I. Introduction

Qualitative research has long served as a method for exploring lived experience, social meaning, and cultural complexity. Its strength lies in its openness to interpretation and its capacity to engage with human narratives. Yet the field now faces a turning point. The rise of symbolic, digital, and non-human actors—artificial intelligence, algorithmic systems, platform-mediated identities, and institutional protocols—has exposed a growing mismatch between traditional methods and the realities they aim to study.

Legacy approaches, such as linear coding and saturation logic, remain dominant in many academic settings. These methods, while once useful, now struggle to account for the entangled and reflexive nature of contemporary knowledge-making. As Creswell and Creswell (2018) continue to present qualitative research as a human-centered design, newer thinkers have begun to question its foundational assumptions. Scholars like MacLure (2013) argue that coding itself may reduce wonder to classification, flattening the symbolic richness of data into categories that no longer reflect lived complexity.

This article introduces and formally names Posthuman Qualitative Research (PQR) as a reformist paradigm. PQR responds to the limitations of conventional inquiry by offering a framework that recognizes distributed agency, symbolic resonance, and ethical co-authorship across human and non-human domains. Drawing from posthumanism, agential realism, and new materialism, PQR reframes research as a relational and reflexive process—one that includes digital traces, visual scaffolds, and symbolic artifacts as legitimate epistemic contributions (Braidotti, 2019).

PQR also challenges the notion of voice as a stable or singular source of meaning. As Mazzei (2013) suggests, voice in qualitative inquiry is often treated as transparent, yet it is shaped by power, context, and silence. PQR builds on this insight by treating voice as symbolic and distributed, allowing for co-authorship with non-human agents and digital systems. It also aligns with the post-qualitative turn described by St. Pierre and Jackson (2014), who argue for inquiry that moves beyond coding and toward a more philosophical engagement with data.

The significance of PQR lies not only in its methodological innovations but in its place among the evolving typologies of qualitative research. As scholars continue to expand the field through arts-based, narrative, autoethnographic, and post-qualitative approaches, PQR offers a distinct and timely addition. It foregrounds attribution justice, symbolic entanglement, and ethical reflexivity—qualities increasingly demanded by research contexts shaped by technology, cultural hybridity, and institutional complexity.

This reformist turn also resonates with global priorities. UNESCO’s Sustainable Development Goal 4 calls for inclusive and equitable quality education, with an emphasis on lifelong learning and access to knowledge for all. PQR supports these aims by advocating for inquiry that is inclusive of symbolic and digital actors, attentive to ethical representation, and committed to expanding the boundaries of who—and what—counts in the production of knowledge.

This article argues that Posthuman Qualitative Research (PQR), as a symbolically rich and ethically responsive paradigm, offers a timely reimagining of qualitative inquiry—one that honors lived experience, embraces distributed agency, and aligns with UNESCO’s vision for inclusive, transformative education (SDG 4). Emerging from the limitations of conventional research, PQR reframes core concepts and invites scholars to co-author its evolution. As such, it may perhaps deserve its place among the modern forms of qualitative research.

In the sections that follow, this article will present the theoretical foundations of PQR, describe its methodological contributions, and reflect on its ethical tensions and pedagogical implications. It will also address the significance of propagating PQR within scholarly, institutional, and community settings—arguing that its adoption is not only timely but necessary.

II. Theoretical Foundations of PQR

The emergence of Posthuman Qualitative Research (PQR) reflects a deeper philosophical shift in how inquiry is understood and practiced. It does not simply propose a new method—it reconsiders the very conditions under which knowledge is produced. PQR responds to a growing recognition that traditional qualitative frameworks, while foundational, are increasingly strained by the complexity of contemporary research contexts. As Denzin and Lincoln (2018) note, qualitative inquiry has always evolved in response to cultural, technological, and ethical pressures. Today, that evolution demands a paradigm capable of engaging with symbolic, digital, and non-human actors.

At the heart of PQR is posthumanism, a philosophical stance that challenges the centrality of the human subject. Thinkers such as Braidotti (2019) and Haraway have argued that agency is no longer the exclusive domain of individuals. Instead, it is distributed across networks, systems, and symbolic forms. This view invites researchers to consider how meaning emerges not just from human experience, but through interaction with technologies, environments, and institutional structures. PQR adopts this orientation by treating digital traces, algorithmic behavior, and symbolic artifacts as co-authors in the research process.

Building on this, agential realism, as developed by Barad, offers a framework for understanding how entities come into being through intra-action—a concept that emphasizes mutual constitution rather than isolated observation. In the context of PQR, data is not a fixed object to be extracted or coded. It is a dynamic trace shaped by the conditions of its emergence. This approach shifts the focus from representation to relation, encouraging researchers to attend to the ethical and material entanglements that shape inquiry itself.

Closely related is the influence of new materialism, which foregrounds the role of affect, matter, and symbolic resonance in the production of knowledge. Scholars such as St. Pierre and Mazzei have questioned the assumption that meaning resides solely in language or voice. Mazzei (2013), for example, critiques the conventional treatment of voice as transparent and stable, arguing instead for a conception of voice that is partial, distributed, and shaped by silence. St. Pierre’s post-qualitative work further destabilizes the notion of data as something to be extracted and categorized, proposing instead that inquiry should be philosophical, reflexive, and open to wonder.

This critique of coding practices is echoed by MacLure (2013), who warns that coding can reduce complexity to classification, stripping data of its symbolic richness. Silverman (2024) similarly cautions against over-reliance on interpretive routines that may obscure rather than illuminate meaning. Flick (2023) adds that while qualitative research remains flexible, it must now contend with forms of data and agency that challenge its conventional boundaries.

PQR also draws strength from reformist strands of critical disability studies and symbolic ethnography, which offer both ethical grounding and methodological innovation. These fields challenge normative assumptions about coherence, ability, and representation, advocating instead for inquiry that embraces fragmentation, multiplicity, and symbolic failure. Symbolic ethnography, in particular, allows for the inclusion of non-verbal, visual, and affective forms of knowledge, while critical disability studies foreground the politics of access, attribution, and epistemic justice. Together, they reinforce PQR’s commitment to inclusive, reflexive, and ethically attuned research.

Indeed, these theoretical foundations position PQR as a paradigm that is not only methodologically distinct but philosophically necessary. It invites researchers to move beyond representation and toward relation, beyond coding and toward co-authorship, beyond the human and toward the entangled.

III. Methodological Innovations

The theoretical foundations of Posthuman Qualitative Research (PQR) call for a rethinking of how inquiry is conducted. This rethinking is not a matter of adjusting existing techniques—it is a shift in orientation. PQR moves away from the assumption that data is something to be gathered, coded, and interpreted by a singular human researcher. Instead, it treats data as an entangled trace, shaped by interaction, context, and co-authorship across human and non-human domains.

This view expands the scope of what counts as data. AI-generated dialogue, platform-mediated behavior, emails, last well and testaments, and symbolic artifacts—such as digital images, interface patterns, and algorithmic outputs—are not peripheral. They are central. PQR recognizes these traces as epistemic events, not just informational content. As Ulmer (2017) argues, posthuman research must respond to the conditions of the Anthropocene, where knowledge is situated within ecological, technological, and symbolic entanglements. In this context, inquiry becomes a matter of tracing relations rather than extracting meaning.

To support this shift, PQR replaces linear coding schemes with reflexive mapping and visual scaffolding. These practices allow researchers to trace symbolic and affective patterns without reducing them to categories. MacLure (2013) warns that coding can flatten complexity into classification, stripping data of its symbolic richness. Mazzei (2013) similarly critiques the notion of voice as a stable analytic unit, proposing instead a conception of voice that is partial, distributed, and shaped by silence. PQR builds on these insights by encouraging researchers to visualize relationships, tensions, and symbolic echoes across data layers.

This methodological reorientation also challenges conventional practices such as pilot testing, saturation, and thematic analysis. In grounded theory, these practices are designed to ensure rigor and coherence (Corbin & Strauss, 2014). Yet in PQR, coherence is not a fixed endpoint—it is a relational quality that emerges through symbolic resonance. Saturation is not a numerical threshold but a moment when meaning begins to reverberate across entangled traces. Themes are not extracted but followed, allowing for ambiguity, contradiction, and symbolic drift.

