1. Introduction

In 2022, Portugal had a total of 12.383 convicted individuals, out of which 9.913 were serving prison sentences. Crimes against people accounted for the highest number of convictions resulting in imprisonment, with 3.063 people, followed by crimes against property with 2.394 people (DGRSP, 2022). According to data from the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD, 2020), as of May 2020, Portugal ranked 15th in terms of imprisonment rates. The country had 124 imprisoned individuals per 100.000 inhabitants.

Crime represents not only a threat to security but also imposes a substantial financial burden on society across various dimensions, including social, economic, legal, and political aspects (Cruz et al., 2020). Specifically, it incurs significant costs for funding prisons, law enforcement, and security systems (Burgess, 2020). Globally, the prison population has surpassed 10 million, with an approximate 20% increase since the year 2000. This rise could be attributed to criminal recidivism (Balafoutas et al., 2020), which ranges from 35% to 67% in several countries (Meijers et al., 2015). Although defining what constitutes criminal recidivism poses certain difficulties, it can generally be understood as a relapse into criminal behavior that may result in a new conviction and/or imprisonment. Contrary to the recorded global crime rates, it seems that the rate of criminal recidivism has not decreased in recent years (Fazel & Wolf, 2015).

The concept of crime can be defined as "the intentional practice of an act considered socially harmful or dangerous and specifically defined, prohibited, and punishable under criminal law" (Edge et al., 2020, p. 1). Criminal behavior is a complex phenomenon, both in a social and clinical context and presents a constant challenge in society. It requires an integrative and multidisciplinary approach based on the heterogeneity of criminal acts and individual' behavior (Broomhall, 2005; Cruz et al., 2020; Reddy et al., 2018; Sullivan, 2019). Factors such as emotional stress, low socioeconomic status, educational and cultural background, peer groups, living in socially disadvantaged contexts, substance use, physical and sexual abuse, prenatal complications, parental dynamics, genetic predisposition, and brain damage can serve as predictors of aggressive and violent behavior (Braga et al., 2017; Broomhall, 2005; Brower, 2001; Cruz et al., 2020; Derzon, 2010; Stanley & Goddard, 2004).

Antisocial behavior is analyzed based on clinical and legal concepts. The clinical perspective involves the use of diagnostic criteria defined in the DSM-5 (APA, 2014), which categorizes the behavior under personality disorders. The overall manifestation of this disorder includes contempt and violation of others' rights, irresponsible behavior, lack of respect for others, inappropriate behavior that is difficult to control, and an inability to conform and adapt to social norms. Typically, it begins in childhood and persists into adulthood (APA, 2014; Morgan & Lilienfeld, 2000; Ogilvie et al., 2011). On the other hand, the legal perspective examines criminality and delinquency as unlawful actions that may result in imprisonment (Morgan & Lilienfeld, 2000; Ogilvie et al., 2011).

Executive functions which comprise a set of higher-order cognitive functioning seem to play a major role in engaging in antisocial, aggressive, and/or violent behavior (Altikriti, 2020; Morgan & Lilienfeld, 2000; Ogilvie et al., 2011). Executive dysfunction, commonly associated with damage to the frontal lobes, is characterized by maladaptive and inappropriate behavior, along with personality changes (Morgan & Lilienfeld, 2000; Ogilvie et al., 2011). It is also associated with committing aggressive acts (Altikriti, 2020; Morgan & Lilienfeld, 2000; Ogilvie et al., 2011; Seruca & Silva, 2016; Shumlich et al., 2019).

Executive functioning has been associated with the frontal lobes, specifically the pre-frontal and subcortical areas. These regions are involved in regulating behavior through processes such as planning, self-monitoring, problem-solving, response inhibition, strategy development and implementation, and working memory (Ardila, 2013; Márquez et al., 2013). These cognitive processes contribute to the resolution of complex problems and are influenced by both external and internal factors (Tirapu-Ustárroz et al., 2012; Verdejo & Bechara, 2010). Based on the multidimensional construct model, a theory was developed that divides executive functions into hot and cold processes, based on the premise that these functions vary depending on the motivational meaning of a situation (Zelazo & Carlson, 2012). Although executive functions operate together in a coordinated system, they can be distinguished between purely cognitive processes (i.e., cold), which are associated with non-affective and abstract situations, and more intuitive processes linked to situations with emotional and affective meaning (i.e., hot) (Zelazo & Carlson, 2012). From a neuroanatomical point of view, cold processes are associated with the lateral pre-frontal cortex, while hot processes are associated with the orbitofrontal cortex (Zelazo & Carlson, 2012). Cold executive functions tend to involve inhibitory control, working memory, cognitive flexibility, planning, and attentional processes (De Brito et al., 2013). Hot executive functions, on the other hand, include delayed gratification and affective decision-making (De Brito et al., 2013; Kuin et al., 2019; Tsermentseli & Poland, 2016). Additionally, the literature shows that individuals with lesions in the orbitofrontal cortex generally exhibit deficits in measures that assess hot executive functions (e.g., Iowa Gambling Task), but their performance is not compromised in measures that assess cold executive functions (e.g., Wisconsin Card Sorting Test) (Zelazo & Carlson, 2012).

Taking this approach to executive functions into account, the important role they play in understanding violent and aggressive behavior becomes evident, as they are responsible for directing behavior, assisting in decision-making, and inhibiting inappropriate responses or actions (Ogilvie et al., 2011). The relationship between executive functions and crime is well established, as deficits in brain functioning, particularly in the frontal and pre-frontal regions, are associated with violent and criminal behavior (e.g., Kuin et al., 2019; Reddy et al., 2018). These deficits contribute to difficulties in regulating and controlling behavior (Miyake et al., 2000; Reddy et al., 2018).

Generally, individuals with violent and aggressive behavior are characterized by immaturity and impulsivity. They tend to have deficits in social and cognitive skills, such as problem-solving ability, effectively interpreting social cues, flexibility in adapting to norms, empathetic behavior towards others, poor judgment in situations, difficulties in planning and decision-making, and difficulties in inhibiting inappropriate responses (Bergeron & Valliant, 2001; Chandler, 1973; Slaby & Guerra, 1988). When evaluated, they tend to score lower on tests of executive processes, particularly those assessing inhibitory control (Cruz et al., 2020; Hancock et al., 2010; Meijers et al., 2017; Wallinius et al., 2019).

