Submitted:

14 October 2025

Posted:

15 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

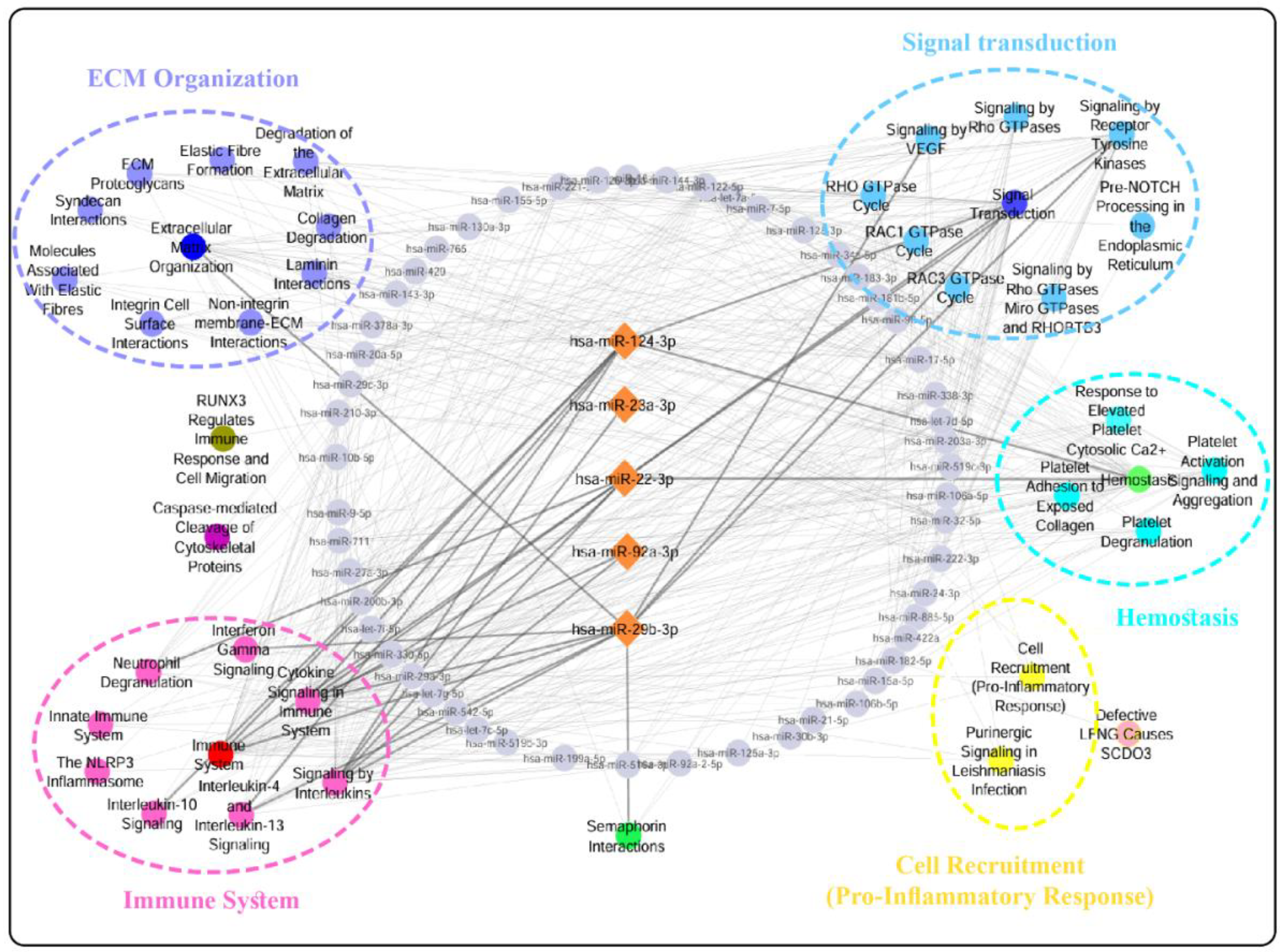

Background: Gastric cancer (GC) remains a leading cause of global cancer mortality, with late-stage diagnosis contributing significantly to poor patient outcomes. Circulating microRNAs (miRNAs) offer promise due to their stability in biofluids and established roles in carcinogenesis. However, existing miRNA biomarker candidates for GC suffer from inconsistent validation across studies, limited specificity, and insufficient mechanistic links to gastric tumor biology. We addressed this by integrating tissue and blood transcriptomics to identify GC-specific miRNAs, which were then validated using machine learning. Methods: Dysregulated genes (DEGs) and miRNAs (DEMs) were identified from tissue mRNA (GSE54129, GSE113255) and blood miRNA/mRNA datasets (GSE106817, GSE174302). Pathway enrichment (Reactome) revealed GC-specific pathways shared between tissue DEGs and blood DEM targets. Targets of 59 DEMs were enriched in these pathways in the blood miRNA dataset. From these, a 5-miRNA panel was selected using 10 machine learning feature selection methods (e.g., Gini Index, Information Gain) and validated using Random Forest and Naïve Bayes classifiers on discovery (GSE106817) and external (GSE164174) datasets. Results: Integration identified 59 GC-specific extracellular miRNAs linked to 39 enriched pathways (e.g., signaling, metabolism). The 5-miRNA panel (hsa-miR-124-3p, hsa-miR-23a-3p, hsa-miR-22-3p, hsa-miR-29b-3p, hsa-miR-92a-3p) achieved near-perfect discovery performance (RF: AUC=98.50%, ACC=98.36%) and high external validation (AUC=95.30%, ACC=89.24%). Conclusion: Our pipeline bridges tissue pathology and circulating miRNA profiles, yielding a highly specific 5-miRNA Blood Signature with clinical diagnostic potential for GC.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Dataset Selection

2.2. Step 1: GC-Specific DEMs Discovery

2.2.1. Differential Expression Analysis

2.2.2. Finding GC-Specific DEMs

GC Tissue Pathway Enrichment Analysis

Circulating miRNA Pathway Enrichment Analysis

2.3. Step 2: Biomarker Panel Selection and Validation

2.3.1. Feature Selection

2.3.2. Evaluate Performance and External Validation

3. Results

3.1. Step 1: Specific DEMs Discovery

