Submitted:

24 October 2025

Posted:

29 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Proximate Analysis of Pistachio

2.3. Analysis of Particle Size Distribution

2.4. Color Analysis

2.5. Oil Separation Rate

2.6. Rheological Analysis

2.7. Sensory Analysis

2.8. Instrumental Textural Analysis

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Composition of Pistachio

3.2. Particle Size Distribution of Pistachio Pastes

3.3. Color Values of Pistachio Pastes and Spreads

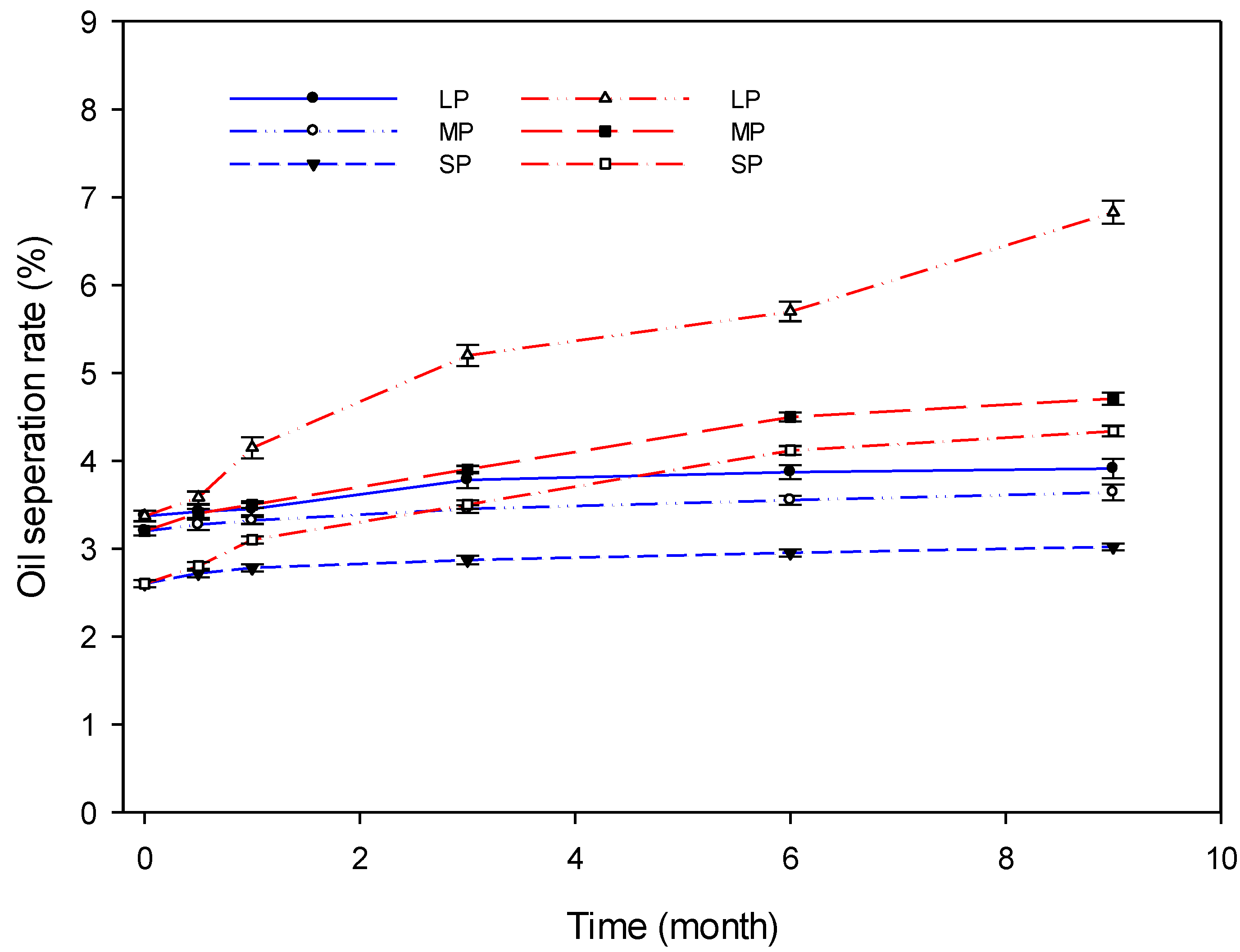

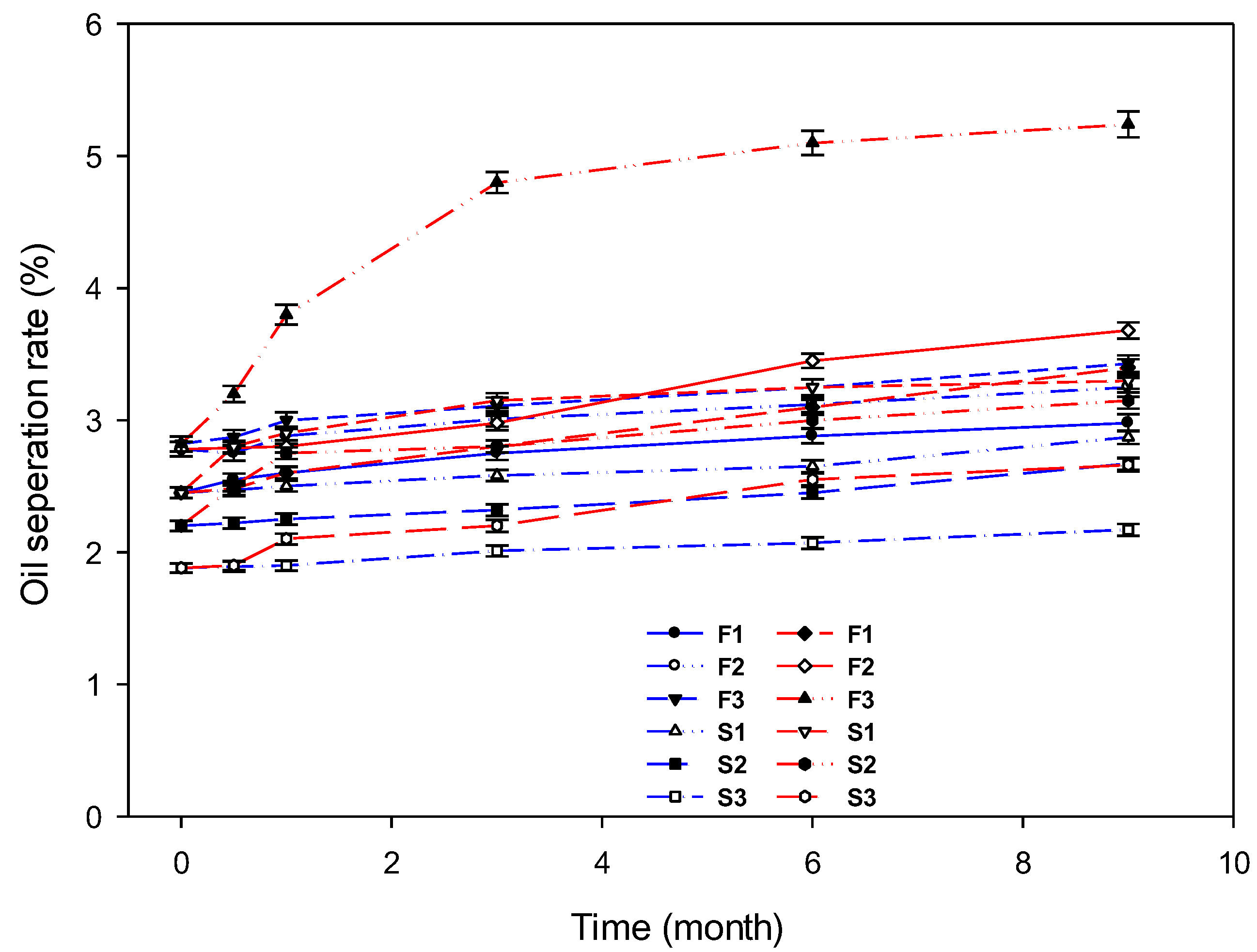

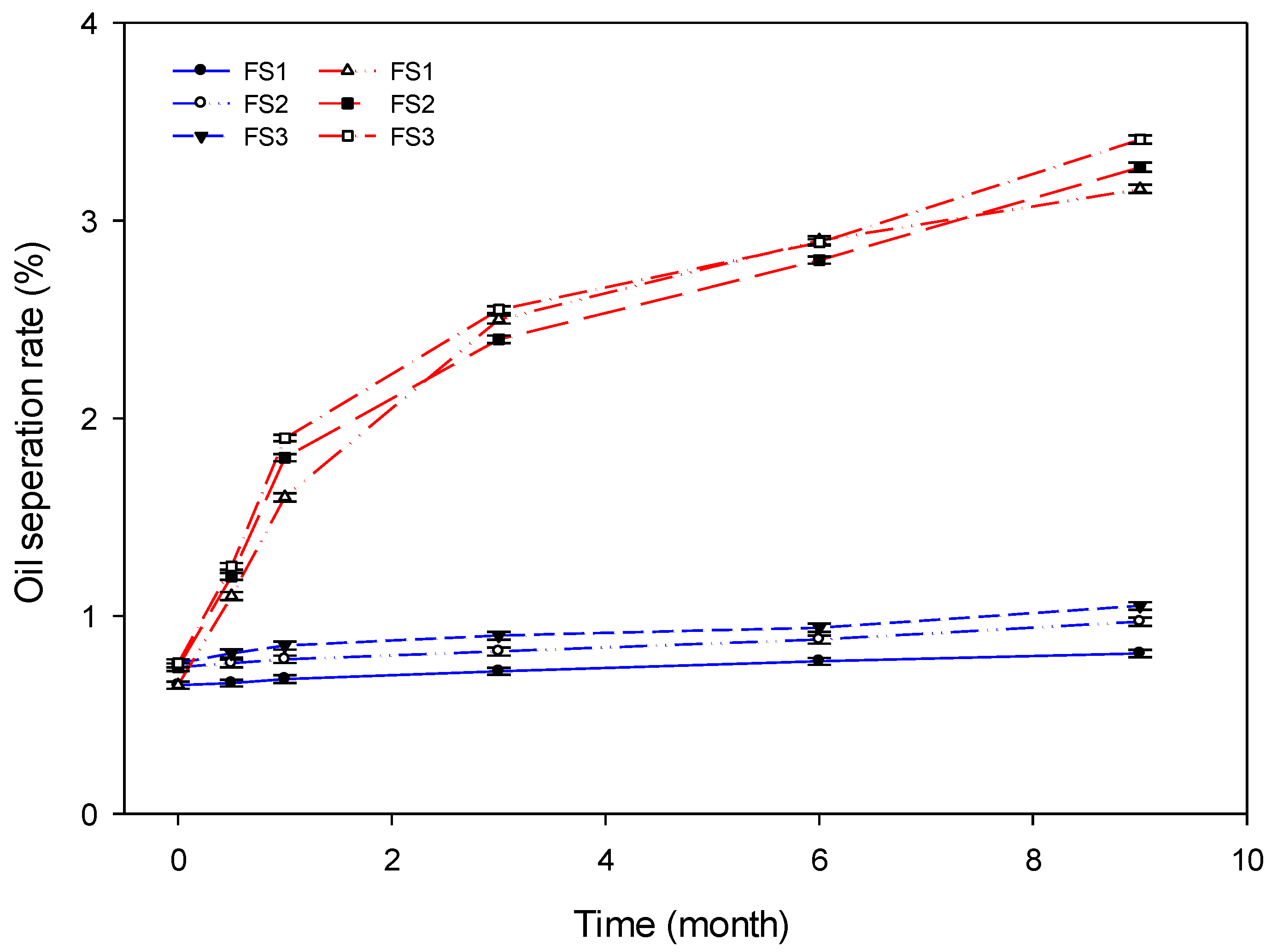

3.4. Oil Separation Rate of Pistachio Spreads and Pastes

3.5.1. Effect of Milk Fat

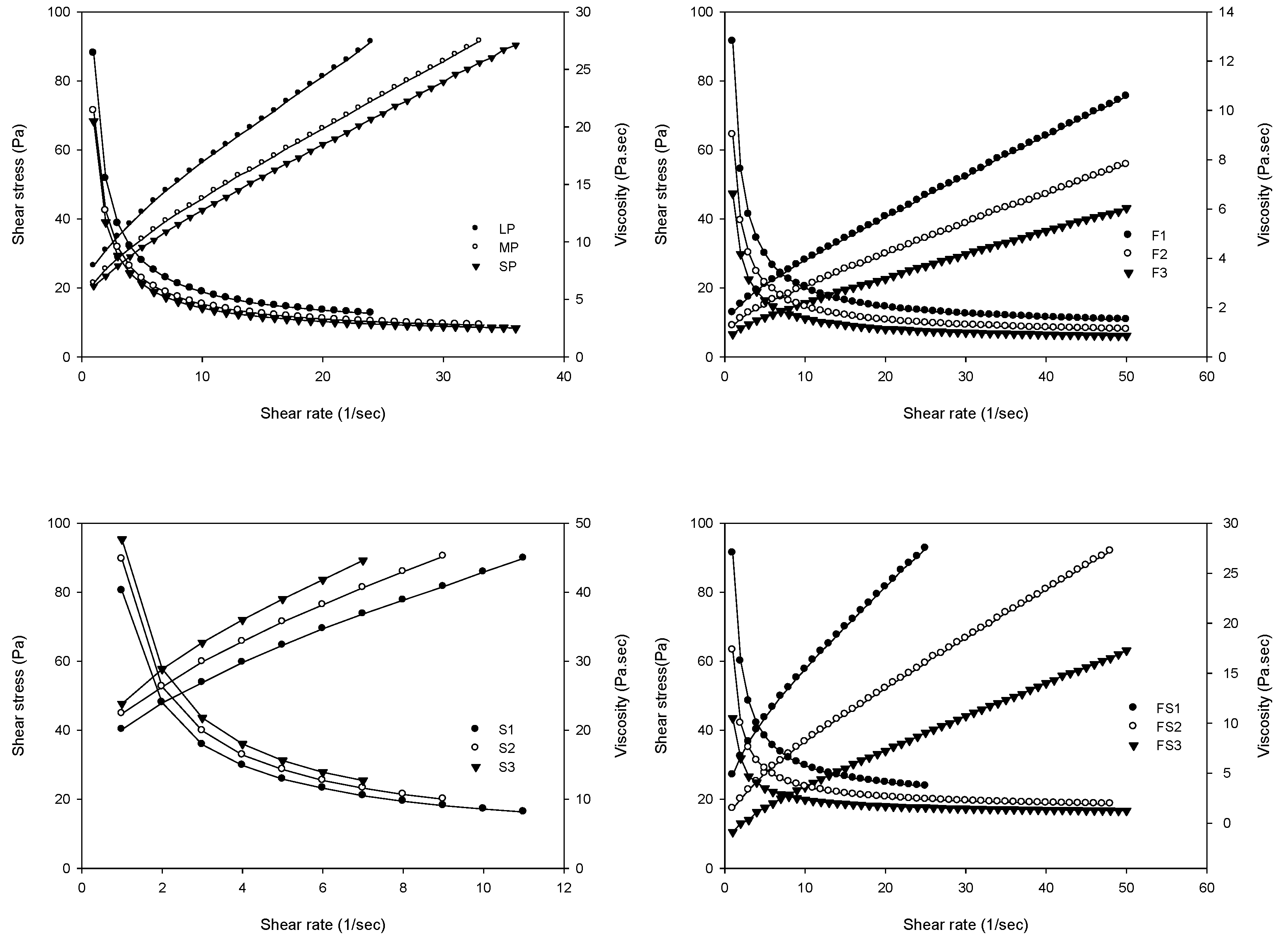

3.5. Rheological Analysis

3.5.2. Effect of Sugar

3.5.3. Combined Effect of Milk Fat and Sugar

3.6. Textural Analysis

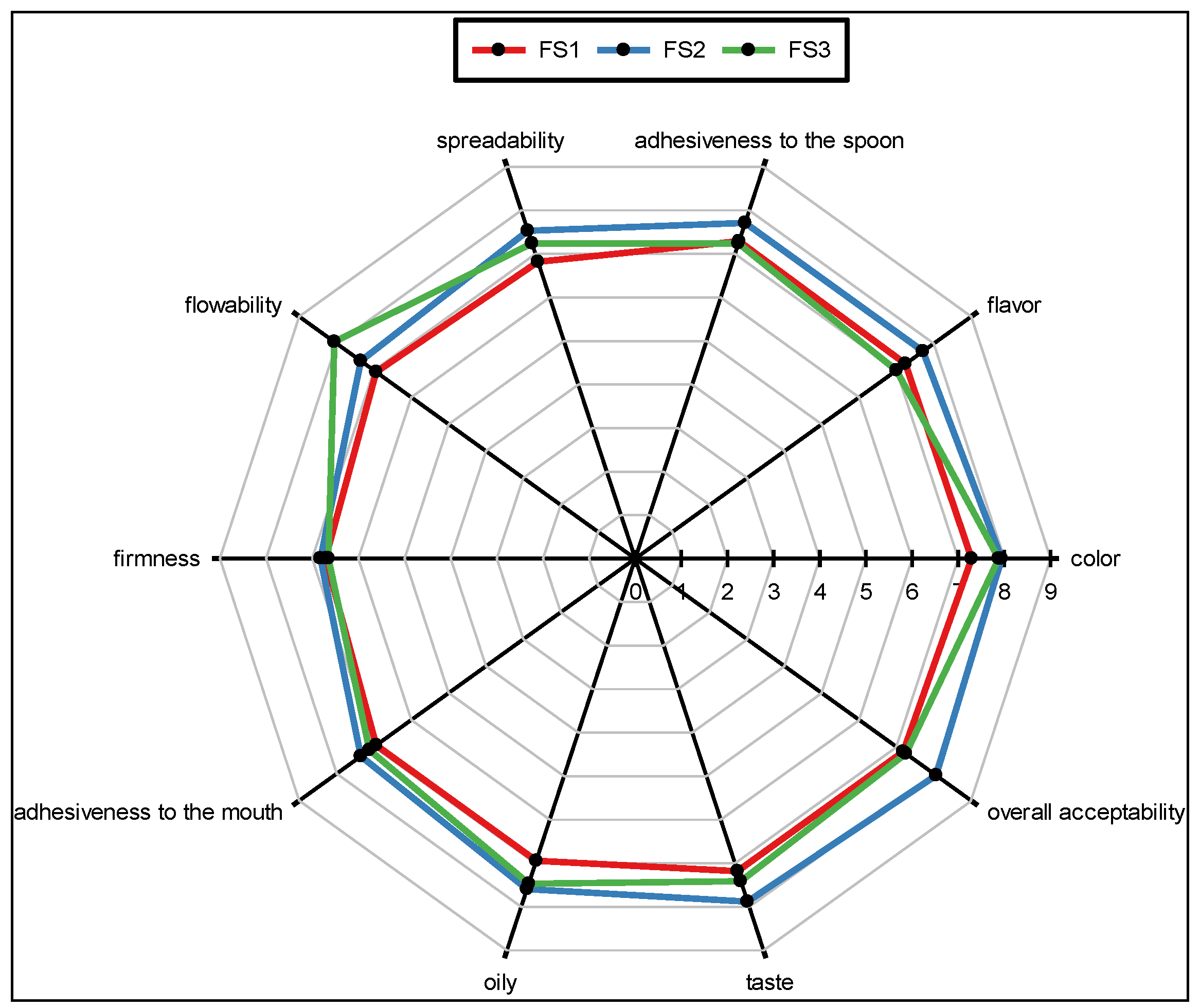

3.7. Sensory Analysis

