1. Introduction

Lontar, a traditional writing material crafted from the leaves of the palm tree [

1] holds a significant place in various cultures, especially in Indonesia. This unique medium is traditionally used to inscribe important texts, encompassing religious writings, literature, and local knowledge. The manuscripts created on palm leaves serve as a treasure trove of wisdom, containing insights into medicine, astronomy, mathematics, and astrology knowledge that has illuminated humanity for centuries [

2,

3]. Furthermore, Lontar manuscripts provide a window into the socio-cultural dynamics and genealogical histories of their time [

4].

In regions like Orissa, these palm leaf manuscripts are intimately woven into daily rituals and regarded as sacred objects. They are often stored close to household deities and employed in various ceremonies. Similarly, in southern Laos, such manuscripts are tied to oral traditions and ritual histories, which help validate cultural identities [

5].

However, palm leaf manuscripts face numerous threats from environmental factors, handling, and storage conditions. Issues like ink peeling and physical degradation jeopardize their endurance [

4]. To safeguard these invaluable texts, digitization has become essential. This process involves using a variety of techniques such as scanning, photography, and advanced image processing to convert the manuscripts into digital formats [

4]; [

5]; [

6]. Nevertheless, making this transition is complex due to the manuscripts' deterioration over time and the need for significant digital storage space [

4]

Many of these palm leaf manuscripts were composed in ancient scripts and languages that are not easily understood today. For instance, Balinese texts are written in intricate scripts like Kawi and Sanskrit, rendering them difficult to access for the general populace [

7]. Similarly, ancient Tamil manuscripts present challenges in terms of character recognition and interpretation [

8]. In response, efforts are underway to develop systems for transliterating and recognizing these ancient scripts, aiming to enhance accessibility. Notable initiatives include a rule-based machine for transliterating Balinese script and a recognition system for ancient Tamil characters, which endeavor to aid in the understanding and preservation of these historic texts [

7,

9]. The Balinese lontar manuscript, written on palm leaves, is an important cultural heritage that faces the challenge of preservation. Digitization efforts aim to protect these fragile documents from physical damage [

10,

11,

12]. To address this problem, initiatives such as lontar festivals, writing classes, and exhibitions have been implemented to revitalize interest in Balinese scripts and scripts (Darma & Sutramiani, 2019). During the COVID-19 pandemic, virtual "babat lontar" activities have been held to continue dissemination efforts. Technological advancements, such as digital image processing and character recognition algorithms such as Linear Discriminant Analysis, were used to reconstruct and preserve the Balinese script from deteriorated palm manuscripts). This multifaceted approach aims to balance preservation with accessibility and cultural sustainability.

The palm manuscript culture in Bali faces challenges due to modernization and digitization, while digitization offers preservation benefits, it also presents obstacles such as limited language proficiency and scripting knowledge among users [

13]. The decline in the interest of younger generations in lontar manuscripts is attributed to their physical appearance, difficult language, and limited accessibility [

10]. However, lontar remains valuable because of the spiritual, cultural, and educational content it provides, including teachings on Hinduism and ethics [

14]. Despite these challenges, a recent mapping study revealed the existence of 25,106 lontar manuscripts in nine districts in Bali, with Gianyar Regency having the largest [

15]. To address the declining popularity, efforts are being made to re-popularize the lontar tradition through festivals, writing classes, and exhibitions, aiming to create a more inclusive and integrative preservation program [

16].

The digital revolution has transformed the cultural and creative sectors, leading to new forms of representation of cultural heritage and fostering creative capacity [

17]. Open innovation, facilitated by digital technologies, can enhance the creative processes associated with cultural heritage, making it more accessible and engaging [

17]. The sustainability of Bali's intangible cultural heritage, such as hand-woven textiles, is influenced by local genius, place identity, and cultural policy. These factors support the integration of traditional practices with modern economic activities. Endek Bali's weaving industry, which is showcased at international events such as the G20 Summit, highlights the role of cultural diplomacy and the creative economy in promoting local heritage on the global stage [

16]. Effective cultural policies can moderate the relationship between creative economy activities and the sustainability of cultural heritage. This is especially important for areas that specialize in traditional cultural industries [

18]

The digitization of Balinese lontar manuscripts is essential for preserving cultural heritage, but faces challenges such as cultural entropy and declining language skills [

20]. To address this problem, innovative approaches such as augmented reality applications have been developed to make lontar more accessible and attractive to the younger generation [

19] While digitalization offers benefits in preservation (To balance preservation and modernization, collaborative efforts between cultural preservation, artists, and technology developers are essential. These efforts can include creating an online platform to share and digitize throws, organizing festivals, and holding regular writing classes to maintain traditions [

20]. Such initiatives aim to ensure that the wisdom contained in the palm remains relevant and accessible in the digital age.

Gap Research

Furthermore, economic factors also play a role in reducing interest in the lodging. The process of making and processing palm leaves requires time and skills that are considered not promising profits. With high costs and difficulties in obtaining quality materials, many people choose not to continue this tradition. This gap creates challenges for cultural preservationists who strive to maintain the continuity of traditions that are considered the roots of Balinese identity. Innovative solutions are needed to bridge this gap, by integrating an open innovation approach in an effort to preserve palm culture [

21,

22]. The involvement of young people in creative and collaborative projects can help rekindle interest in palm trees [

23]. For example, training programs that utilize modern technology to teach lontar writing techniques and Balinese script can increase the accessibility and relevance of this culture in everyday life. Thus, it is hoped that the lontar culture is not only seen as a heritage of the past but also as an integral part of the future identity of the Balinese people.

The preservation of palm oil manuscripts in Bali faces various challenges, especially due to modernization and digitalization that are changing the way people interact with this cultural heritage. The decline in accessibility and understanding among the younger generation is a major concern, so efforts are needed to restore interest in the throw. In this context, technology, such as augmented reality, offers the potential to improve understanding and interaction with the lunar manuscript, making it more engaging and accessible. In addition, the involvement of local communities is very important in preservation and education efforts, so that they have knowledge and traditions that can be maintained and developed. The economic implications of preserving the palm manuscript are also significant, with opportunities to create a source of income through cultural tourism. Innovative solutions that bridge the gap between tradition and modernity can help ensure the sustainability of palm oil preservation in the future.

This research aims to analyze the various challenges faced in the preservation of lontar manuscripts in Bali, including the impact of modernization and digitalization. In addition, this research will explore strategies that can be used to restore the interest of the younger generation in the tradition of lontar, which is increasingly threatened by the changing times. The effectiveness of the use of technology, such as digitization and interactive applications, will be evaluated to determine how it can improve public accessibility and understanding of the palm manuscript. The role of local communities was also identified as an important factor in the preservation and education related to lotar, given the traditional knowledge they have. Finally, this research will investigate the economic implications of the preservation of the lontar and propose innovative solutions that can support the sustainability of this tradition in the future.

