Submitted:

05 December 2025

Posted:

09 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Objects of research

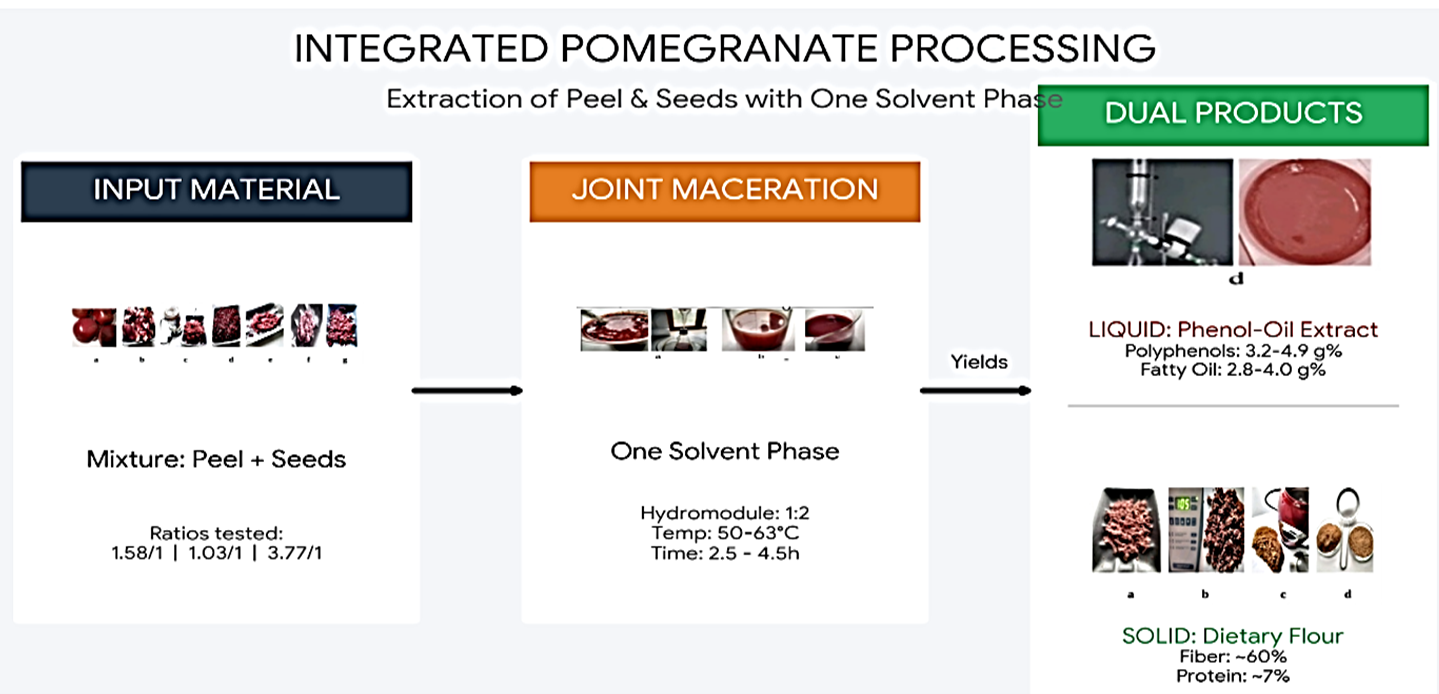

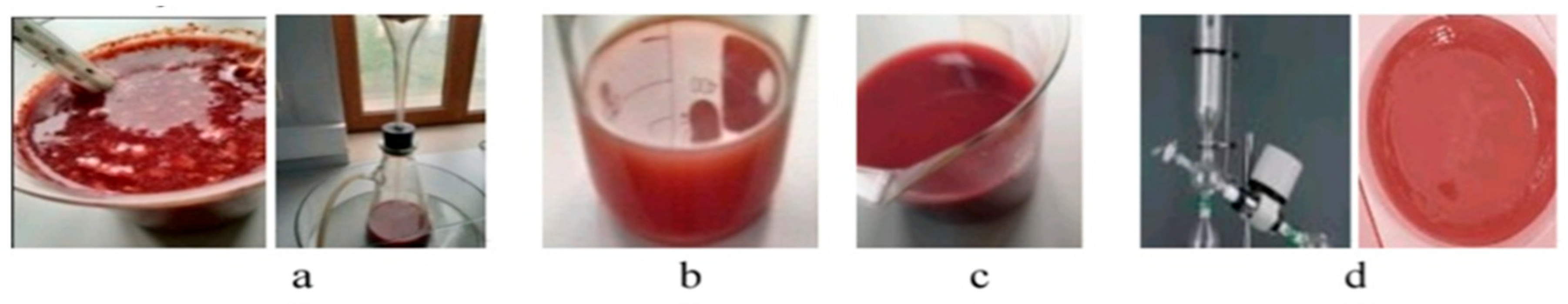

2.2. Extraction

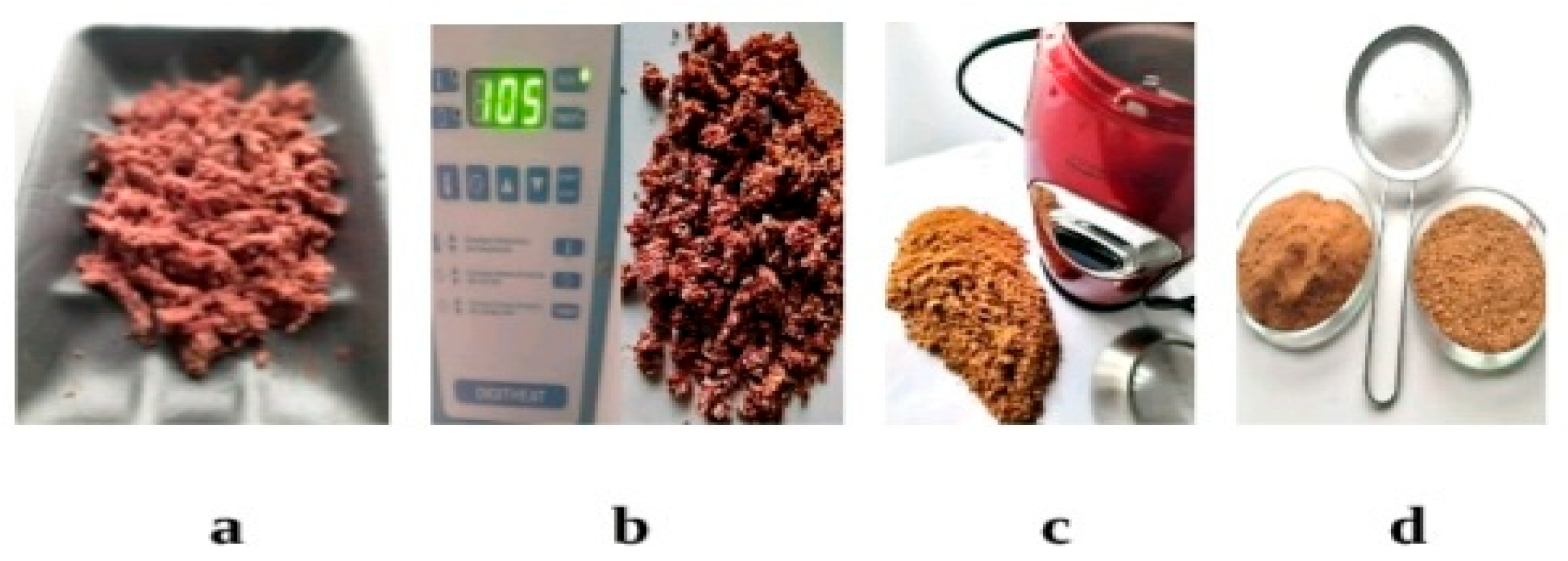

2.3. Transformation of formed solutions and insoluble residues

2.4. Chemical analyses

- Dry substances - according to GOST (The State Standard of Russia) 24027.2-80, by drying the prepared sample of the test material to a constant mass.

- Simple sugars - according to GOST 8756.13-8, the method is based on the ability of sugars with an aldehyde group to interact with Fehling's reagent and reduce copper oxide (CuO) to Cu2O, which precipitates as a reddish precipitate.

