Submitted:

20 October 2025

Posted:

21 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Source Data

2.2. Generalized Additive Models for Vaccination Impact Assessment

2.3. Time Series Analysis of Epidemiological Indicators

2.4. Genomic Analysis

2.5. Phylogenetic Analysis

3. Results

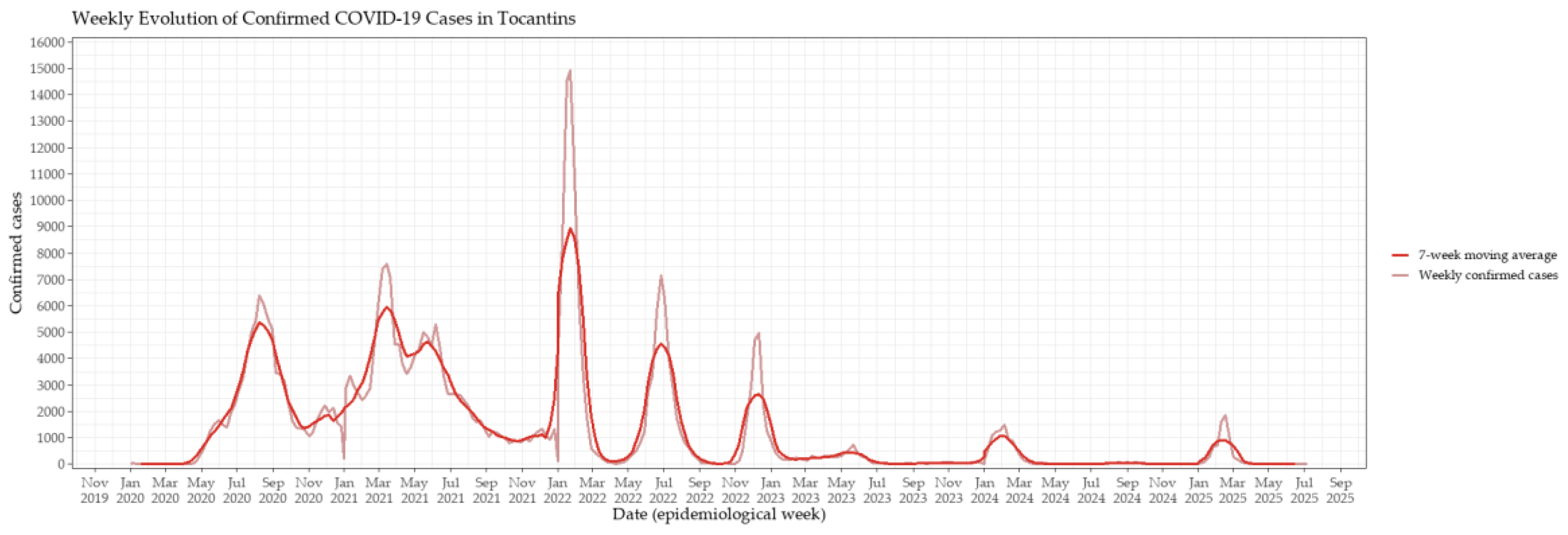

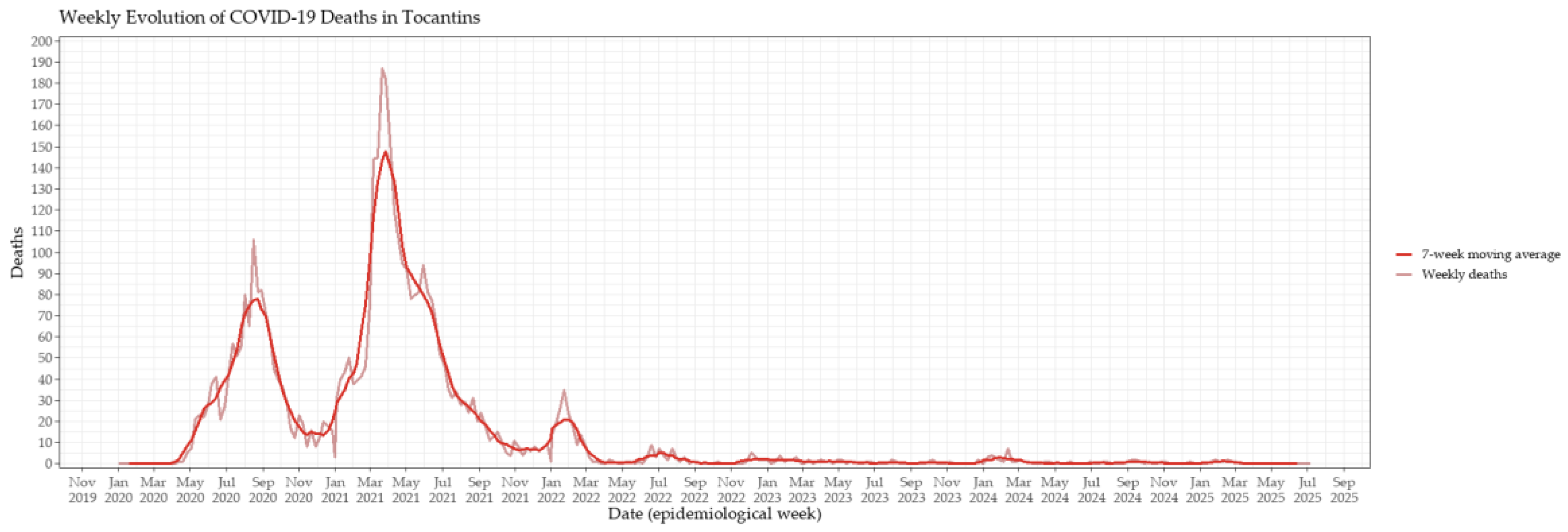

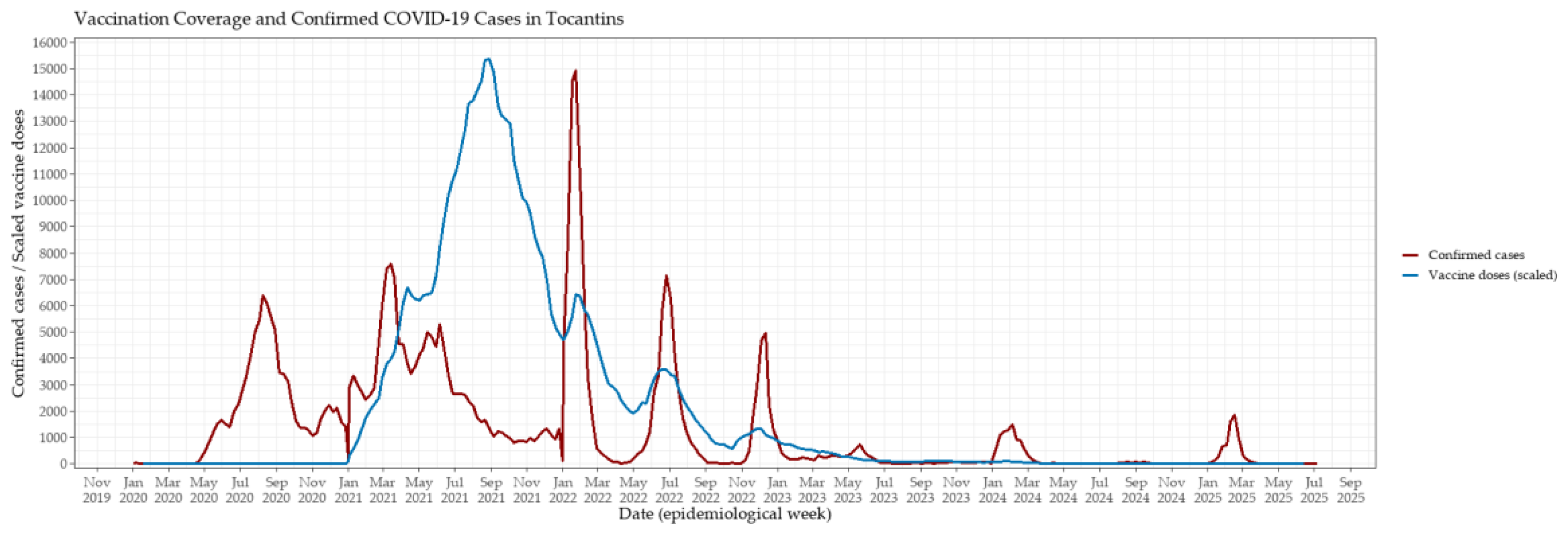

3.1. Epidemic Dynamics and Vaccination Rollout in Tocantins

3.2. Comparative Analysis Across Vaccination Phases

3.3. Nonlinear Effects of Vaccination Modeled Using GAMs

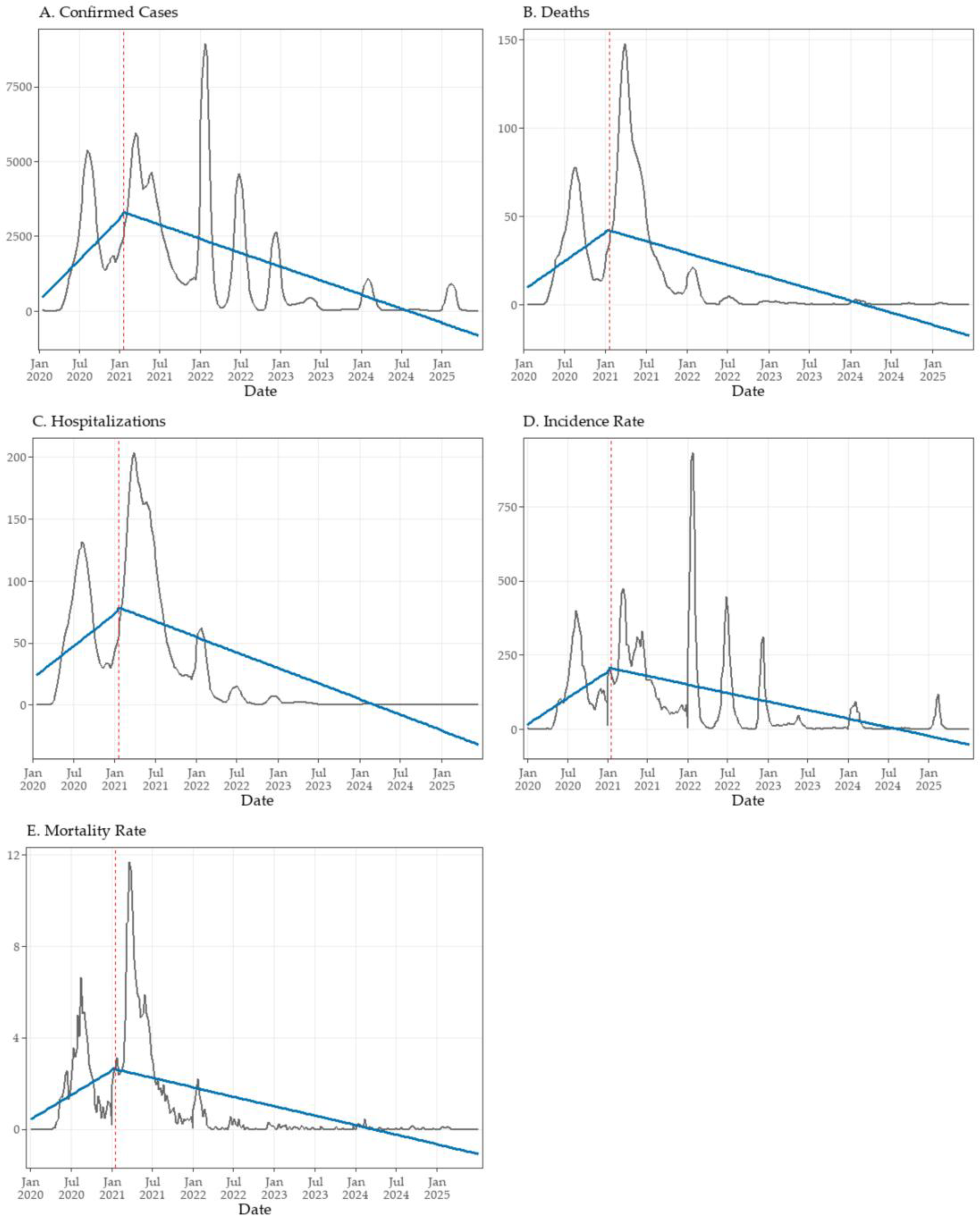

3.4. Interrupted Time Series Analysis of Vaccination Impact

3.5. Temporal Decomposition of Epidemiological Indicators (STL Analysis)

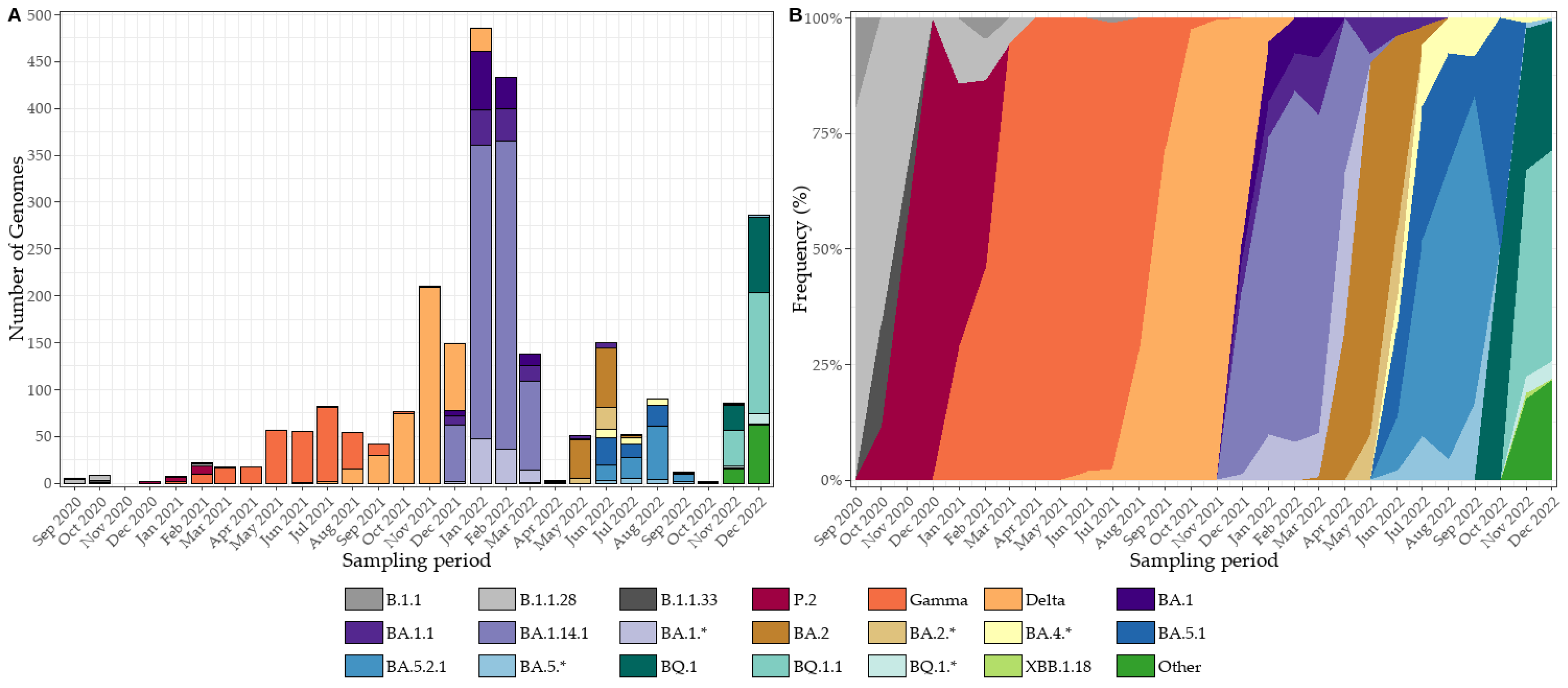

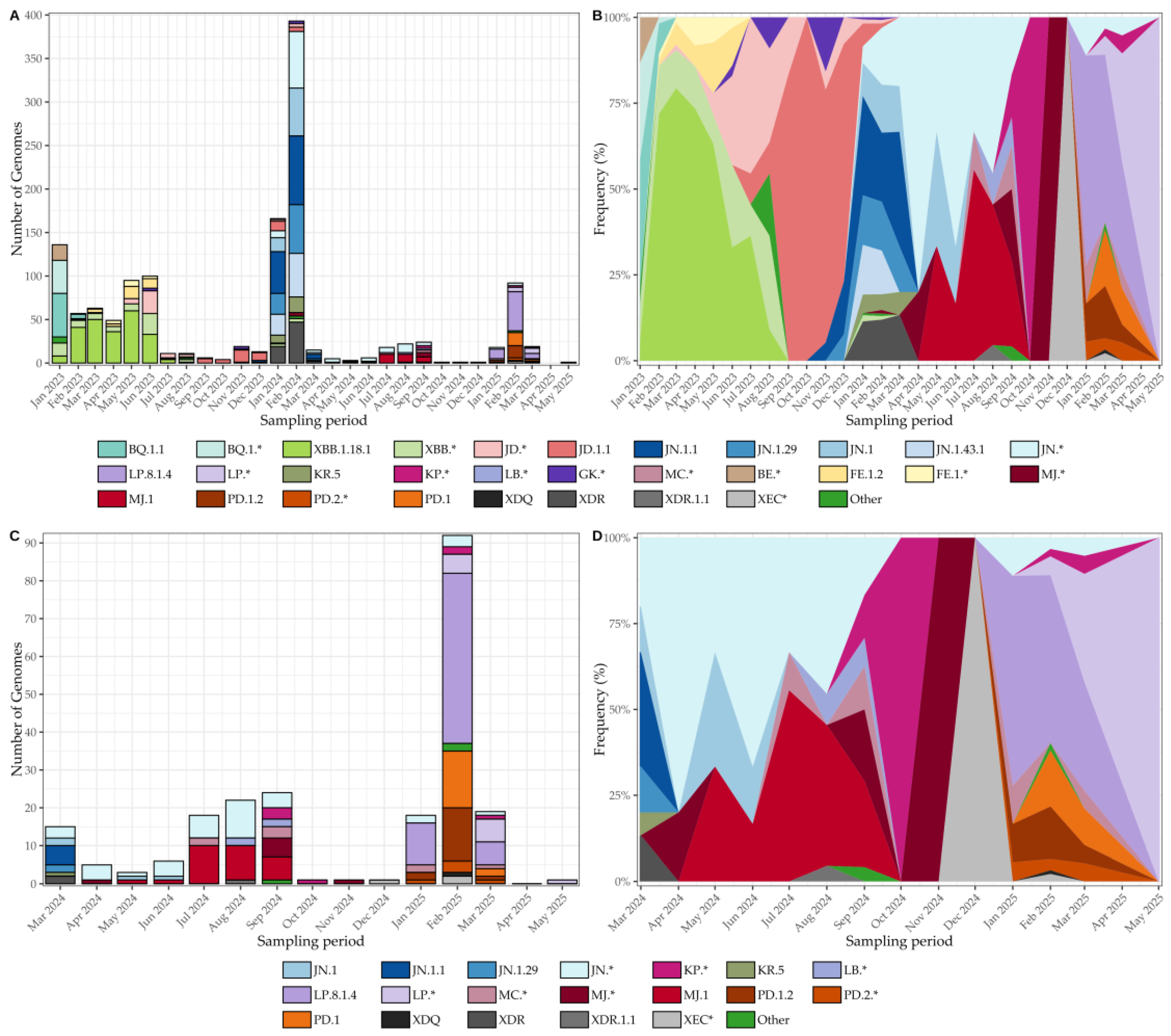

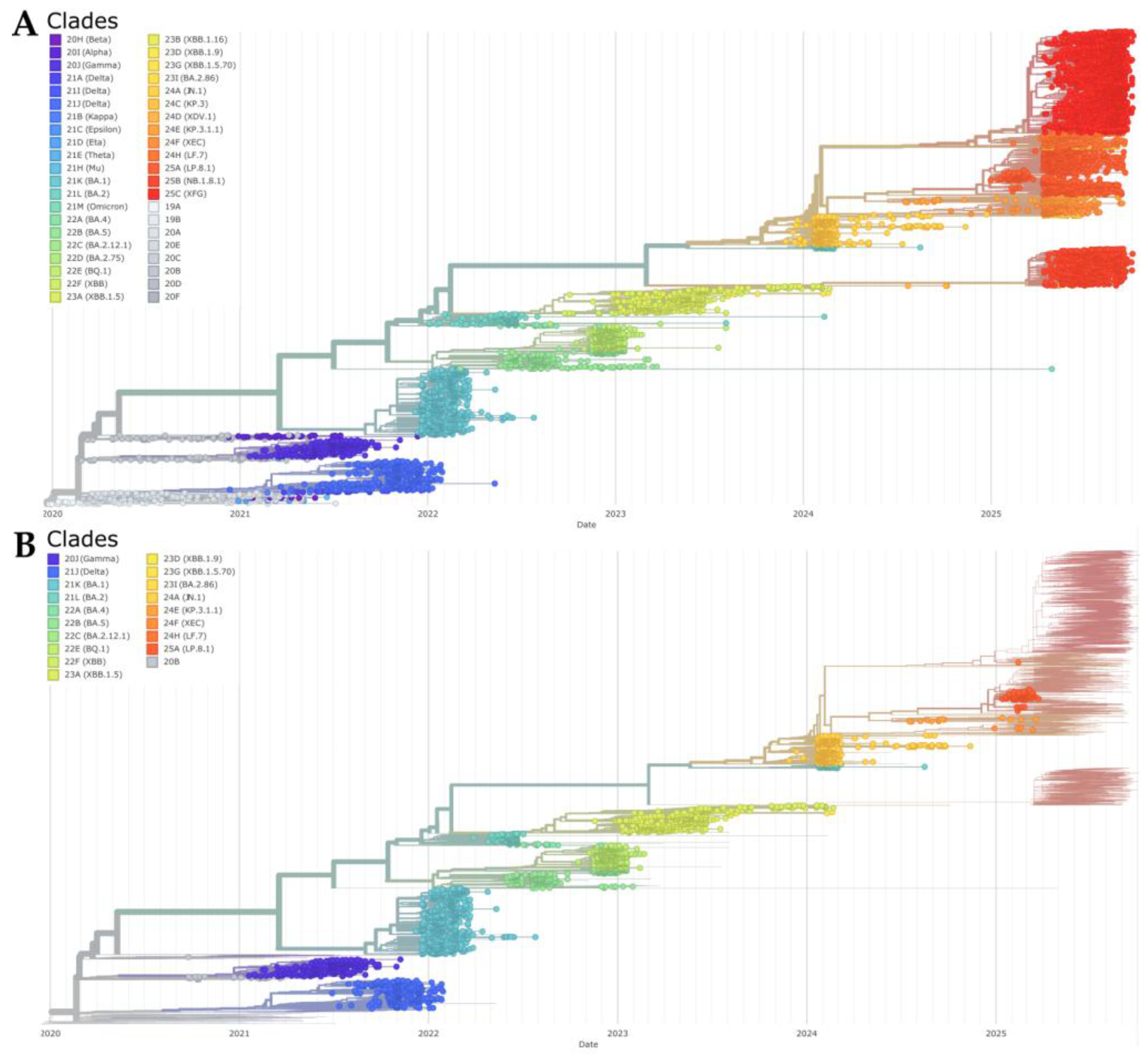

3.6. SARS-CoV-2 Genomic Surveillance and Lineage Dynamics

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

References

- Singh, D.; Yi, S. V. On the Origin and Evolution of SARS-CoV-2. Exp Mol Med 2021, 53, 537–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO) Statement on the Fifteenth Meeting of the IHR (2005) Emergency Committee on the COVID-19 Pandemic. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/05-05-2023-statement-on-the-fifteenth-meeting-of-the-international-health-regulations-(2005)-emergency-committee-regarding-the-coronavirus-disease-(covid-19)-pandemic (accessed on 21 August 2025).

