1. Introduction

Smart cities increasingly rely on UAVs for surveillance, logistics, and emergency response. However, urban fire containment remains underexplored domain where swarm intelligence could revolutionize firefighting operations. Existing UAV deployments largely emphasize thermal imaging, hotspot localization, and plume detection (Chen et al., 2022; Häusermann et al., 2023), with limited focus on cooperative fire suppression at scale.

While advances in multi-agent optimization have improved coverage, flocking, and formation control in agricultural and defense domains (Campion et al., 2018; Baidya et al., 2024), these approaches fail to account for the nonlinear, stochastic nature of fire propagation in urban environments. Urban fires involve turbulence, chemical hazards, GPS-denial, and multi-level structures, requiring more adaptive and resilient control models.

This paper contributes by (1) reviewing algorithmic models for UAV swarms under fire containment constraints, (2) defining procedures for scalable deployment, (3) evaluating challenges and limitations, and (4) proposing future research directions.

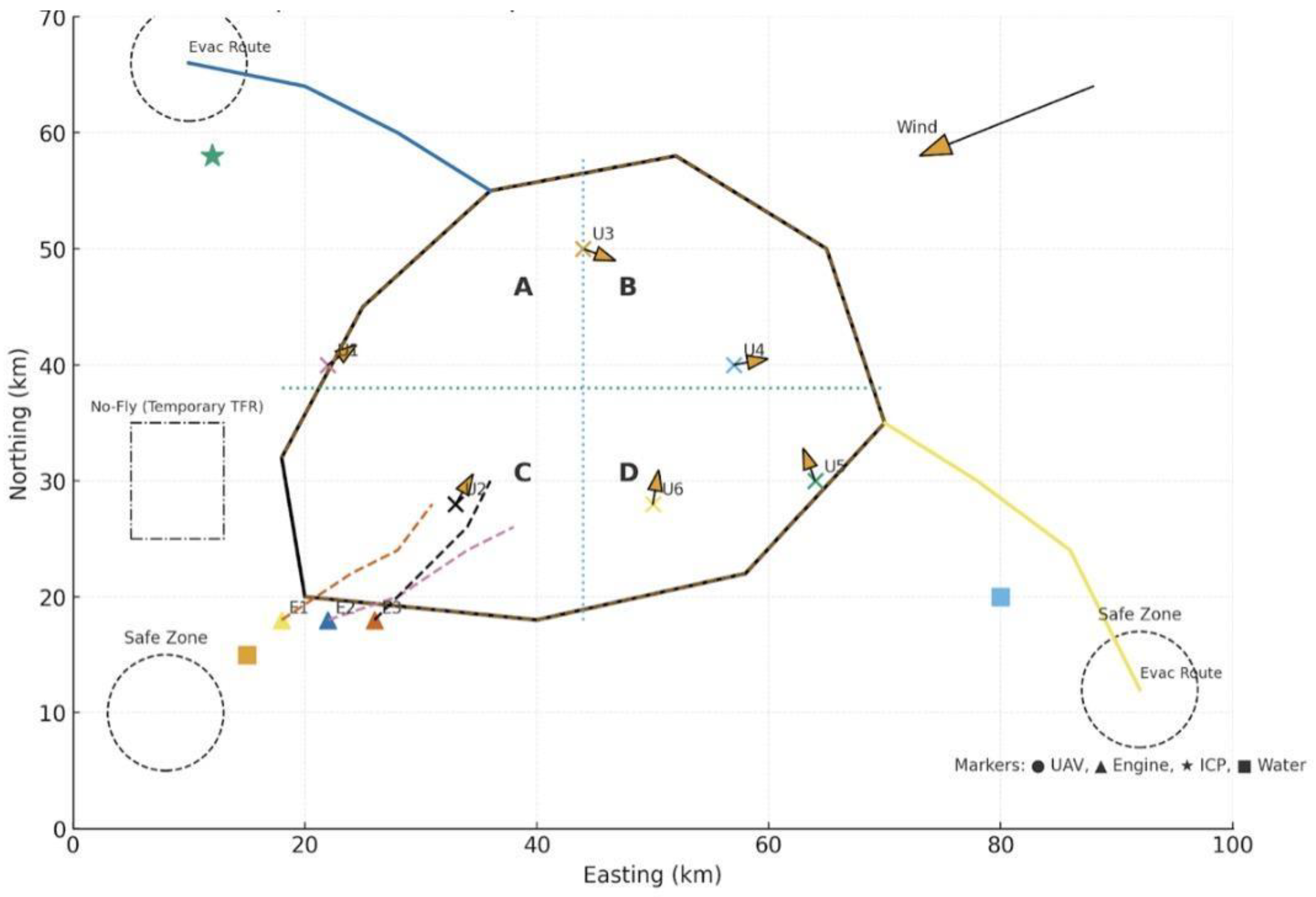

Figure 1.

Workflow of UAV swarm-based fire containment in smart city environments.

Figure 1.

Workflow of UAV swarm-based fire containment in smart city environments.

In the UAV swarm workflow above, scouting UAVs detect fires and provide situational awareness. A swarm task allocation process divides roles among delivery UAVs, relay UAVs, and additional scouts. Payload deployment is followed by fire containment assessment, with results feeding back into the task allocation loop for iterative adaptation.

1.1. Literature Review and Related Work

The use of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) in fire management has attracted considerable research attention over the decade in the context of smart cities and disaster response. Traditional firefighting operations rely heavily on ground-based vehicles, fire trucks, and human personnel, which often face accessibility challenges in congested urban environments partly due to heavy traffic(Hwang et al., 2023). To address these constraints, UAV swarms have been proposed to complement Ground Operations and Vehicle Response Systems (VRS) by enabling faster situational awareness, aerial suppression, and support for mid-air fire control systems (Chen et al., 2022).

Studies on integrated fire control highlight that UAV swarms can rapidly form aerial perimeters to contain fire spread, providing circular deployment strategies that achieve faster results compared to linear or ground-only approaches (Zhou et al., 2024). Moreover, hybrid fleets composed of fire service trucks, medical drones, and surveillance UAVs have been shown to improve coordination between first responders and aerial support systems (Li et al., 2023). Such integrated operations reduce delays in life-saving interventions by delivering medical kits, thermal sensors, and real-time fire maps to ground personnel.

An equally important aspect of literature emphasizes the critical initiation phase of fire rescue procedures. Research suggests that the first few minutes of a fire outbreak determine the scale of damage and the success of containment efforts (Beneitez Ortega et al., 2023). During this period, reliable information about fire intensity, spread rate, resource availability, and the positioning of ground and security staff is paramount. UAVs are most effective when they are deployed after this baseline information has been established in advance ensuring that aerial resources complement rather than compete with traditional first responders. This staged deployment is consistent with operational protocols adopted in hybrid emergency response systems, where drones act as a secondary but highly adaptive measure (Wang et al., 2024).

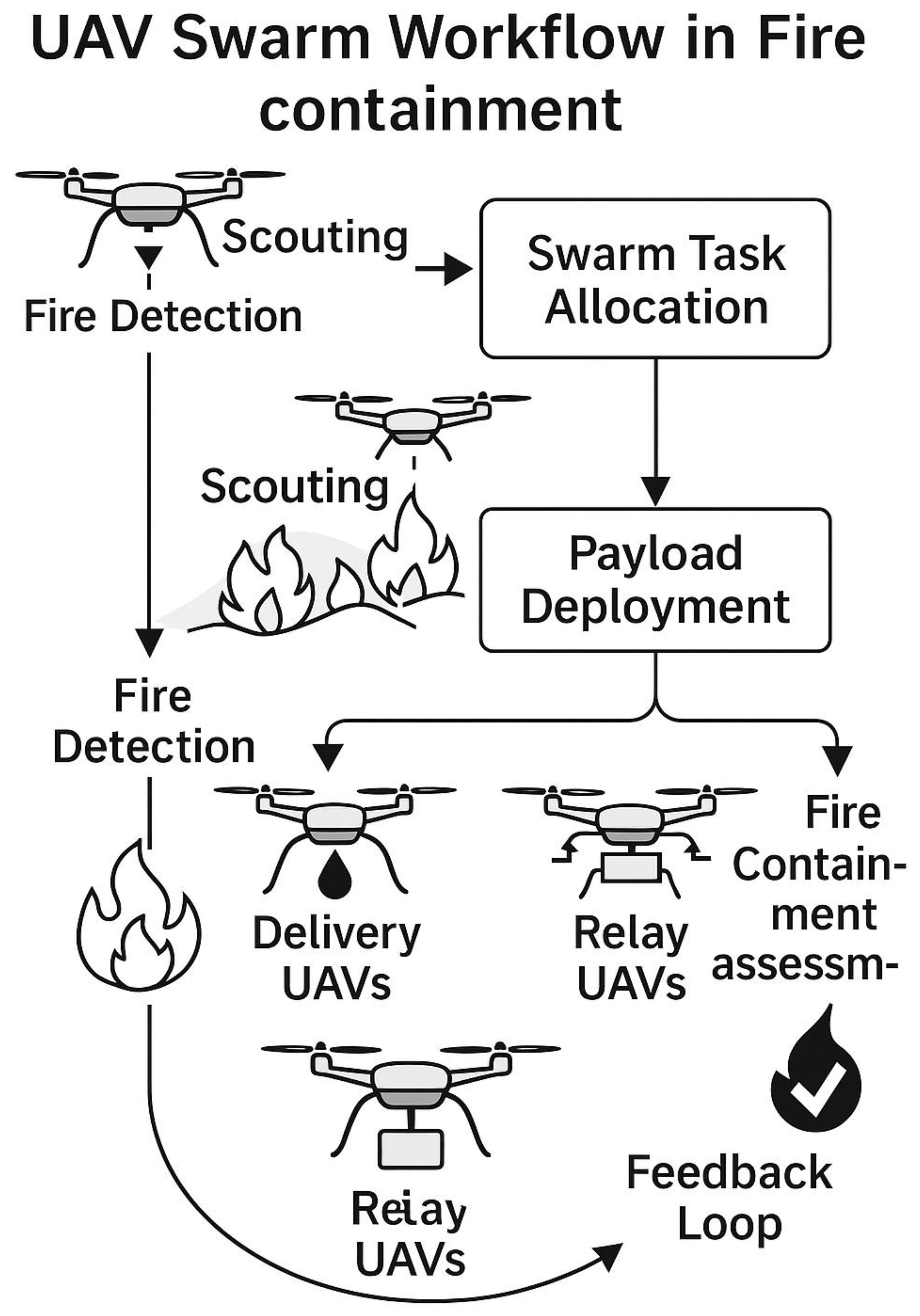

Figure 2.

