Submitted:

09 October 2025

Posted:

10 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- The proposed sandwich structure, consisting of a carbon fiber fabric/epoxy resin skin and a 3D-printed PAHT-CF core, prepared using the hand lay-up technique, has not yet been experimentally benchmarked in the literature, to the best of the authors’ knowledge.

- A series of different tests have been carried out, including tensile, three-point bending, impact, hardness, density and water absorption tests, providing a comprehensive view of the most important properties, often required in a variety of engineering applications.

- Although the effect of the cubic infill pattern on the properties of FDM 3D-printed samples has been investigated in literature, it has not been studied for PAHT-CF material, to the authors' knowledge. In this work three infill patterns have been examined in terms of their mechanical strength.

- The outcomes of this work highlight the suitability of the proposed sandwich composites as lightweight, high-strength and water-resistant structures for relevant applications.

2. Literature Overview

2.1. Sandwich Composites with Additively Manufactured Core

2.2. Effect of Infill Pattern on the Strength of 3D-Printed Carbon Fiber-Reinforced Polymers

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

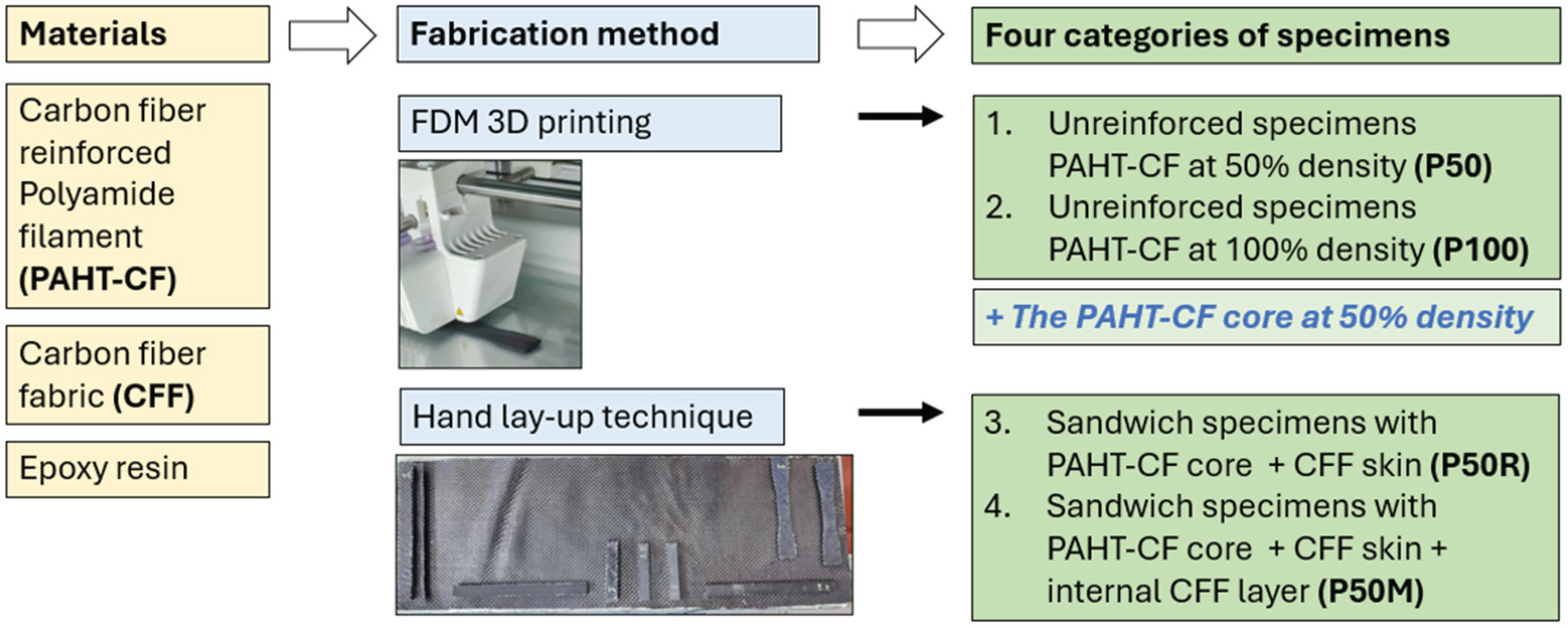

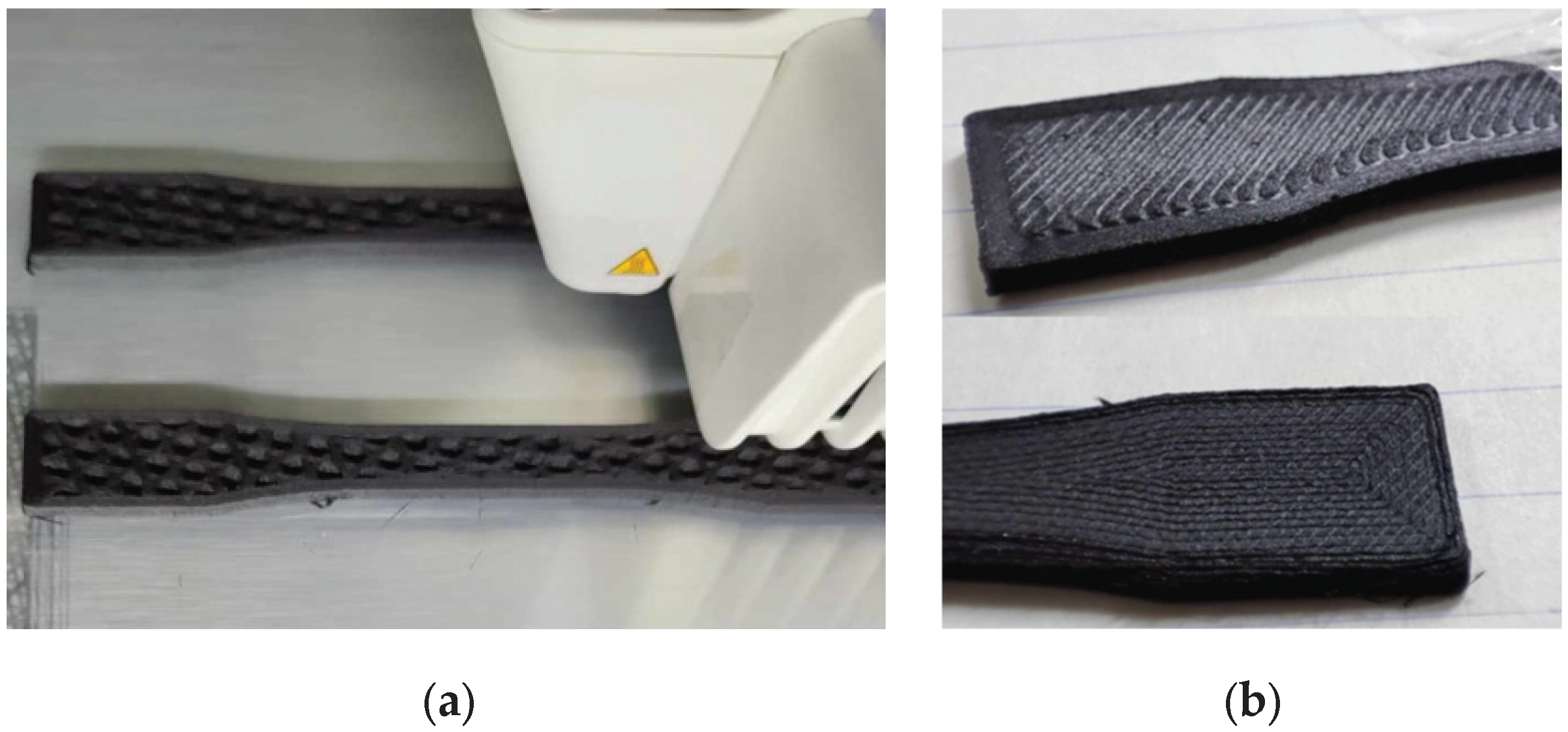

3.2. Fabrication Process

3.2.2. Hand Lay-Up Technique for the Sandwich Specimens

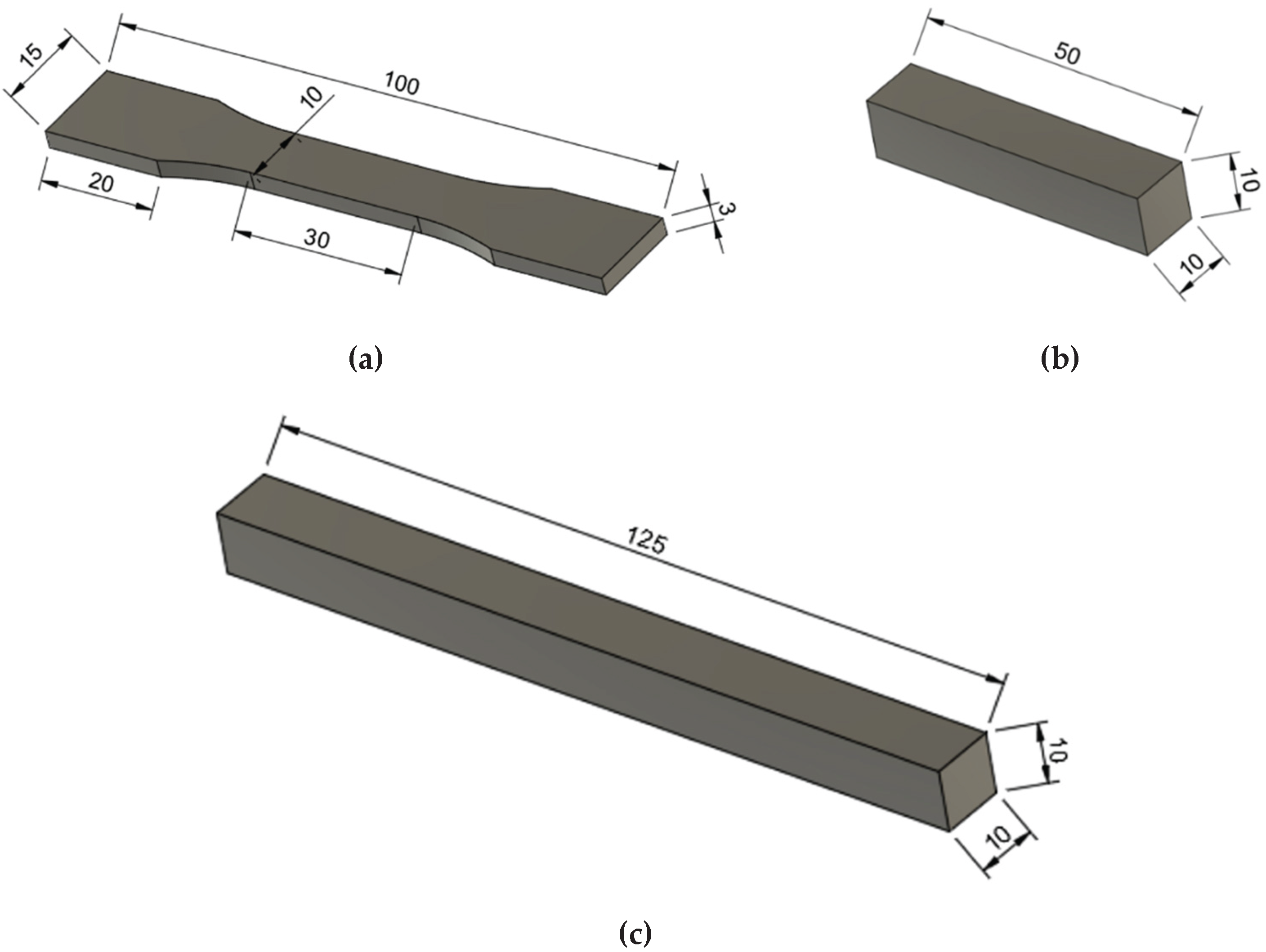

3.3. Testing Methods

4. Results and Discussion

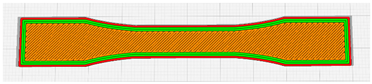

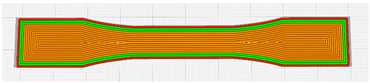

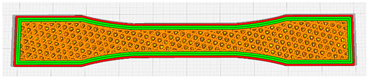

4.1. Preliminary Evaluation of Infill Patterns for 3D-Printed PAHT-CF Specimens

4.1.1. Mechanical Properties

4.1.2. Dimensional Accuracy and Surface Quality