3.2. Step 2: Biomarker Panel Selection and Validation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Electronic supplementary material

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| GC | Gastric Cancer |

| DEM | Differentially Expressed miRNA |

| DEG | Differentially Expressed Gene |

| GEO | Gene Expression Omnibus |

| RF | Random Forest |

| NB | Naïve Bayes |

| AUC | Area Under the Curve |

| ACC | Accuracy |

| SEN | Sensitivity |

| SPE | Specificity |

| MCC | Matthews Correlation Coefficient |

| ROC | Receiver Operating Characteristic |

| PCA | Principal Component Analysis |

| ECM | Extracellular Matrix |

| TCGA | The Cancer Genome Atlas |

| MAZ | Myc-Associated Zinc Finger Protein |

| MMP2 | Matrix Metallopeptidase 2 |

| PI3K/Akt | Phosphoinositide 3-Kinase/Ak strain transforming |

| RAS/RAF/MAPK | Rat Sarcoma Viral Oncogene Homolog/Rapidly Accelerated Fibrosarcoma/Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase |

| PRDX4 | Peroxiredoxin 4 |

| LPCAT1 | Lysophosphatidylcholine Acyltransferase 1 |

| RGS3 | Regulator of G-protein Signaling 3 |

References

- Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021; 71: 209–49. [CrossRef]

- Ajani JA, D’Amico TA, Bentrem DJ, Chao J, Cooke D, Corvera C, et al. Gastric Cancer, Version 2.2022, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2022; 20:167-192.

- Song Z, Wu Y, Yang J, Yang D, Fang X. Progress in the treatment of advanced gastric cancer. Tumor Biol. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Immune checkpoint inhibitor efficacy in advanced head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Mol Clin Oncol. 2020; 13:87.

- Sharifi Z, Talkhabi M, Taleahmad S. Identification of potential microRNA diagnostic panels and uncovering regulatory mechanisms in breast cancer pathogenesis. Sci Rep. 2022; 12:20135. [CrossRef]

- Roointan A, Gholaminejad A, Shojaie B, Hudkins KL, Gheisari Y. Candidate microRNA biomarkers in lupus nephritis: A meta-analysis of profiling studies in kidney, blood, and urine samples. Mol Diagn Ther. 2023; 27:141–58. [CrossRef]

- Gholaminejad A, Zare N, Dana N, Shafie D, Mani A, Javanmard SH. A meta-analysis of microRNA expression profiling studies in heart failure. Heart Fail Rev. 2021; 26:997-1021. [CrossRef]

- Gholaminejad A, Abdul Tehrani H, Gholami Fesharaki M. Identification of candidate microRNA biomarkers in renal fibrosis: a meta-analysis of profiling studies. Biomarkers. 2018;23(8):713–24.

