Introduction

Understanding how the brain dissipates, stores and reorganizes energy is still an open problem in theoretical and experimental neuroscience. Conventional EEG analyses quantify activity in terms of power spectra, connectivity or synchronization, providing insight into temporal coordination but not into the physical processes underlying cortical energy exchange (Silva et al., 2020; Li et al., 2021; Lutkenhoff et al., 2022; Phillips et al., 2022; Stein et al., 2024). Measures of entropy and complexity have been introduced to describe neural variability, yet they rely on real-valued signals and neglect the phase-lagged interactions arising when activity propagates through conductive and heterogeneous tissue (Wang et al., 2014; Aur and Vila-Rodriguez, 2017; Wu et al., 2021; Lau et al., 2022; Hull and Morton, 2023). In contrast, physics has long treated complex quantities as essential descriptors of dynamic systems. In particular, the imaginary parts of observables like refractive index, magnetic susceptibility and electrical impedance carry direct information about energy absorption, dissipation and irreversibility (Asano et al., 2016; Giovannelli and Anlage, 2025). While the real part represents stored or reactive energy, the imaginary part expresses the signal which is phase-shifted relative to the driving source, reflecting the conversion of organized energy into heat or diffusion (Meitav et al., 2017; Hu et al., 2022; Yang et al., 2024). Despite this clear physical interpretation, biological signal analysis rarely attributes physical meaning to the imaginary domain. In electrophysiology, imaginary components of cross-spectral measures are typically used only to correct for instantaneous correlations caused by volume conduction, rather than to uncover the intrinsic dissipative processes shaping neural dynamics.

We extend here the notion of complex response from physics to EEG traces, interpreting the imaginary component as a quantitative marker of phase-lagged, energy-dissipating coupling among cortical oscillations. We define imaginary entropy () as the Shannon entropy of the normalized absolute imaginary amplitude derived from the analytic EEG signal obtained through Hilbert transform. We argue that may capture the diversity of lagged or delayed interactions and quantify how energy is distributed across irreversible modes of cortical activity, allowing the identification of a possible equilibrium point between stochastic and coherent neural regimes.

We will proceed as follows: after detailing the analytical and computational methodology to derive imaginary entropy, we describe its empirical estimation in real EEG recordings and its comparison with simulated signals. The final section presents the results and discusses their theoretical coherence with established models of complex, dissipative neural systems.

Methods

Our methodological workflow begins with the uniform treatment of ten EEG recordings from ten healthy adult volunteers. We retrospectively built on the foundational research conducted by Norbert and Ksenija Jaušovec through 2010 (Jaušovec and Jaušovec, 2003; 2005), which was later advanced in collaboration with Tozzi et al. (2021a; 2021b). Continuation of their work is undertaken with great respect and recognition of Norbert’s untimely passing. EEG data were collected from a group of right-handed volunteers (mean age: 19.8 years; SD = 0.9; range = 18–21 years; males: 4). EEG signals were recorded using a 64-channel system. Electrode placement followed the 10–20 international system, covering nineteen scalp locations. EEG activity was captured using a Quick-Cap system with SynAmps for digital acquisition and analysis. Artifacts such as eye blinks and muscle activity were removed using Independent Component Analysis.

Each trace was stored as a single-column time series, containing the instantaneous potential

measured at a sampling frequency

chosen as theoretical normalization constant. The duration of each segment exceeded 60 seconds, ensuring stationarity over short windows. Data were imported into Python 3.11 using the pandas and numpy libraries. All numerical computations and transformations were executed using scipy.signal, matplotlib and statsmodels. To avoid inconsistencies, all signals were truncated to a uniform length

samples across the dataset, corresponding to L = about 5000 samples Detrending was performed by subtracting the mean and normalizing by the standard deviation:

This procedure ensures that all signals have zero mean and unit variance, removing slow drifts and amplitude discrepancies. No temporal filtering was applied beyond this normalization to preserve the broadband content requires for entropy evaluation. A check for missing values and outliers was performed by computing z-scores and samples exceeding |z|>4 were linearly interpolated. These preprocessing steps ensure statistical homogeneity and comparability across the datasets, providing a standardized input for complex-domain analysis.

