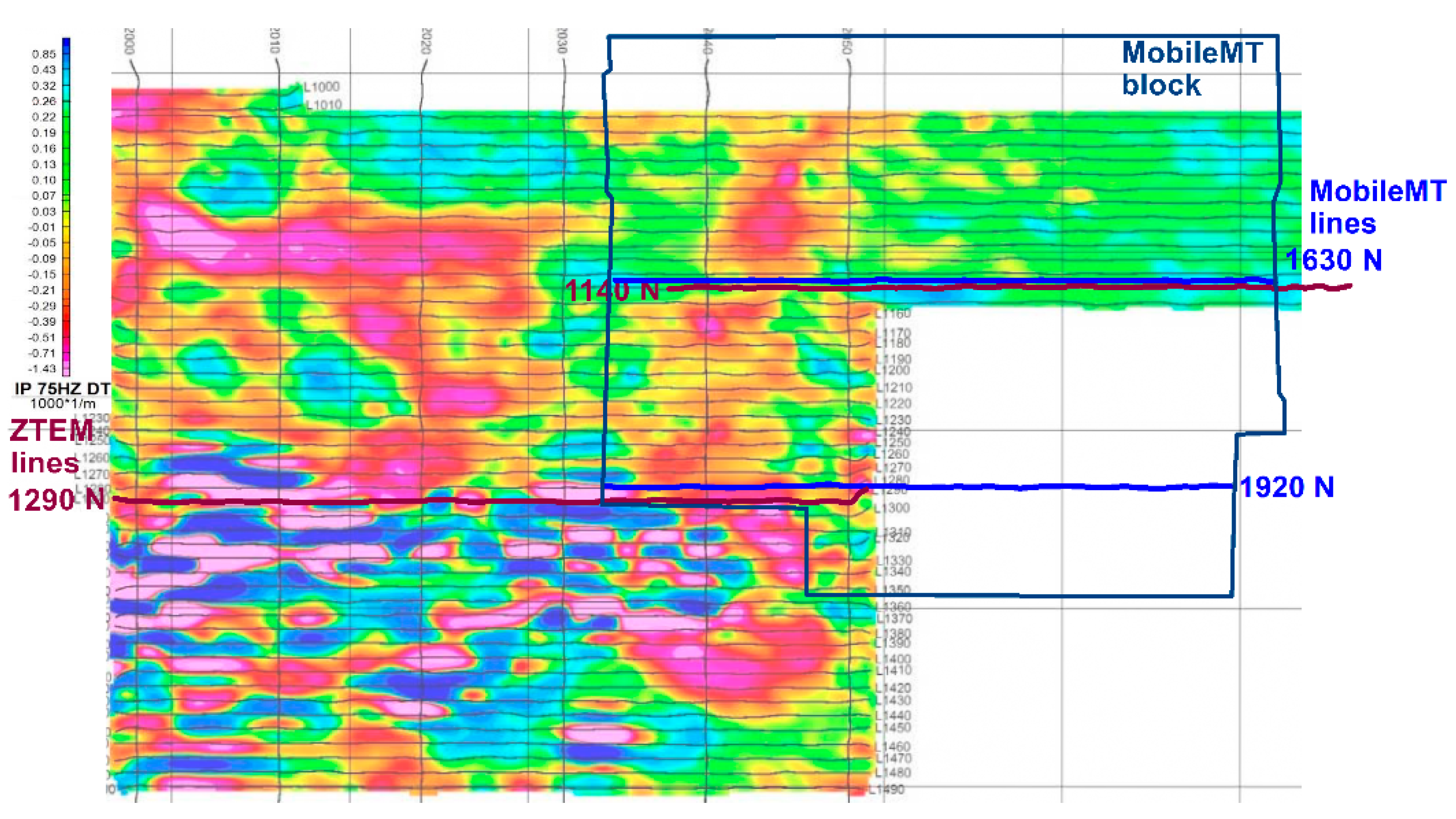

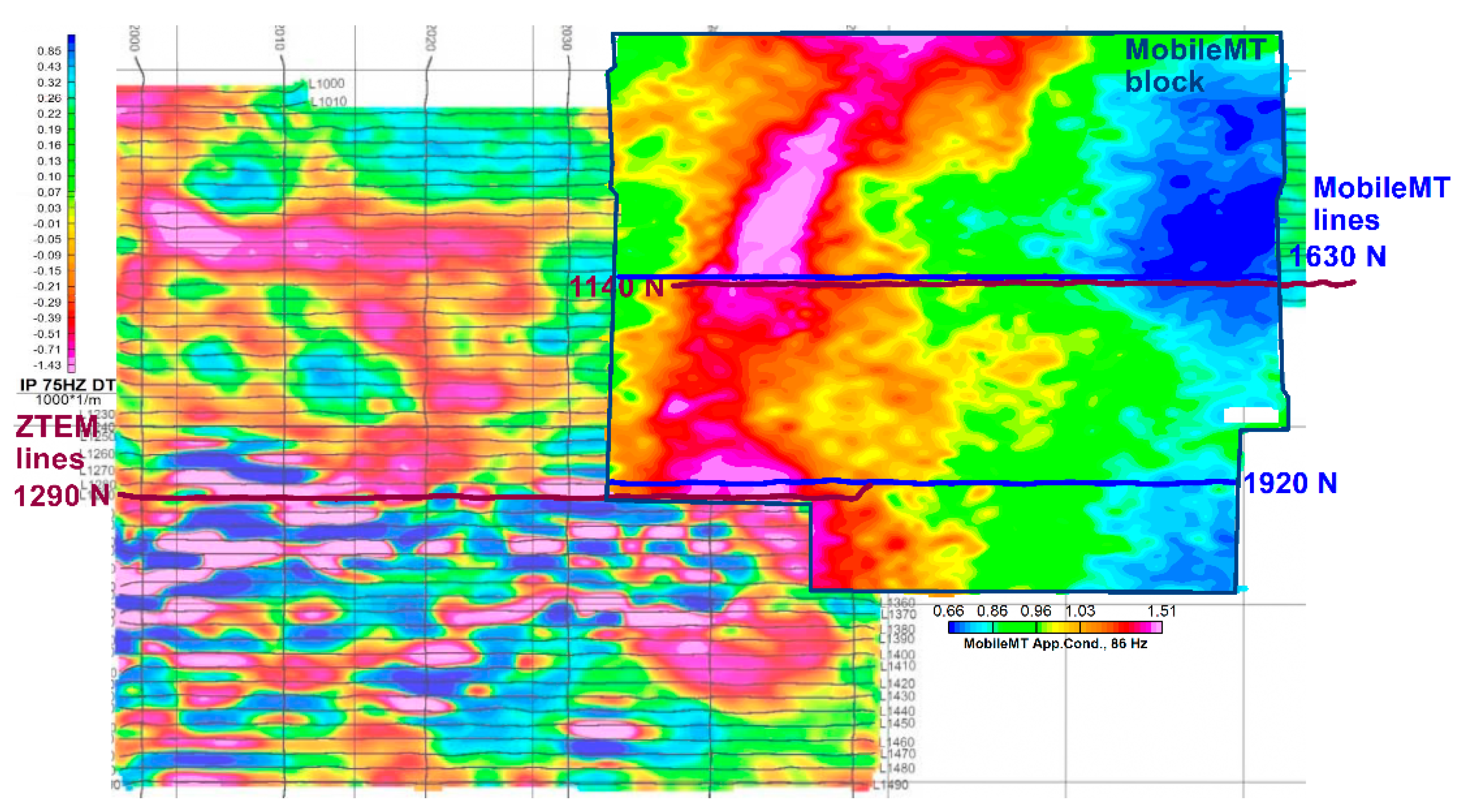

Below is a direct comparison between the tipper ZTEM data and the total-field broadband admittance MobileMT data over the deposits in plan view and in the inverted resistivity-depth images.

