1. Introduction

The global rethink of healthcare systems and models prompted by the 2019-2020 pandemic [

1]. led to a renewed focus on prevention strategies such as lockdown, social distancing, and the use of masks [

2,

3,

4].

In Catalonia, Igualada was one of the first cities to implement a strict lockdown. Given the presence of several key health institutions in the area, a digital LL for health and wellbeing was launched there in 2020. Actors from across the Quadruple Helix (4-H) [

5] were brought together by this initiative to collaboratively address health and wellbeing challenges through decentralised work via DSI.

This first experiment in Igualada laid the foundations for a wider network of digital LLs, unified under the Collaboratory Catalunya project. These labs addressed specific territorial challenges, and eventually a thematic digital LL focused on health and wellbeing was created to serve the whole of Catalonia.

This study evaluates the Collaboratory Catalunya project through a hybrid methodology that combines qualitative and quantitative approaches, collecting data in parallel to explore and specify what has been the effectiveness, efficiency, impact and transformative capacity of this project. The findings underscore the pivotal function of public administrations, interdisciplinary collaboration, and digital competencies acquired. Moreover, they also emphasise the significance of sustainable funding models and underscore the growth of collaborative initiatives that have gained traction within this ecosystem.

The paper is structured as follows: first, the conceptual frameworks underpinning the study are introduced and the research question is formulated by a literature review. The methodology section then details the process of data collection and analysis, followed by a discussion of the findings and conclusions.

2. Materials and Methods

The corresponding authors will make all materials used for this research, as well as data collection instruments (survey and interview guides) and coding protocols, available upon request. The information collected and looked at in this study has been made anonymous to protect the privacy of the people involved. It is stored safely at the i2CAT Foundation.

The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles set out in the European Code of Conduct for Research Integriy. Participants were informed that sessions could be audio-recorded and transcribed with an automated service; transcripts were pseudonymised before analysis. Each participant was asked to give their consent before taking part. No personal information was recorded.

No computer code beyond standard spreadsheet functions (Microsoft Excel) was used for descriptive statistics. Qualitative analysis followed a manual coding process, as described in

Section 3.2.

Transcription. Audio from interviews/meetings was transcribed using Tactiq (automatic transcription), and all transcripts were manually reviewed and corrected by the research team prior to analysis.

Use of AI and automated tools. Generative AI tools were not used to generate data, graphics, or analyses. GenAI was used only for superficial text editing (grammar, spelling, formatting). The use of Tactiq was limited to speech-to-text transcription; it did not perform coding, summarization, interpretation, or analysis.

Statement on the use of AI. We use Tactiq solely to obtain an automated transcript of interviews. This is followed by manual verification and correction. We do not use GenAI to generate text, data, figures or to perform analysis.

3. Literature Review

This section reviews the most relevant studies on responsible and social innovation, collaboratories, and LLs, with a special focus on their application in the context of Catalonia, Spain. The aim is to position the study within the existing theoretical and practical frameworks and, ultimately, to present the research question guiding this work.

3.1. Responsible Innovation (RI)

RI underscores the importance of transparency, inclusion, reflexivity, anticipation, and responsiveness [

6] It adopts a holistic approach that seeks to address ecological and societal challenges in an integrated manner. [

7] Argue that effective RI requires a sustained commitment to continuous learning, integration of diverse perspectives, and productive collaboration, as context, process, learning, and continuous innovation are key components of responsible practice.

3.2. Digital Social Innovation (DSI)

Innovation is the application of new ideas to develop or improve products and services [

8]. When it addresses social challenges more effectively, sustainably, or equitably than existing solutions, it becomes Social Innovation (SI), focused on social rather than commercial value [

9,

10].

Digital Social Innovation (DSI) emerges when ICTs are integrated into SI processes. DSI leverages digital tools to address social and environmental challenges, typically through participatory and networked methods [

11,

12]. ICTs play a cross-cutting role in fostering collaboration, enabling knowledge sharing, and linking citizens, communities, and institutions. RDSI refers to digital innovation that incorporates social responsibility, aligning technological development with social needs and ethical values.

Both RI and SI highlight inclusive, and collaborative approaches that involve diverse stakeholders, ensuring that innovation processes and outcomes reflect broad societal values [

13]. The growing relevance of these models is reflected in empirical research, such as [

14], which explores the dynamics and impacts of multi-stakeholder collaboration in innovation ecosystems.

3.3. Collaboratories

Collaboration is a fundamental component of research and innovation. The term “collaboratory” means co-laboratory or common laboratory and refers to a centre/laboratory without walls connected via the Internet [

15,

16,

17]. Therefore, the collaboratory facilitates virtual work in distributed communities [

18]. it improves access to scarce resources, supports remote cooperation between researchers, and enables sustained, inter-institutional collaboration.

3.4. Living Labs (LLs)

LLs are user-centred open innovation environments that bring together actors from the 4-H (academia, public administration, industry, and civil society) to co-create and test solutions in real-world settings [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19]. They combine research and innovation and put end-users at the centre [

20], although civil society participation remains a challenge [

21].

LLs enable experimentation and stakeholder collaboration, supported by policy, integration, formal partnerships, and proof of concept [

22]. Digital technologies enhance participation, as seen in local health-focused LLs in the United Kingdom (UK) [

23,

24], low- and middle-income countries [

25], and community wellbeing initiatives [

26], although technology use remains uneven [

26].

Studies increasingly address LL impact, highlighting benefits for the alignment of innovation and economic outcomes [

28], while noting persistent barriers [

29] and gaps in effectiveness [

30,

31]. LLs are also aligned with the values of RI values such as inclusion, reflexivity, and sustainability, although the integration of RI principles requires intentional design [

32].

3.5. Living Labs (LLs) in Catalonia

Catalonia has a strong tradition of LL initiatives. A pioneering example is the Citilab’s Seniorlab project, which empowered older people to co-design digital technologies [

33]. Building on this, LivingLab4Carers demonstrated the value of user participation in co-developing digital platforms and improving communication between stakeholders [

34].

