4.1. Effect on Flesh Quality of Largemouth Bass by BSFO Replacing Soybean Oil

The flesh textural characteristics, pivotal in quality assessment, are typically evaluated using texture profile analysis method [

15]. This method quantifies key textural parameters such as hardness, elasticity, chewiness, cohesiveness, gumminess, and resilience, mimicking the human chewing process. These parameters are influenced by several factors, including intramuscular and intermuscular fat content, collagen content in connective tissues, and myofiber diameter and density [

16]. Notably, hardness is a critical parameter for consumers, often reflecting the meat perceived value [

17].Previous studies on fish have shown that the addition of black soldier fly oil alters the texture of flesh in terms of changes in hardness, elasticity, chewiness and gumminess [

18]. In this study, we found that hardness, elasticity, chewiness and gumminess reached the higher values in the BSFO1 group, while they decreased in the BSFO2 group which had a higher degree of substitution compared with the BSFO1 group, but were still higher than the control group. This result is similar to previous discovery in

M. salmoides where the addition of BSFO to the diet significantly increased flesh hardness [

18]. Among the texture characteristics of flesh, especially hardness, are closely related to muscle lipid content [

19]. In the present study, muscle lipid content of

M.salmoides did not change significantly when the fish fed with BSFO instead of soybean oil. Previous studies in

O. mykiss,

Cyprinus carpio var. Jian and

M.salmoides have also found that the usage of BSFO in diets could not vary lipid content of muscle [

6,

8,

11].