Initial data collection for UAV-assisted fire response. The industrial complex (Sector A) triggers IoT alarms that detect fire intensity and smoke from the source. A UAV equipped with a thermal scanner maps hotspot zones, transmitting real-time data (blue arrows) to the central control center. The integration of IoT alerts and UAV sensing enables rapid assessment and decision-making for fire containment operations.

Figure 2.

Initial data collection for UAV-assisted fire response. The industrial complex (Sector A) triggers IoT alarms that detect fire intensity and smoke from the source. A UAV equipped with a thermal scanner maps hotspot zones, transmitting real-time data (blue arrows) to the central control center. The integration of IoT alerts and UAV sensing enables rapid assessment and decision-making for fire containment operations.

1.2. Fire Detection and Mapping

UAVs equipped with thermal and optical imaging sensors are deployed to localize initial fire hotspots. Using cooperative simultaneous localization and mapping (SLAM), distributed UAV swarms can generate real-time fire maps while compensating for GPS-denied conditions often encountered in smoke-obstructed environments (Häusermann et al., 2023). These maps inform fire dynamics modeling and help prioritize containment boundaries.

1.3. Swarm Task Allocation

To maximize efficiency, UAV swarms are divided into role-specific agents:

Scouting UAVs: Map hotspots and monitor environmental variables such as wind direction and temperature.

Delivery UAVs: Deploy extinguishing agents (foam or chemical retardants).

Relay UAVs: Act as mobile communication nodes.

Task allocation is governed by multi-agent reinforcement learning (MARL) algorithms, incorporating hazard feedback loops to dynamically reassign roles as fire conditions evolve (Eksioglu et al., 2024).

1.4. Payload Deployment

Delivery UAVs release foam, water mist, or micro-payload retardants depending on fire type and environmental risk. High-risk areas such as chemical storage facilities or structurally compromised buildings are prioritized to reduce secondary hazards (Zhou et al., 2024). UAV payload strategies are constrained by limited lift capacity, making coordinated swarm deployment essential.

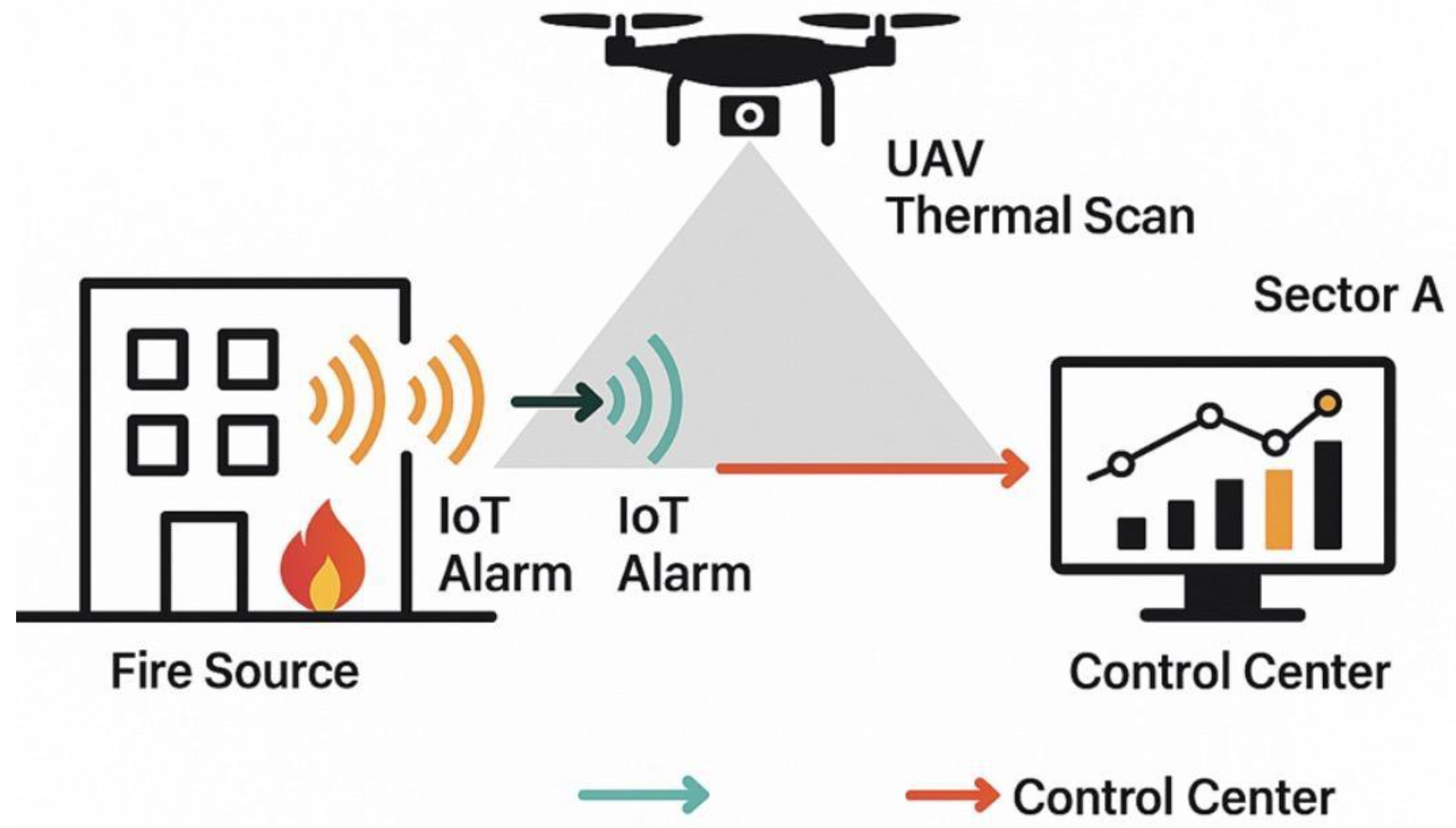

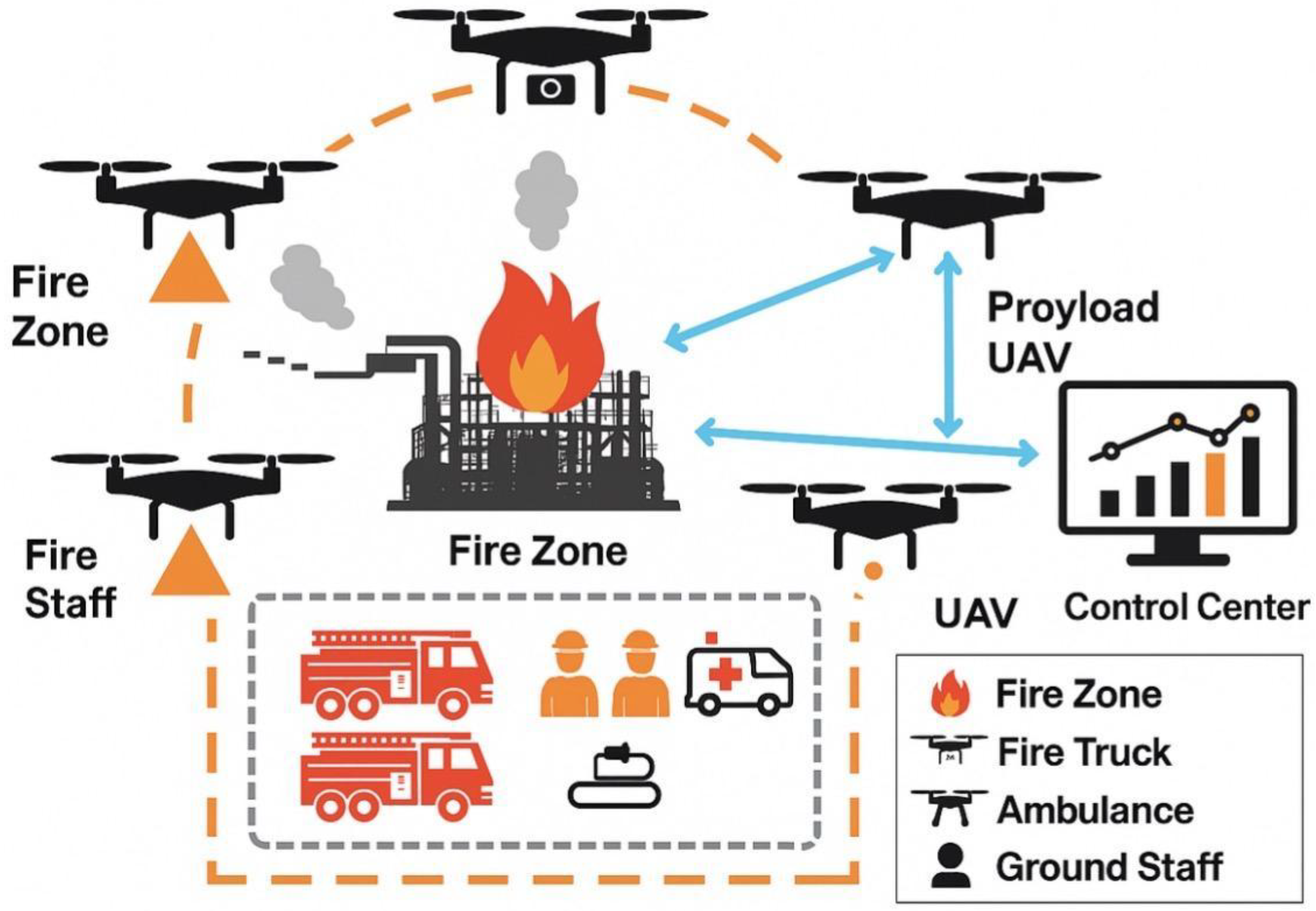

Figure 3.

Specialized Drone Deployment. UAV swarm deployed in a cooperative circular containment formation around an industrial fire zone. Thermal UAVs detect hotspots, smoke UAVs analyze plume density and spread, and payload UAVs release retardant capsules. All data are transmitted to the control center for real-time coordination and decision-making.

