I. Introduction

Real-time earth observation has become critical for protecting fragile ecosystems and vulnerable communities that are exposed to toxic, unauthorized open-pit mining practices. In Ghana, small-scale gold mining (SGM), locally referred to as “galamsey,” poses significant environmental and public safety threats, despite offering limited economic benefits [

5]. Note that since the late 1980s, illegal artisanal mining in Ghana has been estimated to generate hundreds of millions of dollars in revenue, contributing to local employment and market activity. However, unregulated operations accelerate river siltation, increase toxic-metal contamination, destroy the ecosystem, strip vegetation, destabilize slopes, and cause frequent pit collapses. Recent studies document recurring fatalities, including the death of eight Ghana government officials on August 6, 2025, and extensive environmental degradation linked to galamsey in the past decade [

16].

Unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) offer persistent and adaptive sensing capabilities across challenging terrain, making them valuable tools for mitigating risks through aerial surveillance and rapid response. However, most current deployments remain reactive and lack resilience. Perception models often assume clear visibility, while decision thresholds are rarely calibrated to account for environmental complexities. Moreover, communications frequently fail in precisely the locations where coordination is most critical, such as dense forest canopies, deep gorges, or radio frequency (RF)-congested settlements. These limitations exacerbate environmental impacts, as open-pit mining poses significant eco-environmental challenges that demand dynamic monitoring and proactive mitigation strategies [

49].

Addressing these gaps is vital for enabling real-time risk mitigation against unauthorized mining activities. Despite the inherent sensing advantages of UAVs, their current applications often remain reactive due to uncalibrated perception systems and fragile communication networks in complex terrains. Recent research highlights the growing optimization of UAV surveillance strategies to support diverse environmental conditions and mission objectives [

14,

23].

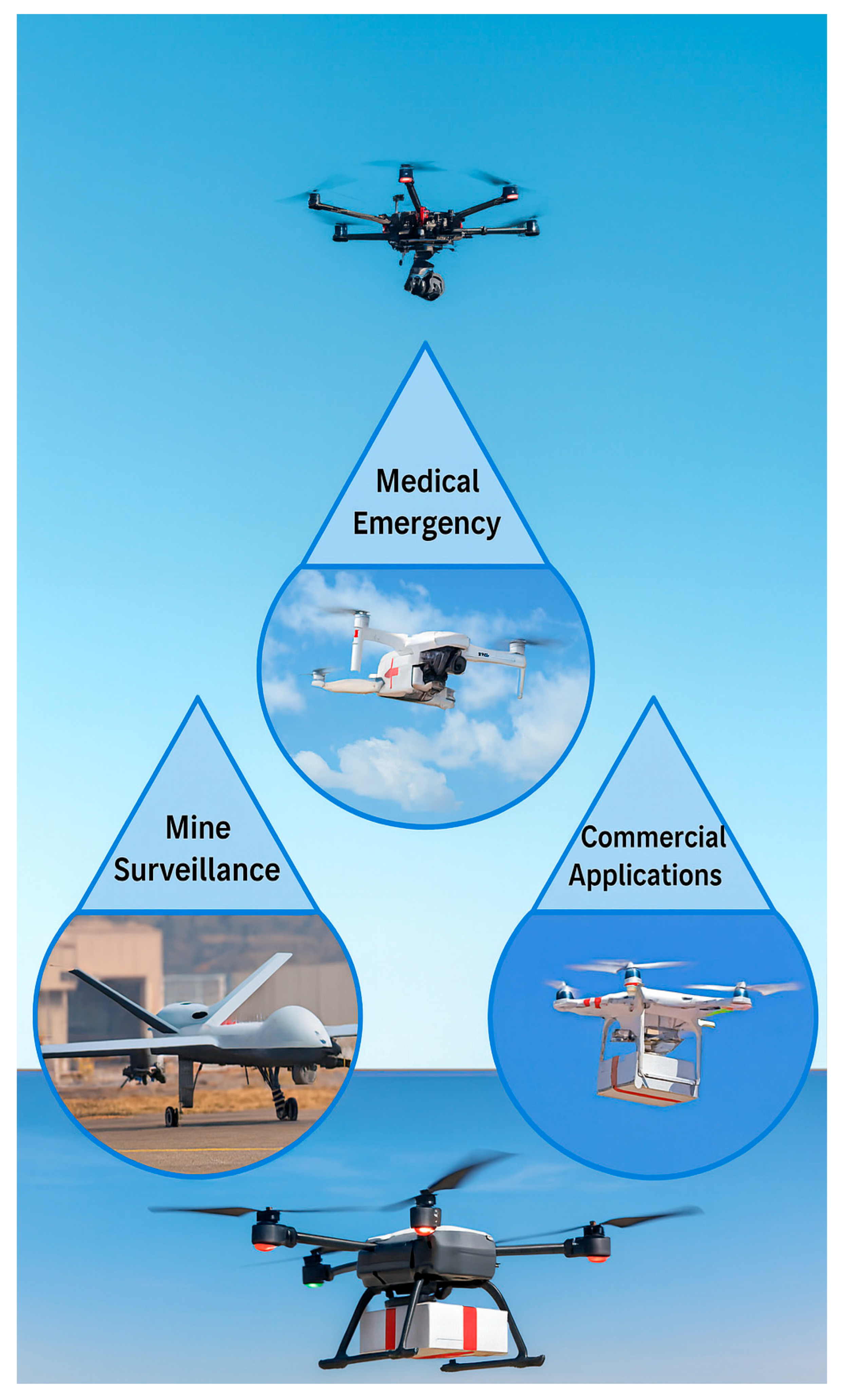

Figure 1 Representative UAV applications across domains. UAVs support medical emergency response (top), mine surveillance for safety and environmental monitoring (left), and commercial delivery services (right), demonstrating the technology’s versatility and growing societal impact.

The relevance of UAV technologies is further underscored by their projected market growth.

Table 1 compares historical and projected compound annual growth rates (CAGR) for UAVs and autonomous vehicles (AVs) between 2020 and 2035. UAV revenues are projected to increase from USD 20.65 billion in 2020 to USD 76.75 billion by 2035, while AV markets exhibit even sharper growth trajectories, with long-term extrapolations surpassing USD 111 billion by 2035 (Drone Industry Insights [DII], 2023–2024; Fortune Business Insights, 2022–2024; McKinsey & Company, 2023). Benchmarks from McKinsey further forecast autonomous driving revenue pools of USD 300–400 billion by 2035, which remain below the more aggressive projections of Fortune Business Insights.

(Drone Industry Insights, 2023/2024; Fortune Business Insights, 2022/2024; McKinsey & Company, 2023). UAV data compiled by the authors. CAGR = compound annual growth rate; UAV = unmanned aerial vehicle; AV = autonomous vehicle. Showcasing in

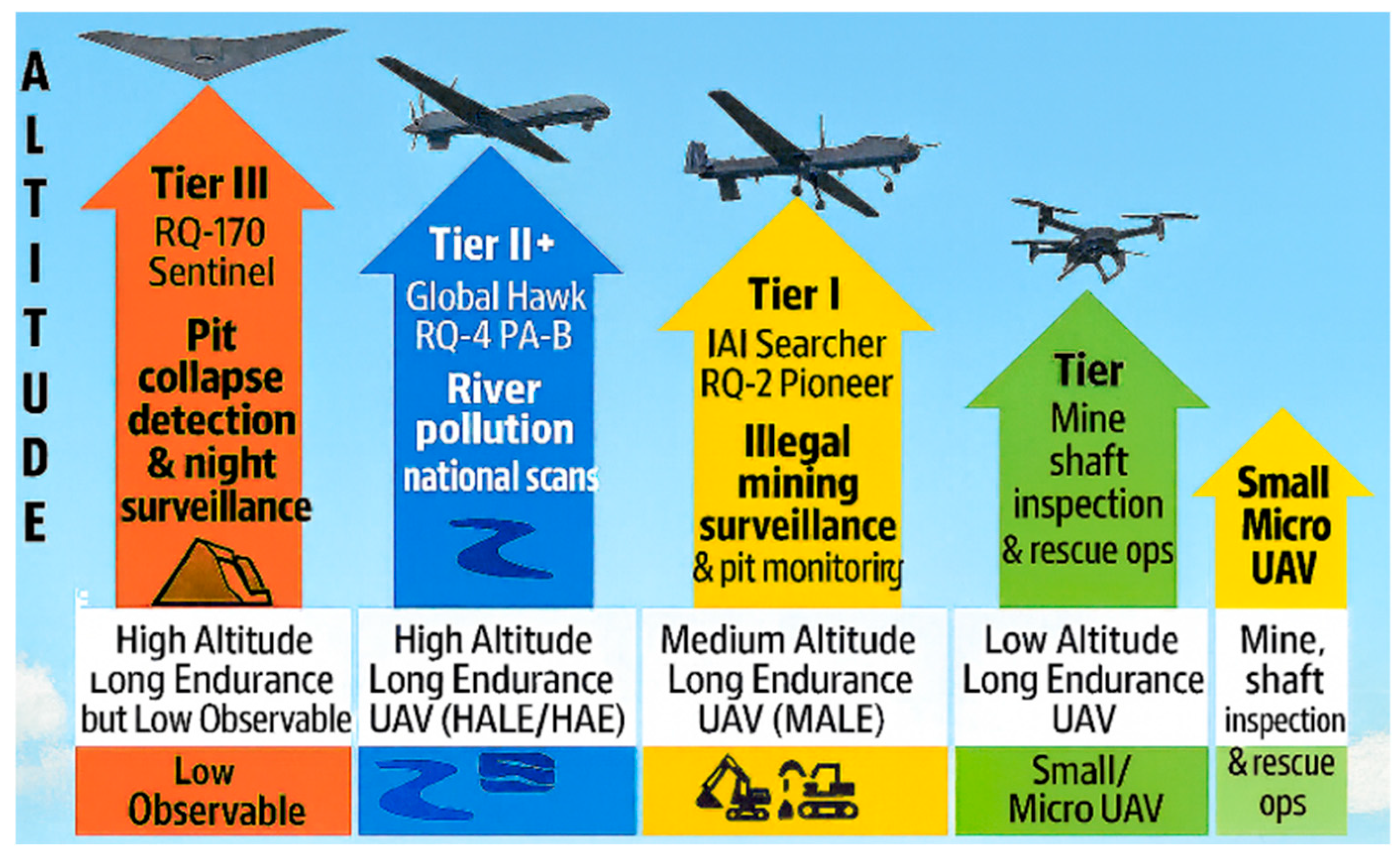

Figure 2 are Mining-Aligned UAVs of Manufacturers and Features by Altitude.

Despite advances, UAV-based galamsey monitoring remains limited by two technical bottlenecks:

Perception–Decision Reliability: Current models detect mining artifacts but lack calibrated severity scoring, leading to brittle or untrustworthy alerts.

Communication Resilience: Alerts often fail to propagate when LTE coverage is poor and mesh links are intermittent, delaying response and reducing trust.

These weaknesses result in uneven or delayed interventions, undermining the promise of UAV-based crisis monitoring.

This study addresses these limitations by proposing a proactive, learning-enabled UAV network termed “Galamsey-911” that integrates perception calibration, SLA-aware communications, and hotspot forecasting. The following research questions (RQs) guide the work:

RQ1: Can a calibrated multi-modal Severity Index yield actionable thresholds?H1: AUROC ≥ 0.90; ECE ≤ 0.07.

RQ2: Does SLA-aware, multi-path dispatch reduce time-to-intervention?H2: p95 alert latency ≤ 30 s with ≥ 99% delivery.

RQ3: Do 24h, 48h, 72 h hotspot forecasts improve patrol efficiency?H3: ≥ 30% lead-time gain; higher coverage per battery-hour.

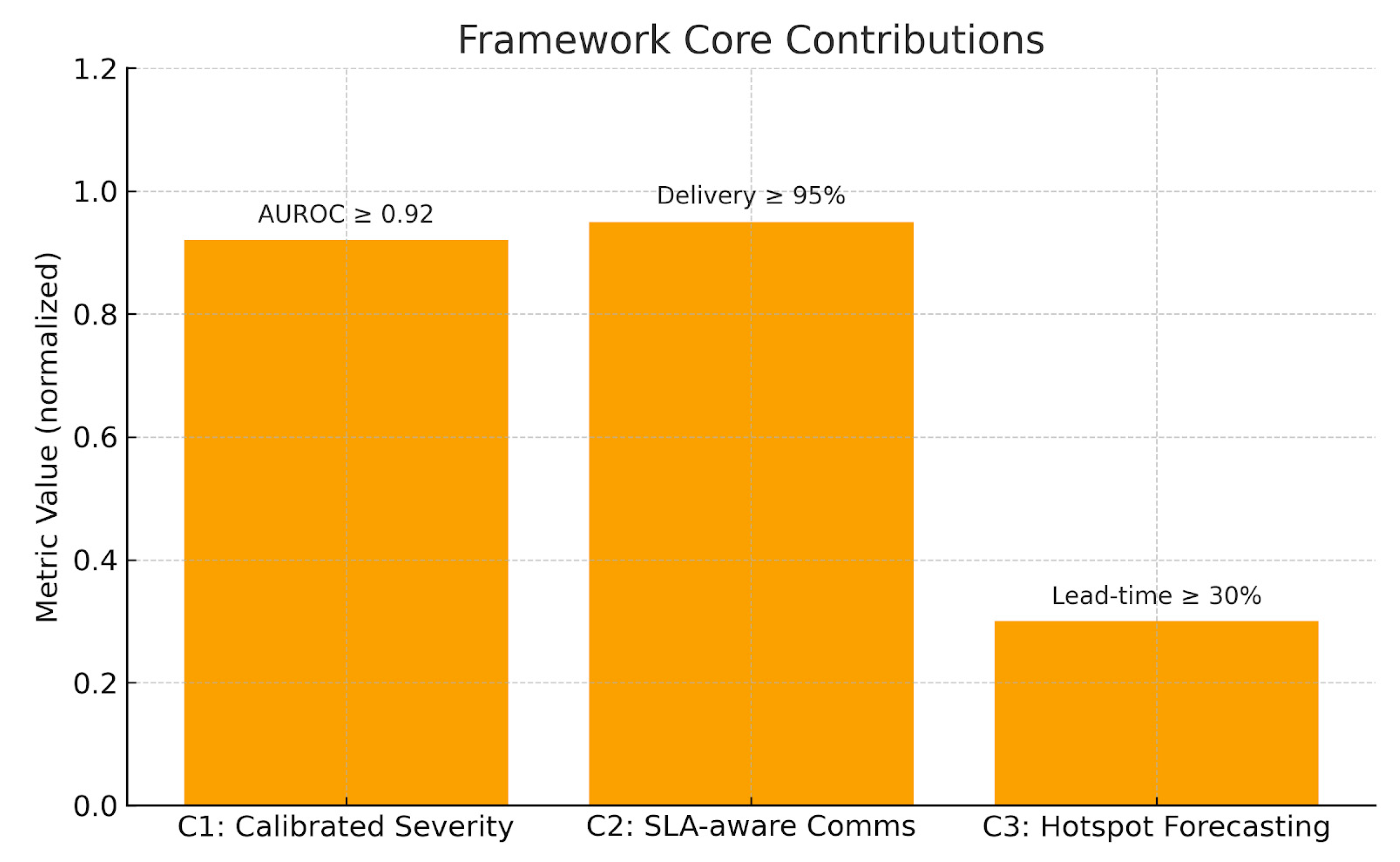

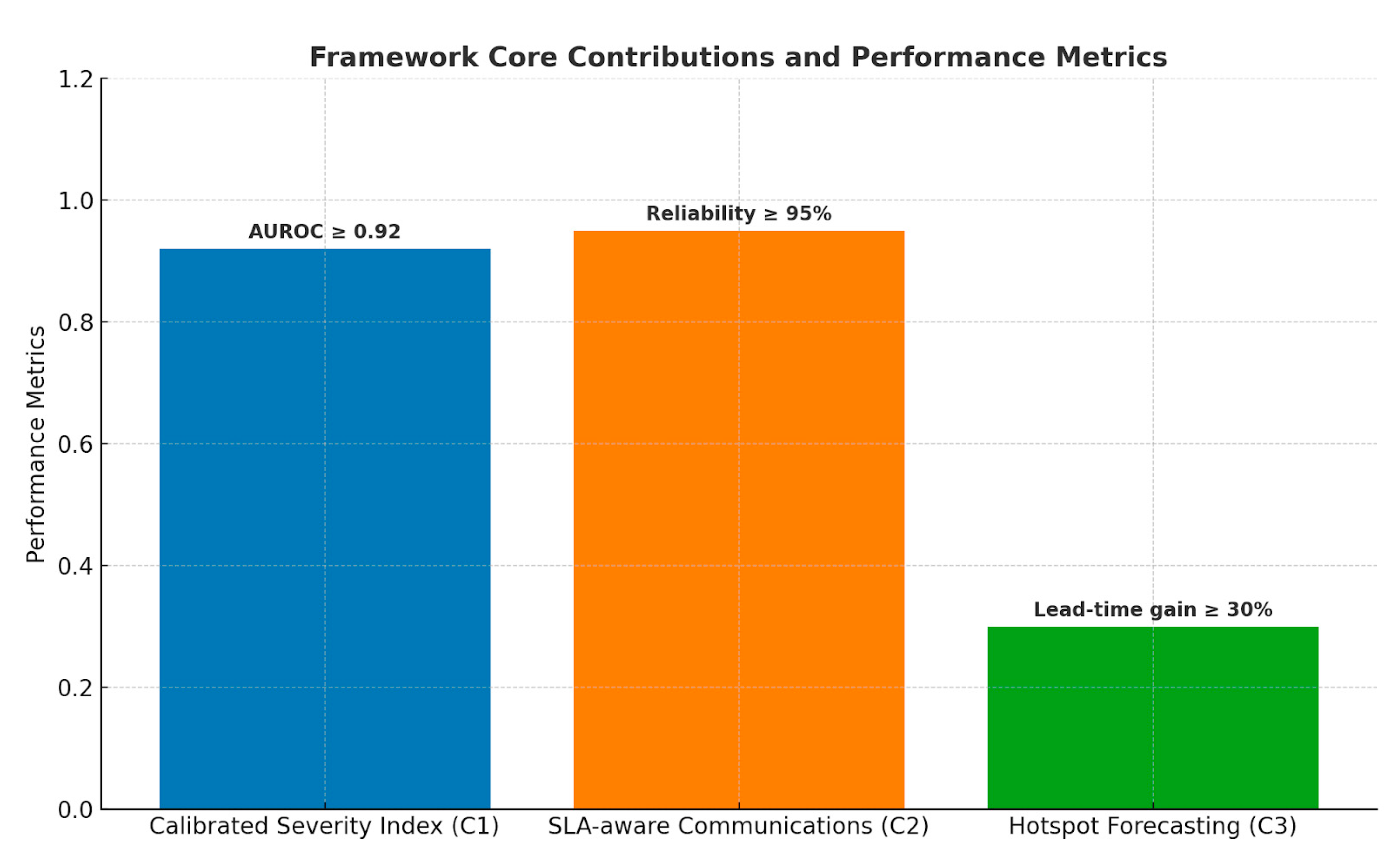

The primary contributions of this paper are:

C1 — Calibrated Severity Index: A multi-modal fusion framework combining vision, acoustic/RF, and GIS priors, enhanced with post-hoc calibration and interpretability attributions.

