Submitted:

27 October 2025

Posted:

28 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. HMIs Sorption Experiments

2.3. Characterization Methods

2.4. Wheat Germination Experiments

3. Results

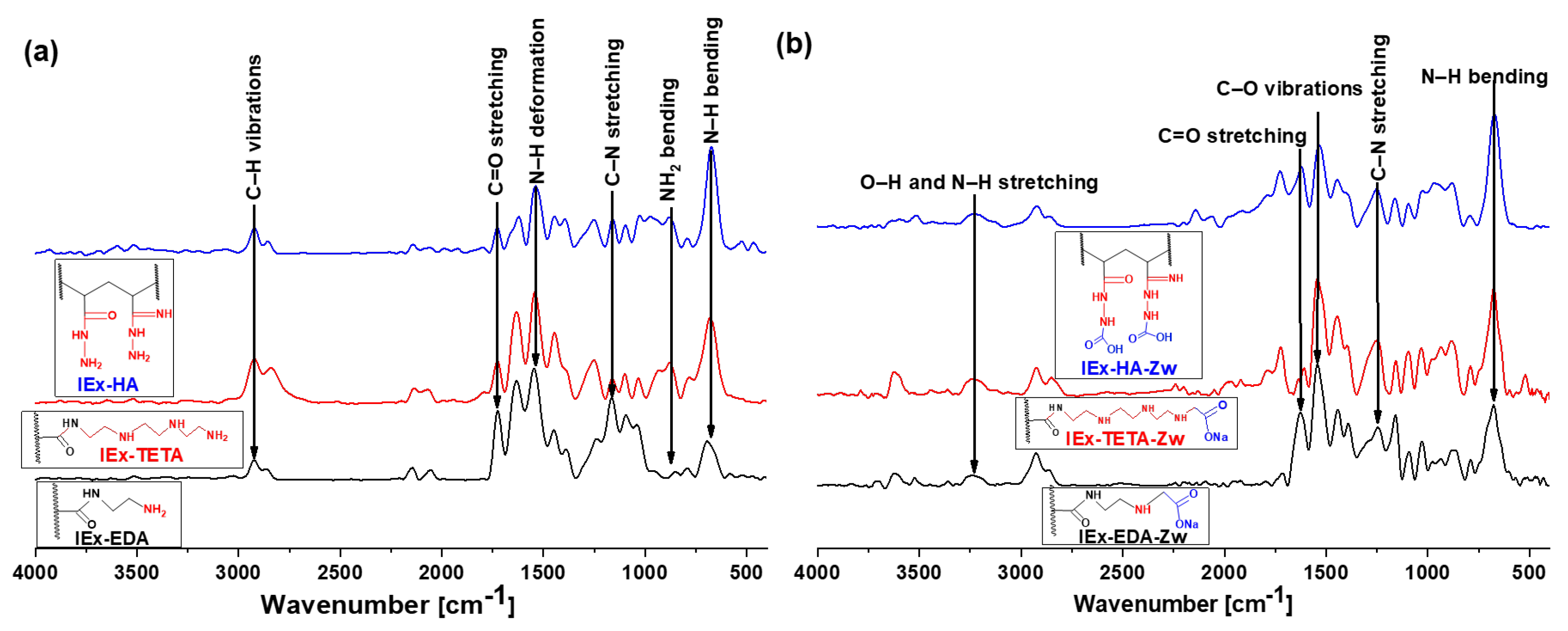

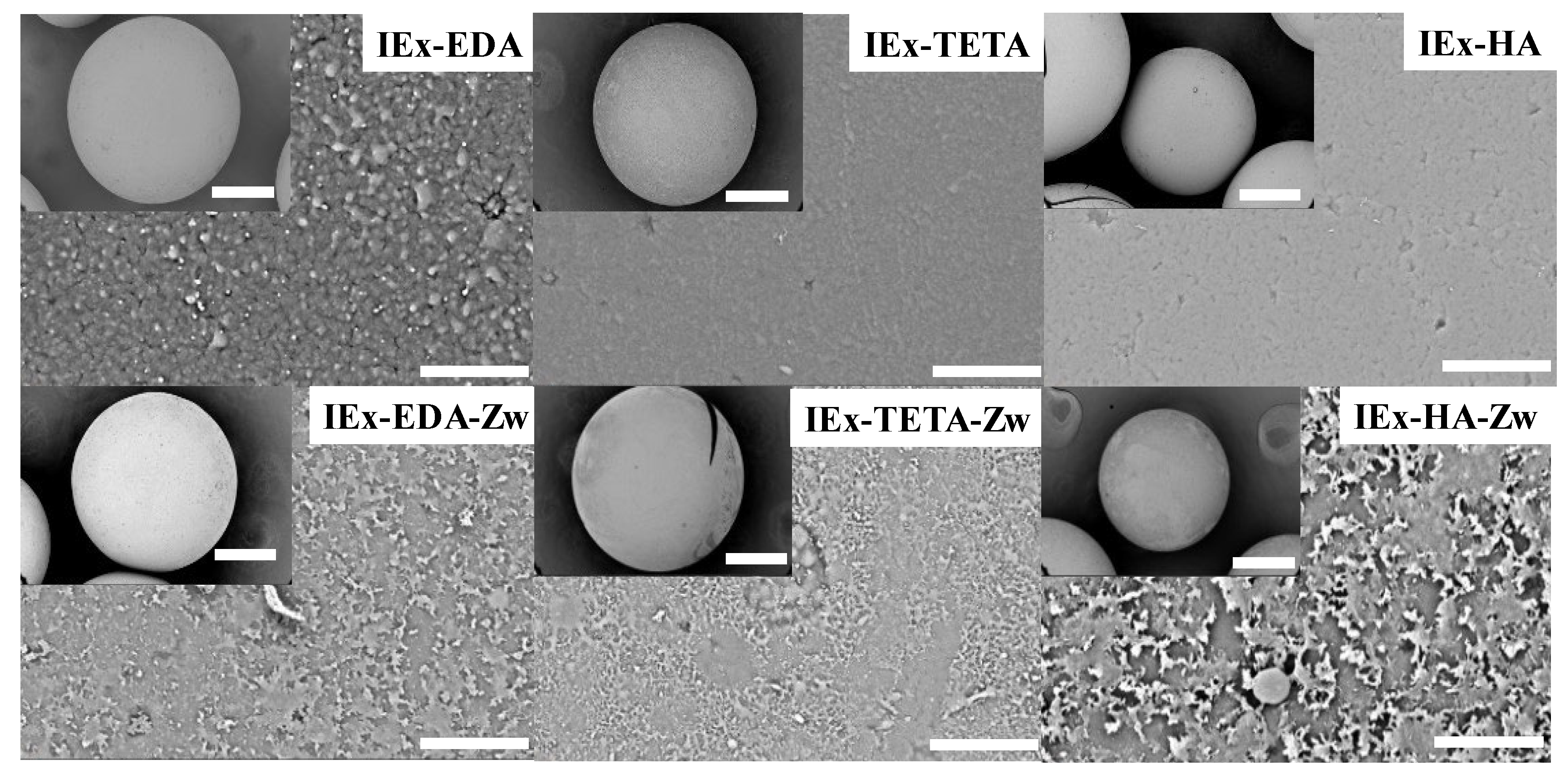

3.1. IExR Structural and Morphological Characterization

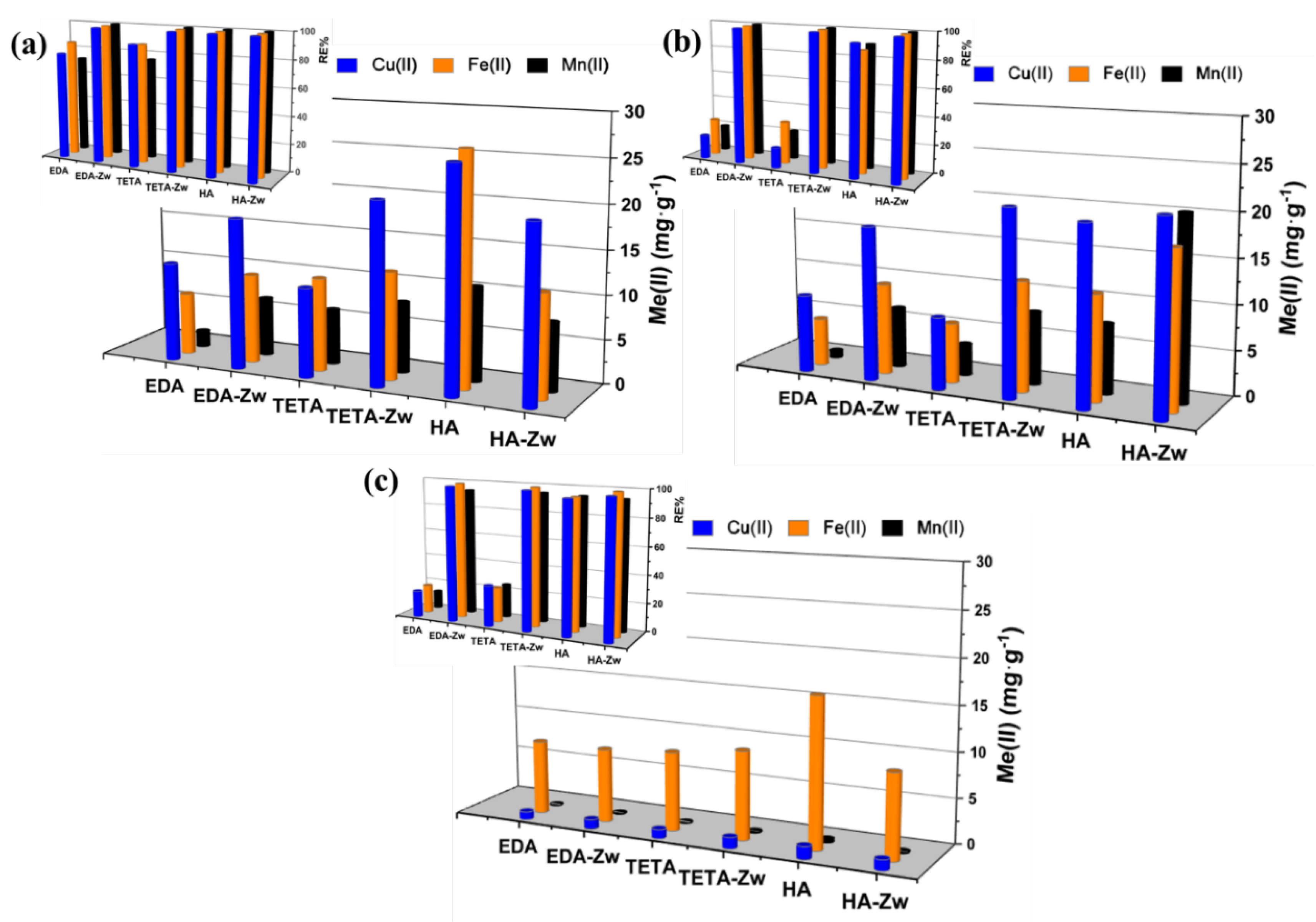

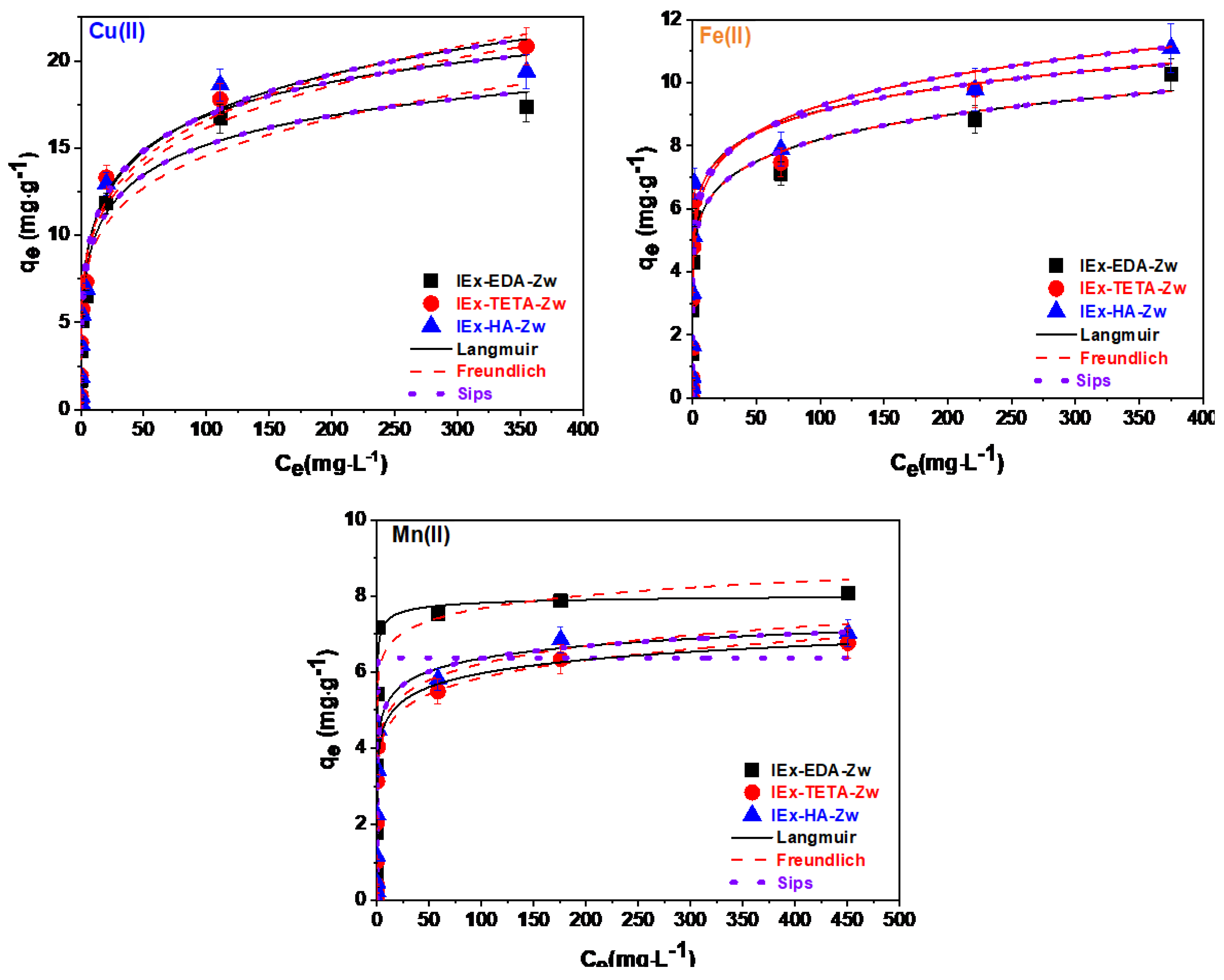

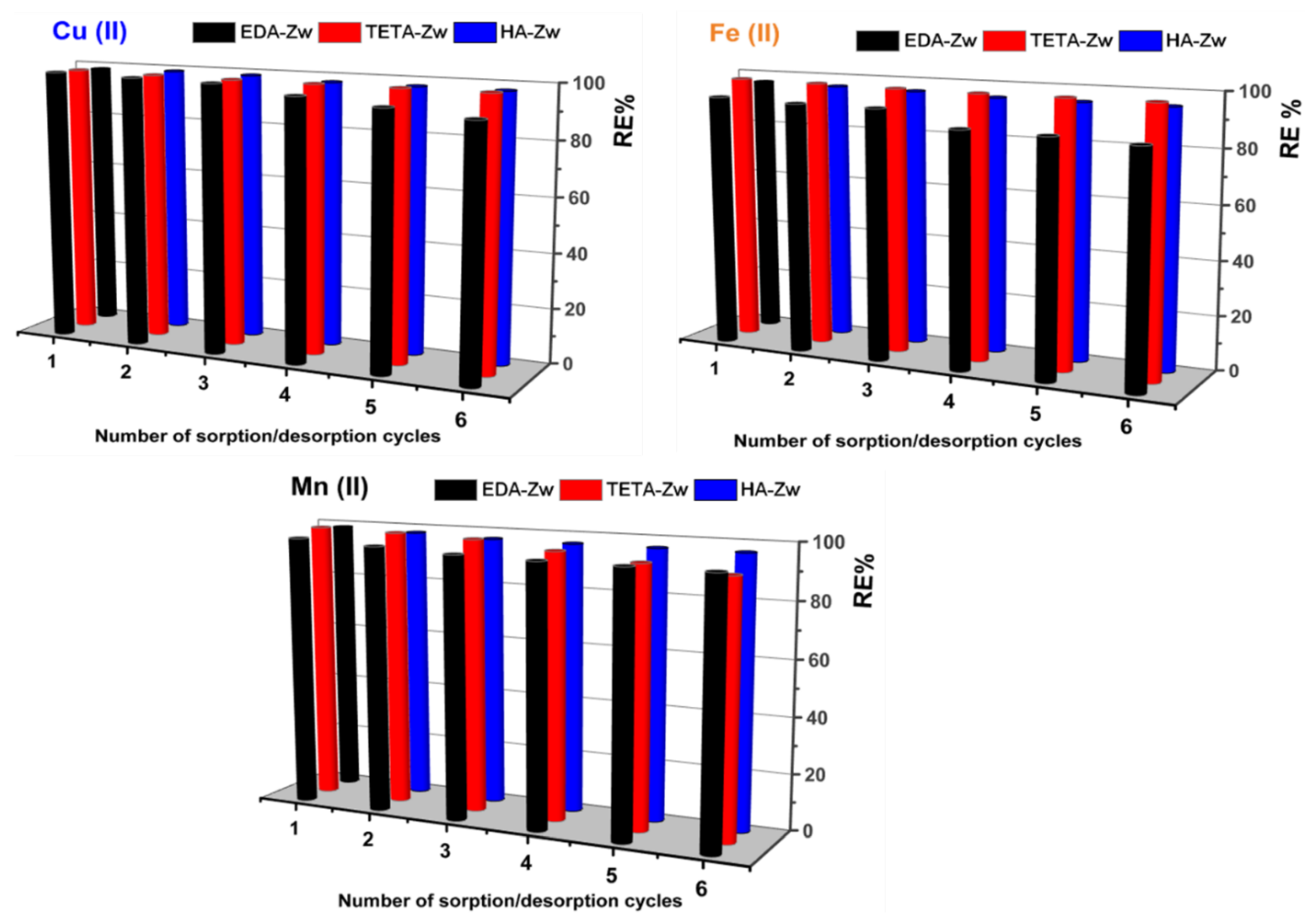

3.2. Application of Zwitterionic IExR

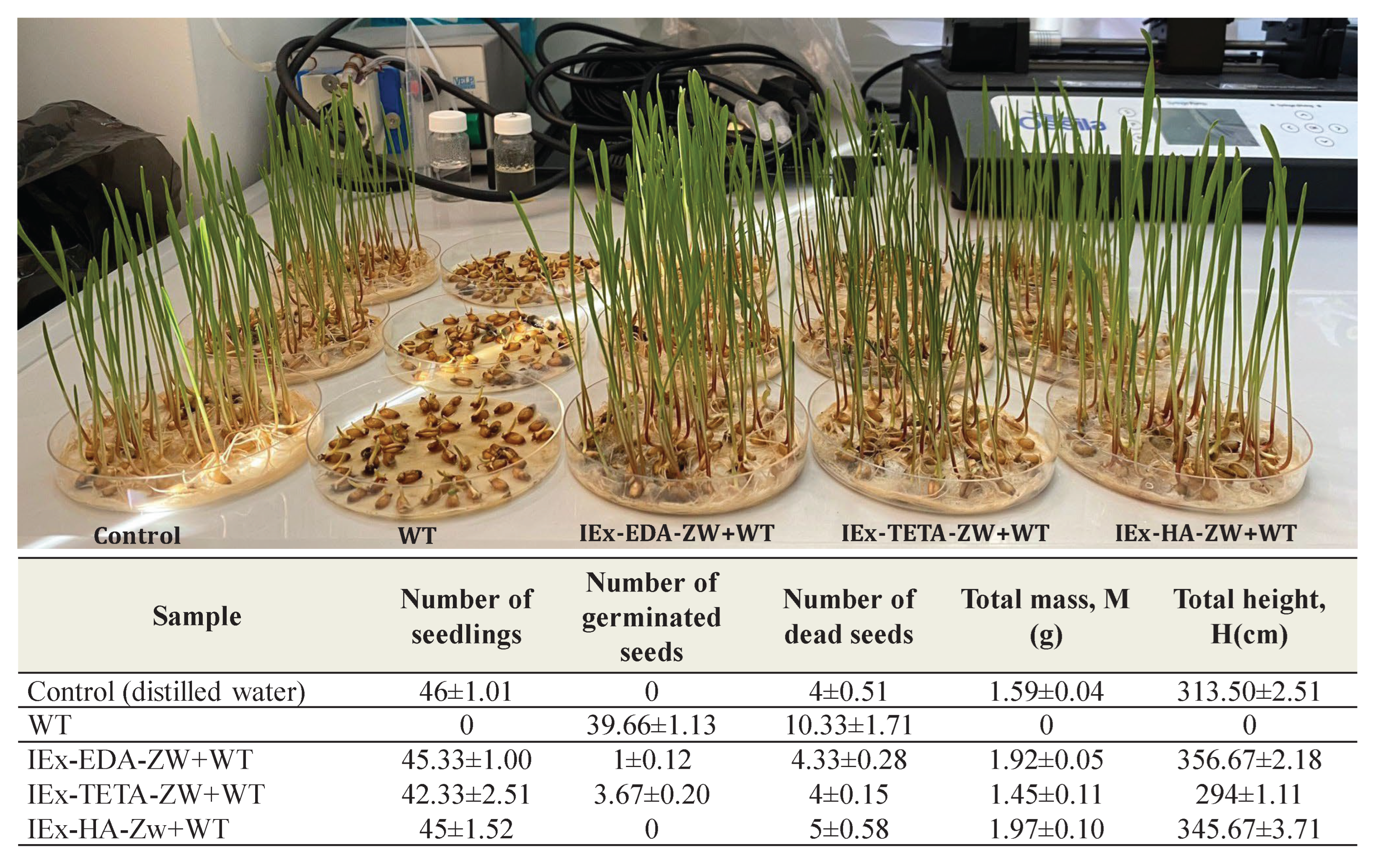

3.3. Wheat Germination Tests

4. Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- S Sharafi, S.; Salehi, F. Comprehensive assessment of heavy metal (HMs) contamination and associated health risks in agricultural soils and groundwater proximal to industrial sites. Sci Rep 2025, 15, 7518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagaba, A.H.; Lawal, I.M.; Birniwa, A.H.; Affam, A.C.; Usman, A.K.; Soja, U.B.; Saleh, D.; Hussaini, A.; Noor, A.; Yaro, N.S.A. Sources of water contamination by heavy metals. In Membrane technologies for heavy metal removal from water, 1st Edition, Boca Raton, CRC Press, 2024; pp. 3–27. [CrossRef]

