1. Introduction

Autophagy is a fundamental catabolic process in eukaryotic cells, whereby cytoplasmic material destined for degradation is sequestered and delivered to lysosomes. Depending on the type of autophagy, this occurs through distinct mechanisms. Once inside the lysosome, macromolecules are broken down by acidic hydrolases, and the resulting components are recycled to fuel anabolic pathways and energy production [

1,

2,

3]. Autophagy is therefore indispensable for maintaining cellular homeostasis [

4], removing dysfunctional organelles [

5], enabling appropriate stress responses [

6], eliminating intracellular pathogens [

7,

8,

9], and modulating the pace of aging [

10]. Impairments in autophagy have been linked to a wide array of degenerative conditions, including cancer, various neurodegenerative diseases, diabetes, tissue atrophy, and fibrosis [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. While certain autophagy pathways are organelle-selective (e.g., mitophagy or pexophagy) [

16], autophagy is mechanistically distinguished from the ubiquitin–proteasome system (UPS). The UPS specifically recognizes and degrades ubiquitin-tagged proteins, whereas autophagy non-specifically sequesters bulk regions of the cytoplasm for lysosomal degradation [

17].

Three principal forms of autophagy have been described: microautophagy, chaperone-mediated autophagy, and macroautophagy. Among these, macroautophagy (hereafter referred to simply as “autophagy”) is the most prominent, characterized by the encapsulation of cargo within a double-membraned vesicle known as the autophagosome. Subsequent fusion of the autophagosome with a lysosome yields an autolysosome, where enzymatic digestion of the cargo occurs. The autophagic process progresses through sequential stages—initiation, nucleation, expansion, lysosomal fusion, degradation, and recycling.

The master regulator of autophagy is the target of rapamycin (TOR) protein kinase. Under nutrient-rich conditions, TOR suppresses autophagy by inhibiting the initiation complex, whereas during starvation this inhibition is released. TOR exerts its regulatory effects through two main mechanisms: (i) hyperphosphorylation of key initiation complex components, thereby altering protein–protein interactions and preventing autophagosome nucleation, and (ii) modulation of downstream signaling cascades that govern the transcriptional and translational regulation of autophagy-related proteins [

3,

18,

19].

The nematode

Caenorhabditis elegans represents an excellent experimental model for studying autophagy. Its small size, short life cycle (reaching reproductive maturity in ~3 days at 22°C), and ease of laboratory maintenance make it particularly tractable. The transparency of its cuticle and the invariant cell lineage of development allow cell-specific tracking of fluorescently tagged transgenes [

20]. Furthermore, the predominance of hermaphrodites ensures the stable propagation of isogenic strains, while genetic crosses allow the generation of complex mutant backgrounds.

In

C. elegans, the autophagic response to starvation is mediated primarily through the TOR ortholog LET-363, which integrates signals from the insulin/IGF-1-like signaling (IIS) pathway. In nutrient-rich conditions, LET-363 represses autophagy, while under starvation, this repression is alleviated. Components of the IIS pathway, including the IGF-1 receptor homolog DAF-2 and the FoxO transcription factor homolog DAF-16, serve as critical modulators of this nutrient-sensitive regulation [

21,

22].

Fluorescent protein reporters remain one of the most widely used tools for monitoring autophagy. Typically, autophagy-related proteins are fused to green fluorescent protein (GFP) or to red fluorescent proteins such as mCherry, enabling visualization of autophagic structures [

23,

24]. Among these, the ATG8 homolog LGG-1 has been extensively used, as it associates with both nascent and mature autophagic membranes, thereby serving as a robust marker of autophagosome and autolysosome dynamics [

25]. However, current reporter systems are subject to several caveats, including multi-copy insertion at random genomic sites, variable expression, and pH-sensitivity of GFP that limits detection of late-stage autophagic compartments [

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31].

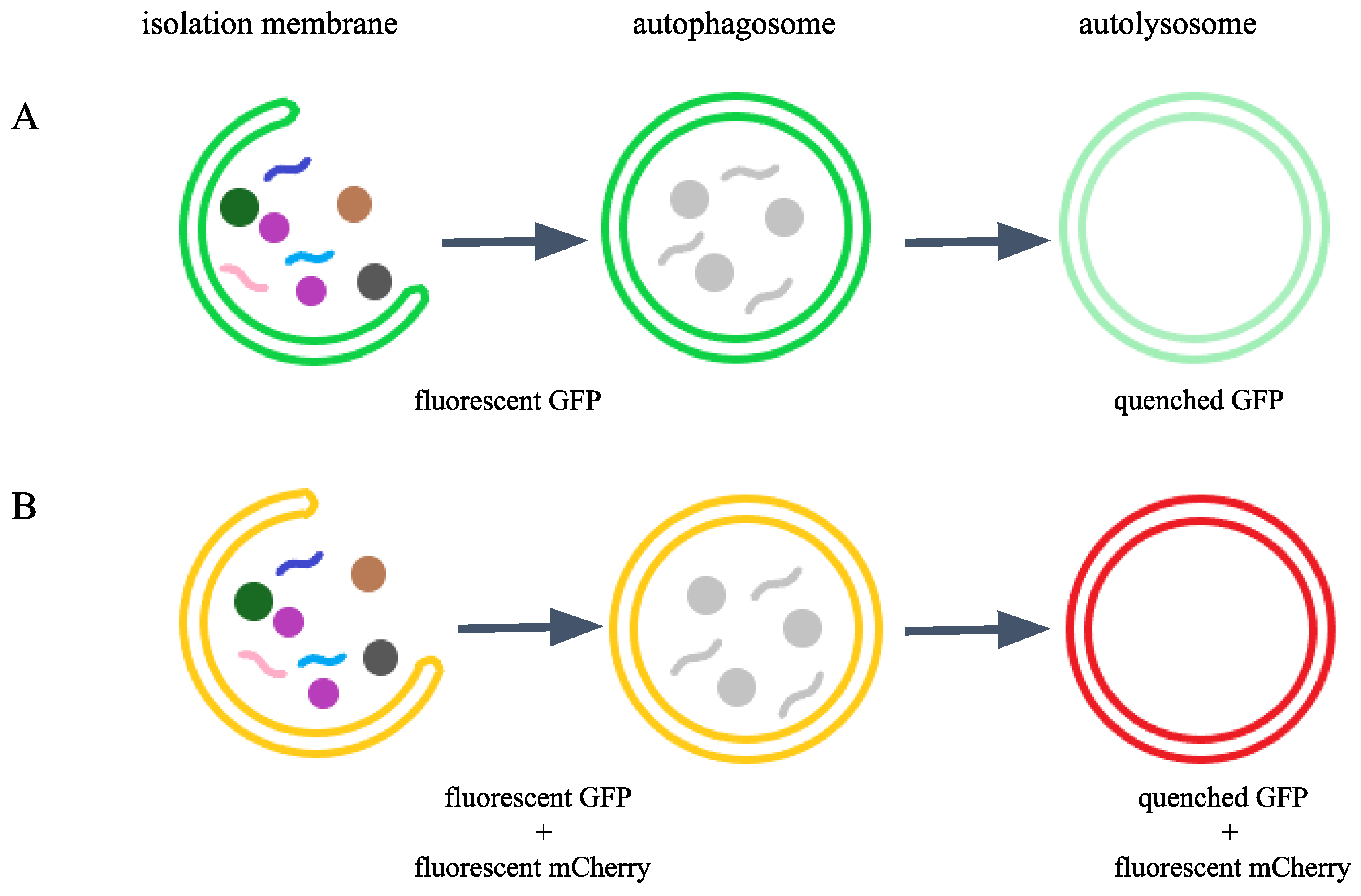

Meléndez et al. were the first to generate a

C. elegans strain expressing GFP::LGG-1 (DA2123: adIs2122 [

lgg-1p::GFP::lgg-1 + rol-6(su1006)]) [

25]. The number of GFP::LGG-1–positive structures changes dynamically throughout all developmental stages of

C. elegans under normal conditions. However, this strain also displays strong background fluorescence, which complicates the detection of specific structures. Under conditions influencing autophagic activity, such as starvation, the number of GFP::LGG-1–positive foci slightly increases [

26], though often only negligibly and with high variability. While the number of GFP::LGG-1–labeled foci can indicate an increase in autophagic activity, the accumulation of autophagic structures may also result from a blockage in the process [

27,

28]. Because GFP is highly sensitive to acidic pH [

29], this reporter strain labels only pre-autophagosomal structures and autophagosomes, providing no information about autolysosomes (

Figure 1) [

30]. Autophagosome formation itself is a rapid process, and thus measurable autophagic activity quickly subsides after induction [

27]. Finally, the transgene is integrated as a multicopy array at a single genomic locus. Taken together, tracking the GFP::LGG-1 signal alone does not provide sufficient evidence regarding the direction or nature of changes in autophagic activity.