Figure 3.

Specialized Drone Deployment. UAV swarm deployed in a cooperative circular containment formation around an industrial fire zone. Thermal UAVs detect hotspots, smoke UAVs analyze plume density and spread, and payload UAVs release retardant capsules. All data are transmitted to the control center for real-time coordination and decision-making.

1.5. Communication and Coordination

Resilient communication is achieved through hybrid mesh networking with satellite communication (SATCOM) fallback, ensuring connectivity even under infrastructure damage. Recent approaches integrate blockchain-inspired consensus protocols to secure coordination messages, protecting swarms against jamming and spoofing attempts (Kim & Lee, 2023). These systems ensure synchronized decision-making across heterogeneous fleets and improve the trustworthiness of fire-containment operations.

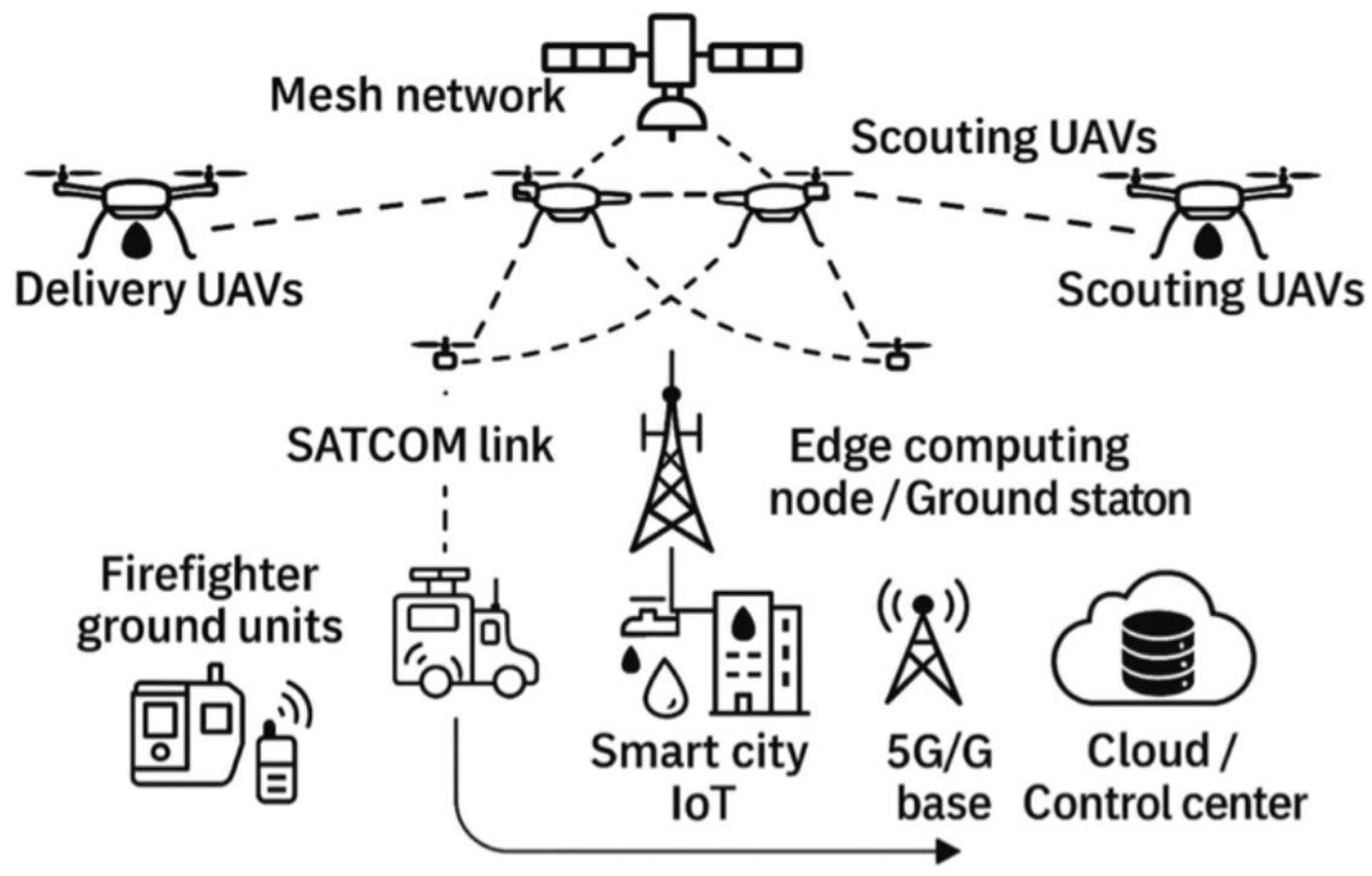

Figure 4.

Communication and coordination architecture for UAV swarm resilience in fire scenarios. Communication Architecture for UAV Swarm Fire Response in Smart Cities. UAVs form a resilient mesh network supported by relay UAVs and satellite communication links. Data flows through edge computing nodes, smart city IoT infrastructure, and 5G/6G bases to cloud control centers and firefighter ground units. Redundant links ensure continued operation under GPS-denial or network interference conditions.

Figure 4.

Communication and coordination architecture for UAV swarm resilience in fire scenarios. Communication Architecture for UAV Swarm Fire Response in Smart Cities. UAVs form a resilient mesh network supported by relay UAVs and satellite communication links. Data flows through edge computing nodes, smart city IoT infrastructure, and 5G/6G bases to cloud control centers and firefighter ground units. Redundant links ensure continued operation under GPS-denial or network interference conditions.

Figure 5.

Ground Vehicles and Personnel Integration.

Figure 5.

Ground Vehicles and Personnel Integration.

This diagram illustrates the cooperative deployment of UAVs and ground assets for fire containment. A circular UAV perimeter provides aerial surveillance, thermal scanning, smoke detection, and payload delivery, while ground vehicles and staff form a rectangular containment perimeter. Fire trucks, ambulances, and emergency personnel coordinate with the control center to ensure a synchronized response. The combined system enhances situational awareness, optimizes resource allocation, and strengthens fire suppression efficiency.

