Submitted:

10 October 2025

Posted:

11 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

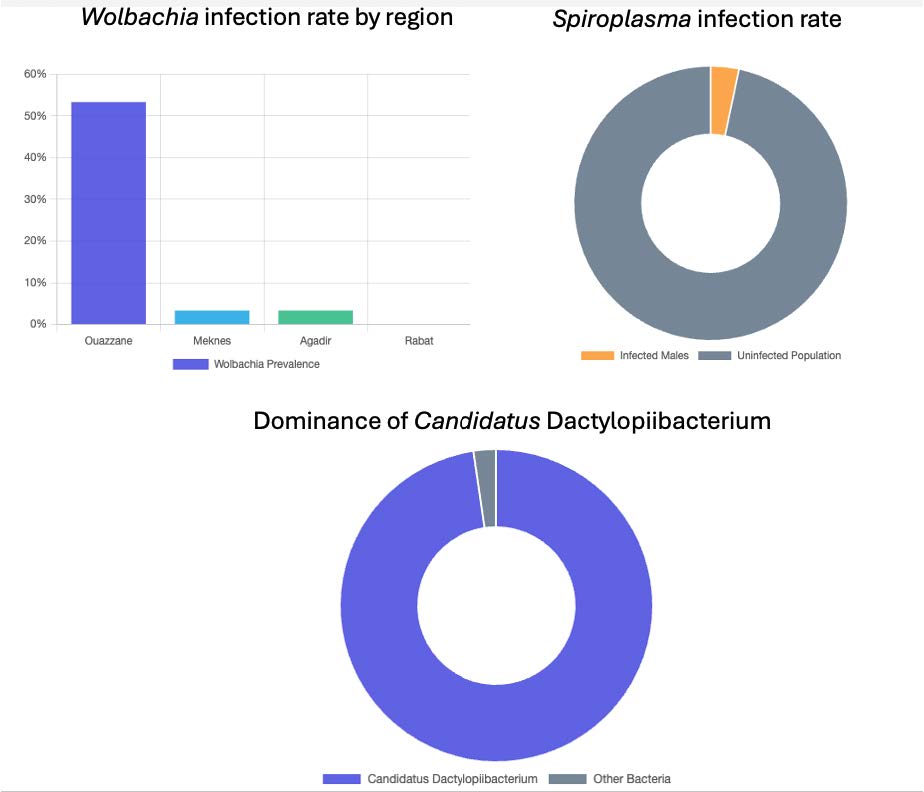

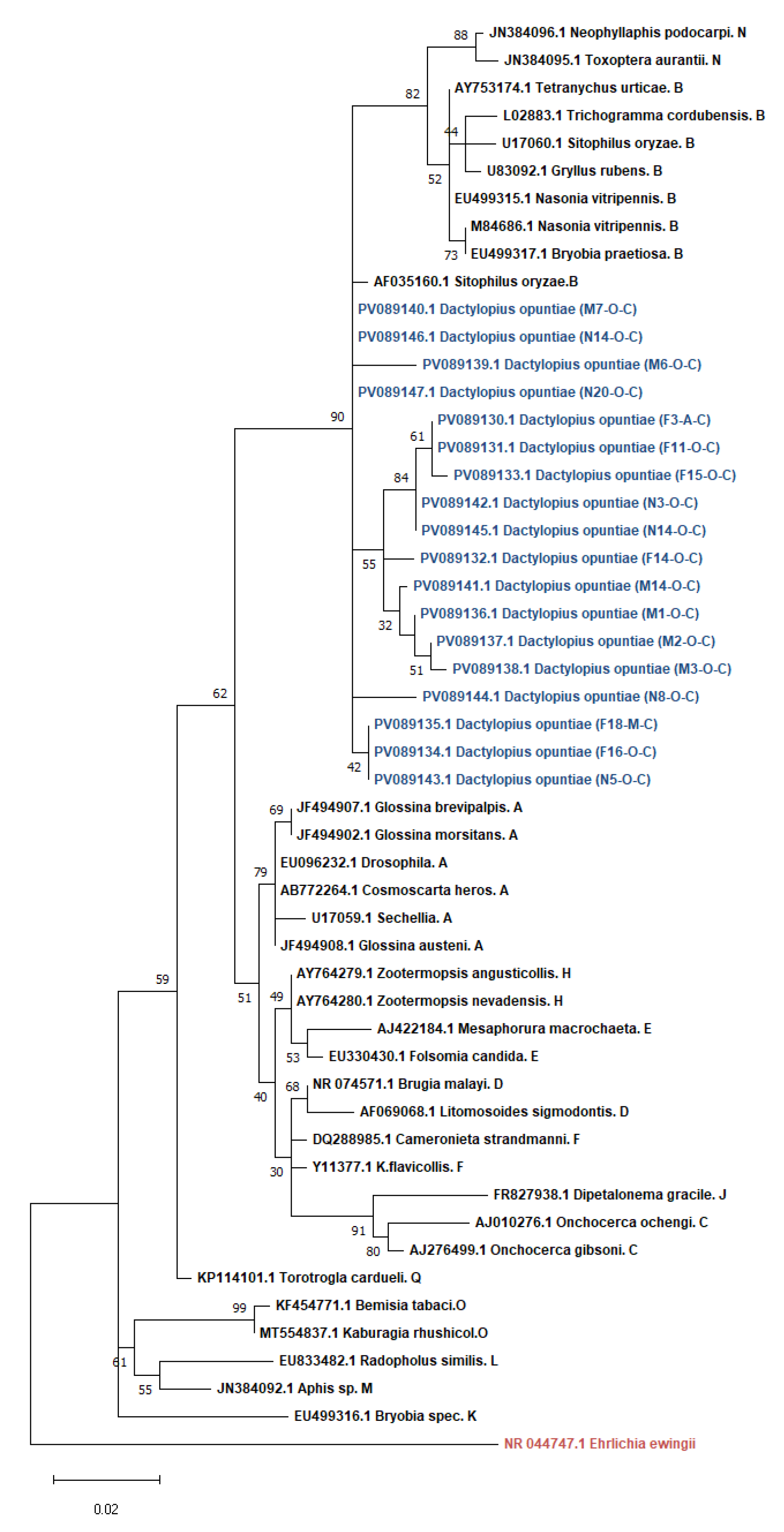

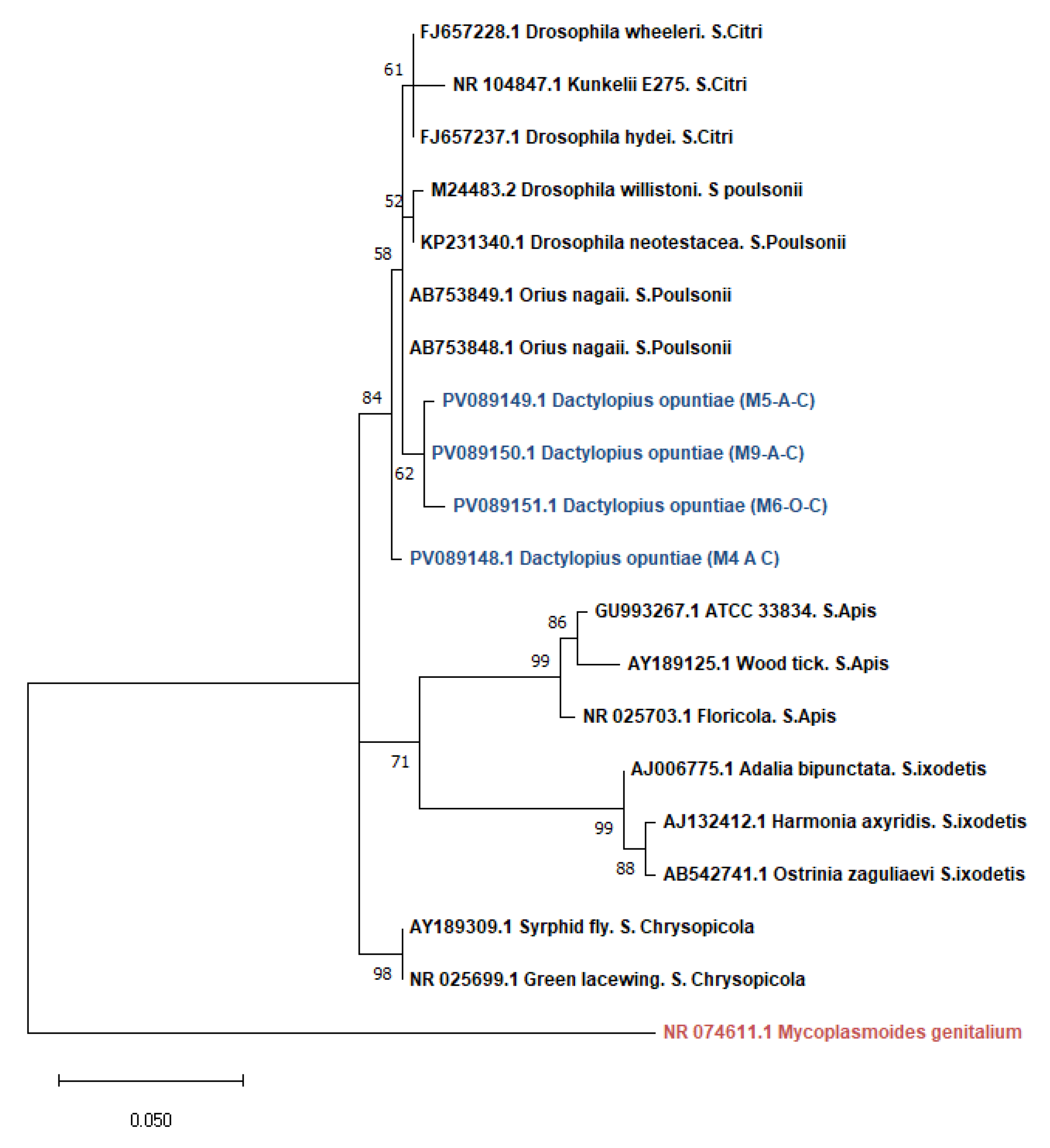

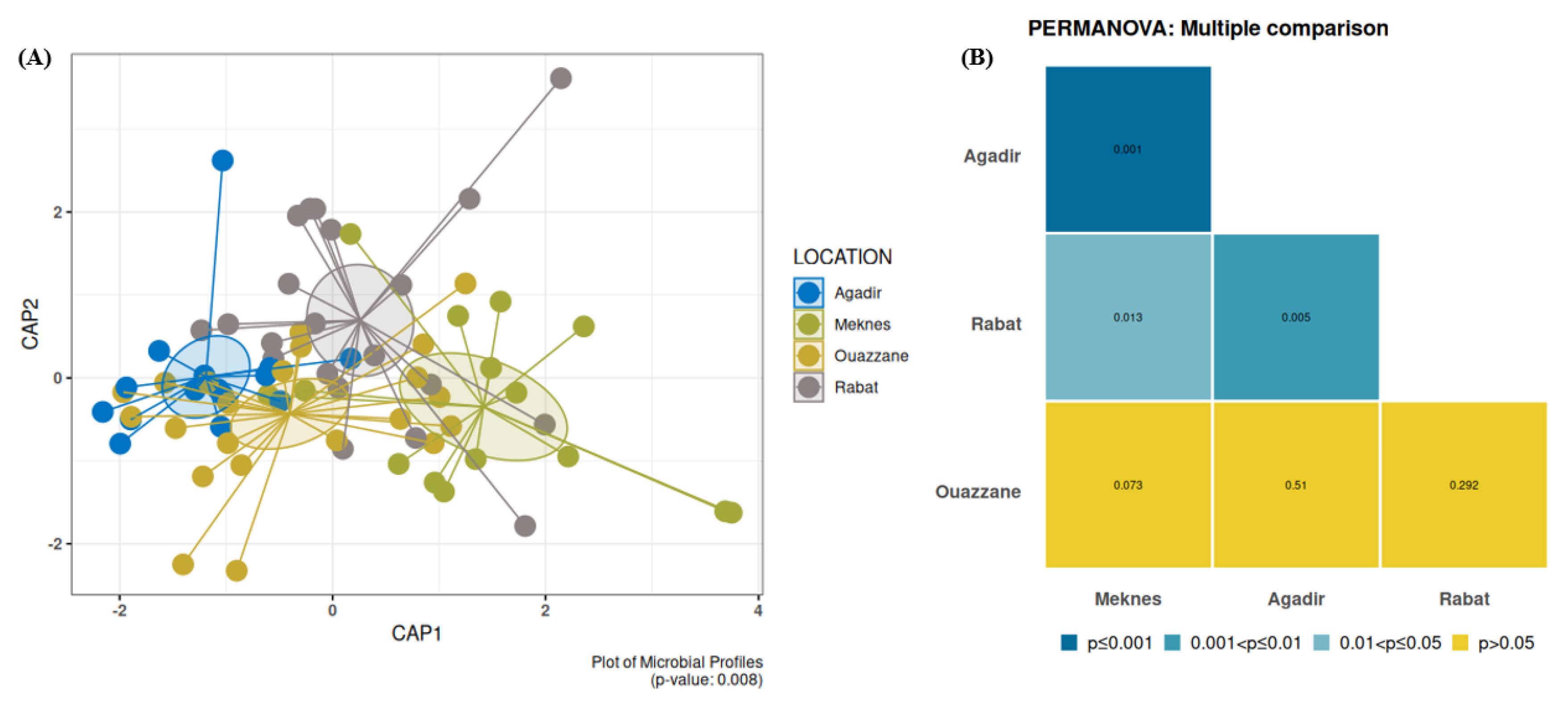

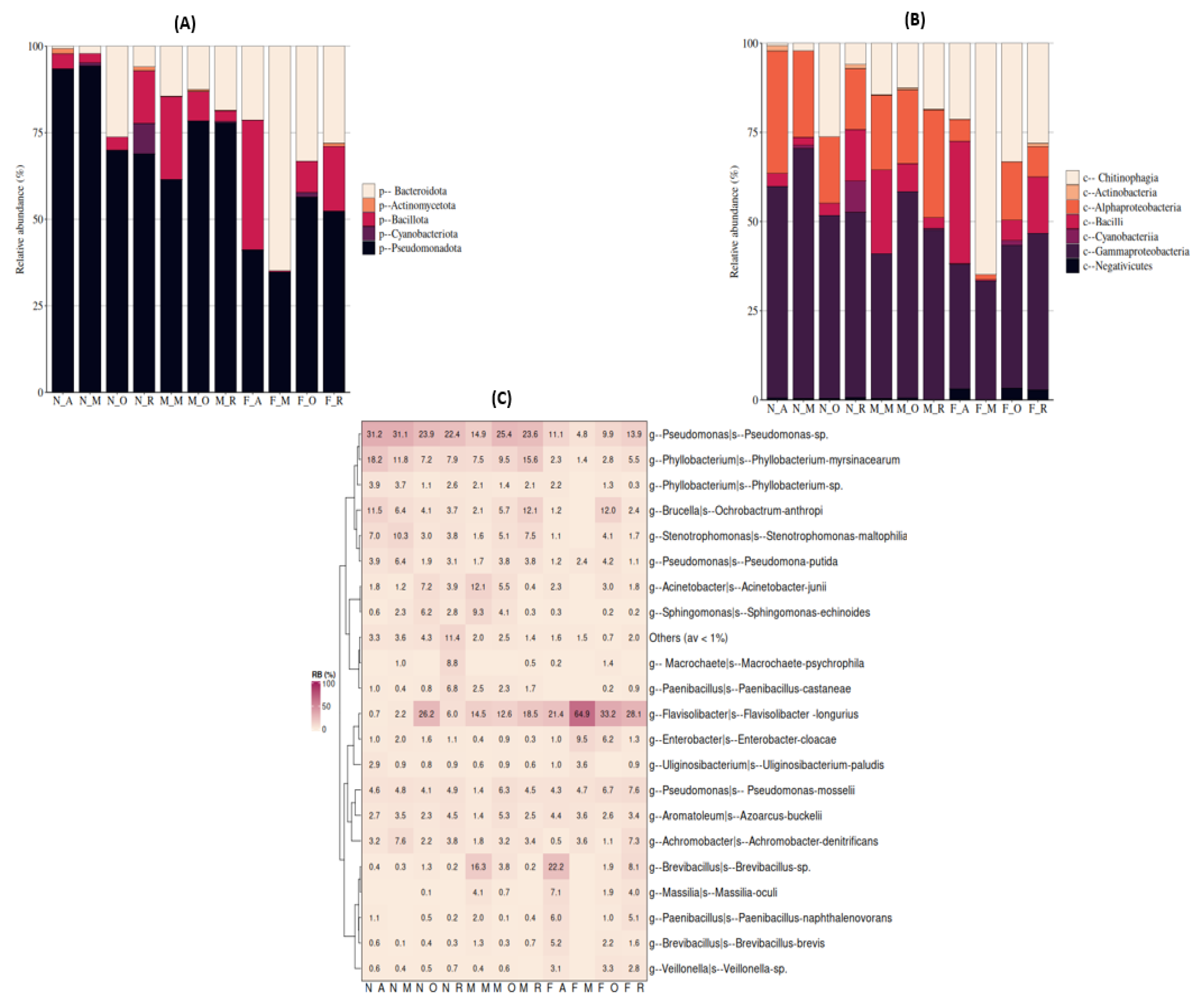

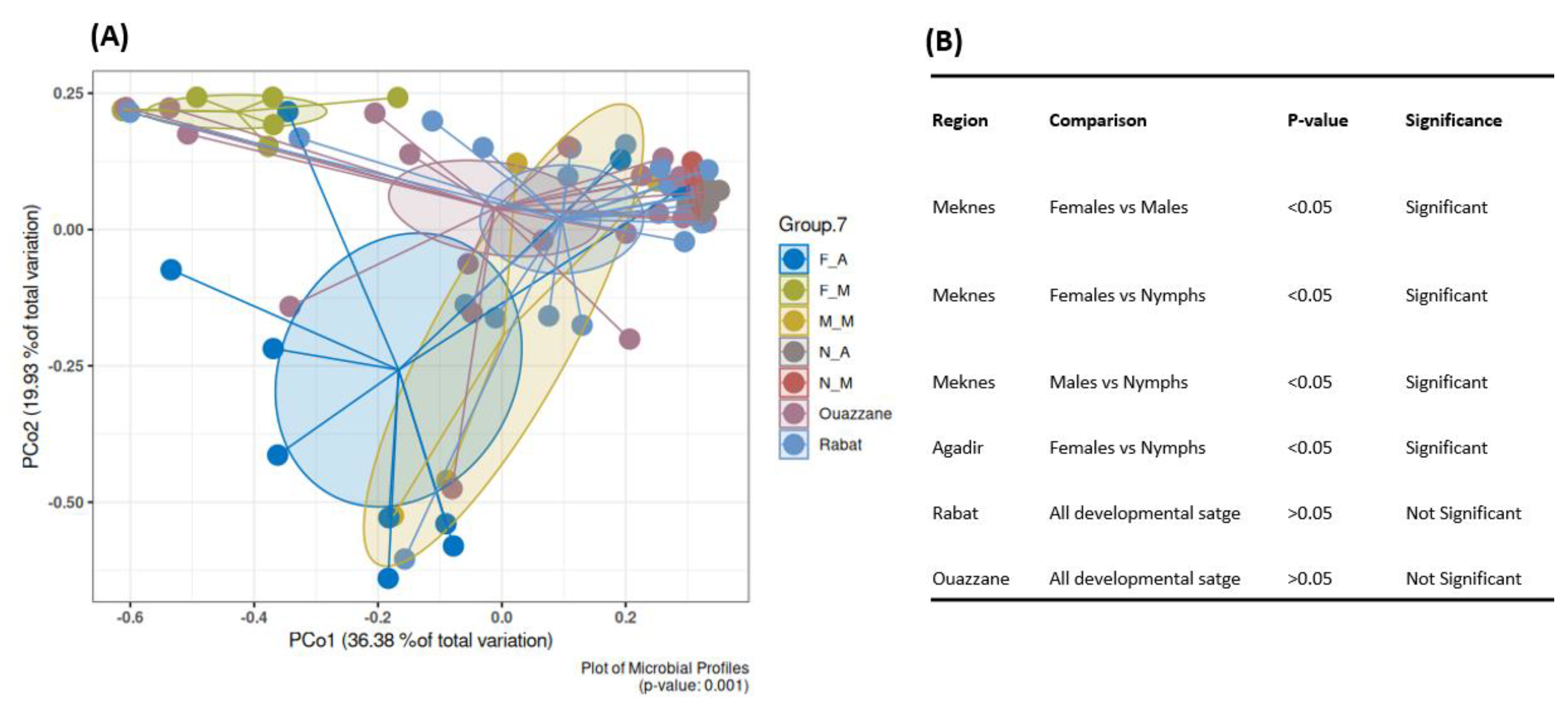

Dactylopius opuntiae (Cockerell) (Hemiptera: Dactylopiidae), the wild cochineal scale, is a major pest of prickly pear crops worldwide. This study characterized the bacterial community structure of D. opuntiae from four Moroccan regions using targeted PCR and full-length 16S rRNA MinION sequencing. We report the first detection of Wolbachia (16.6% prevalence) in D. opuntiae, with infection rates varying geographically from 0% (Rabat) to 53.3% (Ouazzane). Spiroplasma was detected at a lower prevalence (3.3%) and exclusively in males. Phylogenetic analysis placed the Wolbachia strains in supergroup B and Spiroplasma in the poulsonii-citri complex. MinION sequencing revealed Candidatus Dactylopiibacterium as the dominant taxon (97.7%), consistent with its role as an obligate symbiont. After removing this dominant species, we uncovered a diverse bacterial community, including Flavisolibacter, Pseudomonas, Phyllobacterium, Acinetobacter, and Brevibacillus. Beta diversity