Literature Review

Open Innovation Theory

Open Innovation (OI), involves breaking down barriers between a company and its external environment, allowing for the transfer of innovation both inward and outward [

24,

25]. It leverages external sources such as other companies, consumers, and communities to improve the innovation process [

24,

26]. OI promotes the creation of an open innovation ecosystem where benefits are shared among all participants, including partners and customers 6. This concept integrates a variety of collaborative features into a consistent innovation management process [

25]. Combining the inflow and outflow of knowledge, collaborative innovation is at the core of OI, emphasizing knowledge sharing and co-creation [

27,

28]. Leveraging crowdsourcing communities allows companies to leverage consumers' collective intelligence for new product development [

29,

30]. OI has been successfully implemented in high-tech industries, but its adoption in other sectors is still under-researched [

1]. SMEs face difficulties in adopting OI due to limited resources and the need for a supportive organizational culture [

28,

31]. Effective collaboration requires overcoming resource limitations and developing strong communication skills [

32].

Open Innovation Ecosystem in Cultural Heritage

The Open Innovation Ecosystem integrates multiple actors-universities, industries, governments, and communities-working collaboratively to generate and diffuse innovation. This approach aligns with the Quadruple Helix Model, where knowledge flows dynamically among the four [

33,

34,

35]. Within the context of cultural heritage, OIE emphasizes co-creation and shared responsibility in digital preservation. Universities provide research and technological development, industries contribute funding and commercialization capabilities, governments establish policy frameworks, and local communities ensure the authenticity and continuity of traditional knowledge.

Ref [

36,

37], highlsight that open innovation ecosystems in heritage sectors promote inclusive innovation by enabling both knowledge inflow and knowledge outflow. Knowledge inflow occurs when academic and technological expertise enters community practices, while knowledge outflow refers to the transformation of traditional knowledge into creative digital products, tourism experiences, and global cultural promotion. This ecosystemic collaboration ensures that innovation in cultural heritage remains sustainable, adaptive, and culturally embedded. It transforms traditional conservation efforts into an integrative model of innovation, education, and cultural entrepreneurship.

Cultural Evolution Theory

Cultural evolution is seen as a Darwinian process involving variation, competition, and inheritance, similar to genetic evolution but with different mechanisms. Culture is defined as socially transmitted information, which develops through processes analogous to natural selection [

38,

39]. Cultural evolution operates at the micro (individual behavior and decisions) and macro (population-level dynamics) levels, often requiring a multi-level approach to fully understand interactions. Human psychology supports high-fidelity social learning through mechanisms such as imitation, teaching, and intentionality, which are essential for the transmission of cultural traits [

39,

40]. This theory has been applied to understand economic behavior and the evolution of social systems, highlighting the interaction between cultural and biological evolution in shaping human society [

41,

42].

Open Innovation for Cultural Sustainability

The integration of Open Innovation [

32,

36] with Cultural Sustainability [

1], creates a holistic framework for preserving and revitalizing cultural heritage in the digital age. Open Innovation encourages the free flow of ideas and collaboration among multiple actors-universities, communities, governments, and industries-facilitating co-creation and shared knowledge for sustainable cultural development.

The conceptual pathway can be expressed as:

Through this integrative model, knowledge generated in academic and creative environments flows toward communities and is transformed into digital heritage products that strengthen cultural identity while enhancing global accessibility [

37]. At the same time, cultural knowledge from communities enriches innovation processes, ensuring that technological progress aligns with cultural authenticity. This circular knowledge exchange strengthens the sustainability of heritage management systems and creates socio-economic value for local communities.

Conservation Challenges and Interest of the Younger Generation

Proper storage conditions are essential for preserving the lontar manuscript. This includes maintaining appropriate air temperature and humidity levels to prevent damage [

51]. Regular cleaning with special chemicals is necessary to prevent the fading of the text on the lontar manuscript [

52]. Efforts such as reforming and reproducing the lontar manuscript are essential to ensure its longevity [

53]. The preservation of physical materials such as palm oil manuscripts often faces challenges due to irreplaceable materials and the need for specialized conservation techniques [

54]. Conservation efforts can consume a lot of resources, requiring financial investment and skilled personnel [

51,

52]. There is often a gap between the younger generation and traditional cultural practices, which can lead to a lack of interest in preserving the heritage [

53]. To foster interest among youth, it is important to integrate cultural heritage into modern contexts, such as through educational programs and community-driven activities [

48]. The preservation of physical materials such as palm oil manuscripts often faces challenges due to irreplaceable materials and the need for specialized conservation techniques [

49]. Conservation efforts can consume a lot of resources, requiring financial investment and skilled personnel [

54,

55].