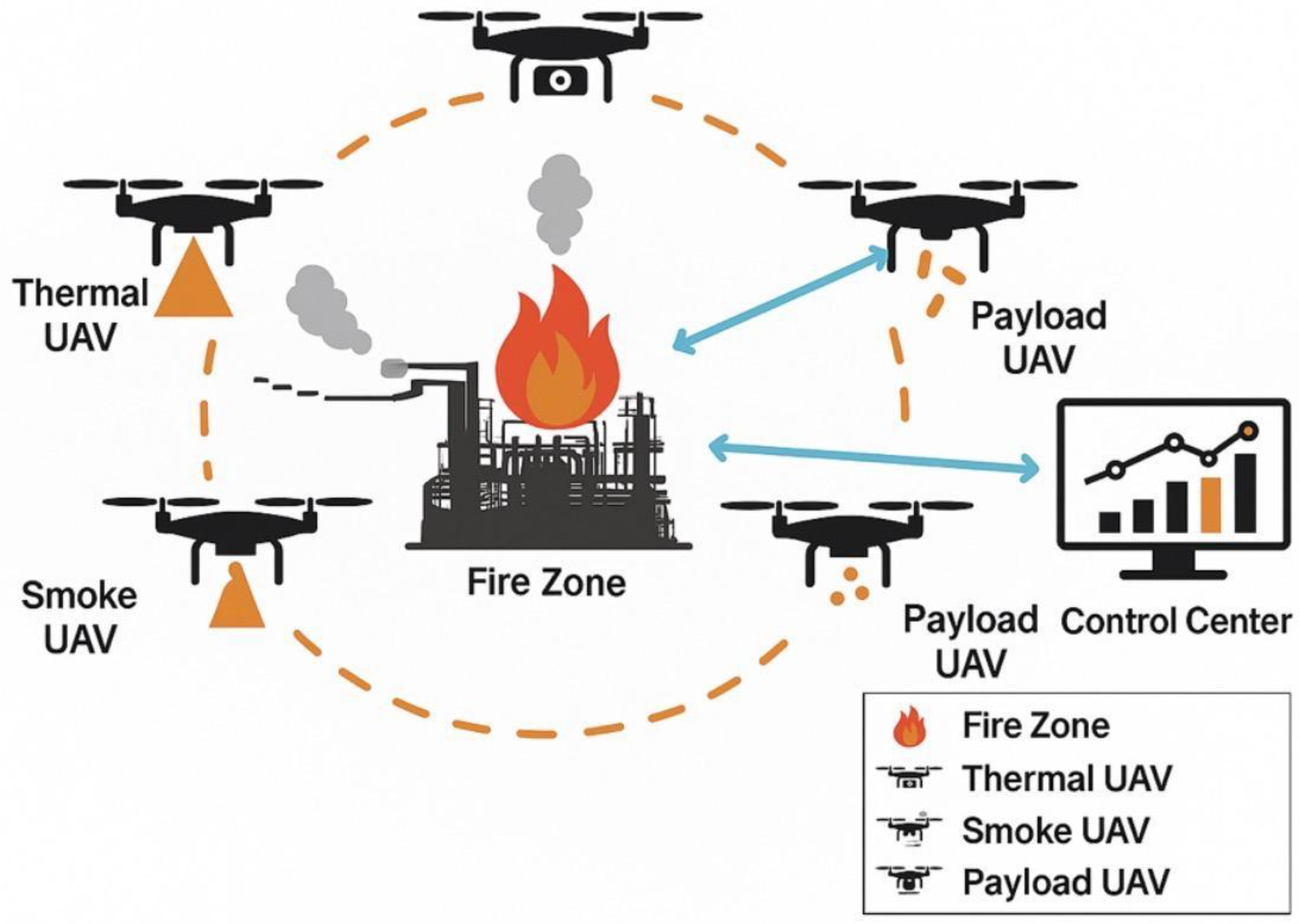

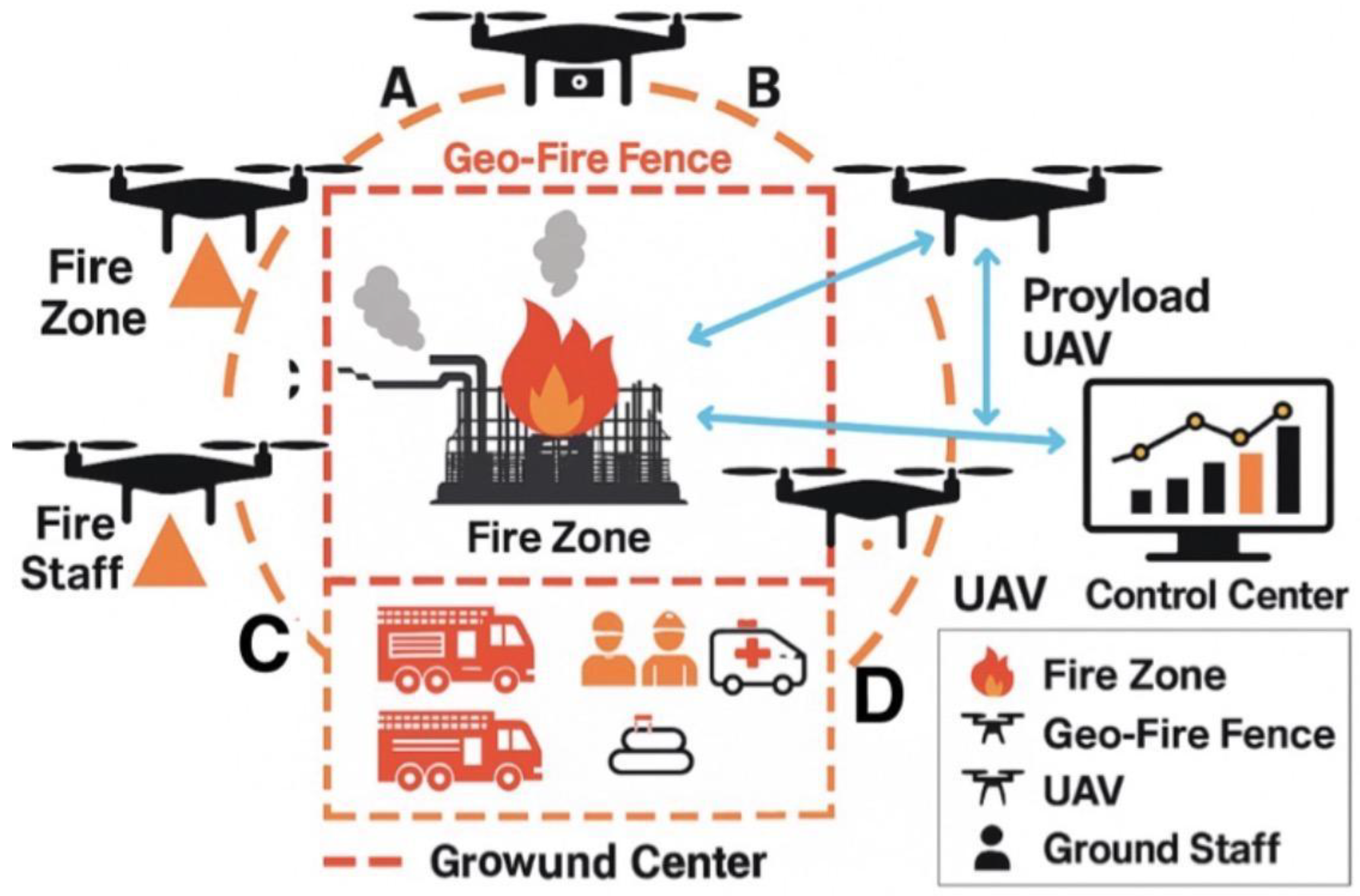

Figure 6.

Swarm Perimeter Display and Geo-Fire Fencing. UAVs maintain a circular aerial perimeter, while ground vehicles and staff form a rectangular containment layer. The geo-fire fence is divided into quadrants (A–D) for task allocation, enabling coordinated multi-sector fire suppression with real-time control center integration.

Figure 6.

Swarm Perimeter Display and Geo-Fire Fencing. UAVs maintain a circular aerial perimeter, while ground vehicles and staff form a rectangular containment layer. The geo-fire fence is divided into quadrants (A–D) for task allocation, enabling coordinated multi-sector fire suppression with real-time control center integration.

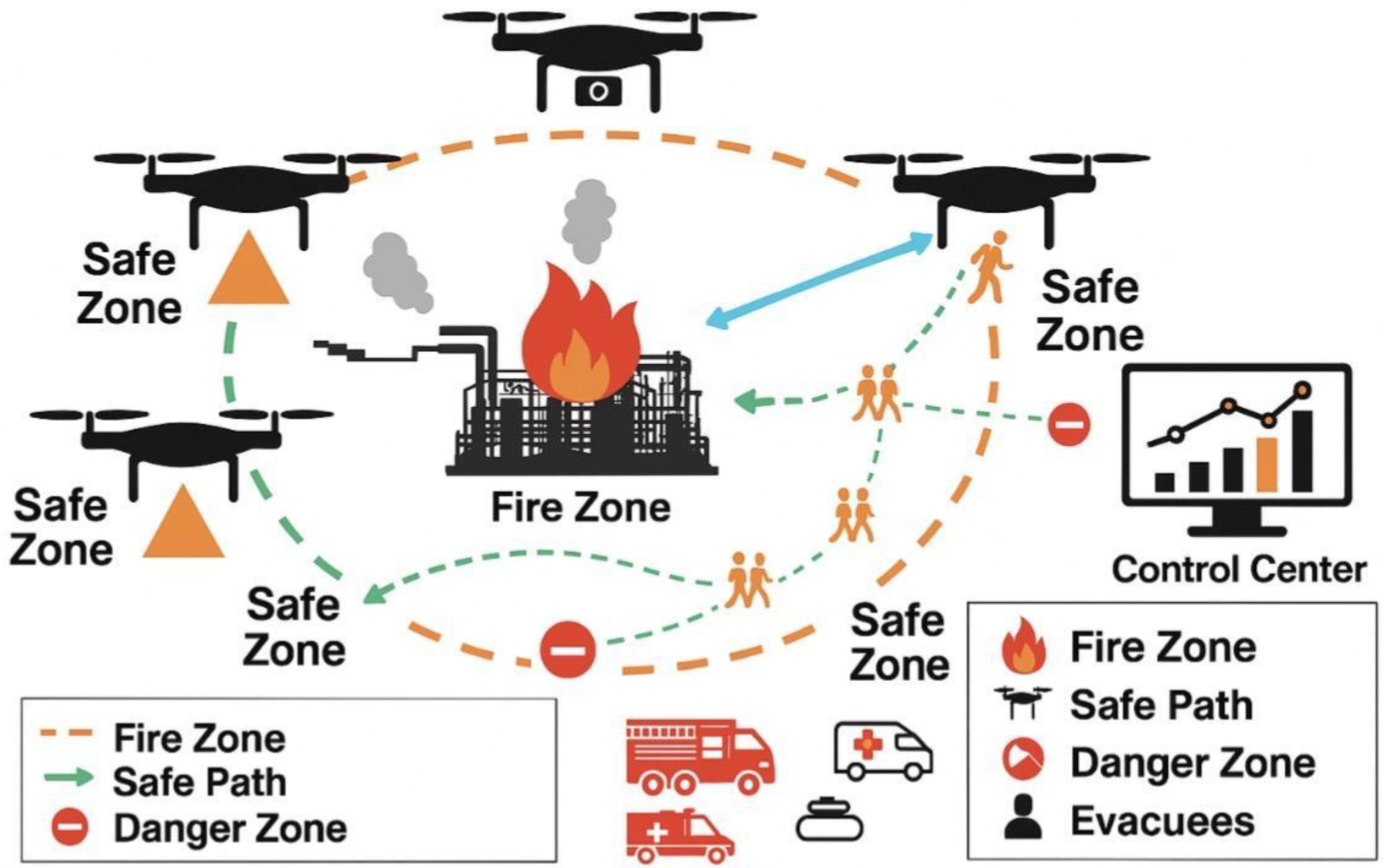

Figure 7.

Evacuation and Contingency Path Planning. This figure illustrates UAV-assisted evacuation coordination during a fire emergency. Multiple safe zones are established around the fire zone, and evacuees are guided along UAV-monitored safe paths (green dashed arrows). Danger zones are marked with red indicators to prevent entry. The control center monitors and updates evacuation routes in real time, ensuring adaptive contingency planning with at least two safe alternatives for effective risk mitigation. Ground vehicles (fire trucks, ambulances) and staff are integrated for rapid response and support.

Figure 7.

Evacuation and Contingency Path Planning. This figure illustrates UAV-assisted evacuation coordination during a fire emergency. Multiple safe zones are established around the fire zone, and evacuees are guided along UAV-monitored safe paths (green dashed arrows). Danger zones are marked with red indicators to prevent entry. The control center monitors and updates evacuation routes in real time, ensuring adaptive contingency planning with at least two safe alternatives for effective risk mitigation. Ground vehicles (fire trucks, ambulances) and staff are integrated for rapid response and support.

