1. Introduction

Tomato (

Solanum lycopersicum L.) is one of the most widely produced and consumed vegetables worldwide [

1,

2]. In Costa Rica, tomato cultivation primarily occurs in the Central Valley regions, with a production of 55,307 metric tons on 1,510 hectares reported in 2018 [

2]. The high demand for tomatoes in most countries makes it an intensive production crop in which techniques must be used to maximize yield per unit of land [

3]. Also, producing countries must have climatic conditions such as temperatures around 18-32°C and relative humidity around 55-90% that favor year-round cultivation [

4,

5], and measures to control the development and spread of fungal and bacterial diseases.

Bacterial infections affect crop yields, causing significant economic losses [

6,

7] which can reach up to 91% in yield losses in some cases, such as bacterial wilt caused by

Ralstonia solanacearum [

8]. As a result, bacteria pose a significant global threat to agricultural production, and their control is crucial for ensuring food security [

9,

10].

Among the most frequently reported bacterial diseases in Costa Rica, bacterial wilt caused by the

Ralstonia species complex is the most important and destructive. In recent years, the damage caused by other bacteria has focused on soft rot caused by

Pectobacterium spp., bacterial speck caused by

Pseudomonas spp., and bacterial spot caused by

Xanthomonas spp. [

11,

12,

13]. In addition to these diseases, others, such as pith necrosis, are either infrequently reported in crops or have not yet been officially recorded in the country. One such case is tomato pith necrosis, a disease whose characteristic symptom has been repeatedly observed in samples collected between 2021 and 2023 in various locations in the Central Valley of Costa Rica.

Tomato pith necrosis was first described in the 1970s, caused by

Pseudomonas corrugata [

14], since then, other causal agents have been identified, including various

Pseudomonas species such as

P. mediterranea [

15],

P. cichorii [

16],

P. viridiflava [

17],

P. marginalis [

18],

P. fluorescens and

P. putida [

19], as well as species from other genera such as

Xanthomonas perforans [

20] and

Pectobacterium carotovorum [

21].

Pseudomonas corrugata has been the principal species associated with the disease since its initial description and is now widely distributed across most tomato-producing countries worldwide [

22]. In the Americas,

P. corrugata has been reported in Brazil [

23], Argentina [

24], Uruguay [

25], Mexico [

26], and the United States [

27,

28,

29,

30,

31]. In Costa Rica, the presence of

P. corrugata is presumed; however, no official reports or targeted studies have been made regarding the identification of the species responsible for tomato pith necrosis in the country.

Incidence of pith necrosis within plantations can range from 10% to 100%, depending on factors such as the bacterial species, environment, cropping system, and management practices [

14,

18,

29,

32]. Additionally, up to 20% losses in fruit weight and size have been reported and related to the presence of pathogens such as

P. corrugata and

P. mediterranea [

33]. In severe infections, the wilting caused by pith necrosis becomes widespread and leads to plant death [

25].

These considerations highlight the importance of evaluating pathogenic bacteria present in crops. The objective of this study was to identify the bacteria present in tomato plants exhibiting symptoms of pith necrosis using last-generation techniques and to evaluate the pathogenicity of bacterial isolates collected from different locations in the Central Valley of Costa Rica.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bacterial Isolates and Plant Material

We evaluated 13 Gram-negative bacterial isolates obtained from tomato plants showing stem necrosis symptoms as the most recurrent symptom. Isolates were collected in Paraíso (2) in Cartago province, Alajuela (5) and Zarcero (1) in Alajuela province, and Santa Bárbara (5) in Heredia province, all located in the Central Valley of Costa Rica. Bacterial isolates were classified to the genus level by partial sequencing of the 16S rRNA gene and were selected from a broader set of isolates based on previous reports of plant pathogenic genera and species.

Five-week-old seedlings of the commercial tomato variety “JR”, which is susceptible to bacterial diseases, and the “Acorazado” variety, developed by the Tomato Breeding Program at the Fabio Baudrit Moreno Agricultural Experiment Station (EEAFBM-UCR) and carrying resistance genes to

Ralstonia solanacearum phylotype I and Tomato Yellow Leaf Curl Virus (TYLCV) strain Israel [

34], were used as plant material. Seedlings were transplanted into 12.8 × 10 cm pots filled with sterile soil and maintained under greenhouse conditions at 26.3°C ± 2.9°C and 58.8% ± 9.1% relative humidity.

2.2. Inoculation and Evaluation

The inoculum was prepared from fresh cultures on tryptic soy agar (TSA); colonies were suspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to a concentration of 1×10⁸ CFU/ml. Inoculation was performed by directly injecting 100 µl of bacterial suspension into the stem at the height of the first true leaf. Six plants per bacterial isolate and per variety were inoculated, along with six plants per variety as PBS-inoculated controls. In total, 168 plants were evaluated over a 21-day period (21 days after inoculation [dai]). Plant growth, defined as the difference between final height and initial height (

) was measured, and the presence of external and internal symptoms was assessed. Internal symptoms were evaluated by making a longitudinal cut of the stem from the inoculation point towards both ends. The extent of pith necrosis or tissue discoloration (cm) was measured in plants that exhibited the symptoms. The severity scale described by Aysan [

35] was used to classify the isolates. These were classified as “non-virulent” if no symptoms were observed; “low-virulent” if necrosis extended 0.1–2.0 cm; “virulent” if necrosis extended 2.1–4.0 cm; and “highly virulent” if necrosis extended ≥ 4.1 cm. To fulfill Koch’s postulates, the bacteria were reisolated from the symptom on nutrient agar (NA), and their identity was confirmed through partial

16S rRNA gene sequencing.

2.3. Identification of Bacterial Isolates

Pseudomonas isolates causing pith necrosis were identified by Multilocus Sequence Analysis (MLSA) using concatenated partial sequences of the

16S rRNA [

36],

gyrB [

37],

rpoD [

38], and

rpoB [

39] genes. Genomic DNA was extracted from fresh bacterial colonies (< 24 h) using the CTAB protocol [

40] with modifications described by Trout [

41]. PCR reactions were carried out in a final volume of 25 µl containing 2.5 µl of 10X Dream Taq buffer (Thermo Scientific™), 2.5 µl of 2 mM dNTP mix (Thermo Scientific™), 1.25 µl of each 100 µM primer (

Table S1), 0.25 µl of Dream Taq DNA polymerase 5 U/µl (Thermo Scientific™), 1 µl of DNA template (60.6 ± 37.5 ng/µl), and ultrapure water to complete the volume. The thermal profile for each reaction was programmed using amplification parameters specific to each primer pair. PCR product amplification was confirmed by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis.

PCR products were purified with Exonuclease I and sequenced at Macrogen, Inc. (Seoul, South Korea) using the Sanger method [

42]. Sequences were edited and assembled in BioEdit v.7.0.5.3 [

43], along with type strain sequences downloaded from the NCBI GenBank database (

Table S2). Sequence alignment for each locus was performed using MAFFT v.7 [

44] with default parameters. Aligned and trimmed sequences of the genes

16S rRNA (1,266 bp),

gyrB (443 bp),

rpoD (409 bp), and

rpoB (669 bp) were concatenated into a single matrix using Mesquite v.3.61 [

45], totaling 2,787 bp. JModelTest v.2.1.10 [

46] was used to determine the best nucleotide substitution model for each locus.

Bayesian phylogenetic analysis was performed in MrBayes v.3.2.6 [

47]; four chains were run under the GTR+I+G model for the

16S rRNA,

gyrB, and

rpoD genes, and the SYM+I+G model for

rpoB, with 1,000,000 Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) generations.