analysis showed significant geographic variation (PERMANOVA p<0.008), with distinct communities across regions. Females harbored a more specialized microbiome dominated by Flavisolibacter (except in Agadir), whereas males and nymphs showed Pseudomonas dominance. Core microbiome analysis revealed no universal genera across all groups, with females displaying a more restricted core than males and nymphs did. The detection of reproductive symbionts, combined with geographic and sex-specific microbiome patterns, provides insights into the development of microbiome-based pest management strategies. The complementary use of targeted and untargeted sequencing methods is essential for comprehensive microbiome characterization in this economically important pest.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Dactylopius Opuntiae Collection and DNA Isolation

|

Region |

Coordinates |

Collection date |

Treatment |

No. of insects | ||||

| Latitude | Longitude | Temperature | N | F | M | |||

|

Agadir |

30.206132 | -9.534147 | 20◦C | Oct. 2022 | Insecticide | 5 | 10 | - |

| Rabat | 34.002736 | -6.748109 | 22◦C | Nov. 2022 | Burned | 10 | 6 | 5 |

|

Meknes |

33.963659 | -5.576012 | 24◦C | Sept. 2022 | Burned | 4 | 7 | 4 |

| Ouazzane | 34.807449 | -5.658892 | 18◦C | Dec. 2022 | No | 6 | 9 | 7 |

