Submitted:

21 September 2025

Posted:

25 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

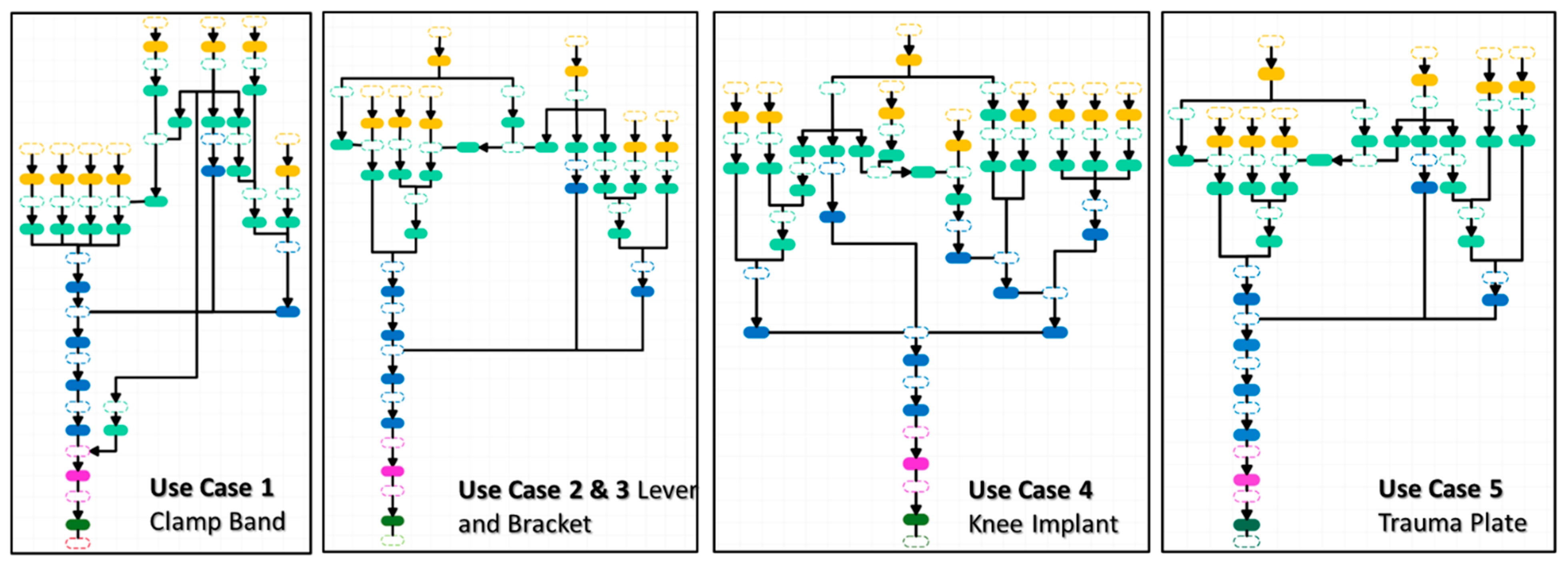

2.1. Use Cases Description

- Product function: The clamp band serves as a separation system for medium and large-sized commercial telecommunication satellites on the Ariane rocket. It enables satellites to attach to the rocket and separate precisely during the flight.

| Material (Aluminium 7075) |

Mass (%) |

|---|---|

| Al | 89.0 - 91.6 |

| Cu | 1.2 – 2.0 |

| Mg | 2.1 – 2.9 |

| Zn | 5.1 – 6.1 |

| Others < 1% | Fe (max 0.5), Mn (max 0.3), Si (max 0.4), Ti (max 0.2), Cr (0.18 – 0.28) |

- Product functions: The pivot bracket provides a fixed point, and the lever acts as the moving component in an actuator within the A350 belly fairing. This actuator controls the angle of attack of the NACA profile inside the engine nozzle, which modulates thrust, exhaust expulsion, and mass flow rate.

- The main material composition of the pivot bracket and lever consists of titanium (Ti), aluminium (Al), and vanadium (V), with trace elements such as iron (Fe) and carbon (C) illustrated in Table 2..

| Material (Ti6Al4V) |

Mass (%) |

|---|---|

| Ti | 91.0 |

| Al | 5.5 |

| V | 3.5 |

| Others < 1% | Fe (< 0.3), O (<0.2), H (<0.0015), C (<0.08), N (<0.05) |

- Product function: This unicompartmental knee implant component restores knee joint movement.