In Catalonia, efforts were made to deepen the LL concept, focusing on scalability, universalisation, and real-world testing of user-centred design to address societal challenges [

35,

36]. Media and digital culture were seen as fertile ground for citizen-driven innovation and co-created content [

37].

Empowering citizens through open data emerged as a strategic priority, enabling them to transform public services in a meaningful way [

38]. Hackathons became key participatory tools, fostering local collaboration through co-defining, co-designing, and co-creating around shared challenges [

39].

3.6. Collaboratory Catalunya

The Collaboratory Catalunya project emerged from long-term research on the development of Universal Innovation Ecosystems [

36,

37,

38,

39,

40]. In line with [

42], the project was launched in 2019 and promoted by the Catalan Government (Generalitat de Catalunya) with the aim of designing and building a universal research and innovation ecosystem in Catalonia, through citizen participation and the strategic use of the Internet.

ICTs are key tools in this project, serving as enablers for the creation of these territorial networks of actors to address social and environmental challenges in a collaborative way [

43]. The project follows the LL methodology, involving 4-H actors, to map emerging and existing initiatives, identify shared challenges, and co-develop DSI projects.

Collaboratory Catalunya can therefore be described as a regional digital LL that aims to democratise innovation and foster inclusive, place-based solutions with global relevance.

3.7. Research Question

Today’s society faces complex social and environmental challenges. While public administrations and businesses seek solutions, academic research is often difficult to translate into practice. Meanwhile, the Internet has become a universal tool for connectivity and innovation. In 2024, 5.44 billion people (67.1% of the world’s population) were Internet users [

44]. Universal Internet access is supported by the United Nations (UN), the International Telecommunication Union (ITU), and many governments, positioning it as the basis for global research and innovation networks.

In this context, the physical or virtual nature of LLs becomes secondary [

45]. With a computer and Internet access, users can participate in LLs, provided by ICTs that support co-creation and collaboration of stakeholders [

46]. Local and European Union (EU) policies are increasingly promoting co-design and digital innovation in LLs [

22].

[

47,

48] introduced the idea of a “universal innovation ecosystem,” like the universalisation of healthcare and education after World War II [

18]. On this basis, [

43] helped create a regional digital LL throughout Catalonia, launched in 2019. As thematic links emerged such as health, the Health and Wellbeing LL were created in 2020 as a cross-cutting digital LL, later scaled through the INTEGER Horizon Project [

49] and replicated in Senegal.

Given the transformative potential (and risks) of digital innovation, and in line with [

28] and [

31], this raises a key question: to what extent (and through what mechanisms) can a regional digital LL be effective, efficient and impact and/or transform the society of a territory by fostering DSI 4-H collaboration?

4. Methodology

This paper presents research that takes a mixed methods approach [

50] to explore both the views and experiences of participants, as well as the broader impact of the project. Qualitative research seeks to delve into specific experiences, exploring meanings through texts, narratives, or visual data and is often based on thematic analysis [

51]. It inductively investigates real-world environments to generate narrative descriptions and develop case studies [

52]. By contrast, quantitative research involves measuring and analysing numerical data to generate insights that can be generalized [

53,

54].