- Oliveira, W.K. de; Duarte, E.; França, G.V.A. de; Garcia, L.P. Como o Brasil Pode Deter a COVID-19. Epidemiologia e Serviços de Saúde 2020, 29, e2020044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bessa, K.; Alves da Luz, R. A Pandemia de Covid-19 e as Particularidades Regionais Da Sua Difusão No Segmento de Rede Urbana No Estado Do Tocantins, Brasil. Ateliê Geográfico 2020, 14, 6–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, W.T.; Carabelli, A.M.; Jackson, B.; Gupta, R.K.; Thomson, E.C.; Harrison, E.M.; Ludden, C.; Reeve, R.; Rambaut, A.; Peacock, S.J.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 Variants, Spike Mutations and Immune Escape. Nat Rev Microbiol 2021, 19, 409–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moeller, N.H.; Shi, K.; Demir, Ö.; Belica, C.; Banerjee, S.; Yin, L.; Durfee, C.; Amaro, R.E.; Aihara, H. Structure and Dynamics of SARS-CoV-2 Proofreading Exoribonuclease ExoN. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2022, 119, e2106379119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peacock, T.P.; Penrice-Randal, R.; Hiscox, J.A.; Barclay, W.S. SARS-CoV-2 One Year on: Evidence for Ongoing Viral Adaptation. Journal of General Virology 2021, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Lai, S.; Gao, G.F.; Shi, W. The Emergence, Genomic Diversity and Global Spread of SARS-CoV-2. Nature 2021, 600, 408–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salzberger, B.; Buder, F.; Lampl, B.; Ehrenstein, B.; Hitzenbichler, F.; Holzmann, T.; Schmidt, B.; Hanses, F. Epidemiology of SARS-CoV-2. Infection 2021, 49, 233–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, U.J.B. de; Spilki, F.R.; Tanuri, A.; Roehe, P.M.; Campos, F.S. Two Years of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron Genomic Evolution in Brazil (2022–2024): Subvariant Tracking and Assessment of