4.1.3. Infill Pattern Considerations

4.2. Experimental Investigation of the Performance of the Fabricated Specimens

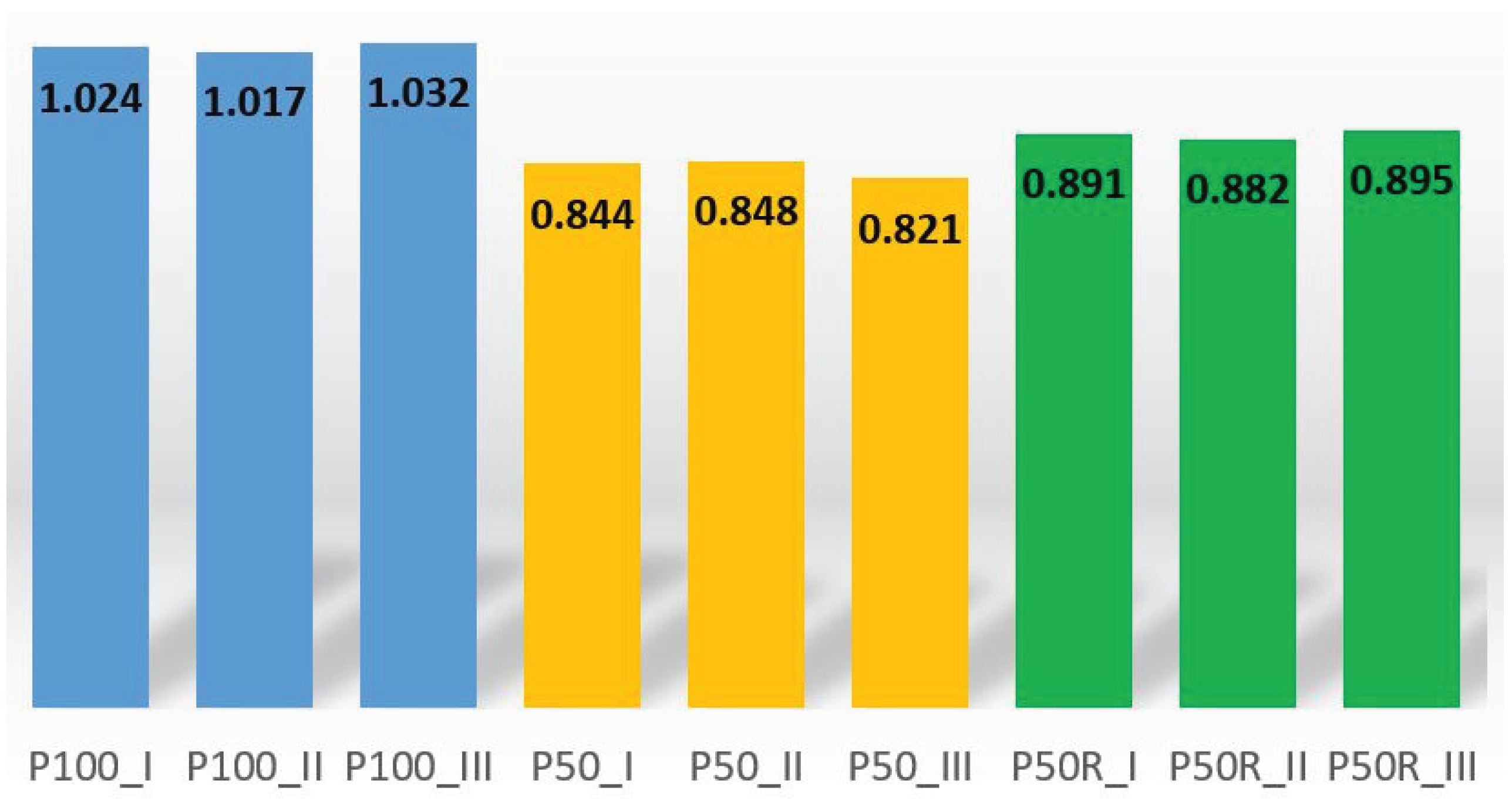

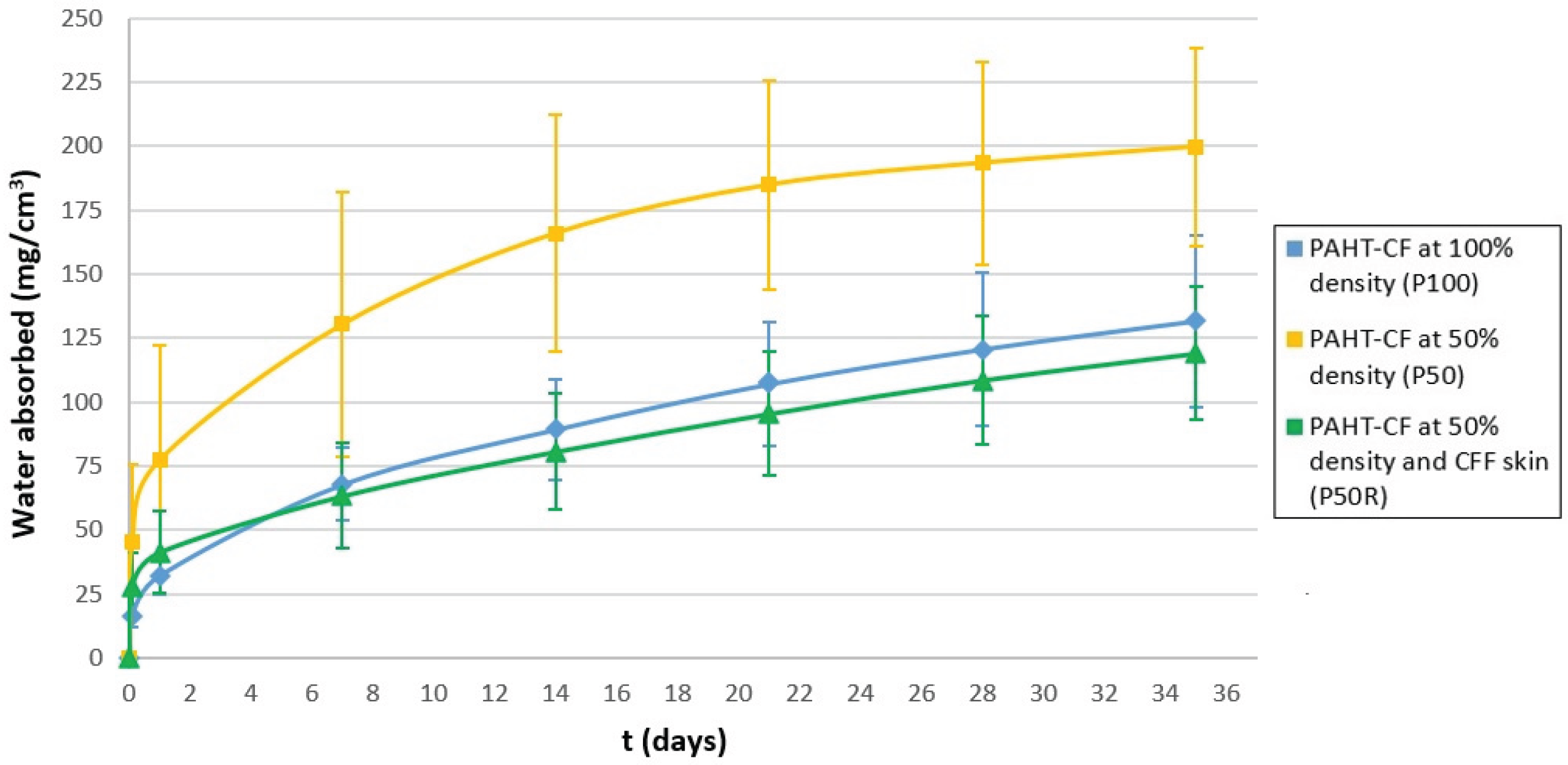

4.2.1. Density and Water Absorption Measurements

4.2.2. Hardness Measurements

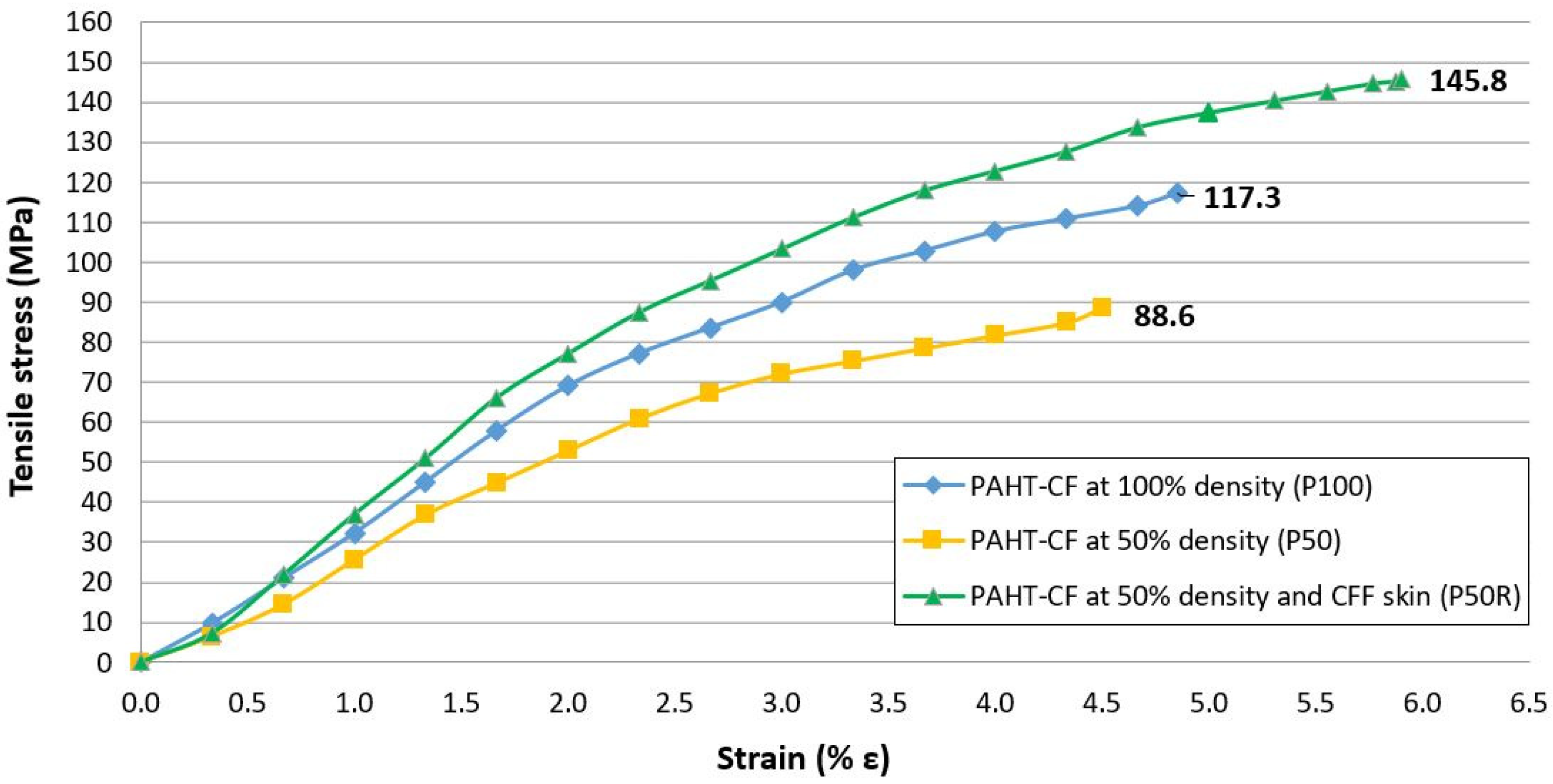

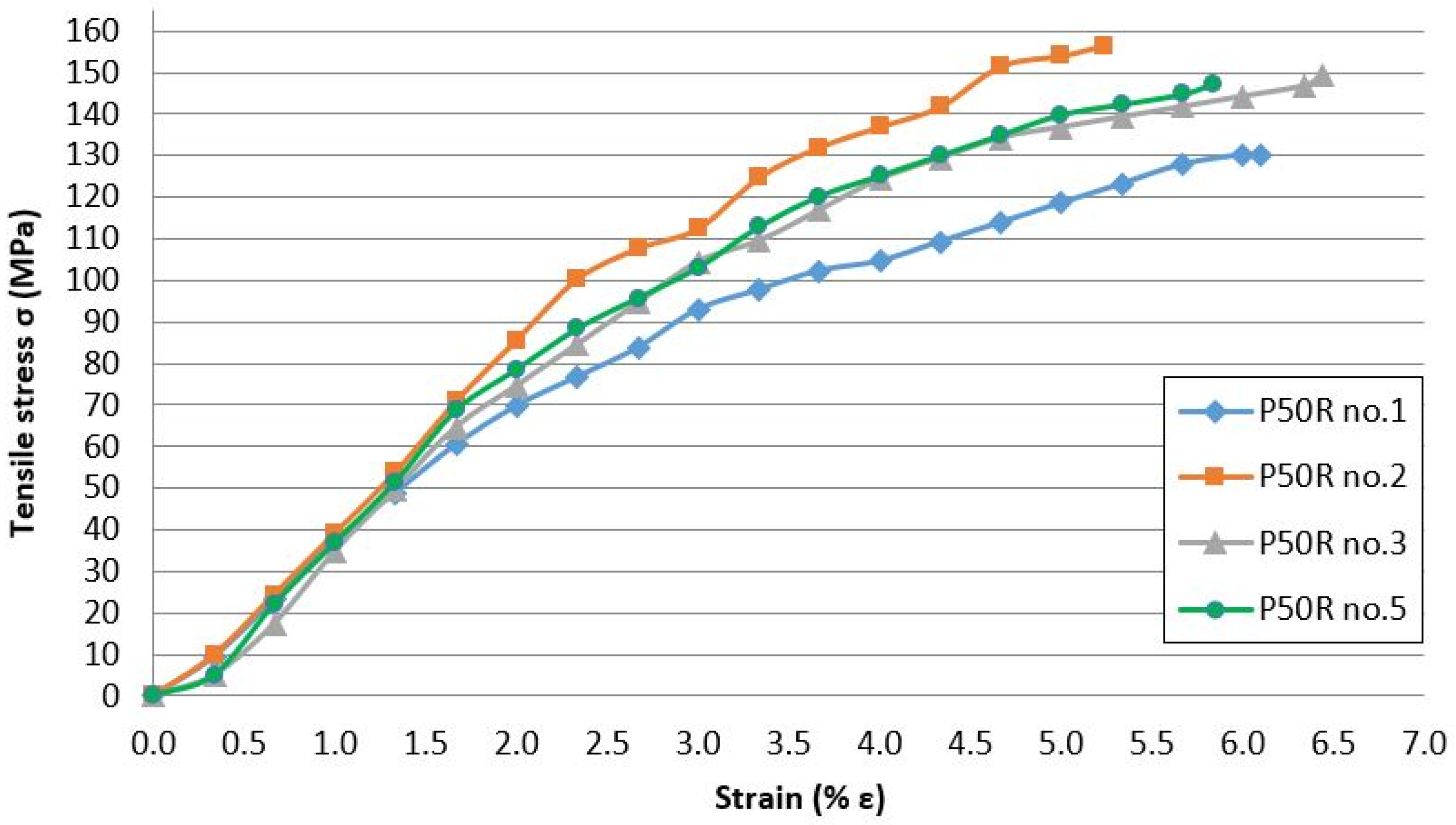

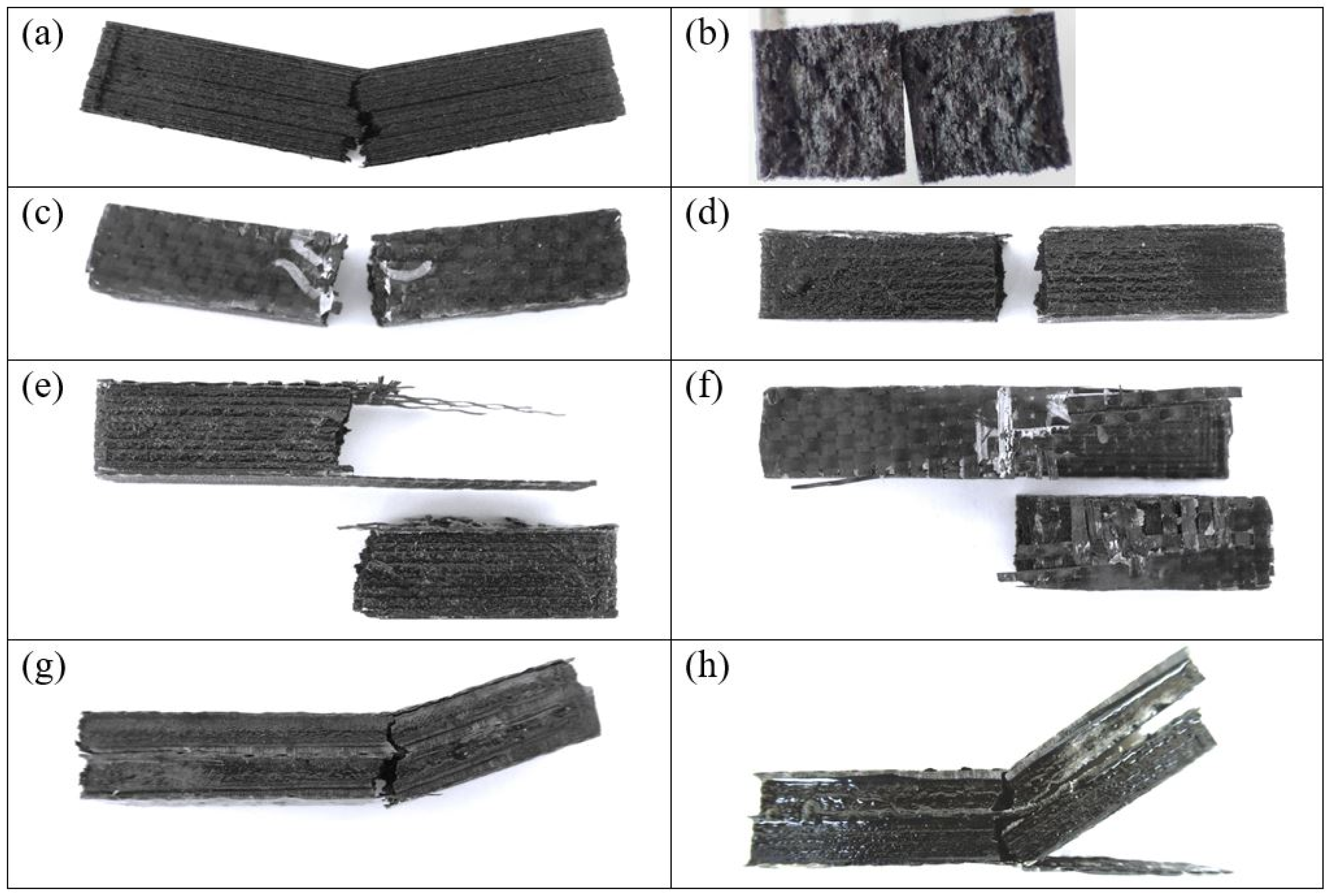

4.2.3. Tensile Strength

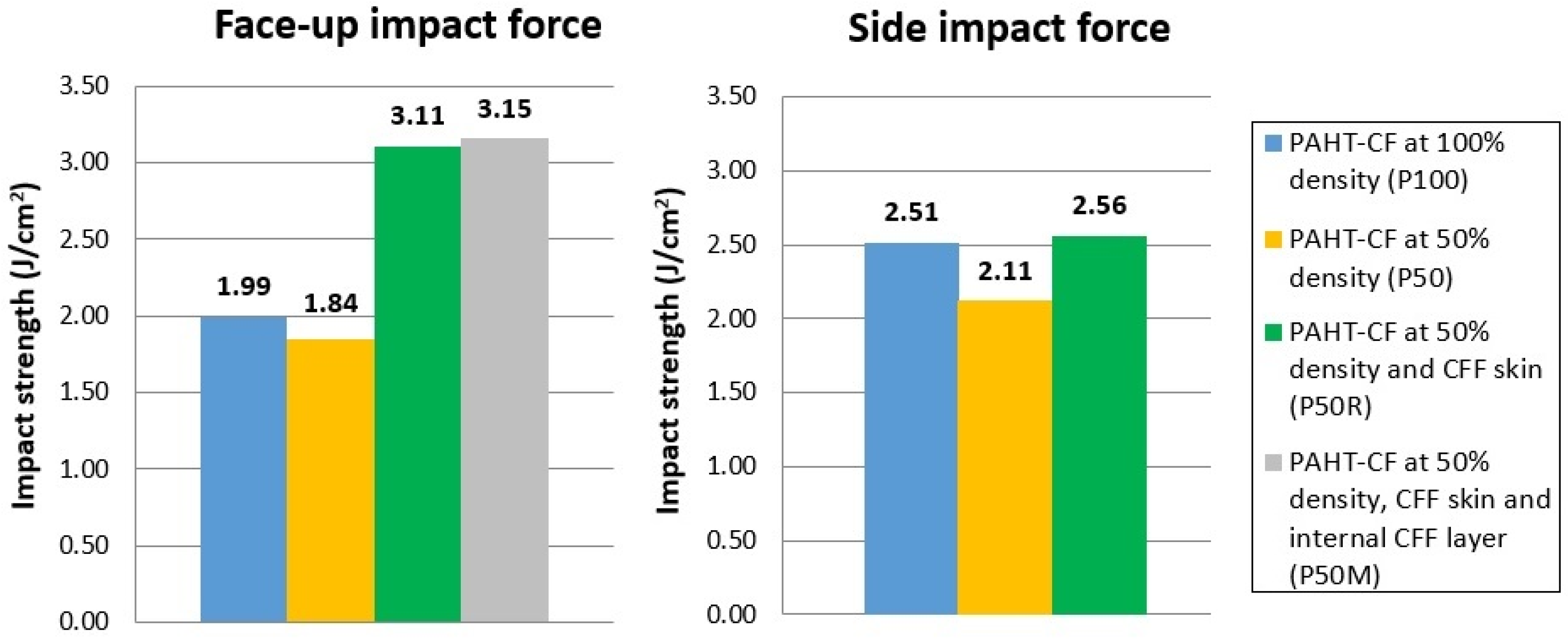

4.2.4. Impact Strength

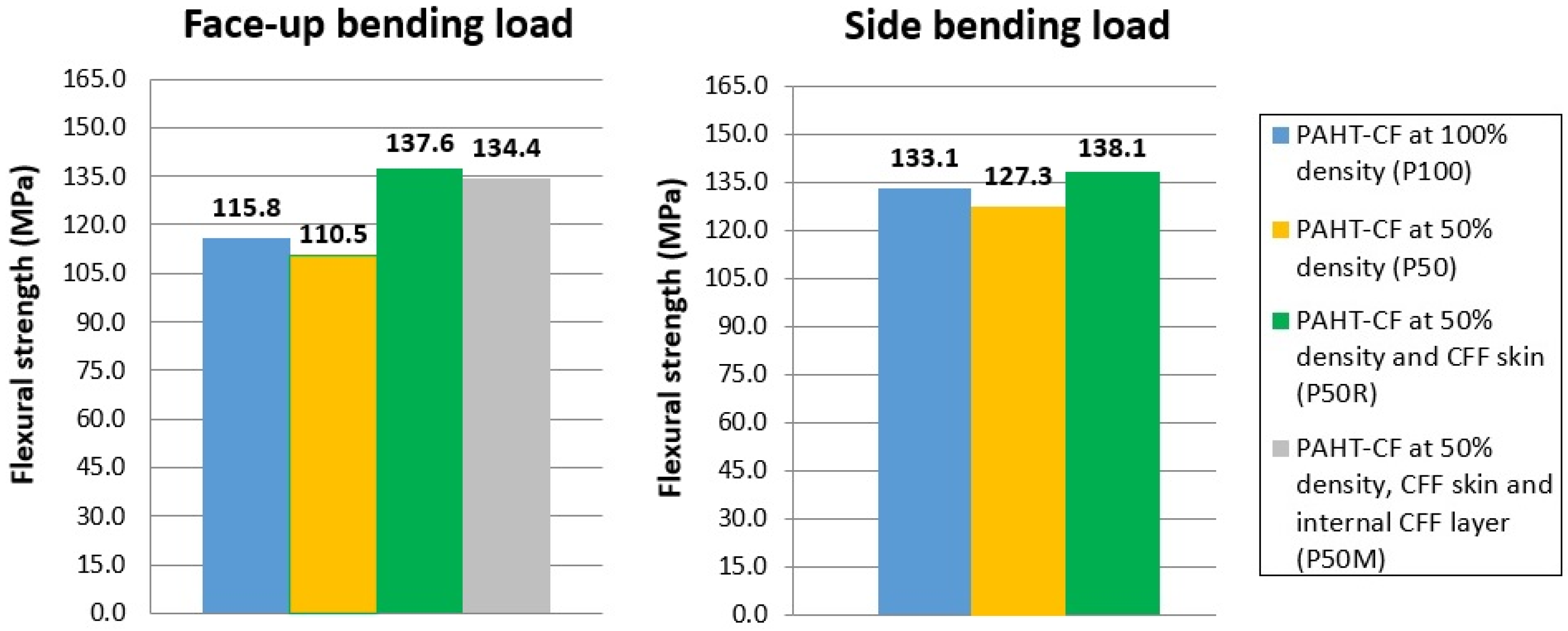

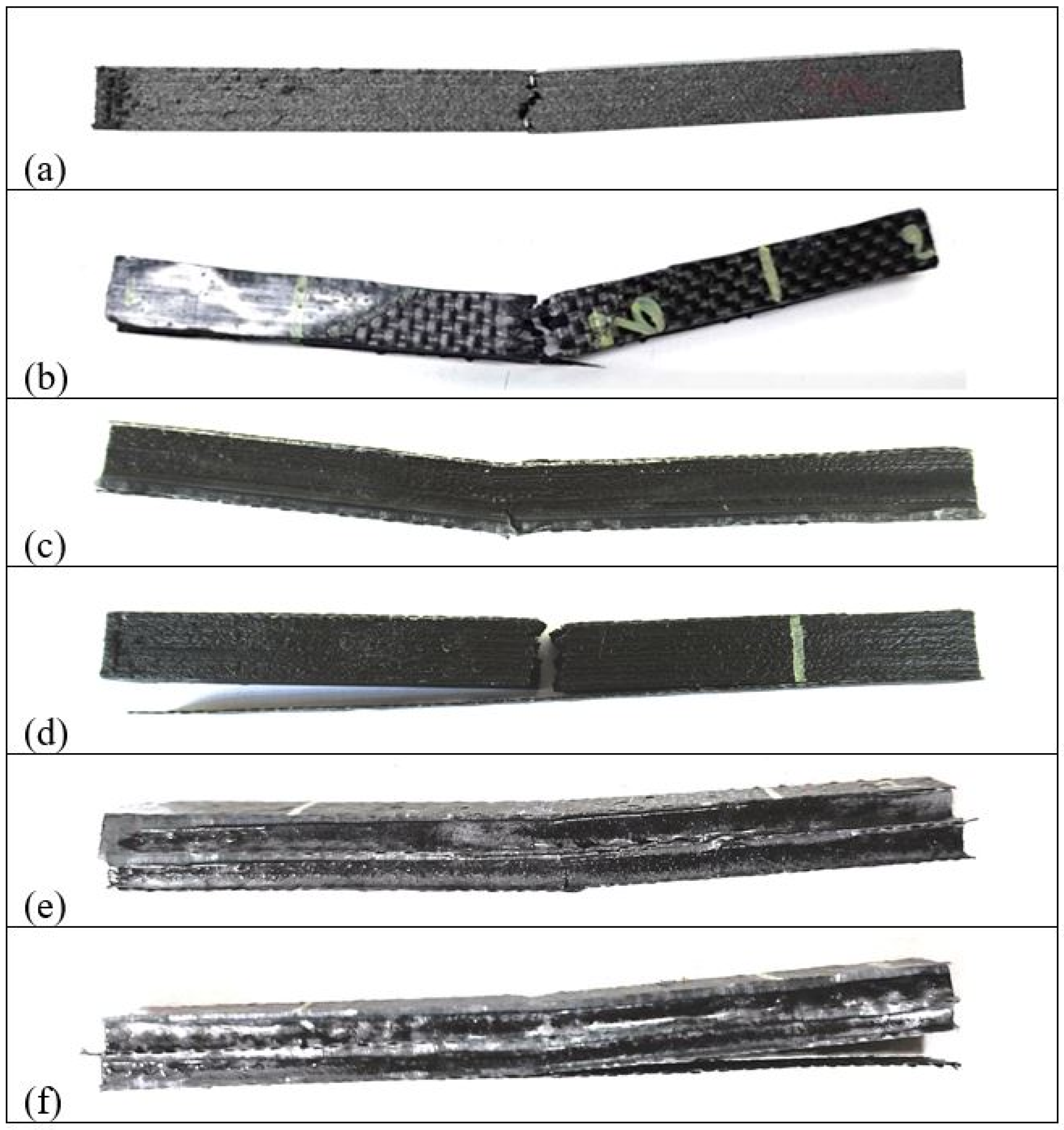

4.2.5. Flexural Strength

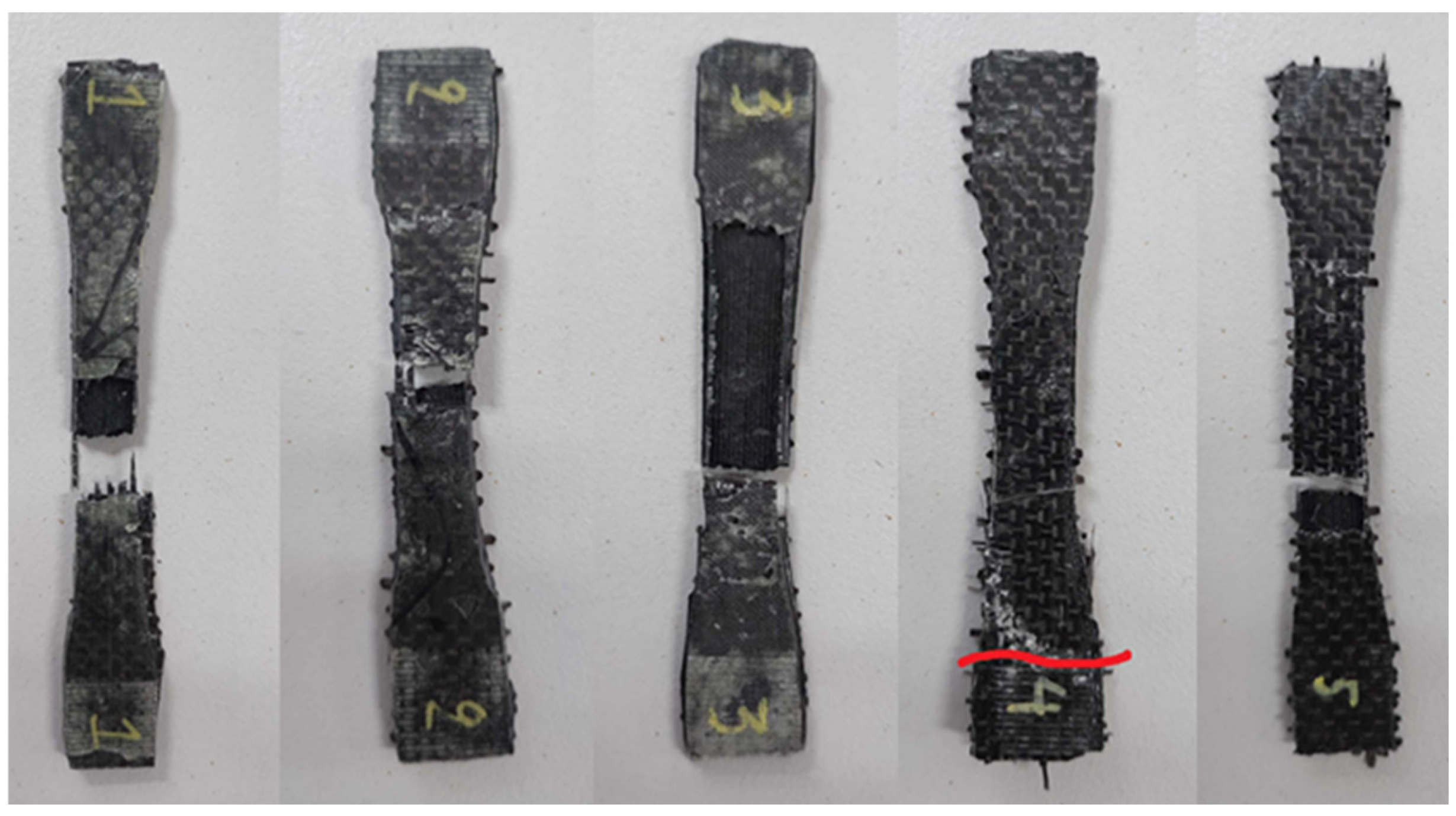

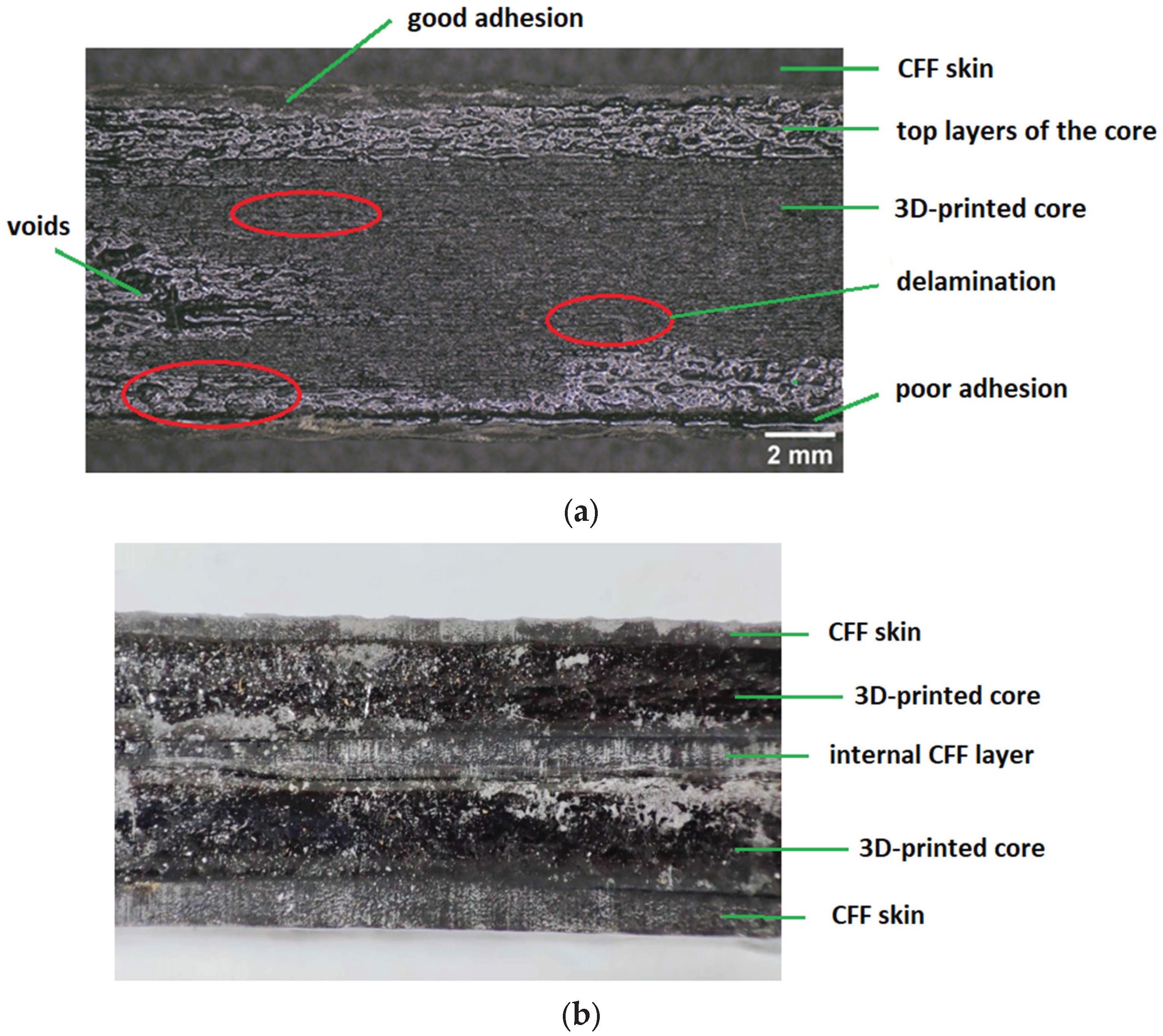

4.2.6. Consideration of Quality-Related Issues

5. Conclusions

- The results obtained in the preliminary study in Section 4.1. suggest that the infill pattern has a significant effect on the tensile and impact strength of 3D-printed parts. Among the three examined infill patterns, i.e., lines, concentric and cubic, the concentric pattern should be preferred for structures where tensile strength is a critical parameter, such as arms or beams, while the cubic pattern is more suitable for structures subjected to non-uniform loading.

- PAHT-CF material is easy to print, provided that sufficient print tests have been carried out to ensure the interaction between printing parameters and final properties. Temperature and humidity conditions affect the results, so a closed chamber that maintains temperature during printing and a dry filament to minimize porosity would be desirable.

- Possible solutions regarding the CFF skin detachment include applying epoxy adhesive to the core/skin interface, modifying the epoxy/hardener ratio or the curing time of the epoxy resin, treating the surfaces prior to joining, or using one additional layer of glass or aramid fibers between the skin and the core.