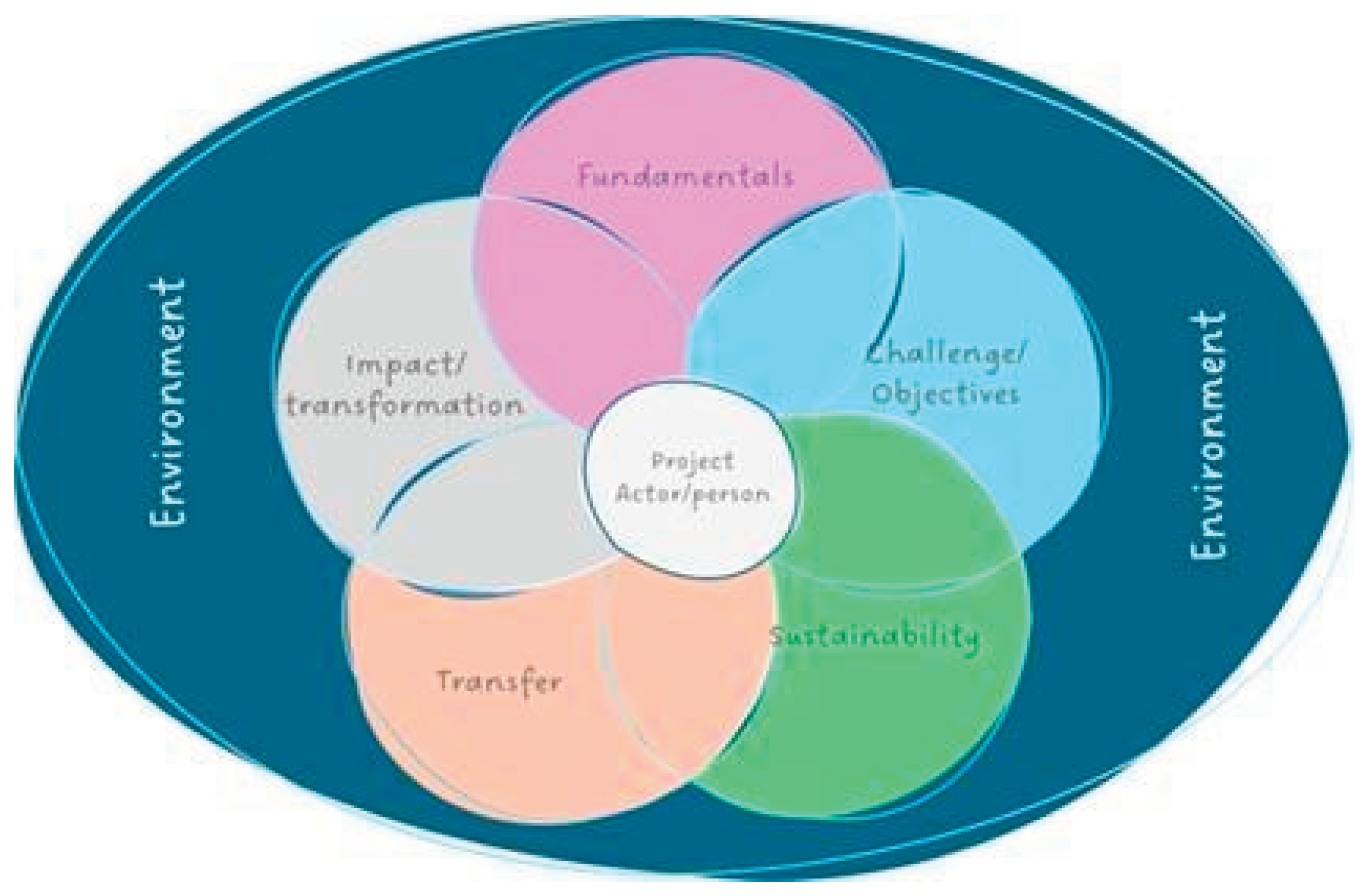

Both methodological approaches are based on a person-centred model, in which individuals/actors are at the heart of the analysis. Their engagement in systemic environments is explored through key dimensions: Fundamentals, Challenges/Objectives, Sustainability, Transfer, Impact/Transformation, and Environment (see

Figure 1).

The integration of both methods provided a holistic perspective, i.e. a more complete and nuanced understanding of what each method could achieve by itself. Therefore, this approach makes the most of the strengths of each method by addressing different facets of the research question. Furthermore, this approach enables the identification of both facilitators and barriers, providing insights into the model’s potential for replication in other contexts.

4.1. Data Collection

The research design follows a convergent parallel structure [

55], in which qualitative and quantitative data were collected and analysed simultaneously but independently, and then interpreted together to ensure robust triangulation of findings.

Participants included the main actors involved in the project, representing 4-H: academia, industry, public administration, and civil society. This approach allowed a holistic view and the qualitative component contributed to a detailed view of the evolution and impact of the project.

The research adhered to the ethical guidelines, as informed consent was obtained from all participants, and the use of data was limited to the purposes of the study, guaranteeing confidentiality and privacy.

The selection of potential participants followed a strategy of sampling convenience and was initially based on their participation in LL, to include individuals who participated regularly in the different tasks, activities, workshops, etc. From there, the sample had to be varied in terms of geographical origin (throughout Catalonia), age range, gender, level of education, and helix to minimise selection bias [

56]. In the case of the industry helix, it was not requested to specify the type of industry to which they belonged and regarding the public administration helix, the participants were from local or regional institutions.

4.1.1. Semi-Structured Interviews

Initially, it was established that the sample size would be 20% of the qualitative sample (n=104); that means approximately 20 interviews, but due to time constraints, only 15 interviews could be done, although as they were being conducted, it was observed that the sample was already saturated [

57]. Of these 15 interviewees, only 10 of them answered the online survey.

The interview outline consisted of thirty-five questions organised in seven thematic blocks, the first of which covered socio-demographic data. Subsequent blocks focused on project impact, perceived challenges and opportunities, and participants’ expectations. The interviews were designed to explore the reasons and processes underlying participants’ experiences [

58], with flexibility for both interviewer and interviewee to follow emerging threads of discussion.

The interviews were conducted via Zoom fifteen online interviews were conducted via Zoom. They lasted between thirty and forty-five minutes, were recorded with participants’ consent, and transcribed using Tactiq, an AI-based transcription tool. Transcripts were independently reviewed by two researchers to ensure accuracy.

Table 1 summaries of the sample by age range, gender, and helix affiliation. While Generation Y (GenY) shows a balanced representation, other age groups were less evenly distributed. All participants completed tertiary education.

4.1.2. Online Surveys

Surveys contribute to describing and exploring variables and constructs of interest [

59]. The survey consisted of twenty-five questions organised into seven blocks: the first block collected socio-demographic information, while the remaining six blocks corresponded to the dimensions outlined in

Figure 1. The questions were dichotomous (yes/no), open-ended, and multiple choice.

Data were collected online via an email invitation containing a link to a Google Forms survey, sent to 336 individuals (N = 336). Of these individuals, 104 valid responses were collected (n = 104), providing a robust and diverse sample in terms of age, gender, and role within 4-H. The most represented age group was Generation X (Gen X), followed by Generation Y (Gen Y), Baby Boomers, and Generation Z (Gen Z).

Table 2 also shows that the gender distribution was almost equal (50.96% men, 49.03% women). By sectors, the respondents were mainly from industry (32.69%) followed by academia (24.03%), civil society (23.07%), and public administration (20.19%). Finally, in terms of education, all Boomers and GenY respondents reported tertiary education, as did 88% of GenX respondents.

4.2. Data Analysis

The data analysis was carried out independently by three researchers to increase credibility and reduce bias. Microsoft Excel was used to process and analyse the quantitative data obtained from online surveys, enabling descriptive statistical analysis.

The analytical process for qualitative data derived from semi-structured interviews, the analytical process followed four main stages: transcription, interpretation, coding, and thematization [

60]. Tactiq-generated transcripts were thoroughly reviewed and validated. A content analysis was carried out manually following the methodology described by [

61]. An inductive approach was used to allow topics to emerge from the data. The process was meticulous, guaranteeing consistent and meaningful outcomes.

5. Results

Following the work carried out by [

62,

63], the data is analyzed by gender. The option of analysis by helix is ruled out because both samples are unbalanced and may generate certain biases, although it is an interesting option for future research if a more varied sample can be obtained in this regard.

The main objective of analysing data by gender and by age range is to understand how different participants perceive the regional digital LL. This approach helps to identify the specific needs, priorities, and limitations of different demographic groups, enabling the development of more effective and inclusive policies, programmes, and interventions.

The data collected through online surveys and semi-structured interviews are analyzed separately below.