2.2. Screening and Identification of Bacterial Symbionts

2.3. Amplification of the 16S rRNA Gene, Library Preparation, and MinION Sequencing

2.4. Bioinformatics Analysis

2.5. Phylogenetic Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Infection Status of Reproductive Symbionts in Natural Populations of D. opuntiae

3.1.1. Infection Prevalence

3.1.2. Phylogenetic Analysis of Wolbachia and Spiroplasma sequences in D. opuntiae populations

3.4. 16 S rRNA Amplicon Sequencing

3.4.1. Bacterial Diversity and Composition among D. opuntiae Natural Populations

3.4.2. Bacterial Diversity and Composition among D. opuntiae Gender and Developmental Stage, Excluding Candidatus Dactylopiibacterium

Bacterial Diversity

Bacterial Composition

Core Microbiome

4. Discussion

4.1. Infection Prevalence

4.2. Dynamics of the Bacterial Communities Associated with D. opuntiae across Geographical Locations

4.3. Gender-Based Differences in Bacterial Composition of D. opuntiae

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rodríguez, L.; Niemeyer, H.M. Cochineal Production: A Reviving Precolumbian industry. Athena Review 2001, 2(4), 76–78. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez Guerra, G. Biosystematics of the Family Dactylopiidae (Homoptera: Coccinea) with Emphasis on the Life Cycle of Dactylopius Coccus Costa. 1991.