Regional Sequencing Efforts. Viruses 2025, 17, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michelon, C.M. Main SARS-CoV-2 Variants Notified in Brazil. Revista Brasileira de Análises Clínicas 2021, 53, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamarca, A.P.; Souza, U.J.B. de; Moreira, F.R.R.; Almeida, L.G.P. de; Menezes, M.T. de; Souza, A.B. de; Ferreira, A.C.d.S.; Gerber, A.L.; Lima, A.B. de; Guimarães, A.P. de C.; et al. The Omicron Lineages BA.1 and BA.2 (Betacoronavirus SARS-CoV-2) Have Repeatedly Entered Brazil through a Single Dispersal Hub. Viruses 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giovanetti, M.; Fonseca, V.; Wilkinson, E.; Tegally, H.; San, E.J.; Althaus, C.L.; Xavier, J.; Nanev Slavov, S.; Viala, V.L.; Ranieri Jerônimo Lima, A.; et al. Replacement of the Gamma by the Delta Variant in Brazil: Impact of Lineage Displacement on the Ongoing Pandemic. Virus Evol 2022, 8, veac024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alcantara, L.C.J.; Nogueira, E.; Shuab, G.; Tosta, S.; Fristch, H.; Pimentel, V.; Souza-Neto, J.A.; Coutinho, L.L.; Fukumasu, H.; Sampaio, S.C.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 Epidemic in Brazil: How the Displacement of Variants Has Driven Distinct Epidemic Waves. Virus Res 2022, 315, 198785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arantes, I.; Gomes Naveca, F.; Gräf, T.; Miyajima, F.; Faoro, H.; Luz Wallau, G.; Delatorre, E.; Reis Appolinario, L.; Cavalcante Pereira, E.; Venas, T.M.M.; et al. Emergence and Spread of the SARS-CoV-2 Variant of Concern Delta across Different Brazilian Regions. Microbiol Spectr 2022, 