Submitted:

29 September 2025

Posted:

30 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Stress is a predisposing factor for pulmonary diseases, but its effects on the lungs of healthy individuals have not been elucidated yet. Since bovine lactoferrin (bLf) is a powerful immunomodulator, in this study, we focused on evaluating whether lactoferrin is able to modulate the effects of chronic stress on humoral and cellular immunity of the lung. We performed a chronic restraint stress (RS) and oral administration of bLf BALB/c model and we evaluated serum corticosterone, body weight and some parameters of lung immunity, such as immunoglobulin concentrations in serum and tracheobronchial lavages (TBL), secretory IgA (S-IgA) levels in TBL, IgA-secreting plasma cells, pIgR relative expression, CD4+ lymphocyte Th1 and Th2 populations and Antigen Presenting Cells (APC) populations on the lung. Our results demonstrate that stress increases corticosterone, production of total IgA and IgG, while decreasing the levels of IgM and S-IgA, promotes a Th1/Th2 profile imbalance, and decreases APC populations. Interestingly, bLf modulates serum corticosterone levels and stress-induced weight loss, and it also modulates humoral and cellular effects produced by chronic stress. These results demonstrated that bLf should be considered as a new therapeutic target for further studies to focus on the prophylactic and co-therapeutic administration to treat and prevent respiratory diseases.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