- Klein, H. Biological Control of Invasive Cactus Species (Family Cactaceae). 2.2. Cochineal Insects (Dactylopius Spp.). PPRI Leaflet Series; Weeds Biocontrol, 2002; Vol. 2.2;

- Paterson, I.D.; Hoffmann, J.H.; Klein, H.; Mathenge, C.W.; Neser, S.; Zimmermann, H.G. Biological Control of Cactaceae in South Africa. afen 2011, 19, 230–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foldi, I. Liste des Cochenilles de France (Hemiptera, Coccoidea). 2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Dov, Y.; Sanchez-Garcia, I. New data on several species of scale insect (hemiptera: coccoidea) from southern spain 2015, 313–317.

- Bouharroud, R.; Amarraque, A.; Qessaoui, R. First Report of the Opuntia Cochineal Scale Dactylopius Opuntiae (Hemiptera: Dactylopiidae) in Morocco. EPPO Bulletin 2016, 46, 308–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moussa, Z.; Yammouni, D.; Azar, D. Dactylopius Opuntiae (Cockerell, 1896), a New Invasive Pest of the Cactus Plants Opuntia Ficus-Indica in the South of Lebanon (Hemiptera, Coccoidea, Dactylopiidae). 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, E.; Brito, C.; Albuquerque, I.; Batista, J. Desempenho Do O´leo de Laranja No Controle Da Cochonilhado-Carmim Em Palma Gigante. Engenharia Ambiental 2009, 6: 252-258.

- Badii, M.H.; Flores, A.E. Prickly Pear Cacti Pests And Their Control In Mexico. Florida Entomologist 2001, 503–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portillo, M.I.; Vigueras, A.L. A Review On The Cochineal Species In Mexico, Hosts And Natural Enemies. Acta Hortic. 2006, 249–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, J. Cactus-Feeding Insects and Mites. 1969.

- Vanegas-Rico, J.; Lomeli-Flores, R.; Rodríguez-Leyva, E.; Mora-Aguilera, G.; Valdez, J. Natural Enemies of Dactylopius Opuntiae (Cockerell) on Opuntia Ficus-Indica (L.) Miller in Central Mexico. 2010, 26, 415–433. [Google Scholar]

- Vanegas-Rico, J.; Lomeli-Flores, R.; Rodríguez-Leyva, E.; Pérez, A.; González-Hernández, H.; Marín-Jarillo, A. Hyperaspis Trifurcata (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae) y Sus Parasitoides En El Centro de México. Revista colombiana de entomología 2015, 41, 194–199. [Google Scholar]

- Ochoa, M.J.; Lobos, E.; Portillo, L.; Vigueras, A.L. Importance Of Biotic Factors And Impact On Cactus Pear Production Systems. Acta Hortic. 2015, 327–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, D.; Farias, I.; Lira, M.; Santos, M.; Arruda, G. Manejo e Utilizaçao Da Palma Forrageira (Opuntiae Nopalea) Em Pernambuco. IPA, Recife, 2006.

- Torres, J.B.; Giorgi, J.A. Management of the False Carmine Cochineal Dactylopius Opuntiae (Cockerell): Perspective from Pernambuco State, Brazil. Phytoparasitica 2018, 46, 331–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochoa; Barbera History and Economic and Agroecological Importance. Crop Ecology, Cultivation and Uses of Cactus Pear (Ed. by P Inglese, C Mondragon, A Nefzaoui & C Saenz)Pp. 1–11. FAO,; Rome, Italy, 2017. ISBN 978-92-5-109860-8.

- Bouharroud, R.; Sbaghi, M.; Boujghagh, M.; El Bouhssini, M. Biological Control of the Prickly Pear Cochineal Dactylopius Opuntiae Cockerell (Hemiptera: Dactylopiidae). EPPO Bulletin 2018, 48, 300–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Aalaoui, M.; Bouharroud, R.; Sbaghi, M.; El Bouhssini, M.; Hilali, L.; Dari, K. Comparative Toxicity of Different Chemical and Biological Insecticides against the Scale Insect Dactylopius Opuntiae and Their Side Effects on the Predator Cryptolaemus Montrouzieri. Archives of Phytopathology and Plant Protection 2019, 52, 155–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Aalaoui, M.; Bouharroud, R.; Sbaghi, M.; El Bouhssini, M.; Hilali, L. Predatory Potential of Eleven Native Moroccan Adult Ladybird Species on Different Stages of Dactylopius Opuntiae (Cockerell) (Hemiptera: Dactylopiidae). EPPO Bulletin 2019, 49, 374–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sbaghi, M.; Bouharroud, R.; Boujghagh, M.; Bouhssini, M.E. Sources de Résistance d’Opuntia Spp. Contre La Cochenille à Carmin, Dactylopius Opuntiae, Au Maroc. EPPO Bulletin 2019, 49, 585–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramdani, C.; Bouharroud, R.; Sbaghi, M.; Mesfioui, A.; El Bouhssini, M. Field and Laboratory Evaluations of Different Botanical Insecticides for the Control of Dactylopius Opuntiae (Cockerell) on Cactus Pear in Morocco. Int J Trop Insect Sci 2021, 41, 1623–1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramdani, C.; El Fakhouri, K.; Sbaghi, M.; Bouharroud, R.; Boulamtat, R.; Aasfar, A.; Mesfioui, A.; El Bouhssini, M. Chemical Composition and Insecticidal Potential of Six Essential Oils from Morocco against Dactylopius Opuntiae (Cockerell) under Field and Laboratory Conditions. Insects 2021, 12, 1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, A.E. Symbiotic Microorganisms: Untapped Resources for Insect Pest Control. Trends in Biotechnology 2007, 25, 338–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumann, P. Biology Of Bacteriocyte-Associated Endosymbionts Of Plant Sap-Sucking Insects. Annual Review of Microbiology 2005, 59, 155–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zchori-Fein, E.; Bourtzis, K. Manipulative Tenants: Bacteria Associated with Arthropods; CRC Press, 2011. ISBN 978-1-4398-2749-9.

- Buchner, P. Endosymbiosis of Animals with Plant Microorganisms; Wiley, 1965. ISBN 978-0-470-11517-6.

- Zug, R.; Hammerstein, P. Still a Host of Hosts for Wolbachia: Analysis of Recent Data Suggests That 40% of Terrestrial Arthropod Species Are Infected. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e38544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilgenboecker, K.; Hammerstein, P.; Schlattmann, P.; Telschow, A.; Werren, J.H. How Many Species Are Infected with Wolbachia? – A Statistical Analysis of Current Data: Wolbachia Infection Rates. FEMS Microbiology Letters 2008, 281, 215–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, J.-T.; Li, T.-P.; Wang, M.-K.; Hong, X.-Y. Wolbachia-Based Strategies for Control of Agricultural Pests. Current Opinion in Insect Science 2023, 57, 101039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikolouli, K.; Colinet, H.; Renault, D.; Enriquez, T.; Mouton, L.; Gibert, P.; Sassu, F.; Cáceres, C.; Stauffer, C.; Pereira, R.; et al. Sterile Insect Technique and Wolbachia Symbiosis as Potential Tools for the Control of the Invasive Species Drosophila Suzukii. J Pest Sci 2018, 91, 489–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goryacheva, I.; Blekhman, A.; Andrianov, B.; Romanov, D.; Zakharov, I. Spiroplasma Infection in Harmonia Axyridis - Diversity and Multiple Infection. PLOS ONE 2018, 13, e0198190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duron, O.; Bouchon, D.; Boutin, S.; Bellamy, L.; Zhou, L.; Engelstädter, J.; Hurst, G.D. The Diversity of Reproductive Parasites among Arthropods: Wolbachia Do Not Walk Alone. BMC Biol 2008, 6, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hackett, K.; Clark, T. Ecology of Spiroplasmas.In: Whitcomb RF, Tully JG:Editors. The Mycoplasmas. New York: Academic Press 1979, 113–200.