10, e02641–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomes, B.B.M.; Ferreira, N.N.; Garibaldi, P.M.M.; Dias, C.F.S. de L.; Silva, L.N.; Almeida, M.A.A.L. dos S.; de Moraes, G.R.; Covas, D.T.; Kashima, S.; Calado, R.T.; et al. Impact of SARS-CoV-2 Variants on COVID-19 Symptomatology and Severity during Five Waves. Heliyon 2024, 10, e40113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza, U.J.B.; dos Santos, R.N.; Campos, F.S.; Lourenço, K.L.; da Fonseca, F.G.; Spilki, F.R. High Rate of Mutational Events in SARS-CoV-2 Genomes across Brazilian Geographical Regions, February 2020 to June 2021. Viruses 2021, 13, 1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, J.F.; Alencar, A.L.; Cunha, M.C.L.S.; Vasconcelos, A.O.; Cunha, G.G.; Miranda, R.B.; Filho, F.M.H.S.; Silva, C.; Gustani-Buss, E.; Khouri, R.; et al. Human Mobility Patterns in Brazil to Inform Sampling Sites for Early Pathogen Detection and Routes of Spread: A Network Modelling and Validation Study. Lancet Digit Health 2024, 6, e570–e579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitorino, L.C.; de Souza, U.J.B.; Oliveira Reis, M.N.; Bessa, L.A. The Impact of COVID-19 on the Indigenous Peoples Related to Air and Road Networks and Habitat Loss. PLOS Global Public Health 2022, 2, e0000166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, U.J.B. de; Macedo, Y. da S.M.; Santos, R.N. dos; Cardoso, F.D.P.; Galvão, J.D.; Gabev, E.E.; Franco, A.C.; Roehe, P.M.; Spilki, F.R.; Campos, F.S. Circulation of Dengue Virus Serotype 1 Genotype V and Dengue Virus Serotype 2 Genotype III in Tocantins State, Northern Brazil, 2021–2022. Viruses 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, U.J.B. de; Santos, R.N. dos; Giovanetti, M.; Alcantara, L.C.J.; Galvão, J.D.; Cardoso, F.D.P.; Brito, F.C.S.; Franco, A.C.; Roehe, P.M.; Ribeiro, B.M.; et