3. Results

3.1. DNA Damage measurement

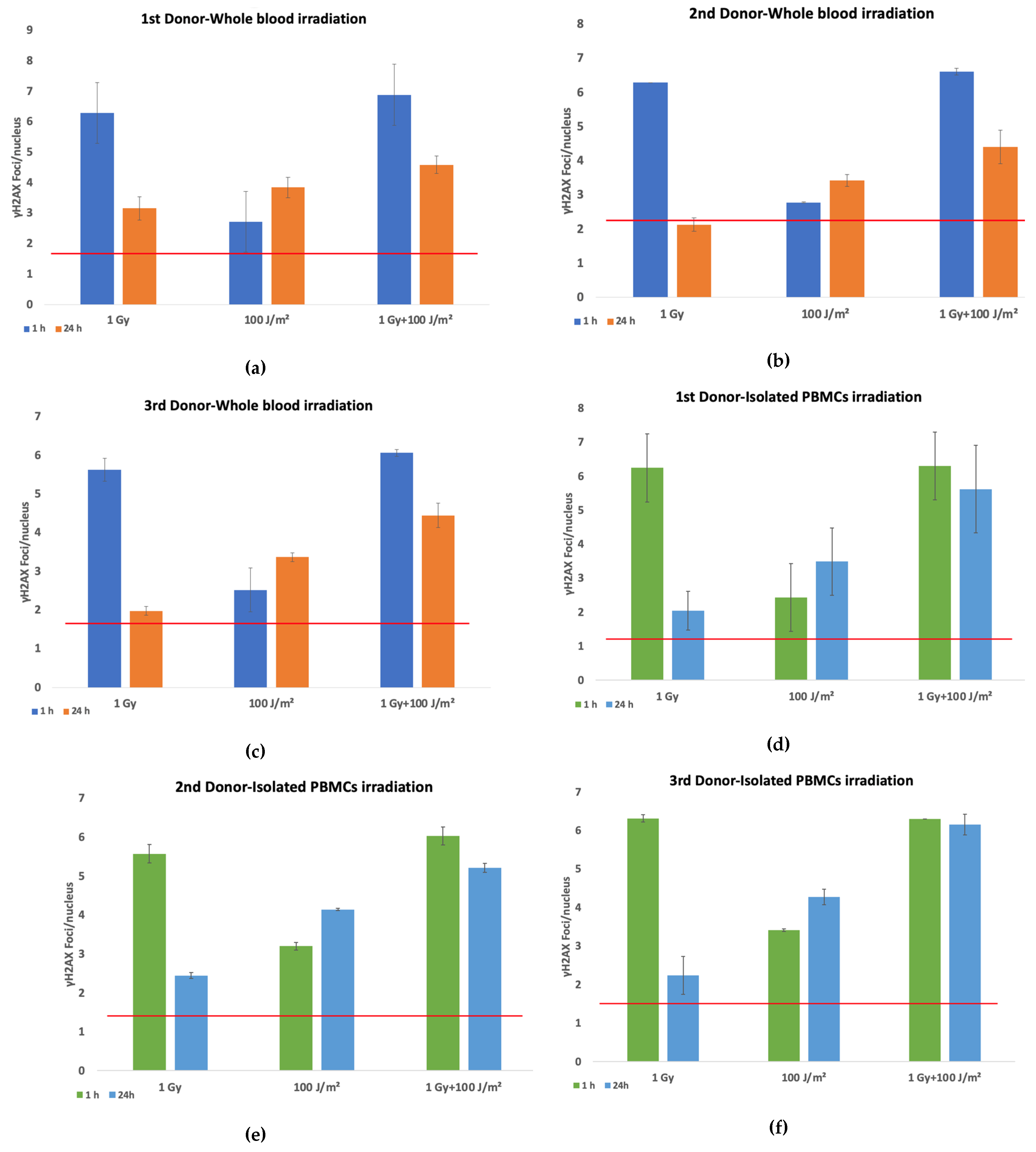

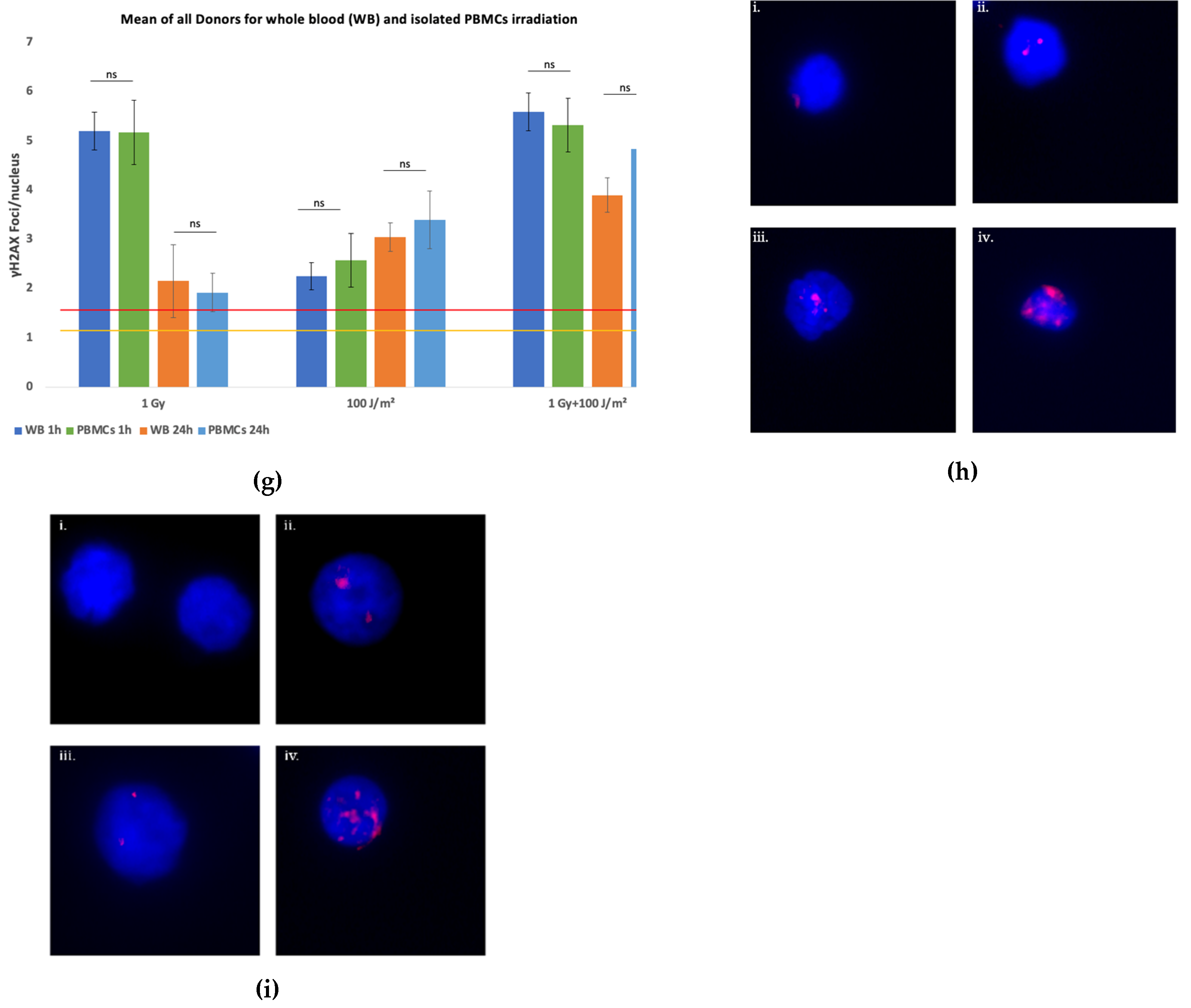

The evaluation of DNA damage responses in PBMCs following exposure to ionizing and non-ionizing radiation was performed by quantifying γH2AX foci per nucleus in both whole blood and isolated PBMCs from three different donors. Samples were exposed to 1 Gy gamma radiation or 100 J/m² UVB, and to a combination of both stressors (gamma radiation followed by UVB 20 minutes later). Irradiated samples and sham-irradiated controls were analyzed at 1 h and 24 h post-exposure. Elevated levels of γH2AX foci were detected in whole blood samples (

Figures 1a–c) at 1 h post-irradiation compared to controls, across all donors. The greatest increase was observed following 1 Gy exposure, with a moderate but consistent rise in foci after combined treatment. By 24 h, γH2AX foci generally declined toward baseline, although residual damage remained notably higher in the combined treatment group compared to single stressor exposures. A similar trend was observed in isolated PBMCs (

Figures 1d–f), with robust γH2AX induction at 1 h following gamma irradiation (1 Gy) and combined exposures to gamma rays and UVB. Meanwhile, the combined treatment group consistently exhibited the highest γH2AX foci at both time points, suggesting additive or synergistic effects of sequential gamma and UVB exposure. UVB alone induced modest γH2AX formation, especially when compared to gamma radiation. When averaged across all donors (

Figure 1g), the data confirmed higher γH2AX foci induction in isolated PBMCs than in PBMCs irradiated in whole blood, particularly in response to combined exposure. Furthermore, while γH2AX foci levels declined by 24 h post-irradiation, they remained elevated relative to the baseline, especially in samples subjected to combined stressors. A representative dose–effect curve obtained from the first donor’s isolated PBMCs, illustrating the linear relationship between the absorbed gamma dose and γH2AX foci formation, is provided in

Supplementary Figure S3.

Overall, results demonstrate that a combined exposure to gamma radiation and UVB induces increased levels of DNA damage compared to each single stressor, with isolated PBMCs displaying a more pronounced response than whole blood samples. The time-dependent decrease in γH2AX foci suggests ongoing DNA repair, although residual damage remains evident at 24 h post-exposure.

The assessment of DNA repair efficiency under all exposure conditions, both in whole blood and isolated PBMCs, was estimated with the calculation of the repair index for each donor (

Table 1) by subtracting the number of γH2AX foci at 24 h (F

24) from the number of γH2AX foci at 1 h (F

1) and dividing to the number of γH2AX foci at 1 h ie. Repair index (RI)= (F

1 – F

24)/F

1.