5.1. Semi-Structured Interviews

The qualitative analysis provided a deeper insight into participants’ perceptions of the project’s impact and sustainability. The sample was fairly balanced in terms of gender, and some gender differences were observed. In general, men emphasise the expansion of the professional network and the transformation in the perception of DSI, while women emphasise the practical benefits of adopting digital tools and digital inclusion, focusing on accessibility and practical transformation through digitalisation. The difficulties in financing are highlighted equally by both groups. And as for work methodologies, women talked more about how digitalization influenced daily operations and accessibility, suggesting a more process-oriented perspective.

The five key themes that emerged are presented below. Some relevant quotes have been included to reinforce the arguments derived from the analysis. These appear in quotation marks and italics, and in brackets, the interviewee who said the quote appears with the code assigned, i.e. I.

5.1.1. DSI

Most interviewees were already familiar with the concept of DSI, and the project significantly improved their understanding and practical application. DSI was perceived as a tool with strong transformative potential, especially in shaping processes and rethinking project design.

“I perceive DSI as the process of positive social transformation from the development of the Internet as an evolutionary differential element of humanity.” (I31)

5.1.2. Collaboration and Strategic Alliances

The project played a catalytic role. It established new alliances and strategic collaborations. These were between various institutions. This was thanks to the promotion of innovation. This promotion took place in different regions of Catalonia. In fact, many participants observed an increase in collaboration between organisations that previously had limited or null interaction.

“We have established collaborations that previously seemed impossible.” (I1)

Several organisations also adopted more participatory approaches to internal processes, suggesting that collaborative dynamics extended beyond inter-organisational levels.

5.1.3. Adoption of Digital Tools

Participation in the project has inspired some organisations to redefine their objectives and adopt and/or increase the use of digital tools (e.g. Mural or Mentimeter) and LL methodology.

“We started using digital tools that we didn't even know before.” (I5)

“Digitalisation has accelerated the way we manage projects.” (I11)

5.1.4. Digital Inclusion

Digital inclusion in the field of health and wellbeing has been the most debated topic. Moreover, participants highlighted the importance of addressing digital inequalities, particularly in the fields of education and youth.

“We have learned that the digital divide is bigger than we thought.” (I15)

The project also enabled small institutions to access innovative spaces that had previously been out of their reach, thereby promoting more equitable participation.

5.1.5. Sustainability and Funding

Financing is a key issue, with a need to find resources to support the project. There are plans to promote collaborative projects with structured financing. Moreover, it is vital to make sure that the project is sustainable in the long term and a success in the future if institutional support is to be secured.

“Without more economic resources, many projects will not be able to continue.” (I14)

5.2. Online Surveys

The online survey aimed to assess participants’ knowledge and perceptions of DSI before and after their participation in the project, as well as in the dimensions presented in

Figure 1. The combination of dichotomous, multiple-choice, and open-ended questions allowed for both quantitative analysis and qualitative insights to be obtained.

The analysis of the data collected was carried out both by gender and by age group and it is presented below. Some relevant quotes have been included to reinforce the arguments derived from the analysis. These appear in quotation marks and italics, and in brackets, the respondent who said the quote appears with the code assigned, i.e. R#.

5.2.1. DSI - The Project

One of the project's key outcomes was a shift in participants' understanding of DSI, evolving from a technology-centric concept to a catalyst for social transformation and collaboration. This shift in perception was encouraged through workshops and training on DSI and Advanced Digital Technologies (ADT) [

64], which fostered a systemic and intersectoral approach to innovation. The project also strengthened links between the organisations and boosted regional development.

“Over time, a more consolidated ecosystem has emerged, with models of citizen innovation, associated public policies, and local, regional, national, and international networks and collaborations, although there is still a need for greater interconnection and mutual support, even by the government, because the great potential lies in both responding to challenges and strengthening democracy. I came to understand that a cultural change was also necessary.” (R36)

Young participants, especially those from schools or training centres, showed a greater awareness of DSI. In general, Baby Boomers (Boomers) and GenX stressed the importance of promoting DSI more widely. In addition, women of all age groups tended to have a little more prior knowledge than men.

5.2.2. Dimension 1: Environment

This dimension refers to the ecosystem in which DSI occurs actors, institutions, and support mechanisms. The project increased participants’ awareness of DSI and improved connectivity, especially among younger generations, which reported greater access to new actors and initiatives.

“(The project is) an opportunity to meet the different agents and projects that are being carried out in different territories.” (R65)

It should be noted that participation in European-level projects increased particularly among women, according to 50% of Boomers and 18% of GenX. The project also strengthened links with the public sector, with younger participants reporting improved access to public institutions and support structures.

Another impact was the emergence of DSI-based technologies and business models. 33% of Boomer men, 13% of GenX women, 11% of GenX men, and 8% of GenY women explored/adopted these models. While intergenerational interest was evident, Boomer men seemed to be the most likely to recognise the potential of these innovations.

5.2.3. Dimension 2: Fundamentals

This dimension focuses on the fundamental values that underpin the project. The participants constantly highlighted collaboration, innovation, social impact, territorial commitment, networking, and the active participation of local actors and communities as key factors, with collaboration being the most recurring topic.

“Over time, this perception has evolved, understanding that it is not only about technology but also about involving communities, collaborating with various actors, and creating sustainable and inclusive solutions.” (R99)

The project was seen not only as a vehicle for technological change, but also as a platform to promote a culture of innovation rooted in social purpose and regional development.

Organisationally, the project influenced internal innovation practices and fostered more collaborative working cultures. Participants from all sectors reported changes in problem-solving approaches and digital strategies. Notably, Boomer women emphasised significant changes in the strategic planning and team dynamics related to their participation in the initiative.

“Cross-sector collaboration, community transformation, awareness raising and improved quality of life.” (R95)

5.2.4. Dimension 3: Transformation

This dimension reflects the project’s influence on the participants’ DSI capacity and collaborative innovation. Many reported an improvement in their skills in project design and management, involving end users, and fostering interdisciplinary collaboration.