Pseudomonas aeruginosa strain DSM 50071

T was used as the outgroup. A maximum likelihood phylogenetic analysis was also conducted using RAxML v.8.2.12 [

48] through the raxmlGUI v.2.0.9 interface [

49], with the GTR+I+G model, 1,000 replicates, and bootstrap support values. The consensus phylogenetic tree was edited in iTOL v.6.9.1 [

50]. Partial housekeeping gene sequences (

gyrB,

rpoB, and

rpoD) of pathogenic

Pseudomonas isolates were deposited in the GenBank database under accession numbers PQ883186–PQ883197.

The remaining bacterial isolates were identified by partial sequencing of the

16S rRNA gene and compared with type sequences from the GenBank database (

Table S3), using the same procedure as the multilocus analysis, except for the concatenation step. The GTR+I+G substitution model was used, with a total alignment length of 1,346 bp, and

Bacillus subtilis strain IAM 12118

T was used as the outgroup. Partial

16S rRNA gene sequences of the bacterial isolates from this study were deposited in GenBank within the accession numbers PQ857593–PQ857653.

2.4. Genome Sequencing and Analysis

A single colony of virulent isolates

Pseudomonas alliivorans LTM 13.1.2 and

Pseudomonas capsici LTM 78.3.2 picked from the NA media plates was used for genomic DNA extraction using the CTAB 2% method [

40] with some modifications described by Trout [

41]. DNA concentration and quality were assessed using a NanoDrop

TM One (ThermoScientific

TM, USA). The DNA libraries were prepared using the Illumina DNA Prep Kit, and the whole genome sequencing was performed using the Illumina NovaSeq Plus X (2 x 151) paired end method at SeqCenter in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. The raw reads were trimmed using Trimmomatic 0.36 [

51] and assembled with Unicylcer v0.4.8 [

52]. The quality of the genomes was assessed with Quast [

53]. The taxonomic classification of the genomes was conducted using GTDB-Tk [

54], and the functional annotation was conducted using EggNOGmapper 2.0 [

55]. Other genomic features such as secondary metabolites and virulence factors were also annotated using Antismash 8.0 [

56] and MmetaVF toolkit [

57], respectively. Genomes data can be found in the NCBI BioProject accession number PRJNA1314254. For details on the draft genomes, see [

58].

2.5. Statistical Analysis

A linear model was fitted to evaluate the mean plant growth

as a function of bacterial isolate, tomato variety, and their interaction. Model selection based on the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) supported the inclusion of the interaction term:

Where represents the height increment of plant exposed to bacterial isolate and tomato variety ; is the intercept corresponding to the reference isolate and variety; and represent the main effects of specific bacterial isolate and tomato variety, respectively; captures the interaction between bacterial isolate and variety; and is the residual error term, assumed to follow a normal distribution with mean zero and constant variance.

The same linear model structure was used to evaluate the effect of bacterial isolates, tomato variety, and their interaction on internal stem lesions, with lesion length (

) as the response variable. The model with interaction was selected based on AIC as the best fit for the data:

Where represents the extent of internal lesion in each plant for each bacterial isolate and tomato variety ; is the intercept; and represent the main effects of specific bacterial isolate and tomato variety, respectively; captures the interaction between isolate and variety; and is the residual error term, assumed to follow a normal distribution with mean zero and constant variance.

A Fisher’s LSD test for pairwise comparisons was applied to the fitted linear models to determine statistically significant differences among each bacterial isolate-tomato variety combination.

To assess the effect of internal lesion length (pith necrosis) on plant growth (height increment), two multiple linear regression models were fitted: one including an interaction term between necrosis and tomato variety, and another without interaction. Model selection based on AIC favored the model without interaction:

Where represents the expected increase in height of plant ; is the intercept; is the coefficient for the extent of pith necrosis; and is the coefficient for the tomato variety; and is the residual error term, assumed to follow a normal distribution with mean zero and constant variance.

All analyses were performed in the R environment [

59]. Model selection based on AIC was done using the ‘performance’ package [

60], mean contrast tests were conducted using the ‘agricolae’ package [

61], and models were plotted using the ‘ggeffects’ [

62], ‘sjPlot’ [

63] and ‘ggplot2’ [

64] packages.

3. Results

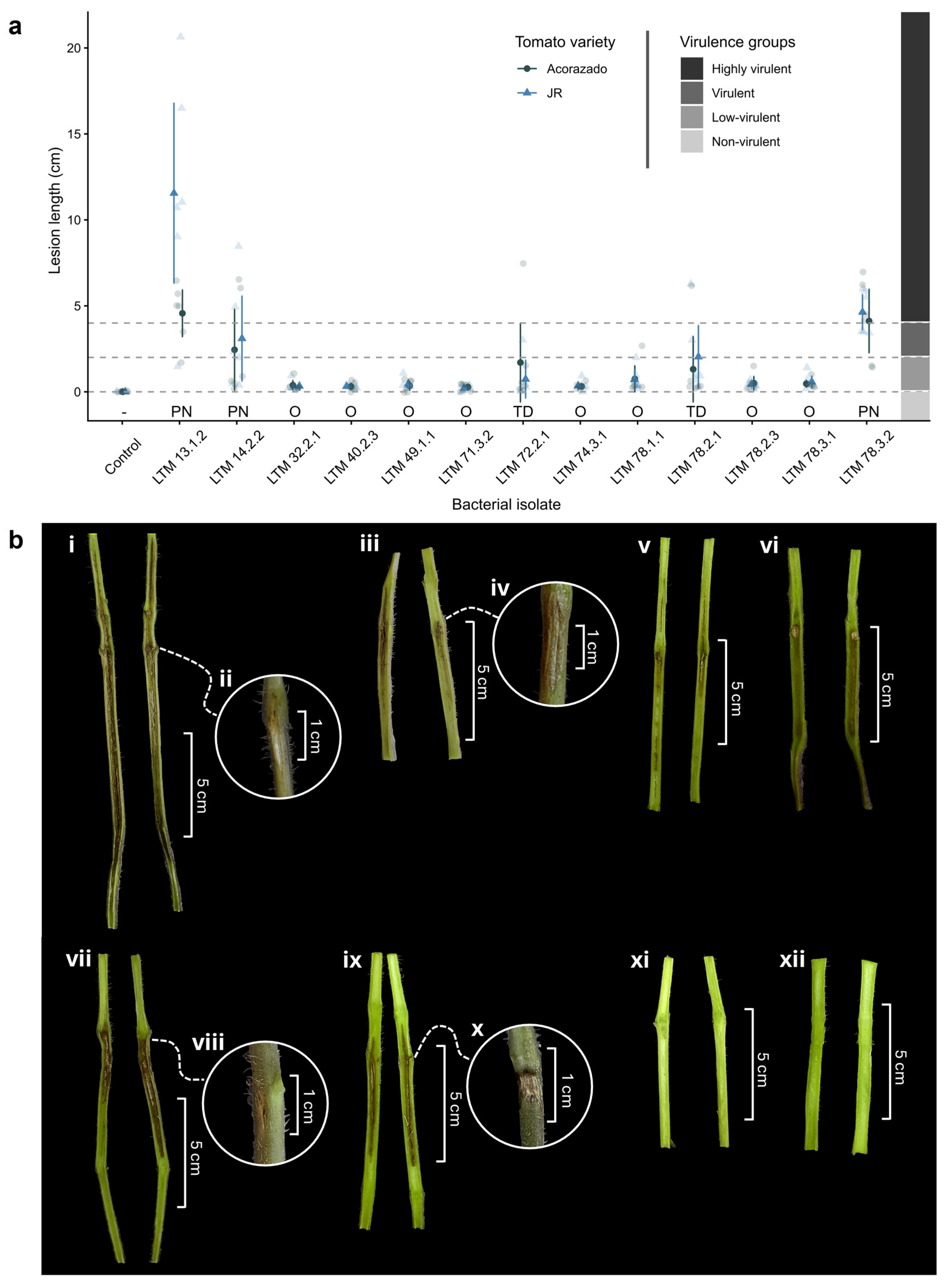

3.1. Pathogenicity

A total of 61 bacterial isolates were obtained from symptomatic tomato plants and taxonomically classified by

