1. Introduction

Using dual-task (DT) activity testing, cognitive and motor tasks performed simultaneously, interfere with each other and provide a physiologically relevant indication of overall function. Being critical in DT performance, attention and decision-making are sensitive indicators of cognitive decline in elderly persons [

1,

2] Reduced DT performance in patients with Parkinson’s disease (PD) may be due to cognitive decline, not bradykinesia [

3,

4,

5,

6] but previously the application of DT performance could not readily distinguish between motor and cognitive abilities. It was unclear, whether cognitive impairment after stroke, can be measured at all by DT activity. Studying patients with and without motor impairment, i.e., patients after stroke, may help to address this limitation. We aimed to assess separately movement deterioration and cognitive decline in DT performance after stroke. Changes of mobility of post-stroke (PS) patients were compared between patients, and between patients and normal subjects. The effect of short-term dual task training (STDTT) was studied.

2. Materials and Methods

Study Design

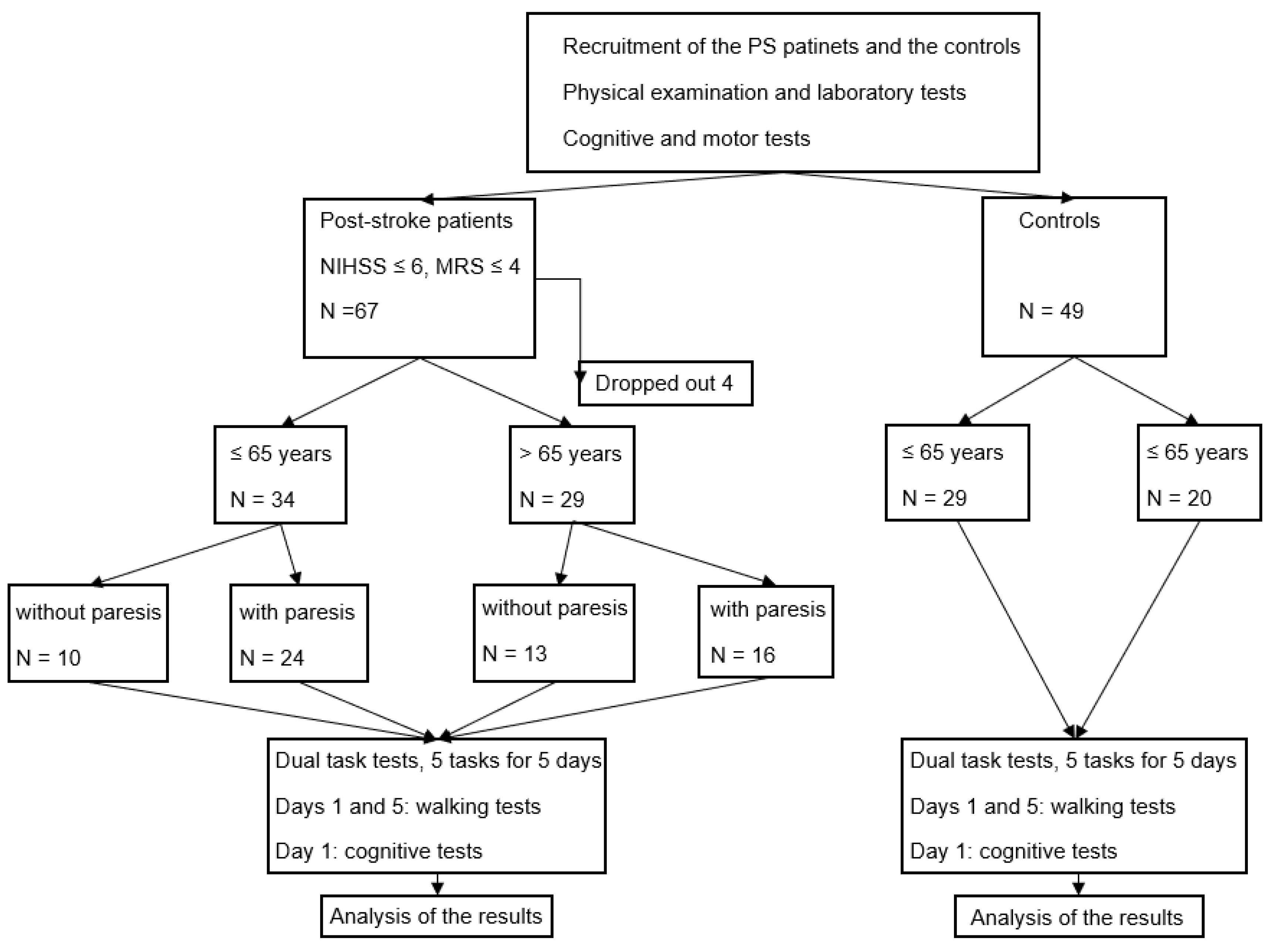

This was a comparative, prospective study. The cognitive-motor DT (CMDT) performance was measured in PS patients and controls to separate the effects of limited movement and age dependent cognitive decline. The effect of a STDTT was determined (

Figure 1).