- The proposed fabrication process, which combines 3D printing of the core and hand lay-up technique, is relatively slower than other manufacturing methods for sandwich structures, such as compression molding or advanced 3D printing that integrates the fabrication core and face sheets, so it is more suitable for small-scale or customized products.

- For larger sandwich structures, the limited build volume of FDM 3D printers can be overcome by dividing large-dimensional core structures into many smaller parts. Then, the hand lay-up technique can be used to gradually attach the carbon fiber fabric and join all parts together with epoxy adhesive.

- Future research could include (a) the investigation of the effect of different 3D-printed core structures on the mechanical strength of the sandwich composites, (b) the fabrication of sandwich composites with 3D-printed core and CFF skin using pressure vacuum bagging aiming at reducing geometric deviations and improving the skin/core adhesion, and (c) the attachment of one additional woven roving (fiberglass) layer between the CFF skin and the 3D-printed core to prevent skin detachment.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rubino, F.; Nisticò, A.; Tucci, F.; Carlone, P. Marine Application of Fiber Reinforced Composites: A Review. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2020, 8, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, P.K.; Jagadesh, T. Applications and Challenges of 3D Printed Polymer Composites in the Emerging Domain of Automotive and Aerospace: A Converged Review. J. Inst. Eng. India Series D 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamzat, A.K; Murad, M.S.; Adediran, I.A.; et al. Fiber-reinforced composites for aerospace, energy, and marine applications: an insight into failure mechanisms under chemical, thermal, oxidative, and