Figure 3 shows the ZTEM in-phase total divergence grid (75 Hz), illustrating that the western part of the El Teniente area is significantly contaminated by nearby powerlines. The ZTEM response over the deposit is dominated by short-wavelength noise and lateral striping, which obscures the conductive signature expected from porphyry feeder systems and alteration zones. Although a subtle anomaly is visible over La Huifa, its low contrast against a highly textured background prevents reliable interpretation or structural delineation.

In contrast, the MobileMT apparent-conductivity grid at a comparable frequency (86 Hz;

Figure 4) presents a coherent, geologically consistent spatial pattern. The northern portion of the El Teniente deposit, covered by the MobileMT survey block, exhibits a distinct conductive feature that is sharply differentiated from the surrounding host rocks. At La Huifa, MobileMT outlines a continuous NW–SE–aligned conductive trend, revealing the structural corridor that hosts the porphyry intrusion and associated breccia bodies. These plan-view results highlight the superior noise immunity (close to El Teniente) and anomaly focus provided by MobileMT.

Resistivity-depth sections along almost coincident above the El Teniente deposit MobileMT (L1920) and ZTEM (L1290) lines are shown in

Figure 5. Due to powerline interference, only three ZTEM frequencies were usable for inversion. The resulting ZTEM inversion resolves a shallow, laterally extensive conductor but fails to reproduce the vertical zonation, subvertical conduits, or deeper conductive roots typical of porphyry systems.

The MobileMT inversion, based on ten frequencies spanning a wide bandwidth, produces a robust and geologically consistent model. A central resistive zone coincides with the mapped potassic core, flanked by conductive alteration halos and subvertical conductive structures that mirror the known geometry of mineralized feeder zones. As shown in

Figure 6, the width of the resistive core in the MobileMT section corresponds closely to geological constraints (according to the geological section, ~800 m), and the conductive zones match the distribution of >0.5% Cu grades. These results indicate greater depth penetration of the MobileMT system, and its structural resolution is superior to ZTEM.

The La Huifa deposit lies roughly 4 km northeast of El Teniente and is also distant from the power lines (

Figure 2 and

Figure 3).

Figure 7 presents data profiles and resistivity sections along ZTEM L1140 and MobileMT L1630, which cross the La Huifa deposit along nearly coincident paths. ZTEM provides six frequencies between 25–600 Hz, yet the inversion shows a horizontal, comparatively weakly expressed conductor insufficient to characterize the deposit’s structural environment and vertical extent.

MobileMT, utilizing fifteen frequencies between 27 and 1124 Hz, recovers a resistivity pattern analogous to that observed at El Teniente and typical of porphyry systems. The model shows a resistive core interpreted as the potassic core, surrounded by conductive alteration zones and vertically continuous structures. The MobileMT response at La Huifa is laterally coherent and forms part of the broader NW–SE conductive trend identified in plan view, highlighting both the deposit and its controlling structural framework.

Across both porphyry systems, the field results demonstrate that MobileMT consistently provides higher anomaly contrast, greater structural coherence, and significantly improved depth informativeness compared with ZTEM. While ZTEM tipper data can detect strong conductivity gradients, its limited frequency content, high sensitivity to cultural noise, high risk of imprecise tilt corrections over rugged relief and reduced response over compact 3D bodies restrict its capabilities in complex porphyry environments. MobileMT’s broadband, narrow frequency windows, three-component acquisition and tensor-based admittance processing enable stable imaging of both shallow and deep structures, including more resistive potassic cores, alteration halos, and subvertical conductive feeder zones.

4. Conclusions

As the field case study shows, airborne MobileMT technology provides superior geological imaging in both noisy and noise-free environments.

At El Teniente, MobileMT maintains coherent broadband responses despite strong powerline interference, whereas ZTEM is restricted to three usable frequencies and fails to delineate porphyry-related structures. At La Huifa, far from cultural infrastructure, MobileMT again outperforms ZTEM, producing coherent plan-view anomalies and geologically reasonable resistivity sections. The weak, laterally discontinuous ZTEM response and inadequate geology inversion results at La Huifa demonstrate that reduced performance is not solely attributable to external noise but arises from the inherent limitations of tipper-only measurements, especially over rugged relief.