- Bolaños, L.; Servín-Garcidueñas, L.; Martínez-Romero, E. Arthropod-Spiroplasma Relationship in the Genomic Era. FEMS microbiology ecology 2015, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heyworth, E.R.; Ferrari, J. A Facultative Endosymbiont in Aphids Can Provide Diverse Ecological Benefits. J Evol Biol 2015, 28, 1753–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frago, E.; Mala, M.; Weldegergis, B.T.; Yang, C.; McLean, A.; Godfray, H.C.J.; Gols, R.; Dicke, M. Symbionts Protect Aphids from Parasitic Wasps by Attenuating Herbivore-Induced Plant Volatiles. Nat Commun 2017, 8, 1860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guidolin, A.; Cataldi, T.; Labate, C.; Francis, F.; Cônsoli, F. Spiroplasma Affects Host Aphid Proteomics Feeding on Two Nutritional Resources. Scientific reports 2018, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, D.L.; Sakaguchi, B.; Hackett, K.J.; Whitcomb, R.F.; Tully, J.G.; Carle, P.; Bové, J.M.; Adams, J.R.; Konai, M.; Henegar, R.B. Spiroplasma Poulsonii Sp. Nov., a New Species Associated with Male-Lethality in Drosophila Willistoni, a Neotropical Species of Fruit Fly. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology 1999, 49, 611–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anbutsu, H.; Fukatsu, T. Tissue-Specific Infection Dynamics of Male-Killing and Nonmale-Killing Spiroplasmas in Drosophila Melanogaster. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 2006, 57, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiggins, F.M.; Hurst, G.D.; Jiggins, C.D.; v d Schulenburg, J.H.; Majerus, M.E. The Butterfly Danaus Chrysippus Is Infected by a Male-Killing Spiroplasma Bacterium. Parasitology 2000, 120 (Pt 5), 439–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majerus, T.; Graf von der Schulenburg, J.; Majerus, M.; Hurst, G. Molecular Identification of a Male-Killing Agent in the Ladybird Harmonia Axyridis (Pallas) (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae). Insect molecular biology 1999, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piché-Mongeon, V.; Guzman-Novoa, E. Pathogen Spillover from Honey Bees (Apis Mellifera L.) to Wild Bees in North America. Discov Anim 2024, 1, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitcomb, R.F.; Chen, T.A.; Williamson, D.L.; Liao, C.; Tully, J.G.; Bové, J.M.; Mouches, C.; Rose, D.L.; Coan, M.E.; Clark, T.B. Spiroplasma Kunkelii Sp. Nov.: Characterization of the Etiological Agent of Corn Stunt Disease. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology 1986, 36, 170–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastian, F.O.; Elzer, P.H.; Wu, X. Spiroplasma Spp. Biofilm Formation Is Instrumental for Their Role in the Pathogenesis of Plant, Insect and Animal Diseases. Exp Mol Pathol 2012, 93, 116–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- C, M.; Jm, B.; J, A.; Tb, C.; Jg, T. A Spiroplasma of Serogroup IV Causes a May-Disease-like Disorder of Honeybees in Southwestern France. Microbial ecology 1982, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, P.; Leong, L.; Koop, B.; Perlman, S. Transcriptional Responses in a Drosophila Defensive Symbiosis. Molecular ecology 2014, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takeo, Y.; Ayumi, T. Illustrations of Common Adult Ticks in the Mainland Japan. Bull. Hoshizaki Green Found 18, 2015, 287–305.

- Ml, K. A Checklist of the Ticks (Acari: Argasidae, Ixodidae) of Japan. Experimental & applied acarology 2018, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- H, M.; Vn, S.; Lb, K.; Gd, H. Male-Killing Spiroplasma Naturally Infecting Drosophila Melanogaster. Insect molecular biology 2005, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballinger, M.J.; Perlman, S.J. Generality of Toxins in Defensive Symbiosis: Ribosome-Inactivating Proteins and Defense against Parasitic Wasps in Drosophila. PLoS Pathogens 2017, 13, e1006431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łukasik, P.; Guo, H.; Van Asch, M.; Ferrari, J.; Godfray, H. Protection against a Fungal Pathogen Conferred by the Aphid Facultative Endosymbionts Rickettsia and Spiroplasma Is Expressed in Multiple Host Genotypes and Species and Is Not Influenced by Co-Infection with Another Symbiont. Journal of evolutionary biology 2013, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Vilchez, I.; Mateos, M. Spiroplasma Bacteria Enhance Survival of Drosophila Hydei Attacked by the Parasitic Wasp Leptopilina Heterotoma. PLoS One 2010, 5, e12149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laver, T.; Harrison, J.; O’Neill, P.A.; Moore, K.; Farbos, A.; Paszkiewicz, K.; Studholme, D.J. Assessing the Performance of the Oxford Nanopore Technologies MinION. Biomolecular Detection and Quantification 2015, 3, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chávez-Moreno, C.K.; Tecante, A.; Casas, A. The Opuntia (Cactaceae) and Dactylopius (Hemiptera: Dactylopiidae) in Mexico: A Historical Perspective of Use, Interaction and Distribution. Biodivers Conserv 2009, 18, 3337–3355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Puebla, S.T.; Ormeño-Orrillo, E.; Vera-Ponce de León, A.; Lozano, L.; Sanchez-Flores, A.; Rosenblueth, M.; Martínez-Romero, E. Genomes of Candidatus Wolbachia Bourtzisii wDacA and Candidatus Wolbachia Pipientis wDacB from the Cochineal Insect Dactylopius Coccus (Hemiptera: Dactylopiidae). G3 Genes|Genomes|Genetics 2016, 6, 3343–3349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vera-Ponce De León, A.; Ormeño-Orrillo, E.; Ramírez-Puebla, S.T.; Rosenblueth, M.; Degli Esposti, M.; Martínez-Romero, J.; Martínez-Romero, E. Candidatus Dactylopiibacterium Carminicum, a Nitrogen-Fixing Symbiont of Dactylopius Cochineal Insects (Hemiptera: Coccoidea: Dactylopiidae). Genome Biology and Evolution 2017, 9, 2237–2250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vera-Ponce León, A.; Dominguez-Mirazo, M.; Bustamante-Brito, R.; Higareda-Alvear, V.; Rosenblueth, M.; Martínez-Romero, E. Functional Genomics of a Spiroplasma Associated with the Carmine Cochineals Dactylopius Coccus and Dactylopius Opuntiae. BMC Genomics 2021, 22, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramírez-Puebla, S.T.; Rosenblueth, M.; Chávez-Moreno, C.K.; Catanho Pereira de Lyra, M.C.; Tecante, A.; Martínez-Romero, E. Molecular Phylogeny of the Genus Dactylopius (Hemiptera: Dactylopiidae) and Identification of the Symbiotic Bacteria. Environ Entomol 2010, 39, 1178–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augustinos, A.A.; Santos-Garcia, D.; Dionyssopoulou, E.; Moreira, M.; Papapanagiotou, A.; Scarvelakis, M.; Doudoumis, V.; Ramos, S.; Aguiar, A.F.; Borges, P.A.V.; et al. Detection and Characterization of Wolbachia Infections in Natural Populations of Aphids: Is the Hidden Diversity Fully Unraveled? PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e28695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartley, J. PEG Precipitation for Selective Removal of Small DNA Fragments. Focus 1996, 18, 27. [Google Scholar]

- Ligation Sequencing Amplicons - Native Barcoding Kit 96 V14 (SQK-NBD114.96) (NBA_9170_v114_revN_15Sep2022). Available online: https://nanoporetech.com/document/ligation-sequencing-amplicons-native-barcoding-v14-sqk-nbd114-96 (accessed on 21 October 2024).

- Releases · Nanoporetech/Dorado. Available online: https://github.com/nanoporetech/dorado/releases (accessed on 29 October 2024).