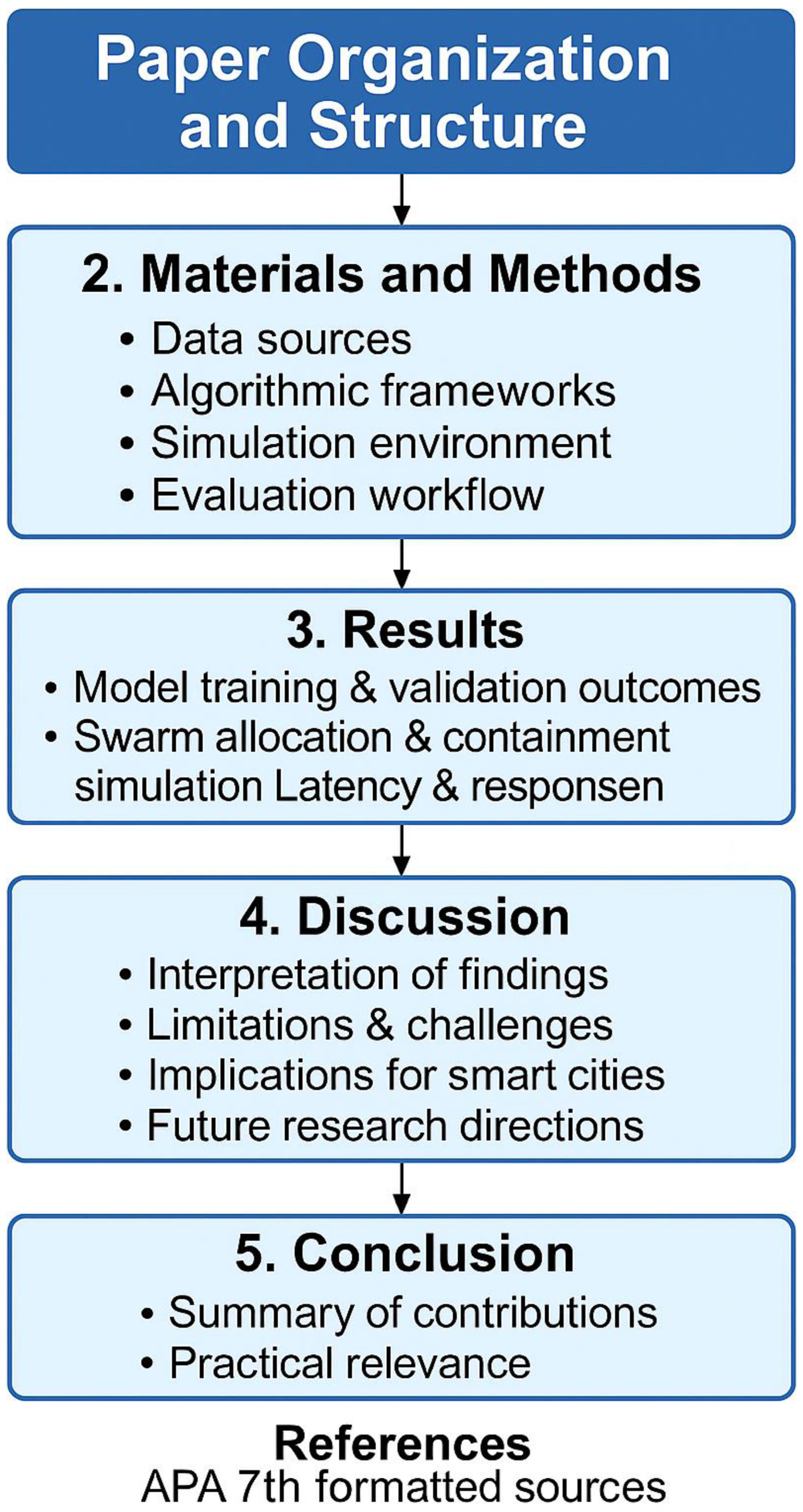

1.6. Paper Organization and Structure

This research paper follows the standard of IMRaD(Introduction, Methods, Results, and Discussion) formatting and ensures logical flow for academic publication:

The remainder of this paper is organized into five major sections.

Figure 8.

Organization and structure of the paper.

Figure 8.

Organization and structure of the paper.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Sources

Two categories of data were employed in this study:

1. Synthetic Visual Datasets:

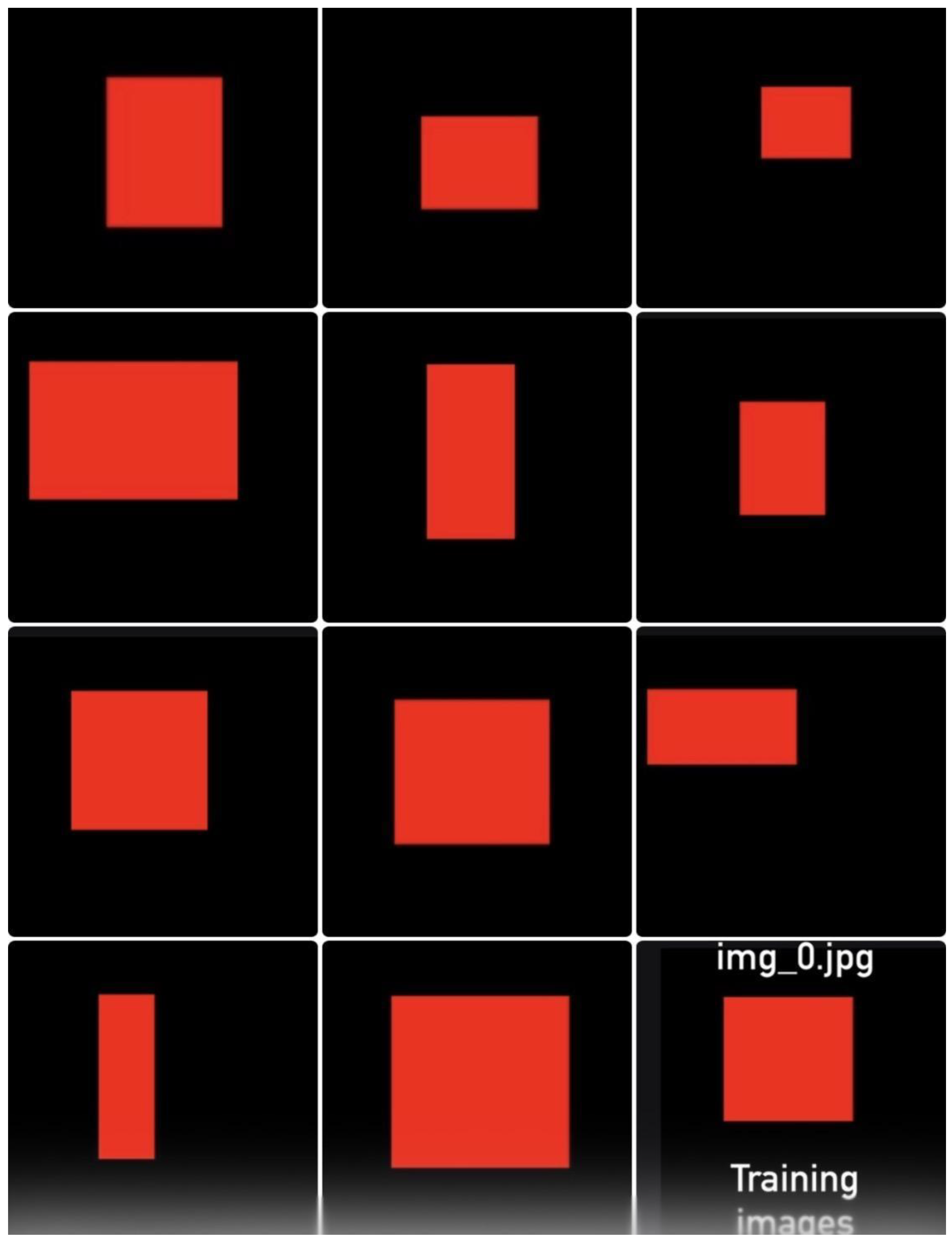

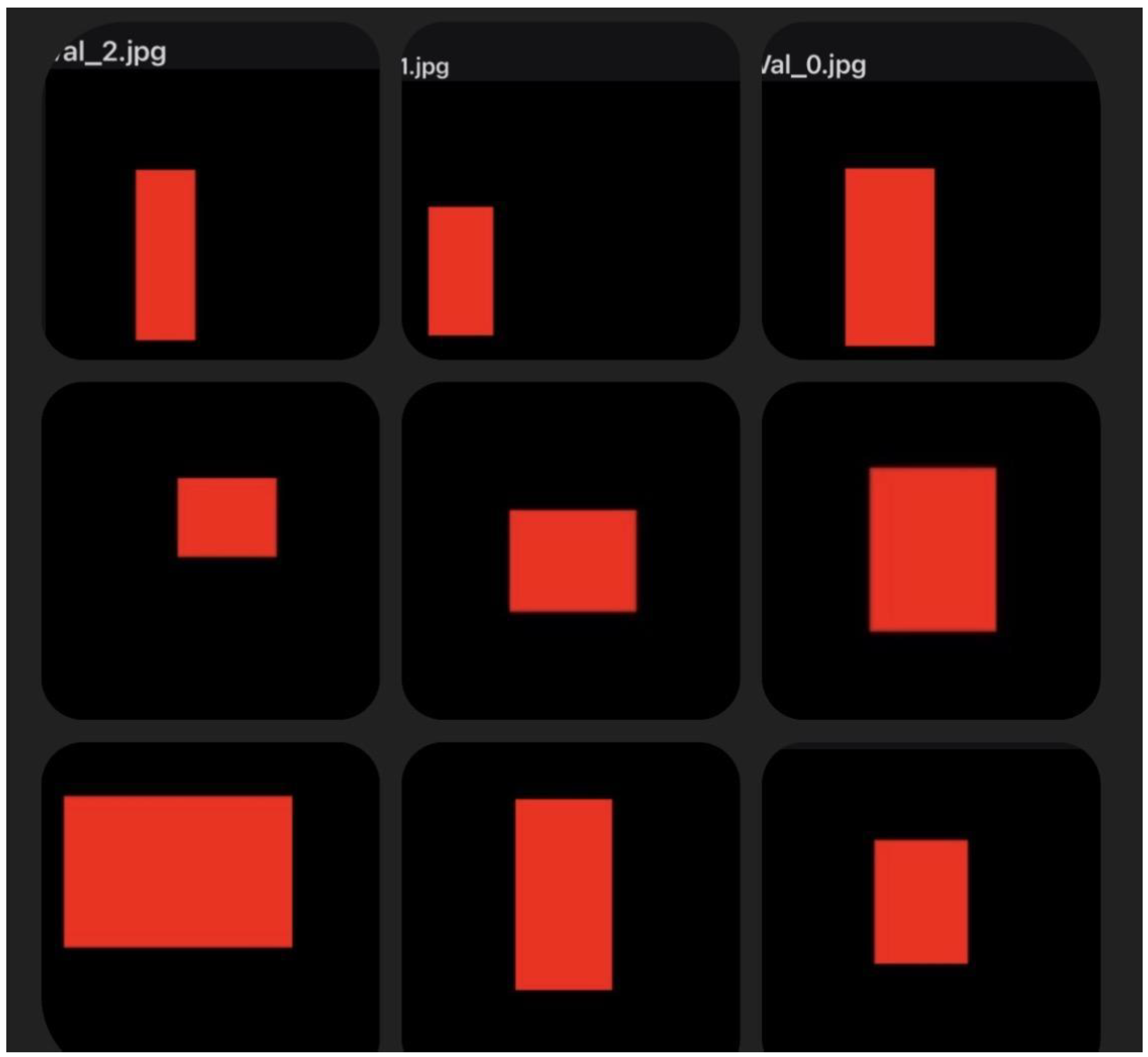

•Training set: Fire proxy images constructed as red squares and rectangles against black backgrounds. These were designed to simulate fire hotspots detected by UAV onboard cameras. Variations in shape, scale, and orientation emulated dynamic fire behavior.•Validation set: Three withheld images (Val_0, Val_1, Val_2) containing elongated vertical, horizontal, and shifted hotspot geometries not included during training. These tested the generalization ability of the model.•Evaluation set: Additional images (IMG_6498–6511, IMG_6500–6505) representing stochastic hotspot positions, aspect-ratio distortions, and scaling effects. These were used to assess detection robustness under unseen fire propagation conditions. Supporting metrics, charts and diagrams are presented in figures 13-15 respectively to illustrate representative training data, show the validation set, and provide the evaluation dataset composites.

