Submitted:

25 September 2025

Posted:

25 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Background: Acquired brain injury (ABI) leads to cognitive, emotional, and social impairments that substantially affect quality of life. Although cortical lesions have traditionally received more attention, increasing evidence highlights the importance of the integrity of major white matter association tracts. However, few studies have simultaneously examined cognitive, affective, and social domains within a tractography framework.Methods: In this exploratory pilot study, ten ABI patients underwent diffusion-based tractography of the principal association tracts—the superior and inferior longitudinal fasciculi, the uncinate fasciculus, the inferior fronto-occipital fasciculus, and the cingulum—together with a comprehensive neuropsychological battery covering global cognition, executive functions, memory, emotional symptoms, and empathy. Results: Marked interindividual variability was observed in both tract profiles and neuropsychological outcomes. Findings revealed paradoxical associations, such as larger volumes of the left superior longitudinal fasciculus being linked to poorer cognitive performance, suggesting maladaptive reorganization. Hemispheric lateralization patterns were also identified, with the uncinate fasciculus showing differential contributions to immediate memory and working memory across hemispheres. Notably, empathy scores consistently correlated with volumes of the inferior longitudinal fasciculus, the uncinate fasciculus, and the cingulum, in line with recent evidence on the structural basis of socio-emotional outcomes after ABI. Conclusions: Although limited by sample size, this study provides novel evidence regarding the structure–function paradox, hemispheric specialization, and the clinical relevance of empathy in ABI. Overall, the results support the integration of tractography of the main association tracts with neuropsychological assessment as complementary tools to advance personalized neurorehabilitation.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Neuropsychological Assessment

- Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) [19]: a brief global cognition screener, sensitive to mild cognitive impairment, assessing multiple domains including attention, executive function, memory, language, and visuospatial abilities.

- Trail Making Test (TMT, Parts A and B) [20]: evaluates processing speed, visual attention, and cognitive flexibility. Part A requires sequencing numbers, while Part B assesses set-shifting between numbers and letters.

- Digit Span Forward and Backward (WAIS-III) [21]: measures attentional capacity, immediate memory, and working memory. The forward condition reflects attention span, while the backward condition indexes executive control and manipulation in working memory.

- Rey–Osterrieth Complex Figure Test (RCFT) [22]: only the copy task was administered, which evaluates visuoconstructive ability, perceptual organization, and planning strategies. Scoring considered both the global configuration and the details reproduced, yielding raw scores and percentile ranks.

- Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) [23]: a self-report instrument widely used for detecting anxiety and depressive symptoms in neurological populations.

- Cognitive and Affective Empathy Test (TECA) [24]: a validated Spanish instrument measuring empathy across four subscales, perspective taking, emotional understanding, empathic distress, and empathic joy, as well as a total empathy score.