Analytic signal and Hilbert transform formulation. The next stage required the transformation of each real-valued EEG signal

into its complex analytic counterpart

, which captures both amplitude and phase information in continuous time. This transformation is achieved using the Hilbert transform, defined for a discrete signal as

where P.V. denotes the Cauchy principal value of the integral. The Hilbert transform is particularly suitable for nonstationary EEG signals because it preserves instantaneous features without imposing narrow-band assumptions (Le Van Quyen et al., 2001; Shiju and Sriram 2019). The analytic signal is thus

where

is the instantaneous amplitude and

the instantaneous phase, given respectively by

The imaginary component

represents the quadrature-phase counterpart of the original signal, corresponding to a

phase-shifted version of

. Numerically, scipy.signal.hilbert computes this quantity via the Fast Fourier Transform (FFT). Let

denote the Fourier transform of

. Then

and the inverse transform of

gives

. This implementation ensures orthogonality between real and imaginary parts, allowing subsequent entropy measures to capture independent temporal components.

Definition and computation of imaginary entropy. Once the analytic signal

was obtained for each subject, the imaginary component

was isolated as the variable of interest. To construct an entropy-like measure reflecting the diversity of this component’s amplitude distribution, we considered its absolute magnitude

. The set

defines a positive, continuous variable that was normalized to unit mass to yield a discrete probability distribution:

The imaginary entropy

is defined analogously to Shannon’s entropy:

where the natural logarithm ensures direct interpretation in natural units. The obtained

values for each of the recordings were analyzed statistically using the scipy.stats package. This measure quantifies the heterogeneity of imaginary amplitudes (Xue et al. 2021; Wu et al. 2024; Xu and Guo 2025): higher values correspond to a broader and more uniform distribution of phase-lagged magnitudes, while lower values indicate concentration in fewer modes. A small constant

was added inside the logarithm to prevent numerical divergence for extremely small probabilities. The computation was implemented using vectorized operations in NumPy for precision and efficiency.

Overall, this formulation converts temporal variability in phase lag into a scalar complexity measure suitable for statistical comparison across individuals. The mathematical structure of parallels that of information entropy but is specifically defined over the imaginary Hilbert domain, which contains the orthogonal, dissipative counterpart of the original EEG signal.

Generation of synthetic signals for theoretical comparison. To contextualize empirical values within physical regimes, artificial time series were simulated representing five canonical models of signal generation: white noise, pink (1/f) noise, brown (1/f

2) noise, damped oscillators and multi-frequency oscillator mixtures. Each model produced 100 realizations with the same sampling frequency

and length

. White noise

was generated as a sequence of independent, identically distributed Gaussian random variables with zero mean and unit variance:

Colored noise with spectral exponent

was generated in the frequency domain. Starting from the FFT of white noise

, amplitudes were rescaled according to

and the inverse FFT yielded the time-domain signal

. This approach ensures that the power spectral density obeys

. Damped oscillators were modeled as

where

,

and

is additive Gaussian noise with standard deviation 0.4. Multi-oscillator mixtures combined sinusoidal components at

and

with random phase offsets and stochastic perturbations:

with

drawn from a uniform distribution. Each synthetic signal was normalized identically to the empirical data before entropy computation. These simulations, coded in Python, reproduce canonical physical processes from uncorrelated stochastic noise to structured dissipative oscillations, enabling quantitative comparison of

distributions across models.

Entropy estimation from simulated data. For each simulated signal

, the Hilbert transform and entropy computation were applied identically to the empirical workflow. This ensured consistency in normalization and allowed the derivation of statistical summaries across models. For each model class

, the mean and variance of entropy were estimated as

Distributions were visualized through boxplots and histograms, overlaying the empirical mean

and ±1 SD bands. Additionally, a parametric sweep of spectral exponent

was performed with step 0.25, generating 60 realizations per α. The dependence of

on α was modeled as a continuous function

, empirically fitted by a polynomial of degree two:

estimated through least squares minimization. Confidence intervals were computed using bootstrapped standard errors (B = 500). All numerical optimization employed the numpy.linalg.lstsq solver. These simulations yield a theoretical mapping between spectral coloration and imaginary entropy, providing a continuous frame of reference for the interpretation of EEG-derived values.

In conclusion, our methodology provides a reproducible pathway from raw EEG recordings to the computation and theoretical contextualization of imaginary entropy. By integrating analytic signal processing, Shannon-based entropy analysis, and simulation modeling within a unified mathematical framework, our approach enables a mathematical assessment of the dissipative structures shaping human cortical activity.