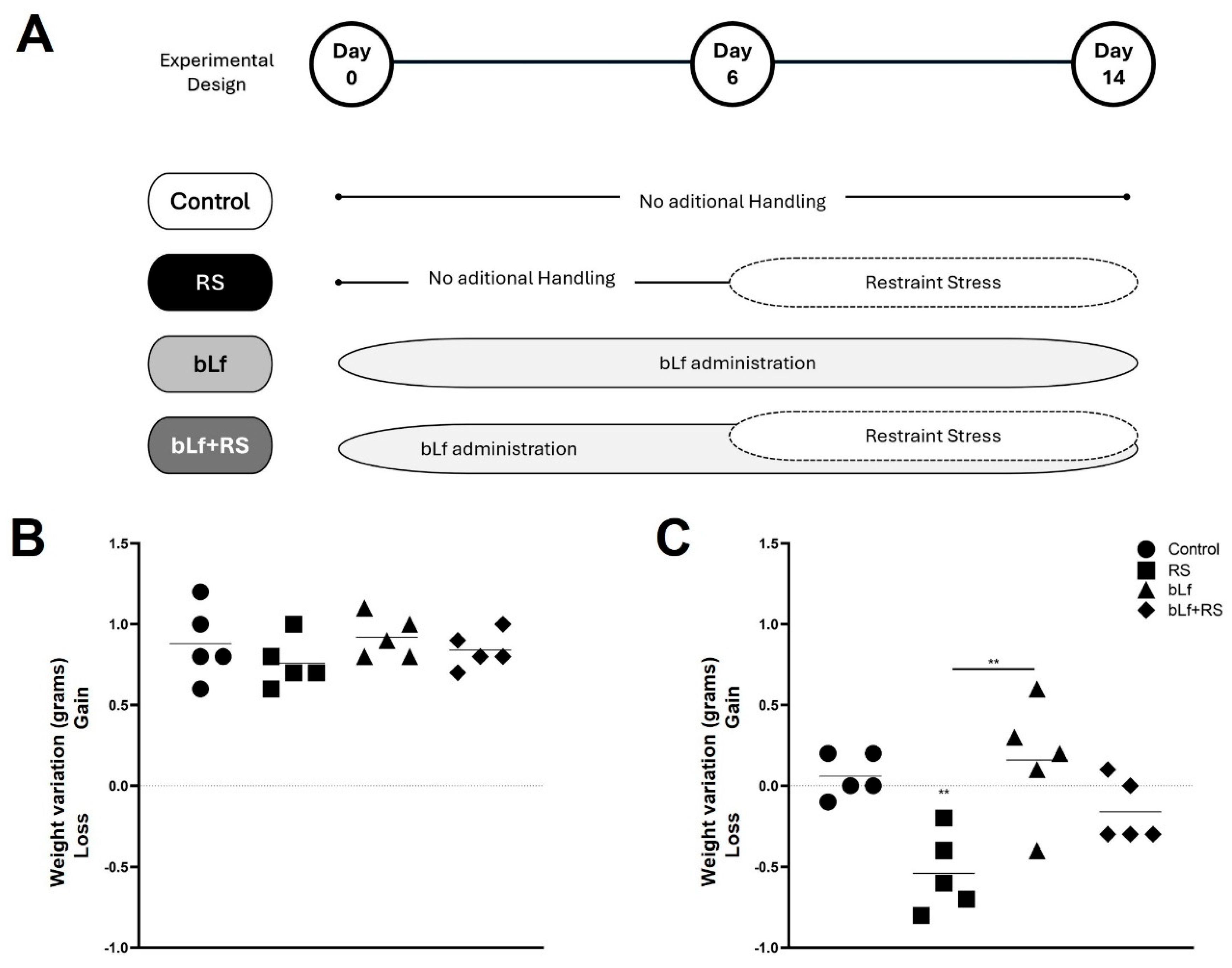

2.1. Bovine Lactoferrin Counteracts Weight Loss Induced by Stress

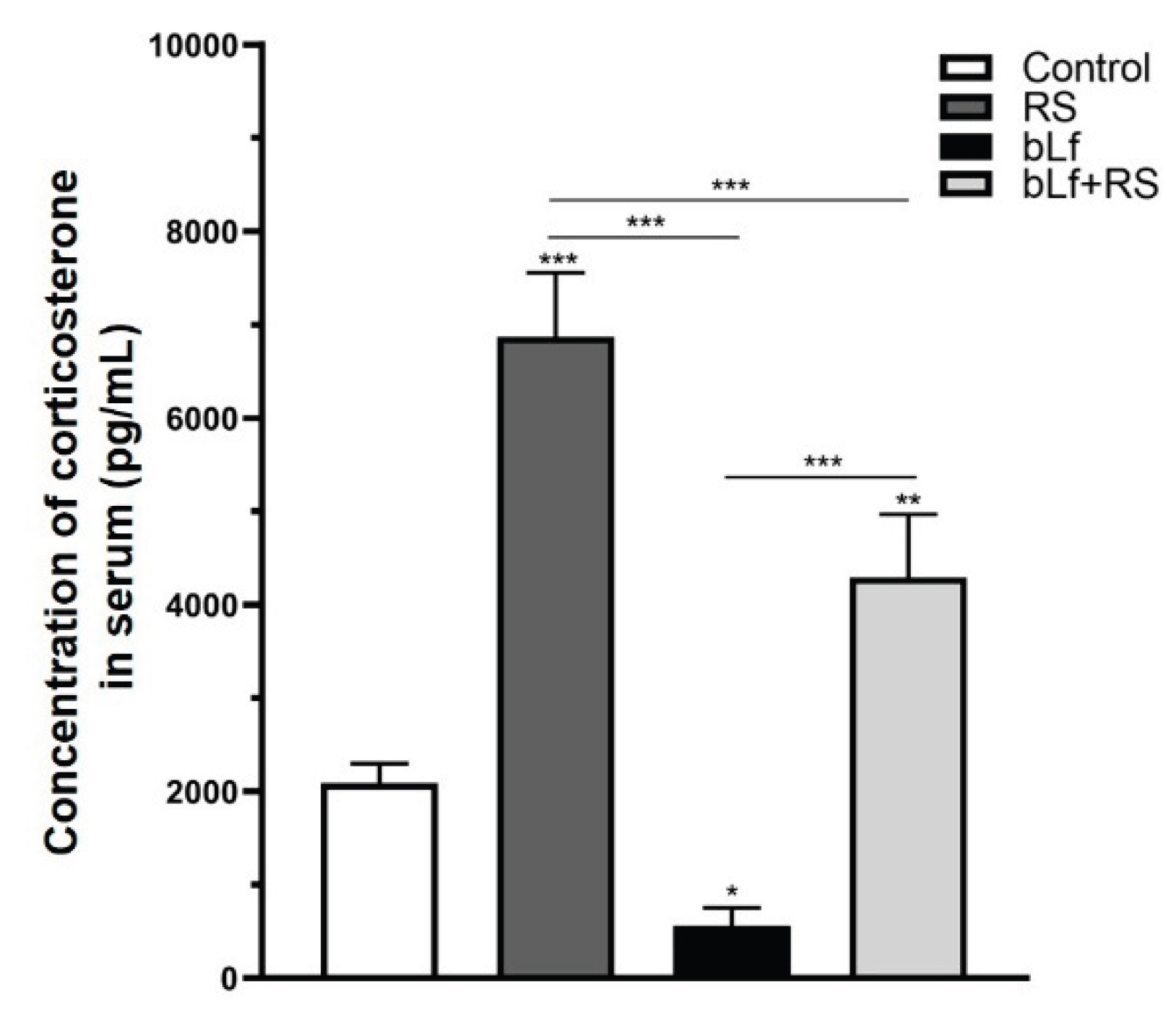

2.2. Bovine Lactoferrin Modulates Corticosterone

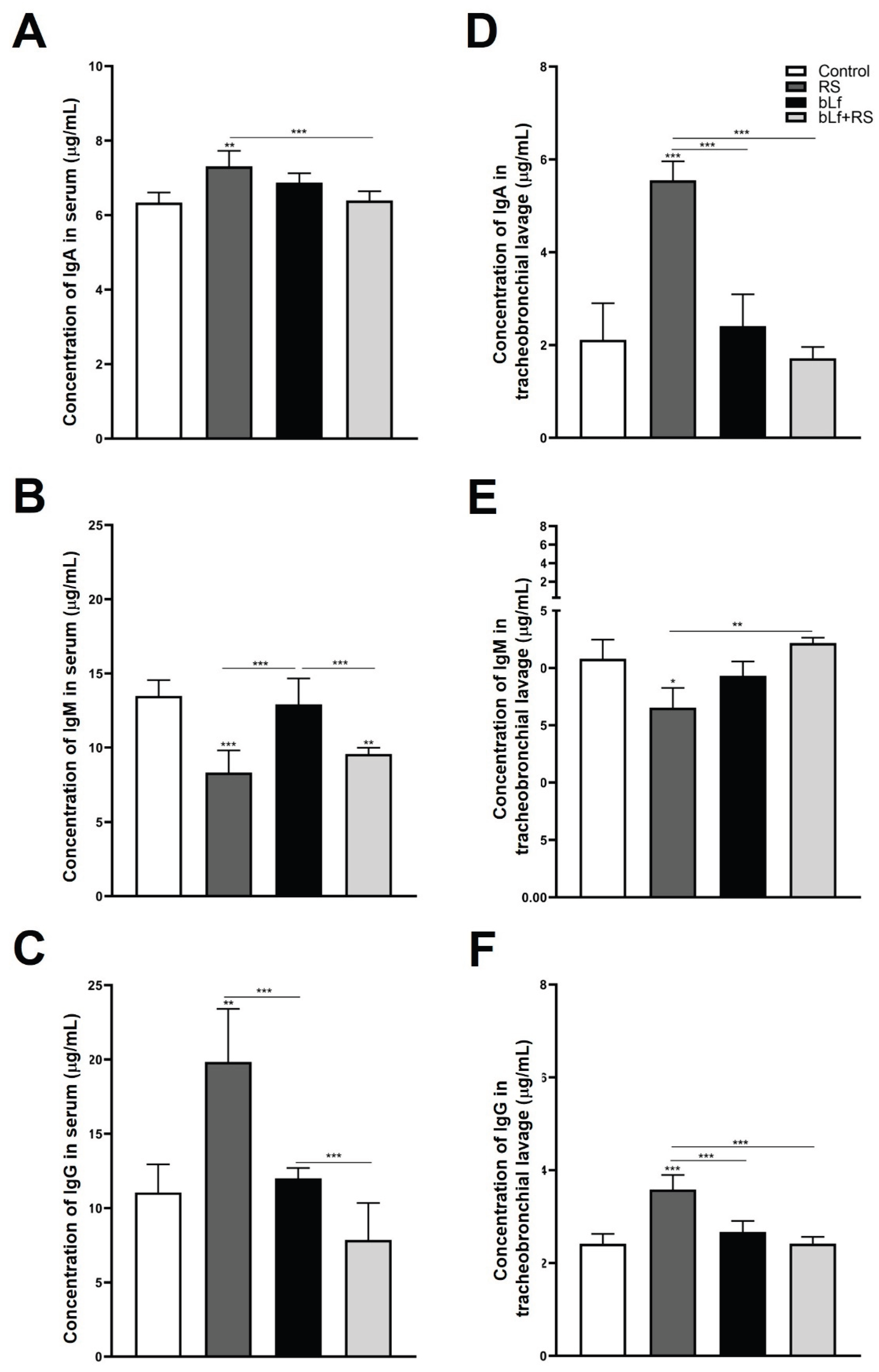

2.3. Bovine Lactoferrin Modulates the Effect of Chronic Stress in Immunoglobulin Concentrations

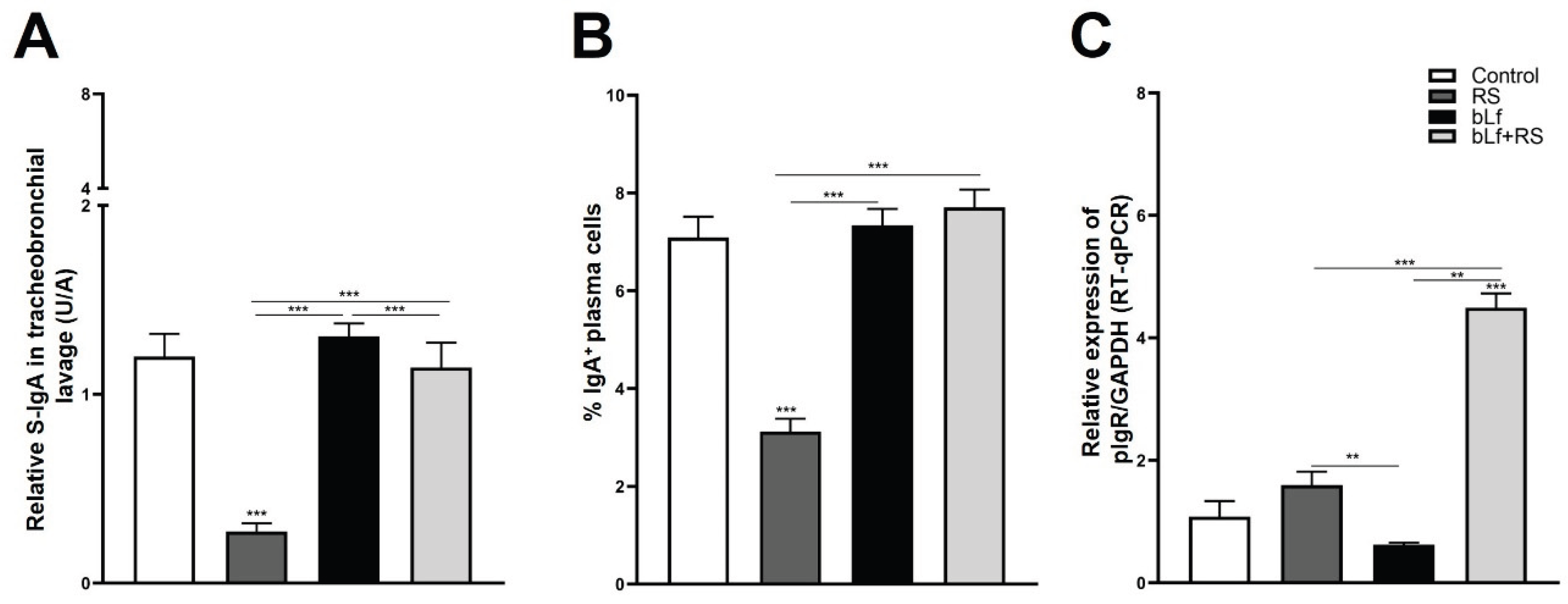

2.4. Bovine Lactoferrin Modulates Stress-Induced Diminished S-IgA Release in Tracheobronchial Lavage and Serum

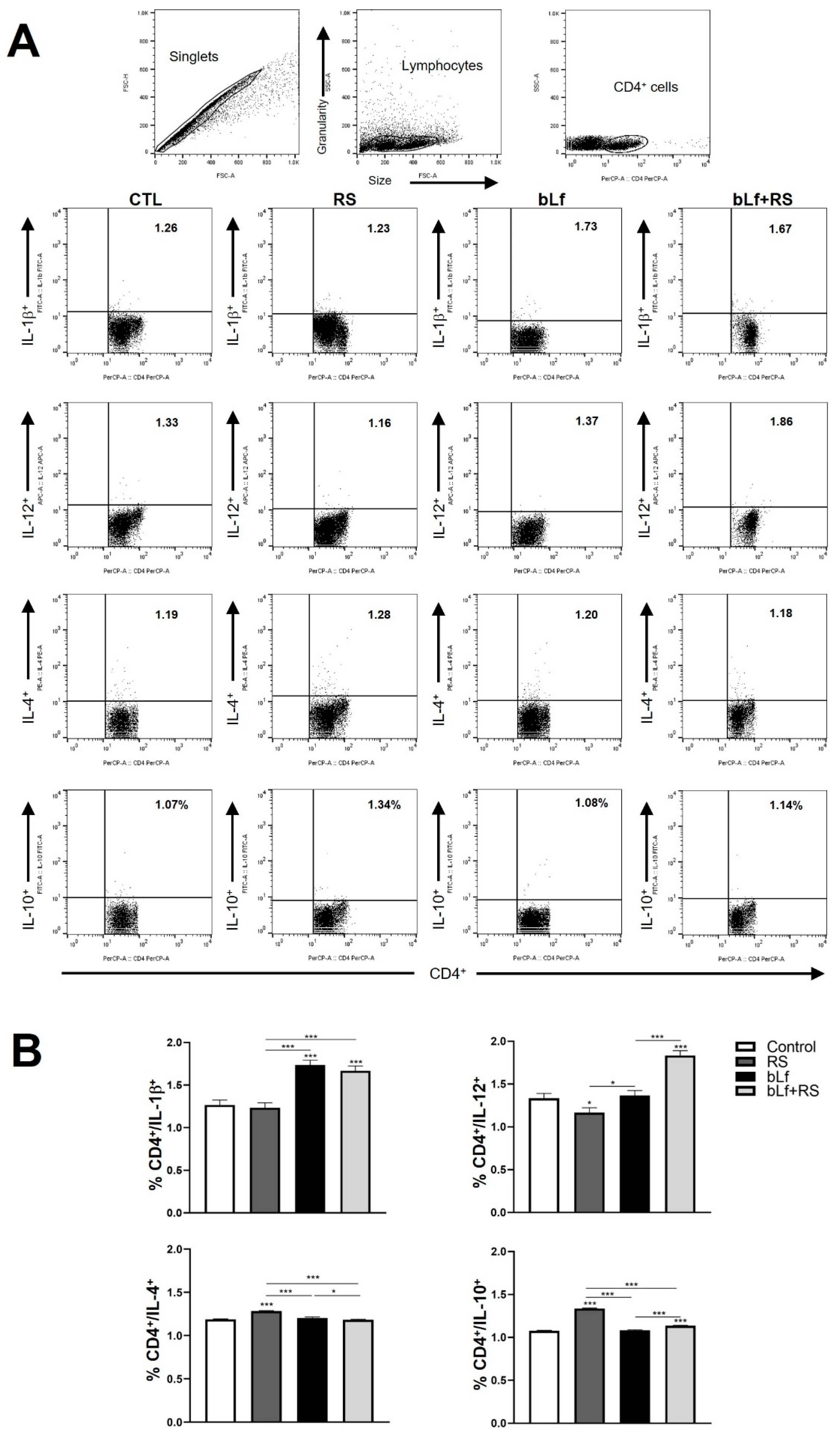

2.5. bLf Promotes Th1 Response and Decreases Th2 Established During Stress