An important factor in individuals with violent and aggressive behavior is their ability or inability to make decisions, often guided by impulsivity and, consequently, leading to less appropriate or disadvantageous choices (Kuin et al., 2019; Yechiam et al., 2008). There is evidence that the tendency to take greater risks in decision-making is positively related to aggressive and impulsive behaviors, particularly in emotionally activating situations (Kuin et al., 2019; Yechiam et al., 2008). This phenomenon can be explained by the somatic marker hypothesis (Bechara, 2005), which proposes that decision-making can be based on long-term outcomes using cognitive and emotional processes. According to the author, the ability to make decisions depends on neuronal substrates that regulate homeostasis, emotions, and feelings. The ventromedial pre-frontal cortex and the amygdala are involved in this process, triggering somatic states (i.e., a collection of stored affective and emotional responses that influence actions and decisions). The amygdala responds to environmental events, while the ventromedial pre-frontal cortex does so through memories, knowledge, and cognition. The final result, whether positive or negative, depends on the decision based on the immediate and future perspectives of an option, which can trigger various affective responses (Bechara, 2005).

Furthermore, the literature shows a relationship between executive dysfunctions and manifestations of criminal behavior, such as recidivism. Although it remains unclear whether executive deficits are more severe in repeat offenders (e.g., Seruca & Silva, 2015), Ross and Hoaken (2011), for example, demonstrated that recidivist individuals show lower performance in executive measures compared to first time inmates. Meijers et al. (2015) stated that executive dysfunction, along with difficulty in self-regulation, can lead to an increased rate of recidivism. Therefore, the question arises as to whether executive dysfunctions are the direct cause of repeated criminal behavior over time or whether the prison environment also contributes to an exacerbation of these deficits and, consequently, a greater risk of recidivism (Meijers et al., 2018).

Based on the relationship between executive functions and crime, this study aims to evaluate and characterize the executive functioning of a group of inmates sentenced for different types of crime. Specifically, it seeks to understand the potential influence of factors such as the criminal background, the type of crime, and the duration of sentence imposed as indices of the severity of criminal behavior on neurocognitive functioning, but also to explore whether there are differences among participants in decision making through measures assessing hot executive functions (performance on the Iowa Gambling Task) and cold executive functions (performance on the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test and Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale). Additionally, it also seeks to understand the impact of incarceration on neurocognitive functioning by examining the effect of the length of imprisonment. Therefore, we have hypothesized that a longer duration of sentences (H1) and length of imprisonment (H2) would be associated with poorer executive functioning.

From a scientific standpoint, this study is expected to contribute to a better understanding of the neurocognitive profile of incarcerated individuals and whether impairments in executive functions are associated with the severity and continuity of criminal behavior.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

The sample consisted of 30 male individuals in prison. Only individuals without a formal diagnosis of psychopathology and with at least a completed first cycle of basic education were included (i.e., four years of formal education). The participants had an average age of 29.13 years (SD = 6.19) and the majority (46.7%) had incomplete education at the second cycle level (i.e., six years of formal education). They were serving effective prison sentences in a prison located in the Lisbon metropolitan area. Out of the total participants, 22 were serving their first effective prison sentence, while the remaining eight were repeat offenders. In terms of the types of crime, five participants were incarcerated for non-violent crimes (e.g., theft; drug traffic), while the remaining 25 were incarcerated for violent crimes (e.g., murder; robbery). Furthermore, out of these participants, 17 were primary offenders involved in violent crimes, and five were involved in non-violent crimes. Only eight participants were both repeat offenders and involved in violent crimes. Regarding the participants' criminal history, recidivism was determined through self-reporting, considering whether they had previously complied with another measure, whether it involved deprivation of liberty or not. Twenty participants (66.7%) reported having used psychoactive substances. The duration of the sentences ranged from 42 to 366 months, with an average of 173.40 months (SD = 83.11). The participants had been incarcerated on average for 92.53 months (SD = 50.92), with a minimum of 11 months and a maximum of 180 months. The interval data for Duration of Sentence Imposed and Length of Imprisonment were converted to binary variables based on the median value in months (Duration of Sentence Imposed, Mdn = 180 months; Length of Imprisonment, Mdn = 94.50 months). Detailed information on the sociodemographic characteristics of the sample is provided in

Table 1.

2.2. Measures

Sociodemographic Questionnaire - The sociodemographic questionnaire aims to collect information regarding age, gender, education, marital status, profession before imprisonment, length of sentence assigned, reason for the sentence, years of sentence already served, criminal record, substance use, and clinical history.

Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) (Nasreddine et al., 2005; Portuguese version by Simões et al., 2014) is a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. This test consists of eleven tasks that assess cognitive domains such as executive functions, visuospatial capacity, memory, attention, concentration, working memory, language, and spatial and temporal orientation. The administration time is approximately 10 to 15 minutes, and the maximum score is 30 points (Freitas et al., 2011).

Digit Span - The Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale III (WAIS-III) (Wechsler, 1991; Portuguese version by Wechsler, 2008) allows evaluation of the capacity for recall, immediate repetition, and working memory. It consists of two tasks: one for repeating digits in direct order and another for repeating digits in reverse order. Each item has two trials that are scored from 0 to 2 points. The total score is 30 points, which corresponds to the sum of the direct order digits task (16 points) and the reverse order digits task (14 points) (Wechsler, 2008).

Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (WCST) (Heaton et al., 1993; normative data available from Faustino et al., 2020) is a test that assesses cognitive flexibility. The test consists of four stimulus cards and 128 response cards represented by different shapes, colors, and numbers. The objective is to match each response card to one of the stimulus cards, alternating between the three classification categories (i.e., color, shape, and number). During the test, the classification principles are not revealed to the participant; they are only told if their answer is right or wrong. The results of the test are translated into percentiles based on the raw score of the classification indexes. The test administration time varies between 20 and 30 minutes (Heaton et al., 2005).

Frontal Assessment Battery (FAB) (Dubois et al., 2000; Portuguese version by Lima et al., 2008) is a brief battery of neuropsychological assessment focused on frontal functions and executive functioning. This test consists of six subtests that assess abstract thinking, mental flexibility, motor programming, sensitivity to interference, inhibitory control, and environmental autonomy. Each subtest is scored between 0 and 3 points, with a total score of 18 points. The test administration time is approximately 10 minutes (Dubois et al., 2000).

Iowa Gambling Task (IGT) (Bechara et al., 1994) is a computerized test that evaluates decision-making capacity based on real-life situations, specifically the anticipation of risk in long-term decision-making. The IGT consists of four decks of cards (A, B, C, and D), each with different characteristics in terms of losses and/or gains during the task. The objective is to reach the end of the task with a positive balance, avoiding significant losses. The participant chooses a card from one of the four possible decks over 100 moves. Decks vary in terms of rewards and punishments, with some being more advantageous than others. The test results are obtained by subtracting the sum of all advantageous choices (decks C+D) from the sum of all risky choices (decks A+B) (Bechara et al., 1994).