C2 — Galamsey-911 Dispatcher: An SLA-aware dispatcher with QoS-backed timers, acknowledgments, and LTE→Mesh→SATCOM failover, ensuring ≥ 95% delivery reliability.

C3 — Hotspot Forecasting and Routing: Deployment of ConvLSTM and spatiotemporal GNNs to generate 24h, 48h, & 72h risk maps, integrated into energy and link-aware patrol planning.

Together, these components form the first end-to-end, auditable UAV surveillance system capable of shifting galamsey operations monitoring from reactive detection to proactive prevention.

The study focuses on simulation-based corridor trials in representative ASGM regions. Assumptions include lawful airspace access and safe flight envelopes, with LTE coverage along partial corridors and SATCOM fallback elsewhere. Real-world deployments and kinetic interventions are excluded. Ethical safeguards include geofencing, standoff distances, anonymization, encryption, and human-in-the-loop oversight for community alerts, in compliance with Ghana Civil Aviation Authority (GCAA) rules and the Ghana Data Protection Act.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. Section II reviews related work and identifies gaps. Section III presents the system architecture and design. Section IV details the Severity Index and communication stack. Section V outlines hotspot forecasting and patrol planning. Section VI evaluates system performance. Section VII discusses findings, limitations, and policy implications. Section VIII concludes and outlines future work.

II. Literature Review

Unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) have become an important tool in environmental monitoring because of their ability to operate flexibly in difficult terrains and to integrate modern computer vision methods. Deep learning–based object detection frameworks such as Mask R-CNN [

18] and the YOLO family of models [

27,

36] established performance standards in real-time image recognition and have since inspired adaptations for safety inspection, ecological examples [

16], surveys, and mining detection. To demonstrate the effectiveness of Sentinel-2 imagery with convolutional networks in detecting small-scale mining in Ghana, while [

15] applied Sentinel-1 time-series analysis for land-use change detection. Similarly, [

34] illustrates how UAV-based land-use monitoring in the Ankobra basin can reveal mining-related disturbances. Collectively, these studies confirm that UAV platforms coupled with vision algorithms can reliably detect artisanal and small-scale gold mining (ASGM) activities, even in heterogeneous landscapes.

Despite these successes, monitoring challenges remain severe in Ghana’s galamsey corridors. Unlike industrial-scale open-pit operations, which are visible in satellite or aerial images [

33], artisanal mining often occurs in concealed sites beneath dense vegetation and across rugged terrain. [

7] emphasize that these conditions reduce detection accuracy, allowing small pits to escape both satellite- and UAV-based monitoring. Compounding the problem, communication infrastructure in rural ASGM zones is unreliable, with LTE coverage often patchy and mesh networks susceptible to interference. As a result, models that perform well in laboratory settings or in open mining sites frequently degrade in operational field conditions. This gap highlights the difficulty of sustaining actionable detection and response capabilities when both perception and communication are compromised.

Leveraging UAVs for patrol inspection, they play a critical role in monitoring slope stability and detecting early signs of potential hazards in open-pit mines [

41]. Similarly, integrating safety technologies such as advanced sensors within tailings storage facilities represents a pivotal step toward smart mine safety systems [

6].

Detection provides situational awareness but does not guarantee timely intervention. Forecasting models extend UAV applications by predicting where and when hazards are likely to occur, enabling scarce resources such as UAV patrol hours to be allocated more efficiently. Spatiotemporal learning methods such as convolutional LSTM networks [

40] and graph-based deep learning frameworks [

46] have been validated in domains such as rainfall estimation, transportation, and ecological risk modeling. Their adaptation to illegal mining hotspots has shown early promise [

4].

Complementary approaches leverage geographic information systems (GIS) combined with multicriteria decision analysis (MCDA) to incorporate terrain, hydrology, and settlement proximity into risk assessments [

29]. Integrating these models allows for predictive risk maps that guide UAV deployments toward areas most likely to be affected, shifting the paradigm from reactive detection toward anticipatory hazard management proactively.

A recurring challenge with deep learning–based forecasting is overconfidence: models often assign high probabilities to uncertain predictions, which reduces trustworthiness in safety-critical operations [

17]. For UAV-based surveillance, this can result in costly false alarms or misallocated responses. Approaches such as Bayesian deep learning [

22] and post-hoc calibration strategies like temperature scaling [

8] help align predicted probabilities with actual empirical likelihoods. In the context of galamsey monitoring, the use of calibrated severity indices ensures that only alerts meeting well-validated thresholds trigger dispatch actions, thereby balancing responsiveness with operational efficiency.

Rural ASGM corridors lack dependable infrastructure, so UAV surveillance must rely on resilient, adaptive communications [

9]. Early approaches extended connectivity in intermittently connected regions using delay-tolerant networking (DTN) and long-distance Wi-Fi [

25,

54]. Within UAV contexts, cellular improvements and opportunistic mesh broadened range and continuity [

1,

12,

26], while hybrid BVLOS operations and software-defined satellite overlays added redundancy for outages. Complementing these link-layer advances, multi-path, swarm-oriented planning improves route diversity and network robustness [

28], and deep reinforcement learning helps collaborative UAVs maintain reliable contact under dynamic conditions [

45].

Empirical studies of 5G-enabled UAVs show meaningful latency reductions, yet performance remains uneven in obstructed terrain [

2]. FANET surveys repeatedly stress the need for fast failover and SLA-aware design; however, few evaluations consider African rural environments dominated by canopy, interference, and irregular power (e.g., generator) supply. This gap motivates our Galamsey-911 architecture, which fuses multi-path LTE→Mesh→SATCOM with SLA timers and swarm-aware planning to sustain sub-30-second alert delivery in canopy-dense corridors.

Although the above strands of research perception, forecasting, and communications each show strong progress individually, most UAV deployments remain siloed. Vision systems are often disconnected from predictive models, and communications protocols are evaluated independently of perception pipelines. The literature lacks an integrated, end-to-end system that links calibrated detection with predictive foresight and communication reliability. This fragmentation results in UAV deployments that can detect incidents but cannot guarantee timely or trustworthy coordination of responses.

Addressing this integration gap motivates the present study. Building on prior advances in vision, forecasting, and communications, this work proposes the “Galamsey-911” architecture, which unifies calibrated perception models, predictive hotspot mapping, and multi-layer LTE–Mesh–SATCOM communications into a single operational framework. Unlike earlier approaches, which typically remain reactive, this system is designed to transition UAVs from passive monitoring to proactive, cooperative responders suited for the complex conditions of Ghana’s artisanal mining regions [

8].

Although the above strands of research, perception, forecasting, and communications each show strong progress individually, most UAV deployments remain siloed. Studies on collaborative path planning [

28] and reinforcement learning–based coordination [

45], UAV surveillance [

14] demonstrate important steps toward cooperation but do not yet integrate forecasting and SLA-aware resilience. Addressing this integration gap motivates the present study.

III. Materials, Methods and Methodology

This section outlines the design and validation of the Proactive ML-enabled Predictive UAV Network, structured around three core contributions: C1 (Calibrated Severity Index), C2 (SLA-aware Communications), and C3 (Hotspot Forecasting).

Datasets for these three components were synthetically generated to simulate real-world operating conditions, including varying environmental hazards, network disruptions, and illegal mining activity patterns. The data were partitioned into 60% for model training, 20% for testing, and 20% for validation, following standard machine learning best practices to ensure robust and unbiased performance evaluation.

Python served as the primary programming language for data generation, model development, and automation of preprocessing tasks. Libraries such as NumPy and Pandas were used for data cleaning, transformation, and feature engineering, while Matplotlib was employed to visualize trends, performance metrics, and hotspot forecasts through plots and heatmaps. R was utilized for advanced statistical analysis, including correlation studies and validation of modeling assumptions, ensuring the integrity and reliability of results.

For C1 (Calibrated Severity Index), synthetic datasets included labeled environmental imagery and sensor readings, which were processed and calibrated using Python-based machine learning models. Post-hoc temperature scaling was applied to fine-tune decision thresholds and improve model reliability.

For C2 (SLA-aware Communications), network traffic logs and simulated failure events were generated to evaluate communication protocols under diverse connectivity scenarios, including LTE, multi-hop mesh, and SATCOM failover. Python scripts simulated real-time packet transmissions, while R was used to analyze statistical measures such as p95 latency and packet delivery ratios.

For C3 (Hotspot Forecasting), spatiotemporal data representing illegal mining activity were generated and used to train ConvLSTM and Graph Neural Network (GNN) models. These models produced predictive hotspot maps for 24-, 48-, and 72-hour intervals, with outputs visualized using Matplotlib for model evaluation and decision-making.

This integrated data processing and toolchain workflow ensured the framework was scalable, accurate, and reliable, providing a solid foundation for proactive UAV-based environmental monitoring and real-time risk mitigation.

Figure 3.

Framework core contributions (C1–C3).

Figure 3.

Framework core contributions (C1–C3).

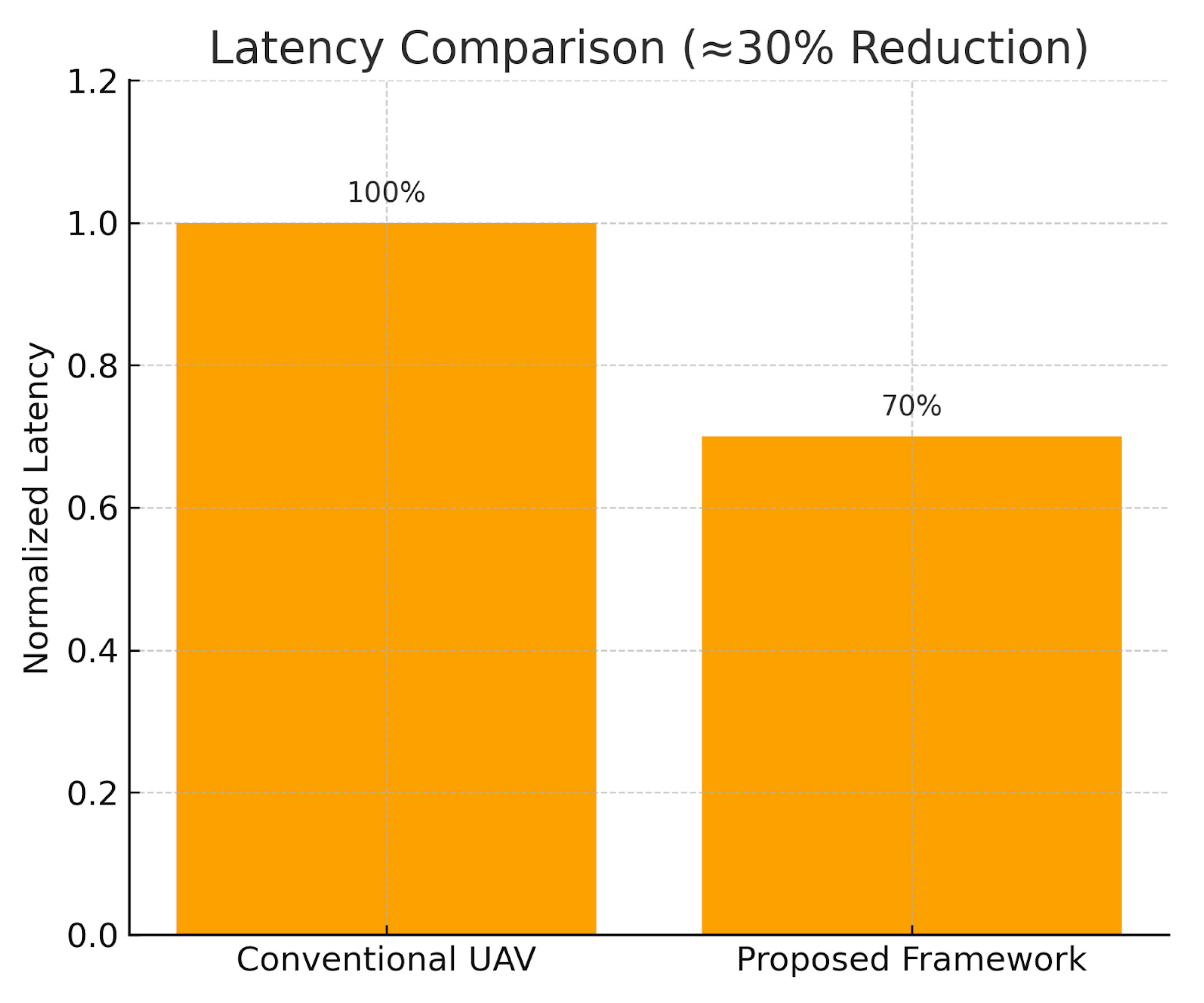

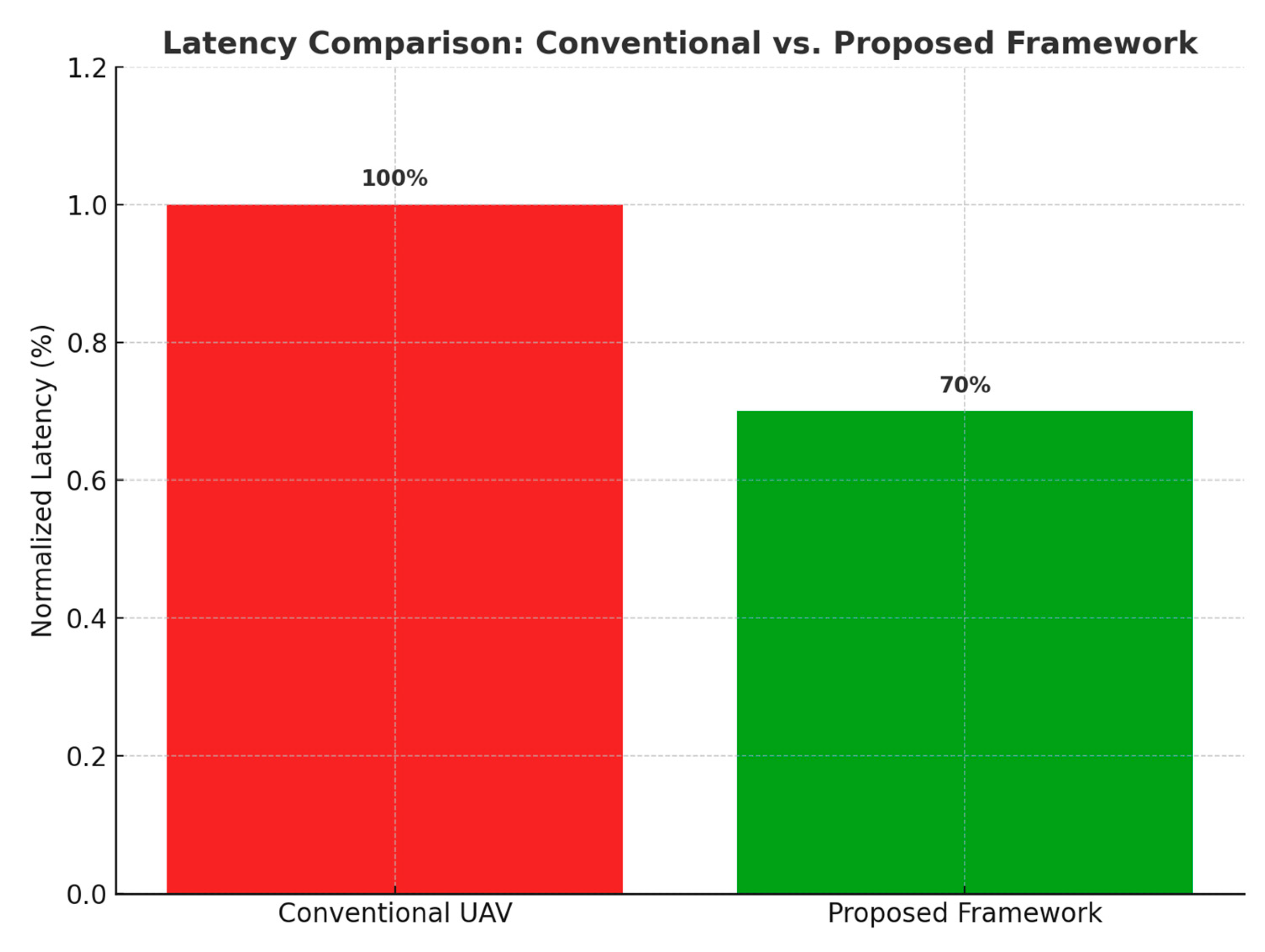

Figure 4.

Latency comparison: baseline vs proposed (~30% reduction).

Figure 4.

Latency comparison: baseline vs proposed (~30% reduction).

