Submitted:

08 December 2025

Posted:

11 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Transcriptome-Wide Association Study (TWAS)

2.2. Linkage Disequilibrium Analysis

2.3. Postmortem Expression Analysis (BrainSeq)

2.4. Developmental Expression Trajectories (BrainSpan)

2.5. UCSC Genome Browser Validation

2.6. Functional Predictions (lncHUB)

3. Results

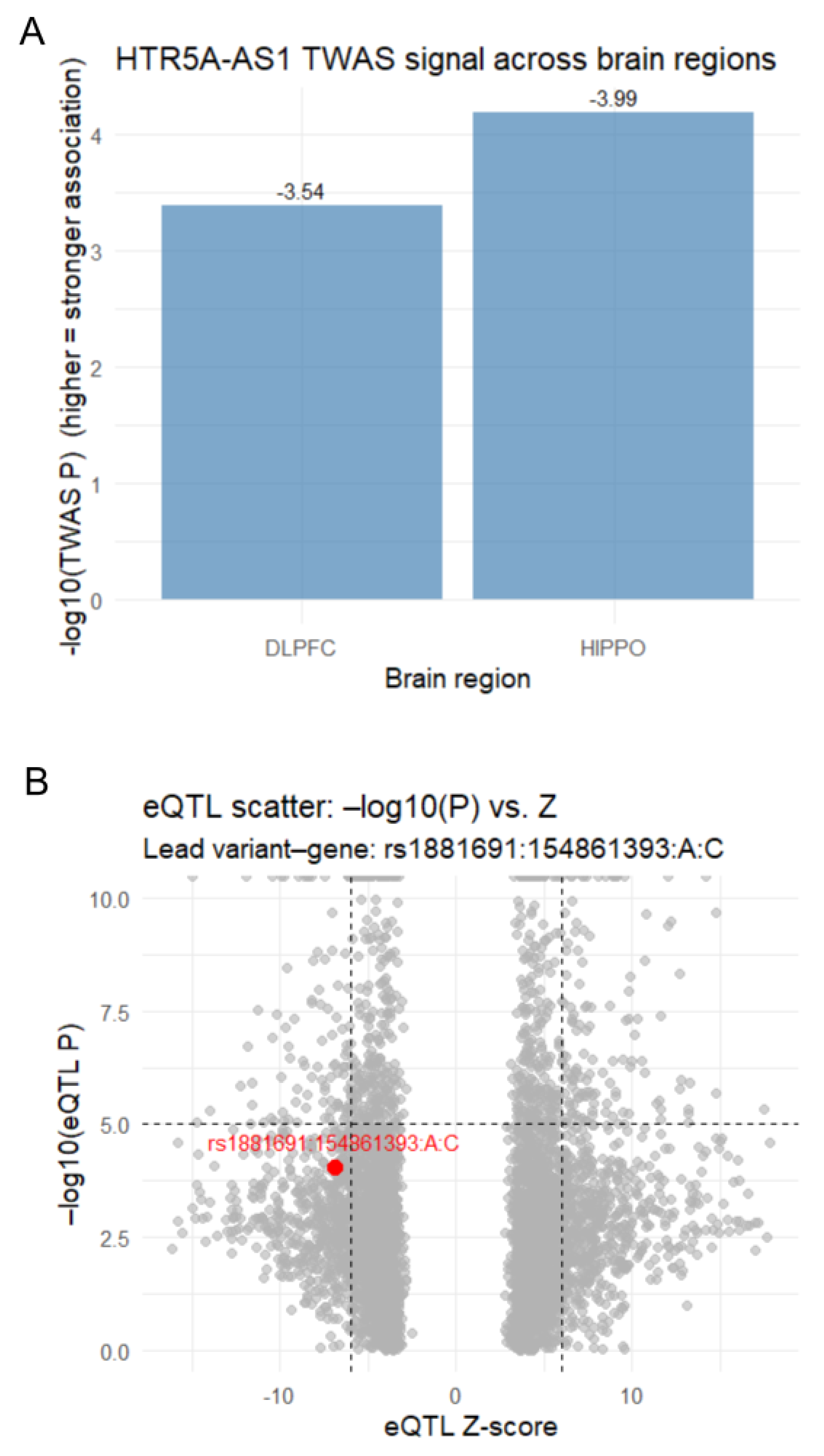

3.1. TWAS Identifies HTR5A-AS1 Association with Schizophrenia

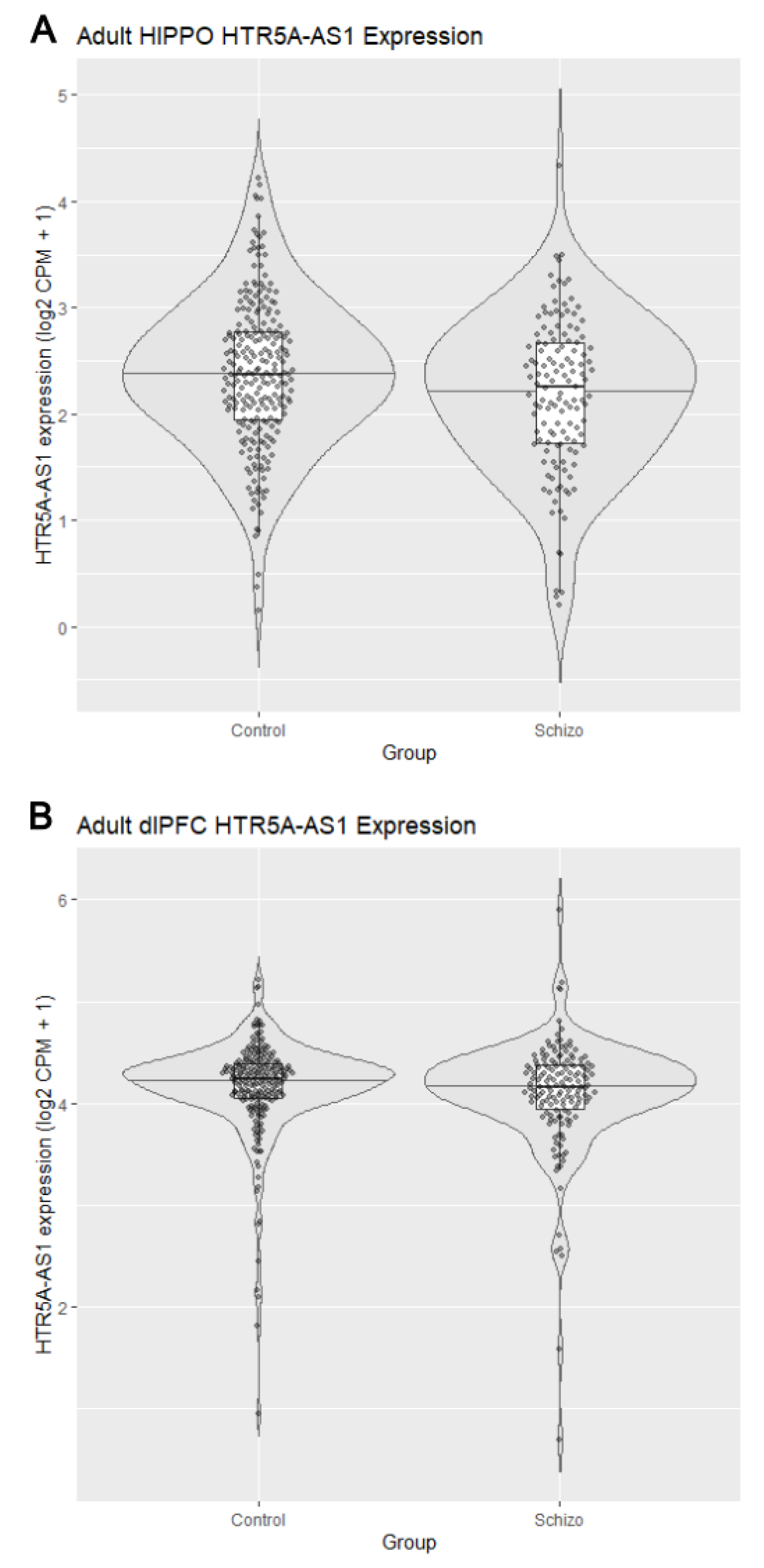

3.2. Reduced HTR5A-AS1 Expression in the Hippocampus

3.3. Sex-Stratified Postmortem Expression of HTR5A-AS1 and HTR5A

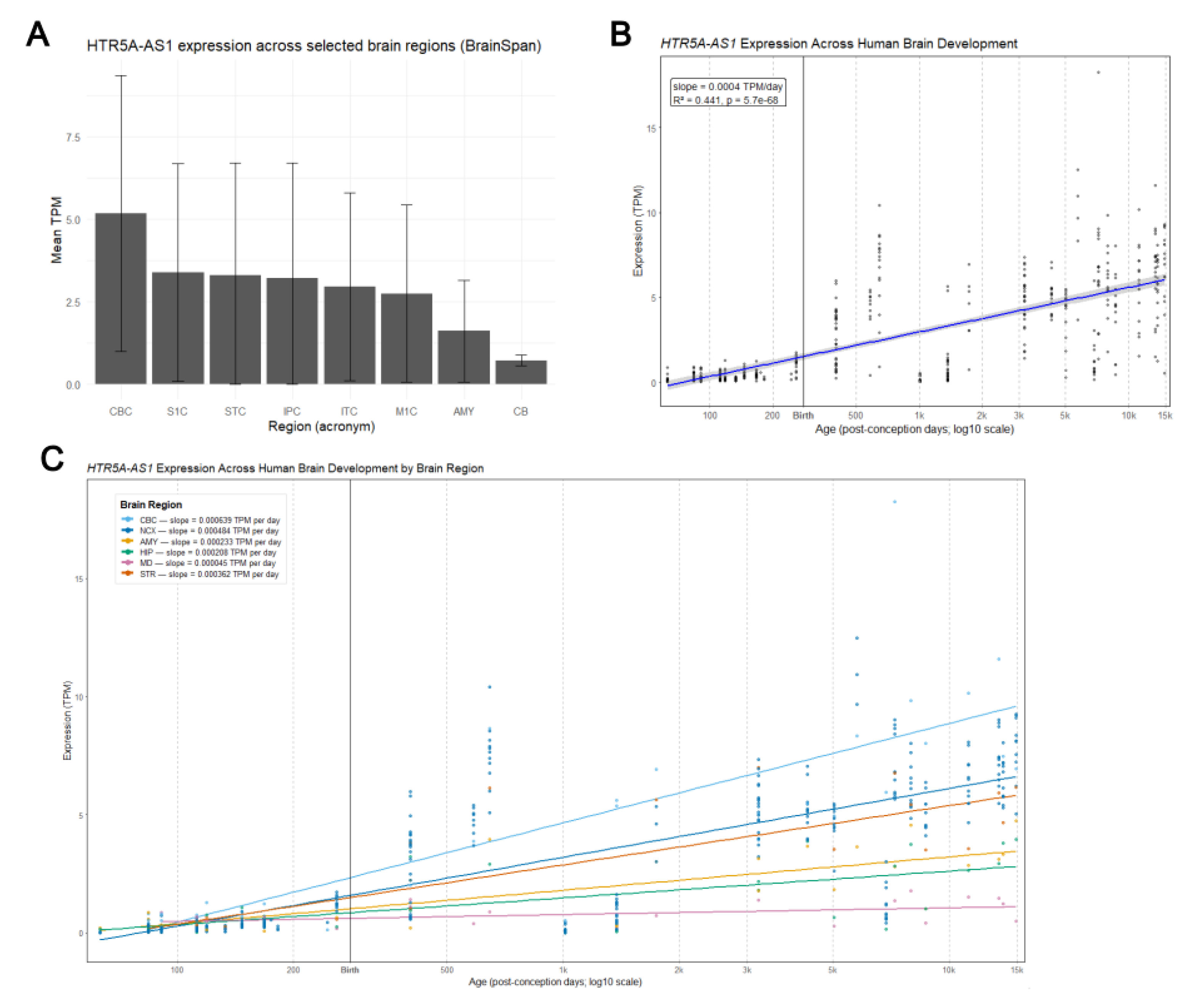

3.4. Region-Specific Expression in the Human Brain

3.5. Developmental Trajectory of HTR5A-AS1

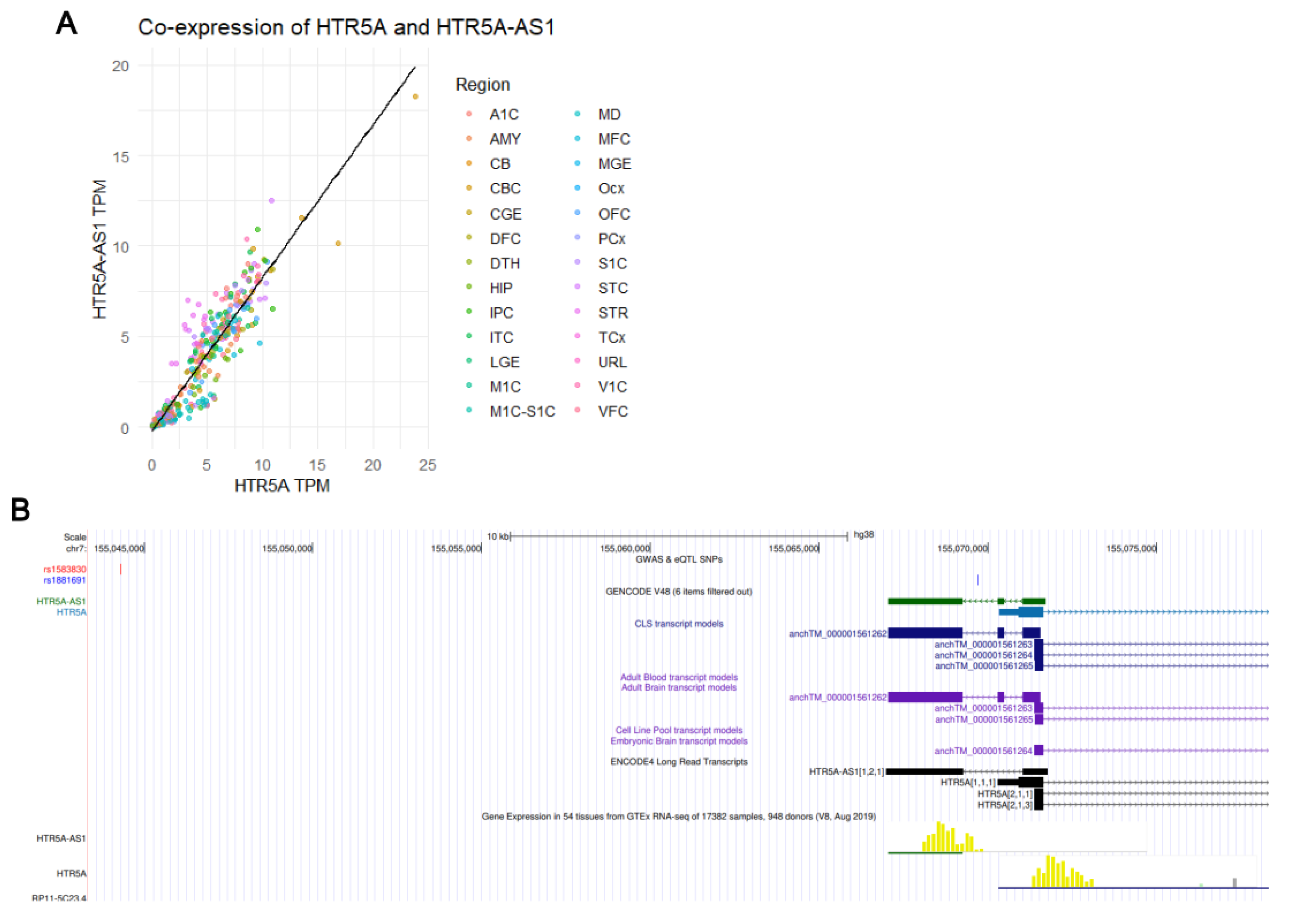