Broadband total-field measurements and tensor-based admittance processing underpin MobileMT’s advantages. The recording of three-component dB/dt, use of a ground electric reference, and rotationally invariant processing yield stable admittance tensors and strong anomaly contrast across a wide depth range. MobileMT resolves potassic cores, conductive alteration halos, and subvertical feeder zones at both deposits, while ZTEM fails to reproduce these features even under clean signal conditions.

Because MobileMT significantly outperforms ZTEM under both high-noise and low-noise conditions, the superiority of MobileMT reflects fundamental methodological and physical advantages rather than environmental circumstances. These case studies, therefore, confirm the practical advantages of MobileMT for exploration in rugged terrain and structurally complex porphyry systems.

Acknowledgments

The author acknowledges the substantial contributions of the technical department, field crews, data-processing staff, and geophysicists of Expert Geophysics Limited, whose work enabled the acquisition, quality control, and preparation of the datasets used in this study. Special thanks are extended to geophysicists Aleksei Philipovich and Aamna Sirohey for their essential roles in processing and inverting the MobileMT airborne electromagnetic data. The author also thanks Exploraciones Mineras Andinas S.A. for providing access to the geophysical survey reports and for granting permission to make the results of this work public, which made the comparative analysis possible.

Conflicts of Interest

Declare conflicts of interest or state “The authors declare no conflicts of interest.” Authors must identify and declare any personal circumstances or interest that may be perceived as inappropriately influencing the representation or interpretation of reported research results. Any role of the funders in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results must be declared in this section. If there is no role, please state “The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results”.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MT |

Magnetotellurics |

| EM |

Electromagnetics |

References

- Moul, F.; Sattel, D. A Comparison Between Airborne EM Responses Along the Virgin River Shear Zone: The Difference Depth Makes. In Proceedings of the Saskatchewan Geological Open House 2023, Saskatoon, Canada, 27–29 November 2023; pp. 1–2. Available online: https://publications.saskatchewan.ca/api/v1/products/122577/formats/142347/download (accessed on 4 December 2025).

- Prikhodko, A.; Bagrianski, A.; Kuzmin, P. Airborne natural total-field broadband electromagnetics—Configurations, capabilities, and advantages. Minerals 2024, 14, 704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prikhodko, A.; Bagrianski, A.; Kuzmin, P.; Sirohey, A. Natural Field Airborne Electromagnetics —History of Development and Current Exploration Capabilities. Minerals 2022, 12, 583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzmin, P.; Lo, B.; Morrison, E. Final Report on Modeling, Interpretation Methods and Field Trials of an Existing Prototype AFMAG System; Ontario Mineral Exploration Technology Program, Project P0102-007b; Geotech Ltd.: Toronto, Canada, 28 February 2005.

- Tikhonov, A.N. On determining electrical characteristics of the deep layers of the Earth’s crust. Dokl. Akad. Nauk SSSR 1950, 73(N2), 295–297. [Google Scholar]

