Submitted:

01 October 2025

Posted:

02 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

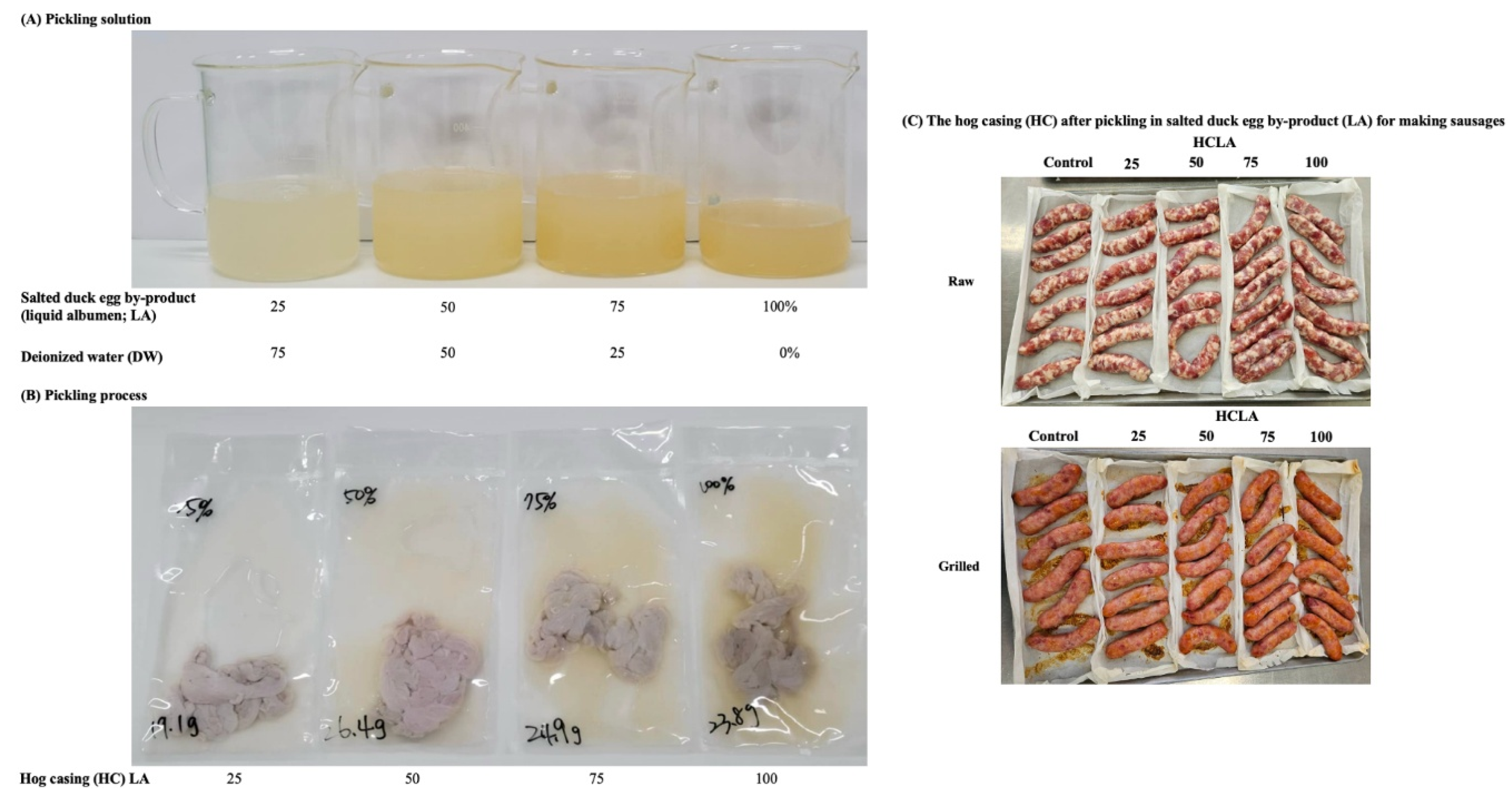

2.2. Processing of Samples and Pickling Solutions

2.2.1. Desalting of Commercially Available Salted HC

2.2.2. Processing of Pickling Solution

2.2.3. Pickling Process

2.2.4. Preparation of Chinese Sausages

2.3. Proximate Analysis

2.4. Determination of Salted HC Appearance Color

2.5. TPA

2.6. Aroma Analysis

2.7. Sensory Evaluation

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Physicochemical Properties of the Sausage