- Ignatiadis M, Sledge GW, Jeffrey SS. Liquid biopsy enters the clinic — implementation issues and future challenges. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2021; 18:297–312. [CrossRef]

- Azari H, et al. Machine learning algorithms reveal potential miRNAs biomarkers in gastric cancer. Sci Rep. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Masoudi-Sobhanzadeh Y, Gholaminejad A, Gheisari Y, Roointan A. Discovering driver nodes in chronic kidney disease-related networks using Trader as a newly developed algorithm. Comput Biol Med. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Momeni M, Rashidifar M, Balam FH, Roointan A, Gholaminejad A. A comprehensive analysis of gene expression profiling data in COVID-19 patients for discovery of specific and differential blood biomarker signatures. Sci Rep. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Zhu SL, Dong J, Zhang C, Huang YB, Pan W. Pan, Application of machine learning in the diagnosis of gastric cancer based on noninvasive characteristics, PLoS One, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Gilani N, Arabi Belaghi R, Aftabi Y, Faramarzi E, Edgünlü T, Somi MH. Identifying potential miRNA biomarkers for gastric cancer diagnosis using machine learning variable selection approach, Front. Genet. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Augustine J, Jereesh AS. Blood-based gene-expression biomarkers identification for the non-invasive diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease using two-layer hybrid feature selection, Gene. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Ponnampalam SN, Rizan Kamaluddin N, Zakaria Z, Matheneswaran V, Ganesan D, Saffari. Hardy. A blood-based gene expression and signaling pathway analysis to differentiate between high and low grade gliomas. Oncol. Rep. 2017; 37:10 22. [CrossRef]

- Hu G, Lv Q, Yan J, Chen L, Du J, Zhao K, Xu W. MicroRNA-17 as a promising diagnostic biomarker of gastric cancer. FEBS Open Bio. 2018;8(9):1508-1523.

- Tong D, Zhang J, Wang X, Li Q, Liu L, Lu A, Guo B, Yang J, Ni L, Qin H, Zhao L, Huang C. MiR-22 suppresses gastric cancer cell proliferation, Oncogenesis. 2020;9(1):99.

- Yen HH, Chen PY, Huang RYJ, Jeng JM, Lai IR. Lai, Clinicopathological features and cancer transcriptomic profiling of gastric carcinoma. J. Pathol Clin Res. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Qu Z, Han Y, Zhu Q, Ding W, Wang Y, Zhang Y, et al. A novel neutrophil extracellular traps signature in gastric cancer. J Inflamm Res. 2023; 16:3419-3436.

- Yan J, Ye G, Jin Y, Miao M, Li Q, Zhou H. Identification of circRNA biomarkers in gastric cancer. BMC Genomics. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Qu JL, Qu XJ, Zhao MF, Teng YE, Zhang Y, Hou KZ, Jiang YH, Yang XH, Liu YP. Gastric cancer exosomes promote tumour cell proliferation. Dig Liver Dis. 2009;41:875-880. [CrossRef]

- Tabibzadeh A, Tameshkel FS, Moradi Y, Soltani S, Moradi-Lakeh M, Ashrafi GH, et al. Signal transduction pathway mutations in GI cancers. Sc Rep. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Shen B, Li M, Wang H, Xin L, Xie J. Expression and clinical significance of the RAS/RAF/MAPK cell signaling pathway in gastric cancer, Int. J. Clin. Exp. Med., 2018;11:11682 11689.

- Zhang L, Wu K, Hou Y, Li X. PRDX4 and TXNDC5 in gastric cancer, Transl. Cancer Res.13 2024;13:81 101. [CrossRef]

- Santos EC, Binato R, Fernandes PV, Ferreira MA, Abdelhay E. PPI network in gastric cancer, Cancer Biomark. 2022; 33:83 96.

- Chen ZX, Liang L, Huang HQ, Li JD, He RQ, Huang ZG, Song R, et al. LPCAT1 enhances invasion in gastric cancer. Cancer Med. 2023; 12:13438-13454.

- Repetto O, De Re V. Coagulation and fibrinolysis in gastric cancer. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2017; 1404:27–48.

- Chang WJ, Du Y, Zhao X, Ma LY, Cao GW. Inflammation-related factors predicting prognosis of gastric cancer, World J Gastroenterol. 2014; 20:4586-4596. [CrossRef]

- Wu Q, Zhong H, Jiao L, Wen Y, Zhou Y, Zhou J, Lu X, Song X, Ying B. MiR-124-3p inhibits gastric cancer migration, Pathol Res Pract. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Liu F, Hu H, Zhao J, Zhang Z, Ai X, Tang L, Xie L. miR-124-3p suppresses tumor growth in gastric cancer. Biomed Rep. 2018; 8:29 34.

- Jiang Z, Chen H, Su M, Wu L, Yu X, Liu Z. MicroRNA-23a-3p in gastric cancer via CCL22/PI3K/Akt axis. Bioengineered. 2021; 12:5454–5465.

- 33 Zhao X, Ye N, Feng X, Ju H, Liu R, Lu W. MicroRNA-29b-3p inhibits migration of gastric cancer cells. Onco Targets Ther. 2021; 14:4081–4091.

