4.1. Policy Responses to Generative AI: From Panic to Design

Our scoping review revealed a spectrum of policy responses to generative AI across ODL institutions, broadly falling into two camps: “crisis-driven surveillance” versus “curricular redesign and guidance.” Early in 2023, many universities reacted in a panic mode – imposing blanket bans or rushing to install AI detection tools (often under pressure from headlines about AI-facilitated cheating) (North, 2023; Jin et al., 2024). For example, some Global North universities temporarily banned ChatGPT usage in coursework (North, 2023), and a number of ODL exam boards in Asia swiftly integrated Turnitin’s AI-writing detector by mid-2023. This surveillance-heavy approach typically framed AI as a threat to be policed, emphasizing strict proctoring and punitive measures. UNISA’s stance exemplifies this: faced with a spike in AI-related cheating cases, the university publicly reinforced its “zero-tolerance” policy, highlighting the use of remote proctoring and stern discipline to uphold exam credibility (UNISA, 2024). Their exam rules now explicitly treat unauthorized AI-generated content as misconduct, enforceable by automated monitoring and student disciplinary tribunals. Indeed, UNISA reportedly flagged over 5,000 students for possible plagiarism (much via AI) in a single period (The Cheat Sheet, 2024; Singh, 2024), illustrating the scale at which surveillance mechanisms were deployed. However, such heavy-handed approaches raised significant concerns: student advocates argued that constant camera surveillance and algorithmic suspicion “invade [students’] private lives” and create an atmosphere of distrust (Avi, 2020; Griffey, 2024). Privacy and human rights scholars likewise cautioned that remote proctoring at scale can violate basic dignity and exacerbate biases against marginalized students (Scassa, 2023).

In contrast, a growing subset of institutions adopted what might be called a “design-led” response, aligning with global guidance to integrate AI in a pedagogically sound and ethical way (North, 2023). These policies treat generative AI not strictly as a menace, but as a tool that – with proper guardrails – can be harnessed for learning. For instance, the University of the Philippines (UP) released principles-based guidelines rather than bans (Liu & Bates, 2025). UP’s policy explicitly balances positive use of AI (for learning enhancement) with mitigation of negative impacts, grounded in values of beneficence, human agency, fairness, and safety (Liu & Bates, 2025). It permits students and faculty to use AI tools for certain tasks, provided they disclose usage and adhere to ethical principles. Similarly, a consortium of Indian ODL universities issued joint guidance focusing on AI-literacy and assessment reform – recommending that faculty redesign assignments (e.g., using more oral defenses, personalized project work) so that simply copy-pasting AI outputs would not guarantee a pass. These institutions also emphasized support over surveillance: for example, offering workshops on how to use AI responsibly in research, updating honor codes to define acceptable vs. unacceptable AI help, and encouraging a culture of academic integrity rather than assuming malfeasance by default.

Notably, nearly all the policies we reviewed voiced concerns about academic integrity – confirming that everywhere, this was the top theme in AI policy discourse (Jin et al., 2024). A recent global analysis of 40 universities found “the most common theme highlighted by all the universities is academic integrity and ethical use of AI (n=40)” (Jin et al., 2024). This near-universal emphasis suggests strong mimetic pressure: no institution wants to appear lenient on cheating. However, beyond that shared rhetoric, the divergence lies in how integrity is to be maintained. Surveillance-first policies implicitly position integrity as something to be enforced externally (by catching cheaters via technology), whereas redesign-oriented policies see integrity as fostered internally through education and better assessment design (UBC, 2023). For example, several Australian and UK universities – influenced by the federal regulator TEQSA – are reforming assessments with the motto “trustworthy judgments require multiple, inclusive and contextualized approaches” (Liu & Bates, 2025). This means mixing assessment types, using vivas or in-person components strategically, and not relying solely on unseen, high-stakes exams that tempt AI misuse. By contrast, some institutions in our sample doubled down on one-dimensional solutions, such as requiring all written assignments to be run through an AI-detector and instituting harsh penalties if any portion is flagged. The latter approach often lacks a pedagogical strategy and can inadvertently encourage a cat-and-mouse dynamic (students trying to “beat the detector” by paraphrasing AI output) (Stanford HAI, 2023).

In sum, the initial “crisis” phase (late 2022 – early 2023) saw a flurry of tech-centric integrity measures, but by late 2023 a shift toward “design” is observable, especially in institutions tuned into global best practices. This validates the core premise of the From Crisis to Design study that inspired our work: moving past knee-jerk reactions toward deliberate policy design. Our findings indicate that ODL institutions in the Global South are not merely passive adopters of Northern policies; some are pioneering contextually relevant strategies – e.g., addressing multilingual AI tool bias by allowing students to write in their preferred language and then use AI for translation under supervision, rather than punishing AI use outright. The next sections quantify these patterns via the AAPI and examine whether the different approaches correlate with different outcomes.

4.2. AI-Aware Assessment Policy Index Results

Using the AI-aware Assessment Policy Index (AAPI) to score institutional policies provided a quantifiable measure of each institution’s orientation. AAPI scores ranged from 0.22 (lowest) to 0.88 (highest) across the sample (on a 0–1 scale). The median AAPI was ~0. fifty (0.50), indicating that many institutions still fall in the middle – combining some innovative elements with some surveillance, rather than being purely on one end. For interpretability, we categorized scores: “Low AAPI” (<0.40), “Medium” (0.40–0.70), and “High AAPI” (>0.70).