3.1.1. Moisture Content

3.1.2. AW

3.1.3. Appearance Color

3.1.4. TPA

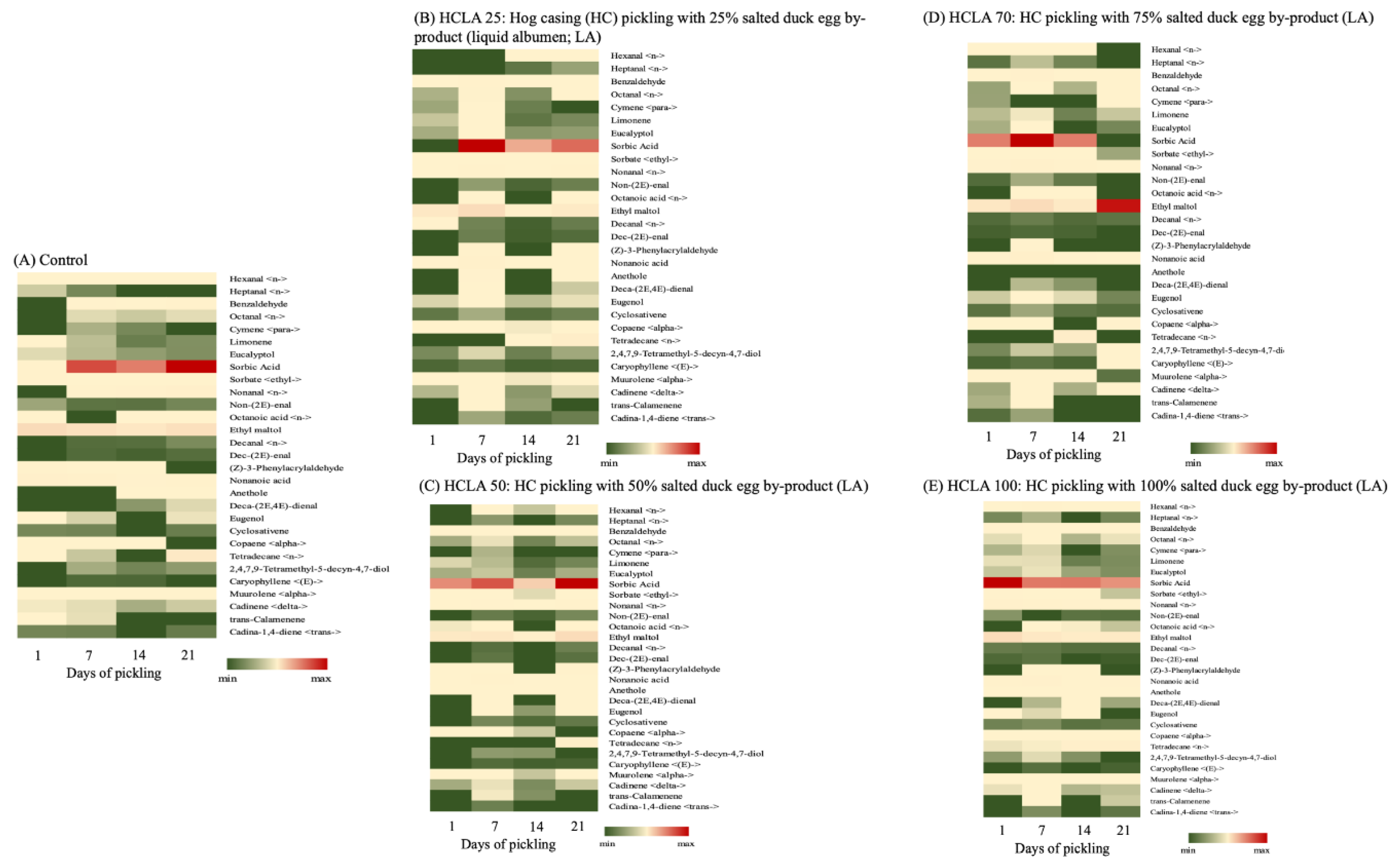

3.1.5. Aroma Heat-Map Analysis

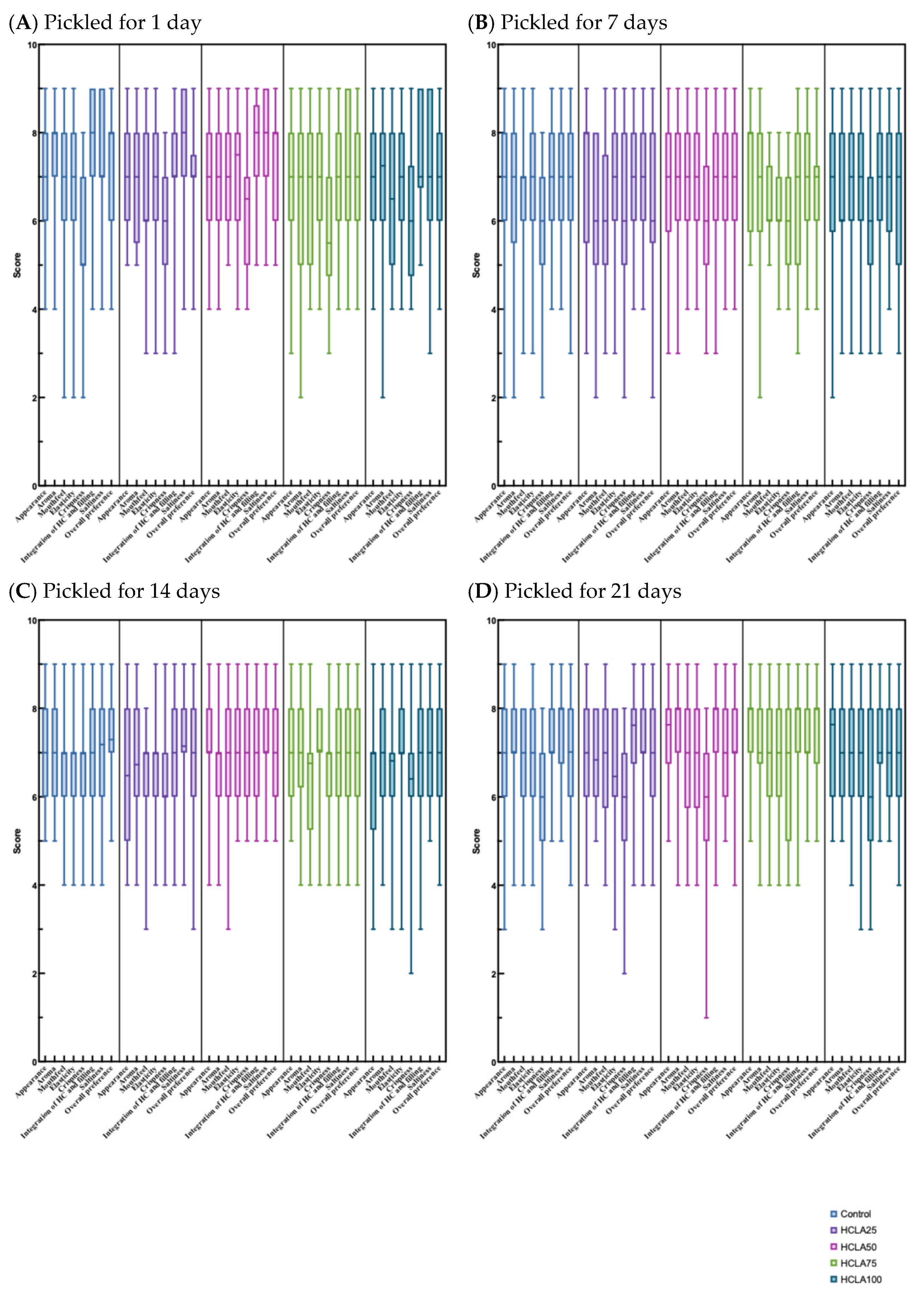

3.2. Sensory Evaluation

3.3. Proximate Composition

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LA | Liquid albumen |

| HC | Hog casing |

| TPA | Textural profile analysis |

| CAGR | Conservative compound annual growth rate |

| DW | Deionized water |

| AW | Water activity |

| N | Newton |

| SPME | Solid-phase microextraction |

| DVB/PDMS | Divinylbenzene/polydimethylsiloxane |

| GC-MS | Gas chromatography–mass spectrometry |

| RI | Retention index |

| NIST | National Institute of Standards and Technology |

| FFNSC | Flavors/fragrances |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| ANOVA | Analysis of variance |

| WVP | Water vapor permeability |

| MR | Maillard reaction |

| Phe | Phenylalanine |

| ED2 | 3,4′-di-O-butanoylresveratrol |

| ED4 | 3-O-butanoylresveratrol |

Appendix A

| Ingredient | Weight | Ratio | |