- Cagniard, L. Basic theory of the magneto-telluric method of geophysical prospecting. Geophysics 1953, 18, 605–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhdanov, M.S. Geophysical Electromagnetic Theory and Methods; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands; Chapter 3, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Vozoff, K. The magnetotelluric method. In Electromagnetic Methods in Applied Geophysics; Nabighian, M.N., Ed.; Society of Exploration Geophysicists: Tulsa, OK, USA, 1991; Volume 2, Part B, pp. 641–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labson, V.F.; Becker, A.; Morrison, H.F.; Conti, R.J. Geophysical exploration with audio-frequency natural magnetic fields. Geophysics 1985, 50, 656–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berdichevsky, M.N.; Dmitriev, V.I. Models and Methods of Magnetotellurics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Gamble, T.; Goubau, W.; Clarke, J. Magnetotellurics with a remote magnetic reference. Geophysics 1979, 44(NO.1), 53–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egbert, G.D. Robust multiple-station magnetotelluric data processing. Geophys. J. Int. 1997, 130, 475–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhdanov, M. S. Foundations of geophysical electromagnetic theory and methods, Second edition; Elsevier Science, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Prikhodko, A.; Bagrianski, A.; Wilson, R.; Belyakov, S.; Esimkhanova, N. Detecting and recovering critical mineral resource systems using broadband total-field airborne natural source audio frequency magnetotellurics measurements. Geophysics 2024, 89, WB13–WB23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prikhodko, A.; Sirohey, A.; Philipovich, A. Advancing Deep Ore Exploration with MobileMT: Rapid 2.5D Inversion of Broadband Airborne EM Data. Minerals 2025, 15, 874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, A.; Ansari, S.M.; Mackie, R.; Soyer, W. Mineral Exploration with Natural-Source EM: Comparing Ground and Airborne Methods. In Proceedings of the Near Surface Geoscience Conference & Exhibition 2025, Naples, Italy, 2025; EAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Jorgensen, M.; Zhdanov, M.S.; Gribenko, A.; Cox, L.; Sabra, H.E.; Prikhodko, A. 3D Inversion and Interpretation of Airborne Multiphysics Data for Targeting Porphyry System, Flammefjeld, Greenland. Minerals 2024, 14, 1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhdanov, M. S. Geophysical Inverse Theory and Regularization Problems. In Methods in Geochemistry and Geophysics; Elsevier: Amsterdam, 2002; Vol. 36. [Google Scholar]

- Golubev, V. Adaptive regularized 1D inversion for multi-frequency MobileMT data. Technical Report for Expert Geophysics Limited, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Key, K.; Weiss, C. Adaptive finite-element modeling for marine MT. Geophysics 2006, 71, G291–G299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Key, K. MARE2DEM: A 2-D inversion code for controlled-source electromagnetic and magnetotelluric data. Geophys. J. Int. 2016, 207, 571–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haber, E.; Oldenburg, D.; Shekhtman, R.; Schwarzbach, C. An adaptive mesh method for electromagnetic inverse problems. Geophysics 2012, 77, 9–12. [Google Scholar]

- Jansen, J.C.; Cristall, J.A. Mineral Exploration Using Natural EM Fields. In Proceedings of the Exploration 17: Sixth Decennial International Conference on Mineral Exploration, Toronto, ON, Canada, 21–25 October 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kuzmin, P.V.; Borel, G.; Morrison, E.; Dodds, J. Geophysical Prospecting Using Rotationally Invariant Parameters of Natural Electromagnetic Fields. U.S. Patent 8,289,023, filed 23 December 2009, issued 16 October 2012.

- Skewes, M.A.; Arévalo, A.; Floody, R.; Zuñiga, P.; Stern, C.R. The El Teniente megabreccia deposit, the world’s largest copper deposit. In Super Porphyry Copper and Ore Deposits of the Central Andes; Porter, T.M., Ed.; Society of Economic Geologists, Special Publication 7, 2005; pp. 195–217. [Google Scholar]

- Cannell, J.; Cooke, D.R.; Walshe, J.L.; Stein, H. Geology, Mineralization, Alteration, and Structural Evolution of the El Teniente Porphyry Cu–Mo Deposit. Econ. Geol. 2005, 100, 979–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, J.J.; Baker, M.J.; Cooke, D.R.; Wilkinson, C.C.; Inglis, S. Exploration Targeting in Porphyry Cu Systems Using Propylitic Mineral Chemistry: A Case Study of the El Teniente Deposit, Chile. Economic Geology 2020, 115, 771–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geotech Ltd. Report on a helicopter-borne z-axis tipper electromagnetic (ZTEM) and aeromagnetic geophysical survey. Sewell Project, Rancagua, Chile for Exploraciones Mineras S.A., 2014; p. 339 p. [Google Scholar]

- Expert Geophysics Limited and MPX Geophysics Limited. Data Acquisition and Processing Report about Helicopter-borne MobileMT Electromagnetic & Magnetic survey for Exploraciones Minerals S.A., El Teniente Este Block MobileMT Project, 2022, 60 p.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).