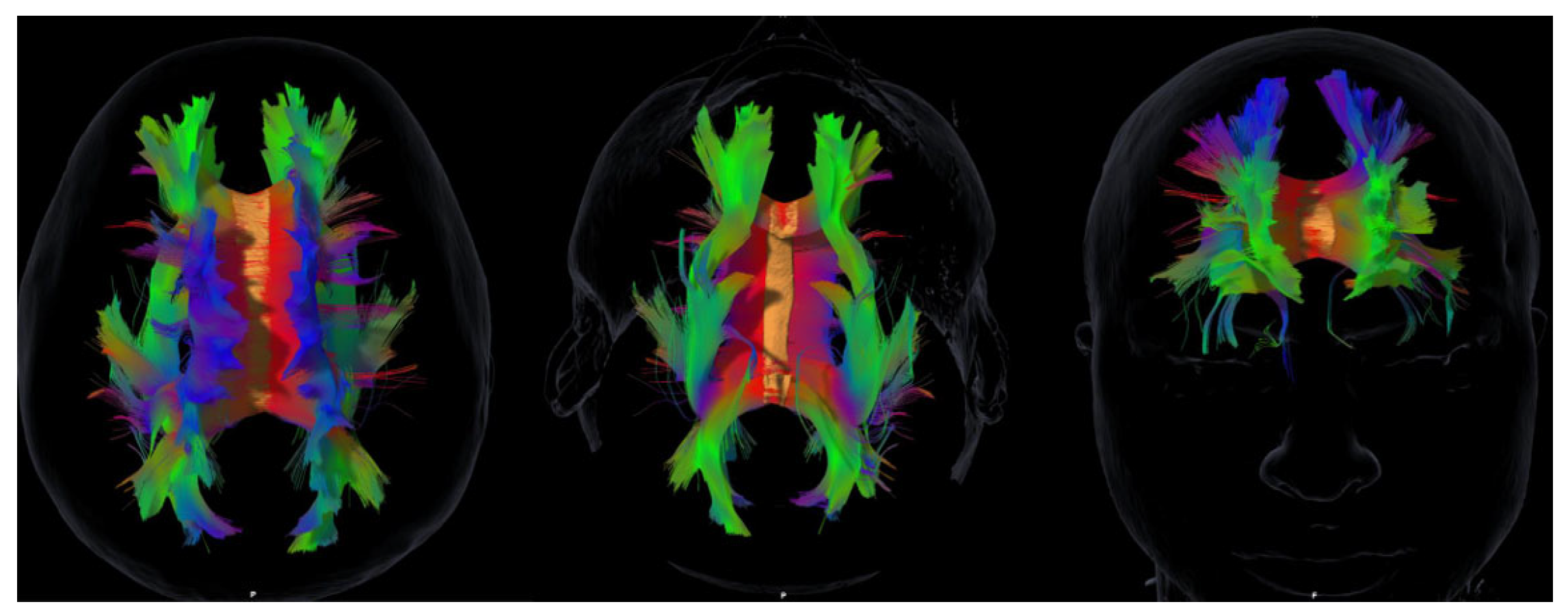

2.3. MRI Acquisition and Tractography

2.4. Statistical Analyses

2.5. Ethics

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

3.2. Neuropsychological Outcomes

3.3. White Matter Tract Volumes

3.4. Exploratory Tract–Behavior Associations

- SLF (left): negatively correlated with MoCA (ρ = –0.64, p = 0.046) and RCFT (ρ = –0.66, p = 0.039); positively correlated with slower TMT performance (ρ = 0.86, p = 0.001).

- UF (left): negatively correlated with Digit Span forward (ρ = –0.66, p = 0.038).

- UF (right): positively correlated with Digit Span backward (ρ = 0.68, p = 0.029).

- ILF (left): negatively correlated with total empathy scores (ρ = –0.66, p = 0.039).

- Cingulum (left): negatively correlated with empathic distress (ρ = –0.64, p = 0.046).

- IFOF (right): negatively correlated with empathic joy (ρ = –0.71, p = 0.022).

- No significant associations were observed for HADS scores.

- Age was negatively correlated with left cingulum volume (ρ = –0.73, p = 0.016).

3.5. Cluster and network analyses

- Cluster 1: marked cognitive impairment with preserved empathy.

- Cluster 2: mixed cognitive and affective deficits.

- Cluster 3: milder deficits but reduced empathy across domains.

4. Discussion

4.1. Structure–Function Paradox and Network Reorganization

4.2. Lateralization and Tract-Specific Contributions

4.3. Social Cognition and Empathy as Novel Contributions

4.4. Clinical Implications

4.5. Future Directions

4.6. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ABI | Acquired brain injury |

| Anx | Anxiety |

| Dep | Depression |

| DST | Digit Span Test |

| ED | Empathic distress |

| EJ | Empathic joy |

| EU | Emotional understanding |

| Fw | Forward (Digit Span) |

| HADS | Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale |

| ILF | Inferior longitudinal fasciculus |

| IFOF | Inferior fronto-occipital fasciculus |

| MoCA | Montreal Cognitive Assessment |

| PC | Percentile score |

| PT | Perspective taking |

| RCFT | Rey–Osterrieth Complex Figure Test |

| Rv | Reverse (Digit Span) |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| SFOF | Superior fronto-occipital fasciculus |

| SLF | Superior longitudinal fasciculus |

| TECA | Cognitive and Affective Empathy Test |

| TIPO | Total drawing performance-adjusted percentile score |

| TMT | Trail Making Test |

| UF | Uncinate fasciculus |

| WAIS | Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale |

| WM | White matter |

| ρ | Spearman’s correlation coefficient |

References

- Pulido ML. Neurocognitive outcomes in acquired brain injury. Rev Neurol. 2023;76(2):87–95.