| (g) | (%) | ||

| Lean pork | 20000 | 69.79 | |

| Back fat | 5000 | 17.45 | |

| Seasonings | Salt | 358.3 | 1.25 |

| Sugar | 2278.47 | 7.95 | |

| Monosodium glutamate (MSG) |

126.1 | 0.44 | |

| Five-spice powder | 11.5 | 0.04 | |

| White pepper | 74.5 | 0.26 | |

| Cooking rice wine | 753.8 | 2.63 | |

| Polyphosphate | 51.6 | 0.18 | |

| Sodium nitrite | 2.5 | 0.01 | |

| Total | 28656.77 | 100 | |

| Item | Control | HCs pickled in 50% salted duck egg by-product (LA) for 7 days HCLA50 |

|||

| Each serving (40 g) | Per 100 g | Each serving (40 g) | Per 100 g | ||

| Calories (kcal) | 115.8 | 289.6 | 130.5 | 326.3 | |

| Protein (g) | 5.5 | 13.7 | 5.2 | 13.1 | |

| Fat (g) | 9.3 | 23.3 | 14.4 | 28.6 | |

| Saturated fat (g) | 3.5 | 8.6 | 4.4 | 11.1 | |

| Trans fat (g) | 0 | ||||

| Carbohydrate (g) | 2.5 | 6.2 | 1.7 | 4.3 | |

| Sugar (g) | 2.6 | 6.5 | 2.4 | 6 | |

| Sodium (g) | 235 | 587 | 214 | 535 | |

| The proximate analyses were conducted just once (n = 1). Consequently, no statistical analyses were carried out. | |||||