- Thakur, S.; Chandra, A.; Kumar, V.; Bharti, S. Environmental pollutants: endocrine disruptors/pesticides/reactive dyes and inorganic toxic compounds metals, radionuclides, and metalloids and their impact on the ecosystem. In Biotechnology for environmental sustainability, Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore, 2025; pp. 55–100. [CrossRef]

- Raghavendra, N. Drinking water contamination and its solving approaches: a comprehensive review of current knowledge and future directions. Water, Air, & Soil Pollut. 2024, 235, 639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Chen, Y.; Xia, Q.; Rong, G.; Zhang, J. Ecological risk and early warning of soil compound pollutants (HMs, PAHs, PCBs and OCPs) in an industrial city, Changchun, China. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 272, 116038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Thakur, A.; Somya, A.; Zarrouk, A.; Dagdag, O.; Berdimurodov, E. Sorbents Developed from Spent Ion Exchangers for Heavy Metal Removal. In Ion Exchange Processes for Water and Environment Management, Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore, 2025; pp. 169–206. [CrossRef]

- Angon, P.B.; Islam, M.S.; Das, A.; Anjum, N.; Poudel, A.; Suchi, S.A. Sources, effects and present perspectives of heavy metals contamination: Soil, plants and human food chain. Heliyon 2024, 10, e28357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shukla, A.K.; Pradhan, M.; Tiwari, O.N. Heavy metal contamination of surface sediments-soil adjoining the largest copper mine waste dump in central India using multivariate pattern recognition techniques and geo-statistical mapping. Nat. Environ. Pollut. Technol. 2024, 23, 1363–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingo, J.P.T.; Jenkin, G.R.; Quick, L.; Williams, R.D.; Hudson-Edwards, K.A.; Tortajada, C.; Byrne, P.; Coulthard, T.J.; Padrones, J.T.; Crane, R.; Gibaga, C.R.L. Sustainable mining in tropical, biodiverse landscapes: environmental challenges and opportunities in the archipelagic Philippines. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 468, 143114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sengupta, M. Environmental impacts of mining: monitoring, restoration, and control. 2nd Edition, Boca Raton, CRC Press, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Necula, R.; Zaharia, M.; Butnariu, A.; Zamfirache, M.M.; Surleva, A.; Ciobanu, C.I.; Pintilie, O.; Iacoban, C.; Drochioiu, G. Heavy metals and arsenic in an abandoned barite mining area: ecological risk assessment using biomarkers. Environ. Forensics, 2023; 24, 164–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittelstädt, P.; Pollmann, N.; Karimzadeh, L.; Kories, H.; Klinger, C. Wastes in Underground Coal Mines and Their Behavior during Mine Water Level Rebound—A Review. Minerals 2023, 13, 1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuciurean, C.I.; Sidor, C.G.; Camarero, J.J.; Buculei, A.; Badea, O. Detecting changes in industrial pollution by analyzing heavy metal concentrations in tree-ring wood from Romanian conifer forests. Environ. Res. 2024, 252, 118884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radu, V.M.; Vîjdea, A.M.; Ivanov, A.A.; Alexe, V.E.; Dincă, G.; Cetean, V.M.; Filiuță, A.E. Research on the closure and remediation processes of mining areas in Romania and approaches to the strategy for heavy metal pollution remediation. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidor, C.G.; Vlad, R.; Popa, I.; Semeniuc, A.; Apostol, E.; Badea, O. Impact of industrial pollution on radial growth of conifers in a former mining area in the eastern Carpathians (northern Romania). Forests 2021, 12, 640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaharia, M.M.; Bucatariu, F.; Vasiliu, A.L.; Mihai, M. Stable and reusable acrylic ion-exchangers. From HMIs highly polluted tailing pond to safe and clean water. Chemosphere 2022, 304, 135383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization, Guidelines for drinking-water quality, fourth edition incorporating the first and second addenda, World Health Organization. 2022. Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/352532/9789240045064-eng.pdf?sequence=1ISBN 978-92-4-004506-4.