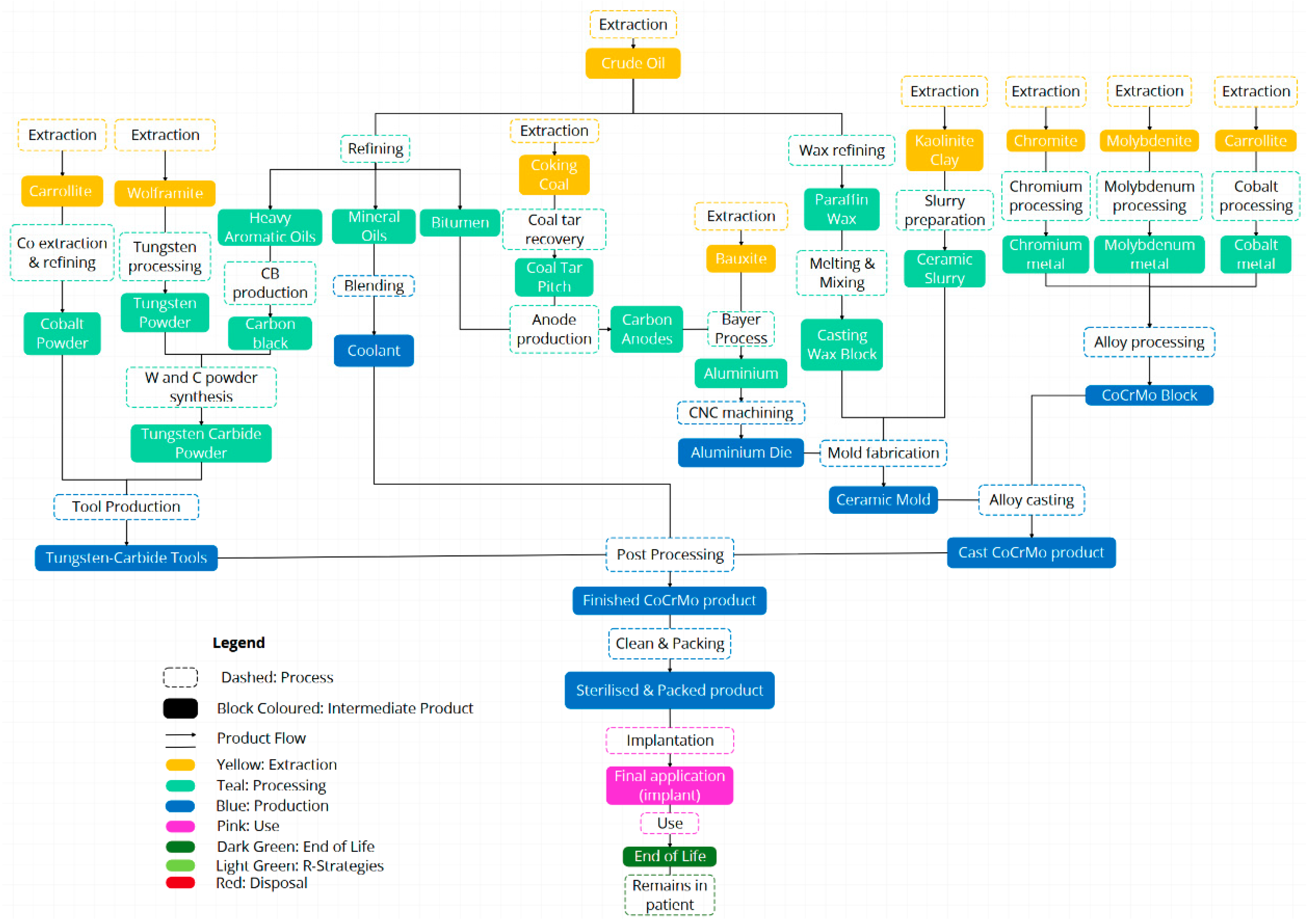

- The main component of the knee implant is made from a cobalt-chromium-molybdenum (CoCrMo) alloy, as shown in Table 3.

| Material (CoCrMo) |

Mass (%) |

|---|---|

| Co | 63.0 - 68.0 |

| Cr | 27.0 – 30.0 |

| Mo | 5.0 – 7.0 |

| Others < 1% | Ni (<0.5%), Fe (<0.75%), C (<0.35%), Si (<1%), Mn (<1%), W (<0.2%), P (<0.02%), S (<0.01%), N (<0.25%), Al (<0.1%), Ti (<0.1%), B(<0.01%) |

- Product function: Trauma plates serve as reconstruction devices that support bone fracture healing.

- The trauma plate, composed of titanium, aluminium, and vanadium as the main materials, as listed in Table 2.