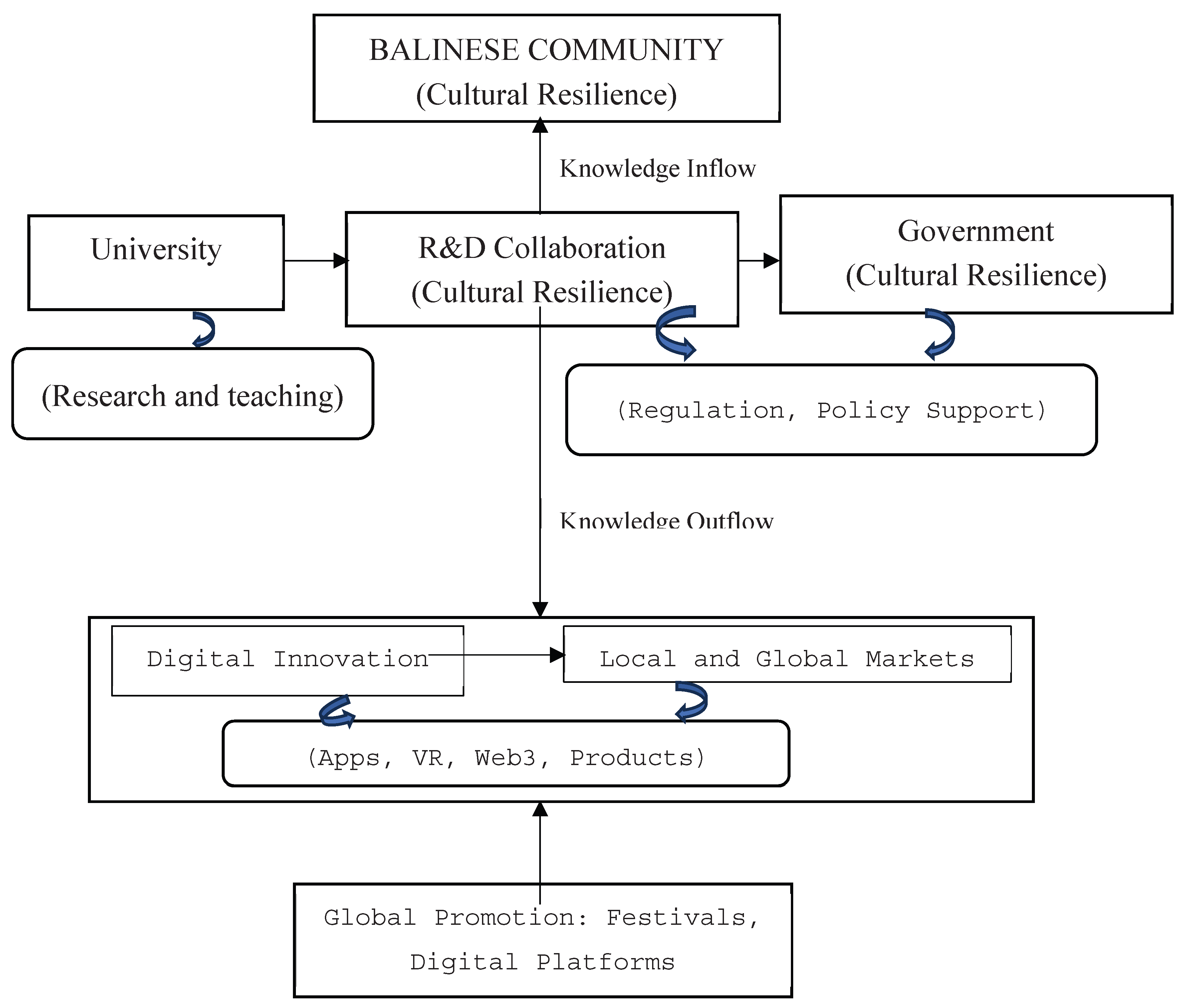

Figure 1. illustrates how various parties, including universities, the government, and the Balinese community, collaborate within an open innovation ecosystem to preserve and develop Balinese culture through digital technology. Universities and the government incorporate knowledge from research, teaching, and regulatory and policy support into collaborative research and development (R&D) processes focused on cultural resilience. The Balinese community contributes local wisdom and cultural heritage, which serve as the primary source of cultural content. This collaboration generates digital innovations in the form of applications, virtual reality (VR), Web3 technology, and other digital cultural products, which are then marketed both locally and globally. Furthermore, Balinese culture is widely promoted through festivals and digital platforms, strengthening preservation while expanding its reach internationally.

Local Community Involvement and Economic Implications in Cultural Preservation

The involvement of local communities significantly increases the conservation of cultural heritage sites. Active participation in decision-making and oversight leads to better maintenance and protection of both tangible and intangible aspects of heritage [

56,

57]. Incorporating indigenous knowledge and traditions into conservation strategies ensures culturally relevant and sustainable outcomes [

48]. People who live near historic structures often feel a strong attachment and obligation to preserve their cultural heritage, which can be leveraged to enhance preservation efforts [

58]. This approach can act as a double-edged sword, preserving cultural heritage while creating new economic opportunities [

59]. A well-managed cultural heritage can encourage local economic development through tourism. Sustainable tourism practices involving local communities can result in increased tourism revenue and net profit, while maintaining cultural integrity [

57,

60]. Cultural heritage can inspire creativity, which in turn produces indirect positive effects on local economhic development. This relationship justifies new policy recommendations that support cultural heritage as a driver of economic growth [

49]. Effective incentives are essential to stimulate the involvement of local communities in heritage conservation. Sustainable management of cultural heritage requires a balance of economic benefits with ecological management and cultural integrity. Collaborative efforts involving government, the private sector, and local communities are key to achieving comprehensive benefits with innovation [

37,

50,

53]

The Role of Technology and Community Involvement in Cultural Heritage Preservation

Community involvement is essential for effective cultural heritage conservation. Active participation by local communities leads to a substantial increase in conservation outcomes, as it ensures the preservation of both tangible and intangible heritage aspects [

61]. Involving local communities in decision-making processes and oversight roles helps to maintain the integrity and cultural values of heritage sites. This approach aligns conservation efforts with local traditions and knowledge, making it more sustainable and culturally relevant [

56,

58]. Community-based monitoring, such as participatory monitoring at the Bisotun World Heritage Site, allows locals to systematically report and record issues, contributing to the sustainable management of heritage properties [

59]. Advanced technologies such as 3D laser scanning, multispectral imaging, and high-resolution photography are essential for documenting and investigating cultural heritage sites. Combining community engagement with technological advances creates a robust framework for heritage conservation. For example, the integration of Building Information Modelling (BIM) with community participation supports sustainable urbanization and heritage tourism [

60]. Educating the public and stakeholders on the use of digital technology in heritage conservation is essential. Training programs and workshops can bridge the digital divide and empower local communities to make effective use of these technologies [

60].

State of the Art

Approaches and methodologies using a qualitative approach to understand the culture of palm oil in depth, by involving direct observation and interviews with key informants. This method is based on theoretical frameworks that have been discussed in the literature, such as Open Innovation Theory and Community Participation Theory, which provide a basis for identifying challenges and solutions in the conservation of the land. In addition to digitalization being one of the main focuses, highlighting the importance of community involvement in cultural preservation, empowering communities through training programs and cultural initiatives, this research seeks to create bridges between theory and practice, as well as show how traditional knowledge can be preserved. Thus, this research not only adds new insights, but also reinforces existing findings. The integration of innovation and technology, including the use of digital applications, shows how modern approaches can be applied to improve understanding and accessibility of palm trees [

62].

Research Methods

This research uses a qualitative approach to understand the phenomenon of palm culture in depth. This approach allows researchers to explore the experiences, views, and practices of the community related to the tradition of writing lontar. Researchers will be directly involved in activities related to the writing of lontar, including the process of making, storing, and reading lontar manuscripts. This observation is expected to provide insight into the practices and challenges faced by lontar writers. Interviews will be conducted with key informants, such as lontar writers, teachers, and community leaders who have knowledge of the lontar tradition. This interview aims to explore the views of the figures regarding the preservation of the lontar culture and the existing challenges. The research will involve a literature review related to the history, process, and cultural value of the lontar. This includes historical documents, academic articles, and relevant literary works.

The collected data will be analyzed using a Hermeneutics approach, where this process involves the interpretation of the meaning of the data obtained, both from observation and interviews. The researcher will identify the main themes that emerge and relate them to the established theoretical framework. The analysis used is Triangulation to ensure the validity of the data by comparing data from various sources (observations, interviews, and literature studies). In addition, researchers can also conduct member checking with informants to ensure that the interpretations made are in accordance with the experiences experienced by the figures (informants). The results of the research will be presented in the form of a narrative that describes the dynamics of the lontar culture, the challenges faced, and recommendations for conservation. The data will also be supplemented with relevant photos or illustrations to support the reader's understanding.

Data Analysis Procedures

Thematic analysis was applied following the six phases proposed by [

63] (1) familiarization with the data, (2) generating initial codes, (3) searching for themes, (4) reviewing themes, (5) defining and naming themes, and (6) producing the final report. These steps guided the interpretation of qualitative data obtained from interviews, observations, and documents. Each transcript was coded manually to identify key concepts related to cultural sustainability and open innovation in digital heritage.

Data Validation and Triangulation

To ensure trustworthiness, member checking was conducted by sharing interpreted summaries with informants to confirm accuracy and credibility. A triangulation matrix was used to cross-verify themes emerging from interviews, observations, and document analysis.

Table 1.

Triangulation Matrix.

Table 1.