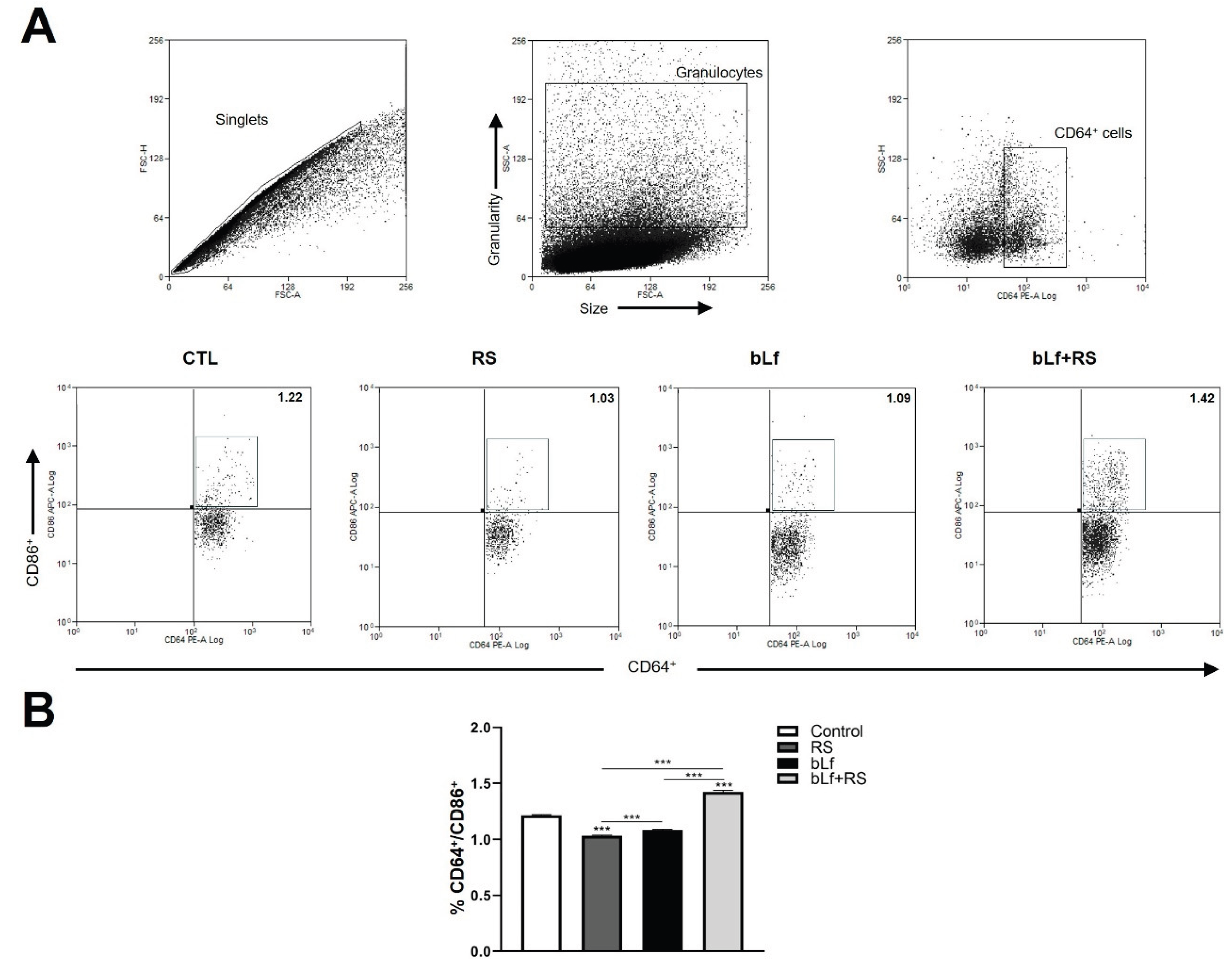

2.6. bLf Modulates CD64+/CD86+ Cell Populations Promoted by Stress

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Animals

4.2. Stress and bLf Administration Protocol

4.3. Mice Weight

4.4. Blood Collection

4.5. Corticosterone Assay

4.6. Tracheobronchial Lavage

4.7. Immunoglobulin Measurement

4.8. Lung Lymphocyte Cells Purification

4.9. Flow Cytometry Assay

4.10. Real-Time qPCR of pIgR

4.10.1. RNA Extraction

4.10.2. cDNA Synthesis

4.10.3. Quantitative Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction (qRT-PCR)

4.11. Statistical Analysis

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| bLf | Bovine lactoferrin |

| RS | Restraint Stress |

| TBL | Tracheobronchial lavages |

| S-IgA | Secretory Immunoglobulin A |

| APC | Antigen Presenting Cells |

| COPD | Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease |

| pIgR | Polymeric Immunoglobulin Receptor |

| mIgA | Monomeric ImmunoglobulinA |

| dIgA | Dimeric ImmunoglobulinA |

| SC | Secretory component |

| MTB | Mycobacterium tuberculosis |

References

- Dhabhar, F.S. Effects of Stress on Immune Function: The Good, the Bad, and the Beautiful. Immunol Res 2014, 58, 193–210. [CrossRef]