Chang et al. inserted the

mCherry gene into the LGG-1 reporter construct (MAH215: sqIs11 [

lgg-1p::mCherry::GFP::lgg-1 + rol-6]) [

27]. Dual labeling with GFP and mCherry enables not only the visualization of autophagosomes and autolysosomes but also their distinction. Specifically, autophagosomes appear yellow due to the combined GFP and mCherry signals, whereas autolysosomes appear only red, since GFP is unstable under the acidic pH of lysosomes and is degraded following autophagosome–lysosome fusion, resulting in the loss of the green signal from these structures (

Figure 1) [

27,

29].

To overcome these limitations, we set out to develop a precise, endogenous single-copy autophagy reporter system in

C. elegans. Specifically, we generated a GFP::mCherry::LGG-1 reporter line using CRISPR–Cas9, and additionally designed a GFP::ATG-5 reporter, given the essential role of ATG-5 in autophagosome formation and subsequent lysosomal fusion [

18,

28]. We validated these reporters by monitoring starvation-induced autophagy at multiple developmental stages, and further tested their responsiveness to mutations and RNA interference, as well as pharmacological inhibition using bafilomycin A1.

3. Discussion

Autophagy is a crucial mechanism for proper cellular function, and as such, the study of this process has received considerable attention in biological and medical research. It plays roles in maintaining cellular homeostasis [

3,

5], mediating stress responses [

6], regulating the aging process [

10], and eliminating various intracellular pathogens [

7]. One of the main regulators of autophagy is the TOR protein, which senses nutrient availability and modulates autophagic activity accordingly [

3,

18,

19]. Autophagy is a multistep process regulated primarily by ATG proteins [

18]. During the process, a portion of the cytoplasm is sequestered by a double-membrane autophagosome, and after fusion with the lysosome, the cellular components are degraded in the autolysosome and subsequently recycled back into the cytoplasm [

3,

18].

Due to its importance, autophagy has been studied from many different perspectives by numerous research groups. In

C. elegans, one of the most popular topics in autophagy research is aging and lifespan, with many publications devoted to this area. By contrast, the relationship between autophagy and starvation in

C. elegans remains less well explored, although it has been extensively studied in the fruit fly

Drosophila melanogaster [

50,

51,

52] and has also been investigated in mammals [

53]. Even in

C. elegans studies that mention starvation, its effect on autophagy is typically not the primary research focus [

30,

44,

54]. For a long time, research relied on tagging a single autophagy-related protein with a fluorophore, which alone was insufficient to provide an accurate picture of changes in autophagic activity. In recent years, however, the use of fluorescent reporter strains has become increasingly widespread. In 2017, Chang et al. published a construct tagged with not one but two fluorophores [

27]. This advancement made it possible not only to monitor changes in the number of autophagosomes but also autolysosomes, and to distinguish between the two structures. Their publication reported that the number of autophagosomes increases with age in the intestine, muscles, and pharynx, and to a lesser extent in neurons, while the number of autolysosomes increases until approximately day 3 of adulthood, after which it stagnates in intestinal and pharyngeal cells and decreases in muscles and neurons [

27]. These observations correlate with the age-associated decline in autophagic activity [

55].

In the present study, we investigated autophagy in

C. elegans, focusing primarily on its response to starvation, using two endogenous fluorescent reporters that we designed. Our custom reporter constructs allowed us to overcome problems associated with previously published strains. Such issues included the strong background signal of GFP::LGG-1 and its inability to label autolysosomes [

30], or in the case of the MAH215 strain (GFP::mCherry::LGG-1) [

27], the consequences of excessive expression due to the multicopy nature of the transgene. Our improved reporter system consisted of a GFP::mCherry::LGG-1 strain generated with the CRISPR/Cas9 system [

56] and a GFP::ATG-5 strain created using the same technique. Using these strains, we performed starvation and RNA interference experiments, as well as tested the effect of the autophagy inhibitor bafilomycin A1.