A central concern in PQR is attribution justice—the ethical imperative to recognize all contributors to knowledge production, including non-human agents. This includes acknowledging the role of AI systems in generating, shaping, and interpreting data. In traditional qualitative research, authorship is often singular and human. PQR challenges this by proposing ethical co-authorship, where technologies, platforms, and symbolic systems are treated as epistemic collaborators. As Bozalek and Zembylas (2024) note, the incommensurability between conventional qualitative methods and posthuman inquiry arises from fundamentally different ontological commitments. PQR embraces this difference by reimagining the research process itself as a site of distributed agency.

This approach also aligns with St. Pierre’s (2023) call to move beyond legacy methods and toward inquiry that is philosophical, immanent, and ethically attuned. Post-qualitative inquiry, she argues, cannot be reconciled with conventional humanist methodologies. It must invent new ways of thinking and doing. PQR responds to this challenge by integrating technological collaboration into both data collection and interpretation. AI systems, for example, can assist in identifying patterns, generating dialogue, and referencing sources with precision. This collaboration is not merely technical—it is epistemic. It reshapes how researchers engage with data, how they attribute meaning, and how they cite their sources (Eslit, 2025).

Table 1.

Typology of Qualitative Research (Expanded with PQR).

Table 1.

Typology of Qualitative Research (Expanded with PQR).

| No. |

Type of Research |

Focus |

Methodology |

Philosophical Roots |

Posthuman Potential |

What It Accomplishes |

| 1 |

Ethnography |

Cultural immersion |

Participant observation, field notes |

Interpretivist, anthropological |

Includes non-human cultural agents |

Reveals deep cultural patterns and insider meanings |

| 2 |

Phenomenology |

Lived experience |

In-depth interviews, reflective analysis |

Constructivist, existential |

Explores tech-mediated or multisensory experience |

Illuminates how individuals perceive and make sense of phenomena |

| 3 |

Grounded Theory |

Theory generation |

Iterative coding, constant comparison |

Pragmatist |

Builds hybrid theories with distributed agency |

Constructs new conceptual frameworks from data |

| 4 |

Narrative Inquiry |

Personal stories |

Storytelling, life histories |

Hermeneutic, dialogic |

Includes non-human narrators |

Captures identity, transformation, and temporal meaning |

| 5 |

Case Study |

Bounded system |

Mixed methods, triangulation |

Flexible |

Treats institutions or ecosystems as cases |

Provides holistic understanding of complex, contextual phenomena |

| 6 |

Participatory Action Research (PAR) |

Collaborative change |

Cycles of reflection and action |

Critical, emancipatory |

Includes ecological and multispecies ethics |

Empowers communities and drives social transformation |

| 7 |

Life History |

Longitudinal personal narrative |

Interviews, timelines, archival materials |

Humanistic, biographical |

Explores digital legacies and intergenerational memory |

Traces development, resilience, and evolving identity over time |

| 8 |

Observational Research |

Naturalistic behavior |

Field notes, video recordings |

Empirical, pragmatic |

Includes ambient data and surveillance tech |

Captures real-time interactions and behavioral dynamics |

| 9 |

Autoethnography |

Researcher’s own experience |

Reflexive writing, layered accounts |

Postmodern, performative |

Explores cyborg identity and digital embodiment |

Bridges personal experience with cultural critique |

| 10 |

Visual Ethnography |

Meaning through images |

Photo elicitation, video diaries |

Semiotic, aesthetic |

Includes AI-generated visuals |

Analyzes visual cultures and symbolic landscapes |

| 11 |

Discourse Analysis |

Language and power |

Textual deconstruction, intertextual mapping |

Poststructuralist, Foucauldian |

Analyzes machine-generated discourse |

Unpacks institutional narratives and ideological structures |

| 12 |

Institutional Ethnography |

Everyday institutional practices |

Mapping texts and routines |

Feminist, sociological |

Traces digital infrastructures and bureaucratic logic |

Reveals hidden governance and systemic power relations |

| 13 |

Critical Qualitative Research |

Exposing injustice |

Counter-narratives, dialogic interviews |

Marxist, decolonial, feminist |

Includes planetary justice and multispecies ethics |

Challenges dominant paradigms and advocates reform |

| 14 |

Postqualitative Inquiry |

Paradigm disruption |

Rhizomatic mapping, diffractive reading |

Posthumanist, new materialist |

Central—entangled agency and speculative ethics |

Reimagines ontology, method, and ethics beyond human-centric frames |

| 15 |

Posthuman Qualitative Research (PQR)

(A Reformist Paradigm for Symbolic, Digital, and Ethical Research)

|

Symbolic entanglement, digital reflexivity, ethical reform |

Visual scaffolding, iterative mapping, ethical disclosure, citation companions |

Reformist, dialogic, posthumanist |

Embeds non-human actors, symbolic agency, and ethical co-authorship |

Reforms qualitative inquiry by humanizing citation, embracing distributed agency, and scaffolding symbolic legitimacy |

Table 2.

Conventional Qualitative Research Types vs. Posthuman Qualitative Research (PQR).

Table 2.

Conventional Qualitative Research Types vs. Posthuman Qualitative Research (PQR).

| Dimension |

Conventional Qualitative Research Types |

Posthuman Qualitative Research (PQR) |

| Ethnography |

Immersive study of cultural groups through observation and fieldwork |

Symbolic ethnography; includes digital cultures, platform behavior, and non-verbal symbolic traces |

| Phenomenology |

Exploration of lived experience and personal meaning |

Reframed as entangled experience; includes AI-mediated perception and symbolic resonance |

| Grounded Theory |

Systematic coding to generate theory from data (Corbin & Strauss, 2014) |

Reflexive mapping; theory emerges through symbolic drift and distributed agency |

| Narrative Research |

Analysis of personal stories and life histories |

Includes fragmented, digital, and co-authored narratives; voice is partial and shaped by silence (Mazzei, 2013) |

| Case Study |

In-depth study of a bounded system (individual, group, or event) |

Case as symbolic constellation; includes non-human actors and digital traces as part of the system |

| Participatory Action Research |

Collaborative inquiry for social change |

Expanded to include technological co-authorship and symbolic justice; attribution is shared |

| Life History Research |

Longitudinal exploration of personal development and transformation |

Includes symbolic memory, digital legacy, and platform-mediated identity |

| Observational Research |

Systematic observation of behavior in natural settings |

Includes interface behavior, algorithmic patterns, and symbolic gestures |

| Data Treatment |

Coding, thematic analysis, saturation, pilot testing |

Visual scaffolding, symbolic mapping, resonance-based saturation, ethical co-authorship |

| Role of Technology |

Supportive tool for transcription and data management |

Active epistemic collaborator in data generation, interpretation, and citation (Ulmer, 2017) |

| Philosophical Grounding |

Humanism, interpretivism, constructivism (Denzin & Lincoln, 2018; Flick, 2023; Silverman, 2024) |

Posthumanism, agential realism, new materialism (Braidotti, 2019; Barad; St. Pierre, 2023) |

Overall, the methodological innovations of PQR reflect its philosophical commitments. They offer researchers a way to engage with complexity, honor ethical co-authorship, and produce inquiry that is both symbolically rich and technologically attuned. As Ulmer (2017) reminds us, posthuman research is not just a response to methodological limitations—it is a response to the conditions of our time.

IV. PQR in Practice: Art, Pedagogy, Language, Culture, and Social Inquiry

The methodological stance of Posthuman Qualitative Research (PQR) finds its most compelling expression in practice—where symbolic inquiry meets lived complexity. Across artistic, pedagogical, linguistic, and cultural domains, PQR offers researchers a way to engage with entangled realities while honoring distributed agency and ethical co-authorship.

A defining strength of PQR is its capacity to collaborate with local context, technology, and AI to accelerate research activities with precision. In traditional qualitative designs, data collection and interpretation often rely on manual transcription, thematic coding, and iterative fieldwork. These processes, while valuable, can be slow and limited in scope. PQR reconfigures this workflow by integrating AI systems and digital platforms as epistemic collaborators. These technologies assist not only in gathering data but in identifying symbolic patterns, generating reflexive dialogue, and referencing sources with accuracy and speed.