16S rRNA sequencing. Based on previous reports of plant pathogenic genera/species, 13 isolates were selected for pathogenicity assays to confirm their ability to cause pith necrosis or related stem tissue symptoms in tomato plants, the most recurrent symptom observed in the collected samples. Five of the 13 bacterial isolates assessed in this study caused internal symptoms in both tomato varieties, three of which caused pith necrosis and two caused tissue discoloration. Isolates that only caused slight oxidation at the inoculation site without affecting adjacent tissue were considered non-pathogenic. The most virulent isolate was

Pseudomonas alliivorans LTM 13.1.2, with a pith necrosis extension of 11.55 ± 5.25 cm in var. “JR” and 4.57 ± 1.37 cm in var. “Acorazado” (

Table 1,

Figure 1). The necrosis caused by this isolate represented 27.3% of the final plant height (42.35 ± 2.23 cm) at 21-dai in var. “JR.” This was the only isolate that showed significant differences in necrosis extension between varieties, being 39.57% greater in var. “JR” (p < 0.05) (

Figure 1a). The second most virulent isolate was

P. capsici LTM 78.3.2, with pith necrosis of 4.63 ± 1.03 cm in var. “JR” and 4.12 ± 1.86 cm in var. “Acorazado” (

Table 1,

Figure 1). Both isolates were classified as “Highly virulent” according to the scale by Aysan [

35].

P. flavescens LTM 14.2.2 was classified as “Virulent” for causing 3.10 ± 2.49 cm of necrosis in var. “JR” and 2.45 ± 2.37 cm in var. “Acorazado” (

Table 1,

Figure 1).

P. straminea LTM 78.2.1 was classified as “Virulent” for causing 2.03 ± 1.83 cm of tissue discoloration in var. “JR”, and

Cedecea sp. LTM 72.2.1 as “Low-virulent” with 1.70 ± 2.31 cm of tissue discoloration in var. “Acorazado” (

Table 1,

Figure S1). These last two isolates showed greater variability than other isolates classified as “Low-virulent”, which only caused mild discoloration at the inoculation site without spreading through the tissue. A trend of greater necrosis or discoloration extension was recorded in the “JR” variety, except for isolate LTM 72.2.1, which caused greater discoloration in the var. “Acorazado.” External symptoms such as discoloration and tissue depression at the inoculation site were observed in both tomato varieties with isolates that caused pith necrosis, mainly in isolates LTM 13.1.2 and LTM 78.3.2 (

Figure 1b).

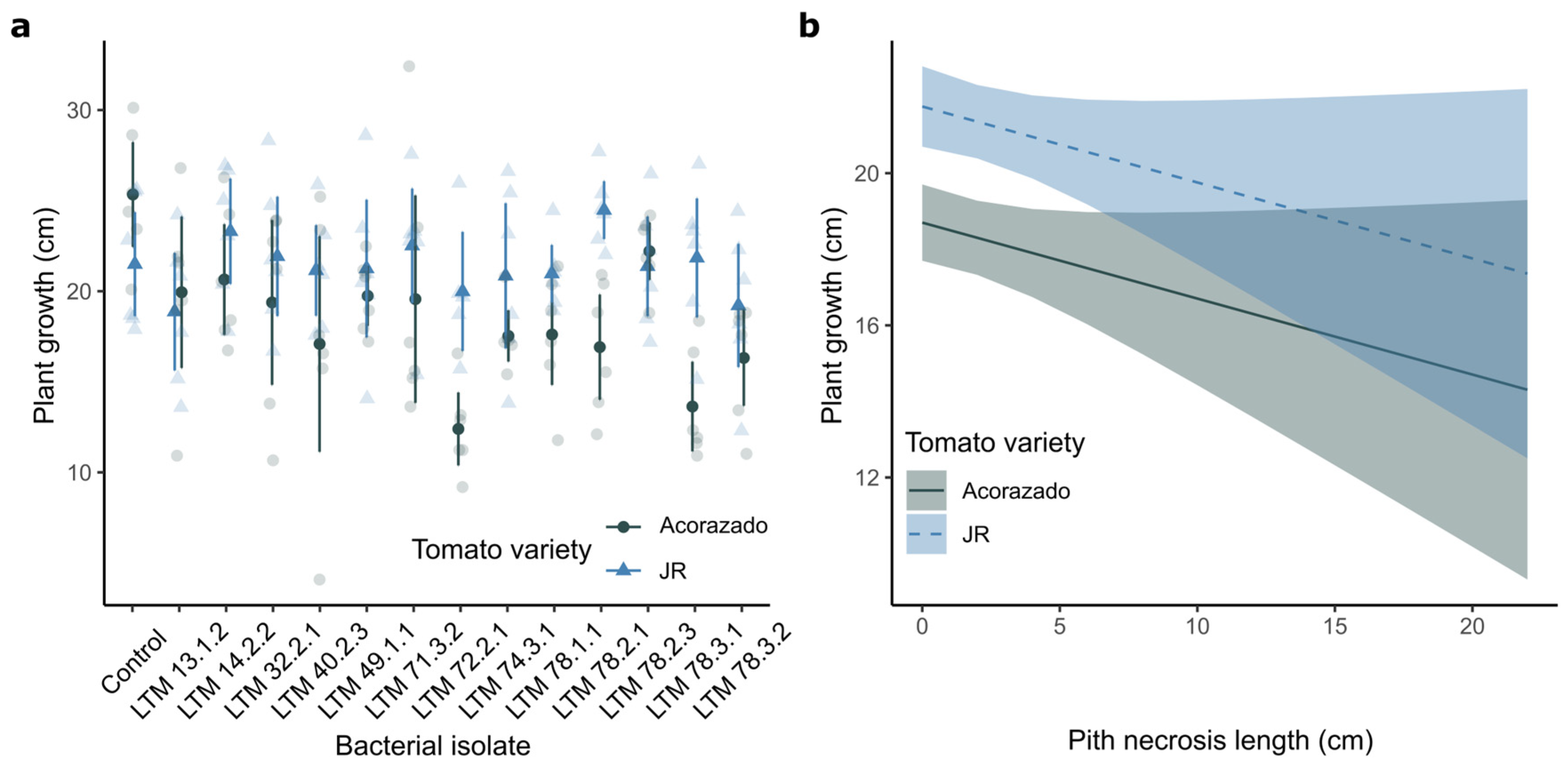

Plant growth (

) was variable, ranging from 4.1 to 32.4 cm, with a mean of 19.91 ± 0.36 cm. Plants of the “Acorazado” variety inoculated with

Cedecea sp. LTM 72.2.1 showed the lowest average growth (12.38 ± 2.01 cm), followed by those inoculated with

Pantoea sp. LTM 78.3.1 (13.62 ± 2.48 cm) of the same variety (

Table 1). The highest growth was recorded in the control plants of the “Acorazado” variety (25.33 ± 2.89 cm) and plants of the “JR” variety inoculated with

Pseudomonas straminea LTM 78.2.1 (24.47 ± 1.60 cm). A general trend of lower growth was observed in most plants of the “Acorazado” variety compared to those of the “JR” variety when inoculated with the same isolate, with significant differences (p < 0.05) for isolates LTM 72.2.1, LTM 78.2.1, and LTM 78.3.1 (

Table 1,

Figure 2a).

The effect of internal lesion on plant growth was analyzed, and although an average reduction of -0.20 ± 0.12 cm (mean ± standard error) was observed for each cm increase in internal lesion, it was not statistically significant (p > 0.05). However, a significant difference in growth between varieties was found (p < 0.05) (

Table S4,

Figure 2b).