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Sample | 20 °C | 25 °C | 30 °C | 35 °C | 40 °C | 45 °C |

| LP MP SP F1 F2 F3 S1 S2 S3 FS1 FS2 FS3 |

15.70±0.70f 11.47±0.20e 9.76±0.64d 6.05±0.01b 4.76±0.05a 6.88±0.22c nd nd nd 19.01±0.21g 9.12±0.46d 15.22±0.19f |

11.28±0.66h 8.91±0.29g 7.94±0.25f 4.46±0.07c 3.19±0.01b 2.73±0.11a nd nd nd 12.96±0.20i 7.06±0.05e 6.16±0.05d |

9.28±0.10h 6.95±0.10g 6.18±0.13f 3.65±0.06d 2.46±0.03b 1.94±0.01a 17.28±0.73j 20.01±0.50k nd 10.18±0.21i 5.06±0.10e 2.97±0.04c |

7.42±0.10g 5.65±0.10f 5.10±0.14e 2.98±0.06c 2.00±0.06a 1.69±0.02a 15.43±0.04i 17.54±0.21j 25.16±0.62k 8.37±0.17h 4.02±0.05d 2.48±0.02b |

6.50±0.27g 4.80±0.10f 4.20±0.10e 2.45±0.02c 1.86±0.01b 1.47±0.01a 13.90±0.25i 15.88±0.29j 22.58±0.35k 7.61±0.07h 3.39±0.06d 2.19±0.01c |

5.38±0.21f 4.14±0.15e 3.53±0.01d 2.22±0.02c 1.59±0.09ab 1.33±0.02a 13.03±0.27h 14.62±0.52i 19.96±0.76j 7.20±032g 3.16±0.04d 2.03±0.04bc |

References