al. Genomic Epidemiology Reveals the Circulation of the Chikungunya Virus East/Central/South African Lineage in Tocantins State, North Brazil. Viruses 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmo, R.F.; Nunes, B.E.B.R.; Machado, M.F.; Armstrong, A.C.; Souza, C.D.F. Expansion of COVID-19 within Brazil: The Importance of Highways. J Travel Med 2020, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza, U.J.B.; dos Santos, R.N.; de Melo, F.L.; Belmok, A.; Galvão, J.D.; de Rezende, T.C.V.; Cardoso, F.D.P.; Carvalho, R.F.; da Silva Oliveira, M.; Ribeiro Junior, J.C.; et al. Genomic Epidemiology of SARS-CoV-2 in Tocantins State and the Diffusion of P.1.7 and AY.99.2 Lineages in Brazil. Viruses 2022, 14, 659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evaristo Marcondes Cesar, A.; Elena Guerrero Daboin, B.; Cristina Morais, T.; Portugal, I.; De Oliveira Echeimberg, J.; Miller Reis Rodrigues, L.; Cauê Jacintho, L.; Daminello Raimundo, R.; Elmusharaf, K.; Eduardo Siqueira, C. Analysis of COVID-19 Mortality and Case-Fatality in a Low- Income Region: An Ecological Time-Series Study in Tocantins, Brazilian Amazon. Journal of Human Growth and Development 2021, 31, 496–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues Araujo, S.; Bezerra Sirtoli, D. Análise Da Distribuição Do Sars-COv-2 Nas Regiões de Saúde Do Estado Do Tocantins. Amazônia Science and Health 2021, 9, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ripley, B.D. The R Project in Statistical Computing. MSOR connections. The newsletter of the LTSN Maths, Stats & OR Network 2001, 1, 23–25. [Google Scholar]