3.6. Transcript Validation via UCSC Genome Browser and Co-Expression Analysis

3.7. Predicted Functional Associations of HTR5A-AS1

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

References

- World Health Organization. Schizophrenia. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/schizophrenia, 2025. Accessed: 2025-09-08.

- Solmi, M.; Seitidis, G.; Mavridis, D.; Correll, C.U.; Dragioti, E.; Guimond, S.; Tuominen, L.; Dargél, A.; Carvalho, A.F.; Fornaro, M.; et al. Incidence, Prevalence, and Global Burden of Schizophrenia—Data, with Critical Appraisal, from the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) 2019. Molecular Psychiatry 2023, 28, 5319–5327. [CrossRef]

- Hany, M.; Rizvi, A. Schizophrenia; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025.

- Marder, S.R.; Cannon, T.D. Schizophrenia. New England Journal of Medicine 2019. [CrossRef]

- Chick, S.L.; Holmans, P.; Cameron, D.; Grozeva, D.; Sims, R.; Williams, J.; Bray, N.J.; Owen, M.J.; O’Donovan, M.C.; Walters, J.T.R.; et al. Whole-Exome Sequencing Analysis Identifies Risk Genes for Schizophrenia. Nature Communications 2025, 16, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Huo, Y.; Li, S.; Liu, J.; Li, X.; Luo, X.J. Functional genomics reveal gene regulatory mechanisms underlying schizophrenia risk. Nature Communications 2019, 10, 670. [CrossRef]

- Birnbaum, R.; Weinberger, D.R. Genetic Insights into the Neurodevelopmental Origins of Schizophrenia. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 2017, 18, 727–740. [CrossRef]