- Mateos, R.; Salvador, M.D.; Fregapane, G.; Goya, L. Why Should Pistachio Be a Regular Food in Our Diet? Nutrients 2022, 14, 3207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kola, O.; Hayoğlu, İ.; Türkoğlu, H.; Parıldı, E.; Ak, B.E.; Akkaya, M.R. Physical and Chemical Properties of Some Pistachio Varieties (Pistacia vera L.) and Oils Grown under Irrigated and Non-Irrigated Conditions in Turkey. Quality Assurance and Safety of Crops & Foods 2018, 10, 383–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulló, M.; Juanola-Falgarona, M.; Hernández-Alonso, P.; Salas-Salvadó, J. Nutrition Attributes and Health Effects of Pistachio Nuts. Br J Nutr 2015, 113, S79–S93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Nut and Dried Fruit Council (INC). (2024).Global statistical yearbook 2024: World tree nut and dried fruit production and consumption trends. International Nut and Dried Fruit Council. https://www.nutfruit.org. (25.09.2025).

- Turkish Statistical Institute (TÜİK). (2024). Plant production statistics 2024: Pistachio (Antep fıstığı) production by region. Turkish Statistical Institute. https://data.tuik.gov.tr (25.09.2025).

- Mandalari, G.; Barreca, D.; Gervasi, T.; Roussell, M.A.; Klein, B.; Feeney, M.J.; Carughi, A. Pistachio Nuts (Pistacia vera L.): Production, Nutrients, Bioactives and Novel Health Effects. Plants 2022, 11, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellomo, M.G.; Fallico, B. Anthocyanins, Chlorophylls and Xanthophylls in Pistachio Nuts (Pistacia Vera) of Different Geographic Origin. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis 2007, 20, 352–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. (2025). Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2025/1245 of 25 June 2025 entering “Antep Fıstığı Ezmesi” into the register of protected geographical indications (PGI). Official Journal of the European Union. https://eur-lex.europa.eu. (28.08.2025).

