Submitted:

27 October 2025

Posted:

28 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

The genus Bradyrhizobium comprises phylogenetically diverse bacteria that establish symbioses with numerous legumes, including economically important crops such as cowpea (Vigna unguiculata) and soybean (Glycine max). This study characterized 34 Bradyrhizobium strains isolated from nodules of cowpea and soybean cultivated in adjacent tropical soils in Brazil to elucidate the relationships between the symbionts and their hosts. Phylogenetic analyses of 16S rRNA, gyrB, recA, and nodC genes, combined with genome sequencing and comparative analyses (ANI and dDDH), revealed high genetic diversity and distinct taxonomic affiliations. Most strains clustered within the B. elkanii superclade, although several occupied divergent lineages, some potentially representing new taxons. Genome-based analyses confirmed these patterns, showing ANI values above 95–96% within groups and below 94% across distant strains. One group of cowpea-derived strains exhibited high symbiotic efficiency and low similarity to all known type strains, suggesting the presence of a novel species with potential for the crop. Conversely, some soybean-derived strains were genetically identical to commercial inoculants, indicating persistence or re-isolation from inoculated soils. Remarkably, strain BR 13971, isolated from soybean, nodulated both hosts efficiently, suggesting a distinct symbiovar with broad host compatibility. Cross-inoculation assays demonstrated that soybean-derived strains nodulated cowpea, but the reverse was not observed. These findings expand the understanding of Bradyrhizobium diversity in tropical soils and highlight the potential of native strains for inoculant development.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