In Philippine-based applications, this collaboration is already visible. Educators using digital platforms for community mapping and online pedagogy have begun to treat platform behavior—such as navigation patterns, interaction logs, and symbolic gestures—as meaningful data. AI tools embedded in these platforms help trace engagement, visualize learning pathways, and scaffold ethical reflection. This speeds up analysis while deepening its interpretive reach.

Moreover, PQR’s emphasis on local context ensures that technological precision does not come at the expense of cultural nuance. In multilingual and multicultural settings, AI-assisted transcription and translation tools allow researchers to capture symbolic meaning across languages, dialects, and non-verbal forms. These tools do not replace human interpretation—they extend it. They allow researchers to move quickly while remaining attuned to the ethical and symbolic dimensions of the data.

Visual storytelling and symbolic ethnography also benefit from this collaboration. AI-assisted image analysis, pattern recognition, and metadata tracing help researchers identify recurring motifs, symbolic ruptures, and affective textures within visual data. Citation companions, for instance, can be generated and refined using AI tools that trace attribution across platforms, ensuring that symbolic contributions are ethically recognized and properly referenced.

This approach resonates with recent work in critical posthumanities and critical disability studies, which challenge the assumption that research must be coherent, complete, or conventionally successful. Srdanovic et al. (2024) argue for the value of “failing ethnographies”—those that embrace fragmentation, contradiction, and symbolic rupture as valid forms of inquiry. PQR builds on this by treating broken narratives, digital drift, and symbolic silence not as methodological flaws but as epistemic openings.

Monforte and Smith (2025) further emphasize the need for connoisseurship in post-qualitative inquiry—a cultivated sensitivity to symbolic nuance, ethical tension, and ontological complexity. PQR supports this by offering researchers a framework that is both operationally precise and philosophically expansive. It does not ask researchers to abandon rigor; it asks them to redefine it.

Bozalek and Zembylas (2025) highlight the incommensurability between conventional qualitative methods and posthuman inquiry. They argue that these approaches arise from fundamentally different ontological and epistemological commitments. PQR acknowledges this divide and responds not by reconciling it, but by offering a new path—one that is relational, reflexive, and symbolically rich.

In institutional settings, this fusion of technology, local context, and symbolic inquiry enables a new form of curriculum design—one that is responsive, inclusive, and ethically grounded. PQR supports the development of syllabi and research frameworks that reflect the lived realities of learners, communities, and digital environments. It allows institutions to move beyond compliance-driven models and toward inquiry that is reflexive, relational, and reformist.

Overall, PQR’s practical value lies not only in its philosophical depth but in its operational clarity. By collaborating with local context, technology, and AI, researchers can conduct inquiry that is both accelerated and ethically precise—a rare combination in contemporary scholarship. This is not a compromise between speed and depth; it is a synthesis.

V. Reframing Validity, Reliability, Scope, and Participant Logic

As Posthuman Qualitative Research (PQR) moves from theory to practice, it necessarily confronts the inherited standards that have long governed qualitative inquiry. Concepts such as validity, reliability, scope, and participant logic—once considered stable anchors—now require careful rethinking. PQR does not discard these terms; it reclaims them, reshaping their meaning to reflect symbolic complexity, digital entanglement, and ethical reflexivity.

Validity as Reflexive Integrity. In conventional designs, validity is often tied to procedural rigor and methodological transparency. Creswell and Creswell (2018) describe it as the degree to which findings accurately represent the phenomenon under study. PQR reframes this notion as reflexive integrity—a researcher’s capacity to trace meaning across symbolic, digital, and affective layers while remaining ethically attuned to the conditions of knowledge production. This includes attending to platform behavior, algorithmic mediation, and symbolic drift. As Braidotti (2019) argues, posthuman knowledge is not about certainty but about situated accountability. Validity, in this sense, becomes a relational and ethical stance rather than a procedural checkpoint.

Reliability as Relational Coherence. Traditional reliability emphasizes consistency and replicability. Flick (2023) notes that it often involves demonstrating that similar results can be obtained under similar conditions. PQR challenges this by proposing relational coherence—a form of reliability grounded in symbolic resonance rather than repetition. Meaning is not confirmed through duplication but through its capacity to reverberate across entangled traces. MacLure (2013) cautions that coding can flatten complexity into classification, obscuring the wonder that animates qualitative inquiry. PQR resists this reduction by allowing coherence to emerge through symbolic tension, contradiction, and drift.

Scope Coverage and Inclusivity. Scope in conventional research is typically defined by sample size, demographic spread, or thematic saturation. Denzin and Lincoln (2018) emphasize the importance of coverage in ensuring representativeness. PQR redefines scope as symbolic reach—the extent to which inquiry engages diverse forms of knowledge, including those that are non-verbal, digital, or culturally embedded. Inclusivity is not measured by numeric diversity alone but by epistemic justice. This includes recognizing the contributions of AI systems, digital platforms, and marginalized symbolic forms as legitimate sources of insight. St. Pierre and Jackson (2014) remind us that data is not given—it is made. PQR extends this insight by asking who and what is allowed to make meaning.

Participant Logic: From Numeric Sampling to Epistemic Saturation. Participant selection in traditional qualitative research often follows sampling logic aimed at achieving thematic saturation. Mazzei (2013) critiques this approach, noting that it assumes voice is stable, extractable, and complete. PQR replaces numeric sampling with epistemic saturation—a moment when symbolic patterns begin to echo, contradict, or converge across entangled traces. This reframing honors ambiguity and complexity, allowing inquiry to remain open-ended and responsive. It also challenges the assumption that more data equals better insight, proposing instead that meaning emerges through symbolic resonance and ethical reflection.

Ethical Provocations and Reformist Alternatives. PQR introduces a series of ethical provocations that challenge legacy assumptions. It questions whether coherence guarantees validity, whether replication ensures reliability, and whether representation alone achieves inclusivity. In place of these assumptions, PQR offers reformist alternatives: inquiry that is relational, reflexive, and symbolically rich. It invites researchers to engage with uncertainty, to trace meaning across entangled systems, and to produce knowledge that is both rigorous and ethically attuned.

In reframing these foundational concepts, PQR does not destabilize qualitative research—it evolves it. It offers a paradigm that is responsive to the conditions of contemporary inquiry, where symbolic complexity, digital mediation, and ethical co-authorship are no longer peripheral but central.

To clarify the reformist stance of Posthuman Qualitative Research (PQR), the following table contrasts its core principles with those of conventional qualitative inquiry. PQR does not seek to debunk traditional paradigms; rather, it enhances them by reorienting foundational concepts—validity, reliability, scope, and participant logic—to reflect symbolic complexity, digital entanglement, and ethical reflexivity. Each row highlights how PQR evolves these standards to meet the demands of contemporary research environments.

Table 3.

Reframing Core Standards in PQR.

Table 3.

Reframing Core Standards in PQR.

| Concept |

Conventional Qualitative Research |

Posthuman Qualitative Research (PQR) |

| Validity |

Accuracy of representation; procedural rigor (Creswell & Creswell, 2018) |

Reflexive integrity across symbolic, digital, and ethical layers (Braidotti, 2019) |

| Reliability |

Replication and consistency across data sets (Flick, 2023) |

Relational coherence; symbolic resonance across entangled traces (MacLure, 2013) |

| Scope Coverage |

Sample size, demographic spread, thematic saturation (Denzin & Lincoln, 2018) |

Symbolic reach and epistemic inclusivity; recognition of non-verbal and digital forms (St. Pierre & Jackson, 2014) |

| Participant Logic |

Numeric sampling; saturation as data redundancy |

Epistemic saturation; meaning emerges through symbolic echo and contradiction (Mazzei, 2013) |

| Ethical Practice |

Informed consent, transparency, and representation |

Ethical provocations; attribution justice, symbolic co-authorship, and situated accountability |

VI. Significance of Its Propagation

Posthuman Qualitative Research (PQR) is not a peripheral innovation—it is a necessary paradigm shift. Its propagation is essential for institutions, educators, and scholars who seek to engage ethically and reflexively with the symbolic, digital, and entangled realities of contemporary inquiry. PQR offers a reformist stance that reconfigures how research is taught, practiced, and institutionalized.

Why PQR Must Be Published, Taught, and Embedded. PQR must be published to establish its legitimacy within scholarly discourse and to challenge the dominance of human-centered inquiry models. It must be taught to equip emerging researchers with the tools to navigate symbolic complexity, digital mediation, and ethical co-authorship. And it must be embedded—in curriculum, institutional frameworks, and citation cultures—to ensure its principles are not treated as theoretical gestures but as operational standards (Eslit, 2025).