- Chrousos, G.P. The Hypothalamic–Pituitary–Adrenal Axis and Immune-Mediated Inflammation. New England Journal of Medicine 1995, 332, 1351–1363. [CrossRef]

- Dhabhar, F.S.; Malarkey, W.B.; Neri, E.; McEwen, B.S. Stress-Induced Redistribution of Immune Cells—From Barracks to Boulevards to Battlefields: A Tale of Three Hormones – Curt Richter Award Winner. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2012, 37, 1345–1368. [CrossRef]

- Vittwrakis, S.; Gaga, M.; Oikonomidou, E.; Samitas, K.; Xwrianopoulos, D. Immunological Mechanisms in the Lung. Pneumon 2007, 20, 274–278.

- Ardain, A.; Marakalala, M.J.; Leslie, A. Tissue-resident Innate Immunity in the Lung. Immunology 2020, 159, 245–256. [CrossRef]

- Agorastos, A.; Chrousos, G.P. The Neuroendocrinology of Stress: The Stress-Related Continuum of Chronic Disease Development. Mol Psychiatry 2022, 27, 502–513. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S. Psychological Stress and Susceptibility to Upper Respiratory Infections. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1995, 152, S53–S58. [CrossRef]

- Leick, E.A.; Reis, F.G.; Honorio-Neves, F.A.; Almeida-Reis, R.; Prado, C.M.; Martins, M.A.; Tibério, I.F.L.C. Effects of Repeated Stress on Distal Airway Inflammation, Remodeling and Mechanics in an Animal Model of Chronic Airway Inflammation. Neuroimmunomodulation 2012, 19, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Reis, F.G.; Marques, R.H.; Starling, C.M.; Almeida-Reis, R.; Vieira, R.P.; Cabido, C.T.; Silva, L.F.F.; Lanças, T.; Dolhnikoff, M.; Martins, M.A.; et al. Stress Amplifies Lung Tissue Mechanics, Inflammation and Oxidative Stress Induced by Chronic Inflammation. Exp Lung Res 2012, 38, 344–354. [CrossRef]

- Miyasaka, T.; Dobashi-Okuyama, K.; Takahashi, T.; Takayanagi, M.; Ohno, I. The Interplay between Neuroendocrine Activity and Psychological Stress-Induced Exacerbation of Allergic Asthma. Allergology International 2018, 67, 32–42. [CrossRef]

- Lee, L.; Yu, J. Sensory Nerves in Lung and Airways. In Comprehensive Physiology; Wiley, 2014; pp. 287–324.

- Shin, K.; Wakabayashi, H.; Yamauchi, K.; Teraguchi, S.; Tamura, Y.; Kurokawa, M.; Shiraki, K. Effects of Orally Administered Bovine Lactoferrin and Lactoperoxidase on Influenza Virus Infection in Mice. J Med Microbiol 2005, 54, 717–723. [CrossRef]

- Han, N.; Li, H.; Li, G.; Shen, Y.; Fei, M.; Nan, Y. Effect of Bovine Lactoferrin as a Novel Therapeutic Agent in a Rat Model of Sepsis-Induced Acute Lung Injury. AMB Express 2019, 9, 177. [CrossRef]

- Kell, D.B.; Heyden, E.L.; Pretorius, E. The Biology of Lactoferrin, an Iron-Binding Protein That Can Help Defend Against Viruses and Bacteria. Front Immunol 2020, 11. [CrossRef]

- Legrand, D. Overview of Lactoferrin as a Natural Immune Modulator. J Pediatr 2016, 173, S10–S15. [CrossRef]

- Masson, P.L.; Heremans, J.F. Lactoferrin in Milk from Different Species. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part B: Comparative Biochemistry 1971, 39, 119-IN13. [CrossRef]

- Kanwar, J.; Roy, K.; Patel, Y.; Zhou, S.-F.; Singh, M.; Singh, D.; Nasir, M.; Sehgal, R.; Sehgal, A.; Singh, R.; et al. Multifunctional Iron Bound Lactoferrin and Nanomedicinal Approaches to Enhance Its Bioactive Functions. Molecules 2015, 20, 9703–9731. [CrossRef]

- Drago-Serrano, M.E.; Flores-Romo, L.; Oliver-Aguillón, G.; Jarillo-Luna, R.A.; Reyna-Garfias, H.; Barbosa-Cabrera, E.; Campos-Rodríguez, R. La Lactoferrina Como Modulador de La Respuesta Inmunitaria. Bioquimia 2008, 33, 71–82.

- González-Chávez, S.A.; Arévalo-Gallegos, S.; Rascón-Cruz, Q. Lactoferrin: Structure, Function and Applications. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2009, 33, 301.e1-301.e8. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Franco D Actividad Antimicrobiana de La Lactoferrina: Mecanismos y Aplicaciones Clínicas Potenciales; Revista Latinoamericana de Microbiología, 2005; Vol. 47.

- Baveye, S.; Elass, E.; Mazurier, J.; Spik, G.; Legrand, D. Lactoferrin: A Multifunctional Glycoprotein Involved in the Modulation of the Inflammatory Process. cclm 1999, 37, 281–286. [CrossRef]

- Kruzel, M.L.; Zimecki, M.; Actor, J.K. Lactoferrin in a Context of Inflammation-Induced Pathology. Front Immunol 2017, 8. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Wen, J.; Chen, G. Role and Mechanism of Chronic Restraint Stress in Regulating Energy Metabolism and Reproductive Function Through Hypothalamic Kisspeptin Neurons. J Endocr Soc 2021, 5, A551–A552. [CrossRef]

- Harris, R.B.S.; Mitchell, T.D.; Simpson, J.; Redmann, S.M.; Youngblood, B.D.; Ryan, D.H. Weight Loss in Rats Exposed to Repeated Acute Restraint Stress Is Independent of Energy or Leptin Status. American Journal of Physiology-Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology 2002, 282, R77–R88. [CrossRef]