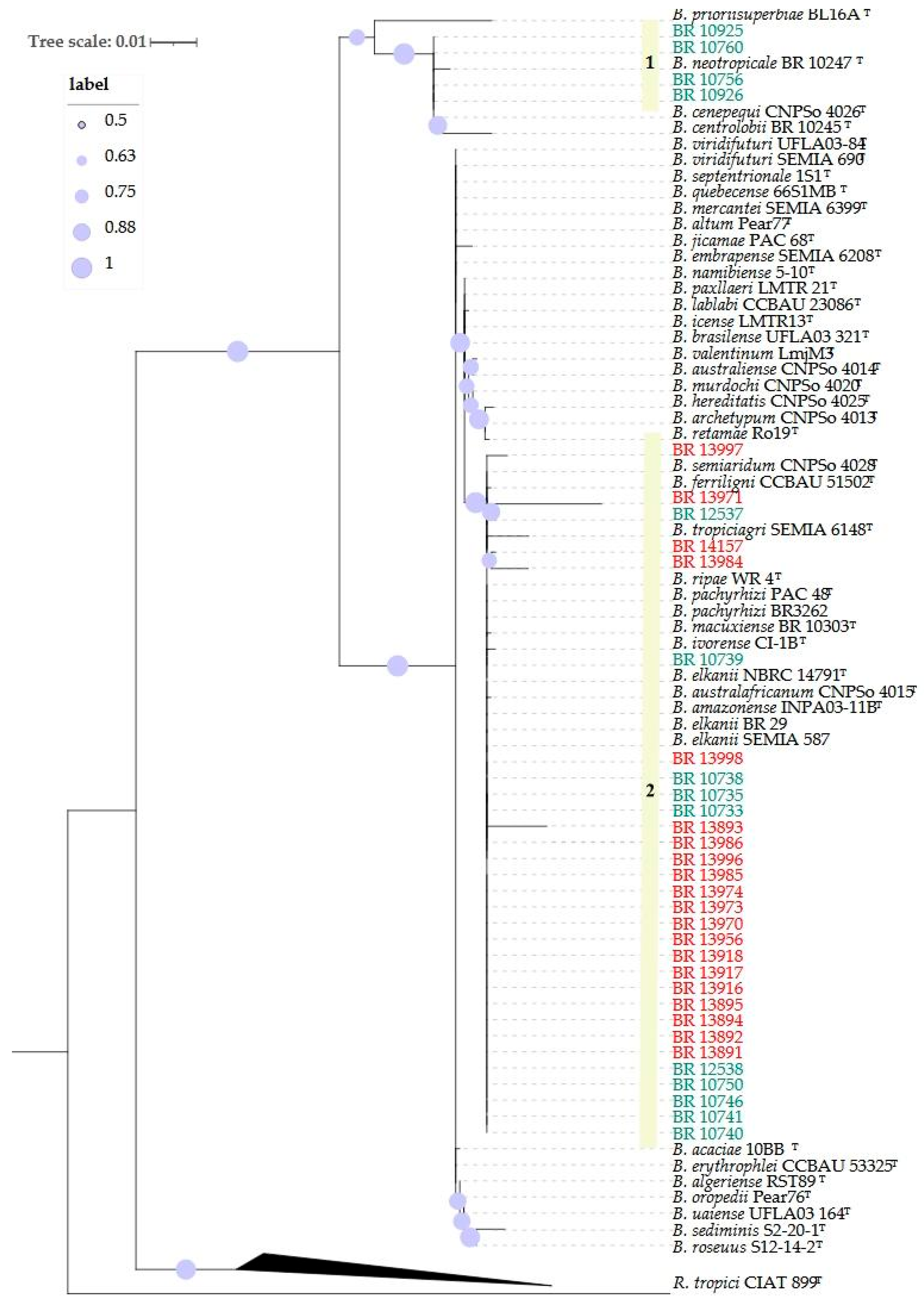

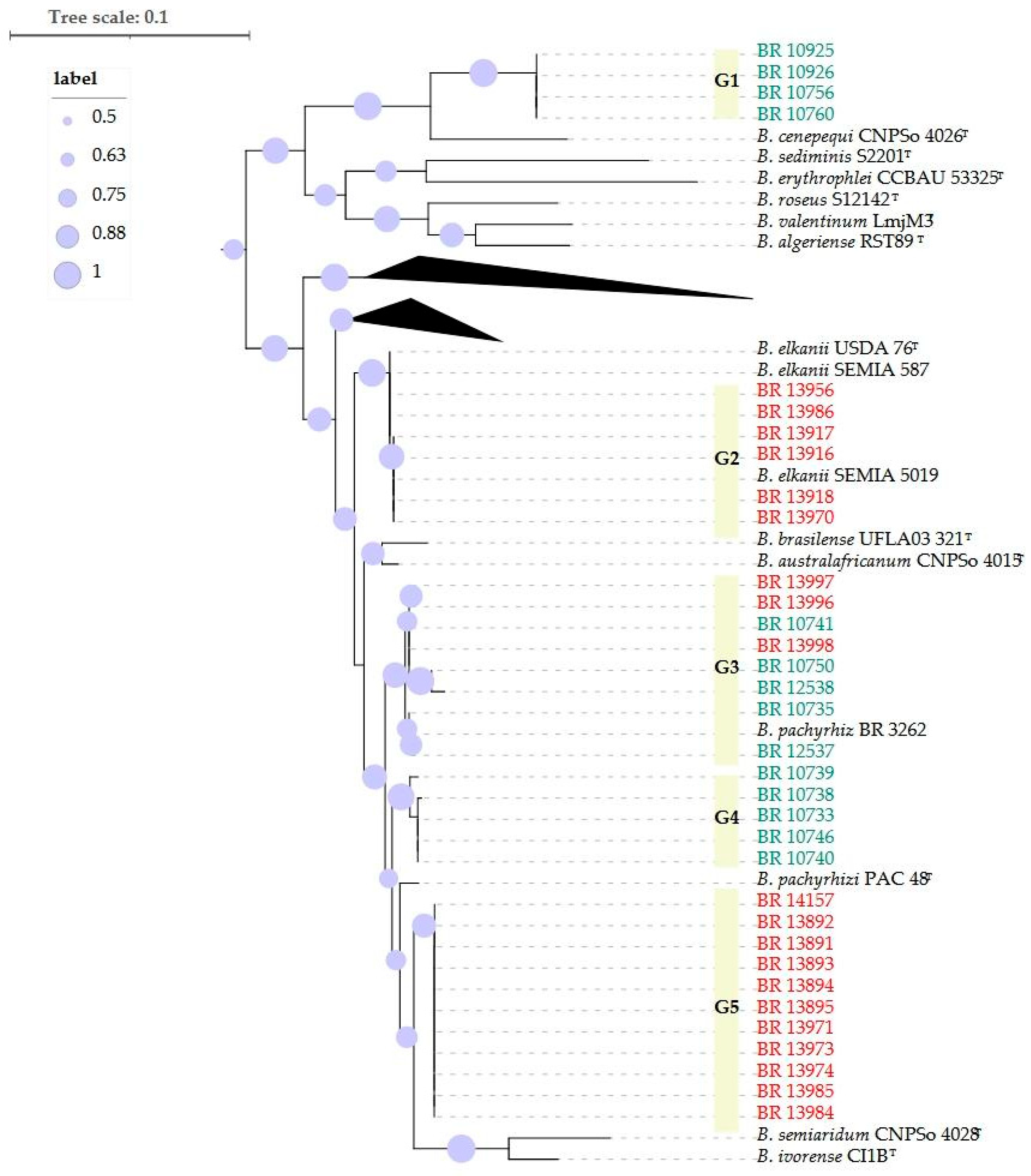

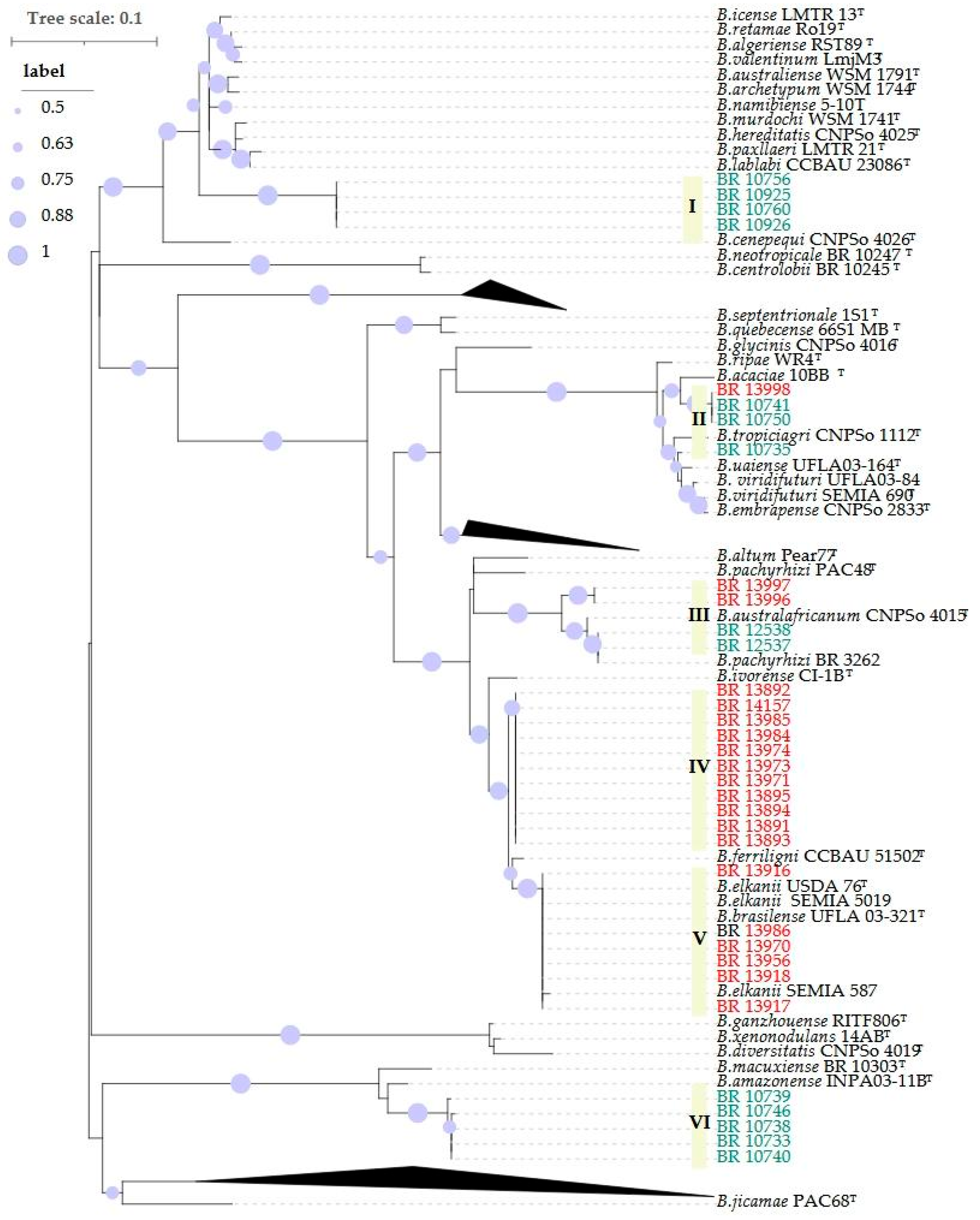

2.1. Phylogenetic Analyses

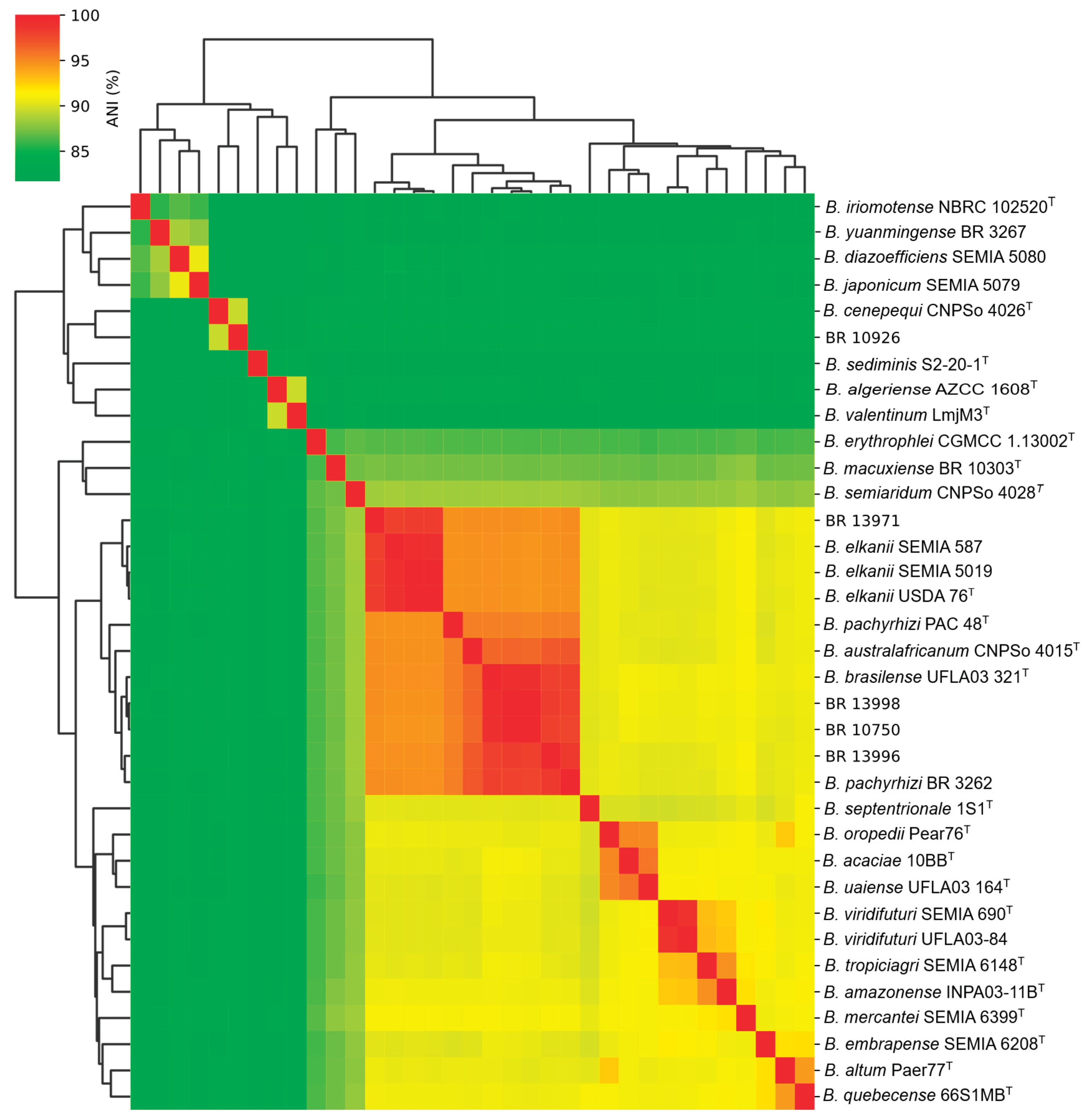

2.2. Genome Sequencing, Average Nucleotide Identity (ANI) and Digital DNA–DNA Hybridization (dDDH)

2.3. Inoculation Tests

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Bacterial Strains

4.2. DNA Extraction, PCR, Sequencing Phylogenetic Analysis

4.3. Genome Sequencing, Assembly, Annotation, ANI and dDDH

4.3. Plant Inoculation Tests

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ANI | Average Nucleotide Identity |

| dDDH | digital DNA–DNA Hybridization |

| recA | recombinase gene A |

| gyrB | DNA gyrase subunit B |

| nodC | recombinase A |

References

- Sprent, J.I.; Ardley, J.; James, E.K. Biogeography of Nodulated Legumes and Their Nitrogen-Fixing Symbionts. New Phytol 2017, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimlou, S.; Bahram, M.; Tedersoo, L. Phylogenomics Reveals the Evolution of Root Nodulating Alpha- and Beta-Proteobacteria (Rhizobia). Microbiol