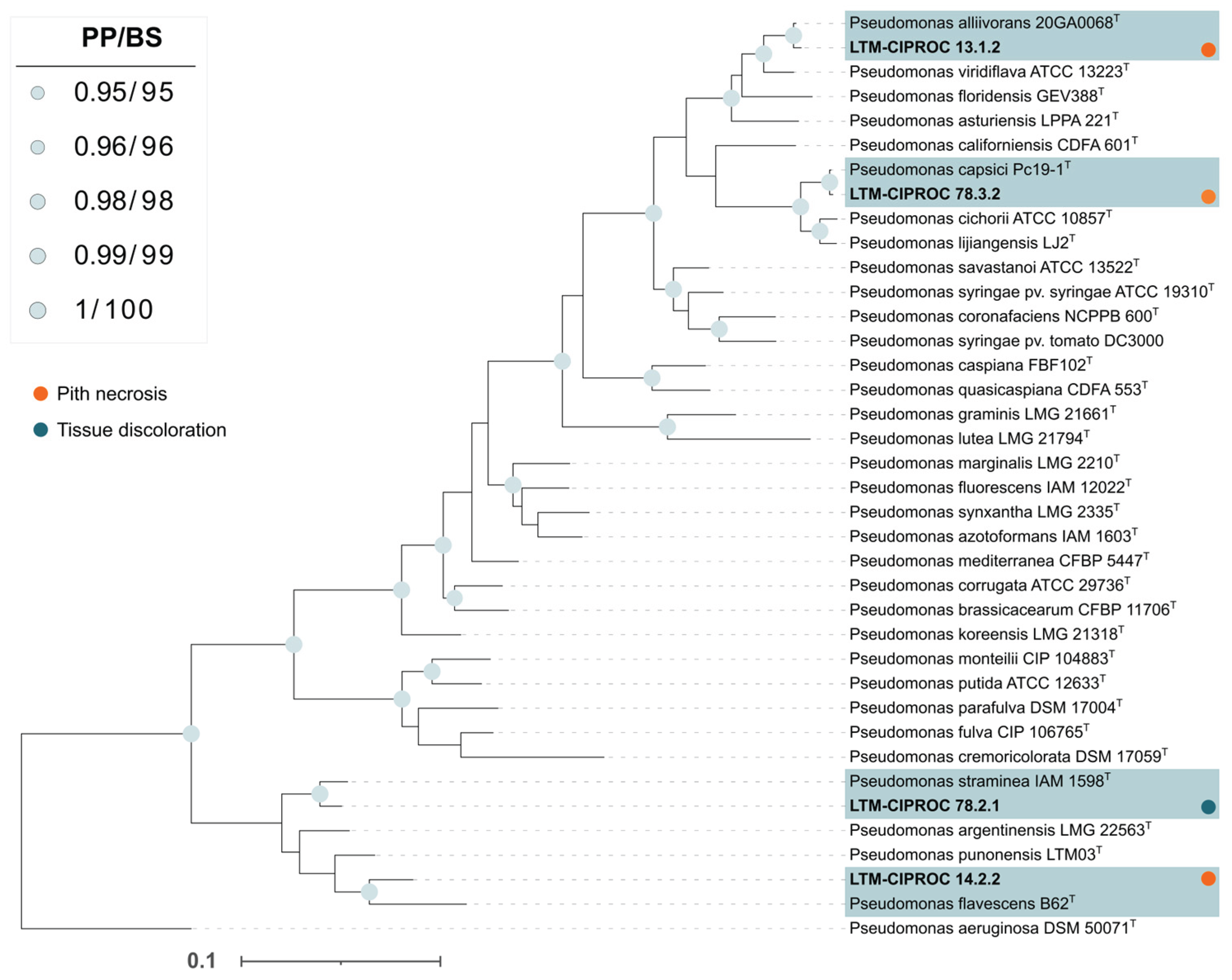

3.2. Taxonomic Classification and Phylogenetics

The taxonomic classification of pathogenic bacteria using the Multilocus Sequence Analysis (MLSA) method yielded the following results: the isolate LTM 13.1.2 was identified as

Pseudomonas alliivorans, isolate LTM 78.3.2 as

Pseudomonas capsici, isolate LTM 14.2.2 as

P. flavescens, and isolate LTM 78.2.1 as

P. straminea (

Figure 3); isolate LTM 72.2.1 was identified as

Cedecea sp. (

Figure S2).

3.3. Genome Sequencing and Analysis

Genome sequencing of the two most virulent isolates using Illumina technology results in a genome assembly size of 6.15 Mb for isolate LTM 13.1.2 with a coverage of 143X, and 5.87 Mb for isolate LTM 78.3.2 with a coverage of 146X. The number of contigs in each genome assembly were 52 and 54. The N50 of the assemblies were 249,463 bp and 182,980 bp. The total number of predicted genes in each genome were 5,527 and 5,000. The GC content of the genomes was 59.1% and 58.37%, respectively (

Table S5). Taxonomic classification of the isolates was confirmed with GTDB-Tk tool and database, the Average Nucleotide Identity (ANI) shows that isolate LTM 13.1.2 has an ANI value of 98.86% when compared to

P. alliivorans 20GA0068

T, and isolate LTM 78.3.2 has an ANI value of 99.53% when compared to

P. capsici Pc19-1

T.

Virulence factors and the gene clusters associated with secondary metabolites were annotated for each genome assembly. Twenty-eight genes related to virulence factors such as Type IV pili (T4P), alginate biosynthesis (mucoid exopolysaccharide), pyoverdine (siderophore) and flagella were detected in the genome of

P. alliivorans LTM 13.1.2. For

P. capsici LTM 78.3.2 genome assembly, thirty genes associated with virulence factors including T4P, Tap T4P, alginate, pyoverdine and flagella were detected (

Table S6).

Regarding biosynthetic gene clusters, eleven clusters associated with secondary metabolites were detected in

P. alliivorans LTM 13.1.2 genome, including arylpolyene, hydrogen cyanide, Non-ribosomal peptide synthetase (NRPS) and polyketide synthase (PKS) products, siderophores, N-acetylglutaminylglutamine amide (NAGGN), a redox-cofactor, a terpene, and several NRPS-derived compounds. In

P. capsici LTM 78.3.2 genome, fourteen clusters were identified, comprising NRPS, PKS, siderophores, NAGGN, arylpolyene, hydrogen cyanide, a redox-cofactor, and diverse NRPS-derived products (

Table S7).

4. Discussion

This study provides the first evidence of several bacterial species affecting tomato plants in Costa Rica.

Pseudomonas alliivorans, recently described associated with foliar symptoms in onion and cucurbits [

65,

66], is reported here for the first time as a causal agent of pith necrosis in tomato. Likewise,

P. capsici, a species associated with foliar diseases in a wide range of hosts [

65,

67,

68,

69], is also reported for the first time causing tomato pith necrosis, as well as its presence in Costa Rica, with the additional relevance that it can induce symptoms at higher temperatures compared to other species like

Pseudomonas syringae [

65]. Given the symptoms induced by these isolates at early stages of tomato cultivation under experimental conditions, further evaluation of their effect on crop yield is necessary, despite the fact that some studies have reported that such symptomatology caused by related species like

P. viridiflava does not always result in significant yield losses [

70]. Furthermore, the ability to colonize both foliar and vascular tissues underscores the potential phytosanitary risk these bacteria pose not only to tomato but also to other solanaceous crops in tropical environments. Consequently, it is imperative to implement monitoring strategies to prevent their spread, as well as effective management strategies.