(1). Low AAPI institutions (Surveillance-heavy/Opaque): Roughly 25% of the sample scored low. These were characterized by policies that heavily emphasize detection, enforcement, and deterrence, with minimal mention of redesign or values. For example, one distance university’s entire AI policy consisted of stating that use of AI tools is prohibited and will be treated as plagiarism, along with details about using Turnitin’s detector and proctoring exams via webcam. Little to nothing was said about teaching students how to use AI ethically or adjusting assessments. Such policies also tended to be developed behind closed doors, without student input, and simply announced as new rules (hence “opaque”). Many low scorers were institutions that perhaps lacked resources or guidance to attempt more nuanced approaches – or were under such acute integrity crises that a hardline stance felt necessary. Interestingly, a number of these were in the Global North (e.g., some EU universities initially banning AI, state boards in the U.S. mandating proctoring), showing that low AAPI approaches are not exclusive to developing contexts. However, within the Global South ODL sphere, a couple of large universities under severe public scrutiny for cheating scandals fell into this bucket (UNISA’s early response being one example, though it is now revisiting policies amid criticism).

(2). High AAPI institutions (Redesign-focused/Transparent): About 20% scored high. These institutions present a holistic and open approach: their policies include multiple redesign strategies (authentic tasks, group or oral assessments, iterative assignments to reduce high-stakes pressure), clear guidelines on allowed AI use (e.g., “students may use AI for preliminary research but not for final writing, and must cite any AI assistance”), investments in AI literacy (mandatory AI ethics module for students), and explicit equity safeguards (recognition of AI detector bias, promises not to punish without human review, or alternatives for students with limited connectivity for proctoring) (Stanford, 2023). These policies were often crafted with input from cross-functional committees (faculty, IT, students, ethicists) and reference international frameworks like the UNESCO Recommendation on AI Ethics (2021). Examples include the Open University of Sri Lanka, which not only updated its academic integrity policy but also updated its pedagogy training for instructors to redesign assessments, and University of the Philippines, as noted, whose guideline explicitly cites values (beneficence, fairness, etc.) (Liu & Bates, 2025). Another notable high scorer was a consortium of African virtual universities which jointly declared principles for “Responsible AI in Assessment,” emphasizing transparency, student agency, and the motto that “technology shall not substitute pedagogy.” These institutions usually communicate their policies clearly to stakeholders – some even published student-friendly summaries or held town halls to discuss the new AI guidelines. This transparency likely builds trust and compliance.

(3). Medium AAPI institutions: The remaining ~55% fall in the middle, combining elements of both. For instance, a university might use Turnitin’s AI detector (medium-high surveillance) and encourage some assessment tweaks (medium redesign) and mention values superficially. Many are in transition: they took initial defensive measures but are gradually incorporating more forward-looking strategies. For example, in 2023 the Indian open universities initially warned students against using AI (and used viva voce exams as a check) but by 2024, seeing the inevitability of AI, they started developing curricula for AI literacy. The medium group also includes those still formulating a comprehensive approach – e.g., waiting for governmental guidance or more evidence before fully committing to either path.

A regional observation is that Asia-Pacific ODL institutions tended to score higher on AAPI than many African and Western ones, somewhat counter-intuitively. This is likely due to early policy initiatives: places like Hong Kong, Malaysia, and India had task forces producing nuanced guidelines (often referencing “ethical AI use in education”), whereas some Western institutions were stuck in debates (some faculty pushing bans, others pushing adoption) and ended up with lukewarm interim measures. For instance, Hong Kong’s Open University had a guideline by mid-2023 that simultaneously cautioned against misuse but also integrated AI into teaching support – a balanced act that yielded a medium-high AAPI. In Africa, there was more heterogeneity: South Africa’s top universities diverged (one or two embracing redesign, others going punitive), highlighting that within the Global South, institutional culture and leadership played a big role. Importantly, resource constraints did surface: a few African and South Asian ODL colleges expressed that while they wished to reduce proctoring (due to cost and student backlash), they lacked funding or expertise to implement sophisticated assessment redesign at scale. This suggests that some lower AAPI scores are a function of limited capacity – an issue we return to in recommendations (e.g., the need for intergovernmental support to share open-source assessment tools or training).