2.3. Procedures

This study is part of a broader project called "Neurocognitive Assessment of the Prison Population," with data collected between 2017 and 2018 in a prison facility in the metropolitan area of Lisbon, Portugal. After obtaining ethical clearance from the Committee on Ethics and Deontology of Scientific Research at the School of Psychology and Life Sciences of Lusófona University (CEDIC) and authorization from the General Directorate for Reinsertion and Prison Services (DGRSP), the data collection process took place with a guarantee of anonymity and confidentiality. The participants signed an informed consent form, and it was clarified that participation did not involve any physical or psychological risks.

To assess the cognitive profile, five neuropsychological assessment measures were applied in two one-hour sessions. In the first session, the socio-demographic questionnaire, the MoCA test, the digit span test, and the WCST were administered. For the WCST, only four indices were analyzed: Perseverative Errors, Perseverative Answers, Number of Categories Completed, and Successful Trials to Complete the 1st Category. These indices are considered the most suitable in the literature for evaluating abilities such as problem-solving, planning, and cognitive flexibility (e.g., Angrilli et al., 2013; Kelly et al., 2002; Ross & Hoaken, 2011; Sreenivasan et al., 2008; Veneziano & Veneziano, 2004).

In the second session, the FAB and IGT tests were administered. In addition to analyzing the decks of cards (Deck A, Deck B, Deck C, and Deck D) selected by the participants, which indicate the number of times each deck (advantageous or disadvantageous) was chosen, data related to the blocks (Net1, Net2, Net3, Net4, and Net5) were considered to evaluate the participants' performance and learning progression in each block. The total value (Net_Total) variable was also used to assess the participants' overall performance in the task (Areias et al., 2013). Furthermore, a survey was conducted to gather sociodemographic data. Information regarding sentence duration and length of imprisonment was collected from the individual records. The neurocognitive assessment was conducted individually in a room, guaranteeing the conditions of privacy and confidentiality. A trained student enrolled in the Neuropsychology Master’s program conducted the assessments. The entire procedure of neurocognitive assessment lasted two one-hour sessions.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

The data were entered into IBM SPSS Statistics software (Version 23) for statistical analysis. Descriptive statistics methods were used to characterize the sample, while inferential statistics methods were employed to test the study's objectives using ANOVAs. The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to determine the normal distribution of the sample, considering the sample size (n = 30). Although some of the tested variables violated the assumptions of normality (e.g., MoCA and WCST), parametric procedures were still used to test differences between levels of the independent variables against the dependent variables related to neurocognitive performance. ANOVAs were chosen due to the results not differing from the non-parametric alternative procedures. Since parametric tests are generally more robust, they were preferred for reporting purposes.

The independent variables were related to criminal behavior, namely the Duration of Sentence Imposed, and the Length of Imprisonment. The dependent variables were related to neurocognitive performance of executive functions and decision-making. The alpha level for the statistical procedures was set at .05.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics for Neurocognitive Variables

The first aim was to describe the variables related to neurocognitive functioning using mean scores, standard deviation, and lower and upper levels for a 95% confidence level. The mean scores indicate that overall cognitive function measured with (MoCA, Digit Span, WCST, FAB and IGT) is lower than the mean score of a normative sample. However, these scores fall within two standard deviations of the normative scores, suggesting no significant deviations from the normative data. The same applies to the WCST, for which normative data for the Portuguese population is available. In the WCST, we utilized approximate age and education levels from our sample.

Table 2 provides a summary of the descriptive statistics for the five measures used to assess participants' executive functioning.

3.2. Decision-Making in the Iowa Gambling Task

The IGT was analyzed according to Net (performance in 20 card bins) and Deck (number of choices of each card deck). This analysis was conducted using repeated measures ANOVA to compare performance based on Net and Deck. The initial ANOVA for Net, which had five levels, did not reveal statistically significant differences across the levels of this variable (i.e., each set of 20 card picks).