Participants

The study was not randomized. Patients were recruited sequentially from within Hungary. On arrival, they were assigned to the paretic (P) or non-paretic group (NP) according to their motor assessments during the past 3 years. Sixty-seven PS patients were recruited between 1st of January 2019-and 31st of December, 2023. Four of them fell out leaving 63 patients with PS (F/M: 20/43) (

Figure 1). Forty-nine healthy age-matching controls (F/M: 43/6) were recruited from the patients’ and staff’ relatives.

Inclusion criteria for PS patients: one stroke event, no evidence of dementia (normal Mini Mental State Examination) and ability to stand and walk unaided. Patients with receptive aphasia were excluded. A National Institute of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score of 6 or less, and Modified Rankin Scale (mRS) score of 4 or less were required.

Subjects had suffered mild to severe levels of stroke damage: 51 a brain infarct caused by arterial occlusion, 12 a hemorrhage in the basal ganglia, 1 person a cerebellar hemorrhage. Comorbidities included 45 cases of hypertension, 18 cases of diabetes mellitus, and 7 of atrial fibrillation. PS patients were also divided into paretic (P) and non-paretic (NP) groups, the latter having mild symptoms, like sensory disturbance or mild ataxia.

Assessments

Dual-tasks performances were assessed using a Dividat Senso equipment (HUR, Finland) [

7], an online program regularly checked, serviced and updated by Joris van het Reve Dividat AG, Switzerland, all data recorded automatically by the computer.

Subjects stood on a glass platform (106 x 106 cm) overlying 20 force sensors to measure both sole pressure and body movement. Three sides of the platform were surrounded by railing to support participants. Subjects viewed a test game on a monitor and reacted by leg movements when they perceived at any edge of the screen, where five DT tests were applied and they had to react with four-way leg movements to the objects appearing on the screen. The tests needed attention and decision-making and included a visual and an abstraction task.

The ‘Simple’ task involved selecting a red dot, while the ‘Bird’ test required choosing, a ‘Bird’ from differently colored figures. A red dot and different melodies were combined in the ‘Divided’ task, and the ‘Habitat’ task required assigning different animals to their habitat. In the ‘Target’ task, black balls moved at different speed, and when they reached the target, at a step was required from the participant. The number of correct ‘Hits’ and incorrect ‘Misses’ were recorded. The tasks lasted for one and a half minutes and were repeated on five consecutive days.

The following traditional tests were also applied: Mini Mental State Examination(MMSE) [

8], the Ziehen Ranschburg Word Pairs Test, the Trail MakingTest [

9], the Clock Drawing Test [

10], and the Hamilton Depression Scale Tests [

11], for the quantitation of post-stroke disability, the NIHSS [

12] and mRS [

13]. Upper and lower extremity strength were rated on a 5 points scale from 0 (no movement) to 5 (normal strength). Total points were calculated as a sum of points from every movement of the two limbs. Walking ability was measured, on days 1 and 5 of training, as the distance (m) in 6 minutes, and the time (sec) to walk 10 m on a designated (25 m), covered, smooth and supervised surface. Test supervisors were blinded to the grouping of the participants. The tests took a total of one hour.

Statistical Analysis

Results are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation. The normality of data from the Bird test was determined by the Shapiro-Wilkinson test in OriginPro 2023b (OriginLab Corporation, Northampton, MA, USA). Data from 9 of 12 groups (based on age, presence of paresis and day of examination) were not normally distributed [

14], so the non-parametric Mann-Whitney U-test was used to assess differences of data in patients and control subgroups. Effects of age’ and paresis’ on days 1 and 5 of the experiment were calculated using the Analysis of Variance of Aligned Rank Transformed Data (ArtANOVA) in R v.4.3.2. For post-hoc comparisons of main effects, we used the partial η

2 effect size statistics, interpretating its values as a small effect for 0.01 – < 0.06, as a medium effect for 0.06 – < 0.14, and large effect for ≥ 0.14, following the recommendations of Cohen [

15]. The number of minimal necessary cohort size was determined to be 43 by statistical power analysis using G*Power. The number of actual participants was 63.

3. Results

This section may be divided by subheadings. It should provide a concise and precise description of the experimental results, their interpretation, as well as the experimental conclusions that can be drawn.

Characteristics of PS Participants

Cognitive Tests

According to the MMSE test, no participant showed signs of dementia or severe working memory disturbances.

Walking Tests

None of the six-minute walking test nor the time needed for 10 m walk showed significant changes comparing the initial and 5- days post training results (

Table 1/A,

1/B).

In the non-paretic group, NIHSS and mRS showed a significant difference between the two age groups (p = 0.047, p = 0.0443, respectively). In the paretic group of patients, only mRS showed a significant difference (p = 0.026). There was no significant difference in the extent of upper and lower limb paresis. Results of the 6 min walk test and the 10 m walk test showed no significant change by the end of the training period.