“Now I understand how digital social innovation can transform our projects.” (R36)

In fact, women particularly valued the project’s role in connecting researchers with stakeholders, promoting shared learning and ecosystem growth. Economic impacts were also observed. Among men, 46.1% of Boomers and 42.8% of GenX reported improving networks for competitiveness. Among women, 24% of GenX reported better contacts and 20.7%, new ideas; in GenY, more than 40% of women and 50% of men reported increased ideation and networking.

5.2.5. Dimension 4: Transfer

This dimension highlights how the project facilitated knowledge transfer and collaboration, the latter being the common denominator. Women emphasised the exchange of social and institutional knowledge, while men focused on business and technical applications.

“It has given me a lot of knowledge and allowed me to find out what is being done in the rest of Catalonia, a source of extraordinary and very productive connections.” (R62)

Boomer men highlighted the creation of networks of actors, while women showed great DSI capacity and digital skills, although they also noted their lower access to formal spaces.

GenX women were more involved in structured collaborations, while men focused on digital tools and business outcomes. GenY women valued flexibility, institutional learning, and social solutions, and GenY men inclined towards start-ups and structured networks. Finally, GenZ women preferred formal learning formats, while men opted for informal collaboration linked to the Digital Media Ecosystem (DME).

5.2.6. Dimension 5: Sustainability

This dimension reflects the long-term sustainability and viability of the project. In general, participants recognised that sustainability in DSI requires not only financial and technical strategies, but also collaborative and socially cohesive approaches to ensure long-term success.

Gender differences were observed: women emphasized social sustainability, focusing on lifelong learning and inclusion, while men prioritized economic and technological aspects such as funding and infrastructure. Despite these differences, everyone agreed on the key factors: continuous training, cross-sectoral collaboration, and inclusive economic models.

“Without more financial resources, many projects will not be able to continue... Funding remains the main challenge for our initiative.” (R14)

Young generations, especially GenY and GenZ, considered that the project fostered territorial resilience and sustainable resource generation, with GenZ showing the most optimistic. Boomers positively valued the impact, while GenX had mixed opinions, as they considered sustainability more as a future goal.

5.2.7. Dimension 6: Challenge/Objectives

This dimension highlights the main challenges and opportunities perceived during the project. Common challenges included lack of funding, limited training, weak institutional support, resistance to change, and poor coordination. Despite the obstacles, the participants identified significant potential for innovation and social impact.

“The great potential is both in responding to the challenges and in strengthening democracy.” (R36)

Regarding challenges, women emphasized training deficiencies, while men focused on financial issues and internal resistance. Regarding opportunities, men valued institutional support and networking, while women prioritized empowerment and governance.

GenX and GenY pointed to problems of collaboration and communication, while Boomers highlighted the lack of tangible results. In addition, GenY highlighted DME, while GenX emphasised collaboration.

5.3. Policy-Level and Institutional Impacts

Beyond the organisational and individual results, the project has had a significant impact on the public digital policy of Catalonia. Since 2016, in collaboration with the Government of Catalonia (Generalitat de Catalunya), the project has contributed to shaping several key strategies, which are presented below:

This government initiative promoted a 4-H innovation model to foster inclusive digital, social, and labour innovation throughout Catalonia.

Charter of Digital Rights [

66]

The project supported the development of the report "Building Digital Rights and Responsibilities", which laid the foundations of the Catalan Charter of Digital Rights. Although not formally adopted at EU level, it enriched international debates on digital ethics and citizen’s rights.

Strategy for Digital and Territorial Social Innovation [

67]

The project shaped the vision and methods of this strategy, strengthening regional equity through collaborative innovation and greater participation of territorial actors.

National Strategy for Socio-Digital Inclusion [

68]

The project served as a methodological and experimental reference to identify digital inclusion gaps and provide co-creation spaces that institutionalised the 4-H innovation model within the official framework of the digital inclusion policy of Catalonia.

6. Discussion

Data analysis highlights the crucial role of the Internet as the foundation of the regional digital LL, advancing universal and democratic innovation. It has created inclusive spaces. It has also created digital tools. These outcomes are aligned with previous research by [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48]. New collaboration structures were fostered, territorial development was strengthened, and distributed innovation was expanded due to connecting various actors.

Important impacts include improving cross-sectoral collaboration, digital transformation of institutions, and the creation of strategic networks and initiatives in areas with limited access to DSI. Two initiatives that have emerged are Co-Ebre Lab, which is a collaborative DSI space and Video Art Games-Experience, which is an event that combines videogaming, audiovisual art and digital leisure. Moreover, the use of digital tools and participatory methods has transformed organisational processes and cultures, especially in the fields of healthcare and wellbeing, although progress in education and culture remains limited. The project also helped to reduce the digital divide, especially for vulnerable groups.

Quantitatively, 66% of survey respondents reported a change in DSI perception, with 86% of women and 70% of GenY participants pointing to this change. Around 38% of them were introduced to DSI through the project, going from seeing it as a technical concept to recognizing its strategic and territorial importance.

Challenges included financial constraints and institutional resistance, mainly in hierarchical organisations. Technological limitations and lack of digital skills were less common but present in sectors less familiar with digital innovation. Nevertheless, the project successfully established strategic partnerships, encouraged participation and promoted mutual learning. Robust leadership proved indispensable to the coordination of ecosystems.

The collaboration between the 4-H actors was central. ICTs that allow communication, co-creation, and the development of new ideas was supported the results of [

11,

12]. The greatest impact of the project lies in fostering internal innovation. It also has an impact on shaping organisational cultures and digital strategies. It also stimulated social entrepreneurship, particularly among women, by linking their commitment to addressing real social challenges. Thus, DSI proves to be a key facilitator of gender-sensitive innovation and inclusive entrepreneurship.

This regional digital LL has its own characteristics that encompasses the entire Catalan territory and is based on the Internet, and in turn, is formed by individuals/institutions of the 4-H that co-define challenges and co-design potential solutions in a collaborative way. The methodological approach used, mixed method, is quite common and can be replicated and adapted to other contexts. In this case, the knowledge and experience acquired have been used to co-create three LLs focused on health and wellbeing in three European regions (Catalonia (Spain), Kraków (Poland) and Hamburg (Germany)) within the framework of the European INTEGER project and also has been transferred to the LLs in Senegal project that is developed jointly with the Catalan Agency for Cooperation and Development. Therefore, despite the territorial, socio-economic and political characteristics of its own, it is possible to adapt this methodology in other contexts.