- Wickham, H. Ggplot2. WIREs Computational Statistics 2011, 3, 180–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleveland, R.B.; Cleveland, W.S.; McRae, J.E.; Terpenning, I. STL: A Seasonal-Trend Decomposition. J. off. Stat 1990, 6, 3–73. [Google Scholar]

- Shu, Y.; McCauley, J. GISAID: Global Initiative on Sharing All Influenza Data–from Vision to Reality. Eurosurveillance 2017, 22, 30494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Toole, Á.; Pybus, O.G.; Abram, M.E.; Kelly, E.J.; Rambaut, A. Pango Lineage Designation and Assignment Using SARS-CoV-2 Spike Gene Nucleotide Sequences. BMC Genomics 2022, 23, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadfield, J.; Megill, C.; Bell, S.M.; Huddleston, J.; Potter, B.; Callender, C.; Sagulenko, P.; Bedford, T.; Neher, R.A. Nextstrain: Real-Time Tracking of Pathogen Evolution. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, 4121–4123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksamentov, I.; Roemer, C.; Hodcroft, E.; Neher, R. Nextclade: Clade Assignment, Mutation Calling and Quality Control for Viral Genomes. J Open Source Softw 2021, 6, 3773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagulenko, P.; Puller, V.; Neher, R.A. TreeTime: Maximum-Likelihood Phylodynamic Analysis. Virus Evol 2018, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giovanetti, M.; Slavov, S.N.; Fonseca, V.; Wilkinson, E.; Tegally, H.; Patané, J.S.L.; Viala, V.L.; San, E.J.; Rodrigues, E.S.; Santos, E.V.; et al. Genomic Epidemiology of the SARS-CoV-2 Epidemic in Brazil. Nat Microbiol 2022, 7, 1490–1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santangelo, O.E.; Provenzano, S.; Di Martino, G.; Ferrara, P. COVID-19 Vaccination and Public Health: Addressing Global, Regional, and Within-Country Inequalities. Vaccines (Basel) 2024, 12, 885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.W.; Ma, D.; Davoodian, A.; Ayutyanont, N.; Werner, B. COVID-19 Vaccination Decreased COVID-19 Hospital Length of Stay, in-Hospital Death, and Increased Home Discharge. Prev Med Rep 2023, 32, 102152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, S.Y.; Hussain-Alkhateeb, L.; Rivera Ramirez, T.; Al-Aghbari, A.A.; Chackalackal, D.J.; Cardenas-Sanchez, R.; Carrillo, M.A.; Oh, I.-H.; Alfonso-Sierra, E.A.; Oechsner, P.; et al. Factors Shaping the COVID-19 Epidemic Curve: A Multi-Country Analysis. BMC Infect Dis 2021, 21, 1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrissian, A.A.; Oyoyo, U.E.; Patel, P.; Lawrence Beeson, W.; Loo, L.K.; Tavakoli, S.; Dubov, A. Impact of COVID-19 Vaccine-Associated Side Effects on Health Care Worker Absenteeism and Future Booster Vaccination. Vaccine 2022, 40, 3174–3181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takasaki, Y.; Abizaid, C.; Coomes, O.T. COVID-19 Contagion across Remote Communities in Tropical Forests. Sci Rep 2022, 12, 20727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita, D.M.; Salvador, F.S.; Nali, L.H. da S.; Luna, E.J. de A. Decreasing Vaccine Coverage Rates Lead to Increased Vulnerability to the Importation of Vaccine-Preventable Diseases in Brazil. J Travel Med 2018, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra, P.N.B.; Atanasov, V.; Whittle, J.; Meurer, J.; Luo, Q.E.; Zhang, R.; Black, B. The Effect of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Elderly: Population Fatality Rates, COVID Mortality Percentage, and Life Expectancy Loss. Elder Law J 2022, 30, 33. [Google Scholar]