This metric provides a relative measure of DNA repair capacity. A lower repair index suggests limited repair or persistent damage (F24↑), while a higher repair index indicates a reduction in γH2AX foci, reflecting efficient DNA repair (F24↓). This calculation enables a direct comparison of repair dynamics between whole blood and isolated PBMCs. In whole blood samples, all three donors exhibited a decrease in γH2AX foci by 24 h as compared to the 1 h time point, with the repair index indicating more effective repair after 1 Gy exposure compared to combined treatment or UVB alone. The 3rd donor showed the lowest repair index for the co-exposure condition, suggesting slower repair or persistent damage, whereas the 2nd donor displayed a relatively better repair capacity overall. In isolated PBMCs, the repair index was generally lower than in whole blood in the co-exposure condition, indicating delayed or incomplete repair and greater susceptibility to persistent DNA damage.

3.2. Synergy evaluation – the Bliss Independence Model

To better understand and evaluate the nature (additive or synergistic) of the combined action of gamma and UVB radiation and examine whether its induced biological effects are synergistic or just additive in terms of DNA damage, the Bliss Independence Model was used in both whole blood and isolated PBMCs, based on the detected foci counts. The Bliss Independence Model, built on the probability theory of independent events, is one of the most widely used synergy metrics. This model is mainly used to evaluate drug combination efficacy through the calculation of the expected combined effects of two drugs, and subsequent comparison with the corresponding observed effects [

10,

11].

All calculations and comparisons, the single activities of agents, as well as the observed effect of their combination, should be expressed as a probability between 0 and 1, meaning that all values used by the Bliss Independence Model should be normalized to a 0-1 scale before any calculation

(https://gdsc-combinations.depmap05082023.sanger.ac.uk/documentation, assessed 20/09/2025). Derived from the complete additivity of the probability theory, where the assumption that the agents act independently means that the combined effect is equal to the product of their individual effects, according to the formula:

By solving this, we take the Bliss Independence Model formula:

The method compares the observed effect (

) induced by the combination of agents A and B with the expected corresponding effect (

), which was obtained based on the assumption that there is no agent-agent interaction effect. Typically, the combination effect is declared synergistic if

is higher than

[

11]. For a more direct comparison, the Bliss excess is usually calculated as

and the effect induced by the combination of agents A and B is characterized according to the value of

, as summarized below:

In this study, we evaluated the combined DNA-damaging effects of gamma and UVB radiation using the Bliss Independence Model. Analysis was performed on γH2AX immunofluorescence data (foci counts) at 24 h post-irradiation in both isolated PBMCs and whole blood. We focused on the 24 h time point, as synergy—if present—is expected to emerge later rather than at 1 h. Experiments were conducted in three donors, with two replicates per donor (A and B). Mean values of foci counts were normalized to a 0–1 scale using the formula:

here 0 = baseline (control) and 1 = maximal effect (highest foci count in co-exposure). In all cases, maximum damage occurred in the combined gamma and UVB exposure.

Under the Bliss model, gamma and UVB are considered independent, each inducing normalized effects E

γ and E

UVB. The expected combined effect is:

Having calculated the expected biological effect from the Bliss model (

Table 2), to evaluate the combined action of gamma and UVB and characterize it as synergistic or just additive, Bliss excess values have been estimated based on the equation:

Observed, expected, and excess values for all donors and conditions are summarized in

Table 2.

As shown from the table above (

Table 2), for each donor and both in whole blood and in isolated PBMCs, all the values for the Bliss excess (

were higher than zero. In accordance with the Bliss Independence Model, this indicates that gamma and UVB radiation, when combined, induce a biological effect that exceeds the effect of each radiation type alone, suggesting a potentially synergistic, rather than merely additive, interaction in terms of induced DNA damage.

To verify that the interaction of gamma and UVB is truly synergistic, we proceeded with a one-sample t-test. This approach allows for the comparison of the mean Bliss excess values () against zero, for investigating whether the observed synergy (in each donor in whole blood and in isolated PBMCs) was statistically significant. It should be noted that in the one-sample t-test the comparison of the mean Bliss excess was conducted against zero, since zero corresponds to the null hypothesis- namely, the absence of synergy.

The one-sample t-test revealed that the mean Bliss excess was significantly higher than zero in both experimental conditions (irradiated whole blood and isolated PBMCs), validating the synergistic action of gamma and UVB radiation in terms of induced DNA damage. More precisely, in whole blood, the mean value obtained from the three independent experiments was , with the t-test revealing that this mean was significantly higher than zero Similarly, in isolated PBMCs the corresponding , derived again from three independent experiments, was , with the t-test confirming a statistically significant difference from zero , further supporting the presence of synergy in the combined action of gamma and UVB regarding radiation-induced DNA damage.

The aforementioned analysis and the results obtained from the Bliss Independence Model contribute to a growing body of evidence suggesting that the combined action of gamma and UVB radiation can produce a greater biological effect than that induced by their corresponding additive action. These findings indicate a synergistic rather than additive interaction between gamma and UVB, based on the statistically higher DNA damage induced by the combination of these two types of radiation, as observed in both whole blood and isolated PBMCs experiments.