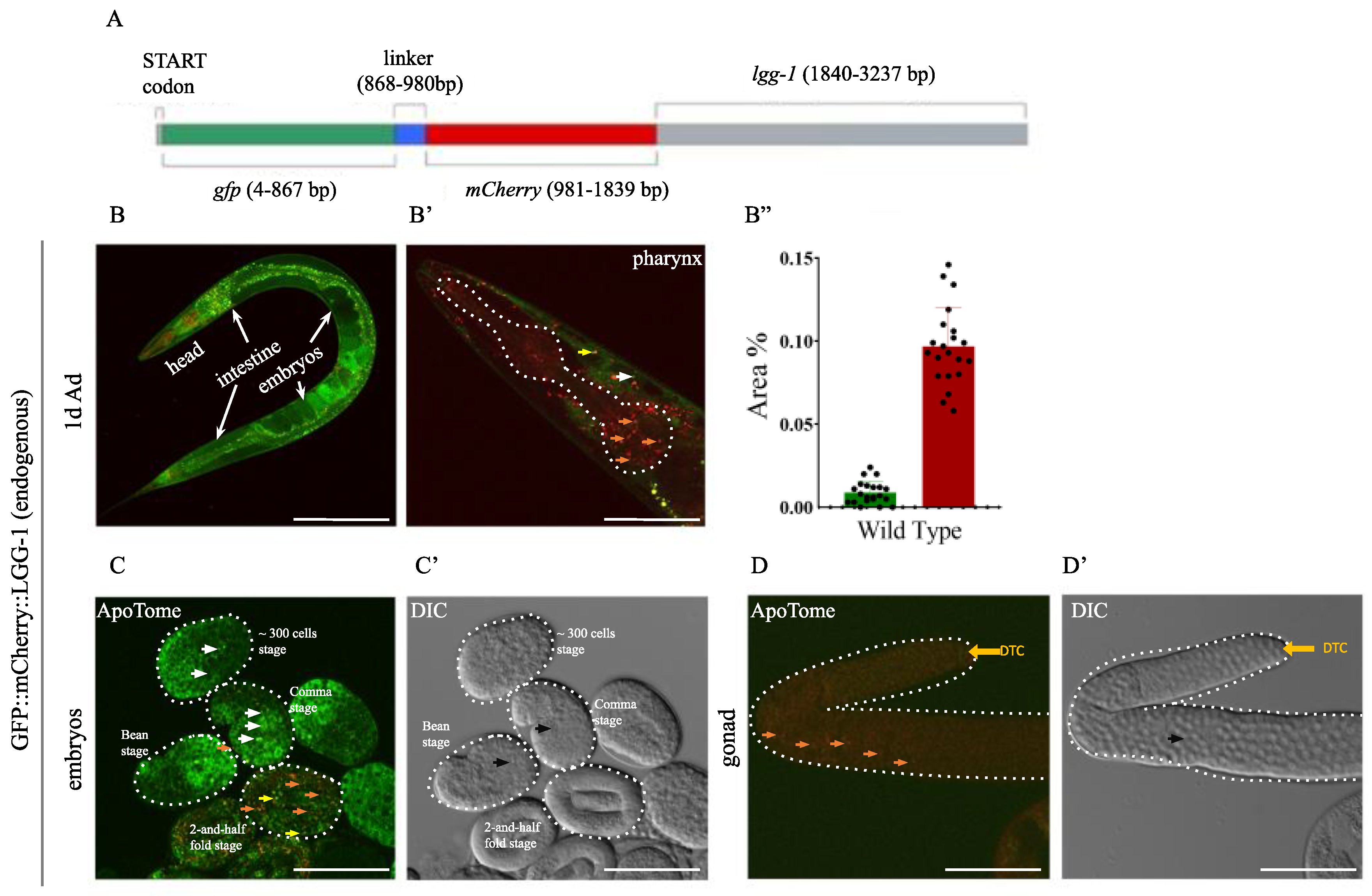

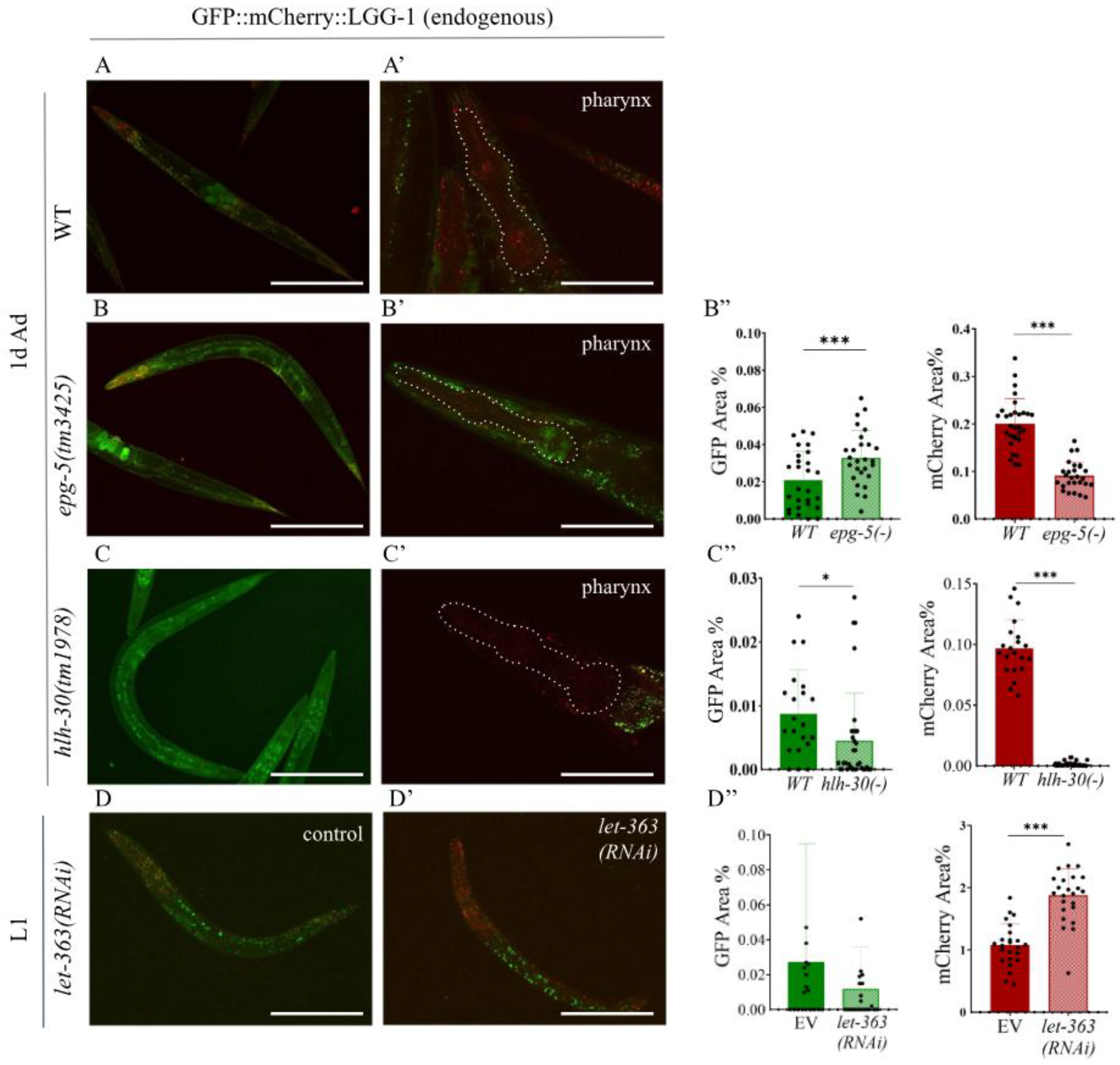

Our expression analyses revealed that the LGG-1 protein is expressed from the 300-cell stage of embryonic development (

Figure 2C). In adults, expression was observed in all cell types. In the absence of HLH-30, a protein required for starvation-induced activation of autophagy, GFP and mCherry expression were low (

Figure 3C-C’’), confirming the absence or very low level of autophagic activity. According to our findings, this process subsides during the first 24 hours of L1 arrest, consistent with the results of Kang et al. (2007). The further contribution of autophagic activity to survival is likely ensured by the recycling of autolysosomal contents, as suggested by the decline in autolysosome area observed during prolonged starvation. The decrease in detectable area may also be partly explained by the slower quenching of mCherry; however, this too would occur as a consequence of continuous lysosomal degradation. Strict suppression of autophagic activity may be essential for larvae arrested in early developmental stages. Since

C. elegans cell lineages follow invariant developmental programs, cell death caused by excessive autophagy would lead to irreparable tissue damage after refeeding. Importantly, no such abnormally developed animals were observed in our experiments. In contrast, starvation in adults did not result in such strict suppression. Even after the first 24 hours, low levels of autophagic activity could still be detected during prolonged starvation. This suggests a similar mode of regulation to that observed in the

Drosophila salivary gland and mammalian muscle cells, where a rapid autophagic response to short-term starvation is replaced by adaptive downregulation during prolonged starvation to protect tissues [

57,

58].

We also found that not only does the number of autolysosomes increase upon starvation, but this process can also proceed in the opposite direction: in starved larvae carrying the endogenous GFP::mCherry::LGG-1 reporter, the proportion of autolysosomes decreased once the worms were refed (

Figure 5A-A’’). We observed that silencing the

let-363/TOR gene in the F2 generation led to a significant increase in the number of autolysosomes in both L1 and L2 larvae (

Figure 3D-D’’). A similar outcome was obtained in our experiment with the autophagosome–lysosome fusion inhibitor bafilomycin A1: in starved worms treated with bafilomycin A1 [

45,

46], the proportion of mCherry-positive structures was comparable to that of well-fed worms (

Figure 5B-B’’). Since changes in the number of autolysosomes are likely to directly correlate with autophagic activity [

28], our observations support the broad applicability of this strain for autophagy research. In our experiments with the second newly generated endogenous reporter strain, we found that GFP::ATG-5–positive foci in the intestine disappeared upon starvation (

Figure 7C, C’). However, because changes in autophagosome number alone do not unequivocally indicate whether autophagic activity is increasing or decreasing [