- Mueller, A.L.; McNamara, M.S.; Sinclair, D.A. Why Does COVID-19 Disproportionately Affect Older People? Aging (albany NY) 2020, 12, 9959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastorino, R.; Pezzullo, A.M.; Villani, L.; Causio, F.A.; Axfors, C.; Contopoulos-Ioannidis, D.G.; Boccia, S.; Ioannidis, J.P.A. Change in Age Distribution of COVID-19 Deaths with the Introduction of COVID-19 Vaccination. Environ Res 2022, 204, 112342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Gier, B.; van Asten, L.; Boere, T.M.; van Roon, A.; van Roekel, C.; Pijpers, J.; van Werkhoven, C.H.H.; van den Ende, C.; Hahné, S.J.M.; de Melker, H.E. Effect of COVID-19 Vaccination on Mortality by COVID-19 and on Mortality by Other Causes, the Netherlands, January 2021–January 2022. Vaccine 2023, 41, 4488–4496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaher, K.; Basingab, F.; Alrahimi, J.; Basahel, K.; Aldahlawi, A. Gender Differences in Response to COVID-19 Infection and Vaccination. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nana-Sinkam, P.; Kraschnewski, J.; Sacco, R.; Chavez, J.; Fouad, M.; Gal, T.; AuYoung, M.; Namoos, A.; Winn, R.; Sheppard, V.; et al. Health Disparities and Equity in the Era of COVID-19. J Clin Transl Sci 2021, 5, e99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silaghi-Dumitrescu, R.; Patrascu, I.; Lehene, M.; Bercea, I. Comorbidities of COVID-19 Patients. Medicina (B Aires) 2023, 59, 1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levitt, M.; Zonta, F.; Ioannidis, J.P.A. Comparison of Pandemic Excess Mortality in 2020–2021 across Different Empirical Calculations. Environ Res 2022, 213, 113754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, K.; Jang, M.; Kim, S.; Park, S.J.; Suh, H.S. Impact of COVID-19 on Disease-Specific Mortality, Healthcare Resource Utilization, and Disease Burden across a Population over 1 Billion in 31 Countries: An Interrupted Time-Series Analysis. EClinicalMedicine 2025, 85, 103315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGowan, V.J.; Bambra, C. COVID-19 Mortality and Deprivation: Pandemic, Syndemic, and Endemic Health Inequalities. Lancet Public Health 2022, 7, e966–e975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moraes, L.P.; Raposo, L.M. Impact of Vaccination and SARS-CoV-2 Variants on Severe COVID-19 Outcomes: A Cross-Sectional Study, Brazil, 2021-2022. Epidemiologia e Serviços de Saúde 2025, 34, e20240613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Klein, S.L.; Garibaldi, B.T.; Li, H.; Wu, C.; Osevala, N.M.; Li, T.; Margolick, J.B.; Pawelec, G.; Leng, S.X. Aging in COVID-19: Vulnerability, Immunity and Intervention. Ageing Res Rev 2021, 65, 101205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, B.A.S.; Hodel, K.V.S.; Fonseca, L.M. dos S.; Pires, V.C.; Mascarenhas, L.A.B.; da Silva Andrade, L.P.C.; Moret, M.A.; Badaró, R. The Importance of Vaccination in the Context of the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Brief Update Regarding the Use of Vaccines. Vaccines (Basel) 2022, 10, 591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maltezou, H.C.; Panagopoulos, P.; Sourri, F.; Giannouchos, T. V.; Raftopoulos, V.; Gamaletsou, M.N.; Karapanou, A.; Koukou, D.-M.; Koutsidou, A.; Peskelidou, E.; et al. COVID-19 Vaccination Significantly Reduces Morbidity and Absenteeism among Healthcare Personnel: A Prospective Multicenter Study. Vaccine 2021, 39, 7021–7027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janke, A.T.; Mei, H.; Rothenberg, C.; Becher, R.D.; Lin, Z.; Venkatesh, A.K. Analysis of Hospital Resource Availability and COVID-19 Mortality Across the United States. J Hosp Med 2021, 16, 211–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallrafen-Sam, K.; Quesada, M.G.; Lopman, B.A.; Jenness, S.M. Modelling the Interplay between Responsive Individual Vaccination Decisions and the Spread of SARS-CoV-2. Epidemics 2025, 51, 100831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abeln, B.; Jacobs, J.P.A.M. COVID-19 and Seasonal Adjustment. Journal of Business Cycle Research 2022, 18, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, A.; Reyes, B.; Burola, M.L.; Lomeli, A.; Escoto, A.A.; Salgin, L.; Rabin, B.A.; Stadnick, N.A.; Zaslavsky, I.; Tukey, R.; et al. Real-World Impact of COVID-19 Vaccination, Household Exposure, and Circulating SARS-CoV-2 Variants on Infection Risk and Symptom Presentation in a U.S./Mexico Border Community. Front Public Health 2025, 13, 1497390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González Rodríguez, J.L.; Oprescu, A.M.; Muñoz Lezcano, S.; Cordero Ramos, J.; Romero Cabrera, J.L.; Armengol de la Hoz, M.Á.; Estella, Á. Assessing the Impact of Vaccines on COVID-19 Efficacy in Survival Rates: A Survival Analysis Approach for Clinical Decision Support. Front Public Health 2024, 12, 1437388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Huang, H.; Ju, J.; Sun, R.; Zhang, J. Impact of Vaccination on the COVID-19 Pandemic in U.S. States. Sci Rep 2022, 12, 1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira Roster, K.I.; Kissler, S.M.; Omoregie, E.; Wang, J.C.; Amin, H.; Di Lonardo, S.; Hughes, S.; Grad, Y.H. Surveillance Strategies for the Detection of New Pathogen Variants across Epidemiological Contexts. PLoS Comput Biol 2024, 20, e1012416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeiser, F.A.; Donida, B.; da Costa, C.A.; Ramos, G. de O.; Scherer, J.N.; Barcellos, N.T.; Alegretti, A.P.; Ikeda, M.L.R.; Müller, A.P.W.C.; Bohn, H.C.; et al. First and Second COVID-19 Waves in Brazil: A Cross-Sectional Study of Patients’ Characteristics Related to Hospitalization and in-Hospital Mortality. The Lancet Regional Health - Americas 2022, 6, 100107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brito, A.F.; Semenova, E.; Dudas, G.; Hassler, G.W.; Kalinich, C.C.; Kraemer, M.U.G.; Ho, J.; Tegally, H.; Githinji, G.; Agoti, C.N.; et al. Global Disparities in SARS-CoV-2 Genomic Surveillance. Nat Commun 2022, 13, 7003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perez-Guzman, P.N.; Knock, E.; Imai, N.; Rawson, T.; Santoni, C.N.; Alcada, J.; Whittles, L.K.; Thekke Kanapram, D.; Sonabend, R.; Gaythorpe, K.A.M.; et al. Epidemiological Drivers of Transmissibility and Severity of SARS-CoV-2 in England. Nat Commun 2023, 14, 4279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Outcome | df (Model/ Residual) |