Triangulation Matrix.

|

Source

|

Key Findings

|

Validation Method

|

Notes

|

|

Interview (Informants 1–3)

|

Cultural challenges, youth engagement |

Member checking |

All informants confirmed interpretation accuracy |

|

Observation

|

Community workshops, digital scanning |

Data triangulation |

Consistent with interview findings |

|

Document Review

|

Policy and digital archives |

Theoretical triangulation |

Reinforces the framework of Open Innovation Ecosystem |

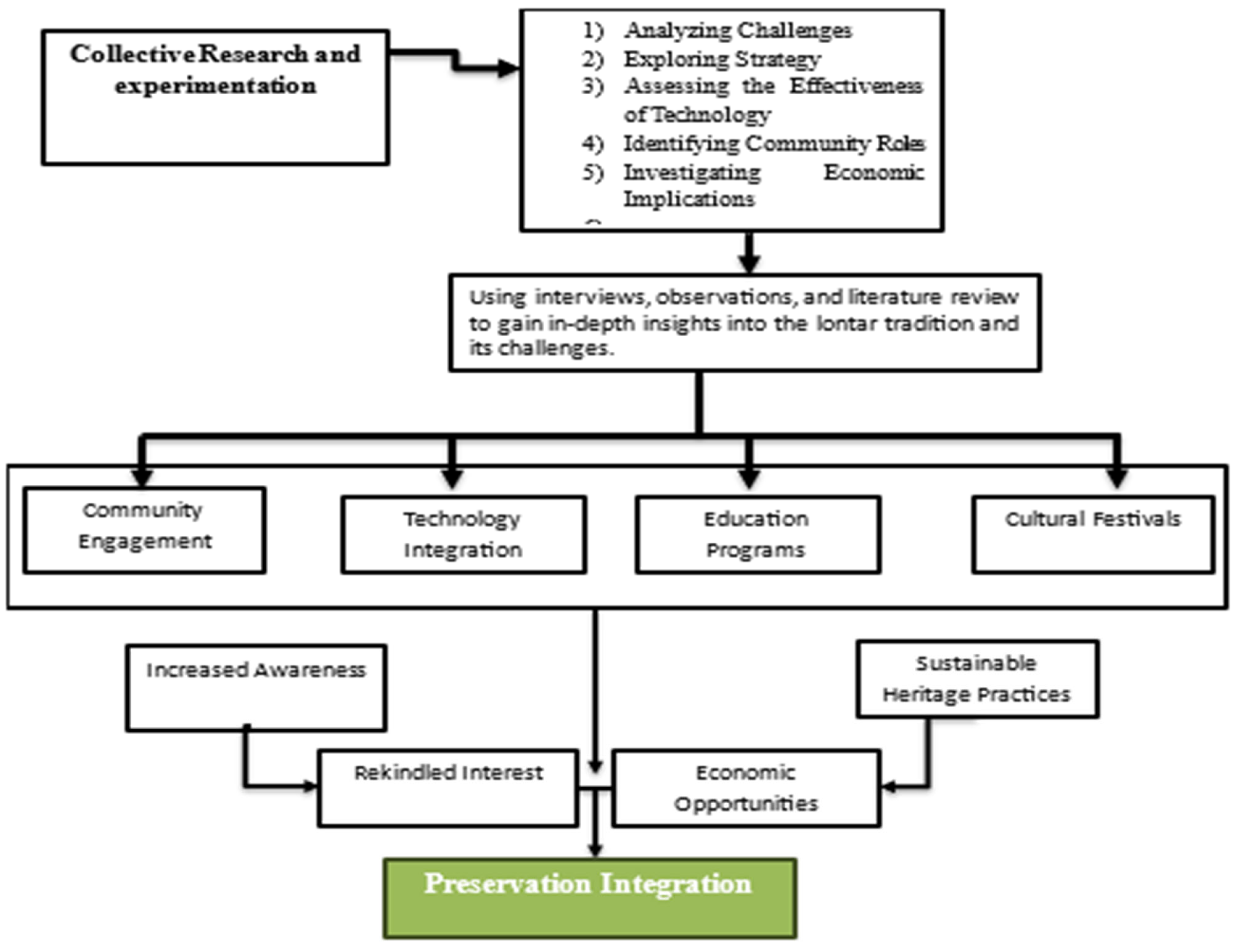

Figure 2. This project demonstrates the integration of palm leaf preservation through collaborative research, interviews, and observations, resulting in four focuses: community engagement, technology integration, educational programs, and cultural festivals. These four focuses foster awareness, interest, economic opportunities, and sustainable heritage practices toward the ultimate goal of preservation integration.

Results and Discussion

Result

In obtaining the sharpness of the results related to previous findings and the problems faced. Data collection is carried out using a Hermeneutics approach, involving the interpretation of figures who have knowledge in terms of Cultural Heritage (Lontar), both from observation and interviews. The three figures mentioned in this study are; Cultural Researcher, Cultural Activist, and Artist.

Table 2. summarizes information about three interviewees regarding the preservation and development of Balinese culture, particularly lontar. Each interviewee had a distinct role—cultural researcher, cultural activist, and artist—and came from different locations in Bali. The interviews varied in duration, from 55 to 75 minutes. The interviews covered a range of important aspects, from the challenges of digitally preserving lontar, the role of the younger generation and technology in disseminating lontar, to the integration of lontar aesthetics into modern art and education. This table provides a comprehensive overview of the perspectives and contributions of various parties in efforts to preserve Balinese culture.

Challenges 38. [

39,

40]. Some figures also mentioned that limited access to lontar manuscripts and lack of education about lontar in schools are significant obstacles. The second figure highlights that language barriers and lontar reading skills are barriers to understanding and appreciating the manuscript. This relates to the Theory of Community Participation, which emphasizes the importance of education and community involvement in preserving the culture of the lontar [

44,

46,

48]. Without adequate access and good understanding, the younger generation will find it difficult to engage in cultural preservation [

50,

56].

While digitization offers benefits in terms of preservation, the second figure cautions that this process can also reduce the sense of appreciation for physical manuscripts. This creates a tension between preservation and modernization. According to the Open Innovation Theory, collaboration between various parties—including academics, practitioners, and local communities—is needed to find innovative solutions that can maintain a balance between preserving traditions and applying new technologies [

24,

33,

36]. The involvement of local communities in the preservation of lontar manuscripts has been stated as one of the potential solutions. The first and third figures stated that the community must be empowered through training programs and workshops to understand and care for lontar. This is in accordance with the Theory of Community Participation, which emphasizes the importance of the active role of the community in the process of cultural preservation [

47,

48,

50]. By involving the community, preservation efforts become more inclusive and culturally relevant [

56,

58].

The figures also mentioned that economic challenges, such as high costs and difficulties in obtaining raw materials, may reduce interest in continuing this tradition. This shows the need for policies that support the integration of economic activities with cultural preservation. Open Innovation Theory suggests that collaboration between the public and private sectors can create innovative solutions that provide economic incentives for communities to engage in cultural preservation [

31,

33,

37,

49].