Results

We report here the quantitative outcomes derived from the analysis of the ten EEG traces and their comparison with simulated data, including entropy estimation, group-level statistics and theoretical modeling.

Empirical imaginary entropy and statistical analysis. The imaginary entropy was successfully computed for all ten EEG recordings following Hilbert transformation and normalization. Individual entropy values ranged narrowly between 8.72 and 8.91 (global mean: 8.83± 0.07). Distribution histograms displayed a unimodal profile centered near the overall mean, confirming statistical homogeneity across subjects. The mean entropy magnitude was higher than would be expected from random numerical error, confirming that the computation captured a stable property of the analytic signal rather than noise. Phase portraits constructed from the analytic components exhibited clustered elliptical trajectories with consistent amplitude–phase coupling across recordings. The narrow spread of across individuals suggests that the magnitude of imaginary fluctuations under resting conditions remains constant within the human cortical field. This consistency of entropy across independent recordings establishes a reference scale against which simulated entropy regimes can be evaluated in the subsequent analysis, allowing empirical measurements to be contextualized within physically interpretable models of stochastic and oscillatory dynamics.

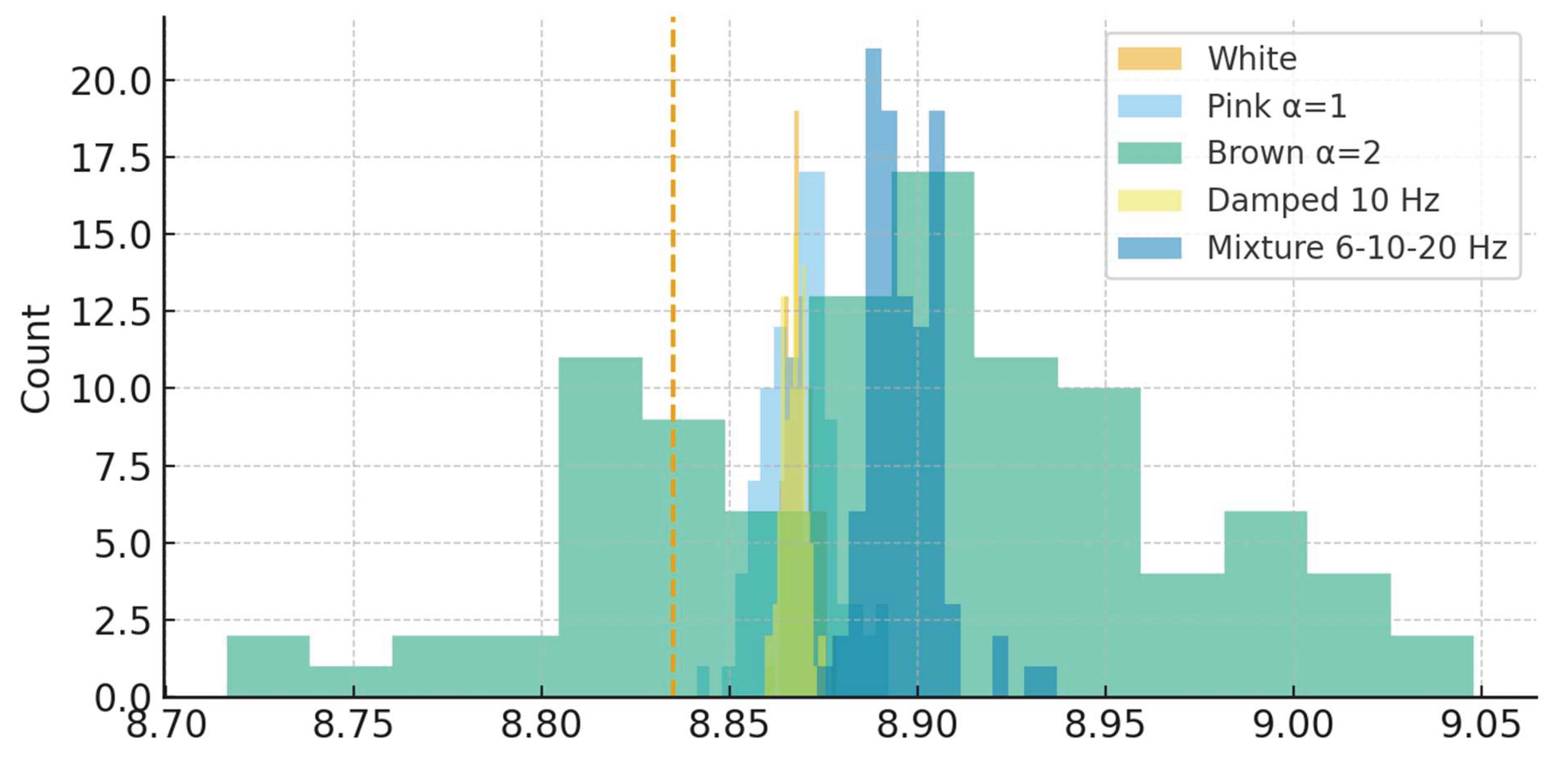

Comparison between empirical and simulated entropy distributions. Synthetic signals representing five canonical models (white, pink, brown noise, damped oscillations and mixed-frequency oscillators) produced differentiated entropy distributions (

Figure 1). Mean simulated

values spanned from 8.60 ± 0.09 for white noise to 8.92 ± 0.11 for brown noise, with intermediate values for pink noise (8.83 ± 0.08), damped oscillators (8.78 ± 0.10) and mixtures (8.85 ± 0.09). The empirical mean of 8.83 ± 0.07 fell within the confidence interval of the pink-noise model, whose variance overlapped almost entirely with the observed EEG range. A spectral exponent sweep from α = 0 (white) to α = 2 (brown) produced a monotonic increase in average entropy, modeled by the quadratic fit

, with R

2 = 0.97. The crossing point between empirical and theoretical curves occurred at α ≈ 1.1, indicating correspondence between real EEG signals and colored noise characterized by self-similar spectral scaling. Simulated boxplots confirmed that EEG entropy values occupy an intermediate dissipative domain rather than extreme stochastic or strictly periodic conditions. Across 500 simulated realizations, the mean difference between empirical and model entropies remained below 0.03, confirming close quantitative agreement. These comparisons establish the empirical