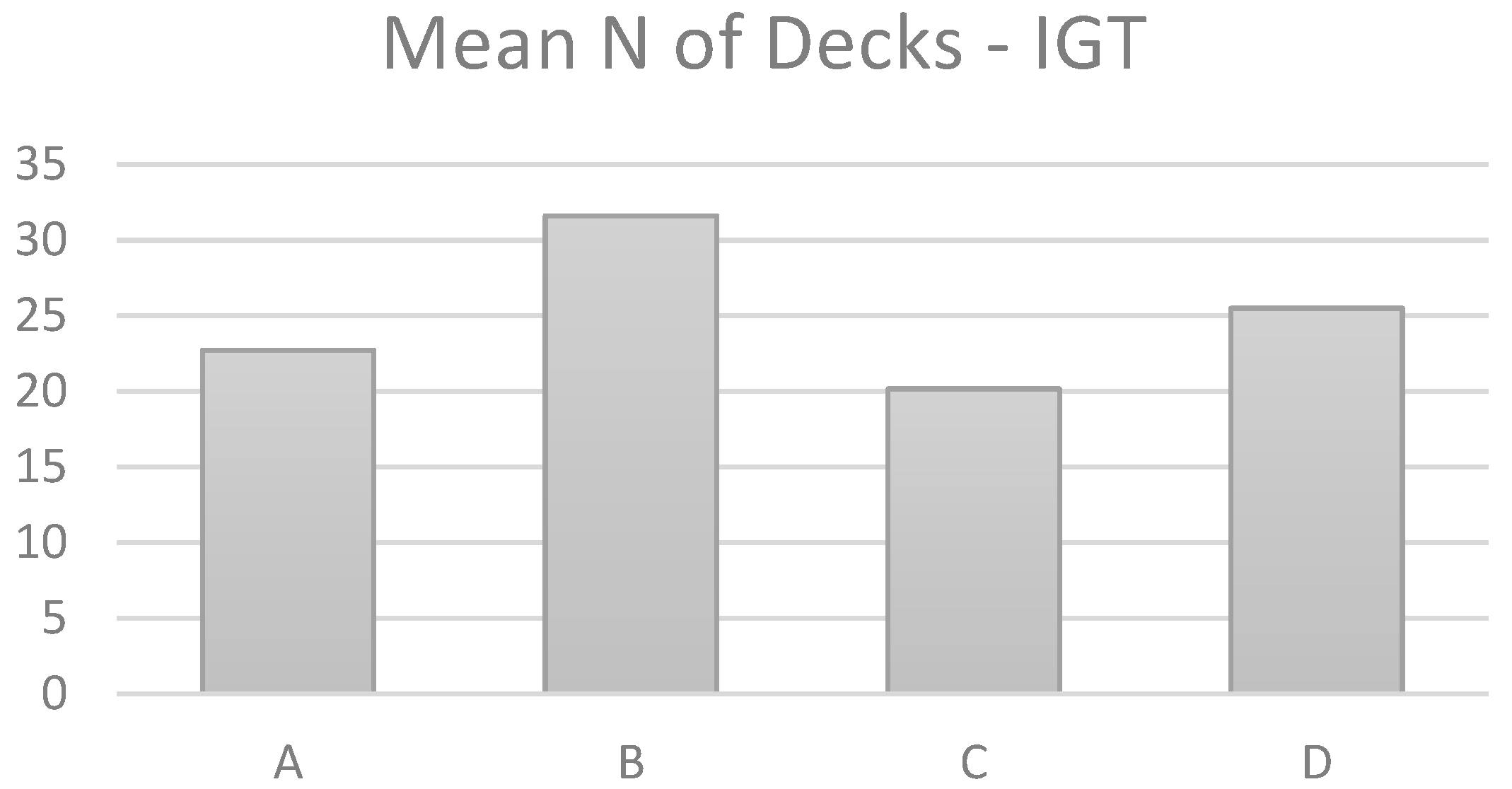

However, the same analysis conducted on Deck, which had four levels, showed a main effect (F(3, 51) = 4.405; p < .01), indicating a significant difference in the number of card picks from each deck. Post-hoc analysis with Bonferroni adjustment indicated that Deck B was chosen significantly more often than Deck A and Deck C (p < .05).

Figure 1 illustrates the number of cards picked for decks A, B, C, and D, where decks A and B were disadvantageous decks, and decks C and D were advantageous decks.

3.3. Association Between Criminal Behavior, Education and Age

Before testing the objectives, an exploratory analysis was conducted to determine whether the independent variables, such as Duration of Sentence Imposed (below/above Mdn) as a proxy for the severity of criminal behavior, and Length of Imprisonment (below/above Mdn), could be influenced by factors such as age or education. A Chi-square association test was performed to examine the associations between years of formal education and the independent variables. The results indicated no significant associations (all p-values > .05). However, when considering age, t-tests revealed differences for Duration of Sentence Imposed (t(28) = 3.909, p < .001) and Length of Imprisonment (t(28) = -4.359, p < .001), suggesting that individuals with longer sentences and longer imprisonment times tend to have a higher mean age. To account for the potential covariance between age and the independent variables, age was controlled in subsequent analyses.

Table 3 presents the means and standard deviations for each subgroup, specifically focusing on the age variable.

3.4. Differences in Criminal Behavior Related to Sentence Duration and Executive Functions

This analysis was conducted to test whether the severity of criminal behavior, as indicated by the duration of the sentence imposed, had an impact on executive functioning, as evaluated through the FAB and WCST. We also examined whether the length of imprisonment affected decision-making, as evaluated through the IGT. The analysis utilized MANCOVA to test these effects on the underlying dimensions of the FAB and WCST, and a mixed repeated measures ANCOVA for the IGT, controlling for age effects.

Regarding the FAB, the MANCOVA included the six dimensions (abstract thinking, mental flexibility, motor programming, sensitivity to interference, inhibitory control, and environmental autonomy) and the duration of the sentence imposed (below/above median) as fixed effects, with age included as a covariate. The analysis revealed a significant multivariate effect (F(5, 23) = Wilks' Lambda = 0.475; F = 5.092; p < 0.001). This effect was further examined through between-subjects univariate tests, which indicated better results in executive functions in the group with the lower duration of the sentence imposed for mental flexibility (F(1, 27) = 7.218; p < 0.05) and sensitivity to interference (F(1, 27) = 6.998; p < 0.05), as depicted in

Table 4.

The same analysis was performed on the WCST to assess whether this test exhibited differences based on the duration of the sentence imposed while controlling for age effects. However, the MANCOVA did not demonstrate a multivariate effect or univariate effects on the dimensions of the WCST (all p's > 0.05).

Table 5 illustrates the mean scores in each domain of the WCST.

3.5. Differences in Criminal Behavior Related to Imprisonment Duration and Decision-Making

In the Iowa Gambling Task (IGT), two separate mixed repeated measures ANOVA tests were conducted to examine the impact of Length of Imprisonment on decision-making. The variables analyzed were Net and Deck.

For the Net variable, the ANOVA included the within-subjects factor Net with 5 levels (Net1 vs. Net2 vs. Net3 vs. Net4 vs. Net5). Length of Imprisonment was considered a fixed factor, and age was included as a covariate. However, this ANOVA did not yield any significant results for either the main effects and the interaction effects between variables.