- Total acidity is determined by the titrimetric method according to GOST ISO 750-2013, based on titration in the presence of an indicator before discoloration of the analyzed solution (0.0064 is the conversion coefficient of 0.1 N NaOH solution to citric acid).

- Crude protein – by the Keldal method (6.25 is the conversion factor used to calculate the protein content).

- Crude fat – gravimetric method according to GOST 8756.21, the method includes extraction of fat with gasoline, and then determination of the fat mass in a certain part of the resulting extract after solvent removal.

- Minerals (ash) – according to GOST 24027.2-80, by weight of the residue from burning a dry sample of the starting material in a muffle furnace.

- Fiber is an enzymatic gravimetric method according to GOST 34844-2002, this standard applies to special-purpose food products, biologically active and dietary supplements.

- Total polyphenols – according to GOST 24027.2-80, based on titration of the unreacted indigocarmine residue with 0.1 N KMnO4 solution (potassium permanganate) after oxidation of phenolic substances. Other compounds react with permanganate, therefore, all substances oxidized by this reagent are titrated first, and then the residue in the extract is titrated after treatment with activated carbon, which is capable of adsorbing only polyphenols. The amount of phenols is determined based on the difference between the amount of permanganate spent on the first and second oxidation. A coefficient of 0.004157 is used to convert milliliters of 0.1 N KMnO4 solution into grams of phenols. This principle also underlies Article 1.5.3.0008.18 of the Russian Pharmacopoeia (XIV edition), which relates to the methodology for determining tannins in medicinal raw materials.

2.5. Primary data processing

3. Results

3.1. Thermal maceration without enzyme involvement

3.1.1. The component composition of primary extracts from seed maceration and a mixture of peel and seeds of pomegranate sample number 1

3.1.2. The component composition of primary extracts from thermal maceration of a mixture of P+BS pomegranates number 2

3.2. Thermal maceration of the P+BS mixture of pomegranate sample number 3 with the participation of the enzyme Fructozym MA-LG

