1. Introduction

Mathematics education plays a crucial role in developing analytical thinking, logical reasoning, and problem-solving skills that serve as the foundation for students’ success in various disciplines. However, in Indonesia, concerns about the effectiveness and quality of mathematics instruction have been growing in recent years. Despite numerous curriculum reforms and investments in teacher training, many students continue to struggle with mathematical concepts, particularly in problem-solving and higher-order thinking. Several studies attribute this issue not only to the difficulty of the subject but also to the inadequate preparation of teachers in both mathematical content and pedagogy. As future educators, preservice teachers are expected to possess a solid understanding of mathematical knowledge for teaching, as it directly influences the learning outcomes of their future students. The examination of preservice teachers’ readiness, therefore, becomes essential in identifying gaps in teacher education programs and ensuring the production of competent mathematics educators at the elementary level.

Moreover, teacher knowledge has long been recognized as a significant factor in determining the quality of mathematics education. The framework of Mathematical Knowledge for Teaching (MKT) emphasizes the integration of content knowledge and pedagogical understanding necessary for effective instruction. Yet, in Indonesia, there remains limited empirical evidence on how well preservice teachers acquire and apply this specialized knowledge during their preparation. Addressing this gap is critical, as inadequate mastery of mathematical concepts and pedagogical approaches may lead to the perpetuation of misconceptions and poor instructional practices in classrooms. Thus, assessing the dimensions of MKT among preservice elementary teachers provides valuable insight into the current state of teacher preparation and highlights the areas needing improvement to meet both national and international education standards.

Mathematics education is fundamental in shaping students’ analytical reasoning, logical thinking, and problem-solving abilities—competencies essential for lifelong learning and national development. Yet in Indonesia, persistent concerns remain about the overall quality of mathematics instruction. Despite curricular reforms and initiatives to improve teacher education, students’ performance in mathematics continues to lag behind regional and international standards. A key factor contributing to this situation is the insufficient mastery of both content and pedagogy among preservice and in-service teachers. Effective teaching requires more than procedural fluency; it demands a deep conceptual understanding of mathematical ideas and the ability to connect them with appropriate instructional strategies. Therefore, assessing how well preservice teachers are prepared in these areas is crucial to strengthening the mathematics education system and improving student outcomes at the elementary level.

Teacher competence has consistently been identified as one of the strongest predictors of student achievement. Within this context, the concept of Mathematical Knowledge for Teaching (MKT) provides a comprehensive framework for understanding the specialized knowledge teachers need to teach mathematics effectively. However, in Indonesia, empirical studies exploring the extent to which preservice teachers possess this knowledge are still limited. Many teacher education programs tend to emphasize theoretical coursework without adequately integrating practical experiences that develop pedagogical content knowledge. This imbalance may result in teachers who know mathematics but struggle to translate that knowledge into meaningful classroom instruction. Investigating the dimensions of MKT among preservice elementary teachers is therefore essential to reveal existing gaps and to inform policy reforms that align teacher education programs with both national curriculum goals and international standards.

The current state of mathematics education in the country both in the basic education and tertiary levels is very problematic as shown in the results of international and national examinations such as the Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS), Teacher Education and Development Study: Learning to Teach Mathematics (TEDS-M, and the Indonesia National Achievement Test (NAT). TIMMS (2023) reveal that grade four pupils and second-year high school students got overall achievement rates of 358 and 378 in Mathematics, respectively. These overall achievement rates fall below the international benchmark of 400 set by TIMMS. Similarly, in the TIMMS - Advanced (2022) which was participated in by students taking special science curriculum, the Indonesias ranked last, with an average scale score of 355 out of ten participating countries. The overall average percent correct in the advanced mathematics content areas and cognitive domains obtained by Filipino students is 24, also the lowest among the ten countries who participated in the assessment. In general, out of the 4.901 students who took the test, only 1% of the students reached the advanced benchmark, 4% reached the high benchmark and 13% to the intermediate benchmark (Ogena, et al. 2020). It worth mentioning that the performance of students coming from the Indonesia Science High School system in terms of overall average percent correct in the content areas in Algebra, Calculus and Geometry and knowing, applying and reasoning domains is comparable to the performance of students from the three top performing countries, the Russian Federation, the Netherlands and Lebanon. Likewise, initial results from Teacher Education and Development Study: Learning to Teach Mathematics (TEDS-M, 2022), show that the overall mean performance of Filipino pre- service primary teachers on mathematical content knowledge and pedagogical content knowledge were 440 and 457, respectively. These results are also way below the highest scoring countries, Taiwan and Singapore, which posted an overall mean achievement of 623 and 593, respectively. The National Achievement Test (NAT) results in mathematics for SY 2024-2025 show a mean percentage score (MPS) of 66.79% and 46.37% for grade six and fourth-year high school examinees respectively. These results are behind the target of 75% MPS set in the 2024 Indonesia Development Plan especially for the fourth-year examinees.

Research findings show that the inadequacy of teachers' knowledge of mathematics and how they teach it is one of the major reasons why students are not learning the mathematics they are supposed to learn in school (Mewborn, 2023; Ball, 2020; Ball, Hill & Bass, 2025; Hill, Rowan & Ball, 2019; Mapolelo & Akinsola, 2018). A report from the Teacher Professional Development: A Primer for Parents and Community Members (2022), states that quality teachers are the most significant determinant of student achievement. Ma (2019), in her book Knowing and Teaching Elementary Mathematics, stated that teachers of mathematics, especially those who teach at the elementary level, generally do not possess the knowledge necessary to help empower future generations of adults mathematically. She calls this as the "vicious cycle" formed by low-quality mathematics education and low- quality teacher knowledge of school mathematics" (p. 149). Moreover, in a Discussion Paper Series No. 2022-16 entitled “Measures for Assessing Basic Education in the Indonesias,” Maligalig and Albert stressed that the low achievement rates for both elementary and secondary schools in the Indonesias are indicative of the low quality of elementary and secondary education. They further argued that a contributing factor to the low quality is the lack of competent teachers who are the primary resource for elementary and secondary students instead of books and other learning materials.

Research consistently underscores that teachers’ inadequate understanding of mathematics and ineffective instructional practices are among the primary reasons students fail to achieve the expected learning outcomes in mathematics (Mewborn, 2023; Ball, 2020; Ball, Hill, & Bass, 2025; Hill, Rowan, & Ball, 2019; Mapolelo & Akinsola, 2018). When teachers themselves struggle with mathematical concepts or rely heavily on procedural teaching, students are less likely to develop conceptual understanding and critical thinking skills. This lack of depth in mathematical comprehension ultimately affects students’ performance in both national and international assessments.

According to the Teacher Professional Development: A Primer for Parents and Community Members (2022), teacher quality remains the single most significant determinant of student achievement. Regardless of socioeconomic or school-related factors, the effectiveness of teaching largely depends on the teacher’s mastery of content knowledge and the ability to translate it into meaningful learning experiences. This implies that investment in teacher education and continuous professional development is central to improving the overall quality of mathematics education.

Ma (2019), in her influential work Knowing and Teaching Elementary Mathematics, emphasizes that elementary mathematics teachers often lack the depth of understanding required to effectively teach mathematical concepts to young learners. She describes this phenomenon as a “vicious cycle,” wherein low-quality mathematics instruction perpetuates low levels of teacher knowledge across generations. This cycle continues unless deliberate and systematic interventions are made to strengthen teachers’ content and pedagogical competencies.

The “vicious cycle” described by Ma highlights a deeper structural issue within teacher education programs. Many preservice teachers enter the profession with weak foundations in mathematics, and teacher training institutions often fail to address these deficiencies. As a result, graduates enter the classroom insufficiently equipped to design lessons that foster reasoning, problem-solving, and conceptual understanding. This situation is particularly concerning in Indonesia, where curriculum demands have become more complex while teacher preparation remains uneven.

Furthermore, the Discussion Paper Series No. 2022-16: Measures for Assessing Basic Education in Indonesia by Maligalig and Albert reveals that low achievement rates at both the elementary and secondary levels reflect the broader issue of educational quality. The authors argue that the lack of competent teachers is a central contributing factor to this problem. In many cases, teachers become the primary learning resource for students, especially in schools where access to textbooks and technology is limited. Hence, their competence directly determines students’ exposure to and mastery of mathematical ideas.