- Michel, C.; Duclos, M.; Cabanac, M.; Richard, D. Chronic Stress Reduces Body Fat Content in Both Obesity-Prone and Obesity-Resistant Strains of Mice. Horm Behav 2005, 48, 172–179. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Liu, Q.; Huang, G.; Wen, J.; Chen, G. Hypothalamic Kisspeptin Neurons Regulates Energy Metabolism and Reproduction Under Chronic Stress. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2022, 13. [CrossRef]

- López López, A. Chronic Unpredictable Mild Stress Progressively Disturbs Glucose Metabolism and Appetite Hormones In Rats. Acta Endocrinologica (Bucharest) 2018, 14, 16–23. [CrossRef]

- Safaeian, L.; Zabolian, H. Antioxidant Effects of Bovine Lactoferrin on Dexamethasone-Induced Hypertension in Rat. ISRN Pharmacol 2014, 2014, 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Ono, T.; Murakoshi, M.; Uchiyama, A. Anti-Obesity Effect of Lactoferrin; Subgroup Analysis Excluding Subjects with Obese and/or Hyper-LDL Cholesterolemia. Immunol Endocr Metab Agents Med Chem 2018, 18, 105–109. [CrossRef]

- Jańczuk-Grabowska, A.; Czernecki, T.; Brodziak, A. Gene–Diet Interactions: Viability of Lactoferrin-Fortified Yoghurt as an Element of Diet Therapy in Patients Predisposed to Overweight and Obesity. Foods 2023, 12, 2929. [CrossRef]

- Spencer, R.L.; Deak, T. A Users Guide to HPA Axis Research. Physiol Behav 2017, 178, 43–65. [CrossRef]

- Zefferino, R.; Di Gioia, S.; Conese, M. Molecular Links between Endocrine, Nervous and Immune System during Chronic Stress. Brain Behav 2021, 11. [CrossRef]

- Godínez-Victoria, M.; Cruz-Hernández, T.R.; Reyna-Garfias, H.; Barbosa-Cabrera, R.E.; Drago-Serrano, M.E.; Sánchez-Gómez, M.C.; Campos-Rodríguez, R. Modulation by Bovine Lactoferrin of Parameters Associated with the IgA Response in the Proximal and Distal Small Intestine of BALB/c Mice. Immunopharmacol Immunotoxicol 2017, 39, 66–73. [CrossRef]

- Guzmán-Mejía, F.; Vega-Bautista, A.; Molotla-Torres, D.E.; Aguirre-Garrido, J.F.; Drago-Serrano, M.E. Bovine Lactoferrin as a Modulator of Neuroendocrine Components of Stress. Curr Mol Pharmacol 2021, 14, 1037–1045. [CrossRef]

- Harada, E.; Itoh, Y.; Sitizyo, K.; Takeuchi, T.; Araki, Y.; Kitagawa, H. Characteristic Transport of Lactoferrin from the Intestinal Lumen into the Bile via the Blood in Piglets. Comp Biochem Physiol A Mol Integr Physiol 1999, 124, 321–327. [CrossRef]

- Talukder, Md.J.R.; Takeuchi, T.; Harada, E. Receptor-Mediated Transport of Lactoferrin into the Cerebrospinal Fluid via Plasma in Young Calves. Journal of Veterinary Medical Science 2003, 65, 957–964. [CrossRef]

- Kamemori, N.; Takeuchi, T.; Sugiyama, A.; Miyabayashi, M.; Kitagawa, H.; Shimizu, H.; Ando, K.; Harada, E. Trans-Endothelial and Trans-Epithelial Transfer of Lactoferrin into the Brain through BBB and BCSFB in Adult Rats. Journal of Veterinary Medical Science 2008, 70, 313–315. [CrossRef]

- Kamemori, N.; Takeuchi, T.; Hayashida, K.; Harada, E. Suppressive Effects of Milk-Derived Lactoferrin on Psychological Stress in Adult Rats. Brain Res 2004, 1029, 34–40. [CrossRef]

- Aleshina, G.M.; Yankelevich, I.A.; Zhakharova, E.T.; Kokryakov, V.N. Rossiiskii Fiziologicheskii Zhurnal Imeni I.M. Sechenova. 2016, 102, 846–851.

- Takeuchi, T.; Hayashida, K.; Inagaki, H.; Kuwahara, M.; Tsubone, H.; Harada, E. Opioid Mediated Suppressive Effect of Milk-Derived Lactoferrin on Distress Induced by Maternal Separation in Rat Pups. Brain Res 2003, 979, 216–224. [CrossRef]

- Maekawa, Y.; Sugiyama, A.; Takeuchi, T. Lactoferrin Ameliorates Corticosterone-Related Acute Stress and Hyperglycemia in Rats. Journal of Veterinary Medical Science 2017, 79, 412–417. [CrossRef]

- Peña-Juárez, Ma.C.; Campos-Rodríguez, R.; Godínez-Victoria, M.; Cruz-Hernández, T.R.; Reyna-Garfias, H.; Barbosa-Cabrera, R.E.; Drago-Serrano, M.E. Effect of Bovine Lactoferrin Treatment Followed by Acute Stress on the IgA-Response in Small Intestine of BALB/c Mice. Immunol Invest 2016, 45, 652–667. [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Hernández, T.; Gómez-Jiménez, D.; Campos-Rodríguez, R.; Godínez-Victoria, M.; Drago-Serrano, M. Analysis of the Intestinal IgA Response in Mice Exposed to Chronic Stress and Treated with Bovine Lactoferrin. Mol Med Rep 2020, 23, 126. [CrossRef]

- Campos-Rodríguez, R.; Godínez-Victoria, M.; Abarca-Rojano, E.; Pacheco-Yépez, J.; Reyna-Garfias, H.; Barbosa-Cabrera, R.E.; Drago-Serrano, M.E. Stress Modulates Intestinal Secretory Immunoglobulin A. Front Integr Neurosci 2013, 7. [CrossRef]

- Silberman, D. Acute and Chronic Stress Exert Opposing Effects on Antibody Responses Associated with Changes in Stress Hormone Regulation of T-Lymphocyte Reactivity. J Neuroimmunol 2003, 144, 53–60. [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, H.Y. Immunoglobulin G and Its Function in the Human Respiratory Tract. Mayo Clin Proc 1988, 63, 161–174. [CrossRef]