3.3. Concentration of the primary extract

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

References

- Cano-Lamadrid, M.; Martínez-Zamora, L.; Castillejo, N.; Artés-Hernández, F. From pomegranate byproducts waste to worth: A review of extraction techniques and potential applications for their revalorization. Foods 2022, 11(17), 2596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capanoglu, E.; Nemli, E.; Tomas-Barberan, F. Novel approaches in the valorization of agricultural wastes and their applications. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 2022, 70, 6787–6804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hafizov, S.G.; Qurbanov, I.S.; Hafizov, G.K. Improving the biotechnology of pomegranate botanical extracts, taking into account the need to deepen the processing of raw materials. J Biological Sci. 2020, 20, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giri, N.A.; Gaikwad, N.N.; Raigond, P.; Damale, R.; Marathe, R.A. Exploring the potential of pomegranate peel extract as a natural food additive: A review. Curr Nutr Rep. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Q.; Li, M.; Wen, J.; Ren, F.; Yang, Z.; Jiang, X.; Chen, Y. The bioactivity and applications of pomegranate peel extract: A review. J of Food Biochemistry 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannavacciuolo, C.; Pagliari, S.; Celano, R.; Campone, L.; Rastrelli, L. Critical analysis of green extraction techniques used for botanicals: Trends, priorities, and optimization strategies-A review. Trends in Analytical Chemistry 2024, 173117627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usman, M.; Nakagawa, M.; Cheng, S. Emerging Trends in Green Extraction Techniques for Bioactive Natural Products. Processes 2023, 11(12), 3444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Luan, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, J.; Duan, Z.; Ruan, R. Current technologies and uses for fruit and vegetable wastes in a sustainable system: A review. Foods 2023, 12(10), 1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Salas, L.; Exposito-Almellon, X.; Borras-Linares, I.; Lozano-Sanchez, J.; Segura-Carretero, A. Design of experiments for green and GRAS solvent extraction of phenolic compounds from food industry by-products-A systematic review. TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry 2024, 117536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ain, H.B.U.; Tufail, T.; Bashir, S.; Ijaz, N.; Hussain, M.; Ikram, A.; et al. Nutritional importance and industrial uses of pomegranate peel: A critical review. Food Science and Nutrition 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaderides, K.; Kyriakoudi, A.; Mourtzinos, I.; Goula, A.M. Potential of pomegranate peel extract as a natural additive in foods. Trends in Food Science & Technology 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buenrostro-Figueroa, J.J.; Nevárez-Moorillón, G.V.; Chávez-González, M.L.; Sepúlveda, L.; Ascacio-Valdés, J.A.; Aguilar, C.N.; et al. Improved extraction of high value-added polyphenols from pomegranate peel by solid-state fermentation. Fermentation 2023, 9(6), 530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydin, M.; Tontul, I.; Turker, S. Enhanced recovery of phenolic compounds in pomegranate by-products using green technologies. Journal of Food Process Engineering 2025, 48(11), e70273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Foo Su, C.; Chou, W.S. A review on the extraction of polyphenols from pomegranate peel for punicalagin purification: techniques, applications, and future prospects. Sustainable Food Technology 2025, 3(2), 396–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez-Rodríguez, G.; Montero, L.; Viganó, J.; Cifuentes, A.; Rostagno, M.A.; Ibáñez, E. Advanced extraction techniques combined with natural deep eutectic solvents for extracting phenolic compounds from pomegranate (Punica granatum L.) peels. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 9992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hafizov, S.G.; Musina, O.N.; Hafizov, G.K. Extracting hydrophilic components from pomegranate peel and pulp. Food Processing: Techniques and Technology (In Russian). 2023, 53(1), 168–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castiel, I.; Gueniche, A. Non-therapeutic cosmetic use of at least one pomegranate extract, as agent for firming skin of a subject, who has weight modification prior to and/or after an aesthetic surgery and to prevent and/or treat sagging skin, in espcenet. Patent FR 2967063A1, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Malviya, S.; Jha, A.; Hettiarachchy, N. Antioxidant and antibacterial potential of pomegranate peel extracts. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2014, 51, 4132–4137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbanzadeh, R.; Rezaei, K. Optimization of an aqueous extraction process for pomegranate seed oil. J of the American Oil Chemists Society 2017, 94(12), 1491–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaseke, T.; Opara, U.L.; Fawole, O.A. Effects of Enzymatic Pretreatment of Seeds on the Physicochemical Properties, Bioactive Compounds, and Antioxidant Activity of Pomegranate Seed Oil. Molecules 2021, 26(15), 4575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomakou, N.; Kalfa, E.; Kyriakoudi, A.; Kaderides, K.; Mourtzinos, İ.; Goula, A.M. An approach for the valorization of pomegranate by-products using ultrasound and enzymatic methods. Sustainable Chemistry for the Environment 2024, 5, 100060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, K.; Dadmohammadi, Y.; Abbaspourrad, A. Nutritional and bioactive components of pomegranate waste used in food and cosmetic applications: A review. Foods 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hafizov, S. G. Pomegranate seed juice: chemical composition in freshly squeezed form and technological behavior during cold storage without freezing. In Proceedings of the 5th International scientific conference «foundations and trends in research», Amsterdam, 2024; pp. 117–122. Available online: https://ojs.publisher.agency/index.php/ERM/article/view/2981.

- Hafizov, S.G. The quality of pomegranate juices obtained from pomegranate grain or whole pomegranates with preserved peel at different pressure values. In Proceedings of the 4th International scientific conference “Foundations and trends in research”, Amsterdam, 2023; pp. 22–28. Available online: https://ojs.publisher.agency/index.php/ERM/article/view/2391.