References

- DiMarket. “Salted duck egg analysis uncovered: Market drivers and forecasts 2025-2033.” Pune, Maharashtra: PRDUA Research & Media Private Limited, 2025. https://www.datainsightsmarket.com/reports/salted-duck-egg-1236257#segments (accessed on 8th Aug 2025). (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- Wongnen, C., W. Panpipat, N. Saelee, S. Rawdkuen, L. Grossmann and M. Chaijan. “A novel approach for the production of mildly salted duck egg using ozonized brine salting.” Foods 12 (2023): 2261. [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y., N. Wu, Y. Yao, S. Chen, L. Xu, Y. Zhao and Y. Tu. “Effects of ammonium chloride on physicochemical properties, aggregation behavior and microstructure of duck egg yolk induced by salt.” LWT 229 (2025): 118151. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.-C. Y.-C. Chen and J.-W. Chen. “The current production and export situation of the duck egg industry in taiwan.” FFTC Agricultural Policy Platform (FFTC-AP), 2025. https://ap.fftc.org.tw/article/3766 (accessed on 7th Aug 2025). (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- Wang, X., J. Zhang, S. K. Vidyarthi, M. Xu, Z. Liu, C. Zhang and H. Xiao. “A comprehensive review on salted eggs: Quality formation mechanisms, innovative pickling technologies and value-added applications.” Sustainable Food Technology 2 (2024): 1409–27. [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y., W. Lu, P. Zalewski, J. He, X. Li, Y. Cao, Y. Zhao, C. Sun, J. Wu, H. Chen, et al. “Innovative approaches to sodium reduction in pickled foods: A review of recent developments.” Trends in Food Science & Technology 163 (2025): 105133. [CrossRef]

- Suurs, P. and S. Barbut. “Collagen use for co-extruded sausage casings – A review.” Trends in Food Science & Technology 102 (2020): 91–101. [CrossRef]

- Global-Market-Insights. “Sausage casings market size.” Selbyville, USA: Global Market Insights Inc., 2023. https://www.gminsights.com/industry-analysis/sausage-casings-market (accessed on 8th Aug 2025). (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- Anuradha. Natural sausage casings market research report 2033. Ontario, USA: 2024, 288. https://growthmarketreports.com/report/natural-sausage-casings-market (accessed on 8th Aug 2025).

- Venugopal, V. “Green processing of seafood waste biomass towards blue economy.” Current Research in Environmental Sustainability 4 (2022): 100164. [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.-H. Y.-T. Huang, J.-Y. Ciou, C.-M. Cheng, G.-T. Wang, C.-M. You, P.-H. Huang and C.-Y. Hou. “Circular economy and sustainable recovery of Taiwanese tilapia (Oreochromis mossambicus) byproduct—the large-scale production of umami-rich seasoning material application.” Foods 12 (2023): 1921. [CrossRef]

- Huang, P.-H. Y.-W. Chen, C.-H. Chen, H.-J. Fan, C.-W. Hsieh, Y.-L. Tain, W.-T. Tsai, M.-K. Shih and C.-Y. Hou. “Characterization and evaluation of the adsorption of uremic toxins through the pyrolysis of pineapple leaves and peels and by forming a bio-complex with sodium alginate.” International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 302 (2025): 138843. [CrossRef]

- Chung, P.-L. K.-S. Lufaniyao and M. Gavahian. “Development of chinese-style sausage enriched with djulis (chenopodium formosanum koidz) using taguchi method: Applying modern optimization to indigenous people’s traditional food.” Foods 13 (2024): 91. [CrossRef]

- Huang, P.-H. Y.-W. Chen, C.-K. Shie, S.-Y. Chen, B.-H. Lee, L.-J. Yin, C.-Y. Hou and M.-K. Shih. “Chinese sausage simulates high calorie–induced obesity in vivo, identifying the potential benefits of weight loss and metabolic syndrome of resveratrol butyrate monomer derivatives.” Journal of Nutrition and Metabolism 2025 (2025): 8414627. [CrossRef]

- AOAC. “Official methods of analysis: 22nd edition (2023).” In Official methods of analysis of aoac international. G. W. Latimer, Jr. and G. W. Latimer, Jr. Oxford University Press, 2023.