- Karlsgodt, K.H.; Sun, D.; Cannon, T.D. Structural and Functional Brain Abnormalities in Schizophrenia. Current Directions in Psychological Science 2010, 19, 226–231. [CrossRef]

- Quednow, B.B.; Geyer, M.A.; Halberstadt, A.L. Serotonin and Schizophrenia. In Handbook of Behavioral Neuroscience; Müller, C.P.; Cunningham, K.A., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; Vol. 31, pp. 711–743. [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Snyder, G.L.; Vanover, K.E. Dopamine Targeting Drugs for the Treatment of Schizophrenia: Past, Present and Future. Current Topics in Medicinal Chemistry 2016, 16, 3385–3403. [CrossRef]

- Meltzer, H.Y.; Li, Z.; Kaneda, Y.; Ichikawa, J. Serotonin Receptors: Their Key Role in Drugs to Treat Schizophrenia. Progress in Neuropsychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry 2003, 27, 1159–1172. [CrossRef]

- Grubor, M.; Zivkovic, M.; Sagud, M.; Nikolac Perkovic, M.; Mihaljevic-Peles, A.; Pivac, N.; Muck-Seler, D.; Svob Strac, D. HTR1A, HTR1B, HTR2A, HTR2C and HTR6 Gene Polymorphisms and Extrapyramidal Side Effects in Haloperidol-Treated Patients with Schizophrenia. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2020, 21. [CrossRef]

- Thomas, D.R. 5-HT5A Receptors as a Therapeutic Target. Pharmacology & Therapeutics 2006, 111, 707–714. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Smith, E.M.; Baye, T.M.; Eckert, J.V.; Abraham, L.J.; Moses, E.K.; Kissebah, A.H.; Martin, L.J.; Olivier, M. Serotonin (5-HT) Receptor 5A Sequence Variants Affect Human Plasma Triglyceride Levels. Physiological Genomics 2010, 42, 168–176. [CrossRef]