- Guidance Document No. 38 Technical Guidance for implementing Environmental Quality Standards (EQS) for metals, Consideration of metal bioavailability and natural background concentrations in assessing compliance, Common Implementation Strategy for the Water Framework Directive (2000/60/EC, European Commission. 2019. Available online: https://circabc.europa.eu/sd/a/a705289f-7001-4c7d-ac7c-1cf8140e2117/Guidance%20No%2038%20-%20Technical%20guidance%20for%20EQS%20for%20metals.pdf.

- Yu, Z.; Yu, Q.J.; Wu, Y.; Ding, K. Uptake of aqueous heavy metal ions (HMIs) by various biomasses and non-biological materials: a mini review of adsorption capacities, mechanisms and processes. Int. J. Environ. Anal. Chem. 2023, 103, 8416–8427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhadra, M.A.; Su, X.; Suss, M.E.; Tian, H.; Guyes, E.N.; Shocron, A.N.; Conforti, K.M.; De Souza, J.P.; Kim, N.; Tedesco, M.; Khoiruddin, K. Electrochemical methods for water purification, ion separations, and energy conversion. Chem. Rev. 2022, 122, 13547–13635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oladimeji, T.E.; Oyedemi, M.; Emetere, M.E.; Agboola, O.; Adeoye, J.B.; Odunlami, O.A. Review on the impact of heavy metals from industrial wastewater effluent and removal technologies. Heliyon 2024, 10, e40370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akhtar, M.S.; Ali, S.; Zaman, W. Innovative adsorbents for pollutant removal: exploring the latest research and applications. Molecules 2024, 29, 4317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayan, P.P.; Chithra, P.G.; Krishna, S.V.A.; Ansar, E.B.; Parameswaranpillai, J. Development and current trends on ion exchange materials. Sep. Purif. Rev. 2024, 53, 40–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Sadia, M.; Azeem, M.; Ahmad, M.Z.; Umar, M.; Abbas, Z.U. Ion exchange resins and their applications in water treatment and pollutants removal from environment: A review: Ion exchange resins and their applications. Futuristic Biotechnology 2023, 3, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Zhang, L.; Yuan, L.; Ji, C.; Zhang, Y.; Kong, D.; Zhang, Y.; Lv, L.; Hua, M.; Zhang, W. Machine learning-assisted adsorption capacity prediction of ion exchange or chelate resin for heavy metals in aqueous solutions: External validation via multi-factor experiments. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 368, 133019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohebbi, A.; Abolghasemi Mahani, A.; Izadi, A. Ion exchange resin technology in recovery of precious and noble metals. In Applications of Ion Exchange Materials in Chemical and Food Industries, Cham: Springer International Publishing. 2019; pp. 193–258. [CrossRef]

- Marin, N.M.; Nita Lazar, M.; Popa, M.; Galaon, T.; Pascu, L.F. Current trends in development and use of polymeric ion-exchange resins in wastewater treatment. Materials 2024, 17, 5994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clemens, A.L.; Jayathilake, B.S.; Karnes, J.J.; Schwartz, J.J.; Baker, S.E.; Duoss, E.B.; Oakdale, J.S. Tuning alkaline anion exchange membranes through crosslinking: a review of synthetic strategies and property relationships. Polymers 2023, 15, 1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, S.; Feng, X.; Liu, C.; Wu, H.; Liu, X. Advances in chelating resins for adsorption of heavy metal ions. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2022, 61, 11309–11328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermassi, M.; Granados, M.; Valderrama, C.; Skoglund, N.; Ayora, C.; Cortina, J.L. Impact of functional group types in ion exchange resins on rare earth element recovery from treated acid mine waters. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 379, 134742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Song, J.; Chen, Y.; Xiao, H.; Shi, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, L.; He, Y.L.; Chen, X. CO2 absorption over ion exchange resins: the effect of amine functional groups and microporous structures. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2020, 59, 16507–16515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akitsu, T. Electrophile and Lewis Acid. BoD–Books on Demand. IntechOpen, eBook (PDF) ISBN978-1-83769-572-0, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Pramanik, A.K.; Tamang, N.; Chatterjee, A.; Bhattarai, A.; Saha, B. Ion exchange resins for selective separation of toxic metals. Mater. Res. Found. 2023, 137, 55–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, A.P.; Gellineau, H.A.; MacMillan, S.N.; Wilson, J.J. Physical properties, ligand substitution reactions, and biological activity of Co (III)-Schiff base complexes. Dalton Trans. 2019, 48, 987–6002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaharia, M.M.; Vasiliu, A.L.; Trofin, M.A.; Pamfil, D.; Bucatariu, F.; Racovita, S.; Mihai, M. Design of multifunctional composite materials based on acrylic ion exchangers and CaCO3 as sorbents for small organic molecules. React. Func. Polym. 2021, 166, 104997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, M.L.; Valentino, L.; Nazyrynbekova, N.; Palakkal, V.M.; Kole, S.; Bhattacharya, D.; Lin, Y.J.; Arges, C.G. Promoting water-splitting in Janus bipolar ion-exchange resin wafers for electrode ionization. Mol. Syst. Des. Eng. 2020, 5, 922–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaharia, M.M.; Bucatariu, F.; Vasiliu, A.L.; Mihai, M. Versatile Zwitterionic Beads for Heavy Metal Ion Removal from Aqueous Media and Soils by Sorption and Catalysis Processes. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2023, 5, 8183–8193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccin, J.S.; Cadaval Jr, T.R.S.A.; De Pinto, L.A.A.; Dotto, G.L. Adsorption isotherms in liquid phase: experimental, modeling, and interpretations. In Adsorption processes for water treatment and purification, Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2017; pp. 19–51. [CrossRef]