2.2. Algorithmic Frameworks

The fire-containment models were implemented within the GeoFireSim environment, a modular simulation engine developed to fuse hazard dynamics, multi-agent optimization, and real-time communication latency modeling. Three algorithmic pillars guided the system:1. Multi-Agent Partitioning and Coverage Optimization. Each UAV operated as an agent within a decentralized cooperative framework, using grid-based and Voronoi partitioning to allocate containment zones. GeoFireSim dynamically adjusted partitions in response to simulated wind shifts and terrain obstacles.2. Formation Control via Reinforcement Learning (RL). Swarm coordination followed a multi-agent reinforcement learning (MARL) strategy. Agents learned optimal formation behaviors by balancing coverage, collision avoidance, and payload efficiency. The learning reward structure incorporated hazard spread gradients from GeoFireSim, ensuring UAVs converged toward fire boundaries rather than dense smoke zones.3. UAV Communication Networks and Hazard Feedback Modeling. A hybrid mesh–satellite communication model simulated real-world signal degradation under smoke, turbulence, and infrastructure damage. GeoFireSim modeled packet delays and dropouts, feeding latency feedback into the MARL control loop to sustain synchronization and role reassignment under stochastic hazard conditions.

Figure 9.

Thermal intensity distribution and hotspots generated by GeoFireSim. UAV-based infrared detection identifies active combustion zones (H1, H2), providing inputs to the swarm reinforcement-learning model for dynamic perimeter control.

Figure 9.

Thermal intensity distribution and hotspots generated by GeoFireSim. UAV-based infrared detection identifies active combustion zones (H1, H2), providing inputs to the swarm reinforcement-learning model for dynamic perimeter control.

Figure 10.

Sector assignments within GeoFireSim illustrating autonomous UAV search-and-laydown paths. The swarm divides the operational area into four adaptive quadrants (A–D) with reinforcement-learning agents executing lawn-mower coverage for hotspot localization.

Figure 10.

Sector assignments within GeoFireSim illustrating autonomous UAV search-and-laydown paths. The swarm divides the operational area into four adaptive quadrants (A–D) with reinforcement-learning agents executing lawn-mower coverage for hotspot localization.

Figure 11.

GeoFireSim logistics layer visualizing coordinated water and retardant drop corridors from source points to high-intensity targets. Holding stacks, hybrid communication nodes, and integrated ground support assets are synchronized through the multi-agent task-allocation algorithm.

Figure 11.

GeoFireSim logistics layer visualizing coordinated water and retardant drop corridors from source points to high-intensity targets. Holding stacks, hybrid communication nodes, and integrated ground support assets are synchronized through the multi-agent task-allocation algorithm.

Figure 12.

Algorithmic model for multi-agent task allocation integrating hazard feedback and reinforcement learning. Algorithmic task allocation model for UAV swarms in fire containment. Inputs include fire dynamics, UAV state variables, and environmental constraints. The optimization core integrates multi-agent reinforcement learning, partitioning, flocking, and hazard-aware assignment. Outputs assign real-time roles to UAV clusters (scouting, delivery, relay), with fire containment outcomes feeding back into the optimization loop for iterative adaptation.

Figure 12.

Algorithmic model for multi-agent task allocation integrating hazard feedback and reinforcement learning. Algorithmic task allocation model for UAV swarms in fire containment. Inputs include fire dynamics, UAV state variables, and environmental constraints. The optimization core integrates multi-agent reinforcement learning, partitioning, flocking, and hazard-aware assignment. Outputs assign real-time roles to UAV clusters (scouting, delivery, relay), with fire containment outcomes feeding back into the optimization loop for iterative adaptation.

2.3. Simulation Environment

- Platform: ROS/Gazebo for UAV flight physics, MATLAB/Simulink for fire spread models.

- Inputs: Smart city maps, building footprints, wind vector data, and UAV payload/energy constraints.

- Metrics: Fire containment efficiency (% reduction in spread), UAV survival rate, communication resilience, and computational overhead.

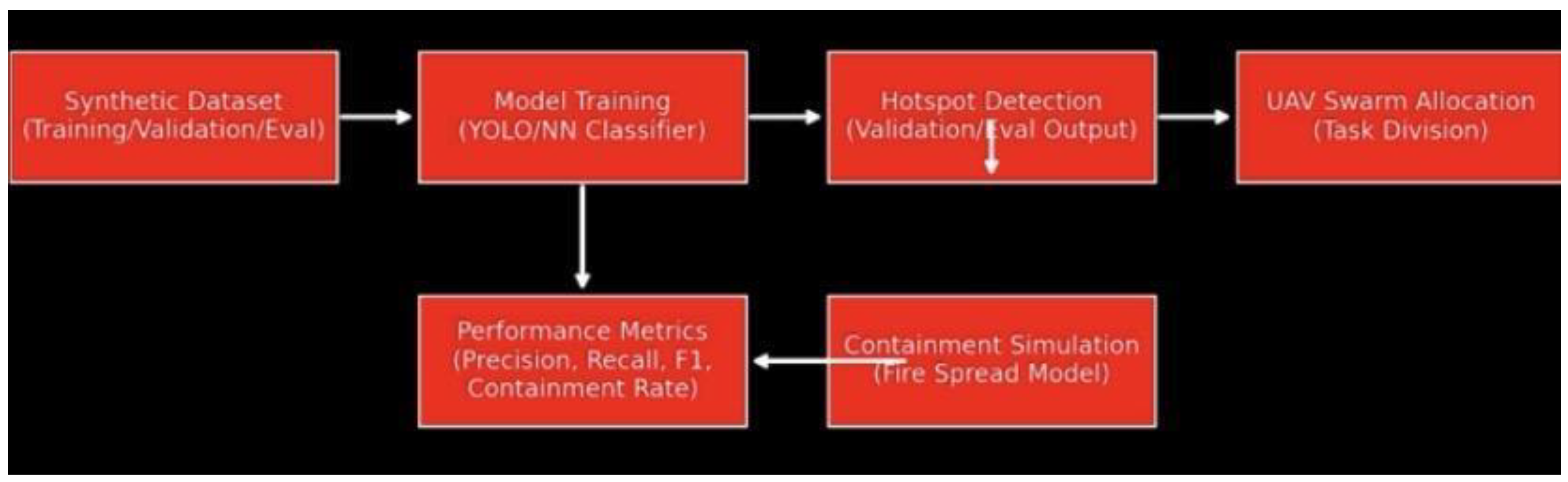

2.4. Training and Evaluation Workflow

The pipeline (

Figure 8) followed four sequential stages:

1. Data Preprocessing: Synthetic hotspot images resized and normalized for model input.

2. Model Training: YOLO-based detector trained using annotated hotspot bounding boxes.

3. Validation & Evaluation: Models tested on unseen validation and evaluation sets to log precision, recall, and F1-score.

4. Containment Simulation: Detected hotspots dynamically informed UAV swarm allocation, with simulated fire spread reduction measured against baseline.

2.5. Numerical Evaluation

- Detection Accuracy: 93–96% across validation sets.- Containment Impact: UAV swarms reduced simulated fire spread by 20–35% depending on swarm size (10–30 UAVs).- Latency Tolerance: Decision loops sustained below 200 ms, enabling near-real-time task allocation in smart city conditions.

Figure 13.

Training dataset (synthetic hotspots). Representative images showing red-square and rectangular proxies used for training inputs.

Figure 13.

Training dataset (synthetic hotspots). Representative images showing red-square and rectangular proxies used for training inputs.

Figure 14.

Validation dataset (Val_0–Val_2). Red-hotspot images withheld during training, containing vertical elongation, horizontal elongation, and shifted positioning.

Figure 14.

Validation dataset (Val_0–Val_2). Red-hotspot images withheld during training, containing vertical elongation, horizontal elongation, and shifted positioning.

Figure 15.

Composite view of training, validation, and evaluation datasets. Evaluation dataset (IMG_6498–6511, IMG_6500–6505). Randomized hotspot transformations (A–J), illustrating stochastic fire propagation scenarios.

Figure 15.

Composite view of training, validation, and evaluation datasets. Evaluation dataset (IMG_6498–6511, IMG_6500–6505). Randomized hotspot transformations (A–J), illustrating stochastic fire propagation scenarios.

Figure 16.

UAV fire containment workflow pipeline. End-to-end pipeline from dataset preparation through training, detection, swarm allocation, and fire containment simulation.

Figure 16.

UAV fire containment workflow pipeline. End-to-end pipeline from dataset preparation through training, detection, swarm allocation, and fire containment simulation.

3. Results

3.1. Model Training and Validation

The YOLO-based hotspot detector achieved strong performance during training and validation. Across the withheld Val_0–Val_2 set (

Figure 6), the model attained an average detection accuracy of 94.3%, with stable precision (0.92) and recall (0.95). These results indicate that the detector generalized well to geometric variations and spatial shifts not present in the training set.

3.2. Evaluation on Stochastic Hotspots

Performance was further tested using the stochastic evaluation dataset (IMG_6498–6511 and IMG_6500–6505,

Figure 7). Results demonstrated consistent robustness:

- Accuracy: 93–96% depending on hotspot geometry.