27,

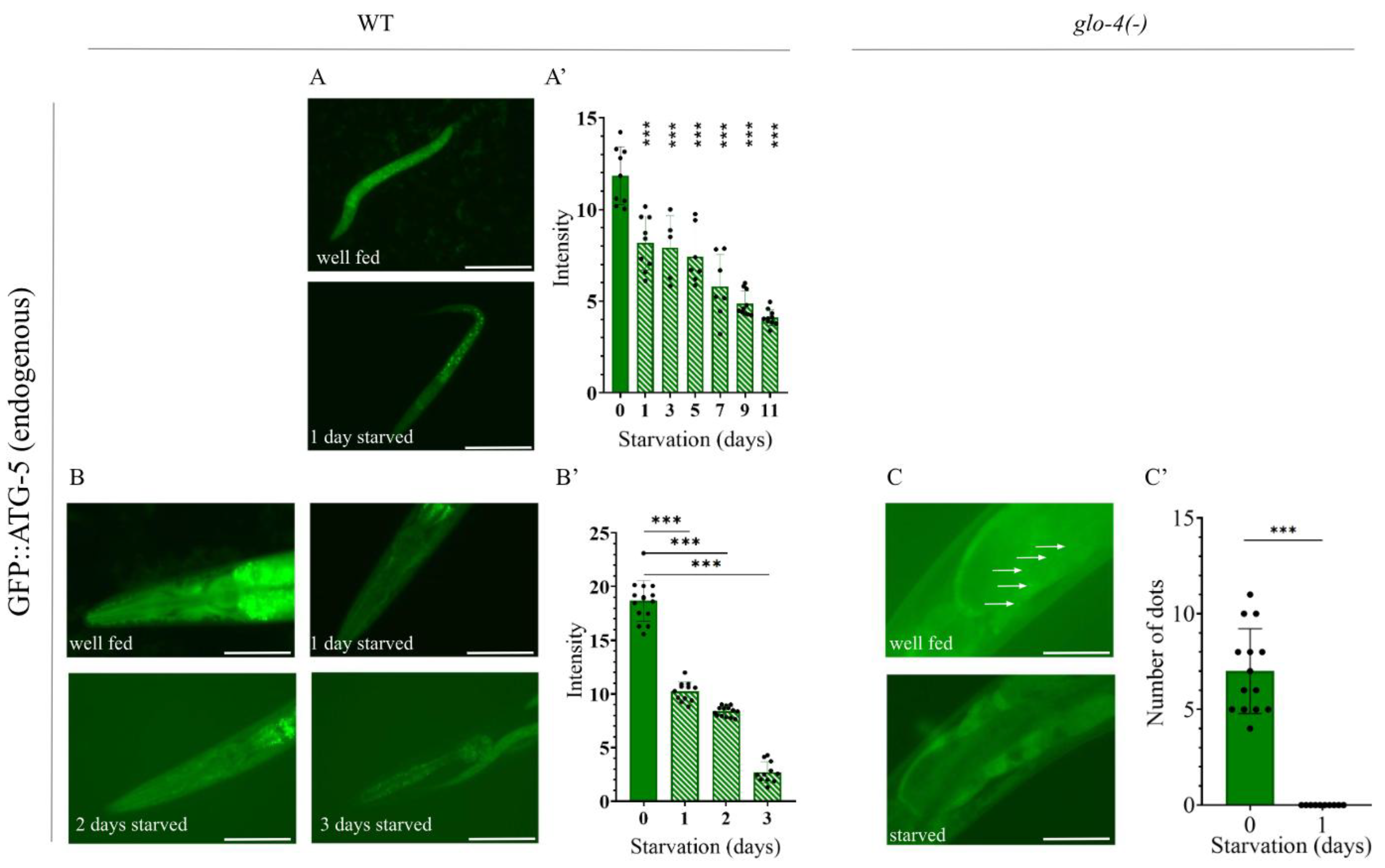

28], this information by itself is not sufficient to conclude that the disappearance of GFP-labeled autophagosomes represents increased autophagy. Taken together with our results using the endogenous GFP::mCherry::LGG-1 reporter, however, a clearer picture emerges: the disappearance of autophagosomes combined with the increase in autolysosomes strongly suggests that starvation induces an intensification of autophagic activity.

Taken together, while further experiments will be necessary in the future to unequivocally validate the applicability of the endogenous GFP::ATG-5 reporter construct, the endogenous GFP::mCherry::LGG-1 reporter construct has proven to be a suitable candidate for studying the process of autophagy and its activity changes in C. elegans.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Strains and Maintenance

C. elegans strains were maintained following standard protocols as described in WormBook (

www.wormbook.org), on nematode growth medium (NGM) plates seeded with

Escherichia coli OP50 at 20°C. In addition to the wild-type strain, the following reporter lines were generated, using CRISPR–Cas9 genome editing (provided by Suny Biotech): PHX2459

lgg-1(syb2459) [lgg-1p::gfp::mCherry::lgg-1] and

PHX2476 atg-5(syb2476) [atg-5p::gfp::atg-5] (Supplemetantary 3). To create genetic combinations, the following crosses were performed: TTV823

atg-5(syb2476) [atg-5p::gfp::atg-5]; glo-4(ok623) V – derived from crossing PHX2476 with RB811

glo-4(ok623) V. TTV801

lgg-1(syb2459) [lgg-1p::gfp::mCherry::lgg-1]; epg-5(tm3425) II – derived from crossing PHX2459 with FX3425

epg-5(tm3425) II. TTV923

lgg-1(syb2459) [lgg-1p::gfp::mCherry::lgg-1]; hlh-30(tm1978) IV – derived from crossing PHX2459 with JIN1375

hlh-30(tm1978) IV. For RNA interference (RNAi) experiments,

E. coli HT115 (DE3) as the RNAi feeding strain and

E. coli DH5α for plasmid propagation were used.

4.2. Western Blot Analysis

For protein isolation, 50–100 adult worms were collected in 20 µL of M9 buffer. Cell lysis was performed in the presence of Western blot loading buffer by three freeze-thaw cycles followed by sonication. Samples were then incubated at 95°C for 5 minutes. Lysates were stored at -80°C until further analysis by SDS-PAGE. Western blot analysis was performed using an SDS-containing gradient acrylamide gel, a nitrocellulose blotting membrane, and TBST (Tris-Buffered Saline with Tween 20) as washing solution. A 3% solution of milk powder in TBST served as the blocking reagent. Protein labeling was carried out for overnight at 4°C with the following primary antibodies: anti-GFP (anti-GFP rabbit, 1:2000, a gift from Gábor Juhász, Eötvös Loránd University, Budapest, Hungary), anti-mCherry (anti-mCherry rat, 1.1000, a gift from Gábor Juhász, Eötvös Loránd University, Budapest, Hungary), and anti-α-Tub84B (mouse, 1:2500, Sigma T6199). Secondary antibodies were applied at room temperature for one hour, which included: anti-rabbit IgG alkaline phosphatase (1:1000, Sigma, A3687), anti-mouse IgG alkaline phosphatase (1:1000, Sigma, A8438), and anti-rat IgG alkaline phosphatase (1:1000, Sigma, A8438). Primary and secondary antibodies were removed by three 10-minute washes in TBST. After washes, membranes were incubated in AP buffer. For signal visualization, NBT/BCIP (Sigma, 72091) was used, prepared in AP (alkaline phosphatase) buffer in 1:50 dilution.

4.3. Starvation Assay

For L1 larval starvation, the first step was to obtain a large number of gravid hermaphrodites. Animals were then washed off NGM plates with M9 buffer (recipe: WormBook, Maintenance of C. elegans; Protocol 6) and pelleted by centrifugation at 2000 rpm for 2 minutes. After removal of the supernatant, 5 ml of bleach solution (recipe: WormBook, Maintenance of C. elegans; Protocol 4) was added. Incubated for 8–10 minutes with occasional vortexing until the adult animals were completely dissolved, leaving behind their eggs. Immediately, 5 ml of M9 was added to stop the reaction. After repeating the centrifugation under the same conditions, the supernatant was removed, and the pellet was washed three times with 10 ml M9 buffer, using the same centrifugation settings. Following the final wash, the eggs were resuspended in 2 ml M9 buffer and incubated at 20°C for the duration of the experiment. For adult starvation, hermaphrodites at the L4 larval stage were transferred to NGM agar plates lacking OP50 bacterial lawns and containing 25 µg/ml fluorodeoxyuridine (FUDR) to prevent egg-laying and avoid mixing of generations. The animals were maintained at 20°C throughout the starvation period.

4.4. RNA Interference

RNA interference (RNAi) was performed using the feeding method, i.e., animals consumed bacteria containing double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) specific to the target gene intended for silencing [

59]. The T444T plasmid carrying the

let-363/TOR RNAi sequence [

60] was first transformed into

E. coli DH5α and subsequently into the HT115 strain to achieve more stable transformation. In the T444T plasmid, each end of the multicloning sites is flanked not only by T7 promoters but also by T7 terminator sequences, ensuring that only the intended sequence is transcribed, thereby increasing efficiency and specificity [

60]. As a control, HT115 bacteria carrying the empty construct were used. For

let-363 RNAi and control experiments, synchronized hermaphrodites were allowed to lay eggs on NGM plates seeded with the appropriate bacterial lawns. After 1.5–2 hours, egg-laying adults were removed. Once the F1 generation reached adulthood, they were again placed on fresh RNAi and control plates for egg-laying, and experiments were performed on the resulting F2 progeny.

4.5. Bafilomycin A1 Treatment

Starved L1 stage larvae were prepared as described above (starvation assay). Shortly, embryos were collected, and dissolved in 100 µl M9 solution. Finally, 0.93 µl Bafilomycin A1 (a specific inhibitor of vacuolar H+-ATPase which inhibits autolysosome formation) was added to achieve a final concentration of 30 nM. Embryos were let to developed into L1 larvae.

4.6. Fluorescent Microscopy

Fluorescent images were acquired using a Zeiss Axioimager Z1 upright microscope (equipped with Plan-NeoFluar 10×/0.3 NA, Plan-NeoFluar 40×/0.75 NA, and Plan-Apochromat 63×/1.4 NA objectives) with ApoTome, as well as a Nikon C2 confocal microscope (with a 60× Oil Plan APO VC NA = 1.45 objective). For data analysis and evaluation, AxioVision 4.82 and ImageJ 1.52c software were used.

4.7. Statistics

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 8.0.1. Significance between the experimental and control groups was determined using one-way ANOVA or t-test (Supplementary Tables 1).

Figure 1.