Res 2021, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, V.; Bhattacharyya, S.; Kumar, R.; Kumar, A.; Ibañez, F.; Wang, J.; Guo, B.; Sudini, H.K.; Gopalakrishnan, S.; Dasgupta, M.; et al. Molecular Basis of Root Nodule Symbiosis between Bradyrhizobium and ‘Crack-Entry’ Legume Groundnut (Arachis hypogaea L.). Plants 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terra, L.A.; Klepa, M.S.; Nogueira, M.A.; Hungria, M. Pangenome Analysis Indicates Evolutionary Origins and Genetic Diversity: Emphasis on the Role of Nodulation in Symbiotic Bradyrhizobium. Front Plant Sci 2025, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hungria, M.; Campo, R.J.; De Carvalho Mendes, I.; Graham, P.H. Contribution of Biological Nitrogen Fixation to the N Nutrition of Grain Crops in the Tropics: The Success of Soybean (Glycine max L. Merr.) in South America. Nitrogen Nutrition and Sustainable Plant Productivity 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews, M.; Andrews, M.E. Specificity in Legume-Rhizobia Symbioses. Int J Mol Sci 2017, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaiswal, S.K.; Dakora, F.D. Widespread Distribution of Highly Adapted Bradyrhizobium Species Nodulating Diverse Legumes in Africa. Front Microbiol 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, M.A. Case of Localized Recombination in 23S rRNA Genes from Divergent Bradyrhizobium Lineages Associated with Neotropical Legumes. Appl Environ Microbiol 2001, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poole, P.; Ramachandran, V.; Terpolilli, J. Rhizobia: From Saprophytes to Endosymbionts. Nat Rev Microbiol 2018, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chibeba, A.M.; Kyei-Boahen, S.; Guimarães, M. de F.; Nogueira, M.A.; Hungria, M. Feasibility of Transference of Inoculation-Related Technologies: A Case Study of Evaluation of Soybean Rhizobial Strains under the Agro-Climatic Conditions of Brazil and Mozambique. Agric Ecosyst Environ 2018, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hungria, M.; Mendes, I.C. Nitrogen Fixation with Soybean: The Perfect Symbiosis? In Biological Nitrogen Fixation; 2nd ed.; Vol. 2–2; 2015.