MS (Model/ Residual) |

F-value | p-value | Significant Comparisons (Tukey HSD, 95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Confirmed Cases | 2 / 290 | 1.32x108 / 3.73x106 | 35.5 | <0.001 | IC > PV (p <0.001); WV > PV (p = 0.0106); WV > IC (p <0.001) |

| Deaths | 2 / 290 | 7.71x104 / 3.81x102 | 202.0 | <0.001 | IC > PV (p <0.001); WV > PV (p <0.001); WV > IC (p <0.001) |

| Hospitalizations | 2 / 290 | 2.26x105 / 8.97x102 | 252.0 | <0.001 | IC > PV (p <0.001); WV > PV (p <0.001); WV > IC (p <0.001) |

| Incidence | 2 / 290 | 5.16x105 / 1.46x104 | 35.5 | <0.001 | IC > PV (p <0.001); WV > PV (p = 0.0108); WV > IC (p <0.001) |

| Mortality | 2 / 290 | 3.01x102 / 1.49 | 202.1 | <0.001 | IC > PV (p <0.001); WV > PV (p <0.001); WV > IC (p <0.001) |

| Vaccination Coverage | 2 / 290 | 7.59x105 / 4.85x102 | 1564.0 | <0.001 | IC > PV (p <0.001); WV > PV (p <0.001); WV > IC (p <0.001) |

| Vaccine-to-Case Ratio | 2 / 290 | 9.71x104 / 1.20x103 | 8.11 | <0.001 | WV > PV (p = 0.0005) |

| Outcome variable | Adj. R² | Deviance explained (%) | EDF (Vaccination) | F-statistic | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Confirmed cases | 0.796 | 81.1 | 4.66 | 35.13 | *** |

| Deaths | 0.887 | 89.5 | 4.77 | 47.69 | *** |

| Hospitalizations | 0.907 | 91.4 | 5.09 | 51.11 | *** |

| Incidence | 0.615 | 64.0 | 4.23 | 16.17 | *** |

| Mortality | 0.822 | 83.4 | 4.63 | 30.83 | *** |

| Vaccination Coverage | 1 | 100 | 3.08 | 4.92 | *** |

| Vaccine-to-Case Ratio | 0.524 | 55.6 | 3.69 | 6.38 | *** |

| Outcome | β₁ | p-value β₁ | β₂ | p-value β₂ | β₃ | p-value β₃ | Adj. R² |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Confirmed cases | +52.44 | <0.001 | +64.45 | 0.881 | –70.14 | <0.001 | 0.395 |

| Deaths | +0.62 | <0.001 | –0.81 | 0.919 | –0.88 | <0.001 | 0.345 |

| Hospitalizations | +0.98 | <0.001 | +2.35 | 0.853 | –1.46 | <0.001 | 0.423 |

| Incidence rate | +3.40 | <0.001 | +0.51 | 0.988 | –4.49 | <0.001 | 0.284 |

| Mortality rate | +0.04 | <0.001 | –0.08 | 0.889 | –0.06 | <0.001 | 0.306 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).