- Steffe, J.F. Rheological Methods in Food Process Engineering; Freeman Press: East Lansing, MI, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Shakerardekani, A. Effect of Milling Process on Colloidal Stability, Color and Rheological Properties of Pistachio Paste. Journal of Nuts 2014, 05. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghizadeh, M.; Razavi, S.M.A. Modeling Time-Independent Rheological Behavior of Pistachio Butter. International Journal of Food Properties, 2009, 12, 331–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczesniak, A. S. Texture is a sensory property. Food Quality and Preference, 2002, 13, 215–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ditschun, T.L.; Riddell, E.; Qin, W.; Graves, K.; Jegede, O.; Sharafbafi, N.; Pendergast, T.; Chidichimo, D.; Wilson, S.F. Overview of Mouthfeel from the Perspective of Sensory Scientists in Industry. Comp Rev Food Sci Food Safe 2025, 24, e70126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shakerardekani, A. Consumer Acceptance and Quantitative Descriptive Analysis of Pistachio Spread. Journal of Agricultural Science and Technology 2017, 19: 85–95.

- https://jast.modares.ac.ir/article-23-1009-en.

- Shuai, X. , Li, Y. , Zhang, Y., Wei, C., Zhang, M., & Du, L. Gelation of whole macadamia butter by different oleogelators affects the physicochemical properties and applications. LWT, 2024, 198, 115961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahidi-Noghabi, M. , Naji-Tabasi, S. , & Sarraf, M. Effect of emulsifier on rheological, textural and microstructure properties of walnut butter. Journal of Food Measurement and Characterization, 2018, 13, 785–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L. , Huan, Y. , & Shi, C. Effect of Sorbitol on Rheological, Textural and Microstructural Characteristics of Peanut Butter. Food Science and Technology Research, 2014, 20, 739–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagener, E. A. , & Kerr, W. L. Effects of oil content on the sensory, textural, and physical properties of pecan butter (Carya illinoinensis). Journal of Texture Studies, 2017, 49, 286–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Principato, L. , Carullo, D., Gruppi, A., Lambri, M., Bassani, A., & Spigno, G. Correlation of rheology and oral tribology with sensory perception of commercial hazelnut and cocoa-based spreads. Journal of Texture Studies, 2024, 55. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Xu, T.; Yang, R. Effect of Roasting and Grinding on the Processing Characteristics and Organoleptic Properties of Sesame Butter. Euro J Lipid Sci Tech 2019, 121, 1800401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekmez, H.; Özkanlı, O.; Şekeroğlu, G.; Kaya, A. Influence of Particle Size on the Color, Rheological, and Textural Properties of Sesame Paste. Qual. Assur. Saf. Crops Foods 2025, 17, 146–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitlamani, V. , Huded, P. , Kumar, G. S., & Chetana, R. Development of high-fiber and high-protein virgin coconut oil-based spread and its physico-chemical and sensory qualities. Journal of Food Science and Technology, 2024, 61, 2196–2204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leahu, A. , Ghinea, C. , & Ropciuc, S. Rheological, Textural, and Sensorial Characterization of Walnut Butter. Applied Sciences, 2022, 12, 10976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Hou, L.; Yang, M.; Jin, L.; Liu, H.; Wang, X. An Evaluation of the Physicochemical Properties of Sesame Paste Produced by Ball Milling Compared against Conventional Colloid Milling. J. Oleo Sci. 2024, 73, 645–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Official Methods of Analysis of AOAC International; Latimer, G.W. Ed.; 22nd ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, 2023; ISBN 978-0-19-761013-8.

- Commission Internationale de l’Éclairage (CIE). Colorimetry. 4th ed.; CIE Publication No. V: 15:2018; CIE Central Bureau, 2018.

- Shakerardekani, A.; Karim, R.; Ghazali, H.M.; Chin, N.L. Development of Pistachio (Pistacia Vera L.) Spread. Journal of Food Science 2013, 78, doi:10.1111/1750-3841.12045. 2013, 78.

- Brighenti, M.; Govindasamy-Lucey, S.; Lim, K.; Nelson, K.; Lucey, J.A. Characterization of the Rheological, Textural, and Sensory Properties of Samples of Commercial US Cream Cheese with Different Fat Contents. Journal of Dairy Science 2008, 91, 4501–4517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arena, E.; Campisi, S.; Fallico, B.; Maccarone, E. Distribution of Fatty Acids and Phytosterols as a Criterion to Discriminate Geographic Origin of Pistachio Seeds. Food Chemistry 2007, 104, 403–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsantili, E.; Takidelli, C.; Christopoulos, M.V.; Lambrinea, E.; Rouskas, D.; Roussos, P.A. Physical, Compositional and Sensory Differences in Nuts among Pistachio (Pistachia Vera L.) Varieties. Scientia Horticulturae 2010, 125, 562–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, M.L.; Fabani, M.P.; Baroni, M.V.; Huaman, R.N.M.; Ighani, M.; Maestri, D.M.; Wunderlin, D.; Tapia, A.; Feresin, G.E. Argentinian Pistachio Oil and Flour: A Potential Novel Approach of Pistachio Nut Utilization. J Food Sci Technol 2016, 53, 2260–2269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jonge, N.; Kaszab, T.; Badak-Kerti, K. Physical Properties of Different Nut Butters. Progress 2023, 19, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakerardekani, A., & Karim, R. (2018). Optimization of Processing Variables for Pistachio Paste Production. Pistachio and Health Journal, 1. [CrossRef]