The phylogenetic proximity between

P. alliivorans with

P. viridiflava [

66] and

P. capsici with

P. cichorii [

68], well-known tomato pathogens [

16,

17,

24,

25], raises the possibility of historical misidentifications in different regions of the world, as has occurred with several

Pseudomonas species [

71]. Moreover, recent taxonomic revisions showed that some strains previously identified as

Pseudomonas cichorii are in fact

P. capsici [

69], reinforcing the need for accurate molecular identification and ongoing epidemiological surveillance to correctly map pathogen distributions in tomato-producing regions.

The recovery of

P. flavescens from symptomatic tomato plants further illustrates the growing diversity of

Pseudomonas taxa capable of colonizing and damaging tomato vascular tissues. As with the previous isolates, this is the first report of

P. flavescens causing pith necrosis in tomato. Although this species has been only sporadically reported in association with other hosts [

72,

73], their association here with necrosis suggests it may contribute to a broader disease complex in tomato.

Although some isolates exhibited low virulence under greenhouse conditions, their detection in symptomatic tissue should not be dismissed as incidental. Opportunistic bacteria detected in this study causing only tissue discoloration, such as

Pseudomonas straminea and

Cedecea sp., may act as secondary colonizers or potentially emerge as pathogens under specific environmental or host conditions [

20,

74]. The presence of pathogens of different taxonomic groups and that its pathogenicity in vegetables has not been reported, such as

Cedecea sp. [

75,

76], underscores the importance of genomic and functional characterization to determine pathogenic potential and epidemiological relevance in vegetable crops.

Importantly, previously reported synergistic interactions among

Pseudomonas spp. such as

P. straminea with other pathogenic

Pseudomonas species and with

Xanthomonas perforans [

20,

77] suggest that field outbreaks may frequently involve multispecies infections that act together to exacerbate symptoms. This factor may complicate diagnosis and reduce the effectiveness of single-target control measures.

The bacterial isolates that caused pith necrosis also triggered external symptoms such as tissue discoloration and sunken lesions at the inoculation site, similar to those described for other causal agents of pith necrosis [

16,

32]. Although the formation of adventitious roots on the stem was not observed, this symptom may emerge in later stages of the crop cycle [

16,

32,

78]; therefore, evaluations throughout the entire production cycle are suggested to capture the complete symptomatology and its temporal dynamics.

The variability in plant growth observed across treatments suggests that the response to bacterial inoculation is not uniform and may be influenced by multiple factors, including the intrinsic physiological variability between plants [

79]. Although a general trend of reduced growth was observed in the “Acorazado” variety compared to the “JR”, this pattern was not evident in the control plants, indicating that the variety itself may not be inherently less vigorous but rather may be more sensitive or susceptible to specific microbial interactions [

80]. Notably, inoculation with highly virulent isolates did not result in measurable reductions in plant growth, suggesting that internal damage is not always associated with immediate loss in vegetative development, at least within the evaluation period.

The genome analysis of the two most virulent isolates revealed the presence of several virulence factors and biosynthetic gene clusters that may confer a competitive advantage as plant pathogens. Some of those genomic traits have been reported in well-known plant pathogenic bacteria and contribute to their pathogenicity and virulence [

81,

82,

83,

84]. Phytotoxin syringomycin detected in one isolate has been associated with necrosis promotion in the host and enhancement of bacterial growth in a wide variety of plants [

85]. This toxin along with virulence factors may be involved in the highly virulence expressed. Furthermore, genomic traits implicated in protection against plant defense mechanisms [

86,

87,

88], microbial competition [

89,

90], and environmental stress tolerance [

91,

92,

93,

94] may benefit these isolates in microbe-microbe interactions and provide them efficient ways for epiphytic and environmental survival. Despite the damage observed in plants, the present study does not provide evidence that these virulence genes are expressed under in vitro or in vivo conditions.

This study represents the first systematic effort in Costa Rica to identify bacteria associated with tomato pith necrosis. The findings of this study contribute to the existing body of knowledge by including new species of pathogenic bacteria that have been observed to cause pith necrosis in tomato plants. This suggests that the range of causal agents may be broader than previously recognized, and that there are potentially additional unidentified species present. Furthermore, the presence of bacteria that cause tissue discoloration could weaken the plant and make it more susceptible to attack by more aggressive pathogens. All of the above highlights the importance of considering aspects such as the identity and virulence of pathogenic organisms when diagnosing and implementing plant health management strategies.

5. Conclusions

Five bacterial isolates were identified as causal agents of internal symptoms in tomato: Pseudomonas alliivorans LTM 13.1.2, P. flavescens LTM 14.2.2, and P. capsici LTM 78.3.2 caused pith necrosis, while Cedecea sp. LTM 72.2.1 and P. straminea LTM 78.2.1 caused tissue discoloration. P. alliivorans LTM 13.1.2 was the most virulent isolate, followed by P. capsici LTM 78.3.2. Genome sequences of the most virulent isolates revealed several virulence factors and gene clusters associated with secondary metabolites that may contribute to the pathogenicity of these isolates, while also providing a competitive advantage over other microbes and enhancing environmental survival.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org, Table S1. Primers used for the amplification and partial sequencing of the

16S rRNA,

gyrB,

rpoD, and

rpoB genes; Table S2. Reference strains used in the Multilocus Sequence Analysis (MLSA). Partial sequences of the

16S rRNA,

gyrB,

rpoD, and

rpoB genes from type strains were retrieved from the GenBank database of the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI); Table S3. Reference strains used in the phylogenetic analysis for the identification of isolate LTM 72.2.1 and the non-pathogenic isolates. Partial sequences of the

16S rRNA gene from type strains were retrieved from the GenBank database of the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI); Table S4. Effect of pith necrosis length (cm) on plant growth (

; [cm]) in the tomato varieties “Acorazado” and “JR” at 21 days after inoculation (dai) under greenhouse conditions.; [cm]) in the tomato varieties “Acorazado” and “JR” at 21 days after inoculation (dai) under greenhouse conditions; Table S5. Assembly statistics, genome features and genome annotation summary for

Pseudomonas alliivorans LTM 13.1.2 and

Pseudomonas capsici LTM 78.3.2; Table S6. Virulence genes detected in

Pseudomonas alliivorans LTM 13.1.2 and

Pseudomonas capsici LTM 78.3.2 genomes; Table S7. Gene clusters associated with secondary metabolites annotated for the

Pseudomonas alliivorans LTM 13.1.2 and

Pseudomonas capsici LTM 78.3.2 genome assemblies; Figure S1. Vascular tissue discoloration in tomato plants inoculated with bacterial isolates, evaluated 21 days after inoculation (dai).

Pseudomonas straminea LTM 78.2.1 in var. “JR” (i) and var. “Acorazado” (ii);

Cedecea sp. LTM 72.2.1 in var. “JR” (iii) and var. “Acorazado” (iv); Control in var. “JR” (v) and var. “Acorazado” (vi); Figure S2. Consensus phylogenetic tree constructed from partial

16S rRNA gene sequences of isolate LTM 72.2.1, which caused tissue discoloration, and non-pathogenic isolates. Isolates analyzed in this study are shown in bold with the acronym ‘LTM-CIPROC’ (Molecular Techniques Laboratory, CIPROC-UCR) and shaded. The topology of the Bayesian phylogenetic analysis is shown. Circles at the nodes indicate combined support values (PP = Bayesian posterior probability ≥ 0.80; BS = Maximum Likelihood bootstrap support ≥ 80%).