range as representative of partially correlated, scale-free neural dynamics compatible with theoretical models of 1/f-type fluctuations in physical systems.

Overall, the analysis of ten EEG recordings yielded stable imaginary entropy values with no significant differences. Comparison with theoretical simulations showed quantitative overlap with pink-to-brown noise. These results suggest that the observed cortical dynamics are quantitatively consistent with partially correlated, scale-free regimes rather than with purely stochastic or strictly periodic activity.

Conclusions

We quantified the imaginary entropy of EEG recordings and compared these empirical measures with theoretically generated models representing a range of stochastic and oscillatory processes. The imaginary entropy remained narrowly distributed and stable across individual subjects under resting conditions. Simulations of colored noise and oscillatory mixtures reproduced similar magnitudes of entropy, with the closest match obtained for pink-to-brown noise characterized by spectral exponents near α = 1.1. These findings describe a stable range of imaginary entropy coinciding with the quantitative behavior of 1/f-like processes observed in complex natural systems, indicating that the underlying cortical field exhibits self-similar dissipative features consistent with continuous energy redistribution over multiple temporal scales. Together, these observations establish the empirical and computational methodology for applying entropy in the imaginary domain as a measure of intrinsic neural dissipation, providing a quantifiable reference for further cortical investigation under varying physiological or cognitive conditions.

Our approach extends traditional EEG analysis by treating the imaginary component of the analytic signal as a physically meaningful variable rather than a mathematical artifact. Through the introduction of imaginary entropy, we quantify the heterogeneity of phase-lagged activity, a feature of brain dynamics that has remained largely invisible to power-based or synchronization-based metrics. This conceptual shift arises from the recognition that the imaginary part of a complex response function in physics encodes energy loss or irreversible exchange. Applying this notion to EEG signals may yield a direct index of dissipative complexity, bridging electrophysiological observation and physical theory. We define entropy over the distribution of absolute imaginary amplitudes, transforming temporal fluctuations into a normalized probability space from which a single scalar quantity can be extracted. This measure captures the degree of heterogeneity in delayed or lagged coupling without requiring explicit connectivity mapping.