- Wang T, Hou J, Jian S, Luo Q, Wei J, Li Z, Wang X, et al. miR-29b negatively regulates MMP2. J Cancer. 2018; 9:2595-2601. [CrossRef]

- Huang Y, Zhu J, Li W, Zhang Z, Xiong P, Wang H, Zhang J. Serum microRNA panel for gastric cancer. Oncol Rep. 2018; 40: 3865-3876.

- Tang Y, Liu X, Su B, Zhang Z, Zeng X, Lei Y, et al. microRNA-22 targets metatherian in gastric cancer. Mol Med Rep. 2015; 12:4354-4360.

- Zuo QF, et al. MicroRNA-22 inhibits tumor growth in gastric cancer. Cell Death Dis. 2015. [CrossRef]

- Li B. et al. miRNA-22 suppresses colon cancer cell migration. Oncol Rep. 2013; 29:103-110.

- Zhang S, Zhang D, Yi C, Wang Y, Wang H, Wang J. MicroRNA-22 functions as a tumor suppressor by targeting SIRT1 in renal cell carcinoma. Oncol Rep. 2016;35: 559–567. [CrossRef]

- Lu X, Lu J, Wang S, Zhang Y, Ding Y, Shen X, et al. Circulating serum exosomal miR-92a-3p as a novel biomarker for early diagnosis of gastric cancer. Future Oncol. 2021; 17:907-919. [CrossRef]

- Jiang M, Li X, Quan X, Li X, Zhou B. MiR-92a family as diagnostic biomarker and Potential Therapeutic Target in Human Cancers. Front Mol Biosci. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Dai B, Chen RC, Zhu SZ, Zhang WW. Using random forest algorithm for breast cancer diagnosis, in: Proc. 2018 Int. Symp. Comput Consum. Control (IS3C). IEEE; 2018.1–4.

- Liu Y, Bian B, Chen S, Zhou B, Zhang P, Shen L, et al. Identification and validation of four serum biomarkers with optimal diagnostic and prognostic potential for gastric cancer based on machine learning algorithms. Cancer Med. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Liu SS, Wan QS, Lv C, Wang JK, Jiang S, Cai D, et al. Integrating trans-omics, cellular experiments and clinical validation to identify ILF2 as a diagnostic serum biomarker and therapeutic target in gastric cancer. BMC Cancer. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Kamel H, Abdulah D, Al-Tuwaijari JM. Cancer classification using gaussian naive bayes algorithm, in: Proc. 2019 Int. Eng. Conf. (IEC). IEEE; 2019. 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Naorem LD, Muthaiyan M, Venkatesan A. Identification of dysregulated miRNAs in triple negative breast cancer: a meta-analysis approach. J Cell Physiol. 2019;234:11768–11779. [CrossRef]

- Ali M, Mansoor Ali H. Performance Analysis of Classification Learning Methods on Large Dataset using two Data Mining Tools. J. Indep Stud Res Comput. 2015. [CrossRef]

- Thirunavukkarasu K, Wadhawa M. Analysis and Comparison Study of Data Mining Algorithms Using Rapid Miner. Int J Comput Sci Eng Appl. 2016;6(1):9-21. [CrossRef]

- Arunadevi J, Ramya S, Ramesh Raja M. A study of classification algorithms using Rapidminer. Int J Pure Appl Math. 2018;119:15977-15988.

| Dataset ID | Sample type |

Technology/platform/platform ID | Sample size (T/N) | Usage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GSE54129 |

GC tissue | Microarray/Affymetrix/GPL570 | 111/21 | Pathway enrichment in step 1 |

| GSE113255 |

GC tissue | RNAseq/Illumina/GPL18573 | 130/10 | Pathway enrichment in step 1 |

| GSE174302 |

GC plasma | RNAseq/HiSeq X Ten (Homo sapiens)/GPL20795 | 27/15 | Validation of miRNA targets (pathway enrichment of GSE106817 dataset) in step 1 |

| GSE106817 |

GC serum miRNA | Microarray/3D-Gene Human miRNA V21_1.0.0/GPL21263 | 115/2759 |

Pathway enrichment in step 1, Feature selection for finding the biomarker panel, and validation of that in step 2 |

| GSE164174 | GC serum miRNA | 3D-Gene Human miRNA V21_1.0.0/GPL21263 | 1417/1417 | External validation of biomarker panels in step 2 |

| MiRNA panels | Dataset ID | SEN | SPE | ACC | MCC | AUC |

| 5-miRNA Panel | GSE106817 | 77.39 | 99.24 | 98.36 | 78.28 | 98.50 |

| GSE164174 | 93.79 | 84.69 | 89.24 | 78.80 | 95.30 | |

| GSE106817 | 76.52 | 98.99 | 98.09 | 75.19 | 98.40 | |

| 3-miRNA Panel | GSE164174 | 91.88 | 83.06 | 87.47 | 75.24 | 94.40 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).