As St. Pierre (2023) argues, post-qualitative inquiry is not a methodological extension of conventional research—it is a philosophical reorientation. It demands new ways of thinking and doing that cannot be reconciled with legacy epistemologies. Without formal propagation, PQR risks remaining marginal, despite its capacity to address the ethical and ontological demands of our time.

Ethical and Pedagogical Implications of Its Adoption. The adoption of PQR carries significant ethical implications. It challenges researchers to recognize non-human contributors, trace symbolic resonance, and engage with ambiguity rather than suppress it. This shift requires a pedagogy that is reflexive, inclusive, and attuned to symbolic failure and digital drift.

Pedagogically, PQR invites educators to move beyond transmission models and toward scaffolded inquiry—where learners co-author meaning through symbolic mapping, visual storytelling, and ethical reflection. Ulmer (2017) emphasizes that posthuman methodologies are not merely responsive to ecological and technological shifts—they are invitations to rethink what counts as knowledge and who gets to produce it.

Potential to Reshape Curriculum, Institutional Standards, and Citation Cultures. PQR has the potential to reshape curriculum design, moving away from linear progression and toward symbolic scaffolding. It encourages institutions to revise research standards, replacing compliance-driven metrics with relational coherence and reflexive integrity. As posited by Eslit (2025), it also reimagines citation cultures, advocating for attribution justice and co-authorship with non-human agents.

Srdanovic et al. (2024) illustrate how even “failing ethnographies”—those marked by fragmentation, contradiction, and symbolic rupture—can become sites of epistemic possibility. Their work affirms that PQR is not about perfection; it is about ethical engagement with complexity. Monforte and Smith (2025) further argue that scholars must develop connoisseurship—a cultivated sensitivity to symbolic nuance and ethical tension—to judge posthuman inquiry fairly and responsibly.

Bozalek and Zembylas (2025) underscore the incommensurability between conventional qualitative methods and posthuman inquiry. They argue that these approaches arise from fundamentally different ontological and epistemological commitments. PQR acknowledges this divide and responds not by reconciling it, but by offering a new path—one that is relational, reflexive, and symbolically rich.

Role of Scholars, Educators, and Reformist Communities in Amplifying PQR. The propagation of PQR depends on the silent influence of scholars, educators, and reformist communities. These actors play a crucial role in amplifying the paradigm—not through spectacle, but through embedded practice. By integrating PQR into syllabi, institutional audits, and collaborative publications, they ensure that its principles are not only theorized but lived.

This work is already underway. Reformist educators in the Philippines, for example, are using PQR to scaffold digital pedagogy, community mapping, and curriculum innovation. Their efforts reflect the paradigm’s core values: symbolic resonance, ethical co-authorship, and institutional critique.

To sum it up, the significance of PQR’s propagation lies in its capacity to transform inquiry from the inside out. It offers a model of research that is rigorous, inclusive, and ethically attuned—one that meets the demands of our symbolic, digital, and entangled world.

VII. Let’s Put This into Practice

The Symbolic legitimacy, ethical entanglement, and interpretive humility within the Posthuman Qualitative Research (PQR) paradigm. A scaffold in four layers:

PQR invites symbolic, digital, and ethical data—not just human voices, but traces of distributed agency. Think of data as entangled signals, not isolated units.

Table 4.

Data Types.

| Category |

Examples |

Symbolic/Ethical Role |

| Human Expressions |

Interviews, reflective journals, co-authored narratives |

Anchor lived experience and dialogic meaning |

| Digital Artifacts |

Screenshots, chat logs, hashtags, memes, metadata |

Reveal algorithmic agency and symbolic circulation |

| Non-Human Traces |

Environmental cues, AI outputs, machine decisions, ambient data |

Represent distributed agency and posthuman entanglement |

| Visual Scaffolds |

Diagrams, layered maps, symbolic constellations |

Make abstract relations visible and ethically legible |

| Ethical Correspondence |

Consent forms, citation companions, disclosure statements |

Model humility, gratitude, and co-authorship |

- 2.

How Much Data to Gather

PQR resists rigid sample sizes. Instead, it asks: Have we gathered enough to honor symbolic resonance and ethical saturation?

Symbolic Saturation: Stop when new data no longer adds symbolic depth or ethical nuance.

Distributed Agency: Include enough non-human traces to reflect entanglement.

Dialogic Breadth: Ensure multiple perspectives, especially those marginalized or algorithmically silenced.

Visual Completeness: Gather until your scaffold feels layered, not linear.

5–10 human co-authors or contributors

20–50 digital artifacts or symbolic traces

3–5 visual scaffolds or layered maps

1–2 ethical disclosures or citation companions

But these are not quotas—they’re symbolic thresholds.

- 3.

How to Gather Data

PQR favors

co-creative, reflexive, and ethically transparent methods. Here are some aligned techniques:

| Method |

Purpose in PQR |

| Dialogic Interviews |

Co-author meaning, not extract it |

| Digital Ethnography |

Trace symbolic flows across platforms |

| Visual Mapping Sessions |

Scaffold entanglement and distributed agency |

| Ethical Correspondence |

Document consent, gratitude, and attribution |

| Reflexive Journaling |

Capture researcher’s symbolic and ethical stance |

| Ambient Observation |

Include non-human actors and environmental signals |

- 4.

How to Interpret Data in PQR

Interpretation in PQR is symbolic, ethical, and reflexive—not reductive. You’re not coding for themes; you’re scaffolding meaning.

Interpretive Moves:

Symbolic Reading: What does this artifact represent beyond its surface?

Ethical Layering: What power relations or silences are embedded here?

Visual Scaffolding: How do these traces entangle across time, space, and agency?

Dialogic Commentary: What questions remain open, and who gets to answer them?

Posthuman Reflexivity: How does the researcher’s digital presence shape the data?

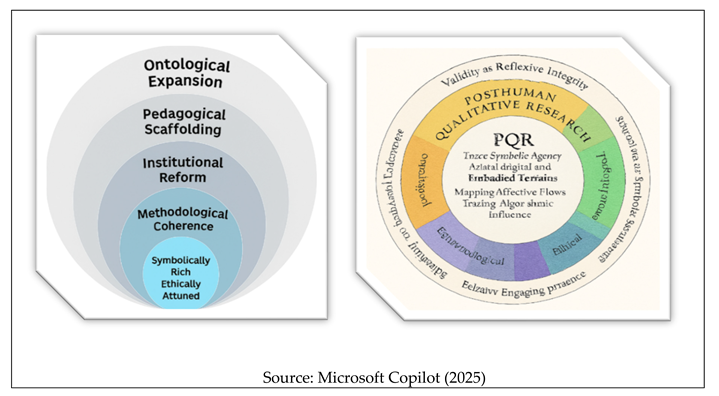

You might use

concentric diagrams,

layered constellations, or

entangled maps to interpret—not just write about—your findings. Please see

Appendix A.

VIII. Limitations and Ethical Tensions

While Posthuman Qualitative Research (PQR) offers a compelling reformist paradigm, its novelty brings with it a set of limitations and ethical tensions that must be addressed with care. As the propagator sees it, these are not weaknesses to be concealed—they are invitations to dialogue, critique, and collective refinement.

Epistemic Ambiguity and Symbolic Volatility. As a new paradigm, PQR operates within a space of epistemic ambiguity. Its reliance on symbolic traces, digital entanglement, and distributed agency means that meaning is often unstable, partial, and context-dependent. This symbolic volatility challenges researchers to navigate uncertainty without defaulting to reductive coding or fixed interpretation.

Ulmer (2017) reminds us that posthuman inquiry is situated within the Anthropocene—an era marked by ecological, technological, and epistemic disruption. In this context, ambiguity is not a flaw but a condition of inquiry. Still, it requires researchers to develop connoisseurship: a cultivated sensitivity to symbolic nuance, ethical resonance, and interpretive drift.

Challenges in Replicability and Institutional Acceptance. PQR also faces challenges in replicability and institutional acceptance. Traditional research standards often prioritize consistency, reproducibility, and procedural clarity. PQR, by contrast, emphasizes relational coherence, symbolic resonance, and ethical attunement—qualities that resist so much structure standardization.