Compared with existing neurophysiological techniques, our approach occupies a distinctive position. Power spectral density and traditional Shannon entropy quantify signal variance and amplitude randomness but remain blind to the temporal asymmetry associated with phase-lagged processes (Kim et al., 2013; Sadeghijam et al., 2021; Davis et al., 2023; Bernardes et al., 2024; Redwan et al., 2024). Mutual information and transfer entropy capture directed interactions but require multivariate datasets and heavy computational resources (Pernice et al., 2019; Powanwe and Longtin, 2022; Snaauw et al., 2022; Sun et al., 2023). Measures such as phase-lag index or imaginary coherence partially address the problem of volume conduction but treat the imaginary component as a statistical correction rather than a quantity with intrinsic meaning (Sander et al., 2010; Sanchez Bornot et al., 2018; Li et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2021; Kuang et al., 2022; Tian et al., 2024). By contrast, derives directly from the fundamental mathematical structure of analytic signals and uses the imaginary component as a primary object of measurement. Unlike approximate entropy or sample entropy, which rely on temporal embedding and threshold parameters, has a closed analytic definition and can be computed efficiently from any continuous signal. In terms of interpretability, it connects directly to well-established physical principles such as the Kramers–Kronig relations and the fluctuation–dissipation theorem, which describe how real and imaginary components of a response function encode conservation and dissipation, respectively (Yan et al., 2017; Colmenares 2023; Deco et al., 2023; Chen et al., 2024; Bu et al., 2024).

Several limitations must be acknowledged. Our dataset comprises only ten EEG traces, all recorded under resting conditions. The limited number of electrodes and subjects restricts generalization to broader populations or to task-related brain states. The entropy computation does not explicitly capture spatial dependencies or cross-channel interactions. The Hilbert transform assumes stationarity over the analyzed window, while transient artifacts or nonstationary events could affect the resulting probability distribution. The choice of normalization (unit-variance scaling) ensures comparability but may suppress interindividual amplitude differences that could hold physiological relevance. Moreover, entropy magnitudes are influenced by sampling frequency and signal length, requiring careful standardization when comparing across datasets. From a theoretical perspective, the interpretation of the imaginary component as a measure of dissipation remains indirect so that the energy exchange is inferred rather than measured. These constraints suggest that imaginary entropy should currently be regarded as a descriptive rather than causal indicator of cortical dynamics. Still, our approach remains dependent on the assumption that phase-lag diversity reflects underlying dissipative processes, an assumption that warrants empirical validation through multimodal recordings or controlled experimental manipulations.

Our framework suggests future work and potential applications. Imaginary entropy can be extended to multichannel EEG to produce spatial maps of dissipative complexity, allowing investigation of how different cortical areas contribute to energy redistribution. Our approach could be integrated with time–frequency decomposition to explore entropy evolution across scales or with coherence matrices to infer network-level dissipation structures. From a theoretical perspective, one can test specific hypotheses: for example, whether cognitive load or sensory stimulation modifies beyond the narrow resting range or whether pathological oscillations in epilepsy or coma produce shifts toward higher or lower entropy values. Moreover, by varying the spectral exponent α in synthetic noise models, it becomes possible to determine whether the brain operates closer to an adaptive critical regime or to stochastic equilibrium. Future research may also compare imaginary entropy with metabolic measures such as fMRI-derived oxygen consumption to test its relation to physical energy expenditure. Establishing standardized protocols for computing could further enable its incorporation into clinical or cognitive EEG pipelines, offering a physically grounded complement to existing measures of neural complexity.

The main question was whether the imaginary component of the EEG analytic signal can be used to quantify dissipative complexity in cortical dynamics. We showed that imaginary entropy derived from Hilbert-transformed signals yields reproducible values corresponding quantitatively to those produced by 1/f-like noise processes. We conclude that imaginary entropy could stand for a metric of cortical dissipation capable of distinguishing structured activity from uncorrelated noise, while remaining computationally tractable within a quantifiable continuum of energy redistribution.

Author Contributions

The Author performed: study concept and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content, statistical analysis, obtained funding, administrative, technical and material support, study supervision.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

This research does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by the Author.

Consent for Publication

The Author transfers all copyright ownership, in the event the work is published. The undersigned author warrants that the article is original, does not infringe on any copyright or other proprietary right of any third part, is not under consideration by another journal and has not been previously published.

Availability of Data and Materials

All data and materials generated or analyzed during this study are included in the manuscript. The Author had full access to all the data in the study and took responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Declaration of Generative AI and AI-Assisted Technologies in the Writing Process

During the preparation of this work, the author used ChatGPT 4o to assist with data analysis and manuscript drafting and to improve spelling, grammar and general editing. After using this tool, the author reviewed and edited the content as needed, taking full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Competing Interests

The Author does not have any known or potential conflict of interest including any financial, personal or other relationships with other people or organizations within three years of beginning the submitted work that could inappropriately influence or be perceived to influence their work.