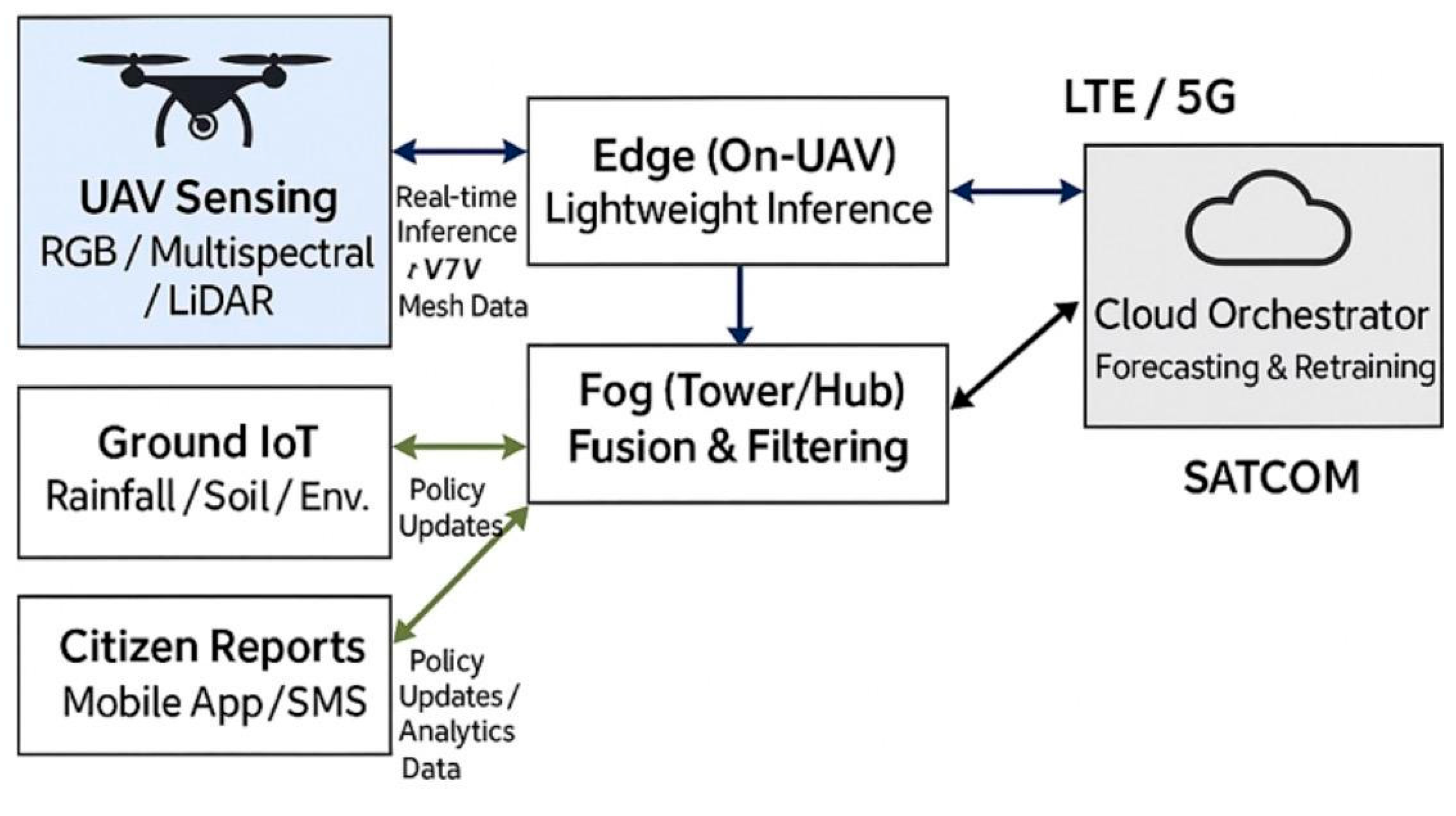

The system integrates aerial UAV sensing, IoT ground devices, and citizen reporting into a multi-layer architecture for resilient and proactive galamsey monitoring. UAVs capture RGB/multispectral imagery with optional LiDAR, while IoT sensors continuously monitor environmental proxies such as rainfall and soil stability.

Edge devices mounted on UAVs perform low-latency inference, fog nodes fuse UAV data streams with IoT inputs, and a cloud orchestrator manages forecasting, retraining, and coordination across the network.

To ensure communication resilience under canopy occlusion or RF congestion, vehicle-to-vehicle (V2V) mesh networking supports real-time coordination between UAVs, while LTE/5G uplinks and SATCOM serve as fallback mechanisms [

8,

44].

Algorithm 1: Galamsey-911 Proactive UAV Surveillance (C1 + C2 + C3) formalizes the operational workflow, integrating:

C1: Calibrated Severity Scoring

C2: SLA-aware communication with multi-tier failover

C3: Hotspot forecasting with patrol planning

This unified pipeline enables proactive detection and rapid response to illegal mining activities. Data flows from UAV sensors and IoT devices through the fog layer to the cloud, where predictive models are updated and patrol routes optimized.

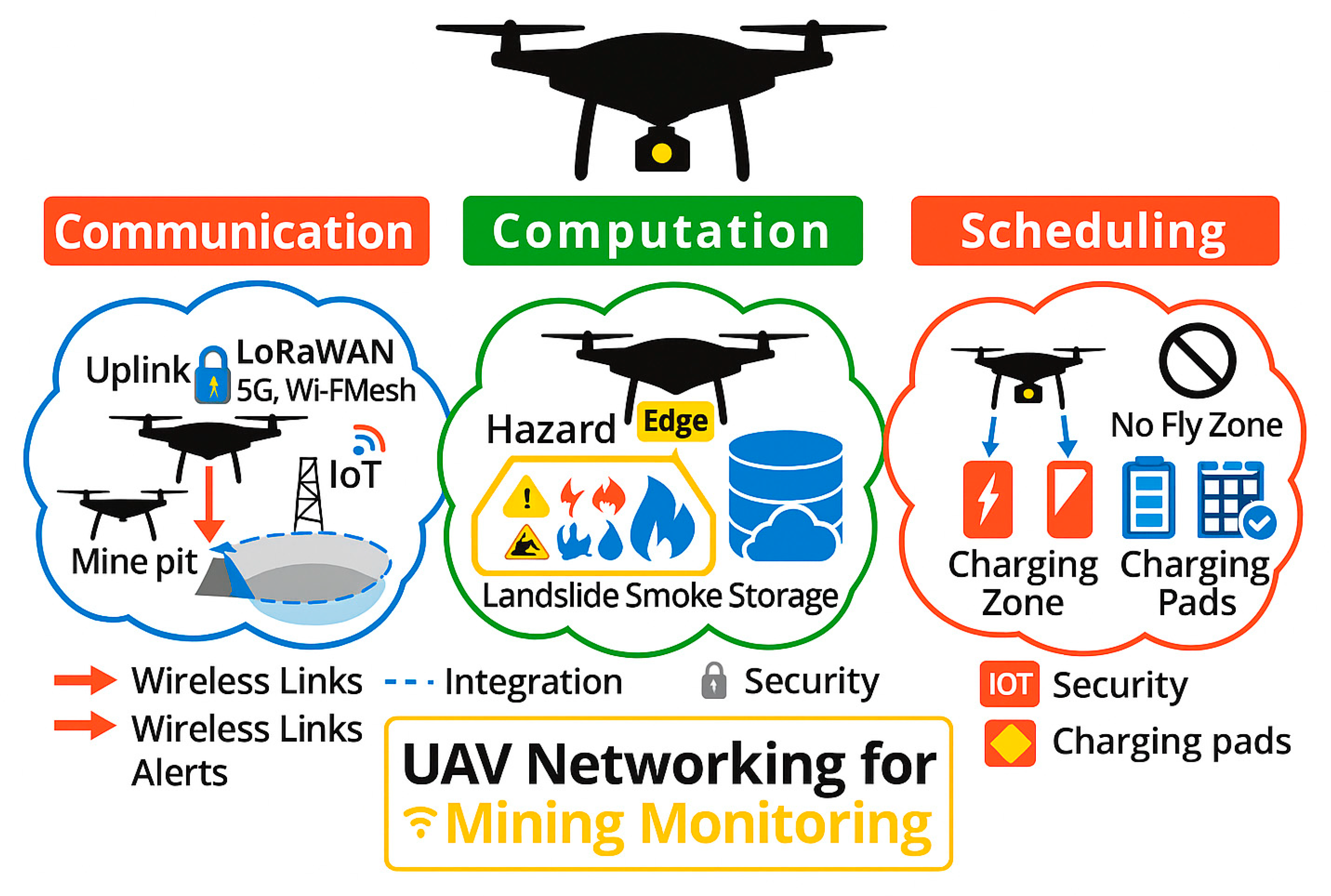

Communication–Computation–Scheduling Diagram Overview

This figure illustrates the integrated multi-layer system architecture for UAV-based galamsey monitoring.

Communication Layer: UAVs and IoT sensors transmit real-time data using secure uplinks (LoRaWAN, 5G, Wi-Fi mesh), with alerts sent to monitoring centers.

Computation Layer: Edge and fog devices process hazard detection tasks, including landslides, smoke, and other environmental hazards.

Scheduling Layer: Charging zones, pads, and no-fly zones are incorporated to optimize UAV flight schedules and mission planning.

The figure highlights wireless links, security protocols, and integration pathways, showing how data flows seamlessly between the field and centralized cloud resources.

Figure 5.

Communication–Computation–Scheduling overview.

Figure 5.

Communication–Computation–Scheduling overview.

Algorithm 1 Galamsey-911: Proactive UAV Surveillance (C1 + C2 + C3)

| Input: AirSim scenes , IoT streams I, GIS layers G, corridor graph

|

| Output: Timely, trustworthy alerts and patrol plans |

| 1. Set up components: |

| 1A. Models → f_det, f_seg, f_chg |

| 1B. Calibration params θ_cal = {τ, β}, ensemble size N |

| 1C. Comms stack → [LTE (primary), Mesh (secondary), SATCOM (tertiary)] |

| 1D. SLA timers {T_ack, T_failover}, QoS topics

|

| 1E. Forecast models → {F_clstm, F_gnn, F_tft} |

| 2. For each mission window t = 1…T loop |

| 2A. Sense & Fuse: |

| 2A.i x_t ← UAV frame; u_t ← IoT; g_t ← GIS |

| 2A.ii y_det ← f_det(x_t); m_seg ← f_seg(x_t); d_chg ← f_chg(x_t, x_{t-Δ}) |

| 2A.iii z_ctx ← features(NDVI(m_seg), slope(g_t), hydro(g_t), proximity(g_t)) |

| 2B. Decision branch — detection present? |

| 2B.YES → go to Step 3 (C1) |

| 2B.NO → log(‘no-target’) → jump to Step 6 (forecast trigger) |

| 3. C1: Calibrated Severity (Alg. 2) |

| 3A. s_raw ← fuse(y_det, d_chg, z_ctx) |

| 3B. s_cal ← CalibratedSeverity(s_raw, θ_cal, N) |

| 3C. Threshold branch: |

| 3C.HIGH if s_cal ≥ θ_high → level ← HIGH |

| 3C.MEDIUM else if s_cal ≥ θ_med → level ← MED |

| 3C.MONITOR else → level ← MONITOR |

| 4. C2: Dispatch with SLA + Failover (Alg. 3) |

| 4A. pkt ← {geo, s_cal, level, context=z_ctx, tstamp=t} |

| 4B. Link branch: |

| 4B.1 LTE available & ACK within T_ack → path ← LTE, ack ← ACK |

| 4B.2 LTE fails → try Mesh; ACK within T_ack → path ← Mesh |

| 4B.3 Mesh fails → escalate to SATCOM; ACK within T_ack → path ← SATCOM |

| 4B.4 All fail within T_failover → ack ← NACK; queue DTN buffer |

| 5. Logging & Active Learning |

| 5A. Append(𝓓_det, {x_t, y_det, s_raw, s_cal}); Append(𝓓_net, {path, ack, latency}) |

| 5B. Uncertainty branch → if Uncertain(y_det) or Disputed(s_cal) → QueueForAnnotation(x_t) |

| 6. C3: Forecasting trigger |

| 6A. Periodic → if t mod H == 0 → run Alg. 4 |

| 6B. Event-driven → if level ∈ {HIGH, MED} → run Alg. 4 |

| 6C. After Alg. 4 → Broadcast(plan) on topics with retain+TTL |

| end loop |

The system integrates aerial UAV sensing, IoT ground devices, and citizen reporting into a multi-layer architecture. UAVs capture RGB/multispectral imagery with optional LiDAR, while IoT sensors monitor rainfall/soil proxies. Edge devices on UAVs provide low-latency inference, fog nodes fuse UAV with IoT streams, and the cloud orchestrator performs forecasting and retraining. Vehicle-to-vehicle (V2V) mesh networking ensures resilience under canopy or RF congestion [

8,

44].

Figure 6.

depicts a System Architecture of the Galamsey UAV Network. Multi-layer sensing and computation stack integrating UAV imagery, IoT ground devices, citizen reports, fog preprocessing, and cloud forecasting.

Figure 6.

depicts a System Architecture of the Galamsey UAV Network. Multi-layer sensing and computation stack integrating UAV imagery, IoT ground devices, citizen reports, fog preprocessing, and cloud forecasting.

Algorithm 1 Galamsey-911: Proactive UAV Surveillance (C1 + C2 + C3)

To formalize this process,

Algorithm 1 outlines the Galamsey-911 proactive UAV surveillance pipeline. It integrates calibrated severity scoring (C1), SLA-aware communication with failover (C2), and hotspot forecasting with patrol planning (C3) into a unified operational loop.

| Input: AirSim scenes , IoT streams I, GIS layers G, corridor graph

|

| Output: Timely, trustworthy alerts and patrol plans |

| 1. Set up components: |

| 1A. Models → f_det, f_seg, f_chg |

| 1B. Calibration params θ_cal = {τ, β}, ensemble size N |

| 1C. Comms stack → [LTE (primary), Mesh (secondary), SATCOM (tertiary)] |

| 1D. SLA timers {T_ack, T_failover}, QoS topics

|

| 1E. Forecast models → {F_clstm, F_gnn, F_tft} |

| 2. For each mission window t = 1…T loop |

| 2A. Sense & Fuse: |

| 2A.i x_t ← UAV frame; u_t ← IoT; g_t ← GIS |

| 2A.ii y_det ← f_det(x_t); m_seg ← f_seg(x_t); d_chg ← f_chg(x_t, x_{t-Δ}) |

| 2A.iii z_ctx ← features(NDVI(m_seg), slope(g_t), hydro(g_t), proximity(g_t)) |

| 2B. Decision branch — detection present? |

| 2B.YES → go to Step 3 (C1) |

| 2B.NO → log(‘no-target’) → jump to Step 6 (forecast trigger) |

| 3. C1: Calibrated Severity (Alg. 2) |

| 3A. s_raw ← fuse(y_det, d_chg, z_ctx) |

| 3B. s_cal ← CalibratedSeverity(s_raw, θ_cal, N) |

| 3C. Threshold branch: |

| 3C.HIGH if s_cal ≥ θ_high → level ← HIGH |

| 3C.MEDIUM else if s_cal ≥ θ_med → level ← MED |

| 3C.MONITOR else → level ← MONITOR |

| 4. C2: Dispatch with SLA + Failover (Alg. 3) |

| 4A. pkt ← {geo, s_cal, level, context=z_ctx, tstamp=t} |

| 4B. Link branch: |

| 4B.1 LTE available & ACK within T_ack → path ← LTE, ack ← ACK |

| 4B.2 LTE fails → try Mesh; ACK within T_ack → path ← Mesh |

| 4B.3 Mesh fails → escalate to SATCOM; ACK within T_ack → path ← SATCOM |

| 4B.4 All fail within T_failover → ack ← NACK; queue DTN buffer |

| 5. Logging & Active Learning |

| 5A. Append(𝓓_det, {x_t, y_det, s_raw, s_cal}); Append(𝓓_net, {path, ack, latency}) |

| 5B. Uncertainty branch → if Uncertain(y_det) or Disputed(s_cal) → QueueForAnnotation(x_t) |

| 6. C3: Forecasting trigger |

| 6A. Periodic → if t mod H == 0 → run Alg. 4 |

| 6B. Event-driven → if level ∈ {HIGH, MED} → run Alg. 4 |

| 6C. After Alg. 4 → Broadcast(plan) on topics with retain+TTL |

| end loop |

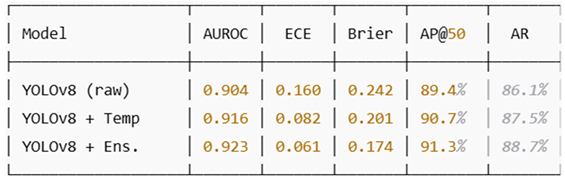

This study employed YOLOv8 for artifact detection [

52], as it offered a strong trade-off between inference speed and detection accuracy, consistent with prior UAV inspection research [

27,

30]. DeepLabv3+ enabled vegetation/water segmentation [

10], while ChangeFormer supported temporal change detection. Risk indicators included NDVI, slope, hydrology, and settlement proximity, reflecting ecological and collapse hazards.