- Njomboro P, Deb S, Humphreys GW. Social cognition deficits in traumatic brain injury: a clinical perspective. Brain Inj. 2014;28(9):1146–51. [CrossRef]

- Filley CM, Fields RD. White matter and cognition: making the connection. J Neurophysiol. 2016;116(5):2093–104. [CrossRef]

- Forkel SJ, Thiebaut de Schotten M, Kawadler JM, Dell’Acqua F, Danek A, Catani M. Disconnection and dysfunction in the human brain: from lesions to networks. Brain. 2021;144(1):3–20. [CrossRef]

- Chin R, Chang SWC, Holmes AJ. Beyond cortex: the evolution of the human brain. Psychol Rev. 2023;130(2):285–307. [CrossRef]

- Armstrong E. Precision connectomics: mapping and predicting brain networks in health and disease. Trends Neurosci. 2024;47(2):123–36. [CrossRef]

- Cai W, Chen T, Ryali S, Kochalka J, Li CS, Menon V. AI-driven tractography pipelines for massively parallel reconstruction. Neuroinformatics. 2024;22(3):445–60. [CrossRef]

- Orenuga O, Ogunyemi O, Bamisile O, Koshy S. Traumatic brain injury and artificial intelligence: shaping the future of neurorehabilitation—A review. Life. 2025;15(3):424. [CrossRef]

- Newcombe VF, Correia MM, Ledig C, Abate MG, Outtrim JG, Chatfield D, et al. Dynamic changes in white matter abnormalities correlate with late improvement and deterioration following traumatic brain injury: a diffusion tensor imaging study. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2016;30(1):49–62. [CrossRef]

- He X, Xu W, Zhang Q, Wang J, Zhang M. Cingulum bundle microstructure predicts affective regulation after brain injury. Hum Brain Mapp. 2021;42(18):6045–58. [CrossRef]

- Voelbel GT, Genova HM, Chiaravalloti ND, Hoptman MJ. Diffusion tensor imaging of traumatic brain injury review: implications for neurorehabilitation. NeuroRehabilitation. 2012;31(3):281–93. [CrossRef]

- Conner AK, Briggs RG, Rahimi M, Sali G, Baker CM, Burks JD, et al. A connectomic atlas of the human superior longitudinal fasciculus. Oper Neurosurg (Hagerstown). 2018;15(Suppl 1):S407–14. [CrossRef]

- Von der Heide RJ, Skipper LM, Klobusicky E, Olson IR. Dissecting the uncinate fasciculus: disorders, controversies and a hypothesis. Brain. 2013;136(6):1692–707. [CrossRef]

- Comes-Fayos J, García-García I, Peña-Casanova J. Role of association tracts in socio-emotional integration. Rev Neurol. 2018;67(7):263–72.

- Takahashi M, Iwamoto K, Fukatsu H, Naganawa S, Iidaka T, Ozaki N. White matter microstructure of the cingulum and cerebellar peduncle is related to sustained attention and working memory. Neurosci Lett. 2010;477(2):72–6. [CrossRef]

- Catani M, Dell’Acqua F, Thiebaut de Schotten M. A revised limbic system model for memory, emotion and behaviour. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2020;103:19–31. [CrossRef]

- Krick S, Koob JL, Latarnik S, Volz LJ, Fink GR, Grefkes C, et al. Neuroanatomy of post-stroke depression: association between symptom clusters and lesion location. Brain Commun. 2023;5(5):fcad275. [CrossRef]

- Bartolomeo P, Thiebaut de Schotten M. Let thy left brain know what thy right brain doeth: inter-hemispheric compensation of functional deficits after brain damage. Neuropsychologia. 2016;93(Pt B):407–12. [CrossRef]

- Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bédirian V, Charbonneau S, Whitehead V, Collin I, et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA): a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(4):695–9. [CrossRef]

- Reitan RM. Validity of the Trail Making Test as an indicator of organic brain damage. Percept Mot Skills. 1958;8:271–6. [CrossRef]

- Wechsler D. WAIS-III: Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale. 3rd ed. San Antonio: Psychological Corporation; 1997.