3.3. Genomic instability-Chromosomal aberrations assay

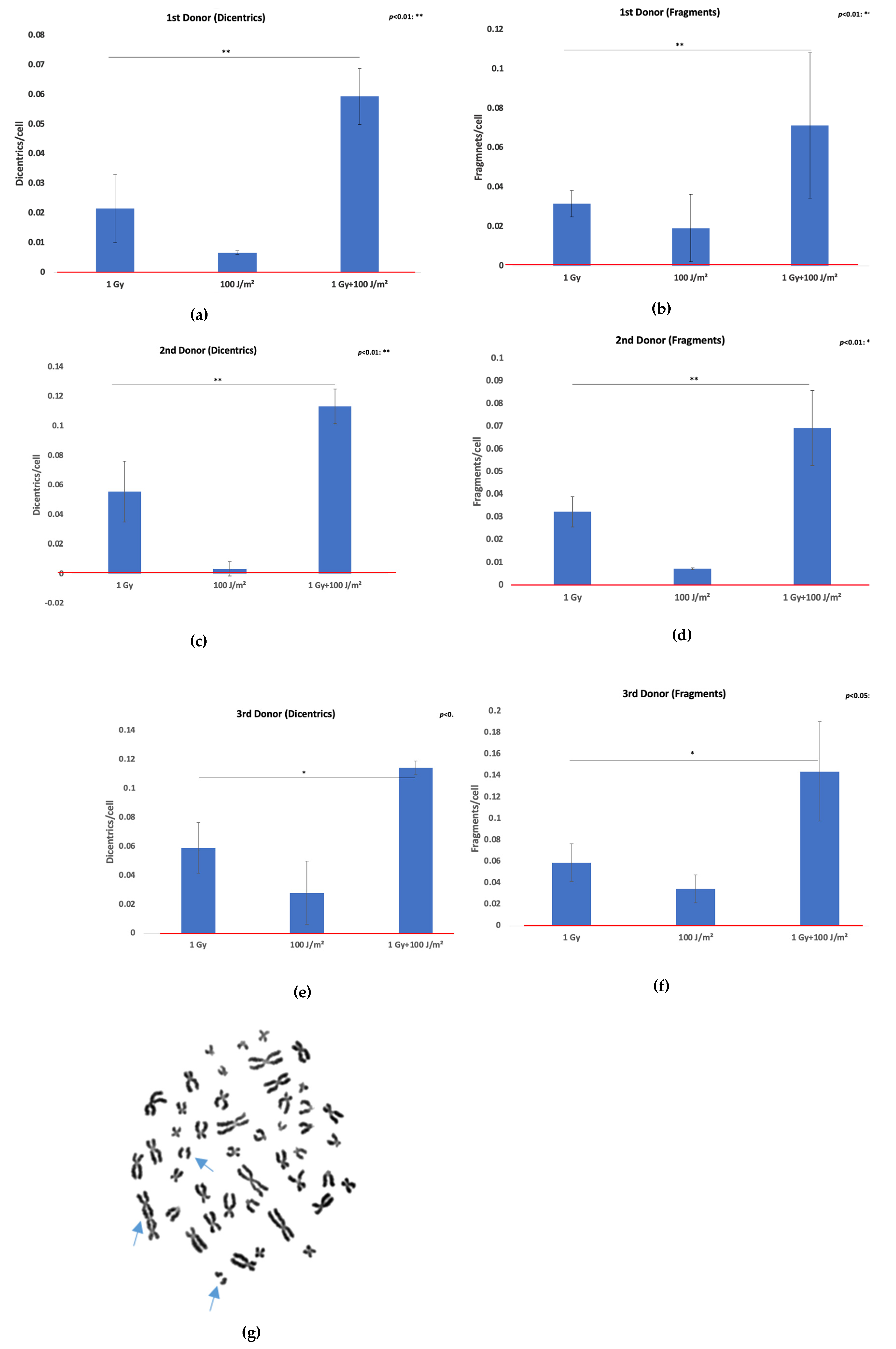

Chromosomal instability was evaluated by quantifying dicentric chromosomes (dic) and acentric fragments (ace) in lymphocytes from three donors following exposure to 1 Gy gamma rays, 100 J/m² UVB, or a combination of both (gamma rays followed by UVB). The data are presented as mean aberrations per cell ± SD from two independent experiments. In all three investigated donors (

Figure 2a–f), exposure to 1 Gy gamma rays induced a notable increase in both dicentrics and acentric fragments compared to control values. UVB exposure alone resulted in minimal chromosomal damage, whereas combined treatment (1 Gy + 100 J/m²) consistently led to the highest levels of aberrations. This additive effect was evident in all donors, with the third donor (

Figure 2e–f) exhibiting a similar pattern to donors one and two. Specifically, dicentric frequency more than doubled under co-exposure conditions relative to 1 Gy alone, and a substantial increase in acentric fragments was also observed. Importantly, representative metaphase spreads from lymphocytes subjected to combined exposure revealed complex chromosomal damage, including the presence of both chromosomal exchanges and acentric fragments (

Figure 2g), reinforcing the enhanced genotoxic effect of combined radiation fields.