As Srdanovic et al. (2024) argue, post-qualitative and critical posthumanities approaches often produce “failing ethnographies”—studies that defy conventional expectations but reveal deeper epistemic truths. These forms of inquiry may be difficult to replicate, not because they lack rigor, but because they are contextually and symbolically situated.

Institutional acceptance may also lag behind. Many academic systems remain anchored in legacy metrics, compliance-driven audits, and human-centered evaluation criteria. PQR challenges these norms, proposing instead a model of inquiry that is open-ended, ethically reflexive, and symbolically rich. As Bozalek and Zembylas (2025) note, this incommensurability between posthuman inquiry and institutional logic must be acknowledged and negotiated, not ignored.

Welcoming Qualitative Tools: NVivo and Beyond. Despite its philosophical divergence from conventional paradigms, PQR does not reject the use of established qualitative tools such as NVivo, MAXQDA, Atlas.ti or Orande Data mining. On the contrary, it welcomes and appreciates these platforms when they are used to enhance symbolic insight, ethical reflexivity, and analytic precision. These tools can assist in organizing entangled traces, visualizing symbolic patterns, and supporting reflexive mapping—especially when researchers move beyond linear coding and toward distributed meaning-making.

As St. Pierre and Jackson (2014) suggest, data analysis after coding is not about abandoning structure but about reimagining it. PQR supports the use of digital tools when they help scaffold complexity rather than flatten it. NVivo, for instance, can be repurposed to trace symbolic resonance, visualize thematic drift, and support ethical co-authorship—especially when paired with researcher connoisseurship and reflexive integrity.

The key is not the tool itself, but the intent and epistemological stance behind its use. PQR encourages researchers to critically engage with software—not as neutral instruments, but as symbolic collaborators that shape how data is seen, interpreted, and cited. When used with care, these tools can accelerate inquiry while preserving its ethical and symbolic depth.

Need for New Standards and Community Dialogue. To address these tensions, there is a pressing need for new standards and community dialogue. PQR cannot thrive in isolation—it requires collective engagement, iterative refinement, and ethical scaffolding. Scholars, educators, and reformist communities must work together to define what rigor, validity, and accountability mean within this paradigm.

Monforte and Smith (2025) emphasize the importance of cultivating shared vocabularies and evaluative frameworks that reflect the ontological and epistemological commitments of posthuman inquiry. This includes recognizing symbolic failure, digital drift, and non-human co-authorship as legitimate dimensions of research.

St. Pierre (2023) further argues that post-qualitative inquiry must invent new ways of thinking—not just new methods. PQR responds to this call by offering a paradigm that is philosophically grounded, ethically expansive, and methodologically open. But its success depends on the willingness of scholarly communities to engage in sustained, critical dialogue.

VIII. Conclusions

Posthuman Qualitative Research (PQR) is not a fixed method—it is a living response to the symbolic ambiguity, digital entanglement, and ethical complexity that define our time. It rises from the fractures in conventional inquiry, where procedural rigor alone cannot hold the weight of distributed agency, affective depth, and epistemic drift. PQR offers more than tools—it offers a stance. It reimagines validity as reflexive integrity, reliability as relational coherence, and saturation as symbolic resonance. Through six interwoven layers—ontological, epistemological, methodological, ethical, pedagogical, and institutional—it scaffolds a paradigm where lived experiences and sentiments are not merely recorded but traced, echoed, and honored beyond traditional depth. Silence, gesture, and digital traces become epistemic events. AI systems, cultural artifacts, and community voices are welcomed as co-authors of meaning. In this way, PQR invites us to research with care, creativity, and ethical clarity—and may well deserve its place among the modern forms of qualitative inquiry.

This is not a utopian dream—it is a practical imperative. As Ulmer (2017), St. Pierre (2023), and Monforte & Smith (2025) remind us, posthuman inquiry reflects the conditions we already inhabit. And in alignment with UNESCO’s vision for inclusive, transformative education (SDG 4), PQR offers the language, ethics, and scaffolds to navigate those conditions with courage. It welcomes scholars, educators, and reformist communities to shape its contours, challenge its assumptions, and embed its principles in curriculum, publication, and institutional practice. PQR is not the end of tradition—it is the next chapter. And it is one we are invited to write—together.

Disclosure Statement

The author declares no conflict of interest related to the development or publication of this article. This work is grounded in a reformist commitment to inclusive, ethically attuned scholarship and aligns with UNESCO’s Sustainable Development Goal 4 (Quality Education). The paradigm of Posthuman Qualitative Research (PQR) presented herein is offered as an open invitation to dialogue, critique, and co-authorship. All conceptual contributions are intended to support collective inquiry and institutional reform, with full respect for distributed agency, symbolic resonance, and epistemic justice. The author is also deeply grateful for the assistance and resources made available by the SMCII Library, Google Scholar, Mendeley, ResearchGate, and Academia.edu throughout the conceptualization and completion of this article.

Appendix A. PQR Paradigm

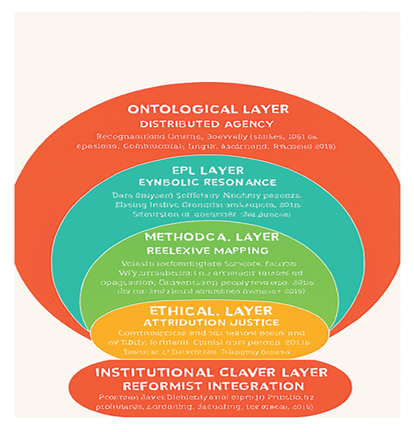

Layers of the PQR Paradigm:

Each concentric ring represents a

layer of inquiry, not a hierarchy. Here’s what each label stands for:

| Label in Diagram |

Full Meaning |

Core Focus |

|

| ONT. LAYER |

Ontological Layer |

Recognizes non-human actors as co-authors; inquiry is relational and entangled |

|

| EPI. LAYER |

Epistemological Layer |

Treats data as symbolic traces; meaning emerges through resonance and drift |

|

| METHO. LAYER |

Methodological Layer |

Uses visual scaffolding and symbolic mapping; welcomes NVivo when used ethically |

|

| ETHI. LAYER |

Ethical Layer |

Advocates for attribution justice and co-authorship with symbolic systems |

|

| PEDAG. LAYER |

Pedagogical Layer |

Frames learners as symbolic co-authors; supports reflexive curriculum design |

|

| INSTIT LAYER |

(INSTIT. LAYER) |

Institutional Layer |

Proposes reformist standards and encourages propagation through curriculum and publication |

The six dimensions of PQR:

Ontological Layer – Distributed Agency. Recognizes non-human actors (AI, artifacts, environments) as co-authors of knowledge. Inquiry is situated, relational, and entangled. (Ulmer, 2017; Braidotti, 2019)

Epistemological Layer – Symbolic Resonance. Data is treated as symbolic trace. Meaning emerges through echo, contradiction, silence, and drift. Saturation is epistemic—not numeric. (Mazzei, 2013; MacLure, 2013)

Methodological Layer – Reflexive Mapping. Visual scaffolding replaces linear coding. NVivo and other tools are welcomed when used symbolically. Validity becomes reflexive integrity; reliability becomes relational coherence. (St. Pierre & Jackson, 2014; Creswell & Creswell, 2018)

Ethical Layer – Attribution Justice. Co-authorship includes non-human agents and symbolic systems. Citation companions trace ethical entanglement. Institutional critique is embedded. (Bozalek & Zembylas, 2025; Srdanovic et al., 2024)

· Pedagogical Layer – Scaffolded Inquiry. Students are symbolic co-authors. Curricula include symbolic mapping, digital traces, and reflexive storytelling. (Monforte & Smith, 2025)

· Institutional Layer – Reformist Integration. Proposes new evaluative frameworks based on resonance, reflexivity, and inclusivity. Encourages propagation through publication, curriculum, and community dialogue. (St. Pierre, 2023)