Stroke Assessment

NIHSS values were significantly different between the two age groups of NP patients (p = 0.047), but not of P patients (p = 0.086). Disability scores assessed by the mRS in the PS groups revealed a significant difference between the two age groups both in the NP patients (p = 0.044) and P patients (p = 0.026). Neither the upper (p= 0.30346), nor the lower extremity scores (p = 0.256448) differed between the two age groups (

Table 1/A,

1/B).

3.2.1. Comparisons of the DT Results Between the P or NP PS Patients and Controls

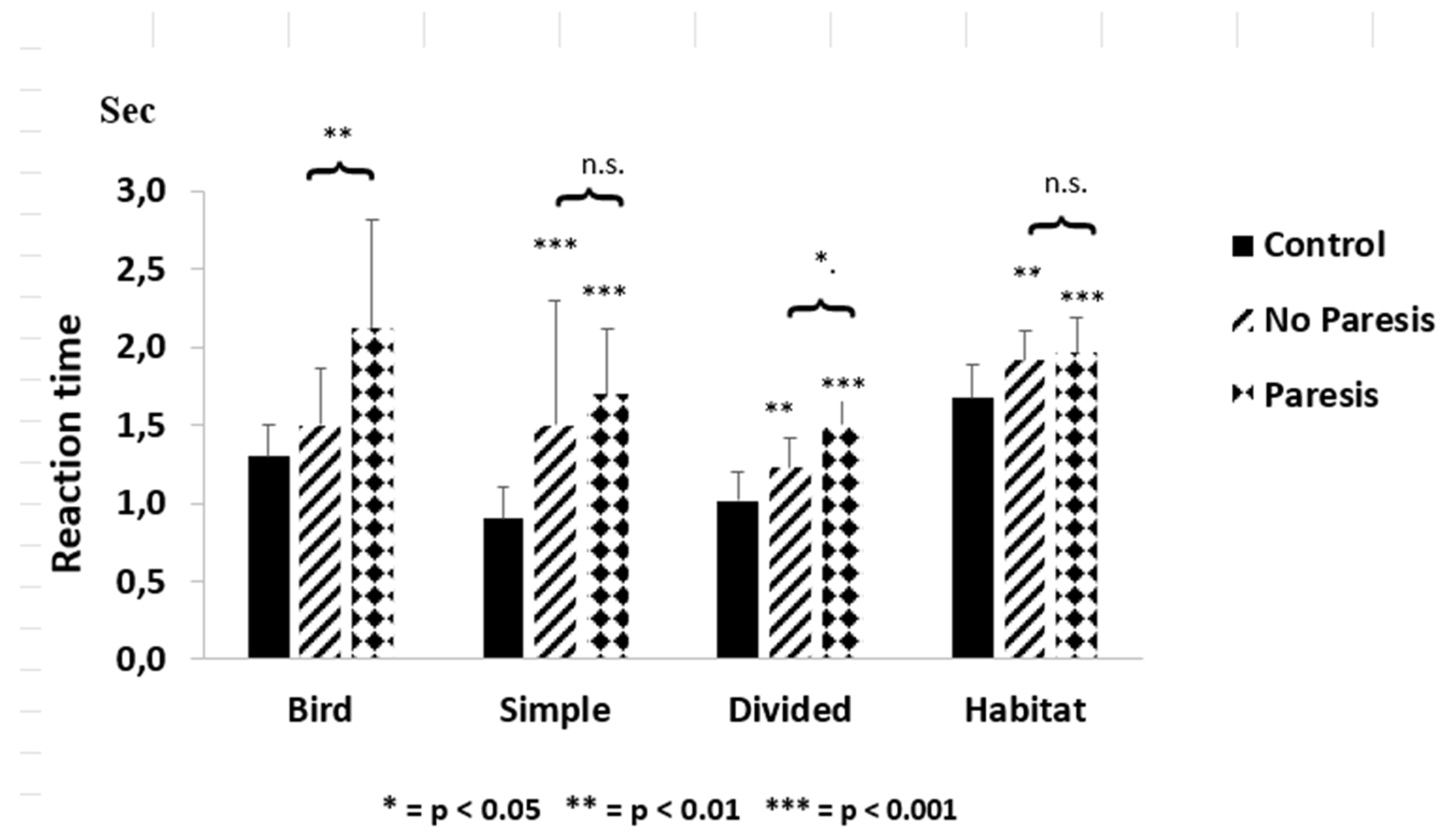

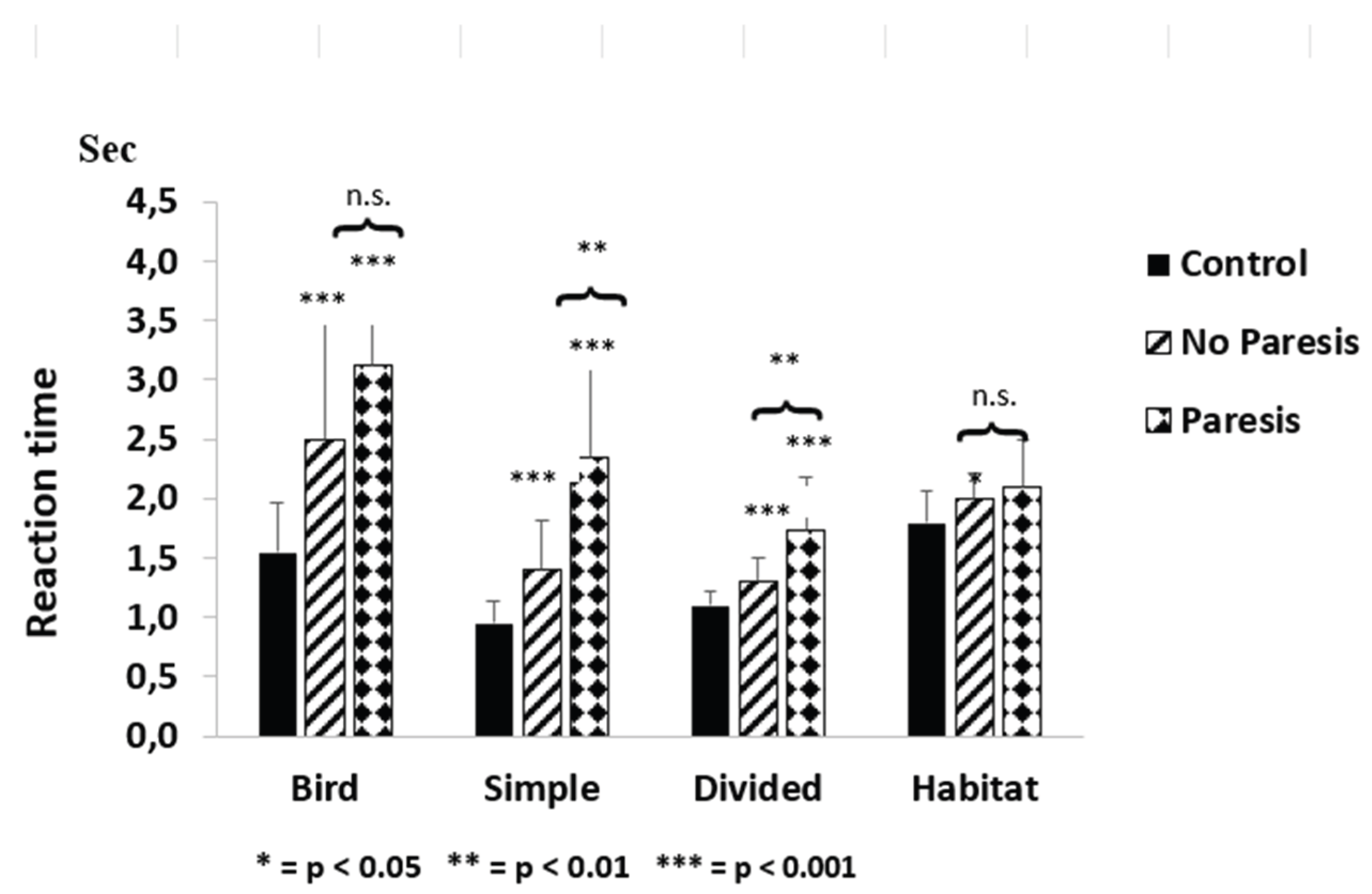

Compared with controls, the reaction times of the NP or P groups were significantly increased showed significant increases for patients at or below 65 years, except for controls vs NP comparisons in the Bird test. Reaction times were significantly increases in the NP and P vs control comparisons in all tests except in the Habitat in the > 65 years age group (

Figure 2,

Figure 3).

Dual-task performances on day one ≤ 65 years

The figure demonstrates the differences between controls and the non-paretic (NP) and paretic (P) patients with post-stroke (PS) ≤ 65 years on the first day of the study. The asterisks (*) indicate significant differences between the controls and the PS patients ≤ 65 years. The clips show the difference between the NP and P groups. With the exception of ‘Bird’, a remarkable delay in reaction time was observed in both the NP and the P groups. Columns represent the mean ± S.D. The columns were labelled as follows: control with black, NP group with oblique striped lines, and P group with dotted patterns. The figure was created by Microsoft Excel.

Dual-task performances on day one ≥ 65 years

The figure depicts the differences between the controls and non-paretic (NP) and paretic (P) patients with post- stroke (PS) > 65 years on the first day of the study. The asterisks (*) indicate t significant differences when the controls are compared with PS patients > 65 years. The clips show the difference between the NP and P groups. A remarkable delay in the reaction time was observed in both the NP and the P groups. There was no interference in ‘Habitat’. Columns represent the mean ± S.D. The columns were labelled as follows: control with black, NP group with oblique striped lines, and P group with dotted patterns. The figure was created by Microsoft Excel.

