Submitted:

03 November 2025

Posted:

04 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Pistachio Preparation and Extraction

2.2. Cell Culture and Treatments

2.3. Impact of Extracts on Cell Viability and Proliferation

2.4. Impact on Inflammatory and Metabolic Pathways

2.5. RNA Extraction and cDNA Synthesis

2.6. RT-qPCR

3. Results

3.1. Comparative Chemical Results Between the Extracts

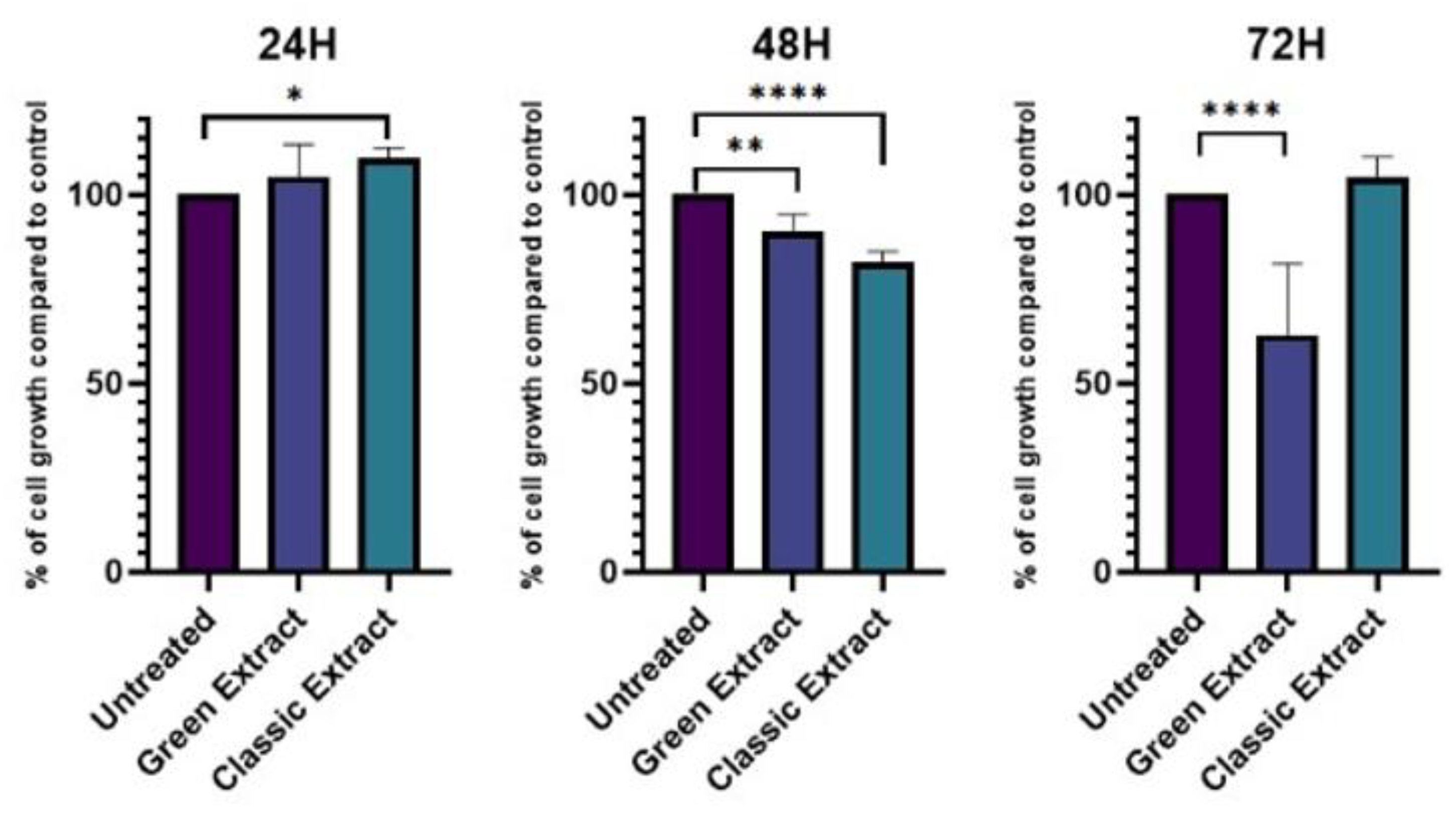

3.2. Metabolic Impact of green and classic extracts