- Gullón, P.; Astray, G.; Gullón, B.; Tomasevic, I; Lorenzo, J.M. Pomegranate peel as suitable source of high-added value bioactives: Tailored functionalized meat products. Molecules 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J; Sun, M; Yu, J; Wang, J; Cui, Q. Pomegranate seeds: a comprehensive review of traditional uses, chemical composition, and pharmacological properties. Front Pharmacol. 2024, 11; 15, 1401826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lampakis, D.; Skenderidis, P.; Leontopoulos, S. Technologies and extraction methods of polyphenolic compounds derived from pomegranate (Punica granatum) Peels. A mini review. Processes 2021, 9, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafizov, S.G.; Hafizov, G.K. Industrially applied methods for the production of pomegranate polyphenols. Science and innovations 2021: Development directions and priorities 2021, 2, 198–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, T.A.; Fetzer, D.E.L.; Motta dos Passos, N.H.; Ambye-Jensen, M. Maceration and fractionation technologies in a demonstration-scale green biorefinery: Proteins, sugars, and lipids extraction and energy efficiency. Industrial crops and products 2025, 223, 120142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Moujahed, S.; Dinica, R.M.; Cudalbeanu, M.; Avramescu, S.M.; Msegued Ayam, I.; Ouazzani Chahdi, F.; et al. Characterizations of six pomegranate (Punica granatum L.) varieties of global commercial interest in morocco: pomological, organoleptic, chemical and biochemical studies. Molecules 2022, 27(12), 3847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafizov, S.G.; Hafizov, G.K. Scientific substantiation and development of principles for the selection of pomegranate varieties with high juice yield (In Russian). Fruit growing and viticulture in the South of Russia 2024, 87(3), 207–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skrt, M.; Albreht, A.; Vovk, I.; Constantin, O.E.; Râpeanu, G.; Sežun, M.; et al. Extraction of polyphenols and valorization of fibers from istrian-grown pomegranate (Punica granatum L.). Food 2022, 11, 2740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafizov, S.G. Comparative study of the chemical composition of bio-waste of pomegranate, persimmon, mandarin and pear. Proceedings of the 6th International Scientific Conference «Modern Scientific Method» (April 18-19, 2024). Vienna, Austria; 2024, pp. 31–35. Available online: https://ojs.scipub.de/index.php/MSM/article/view/3392.

- Wang, Z.; Pan, Z.; Ma, H.; Atungulu, G.G. Extract of phenolics from pomegranate peels. The Open Food Science J. 2011, 5, 1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harscoat-Schiavo, Ch.; Khoualdia, B.; Savoire, R.; Hobloss, S.; Buré, C. Extraction of phenolics from pomegranate residues: Selectivity induced by the methods. J of Supercritical Fluids 2021, 176, 105300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saffarzadeh-Matin, S.; Khosrowshahi, F.M. Phenolic compounds extraction from Iranian pomegranate (Punica granatum) industrial waste applicable to pilot plant scale. Industrial Crops and Products 2017, 108, 583 597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenary, R.E.; Zahed, N.; Shabani, G. Evaluation of physicochemical, antimicrobial, and antioxidant properties of the set yogurt containing anthocyanin extract of pomegranate peel during storage. Food research journal. 2025, 35(3), 73–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, E.M.; Machado, M.; Pintado, M.; Silva, S. Evaluating pomegranate seed oil for potential topical applications: safety, anti-inflammatory activity and wound healing in skin cell models. Inflammopharmacol 2025, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, Steve; Dreher, Mark; Green, Rick. Method and composition for producing a stable and deodorized form of pomegranate seed oil. Patent US 9506011B2, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, M.; Yu, G.; Pu, J.; Tian, K.; Tang, X.; et al. Comparative analysis of the phenolic contents and antioxidant activities of different parts of two pomegranate (Punica granatum L.) Cultivars: ‘Tunisia’ and ‘Qingpi. Front. Plant Sci. 2-23; 14, 1265018. [CrossRef]

- Benchagra, L.; Berrougui, H.; Islam, M.O.; Ramchoun, M.; Boulbaroud, S.; Hajjaji, A.; et al. Antioxidant effect of moroccan pomegranate (Punica granatum L. Sefri Variety) extracts rich in punicalagin against the oxidative stress process. Foods 2021, 10, 2219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaleri, M.; Li, Q. Stereoselective conversions of carbohydrate anomeric hydroxyl group in basic and neutral conditions. Molecules 2025, 30(1), 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Wei, Y.; Zhou, Q.Y.; et al. Direct radical functionalization of native sugars. Nature 2024, 631, 319–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byron, Bates; Fritz Erich, A.; Liker; Harley, R. Processes for extracting phytochemicals from pomegranate solids and compositions and methods of use thereof. 2015. Available online: https://patents.google.com/patent/US8658220B2/en.