The decline in DT performance is primarily defined by the deterioration of cognitive function in the NP group with, where there is no limitation of movement. On the first day of testing reaction times in the NP and control groups below 65 years of age were significantly different for three tests: Simple (p < 0.001), Divided (p < 0.01), Habitat (p < 0.01) (

Figure 2).

Reaction times in the NP and control groups above 65 years of age were significantly different in all tests: for Habitat, p < 0.05 (in

Figure 3), this is a non-significant trend), - and for other tests, p < 0.001 (

Figure 3).

Comparing the number of Hits, a significant decrease was noted in the NP and P groups vs. controls in the over 65 groups controls (p < 0.001), and an increase in Misses was detected in the NP (trend) or P (p < 0.001) (

Table 2 and

Table 3).

Table 2 shows the results of the dual-task tests of PS patients and the control group on day 1 compared with the results on day 5 after dual-task training. In the control group and especially in the paretic (P) PS group under 65 years, the values changed significantly on day 5 compared to the data of day one. The non-paretic (NP) PS group showed alteration in two dual-task tests. The results of the ‘Misses’ did not change significantly, except for the P group, however, the decreased value did not reach the controls’ results.

Values represent the mean ± S.D. The asterisks (*) indicate significant differences between the controls, NP, and P PS patients ≤ 65 years of age on the 1st day and all of them on the 5th day. * p < 0.05,** p < 0.01,*** p < 0.001.

Table 3 reflects the results of the dual-task performances of post-stroke patients (PS) and the control group on day 1 compared with the results on day 5 after dual-task training. Results of controls and non-paretic patients (NP) changed in three different dual-task performances by the end of the 5th day. Changes after dual-task training were observed highly significantly in the paretic group of PS patients.

Values represent the mean ± S.D. The asterisks (*) indicate significant differences between the controls, NP, and P PS patients ≥ 65 years of age on the 1st day and all of them on the 5th day. * p < 0.05,** p < 0.01,*** p < 0.001.

Comparisons of the DT Results in the NP and P Patients’ Groups

The effect of paresis on DT performance was estimated by comparing the P and NP groups. At the beginning, the difference was significant for three tests in both age groups. Below age 65 years of age, these were the Bird (p < 0.01), and the Divided (p < 0.05) (

Figure 2). Over 65 the Simple (p < 0.01) and the Divided test were different at (p < 0.01) (

Figure 3).

Although there was also a trend for increase in Hits and decrease in Misses when P and NP patients were compared on the day 5 for the over 65 groups, these were not significantly different (

Table 3).

Comparison of Participants’ DT Test Results on Days One and Five

Significant differences were seen in the DT performances of P and NP PS patients when the 5 days post-training and the first day results were compared. While there was a significant post-training improvement in tests ‘Simple’ and ‘Habitat’ in NP patients under 65 years, the post-training results in the P group improved in the ‘Bird’, ‘Simple’, ‘Hits’, and ‘Misses’ tests (

Table 2).

In P and NP patients over 65 years of age, the P patients improved significantly in more DT tests than NP PS patients after 5 days of dual-task training (

Table 3). The results of NP patients above 65, significantly improved in the Simple (p < 0.05), Divided (p < 0.05), and Targets (Hits: tests (all p < 0.05) tests. For P patients’ results significantly improved in the Bird (p < 0.01), Simple (p < 0.001), Divided (p < 0.05), and Target (Hits: p < 0.05) tests (

Table 3).

4. Discussion

The novelty of our study was comparison of NP and severely affected P PS patients to assess the influence of paresis, age and training before and after training. Cognitive decline was indicated by the reduced DT performances in PS patients, especially when NP participants and controls were compared. The importance of paresis in CMDT tests was apparent in both PS age groups, confirmed by comparing P and NP PS patient using the ArtAnova analysis.

The importance of paresis in the outcome of CMDT tests was apparent in both PS age groups, and confirmed by comparing NP and P PS patients using the ArtAnova analysis. Older patients without motor limitations showed a greater decline in DT performances.

The impact of Paresis

The effect of paresis does not dominate over cognitive decline in DT performance,

Previous studies have reported a poor performance on CMDT tests in PS patients with mild motor impairment, and have noted the impact of paresis with the change in walking speed [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23]. However, evaluation of walking is a complex task, influence by balance [

24] and training [

25] and reduced walking speed in DT testing correlates with decline in cognitive ability from mild (MCI) to severe cognitive impairment [

26,

27]. Consequently, paresis cannot be measured directly by walking, but is only an indirect indicator of paresis [

23]. Conversely, it is hard to define, especially in P groups, the extent to which the two factors are responsible for the deterioration of DT performance. since cognitive impairment tends to increase in parallel with the extent of motor damage [

28]. In the present work, paresis was demonstrated by the difference between the NP and P patients (

Figure 2 and

Figure 3), confirmed by the ArtAnova analysis on the first day of testing. There was some reduction by SDTT suggesting a learning process, and that the paresis does not play an important role in DT performance.