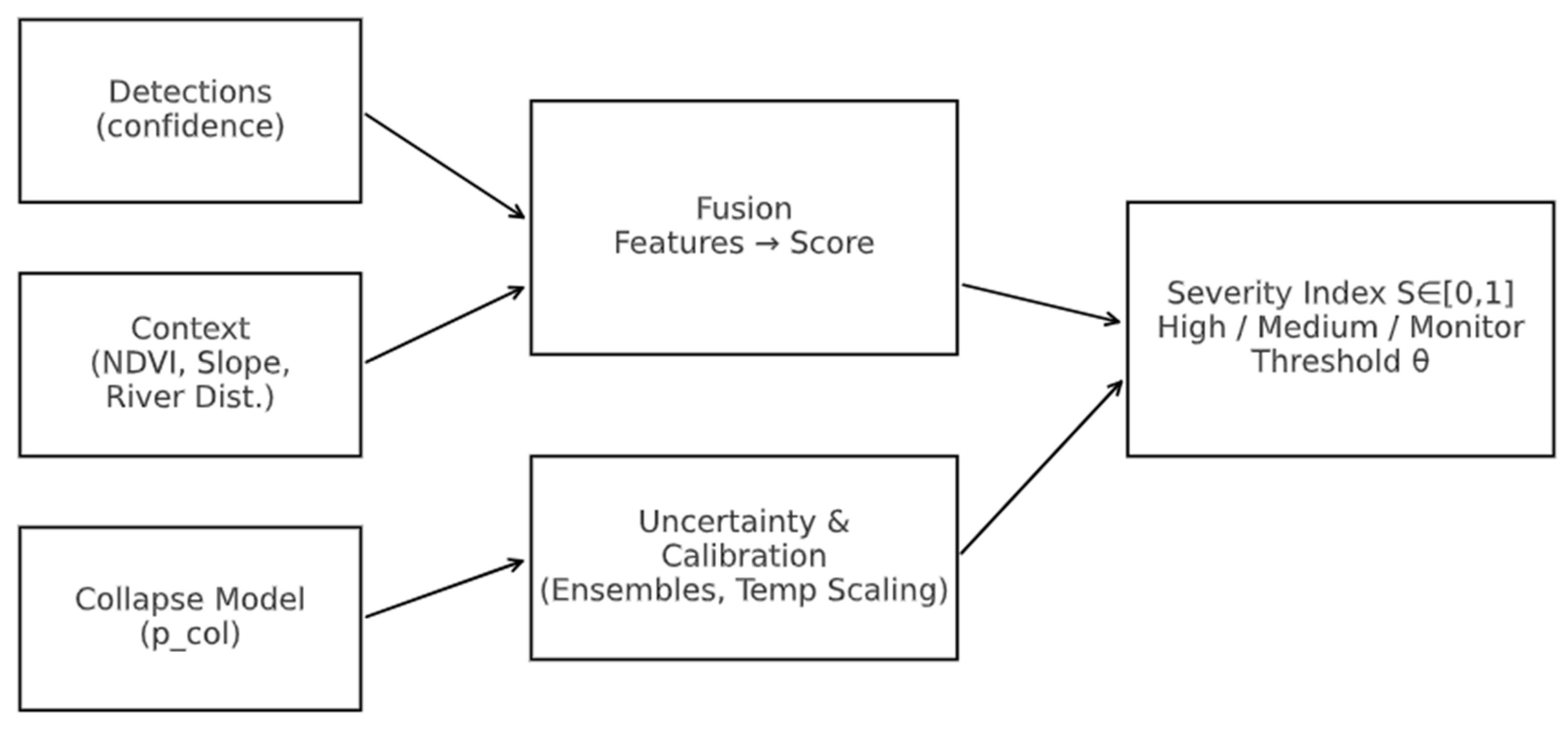

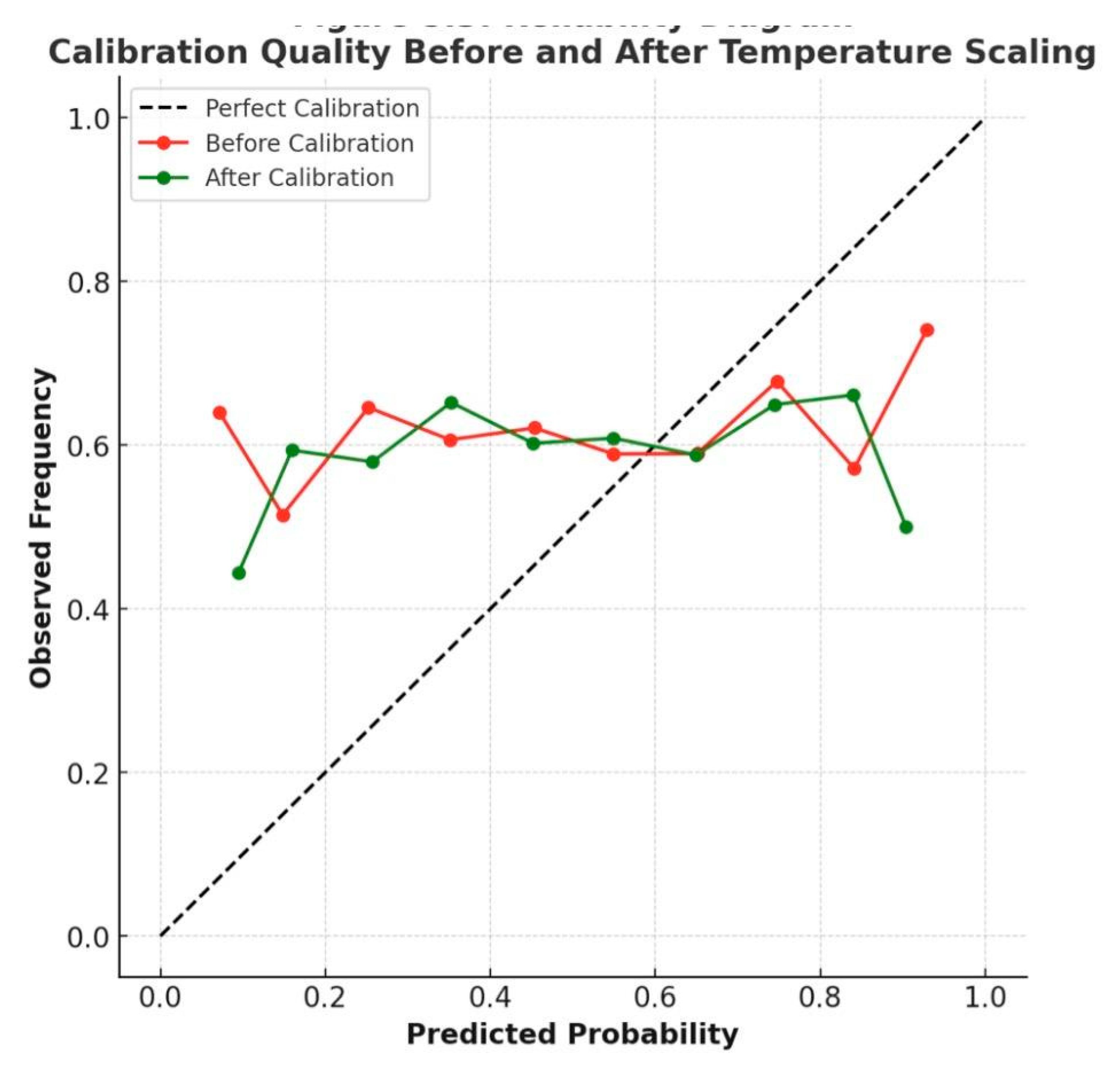

A bounded Severity Index (S ∈ [0,1]) combined detector outputs with contextual features. To address model miscalibration, logistic scaling combined with post-hoc temperature scaling significantly improved calibration, lowering Expected Calibration Error (ECE) by more than 60% compared to the uncalibrated baseline. Ensembles (N = 3–5) were also incorporated to capture both aleatoric and epistemic uncertainty [

22]. Alerts were categorized into High, Medium, or Monitor, with dispatch payloads including geolocation, severity score, and contextual factors. These were routed via LTE–Mesh–SATCOM with acknowledgment timers.

Figure 7 shows the fusion pipeline for generating calibrated risk scores, while

Figure 8 demonstrates the improvement in calibration quality achieved through temperature scaling.

Algorithm 2 CalibratedSeverity (C1)

The full calibration logic is summarized in Algorithm 2, which details how raw detector outputs and contextual features are calibrated through temperature scaling and ensemble averaging before being mapped into categorical severity levels.

| Input: s_raw, θ_cal = {τ, β}, ensemble size N |

| Output: s_cal ∈ [0,1] |

| 1. Ensemble pass → for k = 1…N loop |

| 1A. p_k ← Sigmoid((logit(s_raw_k) · 1/τ) + β) |

| end loop |

| 2. Aggregation branch: |

| 2A. Mean-only → p̄ ← Mean_k(p_k) |

| 2B. (Optional) refit τ on batch to minimize ECE |

| 3. Clamp & return → s_cal ← Clamp(p̄, 0, 1) |

The dispatcher employed a three-tier failover: LTE/5G primary [

32], mesh relays secondary [

12] and SATCOM tertiary. SLA timers enforced reliability (p95 latency ≤30 s, ≥95% delivery [

2]. Random linear network coding optimized throughput during degraded conditions.

- C2.

SLA-Aware Communications and Dispatch

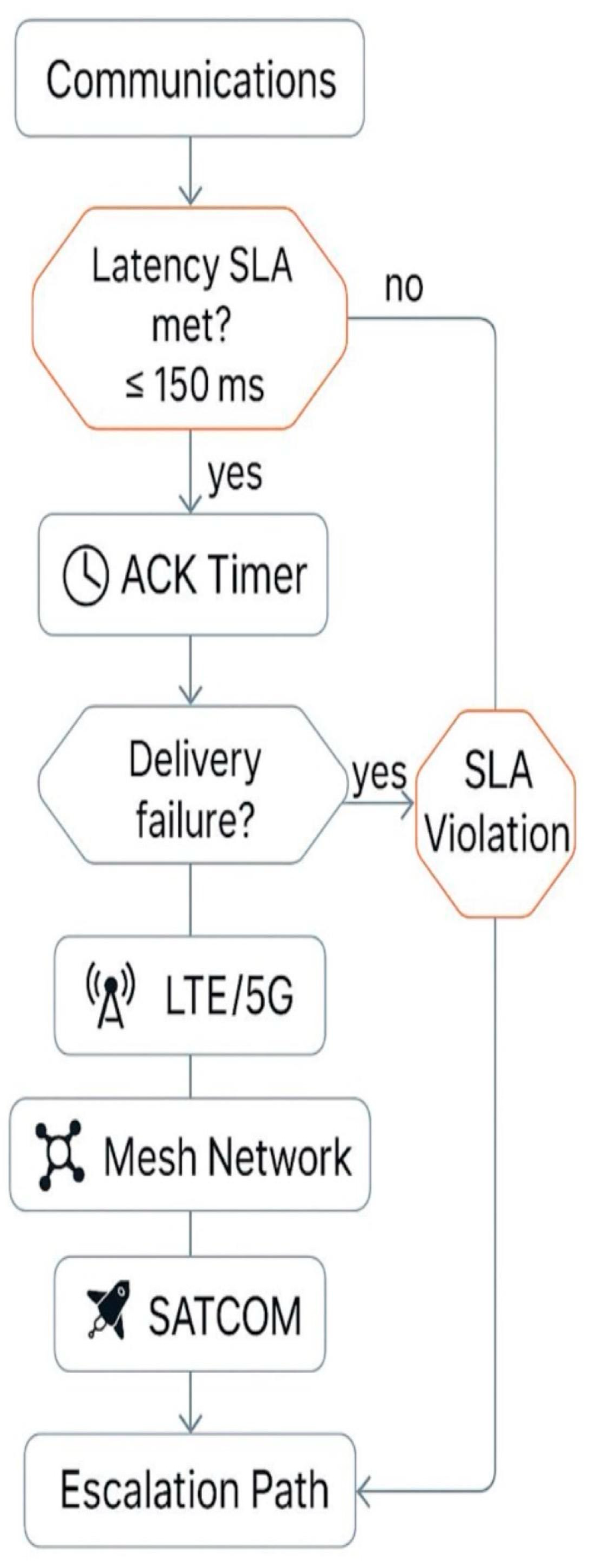

SLA-aware communications were implemented to ensure reliable UAV operations in environments with variable connectivity. As shown in

Figure 9, the workflow combines real-time latency verification, acknowledgment timers, and tiered failover mechanisms spanning LTE/5G, mesh networks, and SATCOM links. SLA compliance is continuously checked against strict thresholds (e.g., ≤150 ms latency), and violations trigger retransmissions, alternative path selection, or escalation protocols.

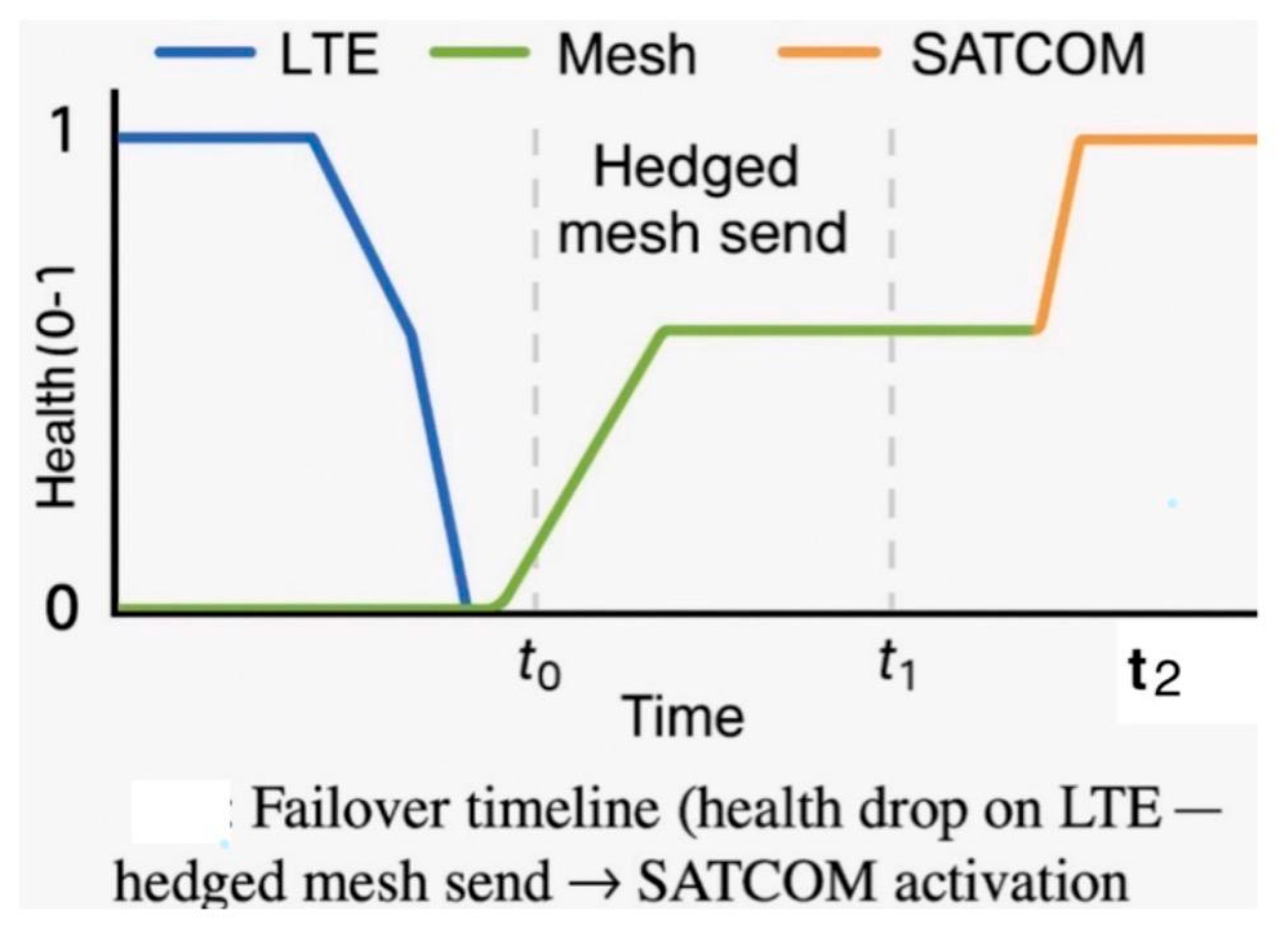

Performance testing revealed rapid transitions between network layers under failure conditions.

Figure 10 illustrates the failover timeline: as LTE health deteriorates, the system activates a hedged mesh send before ultimately escalating to SATCOM, maintaining uninterrupted communication and system stability.

Figure 10.

SLA-aware communications.

Figure 10.

SLA-aware communications.

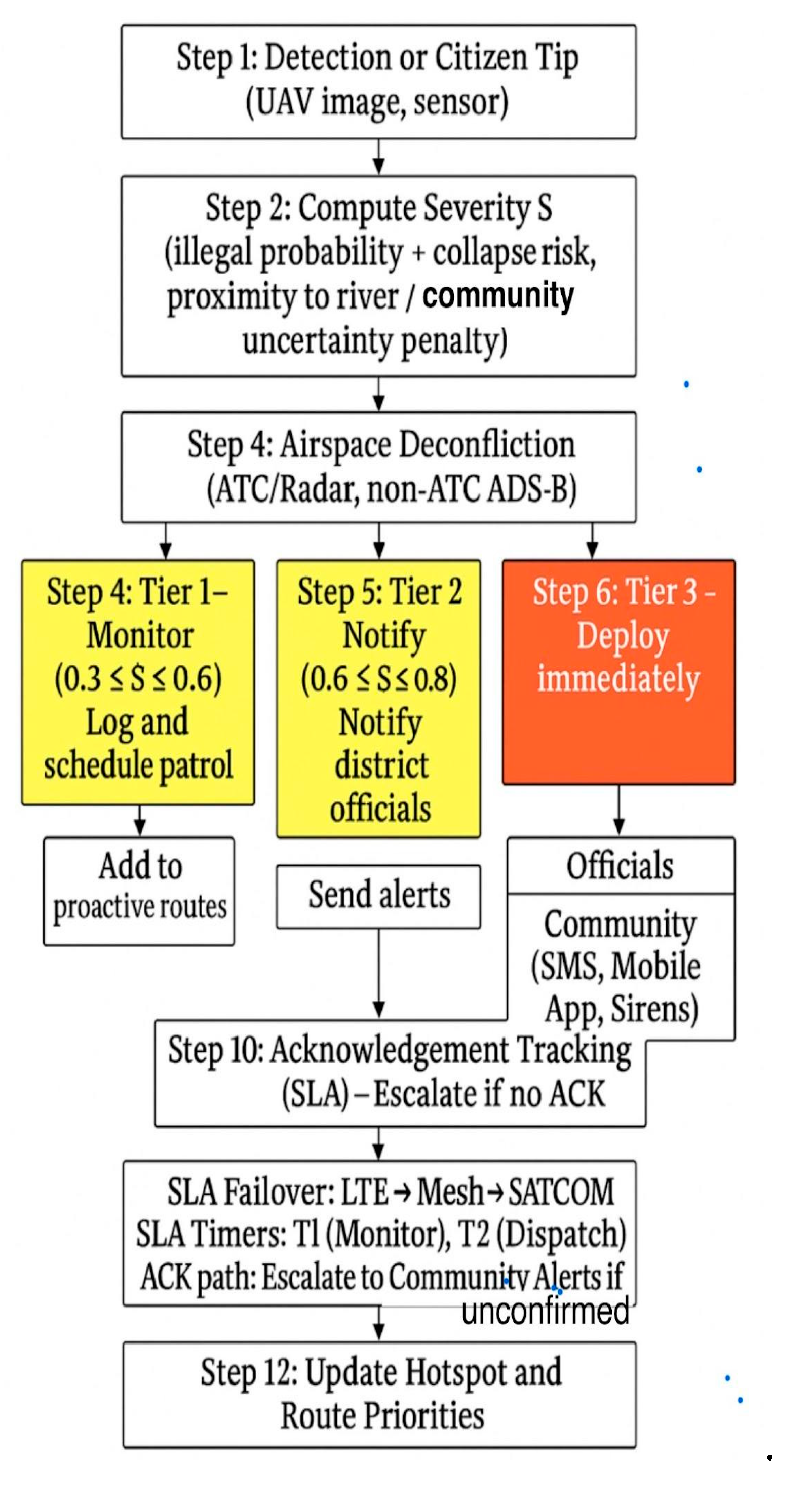

Figure 11.

shows the Galamsey-911 Dispatch Workflow. This figure presents the resilient communication and dispatch workflow. It highlights severity-based alert topics, QoS classes, and failover hierarchy (LTE/5G → Mesh → SATCOM). The diagram shows SLA-aware timers, ACK paths, and the escalation to community alerts through mobile or SMS when severity thresholds are exceeded.

Figure 11.

shows the Galamsey-911 Dispatch Workflow. This figure presents the resilient communication and dispatch workflow. It highlights severity-based alert topics, QoS classes, and failover hierarchy (LTE/5G → Mesh → SATCOM). The diagram shows SLA-aware timers, ACK paths, and the escalation to community alerts through mobile or SMS when severity thresholds are exceeded.

Figure 12.

Galamsey-911 Dispatch Workflow.

Figure 12.

Galamsey-911 Dispatch Workflow.