- Maiuolo, J.; Liuzzi, F.; Oppedisano, F.; Spagnoletta, A.; Caminiti, R.; Mazza, V.; et al. Polyphenols and Fibre: Key Players with Antioxidant Activity in Two Extracts from Pomegranate (Punica granatum). International J of Molecular Sciences 2025, 26(19), 9807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Türkyılmaza, M.; Hamzaoglu, F.; Ozkan, M. Enzimatically induced copigmentation in pomegranate juice concentrate during storage. Applied Food Research 2025, 5(2), 101449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraz, L.P.; Silva, E.K. Multi-stage ethanol–water biorefining of pomegranate pomace by-product enables time-resolved fractionation of fatty acids, phenolics and protein-rich residual biomass. Bioresource Technology 2025, 133734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merlini, F.B.; Kotsuka da Silva, L.; Alves, G.; Bastos, J.C.S.; Kotsuka da Silva, M.; Rocha, S.A. Nutritional properties of pomegranate (Punica granatum) agroindustrial subproducts and their application in fresh pasta. Research, society and development 2025, 14, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Components | P | BS | P+BS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dry substances | 40.00±0.55 | 41.32±0.58 | 40.51±0.52 |

| Sucrose | 0.66 ±0.01 | 0.00 | 0.40±0.01 |

| Monosaccharides | 10.08±0.13 | 9.05±0.15 | 9.68±0.14 |

| Titrated acids (in terms of citric acid) | 4.39± 0.06 | 1.35±0.02 | 3.21±0.04 |

| Crude protein (N x 6.25) | 2.50±0.04 | 5.13±0.05 | 3.52±0.05 |

| Crude fat | 2.80±0.03 | 7.30±0.10 | 4.54±0.05 |

| Fibers | 13.32±0.19 | 17.04±0.22 | 14.76±0.20 |

| Mineral substances | 0.75±0.01 | 0.80±0.01 | 0.77±0.01 |

|

Substances capable of reacting with KMnO4: Total Polyphenols |

5.50±0.09 3.60±0.04 |

0.65±0.01 0.25±0.01 |

3.62±0.05 2.28±0.03 |

| p-value | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.05 |

| Components | Maceration solutions: | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| BS (100 g) | P+BS (258 g) | ||

| G/100 ml | G/100 ml | The ratio between the P and BS components of the total mass of the part of the substance that came out of the mixture into solution,%/% | |

| Dry substances | 8.27±0.20 | 9.30±0.10 | 64.43/35.57 |

| Monosaccharides | 3.88±0.09 | 3.53±0.07 | 55.98/44.02 |

| Titrated acids (in terms of citric acid) | 0.52±0.01 | 1.25±0.04 | 83.36/16.64 |

| Crude protein (N x 6.25) | 1.26±0.03 | 0.80±0.02 | 37.00/63.00 |

| Crude fat | 1.15±0.02 | 0.73±0.02 | 36.99/63.01 |

| Fibers | 1.05±0.02 | 0.32±0.01 | 72.33/27.67 |

| Mineral substances | 0.15±0.01 | 0.17±0.01 | 64.71/35.29 |

|

Substances capable of reacting with KMnO4: Total Polyphenols |

0.26±0.01 0.09±0.01 |

2.50±0.04 0.79±0.02 |

95.84/4.16 67.18/32.82 |

| p-value | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.05 |

| Components |

The yield: | |

|---|---|---|

| % of the total mass of the substance in 100 g BS | % of the total mass of the substance in 258 g P+BS 1.58/1 (weight/weight) | |