The Impact of Cognitive Function

It has been reported that elderly persons with MCI performed worse in DT tests than those without it [

27,

28,

29,

30,

31], although training and prioritization improved DT performance [

32,

33]. In contrast, the decline in DT performance may indicate cognitive impairment in the early stages of PD [

3,

6]. Similarly, the non-walking DT test in the upper arm repetitive elbow flexion-was useful to detect cognitive decline [

34].

Reduced DT performance in NP patients allowed us to predict cognitive decline in PS patients without paresis and in older subjects (

Figure 2 and

Figure 3). DT tests assessed by Dividat represent a simple, objective test, mainly influenced by attention and decision making. These factors deteriorate with advanced age when two tasks are performed simultaneously, since cognitive demand is increased during DT performance. These two aspects of CMDT test cannot be separated, but the DT tests provide an overall view of cognitive function. They reveal attention deficit increases with advanced age, when two tasks performed simultaneously [

35,

36]. Cognitive demand is increased during DT performance, leading to a worsening of the outcome. These two parts of CMDT test cannot be separated, but the DT tests provide an invaluable overall view of cognitive function in the absence of movement impairment.

The elevated number of ‘Mistakes’- indicating cognitive decline- could not be influenced by training. According to our statistical analysis, the measure of ‘Mistakes’ was independent of paresis and highly dependent on age. An increase in ‘Mistakes’ was observed neither in the NP groups under age 65, nor in the control subjects (

Table 2,

Table 3). These results are in contradiction with previous results [

37], although our result confirms the observation that cognitive DT test errors increased only in PS patients but not in controls [

38].

The Impact of Training

A favourable effect of DT training has been observed on walking speed, stride length, balance, and cognitive function in normal elderly people [

2,

24,

25,

39], and in PS patients [

40,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45]. Here, DT trainings applied twice a week, for several weeks. Our data suggest that shorter training periods on consecutive days can be effective, as it reduces the delay of CMDT performances. The effect of training was particularly pronounced in the patients with paresis, although the walking test did not show an improvement after short duration training.

Our data suggest that even a shorter training on consecutive days can be effective, as it reduces the delay of CMDT performances. In this study, the effect of training was particularly pronounced in the patients with paresis, although the walking test did not show an improvement after short duration training.

Limitations of the Study

This study did not use classical randomization but patients were divided into different groups according to their symptoms. The long- term recruitment and the strict inclusion criteria, the validity of the data was less affected. Blinding was only possible for psychological and exer-gaming tests. A short duration training could have beneficially biased DT performances.

5. Conclusions

Motor damage significantly contributed to the decrease of DT performances in PS patients over and below 65 years. Based on the significant differences between the DT performances of the NP and control groups, some cognitive deterioration in PS patients can also be inferred, with poorer performance in older patients. These results suggest the presence of attention and decision-making deficits in PS patients. Training produced improvements in the PS patients, with the greatest effect in the P group.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, investigation, writing-original draft preparation, J.M.; data curation, execution of statistical analysis, O.K; writing-review and editing, B.K.; study supervision, T.W.S. All authors read, provided feedback, and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

No funding was required.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical approval No 76-1-6/2019 for the study was granted by the Regional Ethics Committee of the Aladár Petz County Hospital Győr, Hungary.

Informed Consent Statement

We obtained signed informed consent from each patient at the beginning of the trials according to the Helsinki Declaration. The study was listed on the ISRCTN registry with study ID ISRCTN12362945 (www-isrctn.com/ISRCTN12362945). The study was designed and directed by coauthor JM.

Data Availability Statement

Archiving of research data was supported by the Data Repository Platform of the Hungarian Research Network (HUN-REN ARP) under the ARP Ambassador program. The research data are accessed in the ARP Data Repository via this link:

https://hdl.handle.net/21.15109/ARP/LZXB8R. .