mechanical load conditions. Adv Compos Hybrid Mater 2025, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.; Yang, J.; Chen, J.; Guan, S. Review of carbon fiber-reinforced sandwich structures. Polymers and Polymer Composites 2022, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Hao, Q.; Yicong, G.; Hao, Z.; Jianrong, T. Creative design for sandwich structures: A review. Int. J. adv. Robot. Syst. 2020, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; & Fang, J.; Wu, C.; Li, C.; Sun, G.; Li, Q. Additively manufactured materials and structures: A state-of-the-art review on their mechanical characteristics and energy absorption. International Journal of Mechanical Sciences 2023, 108102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forés-Garriga, Albert.; Gómez-Gras, G.; Pérez, M.A. Lightweight hybrid composite sandwich structures with additively manufactured cellular cores. Thin-Walled Structures 2023, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boado-Cuartero, B.; Pérez-Álvarez, J.; Roibás-Millán, E. Material Characterization of High-Performance Polymers for Additive Manufacturing (AM) in Aerospace Mechanical Design. Aerospace 2024, 11, 748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Leon, A.C.C.; da Silva, I.G.M.; Pangilinan, K.D.; Chen, Q.; Caldona, E.B.; Advincula, R.C. High performance polymers for oil and gas applications. Reactive and Functional Polymers 2021, 162, 104878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krajangsawasdi, N.; Blok, L.G.; Hamerton, I.; Longana, L.; Woods, B.K.S.; Ivanov, D.S. Fused Deposition Modelling of FibreReinforced Polymer Composites: A Parametric Review. J. Compos. Sci. 2021, 5, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuan-Urquizo, E.; Guerra, S.R. Fused Filament Fabrication of cellular, lattice and porous mechanical metamaterials: a review. Virtual