- Telles, T.S.; Nogueira, M.A.; Hungria, M. Economic Value of Biological Nitrogen Fixation in Soybean Crops in Brazil. Environ Technol Innov 2023, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, M.S.; Nogueira, M.A.; Hungria, M. Microbial Inoculants: Reviewing the Past, Discussing the Present and Previewing an Outstanding Future for the Use of Beneficial Bacteria in Agriculture. AMB Express 2019, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prando, A.M.; Barbosa, J.Z.; Oliveira, A.B. de; Nogueira, M.A.; Possamai, E.J.; Hungria, M. Benefits of Soybean Co-Inoculation with Bradyrhizobium spp. and Azospirillum brasilense: Large-Scale Validation with Farmers in Brazil. Eur J Agron 2024, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barcellos, F.G.; Menna, P.; Batista, J.S.D.S.; Hungria, M. Evidence of Horizontal Transfer of Symbiotic Genes from a Bradyrhizobium japonicum Inoculant Strain to Indigenous Diazotrophs Sinorhizobium (Ensifer) fredii and Bradyrhizobium elkanii in a Brazilian Savannah Soil. Appl Environ Microbiol 2007, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batista, J.S.S.; Hungria, M.; Barcellos, F.G.; Ferreira, M.C.; Mendes, I.C. Variability in Bradyrhizobium japonicum and B. elkanii Seven Years after Introduction of Both the Exotic Microsymbiont and the Soybean Host in a Cerrado Soil. elkanii Seven Years after Introduction of Both the Exotic Microsymbiont and the Soybean Host in a Cerrado Soil. Microb Ecol 2007, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, I.C.; Hungria, M.; Vargas, M.A.T. Establishment of Bradyrhizobium japonicum and B. elkanii Strains in a Brazilian Cerrado Oxisol. elkanii Strains in a Brazilian Cerrado Oxisol. Biol Fertil Soils 2004, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez, M.D.A.; España, M.; Aguirre, C.; Kojima, K.; Ohkama-Ohtsu, N.; Sekimoto, H.; Yokoyama, T. Burkholderia and Paraburkholderia Are Predominant Soybean Rhizobial Genera in Venezuelan Soils in Different Climatic and Topographical Regions. Microbes Environ 2019, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, A.; Panzera, M.; Roldán, D.M.; Viera, F.; Fernández, S.; Zabaleta, M.; Amarelle, V.; Fabiano, E. Diversity of Bradyrhizobium Strains That Nodulate Lupinus Species Native to Uruguay. Environ Sustain 2023, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pule-Meulenberg, F.; Belane, A.K.; Krasova-Wade, T.; Dakora, F.D. Symbiotic Functioning and Bradyrhizobium Biodiversity of Cowpea (Vigna unguiculata L. Walp.) in Africa. BMC Microbiol 2010, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, I.J.; Botha, W.F.; Majaule, U.C.; Phalane, F.L. Symbiotic and Genomic Diversity of “Cowpea” Bradyrhizobium from Soils in Botswana and South Africa. Biol Fertil Soils 2007, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thies, J.E.; Bohlool, B.B.; Singleton, P.W. Subgroups of the Cowpea Miscellany: Symbiotic Specificity within Bradyrhizobium spp. for Vigna unguiculata, Phaseolus lunatus, Arachis hypogaea, and Macroptilium atropurpureum. Appl Environ Microbiol 1991, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zilli, J.É.; Valisheski, R.R.; Freire Filho, F.R.; Neves, M.C.P.; Rumjanek, N.G. Assessment of Cowpea Rhizobium Diversity in Cerrado Areas of Northeastern Brazil. Braz J Microbiol 2004, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Castro, J.L.; Souza, M.G.; Rufini, M.; Guimarães, A.A.; Rodrigues, T.L.; Moreira, F.M. de S. Diversity and Efficiency of Rhizobia Communities from Iron Mining Areas Using Cowpea as a Trap Plant. Rev Bras Cienc Solo 2017, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VanInsberghe, D.; Maas, K.R.; Cardenas, E.; Strachan, C.R.; Hallam, S.J.; Mohn, W.W. Non-Symbiotic Bradyrhizobium Ecotypes Dominate North American Forest Soils. ISME J 2015, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avontuur, J.R.; Palmer, M.; Beukes, C.W.; Chan, W.Y.; Coetzee, M.P.A.; Blom, J.; Stępkowski, T.; Kyrpides, N.C.; Woyke, T.; Shapiro, N.; et al. Genome-Informed Bradyrhizobium Taxonomy: Where to from Here? Syst Appl Microbiol 2019, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ormeño-Orrillo, E.; Martínez-Romero, E. A Genomotaxonomy View of the Bradyrhizobium Genus. Front Microbiol 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferraz Helene, L.C.; O’Hara, G.; Hungria, M. Characterization of Bradyrhizobium Strains Indigenous to Western Australia and South Africa Indicates Remarkable Genetic Diversity and Reveals Putative New Species. Syst Appl Microbiol 2020, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, F.P.; Clark, I.M.; King, R.; Shaw, L.J.; Woodward, M.J.; Hirsch, P.R. Novel European Free-Living, Non-Diazotrophic Bradyrhizobium Isolates from Contrasting Soils That Lack Nodulation and Nitrogen Fixation Genes—A Genome Comparison. Sci Rep 2016, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sessitsch, A.; Howieson, J.G.; Perret, X.; Antoun, H.; Martínez-Romero, E. Advances in Rhizobium Research. Crit Rev Plant Sci 2002, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukami, J.; De La Osa, C.; Ollero, F.J.; Megías, M.; Hungria, M. Co-Inoculation of Maize with Azospirillum brasilense and Rhizobium tropici as a Strategy to Mitigate Salinity Stress. Funct Plant Biol 2018, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brasil. Instrução Normativa No. 13, de 24 de Março de 2011. Available online: https://www.gov.br/agricultura/pt-br/assuntos/insumos-agropecuarios/insumos-agricolas/fertilizantes/legislacao/in-sda-13-de-24-03-2011-inoculantes.pdf/view (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Leite, J.; Passos, S.R.; Simões-Araújo, J.L.; Rumjanek, N.G.; Xavier, G.R.; Zilli, J.É. Genomic Identification and Characterization of the Elite Strains Bradyrhizobium yuanmingense BR 3267 and Bradyrhizobium pachyrhizi BR 3262 Recommended for Cowpea Inoculation in Brazil. Braz J Microbiol 2018, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza Moreira, F.M.; Cabral Michel, D.; Marques Cardoso, R. The Elite Strain INPA03-11B Approved as a Cowpea Inoculant in Brazil Represents a New Bradyrhizobium Species and It Has High Adaptability to Stressful Soil Conditions. Braz J Microbiol 2024, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins da Costa, E.; Soares de Carvalho, T.; Azarias Guimarães, A.; Ribas Leão, A.C.; Magalhães Cruz, L.; de Baura, V.A.; Lebbe, L.; Willems, A.; de Souza Moreira, F.M. Classification of the Inoculant Strain of Cowpea UFLA03-84 and of Other Strains from Soils of the Amazon Region as Bradyrhizobium viridifuturi (Symbiovar tropici). Braz J Microbiol 2019, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanko, D.; Andargie, M. Genetic Diversity of Root-Nodulating Rhizobia Associated with Cowpea Genotypes in Different Agro-Ecological Regions: A Review. Biologia (Bratisl) 2025, 80, 2215–2239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, M.C.; Hungria, M. Recovery of Soybean Inoculant Strains from Uncropped Soils in Brazil. Field Crops Res 2002, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willems, A.; Coopman, R.; Gillis, M. Phylogenetic and DNA-DNA Hybridization Analyses of Bradyrhizobium Species. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2001, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martens, M.; Delaere, M.; Coopman, R.; De Vos, P.; Gillis, M.; Willems, A. Multilocus Sequence Analysis of Ensifer and Related Taxa. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2007, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zilli, J.E.; Neves, M.C.P.; Rumjanek, N.G. Signalling Specificity of Rhizobia Isolated from Nodules of Phaseoleae and Indigofereae Tribes. An Acad Bras Cienc 1998, 70. [Google Scholar]