- Lin, Y.-W. C.-L. Tsai, C.-J. Chen, P.-L. Li and P.-H. Huang. “Insights into the effects of multiple frequency ultrasound combined with acid treatments on the physicochemical and thermal properties of brown rice postcooking.” LWT (2023): 115423. [CrossRef]

- Huang, P.-H., Y. Y. Wu, P.-H. Huang, C.-M. Lin, H.-L. Chen, M.-H. Chen, M.-K. Shih and C.-Y. Hou. “Characterization of the effects of micro-bubble treatment on the cleanliness of intestinal sludge, physicochemical properties, and textural quality of shrimp (litopenaeus vannamei).” Food Chemistry (2025): 142909. [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.-H. P.-H. Huang, C.-Y. Lo and W.-C. Chang. “Metabolomic analysis elucidates the dynamic changes in aroma compounds and the milk aroma mechanism across various portions of tea leaves during different stages of oolong tea processing.” Food Research International 209 (2025): 116203. [CrossRef]

- Huang, P.-H. Y.-W. Chen, H.-J. Fan, S.-Y. Chen, Y.-L. Tain, C.-W. Hsieh, C.-Y. Hou and M.-K. Shih. “Application of resveratrol butyric acid derivatives in the processing, physicochemical characterization, and the shelf-life extension of chinese sausages low in sodium nitrite.” Journal of Food Safety 44 (2024): e13144. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., J. Jia, Q. Qian, H. Ma, J. Zhou, Y. Lin, P. Zhang, Q. Chen, Q. Zeng, Q. Li, et al. “Effect of isolated bacteria on nitrite degradation and quality of sichuan dry sausages.” LWT 212 (2024): 117039. [CrossRef]

- Guan, D., X. Yang, J. Tao, F. Zhan, Y. Qiu, J. Jin and L. Zhao. “Novel biodegradable polyamide 4/chitosan casing films for enhanced fermented sausage packaging.” Food Packaging and Shelf Life 47 (2025): 101444. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y., M. Mijiti, Z. Xu and B. Abulikemu. “Effect of a combination of probiotics on the flavor profiling and biogenic amines of composite fermented mutton sausages.” Food Bioscience 61 (2024): 104835. [CrossRef]

- Seibt, A. C. M. D., P. Nerhing, M. B. Pinton, S. P. Santos, Y. S. V. Leães, F. D. C. De Oliveira, S. S. Robalo, B. C. Casarin, B. A. Dos Santos, J. S. Barin, et al. “Green technologies applied to low-nacl fresh sausages production: Impact on oxidative stability, color formation, microbiological properties, volatile compounds, and sensory profile.” Meat Science 209 (2024): 109418. [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y., Y. Yuan, J.-X. Chen, S.-Y. Chen, C.-H. Li, Y. Huang and H.-J. Chang. “Quality properties of chinese sichuan-style sausages as affected by chinese red wine, yellow rice wine and beer.” International Journal of Food Properties 26 (2023): 3291–304. [CrossRef]

- Huang, J., H. Wei, Z. Luo, L. Li, Z. Liu and N. Xie. “Enhancing the textural properties of tibetan pig sausages via zanthoxylum bungeanum aqueous extract: Polyphenol-mediated quality improvements.” Foods 14 (2025): 1639. [CrossRef]

- Huang, R., Y. Fang, H. Yin, Y. Zhong, W. Lu and Y. Deng. “Al-optimized synergy of kcl and κ-carrageenan in low-sodium sausages: Integrated enhancement of saltiness perception, gel stability, and protein digestibility.” Food Hydrocolloids 168 (2025): 111574. [CrossRef]

- Karla dos Santos, A., N. Marques da Silva, M. A. Matiucci, A. Rech de Marins, T. A. Ferreira de Campos, L. Waleska de Brito Sodré, R. A. Dias Bezerra, C. R. Alcalde and A. C. Feihrmann. “Use of encapsulated açaí oil with antioxidant potential in fresh sausage.” LWT 204 (2024): 116469. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J., X. Li, B. Kong, C. Cao, F. Sun, H. Zhang and Q. Liu. “Application of lysine as a potential alternative to sodium salt in frankfurters: With emphasis on quality profile promotion and saltiness compensation.” Meat Science 217 (2024): 109609. [CrossRef]

- Dong, Z., L. Wang, Y. Ge, Y. An, X. Sun, K. Xue, H. Xie, R. Wang, J. Li and L. Chen. “Screening, identification, and application of superior starter cultures for fermented sausage production from traditional meat products.” Fermentation 11 (2025): 306. [CrossRef]

- Xu, B., W. Qiu, Y. Liu, F. Gong, Q. Liu, J. Chen, Y. Tang, C. Su, J. Tang, D. Zhang, et al. “Exploring the regulation of metabolic changes mediated by different combined starter cultures on the characteristic flavor compounds and quality of sichuan-style fermented sausages.” Food Research International 208 (2025): 116114. [CrossRef]