and Physical Prototyping 2023, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Jianzhong, F.; Yao, X. Triply periodic minimal surface (TPMS) porous structures: From multi-scale design, precise additive manufacturing to multidisciplinary applications. Int. J. Extreme Manuf. 2022, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UltiMaker Cura Infill settings. Available online: https://support.ultimaker.com/s/article/1667411002588 (accessed on 17 July 2025).

- Wickstrom, S. Mastering 3D Printing Infill Patterns: From Gyroid to Lightning. Available online: https://ultimaker.com/learn/mastering-3d-printing-infill-patterns-from-gyroid-to-lightning/ (accessed on 17 July 2025).

- Ma, Q.; Rejab, M.R.M.; Song, Y.; et al. Effect of infill pattern of polylactide acid (PLA) 3D-printed integral sandwich panels under ballistic impact loading. Materials Today Communications 2024, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, S.; Singh, A.; Murtaza, Q. Measuring the Impact of Infill Pattern and Infill Density on the Properties of 3D-Printed PLA via FDM. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preetish, S.; Harish, S. Effect of Infill Pattern on Flexural Behaviour and Surface Roughness Behaviour of 3D Printed Poly Lactic Acid (PLA) Material. International Journal for Research in Applied Science and Engineering Technology 2024, 12, 1152–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhoundi, B.; Behravesh, A.H. Effect of Filling Pattern on the Tensile and Flexural Mechanical Properties of FDM 3D Printed Products. Exp Mech 2019, 59, 883–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, P.K.; Senthil, P.; Adarsh, S.; Anoop, M.S. An investigation to study the combined effect of different infill pattern and infill density on the impact strength of 3D printed polylactic acid parts. Composites Communications 