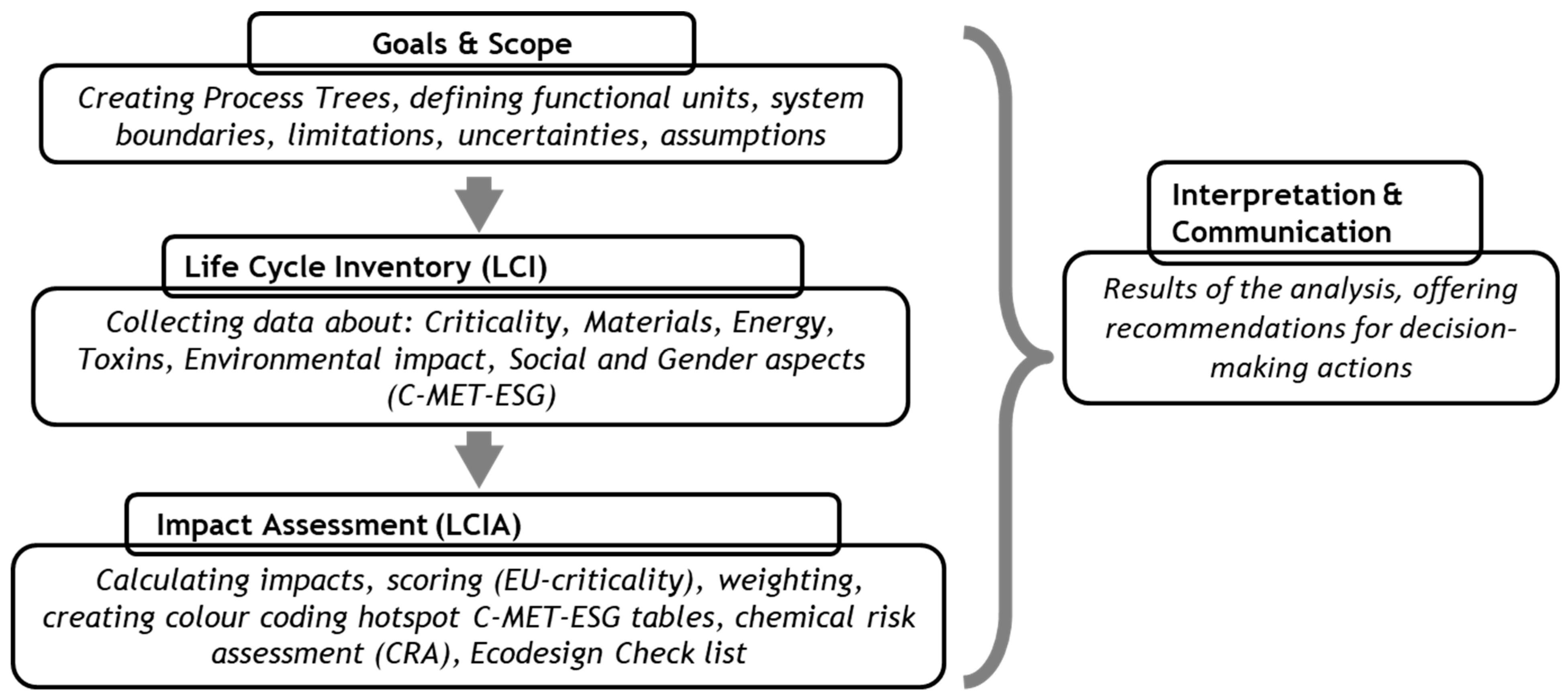

2.2. Life Cycle Assessment Approach

2.2.1. Goals & Scope

2.2.2. Life Cycle Inventory

2.2.3. Life Cycle Impact Analysis (LCIA)

- Criteria define the specific endpoints or parameters under evaluation, such as carcinogenicity, persistence, bioaccumulation, or acute toxicity.

- Within each criterion, levels classify the degree of concern based on intrinsic hazard, ranging from Level 0 (highest concern and priority for substitution) to Level 2 (lower concern but requiring review or risk reduction).

- Complementing these, H numbers (hazard numbers) are semi-quantitative scores primarily applied in production and processing risk assessments to indicate the magnitude of safety hazards under specific exposure scenarios: H1 represents high risk that requires immediate mitigation or substitution, whereas H2 denotes medium risk requiring monitoring and risk reduction.

| Aspect | Term | Description | Meaning/Implication | Priority/Action |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assessment parameter | Criteria | Specific hazard or sustainability endpoints evaluated (e.g., carcinogenicity, toxicity, persistence). | Defines what is assessed. | Basis for assessment. |

| Classification | Levels | Categories rank severity or concern within each criterion (e.g., 0, 1, 2). | Degree of hazard or concern. | Level 0 = highest concern. Level 1 = chronic effects needing. Level 2 = other hazards needing review. |

| Hazard Score | H Numbers | Semi-quantitative hazard scores are primarily used in production/processing risk assessments. | Represents the magnitude of hazard/exposure. | H1 = High risk, prioritise substitution/modification. H2 = medium risk, flagged for review/reduction. |