- Rey A. L’examen clinique en psychologie. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France; 1964.

- Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67(6):361–70. [CrossRef]

- López-Pérez B, Fernández-Pinto I, Abad FJ. TECA: Test de Empatía Cognitiva y Afectiva. Madrid: TEA Ediciones; 2008.

- Mori S, van Zijl PC. Fiber tracking: principles and strategies—a technical review. NMR Biomed. 2002;15(7–8):468–80. [CrossRef]

- Forkel SJ, Friedrich P, Thiebaut de Schotten M, Howells H. Is the “superior fronto-occipital fasciculus” really there in humans? Reproducibility, reliability and controversies in diffusion tractography. Neuroimage Clin. 2020;27:102192. [CrossRef]

- Ressel V, O’Gorman Tuura R, Scheer I, van Hedel HJ. Diffusion tensor imaging predicts motor outcome in children with acquired brain injury. Brain Imaging Behav. 2017;11(5):1373–84. [CrossRef]

- Lennartsson F, Holmström L, Eliasson AC, Flodmark O, Forssberg H, Tournier JD, et al. Advanced fiber tracking in early acquired brain injury causing cerebral palsy. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2015;36(1):181–7. [CrossRef]

- Pilipović K. Traumatic brain injury: novel experimental approaches. Life. 2025;15(6):884. [CrossRef]

| N=10 | ||

| Mean age (range) | 51.1 (29-63) | |

| Proportion of women | 60% | |

| Social Cognition, Cognitive Functions, And Emotional Outcomes | ||

| Montreal Cognitive Assessment test. Mean score (SD) | 21.9 (3.03) | |

| Digit Span Test. Mean score (SD) | Forward | 5.4 (1.6) |

| Reverse | 3.6 (0.7) | |

| Trail Making Test. Mean time, seconds (SD) | Part A | 51.3 (28.6) |

| Part B | 147.5 (173.3) | |

| Rey Complex Figure Test. Mean score (SD) | Type | 42.0 (26.5) |

| Percentile (PC) | 60.0 (25.8) | |

| Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Mean score (SD) | Depression | 8.9 (5.2) |

| Anxiety | 10.6 (4.3) | |

| Empathy Test. Mean score (SD) | Total | 38.8 (32.4) |

| Perspective taking | 33.5 (27.7) | |

| Emotional understanding | 30.1 (24.4) | |

| Empathic distress | 43.1 (31.4) | |

| Empathic joy | 33.7 (25.6) | |

| Volumes of Association Tracts | Mean volume mm3 (SD) | |

| Fronto-occipital | Right superior | 501.8 (100.9) |

| Left superior | 518.8 (89.7) | |

| Right inferior | 525.5 (60.8) | |

| Left inferior | 524.5 (66.2) | |

| Uncinate fasciculus | Right | 392.6 (130.6) |

| Left | 400.8 (142.3) | |

| Longitudinal fasciculus | Right superior | 425.2 (111.9) |

| Left superior | 418.2 (85.7) | |

| Right inferior | 515.2 (78.4) | |

| Left inferior | 496.4 (76.9) | |

| Cingulum | Right | 461.7 (71.8) |

| Left | 495.8 (88.7) | |

| Tract/Test | MoCA | DST | TMT | RCFT | HADS | TECA | ||||||||

| Fw | Rv | Part A | Part B | TIPO | PC | Dep | Anx | Total | PT | EU | ED | EJ | ||

| Right superior fronto-occipital | -0.13 (0.724) | 0.06 (0.862) | 0.09 (0.811) | -0.18 (0.629) | -0.16 (0.663) | -0.09 (0.797) | 0.11 (0.772) | -0.37 (0.287) | -0.1 (0.776) | -0.08 (0.827) | -0.23 (0.521) | -0.14 (0.699) | -0.61 (0.064) | 0.00 (1.00) |

| Left superior fronto-occipital | -0.28 (0.431) | 0.02 (0.958) | 0.24 (0.502) | 0.30 (0.399) | 0.46 (0.179) | -0.38 (0.285) | -0.29 (0.413) | -0.12 (0.748) | -0.09 (0.815) | -0.40 (0.254) | -0.38 (0.275) | -0.07 (0.854) | -0.32 (0.370) | -0.26 (0.476) |