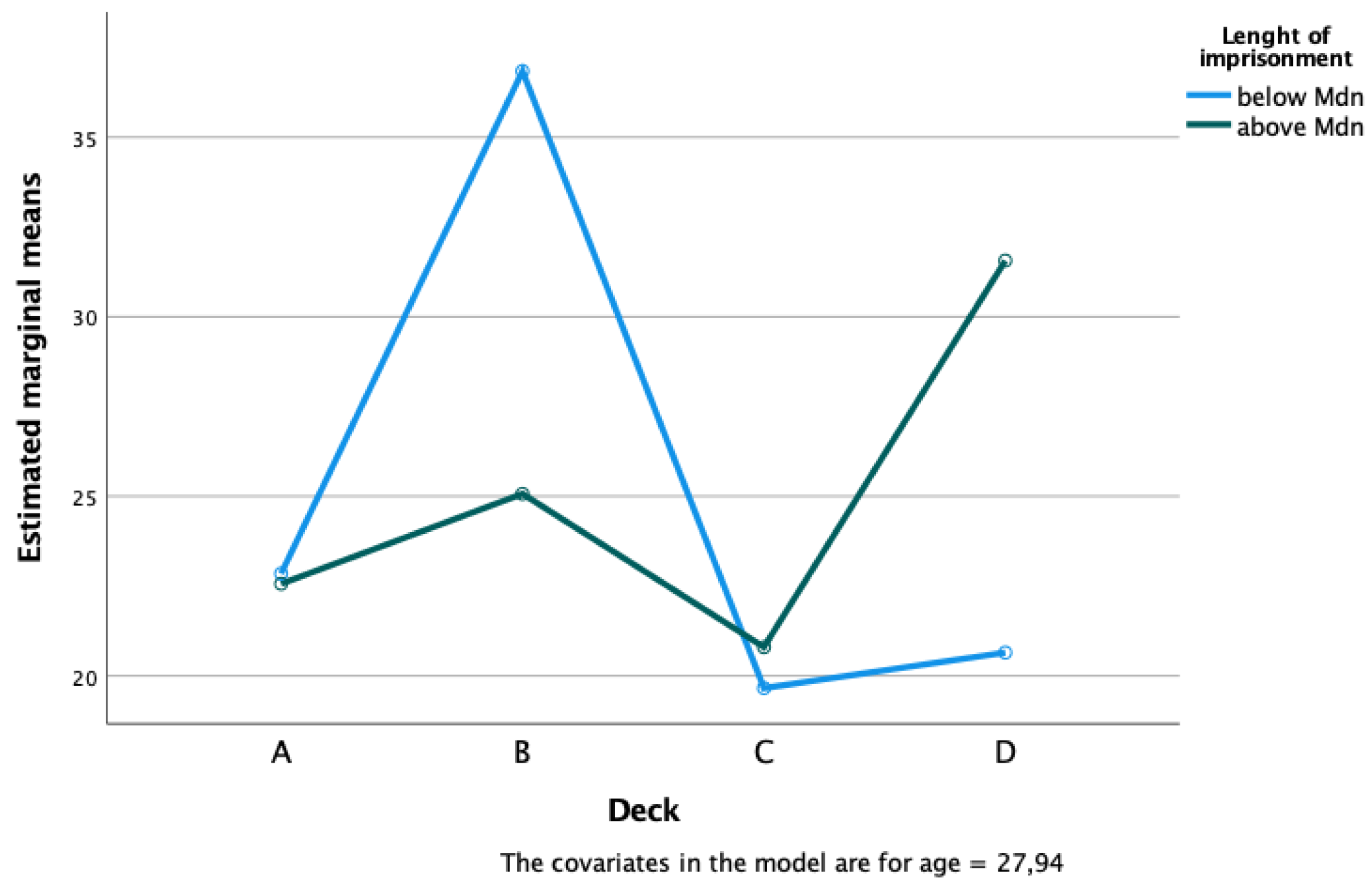

Regarding the Deck variable, the ANOVA involved the within-subjects factor Deck with 4 levels (Deck A vs. Deck B vs. Deck C vs. Deck D). Similar to the Net variable analysis, Length of Imprisonment was treated as a fixed factor, and age was used as a covariate. This analysis revealed a trend toward significance for the interaction between Deck and Length of Imprisonment (F(3, 45) = 2.268; p = 0.093). Subsequent analysis of simple main effects indicated that individuals with less imprisonment time showed a higher number of cards picked for deck B compared to decks A and C revealing poorer decision-making ability in these individuals (see

Figure 2).

4. Discussion

Executive dysfunction is considered one of the main predictors of criminal behavior. Generally, individuals in a situation of seclusion demonstrate deficits in cognitive, social, and emotional skills (Altikriti, 2020; Ogilvie et al., 2011) and executive functioning (Seruca & Silva, 2016). This pattern of deficits has been previously associated with the severity of criminal behavior (Ross & Hoaken, 2011; Valliant et al., 2003).

This study aimed to evaluate and characterize the cognitive functioning of imprisoned individuals, according to the severity of criminal behavior. In our study, we have used the duration of sentence imposed as a proxy measure of the severity of criminal behavior. Therefore, it was hypothesized that individuals with longer sentences associated, and more violent crimes would have greater executive deficits, as well as take greater risks in decision-making, compared to individuals with more reduced sentences and less violent crimes.

To explore whether the prison environment impacts executive functions (Meijers et al., 2018) we have chosen to study the effect of the length of imprisonment duration in executive functions and decision-making. It was also hypothesized that individuals with longer periods of imprisonment would have greater executive deficits, as well as poorer decision-making because of the prison environment characterized as impoverished and sedentary (Meijers et al., 2015).

The results were first explored to test the relationship between age and education with the independent variables. Numerous other factors can contribute to this decline, such as substance use, mental disorders or low educational levels (Combalbert & Pennequin, 2020; Meijers et al., 2017; Ross & Hoaken, 2011; Tuominen et al., 2017; Verhülsdonk et al., 2021). In our study, we only found an association with age. Given that age was shown to be associated with both sentence imposed and imprisonment period and given that age also explains neurocognitive functioning, we have controlled age in these analyses. Individuals with longer sentences or those with longer periods of imprisonment were older. Therefore, age was controlled in all statistical procedures.

The results from global cognitive functioning and executive functions performance did not suggest marked impairments in individuals in prison. The results demonstrate that, from a global point of view, the performance of those individuals is not below the normative data for each of the tests related to global cognitive functioning and executive functions.

Previous studies have found that offenders who perpetrate violent crimes or repeat offenders tend to have greater difficulties at the level of executive functions, given their greater cognitive rigidity; this is because they may have greater difficulties in terms of learning new behavioral rules, as well as in the use of external references, to plan, monitor, regulate and adapt their behavior to new situations (Barbosa & Monteiro, 2008). In our study, we have found this for individuals with longer sentences imposed. We found an effect of the sentence imposed in executive functions, and specifically, on mental flexibility and sensitivity to interference. Mental flexibility and sensitivity to interference are core domains of executive functions that may have significant impacts on monitoring behavior and self-regulation (Hofmann et al., 2012). These results are partially aligned with prior literature revealing that offenders perform worse on measures of mental flexibility and planning than non-offenders (Seruca & Silva, 2016); the authors also found a stronger correlation between sensitivity resistance and anger. These results are also aligned with our data suggesting that sensitivity to interference may be a marker of executive dysfunction in inmate population.

Despite these findings, no effects were found in the WCST. The absence of results is intriguing. The WCST is a measure of set-shifting, a domain of executive functions (Diamond, 2013) that relates to mental flexibility. According to Funahashi (2001), the ability to shift attention to a given stimulus and keep it in working memory is necessary to perform the WCST test, and this ability may be related to the inhibition of behavioral responses to inappropriate stimuli. It is possible that the deficits of the inmate population with higher severity sentences were mostly captured by verbal fluency instead of the performance in the set-shifting measures of cognitive flexibility as the WCST.

As mentioned, working memory is equally important and necessary in the WCST test, as it allows, together with the attentional shift between stimuli, the modification of behaviors. This cognitive domain concerns the ability to temporarily store and process relevant information during the execution of a task (Funahashi, 2001). Therefore, it enables the resolution of problems and the directing of behaviors towards certain objectives, through access to previously acquired learning and the acquisition of new ones (Funahashi, 2001). At the level of working memory, we also did not find effects of the sentence imposed. Probably the deficits found in the literature on working memory (e.g., Sánchez de Ribera et al., 2021) need to be confirmed in other tasks as n-back tasks, as they simultaneously require maintenance and manipulation of information (Gajewski et al., 2018).

The prison context can also lead to a decrease in cognitive abilities in older individuals, even proposing a greater risk of developing neurodegenerative diseases such as dementia. This is because it is a context considered to promote a sedentary lifestyle, with little social interaction and low cognitive stimulation (Combalbert & Pennequin, 2020; Meijers et al., 2017; Verhülsdonk et al., 2021). For example, the literature has shown that brain processes involved in self-regulation (i.e., self-control and planning) and attention are reduced after three months of confinement, suggesting that this difficulty may lead to a higher risk of recidivism (Ligthart et al., 2019; Meijers et al., 2018).