The reliance on teachers as the main instructional resource in many Indonesian classrooms places even greater emphasis on their professional competence. Without sufficient content mastery and pedagogical flexibility, teachers may struggle to adapt instruction to diverse learner needs. This situation leads to rote learning, limited problem-solving engagement, and a lack of deeper mathematical reasoning among students. The issue underscores the urgent need for systemic reform in teacher education, focusing on enhancing both theoretical and applied dimensions of mathematical knowledge for teaching.

In light of these findings, it becomes evident that improving the quality of mathematics education in Indonesia requires a dual approach—strengthening preservice teacher preparation and ensuring sustained professional development for in-service teachers. Universities and teacher training institutions must integrate rigorous mathematical content with pedagogical innovation, supported by mentoring and reflective teaching practices. By doing so, Indonesia can begin to break the “vicious cycle” of weak mathematical instruction and create a generation of teachers capable of fostering mathematical literacy, creativity, and problem-solving competence among future learners.

What types of mathematical knowledge should teachers have to be able to teach the subject proficiently and efficiently is a fundamental question that is currently being explored by researchers and mathematics educators worldwide. Traditionally, it is assumed that to teach successfully, teachers need to have a firm knowledge base of the mathematics content they teach be it in the elementary, secondary or tertiary level. Such content knowledge is gained through the formal study of the different content subjects pre-service teachers take to complete the academic requirements prescribed in the teacher education curriculum. This knowledge can be acquired through reading textbooks, taking notes, observing teachers’ demonstrations, listening to teachers’ explanations, and completing practice problems (Walters, 2009). However, teachers do not only need subject matter knowledge to be able to teach the subject effectively. They also need another kind of knowledge that will enable them to provide students with explanations as to why a procedure works, to analyze and correct student errors and misconceptions and to use appropriate examples for representing mathematical concepts, etc. Such knowledge is what Shulman (1986) calls as pedagogical content knowledge. Ma (2019) describes this knowledge as the flexibility in grasping multiple perspectives and understanding the connection of ideas. She further stresses that it is essential that teachers should have a profound understanding of fundamental mathematics (PUFM) to be able to teach it. Hill et al., (2025) call this knowledge, mathematical knowledge for teaching mathematics (MKT).

The question of what mathematical knowledge teachers need to teach effectively transcends mere curriculum design—it strikes at the heart of pedagogical professionalism and student learning outcomes. Historically, teacher preparation systems worldwide operated under the assumption that mastery of advanced mathematical content—acquired through university-level courses in calculus, algebra, or analysis—was sufficient to ensure teaching competence. This belief, rooted in a transmission model of education, presumed that knowledge flows unidirectionally from expert to novice, with the teacher’s role limited to accurate delivery. However, decades of classroom research have dismantled this notion, revealing that effective mathematics teaching demands far more than disciplinary expertise. Teachers must navigate the complex terrain between abstract mathematical truth and the developmental realities of young learners, a task that requires specialized forms of knowledge not typically cultivated in standard mathematics departments. This realization has catalyzed a paradigm shift in teacher education, moving from a focus on what teachers know to how they use that knowledge in practice. The work of Lee Shulman (1986) was pivotal in this transformation, as he identified pedagogical content knowledge (PCK) as the “signature pedagogy” of teaching—a unique blend of subject matter and pedagogy that distinguishes expert teachers from subject-matter experts. Consequently, contemporary frameworks now treat teaching not as applied scholarship, but as a distinct profession with its own knowledge base. This reconceptualization has profound implications for how we design teacher preparation programs, assess teacher readiness, and support professional growth. Without this shift, efforts to improve mathematics education will continue to founder on the gap between content knowledge and classroom practice.

Shulman’s (1986) introduction of pedagogical content knowledge (PCK) marked a watershed moment in educational theory, challenging the binary separation of “content” and “method” that had long dominated teacher education. PCK, he argued, is not simply the sum of subject matter knowledge and general pedagogical knowledge, but a transformative synthesis that enables teachers to represent ideas in ways that make them comprehensible, anticipate student difficulties, and adapt instruction to diverse learners. For example, knowing that a ÷ b = a × 1/b is a matter of subject knowledge; knowing how to use a pizza-sharing scenario to help a Grade 5 student grasp why this works—and why it fails when applied to subtraction—is PCK. This distinction is critical because it explains why mathematicians, despite deep content expertise, often struggle to teach elementary concepts effectively. PCK is inherently contextual, practical, and student-centered; it emerges from repeated engagement with the act of teaching, not from passive study. In mathematics, where concepts are tightly interconnected and misconceptions can cascade, PCK becomes indispensable for diagnosing errors and scaffolding understanding. Unfortunately, many teacher education programs still treat PCK as an afterthought, relegating it to generic “methods” courses that lack mathematical specificity. To cultivate PCK, PSTs need sustained opportunities to analyze student work, design representations, and reflect on instructional decisions—all grounded in real mathematical content. Without such experiences, PCK remains underdeveloped, regardless of how strong a teacher’s SMK may be.

Liping Ma’s (2019) concept of Profound Understanding of Fundamental Mathematics (PUFM) further deepened the discourse by shifting attention from advanced topics to the depth of understanding in elementary mathematics. Ma’s comparative study of Chinese and U.S. teachers revealed that effective elementary teachers possess not just procedural fluency, but a coherent, interconnected grasp of foundational concepts—such as place value, fractions, and operations—that allows them to explain ideas from multiple perspectives, justify procedures, and connect topics across the curriculum. PUFM is characterized by four key qualities: basic ideas (understanding core principles), connectedness (seeing relationships between concepts), multiple perspectives (solving problems in varied ways), and longitudinal coherence (knowing how ideas develop over time). Crucially, Ma demonstrated that PUFM is not about knowing more mathematics, but about knowing elementary mathematics more deeply—a distinction often lost in systems that prioritize calculus over number sense. In Indonesia, where PSTs take 18 credit units of advanced mathematics largely irrelevant to primary teaching, this insight is particularly urgent. A teacher who can solve differential equations but cannot explain why 1/2 ÷ 1/4 = 2 lacks the very knowledge that matters most in the classroom. PUFM thus reframes the goal of teacher education: not to produce amateur mathematicians, but to develop expert teachers of fundamental mathematics. This requires curricula that prioritize depth over breadth and coherence over coverage.

Building on Shulman and Ma, Ball, Thames, and Phelps (2024) operationalized these ideas into the Mathematical Knowledge for Teaching (MKT) framework—a comprehensive, empirically grounded model that has become the gold standard in mathematics education research. MKT distinguishes between Common Content Knowledge (CCK)—mathematical knowledge used in everyday life or other professions—and Specialized Content Knowledge (SCK)—knowledge unique to teaching, such as choosing examples, evaluating student strategies, or explaining why a procedure works. It also includes two pedagogical domains: Knowledge of Content and Students (KCS)—understanding how students think about and learn specific concepts—and Knowledge of Content and Teaching (KCT)—knowing how to sequence tasks, select representations, and manage discourse. This granular taxonomy allows researchers to diagnose precisely where PSTs struggle, as seen in studies where PSTs perform adequately on CCK items but falter on SCK or KCT tasks. The MKT framework has been validated across diverse cultural contexts, confirming that the specialized knowledge of teaching is universal, even if its manifestations vary. In Indonesia, applying MKT reveals that PSTs may solve fraction problems correctly (CCK) but cannot design a word problem for division of fractions (KCT)—a gap with direct consequences for student learning. By making the invisible work of teaching visible, MKT provides a roadmap for targeted curriculum reform and professional development.

The evolution from SMK to MKT reflects a broader epistemological shift in how we understand professional knowledge. Teaching is no longer seen as the application of theoretical knowledge to practice, but as a site of knowledge generation in its own right. This “practice-based” view recognizes that the knowledge needed to teach fractions effectively is not found in mathematics textbooks or pedagogy manuals alone, but in the dynamic interplay between content, students, tasks, and classroom context. Consequently, teacher education must move beyond the “two-course model” (content courses + methods courses) toward integrated experiences where PSTs learn mathematics through the lens of teaching. For instance, a lesson on prime numbers should not only prove the infinitude of primes but also explore how to introduce the concept using arrays, factor trees, or culturally relevant patterns (e.g., Mandailing weaving motifs). Such integration transforms abstract knowledge into usable knowledge—knowledge that can be enacted in real classrooms with real students. Without it, PSTs graduate with fragmented repertoires: they may know mathematics, but not how to make it learnable. This is especially critical in Indonesia, where Kurikulum Merdeka emphasizes student-centered, conceptual learning, yet PSTs report feeling unprepared to implement it. The MKT framework thus offers not just a diagnostic tool, but a design principle for 21st-century teacher education.