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Chen, I.C.; Chuang, I.C.; Chang, K.C.; Chang, C.H.; Wu, C.Y. Dual task measures in older adults with and without cognitive impairment: response to simultaneous cognitive-exercise training and minimal clinically important difference estimates. BMC Geriatrics. 2023, 23, 663–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wisniowska, J.; Lojek, E.; Olejnik, A.; Chabuda, A. The characteristics of the reduction of interference effect during dual-task cognitive-motor training compared to a single task cognitive and motor training in elderly: A randomized controlled trial. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2023, 20, 1477–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szögedi, D.; Stone, T.W.; Dinya, E.; Málly, J. Dual-task performance testing as an indicator of cognitive deterioration in Parkinson’s disease: A pilot study. J. Psychiatry Psychiatric. Disord. 2022, 7, 104–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, H.; Ekman, U.; Rennie, L.; Peterson, D.S.; Leavy, B.; Franzén, E. Dual-task effects during a motor-cognitive task in Parkinson’s disease: Patterns of prioritization and the influence of cognitive status. Neurorehab. Neurol. Repair. 2021, 35, 356–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Yang, T.; Shang, H. The impact of motor cognitive dual-task training on physical and cognitive functions in Parkinson’s disease. Brain Sci. 2023, 13, 437–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.P.; Lin, I.I.; Chiou, W.D.; Chang, H.C.; Chen, R.S.; Lu, C.S.; Chang Y., J. The executive-function-related cognitive-motor dual task walking performance and task prioritizing effect on people with Parkinson’s disease. Healthcare (Basel). 2023, 11, 567–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altorfer, P.; Adcock, M.; de Bruin, E.D.; Graf, F.; Giannouli, E. Feasibility of cognitive-motor exergames in geriatric impatient rehabilitation: A pilot randomized controlled study. Front. Age Neurosci. 2021, 13, 739948–739985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Folstein, M.F.; Folstein, S.E.; McHugh, P.R. Mini-Mental State: A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J. Psychiatric Res. 1975, 12, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reitan, R.M. Trail Making Test: Manual for administration and scoring. Reitan Neuropsychology Laboratory: Tempe, AZ: USA Corpus ID:141448957 1992.

- Sunderland, T.; Hill, JL.; Mellow, A.M.; Lawlor, B.A.; Gundersheimer, J.; Newhouse, P.A.; Grafman, J.H. Clock drawing in Alzheimer’s disease: a novel measure of dementia severity. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 1989, 7, 725–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamilton, M. A rating scale for depression. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 1960, 23, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, H.P.; Davis, P.H.; Leira, E.C.; Chang, K.C.; Bendixen, B.H.; Clarke, W.R.; Woolson, R.F.; Hansen, M.D. Baseline NIH Stroke Scale score strongly predicts outcome after stroke: A report of the Trial of Org 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment (TOAST). Neurology. 1999, 53, 126–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banks, J.L.; Marotta, C.A. Outcomes validity and reliability of the modified Rankin Scale: implications for stroke clinical trials: a literature review and synthesis. Stroke 2007, 38, 1091–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagenmakers, E.J.; Brown, S. Linear relation between the mean and the standard deviation of a response time distribution. Psych. Rev. 2007, 114, 830–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioural sciences. 2 nd ed., 1988, 286-281.