| IEx resins | E(acid) | E(basic) | Wv | Mean diameter | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mEq·mL-1 | mEq·g-1 | mEq·mL-1 | mEq·g-1 | g·mL-1 | mm | |

| IEx-EDA | 1.154 | 2.859 | 0.295 | 0.318 | ||

| IEx-EDA-Zw | 4.669 | 4.859 | 0.959 | 3.311 | 0.188 | 0.509 |

| IEx-TETA | 2.067 | 5.650 | 0.390 | 0.422 | ||

| IEx-TETA-Zw | 1.646 | 2.803 | 1.334 | 6.806 | 0.157 | 0.611 |

| IEx-HA | 0.259 | 14.281 | 0.054 | 0.235 | ||

| IEx-HA-Zw | 1.392 | 4.828 | 2.153 | 3.212 | 0.164 | 0.325 |

| Sample | Cu(II) (mg·L-1) | Fe(II) (mg·L-1) | Mn(II) (mg·L-1) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MoHMI | MuHMI | WT | MoHMI | MuHMI | WT | MoHMI | MuHMI | WT | |

| IEx-EDA | 2.36 | 4.58 | 14.92 | 7.37 | 10.62 | 110.53 | 3.44 | 15.16 | 1.71 |

| IEx-EDA-Zw | 0.23 | 0.85 | 0.12 | 0.13 | 0.16 | 0.18 | 0.12 | 0.28 | 0.13 |

| IEx-TETA | 6.78 | 9.58 | 12.89 | 3.56 | 12.09 | 116.85 | 3.91 | 16.65 | 35.2 |

| IEx-TETA-Zw | 0.15 | 0.5 | 0.11 | 0.10 | 0.12 | 0.16 | 0.1 | 0.24 | 0.1 |

| IEx-HA | 0.36 | 1.12 | 1.09 | 0.11 | 0.21 | 0.19 | 0.17 | 0.29 | 0.23 |

| IEx-HA-Zw | 0.37 | 0.84 | 0.29 | 0.12 | 0.19 | 0.15 | 0.22 | 0.27 | 0.18 |

| IEx resins | HMIs | ISOTHERM MODEL | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Langmuir | Freundlich | Sips | |||||||||

| qm, (mg·g-1) | KL, (L·mg-1) | R2 |

KF, (L ·g−1) |

1·n-1 | R2 | qm, (mg·g-1) | aS | 1·n-1 | R2 | ||

| IEx-EDA-Zw | Cu(II) | 28.54 | 0.23 | 0.9343 | 5.88 | 0.20 | 0.9357 | 28.48 | 0.35 | 0.23 | 0.96601 |

| Fe(II) | 523.74 | 0.01 | 0.9169 | 4.51 | 0.13 | 0.9377 | 498.97 | 0.13 | 0.01 | 0.9556 | |

| Mn(II) | 8.16 | 3.64 | 0.9166 | 5.75 | 0.06 | 0.7750 | - | - | - | - | |

| IEx-TETA-Zw | Cu(II) | 56.99 | 0.12 | 0.9612 | 6.44 | 0.21 | 0.9679 | 56.77 | 0.27 | 0.12 | 0.9748 |

| Fe(II) | 2297.14 | 0.02 | 0.8603 | 4.89 | 0.14 | 0.8954 | 2083.85 | 0.14 | 0.01 | 0.9398 | |

| Mn(II) | 10.89 | 0.50 | 0.9841 | 3.53 | 0.11 | 0.9796 | 10.89 | 0.19 | 0.50 | 0.9703 | |

| IEx-HA-Zw | Cu(II) | 31.80 | 0.22 | 0.9300 | 6.35 | 0.21 | 0.9330 | 31.72 | 0.36 | 0.22 | 0.9638 |

| Fe(II) | 204.13 | 0.03 | 0.8858 | 5.33 | 0.12 | 0.9144 | 197.83 | 0.12 | 0.03 | 0.9470 | |

| Mn(II) | 9.99 | 0.66 | 0.9714 | 3.86 | 0.10 | 0.9644 | 9.99 | 0.21 | 0.67 | 0.9637 | |