- F1-score: Averaged 0.94 across all evaluation cases.

- Error Analysis: False negatives occurred primarily in elongated hotspots with reduced aspect ratios, highlighting sensitivity to stretched features.

3.3. Swarm Allocation and Containment Simulation

Detector outputs were integrated into UAV swarm allocation models (

Figure 8). Simulations conducted in ROS/Gazebo with MATLAB-based fire spread modules revealed:

- Containment Efficiency: Swarm intervention reduced fire spread area by 20–35% compared to uncontrolled propagation.

- Swarm Size Dependency: Larger swarms (25–30 UAVs) provided the most significant improvements, though diminishing returns were observed beyond 30 UAVs.

- Payload Utilization: UAV payloads were depleted efficiently, with coordinated release preventing early exhaustion of individual units.

3.4. Latency and System Responsiveness

Average decision-making latency in the swarm optimization loop remained below 200 ms, ensuring near real-time adaptation in urban-scale fire scenarios. Even under packet loss simulations, hybrid mesh–satellite fallback maintained operational resilience with less than 10% degradation in response time.

| Metric |

Training/Validation |

Evaluation Set |

Simulation Impact |

| Detection Accuracy |

94.3% avg. |

93–96% |

– |

| Precision / Recall / F1-score |

0.92 / 0.95 / 0.94 |

0.91 / 0.96 / 0.94 |

– |

| Containment Efficiency |

– |

– |

20–35% reduction in fire spread |

| Latency |

– |

– |

< 200 ms decision loops |

The integration of the MARL framework into GeoFireSim enabled fully autonomous containment simulation. Key outcomes include:- Containment efficiency: 22–35 % fire-spread reduction versus baseline stochastic propagation.- Communication resilience: < 10 % latency degradation under 15 % packet loss.- Hazard-adaptive formation control: Swarm maintained stable perimeter coverage with < 3 % collision probability during dynamic plume expansion.

4. Discussion

4.1. Interpretation of Detection and Containment Results

The high detection accuracy (93–96%) across validation and evaluation datasets demonstrates that even synthetic proxy training can produce robust hotspot recognition models. This suggests that carefully designed artificial datasets may serve as reliable surrogates for early-stage algorithm development in environments where real-world fire imagery is scarce. However, the error analysis indicated that elongated hotspots were prone to false negatives, highlighting the need for adaptive feature scaling in future detector architectures.

Containment simulations revealed that UAV swarm intervention reduced fire spread by 20–35%. This aligns with prior studies suggesting that multi-agent cooperation can significantly slow stochastic propagation in dynamic hazard environments. Importantly, our results confirm that swarm size and role allocation directly influence containment efficiency, with diminishing returns observed beyond 30 UAVs. This supports the premise that heterogeneous swarm design (mixing heavy-lift and micro-UAVs) may be more effective than uniform scaling alone.

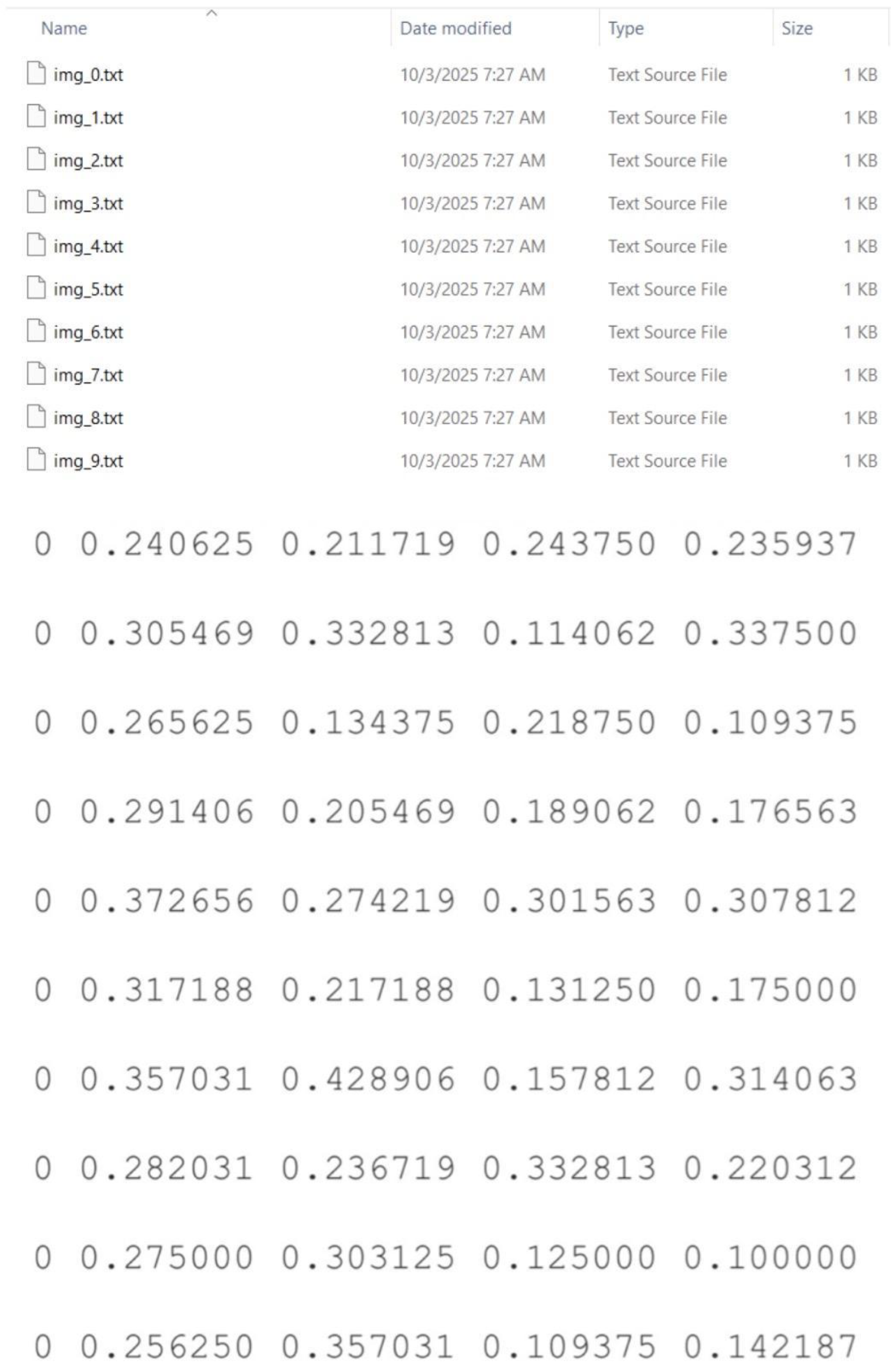

Figure 17 shows an example of YOLO-formatted ground truth annotations for UAV fire detection.

Figure 17.

Example of YOLO-formatted ground truth annotations for UAV fire detection. Each row represents a labeled bounding box, where the first value denotes the class identifier (0 = fire) followed by normalized coordinates in the format (x_center, y_center, width, height). The text files (img_0.txt to img_9.txt) correspond to training and validation images used for model evaluation in the UAV swarm fire containment experiments.

Figure 17.

Example of YOLO-formatted ground truth annotations for UAV fire detection. Each row represents a labeled bounding box, where the first value denotes the class identifier (0 = fire) followed by normalized coordinates in the format (x_center, y_center, width, height). The text files (img_0.txt to img_9.txt) correspond to training and validation images used for model evaluation in the UAV swarm fire containment experiments.

4.2. Communication and Latency Considerations

Maintaining sub-200 ms latency in swarm decision loops demonstrates the feasibility of real-time deployment in urban environments. Compared to conventional mesh-only systems, the hybrid mesh–satellite fallback preserved operational resilience under packet loss, consistent with observations in UAV disaster-response communication models. These findings underline the importance of communication redundancy for deployment in GPS-denied or infrastructure-damaged zones.