- Baek, C.Y.; Yoon, H.S.; Kim, H.D.; Kang, K.Y. The effect of the degree of dual-task interference on gait, dual-task cost, cognitive ability, balance and fall efficacy in people with stroke: A cross-sectional study. Medicine (Baltimore) 2021, 100, e26275–e97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deblock-Bellamy, A.; Lamontagne, A.; Blanchette, A.K. Cognitive-locomotor dual-task interference in stroke survivors and the influence of the tasks: A systematic review. Front. Neurol. 2020, 11, 882–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, H.; Lang, S.; Zheng, Y.; Huang, D.; Gao, S.; Zheng, M.; Zhao, B.; Yiming, Z.; Qui, Y.; Lin, Q.; et al. Motor dual-tasks for gait analysis and evaluation in post-stroke patients. J. Vis. Exp. 2021, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pumpho, A.; Chaikeeree, N.; Saengsirisuwan, V.; Boonsinsukh, R. Selection of the better dual-timed up and go cognitive task to be used in patients with stroke characterized by subtraction operation difficulties. Front. Neurol. 2020, 11, 262–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plummer – D’Amato, P.; Altmann, L.J.P. Relationship between motor function and gait-related dual-task interference after stroke: A pilot study. Gait Posture. 2012, 35, 170–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plummer, P.; Eskes, G.; Wallace, S.; Giuffrida, C.; Fraas, M.; Campbell, G.; Clifton, K.L.; Skidmore, E.R. Cognitive-motor interference during functional mobility after stroke: state of the science and implications for future research. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2013, 94, 2565–2574 e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Yahya, E.; Dawes, H.; Smith, L.; Dennis, A.; Howells, K.; Cockburn, J. Cognitive motor interference while walking: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2011, 35, 715–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muci, B.; Keser, I.; Meric, A.; Karatas, G.K. What are factors affecting dual-task gait performance in people after stroke? Physiother. Theory. Pract. 2022, 38, 621–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Barros, G.M.; Melo, F.; Domingos, J.; Oliveira, R.; Silvia, L.; Fernandes, J.B.; Silva, L.; Fernandes, J.B.; Godinho, J. The effect of different types of dual tasking on balance in healthy older adults. J. Pers. Med. 2021, 11, 933–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silsupadol, P.; Lugade, V.; Shumway-Cook, A.; van Donkelaar, P.; Chou, L.S.; Mayr, U.; Woollacott, M.H. Training-relate changes in dual-task walking performance of elderly persons with balance impairment: A double-blind, randomized controlled trial. Gait Posture 2009, 29, 634–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez, F.; Gutiérrez, M. Dual-task gait as a predictive tool for cognitive impairment in older adults: A systematic review. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2021, 13, 769462–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Q.; Tian, C.; Tseng, B.; Zhang, B.; Huang, S.; Jin, S.; Mao, J. Gait change in dual task as a behavioural marker to detect mild cognitive impairment in elderly persons: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2020, 101, 1813–1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einstad, M.S.; Saltvedt, I.; Lydersen, S.; Ursin, M.H.; Munthe-Kaas, R.; Ihle-Hansen, H.; Knapskog, A.B.; Askim, T.; Beyer, M.K.; Naess, H.; et al. Association between post-stroke motor and cognitive function: a cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatr. 2021, 21, 103–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brustio, P.R.; Magistro, D.; Zecca, M.; Rabaglietti, E.; Liubicich, M.E. Age-related decrements in dual-task performance: Comparison of different mobility and cognitive tasks. A cross-sectional study. PLOS One. 2017, 12, e0181698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahureksa, L.; Najafi, B.; Saleh, A.; Sabbagh, M.; Coon, D.; Mohler, J.; Schwenk, M. The impact of mild cognitive impairment on gait and balance: a systematic review and meta-analysis of studies using instrumented assessment. Gerontology 2017, 63, 67–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos-Magdaleno, M.; Pereiro, A.; Navarro-Pardo, E.; Juncos-Rabadán, O.; Facal, D. Dual-task performance in old adults: cognitive, functional, psychosocial and socio-demographic variables. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2022, 34, 827–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, D.K.; Jang, T.S.; Kwon, J.W. Effects of dual-task training on gait parameters in elderly patients with mild dementia. Healthcare (Basel) 2021, 9, 1444–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Park, S. Effects of a priority-based dual task on gait velocity and variability in older adults with cognitive impairment. J. Exerc. Rehabil. 2018, 14, 993–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toosizadeh, N.; Najafi, B.; Reiman, E.M.; Mager, R. M.; Veldhuizen, J.K.; O’Connor, K.; Zamrini, E.; Mohler, J. Upper-extremity dual-task function: An innovative method to assess cognitive impairment in older adults. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2016, 8, 167–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhaeghen, P.; Steiz, D.W.; Sliwinski, M.J.; Cerella, J. Aging and dual-task performance: A meta-analysis. Psychol. Aging 2003, 18, 443–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Künstler, E.C.S.; Penning, M.D.; Napiórkowski, N.; Klingner, C.M.; Witte, O.W.; Müller, H.J.; Bublak, P.; Finke, K. Dual-task effects on visual attention capacity in normal aging. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 1564–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bech, S.R.; Kjeldgaard-Man, L.; Sirbaugh, M.C.; Egholm, A.F.; Mortensen, S.; Laessoe, U. Attentional capacity during dual-task balance performance deteriorates with age before the sixties. Exp. Aging Res. 2022, 48, 86–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; He, C.; Pang, M.Y.C. Dual-task mobility among individuals with chronic stroke: changes in cognitive-motor interference patterns and relationship to difficulty level of mobility and cognitive tasks. Eur. J. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2018, 54, 526–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mundada, P.H.; Dadgal, R.M. Comparison of dual task training versus aerobics training in improving cognition in healthy elderly population. Cureus 2022, 14, e29027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spanò, B.; Lombardi, M.G.; de Tollis, M.; Szczepanska, M.A.; Ricci, C.; Manzo, A.; Giuli, S.; Polidori, L.; Griffini, I.A.; Adriano, F. Effect of dual-task motor-cognitive training in preventing falls in vulnerable elderly cerebrovascular patients: A pilot study. Brain Sci. 2022, 14, 168–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, P.; Hutzler, Y.; Ratmansky, M.; Treger, I.; Dunsky, A. A preliminary study of dual-task training using virtual reality: Influence on walking and balance in chronic poststroke survivors. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2019, 28, 1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kannan, L.; Vora, J.; Bhatt, T.; Hughes, S. L Cognitive -motor exergaming for reducing fall risk in people with chronic stroke: A randomized controlled trial. NeuroRehabilitation 2019, 44, 493–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, R.; Li, X.; Zhu, Z.; Li, T.; Zhao, M.; Mo, L.; Li, W.; Xi, X.; Huang, P.; Gong, W. Effects of dual-task training in patients with post-stroke cognitive impairment: A randomized controlled trial. Front. Neurol. 2022, 13, 1027104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.H.; Kim, B.R.; Han, E.Y.; Kim, S.M. The effect of dual-task training on balance and cognition in patients with subacute post-stroke. Ann. Rehabil. Med. 2015, 39, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plummer, P.; Villalobos, R.M.; Vayda, M.; Moser, M.; Johnson, E. Feasibility of dual-task gait training for community-dwelling adults after stroke: a case series. Stroke Res. Treat. 2014, 2014, 538602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).