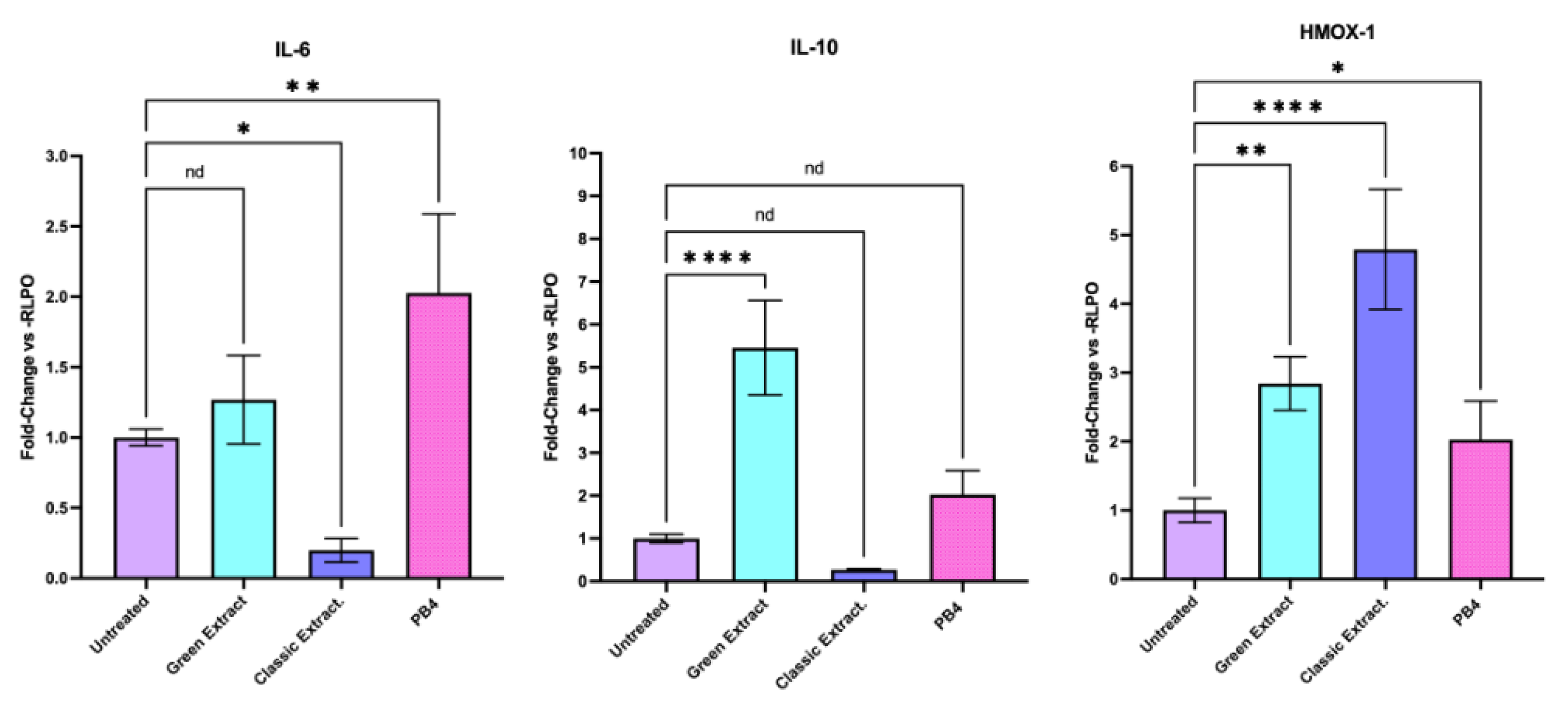

3.3. Impact on Inflammation Pathway

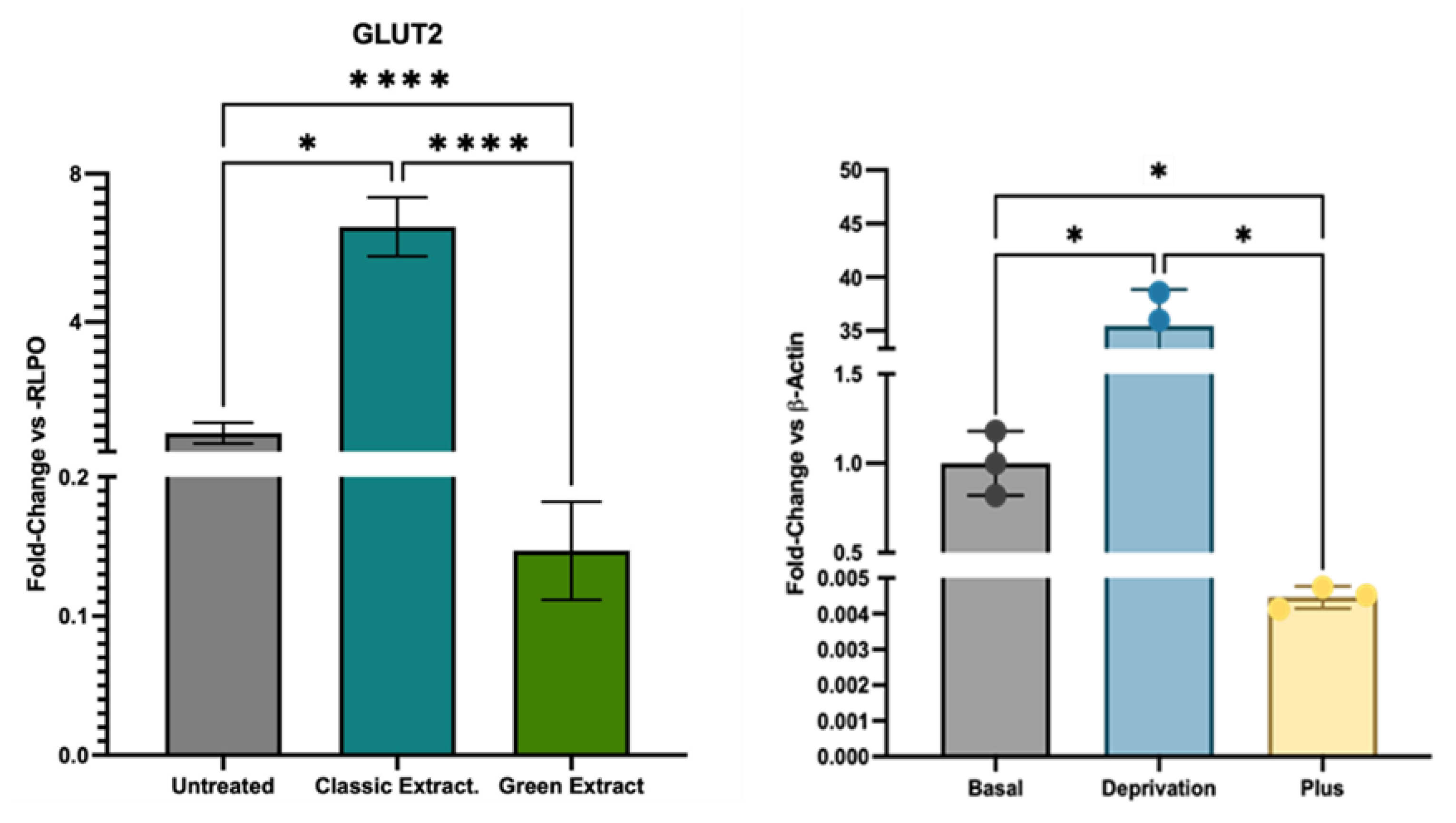

3.4. Impact on Glucose Pathway

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| UAE | Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction |

| GC | Gas Chromatography |

| HPLC | High-Performance Liquid Chromatography |

| qPCR | Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| RNA | Ribonucleic Acid |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic Acid |

| IL-6 | Interleukin 6 |

| IL-10 | Interleukin 10 |

| HMOX-1 | Heme Oxygenase 1 |

| GLUT2 | Glucose Transporter Type 2 |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| DMEM | Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium |

| FBS | Fetal Bovine Serum |

| PBS | Phosphate Buffered Saline |

| MTT | 3-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| ANOVA | Analysis of Variance |

| CV | Coefficient of Variation |

References

- Elakremi, M.; Sillero, L.; Ayed, L.; ben Mosbah, M.; Labidi, J.; ben Salem, R.; Moussaoui, Y. Pistacia Vera L. Leaves as a Renewable Source of Bioactive Compounds via Microwave Assisted Extraction. Sustainable Chemistry and Pharmacy 2022, 29, 100815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballistreri, G.; Arena, E.; Fallico, B. Influence of Ripeness and Drying Process on the Polyphenols and Tocopherols of Pistacia Vera L. Molecules 2009, 14, 4358–4369. Molecules 2009, 14, 4358–4369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grace, M.H.; Esposito, D.; Timmers, M.A.; Xiong, J.; Yousef, G.; Komarnytsky, S.; Lila, M.A. In Vitro Lipolytic, Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Activities of Roasted Pistachio Kernel and Skin Constituents. Food Funct 2016, 7, 4285–4298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashemi, E.; Rezaei, A.; Piravivanak, Z.; Mirani Nezhad, S.; Rashidi Nodeh, H.; Safavi, M. Extraction of Phytosterols from the Green Hull of Pistacia Vera L. Var and Optimization of Extraction Methods. Journal of Medicinal plants and By-products 2025, 14, 252–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodoira, R.; Velez, A.; Rovetto, L.; Ribotta, P.; Maestri, D.; Martínez, M. Subcritical Fluid Extraction of Antioxidant Phenolic Compounds from Pistachio (Pistacia Vera L.) Nuts: Experiments, Modeling, and Optimization. J Food Sci 2019, 84, 963–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beljanski, M.; Beljanski, M.S. Selective Inhibition of in Vitro Synthesis of Cancer DNA by Alkaloids of Beta-Carboline Class. Exp Cell Biol 1982, 50, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saman, S.S.; Hanif, A.; Al-Rawi, S.S.; Ibrahim, A.H.; Iqbal, M.A.; Khalid, S.; Majeed, A.; Mahmood, A.; Ahmad, F. Catharanthus Roseus (L.) G. Don: A Herb with the Potential for Curing Breast Cancer. Next Research 2025, 2, 100218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venditto, V.J.; Simanek, E.E. Cancer Therapies Utilizing the Camptothecins: A Review of in Vivo Literature. Mol Pharm 2010, 7, 307–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoi, V.; Galani, V.; Lianos, G.D.; Voulgaris, S.; Kyritsis, A.P.; Alexiou, G.A. The Role of Curcumin in Cancer Treatment. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, J.-H.; Sethi, G.; Um, J.-Y.; Shanmugam, M.K.; Arfuso, F.; Kumar, A.P.; Bishayee, A.; Ahn, K.S. The Role of Resveratrol in Cancer Therapy. Int J Mol Sci 2017, 18, 2589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheriyan, B.V.; Karunakar, K.K.; Anandakumar, R.; Murugathirumal, A.; kumar, A.S. Eco-Friendly Extraction Technologies: A Comprehensive Review of Modern Green Analytical Methods. Sustainable Chemistry for Climate Action 2025, 6, 100054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandalari, G.; Tomaino, A.; Arcoraci, T.; Martorana, M.; Turco, V.L.; Cacciola, F.; Rich, G.T.; Bisignano, C.; Saija, A.; Dugo, P.; et