- Wick, R.R.; Judd, L.M.; Gorrie, C.L.; Holt, K.E. Completing Bacterial Genome Assemblies with Multiplex MinION Sequencing. Microbial Genomics 2017, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Coster, W.; D’Hert, S.; Schultz, D.T.; Cruts, M.; Van Broeckhoven, C. NanoPack: Visualizing and Processing Long-Read Sequencing Data. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, 2666–2669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-Pérez, H.; Ciuffreda, L.; Flores, C. NanoCLUST: A Species-Level Analysis of 16S rRNA Nanopore Sequencing Data. Bioinformatics 2021, 37, 1600–1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camacho, C.; Coulouris, G.; Avagyan, V.; Ma, N.; Papadopoulos, J.; Bealer, K.; Madden, T.L. BLAST+: Architecture and Applications. BMC Bioinformatics 2009, 10, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quast, C.; Pruesse, E.; Yilmaz, P.; Gerken, J.; Schweer, T.; Yarza, P.; Peplies, J.; Glöckner, F.O. The SILVA Ribosomal RNA Gene Database Project: Improved Data Processing and Web-Based Tools. Nucleic Acids Research 2013, 41, D590–D596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollander, M.; Wolfe, D.A.; Chicken, E. Nonparametric Statistical Methods; Third edition.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc: Hoboken, New Jersey, 2014; ISBN 978-0-470-38737-5. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, M.J.; Willis, T.J. CANONICAL ANALYSIS OF PRINCIPAL COORDINATES: A USEFUL METHOD OF CONSTRAINED ORDINATION FOR ECOLOGY. Ecology 2003, 84, 511–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bel Mokhtar, N.; Asimakis, E.; Galiatsatos, I.; Maurady, A.; Stathopoulou, P.; Tsiamis, G. Development of MetaXplore: An Interactive Tool for Targeted Metagenomic Analysis. Current Issues in Molecular Biology 2024, 46, 4803–4814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edgar, R.C. MUSCLE: Multiple Sequence Alignment with High Accuracy and High Throughput. Nucleic Acids Res 2004, 32, 1792–1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Li, M.; Knyaz, C.; Tamura, K. MEGA X: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis across Computing Platforms. Molecular biology and evolution 2018, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefort, V.; Longueville, J.-E.; Gascuel, O. SMS: Smart Model Selection in PhyML. Mol Biol Evol 2017, 34, 2422–2424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akaike, H. Autoregressive Model Fitting for Control. Ann Inst Stat Math 1971, 23, 163–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, A.; T. Fuller, D.; Dougall, P.; Kumaragama, K.; Dhaniyala, S.; Sur, S. Application of Nanopore Sequencing for Accurate Identification of Bioaerosol-Derived Bacterial Colonies. Environmental Science: Atmospheres 2024, 4, 754–766. [CrossRef]

- Nolan, J.M.; Skujina, I.; Hurpy, G.; Tighe, A.J.; Whelan, C.; Teeling, E.C. Evaluation of Oxford Nanopore Technologies MinION Sequencer as a Novel Short Amplicon Metabarcoding Tool Using Arthropod Mock Sample and Irish Bat Diet Characterisation. Ecology and Evolution 2025, 15, e71333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pankewitz, F.; Zöllmer, A.; Hilker, M.; Gräser, Y. Presence of Wolbachia in Insect Eggs Containing Antimicrobially Active Anthraquinones. Microb Ecol 2007, 54, 713–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeyaprakash, A.; Hoy, M.A. Long PCR Improves Wolbachia DNA Amplification: Wsp Sequences Found in 76% of Sixty-Three Arthropod Species. Insect Mol Biol 2000, 9, 393–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zytynska, S.E.; Weisser, W.W. The Natural Occurrence of Secondary Bacterial Symbionts in Aphids. Ecological Entomology 2016, 41, 13–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, K.M.; Schiffer, M.; Griffin, P.C.; Lee, S.F.; Hoffmann, A.A. Tropical Drosophila Pandora Carry Wolbachia Infections Causing Cytoplasmic Incompatibility or Male Killing: MULTIPLE Wolbachia IN A TROPICAL Drosophila. Evolution 2016, 70, 1791–1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamm, C.A.; Begun, D.J.; Vo, A.; Smith, C.C.R.; Saelao, P.; Shaver, A.O.; Jaenike, J.; Turelli, M. Wolbachia Do Not Live by Reproductive Manipulation Alone: Infection Polymorphism in Drosophila Suzukii and D. Subpulchrella. Molecular Ecology 2014, 23, 4871–4885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mateos, M.; Castrezana, S.J.; Nankivell, B.J.; Estes, A.M.; Markow, T.A.; Moran, N.A. Heritable Endosymbionts of Drosophila. Genetics 2006, 174, 363–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourtzis, K.; Nirgianaki, A.; Markakis, G.; Savakis, C. Wolbachia Infection and Cytoplasmic Incompatibility in Drosophila Species. Genetics 1996, 144, 1063–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asimakis, E.D.; Doudoumis, V.; Hadapad, A.B.; Hire, R.S.; Batargias, C.; Niu, C.; Khan, M.; Bourtzis, K.; Tsiamis, G. Detection and Characterization of Bacterial Endosymbionts inSoutheast Asian Tephritid Fruit Fly Populations. BMC Microbiol 2019, 19, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateos, M.; Martinez, H.; Lanzavecchia, S.B.; Conte, C.; Guillén, K.; Morán-Aceves, B.M.; Toledo, J.; Liedo, P.; Asimakis, E.D.; Doudoumis, V.; et al. Wolbachia Pipientis Associated to Tephritid Fruit Fly Pests: From Basic Research to Applications 2018, 358333.