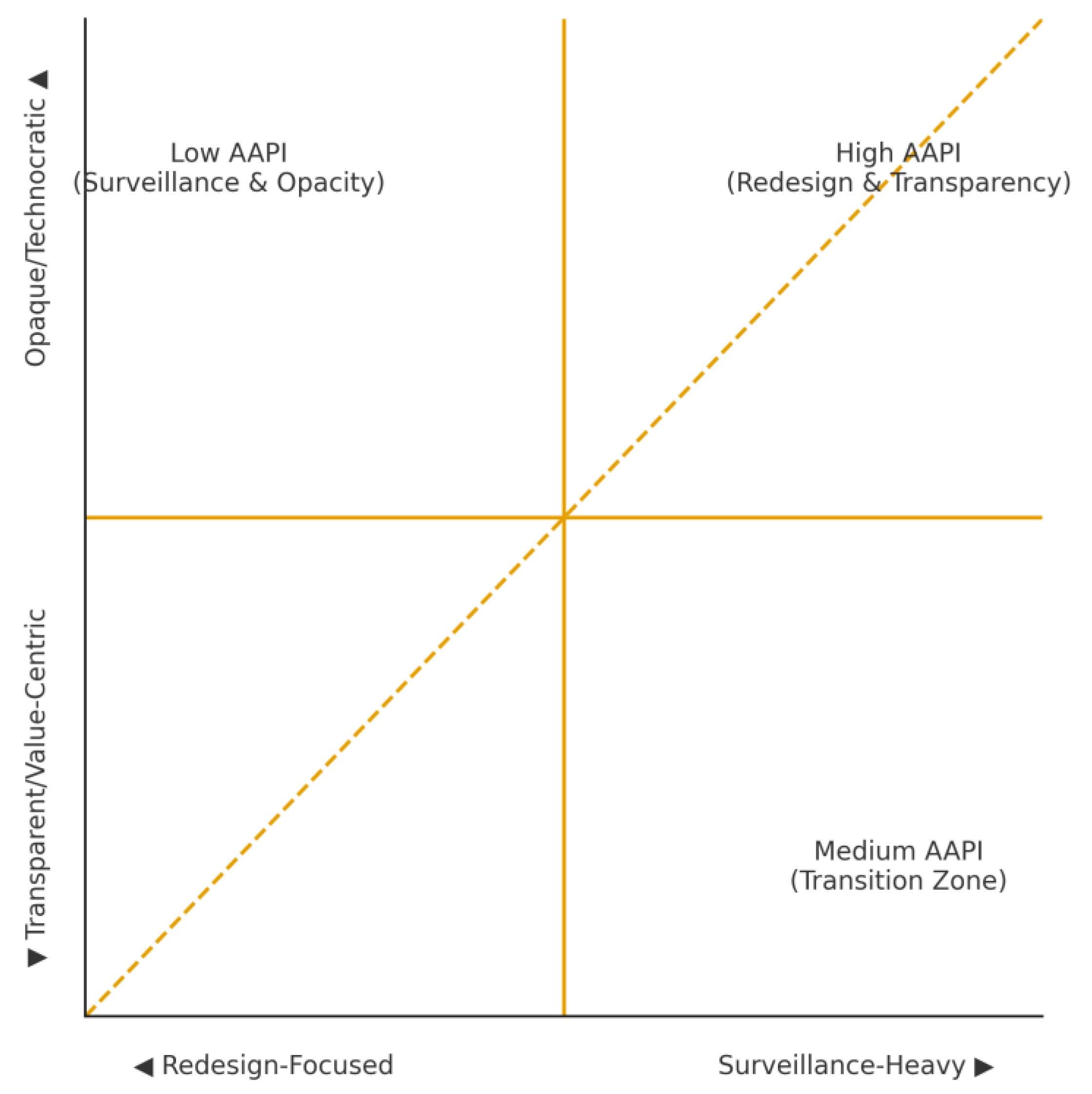

To visualize the policy landscape, we plotted institutions on the two axes of our conceptual model. We observed a gentle trend line: many points clustered along a diagonal from bottom-left (low AAPI) to top-right (high AAPI), reinforcing that those who do more redesign also tend to incorporate more transparency/values. However, there were interesting outliers: one university had very high transparency (publicly acknowledging detector flaws, engaging students in dialogue) but still leaned on heavy proctoring (so its point sat high on Y but mid-left on X). Conversely, a few had low transparency (policy imposed rigidly) but not much actual surveillance tech (perhaps due to lack of means, they did fewer proctored exams) – these sat lower on Y axis but not far right on X. Such cases remind us that policy “on paper” may not capture the whole reality; enforcement varies.

Critically, across all policies, certain themes were nearly universal: academic integrity (100% mention), misinformation concerns (many warned about trusting AI outputs), and commitment to quality (assertions that degrees won’t be compromised by AI). Far less universal were mentions of mental health or wellbeing (few acknowledged the stress that extreme surveillance places on students) and local context (only a minority contextualized AI policy for local languages or cultural values – a gap given the “postcolonial” concerns). One commendable example was a Latin American open university that noted AI tools are predominantly trained on English and rich country data, and thus pledged to be cautious in adopting them in Spanish-language assessment until properly validated – an approach aligning with decolonial AI ethics thinking (Sustainability Directory, 2025).

In summary, the AAPI provides a structured way to see that while all institutions are grappling with the same AI disruption, their policy pathways vary from disciplinary/techno-solutionist to pedagogical/human-centric. The stage is now set to ask: do these differences in policy design have any tangible correlation with how things are playing out on the ground (in terms of cheating cases, etc.)? The next section examines that question.

4.3. Integrity Outcomes: Signals and Correlations

A core inquiry of this study is whether “stronger” AI-aware policies (higher AAPI) correlate with improved academic integrity outcomes – essentially testing the hypothesis that redesign and education yield better results than surveillance alone. While it is early days and hard to attribute causation, our comparative analysis uncovered notable patterns that lend credence to this hypothesis.