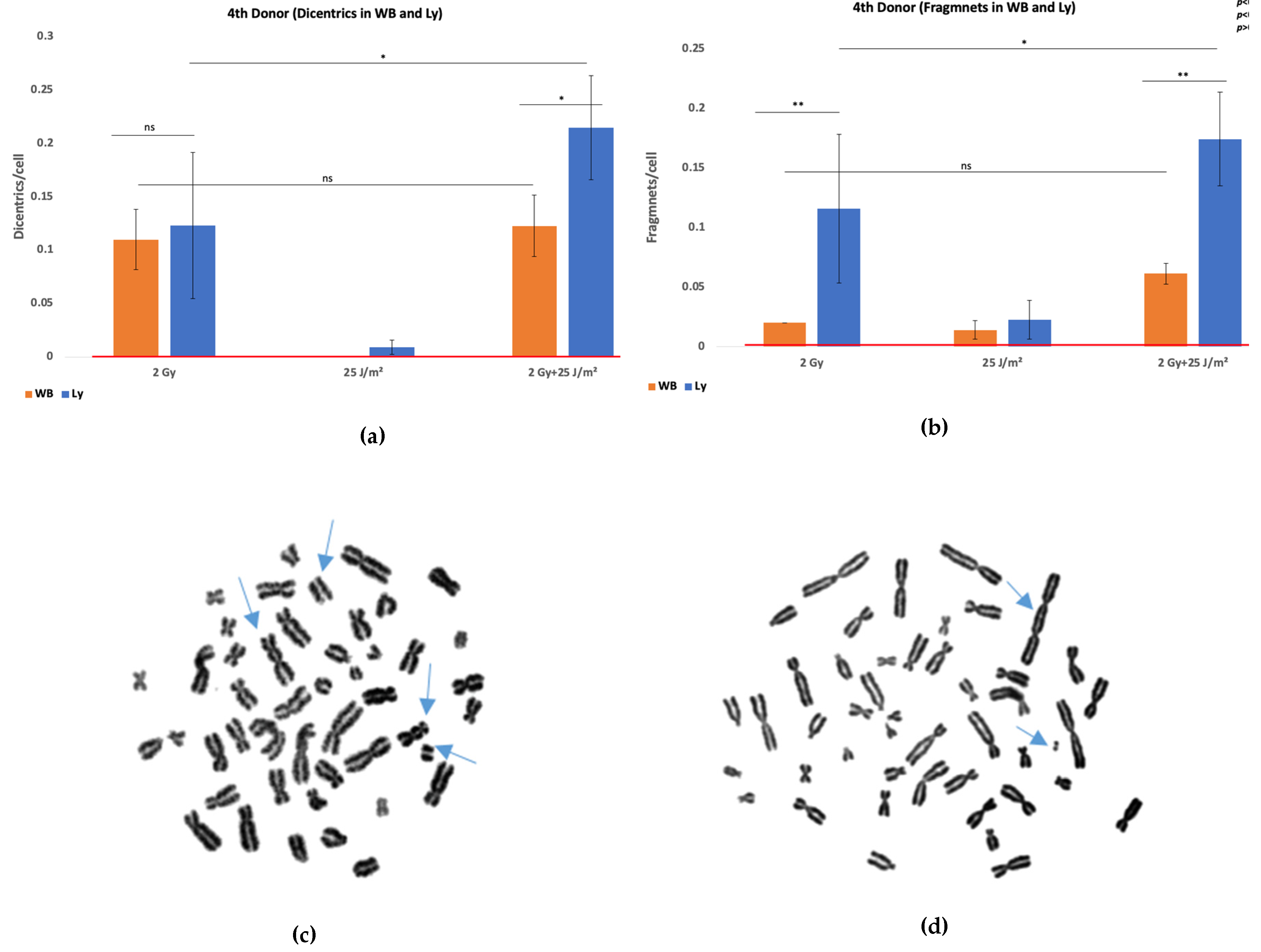

Chromosomal aberration analysis was also attempted in isolated lymphocytes from the third donor for the same exposure conditions. Isolated lymphocytes failed to yield analyzable metaphase spreads following UVB or combined treatment. Mitotic index measurements revealed that these conditions led to a marked reduction in proliferating cells, indicating a strong cytostatic or cytotoxic response (MI

control=0.0068, MI

1Gy=0.0056, MI

100J/m2=0 and MI

1Gy+100J/m2). To investigate whether this proliferative inhibition could be overcome, additional experiments were performed using a higher gamma rays dose of 2 Gy and a lower UVB fluence of 25 J/m². These irradiation conditions were applied to both whole blood and isolated lymphocytes. Results are shown in

Figure 3, and further support the differential responses and DNA damage outcomes between whole blood and isolated lymphocyte preparations (χ

2 test, p<0.05 in co-exposure condition).

Figure 3.

Schematic representation of biomarker-based assessment of genomic instability following gamma ray and UVB exposure. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells are analyzed using γH2AX immunofluorescence assay to quantify DNA double-strand breaks and dicentric chromosome assay to measure chromosomal aberrations. Both endpoints contribute to the evaluation of genomic instability after co-exposure (The figure was created using Biorender available at

https://app.biorender.com (accessed on 10 July 2025).

Figure 3.

Schematic representation of biomarker-based assessment of genomic instability following gamma ray and UVB exposure. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells are analyzed using γH2AX immunofluorescence assay to quantify DNA double-strand breaks and dicentric chromosome assay to measure chromosomal aberrations. Both endpoints contribute to the evaluation of genomic instability after co-exposure (The figure was created using Biorender available at

https://app.biorender.com (accessed on 10 July 2025).