T = Type strain. The scale bar represents the estimated number of substitutions per site.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.A-R., M.B-M., F.G-S. and W.B-S.; methodology, D.A-R., M.B-M., F.G-S. and G.VA.; software, D.A-R. and G.VA.; validation, D.A-R., M.B-M., F.G-S and G.VA.; formal analysis, D.A-R. and G.VA.; investigation, D.A-R. and G.VA.; resources, D.A-R., M.B-M., F.G-S., W.B-S. and G.VA.; data curation, D.A-R. and G.VA.; writing—original draft preparation, D.A-R.; writing—review and editing, D.A-R., M.B-M., G.VA., F.G-S. and W.B-S.; visualization, D.A-R.; supervision, M.B-M.; project administration, M.B-M.; funding acquisition, M.B-M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Vicerrectoría de Investigación de la Universidad de Costa Rica, grant number 813-C0-466. The APC was funded by Vicerrectoría de Investigación de la Universidad de Costa Rica.

Data Availability Statement

All data analyzed during this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We want to express our acknowledgments to the producers of the Cartago, Alajuela, and Heredia areas for facilitating tomato samples. To Anny Calderón-Abarca, Gabriela Chinchilla-Salazar, Alejandro Sebiani-Calvo, Edgar Vargas, Carlos Chacón and Yeimy Ramírez for their technical support in laboratory procedures.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- FAOSTAT Estadísticas de Cultivos y Productos de Ganadería. Organ. Las N. U. Para Aliment. Agric. FAO Base Datos FAOSTAT 2024. https://www.fao.org/faostat/es/#data/QCL.

- INEC Encuesta Nacional Agropecuaria 2018: Resultados Generales de La Actividad Agrícola y Forestal 2019, 81.

- Costa, J.M.; Heuvelink, E. The Global Tomato Industry. In Tomatoes; Heuvelink, E., Ed.; CAB International, 2018; pp. 1–26.

- Heuvelink, E.; Li, T.; Dorais, M. Crop Growth and Yield. In Tomatoes; Heuvelink, E., Ed.; CAB International, 2018; pp. 89–136.

- Shamshiri, R.R.; Jones, J.W.; Thorp, K.R.; Ahmad, D.; Man, H.C.; Taheri, S. Review of Optimum Temperature, Humidity, and Vapour Pressure Deficit for Microclimate Evaluation and Control in Greenhouse Cultivation of Tomato: A Review. Int. Agrophysics 2018, 32, 287–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kannan, V.R.; Bastas, K.K.; Antony, R. Plant Pathogenic Bacteria: An Overview. In Sustainable Approaches to Controlling Plant Pathogenic Bacteria; Kannan, V.R., Bastas, K.K., Eds.; CRC Press, 2016.

- Mansfield, J.; Genin, S.; Magori, S.; Citovsky, V.; Sriariyanum, M.; Ronald, P.; Dow, M.; Verdier, V.; Beer, S.V.; Machado, M.A.; et al. Top 10 Plant Pathogenic Bacteria in Molecular Plant Pathology. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2012, 13, 614–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuliar; Nion, Y. A.; Toyota, K. Recent Trends in Control Methods for Bacterial Wilt Diseases Caused by Ralstonia solanacearum. Microbes Environ. 2015, 30, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strange, R.N.; Scott, P.R. Plant Disease: A Threat to Global Food Security. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2005, 43, 83–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundström, J.F.; Albihn, A.; Boqvist, S.; Ljungvall, K.; Marstorp, H.; Martiin, C.; Nyberg, K.; Vågsholm, I.; Yuen, J.; Magnusson, U. Future Threats to Agricultural Food Production Posed by Environmental Degradation, Climate Change, and Animal and Plant Diseases – a Risk Analysis in Three Economic and Climate Settings. Food Secur. 2014, 6, 201–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco-Meneses, M.; Castro-Zúñiga, O.; Calderón-Abarca, A. Diagnóstico Del Uso de Antibióticos En Regiones Productoras de Tomate En Costa Rica. Agron. Costarric. 2023, 47, 87–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MAG Tomate: Manual de Buenas Prácticas Agrícolas Con Enfoque de Adaptación al Cambio Climático 2024, 141.

- SFE Lista de Enfermedades de Los Cultivos Agrícolas y Forestales de Costa Rica, 2009 2009.

- Scarlett, C.M.; Fletcher, J.T.; Roberts, P.; Lelliot, R.A. Tomato Pith Necrosis Caused by Pseudomonas corrugata n. sp. Ann. Appl. Biol. 1978, 88, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catara, V.; Sutra, L.; Morineau, A.; Achouak, W.; Christen, R.; Gardan, L. Phenotypic and Genomic Evidence for the Revision of Pseudomonas Corrugata and Proposal of Pseudomonas mediterranea sp. nov. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2002, 52, 1749–1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trantas, E.A.; Sarris, P.F.; Mpalantinaki, E.E.; Pentari, M.G.; Ververidis, F.N.; Goumas, D.E. A New Genomovar of Pseudomonas cichorii, a Causal Agent of Tomato Pith Necrosis. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2013, 137, 477–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, F.P. Pith Necrosis Associated with Pseudomonas viridiflava in Tomato Plants in Brazil. Plant Pathol. Quar. 2019, 9, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bella, P.; Catara, V. Occurrence of Tomato Pith Necrosis Caused by Pseudomonas marginalis in Italy. Plant Pathol. 2010, 59, 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mota, L.C.B.; Tebaldi, N.D.; Luz, J.M.Q. Occurrence of Pseudomonas fluorescens and P. putida Associated to Tomato Pith Necrosis in Brazil. Hortic. Bras. 2021, 39, 258–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiello, D.; Scuderi, G.; Vitale, A.; Firrao, G.; Polizzi, G.; Cirvilleri, G. A Pith Necrosis Caused by Xanthomonas perforans on Tomato Plants. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2013, 137, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruso, A.; Licciardello, G.; Rosa, R.L.; Catara, V.; Bella, P. Mixed Infection of Pectobacterium carotovorum subsp. carotovorum and P. carotovorum subsp. brasiliensis in Tomato Stem Rot in Italy. J. Plant Pathol. 2016, 98, 661–665. [Google Scholar]

- CABI Pseudomonas corrugata (Pith Necrosis of Tomato). PlantwisePlus Knowl. Bank 2022, Species Pa. [CrossRef]

- Quezado-Duval, A.M.; Guimarães, C.M.N.; Martins, O.M. Occurrence of Pseudomonas corrugata Causing Pith Necrosis on Tomato Plants in Goiás, Brazil. Fitopatol. Bras. 2007, 32, 520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alippi, A.M.; Bo, E.D.; Ronco, L.B.; López, M.V.; López, A.C.; Aguilar, O.M. Pseudomonas Populations Causing Pith Necrosis of Tomato and Pepper in Argentina Are Highly Diverse. Plant Pathol. 2003, 52, 287–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvera-Pérez, E.; Maeso, D.; Catara, V.; Rubio, L.; Leoni, C.; Amaral, J.; Estelda, C.; Hernández, M.; Bóffano, L.; González, P. Pseudomonas spp. Associated with Tomato Pith Necrosis in the Salto Area, Northwest Uruguay. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2023, 165, 715–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Alvarado, G.; Holguín-Peña, J.; Ochoa-Álvarez, N.; Fernández-Pavía, S.P.; Geraldo-Verdugo, J.A. Pseudomonas corrugata Causing Pith Necrosis on Tomato Plants in Baja California Sur, México. Plant Dis. 2002, 86, 563–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, W.P.; Black, L.L. Tomato Pith Necrosis (Pseudomonas corrugata) in Field-Grown Tomatoes in Louisiana. Plant Dis. 1986, 70, 1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, J.B. Ocurrence of Stem Necrosis on Field-Grown Tomatoes Incited by Pseudomonas corrugata in Florida. Plant Dis. 1983, 67, 425–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, M.; Opgenorth, D.C.; White, J.B. Occurrence of Pseudomonas corrugata on Tomato in California. Plant Dis. 1983, 67, 110–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, M.; Gundersen, B.; Miles, C.A.; Humann, J.L.; Schroeder, B.K.; Inglis, D.A. First Report of Tomato Pith Necrosis (Pseudomonas corrugata) on Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) in Washington. Plant Dis. 2013, 97, 1381–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Baysal-Gurel, F.; Miller, S.A. First Report of Tomato Pith Necrosis Caused by Pseudomonas mediterranea in the United States and P. corrugata in Ohio. Plant Dis. 2013, 97, 988–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catara, V. Pseudomonas corrugata: Plant Pathogen and/or Biological Resource? Mol. Plant Pathol. 2007, 8, 233–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moura, M.L.; Brito, L.M.; Mourão, I.M.; Jacques, M.A.; Duclos, J. Tomato Pith Necrosis (TPN) Caused by P. corrugata and P. mediterranea: Severity of Damages and Crop Loss Assessment. Acta Hortic. 2005, 695, 365–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora Vargas, P. Mora Vargas, P. Nuevo Tipo de Tomate Podría Salvar Hasta Un 75 % de Las Cosechas. Portal de la Investigación-Vicerrectoría de Investigación UCR 2023. Available online: https://www.ucr.ac.cr/noticias/2023/12/12/nuevo-tipo-de-tomate-podria-salvar-hasta-un-75-de-las-cosechas.html (accessed on 19 September 2025).