Function of GFP and mCherry labeling in autophagosomes and autolysosomes.A) GFP labels autophagosomes in green (punctate green fluorescent signal); however, due to the acidic pH of the lysosome, GFP is quenched in the autolysosome, and thus the GFP signal disappears (no green fluorescence is visible in this structure after fusion). B) The combined presence of green GFP and red fluorescent mCherry produces a yellow signal in autophagosomes (co-localization). Following fusion with the lysosome, GFP is quenched in the acidic lumen, leaving only the red mCherry fluorescence visible. In this way, our endogenous reporter distinguishes between different stages of autophagy.

Figure 1.

Function of GFP and mCherry labeling in autophagosomes and autolysosomes.A) GFP labels autophagosomes in green (punctate green fluorescent signal); however, due to the acidic pH of the lysosome, GFP is quenched in the autolysosome, and thus the GFP signal disappears (no green fluorescence is visible in this structure after fusion). B) The combined presence of green GFP and red fluorescent mCherry produces a yellow signal in autophagosomes (co-localization). Following fusion with the lysosome, GFP is quenched in the acidic lumen, leaving only the red mCherry fluorescence visible. In this way, our endogenous reporter distinguishes between different stages of autophagy.

Figure 2.

The endogenously tagged GFP::mCherry::LGG-1 reporter is expressed from early embryonic stages throughout adulthood. A) The gfp::mcherry::linker coding sequence was inserted after the START (ATG) codon of the endogen lgg-1 gene. B) Fluorescent stage of the tandem GFP::mCherry::LGG-1 reporter. On merged images of animals expressing GFP::mCherry::LGG-1, autophagosome (AP) are marked by yellow and autolysosomes (AL) are marked by red dots. The scale bars represent 200 μm. Fluorescent signals: GFP (green), mCherry (red). B’) Representative picture of endogenously tagged GFP::mCherry in adult hermafrodites and head with the pharynx (dashed line). Orange arrowhead AL, yellow arrowhead AP, white arrowhead GFP only dots. The scale bars represent 50 μm. Fluorescent signals: GFP (green), mCherry (red). B’’) Quantification of the percentage of the autophagy structures-covered area in the 1-day old adult head. Data is presented as mean and SD of three independent measurements with min. 10 animals in each. Each black dot represents a measured individual. For statistics, see Suppl. Tables. 1. C-C’) Representative picture of endogenously tagged GFP::mCherry at different embryonic stages with ApoTome (C) and DIC (C’) imaging. The scale bars represent 50 μm. Fluorescent signals: GFP (green), mCherry (red). Orange arrowhead AL, yellow arrowhead AP, white arrowhead GFP only dots, black arrowhead marks apoptotic corps. D-D’) Representative picture of endogenously tagged GFP::mCherry in adult gonad with ApoTome (D) and DIC (D’) imaging. Distal tip cells (DTC) marked by a yellow arrow. Orange arrowhead AL, black arrowhead points to apoptotic corps. The scale bars represent 50 μm. Fluorescent signals: GFP (green), mCherry (red).

Figure 2.

The endogenously tagged GFP::mCherry::LGG-1 reporter is expressed from early embryonic stages throughout adulthood. A) The gfp::mcherry::linker coding sequence was inserted after the START (ATG) codon of the endogen lgg-1 gene. B) Fluorescent stage of the tandem GFP::mCherry::LGG-1 reporter. On merged images of animals expressing GFP::mCherry::LGG-1, autophagosome (AP) are marked by yellow and autolysosomes (AL) are marked by red dots. The scale bars represent 200 μm. Fluorescent signals: GFP (green), mCherry (red). B’) Representative picture of endogenously tagged GFP::mCherry in adult hermafrodites and head with the pharynx (dashed line). Orange arrowhead AL, yellow arrowhead AP, white arrowhead GFP only dots. The scale bars represent 50 μm. Fluorescent signals: GFP (green), mCherry (red). B’’) Quantification of the percentage of the autophagy structures-covered area in the 1-day old adult head. Data is presented as mean and SD of three independent measurements with min. 10 animals in each. Each black dot represents a measured individual. For statistics, see Suppl. Tables. 1. C-C’) Representative picture of endogenously tagged GFP::mCherry at different embryonic stages with ApoTome (C) and DIC (C’) imaging. The scale bars represent 50 μm. Fluorescent signals: GFP (green), mCherry (red). Orange arrowhead AL, yellow arrowhead AP, white arrowhead GFP only dots, black arrowhead marks apoptotic corps. D-D’) Representative picture of endogenously tagged GFP::mCherry in adult gonad with ApoTome (D) and DIC (D’) imaging. Distal tip cells (DTC) marked by a yellow arrow. Orange arrowhead AL, black arrowhead points to apoptotic corps. The scale bars represent 50 μm. Fluorescent signals: GFP (green), mCherry (red).

Figure 3.

Expression of the endogenously tagged GFP::mCherry::LGG-1 reporter is highly responsive to genetic alterations that change autophagic activity. A-C) Representative pictures of endogenously tagged GFP::mCherry::LGG-1 expression in adult hermafrodites (left) and in the head (right) (the pharynx is outlined by a dashed line) in wild-type (A), epg-5(-) (B), and hlh-30(-) (C) mutant animals. The scale bars represent 200 μm in the whole-body image and 50 μm in the pharyngeal image. Fluorescent signals: GFP (green), mCherry (red). D, D’) Representative picture of endogenously tagged GFP::mCherry::LGG-1 expression in an L1 larva treated with control (D) and let-363 RNAi (D’), pharynx marked by a dashed line The scale bars represent 50 µm. Fluorescent signals: GFP (green), mCherry (red). B’’-D’’) Quantification of the autophagy pool size in the pharynx of the 1-day old adult hermafrodites in epg-5(-) (B’’) and hlh-30(-) (C’’) mutants vs. wild-type animals, and in the pharynx of the control and let-363 RNAi-treated L1 animals (D’’). GFP represents the area of AP pool only, mCherry represents the total pool of autophagy structures (AP+AL). Data are the mean ± SD of > X animals combinated from tree independent experiments. Statistical significance was determined using non-paired t-test, n.s. p>0.05, * p<0.01, ** p<0.001, *** p<0.0001, **** p<0.00001. For statistics, see Suppl. Tables 1.

Figure 3.

Expression of the endogenously tagged GFP::mCherry::LGG-1 reporter is highly responsive to genetic alterations that change autophagic activity. A-C) Representative pictures of endogenously tagged GFP::mCherry::LGG-1 expression in adult hermafrodites (left) and in the head (right) (the pharynx is outlined by a dashed line) in wild-type (A), epg-5(-) (B), and hlh-30(-) (C) mutant animals. The scale bars represent 200 μm in the whole-body image and 50 μm in the pharyngeal image. Fluorescent signals: GFP (green), mCherry (red). D, D’) Representative picture of endogenously tagged GFP::mCherry::LGG-1 expression in an L1 larva treated with control (D) and let-363 RNAi (D’), pharynx marked by a dashed line The scale bars represent 50 µm. Fluorescent signals: GFP (green), mCherry (red). B’’-D’’) Quantification of the autophagy pool size in the pharynx of the 1-day old adult hermafrodites in epg-5(-) (B’’) and hlh-30(-) (C’’) mutants vs. wild-type animals, and in the pharynx of the control and let-363 RNAi-treated L1 animals (D’’). GFP represents the area of AP pool only, mCherry represents the total pool of autophagy structures (AP+AL). Data are the mean ± SD of > X animals combinated from tree independent experiments. Statistical significance was determined using non-paired t-test, n.s. p>0.05, * p<0.01, ** p<0.001, *** p<0.0001, **** p<0.00001. For statistics, see Suppl. Tables 1.