3.4. Extension of the Linear-Quadratic Model to Predict Dicentric Chromosome Yield Following Co-Exposure of Whole Blood or Isolated PBMCs to Gamma and UVB Radiation

The elevated dicentric frequency cannot be explained by additive effects alone and aligns with observations of synergistic interactions between UVB and ionizing radiation exposures. To better capture this phenomenon, we extended the traditional linear-quadratic model by incorporating an exponential synergy term, as supported by our mechanistic and empirical findings. The standard LQ model, described by the expression Y = αD + βD², where Y is the yield of dicentrics per cell and D is the dose of ionizing radiation, captures the linear contribution (α) of single radiation-induced events and the quadratic component (β) associated with interactions between two DNA damage events [

12]. To accommodate non-ionizing UVB radiation, an additional linear term γD

UVB was introduced, where γ represents the independent contribution of UVB to dicentric formation—typically small or negligible under most exposure conditions.

Crucially, a synergy term δD

DUVB·e

(−Δt/20) was included to model the interaction between gamma rays and UVB, where δ is the synergy coefficient, D and D

UVB are the respective doses, and Δt is the time interval between exposures, reflecting temporal effects on biological repair processes. This term describes the enhanced DNA damage observed when co-exposure overwhelms repair mechanisms, resulting in a non-linear increase in dicentrics. Importantly, w

order, order index, is a dimensionless parameter that encodes the sequence of exposure: it equals 1 when gamma radiation follows UVB (a configuration known to produce stronger synergistic effects due to UVB-induced replication stress or repair interference) and is set to 0.1-0.2 when the order is reversed, while being set to 0.5 for simultaneous exposures [

13]. This index ensures that the model reflects empirical observations where the timing of radiation delivery significantly influences dicentric yield. A residual error term ε is incorporated to account for biological variability and measurement uncertainty. The proposed extension of the linear-quadratic model is given by the equation:

Using parameter values derived from literature and our experimental setup (α = 0.05, β = 0.01, δ = 0.007, w

order = 0.1, Δt = 15, D = 1 Gy, D

UVB = 100 J/m², ε = 0.01), the model predicted a dicentric yield of 0.103 dicentrics/cell under co-exposure conditions. For additional information please see the

Section 4 of Supplementary File.

Compared to our results, the model accurately captured the observed yields for donors 2 and 3, with deviations of less than 10%, confirming its validity in simulating co-exposure-induced genomic instability. For donor 1, the observed yield was substantially lower than predicted, suggesting individual variability in radiosensitivity or DNA repair capacity. These results underscore the predictive utility of the extended LQ model, particularly in mixed-radiation contexts, and highlight the importance of introducing exposure timing and sequence when modeling complex biological responses. To further evaluate the predictive accuracy of our extended linear-quadratic model, we applied it to WB data from a fourth donor exposed to 2 Gy gamma radiation or 25 J/m² UVB, and their combination. The model predicted dicentric yields of 0.150, 0.010, and 0.167 dicentrics/cell for the respective conditions. Having obtained 0.11 for 2 Gy only, 0.01 for UVB only, and 0.12 for the combined exposure, the model performed well for UVB and reasonably well for gamma radiation, but in the co-exposure condition did slightly overpredict the dicentric yield by about 0.047 dicentrics/cell.

This probably outlines the biological ‘buffering’ and protective capacity of whole blood and the potential moderating effect it has over the synergism in relation to isolated lymphocytes, as explained in greater detail in the following section. Despite this limitation, the model successfully captures both the direction and magnitude of the observed synergy, supporting its applicability in mixed-radiation biodosimetry and highlighting the importance of sample context (whole blood vs. isolated lymphocytes) in interpreting cytogenetic outcomes.

4. Discussion

No significant differences were revealed through γH2AX foci analysis of DNA damage between isolated PBMCs and whole blood across all tested conditions (1 Gy gamma rays, 100 J/m² UVB, and their combination) at both 1 h and 24 h post-irradiation (t-test, p>0.05 in all condtitions). This suggests that the immediate induction and short-term repair kinetics of DSBs were comparable between the two systems. However, a divergent pattern emerged when chromosomal damage was evaluated via the dicentric assay. In the 1 Gy gamma rays and 100 J/m² UVB co-exposure group, isolated lymphocytes exhibited significant cell death, precluding dicentric scoring, whereas lymphocytes in whole blood survived and displayed dicentric yields consistent with synergistic damage. These findings emphasize that while γH2AX foci reflect early and direct DSB formation, the dicentric assay is more sensitive to cumulative biological effects, including survival and repair dynamics. Using both γH2AX foci analysis and dicentric chromosome assays in mixed radiation exposures gives a comprehensive assessment of DNA damage and genomic instability. Together, these biomarkers form a synergistic paradigm for understanding radiation-induced genomic instability, capturing both acute DNA damage signaling and its downstream cytogenetic consequences. Crucially, their combined use emphasizes the need for multi-endpoint methods for precise biodosimetry and risk evaluation in situations where ionizing and non-ionizing radiation exposure occurs sequentially or simultaneously (

Figure 3). The comparatively small number of blood samples examined in this study is a limitation that might restrict how broadly the results can be applied; nonetheless, the primary goal was to outline the methodology and show how the aforementioned biomarkers could be used to evaluate DNA damage after combined exposures.