- Feng, T., R. Ye, H. Zhuang, Z. Rong, Z. Fang, Y. Wang, Z. Gu and Z. Jin. “Physicochemical properties and sensory evaluation of mesona blumes gum/rice starch mixed gels as fat-substitutes in chinese cantonese-style sausage.” Food Research International 50 (2013): 85–93. [CrossRef]

- Sriwattana, S., N. Chokumnoyporn and W. Prinyawiwatkul. “Reduced-sodium vienna sausage: Selected quality characteristics, optimized salt mixture, and commercial scale-up production.” Journal of Food Science 86 (2021): 3939–50. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, P., Y. An, Z. Dong, X. Sun, W. Zhang, H. Wang, B. Yang, J. Yan, B. Fang, F. Ren, et al. “Comparative analysis of commercially available flavor oil sausages and smoked sausages.” Molecules 29 (2024): 3772. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q., J. Shen, G. Meng, C. Liu, H. Wang, Q. Zhang, C. Zhu, G. Zhao and X. Wang. “Characterization of wheat bran nanocellulose and its application in low-fat emulsified sausage.” Cellulose 31 (2024): 11101–14. [CrossRef]

- He, W., Z. Liu, H. Liu, J. Sun, H. Chen and B. Sun. “Characterization of key volatile flavor compounds in dried sausages by hs-spme and safe, which combined with GC-MS, GC-O and OAV.” Journal of Food Composition and Analysis 133 (2024): 106438. [CrossRef]

- Bleicher, J., E. E. Ebner and K. H. Bak. “Formation and analysis of volatile and odor compounds in meat—a review.” Molecules 27 (2022): 6703. [CrossRef]

- Cai, X., Y. Zeng, K. Zhu, Y. Peng, P. Xv, P. Dong, M. Qiao and W. Fan. “Characterization of the quality and flavor in Chinese sausage: Comparison between cantonese, five-spice, and mala sausages.” Foods 14 (2025): 1982. [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y., J. Wang, Q. Liu, Y. Wang, J. Ren, Q. Chen and B. Kong. “Unraveling the difference in flavor characteristics of dry sausages inoculated with different autochthonous lactic acid bacteria.” Food Bioscience 47 (2022): 101778. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H., B. Zhao, S. Zhang, Q. Wu, N. Zhu, S. Li, X. Pan, S. Wang and X. Qiao. “Development of volatiles and odor-active compounds in Chinese dry sausage at different stages of process and storage.” Food Science and Human Wellness 10 (2021): 316–26. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X., F. Yan, D. Qu, T. Wan, L. Xi and C. Y. Hu. “Aroma characterization of Sichuan and Cantonese sausages using electronic nose, gas chromatography–mass spectrometry, gas chromatography-olfactometry, odor activity values and metagenomic.” Food Chemistry: X 24 (2024): 101924. [CrossRef]

- Mei, L., D. Pan, T. Guo, H. Ren and L. Wang. “Role of lactobacillus plantarum with antioxidation properties on Chinese sausages.” LWT 162 (2022): 113427. [CrossRef]

- Xia, L., M. Qian, F. Cheng, Y. Wang, J. Han, Y. Xu, K. Zhang, J. Tian and Y. Jin. “The effect of lactic acid bacteria on lipid metabolism and flavor of fermented sausages.” Food Bioscience 56 (2023): 103172. [CrossRef]

- Xing, B., T. Zhou, H. Gao, L. Wu, D. Zhao, J. Wu and C. Li. “Flavor evolution of normal- and low-fat Chinese sausage during natural fermentation.” Food Research International 169 (2023): 112937. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T., B. Sheng, H. Gao, X. Nie, H. Sun, B. Xing, L. Wu, D. Zhao, J. Wu and C. Li. “Effect of fat concentration on protein digestibility of Chinese sausage.” Food Research International 177 (2024): 113922. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.-s. C.-y. Wang, Y.-y. Hu, L. Yang and B.-c. Xu. “Enhancement of fermented sausage quality driven by mixed starter cultures: Elucidating the perspective of flavor profile and microbial communities.” Food Research International 178 (2024): 113951. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., C. Lv, P. Zhang, F. Wang, T. Zhang, Y. Ma and M. Xu. “Formulation optimization and quality evaluation of walnut protein sausage based on fuzzy mathematics sensory evaluation combined with random centroid optimization.” Food Science & Nutrition 13 (2025): e70747. [CrossRef]

| Analysis | Days of pickling | Control (commercially available salted HC) |

HCLA | ||||

| LA concentration (%) |

25 | 50 | 75 | 100 | |||

| Deionized water (DW; %) |

75 | 50 | 25 | 0 | |||

| Moisture content (%) | 1 | 34.49 ± 2.58ᵃ | 30.71 ± 0.09ᵇ | 33.26 ± 1.33ᵃᵇ | 27.73 ± 1.28ᶜᵈ | 26.36 ± 2.95ᵈ | |