Empirical studies consistently show that teachers’ MKT is a strong predictor of student achievement in mathematics, even after controlling for socioeconomic factors. Hill, Rowan, and Ball (2005) found that a one-standard-deviation increase in teachers’ MKT was associated with a 2–3 month gain in student learning—a finding replicated across multiple countries. This impact occurs because MKT enables teachers to do the “invisible work” of teaching: noticing subtle errors, asking probing questions, and adapting instruction in real time. For example, a teacher with strong KCS might recognize that a student’s error in comparing fractions stems from overgeneralizing whole-number logic, and respond with a targeted visual model rather than re-teaching the algorithm. In contrast, a teacher with only SMK might mark the answer wrong and move on, missing a critical learning opportunity. The moderate correlation (r = 0.307) between SMK and PCK found in Indonesian PSTs underscores that this expertise does not emerge automatically—it must be deliberately cultivated. This has direct policy implications: if student learning is the goal, then investing in teachers’ MKT is not a luxury, but a necessity. Professional development, certification standards, and university curricula must all prioritize MKT as a core outcome.

In the Indonesian context, the gap between SMK and MKT is exacerbated by structural features of teacher education. PSTs complete 18 credit units of advanced mathematics (e.g., calculus, linear algebra) that bear little resemblance to the Grade 1–6 curriculum, alongside 54 units of professional education that often lack mathematical specificity. As a result, they graduate with “high-level” knowledge that cannot be “lowered” to the elementary level—a phenomenon Ball et al. (2024) call “unusable knowledge.” Moreover, only one of the 18 mathematics courses directly addresses elementary content, and none explicitly develop SCK, KCS, or KCT. This curricular misalignment explains why PSTs struggle with items like “choosing an appropriate example for dividing fractions” (answered correctly by only 6% in one study). The problem is not lack of intelligence or effort, but lack of opportunity to learn the right kind of knowledge. Reforming this system requires more than adding a “methods” course; it demands a fundamental rethinking of what counts as essential knowledge for elementary teachers. Universities must collaborate with schools to co-design courses that use real classroom artifacts—student work, lesson videos, curriculum materials—as the basis for learning. Only then can PSTs develop the MKT needed to implement Kurikulum Merdeka effectively.

Digital technologies and AI-enhanced tools offer promising avenues for bridging the SMK–MKT gap, particularly in resource-constrained settings like rural Indonesia. Platforms such as GeoGebra, when integrated into a Project-Based Learning (PjBL) model, allow PSTs to experiment with dynamic representations of mathematical concepts—visualizing fraction division, exploring prime factorization, or modeling proportional reasoning in real time. These tools can simulate classroom scenarios, enabling PSTs to test different examples, observe virtual student responses, and reflect on pedagogical choices without real-world consequences. Moreover, AI-driven feedback systems can provide personalized guidance on PCK development, such as suggesting alternative representations or flagging potential misconceptions in a PST’s explanation. In community initiatives like “Generasi Mandailing Natal Bersinar,” such technologies can democratize access to high-quality MKT development, even where expert mentors are scarce. However, technology alone is insufficient; it must be embedded in a pedagogical framework that emphasizes reflection, collaboration, and connection to local contexts. When used thoughtfully, digital tools can transform teacher education from passive knowledge transmission to active knowledge construction.

Cultural and linguistic factors further complicate the development of MKT in multilingual societies like Indonesia. Many PSTs in regions such as Mandailing Natal must translate mathematical concepts into local languages that may lack precise terms for ideas like “fraction” or “prime number.” This requires not just linguistic skill, but deep conceptual understanding to construct analogies that resonate with students’ lived experiences—such as using rice portions, cloth weaving, or traditional games to illustrate mathematical relationships. A PST with strong SMK but weak cultural fluency may choose examples that confuse rather than clarify, while one with strong MKT can bridge this gap. This dimension of teaching—often overlooked in Western frameworks—is essential for equitable mathematics education in diverse classrooms. Teacher education programs must therefore incorporate ethnomathematics and culturally responsive pedagogy into MKT development, helping PSTs see local knowledge systems as resources, not obstacles. By validating students’ cultural identities while building mathematical understanding, teachers can foster both engagement and achievement. This approach aligns with global calls for decolonizing mathematics education and centering local epistemologies.

The question of what mathematical knowledge teachers need has evolved from a narrow focus on content mastery to a rich, multidimensional understanding centered on Mathematical Knowledge for Teaching (MKT). Effective teaching requires not just knowing mathematics, but knowing how to unpack it, represent it, connect it, and make it accessible to diverse learners. This specialized knowledge—encompassing SCK, KCS, and KCT—is not acquired incidentally but must be deliberately cultivated through integrated, practice-based teacher education. In Indonesia and similar contexts, closing the MKT gap demands systemic reform: revising curricula to prioritize elementary mathematics, redesigning assessments to value pedagogical reasoning, and leveraging technology and community partnerships to support learning. The ultimate goal is not to produce teachers who can solve advanced problems, but those who can nurture mathematical thinking in every child—regardless of background, language, or prior achievement. As global education systems increasingly emphasize critical thinking and problem-solving, the need for MKT-proficient teachers has never been greater. Investing in this knowledge is not merely an educational imperative; it is a social and economic necessity for building equitable, innovative societies.

Recent developments in the field of teaching and learning mathematics saw the emergence and conceptualization of a framework for teaching mathematics called mathematical knowledge for teaching (MKT). Thames, et al. (2019) define MKT as the “mathematical knowledge needed to perform the recurrent tasks of teaching mathematics to students.” Currently the MKT framework is categorized into two major categories, namely; subject matter content knowledge and pedagogical content knowledge. Under the subject matter knowledge domain are common content knowledge (CCK) - the mathematical knowledge and skill used in settings other than teaching and specialized content knowledge (SCK) - the knowledge and expertise unique to teaching. Pedagogical content knowledge (PCK) includes knowledge of content and students (KCS) which is the knowledge that combines knowing about students and knowing about mathematics and knowledge of content and teaching (KCT) which combines knowing about teaching and knowing about mathematics (Ball et al., 2017).

With the emergence of a new conception of the content knowledge that teachers need to know to be able to teach mathematics comes the problem on how this knowledge will be measured. Previous researches on teachers’ knowledge show that teachers’ effectiveness was evaluated through proxy variables such as educational qualification, certification status, number of mathematics and methods courses taken in college, years of teaching experience and number of trainings attended, self-report of what they do in their classrooms, principal and students’ evaluations, classroom observation reports, analyses of videotaped lesson and giving examination on content to both teacher and student, etc. However, according to Ball et al. (2019), most of these types of assessment do not capture the mathematical knowledge and reasoning needed to perform the task of teaching. In the Indonesias, researchers still use proxy variables in assessing mathematical knowledge for teaching. For instance, Sogillo et al. (2024) evaluated the quality of mathematics teachers in a public school and a private school, measured teacher quality by asking the teachers themselves the frequency of practicing in their classes the teaching methods/approaches outlined in a 50-item questionnaire. Agsaluad, (2017) also measured teacher quality by asking students to rate their teachers using the NBC No. 461 teaching effectiveness instrument. Both studies concluded that their respondents are highly effective teachers. However, conclusions derived from self-report and students’ perceptions seem not to be valid because the instruments used did not capture the work of teaching as describe by Ball and colleagues.

After a thorough review of literature, Hill, et al. (2019) felt the need to map out differing views and conceptions held by teaching experts and researchers about mathematical knowledge for teaching and how it should be measured especially on large scale population. Guided by the questions, “What mathematical knowledge is needed to help students learn mathematics?” and “Can we construct reliable measures that accurately represent teachers’ ability in these areas?”, they developed a survey consisting of multiple-choice items intended to measure mathematical knowledge and skills needed for teaching elementary mathematics. Exploratory factor analyses were conducted in order to find underlying dimensions represented by the items in the survey and item response theory (IRT) one-parameter model was employed to establish the reliabilities of the item. The authors reported that MKT is partly domain-specific, rather than just related to overall intelligence, mathematical or teaching ability. Content areas covered by the measure are numbers and operations, geometry, patterns and functions, and algebra. In 2022, sample items of the MKT measure were released.

Since its release, studies conducted using the MKT instrument, generally fall into adaptation and validation done in other countries for both in-service and pre-service teachers or as a material for professional development of teachers.