2021, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Reyna, S.L.; Mata, C.; Díaz-Aguilera, J.H.; Acevedo-Parra, H.R.; Tapia, F. Mechanical properties optimization for PLA, ABS and Nylon + CF manufactured by 3D FDM printing. Materials Today Communications 2022, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haldar, A.; Managuli, V.; Rahul, M.; Agarwal, R.; Guan, Z. Compressive Behavior of 3D Printed Sandwich Structures Based on Corrugated Core Design. Materials Today Communications 2020, 26, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamalbabu, P.; Bhanumurthy, R.; Viswanathan, R.; et al. Additive Manufacturing of Honeycomb Core Sandwich Panels: An Evaluation of Flexural Performance. Journal of Physics: Conference Series 2024, 2925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scattareggia Marchese, S.; Epasto, G.; Crupi, V.; Garbatov, Y. Feasibility study on additive-manufactured honeycomb sandwich structural solutions for a Fast Patrol Vessel. Composite Structures 2025, 351, 118607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, R.G.; Pavez, G.M. Flexural characteristics of additively manufactured continuous fiber-reinforced honeycomb sandwich structures. Composites Part C: Open Access 2025, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshaer, A.; Harland, D. An investigation of the strength and stiffness of weight-saving sandwich beams with CFRP face sheets and seven 3D printed cores. Composite Structures 2021, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridlwan, M.; Syafi’i, N.M.; Nurgesang, F.A.; Riza, R. 3D Printed Polymer Core and Carbon Fiber Skin Sandwich Composite: An Alternative Material and Process for Electric Vehicles Customization, In Proceedings of 7th International Conference on Electric Vehicular Technology (ICEVT), Bali, Indonesia, 2022, pp. 34-37, 10.1109/ICEVT55516.2022.9924696. [Google Scholar]