The estimated repair index further supports the differences in long-term cellular outcomes, as across all donors and exposure types, isolated PBMCs consistently showed lower values than whole blood, particularly in co-exposure conditions, indicating a reduced ability to resolve DNA damage over time. Furthermore, exposure to a sub-toxic dose of 2 Gy gamma rays and 25 J/m² UVB showed a synergistic increase in dicentrics in the remaining viable isolated lymphocytes, with no effect in whole blood, suggesting that plasma-mediated protective mechanisms blunted the synergy. The observed discrepancy between isolated lymphocytes and whole blood may also reflect the intrinsic protective and reparative properties of the blood matrix.

Our findings align with growing evidence that blood, particularly its plasma components, plays a significant protective role against UVB-induced oxidative damage. Plasma contains a variety of endogenous antioxidants—including uric acid, vitamin C, and thiol-containing proteins—which scavenge reactive oxygen species (ROS) generated during UVB exposure [

14]. Human serum albumin (HSA), via its Cys34 thiol, contributes roughly 40–70% to this capacity, and, in some contexts, the thiol itself accounts for up to 80% of albumin’s radical-scavenging activity [15-18]. Uric acid (urate) provides over half of the antioxidant potential in plasma [

19], acting as a scavenger of ROS such as peroxyl, and hydroxyl radicals [

20]. In addition, erythrocytes contain robust enzymatic antioxidants—catalase, glutathione peroxidase, and superoxide dismutase—that constitute a first-line defense against ROS in the blood, rapidly detoxifying hydrogen peroxide and superoxide anions [

21,

22]. This multienzyme system is essential for protecting hemoglobin and maintaining redox balance in circulating blood. By lowering extracellular ROS levels, erythrocytes likely mitigate ROS-mediated secondary oxidative DNA damage in co-circulating lymphocytes. In parallel, the presence of erythrocytes lowers local oxygen tension, since dissolved O₂ is rapidly bound and consumed, and this reduces the oxygen enhancement effect (OER) of low-LET radiation [

23,

24]. Furthermore, platelet-rich plasma (PRP), a blood derivative enriched with growth factors and antioxidants, has been shown to reduce UVB-induced apoptosis, decrease pro-inflammatory cytokines, and enhance antioxidant enzyme activities such as superoxide dismutase (SOD) and glutathione peroxidase [

25,

26]. Collectively, these observations support the contention that blood is not just a reservoir for markers of oxidative stress but is itself an active participant in the protection of the body from UVB damage. This cellular contribution to biochemical buffering likely is responsible for the increased survival and detectability of chromosomal aberrations in whole blood co-exposure models compared to isolated lymphocyte systems. Detection of γH2AX foci in isolated PBMCs and whole blood under all conditions may on a first look seem to be in conflict with the outcome of dicentric assays, which showed evident differences in cell survival and chromosomal aberrations. However, this can be attributed to the distinct biological time windows captured by each method, as γH2AX foci are rapidly formed—within several minutes—at DNA DSBs, and therefore assay is highly sensitive to primary DNA damage. Importantly, γH2AX formation does not require long-term cell survival; even PBMCs that are destined to undergo apoptosis still show foci during the early hours post-irradiation. The similar foci counts observed at 1 h in both systems reflect comparable initial damage induction. In contrast, the dicentric assay requires cells to survive, enter mitosis, and complete at least one division within ~48 hours. As a result, only those lymphocytes that successfully repair or tolerate damage will contribute to dicentric scoring. This explains why isolated PBMCs exposed to 1 Gy gamma rays and 100 J/m² UVB showed early γH2AX foci but failed to survive for chromosomal analysis, whereas whole blood samples, protected by plasma antioxidants and supported by a physiological environment, exhibited robust dicentric yields.

A key observation from our study is the persistence of elevated γH2AX foci at 24 h after UVB exposure. While γH2AX is typically associated with the immediate marking of DSBs, its persistent presence long after irradiation suggests incomplete resolution of DNA damage or ongoing secondary break formation. As previously reported by Freeman et. al [

27], UVB irradiation in lymphocytes generates lesions that can persist due to the limited efficiency of nucleotide excision repair (NER) in non-dividing cells. Our finding of elevated γH2AX foci at 24 h may therefore reflect the accumulation of unrepaired or misrepaired lesions, replication-associated conversion of photoproducts into DSBs, or complex DNA Damage formation.

Aside from qualitative observations of increased DNA damage during co-exposure, our statistical analysis using the Bliss Independence Model provides quantitative evidence that gamma and UVB radiation interact synergistically at the cellular level rather than additively, as evidenced by the positive Bliss excess scores in all cases. These findings suggest that gamma and UVB radiation cause DNA damage via independent but complimentary mechanisms, overwhelming repair pathways and amplifying genotoxic effects when stressors are combined leading to increased chromosomal instability and cancer risk.

One of the most serious and well-documented consequences of ionizing radiation exposure is an increased lifetime chance of cancer, which is thought to be the primary stochastic effect. According to the BEIR VII Phase 2 report (National Research Council, 2006), a dosage of 1 Gy from low-LET radiation, such as gamma rays, is related with an estimated 5% increase in lifetime risk for all solid malignancies in an adult population. This estimate is based on epidemiological studies of atomic bomb survivors, medical patients, and occupationally exposed populations, and it employs the linear no-threshold (LNT) model. In this study, we evaluated the cytogenetic impact of single and combined exposures to ionizing (gamma rays) and non-ionizing (UVB) radiation in peripheral blood lymphocytes using the γH2AΧ immunofluorescence and dicentric chromosome assay. Our results through chromosomal aberration analysis for the 2nd donor demonstrate that while 1 Gy of gamma rays alone produced a mean dicentric frequency of 0.055, the co-exposure condition resulted in a significantly higher frequency of 0.113 dicentrics per cell. This marked increase suggests a synergistic interaction between the two radiation types, leading to enhanced chromosomal instability.