- Yong, H.-S.; Song, S.-L.; Chua, K.-O.; Lim, P.-E. Predominance of Wolbachia Endosymbiont in the Microbiota across Life Stages of Bactrocera Latifrons (Insecta: Tephritidae). Meta Gene 2017, 14, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuler, H.; Arthofer, W.; Riegler, M.; Bertheau, C.; Krumböck, S.; Köppler, K.; Vogt, H.; Teixeira, L.A.F.; Stauffer, C. Multiple Wolbachia Infections in Rhagoletis Pomonella. Entomologia Experimentalis et Applicata 2011, 139, 138–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarakatsanou, A.; Diamantidis, A.D.; Papanastasiou, S.A.; Bourtzis, K.; Papadopoulos, N.T. Effects of Wolbachia on Fitness of the Mediterranean Fruit Fly (Diptera: Tephritidae). Journal of Applied Entomology 2011, 135, 554–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Cui, L.; Li, Z. Diversity and Phylogeny of Wolbachia Infecting Bactrocera Dorsalis (Diptera: Tephritidae) Populations from China. Environmental Entomology 2007, 36, 1283–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torres-Llamas, A.; Díaz-Sáez, V.; Morales-Yuste, M.; Ibáñez-De Haro, P.; López-López, A.E.; Corpas-López, V.; Morillas-Márquez, F.; Martín-Sánchez, J. Assessing Wolbachia Circulation in Wild Populations of Phlebotomine Sand Flies from Spain and Morocco: Implications for Control of Leishmaniasis. Parasites Vectors 2025, 18, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordenstein, S.R.; Bordenstein, S.R. Temperature Affects the Tripartite Interactions between Bacteriophage WO, Wolbachia, and Cytoplasmic Incompatibility. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e29106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breeuwer, J.A.; Werren, J.H. Cytoplasmic Incompatibility and Bacterial Density in Nasonia Vitripennis. Genetics 1993, 135, 565–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutton, T.J.; Sinkins, S.P. Strain-specific Quantification of Wolbachia Density in Aedes Albopictus and Effects of Larval Rearing Conditions. Insect Molecular Biology 2004, 13, 317–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.Z.; De Barro, P.J.; Ren, S.-X.; Greeff, J.M.; Qiu, B.-L. Evidence for Horizontal Transmission of Secondary Endosymbionts in the Bemisia Tabaci Cryptic Species Complex. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e53084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huigens, M.E.; de Almeida, R.P.; Boons, P.A.H.; Luck, R.F.; Stouthamer, R. Natural Interspecific and Intraspecific Horizontal Transfer of Parthenogenesis–Inducing Wolbachia in Trichogramma Wasps. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 2004, 271, 509–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.Z.; Li, S.-J.; Xue, X.; Yin, X.-J.; Ren, S.-X.; Jiggins, F.M.; Greeff, J.M.; Qiu, B.-L. The Intracellular Bacterium Wolbachia Uses Parasitoid Wasps as Phoretic Vectors for Efficient Horizontal Transmission. PLoS Pathog 2015, 11, e1004672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.-J.; Ahmed, M.Z.; Lv, N.; Shi, P.-Q.; Wang, X.-M.; Huang, J.-L.; Qiu, B.-L. Plant–Mediated Horizontal Transmission of Wolbachia between Whiteflies. The ISME Journal 2017, 11, 1019–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, A.A.; Ross, P.A.; Rašić, G. Wolbachia Strains for Disease Control: Ecological and Evolutionary Considerations. Evol Appl 2015, 8, 751–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, G.L.; Rasgon, J.L. Transinfection: A Method to Investigate Wolbachia -Host Interactions and Control Arthropod-Borne Disease: Transinfection of Arthropods. Insect Mol Biol 2014, 23, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyritsis, G.A.; Koskinioti, P.; Bourtzis, K.; Papadopoulos, N.T. Effect of Wolbachia Infection and Adult Food on the Sexual Signaling of Males of the Mediterranean Fruit Fly Ceratitis Capitata. Insects 2022, 13, 737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabalou, S.; Apostolaki, A.; Livadaras, I.; Franz, G.; Robinson, A.S.; Savakis, C.; Bourtzis, K. Incompatible Insect Technique: Incompatible Males from a Ceratitis Capitata Genetic Sexing Strain. Entomologia Experimentalis et Applicata 2009, 132, 232–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabalou, S.; Riegler, M.; Theodorakopoulou, M.; Stauffer, C.; Savakis, C.; Bourtzis, K. Wolbachia-Induced Cytoplasmic Incompatibility as a Means for Insect Pest Population Control. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2004, 101, 15042–15045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, T.L.; Barton, N.H.; Rašić, G.; Turley, A.P.; Montgomery, B.L.; Iturbe-Ormaetxe, I.; Cook, P.E.; Ryan, P.A.; Ritchie, S.A.; Hoffmann, A.A.; et al. Local Introduction and Heterogeneous Spatial Spread of Dengue-Suppressing Wolbachia through an Urban Population of Aedes Aegypti. PLoS Biol 2017, 15, e2001894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMeniman, C.J.; Lane, R.V.; Cass, B.N.; Fong, A.W.C.; Sidhu, M.; Wang, Y.-F.; O’Neill, S.L. Stable Introduction of a Life-Shortening Wolbachia Infection into the Mosquito Aedes Aegypti. Science 2009, 323, 141–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffmann, A.A.; Montgomery, B.L.; Popovici, J.; Iturbe-Ormaetxe, I.; Johnson, P.H.; Muzzi, F.; Greenfield, M.; Durkan, M.; Leong, Y.S.; Dong, Y.; et al. Successful Establishment of Wolbachia in Aedes Populations to Suppress Dengue Transmission. Nature 2011, 476, 454–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Apostolaki, A.; Livadaras, I.; Saridaki, A.; Chrysargyris, A.; Savakis, C.; Bourtzis, K. Transinfection of the Olive Fruit Fly Bactrocera Oleae with Wolbachia: Towards a Symbiont-Based Population Control Strategy: Transinfection of Bactrocera Oleae with Wolbachia. Journal of Applied Entomology 2011, 135, 546–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ant, T.H.; Herd, C.; Louis, F.; Failloux, A.B.; Sinkins, S.P. Wolbachia Transinfections in Culex Quinquefasciatus Generate Cytoplasmic Incompatibility. Insect Mol Biol 2020, 29, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mateos, M.; Winter, L.; Winter, C.; Higareda-Alvear, V.M.; Martinez-Romero, E.; Xie, J. Independent Origins of Resistance or Susceptibility of Parasitic Wasps to a Defensive Symbiont. Ecology and Evolution 2016, 6, 2679–2687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaenike, J.; Unckless, R.; Cockburn, S.N.; Boelio, L.M.; Perlman, S.J. Adaptation via Symbiosis: Recent Spread of a Drosophila Defensive Symbiont. Science 2010, 329, 212–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harumoto, T.; Lemaitre, B. Male-Killing Toxin in a Bacterial Symbiont of Drosophila. Nature 2018, 557, 252–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eliautout, R.; Dubrana, M.-P.; Vincent-Monégat, C.; Vallier, A.; Braquart-Varnier, C.; Poirié, M.; Saillard, C.; Heddi, A.; Arricau-Bouvery, N. Immune Response and Survival of Circulifer Haematoceps to Spiroplasma Citri Infection Requires Expression of the Gene Hexamerin. Developmental & Comparative Immunology 2016, 54, 7–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herren, J.K.; Lemaitre, B. Spiroplasma and Host Immunity: Activation of Humoral Immune Responses Increases Endosymbiont Load and Susceptibility to Certain Gram-Negative Bacterial Pathogens in Drosophila Melanogaster: Spiroplasma and Drosophila Host Immunity. Cellular Microbiology 2011, 13, 1385–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Chen, J.; Jiang, L.; Qiao, G. Diversity of Bacteria Associated with Hormaphidinae Aphids (Hemiptera: Aphididae). Insect Science 2021, 28, 165–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Towett-Kirui, S.; Morrow, J.L.; Close, S.; Royer, J.E.; Riegler, M. Bacterial Communities Are Less Diverse in a Strepsipteran Endoparasitoid than in Its Fruit Fly Hosts and Dominated by Wolbachia. Microb Ecol 2023, 86, 2120–2132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurek, T.; Reinhold-Hurek, B. Azoarcus Sp. Strain BH72 as a Model for Nitrogen-Fixing Grass Endophytes. Journal of Biotechnology 2003, 106, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustamante-Brito, R.; Vera-Ponce De León, A.; Rosenblueth, M.; Martínez-Romero, J.; Martínez-Romero, E. Metatranscriptomic Analysis of the Bacterial Symbiont Dactylopiibacterium Carminicum from the Carmine Cochineal Dactylopius Coccus (Hemiptera: Coccoidea: Dactylopiidae). Life 2019, 9, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Zhang, X.; Chen, Z.; Wang, Z.; Lu, Y.; Cheng, D. The Divergence in Bacterial Components Associated with Bactrocera Dorsalis across Developmental Stages. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.-J.; Kang, M.-S.; Kim, G.S.; Lee, C.S.; Lim, S.; Lee, J.; Roh, S.H.; Kang, H.; Ha, J.M.; Bae, S.; et al. Flavisolibacter Tropicus Sp. Nov., Isolated from Tropical Soil. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology 2016, 66, 3413–3419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.-D.; Zhou, X.-K.; Mo, M.-H.; Jiao, J.-Y.; Yang, D.-Q.; Li, W.-J.; Zhang, T.-K.; Qin, S.-C.; Duan, Y.-Q. Flavisolibacter nicotiana Nov. , Isolated from Rhizosphere Soil of Nicotiana Tabacum L. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology 2019, 69, 2082–2088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maeng, S.; Park, Y.; Lee, S.E.; Han, J.H.; Bai, J.; Kim, M.K. Flavisolibacter Longurius Sp. Nov., Isolated from Soil. Arch Microbiol 2021, 203, 2825–2830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baik, K.S.; Kim, M.S.; Lee, J.H.; Lee, S.S.; Im, W.-T.; Seong, C.N. Flavisolibacter rigui sp. Nov., Isolated from Freshwater of an Artificial Reservoir and Emended Description of the Genus Flavisolibacter. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology 2014, 64, 4038–4042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, D.T.; Mitchum, M.G.; Zhang, S.; Wallace, J.G.; Li, Z. Soybean Microbiome Composition and the Impact of Host Plant Resistance. Front Plant Sci 2023, 14, 1326882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholson, W.L. Roles of Bacillus Endospores in the Environment: CMLS, Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2002, 59, 410–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shida, O.; Takagi, H.; Kadowaki, K.; Komagata, K. Proposal for Two New Genera, Brevibacillus Gen. Nov. and Aneurinibacillus Gen. Nov. International Journal of Systematic Bacteriology 1996, 46, 939–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Oliveira, E.J.; Rabinovitch, L.; Monnerat, R.G.; Passos, L.K.J.; Zahner, V. Molecular Characterization of Brevibacillus Laterosporus and Its Potential Use in Biological Control. Appl Environ Microbiol 2004, 70, 6657–6664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silby, M.W.; Winstanley, C.; Godfrey, S.A.C.; Levy, S.B.; Jackson, R.W. Pseudomonas Genomes: Diverse and Adaptable. FEMS Microbiol Rev 2011, 35, 652–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crone, S.; Vives-Flórez, M.; Kvich, L.; Saunders, A.M.; Malone, M.; Nicolaisen, M.H.; Martínez-García, E.; Rojas-Acosta, C.; Catalina Gomez-Puerto, M.; Calum, H.; et al. The Environmental Occurrence of Pseudomonas Aeruginosa. APMIS 2020, 128, 220–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mercado-Blanco, J.; Bakker, P.A.H.M. Interactions between Plants and Beneficial Pseudomonas Spp.: Exploiting Bacterial Traits for Crop Protection. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek 2007, 92, 367–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xin, X.-F.; Kvitko, B.; He, S.Y. Pseudomonas Syringae: What It Takes to Be a Pathogen. Nat Rev Microbiol 2018, 16, 316–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramos, J.-L. Pseudomonas: Volume 7: New Aspects of Pseudomonas Biology; Goldberg, J.B., Filloux, A., Eds.; SpringerLink Bücher; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht s.l, 2015; ISBN 978-94-017-9554-8. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.R.; Lee, H.M.; Yu, H.C.; Jeon, E.; Lee, S.; Li, J.; Kim, D.-H. Biodegradation of Polystyrene by Pseudomonas Sp. Isolated from the Gut of Superworms (Larvae of Zophobas Atratus ). Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 6987–6996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huszczynski, S.M.; Lam, J.S.; Khursigara, C.M. The Role of Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Lipopolysaccharide in Bacterial Pathogenesis and Physiology. Pathogens 2019, 9, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hrynkiewicz, K.; Baum, C.; Leinweber, P. Density, Metabolic Activity, and Identity of Cultivable Rhizosphere Bacteria on Salix Viminalis in Disturbed Arable and Landfill Soils. Z. Pflanzenernähr. Bodenk. 2010, 173, 747–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grönemeyer, J.L.; Burbano, C.S.; Hurek, T.; Reinhold-Hurek, B. Isolation and Characterization of Root-Associated Bacteria from Agricultural Crops in the Kavango Region of Namibia. Plant Soil 2012, 356, 67–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, K.; Ulrich, A.; Ewald, D. Diversity of Endophytic Bacterial Communities in Poplar Grown under Field Conditions: Endophytic Bacteria in Poplar. FEMS Microbiology Ecology 2008, 63, 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Q.; Zhu, G.; Qiu, H.; Li, M.; Zhang, J.; Wu, X.; Xiao, R.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, W.; Tian, B.; et al. Quality Traits Drive the Enrichment of Massilia in the Rhizosphere to Improve Soybean Oil Content. Microbiome 2024, 12, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Towner, K. The Genus Acinetobacter. In The Prokaryotes; Dworkin, M., Falkow, S., Rosenberg, E., Schleifer, K.-H., Stackebrandt, E., Eds.; Springer New York: New York, NY, 2006; pp. 746–758. ISBN 978-0-387-25496-8. [Google Scholar]