| 7 | 33.97 ± 1.60ᵃ | 34.91 ± 1.35ᵃ | 36.37 ± 4.15ᵃ | 32.17 ± 2.34ᵃ | 33.76 ± 1.34ᵃ | ||

| 14 | 41.19 ± 3.42ᵃᵇ | 38.69 ± 3.84ᵃᵇ | 44.34 ± 2.25ᵃ | 38.30 ± 4.09ᵇ | 36.62 ± 1.82ᵇ | ||

| 21 | 34.71 ± 8.10ᵃ | 29.65 ± 0.46ᵃ | 22.57 ± 5.78ᵃ | 29.30 ± 2.81ᵃ | 31.14 ± 3.75ᵃ | ||

| Water activity (AW) | 1 | 0.92 ± 0.01ᵇ | 0.93 ± 0.01ᵃᵇ | 0.94 ± 0.01ᵃ | 0.94 ± 0.00ᵃ | 0.94 ± 0.00ᵃ | |

| 7 | 0.94 ± 0.01ᵃ | 0.94 ± 0.01ᵃ | 0.94 ± 0.00ᵃ | 0.94 ± 0.00ᵃ | 0.95 ± 0.00ᵃ | ||

| 14 | 0.96 ± 0.01ᵃ | 0.95 ± 0.01ᵃ | 0.96 ± 0.00ᵃ | 0.95 ± 0.01ᵃ | 0.96 ± 0.00ᵃ | ||

| 21 | 0.93 ± 0.01b | 0.94 ± 0.01ᵃᵇ | 0.93 ± 0.01b | 0.94 ± 0.01ᵇᶜ | 0.95 ± 0.00ᵃ | ||

| L* | 1 | 51.40 ± 0.46ᵈ | 54.43 ± 0.15ᶜ | 58.60 ± 0.10ᵃ | 55.33 ± 0.42ᵇ | 48.23 ± 0.21ᵉ | |

| 7 | 50.67 ± 0.29ᶜ | 51.43 ± 0.15ᵇ | 51.80 ± 0.10ᵃ | 50.13 ± 0.15ᵈ | 51.27 ± 0.15ᵇ | ||

| 14 | 53.57 ± 0.46ᵇ | 49.23 ± 0.32ᵈ | 50.60 ± 0.26ᶜ | 50.33 ± 0.29ᶜ | 54.53 ± 0.15ᵃ | ||

| 21 | 42.27 ± 0.21ᵃ | 46.63 ± 0.29ᵇ | 45.43 ± 0.12ᶜ | 48.90 ± 0.46ᵈ | 39.27 ± 0.46ᵉ | ||

| a* | 1 | 9.60 ± 0.89ᵇ | 7.90 ± 0.56ᶜ | 6.87 ± 0.95ᶜ | 7.80 ± 0.98ᶜ | 12.27 ± 1.02ᵃ | |

| 7 | 9.57 ± 1.10ᵇ | 8.53 ± 1.00ᵇ | 10.33 ± 0.78ᵇ | 13.37 ± 1.10ᵃ | 9.23 ± 1.85ᵇ | ||

| 14 | 7.40 ± 0.62ᵇ | 9.67 ± 0.55ᵃ | 8.63 ± 0.57ᵃᵇ | 8.10 ± 1.44ᵇ | 4.07 ± 0.06ᶜ | ||

| 21 | 11.70 ± 1.18ᵃᵇ | 10.10 ± 1.31ᵇ | 13.13 ± 0.65ᵃ | 10.20 ± 2.26ᵇ | 12.80 ± 0.20ᵃᵇ | ||

| b* | 1 | 15.50 ± 1.91ᵃᵇ | 12.37 ± 3.29ᵇ | 20.73 ± 1.12ᵃ | 21.20 ± 3.51ᵃ | 15.27 ± 3.07ᵇ | |

| 7 | 13.43 ± 1.80ᵇ | 13.90 ± 1.37ᵇ | 15.77 ± 2.61ᵇ | 23.87 ± 0.55ᵃ | 20.63 ± 6.61ᵃᵇ | ||

| 14 | 13.87 ± 1.97ᵃᵇ | 17.73 ± 2.51ᵃ | 16.97 ± 4.97ᵃᵇ | 19.73 ± 1.60ᵃ | 11.73 ± 0.45ᵇ | ||

| 21 | 18.00 ± 4.07ᵃ | 13.47 ± 2.27ᵇ | 18.93 ± 1.50ᵃ | 16.97 ± 1.90ᵃᵇ | 18.53 ± 0.60ᵃ | ||

| All group data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD; n=3). Different superscripted lowercase letters (p< 0.05) in groups of the same pickling day indicated significant differences. | |||||||