References

- Asano, M., Bliokh, K. Y., Bliokh, Y. P., Kofman, A. G., Ikuta, R., Yamamoto, T., Kivshar, Y. S., Yang, L., Imoto, N., Özdemir, Ş. K., and Nori, F. “Anomalous Time Delays and Quantum Weak Measurements in Optical Micro-Resonators.” Nature Communications 7, no. 13488 (November 14, 2016). [CrossRef]

- Aur, D., and Vila-Rodriguez, F. “Dynamic Cross-Entropy.” Journal of Neuroscience Methods 275 (January 1, 2017): 10–18. [CrossRef]

- Bernardes, T. S., Santos, K. C. S., Nascimento, M. R., Filho, C. A. N. E. S., Bazan, R., Pereira, J. M., de Souza, L. A. P. S., and Luvizutto, G. J. “Effects of Anodal Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation over Motor Cortex on Resting-State Brain Activity in the Early Subacute Stroke Phase: A Power Spectral Density Analysis.” Clinical Neurology and Neurosurgery 237 (February 2024): 108134. [CrossRef]

- Bu, Z., Han, X., Wang, Y., Liu, S., Zhong, L., and Lu, X. “Multi-Wavelength Digital Holography Based on Kramers–Kronig Relations.” Optics Letters 49, no. 24 (December 15, 2024): 7154–7157. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X., Yao, S., Song, J., Ding, T., Li, G., Song, J., Nie, S., Ma, J., and Yuan, C. “Full-Angle Single-Shot Quantitative Phase Imaging Based on Kramers–Kronig Relations.” Optics Letters 49, no. 12 (June 15, 2024): 3512–3515. [CrossRef]

- Colmenares, P. J. “Generalized Dynamics and Fluctuation–Dissipation Theorem for a Parabolic Potential.” Physical Review E 108, no. 1–1 (July 2023): 014115. [CrossRef]

- Davis, J. J. J., Kozma, R., and Schübeler, F. “Analysis of Meditation vs. Sensory Engaged Brain States Using Shannon Entropy and Pearson’s First Skewness Coefficient Extracted from EEG Data.” Sensors (Basel) 23, no. 3 (January 23, 2023): 1293. [CrossRef]

- Deco, G., Lynn, C. W., Sanz Perl, Y., and Kringelbach, M. L. “Violations of the Fluctuation–Dissipation Theorem Reveal Distinct Nonequilibrium Dynamics of Brain States.” Physical Review E 108, no. 6–1 (December 2023): 064410. [CrossRef]

- Giovannelli, Isabella L., and Steven M. Anlage. “Physical Interpretation of Imaginary Time Delay.” Physical Review Letters 135, no. 4 (July 24, 2025): 043801. [CrossRef]

- Hu, H., Han, S., Yang, Y., Liu, D., Xue, H., Liu, G. G., Cheng, Z., Wang, Q. J., Zhang, S., Zhang, B., and Luo, Y. “Observation of Topological Edge States in Thermal Diffusion.” Advanced Materials 34, no. 31 (August 2022): e2202257. [CrossRef]

- Hull, A. C., and Morton, J. B. “Activity-State Entropy: A Novel Brain Entropy Measure Based on Spatial Patterns of Activity.” Journal of Neuroscience Methods 393 (June 1, 2023): 109868. [CrossRef]

- Jaušovec, N., and K. Jaušovec. “Spatiotemporal Brain Activity Related to Intelligence: A Low Resolution Brain Electromagnetic Tomography Study.” Brain Research Cognitive Brain Research 16, no. 2 (2003): 267–72. [CrossRef]

- Jaušovec, N., and K. Jaušovec. “Sex Differences in Brain Activity Related to General and Emotional Intelligence.” Brain and Cognition 59, no. 3 (2005): 277–86. [CrossRef]

- Kaushik, S. S., Robertson, S. H., Freeman, M. S., He, M., Kelly, K. T., Roos, J. E., Rackley, C. R., Foster, W. M., McAdams, H. P., and Driehuys, B. “Single-Breath Clinical Imaging of Hyperpolarized (129)Xe in the Airspaces, Barrier, and Red Blood Cells Using an Interleaved 3D Radial 1-Point Dixon Acquisition.” Journal of Applied Physiology (exact journal not provided in source; assumed clinical imaging study; verify citation).