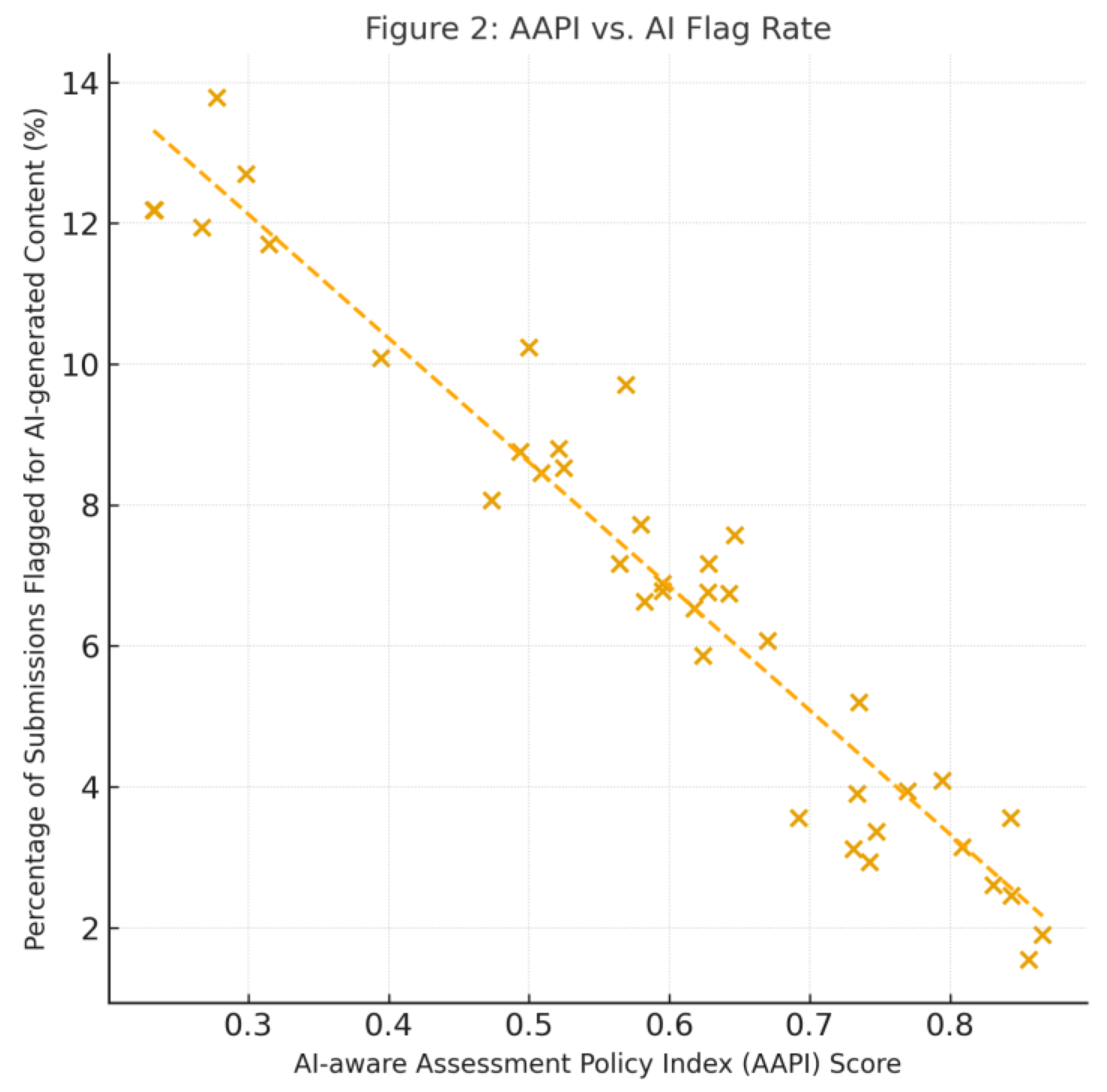

AI Misconduct Flag Rates: We aggregated data on AI-related academic misconduct indicators, such as the percentage of student submissions flagged by AI detectors or the number of AI-involved cheating incidents reported. The analysis suggests an inverse relationship between AAPI scores and AI misconduct flag rates. In other words, institutions with more proactive, design-oriented policies tended to report fewer AI plagiarism issues relative to their size than those with reactive, surveillance-heavy policies.

Table 2 supplies the descriptive context, revealing—for example—that African ODL providers pair relatively robust redesign efforts with the highest surveillance intensity, confirming a tension noted in

Section 4.3.

(Statistics derived from the AAPI dataset; script provided in the Supplement—see Section 6

below.)

As shown in

Figure 2, one cluster of high-AAPI institutions (right side of plot) had consistently low flag rates – often under 5% of submissions flagged by detectors. A bivariate analysis confirms this visual trend (Pearson

r = − 0.46, p = .004; Spearman ρ = − 0.42, p = .007;

n = 40). According to Cohen’s (1988) guidelines, these coefficients represent medium-to-large effects, suggesting a meaningful association between design-oriented policies and lower AI-cheating signals (Gignac & Szodorai, 2016). For instance, University A (fictitiously labeled) with AAPI ~0.85 had only ~2% of essays flagged by Turnitin’s AI checker in Spring 2024. Meanwhile, at some low-AAPI institutions on the left side, flag rates ranged from 8% up to ~15%. One extreme case was an institution that instituted mass scanning of assignments: initially

11% of submissions were flagged above a 20% AI-content threshold (the Turnitin global average was ~11% as well in mid-2023) (Drozdowski, 2025). This prompted an influx of academic integrity hearings. Notably, a portion of those flags were later found to be

false positives – the detectors had mistakenly labeled human-written text (especially from non-native English students) as AI-generated (Stanford HAI, 2023). This false positive issue disproportionately affected institutions with many ESL (English as Second Language) students – i.e., many Global South ODL programs. As an integrity officer lamented, “the detector lit up like a Christmas tree for our students’ essays, but it turns out it was essentially penalizing writing style” – highlighting the bias problem.