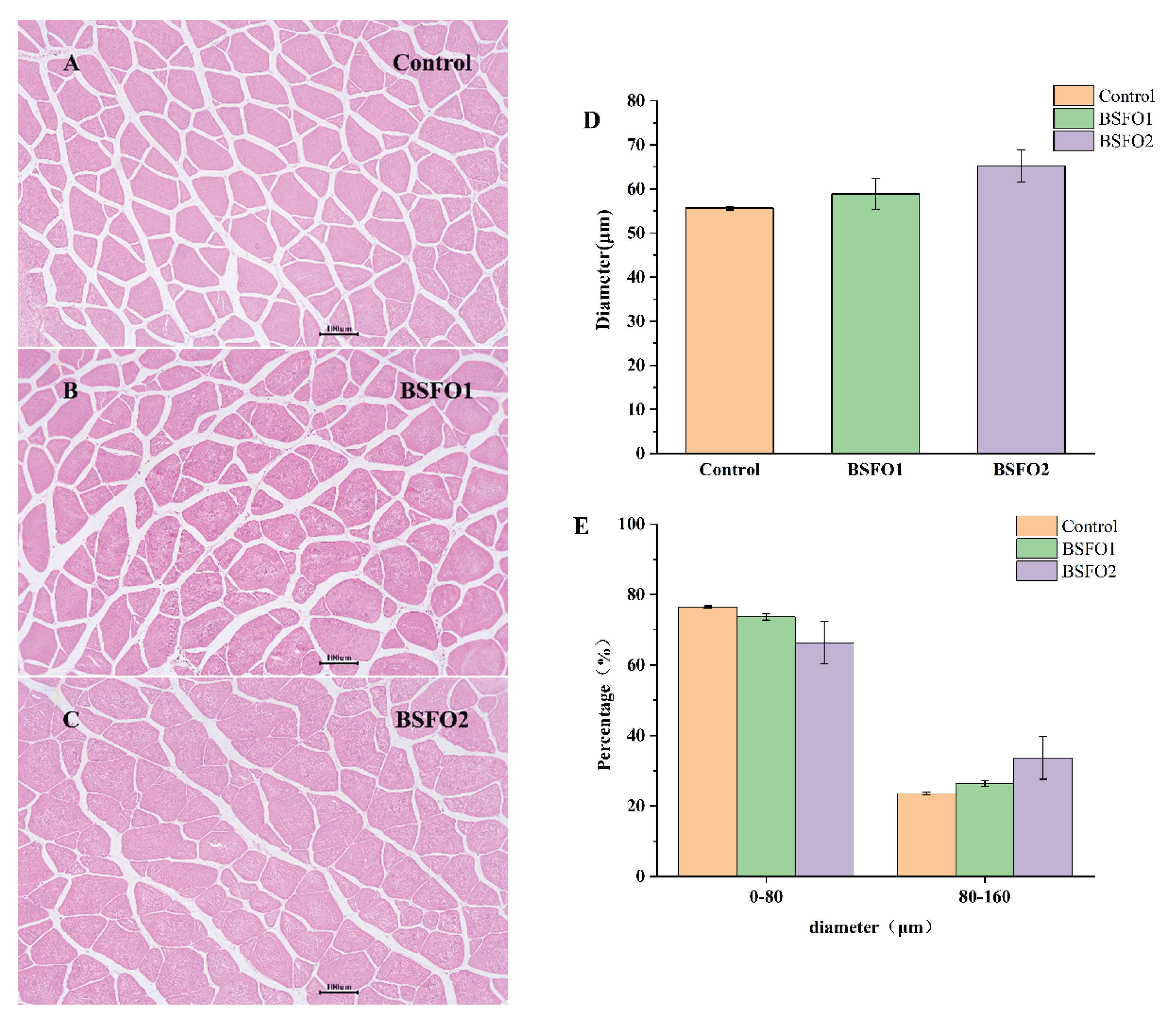

In addition, the characteristics of fish myofibers influence the quality of the flesh, particularly the hardness, which is directly related to myofiber diameter and density [

20]. Previous studies have shown that hardness and chewiness of flesh decreased as myofiber diameter increases and myofiber density decreases [

21,

22]. However, in this study, the increase in muscle hardness was not attributed to alterations in myofiber diameter, as substituting soybean oil with BSFO did not yield significant changes in either the diameter or density of largemouth bass myofiber. It was contrary to the reported by Xia et al., who found that when BSFO replaced more than 50% of fish oil, there was an increase in the diameter of

M.salmoides myofiber; conversely, no significant change occurred when the replacement ratio remained below 50% [

11]. It is possible that the difference in results is due to the difference between the fish oil and soybean oil used in the control group. Studies have shown that caspase mediated apoptosis was negatively correlated with myofiber diameter [