| Analysis | Days of pickling | Control (commercially available salted HCs) |

HCLA | ||||

| LA concentration (%) | 25 | 50 | 75 | 100 | |||

| Deionized water (DW; %) |

75 | 50 | 25 | 0 | |||

| Hardness (Newton; N) |

1 | 123.58 ± 22.75ᵃᵇ | 84.71 ± 9.34ᵈ | 115.22 ± 8.08ᵇᶜ | 146.03 ± 19.25ᵃ | 106.05 ± 6.82ᶜᵈ | |

| 7 | 72.59 ± 5.38ᵇ | 130.22 ± 34.57ᵃ | 84.79 ± 6.69ᵃb | 72.86 ± 7.25ᵇ | 74.28 ± 6.62ᵇ | ||

| 14 | 104.13±13.23ᵇ | 64.95±7.36ᶜ | 142.36±16.26ᵃ | 128.73±8.00ᵃᵇ | 60.27±3.87ᶜ | ||

| 21 | 105.74±12.07ᵇᶜ | 95.78±6.21ᶜ | 103.62±2.17ᵇᶜ | 139.72±17.97ᵃ | 127.20±14.97ᵃᵇ | ||

| Springiness | 1 | 0.78 ± 0.05ᵇ | 0.89 ± 0.03ᵃᵇ | 0.93 ± 0.03ᵃ | 0.84 ± 0.14ᵃᵇ | 0.46 ± 0.04ᶜ | |

| 7 | 0.57 ± 0.02ᵇᶜ | 0.65 ± 0.08ᵇᶜ | 0.93 ± 0.10ᵃᵇ | 1.02 ± 0.35ᵃ | 0.41 ± 0.06ᶜ | ||

| 14 | 0.47±0.08ᵃᵇ | 0.53±0.03ᵃ | 0.45±0.05ᵇ | 0.48±0.03ᵃᵇ | 0.34±0.05ᶜ | ||

| 21 | 0.26±0.01ᶜ | 0.42±0.11ᵇ | 0.44±0.04ᵇ | 0.56±0.05ᵃ | 0.50±0.02ᵃᵇ | ||

| Cohesiveness | 1 | 0.24 ± 0.08ᵇ | 0.54 ± 0.18ᵃ | 0.40 ± 0.03ᵃᵇ | 0.51 ± 0.12ᵃ | 0.34 ± 0.09ᵃᵇ | |

| 7 | 0.27 ± 0.10ᵇ | 0.58 ± 0.13ᵃ | 0.38 ± 0.19ᵃᵇ | 0.60 ± 0.25ᵃ | 0.25 ± 0.02ᵇ | ||

| 14 | 0.37±0.09ᵇ | 0.79±0.03ᵃ | 0.77±0.03ᵃ | 0.85±0.05ᵃ | 0.79±0.01ᵃ | ||

| 21 | 0.86±0.04ᵃ | 0.79±0.02ᵃᵇ | 0.53±0.06ᶜ | 0.75±0.07ᵇ | 0.80±0.02ᵃᵇ | ||

| Gumminess | 1 | 28.08 ± 3.75ᵇ | 46.55 ± 20.56ᵇ | 46.68 ± 6.59ᵇ | 74.09 ± 13.52ᵃ | 35.70 ± 7.27ᵇ | |

| 7 | 19.21 ± 6.41ᶜ | 72.83 ± 6.44ᵃ | 31.48 ± 13.59ᵇc | 43.86 ± 19.70ᵇ | 18.93 ± 3.02ᶜ | ||

| 14 | 38.86±12.40ᵇ | 51.42±7.27ᵇ | 109.53±8.19ᵃ | 109.77±1.12ᵃ | 47.86±2.77ᵇ | ||

| 21 | 90.77±12.81ᵃ | 75.97±6.47ᵃᵇ | 54.62±5.61ᵇ | 106.10±22.84ᵃ | 101.27±13.17ᵃ | ||

| Chewiness (N) | 1 | 21.84 ± 3.72ᵇᶜ | 41.20 ± 16.84ᵃᵇ | 43.68 ± 7.34ᵃᵇ | 63.59 ± 20.23ᵃ | 16.58 ± 4.28ᶜ | |

| 7 | 10.88±3.66ᵇ | 47.99±10.35ᵃ | 28.60 ± 9.61ᵃᵇ | 49.07±32.41ᵃ | 7.83±2.20ᵇ | ||

| 14 | 18.24±7.52ᵇᶜ | 27.41±5.12ᵇ | 49.00±5.02ᵃ | 52.49±3.23ᵃ | 16.43±3.33ᶜ | ||

| 21 | 23.51±4.07ᶜ | 32.47±10.98ᵇᶜ | 24.22±3.76ᶜ | 59.94±15.36ᵃ | 50.64±7.09ᵃᵇ | ||

| All group data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD; n=3). Different superscripted lowercase letters (p< 0.05) in groups of the same pickling day indicated significant differences. | |||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).