| Right inferior fronto-occipital | 0.10 (0.787) | -0.53 (0.112) | 0.19 (0.589) | 0.27 (0.457) | 0.05 (0.894) | 0.09 (0.796) | 0.32 (0.371) | 0.09 (0.813) | 0.03 (0.940) | -0.20 (0.586) | 0.14 (0.693) | -0.37 (0.293) | -0.06 (0.866) | -0.71 (0.022) |

| Left inferior fronto-occipital | 0.23 (0.528) | -0.39 (0.268) | -0.07 (0.846) | 0.44 (0.208) | 0.29 (0.422) | -0.19 (0.603) | 0.13 (0.719) | -0.06 (0.866) | -0.26 (0.463) | -0.33 (0.358) | 0.30 (0.397) | -0.30 (0.400) | -0.03 (0.940) | -0.54 (0.105) |

| Right uncinate fasciculus | 0.43 (0.217) | -0.15 (0.688) | 0.68 (0.029) | -0.35 (0.321) | -0.38 (0.275) | 0.03 (0.932) | 0.29 (0.413) | -0.03 (0.933) | 0.05 (0.894) | 0.01 (0.987) | 0.29 (0.413) | -0.24 (0.508) | -0.24 (0.507) | -0.69 (0.028) |

| Left uncinate fasciculus | 0.36 (0.306) | -0.66 (0.038) | 0.60 (0.069) | -0.19 (0.592) | -0.25 (0.487) | 0.34 (0.331) | 0.55 (0.097) | 0.30 (0.399) | 0.16 (0.662) | -0.15 (0.672) | 0.20 (0.578) | -0.48 (0.165) | -0.28 (0.441) | -0.66 (0.037) |

| Right superior longitudinal fasciculus | -0.31 (0.390) | -0.10 (0.781) | -0.18 (0.617) | 0.58 (0.078) | 0.18 (0.614) | -0.47 (0.172) | -0.28 (0.434) | -0.01 (0.987) | 0.26 (0.464) | 0.07 (0.853) | 0.07 (0.841) | 0.16 (0.662) | 0.03 (0.933) | -0.24 (0.498) |

| Left superior longitudinal fasciculus | -0.64 (0.046) | -0.03 (0.944) | -0.44 (0.205) | 0.86 (0.001) | 0.72 (0.020) | -0.55 (0.099) | -0.66 (0.039) | 0.15 (0.670) | 0.19 (0.599) | 0.06 (0.865) | -0.15 (0.679) | 0.41 (0.238) | 0.29 (0.412) | 0.13 (0.711) |

| Right inferior longitudinal fasciculus | 0.57 (0.082) | 0.49 (0.147) | 0.44 (0.201) | -0.49 (0.147) | -0.32 (0.374) | -0.34 (0.331) | -0.4 (0.247) | 0.47 (0.168) | 0.47 (0.171) | 0.08 (0.827) | 0.22 (0.544) | 0.23 (0.531) | 0.49 (0.151) | 0.23 (0.521) |

| Left inferior longitudinal fasciculus | 0.39 (0.263) | 0.15 (0.688) | 0.42 (0.224) | 0.13 (0.731) | 0.34 (0.336) | -0.22 (0.544) | -0.16 (0.668) | 0.06 (0.880) | -0.22 (0.542) | -0.66 (0.039) | -0.06 (0.868) | -0.28 (0.432) | 0.29 (0.410) | -0.58 (0.077) |

| Right cingulum | 0.02 (0.946) | -0.48 (0.162) | 0.66 (0.039) | -0.14 (0.703) | 0.06 (0.873) | 0.38 (0.282) | 0.18 (0.616) | 0.60 (0.067) | 0.34 (0.331) | -0.06 (0.865) | -0.11 (0.756) | -0.16 (0.666) | 0.03 (0.926) | -0.35 (0.328) |

| Left cingulum | -0.23 (0.523) | -0.28 (0.429) | 0.46 (0.177) | 0.03 (0.938) | -0.10 (0.776) | 0.09 (0.796) | 0.11 (0.771) | 0.15 (0.671) | 0.24 (0.513) | 0.16 (0.659) | 0.07 (0.847) | 0.24 (0.507) | -0.64 (0.046) | -0.09 (0.815) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).