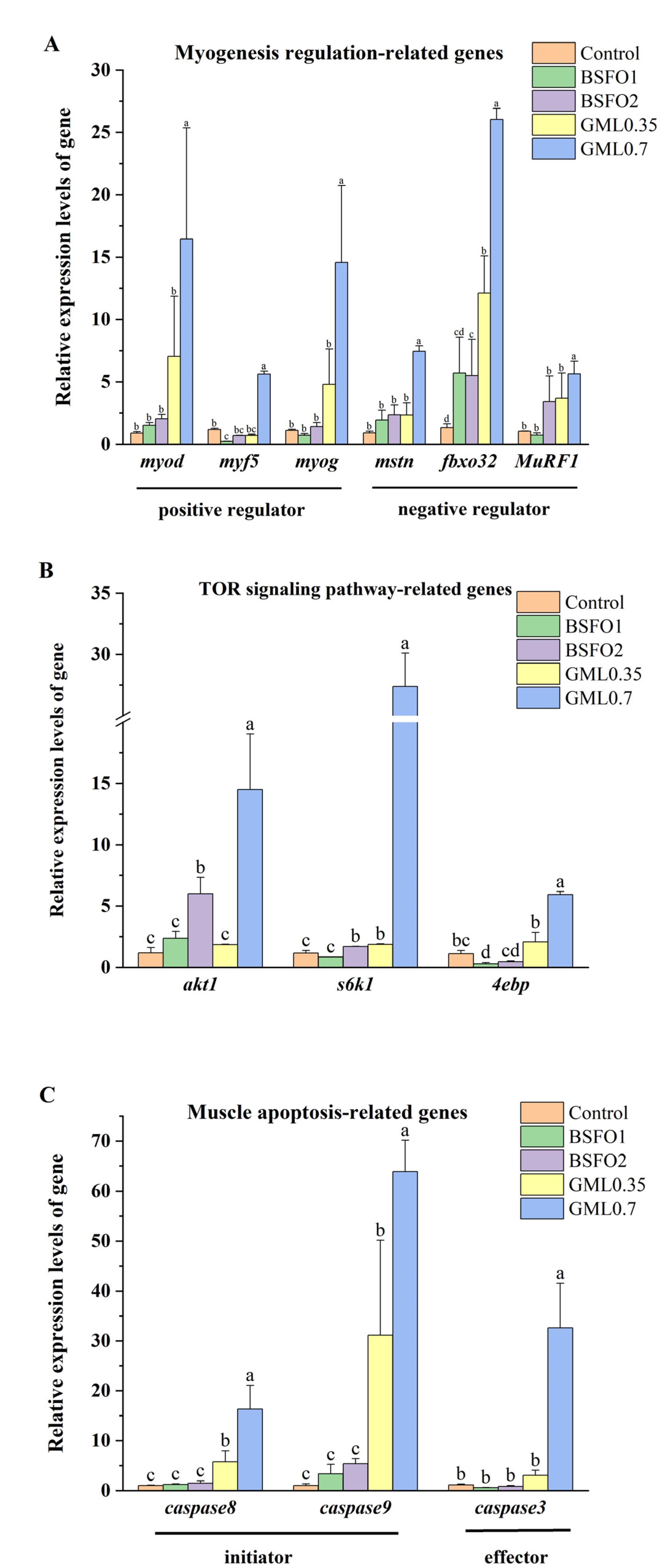

23]. In this study, fish fed BSFO had no significant impact on the relative expression levels of apoptosis initiator

caspase8 and

caspase9 and apoptosis effector

caspase3. However, the relative expression levels of

caspase8,

caspase9 and

caspase3 was significantly upregulated in the GML0.35 and GML0.7 group. This suggested that lauric acid can induce apoptosis. Interestingly, despite the high lauric acid content in BSFO, its inclusion in fish diets did not exhibit these adverse effects, highlighting the potential of BSFO as a valuable feed component, even with its high concentration of lauric acid.

Furthermore, collagen content also affects the hardness of fish muscles. As a key component of the extracellular matrix, collagen is crucial for sustaining muscle growth and texture in fish [

24]. Hydroxyproline, constituting 13.4% of the total amino and imine content in collagen and present in trace amounts in elastin, is absent in other proteins, making it a reliable indicator of collagen levels in muscle tissues [

25]. In this study, we found that hydroxyproline content increased in the muscle of

M.salmoides fed BSFO instead of soybean oil , which indicated that the increase in collagen amount is a reason of the increase in the flesh hardness.

In order to explore the mechanisms behind the observed changes in the muscle texture of

M.salmoides, we examined the expression levels of genes associated with muscle growth. Østbye et al. [

26] found a positive correlation between muscle hardness and myogenesis in Salmo salar. The process of fish muscle growth is regulated by a variety of factors, including myogenic regulatory factors (MRFs) and atrophy factors. MRFs are a family of basic helix-loop-helix transcription factors including

myod,

myf5,

mrf4 and

myog, and can convert a large number of different cell type into muscle [

27]. When the inhibition of myogenesis and protein degradation by atrophy factors exceed protein synthesis, muscle protein loss occurs, leading to a corresponding decrease in muscle hardness [

28]. The genes

mstn,

fbxo32 and

MuRF1 are three reliable atrophy sign to indicate muscle protein losing [

29,

30,

31]. After an 8-week feeding trial with dietary BSFO, we assessed its impact on the relative expression levels of

myod,

myf5,

myog,

mstn,

fbxo32, and

MuRF1 in the muscle. Previous studies have shown that some of the trophic factors affected the expression levels of one or more genes in MRFs, such as methionine levels of the dietary for rainbow trout juveniles [

32], lysine and histidine levels of the dietary for

Oreochromis niloticus [

33], plant protein levels of the dietary for Solea senegalensis [

34]. Sudha et al. [

7] found that replacing fish oil with BSFO increasing the expression levels of genes related to muscle myogenesis in

Pangasianodon hypophthalmus while reducing myostatin expression levels. However, another study on replacing fish oil in

M.salmoides diets with BSFO found that there were no significant differences in mRNA expression levels of

myod1,

murf1,

myos,

myog,

myf5 and

paxbp-1 [

11]. In this study, we replaced soybean oil in largemouth bass diets with BSFO, and found that the relative expression levels of genes related to muscle myogenesis and atrophy were not affected in the group BSFO2 compared with the control group. In the BSFO1 group, the expression level of

myf5 decreased significantly, while the expression level of

fbxo32 increased significantly, which revealing the primary cause why muscle hardness in BSFO1 group was higher than that in the control group and the BSFO2 group.