al. Characterization of Polyphenols, Lipids and Dietary Fibre from Almond Skins (Amygdalus Communis L.). Journal of Food Composition and Analysis 2010, 23, 166–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Detti, C.; dos Santos Nascimento, L.B.; Brunetti, C.; Ferrini, F.; Gori, A. Optimization of a Green Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction of Different Polyphenols from Pistacia Lentiscus L. Leaves Using a Response Surface Methodology. Plants 2020, 9, 1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seifaddinipour, M.; Farghadani, R.; Namvar, F.; Mohamad, J.; Abdul Kadir, H. Cytotoxic Effects and Anti-Angiogenesis Potential of Pistachio (Pistacia Vera L.) Hulls against MCF-7 Human Breast Cancer Cells. Molecules 2018, 23, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reboredo-Rodríguez, P.; González-Barreiro, C.; Cancho-Grande, B.; Simal-Gándara, J.; Giampieri, F.; Forbes-Hernández, T.Y.; Gasparrini, M.; Afrin, S.; Cianciosi, D.; Manna, P.P.; et al. Effect of Pistachio Kernel Extracts in MCF-7 Breast Cancer Cells: Inhibition of Cell Proliferation, Induction of ROS Production, Modulation of Glycolysis and of Mitochondrial Respiration. Journal of Functional Foods 2018, 45, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bongiorno, D.; Musso, N.; Bonacci, P.G.; Bivona, D.A.; Massimino, M.; Stracquadanio, S.; Bonaccorso, C.; Fortuna, C.G.; Stefani, S. Heteroaryl-Ethylenes as New Lead Compounds in the Fight against High Priority Bacterial Strains. Antibiotics (Basel) 2021, 10, 1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonomo, C.; Bonacci, P.G.; Bivona, D.A.; Mirabile, A.; Bongiorno, D.; Nicitra, E.; Marino, A.; Bonaccorso, C.; Consiglio, G.; Fortuna, C.G.; et al. Evaluation of the Effects of Heteroaryl Ethylene Molecules in Combination with Antibiotics: A Preliminary Study on Control Strains. Antibiotics (Basel) 2023, 12, 1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bivona, D.A.; Mirabile, A.; Bonomo, C.; Bonacci, P.G.; Stracquadanio, S.; Marino, A.; Campanile, F.; Bonaccorso, C.; Fortuna, C.G.; Stefani, S.; et al. Heteroaryl-Ethylenes as New Effective Agents for High Priority Gram-Positive and Gram-Negative Bacterial Clinical Isolates. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consoli, G.M.L.; Maugeri, L.; Musso, N.; Gulino, A.; D’Urso, L.; Bonacci, P.; Buscarino, G.; Forte, G.; Petralia, S. One-Pot Synthesis of Luminescent and Photothermal Carbon Boron-Nitride Quantum Dots Exhibiting Cell Damage Protective Effects. Adv Healthc Mater 2024, 13, e2303692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonacci, P.G.; Caruso, G.; Scandura, G.; Pandino, C.; Romano, A.; Russo, G.I.; Pethig, R.; Camarda, M.; Musso, N. Impact of Buffer Composition on Biochemical, Morphological and Mechanical Parameters: A Tare before Dielectrophoretic Cell Separation and Isolation. Transl Oncol 2023, 28, 101599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musso, N.; Bonacci, P.G.; Letizia Consoli, G.M.; Maugeri, L.; Terrana, M.; Lanzanò, L.; Longo, E.; Buscarino, G.; Consoli, A.; Petralia, S. Biofriendly Glucose-Derived Carbon Nanodots: GLUT2-Mediated Cell Internalization for an Efficient Targeted Drug Delivery and Light-Triggered Cancer Cell Damage. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science 2025, 696, 137873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fetting, C. The European Green Deal; Vienna, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Chemicals Strategy - European Commission. Available online: https://environment.ec.europa.eu/strategy/chemicals-strategy_en (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- Chemat, F.; Abert-Vian, M.; Fabiano-Tixier, A.S.; Strube, J.; Uhlenbrock, L.; Gunjevic, V.; Cravotto, G. Green Extraction of Natural Products. Origins, Current Status, and Future Challenges. TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry 2019, 118, 248–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Martín, E.; Forbes-Hernández, T.; Romero, A.; Cianciosi, D.; Giampieri, F.; Battino, M. Influence of the Extraction Method on the Recovery of Bioactive Phenolic Compounds from Food Industry By-Products. Food Chem 2022, 378, 131918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.; Pang, S.; Zhong, M.; Sun, Y.; Qayum, A.; Liu, Y.; Rashid, A.; Xu, B.; Liang, Q.; Ma, H.; et al. A Comprehensive Review of Ultrasonic Assisted Extraction (UAE) for Bioactive Components: Principles, Advantages, Equipment, and Combined Technologies. Ultrason Sonochem 2023, 101, 106646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneider, Y.K.; Jørgensen, S.M.; Andersen, J.H.; Hansen, E.H. Qualitative and Quantitative Comparison of Liquid–Liquid Phase Extraction Using Ethyl Acetate and Liquid–Solid Phase Extraction Using Poly-Benzyl-Resin for Natural Products. Applied Sciences 2021, 11, 10241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza-Pérez, R.J.; Álvarez-Olmedo, E.; Vicente, A.; Ronda, F.; Caballero, P.A. Oil Extraction Systems Influence the Techno-Functional and Nutritional Properties of Pistachio Processing By-Products. Foods 2025, 14, 2722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halwatura, L.M.; Aga, D.S. Broad-Range Extraction of Highly Polar to Non-Polar Organic Contaminants for Inclusive Target Analysis and Suspect Screening of Environmental Samples. Science of The Total Environment 2023, 893, 164707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.; Pang, S.; Zhong, M.; Sun, Y.; Qayum, A.; Liu, Y.; Rashid, A.; Xu, B.; Liang, Q.; Ma, H.; et al. A Comprehensive Review of Ultrasonic Assisted Extraction (UAE) for Bioactive Components: Principles, Advantages, Equipment, and Combined Technologies. Ultrasonics Sonochemistry 2023, 101, 106646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, N.K.; Fitzgerald, H.K.; Fletcher, J.M.; Dunne, A. Plant-Derived Polyphenols Modulate Human Dendritic Cell Metabolism and Immune Function via AMPK-Dependent Induction of Heme Oxygenase-1. Front Immunol 2019, 10, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, D.; Wei, P.; Li, Z.; Wei, R.; Li, H.; Li, S. The Role of P62/Nrf2/Keap1 Signaling Pathway in Lead-Induced Neurological Dysfunction. CNS Neurosci Ther 2025, 31, e70566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erlank, H.; Elmann, A.; Kohen, R.; Kanner, J. Polyphenols Activate Nrf2 in Astrocytes via H2O2, Semiquinones, and Quinones. Free Radical Biology and Medicine 2011, 51, 2319–2327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanner, J. Polyphenols by Generating H2O2, Affect Cell Redox Signaling, Inhibit PTPs and Activate Nrf2 Axis for Adaptation and Cell Surviving: In Vitro, In Vivo and Human Health. Antioxidants (Basel) 2020, 9, 797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pittala, V.; Vanella, L.; Salerno, L.; Romeo, G.; Marrazzo, A.; Di Giacomo, C.; Sorrenti, V. Effects of Polyphenolic Derivatives on Heme Oxygenase-System in Metabolic Dysfunctions. CMC 2018, 25, 1577–1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akkus, E.; Yekedüz, E.; Ürün, Y. Sodium-Glucose Cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) as a Potential Biomarker and Target in Papillary Renal Cell Carcinoma. Clin Genitourin Cancer 2025, 23, 102314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musso, N.; Bonacci, P.G.; Letizia Consoli, G.M.; Maugeri, L.; Terrana, M.; Lanzanò, L.; Longo, E.; Buscarino, G.; Consoli, A.; Petralia, S. Biofriendly Glucose-Derived Carbon Nanodots: GLUT2-Mediated Cell Internalization for an Efficient Targeted Drug Delivery and Light-Triggered Cancer Cell Damage. J Colloid Interface Sci 2025, 696, 137873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, N.; Berridge, M.V. Regulation of Glucose Transport by Interleukin-3 in Growth Factor-Dependent and Oncogene-Transformed Bone Marrow-Derived Cell Lines. Leuk Res 1997, 21, 609–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landaverde-Mejia, K.; Dufoo-Hurtado, E.; Camacho-Vega, D.; Maldonado-Celis, M.E.; Mendoza-Diaz, S.; Campos-Vega, R. Pistachio (Pistacia Vera L.) Consumption Improves Cognitive Performance and Mood in Overweight Young Adults: A Pilot Study. Food Chem 2024, 457, 140211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rock, C.L.; Zunshine, E.; Nguyen, H.T.; Perez, A.O.; Zoumas, C.; Pakiz, B.; White, M.M. Effects of Pistachio Consumption in a Behavioral Weight Loss Intervention on Weight Change, Cardiometabolic Factors, and Dietary Intake. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, K.; Yang, T.; An, L.-Y.; Lin, Y.-Y.; Qi, Y.-X.; Chen, X.-Z.; Sun, D.-L. The Relationship between Pistachio (Pistacia Vera L) Intake and Adiposity: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Medicine (Baltimore) 2020, 99, e21136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warburg, O. The Metabolism of Carcinoma Cells1. The Journal of Cancer Research 1925, 9, 148–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zardo, N.; Will, C.; Santos, A.V.; Galvan, D.; Carasek, E. Exploring HDES as a Sustainable Green Extractant Phase in HF-MMLLE Technique for Assessment of PAHs in Hot Beverages and Evaluation of Potential Dietary Exposure Risks for the Brazilian Population. Food Chem 2025, 493, 145680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shan, Y.; Li, J.; Chen, Y.; Jia, R.; Zeng, X.; Li, Y.; Chen, D.; Li, D. In-Syringe Polypropylene Fiber-Supported Liquid Microextraction Using Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents for the Convenient Analysis of Amphetamine-Type Stimulants in Biological and Environmental Samples. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci 2025, 1263, 124701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pittala, V.; Vanella, L.; Salerno, L.; Romeo, G.; Marrazzo, A.; Di Giacomo, C.; Sorrenti, V. Effects of Polyphenolic Derivatives on Heme Oxygenase-System in Metabolic Dysfunctions. Curr Med Chem 2018, 25, 1577–1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Official Name | Official Symbol | Alternative Titles/Symbols | Detected Transcript | Amplicon Lenght |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ribosomal Protein Lateral Stalk Subunit P0 |

RPLP0 | PRLP0; P0; L10E; RPP0; LP0 | NM_053275 NM_001002 |

68 bp |

| Heme Oxygenase 1 | HMOX-1 | HO-1 | NM_002133 | 161 bp |

| Solute Carrier Family 2 Member 2 |

GLUT2 |

GLUT2; Solute Carrier Family 2 Member 2; Glucose Transporter Type 2, Liver |

NM_000340; NM_001278658; NM_001278659 |

120 bp |

| Interleukin 6 | IL-6 | IL-6 | NM_031168 | 128 bp |

| Interleukin 10 | IL-10 | IL-10 | NM_000572 | 112 bp |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).