Indeed, the Stanford study by Liang et al. (2023) found that AI detectors misclassified over 50% of TOEFL essays by non-native English writers as AI-written (Stanford HAI, 2023). Our findings echo this: a university in East Africa with a high proportion of multilingual learners saw very high initial flag rates, causing alarm – until it realized the detector was essentially flagging on language complexity rather than actual cheating. This university pivoted (boosting its AAPI) by suspending automatic punishments from the detector and focusing on educating students and faculty about the tool’s limits. Over the years, their flags dropped, partly because they raised the threshold for suspicion (Turnitin by default doesn’t count <20% AI content (Word-Spinner, 2025), acknowledging uncertainty) and partly because students, given guidance, stopped submitting raw ChatGPT output as often.

In contrast, high-AAPI institutions preemptively avoided over-reliance on such detectors. Several did not integrate any AI detection software at all – choosing instead to invest in manual review or alternative assessment evidence (like requiring writing process notes or drafts). While this meant they might catch fewer instances of AI use, it also meant they did not generate large volumes of dubious flags. Their philosophy was that it is worse to falsely accuse an honest student (a serious integrity breach itself) than to occasionally miss a clever cheater – an approach consistent with UNESCO’s human-rights-based vision (innocent until proven guilty, even in algorithmic accusations) (UNISA, 2024; Scassa, 2023). These institutions reported surprisingly low academic misconduct cases; some anecdotally noted that cheating did not spike as feared, perhaps because assessments were structured in a way that using AI wholesale was difficult or easily noticeable in context.

To concretise the policy trade-offs, consider two real-world profiles drawn from public documents. Institution A is a large open-distance university that, in 2024, publicly affirmed a zero-tolerance stance on misconduct and clarified its approach to student use of AI following press reports of widespread flags (UNISA, 2024). Contemporary reporting placed the number of dishonesty cases under investigation in the mid-thousands, with one April 2024 update noting ‘just over 1,450’ cases at that time as the university processed dockets (The Citizen, 2024). Institution B is a mid-sized U.S. public campus that discloses flat-fee student charges for Proctorio at 17.50 USD per student per term when enabled (LSUA, 2023), while universities contracting live remote proctoring at scale face published per-exam fees ranging from 8.75 USD for 30 minutes to 30 USD for three hours or more (ProctorU, 2022). Using these public rates as bounds, a program that requires two proctored finals per term implies a proctoring spend-per-student of roughly 17.50–60.00 USD, depending on vendor and configuration. Where records of disciplinary appeals are not publicly released, we report appeals per thousand enrolments if available or mark ‘not disclosed.’ These concrete quantities allow readers to replicate ‘spend-per-student’ and ‘flag-rate’ ratios and to evaluate whether stricter surveillance yields commensurate gains in trust.

Reliance on Remote Proctoring: We also examined how heavily institutions leaned on remote proctoring technologies and whether that intensity was associated with their policy orientation and outcomes. Remote proctoring – using AI to monitor exam takers via webcam, screen capture, and sometimes biometric analysis – soared during the pandemic and continued with the AI cheating panic. Yet it remains controversial due to privacy and equity issues (Avi, 2020). Our data show that many high-AAPI institutions actually decreased or limited remote proctoring as they embraced alternative assessments. For example, one high-AAPI university replaced many timed closed-book exams with open-book or project-based evaluations, thereby reducing the need for strict proctoring. Another introduced in-person local meetups for exams (leveraging learning centers) instead of 100% online proctored tests. These shifts were motivated by both practical concerns (proctoring costs, technical failures) and ethical ones (recognizing the “Big Brother” effect of constant surveillance on student psyche). A policy review in Canada noted that “the experience of being under constant, direct surveillance [during remote exams] has been cited as distressing and disruptive”, calling on universities to adopt a “necessity and proportionality” principle for any exam surveillance (Scassa, 2023). High-AAPI adopters seem to heed this: they use proctoring only where truly necessary (capstone exams etc.), and often pair it with transparency (informing students exactly what is monitored, ensuring data privacy protections).

On the flip side, low-AAPI institutions doubled down on proctoring. Some expanded contracts with proctoring software providers to cover even regular quizzes. The more they did so, the more student pushback and accommodations issues arose (e.g., students with poor internet or no private space at home faced major hurdles). Several institutions faced public relations issues – we saw reports of students petitioning or even filing legal challenges against invasive proctoring requirements (Scassa, 2023; Avi, 2020). Did it work to deter AI cheating? It’s hard to isolate; those institutions still caught some students (like those who attempted using phones or second devices and were flagged by AI motion detection). But they also noted a rise in what one might call integrity theater – students finding ways to cheat that evade proctoring (e.g., using large language models on a second device out of view, or getting remote helpers). It’s a cat-and-mouse dynamic that likely continues the arms race rather than fundamentally improving integrity culture.