In this study, the relative expression levels of genes related to muscle myogenesis and atrophy were up-regulated in the GML0.7 group compare with the control. Despite the substantial lauric acid content in BSFO, the relative expression levels of these genes in the BSFO group were significantly lower than those in the GML group. This suggests that certain components within BSFO may mitigate the adverse effects typically associated with lauric acid, highlighting the potential for BSFO to modulate muscle gene expression in a beneficial manner.

The target of rapamycin (TOR) pathway integrates signals from extracellular and intracellular agents, which can regulate protein synthesis and promote cell survival, proliferation and growth [

35]. In the TOR pathway, kinase akt activates TOR target proteins, phosphorylates kinase S6K1 and eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E-BP1 regulate protein synthesis to promote muscle growth [

36]. In the present study, the relative expression levels of

atk1 and

s6k1 was significantly up-regulated, suggesting that BSFO promotes cell growth and may lead to increased hardness in muscle.

4.2. Effect of Diet BSFO on Fatty Acid Profile of Largemouth Bass

The fatty acid profile in fish is directly affected by the fatty acid composition of the feed [

37]. The fatty acid composition of BSFO is predominantly SFA, the majority of which is lauric acid [

38]. The results showed that as the level of BSFO supplementation in the feed increased, the content of lauric acid increased in whole body and muscle of largemouth bass. Similar results have been reported in gilthead seabream [

9]. In addition, feeding BSFO instead of soybean oil can resulte in an increase of C22:6n-3 (DHA) in muscle in Jian carp [

8]. However, the fatty acid profile in rainbow trout was not consistent with them, where the usage of BSFO replacing soybean oil had no significant change in the DHA content of the muscle [

6]. In the present study, replacing soybean oil with BSFO did not cause DHA content change in largemouth bass muscle, but significantly elevated C20:5n-3 (EPA) content in muscle, which may be attributed to the fact that lauric acid can be preferentially oxidized, allowing EPA to be better retained in muscle. The result that whole body contains more lauric acid than muscle seems to support this idea. In addition, the n-3/n-6 ratio is an important parameter for assessing the nutrition of flesh. Studies have shown that a high n-3/n-6 ratio is favorable for human health because n-3 PUFA can reduces inflammatory responses, whereas n-6 PUFA causes inflammation contrarily [

39]. In the present study, n-3/n-6 levels were also significantly higher in the BSFO1 and BSFO2 groups than in the control group. This is in agreement with the results of previous studies [

6,

10]. Thus, the addition of BSFO to the diet increased EPA levels and n-3/n-6 ratio in

M.salmoides muscle, thereby improved fatty acid quality accordingly.

4.3. Effect of Diet BSFO on Antioxidant Capacity of Largemouth Bass

T-AOC is the total level of various antioxidant macromolecules, antioxidant small molecules and enzymes within a system [

40,

41]. T-SOD is an antioxidant enzyme that protects cells from peroxidative damage [

42]. In the present study, replacing soybean oil with BSFO had no significant effect on both T-AOC and T-SOD activities in muscle. The results showed that inclusion of BSFO up to 2% in the diet had no significant effect on the antioxidant capacity of largemouth bass. Similar results have been reported, such as in the juvenile yellow catfish, BSFO as a substitute for soybean oil has no significant effect on the antioxidant capacity [

43]. However, another study found that the addition of BSFO to largemouth bass diets resulted in an increase in T-SOD activities in the liver, suggesting that BSFO improves the antioxidant capacity of largemouth bass [

11]. Because different studies have produced conflicting results, to investigate how BSFO affects the antioxidant capacity of largemouth bass, we fed largemouth bass using GML partially substitution of soybean oil. The results showed that the total antioxidant capacity of largemouth bass was significantly reduced. However, this may not be a universal phenomenon. For example, the study in hybrid grouper indicated GML increased the activity of SOD [

44]. In

Trachinotus ovatus, 0.15% GML significantly increased total antioxidant capacity and superoxide dismutase activities [

45]. Similarly, the dietary addition of GML significantly increased the SOD activity in the juvenile grouper [

46]. The different results may be due to the different effects of GML on different species of fish. In the present study, total antioxidant capacity was significantly lower in the GML groups than in the control, whereas the BSFO groups remained comparable to the control, suggesting that certain components in BSFO might mitigate the GML induced impairment of antioxidant capacity in largemouth bass.