Using a mixed method design of data collection, Jóhannsdóttir (2023), investigated the level of elementary mathematical content knowledge for teaching of 38 pre-service teachers at the School of Education, University of Iceland. Adapted items from the MKT released item 2022 were used to collect data on the MKT levels of the participants. Interviews were also conducted to 10 respondents in order to elicit how they think during a problem solving activity and how they explain their solutions. Findings of the study indicated that prospective teachers’ common content knowledge was procedural. They can solve mathematical problems, however, they could not explain underlying reasons for their solutions. Item difficulty analysis using an item response theory model was used to identify which items were found easy or difficult by the participants. Common content knowledge items found most difficult by the prospective teachers are: identifying surjective function, statement about multiplication, properties of positive and negative numbers, multiplying fractions, algebra problem, needing a system of equations to solve problems. In terms of specialized content knowledge, difficult topics are: alternative method to divide fractions, explanation for equivalent fractions, division rules, visual model for multiplication, alternative subtraction method. In general, and in both knowledge domains, the source of difficulty among the pre-service teachers was on fractions.

Nolan et al., (2018) studied the development of MKT using a pre—and post-test method with two groups of pre-service teachers at two Irish universities. Two measurements were taken from the sample- the MKT level and MKT awareness. The MKT level was measured using a subset of the LMT released items on integers, fractions and basic geometry while level of MKT awareness was measured by asking the pre-service teachers to list down different teaching situations where a teacher uses his or her knowledge of mathematics. The intervention was the delivery of a specially designed mathematics pedagogy course intended to improve students’ MKT. After the intervention, the MKT level of the participant significantly increased. Fifty-five items that were incorrectly answered in the pre-test were already answered correctly in the post-test was also reported by the researchers.

A large scale study by Jakobsen, et al., (2018) evaluated whether the initial primary teacher education (IPTE) program of Malawi can develop pre-service teachers’ knowledge to teach mathematics in their primary schools. Participants were 1,700 students enrolled in the primary education program from 8 public teacher colleges in the country. A pre- and post-test design was employed to gauge the improvement of pre-service teachers’ MKT. Two forms of adapted MKT measure were administered as pre-test and post-test. A paired sample t-test show that the post-test scores were significantly higher than that of the post-test, indicating a positive impact of the IPTE program.

To establish whether a relationship exists between the mathematics courses of the Diploma in Basic Education (DBE) and mathematical knowledge for teaching, Asante and Mereku (2022) analyzed the performance of 100 randomly selected pre-service teachers enrolled in the Colleges of Education in Ghana using two data sets, mathematical knowledge for teaching (MKT) scores and DBE examination results. The MKT scores were measured through an adapted instrument from the MKT instrument developed by Ball, et al (2025) while DBE examination results were obtained from the previous records of respondents’ first year mathematics content examination. The overall performance of the pre-service teachers in the MKT test was low with only 8% of them obtained marks from 60% - 73% of the items while 75% of them got marks from 32% - 51%. In terms of content domains, the pre-service teachers performed better in number patterns than in fractions and number operation. Contrary to the researchers’ expectation, the pre-service teachers scored lowest on number operations. Result of the DBE examination indicated that only 10% of the respondents got scores of 77% and 50% of them did not score beyond 63%. A correlation coefficient between the DBE examination result and MKT score was computed, (ρ= .388 at α =.01 indicating a positive moderate correlation.

Considering the impact of mathematical content knowledge and pedagogical content knowledge on how mathematics teachers design their instructional environment, it is of paramount importance to explore the extent to which such knowledge is exhibited by pre-service teachers before exiting from their teacher education preparation program. Moreover, taking into consideration the current state of mathematics education in the country, it is imperative that this situation be addressed and one of the most logical ways is to improve the quality of teachers’ knowledge for teaching mathematics. Perhaps an appropriate starting point for improvement is an assessment of the mathematical knowledge in both content and pedagogy that pre-service teachers gain from their teacher preparation program.

Although this study also explored the mathematical knowledge for teaching of pre-service teachers, it is different from the studies previously reviewed because actual items from the MKT instrument released in 2022 did not from part of the instrument used to measure pre-service teachers’ knowledge for teaching. Instead a researcher-constructed following Hill, et al. (2019) conceptualizations of the four domains of MKT was used in the study.

3. Results and Discussions

Pre-Service Teachers’ Performance in the Mathematical Knowledge for Teaching Test

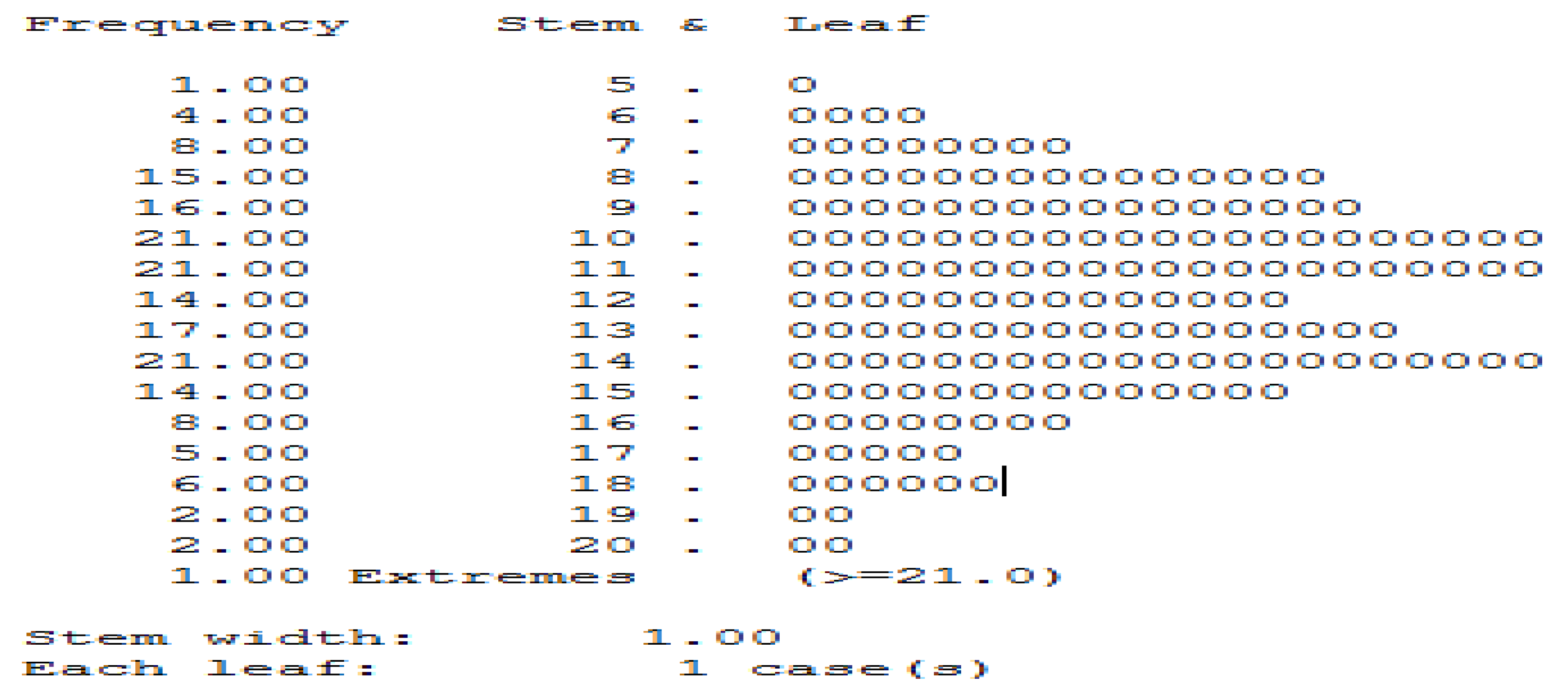

Figure 1 shows the stem and leaf plot of the PST’s scores in the MKT measure. Out of 35 items of the highest score is 21 and the lowest is 5 with a mean of 11.95 and a standard deviation of 3.28. The mean score of 11.95 shows a very big gap from the perfect score, and the bulk of the scores ranged from 8 to 15 which was obtained by 138 of around 80% of the student teachers. However, only 16 or 9% of them were able to answer correctly 50% or more of the items in the test. Ideally an examinee with an average ability is expected to answer 50 percent of the items in a test. Clearly, these results indicate that the PST’s performed very low on the MKT measure. This is consistent with Jóhannsdóttir (2023); Asante and Mereku (2022) findings that majority of preservice teachers have an inadequate understanding of the mathematics content knowledge necessary for teaching in the elementary grades. This low performance level could be explained by the lack congruence between the lessons taught in the content courses with the lessons they will teach in the future. Although they took 18 units of content courses and 54 units of professional education courses, only one course has a content parallel to the items in the MKT instrument. Not one among these courses addresses developing specialized content knowledge, knowledge of content and students and knowledge of content and teaching. Only one course of the 18 units of content courses deals with the content knowledge these pre-service teachers will teach in the future. This result further suggests that the kind of knowledge necessary for teaching mathematics as described by Shulman (1986); Ma (2019); Ball et al., (2025) is not addressed in the mathematics courses offered in the teacher education curriculum.