- Minamisawa, K.; Itakura, M.; Suzuki, M.; Ichige, K. ; Tsuyoshiisawa; Yuhashi, K.I.; Mitsui, H. Horizontal Transfer of Nodulation Genes in Soils and Microcosms from Bradyrhizobium japonicum to B. elkanii. Microbes Environ 2002, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moulin, L.; Béna, G.; Boivin-Masson, C.; Stȩpkowski, T. Phylogenetic Analyses of Symbiotic Nodulation Genes Support Vertical and Lateral Gene Co-Transfer within the Bradyrhizobium Genus. Mol Phylogenet Evol 2004, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Lajudie, P.M.; Andrews, M.; Ardley, J.; Eardly, B.; Jumas-Bilak, E.; Kuzmanović, N.; Lassalle, F.; Lindström, K.; Mhamdi, R.; Martínez-Romero, E.; et al. Minimal Standards for the Description of New Genera and Species of Rhizobia and Agrobacteria. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2019, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, J.; Oren, A.; Ventosa, A.; Christensen, H.; Arahal, D.R.; da Costa, M.S.; Rooney, A.P.; Yi, H.; Xu, X.W.; De Meyer, S.; et al. Proposed Minimal Standards for the Use of Genome Data for the Taxonomy of Prokaryotes. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2018, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banasiewicz, J.; Granada, C.E.; Lisboa, B.B.; Grzesiuk, M.; Matuśkiewicz, W.; Bałka, M.; Schlindwein, G.; Vargas, L.K.; Passaglia, L.M.P.; Stępkowski, T. Diversity and Phylogenetic Affinities of Bradyrhizobium Isolates from Pampa and Atlantic Forest Biomes. Syst Appl Microbiol 2021, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wadson Meneses Santos. Emissões de N₂O na Cultura da Soja Inoculada com Diferentes Estirpes de Bradyrhizobium spp. Doctoral Thesis, Universidade Federal Rural do Rio de Janeiro, Seropédica, Brazil, 2021.