- Gusev, A.; Ko, A.; Shi, H.; Bhatia, G.; Chung, W.; Penninx, B.W.J.H.; Jansen, R.; de Geus, E.J.; Boomsma, D.I.; Wright, F.A.; et al. Integrative Approaches for Large-Scale Transcriptome-Wide Association Studies. Nature Genetics 2016, 48, 245–252. [CrossRef]

- Collado-Torres, L.; Burke, E.E.; Peterson, A.; Shin, J.; Straub, R.E.; Rajpurohit, A.; Semick, S.A.; Ulrich, W.S.; Price, A.J.; Valencia, C.; et al. Regional Heterogeneity in Gene Expression, Regulation, and Coherence in the Frontal Cortex and Hippocampus across Development and Schizophrenia. Neuron 2019, 103, 203–216.e8. [CrossRef]

- National Center for Biotechnology Information. NCBI Homepage. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/, 2025. Accessed: 2025-09-17.

- GeneCards. GeneCards. https://www.genecards.org/, 2025. Accessed: 2025-09-17.

- R Core Team. R: The R Project for Statistical Computing. https://www.r-project.org/, 2025. Accessed: 2025-09-17.

- CRAN. readr: Read Rectangular Text Data. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=readr, 2025. Accessed: 2025-09-17.

- CRAN. dplyr: A Grammar of Data Manipulation. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=dplyr, 2025. Accessed: 2025-09-17.

- Wickham, H. ggplot2; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016. [CrossRef]

- CRAN. stringr: Simple, Consistent Wrappers for Common String Operations. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=stringr, 2025. Accessed: 2025-09-17.

- Myers, T.A.; Chanock, S.J.; Machiela, M.J. LDlinkR: An R Package for Rapidly Calculating Linkage Disequilibrium Statistics in Diverse Populations. Frontiers in Genetics 2020, 11, 157. [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.H.; Thakur, R.; Machiela, M.J. LDexpress: An Online Tool for Integrating Population-Specific Linkage Disequilibrium Patterns with Tissue-Specific Expression Data. BMC Bioinformatics 2021, 22, 608. [CrossRef]

- Bioconductor. SummarizedExperiment: Summarized Experiment Container. https://bioconductor.org/packages/SummarizedExperiment, 2025. Accessed: 2025-09-17.

- CRAN. forcats: Tools for Working with Categorical Variables (Factors). https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=forcats, 2025. Accessed: 2025-09-17.

- CRAN. ggbeeswarm: Categorical Scatter (Violin Point) Plots. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=ggbeeswarm, 2025. Accessed: 2025-09-17.

- CRAN. broom: Convert Statistical Objects into Tidy Tibbles. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=broom, 2025. Accessed: 2025-09-17.

- UCSC Genome Browser. UCSC Genome Browser. https://genome.ucsc.edu/, 2025. Accessed: 2025-09-17.

- lncHUB. lncHUB. https://maayanlab.cloud/lnchub/, 2025. Accessed: 2025-09-17.

- CRAN. tibble: Simple Data Frames. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=tibble, 2025. Accessed: 2025-09-17.

- CRAN. rlang: Functions for Base Types and Core R and Tidyverse Features. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=rlang, 2025. Accessed: 2025-09-17.

- R Core Team. grid: The Grid Graphics Package. https://stat.ethz.ch/R-manual/R-devel/library/grid/doc/grid.pdf, 2025. Accessed: 2025-09-17.

- Groves, N.J.; Kesby, J.P.; Eyles, D.W.; McGrath, J.J. Misconceptions about serotonin receptors: the case for sex differences in the human serotonergic system. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2013, 40, 123–139. [CrossRef]

- BrainSpan Atlas of the Developing Human Brain. BrainSpan. https://www.brainspan.org/, 2025. Accessed: 2025-09-08.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).