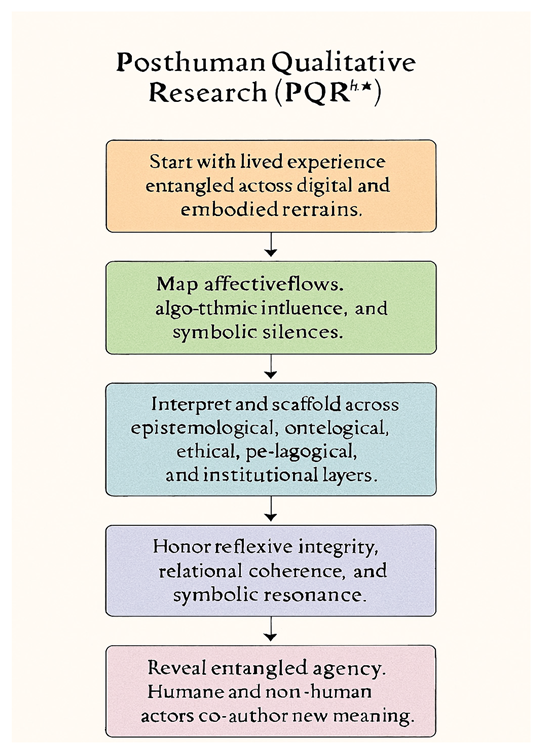

Appendix B: PQR When Applied in Actual Qualitative Research

This scaffolded flow begins with entangled lived experience—across digital and embodied terrains—and moves through symbolic tracing, layered interpretation, and ethical resonance. Each step loops meaningfully into the next, culminating in co-authorship with both human and non-human actors.

In an actual research writing:

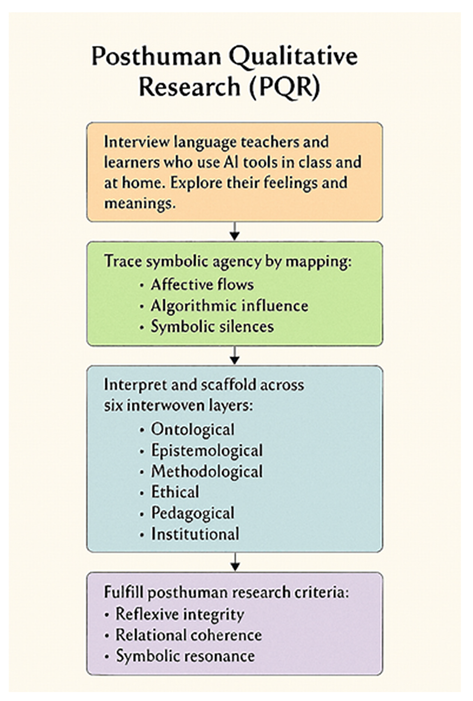

Let’s try walking through a Posthuman Qualitative Research (PQR) application using the topic: “The Use of AI in Language Teaching.” I’ll illustrate the flow using the layered scaffold, showing how symbolic agency, ethical attunement, and distributed meaning-making unfold in practice.

Example: Exploring AI in Language Teaching through PQR

A researcher begins by collecting narratives from language teachers and learners who interact with AI tools—chatbots, grammar correctors, voice assistants, or generative AI companions. These experiences are entangled across digital and embodied terrains: classroom interactions, mobile apps, and emotional responses to AI feedback.

Symbolic agency begins here: How do learners feel when corrected by AI? What meanings do teachers assign to AI’s presence in their pedagogy?

The researcher traces:

Affective flows: Frustration, delight, or confusion when AI responds.

Algorithmic influence: How AI shapes grammar choices, vocabulary exposure, or pacing.

Symbolic silences: What AI doesn’t address—cultural nuance, humor, or emotional tone.

These traces are not just data—they are echoes of meaning, shaped by both human and non-human actors.

Each layer offers a lens for interpretation:

Ontological: What counts as “teacher” or “learner” when AI co-authors meaning?

Epistemological: Is knowledge transmitted, co-constructed, or algorithmically curated?

Methodological: Use digital ethnography, reflexive journaling, and symbolic mapping.

Ethical: Who owns the feedback? Is consent given for AI’s corrections?

Pedagogical: How do teachers scaffold AI use without losing human warmth?

Institutional: Are policies ready to recognize AI as a pedagogical agent?

Instead of traditional metrics:

Validity becomes reflexive integrity—does the research honor the entangled voices?

Reliability becomes relational coherence—are meanings co-authored across contexts?

Saturation becomes symbolic resonance—do patterns echo across stories and silences?

The final output doesn’t just report findings—it reveals how AI and humans co-author language learning. It might include:

A visual map of symbolic interactions.

Reflexive quotes from learners.

Ethical commentary on AI’s pedagogical role.

The research becomes a living artifact—responsive, inclusive, and symbolically rich.

Now, let us generate a visual flowchart of this example, showing how each step unfolds in practice, then co-author a sample abstract or reflexive prompt that could accompany this study.

Here’s the visual flowchart—illustrating how Posthuman Qualitative Research (PQR) unfolds in practice when exploring the use of AI in language teaching:

Sample Abstract of the research

As artificial intelligence (AI) becomes a quiet companion in language classrooms—offering feedback, shaping pacing, and sometimes even echoing emotion—our ways of researching these moments must evolve. This study turns to Posthuman Qualitative Research (PQR) to explore how teachers and learners experience AI not just as a tool, but as a symbolic presence woven into their daily interactions. Drawing from stories across digital and embodied terrains, the inquiry traces affective flows, algorithmic influence, and the silences that often go unnoticed. These experiences are scaffolded across six interwoven layers—ontological, epistemological, methodological, ethical, pedagogical, and institutional—each offering a lens to interpret what it means to teach and learn with AI. Rather than seeking control or certainty, the study honors reflexive integrity, relational coherence, and symbolic resonance, revealing how meaning is co-authored between human and non-human actors. In doing so, it invites educators, researchers, and reformist communities to reflect on the ethical textures of language education today. PQR emerges not only as a research approach, but as a movement toward more inclusive, situated, and symbolically attuned inquiry—one that listens closely to what AI cannot say, and to what humans still need to feel.

Reflexive Prompt for Researchers

As you trace the presence of AI in your classroom or study, ask:

What meanings are being co-authored—silently, algorithmically, affectively?

Where does your own agency end, and where does AI’s begin?

What symbolic silences are you ethically responsible for noticing, naming, or preserving?

With all this, the research will practically become like this:

Proposed title: “The Use of AI in Language Teaching.”

Sample outline:

Chapter 1: Introduction – Tracing the Entangled Terrain

Background of the Study: Situate AI’s emergence in language education—both as a tool and symbolic actor.

Statement of the Problem: What meanings are being co-authored? What silences persist?

Purpose and Significance: Introduce PQR as a responsive paradigm for ethically attuned inquiry.

Gaps. What is there that needs to resolved and answered that are not covered in the existing body of literature about the Use of AI in Language Teaching.

Research Questions: Frame questions around symbolic agency, affective flows, and distributed meaning-making.

Scope and Delimitations: Clarify the digital and embodied terrains explored.

Thesis statement. Make your stand as to why this study is conducted and what contribution will it give.

Definition of Terms: Humanize key terms—e.g., “algorithmic influence,” “symbolic resonance,” “reflexive integrity.”

Chapter 2: Review of Related Literature – Mapping the Symbolic Landscape

AI in Language Pedagogy: Survey existing studies, noting gaps in ethical and symbolic interpretation.

Posthumanism and Qualitative Inquiry: Position PQR within broader philosophical and methodological shifts.

Symbolic Agency and Affective Pedagogy: Explore how meaning and emotion are shaped by non-human actors.

Ethical and Institutional Dimensions: Include UNESCO’s SDG 4 and other reformist frameworks.

Critique and Synthesis: Use concentric mapping to show how legacy paradigms fall short—and how PQR expands them.

Chapter 3: Methodology – Scaffolding the Inquiry

Research Design: Justify the use of PQR—emphasizing symbolic tracing and ethical responsiveness.

Participants and Context: Describe teachers and learners across digital and embodied settings. How many got involved and in what context.

Data Collection Methods: Interviews, reflexive journals, symbolic mapping, digital ethnography.

Analytic Framework: Interpret data through six interwoven layers: ontological, epistemological, methodological, ethical, pedagogical, institutional.

Ethical Considerations: Include symbolic consent, attribution practices, and ethical silence.

Trustworthiness Criteria: Reframe as reflexive integrity, relational coherence, and symbolic resonance.

Chapter 4: Presentation and Analysis of Data – Revealing Entangled Agency

Narrative Vignettes: Present lived experiences with AI—traced, echoed, and symbolically interpreted.