Local Community Involvement and Economic Implications in Cultural Preservation

The figures emphasized that the local community is at the forefront of the preservation of the lontar manuscript. The first figure stated that the community has very valuable traditional knowledge and can be involved in training programs and workshops. This is in line with the Theory of Community Participation, which emphasizes the importance of the active role of the community in cultural preservation [

44,

46,

48,

50]. Community involvement not only raises awareness but also ensures that knowledge and traditions remain alive and relevant [

56,

58].

The second figure mentioned that the preservation of palm trees can open up new economic opportunities, such as cultural tourism. This shows that cultural heritage not only has cultural value but can also contribute to the local economy. Creative Economy Theory asserts that culture can be a driver of economic growth, where tourism activities involving local communities can increase income and create jobs [

49,

53,

57]. When the community is involved in conservation, the community also gets direct economic benefits [

59].

While community engagement is crucial, some figures acknowledge that there are challenges, such as a lack of interest among the younger generation and support from the government. The third figure highlighted that the community needs to feel responsible for preserving their cultural heritage. This relates to the Theory of Community Engagement, which suggests that a sense of belonging and responsibility towards culture can encourage active participation [

47,

55,

58]. Therefore, creating programs that are engaging and relevant to the younger generation is essential.

The second figure also underlined the importance of collaboration between the government and the community. Cultural Policy Theory states that policies that support community involvement in a culture of preservation can produce more effective and sustainable outcomes [

49,

50,

54]. Programs that involve the community in decision-making and implementation of conservation activities can increase the legitimacy and ownership of cultural heritage [

45,

56].

Leaders agreed that innovations, such as the use of digital technology and cultural festivals, can attract public interest and increase engagement. Open Innovation Theory supports the idea that collaboration between various parties—including academics, artists, and society—can result in creative solutions that are relevant in cultural preservation [

24,

33,

36,

37]. By leveraging technology and creating a platform for knowledge sharing, communities can be more involved in conservation efforts [

32], [

59].

The Role of Technology and Community Involvement in Cultural Heritage Preservation

The figures agreed that technology plays a crucial role in the preservation of the lontar manuscript. The first figure stated that digitization allows for better storage and access to information about the land. Technology can help preserve cultural heritage through modern methods that reduce physical damage to documents. By using digital tools, the information contained in the lontar can be accessed by the younger generation, thus encouraging interest in learning more [

59]. The involvement of local communities, as expressed by the second figure, is very important in the preservation process. The community can play an active role in digitization activities, such as scanning manuscripts and organizing events that feature lontar. This is relevant to the Theory of Community Participation, which emphasizes that when people are involved in decision-making, they feel more responsible for cultural preservation [

44,

46,

48]. This involvement can also increase a sense of ownership and pride in their local cultural heritage [

50].

The third figure emphasized the importance of synergy between technology and community involvement. Projects that combine digital technology with training on lontar can provide opportunities for the community to learn as well as contribute. This is in line with Open Innovation Theory, which underlines that collaboration between various parties-academics, artists, and society—can lead to innovative solutions in cultural preservation [

24,

33,

36]. By creating an online platform or application, the public can participate in digitizing and disseminating knowledge about lontar. Technology can also be used as an effective educational tool. For example, a mobile application that provides information about lontar can attract the attention of the younger generation, as revealed by the second figure. This shows that the use of technology can increase public awareness and understanding of the importance of preserving cultural heritage [

37,

59]. Cultural education supports the idea that relevant education can increase people's interest in their own local culture, consistent with Cultural Evolution Theory, which explains that adaptive learning ensures cultural continuity amid modernization [

38,

39].

Despite the many benefits, some challenges are also faced in integrating technology. The first figure noted that while digitalization offers easier access, there are concerns about the loss of traditional practices. This reflects the need to maintain equilibrium between innovation and tradition—an idea central to Open Innovation for Cultural Sustainability [

31,

49]. Therefore, it is important to find a balance between the use of technology and the preservation of traditional practices.

Open Innovation Ecosystem for Balinese Cultural Heritage

The findings of this study indicate that cultural preservation in Bali can be strengthened through the design of an Open Innovation Ecosystem (OIE) that connects communities, government, universities, and private sectors. This aligns with the Quadruple Helix model, where innovation emerges from collaborative interactions between different social actors [

1,

33,

64]. In this ecosystem, universities act as the source of research, digital preservation, and technological development; communities function as custodians of cultural knowledge and traditions; government institutions provide enabling policies and cultural protection frameworks; while the private sector facilitates commercialization, funding, and dissemination through creative industries and digital platforms.

This integrative collaboration enables knowledge inflow where scientific and technological inputs enhance cultural digitization and knowledge outflow where local knowledge is transformed into creative digital products and cultural innovations that reach global audiences. The dynamic circulation of knowledge creates sustainable value, reinforcing both cultural identity and economic vitality in Bali. Furthermore, the OIE framework fosters collective innovation capacity that promotes cultural resilience, inclusivity, and global competitiveness. It supports the transition of Balinese heritage preservation from isolated conservation efforts into a living innovation system where knowledge, technology, and tradition continuously co-evolve.

Furthermore, this study concludes that the preservation of Balinese cultural heritage requires a systemic design of an Open Innovation Ecosystem involving universities, communities, governments, and private industries. This collaboration fosters continuous knowledge circulation-from research and digital innovation to cultural practice and market dissemination-ensuring that traditional wisdom and technological innovation coexist in a sustainable and adaptive system. The establishment of such an ecosystem will position Bali as a living laboratory for digital cultural heritage innovation that integrates education, policy, and creative economy.

The integration of empirical findings with Open Innovation dimensions highlights how community practices, technological development, and institutional collaboration form a coherent ecosystem.

Table 3 demonstrates how empirical themes observed in Bali’s cultural preservation align with the core dimensions of Open Innovation-

inbound, outbound, and

coupled processes [

33,

34] This connection strengthens the theoretical foundation of the study and underscores its contribution to understanding open innovation in cultural heritage contexts.

Conclusions

This research reveals that the preservation of lontar manuscripts in Bali faces various challenges, especially due to modernization and digitalization. While digitalization offers benefits in terms of accessibility and preservation, there are concerns about the loss of traditional practices and a decline in the interest of younger generations. The involvement of local communities has proven crucial in conservation efforts. Not only do communities have valuable traditional knowledge, but they can also play an active role in conservation activities, such as training programs and workshops. It demonstrates the importance of collaboration between society, government, and the private sector to create innovative and sustainable solutions.

The dynamics of lontar culture in Bali show that the tradition of writing lontar is increasingly threatened by the development of modern media and changes in people's mindsets. Although there is still awareness of the value of the lontar culture, the interest of the younger generation to learn and pass on this tradition has decreased drastically. Factors such as the ease of access to digital media, lack of skills in writing lontar and the dominance of the Latin script contributed to the loss of this practice. Therefore, there is an urgent need to integrate education about lontar in the school curriculum, as well as involve the community in conservation efforts through various cultural activities.

The economic implications of palm oil conservation are also significant, with the potential to increase income through cultural tourism. A well-managed cultural heritage can create jobs and support the local economy. Overall, this study emphasizes the need for an inclusive and integrative approach in preserving lontar manuscripts, by utilizing technology and empowering the community. In this way, it is hoped that the lontar tradition can not only be preserved, but also become an important part of the identity and life of the Balinese people in the future.