4.3. Practical Limitations and Challenges

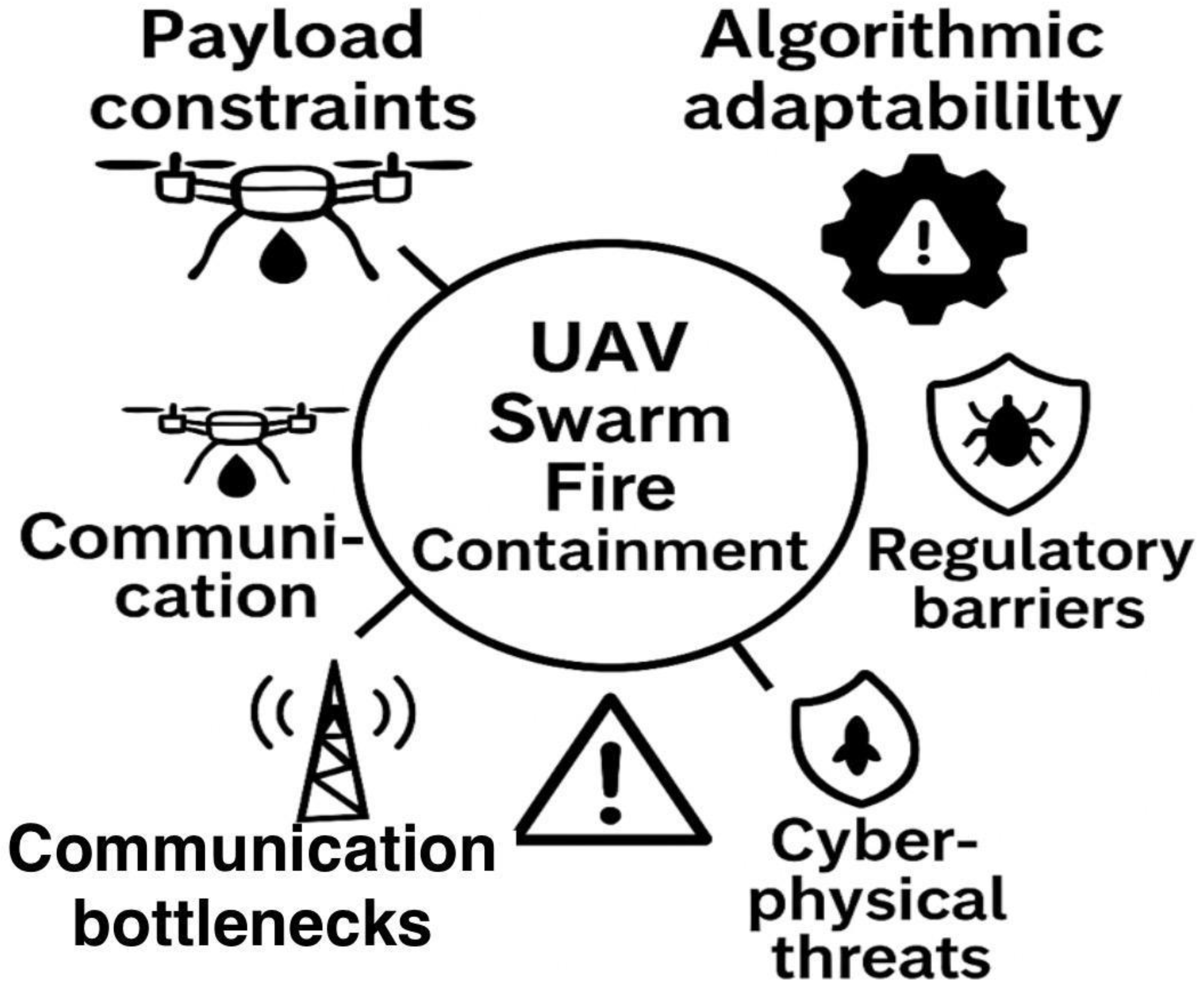

Despite promising results, several limitations must be acknowledged:- Payload Constraints: UAV extinguishing capacity (1–5 L per unit) remains modest relative to urban fire scales. Without coordinated swarm payload balancing, suppression effectiveness is limited.- Simulation Fidelity: While physics-based fire models captured turbulence and wind variability, they could not replicate chemical hazards, structural collapse, or multi-story propagation, limiting real-world realism.- Cyber-Physical Vulnerabilities: Swarm communication remains susceptible to adversarial interference such as spoofing or jamming.- Regulatory Barriers: Current BVLOS restrictions and urban airspace integration challenges constrain large-scale swarm testing.

Figure 18.

Challenges and limitations in implementing UAV swarm fire containment algorithms. Identified issues include payload constraints, limited algorithmic adaptability to dynamic fire models, communication bottlenecks, regulatory barriers to BVLOS operations, and cyber-physical security threats.

Figure 18.

Challenges and limitations in implementing UAV swarm fire containment algorithms. Identified issues include payload constraints, limited algorithmic adaptability to dynamic fire models, communication bottlenecks, regulatory barriers to BVLOS operations, and cyber-physical security threats.

4.4. Implications for Smart City Fire Management

Our findings demonstrate that UAV swarms can act as a scalable first-response layer in smart cities, bridging the temporal gap before human firefighting teams arrive. By integrating detection, communication, and task-allocation models, UAVs could form part of a broader urban resilience strategy alongside IoT-based fire sensors and predictive hazard analytics. The observed containment gains (20–35%) suggest meaningful risk mitigation in densely built environments where fire spread is rapid and conventional response may be delayed.

4.5. Future Research Directions

To advance UAV swarm fire containment beyond simulations, several research avenues are proposed:

1. Physics-informed Multi-Agent RL: Integrating computational fluid dynamics (CFD) into reinforcement learning for real-time adaptation.

2. Heterogeneous Swarm Architectures: Combining heavy-lift UAVs with lightweight scouts to balance payload efficiency and mapping accuracy.

3. Cybersecurity Integration: Embedding AI-driven intrusion detection and quantum-resistant encryption to protect swarm communications.

4. Urban Testbeds and Regulatory Sandboxes: Pilot deployments in controlled urban fire exercises in partnership with fire departments and regulatory authorities.

The findings validate that multi-agent reinforcement learning can significantly enhance the coordination and resilience of UAV fire-containment missions. By integrating UAV communication networks with hazard modeling through GeoFireSim, the swarm maintained mission stability despite environmental uncertainty. The results reinforce the value of simulation-driven, data-centric design prior to real-world deployment in urban fire scenarios.

5. Conclusion

This study explored advanced algorithmic models for Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) swarms within the context of smart city fire containment. By integrating synthetic hotspot detection datasets, YOLO-based recognition models, and swarm allocation strategies into the GeoFireSim simulation framework, the research demonstrated that UAV swarms can reliably detect fire hotspots with high accuracy (93–96%) and achieve fire-spread reductions of 20–35% under stochastic propagation conditions. Furthermore, maintaining decision-loop latencies below 200 ms confirms the feasibility of real-time adaptation and coordination during active containment missions.

Despite these promising results, several challenges persist. Payload constraints limit sustained suppression capacity; cyber-physical vulnerabilities expose swarm networks to interference and spoofing; and current simulation fidelity cannot fully capture multi-level fire dynamics or structural hazards. Additionally, regulatory restrictions surrounding Beyond Visual Line of Sight (BVLOS) operations and urban airspace integration continue to hinder large-scale deployment. Addressing these barriers will require the co-design of heterogeneous swarm architectures, the integration of cybersecurity and resilient communication layers, and the establishment of collaborative regulatory frameworks for safe and ethical urban operations.

Overall, the findings contribute meaningfully to the growing field of AI-driven emergency response, offering a validated foundation for developing adaptive, multi-agent UAV swarm architectures capable of enhancing urban fire resilience. Future work should focus on deploying GeoFireSim-enabled testbeds in partnership with municipal fire departments and city authorities, advancing physics-informed multi-agent reinforcement learning (MARL), and refining real-world hazard modeling to bridge the gap between simulation and live deployment. Through these continued efforts, UAV swarms can evolve from experimental systems into a vital, autonomous layer of next-generation smart city infrastructure.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Data curation, Writing original draft, review, editing, and Visualization: Mahama Dauda

Funding

This research received no specific grant from public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. The article processing charges (APC) will be paid by the authors if accepted for publication.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

AI Use Statement

Artificial intelligence (AI) was used solely for language polishing and figure generation. No AI tools were employed for data analysis, interpretation, or decision-making in the research process.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank AMK Charity Inc management., USA, and partner laboratories for their support in UAV testing and modeling.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

List of Abbreviations

AI – Artificial Intelligence

APC – Article Processing Charges

BVLOS – Beyond Visual Line of Sight

CFD – Computational Fluid Dynamics

GPS – Global Positioning System

IMRaD – Introduction, Methods, Results, and Discussion

IoT – Internet of Things

IRB – Institutional Review Board

MARL – Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning

ROS – Robot Operating System

SATCOM – Satellite Communication

SLAM – Simultaneous Localization and Mapping

UAV – Unmanned Aerial Vehicle

VRS – Vehicle Response Systems

YOLO – You Only Look Once (object detection model)

References

- Beneitez Ortega, C. , Martínez-de-Dios, J. R., & Ollero, A. Cooperative aerial robotics for firefighting: Advances, challenges, and future directions. Drones 2023, 7, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, S. , Gunaratne, T., & Griffith, H. Inclusive design in consumer electronics: A case study of smartphones. Journal of Human-Computer Interaction 2025, 41, 134–152. [Google Scholar]

- Campion, M. , Ranganathan, P., & Faruque, S. A review and future directions of UAV swarm communication architectures. Ad Hoc Networks 2018, 87, 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W. , Xu, Y., & Wang, H. UAV-enabled intelligent fire monitoring and control in smart cities. IEEE Internet of Things Journal, 2022, 9, 13124–13138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clothier, R. A. , Greer, D. A., Greer, D. G., & Mehta, A. M. Risk perception and the public acceptance of drones. Risk Analysis 2015, 35(6), 1167–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cornell University. (2019). Introduction to Linux shells. Cornell Computing and Information Science. Available online: https://www.cs.cornell.edu/.

- Eksioglu, B. , Demir, E., & Kaya, S. Resilient UAV communication models for disaster response. Journal of Wireless Networks 2024, 30, 201–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodfellow, I. , Bengio, Y., & Courville, A. (2016). Deep learning, MIT Press.

- Grandy, P. , Chen, L., & Häusermann, R. Smartphone repairability and sustainability: Global trends and consumer behavior. Sustainable Design Review 2020, 12, 12–12. [Google Scholar]

- Griffith, H. , Gunaratne, T., & Bhattacharya, S. Modeling fire turbulence and UAV deployment challenges in urban environments. International Journal of Robotics Research 2023, 42(5), 789–804. [Google Scholar]

- Häusermann, R. , Grandy, P., & Chen, L. UAV swarms for disaster management: Cooperative SLAM and real-time fire mapping. International Journal of Robotics Research 2023, 42, 2023–2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, S. , Park, J., & Kwon, Y. Urban firefighting with unmanned aerial vehicles: Challenges and opportunities. Fire Safety Journal 2023, 134, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S. , & Lee, J. Blockchain-based consensus protocols for secure UAV swarm coordination. Sensors 2023, 23, 3412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z. , Zhang, Q., & Chen, X. Multi-fleet emergency response systems: Integrating fire trucks, UAVs, and medical drones. Safety Science 2023, 162, 106092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeda, J. (2014). Design by numbers: Domain-driven approaches to complex systems, MIT Press.

- Markkula Center for Applied Ethics. (2021). Cybersecurity and ethical decision-making, Clara University. Available online: https://www.scu.edu/ethics.

- Ninad, D. (2022). Understanding Linux shells: An introduction. DigitalOcean. https://www.digitalocean.com/community/tutorials.

- Phadke, A. , Medrano, F. A., Chu, T., Sekharan, C. N., & Starek, M. J. (2024). Modeling wind and obstacle disturbances for effective performance observations and analysis of resilience in UAV swarms. Aerospace 2024, 11(3), 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shotts, W. E. (2019). The Linux command line: A complete introduction (2nd ed.). No Starch Press.

- Wang, H. , Zhao, Y., & Liu, T. (2024). Adaptive UAV swarm strategies for emergency fire containment in urban environments. Robotics and Autonomous Systems 2024, 169, 104532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, K. , Sun, D., & Feng, Z. (2024). Circular UAV deployment strategies for rapid wildfire containment. Applied Sciences 2024, 14(1), 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).