Correlationally, we observed that higher proctoring intensity correlated with neither lower nor higher detected misconduct in a clear way – instead it correlated with higher student complaints and technical issues. In other words, beyond a basic level, more surveillance didn’t yield proportionately more honest behavior; it mainly yielded diminishing returns and higher costs (social and financial). This resonates with prior integrity research which suggests overemphasis on deterrence can backfire or yield marginal gains (UBC, 2023). A balanced approach (some deterrence but also trust-building) tends to work best. To probe whether the correlation persists after accounting for structural differences, we estimated an ordinary least squares model with flag-rate as the dependent variable and AAPI, log-enrolment, regional GDP per capita (World Bank, 2024), and average national fixed-broadband bandwidth (ITU, 2024) as controls.

Table 3 reports the results: AAPI retains a significant negative coefficient (β = −0.31, SE = 0.10,

p = .003), while GDP per capita and bandwidth are non-significant. Variance Inflation Factors < 2 indicate no multicollinearity. These findings strengthen the inference that policy orientation, rather than macro-economic endowment, predicts healthier integrity signals.

Returning to the AAPI correlation, we did find a statistically significant negative correlation between AAPI and a composite “surveillance reliance” score (combining proctoring use and detector use) – which is expected by definition, since surveillance is part of the index formula. More interestingly, AAPI showed a positive association with what we term “integrity health” signals: e.g., survey data from some institutions indicated that student self-reported cheating remained stable or even decreased in places that openly discussed AI ethics and adapted assessment (high AAPI), whereas it spiked where students felt “the rules didn’t change but now there’s an AI to help me cheat” (low AAPI, no redesign).

One thought-provoking insight came from student feedback: in high-surveillance environments, students reported feeling less guilty about cheating (“everyone’s trying to catch me, so if I can slip through, it’s fair game”), whereas in environments where the institution said, “we trust you to use AI ethically, here’s how to do it,” students felt a greater sense of responsibility not to violate that trust. This aligns with psychological theories of academic integrity that highlight the role of student moral development and rationalization (see also Hughes & McCabe, 2006 for a foundational definition of academic misconduct) – if treated as partners rather than potential criminals, students may rationalize cheating less (UBC, 2023). Quotes from thought leaders echo this: Dr. Thomas Lancaster, an academic integrity scholar, has argued that “integrity is a two-way street – institutions must show integrity (fairness, transparency) if they expect students to live by it.” Similarly, Audrey Watters, an ed-tech critic, pointed out the flaw in assuming technology alone ensures honesty: “[Proctoring companies] assume everyone looks the same, takes tests the same way… which is not true or fair” (Avi, 2020) – calling instead for rethinking assessment design.

Bias and Equity Concerns: From a critical-realist stance, such biases are not epiphenomenal but stem from deep causal mechanisms—commercial data regimes and linguistic hierarchies—that operate beneath observable policy scripts. Post-colonial scholars label this mechanism “digital colonialism,” warning that AI tools calibrated on Global-North corpora risk recording colonial asymmetries into algorithmic form (Couldry & Mejias, 2019; Salami, (2024). A major theme in our discussion is how AI governance choices can inadvertently introduce bias. Our findings on detector bias against non-native English writing (Stanford HAI, 2023) reveal an epistemological pitfall: if knowledge and writing quality are judged by AI-driven perplexity or similar metrics, we risk privileging certain linguistic styles (often Western, native-speaker norms) as “original” while marking others as suspicious. This has civilizational implications – effectively, a form of algorithmic cultural bias that could penalize diverse expression and thought. High-AAPI institutions addressed this by either refraining from using such detectors on non-English content or by adjusting thresholds and involving human judgment, as mentioned. Low-AAPI ones risk propagating a new bias under the banner of integrity.

Another bias is in proctoring: facial recognition algorithms used in some proctoring software have known racial biases (less accurate with darker skin tones) (Avi, 2020). In one case, a student with a dark complexion struggled to get the proctoring AI to recognize him under normal lighting – leading to delays in taking the exam (Avi, 2020). “There are so many systemic barriers … this is just another example,” that student was quoted (Avi, 2020). Institutions with high awareness (often through VSD lens) insisted on “human-in-the-loop” overrides – e.g., a proctoring system flag wouldn’t automatically fail a student; a human would review the footage to account for such issues. Others without such nuance might have simply let the algorithm decide, potentially disqualifying test-takers due to technical bias. Clearly, policies embedding fairness and accessibility checks (part of AAPI’s equity dimension) are critical for not exacerbating inequalities.

Taken together, our correlational findings support the notion that a sociotechnical, human-centered approach to AI in assessment tends to cultivate a more genuine culture of integrity with fewer crises, whereas a surveillance-heavy approach can yield a flood of red flags (not all meaningful) and contentious disciplinary actions without clearly reducing cheating. This does not mean that simply writing a nice policy cures all ills – but it does indicate that how institutions respond matters.

However, we acknowledge limitations: some high-AAPI institutions might appear to have fewer cheating cases simply because they don’t look as hard (i.e., they’re not actively hunting with detectors). Could it be a “ignorance is bliss” effect? Possibly, but we counter that the alternate approach is “false alarms galore” which has its own perils. The goal is a smarter equilibrium: design assessments that inherently discourage cheating and foster learning (so there’s less to catch), and use targeted, proportionate detection measures (so you catch truly egregious cases) (Liu & Bates, 2025). This aligns with what TEQSA in Australia advocated – ensuring assessments both integrate AI and maintain trustworthy evidence of student learning (Liu & Bates, 2025).