We have used the length of the imprisonment period to study whether staying in a prison context would impact executive functions and decision-making. Within the Criminal Records group, about the results obtained in the IGT, there was some inconsistency in the pattern of behavior adopted throughout the task. Although, in general, the choice of disadvantageous decks was made mainly by the subgroup of repeat offenders, it was found that one of the disadvantageous decks (Deck A) was chosen more by the subset of primary offenders. This inconsistency may have resulted from a lack of motivation on the part of the participants in performing the task, which may have led to random responses, or it may be associated with some difficulty in maintaining the memory of the rules of the game, although they initially perceived them. On the other hand, in the Types of Crime group, the results are consistent in all the variables analyzed in the IGT in relation to the subgroup of individuals considered non-violent, thus indicating a greater tendency to choose disadvantageous decks and, consequently, a more significant risk in decision-making. When this subgroup was analyzed, it was found that the four participants considered non-violent were also in primary seclusion (also, the reduced number of participants in the sub-group make the current results to be discussed with caution). However, this information is in line with what has already been reported, in which primary offenders tend to have greater deficits in deferring gratification (Seruca & Silva, 2015). However, other studies point to opposite results. For example, in a systematic review of impulsive control among individuals in seclusion, there was a pronounced deficit in the control of impulsivity in decision-making, particularly in individuals considered violent, exhibiting greater difficulties in delaying gratification and in the ability to inhibit inappropriate and impulsive responses. Moreover, these difficulties can also be predictors of criminal recidivism (Vedelago et al., 2019)."

Perhaps, a more structured environment with physical activity may help to improve pre-frontal functioning and decision-making. Other factors might compromise decision-making, such as substance use which was tested but revealed no effect on the independent variables. Nevertheless, it should be noted that six of the eight participants in the subgroup of repeat offenders had a history of substance use. However, due to the unbalance between this variable and the small sample size, this effect was not tested in the neuropsychological data.

As for the limitations, the main was the small sample size, which makes it impossible to understand whether there are significant differences between the groups, concerning cognitive functioning, or whether these results are dependent on other variables. For example, the sample comprised recidivists and primary offenders, and violent and non-violent individuals, however, primary offenders were also more violent, so the results may be inconsistent with the hypothesis. On the other hand, to understand whether the executive functions exert an effect, mediator or moderator analysis should be run on the variables of length of imprisonment and degree of severity of criminal acts. Another issue that would be interesting to see clarified concerns the results found in the FAB, more precisely in the inhibitory control task, within the Criminal Record group, because individuals in situations of recidivism presented superior performances compared to primary individuals.

It would have been important to assess inhibitory skills using the Stroop test. One of the factors that can also explain lower performance in complex neuropsychological tasks is intelligence (Ross & Hoaken, 2011), thus, in future studies, it would be important to use measures that allow evaluating and controlling the impact of intelligence on cognitive decline. Alongside, the use of a more comprehensive battery of tests, consisting not only of tests that assess cold executive functions but also hot ones, at the same time with complementary tests of brain functioning, would be helpful. From a neuroanatomical point of view, these functions are associated with different brain areas, although they operate together in a coordinated system (Zelazo & Carlson, 2012). Finally, it would be important to understand the predominant pattern of aggressiveness in the sample, whether it is a reactive type of aggression that is manifested by impulsivity, or an instrumental type of aggression that is characterized by premeditated and planned behaviors, considering that the two demonstrate distinct associations with different cognitive deficits (Broomhall, 2005).

Understanding the cognitive functioning of individuals in prison, specifically the deficits they present, is vital for their monitoring and rehabilitation, especially in cases of criminal recidivism (Ross & Hoaken, 2011). Moreover, this analysis must include an integrative and multidisciplinary approach, as several factors contribute to cognitive and executive impairment and the involvement of these individuals with the justice system (Sullivan, 2019).

Supplementary Materials

None.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.O., P.G. and J.C.; methodology, J.O, P.G. and J.C..; formal analysis, I.G., J.O.; investigation, I.M. and J.C.; data curation, J.O.; writing—original draft preparation, I.G., J.O. and A.R.C.; writing—review and editing, P.G., J.C.; visualization, J.O.; supervision, J.O., P.G. and J.C.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by the Foundation for Science and Technology – FCT (Portuguese Ministry of Science, Technology and Higher Education), under the grant UIDB/05380/2020.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of CEDIC - Committee on Ethics and Deontology of Scientific Research (reference CEDIC-2025-2-30, date of approval May 28, 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data used for this study is available upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| APA |

American Psychological Association |

| ANOVA |

Analysis of Variance |

| CEDIC |

Committee on Ethics and Deontology of Scientific Research |

| CI |

Confidence Interval |

| DGRSP |

General Directorate for Reinsertion and Prison Services |

| DSM 5 |

Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders 5 |

| FAB |

Frontal Assessment Battery |

| IGT |

Iowa Gambling Task |

| M |

Mean |

| Mdn |

Median |

| MoCA |

Montreal Cognitive Assessment |

| OECD |

Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development |

| SD |

Standard Deviation |

| WAIS |

Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale |

| WCST |

Wisconsin Card Sorting Test |

References

- Altikriti, S. (2020). Toward Integrated Processual Theories of Crime: Assessing the Developmental Effects of Executive Function, Self-Control, and Decision-Making on Offending. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 48(2), 215–233. [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association (2014). DSM-V: Manual de Diagnóstico e Estatística das Perturbações Mentais (5ª ed.). Lisboa. Climepsi Editores.

- Angrilli, A., Sartori, G., & Donzella, G. (2013). Cognitive, Emotional and Social Markers of Serial Murdering. The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 27(3), 485–494. [CrossRef]

- Ardila, A. (2013). There are Two Different Dysexecutive Syndromes. Journal of Neurological Disorders, 1(1). [CrossRef]

- Areias, G., Paixão, R., & Figueira, A. P. C. (2013). O Iowa Gambling Task: uma revisão crítica. Psicologia: Teoria e Pesquisa, 29(2), 201–210. [CrossRef]

- Balafoutas, L., García-Gallego, A., Georgantzis, N., Jaber-Lopez, T., & Mitrokostas, E. (2020). Rehabilitation and social behavior: Experiments in prison. Games and Economic Behavior, 119, 148–171. [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, M., & Monteiro, L. (2008). Recurrent criminal behavior and executive dysfunction. Recurrent Criminal Behavior and Executive Dysfunction, 11(1), 259–265. [CrossRef]

- Bechara, A. (2005). Decision making, impulse control and loss of willpower to resist drugs: a neurocognitive perspective. Nature Neuroscience, 8(11), 1458–1463. [CrossRef]

- Bechara, A., Damasio, A. R., Damasio, H., & Anderson, S. W. (1994). Insensitivity to future consequences following damage to human prefrontal cortex. Cognition, 50(1–3), 7–15. [CrossRef]