2.2.4. Interpretation and Communication

3. Results

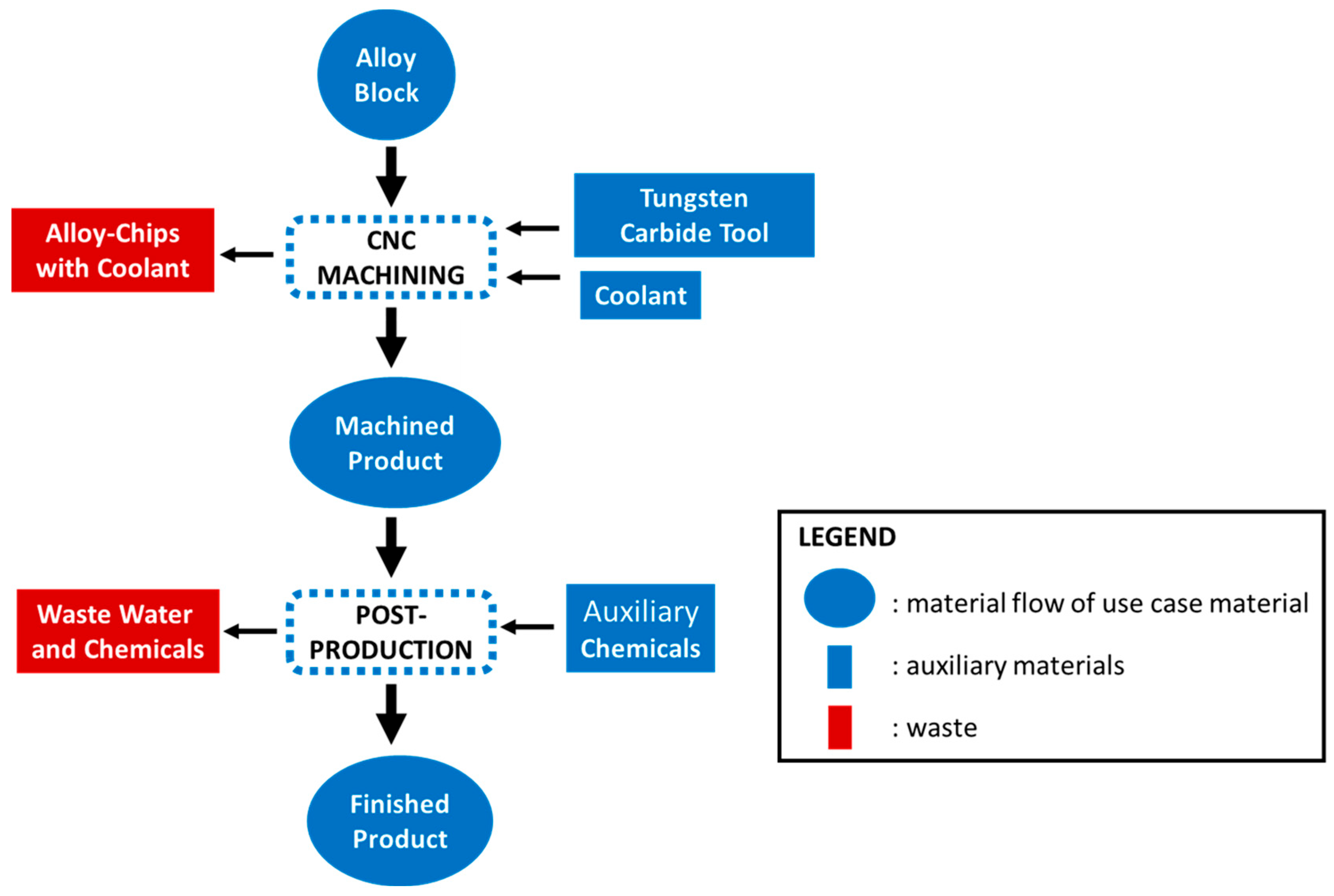

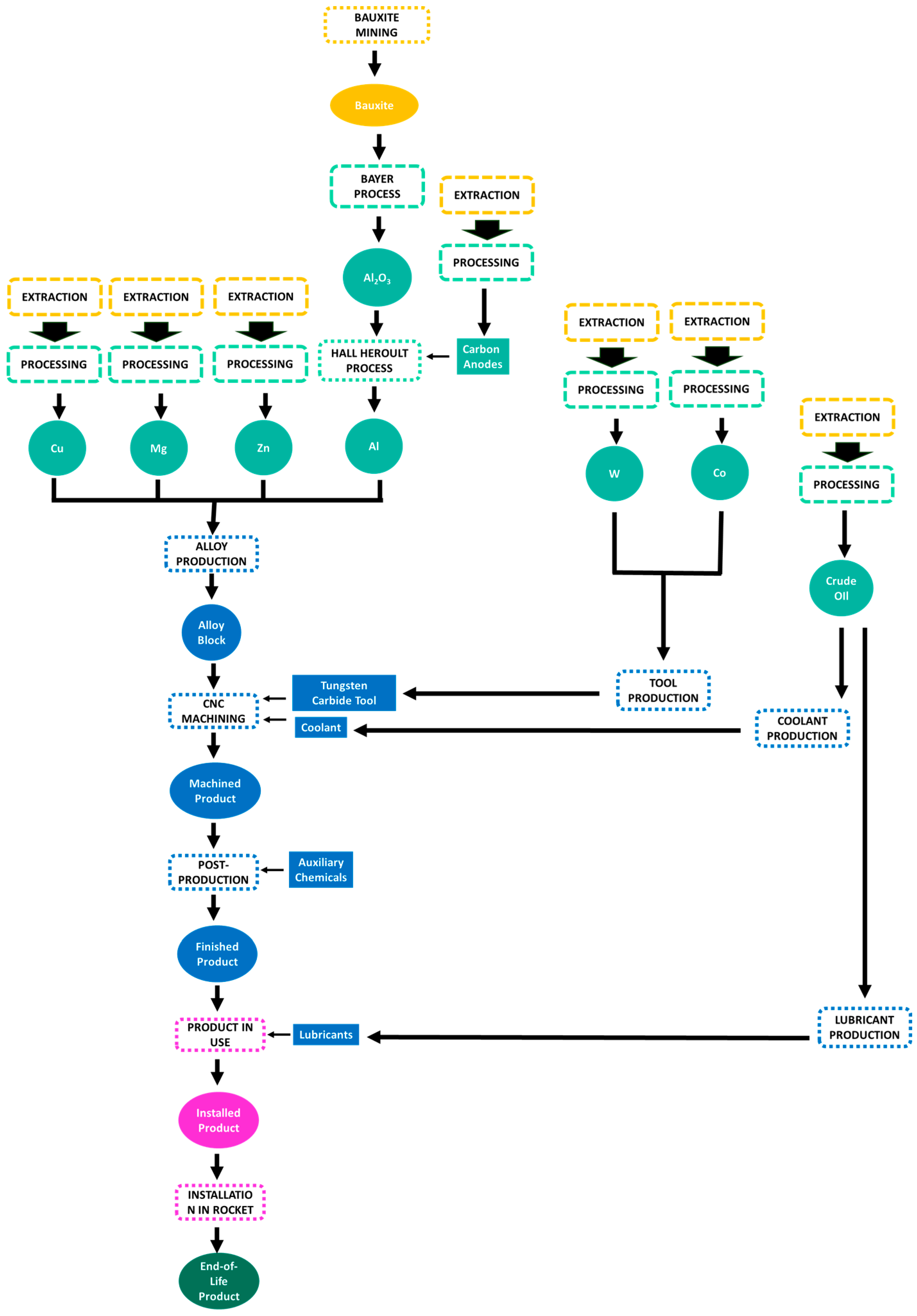

3.1. Life Cycle Inventory