- Pilette, C. Mucosal Immunity in Asthma and Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: A Role for Immunoglobulin A? Proc Am Thorac Soc 2004, 1, 125–135. [CrossRef]

- Reyna-Garfias, H.; Miliar, A.; Jarillo-Luna, A.; Rivera-Aguilar, V.; Pacheco-Yepez, J.; Baeza, I.; Campos-Rodríguez, R. Repeated Restraint Stress Increases IgA Concentration in Rat Small Intestine. Brain Behav Immun 2010, 24, 110–118. [CrossRef]

- Jarillo-Luna, A.; Rivera-Aguilar, V.; Garfias, H.R.; Lara-Padilla, E.; Kormanovsky, A.; Campos-Rodríguez, R. Effect of Repeated Restraint Stress on the Levels of Intestinal IgA in Mice. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2007, 32, 681–692. [CrossRef]

- Arciniega-Martínez, I.M.; Campos-Rodríguez, R.; Drago-Serrano, M.E.; Sánchez-Torres, L.E.; Cruz-Hernández, T.R.; Reséndiz-Albor, A.A. Modulatory Effects of Oral Bovine Lactoferrin on the IgA Response at Inductor and Effector Sites of Distal Small Intestine from BALB/c Mice. Arch Immunol Ther Exp (Warsz) 2016, 64, 57–63. [CrossRef]

- Welsh, K.J.; Hwang, S.-A.; Boyd, S.; Kruzel, M.L.; Hunter, R.L.; Actor, J.K. Influence of Oral Lactoferrin on Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Induced Immunopathology. Tuberculosis 2011, 91, S105–S113. [CrossRef]

- Yamauchi, K.; Wakabayashi, H.; Shin, K.; Takase, M. Bovine Lactoferrin: Benefits and Mechanism of Action against Infections. Biochemistry and Cell Biology 2006, 84, 291–296. [CrossRef]

- Van Splunter, M.E. Immunomodulation by Raw Bovine Milk and Its Ingredients: Effects in Nutritional Intervention, Oral Vaccination and Trained Immunity, Wageningen University, 2018.

- Corthésy, B. Multi-Faceted Functions of Secretory IgA at Mucosal Surfaces. Front Immunol 2013, 4. [CrossRef]

- de Fays, C.; Carlier, F.M.; Gohy, S.; Pilette, C. Secretory Immunoglobulin A Immunity in Chronic Obstructive Respiratory Diseases. Cells 2022, 11, 1324. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, J.; Wu, Y.; Xu, Y.; Zheng, J. SIgA in Various Pulmonary Diseases. Eur J Med Res 2023, 28, 299. [CrossRef]

- Johansen, F.E.; Kaetzel, C.S. Regulation of the Polymeric Immunoglobulin Receptor and IgA Transport: New Advances in Environmental Factors That Stimulate PIgR Expression and Its Role in Mucosal Immunity. Mucosal Immunol 2011, 4, 598–602. [CrossRef]

- Jang, Y.S.; Seo, G.-Y.; Lee, J.-M.; Seo, H.-Y.; Han, H.-J.; Kim, S.-J.; Jin, B.-R.; Kim, H.-J.; Park, S.-R.; Rhee, K.-J.; et al. Lactoferrin Causes IgA and IgG2b Isotype Switching through Betaglycan Binding and Activation of Canonical TGF-β Signaling. Mucosal Immunol 2015, 8, 906–917. [CrossRef]

- Ladjemi, M.Z.; Gras, D.; Dupasquier, S.; Detry, B.; Lecocq, M.; Garulli, C.; Fregimilicka, C.; Bouzin, C.; Gohy, S.; Chanez, P.; et al. Bronchial Epithelial IgA Secretion Is Impaired in Asthma. Role of IL-4/IL-13. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2018, 197, 1396–1409. [CrossRef]

- Gohy, S.T.; Detry, B.R.; Lecocq, M.; Bouzin, C.; Weynand, B.A.; Amatngalim, G.D.; Sibille, Y.M.; Pilette, C. Polymeric Immunoglobulin Receptor Down-Regulation in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Persistence in the Cultured Epithelium and Role of Transforming Growth Factor-β. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2014, 190, 509–521. [CrossRef]

- Carlier, F.M.; Detry, B.; Lecocq, M.; Collin, A.M.; Planté-Bordeneuve, T.; Gérard, L.; Verleden, S.E.; Delos, M.; Rondelet, B.; Janssens, W.; et al. The Memory of Airway Epithelium Damage in Smokers and COPD Patients. Life Sci Alliance 2024, 7, e202302341. [CrossRef]

- Cameron, L.; Palikhe, N.S.; Laratta, C.; Vliagoftis, H. Elevated Circulating Th2 Cells in Women With Asthma and Psychological Morbidity: A New Asthma Endotype? Clin Ther 2020, 42, 1015–1031. [CrossRef]

- Ouchi, R.; Kawano, T.; Yoshida, H.; Ishii, M.; Miyasaka, T.; Ohkawara, Y.; Takayanagi, M.; Takahashi, T.; Ohno, I. Maternal Separation as Early-Life Stress Causes Enhanced Allergic Airway Responses by Inhibiting Respiratory Tolerance in Mice. Tohoku J Exp Med 2018, 246, 155–165. [CrossRef]

- Rinshō Byōri Abstracts of the 57th Meeting of the Japanese Society of Clinical Pathology 1953, 58.

- Dragunas, G.; De Oliveira, M.A.; Tavares-De-Lima, W.; Gosens, R.; Munhoz, C.D. Chronic Unpredictable Stress Exacerbates Allergic Airway Inflammation in Mice. In Proceedings of the Airway pharmacology and treatment; European Respiratory Society, March 10 2022; p. 28.