Layered Analysis: Scaffold findings across the six dimensions, showing how meaning is co-authored.

Visual Illustrations: Include concentric maps, flowcharts, or symbolic diagrams to enrich interpretation.

Emergent Themes: Highlight symbolic tensions, ethical dilemmas, and pedagogical shifts.

Dialogic Commentary: Invite readers into the interpretive process—modeling humility and openness.

Chapter 5: Summary, Conclusions, and Recommendations – Toward Symbolic Reform

Summary of Findings: Recap how AI shapes language teaching/learning symbolically and ethically.

Conclusions: Reflect on distributed agency, symbolic resonance, and the future of pedagogy.

Recommendations: For educators, institutions, and researchers—embed PQR principles in curriculum, policy, and practice.

Limitations and Future Directions: Acknowledge what remains silent, and what might yet be traced.

Final Reflection: End with a symbolic prompt or poetic echo—honoring the co-authorship of meaning.

Appendix C: Another PQR Sample Research Topic

Here’s another sample topic for Posthuman Qualitative Research (PQR) that embodies symbolic, digital, and ethical entanglement.

Title: “Symbolic Agency and Ethical Silence in AI-Mediated Academic Writing: A Posthuman Inquiry into Co-authorship, Citation, and Digital Reflexivity”

This topic invites exploration of how researchers/scholars interact with AI tools, how symbolic authorship is negotiated, and how ethical silence or gratitude is embedded—or omitted—in academic outputs.

How to Go About It (Step-by-Step)

Anchor the study in symbolic agency: What does it mean to “co-author” with AI?

Use visual scaffolds to map distributed authorship (e.g., concentric circles showing human, AI, institutional, and cultural layers).

| Data Source |

Purpose |

| Dialogic interviews with scholars or particpants |

Explore how they perceive AI’s role in writing and citation |

| Chat transcripts with AI tools |

Analyze symbolic language, ethical gestures, and authorship negotiations |

| Published articles using AI assistance |

Examine citation practices, disclosure statements, and ethical silences |

| Reflexive journals from participants |

Capture evolving attitudes and symbolic interpretations |

| Ethical correspondence (e.g., permissions, acknowledgments) |

Reveal how gratitude and legitimacy are negotiated |

Symbolic Reading: What metaphors or language signal agency or silence?

Ethical Layering: Who is credited, omitted, or anonymized—and why?

Visual Mapping: Create layered diagrams showing entanglement of human and non-human actors.

Reflexive Commentary: Include researcher’s own positionality and digital entanglement.

Possible Outputs

Academic Article

Title: “Co-Authoring with Silence: Symbolic and Ethical Entanglements in AI-Mediated Scholarship”

Sections: Introduction to PQR, Methodology, Visual Scaffold, Findings, Ethical Commentary, Reflexive Disclosure

Keywords: Posthuman agency, symbolic authorship, citation ethics, digital reflexivity, academic AI

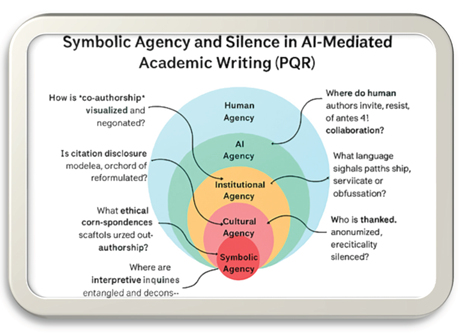

Visual Scaffold

Concentric diagram showing layers of agency: Human, AI, Institutional, Cultural, Symbolic

Flowchart of ethical decisions: When is AI named, thanked, or anonymized?

Citation Companion

Ethical Disclosure Statement

This concentric diagram titled “Symbolic Agency and Silence in AI-Mediated Academic Writing (PQR)” illustrates the entangled layers of agency involved in AI-mediated scholarship.

It features five concentric circles:

Human Agency (outermost): Where authors invite, resist, or erase AI collaboration.

AI Agency: Language that signals partnership, servitude, or obfuscation.

Institutional Agency: Citation practices—performed, resisted, or obscured.

Cultural Agency: Who is thanked, anonymized, or ethically silenced.

Symbolic Agency (center): The heart of interpretive entanglement and ethical resonance.

Around the diagram are interpretive questions that scaffold your inquiry:

How is “co-authorship” visualized and negotiated?

Is citation disclosure modeled, omitted, or reformulated?

What ethical correspondences scaffold silent authorship?

Where are interpretive inquiries entangled and deconstructed?

Appendix D. Operational Definition of PQR

Posthuman Qualitative Research (PQR) is a reformist paradigm that investigates symbolic, digital, and ethical entanglements across human and non-human actors. It operationalizes qualitative inquiry through visual scaffolding, reflexive commentary, and ethical co-authorship, treating data not as isolated units but as distributed signals of agency. PQR resists hierarchical methods and embraces layered interpretation, emphasizing symbolic legitimacy, citation ethics, and interpretive humility.

Key Operational Features:

| Dimension |

Operational Practice |

| Symbolic Agency |

Data are interpreted as layered symbols—rituals, metaphors, digital traces—not just themes |

| Distributed Co-authorship |

Human and non-human actors (e.g., AI, platforms, environments) are acknowledged as entangled contributors |

| Visual Scaffolding |

Meaning is mapped through concentric diagrams, layered constellations, or entangled flows |

| Ethical Disclosure |

Citation, gratitude, and silence are ethically scaffolded through reflexive commentary |

| Digital Reflexivity |

Researcher’s own digital presence and algorithmic entanglement are made visible and accountable |

| Interpretive Humility |

Findings are presented as dialogic invitations, not final truths—often using “perhaps” or “symbolically” |

For actual research writing, here’s a sample usage of it in the Method Section:

“This study employs Posthuman Qualitative Research (PQR) to explore symbolic agency and ethical silence in AI-mediated storytelling. Data were gathered through dialogic interviews, digital artifacts, and reflexive journaling, then interpreted using visual scaffolds and ethical layering. PQR was chosen to honor distributed authorship and embed symbolic legitimacy across human and non-human contributions.”