- Doughari, H.J.; Ndakidemi, P.A.; Human, I.S.; Benade, S. The Ecology, Biology and Pathogenesis of Acinetobacter Spp.: An Overview. Microb. Environ. 2011, 26, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sand, M.; De Berardinis, V.; Mingote, A.; Santos, H.; Göttig, S.; Müller, V.; Averhoff, B. Salt Adaptation in Acinetobacter Baylyi: Identification and Characterization of a Secondary Glycine Betaine Transporter. Arch Microbiol 2011, 193, 723–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, R.; Dong, C.; Wang, S.; Danso, B.; Dar, M.A.; Pandit, R.S.; Pawar, K.D.; Geng, A.; Zhu, D.; Li, X.; et al. Host-Specific Diversity of Culturable Bacteria in the Gut Systems of Fungus-Growing Termites and Their Potential Functions towards Lignocellulose Bioconversion. Insects 2023, 14, 403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourramezan, Z.; Ghezelbash, G.R.; Romani, B.; Ziaei, S.; Hedayatkhah, A. Screening and Identification of Newly Isolated Cellulose-Degrading Bacteria from the Gut of Xylophagous Termite Microcerotermes Diversus (Silvestri). Mikrobiologiia 2012, 81, 796–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Dexter, S.; Boopathy, R. Biodegradation of Phenol by Acinetobacter Tandoii Isolated from the Gut of the Termite. Environ Sci Pollut Res 2019, 26, 34067–34072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banerjee, S.; Maiti, T.K.; Roy, R.N. Production, Purification, and Characterization of Cellulase from Acinetobacter Junii GAC 16.2, a Novel Cellulolytic Gut Isolate of Gryllotalpa Africana, and Its Effects on Cotton Fiber and Sawdust. Ann Microbiol 2020, 70, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Lin, X.; Guo, X. The Role of Insect Symbiotic Bacteria in Metabolizing Phytochemicals and Agrochemicals. Insects 2022, 13, 583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, M.; Andrews, M.E. Specificity in Legume-Rhizobia Symbioses. IJMS 2017, 18, 705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asaf, S.; Numan, M.; Khan, A.L.; Al-Harrasi, A. Sphingomonas: From Diversity and Genomics to Functional Role in Environmental Remediation and Plant Growth. Critical Reviews in Biotechnology 2020, 40, 138–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, F.B.; Shan, S.D.; Luo, L.P.; Guan, L.B.; Qin, H. Isolation and Characterization of a Sphingomonas Sp. Strain F-7 Degrading Fenvalerate and Its Use in Bioremediation of Contaminated Soil. Journal of Environmental Science and Health, Part B 2013, 48, 198–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Wong, M.H.; Wong, Y.S.; Tam, N.F.Y. Multi-Factors on Biodegradation Kinetics of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) by Sphingomonas Sp. a Bacterial Strain Isolated from Mangrove Sediment. Marine Pollution Bulletin 2008, 57, 695–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halo, B.A.; Khan, A.L.; Waqas, M.; Al-Harrasi, A.; Hussain, J.; Ali, L.; Adnan, M.; Lee, I.-J. Endophytic Bacteria ( Sphingomonas Sp. LK11) and Gibberellin Can Improve Solanum Lycopersicum Growth and Oxidative Stress under Salinity. Journal of Plant Interactions 2015, 10, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilewicz, M.; Not Available, N.A.; Nadalig, T.; Budzinski, H.; Doumenq, P.; Michotey, V.; Bertrand, J.C. Isolation and Characterization of a Marine Bacterium Capable of Utilizing 2-Methylphenanthrene. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology 1997, 48, 528–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daane, L.L.; Harjono, I.; Zylstra, G.J.; Häggblom, M.M. Isolation and Characterization of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbon-Degrading Bacteria Associated with the Rhizosphere of Salt Marsh Plants. Appl Environ Microbiol 2001, 67, 2683–2691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, N.; Li, R.; Cheng, S.; Zhang, L.; Liang, P.; Gao, X. The Gut Symbiont Sphingomonas Mediates Imidacloprid Resistance in the Important Agricultural Insect Pest Aphis Gossypii Glover. BMC Biol 2023, 21, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wang, G.; Li, Z.; Lai, X.; Yang, B.; Chen, B.; Du, G. The Gut Microbial Community Structure of the Oriental Armyworm Mythimna Separata (Walker) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) Affects the the Virulence of the Entomopathogenic Fungus Metarhizium Rileyi. BMC Microbiology 2025, 25, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Wu, P.; Cui, S.; Ali, A.; Zheng, G. Divergence in Gut Bacterial Community between Females and Males in the Wolf Spider Pardosa Astrigera. Ecology and Evolution 2022, 12, e8823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Liu, X.; Ruan, Y. Sex-Specific Differences in Symbiotic Microorganisms Associated with an Invasive Mealybug ( Phenacoccus Solenopsis Tinsley) Based on 16S Ribosomal DNA. PeerJ 2023, 11, e15843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toju, H.; Fukatsu, T. Diversity and Infection Prevalence of Endosymbionts in Natural Populations of the Chestnut Weevil: Relevance of Local Climate and Host Plants: Endosymbionts In Weevil Populations. Molecular Ecology 2011, 20, 853–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simhadri, R.K.; Fast, E.M.; Guo, R.; Schultz, M.J.; Vaisman, N.; Ortiz, L.; Bybee, J.; Slatko, B.E.; Frydman, H.M. The Gut Commensal Microbiome of Drosophila Melanogaster Is Modified by the Endosymbiont Wolbachia. mSphere 2017, 2, e00287-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).