- Okuyama, K.; Ohwada, K.; Sakurada, S.; Sato, N.; Sora, I.; Tamura, G.; Takayanagi, M.; Ohno, I. The Distinctive Effects of Acute and Chronic Psychological Stress on Airway Inflammation in a Murine Model of Allergic Asthma. Allergology International 2007, 56, 29–35. [CrossRef]

- Okuyama, K.; Dobashi, K.; Miyasaka, T.; Yamazaki, N.; Kikuchi, T.; Sora, I.; Takayanagi, M.; Kita, H.; Ohno, I. The Involvement of Glucocorticoids in Psychological Stress-Induced Exacerbations of Experimental Allergic Asthma. Int Arch Allergy Immunol 2014, 163, 297–306. [CrossRef]

- Sato, S.; Kawano, T.; Ike, E.; Takahashi, K.; Sakurai, J.; Miyasaka, T.; Miyauchi, Y.; Ishizawa, F.; Takayanagi, M.; Takahashi, T. IL-1β Derived Th17 Immune Responses Are a Critical Factor for Neutrophilic-Eosinophilic Airway Inflammation on Psychological Stress-Induced Immune Tolerance Breakdown in Mice. Int Arch Allergy Immunol 2023, 184, 797–807. [CrossRef]

- Kawano, T.; Ouchi, R.; Ishigaki, T.; Masuda, C.; Miyasaka, T.; Ohkawara, Y.; Ohta, N.; Takayanagi, M.; Takahashi, T.; Ohno, I. Increased Susceptibility to Allergic Asthma with the Impairment of Respiratory Tolerance Caused by Psychological Stress. Int Arch Allergy Immunol 2018, 177, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Dobbs, C.M.; Feng, N.; Beck, F.M.; Sheridan, J.F. Neuroendocrine Regulation of Cytokine Production during Experimental Influenza Viral Infection: Effects of Restraint Stress-Induced Elevation in Endogenous Corticosterone. The Journal of Immunology 1996, 157.

- Lafuse, W.P.; Wu, Q.; Kumar, N.; Saljoughian, N.; Sunkum, S.; Ahumada, O.S.; Turner, J.; Rajaram, M.V.S. Psychological Stress Creates an Immune Suppressive Environment in the Lung That Increases Susceptibility of Aged Mice to Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Infection. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2022, 12. [CrossRef]

- Drago-Serrano, M.E.; Campos-Rodríguez, R.; Carrero, J.C.; Delagarza, M. Lactoferrin: Balancing Ups and Downs of Inflammation Due to Microbial Infections. Int J Mol Sci 2017, 18.

- Artym, J.; Kocięba, M.; Zaczyńska, E.; Adamik, B.; Kübler, A.; Zimecki, M.; Kruzel, M. Immunomodulatory Properties of Human Recombinant Lactoferrin in Mice: Implications for Therapeutic Use in Humans. Advances in Clinical and Experimental Medicine 2018, 27, 391–399. [CrossRef]

- Actor, J.K. Lactoferrin: A Modulator for Immunity against Tuberculosis Related Granulomatous Pathology. Mediators Inflamm 2015, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Zimecki, M.; Actor, J.K.; Kruzel, M.L. The Potential for Lactoferrin to Reduce SARS-CoV-2 Induced Cytokine Storm. Int Immunopharmacol 2021, 95, 107571. [CrossRef]

- Bain, C.C.; MacDonald, A.S. The Impact of the Lung Environment on Macrophage Development, Activation and Function: Diversity in the Face of Adversity. Mucosal Immunol 2022, 15, 223–234. [CrossRef]

- de Heer, H.J.; Hammad, H.; Soullié, T.; Hijdra, D.; Vos, N.; Willart, M.A.M.; Hoogsteden, H.C.; Lambrecht, B.N. Essential Role of Lung Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cells in Preventing Asthmatic Reactions to Harmless Inhaled Antigen. J Exp Med 2004, 200, 89–98. [CrossRef]

- DeKruyff, R.H.; Fang, Y.; Umetsu, D.T. Corticosteroids Enhance the Capacity of Macrophages to Induce Th2 Cytokine Synthesis in CD4+ Lymphocytes by Inhibiting IL-12 Production. J Immunol 1998, 160, 2231–2237.

- Oros-Pantoja, R.; Jarillo-Luna, A.; Rivera-Aguilar, V.; Sánchez-Torres, L.E.; Godinez-Victoria, M.; Campos-Rodríguez, R. Effects of Restraint Stress on NALT Structure and Nasal IgA Levels. Immunol Lett 2011, 135, 78–87. [CrossRef]

- Drago-Serrano, M.E.; Rivera-Aguilar, V.; Reséndiz-Albor, A.A.; Campos-Rodríguez, R. Lactoferrin Increases Both Resistance to Salmonella Typhimurium Infection and the Production of Antibodies in Mice. Immunol Lett 2010, 134, 35–46. [CrossRef]

- Van Hoecke, L.; Job, E.R.; Saelens, X.; Roose, K. Bronchoalveolar Lavage of Murine Lungs to Analyze Inflammatory Cell Infiltration. Journal of Visualized Experiments 2017. [CrossRef]

- Reséndiz-Albor, A.A.; Reina-Garfias, H.; Rojas-Hernández, S.; Jarillo-Luna, A.; Rivera-Aguilar, V.; Miliar-García, A.; Campos-Rodríguez, R. Regionalization of PIgR Expression in the Mucosa of Mouse Small Intestine. Immunol Lett 2010, 128, 59–67. [CrossRef]

- Arciniega-Martínez, I.; Reséndiz Albor, A.; Cárdenas Jaramillo, L.; Gutiérrez-Meza, J.; Falfán-Valencia, R.; Arroyo, B.; Yépez-Ortega, M.; Pacheco-yépez, J.; Abarca-rojano, E. CD4+/IL-4+ Lymphocytes of the Lamina Propria and Substance P Promote Colonic Protection during Acute Stress. Mol Med Rep 2021, 25, 63. [CrossRef]

- Velásquez-Torres, M.; Trujillo-Ferrara, J.G.; Godínez-Victoria, M.; Jarillo-Luna, R.A.; Tsutsumi, V.; Sánchez-Monroy, V.; Posadas-Mondragón, A.; Cuevas-Hernández, R.I.; Santiago-Cruz, J.A.; Pacheco-Yépez, J. Riluzole, a Derivative of Benzothiazole as a Potential Anti-Amoebic Agent against Entamoeba Histolytica. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 896. [CrossRef]

| Primer | Forward 5′-3′ | Reverse 3′-5′ |

|---|---|---|

| pIgR | TCAATCAGCAGCTACAGGACAGA | GTGCACTCCGTGGTAGTCA |

| GAPDH | GATGCCCCCATGTTTGTGAT | GGTCATGAGCCCTTCCACAAT |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).