7. Conclusions

The creation of Collaboratory Catalunya as a regional digital LL has advanced the dissemination and implementation of DSI throughout Catalonia, extending its influence on Europe and Africa. The project defends the right to innovation, emphasizing that everyone should actively participate in innovation, aligning itself with the concept of decentralized laboratory [

18] and the 4-H innovation model [

5].

The project is guided by the fundamental values of RDSI. Inspired by the Catalan Charter of Digital Rights (2019), the European Declaration of Digital Rights (2023), and the international efforts of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) and the UN to promote equitable and sustainable innovation, these values reflect a commitment to social justice, technological equity, open access to knowledge and digital inclusion.

The Internet and ICTs are essential for enabling communication, collaboration, and decentralised innovation among 4-H stakeholders, regardless of geography. This fosters social impact and influence public policies towards broader societal transformation.

However, the study has limitations: some 4-H groups are under-represented, and GenZ/Boomers participate less -especially in interviews- which may introduce bias; and although online interviews can reduce travel/time, they limit non-verbal richness. These patterns align with known living labs pitfalls – misalignments, recruiting labelling, and communications gaps – as noted in a recent work [

69]: “Findings highlight three key challenges. First, misalignment between assumed and actual stakeholder needs hindered industry engagement. Second, recruitment was complicated by the ambiguous use of “prosumer”, causing confusion among participants. Third, communication gaps and personnel changes disrupted the integration of user feedback into development cycles.

This research lays the foundations for future studies on emerging technologies such an Artificial Intelligence (AI) to further universalize innovation ecosystems. As [

70] noted, “the Internet is for everyone.” In this new era, AI could also be. In addition, future work can improve the design of data collection to balance participation by helix, age and even gender. Finally, it will be interesting to study the similarities and differences in LLs that are currently being created in Africa and those that have yet been created in Europe and that have taken all this work as a starting point.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used “Conceptualization, F.C. and M.M.C; methodology, F.C. and M.M.C; software, F.C. and M.M.C; validation, F.C. and M.M.C,; formal analysis, F.C. and M.M.C; investigation, F.C. and M.M.C; resources, F.C. and M.M.C; data curation, F.C. and M.M.C; writing—original draft preparation, F.C. and M.M.C; writing—review and editing, F.C. and M.M.C; visualization, F.C. and M.M.C; supervision, F.C. and M.M.C; project administration, M.M.C; funding acquisition, M.M.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.” Please turn to the CRediT taxonomy for the term explanation. Authorship must be limited to those who have contributed substantially to the work reported.

Funding

This research received support from the Government of Catalonia (Generalitat de Catalunya) (no specific grant number) and from the i2CAT Foundation (internal R&D funds). The APC was funded by the i2CAT Foundation.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study because it involved non-interventional interviews with adult professionals about their work practices; no special-category/sensitive personal data (e.g., health, biometric, or political data) were collected; all records were pseudonymized/anonymized prior to analysis; and the study posed minimal risk to participants. The study complied with the Declaration of Helsinki and with GDPR principles (data minimization, purpose limitation, and security).

Informed Consent Statement

All participants provided informed consent (information sheet and consent to audio-record and transcribe). Participation was voluntary and could be withdrawn at any time without consequence.

Data Availability Statement

Due to privacy and ethical restrictions, full transcripts are not publicly available. Anonymized excerpts and the coding framework are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We thank all study participants for their time and insights. We are also grateful to the members of the Digital Society Technologies research group at i2CAT for administrative and technical support. During data processing, we used Tactiq for automated transcription of recorded sessions; all transcripts were manually reviewed and corrected by the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| LLs |

Living Labs |

| LL |

Living Lab |

| DSI |

Digital

Social Innovation |

| RDSI |

Responsible

Digital Social Innovation |

| ICTs |

Information

and Communication Technologies |

| 4-H |

Quadruple

Helix |

| SI |

Social

Innovation |

| RI |

Responsible

Innovation |

| UK |

United

Kingdom |

| UN |

United

Nations |

| ITU |

International

Telecommunication Union |

| EU |

European

Union |

| ADT |

Advanced

Digital Technologies |

| DME |

Digital

Media Ecosystem |

| UNESCO |

United

Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization |

References

- World Health Organisation (WHO). Coronavirus. 2019. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/coronavirus#tab=tab_1 (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Crittenden, F. , & Fang, C. Preventive Medicine introduction. YJBM 2021, 94, 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Kisling, L. A. , & Das, J. M. Prevention strategiesStatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Najafi, M. B. , & Javanmard, S. H. Post-COVID-19 syndrome mechanisms, prevention and management. International Journal of Preventive Medicine 2023,14, 59. [CrossRef]

- Carayannis, E. G. , & Campbell, D. F. Mode 3 and Quadruple Helix: toward a 21st century fractal innovation ecosystem. International Journal of Technology Management, 2009, 46, 201-234. [CrossRef]

- Fraaije, Aafke, & Steven M. Flipse. Synthesizing an Implementation Framework for Responsible Research and Innovation. Journal of Responsible Innovation 2019, 7, 1–25. [CrossRef]

- Fisher, E. , Smolka, M., Owen, R., Pansera, M., Guston, D. H., Grunwald, A.,... & Ribeiro, B. Responsible innovation scholarship: normative, empirical, theoretical, and engaged. Journal of Responsible Innovation 2024, 11, 2309060. [CrossRef]

- Schumpeter, J. A., & Swedberg, R. The theory of economic development. Routledge, London, UK, 2021. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003146766.