Suggestion

Steps that must be considered in preserving Lontar which has become a local culture are: 1) Educational Integration: The education sector in Bali can include materials related to Lontar and Balinese script in the curriculum. This lesson can help build the interest and understanding of the younger generation in the cultural heritage of the lontar; 2) Holding Training and Workshops: The organization of training and workshops on lontar writing techniques and the use of Balinese script is very important. This activity can involve community leaders, cultural activists, and academics to share knowledge and skills; 3) The existence of Cultural Buddhist Festivals: Holding cultural festivals and events that celebrate lontar and its writing traditions can increase public awareness and enthusiasm. This activity can be a platform to promote the importance of preserving the palm culture; 4) Stakeholder Synergy: Closer collaboration is needed between the government, educational institutions, and local communities to create programs that support the culture of palm preservation. Through this cooperation, resources can be used to the maximum to achieve conservation goals; 5) Adoption of the Use of Technology: Utilizing digital technology to document and distribute knowledge about palm trees can help reach a wider audience. For example, creating an online platform that provides information, tutorials, and resources related to lontar writing.

Research Implications

This research highlights the significance of designing a collaborative ecosystem that connects multiple stakeholders within the framework of Open Innovation Ecosystem and Quadruple Helix collaboration. Emphasizing the need to integrate materials about lontar and Balinese script in the educational curriculum. This can increase the awareness of the younger generation about the importance of cultural heritage, thus encouraging interest in learning and preserving it. It is necessary for the involvement of local communities in training programs and workshops to empower the community's ability to care for and understand lontar. This not only preserves traditional knowledge but also creates a sense of ownership of cultural heritage. The results of the study show the need for support from the government and effective policies to encourage community involvement in cultural preservation. This policy can create more inclusive and sustainable initiatives. Digitalization and the use of technologies such as augmented reality can increase accessibility and attract the interest of the younger generation. This shows that technology can serve as an effective tool in cultural preservation, while maintaining the relevance of traditions in the modern era. The preservation of palm trees can be a driver for cultural tourism, which has the potential to increase local income. This creates new economic opportunities and supports sustainable economic development in local communities. This research shows the importance of collaboration between a wide range of stakeholders, including academics, artists, and local communities. This synergy can produce innovative solutions that are relevant in cultural preservation. The implication of this study extends beyond cultural preservation toward policy design and innovation management. Strengthening collaboration among universities, local communities, cultural institutions, government agencies, and creative industries will ensure that Bali’s digital cultural heritage thrives as a sustainable innovation ecosystem. This integrative approach transforms heritage conservation into an innovation-driven, community-empowering, and economically viable system.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, validation, and funding acquisition A.A.G.A, Geria; investigation, resources, data curation, writing, I.N, Rema; review and editing, visualization, project administration, M. Setini. All authors co-operated in completing this paper and All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all those who have contributed to this research. First, to key informants, including cultural researchers, cultural activists, and artists who have shared their knowledge and experiences. We are also grateful to PGRI Mahadewa University and Warmadewa University for the academic support and facilities provided. Thank you to the National Research and Innovation Agency for providing direction and support in the development of this research. We appreciate the input of colleagues and research colleagues who have assisted in the analysis and writing process. Finally, we would like to thank the family and friends who have provided moral support during this study. Without their help and support, this research would not have been possible.

Ethics approval and interview consent

in the study ethical approval was obtained from the Cultural Ethics Committee of PGRI Mahadewa University (Ethics 007/PGRI Mahadewa University). All research was conducted in accordance with the rules and guidelines outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. Consent to interview was obtained consciously.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- E. C. Gkika et al., ‘The impact of algorithm awareness on the acceptance of personalized social media content recommendation based on the technology acceptance model’, J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex., vol. 11, no. 2, pp. 3323–3342, 2025. [CrossRef]

- B. Mohanapriya and M. Suriya, Indian knowledge systems: Principles and practices. SSS PUBLICATIONS, 2025.

- M. Reynolds, Reading Practice: The Pursuit of Natural Knowledge from Manuscript to Print. University of Chicago Press, 2024.

- I. M. Sudarsana, ‘Conservation of Hindu Religious Lontar Manuscripts Through Lontar Digitization Website Information System in Tabanan Regency’, J. Penelit. Agama Hindu, vol. 8, no. 4, pp. 535–547, 2024. [CrossRef]

- N. Badenoch, ‘“We are all Pana here, but there are no real Pana left”: language in cultural adaptation in the Laos-China border area’, Asian Ethn., pp. 1–26, 2025. [CrossRef]

- I. Kurnia B and I. B. K. Sudarma, ‘Cultural Entropy on Digitizing Balinese Lontar Manuscripts: Overcoming Challenges and Seizing Opportunities’, IFLA World Libr. Inf. Congr., pp. 1–15, 2017, [Online]. Available: https://2017.ifla.org/congress-information.html.

- A. Hornbacher, ‘The Body of Letters: Balinese Aksara as an Intersection between Script, Power and Knowledge’, Richard Fox u. Annette Hornbacher (Hgg.), Mater. Effic. Balinese Lett. Situating Scriptural Pract., pp. 90–99, 2016.

- S. Bhuvaneswari and K. Kathiravan, ‘Enhancing epigraphy: a deep learning approach to recognize and analyze Tamil ancient inscriptions’, Neural Comput. Appl., vol. 36, no. 31, pp. 19839–19861, 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. Zhang, X. Song, and Y. Wang, ‘Two different storage environments for palm leaf manuscripts: comparison of deterioration phenomena’, Restaur. Int. J. Preserv. Libr. Arch. Mater., vol. 42, no. 3, pp. 147–168, 2021. [CrossRef]

- I. W. A. S. Darma and N. P. Sutramiani, ‘Segmentation of balinese script on lontar manuscripts using projection profile’, in Proceedings of 2019 5th International Conference on New Media Studies, CONMEDIA 2019, Informatics Engineering, STMIK STIKOM Indonesia, Denpasar, Indonesia: Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., 2019, pp. 212–216. [CrossRef]

- A. P. Narendra, ‘Preservation and Conservation of Lontar Gedong Kirtya Liefrinck-Van Der Tuuk Singaraja Bali’, Rec. Libr. J., vol. 7, no. 1, pp. 28–39, 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. Sudarma, S. Ariyani, and M. Artana, ‘Balinese script’s character reconstructionusing linear discriminant analysis’, Indones. J. Electr. Eng. Comput. Sci., vol. 4, no. 2, pp. 479–485, 2016. [CrossRef]

- I. Kurnia B and I. B. K. Sudarma, ‘Cultural entropy on digitizing balinese lontar manuscripts: overcoming challenges and seizing opportunities’, 2017.

- I. B. P. Eka Suadnyana and I. P. Ariyasa Darmawan, ‘Nilai Pendidikan Agama Hindu Dalam Lontar Siwa Sasana’, Cetta J. Ilmu Pendidik., vol. 3, no. 2, pp. 371–391, 2020. [CrossRef]

- I. Wayan Sukabawa, ‘Asas-Asas Kepemimpinan Hindu Dalam Lontar Niti Raja Sasana’, J. Penelit. Agama Hindu, vol. 3, no. 1, pp. 135–143, 2019, [Online]. Available: http://jayapanguspress.penerbit.org/index.php/JPAH.