- Bergeron, T. K., & Valliant, P. M. (2001). Executive function and personality in adolescent and adult offenders vs. non-offenders. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation, 33(3), 27–45. [CrossRef]

- Braga, T., Gonçalves, L. C., Basto-Pereira, M., & Maia, Â. (2017). Unraveling the link between maltreatment and juvenile antisocial behavior: A meta-analysis of prospective longitudinal studies. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 33, 37–50. [CrossRef]

- Broomhall, L. (2005). Acquired sociopathy: A neuropsychological study of executive dysfunction in violent offenders. Psychiatry, Psychology and Law, 12(2), 367–387. [CrossRef]

- Brower, M. C., & Price, B. H. (2001). Neuropsychiatry of frontal lobe dysfunction in violent and criminal behaviour: A critical review. Journal of Neurology Neurosurgery and Psychiatry, 71(6), 720–726. [CrossRef]

- Burgess, J. (2020). A brief review of the relationship of executive function assessment and violence. In Aggression and Violent Behavior, 54. [CrossRef]

- Chandler, M. J. (1973). Egocentrism and antisocial behavior: The assessment and training of social perspective-taking skills. Developmental Psychology, 9(3), 326–332. [CrossRef]

- Combalbert, N., & Pennequin, V. (2020). Effect of age and time spent in prison on the mental health of elderly prisoners. Annales Medico-Psychologiques, 178(3), 264–270. [CrossRef]

- Cruz, A. R., de Castro-Rodrigues, A., & Barbosa, F. (2020). Reprint of “Executive dysfunction, violence and aggression.” Aggression and Violent Behavior, 54(March), 101404. [CrossRef]

- De Brito, S. A., Viding, E., Kumari, V., Blackwood, N., & Hodgins, S. (2013). Cool and Hot Executive Function Impairments in Violent Offenders with Antisocial Personality Disorder with and without Psychopathy. PLoS ONE, 8(6), e65566. [CrossRef]

- Derzon, J. H. (2010). The correspondence of family features with problem, aggressive, criminal, and violent behavior: A meta-analysis. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 6(3), 263–292. [CrossRef]

- Diamond, A. (2013). Executive functions. Annual Review of Psychology, 64, 135–168. [CrossRef]

- Direção Geral de Reinserção e Serviços Prisionais (2022, Dezembro). Lotação e reclusos existentes em 31 de dezembro. https://dgrsp.justica.gov.pt/Portals/16/Estatisticas/%C3%81rea%20Prisional/Anuais/2022/Q-03-Rcls.pdf?ver=DfvcYTHi3B_jrVnMZ_4JYA%3d%3d.

- Direção Geral de Reinserção e Serviços Prisionais (2022, Dezembro). Reclusos condenados existentes em 31 de dezembro, segundo as penas e medidas aplicadas, por sexo e nacionalidade. https://dgrsp.justica.gov.pt/Portals/16/Estatisticas/%C3%81rea%20Prisional/Anuais/2022/Q-07-Rcls.pdf?ver=aH09F-_bQXmbTHgEM7n9Kw%3d%3d.

- Direção Geral de Reinserção e Serviços Prisionais (2019, Dezembro). Reclusos condenados existentes em 31 de dezembro, segundo o sexo, os escalões de idade e a nacionalidade, por crimes. https://dgrsp.justica.gov.pt/Portals/16/Estatisticas/%C3%81rea%20Prisional/Anuais/2022/Q-09-Rcls.pdf?ver=C1BkIB43zBUYAiyr0SFOAA%3d%3d.

- Dubois, B., Slachevsky, A., Litvan, I., & Pillon, B. (2000). The FAB: A frontal assessment battery at bedside. Neurology, 55(11), 1621–1626. [CrossRef]

- Edge, D., Thomas, A., Antony, C., C., D., & Thomas, D. (2020). Crime. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/crime-law.

- Fazel, S., & Wolf, A. (2015). A systematic review of criminal recidivism rates worldwide: Current difficulties and recommendations for best practice. PLoS ONE, 10(6), 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Freitas, S., Simões, M. R., Alves, L., & Santana, I. (2011). Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA): Normative study for the Portuguese population. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology, 33(9), 989–996. [CrossRef]

- Funahashi, S. (2001). Neuronal mechanisms of executive control by the prefrontal cortex. Neuroscience Research, 39(2), 147–165. [CrossRef]

- Gajewski, P. D., Hanisch, E., Falkenstein, M., Thönes, S., & Wascher, E. (2018). What Does the n-Back Task Measure as We Get Older? Relations Between Working-Memory Measures and Other Cognitive Functions Across the Lifespan. Frontiers in Psychology, 9(NOV), 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Hancock, M., Tapscott, J. L., & Hoaken, P. N. S. (2010). Role of executive dysfunction in predicting frequency and severity of violence. Aggressive Behavior, 36(5), 338–349. [CrossRef]

- Heaton, R., Chelune, G., Talley, J., Kay, G., & Curtiss, G. (2005). Manual do Teste Wisconsin de Classificação de Cartas. Adaptação e padronização brasileira (I. B. . Guntert & S. D. Tosi (eds.); 1a Edição. Casa do Psicólogo.

- Hofmann, W., Schmeichel, B. J., and Baddeley, A. D. (2012). Executive functions and self-regulation. Trends Cog. Sci. 16, 174–180. [CrossRef]

- Kelly, T., Richardson, G., Hunter, R., & Knapp, M. (2002). Attention and Executive Function Deficits in Adolescent Sex Offenders. Child Neuropsychology, 8(2), 138–143. [CrossRef]

- Kuin, N. C., de Vries, J., Scherder, E. J. A., van Pelt, J., & Masthoff, E. D. M. (2019). Cool and Hot Executive Functions in Relation to Aggression and Testosterone/Cortisol Ratios in Male Prisoners. In Annals of Behavioral Neuroscience (206–222). [CrossRef]

- Ligthart, S., van Oploo, L., Meijers, J., Meynen, G., & Kooijmans, T. (2019). Prison and the brain: Neuropsychological research in the light of the European Convention on Human Rights. New Journal of European Criminal Law, 10(3), 287–300. [CrossRef]

- Márquez, M., Salguero Alcañiz, M., Paíno Quesada, S., & Alameda Bailén, J. (2013). La hipótesis del Marcador Somático y su nivel de incidencia en el proceso de toma de decisiones. Rema, 18(1), 17–36. [CrossRef]

- Meijers, J., Harte, J. M., Meynen, G., & Cuijpers, P. (2017). Differences in executive functioning between violent and non-violent offenders. Psychological Medicine, 47(10), 1784–1793. [CrossRef]

- Meijers, Jesse, Harte, J. M., Jonker, F. A., & Meynen, G. (2015). Prison brain? Executive dysfunction in prisoners. Frontiers in Psychology, 6(JAN), 2–7. [CrossRef]