- Lettice, F. , & Parekh, M. The social innovation process: themes, challenges and implications for practice. International Journal of Technology Management, 2010, 51(1), 139-158. [CrossRef]

- Phills, J. A. , Deiglmeier, K., & Miller, D. T. Rediscovering social innovation. Stanford Social Innovation 2008, 6, 34–43. [Google Scholar]

- Parth, S. , Manoharan, B., Parthiban, R., Qureshi, I., Bhatt, B., & Rakshit, K. Digital technology-enabled transformative consumer responsibilisation: A case study. European Journal of Marketing, 2021, 55(9), 2538-

34 2565. [CrossRef]

- Qureshi, I. , Pan, S. L., & Zheng, Y. Call for papers: Digital social innovation. Information Systems Journal, 2017, 1-8.

- Bolz, K. , & de Bruin, A. Responsible innovation and social innovation: toward an integrative research framework. International Journal of Social Economics, 2019, 46(6), 742-755. [CrossRef]

- Rühli, E. , Sachs, S., Schmitt, R., & Schneider, T. Innovation in multistakeholder settings: The case of a wicked issue in healthcare. Journal of Business Ethics 2017, 143, 289-305. [CrossRef]

- Finholt, T. A. Collaboratories. Annual Review of Information Science and Technology 2002, 73-107. University of Michigan, USA. [CrossRef]

- Finholt, T. A. Collaboratories as a new form of scientific organization. Economics of Innovation and New Technology 2003, 12(1), 5–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wulf, W.A. Improving Research Capabilities through Collaboratories. In Collaboratories: Improving Research Capabilities in Chemical and Biomedical Sciences. National Academy Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1999.

- Finholt, T. A. , & Olson, G. M. From laboratories to collaboratories: A new organizational form for scientific collaboration. Psychological Science 1997, 8, 28-36. [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.; Leminen, S.; Westerlund, M. A systematic review of living lab literature. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 213, 976–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Network of Living Labs (ENoLL). What Are Living Labs. Available online: https://enoll.org/living-labs/ (accessed on 19 February 2025).

- Nguyen, H.T. , Marques, P., & Benneworth, P. Living labs: Challenging and changing the smart city power relations? Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2022, 183, 121866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fauth, J. , De Moortel, K., & Schuurman, D. Living labs as orchestrators in the regional innovation ecosystem: a conceptual framework. Journal of Responsible Innovation, 2024, 11, 2414505. [CrossRef]

- Byrne, T. , Murray, N., McDonnell-Naughton, M., & Rowan, N. J. Perceived factors informing the pre-acceptability of digital health innovation by aging respiratory patients: a case study from the Republic of Ireland. Frontiers in Public Health 2023, 11, 1203937. [CrossRef]

- Fotis, T. , Kioskli, K., Sundaralingam, A., Fasihi, A., & Mouratidis, H. Co-creation in a digital health living lab: a case study. Frontiers in Public Health 2023,10, 892930. [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, A. S. , Sahay, S., Kumar, R., Banta, R., & Joshi, N. “A living lab within a lab”: approaches and challenges for scaling digital public health in resource-constrained settings. Frontiers in Public Health 2023, 11, 1187069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viano, C. , Tsardanidis, G., Dorato, L., Ruggeri, A., Zanasi, A., Zgeras, G.,... & Vlachokyriakos, V. Living labs for civic technologies: a case study. Community infrastructuring for a volunteer firefighting service. Frontiers in Public Health 2023, 11, 1189226. [CrossRef]

- Mačiulienė, M. , & Skaržauskienė, A. Sustainable urban innovations: digital co-creation in European living labs. Kybernetes 2020, 49, 1969-1986. [CrossRef]

- Ballon, P. , Van Hoed, M., & Schuurman, D. 20. The effectiveness of involving users in digital innovation: Measuring the impact of living labs. Telematics and Informatics. 2018, 35(5), 1201-1214. [CrossRef]

- Berberi, A. , Beaudoin, C., McPhee, C., Guay, J., Bronson, K., & Nguyen, V. M. Enablers, barriers, and future considerations for living lab effectiveness in environmental and agricultural sustainability transitions: a review of studies evaluating living labs. Local Environment, 2023, 1-19. [CrossRef]

- Beaudoin, C. , Joncoux, S., Jasmin, J. F., Berberi, A., McPhee, C., Schillo, R. S., & Nguyen, V. M. A research agenda for evaluating living labs as an open innovation model for environmental and agricultural sustainability. Environmental Challenges 2022, 7, 100505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronson, Kelly, Rachana Devkota,; Vivian Nguyen. Moving toward generalizability? A scoping review on measuring the impact of living labs. Sustainability 2021, 13(2), 502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, I. , & Marín-González, E. Renewable energy Living Labs through the lenses of responsible innovation: Building an inclusive, reflexive, and sustainable energy transition. Journal of Responsible Innovation 2023, 10(1), 2213145. [CrossRef]

- Torres Kompen, R. , Casanovas, R., Serra, A., Moreno, D., Solano, D., Bezos, C., Fernández, I., & Martínez, S. Age is not a barrier: SeniorLab, an innovative project-based approach to learning for senior citizens. EDULEARN09 Proceedings 2009, pp. 900-901.

- Benavent, J. , Colobrans, J., Marí, S., & Colomé, J.M. Lessons learned from users: The development of the LivingLab4carers platform case. Proceeding of the 17th International Conference on Concurrent Enterprising, ICE, 2011 1-8.

- Gray, M. , Mangyoku, M., Serra, A., Sánchez, L., & Aragall, F. Integrating Design for All in Living Labs. Technology Innovation Management Review 2014, 4, 50-59. [CrossRef]

- Serra, A. Three problems concerning Living Labs: A European point of view. CTS Journal 2013, 23(8), 283–298. [Google Scholar]

- Leminen, S. , Westerlund, M., Sánchez, L., & Serra, A. Chapter 13: Users as content creators, aggregators and distributors at Citilab Living Lab. In International Perspectives on Business Innovation and Disruption in the Creative Industries. Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2014.