- I. N. S. Ardiyasa, ‘Eksistensi Naskah Lontar Masyarakat Bali (Studi Kasus Hasil Pemetaan Penuyuluh Bahasa Bali Tahun 2016-2018)’, Kalangwan J. Pendidik. Agama, Bhs. dan Sastra, vol. 11, no. 1, pp. 74–82, 2021. [CrossRef]

- C. Li et al., ‘Effects of Different Management Measures on the Net Carbon Sequestration Capacity of Moso bamboo Forest Ecosystem’, Linye Kexue/Scientia Silvae Sin., vol. 53, no. 2, pp. 1–9, 2017. [CrossRef]

- S. Ayer et al., ‘Effect of elevation and aspect on carbon stock of bamboo stands (Bambusa nutans subsp. Cupulata) outside the forest area in Eastern Nepal’, Trees, For. People, vol. 18, 2024. [CrossRef]

- D. Siahaan, N. P. Sutramiani, N. Suciati, I. N. Duija, and I. W. A. S. Darma, ‘DeepLontar dataset for handwritten Balinese character detection and syllable recognition on Lontar manuscript’, Sci. Data, vol. 9, no. 1, 2022. [CrossRef]

- D. K. Gupta and V. Sharma, ‘Enriching and enhancing digital cultural heritage through crowd contribution’, J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev., vol. 7, no. 1, pp. 14–32, 2017. [CrossRef]

- I. K. D. Noorwatha, I. Santosa, G. P. Adhitama, and A. A. G. R. Remawa, ‘East meet West: the Balinese undagi-Dutch architect cross-cultural design collaborations in Bali early colonial era (1910-1918)’, Cogent Arts Humanit., vol. 11, no. 1, p. 2390792, 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. M. Hood, ‘Sustainability strategies among Balinese heritage ensembles’, Malaysian J. Music, vol. 3, no. 2, pp. 1–13, 2014.

- P. Pacheco, G. Schoneveld, A. Dermawan, H. Komarudin, and M. Djama, ‘Governing sustainable palm oil supply: Disconnects, complementarities, and antagonisms between state regulations and private standards’, Regul. Gov., vol. 14, no. 3, pp. 568–598, 2020. [CrossRef]

- A. A. Dokukina and I. A. Petrovskaya, ‘Open innovation as a business performance accelerator: Challenges and opportunities for the firms’ competitive strategy’, in Smart Innovation, Systems and Technologies, S. D.B., S. V.V., B. A.T., P. V.I., and S. D.B., Eds., Plekhanov Russian University of Economics, 36 Stremyanny, Moscow, 117997, Russian Federation: Springer, 2020, pp. 275–286. [CrossRef]

- P. Ceravolo, E. Damiani, F. Frati, J. Maggesi, R. Mainardi, and F. Zavatarelli, ‘Innovation factory: An innovative collaboration and management scenario’, in Lecture Notes of the Institute for Computer Sciences, Social-Informatics and Telecommunications Engineering, LNICST, G. R., B. F., Z. M., and A. M., Eds., Computer Science Department, Università degli Studi di Milano, via Bramante 65, Crema, 26013, Italy: Springer Verlag, 2016, pp. 99–105. [CrossRef]

- T. Ingram and T. Kraśnicka, ‘The interplay of dynamic capabilities and innovation output in family and non-family companies: The moderating effect of environmental dynamism’, Entrep. Bus. Econ. Rev., vol. 11, no. 2, pp. 63–86, 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. Bogers, ‘Knowledge sharing in open innovation: An overview of theoretical perspectives on collaborative innovation’, in Open Innovation in Firms and Public Administrations: Technologies for Value Creation, University of Southern Denmark, Denmark: IGI Global, 2011, pp. 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Q. Liu, X. Zhao, and B. Sun, ‘Value co-creation mechanisms of enterprises and users under crowdsource-based open innovation’, Int. J. Crowd Sci., vol. 2, no. 1, pp. 2–17, 2018. [CrossRef]

- M. Wang, R. Zhang, R. Abdulwase, S. Yan, and M. Muhammad, ‘The Construction of Ecosystem and Collaboration Platform for Enterprise Open Innovation’, Front. Psychol., vol. 13, 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. Mladenow, C. Bauer, and C. Strauss, ‘Social crowd integration in new product development: Crowdsourcing communities nourish the open innovation paradigm’, Glob. J. Flex. Syst. Manag., vol. 15, no. 1, pp. 77–86, 2014. [CrossRef]

- A. D. Do, T. B. C. Pham, T. D. Le, and D. U. Trinh, ‘Open Innovation in Hanoi-Based Enterprises’, in Knowledge Transformation and Innovation in Global Society: Perspective in a Changing Asia, National Economics University, Hanoi, Viet Nam: Springer Nature, 2024, pp. 263–273. [CrossRef]

- M. Portuguez-Castro, ‘Exploring the Potential of Open Innovation for Co-Creation in Entrepreneurship: A Systematic Literature Review’, Adm. Sci., vol. 13, no. 9, 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. Bogers, ‘Knowledge sharing in open innovation: An overview of theoretical perspectives on collaborative innovation’, Open Innov. firms public Adm. Technol. value Creat., pp. 1–14, 2012.

- A. Aagaard, Digital business models: Driving transformation and innovation. 2018. [CrossRef]

- M. Setini, A. Agung, G. Alit, and U. Mahadewa, ‘Journal of Open Innovation : Technology , Market , and Complexity Creativity and Heritage : Integrating the Dynamics of Lontar Bali with Open Innovation’.

- H. Chesbrough, ‘To recover faster from Covid-19, open up: Managerial implications from an open innovation perspective’, Ind. Mark. Manag., vol. 88, pp. 410–413, 2020.

- M. Setini, N. N. K. Yasa, I. W. G. Supartha, I. G. A. K. Giantari, and I. Rajiani, ‘The passway of women entrepreneurship: Starting from social capital with open innovation, through to knowledge sharing and innovative performance’, J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex., vol. 6, no. 2, p. 25, 2020.