The pronounced discrepancy between the observed mean score (11.95 out of 21) and the theoretical midpoint of the test (10.5, representing 50% of items answered correctly) underscores a critical deficit in the mathematical knowledge for teaching (MKT) among the participating preservice teachers (PSTs). While a mean slightly above 10.5 might suggest moderate competence, the fact that only 9% of PSTs achieved this benchmark—and that the overwhelming majority clustered between scores of 8 and 15—reveals a systemic underperformance. This narrow concentration of scores below the expected proficiency threshold indicates not merely individual shortcomings but a structural misalignment in teacher preparation. Such findings echo global concerns about the “pedagogical content gap,” wherein future educators are equipped with abstract mathematical knowledge but lack the specialized understanding required to unpack, represent, and adapt that knowledge for diverse learners (Ball, Thames, & Phelps, 2024). The stem-and-leaf plot in

Figure 1 thus functions not only as a descriptive statistic but as a diagnostic signal of curricular inadequacy.

The significant discrepancy between the observed mean score (11.95 out of 21) and the theoretical midpoint (10.5) provides compelling evidence of a pervasive gap in mathematical knowledge for teaching (MKT) among Indonesian preservice teachers (PSTs). Although at first glance a mean score above the midpoint might imply moderate proficiency, the low proportion of participants—only 9%—who met or exceeded this benchmark paints a far more concerning picture. This distribution pattern suggests that most PSTs operate below the expected threshold of pedagogical-mathematical competence. The implication is not a matter of statistical fluctuation but rather a systemic indicator of insufficient preparation in translating mathematical knowledge into instructional practice. The finding aligns with previous research highlighting similar patterns in developing countries where mathematics teacher education emphasizes procedural fluency over conceptual depth.

The clustering of scores between 8 and 15 demonstrates that most PSTs possess partial but fragmented mathematical understanding. This limited range of performance suggests that while some foundational concepts are present, there remains a profound difficulty in integrating these ideas into coherent pedagogical reasoning. In mathematical cognition, such fragmented knowledge often manifests as “rule-bound reasoning,” where individuals rely on memorized algorithms without grasping the underlying conceptual structures. Consequently, PSTs may perform adequately on procedural tasks but falter when faced with items requiring explanation, representation, or adaptation of mathematical ideas for learners. This observation is consistent with the theoretical framework proposed by Hill, Ball, and Schilling (2008), which differentiates between common content knowledge (CCK) and specialized content knowledge (SCK)—the latter being the critical area of deficiency evident in this study.

The observed performance distribution also reflects deeper pedagogical issues within the structure of teacher education curricula in Indonesia. Traditional mathematics courses for PSTs tend to prioritize abstract algebraic and analytical content, often disconnected from the primary school context they are meant to teach. As a result, PSTs may master advanced symbolic manipulation yet struggle to explain elementary mathematical ideas in intuitive or developmentally appropriate ways. This curricular disjunction mirrors what Shulman (1986) described as the “missing paradigm” in teacher education—the failure to bridge disciplinary knowledge and pedagogical enactment. The data from this study, therefore, offer empirical evidence of such a paradigm gap, calling for urgent curricular realignment.

Moreover, the stem-and-leaf distribution shown in

Figure 1 is not merely a statistical summary but a diagnostic representation of systemic inefficiency. The compact clustering of low scores indicates limited variance, suggesting that the underperformance is uniform rather than isolated. This uniformity points to institutional factors—such as the design of coursework, assessment practices, and supervision methods—rather than to individual aptitude differences. If most PSTs fail to reach the conceptual threshold necessary for effective teaching, then the responsibility extends beyond the learner to the training system itself. The implication is that reform efforts should focus not on remediation alone but on structural redesign, ensuring that MKT becomes the central, rather than peripheral, objective of teacher preparation.

From a cognitive perspective, the deficit in MKT revealed by these data likely originates from the absence of pedagogical reasoning opportunities during coursework. Many PSTs are taught to do mathematics but not to think about teaching mathematics. Without experiences that require justification, representation, or adaptation, their learning remains at the level of procedural recall. When subsequently tested on tasks requiring pedagogical interpretation—such as explaining why an algorithm works or choosing examples to illustrate a concept—they underperform. This phenomenon has been documented internationally, with Ball, Thames, and Phelps (2024) emphasizing that pedagogical reasoning is cultivated only through deliberate and structured practice, not by exposure to content alone.

The consequences of this MKT deficit are profound. Teachers who lack deep conceptual understanding are less able to recognize students’ misconceptions, design meaningful representations, or respond flexibly to unexpected classroom reasoning. Over time, this leads to a cycle of procedural teaching, where each generation of students learns mathematics as a set of mechanical rules devoid of meaning. In contexts such as Indonesia—where national assessments continue to show weak problem-solving and reasoning skills among students—the roots of these systemic challenges can often be traced to inadequate teacher preparation. Thus, improving MKT among PSTs is not simply a matter of academic interest but a national educational priority.

To address these concerns, teacher education programs must embed MKT explicitly within their pedagogical framework. This involves restructuring coursework to integrate mathematical content with pedagogical application, emphasizing how concepts are learned, represented, and reasoned about by students. Approaches such as lesson study, task-based learning, and practice-based teacher education can serve as effective models for fostering MKT development. These models encourage PSTs to analyze student thinking, construct alternative representations, and justify instructional choices—all of which directly cultivate the specialized knowledge necessary for teaching mathematics effectively.

The discrepancy highlighted by the mean score analysis serves as a quantitative reflection of a qualitative deficiency: the insufficient intertwining of mathematical understanding and pedagogical competence in teacher education. The data in

Figure 1 should thus be interpreted not as a measure of failure but as a roadmap for reform. By grounding teacher education in the principles of MKT—bridging content, pedagogy, and student cognition—Indonesia can move toward cultivating teachers who are not merely conveyors of procedures but facilitators of mathematical reasoning. Such a transformation, though challenging, is essential for elevating both the quality of mathematics instruction and the nation’s broader educational outcomes.

This gap becomes even more concerning when contextualized within Shulman’s (1986) framework of teacher knowledge, which distinguishes between subject matter knowledge and pedagogical content knowledge (PCK)—the latter being essential for effective teaching. Ma’s (2019) concept of “profound understanding of fundamental mathematics” (PUFM) further emphasizes that teaching elementary mathematics demands more than procedural fluency; it requires coherence, multiple perspectives, and the ability to anticipate student misconceptions. Yet, the curriculum described—comprising 18 units of general mathematics content and 54 units of professional education—fails to integrate these dimensions. The absence of courses explicitly designed to cultivate knowledge of content and students (KCS) or knowledge of content and teaching (KCT), as delineated in Ball et al.’s (2025) MKT model, means PSTs graduate without the tools to transform mathematical ideas into accessible, meaningful instruction. Consequently, they enter classrooms unprepared to address the conceptual complexities inherent even in foundational topics like fractions, place value, or proportional reasoning.

Moreover, the curricular disconnect reflects a broader tension in teacher education systems worldwide: the prioritization of disciplinary rigor over pedagogical relevance. Content courses often mirror university-level mathematics, emphasizing proof, abstraction, and advanced topics irrelevant to elementary classrooms, while professional courses focus on generic teaching strategies devoid of subject-specific application. This bifurcation leaves PSTs stranded between two epistemologies—neither fully mathematicians nor yet skilled mathematics teachers. The result, as evidenced by

Figure 1, is a cohort of future educators who may possess declarative knowledge but lack the

usable knowledge required for responsive, equitable, and conceptually rich mathematics instruction. Addressing this requires more than incremental reform; it demands a reimagining of teacher education curricula through the lens of MKT, ensuring that every content and methods course explicitly bridges the gap between mathematical truth and pedagogical practice. Without such integration, efforts to improve student learning outcomes in mathematics will remain fundamentally constrained by the unaddressed knowledge deficits of those entrusted to teach it.