| Dry substances | 40.03±0.99 | 44.48±0.97 |

| Monosaccharides | 85.75 ±2.12 | 70.68±1.75 |

| Titrated acids (in terms of citric acid) | 77.04±1.91 | 75.48±1.55 |

| Crude protein (N x 6.25) | 49.12± 1.21 | 44.05±0.93 |

| Crude fat | 31.50±0.78 | 32.15±0.66 |

| Fibers | 12.32±0.30 | 10.97±0.23 |

| Mineral substances | 37.50±0.92 | 42.71±0.88 |

|

Substances capable of reacting with KMnO4: Total Polyphenols |

80.00±1.97 72.00±1.78 |

80.30±1.65 67.18±1.38 |

| p-value | 0.05 | 0.05 |

|

Components |

P+BS mixture, G/100 g of raw mass | Solution, G/100 ml |

Yield of the substance in solution, % of the total mass of the substance in 106.6 g of the crude mixture |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dry substances | 42.92±0.50 | 9.46±0.12 | 50.56±1.14 |

| Sucrose | 0.52±0.01 | 0.10 ±0.01 | 45.45 ±1.02 |

| Monosaccharides | 14.59±0.17 | 4.85±0.06 | 78.41±1.76 |

| Titrated acids (in terms of citric acid) | 4.17 ±0.04 | 1.33 ±0.02 | 75.34±1.69 |

| Crude protein (N x 6.25) | 3.08±0.04 | 0.78±0.02 | 58.04± 1.03 |

| Crude fat | 4.70±0.05 | 0.60±0.01 | 30.12 ±0.67 |

| Fibers | 10.04±1.26 | 0.28±0.01 | 6.57±0.15 |

| Mineral substances | 0.84 ±0.01 | 0.15±0.01 | 42.69±0.96 |

|

Substances capable of reacting with KMnO4: Total Polyphenols |

4.98±0.06 2.79±0.03 |

1.37±0.02 0.77±0.01 |

64.96±1.46 65.20±1.47 |

| p-value | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.05 |

| Part of the fetus | Gram | % of the total weight of the fetus | Ratio between P and BS (weight/weight) |

|---|---|---|---|

| P | 90.5±3.4 | 37.6±1.41 |

3.77/1 |

| Grains with juice | 150.5±5.6 | 62.4±2.32 | |

| Juice | 126.5±4.7 | 52.4±1.95 | |

| BS | 24.0±0.9 | 10.0±0.37 |

| Components | Initial crude mixture, G/100 G of crude mass | Solution, G/100 ml |

Yield of the substance in solution, % of the total mass of the substance in 114.5 G P+BS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dry substances | 42.21 ±0.40 | 12.91±0.20 | 61.16±1.55 |

| Sucrose | 0.85± 0.01 | 0.31±0.01 | 63.92±1.62 |

| Monosaccharides | 18.93±0.18 | 8.43±0.12 | 77.80±1.97 |

| Titrated acids (in terms of citric acid) | 3.16±0.03 | 1.47±0.02 | 72.24±1.83 |

| Crude protein (N x 6.25) | 2.16 ±0.03 | 0.40±0.01 | 36.57±1.11 |

| Crude fat | 3.92±0.04 | 0.80±0.02 | 40.81±0.58 |

| Fibers | 7.79±0.07 | 0.15 ±0.01 | 3.36±0.08 |

| Mineral substances | 0.64±0.01 | 0.13±0.01 | 17.80±0.45 |

|

Substances capable of reacting with KMnO4: Total Polyphenols |

4.76 ±0.04 3.21±0.02 |

1.92 ±0.03 1.33±0.02 |

70.46±1.79 72.28±1.83 |

| p-value | 0.05 | 0.05 |

| Components | a | b | c | d |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dry substances | 57.00±0.50 | 57.00±0.20 | 57.00±0.20 | 57.00±0.20 |

| Monosaccharides | 26.09±0.22 | 32.09±0.28 | 29.21±0.26 | 34.97±0.31 |

| Sucrose | 0.00 | 1.14±0.01 | 0.50±0.01 | 1.23±0.01 |

| Titrated acids (in terms of citric acid) | 3.50±0.04 | 6.81±0.07 | 7.83±0.06 | 5.84±0.05 |

|

Substances capable of reacting with KMnO4: Total Polyphenols |

1.67±0.02 1.27±0.01 |

5.92±0.05 3.24 ±0.03 |

8.00±0.07 4.35±0.04 |

7.04±0.06 4.93±0.04 |

| Fat | 7.56±0.06 | 4.00±0.04 | 3.62±0.03 | 2.80±0.02 |

| Protein(Nx6.25) | 8.08±0.07 | 4.40±0.03 | 4.20±0.04 | 1.70±0.02 |

| p-value | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.05 |

| Components | G/100 g of dry weight | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| a | b | c | |