- Glicerina, V. , Balestra, F., Rosa, M. D., Bergenhstål, B., Tornberg, E., & Romani, S. (2014). The influence of different processing stages on particle size, microstructure, and appearance of dark chocolate. Journal of Food Science, 79, 1359–1365. [CrossRef]

- Shakerardekani, A.; Karim, R.; Ghazali, H.; Chin, N. Textural, Rheological and Sensory Properties and Oxidative Stability of Nut Spreads—A Review. IJMS 2013, 14, 4223–4241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayoglu, I.; Faruk Gamli, O. Water Sorption Isotherms of Pistachio Nut Paste. Int J of Food Sci Tech 2007, 42, 224–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuzer, M.O.; Genccelep, H. Effect of Sesame Protein/ PVA Nanofibers on Oil Separation and Rheological Properties in Sesame Paste. J Food Process Engineering 2024, 47, e14534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, Y.; Hou, X.; Yu, Y.; Wen, X.; Ding, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, Z. Improving the Thermal and Oxidative Stability of Food-Grade Phycocyanin from Arthrospira Platensis by Addition of Saccharides and Sugar Alcohols. Foods 2022, 11, 1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornacchia, L.; Roos, Y.H. Solid–Liquid Transitions and Stability of HPKO-in-Water Systems Emulsified by Dairy Proteins. Food Biophysics 2011, 6, 288–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Pan, Y.; Jia, X.; Li, J.; Zhang, M.; Yin, L. Review on the Stability Mechanism and Application of Water-in-Oil Emulsions Encapsulating Various Additives. Comp Rev Food Sci Food Safe 2019, 18, 1660–1675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Bao, H.; Jiang, M.; Zhu, W.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, R.; Zhu, K. Effect of Hot-air Drying on Drying Characteristics and Quality of Tiger Nut. J Sci Food Agric 2025, 105, 255–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walton, D.; Randall, B.; Poienou, M.; Nevenimo, T.; Moxon, J.; Wallace, H. Shelf Life of Tropical Canarium Nut Stored under Ambient Conditions. Horticulturae 2017, 3, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faruk Gamlı, Ö.; Hayoğlu, İ. The Effect of the Different Packaging and Storage Conditions on the Quality of Pistachio Nut Paste. Journal of Food Engineering 2007, 78, 443–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emadzadeh, B.; Razavi, S. M. A.; Hashemi, M.; Mahallati, M. N.; Farhoosh, R. Optimization of Fat Replacers and Sweetener Levels to Formulate Reduced-Calorie Pistachio Butter: A Response Surface Methodology. International Journal of Nuts and Related Sciences 2011, 2, 37–54. [Google Scholar]

- Shakerardekani, A.; Karim, R.; Ghazali, H.M.; Chin, N.L. The Effect of Monoglyceride Addition on the Rheological Properties of Pistachio Spread. J Americ Oil Chem Soc 2013, 90, 1517–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fidaleo, M.; Miele, N.A.; Mainardi, S.; Armini, V.; Nardi, R.; Cavella, S. Effect of Refining Degree on Particle Size, Sensory and Rheological Characteristics of Anhydrous Paste for Ice Creams Produced in Industrial Stirred Ball Mill. LWT - Food Science and Technology 2017, 79, 242–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emadzadeh, B.; Razavi, S.M.A.; Mahallati, M.N. Effects of Fat Replacers and Sweeteners on the Time-Dependent Rheological Characteristics and Emulsion Stability of Low-Calorie Pistachio Butter: A Response Surface Methodology. Food Bioprocess Technol 2012, 5, 1581–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emadzadeh, B.; Razavi, S.M.A.; Rezvani, E.; Schleining, G. Steady Shear Rheological Behavior and Thixotropy of Low-Calorie Pistachio Butter. International Journal of Food Properties 2015, 18, 137–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, M.A. Rheology of Fluid, Semisolid, and Solid Foods: Principles and Applications; Food Engineering Series; Springer US: Boston, MA, 2014; ISBN 978-1-4614-9229-0. [Google Scholar]

- Razavi, S.M.A.; Taghizadeh, M.; Shaker Ardekani, A. Modeling the Time-Dependent Rheological Properties of Pistachio Butter. Journal of Nuts 2010, 01. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubost, N.J.; Shewfelt, R.L.; Eitenmiller, R.R. Consumer Acceptabılıty, Sensory and Instrumental Analysıs Of Peanut Soy Spreads. Journal of Food Quality 2003, 26, 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emadzadeh, B.; Razavi, S.M.A.; Schleining, G. Dynamic Rheological and Textural Characteristics of Low-Calorie Pistachio Butter. International Journal of Food Properties 2013, 16, 512–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabadán, A.; Gallardo-Guerrero, L.; Gandul-Rojas, B.; Álvarez-Ortí, M.; Pardo, J.E. Effect of Roasting Conditions on Pigment Composition and Some Quality Parameters of Pistachio Oil. Food Chemistry 2018, 264, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakerardekani, A.; Karim, R.; Ghazali, H.M.; Chin, N.L. Oxidative Stability of Pistachio (Pistacia Vera L.) Paste and Spreads. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2015, 92, 1015–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousazadeh, M.; Mousavi, M.; Emam-Djomeh, Z.; Ali Ahmed, S.; Hadinezhad, M.; Hassanzadeh, H. Sensorial, Textural, and Rheological Analysis of Novel Pistachio-based Chocolate Formulations by Quantitative Descriptive Analysis. Food Science & Nutrition 2023, 11, 7120–7129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guinard, J.-X.; Mazzucchelli, R. The Sensory Perception of Texture and Mouthfeel. Trends in Food Science & Technology 1996, 7, 213–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, M.; Freitas, F.; Torres, C.A.V.; Reis, M.A.M.; Alves, V.D. Influence of Temperature on the Rheological Behavior of a New Fucose-Containing Bacterial Exopolysaccharide. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2011, 48, 695–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasouli Pirouzian, H.; Alakas, E.; Cayir, M.; Yakisik, E.; Toker, O.S.; Kaya, Ş.; Tanyeri, O. Buttermilk as Milk Powder and Whey Substitute in Compound Milk Chocolate: Comparative Study and Optimisation. Int J of Dairy Tech 2021, 74, 246–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marra, F.; Lavorgna, A.; Incarnato, L.; Malvano, F.; Albanese, D. Optimization of Hazelnut Spread Based on Total or Partial Substitution of Palm Oil. Foods 2023, 12, 3122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manzocco, L.; Calligaris, S.; Camerin, M.; Pizzale, L.; Nicoli, M.C. Prediction of Firmness and Physical Stability of Low-Fat Chocolate Spreads. Journal of Food Engineering 2014, 126, 120–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Ingredients (%, w/w) | |||