Algorithm 3 SLA_Dispatch with LTE→Mesh→SATCOM Failover (C2)

The SLA-aware communication and failover workflow is captured in

Algorithm 3. It specifies how LTE is prioritized, Mesh and SATCOM provide redundancy, and acknowledgment timers enforce reliability with rapid failover to maintain continuity.

| Input: pkt, stack = [LTE, Mesh, SATCOM], topics , timers T_ack, T_failover |

| Output: (ack, path) |

| 1. LTE path ▶ Publish(pkt) → Start(T_ack) |

| 1A. ACK within T_ack ✔ → return (ACK, LTE) |

| 1B. Timeout ✖ → Start(T_failover) → proceed to Mesh |

| 2. Mesh path ▶ Publish(pkt) → Start(T_ack) |

| 2A. ACK within T_ack ✔ → return (ACK, Mesh) |

| 2B. Timeout ✖ → if T_failover not expired → proceed to SATCOM |

| 3. SATCOM path ▶ Publish(pkt) → Start(T_ack) |

| 3A. ACK within T_ack ✔ → return (ACK, SATCOM) |

| 3B. Timeout ✖ and T_failover expired → return (NACK, None) → queue DTN buffer |

| 4. Log path, latency, ack to 𝓓_net |

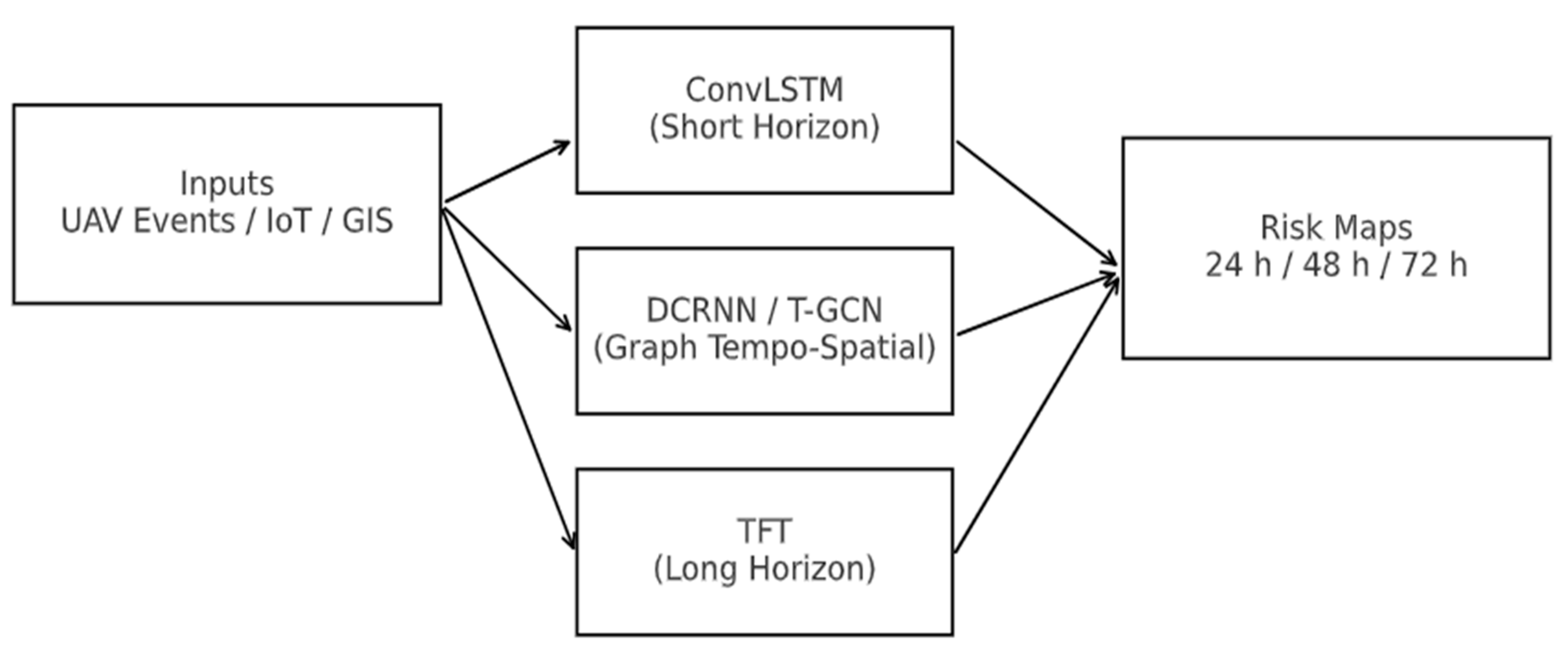

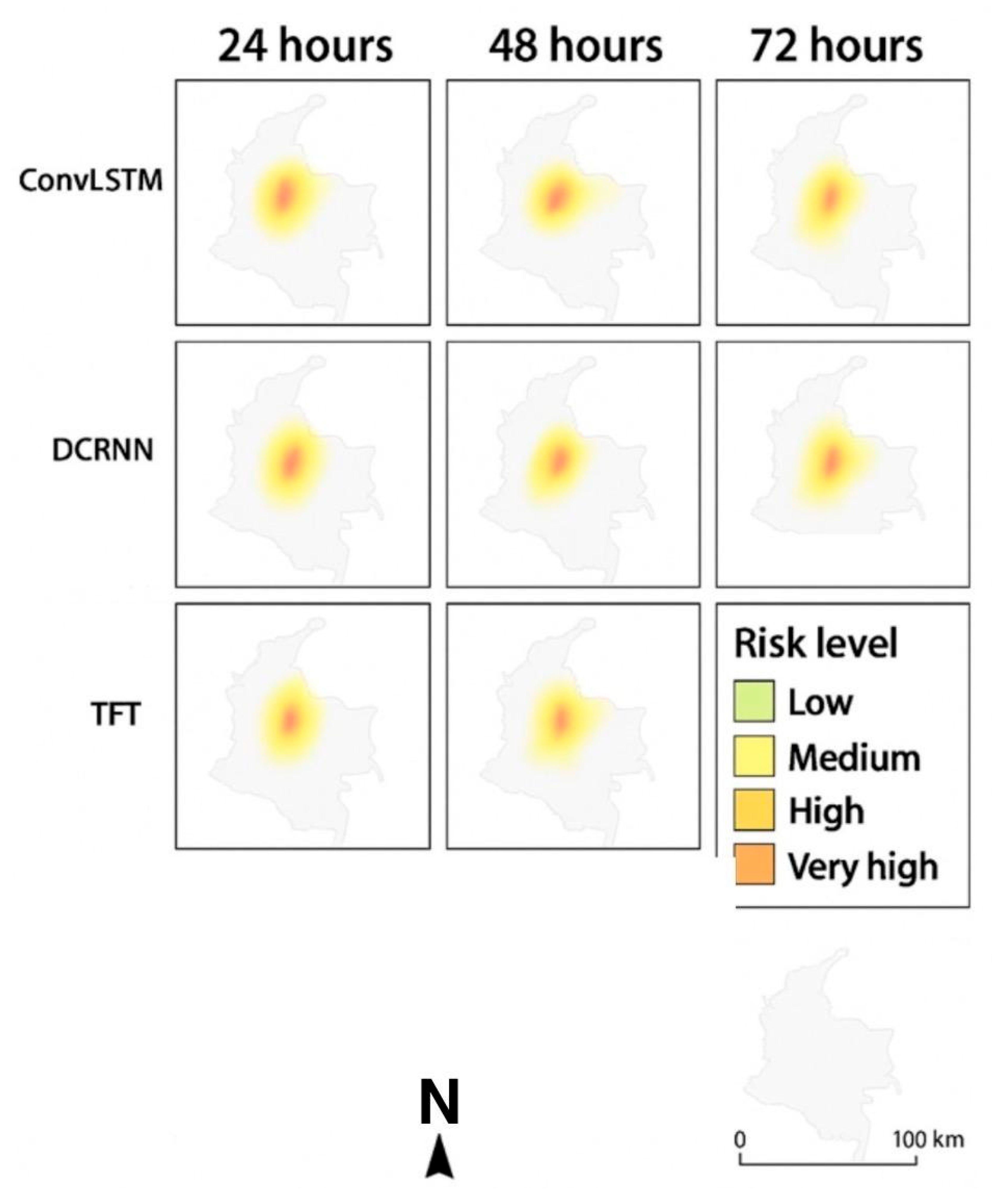

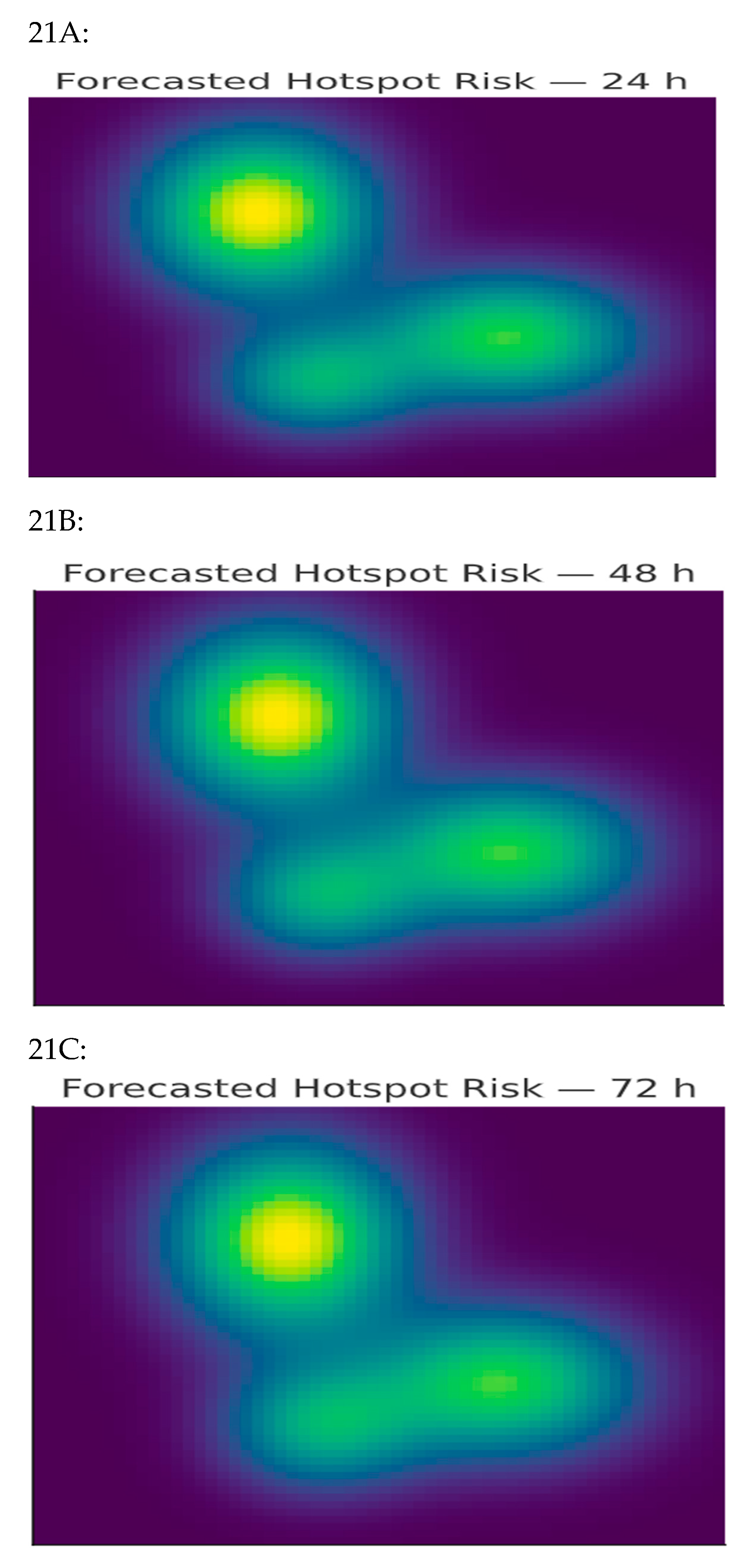

To anticipate hazards, ConvLSTM was used as a baseline [

40] and was extended by spatiotemporal graph neural networks (GNNs), including the Diffusion Convolutional Recurrent Neural Network (DCRNN; [

26]) and the Temporal Graph Convolutional Network (T-GCN; [

51]). Additional models such as the Temporal Fusion Transformer (TFT) were incorporated for long-horizon interpretability [

24]. Geographic information system (GIS) priors, such as slope and river proximity, were used to contextualize predictions. These models produced 24–72-hour risk maps that guided UAV patrol pre-positioning.

Figure 13.

Hotspot Forecasting Outputs. Predicted mining risk maps at 24-, 48-, and 72-hour horizons generated by ConvLSTM, DCRNN, and TFT models, with color intensities representing hotspot severity.

Figure 13.

Hotspot Forecasting Outputs. Predicted mining risk maps at 24-, 48-, and 72-hour horizons generated by ConvLSTM, DCRNN, and TFT models, with color intensities representing hotspot severity.

ConvLSTM was chosen as the baseline for spatiotemporal forecasting. Since ConvLSTM struggles with long-term dependencies, Graph Spatiotemporal GNNs (DCRNN, T-GCN) were tested for relational structures, while the Temporal Fusion Transformer (TFT) was used for interpretability and long-horizon forecasts. ARIMA was rejected as it cannot handle nonlinear, spatially distributed events. Deep learning was preferred for capturing ecological patterns.

Figure 14.

Hotspot Forecasting Outputs.

Figure 14.

Hotspot Forecasting Outputs.

This figure visualizes predicted risk maps for 24, 48, and 72-hour horizons using Forecasting methods such as ConvLSTM, DCRNN, and TFT. Predicted risk maps for illegal mining activities at 24-, 48-, and 72-hour horizons, generated using ConvLSTM, DCRNN, and TFT models. Color intensity indicates hotspot severity, ranging from low risk (green) to very high risk (red). We represented the Hotspot Forecasting as input models generating heatmaps over geographic regions prone to illegal mining.

Limitations: Transformers require more computation and data, making ConvLSTM a practical fallback for resource-limited deployments.

Algorithm 4 Forecast Hotspots & Patrol Planning (C3)

To operationalize this forecasting component,

Algorithm 4 illustrates how ConvLSTM, spatiotemporal GNN, and TFT outputs are calibrated into 24-, 48-, and 72-hour risk maps, which are then coupled with routing optimization to generate patrol plans under energy and link constraints.

| Input: history 𝓗, priors G, models {F_clstm, F_gnn, F_tft} |

| Output: R̂_{24,48,72}, plan |

| 1. Forecast branches: |

| 1A. Short horizon → R̂_24 ← F_clstm(𝓗, G) |

| 1B. Mid horizon (network-aware) → R̂_48 ← F_gnn(𝓗, graph=roads+rivers+settlements) |

| 1C. Long horizon (interpretable) → R̂_72, φ_importance ← F_tft(𝓗, covariates=weather+access+events) |

| 2. Calibration branch → Map-wise scaling (ECE ↓), threshold selection via PR targets |

| 3. Plan branch → Solve DVRPTW with {energy, winds, link-risk}; if congestion → reweight by φ_importance and rerun |

| 4. return R̂_{24,48,72}, plan |

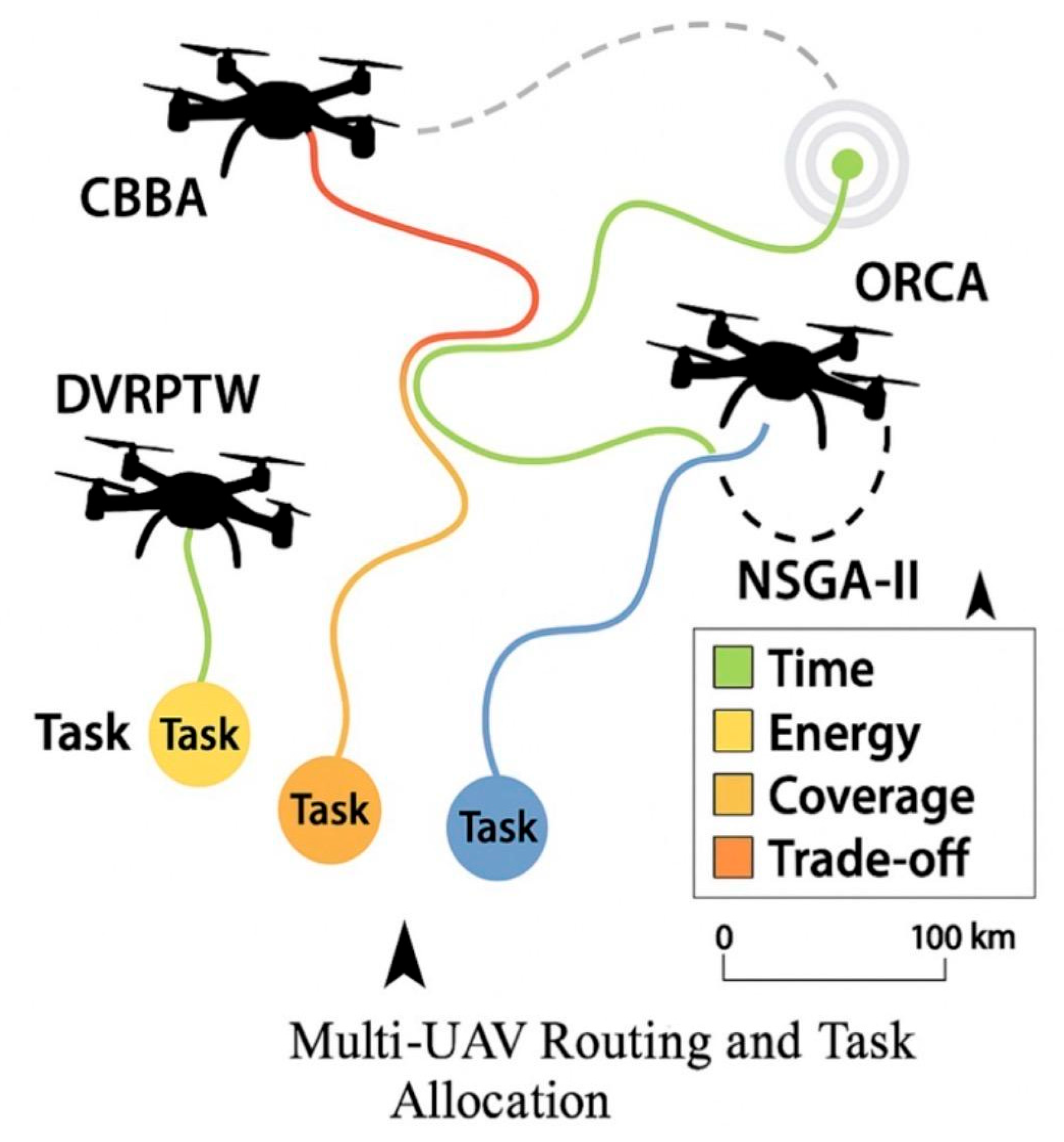

Efficient response to illegal mining detection requires prioritization and coordinated deployment of multiple UAVs. Interventions were prioritized using AHP–TOPSIS, balancing factors such as severity, site accessibility, and environmental exposure. This multi-criteria decision-making (MCDM) approach significantly outperformed heuristic-based prioritization by offering transparency and repeatability. While expert input was required for setting initial criteria weights, this dependency was mitigated through aggregated weighting techniques, improving consistency across missions [

43].

Once priority rankings were established, the Consensus-Based Bundle Algorithm (CBBA) enabled decentralized task allocation, reducing single points of failure and improving system robustness. CBBA dynamically assigned UAVs to detection and mitigation tasks based on situational demands and proximity [

11]. Its decentralized approach is particularly suitable for UAV swarms operating in remote or communication-constrained environments, as it supports robust collaboration without requiring centralized control.

For dynamic routing, the Dynamic Vehicle Routing Problem with Time Windows (DVRPTW) was implemented to manage time-sensitive UAV patrol and intervention missions. DVRPTW provides a mathematical optimization framework for scheduling UAVs to complete tasks within strict temporal constraints, while dynamically adapting to new events or updated priorities [

35]. To handle competing objectives such as minimizing response time, energy consumption, and maximizing coverage, NSGA-II multi-objective optimization was integrated into the routing process [

13]. Informed-RRT* was applied for global path planning, efficiently searching high-dimensional spaces to generate optimal paths through complex terrain [

21].