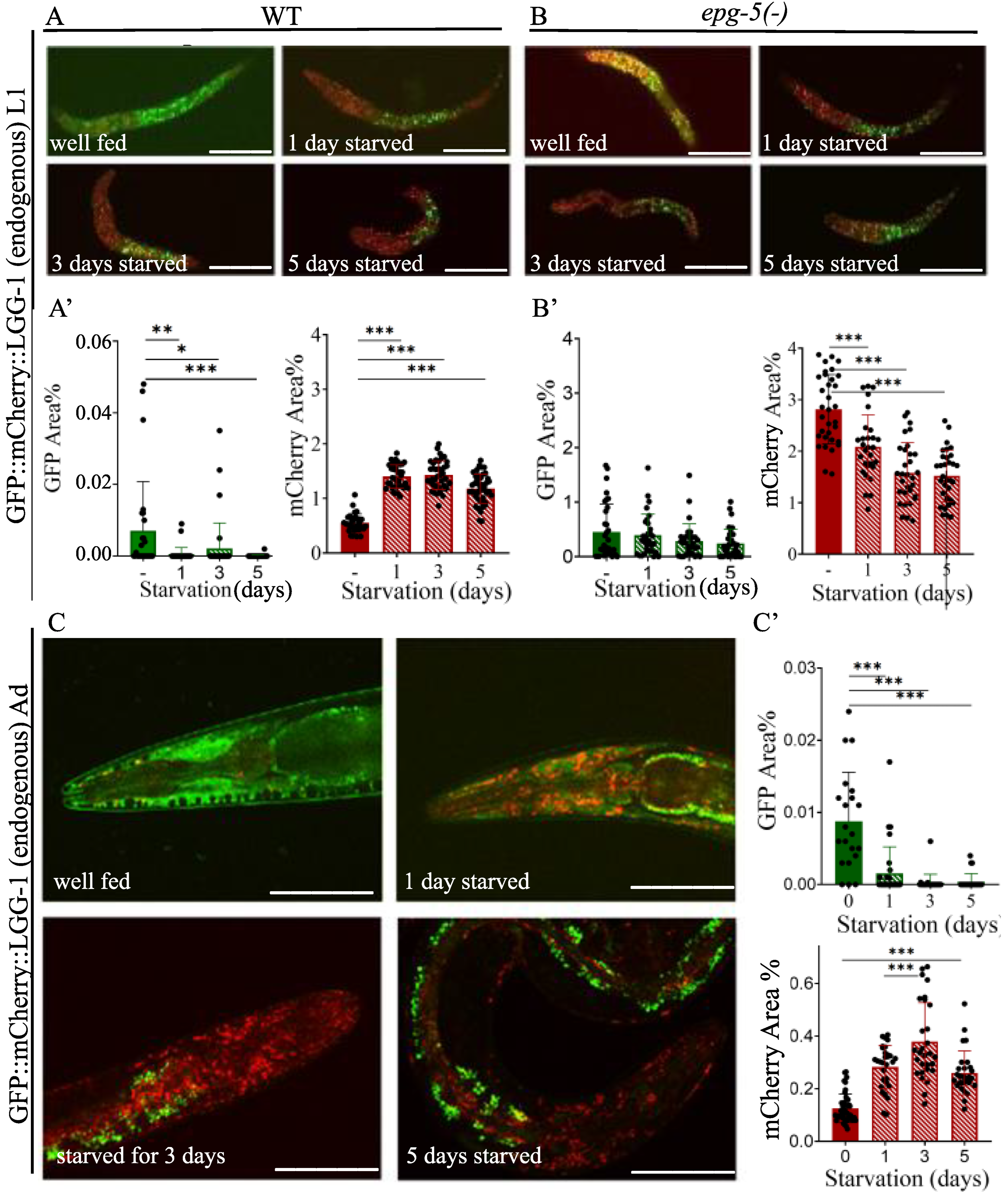

Figure 4.

The quantity of mCherry-labeled autophagy structures increases in response to starvation at the L1 larval stage and young adulthood in an otherwise wild-type genetic background, but decreases in autophagy defective epg-5(-) mutant genetic background. A-B) Representative images of GFP::mCherry::LGG-1 transgene expression in wild type (A) and epg-5(tm3425) mutant (B) L1 larvae showing the relative abundance of GFP- and mCherry-labeled structures. The scale bars represent 50 μm. Fluorescent signals: GFP (green), mCherry (red). A', B1) Quantification of the percentage coverage of GFP- and mCherry-labeled structures in the head region of GFP::mCherry::LGG-1 transgene expression in wild type (A’) and epg-5(tm3425) mutant (B’) L1 larvae. GFP represents the autophagosome (AP) pool only, while mCherry represents the total autophagic structures (AP+AL). Each black dot represents a measured individual. Statistical significance was determined using an unpaired t-test, n.s. p>0.05, *p<0.01, **p<0.001, ***p<0.0001, ****p<0.00001. C) Representative images of GFP- and mCherry-labeled structures in young adult animals expressing GFP::mCherry::LGG-1 under fed and starved conditions. The head region of the animals is shown. The scale bars represent 50 μm. Fluorescent signals: GFP (green), mCherry (red). C’) Quantification of the percentage coverage of GFP- and mCherry-labeled structures in the head region of GFP::mCherry::LGG-1 young adults. GFP represents the AP pool only, while mCherry represents the total pool of autophagic structures (AP+AL). Each black dot represents a measured individual. Statistical significance was determined using an unpaired t-test, n.s. p>0.05, **p<0.001, ***p<0.0001, ****p<0.00001. For statistics, see Suppl. Tables 1.

Figure 4.

The quantity of mCherry-labeled autophagy structures increases in response to starvation at the L1 larval stage and young adulthood in an otherwise wild-type genetic background, but decreases in autophagy defective epg-5(-) mutant genetic background. A-B) Representative images of GFP::mCherry::LGG-1 transgene expression in wild type (A) and epg-5(tm3425) mutant (B) L1 larvae showing the relative abundance of GFP- and mCherry-labeled structures. The scale bars represent 50 μm. Fluorescent signals: GFP (green), mCherry (red). A', B1) Quantification of the percentage coverage of GFP- and mCherry-labeled structures in the head region of GFP::mCherry::LGG-1 transgene expression in wild type (A’) and epg-5(tm3425) mutant (B’) L1 larvae. GFP represents the autophagosome (AP) pool only, while mCherry represents the total autophagic structures (AP+AL). Each black dot represents a measured individual. Statistical significance was determined using an unpaired t-test, n.s. p>0.05, *p<0.01, **p<0.001, ***p<0.0001, ****p<0.00001. C) Representative images of GFP- and mCherry-labeled structures in young adult animals expressing GFP::mCherry::LGG-1 under fed and starved conditions. The head region of the animals is shown. The scale bars represent 50 μm. Fluorescent signals: GFP (green), mCherry (red). C’) Quantification of the percentage coverage of GFP- and mCherry-labeled structures in the head region of GFP::mCherry::LGG-1 young adults. GFP represents the AP pool only, while mCherry represents the total pool of autophagic structures (AP+AL). Each black dot represents a measured individual. Statistical significance was determined using an unpaired t-test, n.s. p>0.05, **p<0.001, ***p<0.0001, ****p<0.00001. For statistics, see Suppl. Tables 1.