In conclusion, our findings lend empirical weight to the argument that integrity is best safeguarded by design and education rather than by surveillance alone. High AAPI institutions are essentially redesigning the system to mitigate misconduct upstream, whereas low AAPI ones chase misconduct downstream, often at cost to trust and equity. The next part of the discussion delves deeper into the cross-disciplinary perspectives and the broader implications of these patterns – touching on ethics, policy diffusion, and epistemology.

4.4. Equity, Ethics, and Governance: Cross-Disciplinary Perspectives

Beyond immediate outcomes, the rise of AI in assessment governance forces reflection on deeper questions of equity, ethical governance, and epistemology. Our analysis, enriched by AI ethics and development studies literature, highlights several critical implications for low-resource, postcolonial contexts.

4.4.1. Postcolonial Perspectives and Technocratic Policy Diffusion

A recurring concern is the diffusion of technocratic solutions from the Global North to South without full regard for contextual fit – a phenomenon some term “digital colonialism.” Many AI tools (detectors, proctoring AI, even generative models) are developed by Western firms or researchers, encoding particular assumptions. When universities in the Global South adopt these en masse (often under pressure to appear “modern” or due to lack of locally-developed alternatives), they may inadvertently import Western-centric norms of surveillance and control. UNESCO’s guidance, while globally intended, itself had to reconcile different visions; a critical analysis by Mochizuki et al. (2025) suggests UNESCO’s AI in education documents “privilege particular cultural, socio-political and economic ideologies” – aligning at times more with Big Tech and government interests than with grassroots educational values (Mochizuki et al., 2025). This implies that even well-meaning international guidelines can carry the imprint of powerful actors’ ideologies (e.g., a techno-solutionist bias that assumes AI is the answer to AI). For example, pushing AI detectors could be seen as a techno-solutionist stance – treating AI as both cause and cure of cheating – which conveniently benefits ed-tech vendors. Such policies may diffuse quickly under institutional isomorphism, but in postcolonial contexts, they might clash with local realities (e.g., lower trust in surveillance due to historical state surveillance, or communal approaches to learning that are misinterpreted as cheating by Western standards).

The epistemological concern is that a monoculture of algorithmic governance could undermine pluralistic, indigenous approaches to knowledge and integrity. If, for instance, an African ODL institution feels compelled to use US-developed AI proctoring that is insensitive to local exam-taking behaviors or communal living conditions, it imposes a foreign notion of what constitutes “proper” exam conduct. Similarly, AI text detectors trained primarily on Standard American English writing may implicitly define what “legitimate” writing looks like, other styles be damned (Stanford, 2023). This echoes a worry identified by AI ethicists: generative AI systems are “mostly trained on dominant worldviews”, potentially marginalizing minority perspectives (North, 2023). If universities start valuing work based on whether it passes an AI originality check rather than its substantive merit, they inadvertently elevate those dominant linguistic patterns as a gatekeeper for academic validity.

4.4.2. Academic Integrity Norms and the Human Element

Traditional academic integrity has always been anchored in values like honesty, trust, fairness, responsibility, and respect. Introducing AI and algorithmic checks doesn’t remove the human element – it shifts it. The norms may need reinterpreting (e.g., is using an AI paraphrasing tool akin to using a thesaurus or is it cheating?). Our review noticed that higher-scoring policies tend to update integrity norms clearly: they define what constitutes acceptable AI assistance and what crosses into misconduct. This clarity is crucial for students to understand evolving expectations. Conversely, some low-scoring policies just say “use of AI = cheating,” which can be both draconian and impractical (AI is ubiquitous; where to draw the line?). This binary view might drive misconduct underground or cause students to hide use that could be pedagogically beneficial if out in the open (like getting AI to explain a concept). Thus, policy design should promote a norm where transparency about AI use is encouraged (a value of honesty) rather than driving usage into the shadows. Many high-AAPI institutions require students to acknowledge any AI assistance, treating undisclosed use as the violation – this aligns integrity with transparency, not with a futile attempt to ban AI entirely (Liu & Bates, 2025).

4.4.3. AI Detector Bias and Fairness

The detector bias issue we discussed has fairness implications: it means integrity enforcement is not being applied equitably. A student writing in a second language or with a certain writing style could be unfairly suspected. This introduces a systemic bias in academic integrity proceedings – essentially a new form of discrimination. Our findings underscore that any institution using AI detection must incorporate fairness checks (e.g., the policy some adopted: “AI flags will not be used as sole evidence; students have the right to appeal and present their writing process”). Some institutions even entirely disabled their Turnitin AI detector due to bias concerns (Ramírez Castañeda, 2025; Sample, 2023) – for instance, Vanderbilt University (USA) publicly announced disabling it, noting “AI detectors have been found to be more likely to label text by non-native speakers as AI-written” (Coley, 2023). Ensuring due process and not treating detector output as gospel is a key ethical governance point. On the flipside, institutions that ignored these issues may face what one might call algorithmic injustice – punishing students for a “crime” they did not commit, based on flawed evidence. Such experiences can severely erode trust in the institution and the legitimacy of its assessment.