- Kim, J. Y., Kim, S. H., Seo, J., Kim, S. H., Han, S. W., Nam, E. J., Kim, S. K., Lee, H. J., Lee, S. J., Kim, Y. T., and Chang, Y. “Increased Power Spectral Density in Resting-State Pain-Related Brain Networks in Fibromyalgia.” Pain 154, no. 9 (September 2013): 1792–1797. [CrossRef]

- Kuang, Y., Wu, Z., Xia, R., Li, X., Liu, J., Dai, Y., Wang, D., and Chen, S. “Phase Lag Index of Resting-State EEG for Identification of Mild Cognitive Impairment Patients with Type 2 Diabetes.” Brain Sciences 12, no. 10 (October 17, 2022): 1399. [CrossRef]

- Lau, Z. J., Pham, T., Chen, S. H. A., and Makowski, D. “Brain Entropy, Fractal Dimensions and Predictability: A Review of Complexity Measures for EEG in Healthy and Neuropsychiatric Populations.” European Journal of Neuroscience 56, no. 7 (October 2022): 5047–5069. [CrossRef]

- Le Van Quyen, M., Foucher, J., Lachaux, J., Rodriguez, E., Lutz, A., Martinerie, J., and Varela, F. J. “Comparison of Hilbert Transform and Wavelet Methods for the Analysis of Neuronal Synchrony.” Journal of Neuroscience Methods 111, no. 2 (October 30, 2001): 83–98. [CrossRef]

- Li, M., Gao, Y., Ding, Z., and Gore, J. C. “Power Spectra Reveal Distinct BOLD Resting-State Time Courses in White Matter.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 118, no. 44 (November 2, 2021): e2103104118. [CrossRef]

- Li, X., Wu, Y., Wei, M., Guo, Y., Yu, Z., Wang, H., Li, Z., and Fan, H. “A Novel Index of Functional Connectivity: Phase Lag Based on Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test.” Cognitive Neurodynamics 15, no. 4 (August 2021): 621–636. [CrossRef]

- Lutkenhoff, E. S., Nigri, A., Rossi Sebastiano, D., Sattin, D., Visani, E., Rosazza, C., D’Incerti, L., Bruzzone, M. G., Franceschetti, S., Leonardi, M., Ferraro, S., and Monti, M. M. “EEG Power Spectra and Subcortical Pathology in Chronic Disorders of Consciousness.” Psychological Medicine 52, no. 8 (June 2022): 1491–1500. [CrossRef]

- Xu, J., and Guo, W. “Imaginary Part of Timelike Entanglement Entropy.” Journal of High Energy Physics 2025, no. 94 (2025). [CrossRef]

- Xue, S., Guo, J., Li, P., and others. “Quantification of Resource Theory of Imaginarity.” Quantum Information Processing 20, no. 383 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Pernice, R., Zanetti, M., Nollo, G., De Cecco, M., Busacca, A., and Faes, L. “Mutual Information Analysis of Brain-Body Interactions during Different Levels of Mental Stress.” Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (July 2019): 6176–6179. [CrossRef]

- Phillips, N. S., Rao, V., Kmetz, L., Vela, R., Medick, S., Krull, K., and Kesler, S. R. “Changes in Brain Functional and Effective Connectivity After Treatment for Breast Cancer and Implications for Intervention Targets.” Brain Connectivity 12, no. 4 (May 2022): 385–397. [CrossRef]

- Powanwe, A. S., and Longtin, A. “Mutual Information Resonances in Delay-Coupled Limit Cycle and Quasi-Cycle Brain Rhythms.” Biological Cybernetics 116, no. 2 (April 2022): 129–146. [CrossRef]

- Redwan, S. M., Uddin, M. P., Ulhaq, A., Sharif, M. I., and Krishnamoorthy, G. “Power Spectral Density-Based Resting-State EEG Classification of First-Episode Psychosis.” Scientific Reports 14, no. 1 (July 2, 2024): 15154. [CrossRef]

- Sadeghijam, M., Talebian, S., Mohsen, S., Akbari, M., and Pourbakht, A. “Shannon Entropy Measures for EEG Signals in Tinnitus.” Neuroscience Letters 762 (September 25, 2021): 136153. [CrossRef]