To interpret the biological significance of this co-exposure, we estimated the equivalent gamma ray dose that would be required to produce the same cytogenetic effect observed under combined exposure conditions. Using a linear-quadratic dose–response model typical of low-LET gamma ray calibration curve produced by Abe et al. [

28]: Y=0.0013+0.0067D+0.0313D

2 (r = 0.9985) we calculated that a dicentric yield of 0.113 corresponds to an effective gamma ray dose of approximately 1.79 Gy, confirming the contribution of UVB in amplifying DNA damage beyond that induced by gamma rays alone.

Importantly, we assessed the potential health implications of such exposures by estimating the associated cancer risk. According to the BEIR VII risk model for low-LET ionizing radiation, each gray of acute exposure increases lifetime cancer risk by approximately 5% [

29]. Applying this model to the equivalent dose of 1.79 Gy suggests an excess lifetime cancer risk of around 8.9%. Similarly, for the 1

st donor, a dicentric frequency of 0.059 was observed following co-exposure to 1 Gy gamma rays and 100 J/m² UVB. Using the same linear-quadratic dose–response model [

28] we estimated that this aberration yield corresponds to an effective gamma ray dose of approximately 1.26 Gy. Applying the BEIR VII cancer risk model, the estimated excess cancer risk for this donor under co-exposure conditions is approximately 6.3%. This value is still higher than the baseline risk associated with 1 Gy exposure alone and further supports the synergistic genotoxic potential of combined gamma and UVB radiation. The lower equivalent dose reflects inter-individual variability in cytogenetic response and reinforces the importance of donor-specific biodosimetry in mixed radiation exposure scenarios. For the 3

rd donor, results clearly demonstrate a synergistic genotoxic effect from co-exposure to 1 Gy gamma rays and 100 J/m² UVB, as according to Abe et al.'s linear-quadratic dose-response model, the measured dicentric yield of about 0.112 dicentrics/cell equates to an effective gamma-ray dosage of roughly 1.78 Gy and using the BEIR VII cancer risk model, this dose corresponds to an estimated extra lifetime cancer risk of 8.8%.

The aforementioned findings emphasize the possibility of synergistic interactions between ionizing and non-ionizing radiation amplifying DNA damage and, thus, carcinogenic potential. Beyond cancer, ionizing radiation has been linked to a variety of non-cancer health concerns, particularly when exposure is moderate to high or affects sensitive tissues. Radiation-induced cataracts are a well-documented deterministic consequence, with even modest doses (0.5 Gy) causing opacities in the eye's lens[

30]. Cardiovascular effects have also gained significant attention in recent years; studies have shown that radiation doses exceeding 0.5–1.0 Gy to the heart or major arteries are associated with increased risk of ischemic heart disease and stroke [

31,

32]. Chronic exposure has also been implicated in promoting atherosclerosis and microvascular damage, possibly through persistent inflammation and endothelial dysfunction [

33]. Additionally, high-dose radiation to the brain, especially in children, has been linked to neurocognitive impairments and neuroendocrine dysfunctions [

34,

35].

The use of cytogenetic assays, such as the dicentric chromosome assay, remains a gold standard for estimating absorbed radiation doses and offers insight into potential long-term health effects, including cancer risk [

36,

37]. The findings of this study reinforce the need to consider combined exposures in radiation protection frameworks, particularly in clinical, occupational, or environmental settings where individuals may be exposed to both ionizing and non-ionizing radiation sources. In addition to increased dicentric chromosome formation, our study revealed a notable presence of acentric fragments in peripheral blood lymphocytes following co-exposure to 1 Gy gamma rays and 100 J/m² UVB. The simultaneous elevation of both aberration types suggests distinct yet complementary damage pathways activated by the combined exposure. The mechanistic differences between dicentrics and fragments become especially relevant in the context of combined gamma rays and UVB exposure [37-39]. Gamma rays induce DSBs via direct ionization and, indirectly, through ROS production, affecting both nuclear and mitochondrial DNA. UVB, although being a non-ionizing radiation, causes bulky DNA lesions such as cyclobCPDs and 6-4 photoproducts, which primarily stall DNA replication forks and activate the NER pathway [

40,

41]. When combined, UVB may inhibit accurate DSB repair by either saturating repair machinery or interfering with signaling cascades such as ATM/ATR and p53. This replication stress can convert UVB-induced lesions into DSBs during the S-phase, further compounding the damage initiated by gamma rays. The net result is both increased misrejoining (yielding dicentrics) and accumulated unrepaired breaks (leading to fragments) [

42]. Biologically, the presence of both dicentrics and fragments indicates not only enhanced chromosomal instability but also increased cell heterogeneity, which is a known cause of clonal evolution and cancer[

43]. While dicentrics are unstable and often removed during cell division, acentric fragments can persist longer and may be incorporated into micronuclei, contributing to chromothripsis-like events and long-term genomic instability [

7,

44,

45].