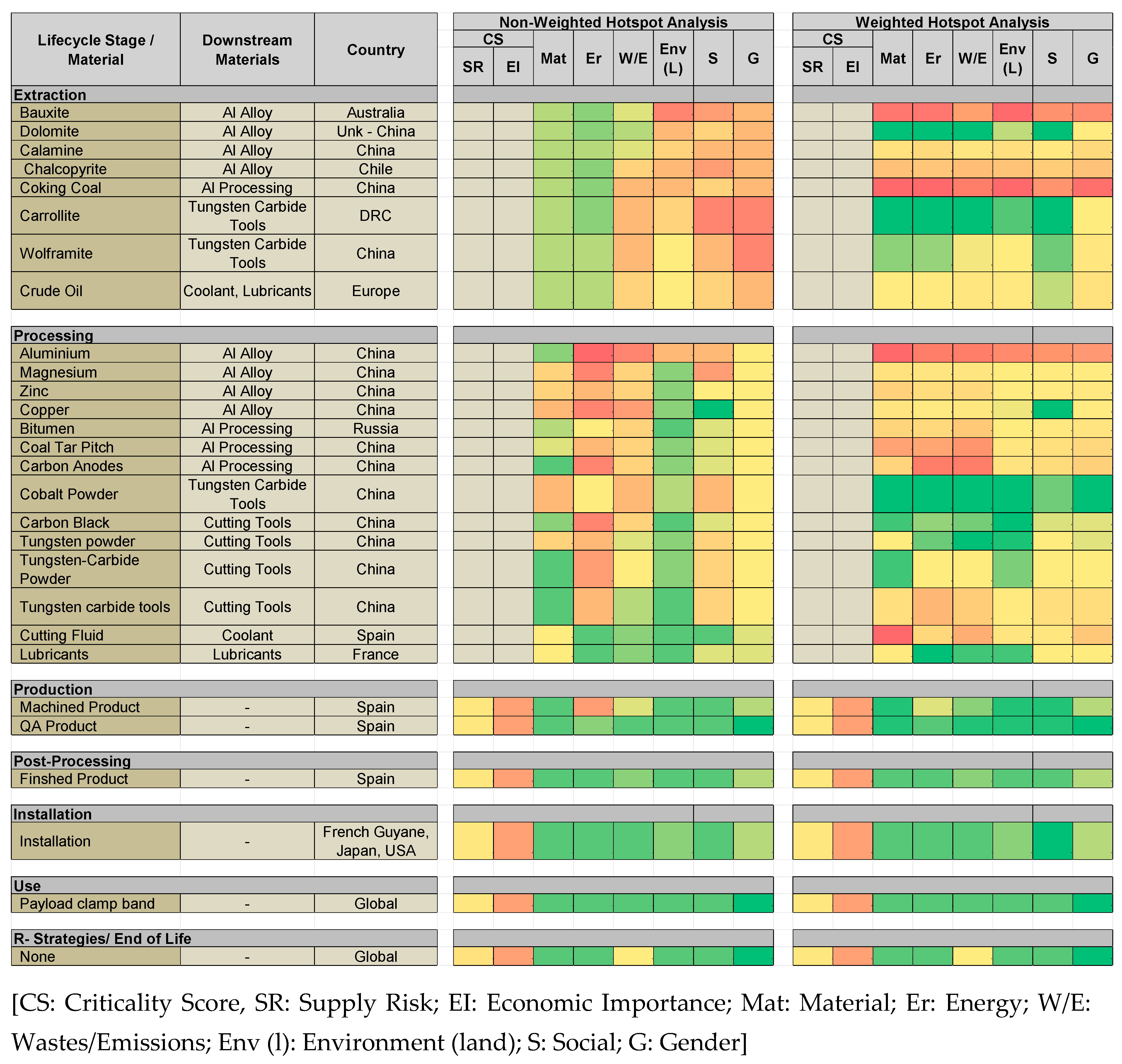

3.1.1. Use Case 1: Clamp Band

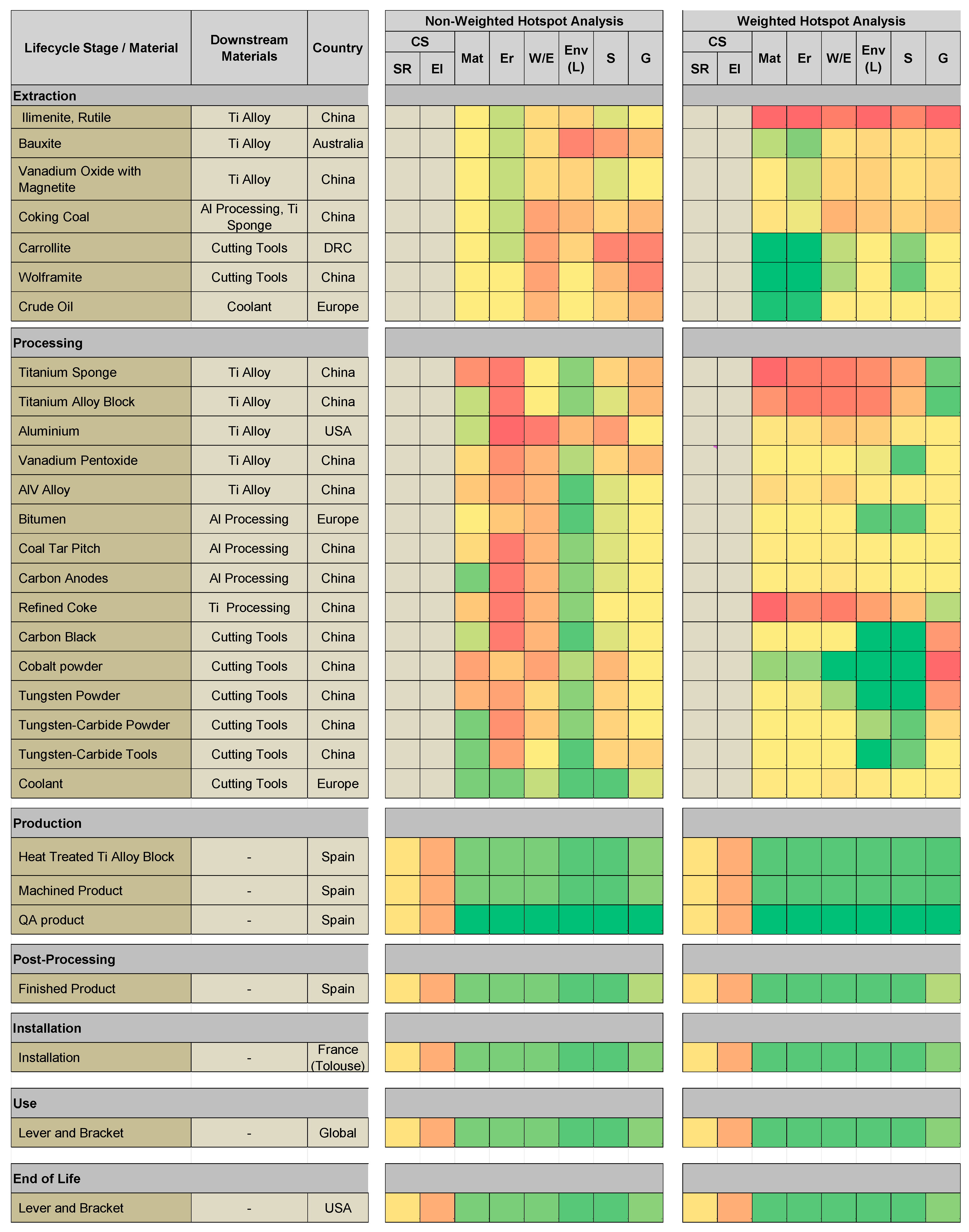

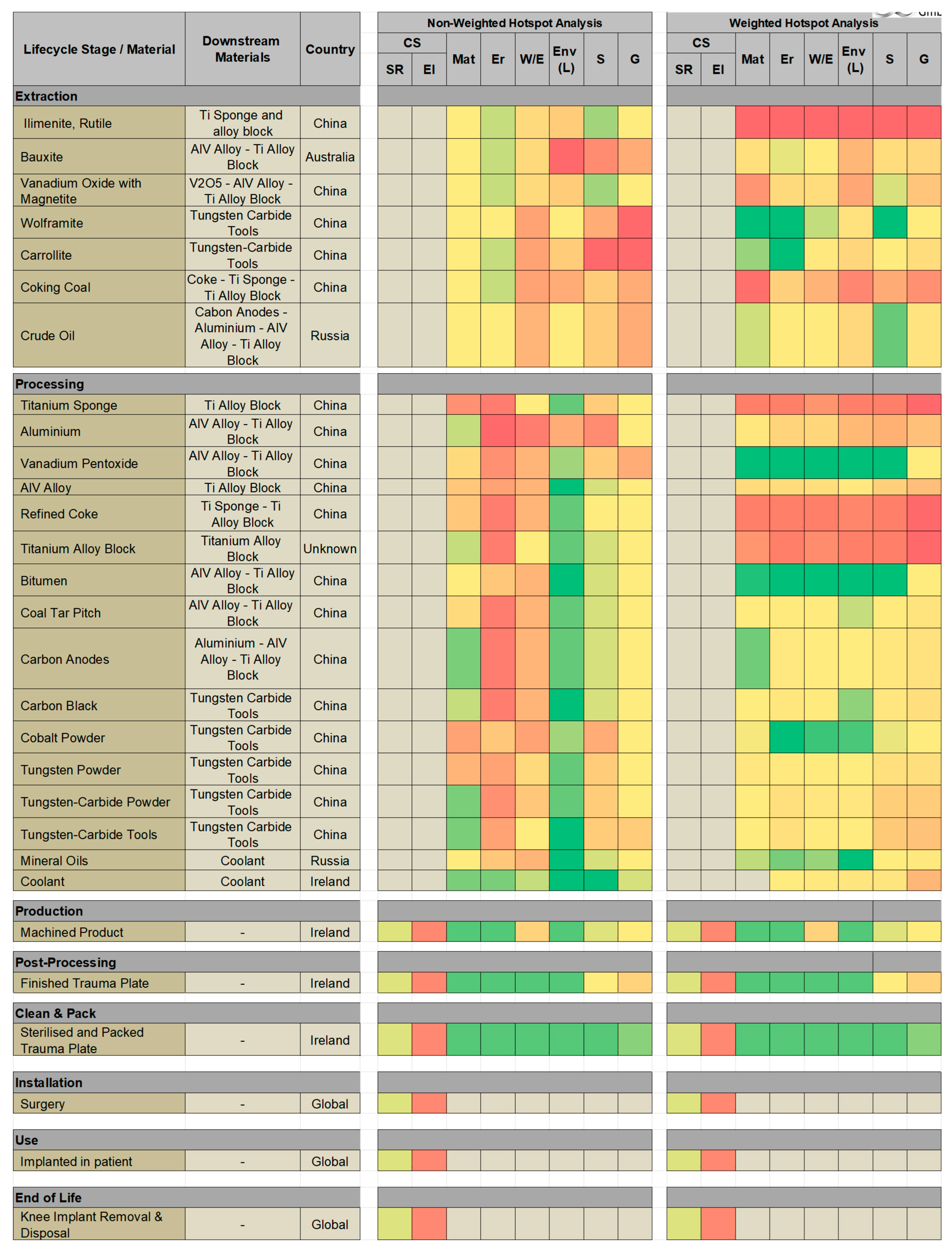