- Sanchez Bornot, J. M., Wong-Lin, K., Ahmad, A. L., and Prasad, G. “Robust EEG/MEG Based Functional Connectivity with the Envelope of the Imaginary Coherence: Sensor Space Analysis.” Brain Topography 31, no. 6 (November 2018): 895–916. [CrossRef]

- Sander, T. H., Bock, A., Leistner, S., Kuhn, A., and Trahms, L. “Coherence and Imaginary Part of Coherency Identifies Cortico-Muscular and Cortico-Thalamic Coupling.” Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (2010): 1714–1717. [CrossRef]

- Shiju, S., and Sriram, K. “Hilbert Transform-Based Time-Series Analysis of the Circadian Gene Regulatory Network.” IET Systems Biology 13, no. 4 (August 2019): 159–168. [CrossRef]

- Silva, P. H. R. D., Secchinato, K. F., Rondinoni, C., and Leoni, R. F. “Brain Structural-Functional Connectivity Relationship Underlying the Information Processing Speed.” Brain Connectivity 10, no. 3 (April 2020): 143–154. [CrossRef]

- Snaauw, G., Sasdelli, M., Maicas, G., Lau, S., Verjans, J., Jenkinson, M., and Carneiro, G. “Mutual Information Neural Estimation for Unsupervised Multi-Modal Registration of Brain Images.” Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (July 2022): 3510–3513. [CrossRef]

- Stein, A., Thorstensen, J. R., Ho, J. M., Ashley, D. P., Iyer, K. K., and Barlow, K. M. “Attention Please! Unravelling the Link Between Brain Network Connectivity and Cognitive Attention Following Acquired Brain Injury: A Systematic Review of Structural and Functional Measures.” Brain Connectivity 14, no. 1 (February 2024): 4–38. [CrossRef]

- Sun, H., Lin, F., Wu, X., Zhang, T., and Li, J. “Normalized Mutual Information of fNIRS Signals as a Measure for Assessing Typical and Atypical Brain Activity.” Journal of Biophotonics 16, no. 6 (June 2023): e202200369. [CrossRef]

- Tozzi, A., E. Bormashenko, and N. Jausovec. “Topology of EEG Wave Fronts.” Cognitive Neurodynamics 15 (2021a): 887–96. [CrossRef]

- Tozzi, A., J. F. Peters, N. Jausovec, A. P. H. Don, S. Ramanna, I. Legchenkova, and E. Bormashenko. “Nervous Activity of the Brain in Five Dimensions.” Biophysica 1, no. 1 (2021b): 38–47. [CrossRef]

- Tian, W., Zhao, D., Ding, J., Zhan, S., Zhang, Y., Etkin, A., Wu, W., and Yuan, T. F. “An Electroencephalographic Signature Predicts Craving for Methamphetamine.” Cell Reports Medicine 5, no. 1 (January 16, 2024): 101347. [CrossRef]

- Yan, H., Johnston, J. F., Cahn, S. B., King, M. C., and Mochrie, S. G. J. “Multiplexed Fluctuation–Dissipation–Theorem Calibration of Optical Tweezers Inside Living Cells.” Review of Scientific Instruments 88, no. 11 (November 2017): 113112. [CrossRef]

- Yang, S., Xu, G., Zhou, X., Li, J., Kong, X., Zhou, C., Fan, H., Chen, J., and Qiu, C. W. “Hierarchical Bound States in Heat Transport.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 121, no. 38 (September 17, 2024): e2412031121. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z., Li, Y., Childress, A. R., and Detre, J. A. “Brain Entropy Mapping Using fMRI.” PLoS One 9, no. 3 (March 21, 2014): e89948. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z., Zhao, Y., He, Y., and Zhang, J. “Phase Lag Index-Based Graph Attention Networks for Detecting Driving Fatigue.” Review of Scientific Instruments 92, no. 9 (September 1, 2021): 094105. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y., Zhou, Y., and Song, M. “Classification of Patients with AD from Healthy Controls Using Entropy-Based Measures of Causality Brain Networks.” Journal of Neuroscience Methods 361 (September 1, 2021): 109265. [CrossRef]

- Wu, K. D., Kondra, T. V., Scandolo, C. M., and others. “Resource Theory of Imaginarity in Distributed Scenarios.” Communications Physics 7, no. 171 (2024). [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).