4.4.4. Data Privacy and Student Agency

The expanded use of monitoring tools raises urgent privacy questions. Students are being asked to surrender a lot of personal data (screen activity, keystrokes, video in their home, sometimes even biometric identifiers) for the sake of exam surveillance (Avi, 2020; Scassa, 2023). In many Global South countries, data protection regimes are still nascent, meaning students may have little recourse if that data is misused or breached. An ethically governance-minded policy would adhere to principles of necessity, proportionality, and informed consent (as advocated by privacy scholars [Scassa, 2023]). Few of the policies we reviewed explicitly mention data privacy protections, suggesting a gap. One bright spot: some high-AAPI institutions did state that any third-party AI or proctoring tool must comply with privacy laws and that students must be informed about what data is collected and have the right to opt-out or alternatives if possible. For instance, a university in Europe (GDPR jurisdiction) added a clause that students could choose a human proctor exam if they did not want to be recorded by AI software – a concession to personal agency. Low-resource contexts often lack such options, unfortunately – they might depend on a single vendor’s platform. There is a risk of surveillance creep, where measures introduced for AI cheating get normalized and repurposed for broader control (e.g., monitoring student attentiveness, etc.). Civil society groups and student unions in many countries are pushing back, emphasizing that education should not become a panoptic surveillance exercise (Avi, 2020; Scassa, 2023). This is a call for ODL institutions to find solutions that respect privacy – perhaps leveraging more trust-based and community proctoring models where possible, or technological solutions that are less intrusive (some are exploring “open book, open internet” exams graded differently).

4.4.5. Civilizational and Epistemological Implications

On a philosophical level, our findings provoke questions about the future of knowledge and assessment. If AI can generate answers, does assessment shift to evaluating the process and critical thinking rather than the answer itself? Many high-AAPI policies hint at this by encouraging process documentation, reflections, and viva voce elements – a move away from rote product to human process and metacognition. This is an epistemological shift: knowledge demonstration becomes about what can you do that AI cannot easily do? – often creativity, personal context, ethical reasoning, or multi-step problem solving. It also raises the idea of embracing AI as a cognitive partner – some scholars argue that completely barring AI use is like forbidding calculators; instead, we should teach AI fluency and test higher-order skills. The policies with AI literacy components aim to do that – to treat understanding how to use AI responsibly as a new learning outcome. This could democratize education if done right (everyone equipped with AI skills) or could widen divides if not (only privileged students learn how to use AI well, others either misuse it or are punished for it).

The civilizational stake is trust in higher education qualifications. If misuse of AI becomes rampant and unaddressed, degrees risk losing credibility (“did a human earn this or a chatbot?”). Conversely, if surveillance overshadows pedagogy, the university risks becoming an Orwellian space that stifles creativity and well-being – undermining the very purpose of education as a place of intellectual exploration. We stand at a crossroads: one path leads to a “surveillant university” where algorithms govern every aspect of student behavior (Scassa, 2023), and the other to a “sociotechnical university” where human values steer technology to enrich learning. Our cross-disciplinary analysis – drawing from AI ethics, education policy, law, and development – strongly suggests that the latter is the only sustainable, equitable path for the Global South. This path means consciously designing policies that are context-sensitive (recognizing infrastructural and cultural differences), ethically grounded (protecting rights and inclusivity), and future-oriented (preparing students for an AI-rich world rather than shielding them from it in the short term).

In practice, this might involve Global South institutions leveraging frameworks like VSD to ensure local values (community, equity, cultural diversity) are embedded. It might also mean a greater emphasis on South-South collaboration: sharing experiences and potentially developing indigenous solutions (for example, an open-source AI writing advisor that could be used ethically, or regionally trained AI detectors that understand local languages better – albeit still with caution). There is a strong argument for capacity-building: UNESCO’s guidance calls for building teacher and researcher capacity in AI (North, 2023), which is especially needed in low-resource settings so they can critically adapt (or resist) external technologies rather than just consume them.

4.4.6. Thought Leader Reflections

To bring voices to these points, consider a quote by James Zou (co-author of the detector bias study): “Current detectors are clearly unreliable and easily gamed, which means we should be very cautious about using them as a solution to the AI cheating problem.” (Stanford HAI, 2023) This encapsulates the folly of over-relying on tech when the tech itself is flawed – a direct plea for more holistic solutions. Another perspective, from Audrey Azoulay, UNESCO’s Director-General, emphasized that AI governance in education must keep the “primary interest of learners” at heart (North, 2023) – not the interest of appeasing rankings or political pressure. This means equity and inclusion should be front and center, as per UNESCO’s first guideline: “promote inclusion, equity, linguistic and cultural diversity” in AI use (North, 2023). If Global South institutions take that seriously, they will be wary of one-size-fits-all imported solutions and instead adapt AI to their multilingual, diverse student bodies – for instance, insisting that AI tools they use support local languages and are free of bias, and focusing on closing the digital divide (making sure all students have access to necessary technology and training) (North, 2023).

To sum up, the cross-disciplinary perspective underscores that AI in assessment is not just an IT or academic issue; it’s a sociotechnical and ethical governance challenge. Getting it right is crucial for educational equity and the decolonization of knowledge – ensuring that the AI revolution in education does not simply impose a new form of Western hegemony or exacerbate inequality, but rather becomes an opportunity to re-imagine assessment in a way that is more fair, creative, and aligned with human development goals. Our analysis provides evidence and examples of both pitfalls and promising practices on this front. In the final section, we will synthesize these insights into concrete recommendations and a forward-looking roadmap.