- Molinari, F. , Concilio, G., Mulder, I., Torntoft, L. K., Aguilar, M. Hack The Government! Empowering

126 Citizens to Make Meaningful Use of OpenData. In CeDEM16 Proceedings of the International Conference for E-Democracy and Open Government.; Edition Donau-Universität Krems: Krems, Austria, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Morelli, N. , Mulder, I., Concilio, G., Pedersen, J., Jaskiewicz, T., Götzen, A. D., & Aguilar, M. (2017). “Open Data as a New Commons: Empowering citizens to make meaningful use of a new resource”. In Internet Science: 4th International Conference, INSCI. Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017.

- Serra, A. Next generation community networking: Futures for Digital Cities. In Kyoto Workshop on Digital Cities Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1999; pp. 45–57.

- Serra, A. Citizen networks: Building new societies of the digital age. GlobalCN 2000, Barcelona, Spain, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Mazzucato, M. The entrepreneurial state. Soundings 2011, 49(49), 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colobrans, J. , & Serra, A. “Technoanthropology in the "Colaboratorio 1.0" research and innovation program”. Ichan Tecolotl, 2021, núm. 352, Especial Tecnantropología y Tecnosociología. Conacyt, CIESAS.

140 México.

- We are Social. Digital 2024: 5 billion social media users. Available online: https://wearesocial.com/us/blog/2024/01/digital-2024-5-billion-social-media-users/ (accessed on 23 March 2025).

- Følstad, A. Living labs for innovation and development of information and communication technology: A literature review. Special Issue on Living Labs. Electron. Virtualness 2008, 10, 99–131. [Google Scholar]

- Bergvall-Kåreborn, B. , Eriksson, C.I., Ståhlbröst, A., & Svensson, J. A milieu for innovation: Defining living labs. In ISPIM Innovation Symposium. Halmstad University: Halmstad, Sweden, 2009.

- Serra, A. Is a Universal Innovation System Possible? Barcelona Metròpolis 2014, Nº 93. Available online: https://www.barcelona.cat/bcnmetropolis/2007-2017/en/dossier/es-possible-un-sistema-universal-dinnovacio/ (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Serra, A.; Citizen Labs: Basis for Universal Innovation Ecosystems. SPOKES (Ecsite) 2018, 45. Available online: https://www.ecsite.eu/activities-and-services/news-and-publications/digital-spokes/issue-45 (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Canseco-Lopez, F. , Serra, A., & Martorell Camps, M. Opening Our Innovation Ecosystems to All: The INTEGER Project Case Study. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1164. [CrossRef]

- Tashakkori, A. Sage handbook of mixed methods in social & behavioral research. SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2010.

- Glesne, C. Becoming qualitative researchers: An introduction. Pearson. One Lake Street, Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2016.

- Patton, M. Q. Qualitative research. Encyclopedia of statistics in behavioral science. Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2005.

- Bryman, A. Social research methods. Oxford University Press, UK, 2016.

- Given, L. M. The Sage encyclopedia of qualitative research methods. SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008.

- Edmonds, W. , & Kennedy, T. (2016). Convergent-parallel approach. In An applied guide to research designs: quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods. Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2016.

- Collier, D. , & Mahoney, J. Insights and pitfalls: Selection bias in qualitative research. World Politics, 1996,

171 49(1), 56-91.

- Glaser, B. , & Strauss, A. Discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Routledge. Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2017.

- Busetto, L. , Wick, W., & Gumbinger, C. How to use and assess qualitative research methods. Neurological Research and Practice 2020, 2(1), 14. [Google Scholar]

- Ponto, J. Understanding and evaluating survey research. Journal of the Advanced Practitioner in Oncology 2015, 6(2), 168–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sutton, J. , & Austin, Z. Qualitative research: Data collection, analysis, and management. The Canadian Journal of Hospital Pharmacy 2015, 68, 226. [CrossRef]

- Elo, S. , & Kyngäs, H. The qualitative content analysis process. Journal of Advanced Nursing 2008, 62(1), 107–115. [Google Scholar]

- Lindberg, M. , Lindgren, M., & Packendorff, J. Quadruple helix as a way to bridge the gender gap in entrepreneurship: the case of an innovation system project in the Baltic Sea Region. Journal of the Knowledge Economy 2014, 5(1), 94-113. [CrossRef]

- Schütz, F. , Heidingsfelder, M. L., & Schraudner, M. Co-shaping the future in quadruple helix innovation systems: uncovering public preferences toward participatory research and innovation. She Ji: The Journal of Design, Economics, and Innovation 2019, 5(2), 128-146. [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Advanced digital technologies. 2024. Available online: https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/policies/advanced-digital-technologies (accessed on 23 March 2025).

- Generalitat de Catalunya. El Govern crea la xarxa CatLabs per potenciar el talent en matèria d’innovació a Catalunya. 2016. Avaible online: https://govern.cat/salapremsa/acords-govern/6901/govern-crea-xarxa-catlabs-potenciar-talent-materia-innovacio-catalunya (accessed 29 March 2025).

- Generalitat de Catalunya. Carta catalana per als drets i les responsabilitats digitals. 2019. Available online: https://politiquesdigitals.gencat.cat/ca/ciutadania/drets-responsabilitats/carta/digital-rights-and-responsibilities/charter-for-digital-rights-and-responsibilities-from-catalonia/ (accessed on 29 March 2025).

- Generalitat de Catalunya. Digital and territorial social innovation strategy.2022. Available online: https://politiquesdigitals.gencat.cat/ca/ciutadania/innovacio-social-digital/index.html#googtrans(ca|en) (accessed on 29 March 2025).

- Generalitat de Catalunya. National Strategy for socio-digital inclusion. 2024. Available online: https://politiquesdigitals.gencat.cat/ca/ciutadania/drets-responsabilitats/estrategia-nacional-per-a-la-inclusio-socio-digital/index.html#googtrans(ca|en) (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Blanckaert, E.; Hallström, L.; Jennes, I.; Van den Broeck, W. What Could Possibly Go Wrong? Exploring Challenges and Mitigation Strategies of Applying a Living Lab Approach in an Innovation Project. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Internet Society. The Internet is for everyone. 1999. Available online: https://isoc-e.org/the-internet-is-for-everyone/ (accessed on 29 March 2025).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).