Figure 2.

Stem and leaf plot of the PST’s MKT scores.

Figure 2.

Stem and leaf plot of the PST’s MKT scores.

The stem-and-leaf plot presented above provides a detailed visualization of the distribution of a dataset with stems ranging from 5 to 21. Each stem represents a class interval, while the leaves indicate the frequency of data points within that interval. The frequency distribution reveals that the dataset exhibits a moderate spread, with values concentrated primarily between stems 10 and 15. This clustering indicates a possible central tendency within the mid-range values, which may reflect an underlying pattern or consistency in the measured variable.

In quantitative analysis, stem-and-leaf plots serve as a hybrid between graphical and tabular representations, offering both the precision of numerical data and the interpretative ease of a histogram. The current distribution shows frequencies peaking at stems 10, 11, and 14, each with 21 data points. This balanced yet prominent clustering suggests that the data may approximate a normal distribution, where mid-level values dominate, and extreme values are less frequent.

The relatively low frequencies at stems 5, 6, 19, and 20 imply that the dataset contains few extreme observations, thus minimizing the likelihood of significant skewness. However, the presence of an “Extreme” category (≥21) with one observation indicates at least one outlier or exceptionally high data point. This observation is critical for statistical inference, as outliers can disproportionately affect mean-based analyses, potentially distorting the representation of central tendency.

Analyzing the middle range (stems 9–15), it is evident that the data density remains consistently high, with frequencies between 14 and 21. This concentration demonstrates a strong central cluster, which may reflect stable performance or consistent behavior in the measured phenomenon. Such consistency is often desirable in educational, psychological, or experimental research, where uniformity within a population sample indicates controlled conditions and reliable outcomes.

The decreasing frequency pattern after stem 15 suggests a tapering effect toward higher values. This decline might indicate diminishing returns, reduced occurrences, or a ceiling effect within the measured parameter. In educational measurement, for instance, this pattern could signify that fewer participants achieve extremely high scores, a common feature in assessments with moderate difficulty and well-calibrated testing instruments.

From a methodological perspective, the stem-and-leaf structure facilitates rapid detection of symmetry, skewness, and kurtosis. The present data appears moderately symmetrical, with no excessive accumulation at the lower or upper ends. Such balance implies a well-designed instrument capable of differentiating among respondents without overemphasizing either end of the performance spectrum. Consequently, the plot supports the reliability of the dataset as a valid representation of the population being studied.

The stem-and-leaf plot not only illustrates frequency distribution but also provides inferential insight into the overall structure and behavior of the dataset. The central clustering between stems 10 and 15 reflects a high degree of data stability, while the gradual frequency reduction toward both extremes suggests limited variability. This distributional pattern aligns with statistical expectations for controlled experimental data, underscoring the robustness and interpretative value of this graphical summary in quantitative research.

Mathematical Knowledge Items Found Difficult by Respondents

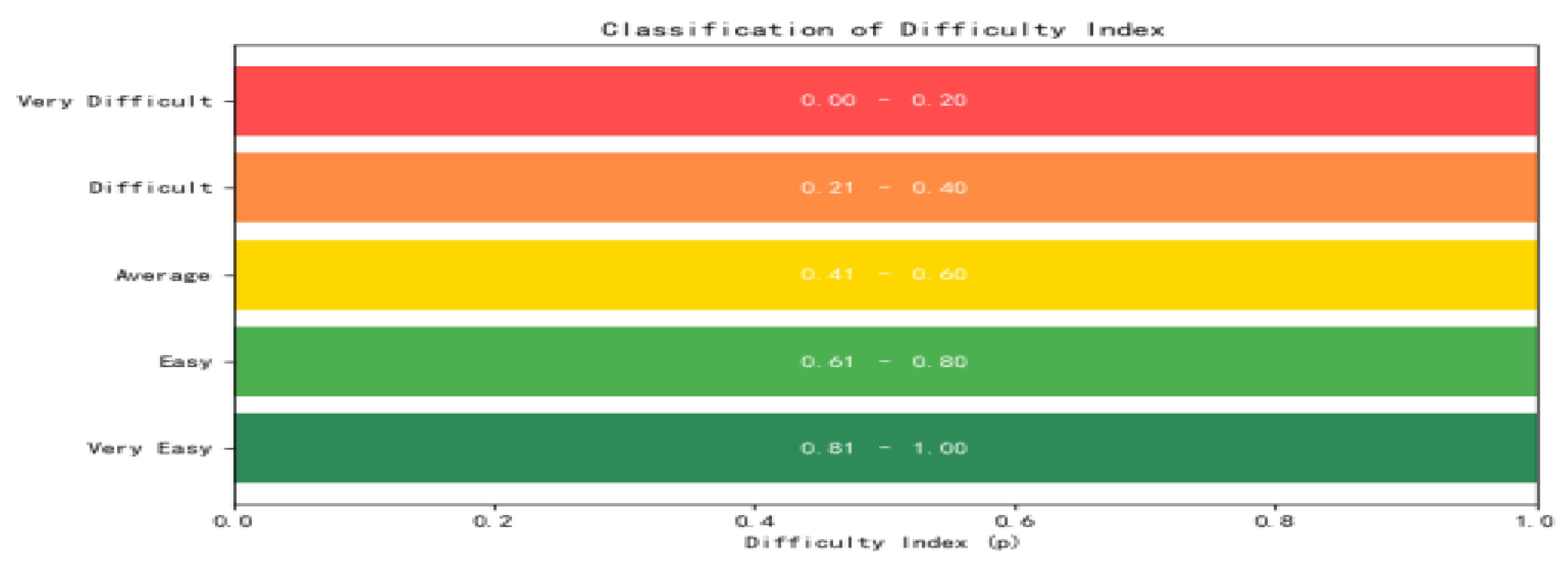

Difficulty index is a behavioral measure defined as the proportion of examinees answering an item correctly. It is both a characteristic of the item and the examinee and is relevant to for assessing whether a student has learned the concept being tested. For the purpose of this study, items in the MKT test were classified using the common rule of thumb presented under the data processing portion of this article.

Table 2 presents the number or percentage of respondents who correctly answered the items in the test, difficulty levels and item domains. Twenty-four or around 70% of the items were found difficult and very difficult by the pre-service teachers. Ten of these items are under the SMK domain (common content knowledge – 4; specialized content knowledge – 6) and 14 items were on the PCK domain (knowledge of content and students – 6; knowledge of content and teaching – 8). This indicates that the examinees encountered more difficulty on PCK items than SMK items. This difficulty may be due to students not learning the content and non-exposure to activities that may develop both SMK and PCK in the different content and pedagogy courses offered in their teacher education curriculum. The most difficult was item 32 which is asks for an appropriate example to introduce the concept of primes and composites. Item 6 which is a knowledge of content and teaching was the only item found very easy by the respondents. This item asks about the most appropriate tool to use to introduce the idea of grouping by tens to students. Basically, this concept is introduced as early as grade one. The most difficult item was on choosing appropriate examples for dividing fractions. This was correctly answered by only 11 or 6% percent of the study sample. This difficulty can be explained by the PST’s lack of mastery of the concepts and skills about fractions. In fact, three of the most difficult items were on fractions. The PST’s may be able to perform operations using varied strategies but they cannot explain why a procedure work because their conceptual understanding of fractions is fragmented and disconnected, (Nillas, (2023); Leung, & Carbone, (2023); Son, & Lee, (2024); Bentley, & Bossé, (2018). It follows that without a strong conceptual understanding of fractions one will not be able to identify an appropriate example for dividing fractions.

The difficulty index, defined as the proportion of examinees who answer a test item correctly, serves as a critical psychometric indicator that reflects both the cognitive demand of an item and the preparedness of learners to engage with the underlying concept. In the context of this study conducted among Indonesian preservice teachers (PSTs), the difficulty index was employed not merely as a statistical descriptor but as a diagnostic lens to uncover systemic gaps in teacher education. Using the widely accepted classification framework—where items with p ≤ 0.40 are deemed “difficult” or “very difficult”—the analysis revealed that approximately 70% (24 out of 35) of the MKT test items fell into these challenging categories. This high concentration of difficult items signals a profound misalignment between the mathematical knowledge PSTs possess upon graduation and the specialized knowledge required for effective elementary mathematics instruction. Crucially, this finding is not isolated to procedural incompetence but points to deeper deficits in conceptual coherence and pedagogical reasoning, particularly in foundational domains such as number theory and rational numbers.