| Formulation | Pistachio paste (SP) | Milk fat | Icing sugar |

| F1 | 96 | 4 | - |

| F2 | 93 | 7 | - |

| F3 | 90 | 10 | - |

| S1 | 76 | - | 24 |

| S2 | 73 | - | 27 |

| S3 | 70 | - | 30 |

| FS1 | 66 | 4 | 30 |

| FS2 | 66 | 7 | 27 |

| FS3 | 66 | 10 | 24 |

| Attribute | Definition of the Attribute | Evaluation of the attribute |

| Color | Evaluate the color of the product. | Look at the sample and evaluate the color of the sample |

| Flavor | Evaluate freshness, intensity, and the overall intensity of flavor perceived | Smell and taste the sample to assess the aroma strength, freshness, and characteristic pistachio flavor. |

| Adhesiveness to the spoon |

The property of the sample to stick to a surface | Insert a spoon into the sample and lift it slowly to measure stickiness. |

| Spreadability | Property of the sample to be spread over a surface | Using a spoon, spread the sample onto bread and evaluate its spreadability. |

| Flowability | Ability of the sample to flow or deform under its own weight | Place the spoon in the container and swirl several times to assess fluidity. |

| Firmness | Resistance of the sample to deformation under applied pressure | Place the sample in the mouth and evaluate the maximum force required to compress it. |

| Adhesiveness to the mouth |

The degree to which the sample sticks to oral surfaces, such as the palate or tongue | Press the sample against the palate with the tongue and evaluate the adhesiveness. |

| Oily | Perception of oil content and greasy mouth feel. | Place the sample in the mouth, swallow, and evaluate the perceived oiliness |

| Taste | Overall gustatory perception, including sweetness, balance, and aftertaste | Eat the sample and evaluate taste, balance, and aftertaste. |

| Overall Acceptability | Overall acceptability is a collective score indicating judges’ preferences based on sensory attributes | Evaluate the sample as a whole, taking into account all its attributes. |