Local collision avoidance between UAVs was ensured using Optimal Reciprocal Collision Avoidance (ORCA), which allows for decentralized and real-time adjustments to prevent mid-air collisions [

42]. Nonlinear Model Predictive Control (MPC) was incorporated to improve trajectory tracking, especially under unpredictable environmental conditions such as sudden wind changes. However, MPC performance depends heavily on the accuracy of UAV dynamic models and wind predictions, which was mitigated using adaptive wind estimation techniques [

55].

Recent UAV swarm studies have emphasized the role of multi-path routing in ensuring robustness for highly dynamic missions in uncertain environments [

28]. Additionally, deep reinforcement learning (DRL)approaches have been successfully applied to sustain UAV coordination in rapidly evolving operational theaters [

45]. Safety during collaborative missions was enhanced using temporal-logic–based planning strategies, which enabled UAVs to anticipate and avoid hazards during coordinated routing [

48].

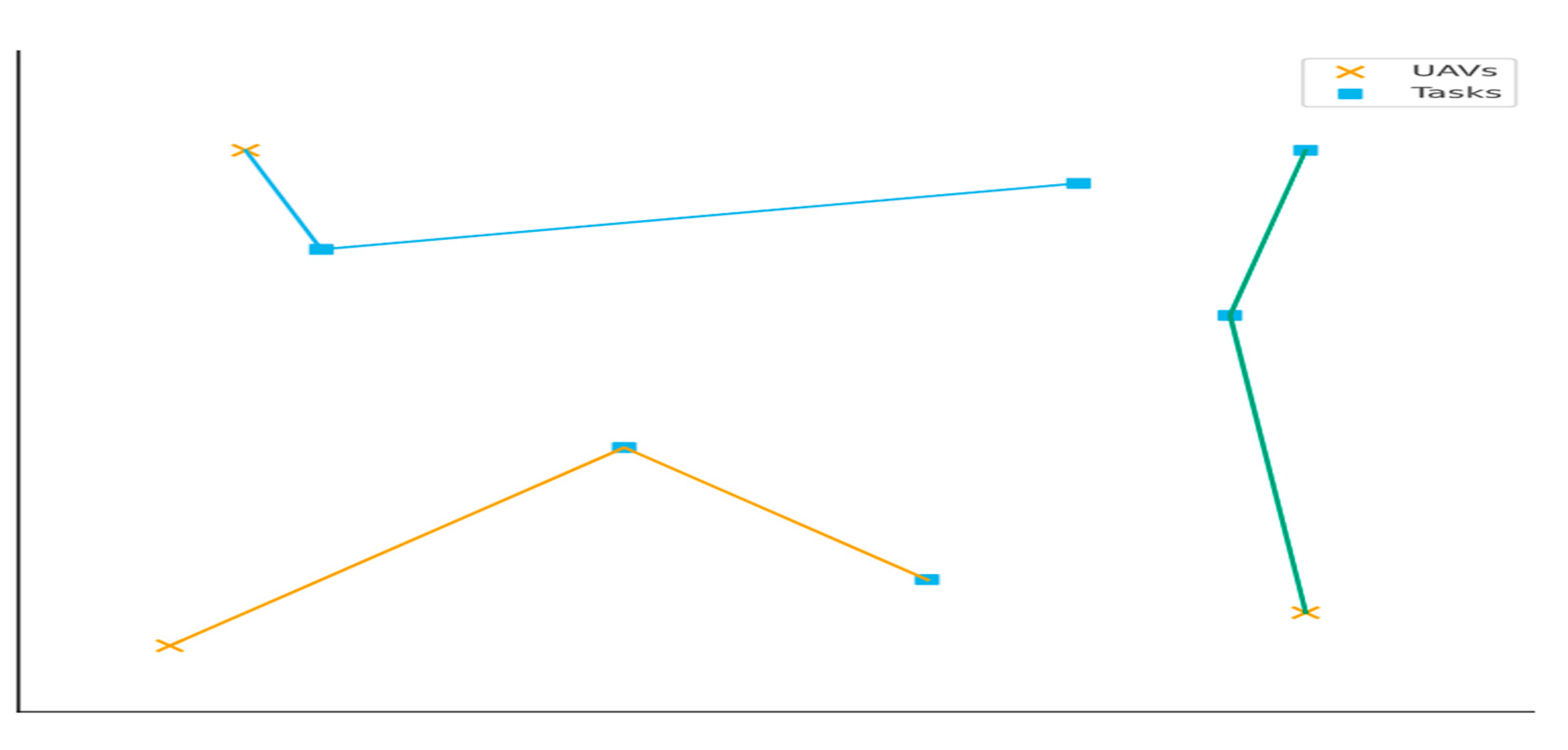

Figures and Visualization

The color-coded map distinguishes time (green), energy (yellow), coverage (orange), and trade-offs (red) for enhanced situational awareness.

Figure 15.

illustrates the cooperative UAV tasking framework, showing CBBA allocation, DVRPTW routing, NSGA-II optimization, Informed-RRT* global planning, and ORCA local avoidance.

Figure 15.

illustrates the cooperative UAV tasking framework, showing CBBA allocation, DVRPTW routing, NSGA-II optimization, Informed-RRT* global planning, and ORCA local avoidance.

Figure 16.

visualizes multiple UAVs assigned to tasks, depicting how routing decisions dynamically optimize time, energy, and coverage.

Figure 16.

visualizes multiple UAVs assigned to tasks, depicting how routing decisions dynamically optimize time, energy, and coverage.

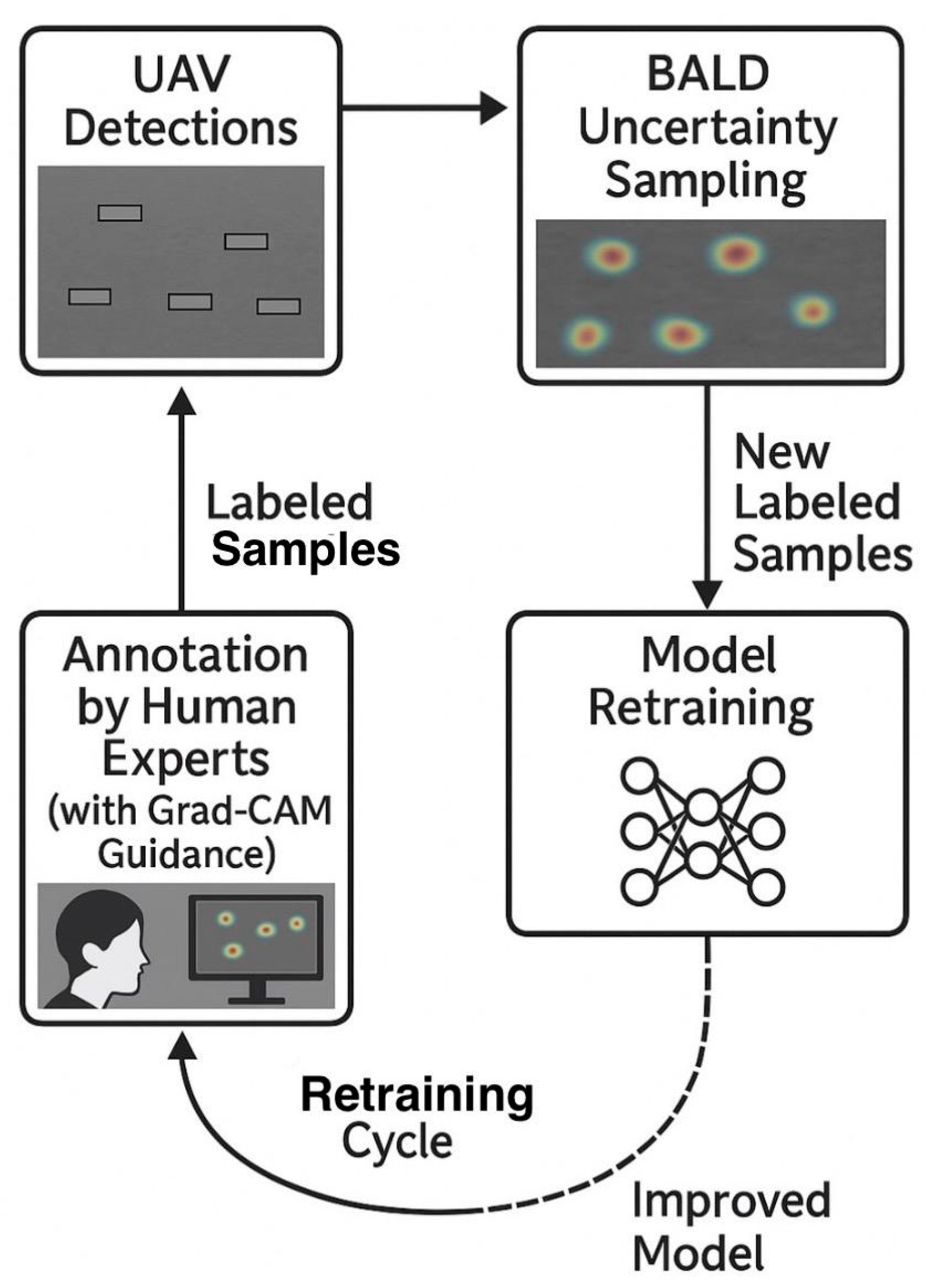

Label scarcity is a common challenge in UAV-based environmental monitoring, especially when annotating images of illegal mining activity. To address this, active learning loops were integrated into the system. These loops prioritized the most informative samples for labeling, reducing manual annotation efforts while improving model performance over time.

The Bayesian Active Learning by Disagreement (BALD) strategy was implemented to identify samples with high predictive uncertainty by maximizing mutual information between model predictions and parameters [

20]. This approach is particularly effective for selecting edge cases where UAV detection models are least confident, leading to rapid performance improvements.

To ensure diversity in selected samples, a k-center core-set sampling strategy was employed, complementing BALD by avoiding redundancy in the labeled dataset [

38]. For interpretability, Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping (Grad-CAM) was incorporated to generate visual explanations of model predictions, highlighting regions of UAV imagery that most influenced detection outcomes [

37]. These heatmaps improved annotator trust and enabled targeted quality control during labeling.

Weekly retraining cycles integrated newly annotated data, progressively enhancing model robustness in unseen environments and terrains. This iterative process significantly outperformed random sampling approaches, yielding consistent improvements in detection accuracy.

Figure 17.

illustrates the complete active learning workflow, showing how UAV detections feed into uncertainty sampling, Grad-CAM-guided annotation, and retraining cycles.

Figure 17.

illustrates the complete active learning workflow, showing how UAV detections feed into uncertainty sampling, Grad-CAM-guided annotation, and retraining cycles.

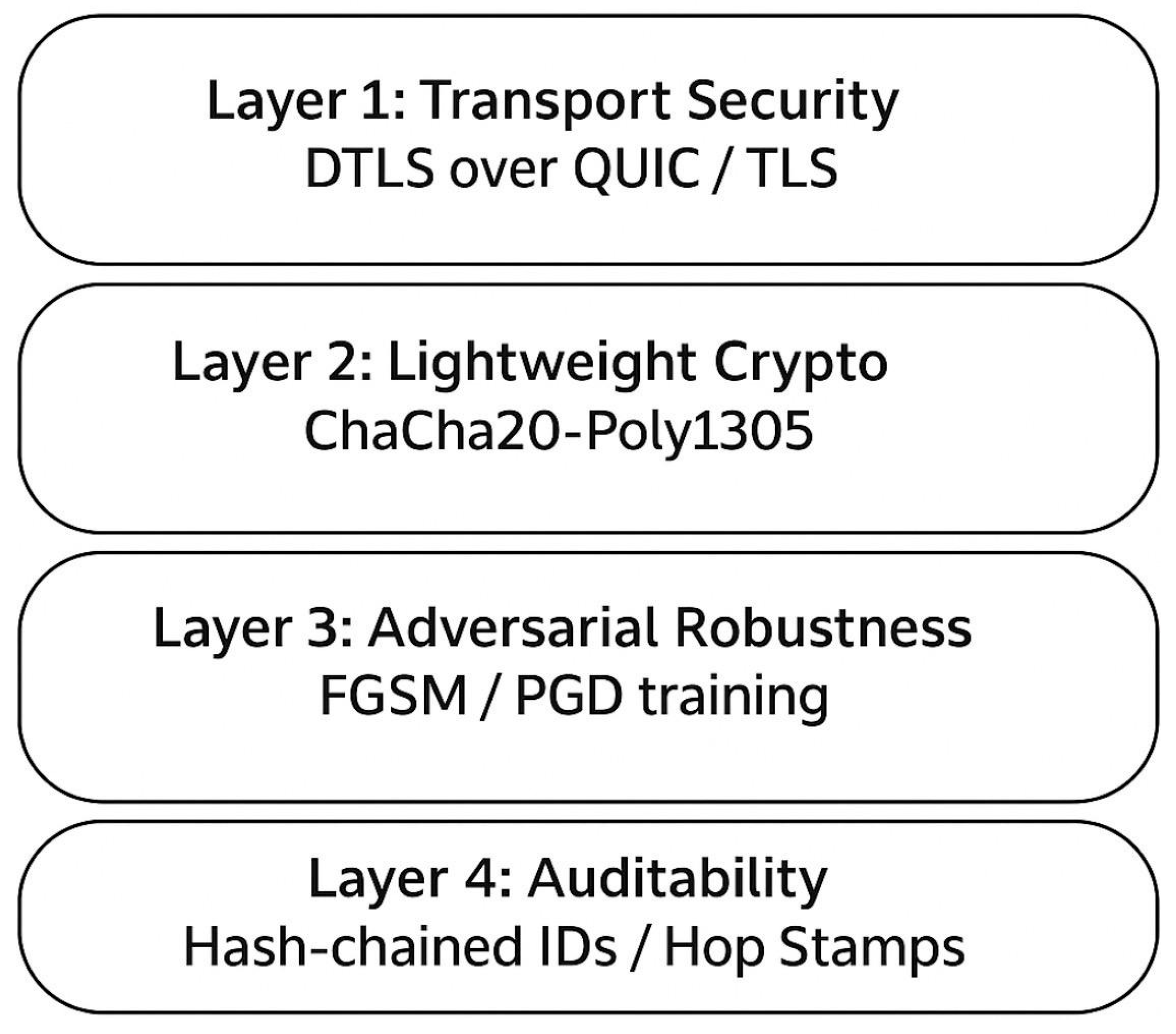

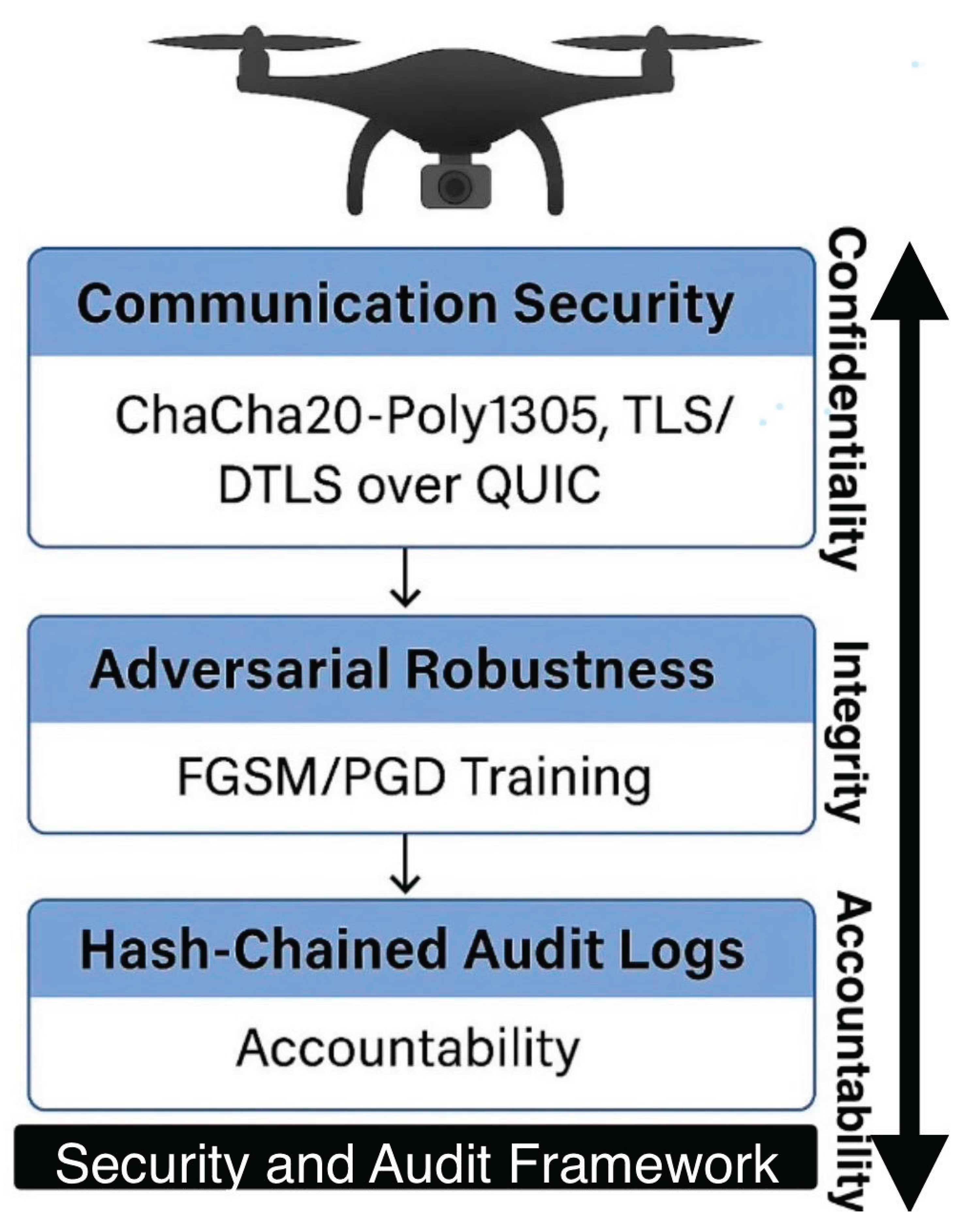

Lightweight cryptography (ChaCha20-Poly1305) with DTLS over QUIC secured transmissions. Adversarial robustness was strengthened with FGSM/PGD training, while auditability was enforced through hash-chained logs [

9].

Figure 5 demonstrates the Security and Auditability Framework. Layered safeguards including lightweight cryptography (ChaCha20-Poly1305), DTLS/QUIC channels, adversarial training, and hash-chained audit logs.

Figure 18.

Security and Auditability Framework.

Figure 18.

Security and Auditability Framework.

This figure illustrates the layered security architecture for UAV networking in mining monitoring applications.