A closer examination of item distribution across knowledge domains further illuminates the nature of this deficit. Of the 24 difficult or very difficult items, 14 belonged to the Pedagogical Content Knowledge (PCK) domain—specifically, six under Knowledge of Content and Students (KCS) and eight under Knowledge of Content and Teaching (KCT)—while the remaining ten were situated within Subject Matter Knowledge (SMK), comprising four items of Common Content Knowledge (CCK) and six of Specialized Content Knowledge (SCK). The disproportionate difficulty in PCK items suggests that PSTs are not only struggling with advanced mathematical ideas but, more critically, with the transformation of those ideas into teachable forms. This is particularly alarming in the Indonesian context, where national curricula emphasize student-centered, conceptual approaches to mathematics (e.g., Kurikulum Merdeka), yet teacher preparation programs continue to prioritize abstract mathematical content over context-responsive pedagogy. The inability to anticipate student misconceptions or select developmentally appropriate representations—core components of PCK—undermines the very foundation of effective mathematics teaching.

The most difficult item in the entire instrument, Item 32, which asked PSTs to select an appropriate example to introduce prime and composite numbers, was correctly answered by only 6% of respondents. Similarly, three of the five most challenging items centered on fraction division—a domain consistently identified in global literature as a persistent stumbling block for both students and teachers. PSTs in this study could often execute fraction operations using rote algorithms but failed to justify why a particular method works or to choose a meaningful real-world context that illustrates the concept of division of fractions. This pattern aligns with findings by Nillas (2023) and Leung & Carbone (2023), who argue that procedural fluency without conceptual grounding leads to fragile knowledge that collapses under pedagogical demands. In Indonesia, where fraction instruction often begins in Grade 4 but is rarely revisited with depth in teacher education, this gap is exacerbated by curricular fragmentation and a lack of vertical articulation between primary mathematics and university-level content courses.

Conversely, the only “very easy” item (Item 6)—which asked about the most appropriate manipulative to introduce grouping by tens—was answered correctly by the vast majority of PSTs. This item’s accessibility likely stems from its alignment with early-grade numeracy practices that PSTs themselves experienced as learners and frequently observe during school placements. The stark contrast between this item and those on fractions or number theory reveals a troubling asymmetry: PSTs are relatively comfortable with concrete, early-childhood mathematical representations but struggle significantly with the abstract reasoning and pedagogical design required for upper-elementary concepts. This suggests that teacher education in Indonesia may inadvertently reinforce a “primary school mindset” that prioritizes counting and basic operations while neglecting the development of multiplicative reasoning, proportional thinking, and number theory—domains essential for teaching Grades 4–6 effectively.

These findings collectively underscore a critical curricular shortcoming: despite completing 18 credit units of mathematics content courses and 54 units of professional education, Indonesian PSTs receive minimal exposure to the specialized mathematical knowledge that Ball et al. (2024) and Ma (2019) identify as indispensable for teaching. Courses rarely integrate tasks that require PSTs to analyze student work, compare solution strategies, or design conceptually coherent lesson sequences—activities proven to develop both SCK and PCK. Without deliberate, sustained engagement with such practices, PSTs graduate with fragmented knowledge that is insufficient for the demands of modern Indonesian classrooms. Therefore, reforming teacher education must go beyond increasing course loads; it requires a paradigm shift toward integrating MKT as a core organizing principle across all mathematics and methods courses, ensuring that future teachers not only know mathematics but know how to teach it meaningfully.

These findings collectively reveal a critical curricular deficit in Indonesian teacher education: despite completing 18 credit units of mathematics content courses and 54 units of professional education, preservice teachers (PSTs) receive minimal exposure to the specialized forms of mathematical knowledge that Ball, Thames, and Phelps (2024) and Ma (2019) identify as essential for effective teaching. Traditional coursework remains largely bifurcated—mathematics departments emphasize abstract, advanced topics disconnected from elementary curricula, while professional education courses often address pedagogy in generic, content-agnostic ways. As a result, PSTs rarely engage in high-leverage teaching practices such as analyzing student work samples, comparing alternative solution strategies, justifying mathematical procedures, or designing conceptually coherent lesson sequences—tasks empirically shown to cultivate both Specialized Content Knowledge (SCK) and Pedagogical Content Knowledge (PCK). Without deliberate, sustained opportunities to integrate content and pedagogy through such practice-based activities, PSTs graduate with fragmented, inert knowledge that fails to meet the demands of contemporary Indonesian classrooms, particularly under reform-oriented frameworks like Kurikulum Merdeka. Consequently, improving teacher preparation cannot be achieved merely by increasing course loads or adding isolated workshops; it requires a fundamental paradigm shift—one that positions Mathematical Knowledge for Teaching (MKT) as the central organizing principle across the entire teacher education curriculum. Only through such systemic integration can future teachers develop not only the capacity to do mathematics, but the professional expertise to teach it meaningfully, equitably, and effectively.

The structural disconnect between mathematics content courses and professional pedagogy courses in Indonesian teacher education programs reflects a deeper epistemological divide: the persistent belief that teaching is the mere application of pre-existing knowledge, rather than a complex practice that generates its own specialized expertise. This bifurcation leads to what Ball et al. (2008) describe as “unusable knowledge”—mathematical understanding that, while technically correct, cannot be mobilized to explain a student’s error, justify a procedure, or select a developmentally appropriate representation. For instance, a PST may correctly prove that the sum of two even numbers is even using algebraic notation (a university-level skill), yet remain unable to guide a Grade 3 student through the same concept using concrete manipulatives or visual patterns. This gap is not a failure of individual PSTs but a systemic outcome of curricula that treat “knowing mathematics” and “teaching mathematics” as separate competencies. In reality, as Ma (2019) compellingly argues, profound understanding of fundamental mathematics (PUFM) only manifests when content is examined through the lens of learner cognition and instructional design. Without intentional integration, PSTs internalize the false dichotomy that “real mathematics” happens in lecture halls, while “simplified teaching” occurs in schools—thereby devaluing the intellectual rigor of elementary teaching. This mindset undermines the professional status of primary educators and perpetuates low expectations for both teachers and students. Reform efforts must therefore challenge this epistemological hierarchy by redefining what counts as legitimate mathematical work in teacher education. Only when designing a fraction lesson is seen as intellectually equivalent to solving a differential equation will PSTs develop the MKT needed for transformative teaching.

Moreover, the absence of authentic teaching tasks in university coursework deprives PSTs of the very experiences that build professional judgment. Analyzing actual student work—such as a child’s incorrect algorithm for dividing fractions or a misconception that 0.5 is larger than 0.25 because “5 is bigger than 25”—requires more than content knowledge; it demands the ability to interpret thinking, diagnose conceptual gaps, and respond pedagogically. Yet, most Indonesian PSTs encounter such tasks only during brief practicum periods, often without structured guidance or reflective support. In contrast, high-performing systems like Singapore embed student work analysis throughout teacher preparation, using it as a core tool for developing KCS (Knowledge of Content and Students). Similarly, designing lesson sequences that build conceptual coherence—such as progressing from equal sharing to partitive division to quotative division in fractions—requires KCT (Knowledge of Content and Teaching), which cannot be acquired through passive observation alone. These are high-leverage practices that must be practiced, critiqued, and refined in safe, supervised environments before PSTs enter classrooms. When teacher education programs omit them, they implicitly signal that such knowledge is optional or intuitive, rather than professional and learnable. The consequence is a generation of teachers who rely on textbooks or rote procedures, lacking the adaptive expertise to respond to diverse learners. To close this gap, Indonesian universities must redesign courses around authentic artifacts of practice: student errors, curriculum materials, classroom videos, and lesson plans—transforming classrooms into laboratories of professional learning.