| Sample | D10 (µm) | D50(µm) | D90 (µm) |

| LP | 5.72±0.06c | 16.71±0.12c | 434.80±9.30c |

| MP | 2.02±0.04b | 11.89±0.08b | 395.40±7.90b |

| SP | 1.88±0.03a | 7.18±0.07a | 149.78±4.60a |

| Sample | L* | a* | b* |

| LP | 44.34±0.02a | -3.82±0.05a | 45.86±0.05g |

| MP | 44.41±0.02b | -3.77±0.03ab | 44.91±0.06e |

| SP | 44.42±0.03b | -3.64±0.04cde | 44.55±0.05c |

| F1 | 44.76±0.02c | -3.53±0.07f | 44.21±0.06a |

| F2 | 44.91±0.04d | -3.56±0.08ef | 44.37±0.11b |

| F3 | 45.25±0.03e | -3.72±0.06bc | 44.77±0.09d |

| S1 | 46.79±0.02f | -3.57±0.03ef | 44.19±0.12a |

| S2 | 47.23±0.03g | -3.66±0.06cd | 44.28±0.09ab |

| S3 | 47.40±0.03h | 3.42±0.04g | 44.72±0.08d |

| FS1 | 48.11±0.03j | -3.61±0.02def | 44.73±0.03d |

| FS2 | 48.28±0.03k | -3.56±0.03ef | 44.64±0.05cd |

| FS3 | 48.02±0.04i | -3.59±0.02def | 45.10±0.06f |

| Sample | Temperature (ᵒC) |

τₒ (Pa) |

K |

n |

| F1 | 20 25 30 35 40 45 |

12.71±0.69b 12.57±0.20b 11.45±0.26a 11.25±0.21a 11.47±0.10a 11.52±0.20a |

6.05±0.01f 4.46±0.07e 3.65±0.06d 2.98±0.06c 2.45±0.02b 2.22±0.02a |

0.868±0.001b 0.884±0.004d 0.880±0.004cd 0.879±0.003c 0.878±0.002c 0.858±0.001a |

| F2 | 20 25 30 35 40 45 |

9.73±0.05c 9.06±0.20b 8.75±0.07b 8.92±0.40b 8.19±0.03a 8.24±0.05a |

4.76±0.05f 3.19±0.01e 2.46±0.03d 2.00±0.06c 1.86±0.01b 1.59±0.09a |

0.871±0.003b 0.893±0.001c 0.901±0.002d 0.900±0.006d 0.872±0.001b 0.852±0.005a |

| F3 | 20 25 30 35 40 45 |

10.51±0.16d 8.10±0.14c 6.41±0.02b 6.11±0.07a 6.11±0.02a 6.05±0.02a |

6.88±0.22e 2.73±0.11d 1.94±0.01c 1.69±0.02b 1.47±0.01a 1.33±0.02a |

0.801±0.007a 0.897±0.008e 0.896±0.002e 0.880±0.002d 0.867±0.002c 0.849±0.002b |

| Sample | Temperature (ᵒC) |

τₒ (Pa) |

K |

n |

| LP | 20 25 30 35 40 45 |

19.80±0.93a 20.64±0.56a 20.28±0.26a 20.40±0.11a 20.52±0.65a 21.03±0.57a |

15.70±0.70e 11.28±0.66d 9.28±0.10c 7.42±0.10b 6.50±0.27a 5.38±0.21a |

0.770±0.02a 0.809±0.06a 0.803±0.01a 0.812±0.01a 0.797±0.01a 0.783±0.01a |

| MP | 20 25 30 35 40 45 |

19.64±0.56c 18.07±0.83ab 17.35±0.40a 17.26±0.41a 17.39±0.10a 18.37±0.29b |

11.47±0.20f 8.91±0.29e 6.95±0.10d 5.65±0.10c 4.80±0.10b 4.14±0.15a |

0.823±0.01ab 0.825±0.01ab 0.835±0.01b 0.835±0.01b 0.828±0.01ab 0.820±0.01a |

| SP | 20 25 30 35 40 45 |

19.62±0.71b 17.13±0.82a 16.56±0.85a 16.25±0.68a 16.48±0.23a 17.48±0.12a |

9.76±0.64f 7.94±0.25e 6.18±0.13d 5.10±0.14c 4.20±0.10b 3.53±0.01a |

0.848±0.04a 0.837±0.01a 0.847±0.01a 0.844±0.01a 0.846±0.01a 0.844±0.01a |

| Sample | Temperature (ᵒC) |

τₒ (Pa) |

K |

n |

| S1 | 20 25 30 35 40 45 |

nd nd 26.94±0.86bc 25.22±0.05a 26.04±0.33ab 27.46±0.52c |

nd nd 17.28±0.73d 15.43±0.04c 13.90±0.25b 13.03±0.27a |

nd nd 0.710±0.015d 0.693±0.001c 0.674±0.003b 0.642±0.010a |

| S2 | 20 25 30 35 40 45 |

nd nd 28.48±0.20a 27.60±0.39a 27.70±0.30a 29.80±0.84b |

nd nd 20.01±0.50d 17.54±0.21c 15.88±0.29b 14.62±0.52a |

nd nd 0.689±0.014c 0.675±0.010bc 0.662±0.010ab 0.648±0.011a |

| S3 | 20 25 30 35 40 45 |

nd nd nd 24.20±0.33a 24.96±0.37a 27.82±0.82b |

nd nd nd 25.16±0.62c 22.58±0.35b 19.96±0.76a |

nd nd nd 0.581±0.010a 0.572±0.010a 0.581±0.019a |

| Sample | Temperature (ᵒC) |

τₒ (Pa) |

K |

n |

| FS1 | 20 25 30 35 40 45 |

16.48±0.03a 18.98±0.02b 19.17±0.38bc 19.68±0.16cd 19.82±0.11d 20.47±0.54e |

19.01±0.21f 12.96±0.20e 10.18±0.21d 8.37±0.17c 7.61±0.07b 7.20±0.32a |

0.692±0.004a 0.751±0.005cd 0.759±0.007d 0.763±0.006d 0.740±0.002c 0.715±0.011b |

| FS2 | 20 25 30 35 40 45 |

14.45±0.39b 14.20±0.10ab 13.91±0.13a 14.60±0.26bc 14.90±0.23cd 15.07±0.20d |

9.12±0.46e 7.06±0.05e 5.06±0.10d 4.02±0.05c 3.39±0.06b 3.16±0.04a |

0.811±0.012a 0.823±0.002a 0.838±0.009b 0.848±0.003b 0.845±0.004b 0.823±0.003a |

| FS3 | 20 25 30 35 40 45 |

16.78±0.41b 13.40±0.14b 9.52±0.20a 9.39±0.02a 9.30±0.02a 9.38±0.02a |

15.22±0.19f 6.16±0.05e 2.97±0.04d 2.48±0.02c 2.19±0.01b 2.03±0.04a |

0.716±0.007a 0.814±0.002b 0.879±0.020e 0.872±0.002e 0.858±0.002d 0.836±0.005c |

| Sample | Ea | ko | r2 | ||

| LP | 32.1 | 2.8*10-5 | 0.9866 | ||

| MP | 31.8 | 2.4*10-5 | 0.9926 | ||

| SP | 31.8 | 2.1*10-5 | 0.9986 | ||

| F1 | 27.5 | 6.4*10-5 | 0.9860 | ||

| F2 | 22.2 | 3.6*10-4 | 0.9714 | ||

| F3 | 20.4 | 5.9*10-4 | 0.9963 | ||

| S1 | 15.3 | 4.0*10-2 | 0.9891 | ||

| S2 | 18.4 | 2.6*10-2 | 0.9916 | ||

| S3 | 18.9 | 1.6*10-2 | 0.9978 | ||

| FS1 | 18.2 | 7.0*10-3 | 0.9336 | ||

| FS2 | 25.4 | 2.0*10-4 | 0.9569 | ||

| FS3 | 20.3 | 9.0*10-4 | 0.9720 | ||

| Samples | Firmness (N) | Spreadability (N s) | Adhesiveness (N s) |

| LP MP SP F1 F2 F3 S1 S2 S3 FS1 FS2 FS3 |

2.69±0.04f 2.68±0.04f 2.36±0.03e 1.79±0.02d 1.35±0.02b 1.02±0.02a 5.05±0.06h 5.10±0.06h 5.33±0.05i 3.66±0.04g 2.39±0.03e 1.65±0.03c |

1.589±0.021f 1.568±0.019f 1.432±0.018e 1.064±0.017d 0.830±0.015b 0.630±0.012a 2.995±0.032h 3.014±0.041h 3.192±0.040i 2.143±0.028g 1.426±0.017e 0.970±0.016c |

-0.667±0.012g -0.631±0.011f -0.538±0.009e -0.401±0.008d -0.296±0.004b -0.224±0.004a -1.272±0.012j -1.212±0.011i -1.300±0.014k -0.796±0.010h -0.544±0.008e -0.352±0.004c |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).