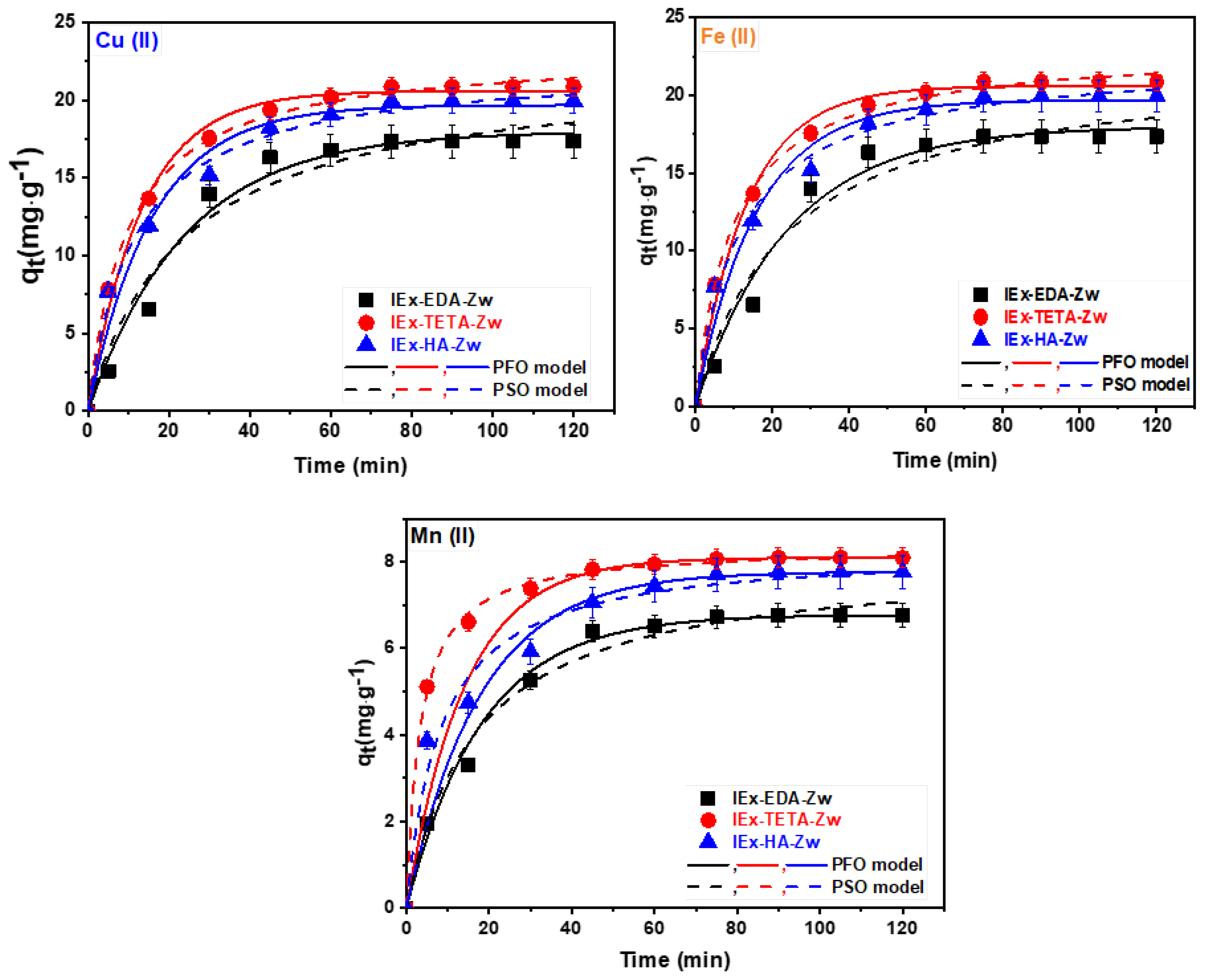

| Parameter | IEx-EDA-Zw | IEx-TETA-Zw | IEx-HA-Zw | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cu(II) | Fe(II) | Mn(II) | Cu(II) | Fe(II) | Mn(II) | Cu(II) | Fe(II) | Mn(II) | ||

| Exp. | qe,exp, (mg·g-1) | 17.40 | 10.27 | 6.78 | 20.84 | 12.30 | 8.12 | 19.94 | 11.77 | 7.76 |

| PFO | qe,cal, (mg·g-1) k1, (min-1) R2 χ2 |

17.98 4.16·10-2 0.9831 0.89 |

10.71 4.23·10-2 0.9661 0.65 |

6.78 5.45·10-2 0.9918 0.06 |

20.59 7.51·10-2 0.9925 0.42 |

12 10.73·10-2 0.9824 0.29 |

8.10 7.09·10-2 0.8456 1.13 |

19.68 6.33·10-2 0.9792 1.07 |

11.30 16.38·10-2 0.9565 0.67 |

7.77 5.61·10-2 0.9284 0. 52 |

| PSO | qe,cal, (mg·g-1) k2, (min-1) R2 χ2 |

13.95 1.48·10-3 0.4175 30.51 |

13.24 3.22·10-3 0.9438 1.08 |

8.06 7.48·10-3 0.9860 0.09 |

18.01 1.88·10-3 0.6430 20.26 |

13.14 1.15·10-3 0.9985 0.03 |

8.35 2.07·10-3 0.9985 0.01 |

22.31 3.88·10-3 0.9915 0.40 |

12.09 3.35·10-3 0.9885 0.18 |

8.32 3.08·10-3 0.9765 0.17 |

| IEx resins | HMIs | ΔHo, (kJ·mol-1) |

ΔSo, (kJ·mol-1·K-1) |

ΔGo, (kJ·mol-1) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 293.15 K | 298.15 K | 303.15 K | 313.15 K | ||||

| IEx-EDA-Zw | Cu(II) | -217.981 | -0.709 | -9.505 | -5.963 | -2.420 | -0.664 |

| Fe(II) | -300.271 | -0.100 | -5.816 | -3.793 | -2.229 | -1.274 | |

| Mn(II) | -237.301 | -0.791 | -5.350 | -4.394 | -3.562 | -1.474 | |

| IEx-TETA-Zw | Cu(II) | -364.445 | -1.189 | -15.837 | -9.891 | -3.945 | -0.947 |

| Fe(II) | -334.404 | -1.099 | -12.307 | -6.813 | -1.319 | -0.468 | |

| Mn(II) | -238.406 | -0.795 | -5.395 | -1.420 | -0.754 | -0.350 | |

| IEx-HA-Zw | Cu(II) | -377.505 | -1.231 | -16.662 | -10.507 | -4.353 | -2.956 |

| Fe(II) | -232.049 | -0.775 | -4.811 | -2.936 | -1.940 | -0.692 | |

| Mn(II) | -215.410 | -0.706 | -8.388 | -4.857 | -1.326 | -0.737 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).