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Li, M.; Knyaz, C.; Tamura, K. MEGA X: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis across Computing Platforms. Mol Biol Evol 2018, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, M. A Simple Method for Estimating Evolutionary Rates of Base Substitutions through Comparative Studies of Nucleotide Sequences. J Mol Evol 1980, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Letunic, I.; Bork, P. Interactive Tree of Life (iTOL) v4: Recent Updates and New Developments. Nucleic Acids Res 2019, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Coster, W.; Rademakers, R. NanoPack2: Population-Scale Evaluation of Long-Read Sequencing Data. Bioinformatics 2023, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolger, A.M.; Lohse, M.; Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: A Flexible Trimmer for Illumina Sequence Data. Bioinformatics 2014, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolmogorov, M.; Bickhart, D.M.; Behsaz, B.; Gurevich, A.; Rayko, M.; Shin, S.B.; Kuhn, K.; Yuan, J.; Polevikov, E.; Smith, T.P.L.; et al. MetaFlye: Scalable Long-Read Metagenome Assembly Using Repeat Graphs. Nat Methods 2020, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurevich, A.; Saveliev, V.; Vyahhi, N.; Tesler, G. QUAST: Quality Assessment Tool for Genome Assemblies. Bioinformatics 2013, 29, 1072–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, S.; others. FastQC: A Quality Control Tool for High Throughput Sequence Data. Available online: https://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/ (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Brettin, T.; Davis, J.J.; Disz, T.; Edwards, R.A.; Gerdes, S.; Olsen, G.J.; Olson, R.; Overbeek, R.; Parrello, B.; Pusch, G.D.; et al. RASTtk: A Modular and Extensible Implementation of the RAST Algorithm for Building Custom Annotation Pipelines and Annotating Batches of Genomes. Sci Rep 2015, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimoyama, Y. ANIclustermap: A Tool for Drawing ANI Clustermap between All-vs-All Microbial Genomes. Bioinformatics, (submitted).

- Meier-Kolthoff, J.P.; Göker, M. TYGS Is an Automated High-Throughput Platform for State-of-the-Art Genome-Based Taxonomy. Nat Commun 2019, 10, 2182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwartz, W.J.M. Vincent, A Manual for the Practical Study of the Root-Nodule Bacteria (IBP Handbuch No. 15 des International Biology Program, London). XI u. 164 S., 10 Abb., 17 Tab., 7 Taf. Oxford–Edinburgh 1970: Blackwell Scientific Publ., 45 s. Z Allg Mikrobiol 1972, 12, 440–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, D.O.; Date, R.A. Legume Bacteriology in Tropical Pasture Research: Principles and Methods. In Tropical Pasture Research: Principles and Methods; Shaw, N.H., Bryan, W.W., Eds.; Commonwealth Agricultural Bureaux: Farnham Royal, UK, 1976; Vol. 51, pp. 134–174. [Google Scholar]

| Host | Local | Coord. | Strains | Groups | Cowpea | Soybean | ||||||

|

16S rRNA |

recA- gyrB |

nodC | NN | MN | DM | NN | MN | DM | ||||

| Cowpea | Pasture | 22°45'10"S 43°40'25"W |

BR 10926 | 1 | G1 | I | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 |

| BR 10925 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | ||||||

| BR 10756 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | ||||||

| BR 10760 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | ||||||

| BR 10735 | 2 | G3 | II | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | |||

| BR 10741 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | ||||||

| BR 10750 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | ||||||

| BR 12538 | III | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | |||||

| Area cultiveted | 22°45'11"S 43°40'26"W |

BR 12537 | G3 | III | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | ||

| Forest | 22°45'04"S 43°40'18"W |

BR 10733 | G4 | VI | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | ||

| BR 10738 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | ||||||

| BR 10739 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | ||||||

| BR 10740 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | ||||||

| BR 10746 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | ||||||

| Soybean | Área with soybean Inoculated | 22°44'51"S 43°40'15"W |

BR 13916 | G2 | VI | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | |

| BR 13917 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.3 | ||||||

| BR 13918 | V | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 1.0 | |||||

| BR 13956 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 1.0 | 0.7 | 1.0 | ||||||

| BR 13970 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 0.8 | ||||||

| BR 13998 | G3 | II | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.4 | ||||

| BR 13996 | III | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | |||||

| BR 13997 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.4 | ||||||

| BR 13971 | G5 | IV | 0.9 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.3 | ||||

| BR 13973 | 1.0 | 0.9 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.3 | ||||||

| BR 13986 | G2 | V | 0.9 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.4 | ||||

| BR 13974 | G5 | IV | 0.9 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 0.4 | ||||

| Área with soybean uninoculated | 22°44'53"S 43°40'13"W |

BR 13891 | 0.5 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.3 | ||||

| BR 13892 | 0.8 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.2 | ||||||

| BR 13893 | 0.5 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.4 | ||||||

| BR 13894 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.4 | ||||||

| BR 13895 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.8 | 0.3 | ||||||

| BR 13984 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.7 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.2 | ||||||

| BR 13985 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.5 | ||||||

| BR 14157 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.6 | ||||||

| Control | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | ||||||

| Control | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | ||||||

| Host | NN | MN | DM | 1 |  |

0 | ||||||

| Soybean | 54.5 | 215.0 | 2.3 | Max | Normalized value (0-1) | |||||||

| Cowpea | 60 | 201.5 | 2.5 | |||||||||

| Soybean | 0 | 0 | 0.3 | Min. | ||||||||

| Cowpea | 0 | 0 | 0.3 | |||||||||

| Strains | BR 13971 | USDA 76ᵀ | BR 10750 | BR 13996 | BR 13998 | CNPSo 4015ᵀ | UFLA 03-321ᵀ |