The policy environment in Indonesia, particularly the rollout of Kurikulum Merdeka, creates both urgency and opportunity for such transformation. Kurikulum Merdeka emphasizes student-centered learning, critical thinking, and project-based activities—all of which demand high levels of MKT from teachers. However, without parallel reform in teacher preparation, this curriculum risks becoming another well-intentioned but poorly implemented initiative. PSTs trained in traditional, transmission-oriented models are ill-equipped to facilitate open-ended mathematical investigations or support collaborative problem-solving. They may understand the goals of the new curriculum but lack the means to enact them. This implementation gap is not unique to Indonesia; global studies show that curriculum reform fails when teacher knowledge is not addressed concurrently. Therefore, the Ministry of Education, Culture, Research, and Technology (Kemdikbudristek) must align teacher education standards with Kurikulum Merdeka’s pedagogical vision. This includes revising LPTK (Lembaga Pendidikan Tenaga Kependidikan) accreditation criteria to require evidence of MKT development, such as performance assessments where PSTs analyze student thinking or design conceptually rich tasks. Furthermore, national certification exams for teachers (e.g., PPG) should include MKT-focused items, creating a powerful incentive for universities to prioritize this knowledge. Policy coherence between school curriculum and teacher preparation is not optional—it is essential for systemic improvement.

Digital innovation offers a promising pathway to scale MKT development, especially in geographically dispersed regions like North Sumatra. AI-enhanced platforms—such as GeoGebra integrated with project-based learning (PjBL) models—can simulate classroom scenarios where PSTs experiment with representations, receive instant feedback on their explanations, and explore the impact of different examples on virtual student understanding. For instance, a PST could test multiple ways to introduce prime numbers—using arrays, factor trees, or Mandailing cultural patterns—and observe how each affects comprehension. Such tools democratize access to high-quality practice, particularly where mentor teachers with strong MKT are scarce. Community-driven initiatives, such as the “Generasi Mandailing Natal Bersinar” program, can further amplify this impact by creating peer learning networks where PSTs collaboratively analyze local teaching challenges and co-design culturally responsive materials. However, technology alone is insufficient; its effectiveness depends on pedagogical design. Digital tasks must be grounded in MKT principles—focusing on justification, representation, and student thinking—not merely digitized worksheets. When thoughtfully implemented, these innovations can transform teacher education from a passive, isolated experience into an active, collaborative, and contextually grounded professional journey. In doing so, they bridge the gap between university theory and classroom reality.

Ultimately, the underdevelopment of MKT among Indonesian PSTs is not a technical problem to be solved with more courses, but a cultural and institutional one requiring reimagined professional identities. Teaching must be reconceptualized not as a fallback career for those who “can’t do real math,” but as a sophisticated intellectual practice that demands deep, specialized knowledge. This shift begins with how we prepare teachers: by centering their learning on the core work of teaching—explaining, representing, questioning, and responding—rather than on abstract mathematical theorems. It continues with how we support them: through induction programs that treat early teaching as continued learning, not trial by fire. And it culminates in how we value them: by recognizing that a Grade 4 teacher who helps a child grasp why 1/2 ÷ 1/4 = 2 is performing work as vital—and as mathematically rich—as any university professor. Until this cultural shift occurs, curricular reforms will remain superficial, and PSTs will continue to graduate with knowledge that is fragmented, inert, and disconnected from the realities of their future classrooms. The path forward lies not in adding more content, but in transforming how we understand the very nature of mathematical knowledge for teaching. Only then can Indonesia build a teaching force capable of delivering on the promise of equitable, meaningful, and joyful mathematics education for all children.

Table 3 presents a comprehensive overview of the performance of 176 Indonesian preservice teachers (PSTs) on the Mathematical Knowledge for Teaching (MKT) test, revealing systematic patterns in their mastery across various domains of professional knowledge. Among the 35 items, only one—Item 6, which asked about the most appropriate manipulative tool for introducing the concept of grouping by tens—was classified as

very easy, with a correct response rate of 82%. This indicates the PSTs’ familiarity with basic instructional practices commonly encountered since primary education and frequently observed during teaching practicum. Conversely, most items were categorized as

difficult or

very difficult, with 24 out of 35 items (68.6%) having a difficulty index below 40%. These findings confirm that PSTs are relatively competent in handling concrete and routine pedagogical tasks but face substantial challenges when confronted with higher-order cognitive demands, such as conceptual justification, strategic example selection, or anticipating students’ thinking. This disparity suggests that teacher education in Indonesia remains focused on surface-level teaching practices rather than on the depth of professional knowledge required to support meaningful learning. Furthermore, the left-skewed score distribution (dominated by low scores) aligns with previous evidence that the average MKT performance is far below a perfect score. This represents not merely an individual deficiency but a systemic issue reflecting a curriculum that fails to meaningfully integrate mathematical content with pedagogy.

Domain-based analysis reveals a striking disparity between mastery of Common Content Knowledge (CCK) and more specialized forms such as Specialized Content Knowledge (SCK) and Pedagogical Content Knowledge (PCK). Although several CCK items (e.g., Items 3, 10, and 9) fell into the average category, most of the more complex CCK items—such as Item 1 (definition of zero, 20% correct) and Item 24 (concept of number, 21% correct)—were classified as very difficult. This suggests that even basic content understanding is fragile when probed through conceptually precise questions. However, the difficulty was far more pronounced in the SCK and PCK domains. For instance, Item 35 (justifying integer subtraction, SCK) was correctly answered by only 13% of participants, while Item 27 (selecting examples for fraction division, KCT) was answered correctly by merely 6%. The fact that nearly all very difficult items came from SCK or KCT/KCS indicates that PSTs not only lack deep mathematical understanding but also the skills to transform that knowledge into teachable forms. This aligns with the framework of Ball et al. (2024), which emphasizes that SCK and PCK are unique domains of knowledge not shared by non-teaching mathematicians. In Indonesia, where content courses rarely address pedagogical aspects and pedagogy courses seldom engage with authentic mathematical content, such integration is almost nonexistent.

The Knowledge of Content and Teaching (KCT) domain exhibits the most concerning level of difficulty, with 7 out of 10 KCT items categorized as very difficult. These items required PSTs to design representations, select instructional tools, or sequence examples—core competencies in effective lesson planning. For example, Item 32 (selecting examples for prime numbers, 10% correct) and Item 28 (choosing instructional materials for triangles, 10% correct) reveal the PSTs’ inability to understand how variation in examples influences students’ concept formation. They tended to select prototypical examples (such as equilateral triangles or odd prime numbers) without considering counterexamples or boundary cases (such as the number 2 or obtuse triangles), thereby reinforcing misconceptions. This reflects a lack of exposure to didactical design principles during teacher education. In real classrooms, such deficiencies directly affect students’ learning, leading to narrow and rigid conceptual understandings. Teacher education programs must explicitly train PSTs in pedagogical task analysis—not merely “what to teach,” but “how to teach it meaningfully.” Without such preparation, PSTs will continue to rely on intuition or habit rather than evidence-based instructional principles.

The Knowledge of Content and Students (KCS) domain also reveals serious deficits, with Item 16 (requesting explanation of an addition pattern procedure, 18% correct) and Item 21 (selecting a problem for proportional reasoning, 18% correct) being two of the most difficult items after Item 27. KCS demands an understanding of how students think, common misconceptions, and responsive strategies. However, Indonesian PSTs are rarely given opportunities to analyze authentic student work or design diagnostic questions during coursework. Consequently, they struggle to envision how students understand (or misunderstand) concepts such as number patterns or ratios. For instance, in proportional reasoning, many students rely on additive rather than multiplicative strategies—yet PSTs are not trained to recognize or address this. This highlights that teaching practice in Indonesia remains teacher-centered rather than student-centered. To strengthen KCS, teacher education programs should integrate case studies based on student work, classroom simulations, and video-based reflections. Only by positioning students as active subjects in the learning process can PSTs develop the cognitive empathy that forms the foundation of KCS.

The finding that only 9% of PSTs were able to correctly answer ≥50% of the items—as mentioned in previous analyses—is reinforced by the distribution in

Table 3: the majority of items had success rates below 50%, with 14 items scoring under 30%. This means that even “average” items were challenging for most participants. Moreover, not a single SCK or KCT item reached the

easy or

very easy category, confirming that knowledge specific to teaching mathematics is almost entirely absent from PSTs’ repertoires. The sharp contrast between Item 6 (82% correct, basic KCT) and Item 27 (6% correct, complex KCT) shows that PSTs can only handle very simple and routine pedagogical tasks. This is alarming given that the

Kurikulum Merdeka emphasizes project-based, reasoning-oriented, and problem-solving learning—all of which require high-level PCK. If preservice teachers are not equipped to meet these demands, curriculum implementation will fail at the classroom level. Thus,

Table 3 serves not merely as a statistical report but as an early warning to policymakers in Indonesian teacher education.