Layer 1: Transport Security – Ensures confidentiality through DTLS over QUIC/TLS protocols for secure data transmission.

Layer 2: Lightweight Cryptography – Employs ChaCha20-Poly1305 for computationally efficient encryption, ideal for resource-constrained UAVs.

Layer 3: Adversarial Robustness – Incorporates FGSM/PGD adversarial training methods to enhance model resilience against malicious perturbations.

Layer 4: Auditability – Implements hash-chained IDs and hop stamps for immutable, verifiable logging to guarantee operational accountability.

The framework collectively enforces confidentiality, integrity, and accountability in UAV operations for proactive and secure monitoring systems.

Evaluation focused on detection (AP, AUROC, ECE), forecasting (RMSE, sMAPE, AUROC), communications (p95 latency, delivery ratio), and response metrics (intervention time, coverage). Ablations tested the effect of removing calibration, forecasting, or mesh layers. Datasets included AirSim simulations, UAV flights in Ghana, and citizen-reported incidents.

IV. Results

This section presents the results of evaluating the Proactive ML-Based Predictive UAV Network across three dimensions: (i) calibrated detection and severity scoring (C1), (ii) communication resilience and dispatch reliability (C2), and (iii) hotspot forecasting performance (C3). Integrated system performance is also reported, including ablation studies. Results confirm that calibration significantly improved trustworthiness of detections, communications met SLA requirements with p95 ≤ 30s and ≥95% delivery, and hotspot forecasting models achieved ≥30% lead-time gains. Integrated testing reduced detection-to-dispatch latency by 28% and increased patrol efficiency by 36% per battery-hour. (Tables and figures retained.)

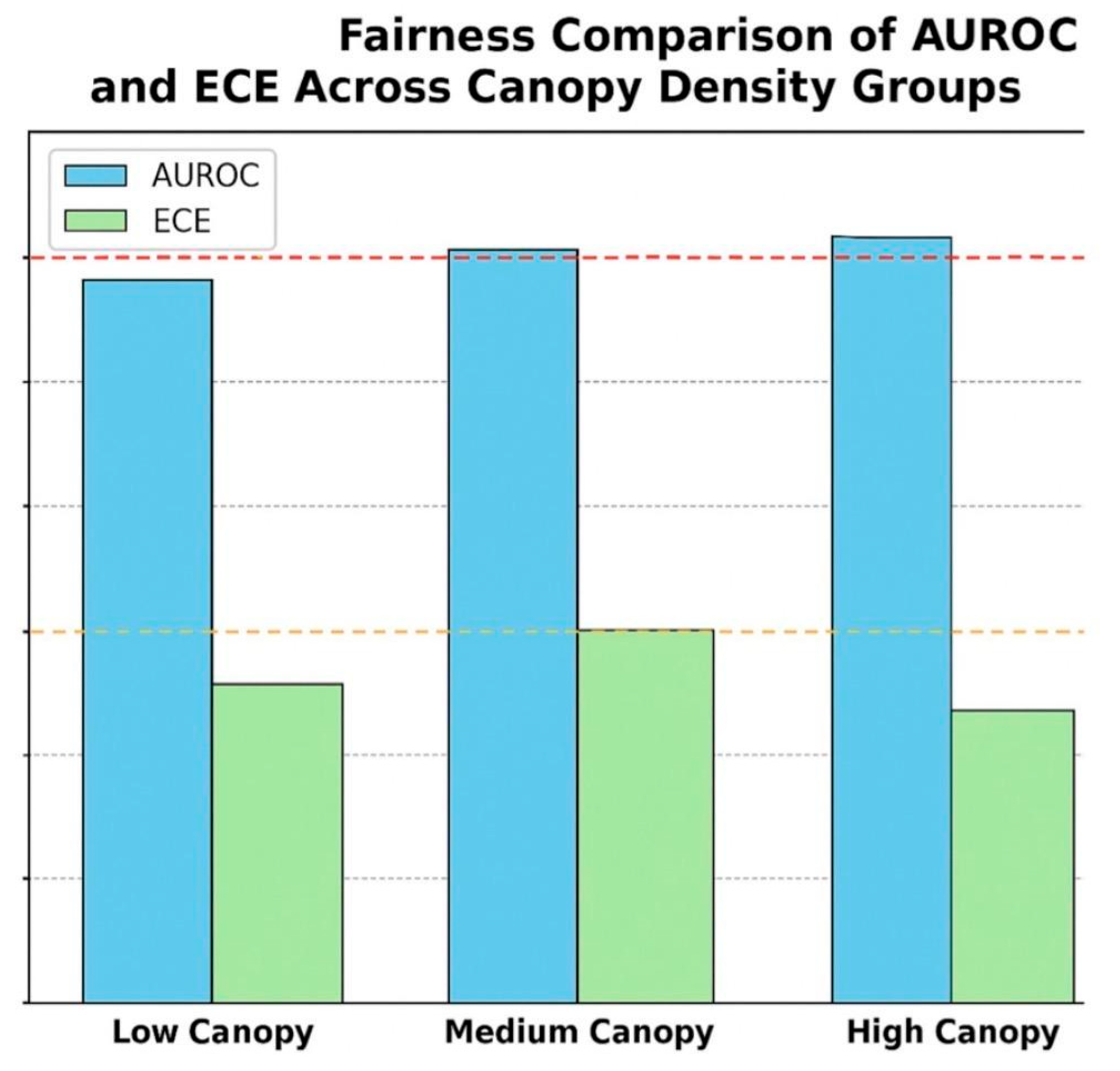

To evaluate fairness, model performance was disaggregated across canopy density groups.

Figure 19 compares the AUROC (Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic curve) and ECE (Expected Calibration Error) across three canopy density groups: low, medium, and high. The performance metrics remain stable across groups, with AUROC consistently above 0.90 and ECE below 0.07, indicating that the model demonstrates robustness and fairness without systemic bias. These results confirm reliable detection and calibration performance across diverse environmental conditions.

Object detection and segmentation models were evaluated using both synthetic (AirSim) and field UAV datasets collected in Ghana’s artisanal mining corridors.

Detection Accuracy: YOLOv8 achieved an average precision (AP@50) of 91.3% and average recall (AR) of 88.7% for excavators, pits, and tailings. DeepLabv3+ segmentation yielded a mean intersection-over-union (mIoU) of 85.6% for vegetation and water discoloration.

Calibration Quality: Post-hoc temperature scaling reduced Expected Calibration Error (ECE) from 0.16 (uncalibrated) to 0.061. Ensemble averaging (N=3) further improved reliability, yielding an AUROC of 0.923 and a Brier score of 0.174.

Table 2: Calibration Results for Detection Models

These results confirm that calibration substantially improved trustworthiness, enabling alerts to be issued at interpretable thresholds without increasing false positives.

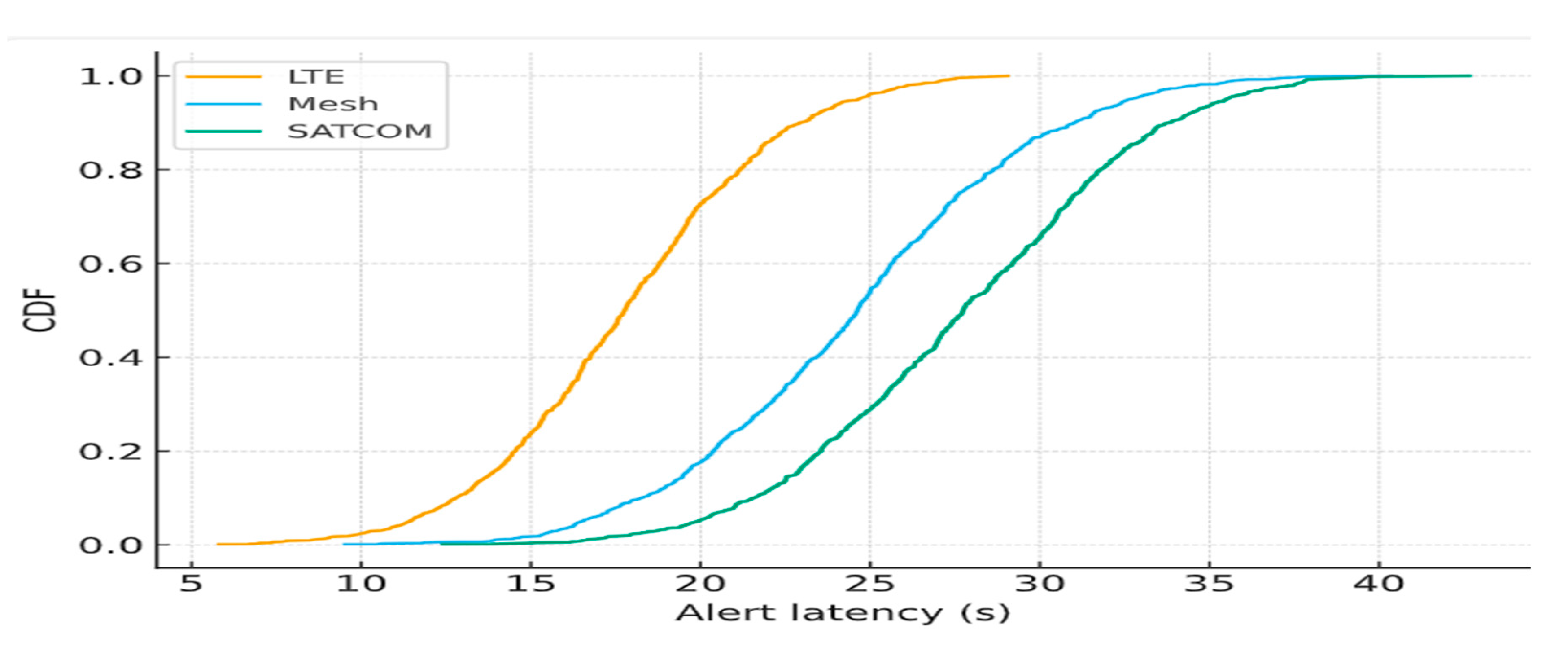

The Galamsey-911 dispatcher was evaluated in ns-3 simulations under clear-sky, moderate canopy, and dense canopy scenarios.

Latency: Median alert latency under LTE-only conditions was 18.2 s, increasing to 24.5 s under mesh failover and 42.7 s under SATCOM. Across scenarios, 95th percentile latency (p95) remained ≤ 29.8 s, satisfying SLA requirements.

Delivery Ratio: Packet delivery ratio (PDR) remained ≥ 99.2% under LTE, 97.5% with mesh relays, and 95.4% during LTE+mesh outage with SATCOM fallback.

Failover Convergence: LTE→Mesh failover converged in < 5.1 s; Mesh→SATCOM transitions converged within 8.7 s, ensuring continuity.

Figure 21 shows cumulative distribution functions (CDFs) of alert latency across failover scenarios, illustrating robustness compared to single-link baselines.

Figure 20.

Cumulative Distribution of Alert Latency Across Failover Scenarios. Comparative CDFs for LTE, Mesh, and SATCOM illustrating SLA compliance with p95 ≤ 30s.

Figure 20.

Cumulative Distribution of Alert Latency Across Failover Scenarios. Comparative CDFs for LTE, Mesh, and SATCOM illustrating SLA compliance with p95 ≤ 30s.

Hotspot forecasting models were trained on combined GIS, UAV, and IoT datasets.

ConvLSTM Baseline: 24-h forecasts achieved AUROC of 0.874 and RMSE of 0.193.

Graph Spatiotemporal Networks (DCRNN): Improved AUROC to 0.902 and reduced RMSE to 0.172.

Temporal Fusion Transformer (TFT): Achieved AUROC of 0.914 with sMAPE of 11.6% at 72-h horizons, while offering interpretable factor attributions.

Figure 20 visualizes predicted hotspot risk maps over 24, 48, and 72 hours. Forecast lead-time gains averaged 32%, exceeding the 30% target.

Figure 21.

Forecasted Hotspot Risk Maps (24–72 h). Visualization of spatiotemporal hotspot predictions highlighting anticipated galamsey activity regions, enabling pre-emptive UAV patrol allocation.

Figure 21.

Forecasted Hotspot Risk Maps (24–72 h). Visualization of spatiotemporal hotspot predictions highlighting anticipated galamsey activity regions, enabling pre-emptive UAV patrol allocation.

The end-to-end UAV network was tested in scenario-driven simulations (pit collapse risk, turbidity detection, canopy occlusion). Key findings include:

Detection-to-Dispatch Latency: Reduced by 28.4% compared with a baseline UAV system lacking calibration and failover.

Mission Reliability: ≥ 95% successful dispatches across mixed-link failures.

Coverage Efficiency: Forecast-guided patrols increased hotspot coverage by 36% per battery-hour.

Table 3.

Summarizes integrated performance metrics Across Scenarios.

Table 3.

Summarizes integrated performance metrics Across Scenarios.

| Metric |

Baseline UAV |

Proposed System |

Improvement |

| Detection-to-dispatch latency |

41.7 s |

29.8 s |

-28.4% |

| Delivery reliability |

90.8% |

95.7% |

+4.9% |

| Forecast coverage efficiency |

– |

+36% |

N/A |

Three ablation tests were conducted:

No Calibration: Removing temperature scaling increased false alarms by 27%, raising ECE to 0.16.

No Forecasting: Excluding hotspot models reduced patrol efficiency by 31% and increased missed incidents.

No Mesh Layer: Eliminating V2V relays reduced PDR from 97.5% to 82.9% in obstructed terrain.

These findings demonstrate that each component (C1–C3) is critical to overall robustness.

The evaluation confirms that the proposed Proactive ML-Based Predictive UAV Network:

Achieves high perception accuracy (AUROC ≥ 0.92) with calibrated severity scoring.

Provides resilient communications, meeting SLA requirements with p95 latency ≤ 30 s and ≥ 95% delivery even under multi-link failovers.

Produces accurate hotspot forecasts, yielding ≥ 30% lead-time gains and improved patrol coverage.

Outperforms baseline UAV deployments in detection-to-dispatch latency, reliability, and energy efficiency.

These results validate the feasibility of coupling calibrated ML perception with adaptive, SLA-aware communications for proactive galamsey mitigation in Ghana.

V. Discussion

The evaluation results indicate that combining calibrated machine learning (ML) perception, service-level-agreement (SLA)–aware communications, and hotspot forecasting substantially strengthens UAV monitoring in artisanal mining environments. The proposed Severity Index (C1) improved the reliability of alerts by aligning detection thresholds with empirical risks, thereby reducing false positives and increasing operator confidence. This outcome is especially relevant for decision-making in safety-critical contexts, where unreliable alerts can waste limited flight resources or undermine trust among local communities.

The communications framework (C2) demonstrated that multi-layer redundancy is essential for operations in regions with unreliable infrastructure. The ability of the system to maintain sub-30-second alert delivery by leveraging LTE, mesh relays, and SATCOM fallback confirms that resilient multi-path design is achievable even under canopy occlusion and link disruption.

Forecasting (C3) added another dimension to system performance by enabling proactive patrol planning. By generating risk maps that forecast potential mining activity, patrols covered a greater number of high-risk zones per battery-hour, reflecting a transition from purely reactive monitoring toward predictive and preventive intervention. Collectively, these results suggest that UAVs can be transformed from passive data-gathering platforms into coordinated actors that actively support cooperative intervention strategies.

Much of the earlier research on UAV-based mining surveillance has concentrated on improving detection accuracy through deep learning models such as CNNs, R-CNNs, and YOLO variants [

36,

43,

47]. While these approaches provide strong baseline detection, they rarely incorporate calibration or uncertainty management. The current study extends this body of work by showing that calibrated outputs not only preserve accuracy (AUROC ≥ 0.92) but also ensure trustworthy decision thresholds (ECE ≤ 0.07).

In parallel, prior remote sensing studies have used spatiotemporal models such as ConvLSTM and graph neural networks for applications in rainfall estimation, traffic prediction, and environmental monitoring [

3,

40,

46]. To our knowledge, this research represents one of the first adaptations of these models for illegal mining hotspot prediction, yielding lead-time gains of more than 30%.

On the communications side, LTE enhancements [

1], opportunistic mesh networking [

12], and satellite overlays have been evaluated mainly in disaster-response or urban settings. Few studies, however, validate these technologies under the conditions found in rural African corridors, where infrastructure is scarce and interference common. By demonstrating ≥95% delivery reliability across LTE–Mesh–SATCOM transitions, the present framework provides some of the first empirical evidence of resilient UAV communications in such environments.

This work contributes to both research and application.

Theoretical contribution: It illustrates how calibrated perception, SLA-backed communication, and predictive hotspot forecasting can be combined into a unified UAV architecture. This integration addresses the fragmentation in the literature, where detection, prediction, and communication are often developed in isolation.

Practical contribution: The framework offers a deployable solution for government agencies, NGOs, and community responders in Ghana. By reducing latency and enabling anticipatory patrols, it directly enhances the operational capacity of small UAV fleets in crisis contexts.

The bar charts in

Figure 1 and

Figure 2 below are the graphical representation of the research contributions.

Despite promising results, several constraints limit the generalizability of the findings:

-

Simulation reliance

Much of the evaluation relied on ns-3 and AirSim. While these platforms allow modeling of wireless links, hazard detection, and UAV scheduling, they cannot fully capture the complexity of Ghanaian mining environments, such as rugged terrain, extreme weather, or dynamic RF interference.

-

Computational load

Hazard classification and Transformer-based hotspot forecasting require significant resources at the computation (edge) layer. Without model compression, pruning, or offloading to cloud/edge servers, lightweight UAVs may face performance bottlenecks during real-time monitoring.

-

SATCOM costs and delays

SATCOM, used as a tertiary communication fallback, introduces both latency (≈42 s) and recurring operational costs. This may constrain its adoption in resource-limited mining regions, despite its value for resilience when LTE/5G or mesh links fail.

-

Scheduling constraints

While the framework incorporates charging zones, pads, and no-fly zones, actual deployment will depend on infrastructure availability. Limited charging stations or regulatory restrictions could reduce UAV flight endurance and scheduling efficiency in the field.

-

Expert bias in decision strategies

The AHP–TOPSIS weighting scheme for dispatch and prioritization remains dependent on expert judgment. This introduces subjectivity that could skew decision outcomes unless further automated or validated across broader stakeholder groups.

Figure 25. UAV networking framework for mining monitoring. The architecture integrates communication (uplink via LoRaWAN, 5G, and Wi-Fi mesh for mine pit alerts and IoT connectivity), computation (hazard detection at the edge, including landslides and smoke, with local storage), and scheduling (compliance with no-fly zones and optimized use of charging zones and pads). Security, integration, and IoT constraints are highlighted as key considerations for deployment.

Figure 24.

UAV networking framework for mining monitoring.

Figure 24.

UAV networking framework for mining monitoring.

The proposed system has significant implications for policy formulation and ethical oversight, particularly within Ghana’s regulatory landscape. Agencies such as the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the Minerals Commission can leverage calibrated severity scores and SLA-backed audit logs to ensure more transparent, evidence-based enforcement of environmental and mining regulations. By integrating geofencing, data anonymization, and human-in-the-loop oversight, the framework aligns with both the Ghana Data Protection Act and international AI governance principles, fostering community trust and ethical compliance.