- Zoumaki, M.; Mansour, M.T.; Tsongas, K.; Tzetzis, D.; Mansour, G. Mechanical Characterization and Finite Element Analysis of Hierarchical Sandwich Structures with PLA 3D-Printed Core and Composite Maize Starch Biodegradable Skins. J. Compos. Sci. 2022, 6, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acanfora, V.; Sellitto, A.; Russo, A.; Zarrelli, M.; Riccio, A. Experimental investigation on 3D printed lightweight sandwich structures for energy absorption aerospace applications. Aerospace Science and Technology 2023, 137, 108276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nur Ainin, F.; Azaman, M.D.; Abdul Majid, M.S.; Ridzuan, M.J.M. Investigating the low-velocity impact behaviour of sandwich composite structures with 3D-printed hexagonal honeycomb core—A review. Funct. Compos. Struct. 2023, 5, 012001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forés-Garriga, A.; Gómez-Gras, G.A.; Pérez, M.A. Lightweight hybrid composite sandwich structures with additively manufactured cellular cores. Thin-Walled Structures 2023, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junaedi, H.; Abd El-baky, M.A.; Awd Allah, M.M.; Sebaey, T.A. Mechanical Characteristics of Sandwich Structures with 3D-Printed Bio-Inspired Gyroid Structure Core and Carbon Fiber-Reinforced Polymer Laminate Face-Sheet. Polymers 2024, 16, 1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francisco, M.B.; Gomes, R.A.; Pereira, J.L.J.; da Cunha, S.S.; Gomes, G.F. High-performance design of auxetic sandwich structures: A multi-objective optimization approach. Mech. Adv. Mater. Struct. 2024, 32(6), 1225–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.; Lee, J.; Altaf, K.; et al. Quasi-static indentation characteristics of foam-filled sandwich composite structures with additively manufactured CFRP and GFRP corrugated cores. J. Sandw. Struct. Mater. 2024, 27, 505–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stepinac, L.; Galić, J. Preliminary investigation of the large-scale sandwich decks with graded 3D printed auxetic core. J. Sandw. Struct. Mater. 2024, 27, 260–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, M. Low-velocity impact behavior assessment of 3D printed sandwiched structure with varying infill patterns, M.Sc. Thesis, National University of Sciences & Technology (NUST), Pakistan, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Azeem, M.; Nasir, M.A. Tensile behavior of sandwich structures using various 3D printed core shapes with polymer matrix composites. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Tech. 2025, 137, 5665–5682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brejcha, V.; Böhm, M.; Holeček, T.; Jerman, M.; Kobetičová, K.; Burianová, I.; Černý, R.; Pavlík, Z. Comparison of Bending Properties of Sandwich Structures Using Conventional and 3D-Printed Core with Flax Fiber Reinforcement. J. Compos. Sci. 2025, 9, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalaimagal, S.; Vasumathi, M.; Rashia Begum, S.; et al. Evaluation of impact resistance of sustainable sandwich structures with optimized FDM core geometries using low-velocity drop impact tests. Polym Compos. 2025, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzaei, J.; Nouri, N.M.; Nikouei, S. Mechanical characteristics of 3D -printed honeycomb sandwich structures: Effect of skin material and core orientation. Polym Compos 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muralidharan, B.; Kanmani Subbu, S.; Ajikumar, A.K.; et al. Experimental and numerical study of three-point bending test in five different FDM 3D printed PLA core with carbon fiber sandwich structures. Engineering Research Express 2025, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, I.J.; Sevvel, P.; Gunasekaran, J. A review on the various processing parameters in FDM, Materials Today: Proceedings 2021, 37:509–514. [CrossRef]

- Gonabadi, H.; Hosseini, S.F.; Chen, Y.; et al. Size effects of voids on the mechanical properties of 3D printed parts. Int J Adv Manuf Technol, 5439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syrlybayev, D.; Zharylkassyn, B.; Seisekulova, A.; Akhmetov, M.; Perveen, A.; Talamona, D. Optimisation of Strength Properties of FDM Printed Parts—A Critical Review. Polymers 2021, 13, 1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naranjo-Lozada, J.; Ahuett-Garza, H.; Pedro Orta-Castañón, P.; et al. Tensile properties and failure behavior of chopped and continuous carbon fiber composites produced by additive manufacturing, Additive Manufacturing 2019, 26:227-241, 10.1016/j.addma.2018.12.020.

- Rao, V.D.P.; Rajiv, P.; Geethika, V. Effect of fused deposition modelling (FDM) process parameters on tensile strength of carbon fibre PLA. Materials Today: Proceedings 2019, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q.; Rejab, R.; Kumar, A.P.; Fu, H.; et al. Effect of infill pattern, density and material type of 3D printed cubic structure under quasi-static loading. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part C: J. Mech. Eng. Sci. 2020, 1:1-19. 10.1177/0954406220971667.

- Ansari, A.A.; Kamil, M. Izod impact and hardness properties of 3D printed lightweight CF-reinforced PLA composites using design of experiment, Int. J. Lightweight Mater. Manuf. 2022, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pop, M.A.; Zaharia, S. ; Chicos, L-A.; Lancea, C. et al. Effect of the infill patterns on the mechanical properties of the carbon fiber 3D printed parts. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering 2022, 1235(1), 10.1088/1757-899X/1235/1/012006. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, B.; Mubarak, S.; Zhang, G.; Peng, K.; Hu, X.; Zhang, Q.; Wu, L.; Wang, J. Fused-Deposition Modeling 3D Printing of Short-Cut Carbon-Fiber-Reinforced PA6 Composites for Strengthening, Toughening, and Light Weighting. Polymers 2023, 15, 3722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abali, B.E.; Afshar, R.; Khaksar, N.; Segersten, D.; Vedin, T. Damage Behavior in Additive Manufacturing based on Infill Pattern and Density with Carbon Particle Filled PolyLactic Acid (CF-PLA) Polymer Filaments. In State of the Art and Future Trends in Materials Modelling 2. Advanced Structured Materials; Altenbach, H., Öchsner, A. Eds.; Springer, 2024; Volume 200, pp 1–16.

- Andreozzi, M.; Bianchi, I.; Archimede, F.; et al. Effect of infill percentage and pattern on compressive behavior of FDM-printed GF-CF PA6 composites. Conference Material Forming (ESAFORM), Materials Research Proceedings 2024, pp. 283-289, 10.21741/9781644903131-32.

- Hozdić, E.; Hozdić, E. Influence of Infill Structure Shape and Density on the Mechanical Properties of FDM 3D-Printed PETG and PETG+CF Materials. Advanced Technologies & Materials 2024, 49, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ultrafuse® PAHT CF15 TDS. Available online: https://forward-am.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/ Ultrafuse_PAHT_CF15_TDS_EN_v3.5-1.pdf (accessed on 17/07/2025).

- Dimitrellou, S.; Iakovidis, I.; Psarianos, D.R. Mechanical Characterization of Polylactic Acid, Polycarbonate, and Carbon Fiber-Reinforced Polyamide Specimens Fabricated by Fused Deposition Modeling. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2024, 33, 3613–3626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrellou, S.; Iakovidis, I.; Stratos, G.; Lemonis, I. Strength performance of carbon fiber sandwich composites with an additively manufactured fiber-reinforced polyamide grid core. Proceedings of 8th International Conference of Engineering Against Failure, Greece, 22-25 June 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Tutar, M. A Comparative Evaluation of the Effects of Manufacturing Parameters on Mechanical Properties of Additively Manufactured PA and CF-Reinforced PA Materials. Polymers 2022, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Condruz, M.; Paraschiv, A.; Badea, T.; et al. A Study on Mechanical Properties of Low-Cost Thermoplastic-Based Materials for Material Extrusion Additive Manufacturing. Polymers 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acanfora, V.; Zarrelli, M.; Riccio, A. Experimental and Numerical Assessment of the Impact behaviour of a Composite Sandwich Panel with a Polymeric honeycomb Core. International Journal of Impact Engineering 2022, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, S.; Prakash, S. Experimental investigation of laser texturing on surface roughness and wettability of PAHT CF15 fabricated by fused deposition modeling. Polymer Composites 2024, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalegani Dezaki, M.; Ariffin, M.K.A.M.; Serjouei, A.; Zolfagharian, A.; Hatami, S.; Bodaghi, M. Influence of Infill Patterns Generated by CAD and FDM 3D Printer on Surface Roughness and Tensile Strength Properties. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 7272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aloyaydi, B. ; S., Sivasankaran, S.; Al-Areqi, A.M. Investigation of infill-patterns on mechanical response of 3D printed poly-lactic-acid. Polymer Testing 2020, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butt, J.; Khan, M.A.A.; Adnan, M.; Mohaghegh, V. Performance Analysis of FFF-Printed Carbon Fiber Composites Subjected to Different Annealing Methods. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2024, 8, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lay, M.; Thajudin, N.; Abdul, H.; et al. Comparison of physical and mechanical properties of PLA, ABS and nylon 6 fabricated using fused deposition modeling and injection molding. Composites Part B: Engineering 2019, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrellou, S.; Strantzali, E.; Iakovidis, I. A decision-making strategy for selection of FDM-based additively manufactured thermoplastics for industrial applications based on material attributes. Sustainable Futures 2025, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dul, S. ; Fambri, L; Pegoretti, A. High-Performance Polyamide/Carbon Fiber Composites for Fused Filament Fabrication: Mechanical and Functional Performances. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2021, 30:5066–5085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, G.; Li, Z. ; Cheng,Y. et al. Materials & Design, 2: 12 composite parts fabricated by fused deposition modeling, Materials & Design 2018, 139, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Reference | Core Structure | Core Material | Skin Material | Tests |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alshaer 2021 [25] | honeycomb, re-entrant, pyramid, hierarchical pyramid and gyroid | PA12 | CFRP | three-point bending test |

| Ridlwan 2022 [26] |

honeycomb at 20% infill density | PLA, PC | GFRP for PLA, CFRP for PC |

bending rigidity |

| Zoumaki 2022 [27] |

honeycomb with three levels of hierarchy | PLA | fiberglass reinforced starch-based skin | three-point bending test |

| Acanfora 2023 [28] |

honeycomb with altering layers at 30% and 100% infill density | PP | CFRP | low-velocity impact test |

| Ainin 2023 [29] |

hexagonal honeycomb at 100% density varying unit cell sizes | PLA, PLA-CF, PLA-wood |