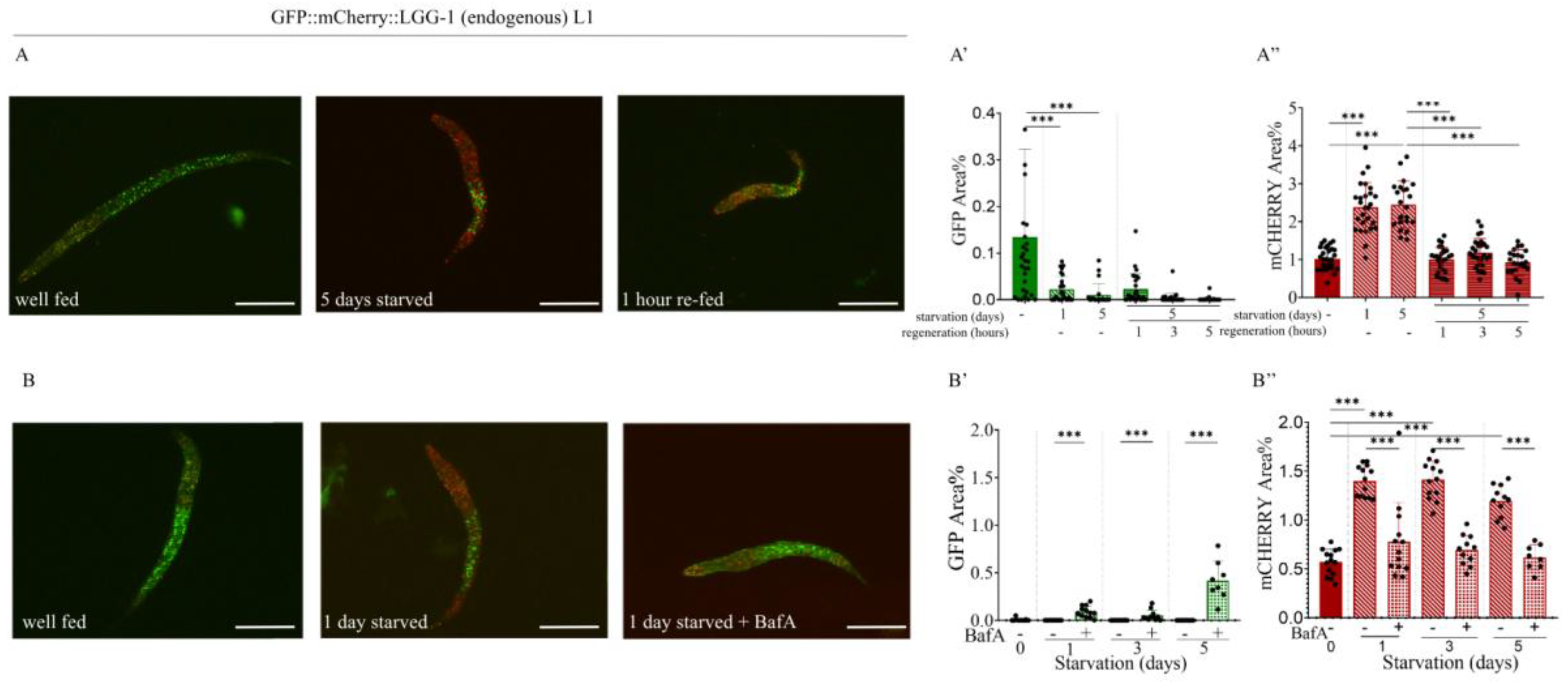

Figure 5.

In response to bafilomycin A1 treatment, the quantity of mCherry-labeled autophagy structures in starved L1 larvae decreases to levels that are similar to those found in well-fed animals. A) Representative images of GFP::mCherry::LGG-1 L1 larvae showing GFP- and mCherry-labeled structures under fed conditions, after 5 days of starvation, and after refeeding following 5 days of starvation. The scale bars represent 50 μm. Fluorescent signals: GFP (green), mCherry (red). B) Representative images of GFP::mCherry::LGG-1 L1 larvae showing GFP- and mCherry-labeled structures under fed conditions, after 1 day of starvation, and after 1 day of starvation with bafilomycin A1 treatment. The scale bars represent 50 μm. Fluorescent signals: GFP (green), mCherry (red). A’,A”,B’,B”) Quantification of the percentage area coverage of GFP- (A’, B’) and mCherry-labeled (A’’, B’’) structures in the head region of GFP::mCherry::LGG-1 L1 larvae is shown (graphs, right panels). GFP represents the autophagosome (AP) pool only, while mCherry represents the total pool of autophagic structures (AP+AL). Each black dot represents a measured individual. Statistical significance was determined using an unpaired t-test, n.s. p>0.05, **p<0.001, ***p<0.0001, ****p<0.00001. For statistics, see Suppl. Tables 1.

Figure 5.

In response to bafilomycin A1 treatment, the quantity of mCherry-labeled autophagy structures in starved L1 larvae decreases to levels that are similar to those found in well-fed animals. A) Representative images of GFP::mCherry::LGG-1 L1 larvae showing GFP- and mCherry-labeled structures under fed conditions, after 5 days of starvation, and after refeeding following 5 days of starvation. The scale bars represent 50 μm. Fluorescent signals: GFP (green), mCherry (red). B) Representative images of GFP::mCherry::LGG-1 L1 larvae showing GFP- and mCherry-labeled structures under fed conditions, after 1 day of starvation, and after 1 day of starvation with bafilomycin A1 treatment. The scale bars represent 50 μm. Fluorescent signals: GFP (green), mCherry (red). A’,A”,B’,B”) Quantification of the percentage area coverage of GFP- (A’, B’) and mCherry-labeled (A’’, B’’) structures in the head region of GFP::mCherry::LGG-1 L1 larvae is shown (graphs, right panels). GFP represents the autophagosome (AP) pool only, while mCherry represents the total pool of autophagic structures (AP+AL). Each black dot represents a measured individual. Statistical significance was determined using an unpaired t-test, n.s. p>0.05, **p<0.001, ***p<0.0001, ****p<0.00001. For statistics, see Suppl. Tables 1.

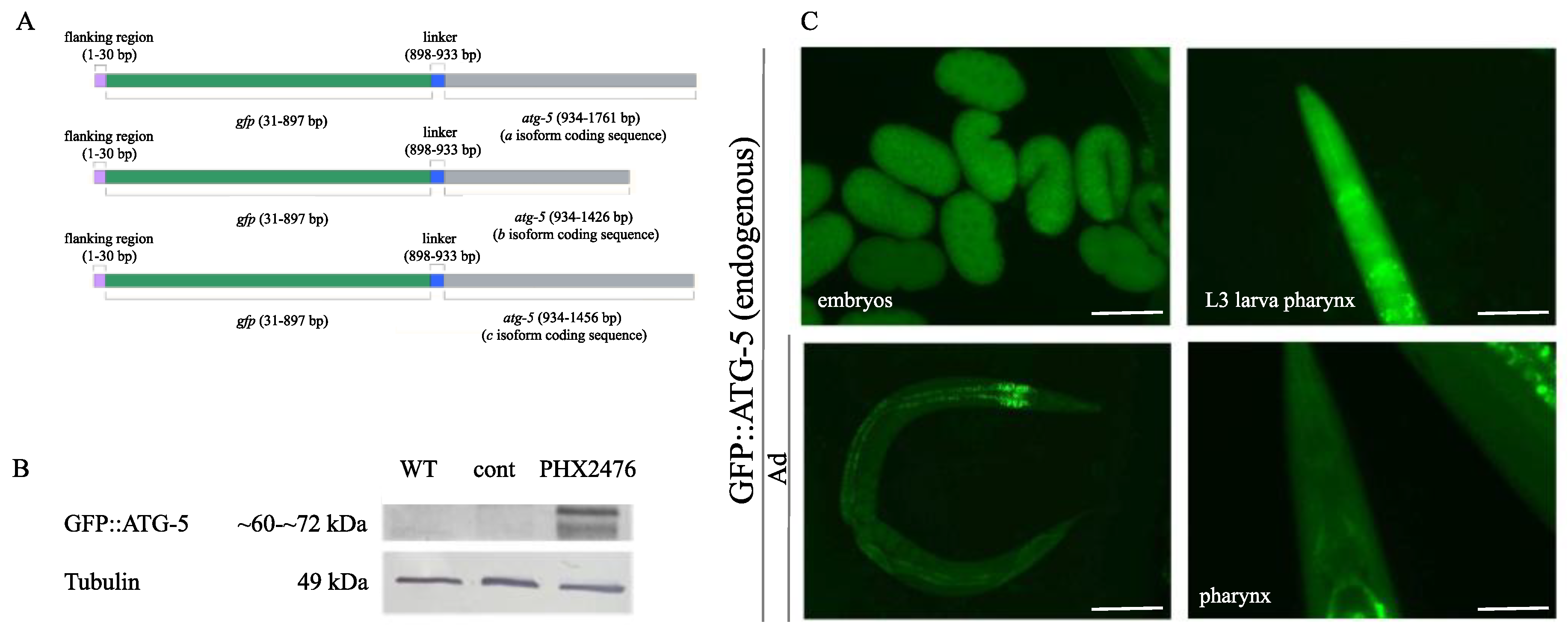

Figure 6.

Expression analysis of the endogenous GFP::ATG-5 reporter. A) Schematic of the GFP::ATG-5 reporter construct. The GFP sequence is positioned upstream of the atg-5 coding sequence in all three isoforms. B) Western blot analysis detecting the GFP::ATG-5 protein. The protein was detected in PHX2476 animals but not in wild-type animals or in those expressing another endogenous GFP gene used as a control. Tubulin was used as a loading control. WT: wild type; EV: empty vector; cont (control): endogenous GFP-expressing strain; kDa: kilo-Dalton. C) GFP::ATG-5 reporter accumulation at different embryonic stages (top left), in the pharynx of an L3 stage larva (top right), in a young hermaphrodite (bottom left), and in the pharynx of an adult hermaphrodite (bottom right). Exposure time: 200 ms. The scale bars represent 50 μm in the embryo image and in the pharyngeal images, and 20 μm in the whole-body image. Fluorescent signal: GFP (green).