- Aysan, Y.; Yildiz, N.; Yucel, F. Identification of Pseudomonas viridiflava on Tomato by Traditional Methods and Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay. Phytoparasitica 2004, 32, 146–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, D.J. 16S/23S rRNA Sequencing. In Nucleic acid techniques in bacterial systematics; Stackebrandt, E., Goodfellow, M., Eds.; John Wiley and Sons, 1991; pp. 115–175.

- Yamamoto, S.; Kasai, H.; Arnold, D.L.; Jackson, R.W.; Vivian, A.; Harayama, S. Phylogeny of the Genus Pseudomonas: Intrageneric Structure Reconstructed from the Nucleotide Sequences of gyrB and rpoD Genes. Microbiology 2000, 146, 2385–2394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulet, M.; Bennasar, A.; Lalucat, J.; García-Valdés, E. An rpoD-Based PCR Procedure for the Identification of Pseudomonas Species and for Their Detection in Environmental Samples. Mol. Cell. Probes 2009, 23, 140–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tayeb, L.A.; Ageron, E.; Grimont, F.; Grimont, P.A.D. Molecular Phylogeny of the Genus Pseudomonas Based on rpoB Sequences and Application for the Identification of Isolates. Res. Microbiol. 2005, 156, 763–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyle, J.J.; Doyle, J.L. Isolation of Plant DNA from Fresh Tissue. Focus 1990, 12, 13–15. [Google Scholar]

- Trout, C.L.; Ristaino, J.B.; Madritch, M.; Wangsomboondee, T. Rapid Detection of Phytophthora infestans in Late Blight-Infected Potato and Tomato Using PCR. Plant Dis. 1997, 81, 1042–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanger, F.; Coulson, A.R. A Rapid Method for Determining Sequences in DNA by Primed Synthesis with DNA Polymerase. J. Mol. Biol. 1975, 94, 441–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, T.A. BioEdit: A User-Friendly Biological Sequence Alignment Editor and Analysis Program for Windows 95/98/NT. Nucleic Acids Symp. Ser. 1999, 41, 95–98. [Google Scholar]

- Katoh, K.; Rozewicki, J.; Yamada, K.D. MAFFT Online Service: Multiple Sequence Alignment, Interactive Sequence Choice and Visualization. Brief. Bioinform. 2017, 20, 1160–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maddison, W.P.; Maddison, D.R. Mesquite: A Modular System for Evolutionary Analysis. 2019.

- Darriba, D.; Taboada, G.L.; Doallo, R.; Posada, D. jModelTest 2: More Models, New Heuristics and Parallel Computing. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ronquist, F.; Teslenko, M.; Mark, P.V.D.; Ayres, D.L.; Darling, A.; Höhna, S.; Larget, B.; Liu, L.; Suchard, M.A.; Huelsenbeck, J.P. MrBayes 3.2: Efficient Bayesian Phylogenetic Inference and Model Choice across a Large Model Space. Syst. Biol. 2012, 61, 539–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamatakis, A. RAxML Version 8: A Tool for Phylogenetic Analysis and Post-Analysis of Large Phylogenies. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 1312–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edler, D.; Klein, J.; Antonelli, A.; Silvestro, D. raxmlGUI 2.0: A Graphical Interface and Toolkit for Phylogenetic Analyses Using RAxML. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2021, 12, 373–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letunic, I.; Bork, P. Interactive Tree of Life (iTOL) v6: Recent Updates to the Phylogenetic Tree Display and Annotation Tool. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolger, A.M.; Lohse, M.; Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: A Flexible Trimmer for Illumina Sequence Data. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2114–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wick, R.R.; Judd, L.M.; Gorrie, C.L.; Holt, K.E. Unicycler: Resolving Bacterial Genome Assemblies from Short and Long Sequencing Reads. PLOS Comput. Biol. 2017, 13, e1005595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikheenko, A.; Prjibelski, A.; Saveliev, V.; Antipov, D.; Gurevich, A. Versatile Genome Assembly Evaluation with QUAST-LG. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, i142–i150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaumeil, P.-A.; Mussig, A.J.; Hugenholtz, P.; Parks, D.H. GTDB-Tk v2: Memory Friendly Classification with the Genome Taxonomy Database. Bioinformatics 2022, 38, 5315–5316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantalapiedra, C.P.; Hernández-Plaza, A.; Letunic, I.; Bork, P.; Huerta-Cepas, J. eggNOG-Mapper v2: Functional Annotation, Orthology Assignments, and Domain Prediction at the Metagenomic Scale. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2021, 38, 5825–5829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blin, K.; Shaw, S.; Vader, L.; Szenei, J.; Reitz, Z.L.; Augustijn, H.E.; Cediel-Becerra, J.D.D.; Crécy-Lagard, V. de; Koetsier, R.A.; Williams, S.E.; et al. antiSMASH 8.0: Extended Gene Cluster Detection Capabilities and Analyses of Chemistry, Enzymology, and Regulation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, 53, W32–W38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, W.; Fan, X.; Guo, Y.; Wang, S.; Jia, S.; Lv, N.; Yuan, T.; Pan, Y.; Xue, Y.; Chen, X.; et al. An Expanded Database and Analytical Toolkit for Identifying Bacterial Virulence Factors and Their Associations with Chronic Diseases. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 8084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvarado-Rodríguez, D.; Vargas Asensio, G.; Blanco-Meneses, M. Draft Genomes of Two Pathogenic Pseudomonas spp. Strains Isolated from Tomato Plants. Microbiol. Resour. Announc. submitted.

- R Core Team R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing 2024.

- Lüdecke, D.; Ben-Shachar, M.S.; Patil, I.; Waggoner, P.; Makowski, D. Performance: An R Package for Assessment, Comparison and Testing of Statistical Models. J. Open Source Softw. 2021, 6, 3139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Mendiburu, F. Agricolae: Statistical Procedures for Agricultural Research 2023.

- Lüdecke, D. Ggeffects: Tidy Data Frames of Marginal Effects from Regression Models. J. Open Source Softw. 2018, 3, 772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lüdecke, D. sjPlot: Data Visualization for Statistics in Social Science 2023.

- Wickham, H. Ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis; Springer-Verlag New York, 2016; ISBN 978-3-319-24277-4.