| Sucrose | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Monosaccharides | 5.19±0.04 | 5.89±0.05 | 4.39±0.04 |

| Titrated acids (in terms of citric acid) | 1.27±0.01 | 1.56±0.01 | 0.94±0.01 |

| Protein (N x 6.25) | 6.51±0.05 | 11.11±0.10 | 1.32±0.01 |

| Fat | 24.22±0.23 | 25.68 ±0.23 | 22.56±0.20 |

| Fibers | 60.23±0.50 | 53.39±0.52 | 68.04±0.65 |

| Mineral substances | 2.06±0.02 | 1.72±0.02 | 2.44±0.02 |

|

Substances capable of reacting with KMnO4: Total Polyphenols |

0.54±0.01 0.28±0.01 |

0.74±0.01 0.28±0.01 |

0.31±0.01 0.28±0.01 |

| p-value | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.05 |

| Components | G/100 g of dry weight | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| a | b | c | |

| Sucrose | 1.40±0.01 | 2.45±0.02 | 0.25±0.01 |

| Monosaccharides | 13.13±0.12 | 15.80±0.17 | 10.20±0.09 |

| Titrated acids (in terms of citric acid) | 3.66±0.03 | 4.20±0.04 | 2.75±0.02 |

| Protein (N x 6.25) | 3.57±0.03 | 6.25±0.06 | 0.63±0.01 |

| Fat | 17.75±0.18 | 19.46±0.20 | 15.87±0.17 |

| Fibers | 53.00±0.54 | 44.81±0.45 | 62.11±0.64 |

| Mineral substances | 2.03±0.02 | 1.60±0.01 | 2.51±0.02 |

|

Substances capable of reacting with KMnO4: Total Polyphenols |

5.53±0.045 3.44± 0.03 |

5.43±0.04 3.20±0.02 |

5.68±0.06 3.71±0.04 |

| p-value | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.05 |

| Components | G/100 g of dry weight | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| a | b | c | |

| Sucrose | 1.41±0.01 | 1.80±0.01 | 0.48±0.01 |

| Monosaccharides | 15.54±0.17 | 17.85±0.19 | 10.00±0.09 |

| Titrated acids (in terms of citric acid) | 5.05±0.05 | 5.95±0.06 | 2.90±0.04 |

| Protein (N x 6.25) | 5.31±0.03 | 7.06 ±0.07 | 1.13±0.01 |

| Fat | 16.18±0.15 | 17.40±0.16 | 13.27±0.12 |

| Fibers | 45.00±0.45 | 37.95±0.40 | 62.63 ±0.65 |

| Mineral substances | 2.38±0.02 | 1.85±0.01 | 3.65±0.04 |

|

Substances capable of reacting with KMnO4: Total Polyphenols |

9.07±0.09 4.81 ±0.05 |

9.14±0.10 5.68±0.07 |

4.94±0.05 2.72±0.03 |

| p-value | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.05 |

| Components | G/100 g of dry weight | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| a | b | c | |

| Sucrose | 1.59±0.01 | 2.00±0.01 | 0.00 |

| Monosaccharides | 22.56±0.24 | 24.00±0.26 | 18.60±0.20 |

| Titrated acids (in terms of citric acid) | 5.29 ±0.04 | 6.25±0.07 | 2.65±0.03 |

| Protein (N x 6.25) | 6.43±0.05 | 8.37±0.09 | 1.05±0.01 |

| Fat | 10.89 ±0.13 | 11.07±0.13 | 10.38±0.15 |

| Fibers | 43.75 ±0.42 | 38.39±0.37 | 58.98±0.58 |

| Mineral substances | 2.19±0.02 | 1.77±0.02 | 3.40±0.03 |

|

Substances capable of reacting with KMnO4: Total Polyphenols |

7.30±0.08 4.81 ±0.05 |

8.15±0.07 5.60±0.06 |

4.94±0.05 2.64±0.03 |

| p-value | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.05 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).