Figure 6.

Expression analysis of the endogenous GFP::ATG-5 reporter. A) Schematic of the GFP::ATG-5 reporter construct. The GFP sequence is positioned upstream of the atg-5 coding sequence in all three isoforms. B) Western blot analysis detecting the GFP::ATG-5 protein. The protein was detected in PHX2476 animals but not in wild-type animals or in those expressing another endogenous GFP gene used as a control. Tubulin was used as a loading control. WT: wild type; EV: empty vector; cont (control): endogenous GFP-expressing strain; kDa: kilo-Dalton. C) GFP::ATG-5 reporter accumulation at different embryonic stages (top left), in the pharynx of an L3 stage larva (top right), in a young hermaphrodite (bottom left), and in the pharynx of an adult hermaphrodite (bottom right). Exposure time: 200 ms. The scale bars represent 50 μm in the embryo image and in the pharyngeal images, and 20 μm in the whole-body image. Fluorescent signal: GFP (green).

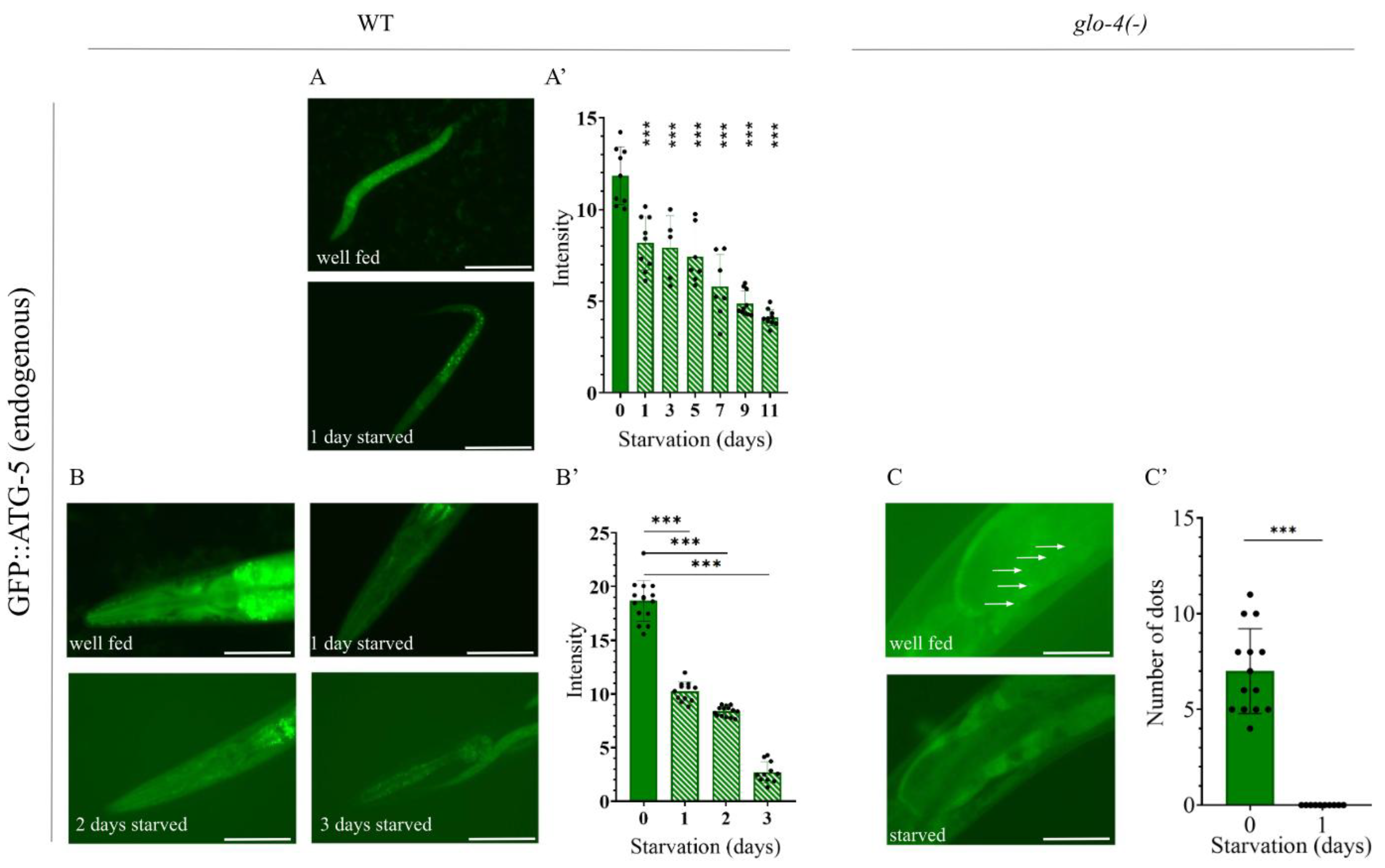

Figure 7.

The endogenous GFP::ATG-5 reporter is responsive to starvation induced stress. A) Representative images of GFP::ATG-5 L1 larvae under fed and 1-day starved conditions. Exposure time: 800 ms. The scale bars represent 50 μm. Fluorescent signal: GFP (green). A’) Quantification of GFP expression intensity in the head region of GFP::ATG-5 L1 larvae. GFP represents the autophagosome (AP) pool. Each black dot represents a measured individual. Statistical significance was determined using an unpaired t-test, n.s. p>0.05, **p<0.001, ***p<0.0001, ****p<0.00001. B) Representative images of young adult animals expressing the endogenous GFP::ATG-5 reporter under fed conditions and after 1, 2, and 3 days of starvation. Images show the head region of the animals Exposure time: 800 ms. The scale bars represent 50 μm. Fluorescent signal: GFP (green). B’) Quantification of GFP expression intensity in the head region of GFP::ATG-5 young adults. GFP represents the AP pool. Each black dot represents a measured individual. Statistical significance was determined using an unpaired t-test, n.s. p>0.05, **p<0.001, ***p<0.0001, ****p<0.00001. C) Representative images of the anterior intestine of young adult GFP::ATG-5 animals under fed and starved conditions. Arrows indicate GFP-positive autophagic structures in the first intestinal cell of fed animals. Exposure time: 1500 ms. The scale bars represent 10 μm. Fluorescent signal: GFP (green). C’) Quantification of GFP-labeled structures in the anterior intestine of GFP::ATG-5 young adults in the glo-4(-) mutant genetic background. Each black dot represents a measured individual. Statistical significance was determined using an unpaired t-test, n.s. p>0.05, **p<0.001, ***p<0.0001, ****p<0.00001. For statistics, see Suppl. Tables 1.

Figure 7.

The endogenous GFP::ATG-5 reporter is responsive to starvation induced stress. A) Representative images of GFP::ATG-5 L1 larvae under fed and 1-day starved conditions. Exposure time: 800 ms. The scale bars represent 50 μm. Fluorescent signal: GFP (green). A’) Quantification of GFP expression intensity in the head region of GFP::ATG-5 L1 larvae. GFP represents the autophagosome (AP) pool. Each black dot represents a measured individual. Statistical significance was determined using an unpaired t-test, n.s. p>0.05, **p<0.001, ***p<0.0001, ****p<0.00001. B) Representative images of young adult animals expressing the endogenous GFP::ATG-5 reporter under fed conditions and after 1, 2, and 3 days of starvation. Images show the head region of the animals Exposure time: 800 ms. The scale bars represent 50 μm. Fluorescent signal: GFP (green). B’) Quantification of GFP expression intensity in the head region of GFP::ATG-5 young adults. GFP represents the AP pool. Each black dot represents a measured individual. Statistical significance was determined using an unpaired t-test, n.s. p>0.05, **p<0.001, ***p<0.0001, ****p<0.00001. C) Representative images of the anterior intestine of young adult GFP::ATG-5 animals under fed and starved conditions. Arrows indicate GFP-positive autophagic structures in the first intestinal cell of fed animals. Exposure time: 1500 ms. The scale bars represent 10 μm. Fluorescent signal: GFP (green). C’) Quantification of GFP-labeled structures in the anterior intestine of GFP::ATG-5 young adults in the glo-4(-) mutant genetic background. Each black dot represents a measured individual. Statistical significance was determined using an unpaired t-test, n.s. p>0.05, **p<0.001, ***p<0.0001, ****p<0.00001. For statistics, see Suppl. Tables 1.