- Fullem, K.R.; Pena, M.M.; Potnis, N.; Goss, E.M.; Minsavage, G.V.; Iriarte, F.B.; Holland, A.; Jones, J.B.; Paret, M.L. Unexpected Diversity of Pseudomonads Associated with Bacterial Leaf Spot of Cucurbits in the Southeastern United States. Plant Dis. 2024, 108, 592–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Tyson, C.; Chen, H.-C.; Paudel, S.; Gitaitis, R.; Kvitko, B.; Dutta, B. Pseudomonas alliivorans sp. nov., a Plant-Pathogenic Bacterium Isolated from Onion Foliage in Georgia, USA. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 2022, 45, 126278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, H.; Lee, S.Y.; Lee, B.W.; Ham, H.; Lee, M.-H.; Lee, Y.K. First Report of Bacterial Spot Disease Caused by Pseudomonas capsici on Castor Bean in Korea. Res. Plant Dis. 2023, 29, 440–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Koirala, S.; Chen, H.-C.; Gitaitis, R.; Kvitko, B.; Dutta, B. Pseudomonas capsici sp. nov., a Plant-Pathogenic Bacterium Isolated from Pepper Leaf in Georgia, USA. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2021, 71, 004971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, M.; Gitaitis, R.; Dutta, B. Characterization of Pseudomonas capsici Strains from Pepper and Tomato. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1267395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monteiro, F.P.; Ogoshi, C.; Cardoso, D.A.; Perazolli, V. Pith Necrosis of Tomato Caused by Pseudomonas viridiflava May Not Decrease Production. Asian J. Agric. Hortic. Res. 2019, 4, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, P.N.; Savka, M.A.; Gan, H.M. In-Silico Taxonomic Classification of 373 Genomes Reveals Species Misidentification and New Genospecies within the Genus Pseudomonas. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hildebrand, D.C.; Palleroni, N.J.; Hendson, M.; Toth, J.; Johnson, J.L. Pseudomonas flavescens sp. nov., Isolated from Walnut Blight Cankers. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 1994, 44, 410–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.S.; Lee, D.-H.; Lee, S.K.; Lee, S.-H.; Seo, S.-T. First Report of Walnut Blight Canker on Walnut Tree (Juglans regia) by Pseudomonas flavescens in South Korea. J. Plant Pathol. 2020, 102, 943–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimartino, M.; Panebianco, S.; Vitale, A.; Castello, I.; Leonardi, C.; Cirvilleri, G.; Polizzi, G. Occurrence and Pathogenicity of Pseudomonas fluorescens and P. putida on Tomato Plants in Italy. J. Plant Pathol. 2011, 93, 79–87. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Z.; Huang, Y.; Nie, Y.; Liu, B. Biological Characteristics of Two Pathogens Causing Brown Blotch in Agaricus bisporus and the Toxin Identification of Cedecea neteri. Phytopathol. Res. 2024, 6, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Zhou, S.; Zhang, W.; Wu, S.; Chen, X.; Wang, X.; Hu, H.; Chen, Q. First Report of Cedecea neteri Causing Yellow Rot Disease in Pleurotus Pulmonarius in China. Plant Dis. 2021, 105, 1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiello, D.; Vitale, A.; Ruota, A.D.L.; Polizzi, G.; Cirvilleri, G. Synergistic Interactions between Pseudomonas spp. and Xanthomonas perforans in Enhancing Tomato Pith Necrosis Symptoms. J. Plant Pathol. 2017, 99, 731–740. [Google Scholar]

- Trantas, E.A.; Sarris, P.F.; Pentari, M.G.; Mpalantinaki, E.E.; Ververidis, F.N.; Goumas, D.E. Diversity among Pseudomonas corrugata and Pseudomonas mediterranea Isolated from Tomato and Pepper Showing Symptoms of Pith Necrosis in Greece. Plant Pathol. 2015, 64, 307–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadras, V.O.; Calderini, D.F. Crop Physiology: Case Histories for Major Crops; Academic Press, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Kover, P.X.; Schaal, B.A. Genetic Variation for Disease Resistance and Tolerance among Arabidopsis thaliana Accessions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2002, 99, 11270–11274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burdman, S.; Bahar, O.; Parker, J.K.; Fuente, L. de la Involvement of Type IV Pili in Pathogenicity of Plant Pathogenic Bacteria. Genes 2011, 2, 706–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merfa, M.V.; Zhu, X.; Shantharaj, D.; Gomez, L.M.; Naranjo, E.; Potnis, N.; Cobine, P.A.; Fuente, L.D.L. Complete Functional Analysis of Type IV Pilus Components of a Reemergent Plant Pathogen Reveals Neofunctionalization of Paralog Genes. PLoS Pathog. 2023, 19, e1011154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogales, J.; Vargas, P.; Farias, G.A.; Olmedilla, A.; Sanjuán, J.; Gallegos, M.T. FleQ Coordinates Flagellum-Dependent and -Independent Motilities in Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato DC3000. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2015, 81, 7533–7545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taguchi, F.; Ichinose, Y. Role of Type IV Pili in Virulence of Pseudomonas syringae pv. tabaci 6605: Correlation of Motility, Multidrug Resistance, and HR-Inducing Activity on a Nonhost Plant. MPMI 2011, 24, 1001–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grenz, K.; Chia, K.S.; Turley, E.K.; Tyszka, A.S.; Atkinson, R.E.; Reeves, J.; Vickers, M.; Rejzek, M.; Walker, J.F.; Carella, P. A Necrotizing Toxin Enables Pseudomonas syringae Infection across Evolutionarily Divergent Plants. Cell Host Microbe 2025, 33, 20–29.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keith, R.C.; Keith, L.M.W.; Hernández-Guzmán, G.; Uppalapati, S.R.; Bender, C.L. Alginate Gene Expression by Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato DC3000 in Host and Non-Host Plants. Microbiology 2003, 149, 1127–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pontes, J.G.D.M.; Fernandes, L.S.; Santos, R.V.D.; Tasic, L.; Fill, T.P. Virulence Factors in the Phytopathogen-Host Interactions: An Overview. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2020, 68, 7555–7570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapicavoli, J.N.; Blanco-Ulate, B.; Muszyński, A.; Figueroa-Balderas, R.; Morales-Cruz, A.; Azadi, P.; Dobruchowska, J.M.; Castro, C.; Cantu, D.; Roper, M.C. Lipopolysaccharide O-Antigen Delays Plant Innate Immune Recognition of Xylella fastidiosa. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Booysen, E.; Rautenbach, M.; Stander, M.A.; Dicks, L.M.T. Profiling the Production of Antimicrobial Secondary Metabolites by Xenorhabdus khoisanae J194 under Different Culturing Conditions. Front. Chem. 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dutta, S.; Yu, S.M.; Lee, Y.H. Assessment of the Contribution of Antagonistic Secondary Metabolites to the Antifungal and Biocontrol Activities of Pseudomonas fluorescens NBC275. Plant Pathol. J. 2020, 36, 491–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burch, A.Y.; Zeisler, V.; Yokota, K.; Schreiber, L.; Lindow, S.E. The Hygroscopic Biosurfactant Syringafactin Produced by Pseudomonas syringae Enhances Fitness on Leaf Surfaces during Fluctuating Humidity. Environ. Microbiol. 2014, 16, 2086–2098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammadi, M.; Burbank, L.; Roper, M.C. Biological Role of Pigment Production for the Bacterial Phytopathogen Pantoea stewartii subsp. stewartii. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2012, 78, 6859–6865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijaya Kumar, S.; Abraham, P.E.; Hurst, G.B.; Chourey, K.; Bible, A.N.; Hettich, R.L.; Doktycz, M.J.; Morrell-Falvey, J.L. A Carotenoid-Deficient Mutant of the Plant-Associated Microbe Pantoea sp. YR343 Displays an Altered Membrane Proteome. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, Y.; Lu, S.; Lou, H.; Wang, X.B.; Wang, W. AlgU Mediates Hyperosmotic Tolerance in Pseudomonas protegens SN15-2 by Regulating Membrane Stability, ROS Scavenging, and Osmolyte Synthesis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2024, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).