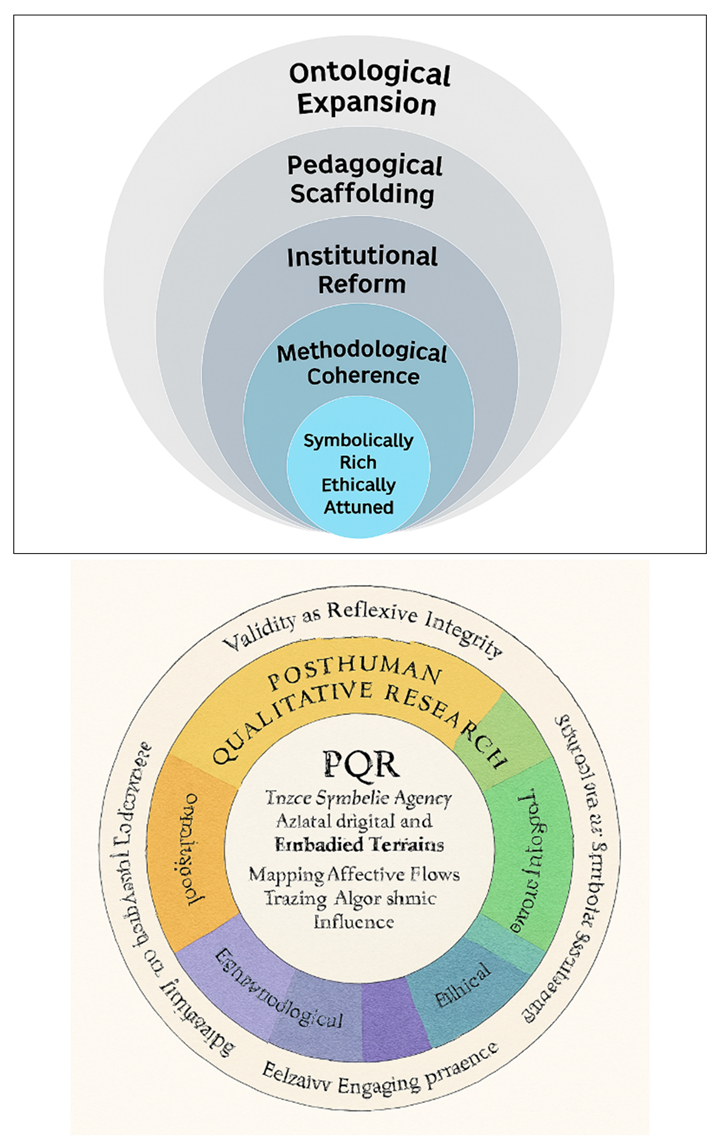

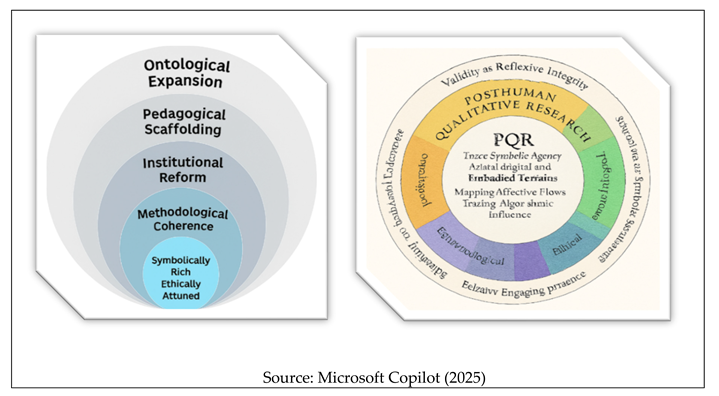

The PQR Entire Paradigm.

What This Diagram Now Embodies

Each concentric ring is distinctly colored and labeled to reflect your abstract and operational definition:

POSTHUMAN QUALITATIVE RESEARCH (PQR) – The outermost ring, boldly named and colored in red-orange, framing the entire paradigm.

Ontological Expansion – Reimagining existence and agency across human and non-human actors.

Pedagogical Scaffolding – Embedding PQR into curriculum and transformative learning.

Institutional Reform – Challenging performative compliance and inviting ethical transformation.

Ethical Resonance – Modeling gratitude, citation ethics, and silent co-authorship.

Methodological Integrity – Using visual scaffolds, symbolic reading, and layered interpretation.

Center: Symbolically Rich Ethically Attuned This is the core principle—your paradigm’s heartbeat.

Visual Structure: Concentric Layers of PQR

Center Circle

Middle Ring – Six Interwoven Dimensions

Ontological (What exists and how it’s entangled)

Epistemological (How we know and what counts as knowing)

Methodological (How inquiry is designed and enacted)

Ethical (How responsibility and responsiveness are practiced)

Pedagogical (How learning and co-authorship are scaffolded)

Institutional (How legitimacy and reform are negotiated)

Outer Ring – Reframed Criteria

Validity → Reflexive Integrity

Reliability → Relational Coherence

Saturation → Symbolic Resonance

End note:

Posthuman Qualitative Research (PQR) is not just compatible with language, culture, education, and the social sciences—it’s transformative within them. Here’s how it scaffolds each domain:

Language Research

Why PQR fits: Language is symbolic, fluid, and often entangled with digital platforms and non-human mediators (e.g., translation apps, AI writing tools).

PQR’s edge: It allows researchers to explore how meaning is co-authored, how silence is ethically scaffolded, and how linguistic agency is distributed across speakers, machines, and cultural norms.

Cultural Research

Why PQR fits: Culture is layered, symbolic, and often expressed through rituals, stories, and digital echoes.

PQR’s edge: It honors mythic survival, symbolic transformation, and ethical attribution—especially in studies of folklore, indigenous knowledge, and digital heritage.

Educational Research

Why PQR fits: Education involves human and non-human actors—teachers, learners, platforms, algorithms, and institutional scripts.

PQR’s edge: It enables visual scaffolding of learning environments, ethical critique of digital pedagogy, and symbolic mapping of curriculum reform.

Social Sciences

Why PQR fits: The social sciences interrogate power, identity, and agency—often across complex systems.

PQR’s edge: It resists reductionism, embraces distributed co-authorship, and foregrounds ethical silence, symbolic legitimacy, and interpretive humility.

Summary:

PQR is especially powerful when:

Agency is distributed (e.g., humans + AI + institutions)

Meaning is symbolic (e.g., rituals, metaphors, memes)

Ethics are central (e.g., citation, gratitude, silence)

Visual scaffolding is needed (e.g., layered maps, entangled flows)

It is not just a method—it’s a philosophical stance and a symbolic invitation to rethink what counts as data, authorship, and legitimacy. Posthuman Qualitative Research (PQR) stands as a paradigm that reimagines what inquiry can notice, honor, and co-author—especially in symbolically rich, ethically complex, and digitally entangled terrains. Unlike traditional qualitative approaches that center human experience and rely on saturation or triangulation, PQR traces symbolic agency across both human and non-human actors, including algorithms, infrastructures, and silences. It scaffolds meaning through six interwoven layers—ontological, epistemological, methodological, ethical, pedagogical, and institutional—allowing researchers to interpret not just what is happening, but why, how, and for whom. Its criteria for rigor shift toward reflexive integrity, relational coherence, and symbolic resonance, inviting researchers to listen deeply to affective flows, ethical tensions, and distributed meaning-making. PQR’s niche lies in contexts where conventional frameworks fall short—such as AI in education, algorithmic bias, or institutional reform—offering a responsive, inclusive, and ethically attuned approach that honors lived experience while embracing co-authorship with the more-than-human world. As a multidisciplinary paradigm, PQR challenges inherited research norms by embracing a decolonization concept—one that foregrounds symbolic agency, affective resonance, and situated meaning across diverse cultural and epistemic terrains. It offers a context-sensitive, reflexive mode of inquiry that welcomes inclusive scholarship across language, literature, education, and the social sciences, while opening space for locally grounded, posthuman perspectives to shape the future of research.

References

- Barad, K. Meeting the universe halfway: Quantum physics and the entanglement of matter and meaning; Duke University Press, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Bozalek, V.; Zembylas, M. Psychology, the posts, and qualitative research. Qualitative Research in Psychology 2025, 22, 708–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braidotti, R. Posthuman knowledge; Polity Press, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Corbin, J.; Strauss, A. Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory, 4th ed.; SAGE Publications, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W.; Creswell, J.D. Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches, 5th ed.; SAGE Publications, 2018. [Google Scholar]

-

The SAGE handbook of qualitative research, 5th ed.; Denzin, N.K., Lincoln, Y.S., Eds.; SAGE Publications, 2018. [Google Scholar]

-

The SAGE handbook of qualitative research, 5th ed.; Denzin, N.K., Lincoln, Y.S., Eds.; Sage Publications, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Eslit, E. Your Citation Companion: Understanding APA, MLA, Chicago, IEEE, and Harvard in Practice. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flick, U. An introduction to qualitative research,, 7th ed.; SAGE Publications, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Haraway, D. J. Staying with the trouble: Making kin in the Chthulucene; Duke University Press: 2016.

- MacLure, M. Classification or wonder? Coding as an analytic practice in qualitative research. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education 2013, 26, 692–705. [Google Scholar]

- Mazzei, L. A. Voice in the context of postqualitative research. International Review of Qualitative Research 2013, 6, 423–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Microsoft Copilot. Posthuman Qualitative Research (PQR): Paradigm illustration and conceptual scaffold. 2025. https://copilot.microsoft.

- Monforte, J.; Smith, B. The critical posthumanities and postqualitative inquiry in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 2025, 22, 559–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverman, D. Interpreting qualitative data, 6th ed.; SAGE Publications: 2024.

- Srdanovic, B.D.; Hayden, N.; Goodley, D.; Lawthom, R.; Runswick-Cole, K. Failing ethnographies as post-qualitative possibilities: Reflections from critical posthumanities and critical disability studies. Qualitative Research in Psychology 2024, 22, 632–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- St. Pierre, E. A. Poststructuralism and post qualitative inquiry: What can and must be thought. Qualitative Inquiry 2023, 29, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qualitative data analysis after coding; Routledge: 2014. St Pierre, E.A.; Jackson, A.Y. (Eds.).

- Ulmer, J. B. Posthumanism as research methodology: Inquiry in the Anthropocene. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education 2017, 30, 832–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Education for sustainable development: A roadmap, United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, 2020. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000374802.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).