BR 10926 | CNPSo 4026ᵀ | PAC 48ᵀ |

| ANI (%) | ||||||||||

| BR 13971 | - | 98.1 | 94.7 | 94.7 | 94.8 | 94.8 | 94.8 | 94.7 | 83.3 | 83.2 |

|

B. elkanii USDA 76ᵀ |

98.1 | - | 94.4 | 94.6 | 94.6 | 94.7 | 94.7 | 94.6 | 83.3 | 83.2 |

| BR 10750 | 94.7 | 94.4 | - | 98.0 | 99.8 | 96.2 | 99.0 | 95.2 | 83.4 | 83.2 |

| BR 13996 | 94.7 | 94.6 | 98.0 | - | 98.1 | 96.9 | 98.1 | 95.4 | 83.4 | 83.2 |

| BR 13998 | 94.8 | 94.6 | 99.8 | 98.1 | - | 96.4 | 99.2 | 95.4 | 83.4 | 83.2 |

| B. australafricanum CNPSo 4015T | 94.8 | 94.7 | 96.2 | 96.9 | 96.4 | - | 96.3 | 95.4 | 83.3 | 83.3 |

|

B. brasilense UFLA03-321ᵀ |

94.8 | 94.7 | 99.0 | 98.1 | 99.2 | 96.3 | - | 95.4 | 83.5 | 83.3 |

|

B. pachyrhizi PAC 48ᵀ |

94.7 | 94.6 | 95.2 | 95.4 | 95.4 | 95.4 | 95.4 | - | 83.3 | 83.1 |

| BR 10926 | 83.3 | 83.3 | 83.4 | 83.4 | 83.4 | 83.3 | 83.5 | 83.3 | - | 89.5 |

|

B. cenepequi CNPSo 4026ᵀ |

83.2 | 83.2 | 83.2 | 83.2 | 83.2 | 83.3 | 83.3 | 83.1 | 89.5 | - |

| dDDH (%) | ||||||||||

| BR 13971 | - | 83.6 | 59.3 | 58.6 | 59.7 | 58.7 | 61.9 | 25.5 | 25.4 | 57.0 |

|

B. elkanii USDA 76ᵀ |

83.6 | - | 58.6 | 58.6 | 59.0 | 58.8 | 61.8 | 25.6 | 25.5 | 57.4 |

| BR 10750 | 59.3 | 58.6 | - | 84.6 | 99.0 | 70.7 | 68.9 | 25.6 | 25.3 | 62.6 |

| BR 13996 | 58.6 | 58.6 | 84.6 | - | 85.5 | 73.8 | 94.2 | 25.5 | 25.4 | 63.9 |

| BR 13998 | 59.7 | 59.0 | 99.0 | 85.5 | - | 71.8 | 85.7 | 25.6 | 25.3 | 63.0 |

| B. australafricanum CNPSo 4015T | 58.7 | 58.8 | 70.7 | 73.8 | 71.8 | - | 70.0 | 25.5 | 25.4 | 62.2 |

|

B. brasilense UFLA03-321ᵀ |

61.9 | 61.8 | 68.9 | 94.2 | 85.7 | 70.0 | - | 25.5 | 25.4 | 62.8 |

|

B. pachyrhizi PAC 48ᵀ |

57.0 | 57.4 | 62.6 | 63.9 | 63.0 | 62.2 | 62.8 | 25.4 | 25.3 | - |

| BR 10926 | 25.5 | 25.6 | 25.6 | 25.5 | 25.6 | 25.5 | 25.5 | - | 39.5 | 25.4 |

|

B. cenepequi CNPSo 4026ᵀ |

25.4 | 25.5 | 25.3 | 25.4 | 25.3 | 25.4 | 25.4 | 39.5 | - | 25.3 |

| Strain | Number of nodules | Nodules dry mass (mg plant-1) | Plant dry matter (g plant-1 | |||

| Cowpea | ||||||

| BR 10926 | 130.7 | A | 220.3 | A | 4,3 | A |

| BR 10750 | 133.2 | A | 245.7 | A | 4,2 | A |

| Nitrogen | 0.0 | E | 0.0 | D | 3,9 | A |

| BR 13971 | 84.0 | B | 92.0 | C | 3,6 | AB |

| BR 3262 | 106.2 | A | 83.7 | C | 3,6 | B |

| BR 13956 | 54.0 | D | 41.8 | CD | 2,4 | C |

| Controle | 0.0 | E | 0.0 | D | 1,1 | D |

| CV (%) | 19,6 | 31,82 | 9,37 | |||

| Soybean | ||||||

| BR 13956 | 117,7 | A | 294,7 | A | 4,3 | A |

| BR 13971 | 96,0 | A | 125,0 | B | 2,8 | B |

| SEMIA 5079 | 91,0 | A | 336,3 | A | 4.0 | AB |

| Control | 0,0 | B | 0,0 | C | 1,3 | C |

| Nitrogen | 0,0 | B | 0,0 | C | 5,4 | A |

| CV (%) | 27,2 | 26,76 | 17,2 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).