- Meijers, Jesse, Harte, J. M., Meynen, G., Cuijpers, P., & Scherder, E. J. A. (2018). Reduced self-control after 3 months of imprisonment; A pilot study. Frontiers in Psychology, 9(FEB), 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Miyake, A., Friedman, N. P., Emerson, M. J., Witzki, A. H., Howerter, A., & Wager, T. D. (2000). The Unity and Diversity of Executive Functions and Their Contributions to Complex “Frontal Lobe” Tasks: A Latent Variable Analysis. Cognitive Psychology, 41(1), 49–100. [CrossRef]

- Morgan, A. B., & Lilienfeld, S. O. (2000). A meta-analytic review of the relation between antisocial behavior and neuropsychological measures of executive function. Clinical Psychology Review, 20(1), 113–136. [CrossRef]

- Ogilvie, J. M., Stewart, A. L., Chan, R. K., & Shum, D. H. K. (2011). Neuropsychological Measures Of Executive Function And Antisocial Behavior: A Meta-Analysis*. Criminology, 49(4), 1063–1107. [CrossRef]

- Organização para a Cooperação e Desenvolvimento Económico (2020, Maio). Incarceration rates in OECD countries as of May 2020. https://www.statista.com/statistics/300986/incarceration-rates-in-oecd-countries/.

- Reddy, K. J., Menon, K. R., & Hunjan, U. G. (2018). Neurobiological aspects of violent and criminal behaviour: Deficits in frontal lobe function and neurotransmitters. International Journal of Criminal Justice Sciences, 13(1), 44–54. [CrossRef]

- Ross, E. H., & Hoaken, P. N. S. (2011). Executive cognitive functioning abilities of male first time and return Canadian federal inmates. In Canadian Journal of Criminology and Criminal Justice, 53(4), 377–403). [CrossRef]

- Sánchez de Ribera, O., Trajtenberg, N., & Cook, S. (2021). Executive functioning among first time and recidivist inmates in Uruguay. Applied Neuropsychology: Adult, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Seruca, T., & Silva, C. F. (2015). Recidivist criminal behaviour and executive functions: a comparative study. In Journal of Forensic Psychiatry and Psychology, 26(5), 699–717. [CrossRef]

- Seruca, T., & Silva, C. F. (2016). Executive Functioning in Criminal Behavior: Differentiating between Types of Crime and Exploring the Relation between Shifting, Inhibition, and Anger. In International Journal of Forensic Mental Health, 15(3), 235–246. [CrossRef]

- Shumlich, E. J., Reid, G. J., Hancock, M., & N. S. Hoaken, P. (2019). Executive Dysfunction in Criminal Populations: Comparing Forensic Psychiatric Patients and Correctional Offenders. International Journal of Forensic Mental Health, 18(3), 243–259. [CrossRef]

- Slaby, R. G., & Guerra, N. G. (1988). Cognitive Mediators of Aggression in Adolescent Offenders: 1. Assessment. Developmental Psychology, 24(4), 580–588. [CrossRef]

- Sreenivasan, S., Walker, S. C., Weinberger, L. E., Kirkish, P., & Garrick, T. (2008). Four-Facet PCL–R Structure and Cognitive Functioning Among High Violent Criminal Offenders. Journal of Personality Assessment, 90(2), 197–200. [CrossRef]

- Stanley, J., & Goddard, C. (2004). Multiple forms of violence and other criminal activities as an indicator of severe child maltreatment. Child Abuse Review, 13(4), 246–262. [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, J. A. (2019). Achieving cumulative progress in understanding crime: some insights from the philosophy of science. In Psychology, Crime & Law, 25(6), 561–576. [CrossRef]

- Tirapu-Ustárroz, J., García-Molina, a, Luna Lario, P., Verdejo García, a, & Ríos Lago, M. (2012). Funciones ejecutivas y regulación de la conducta. Neuropsicología de La Corteza Prefrontal y Las Funciones Ejecutivas, 89–120. http://autismodiario.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/Neuropsicolog?a-de-la-corteza-prefrontal-y-las-funciones-ejecutivas-y-Conducta.pdf.

- Tsermentseli, S., & Poland, S. (2016). Cool versus hot executive function: A new approach to executive function. Encephalos, 53(1), 11–14.

- Tuominen, T., Korhonen, T., Hämäläinen, H., Katajisto, J., Vartiainen, H., Joukamaa, M., Lintonen, T., Wuolijoki, T., Jüriloo, A., & Lauerma, H. (2017). The factors associated with criminal recidivism in Finnish male offenders: importance of neurocognitive deficits and substance dependence. Journal of Scandinavian Studies in Criminology and Crime Prevention, 18(1), 52–67. [CrossRef]

- Valliant, P. M., Freeston, A., Pottier, D., & Kosmyna, R. (2003). Personality and Executive Functioning as Risk Factors in Recidivists. Psychological Reports, 92(1997), 299–306.

- Vedelago, L., Amlung, M., Morris, V., Petker, T., Balodis, I., McLachlan, K., Mamak, M., Moulden, H., Chaimowitz, G., & MacKillop, J. (2019). Technological advances in the assessment of impulse control in offenders: A systematic review. Behavioral Sciences & the Law, 37(4), 435–451. [CrossRef]

- Veneziano, C., & Veneziano, L. (2004). Neuropsychological executive functions of adolescent sex offenders and nonsex offenders. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 98, 661–674. [CrossRef]

- Verdejo, A., & Bechara, A. (2010). Neuropsicología de las funciones ejecutivas. Psicothema, 22(2), 227–235.

- Verhülsdonk, S., Folkerts, A.-K., Höft, B., Supprian, T., Kessler, J., & Kalbe, E. (2021). Cognitive dysfunction in older prisoners in Germany: a cross-sectional pilot study. International Journal of Prisoner Health, 17(2), 111–127. [CrossRef]

- Wallinius, M., Nordholm, J., Wagnström, F., & Billstedt, E. (2019). Cognitive functioning and aggressive antisocial behaviors in young violent offenders. Psychiatry Research, 272(June 2018), 572–580. [CrossRef]

- Wechsler, D. (2008). Escala de Inteligência de Wechsler para Adultos (3.a edição: Manual) [Wechsler adult intelligence scale (3rd ed. Manual)]. Lisbon, Portugal: CEGOC-TEA.

- Yechiam, E., Kanz, J. E., Bechara, A., Stout, J. C., Busemeyer, J. R., Altmaier, E. M., & Paulsen, J. S. (2008). Neurocognitive deficits related to poor decision making in people behind bars. Psychonomic Bulletin and Review, 15(1), 44–51. [CrossRef]

- Zelazo, P. D., & Carlson, S. M. (2012). Hot and Cool Executive Function in Childhood and Adolescence: Development and Plasticity. Child Development Perspectives, 6(4). [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).