- A. Mesoudi, ‘How Cultural Evolutionary Theory Can Inform Social Psychology and Vice Versa’, Psychol. Rev., vol. 116, no. 4, pp. 929–952, 2009. [CrossRef]

- A. Mesoudi, ‘Cultural evolution: Integrating psychology, evolution and culture’, Curr. Opin. Psychol., vol. 7, pp. 17–22, 2016. [CrossRef]

- P. E. Smaldino, ‘The cultural evolution of emergent group-level traits’, Behav. Brain Sci., vol. 37, no. 3, pp. 243–254, 2014. [CrossRef]

- J. Henrich and N. Henrich, ‘The evolution of cultural adaptations: Fijian food taboos protect against dangerous marine toxins’, in Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, Department of Psychology, University of British Columbia, 2136 West Mall, Vancouver, V6T 1Z4, Canada: Royal Society, 2010, pp. 3715–3724. [CrossRef]

- C. Cordes, ‘The promises of a naturalistic approach: how cultural evolution theory can inform (evolutionary) economics’, J. Evol. Econ., vol. 29, no. 4, pp. 1241–1262, 2019. [CrossRef]

- P. S. Shukla and S. D. Shamurailatpam, ‘Effects and Implications of Event Tourism on Sustainable Community Development: A Review’, in Event Tourism and Sustainable Community Development: Advances, Effects, and Implications, Department of Commerce & Business Management, Faculty of Commerce, The M.S University of Baroda, Gujarat, Vadodara, India: Apple Academic Press, 2023, pp. 31–49. [Online]. Available: https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85174138918&partnerID=40&md5=bd41d0753db02175afa6a52abfe444d4.

- N. Swaminathan, A. Maruthamuthu, and J. H. R. Kumar, ‘Community participation in development: Short comings and beneficial solutions’, Indian J. Soc. Work, vol. 64, no. 4, pp. 559–566, 2003, [Online]. Available: https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-3242770506&partnerID=40&md5=909504fd029fb8c55fe4891248e2a821.

- E. B. Duarte and M. F. A. S. Machado, ‘The exercise of community participation in the sphere of Canindé’s Municipal Council of Health’, Saude e Soc., vol. 21, no. SUPPL. 1, pp. 126–137, 2012. [CrossRef]

- M. Dooris and Z. Heritage, ‘Healthy cities: Facilitating the active participation and empowerment of local people’, J. Urban Heal., vol. 90, no. SUPPL 1, pp. 74–91, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Z. Heritage and M. Dooris, ‘Community participation and empowerment in Healthy Cities.’, Health Promot. Int., vol. 24 Suppl 1, pp. i45–i55, 2009. [CrossRef]

- A. Risfandini, I. Yulianto, and W.-H. Wan-Zainal-Shukri, ‘Local Community Empowerment for Sustainable Tourism Development: A Case Study of Edelweiss Park Wonokitri Village’, Int. J. Sustain. Dev. Plan., vol. 18, no. 11, pp. 3617–3623, 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. Cerisola, Cultural Heritage, Creativity and Economic Development. Politecnico di Milano, Built Environment and Construction Engineering (ABC) Department, Italy: Edward Elgar Publishing Ltd., 2019. [CrossRef]

- N. T. Nam and N. N. Thanh, ‘The role of local communities in the conservation of cultural heritage sites: A case study of Vietnam’, J. Asian Sci. Res., vol. 14, no. 2, pp. 179–196, 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. A. W. Mohd Asri and N. Z. Harun, ‘Local Community Involvement in Protecting Malaysia’s Historic Buildings: An Exploratory Study’, in Lecture Notes in Civil Engineering, S. D.F., R. D.H., R. Y., H. I., A.-F. J., and W. A., Eds., Institute of Malay World and Civilization, National University of Malaysia, Bangi, Malaysia: Springer Science and Business Media Deutschland GmbH, 2023, pp. 301–329. [CrossRef]

- W. N. W. J. Ariffin, S. Shahfiq, A. Ibrahim, H. M. Pauzi, and A. A. M. Rami, ‘PRESERVATION OF CRAFT HERITAGE AND ITS POTENTIAL IN YOUTH ECONOMIC EMPOWERMENT’, Plan. Malaysia, vol. 21, no. 6, pp. 157–169, 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. Sinulingga, J. L. Marpaung, H. S. Sibarani, A. Amalia, and F. Kumalasari, ‘Sustainable Tourism Development in Lake Toba: A Comprehensive Analysis of Economic, Environmental, and Cultural Impacts’, Int. J. Sustain. Dev. Plan., vol. 19, no. 8, pp. 2907–2917, 2024. [CrossRef]

- R. Camagni, R. Capello, S. Cerisola, and E. Panzera, ‘The cultural heritage – territorial capital nexus: Theory and empirics’, Capitale Cult., vol. 2020, pp. 33–59, 2020. [CrossRef]

- G. E. J. Mogomotsi, P. K. Mogomotsi, R. Gondo, and T. J. Madigele, ‘Community participation in cultural heritage and environmental policy formulation in Botswana’, Chinese J. Popul. Resour. Environ., vol. 16, no. 2, pp. 171–180, 2018. [CrossRef]

- N. A. Ugong, B. Bala, B. B. B. Bee, and K. Jusoff, ‘The community involvement in sustaining an archaeological site: The case of Sarawak, Malaysia’, Int. J. Conserv. Sci., vol. 10, no. 3, pp. 441–448, 2019, [Online]. Available: https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85084250817&partnerID=40&md5=50464f4cae34f5c9ebdae81bf1202eb8.

- C. Ma, T. Somrak, S. Manajit, and C. Gao, ‘Exploring the Potential Synergy Between Disruptive Technology and Historical/Cultural Heritage in Thailand’s Tourism Industry for Achieving Sustainable Development in the Future’, Int. J. Tour. Res., vol. 26, no. 5, 2024. [CrossRef]

- G. Chitty, Heritage, conservation and communities: Engagement, participation and capacity building. Centre for Conservation Studies, Department of Archaeology, University of York, United Kingdom: Taylor and Francis, 2016. [CrossRef]

- A. H. Aida, ‘Cultural Heritage Preservation in the Digital Age: Balancing Tradition and Innovation in Mediterranean Smart Cities’, in Proceedings of 2024 1st Edition of the Mediterranean Smart Cities Conference, MSCC 2024, D. A.B., D. A.B., E. H. A., and E. M., Eds., Department of PhD Architecture, University Ion Mincu of architecture and urbanism, Bucharest, Romania: Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., 2024. [CrossRef]

- A. Aldweesh, ‘Decentralized Framework for Cultural Heritage Conservation using Blockchain’, in 2023 3rd International Conference on Computing and Information Technology, ICCIT 2023, Shaqra University, College of Computer Science and It, Shaqra, Saudi Arabia: Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., 2023, pp. 591–596. [CrossRef]

- A. Nasrolahi, C. Gena, V. Messina, and S. Ejraei, ‘Participatory Monitoring in Cultural Heritage Conservation: Case Study: The Landscape zone of the Bisotun World Heritage Site’, in UMAP 2021 - Adjunct Publication of the 29th ACM Conference on User Modeling, Adaptation and Personalization, University of Torino, Tech4Culture PhD Program, Italy: Association for Computing Machinery, Inc, 2021, pp. 186–188. [CrossRef]

- I. W. Sugita, M. Setini, and Y. Anshori, ‘Counter hegemony of cultural art innovation against art in digital media’, J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex., vol. 7, no. 2, p. 147, 2021.

- V. Braun and V. Clarke, ‘Novel insights into patients’ life-worlds: the value of qualitative research’, The Lancet Psychiatry, vol. 6, no. 9, pp. 720–721, 2019.

- T. A. Lambebo and M. B. Abegaz, ‘Does how to train matter ? Unveiling an effective training approach to nurture successful entrepreneurs : a systematic review’, 2025.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).