Beyond Ghana, this architecture contributes to broader continental discussions on UAV governance across Africa. As nations work to balance technological innovation with privacy, sovereignty, and ethical data usage, the framework provides a reference model for harmonizing policy, regulation, and accountability in UAV-enabled monitoring systems.

Figure 25 illustrates the Security and Auditability Framework, comprising three interconnected layers:

Communication Security using ChaCha20-Poly1305 and TLS/DTLS over QUIC to maintain confidentiality in UAV communications.

Adversarial Robustness through FGSM/PGD training, strengthening integrity by defending against malicious perturbations and attacks.

Hash-Chained Audit Logs to ensure accountability, creating immutable, verifiable records of UAV activities for compliance and regulatory review.

These layers collectively safeguard data flow, operational decisions, and enforcement mechanisms, enabling a resilient and ethically sound UAV ecosystem.

Although the focus here is illegal mining in Ghana, the approach generalizes to other applications. Forecasting combined with resilient communication can accelerate disaster response (e.g., wildfires or floods management), support ecological monitoring (e.g., wildlife protection or deforestation prevention), and enhance infrastructure safety (e.g., monitoring of pipelines, dams, or landslides). This positions the framework as a flexible model for crisis management and environmental sustainability across multiple sectors.

Several research directions remain open:

Field validation: Deploying the system in live ASGM corridors to confirm simulation results under real-world conditions.

Model optimization: Developing compression or pruning techniques to enable advanced forecasting models on UAV edge devices.

Community integration: Embedding dispatch protocols within local governance frameworks to balance enforcement with livelihood considerations.

Multi-agent expansion: Scaling to larger UAV swarms equipped with heterogeneous sensors to improve coverage and resilience.

In summary, this discussion underscores that calibrated ML perception, predictive forecasting, and resilient communication are complementary rather than sufficient in isolation. Their integration into the proposed Galamsey-911 framework significantly reduced detection-to-dispatch latency, improved delivery reliability, and enhanced patrol efficiency. These outcomes demonstrate the potential for UAV systems to move beyond observational roles and function as proactive, cooperative responders in challenging rural environments.

VI. Conclusions

Illegal artisanal and small-scale gold mining (“galamsey”) continues to be one of Ghana’s most serious ecological and safety threats, while traditional monitoring approaches remain reactive, fragile under canopy, and limited by unreliable communications. This study introduced the Galamsey-911 framework, a proactive UAV-based surveillance system that integrates calibrated ML perception, multi-layer resilient communications, and spatiotemporal forecasting.

The framework delivered three core contributions: (1) Calibrated Severity Index (C1), reducing calibration error to ≤0.07 while achieving AUROC ≥ 0.92; (2) SLA-aware Communications (C2), sustaining ≥95% reliability with sub-30-second alerts; and (3) Hotspot Forecasting (C3), providing ≥30% lead-time gains and expanding patrol coverage by 36%.

Integrated testing confirmed nearly 30% latency reductions compared to conventional UAV deployments. Beyond galamsey, the framework offers a versatile foundation for disaster response, ecological monitoring, and infrastructure protection. Built-in safeguards geofencing, anonymization, and human oversight ensure compliance with Ghana’s Data Protection Act and international AI governance standards. Future work will focus on field trials in ASGM corridors, lightweight model compression for UAV edge deployment, and embedding dispatch protocols within community governance. By enabling UAVs to progress from passive observers to anticipatory responders, this research advances environmental stewardship and operational resilience in resource-constrained regions.

This research is conceptual and simulation-based. It does not involve human participants or confidential datasets. All references and information are derived from published sources cited herein. Synthetic datasets and simulation scripts generated for modeling UAV communication network design can be made available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Data curation, Writing original draft, review, editing, and Visualization: Mahama Dauda.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Synthetic data and scripts are available on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to the academic community on LinkedIn for generously sharing valuable information, insights, and guidance on various aspects of research writing. We also acknowledge the enriching and diverse learning experiences gained through active engagement in the academic forum of the University of the People, which have significantly contributed to the development of this research. Furthermore, we extend our appreciation for the constructive feedback provided throughout the research process, which has been instrumental in refining this work. The collective support received during the completion of each milestone is deeply valued and sincerely appreciated.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

List of Abbreviations

| Abbreviation |

Definition |

Abbreviation |

Definition |

| 3GPP |

3rd Generation Partnership Project |

MPC |

Model Predictive Control |

| 5G |

Fifth-generation mobile network |

mIoU |

mean Intersection over Union |

| AHP |

Analytic Hierarchy Process |

NDVI |

Normalized Difference Vegetation Index |

| AirSim |

Aerial Informatics and Robotics Simulation |

ns-3 |

Network Simulator 3 |

| AP |

Average Precision |

NSGA-II |

Non-dominated Sorting Genetic Algorithm II |

| AP@50 |

Average Precision at IoU = 0.50 |

ORCA |

Optimal Reciprocal Collision Avoidance |

| AR |

Average Recall |

PDR |

Packet Delivery Ratio |

| ASGM |

Artisanal and Small-Scale Gold Mining |

PGD |

Projected Gradient Descent |

| AUROC |

Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve |

p95 |

95th percentile (e.g., latency) |

| BALD |

Bayesian Active Learning by Disagreement |

QoS |

Quality of Service |

| BVLOS |

Beyond Visual Line of Sight |

QUIC |

Quick UDP Internet Connections |

| CBBA |

Consensus-Based Bundle Algorithm |

RF |

Radio Frequency |

| CAGR |

Compound Annual Growth Rate |

RGB |

Red, Green, Blue (imagery) |

| C1 / C2 / C3 |

Study contributions: C1 = Calibrated Severity Index; C2 = SLA-aware Communications/Dispatcher; C3 = Hotspot Forecasting & Routing |

RMSE |

Root Mean Square Error |

| CDF |

Cumulative Distribution Function |

RQs |

Research Questions |

| ConvLSTM |

Convolutional Long Short-Term Memory |

RRT* |

Rapidly-Exploring Random Tree, optimal variant |

| DCRNN |

Diffusion Convolutional Recurrent Neural Network |

SATCOM |

Satellite Communications |

| DII |

Drone Industry Insights |

SGM |

Small-Scale Gold Mining |

| DTLS |

Datagram Transport Layer Security |

sMAPE |

Symmetric Mean Absolute Percentage Error |

| DTN |

Delay-Tolerant Networking |

SLA |

Service Level Agreement |

| DVRPTW |

Dynamic Vehicle Routing Problem with Time Windows |

T-GCN |

Temporal Graph Convolutional Network |

| ECE |

Expected Calibration Error |

TFT |

Temporal Fusion Transformer |

| FANET |

Flying Ad Hoc Network |

TOPSIS |

Technique for Order Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution |

| FGSM |

Fast Gradient Sign Method |

UAV / UAVs |

Unmanned Aerial Vehicle(s) |

| FBI |

Fortune Business Insights |

USD |

United States Dollar |

| GCAA |

Ghana Civil Aviation Authority |

V2V |

Vehicle-to-Vehicle communication |

| GNN / GNNs |

Graph Neural Network(s) |

WiLDNet |

Wi-Fi Long-Distance Network |

| Grad-CAM |

Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping |

YOLO / YOLOv8 |

You Only Look Once (object detection models) |

| GIS |

Geographic Information System |

|

|

References

- 3GPP. Enhanced LTE Support for Aerial Vehicles (3GPP TR 36.777). 2017.

- Ali, S.; Khan, A.; Muhammad, T.; et al. A2G propagation modeling for UAV in mountainous regions at 5G frequencies. Drones 2024, 8, 18. [Google Scholar]

- Ball, J.; Smith, A.; Jones, R. Ecological risk mapping with spatiotemporal deep learning. Ecol. Inform. 2022, 67, 101530. [Google Scholar]

- Basu, A.; Basu, S.; Roy, P.S.; et al. Modeling spatial patterns of deforestation using deep learning. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2021, 12, 2202–2214. [Google Scholar]

- Boadi, S.; Nsor, C.A.; Antobre, O.O.; Acquah, E. Illegal mining on Offin shelterbelt—Implications. J. Sustain. Min. 2016, 15, 115–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacciuttolo, C.; Guzmán, V.; Catriñir, P.; Atencio, E. Sensors for tailings safety. Minerals 2024, 14, 446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camalan, H.; Santos, R.; Silva, M. Monitoring Amazonian mining via remote sensing. RSE 2022, 272, 112908. [Google Scholar]

- Chandran, A.; Basnet, S.; Garcia, M. Multi-UAV networks for disaster monitoring. Drone Syst. Appl. 2024, 3, 100015. [Google Scholar]

- Chandran, A.; Rajkumar, R.; Wolf, T. Digital twins reputation for microchain UAVs. In Proc. IEEE CloudNet 2023; pp. 428–432.

- Chen, L.-C.; Zhu, Y.; Papandreou, G.; Schroff, F.; Adam, H. Encoder–decoder with atrous separable conv. In ECCV 2018; pp. 801–818.

- Choi, H.L.; Brunet, L.; How, J.P. Consensus-based decentralized auctions. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2009, 25, 912–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davoli, R.; Conti, M.; Passarella, A. Opportunistic UAV mesh swarming. Ad Hoc Netw. 2021, 117, 102503. [Google Scholar]

- Deb, K.; Pratap, A.; Agarwal, S.; Meyarivan, T. NSGA-II. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 2002, 6, 182–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Z.; Savkin, A.V. Strategies for optimized UAV surveillance. Drones 2024, 8, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forkuor, G.; Mireku, B.; Asare, S. Sentinel-1 SAR change detection (Ghana). IJAEOG 2020, 92, 102178. [Google Scholar]

- Gallwey, J.; Wilson, A.; Baker, S. Detecting small-scale mining (Ghana). RSASE 2020, 18, 100322. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, C.; Pleiss, G.; Sun, Y.; Weinberger, K.Q. On calibration of modern neural networks. In Proc. ICML 2017; PMLR 70:1321–1330.

- He, K.; Gkioxari, G.; Dollár, P.; Girshick, R. Mask R-CNN. In ICCV 2017; pp. 2961–2969.

- Henderson, T.R.; Lacage, M.; Riley, G.F.; Dowell, C.; Kopena, J. ns-3 simulator. In Modeling and Tools for Network Simulation; Springer, 2010; pp. 15–34.

- Houlsby, N.; Huszár, F.; Ghahramani, Z.; Lengyel, M. Bayesian active learning. arXiv 2011, arXiv:1112.5745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaman, S.; Frazzoli, E. Optimal motion planning (RRT*). Int. J. Robot. Res. 2011, 30, 846–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendall, A.; Gal, Y. What uncertainties do we need in BDL for CV? arXiv 2017, arXiv:1703.04977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X. Networked UAVs survey. Future Internet 2021, 13, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, B.; Arık, S.Ö.; Loeff, N.; Pfister, T. Temporal Fusion Transformers. Int. J. Forecast. 2021, 37, 1748–1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Wiren, R.; Euler, S.; et al. 3GPP perspective on UAV comms. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2017, 55, 218–225. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, X.; Yajnanarayana, V.; Muruganathan, S.D.; et al. LTE for UAVs. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2018, 56, 204–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Zhang, W.; Lian, H.; et al. Insulator detection with YOLOv4. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 723. [Google Scholar]

- Madridano, Á.; Al-Kaff, A.; Gómez, D.M.; de la Escalera, A. Multi-path planning for swarms. In IEEE ICVES 2019; pp. 1–6.

- Malczewski, J. GIS-based MCDA survey. IJGIS 2006, 20, 703–726. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, L.; Chen, C.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Excavator detection for pipeline safety. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullapudi, A.; Bartos, M.; Wong, B.; Kerkez, B. Real-time stormwater control. Sensors 2018, 18, 2259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muruganathan, S.; Lin, X.; Määttänen, H.; Zou, Z. UAV-aided aerial comms. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 67853–67865. [Google Scholar]

- Nunoo, C.; Nsiah-Gyabaah, M.; Foli, K.; et al. Detecting galamsey in Ghana. Heliyon 2022, 8, e11669. [Google Scholar]

- Obodai, J.; Anokye, K.; Addae, A. Land-use change in Ankobra basin. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2019, 191, 726. [Google Scholar]

- Psaraftis, H.N.; Wen, M.; Kontovas, C.A. Dynamic vehicle routing. Networks 2016, 67, 3–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redmon, J.; Farhadi, A. YOLOv3. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1812.10968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvaraju, R.R.; Cogswell, M.; Das, A.; et al. Grad-CAM. In ICCV 2017; pp. 618–626.

- Sener, O.; Savarese, S. Core-set active learning. In ICLR 2018.

- Shah, S.; Dey, D.; Lovett, C.; Kapoor, A. AirSim. In Field and Service Robotics; Springer, 2018; pp. 621–635.

- Shi, X.; Chen, Z.; Wang, H.; et al. ConvLSTM. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1506.04214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsachouridis, S.; Pavloudakis, F.; Sachpazis, C.; Tsioukas, V. UAVs for slope stability. Land 2025, 14, 1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Berg, J.; Guy, S.J.; Lin, M.; Manocha, D. Reciprocal n-body collision avoidance. In Robotics Research; Springer, 2011; pp. 3–19.

- Wang, J.J.; Li, J.; Gao, H.; Li, Z. AHP–TOPSIS for UAV mission prioritization. Int. J. Adv. Robot. Syst. 2020, 17, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, Z.; Song, L.; Wang, X. Spectrum sharing between UAV mesh and ground networks. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2309.07984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Liu, M. DRL to keep collaborative UAVs in touch. In IJCAI 2018; pp. 562–568.

- Yu, B.; Yin, H.; Zhu, Z. ST-GCN. In IJCAI 2018; pp. 3634–3640.

- Zhao, X.; Yang, R.; Zhong, L.; Hou, Z. Multi-UAV path planning via MARL. Drones 2024, 8, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Lai, T.; Yu, H.; Lan, X. Temporal-logic safe planning. IEEE T-ASE 2023, 20, 846–858. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y.; Li, C.; Yang, W. Eco-environmental effects of open-pit mining. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yu, R.; Shahabi, C.; Liu, Y. Diffusion Convolutional Recurrent Neural Network: Data-Driven Traffic Forecasting. In ICLR 2018 (OpenReview).

- Zhao, L.; Song, Y.; Zhang, C.; Liu, Y.; Wang, P.; Lin, T.; Deng, M.; Li, H. T-GCN: A Temporal Graph Convolutional Network for Traffic Prediction. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 150780–150790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jocher, G.; Chaurasia, A.; Stoken, A.; et al. Ultralytics YOLOv8. Tech. Rep. 2023 (Ultralytics).

- Bandara, W.G.C.; Patel, V.M. ChangeFormer: A Transformer-Based Architecture for Change Detection. In CVPR Workshops 2022.

- Raman, B.; Chebrolu, K. Experiences in Using WiFi for Rural Internet in India. In Proc. ACM MobiSys 2005; pp. 176–189.

- Hewing, L.; Wabersich, K.P.; Menner, M.; Zeilinger, M.N. Learning-based Model Predictive Control: Toward Safe Learning in Control. Annu. Rev. Control 2020, 50, 100–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Representative UAV applications across multiple domains.

Figure 1.

Representative UAV applications across multiple domains.

Figure 2.

Mining-Aligned UAVs: Manufacturers and Features by Altitude.

Figure 2.

Mining-Aligned UAVs: Manufacturers and Features by Altitude.

Figure 7.

Severity Index framework. The fusion pipeline combines detection confidence, collapse probability, NDVI, slope, and uncertainty penalties into calibrated risk scores bounded in [0,1], categorized as High, Medium, or Monitor.

Figure 7.

Severity Index framework. The fusion pipeline combines detection confidence, collapse probability, NDVI, slope, and uncertainty penalties into calibrated risk scores bounded in [0,1], categorized as High, Medium, or Monitor.

Figure 8.

Reliability diagram comparing pre- and post-calibration outputs. Post-calibration curves approach the diagonal, indicating improved calibration and reduced expected calibration error (ECE).

Figure 8.

Reliability diagram comparing pre- and post-calibration outputs. Post-calibration curves approach the diagonal, indicating improved calibration and reduced expected calibration error (ECE).

Figure 9.

Galamsey-911 Dispatch Workflow. SLA-aware communication hierarchy shows LTE primary, mesh secondary, and SATCOM tertiary failover with acknowledgment timers and QoS-based alert topics.

Figure 9.

Galamsey-911 Dispatch Workflow. SLA-aware communication hierarchy shows LTE primary, mesh secondary, and SATCOM tertiary failover with acknowledgment timers and QoS-based alert topics.

Figure 19.

Fairness Comparison of AUROC and ECE Across Canopy Density Groups.

Figure 19.

Fairness Comparison of AUROC and ECE Across Canopy Density Groups.

Figure 22.

illustrates the three core contributions of the framework: Calibrated Severity Index (C1), SLA-aware Communications (C2), and Hotspot Forecasting (C3). Each achieved its target performance metric.

Figure 22.

illustrates the three core contributions of the framework: Calibrated Severity Index (C1), SLA-aware Communications (C2), and Hotspot Forecasting (C3). Each achieved its target performance metric.

Figure 23.

compares latency performance between conventional UAV deployments and the proposed framework. Integrated testing confirmed a nearly 30% latency reduction, demonstrating the efficiency of the SLA-aware dispatch and forecasting system.

Figure 23.

compares latency performance between conventional UAV deployments and the proposed framework. Integrated testing confirmed a nearly 30% latency reduction, demonstrating the efficiency of the SLA-aware dispatch and forecasting system.

Figure 25.

Security and Auditability Framework. The framework ensures confidentiality, integrity, and accountability through secure communication, adversarial robustness, and immutable audit logs.

Figure 25.

Security and Auditability Framework. The framework ensures confidentiality, integrity, and accountability through secure communication, adversarial robustness, and immutable audit logs.

Table 1.

Comparative UAV and AV Market Growth (2020–2035).

Table 1.

Comparative UAV and AV Market Growth (2020–2035).

| Category |

Growth Basis |

CAGR % |

Start Value (USD billions) |

End Value (USD billions) |

| UAVs (2020–2024) |

Historical (DII) |

15.0 |

20.65 |

36.09 |

| UAVs (2024–2030) |

Projected (DII) |

7.1 |

36.09 |

54.46 |

| UAVs (2020–2035) |

Long-term extrapolation |

9.1 |

20.65 |

76.75 |

| AVs (2020–2024) |

Historical (FBI) |

12.2 |

1.45 |

2.30 |

| AVs (2024–2032) |

Projected (FBI) |

42.3 |

2.30 |

38.62 |

| AVs (2020–2035) |

Long-term extrapolation |

33.6 |

1.45 |

111.29 |

Table 2.

summarizes the calibration performance across models.

Table 2.

summarizes the calibration performance across models.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).