CFRP | low-velocity impact test |

| Forés - Garriga 2023 [30] | twelve 2D and seven 3D cellular cores | PEI Ultem® | CFRP |

three-point bending test |

| Junaedi 2024 [31] | gyroid at 10%, 15% and 20% infill density (PU foam into core cavities) | PLA | CFRP | flexural and compression tests |

| Francisco 2024 [32] | double arrowhead auxetic | PLA | carbon-aramid composite sheets | compression and vibration tests |

| Shah 2024 [33] | rectangular corrugated (PU foam into core cavities) | PA6-CF20%, PA6-GF25% | GFRP | quasi-static indentation test |

| Stepinac 2024 [34] | TPMS non-uniform gyroid | ASA | tempered glass | three-point bending test |

| Abas 2025 [35] | grid, cross3D and lightning at 20% density | PLA | GFRP | low-velocity impact test |

| Azeem 2025 [36] | Hexagonal, tri-hexagonal, triangles, at 10% and 100% density | PLA | GFRP | tensile properties |

| Brejcha 2025 [37] | truss-type structure | PLA, balsa, PVC foam | flax fiber fabric | three-point bending test |

| Kalaimagal 2025 [38] | triangular, hexagonal and trihexagonal at 40% infill density | PLA + GF16% | layers of aluminum and Kevlar fiber | low-velocity impact test |

| Mirzaei 2025 [39] | honeycomb | PLA | CFRP or GFRP | compression and bending test |

| Muralidharan 2025 [40] | honeycomb, x-shape, tubular hollow, triangular, tubular solid | PLA | CFRP | three-point bending test |

| Reference | Material | Infill Pattern | Printing Parameters | Properties | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Naranjo- Lozada 2019 [44] | PA6, Onyx | rectangular, triangular | Variation of infill density (10%, 70%) | tensile strength at break, elastic modulus | The triangular pattern provided better tensile performance, as there were more strands oriented in the direction of load. |

| Rao 2019 [45] | PLA-CF |

cubic, cubic subdivision, quarter cubic | Variation of extrusion temperature and layer height (0.1mm, 0.2mm, 0.3mm) | tensile strength |

Tensile strength was mainly affected by layer height, followed by extrusion temperature and infill pattern. The highest tensile strength was obtained for the cubic pattern at 0.1 mm layer height and 225°C extrusion temperature. |

| Ma 2020 [46] | PLA, PLA-CF |

triangles, rectilinear, lines, honeycomb | 0.2 mm layer height; Variation of infill density (20%,40%, 60%, 80%) | compressive modulus, energy absorption capability | For PLA, the highest compressive modulus was obtained for the honeycomb pattern at 80% infill density, followed by triangle. For PLA/CF, the highest compressive modulus was obtained for the triangle pattern at 80% infill density, followed by honeycomb. |

| Mishra 2021 [19] | PLA-CF |

cubic, triangles, tri-hexagonal | Variation of layer height (0.1mm, 0.2mm, 0.3 mm), infill density (40%, 60%, 80%), printing speed | tensile and flexural strength |

The tri-hexagonal pattern provided higher tensile and flexural strength, followed by triangles and cubic. The highest tensile and flexural strength was obtained for the tri-hexagonal pattern at 0.3 mm layer height and 80% infill density. |

| Ansari 2022 [47] | PLA-CF |

grid, triangular, tri-hexagonal |

0.2 mm layer height; Variation of print speed, infill density (50%, 75%, 100%), nozzle temperature | impact Izod strength, hardness, dimensional accuracy | The maximum impact strength was obtained for the grid pattern at 75% infill density and 240oC nozzle temperature. The highest hardness value was obtained for tri-hexagonal pattern at 75% infill density and for the grid and triangular patterns at 100% infill density. |

| Pop 2022 [48] | PAHT-CF |

grid, lines, triangles |

0.2 mm layer height; 50% infill density | bending and tensile strength | Tensile strength was found higher for the lines pattern followed by triangles and grid. Bending strength was found higher for triangles followed by lines and grid. Defects decreased from grid pattern to lines pattern while they were insignificant for the triangles pattern. |

| Rodríguez-Reyna 2022 [20] | Nylon-CF, PLA, ABS |

tridimensional, hexagonal, linear | Variation of infill density (33%, 66%, 100%) | ultimate tensile stress, young’s modulus | For Nylon-CF, the higher tensile strength was obtained for tridimensional pattern, followed by hexagonal and linear, regardless of the infill density. |

| Sun 2023 [49] | PA6-CF20, PA6-CF25 | triangular, hexagonal, kagome, re-entrant |

0.15 mm layer height; 100% infill density; variation of raster angle | energy absorption capability | The kagome honeycomb pattern provided the highest specific energy absorption, with a value comparable to that of metals. |

| Abali 2024 [50] | PLA-CF | lines, gyroid | Variation of infill density (50%, 75%, 100%) | bending strength | Specimen with the lines pattern exhibited a higher maximum load compared to gyroid pattern at 75% and 100% infill densities, indicating higher toughness. |

| Andreozzi 2024 [51] | PA6, CF-GF |

concentric, grid, honeycomb | 0.25mm layer height, 50% infill density for honeycomb and grid, 100% infill density for concentric and grid | compression strength, modulus, yield, and strain at peak |

For 50% infill density, the grid pattern provided higher compression strength compared to honeycomb. For 100% infill density, the concentric pattern provided the highest compression strength and superior compression modulus. The highest peak deformation was observed for the grid pattern at 100% density. |

| Hozdić 2024 [52] | PETG, PETG-CF |

hexagonal, triangles, linear |

0.2 mm layer height; Variation of infill density (30%, 60%, 100%) | tensile strength young’s modulus, nominal strain at break | For both PETG and PETG-CF, the hexagonal pattern provided the highest tensile strength. The linear pattern provided the highest young's modulus indicating rigidity, but also lower ductility. |

| Printing Parameters | Value |

|---|---|

| Layer height (mm) | 0.15 |

| Initial layer height (mm) | 0.27 |

| Raster width (mm) | 0.58 |

| Number of walls | 3 |

| Wall thickness (mm) | 1.74 |

| Number of top layers | 3 |

| Number of bottom layers | 3 |

| Top/bottom thickness (mm) | 0,9 |

| Build orientation | XY |

| Infill density (%) | 50%, 100% |

| Infill pattern | Lines, Cubic, Concentric |

| Top/bottom layers pattern | Lines, Concentric |

| Infill overlap | 10% |

| Infill flow, top/bottom flow | 100% |

| Print speed (mm/s) | 30 |

| Initial layer speed (mm/s) | 15 |

| Extrusion head type | CC 0.6 mm |

| Nozzle printing temperature (oC) | 270 |

| Build plate temperature (oC) | 100 |

| Raft material | None |

| Infill Pattern | Top/Bottom Pattern | Code | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lines |  |

Lines | P100LL |

| Concentric |

|

Concentric | P100OO |

| Cubic |  |

Lines | P100CL |

| Concentric | P100CO | ||

| Tensile Properties | Impact Strength (J/cm2) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Specimens | σmax (ΜPa) | % εmax | Face-Up | Side |

| P100LL | 93.4 ± 0.5 | 5.7 ± 0.3 | - | - |

| P100OO | 127.8 ± 3.4 | 7.0 ± 0.7 | 3.29 ± 0.08 | 2.63 ± 0.11 |

| P100CL | 96.5 ± 13.0 | 6.3 ± 1.0 | 2.65 ± 0.47 | 2.56 ± 0.09 |

| P100CO | 117.3 ± 4.5 | 4.8 ± 0.2 | 1.99 ± 0.16 | 2.51 ± 0.14 |

| Specimens | Length | Width | Thickness |

|---|---|---|---|

| P100LL | 100.39 | 10.41 | 3.17 |

| P100OO | 100.18 | 10.23 | 3.06 |

| P100CL | 100.71 | 10.48 | 3.14 |

| P100CO | 100.31 | 10.22 | 3.05 |

| CAD model | 100.00 | 10.00 | 3.00 |

| Specimens | Mass (g) | Water Absorbed (mg/cm3) |

St. Dev. | Water Absorbed (%) |

St. Dev. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P100 | 3.190 | 131.671 | 33.589 | 13.048 | 3.280 |

| P50 | 2.626 | 199.638 | 38.862 | 23.852 | 4.643 |

| P50R | 3.110 | 118.973 | 25.930 | 13.383 | 2.917 |

| Specimens | I | II | III | IV | V | Mean | |

| P100 | face-up | 79.5 | 78.5 | 79.0 | 78.0 | 80.5 | 79.1 |

| P100 | face-down | 80.5 | 81.5 | 79.5 | 76.0 | 80.0 | 79.5 |

| P100 | side | 72.5 | 71.3 | 70.0 | 70.5 | 70.5 | 71.0 |

| P50R | face-up | 82.5 | 86.5 | 82.3 | 86.5 | 80.5 | 83.7 |

| P50R | face- down | 82.5 | 81.5 | 84.5 | 80.0 | 82.8 | 82.3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).