3.1.2. Use Case 2 & 3: Pivot Bracket and Lever

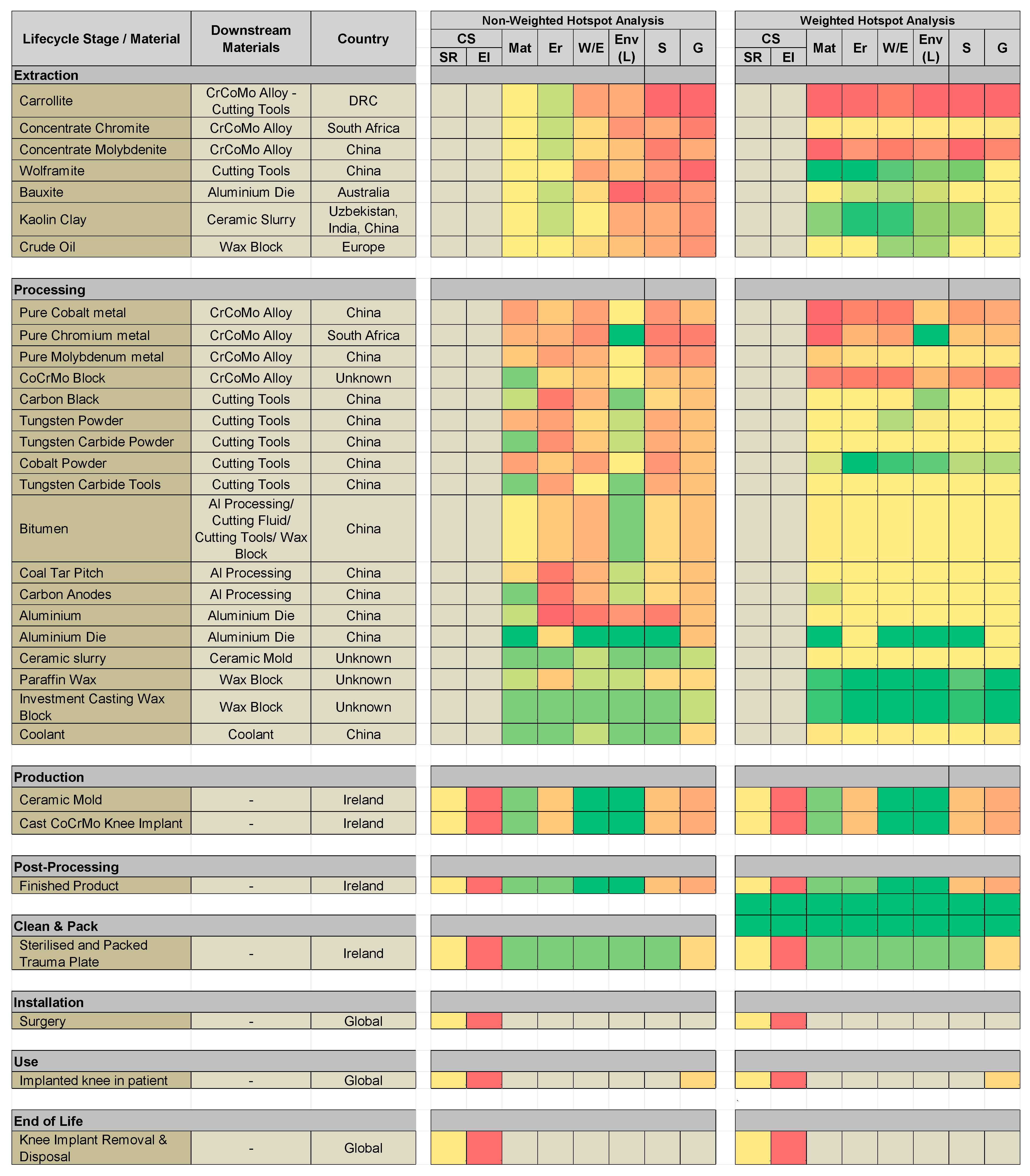

3.1.3. Use Case 4: Femoral Component of Knee Implant

3.1.4. Use Case 5: Trauma Plate

3.2. Life Cycle Impact Analysis

3.2.1. C-MET-ESG Hotspot Analysis

3.2.2. Common Outcomes for all Use Cases

- Labour standards and enforcement,

- Occupational safety risks, such as exposure to hazardous chemicals and physical injury,

- Worker rights, including conditions for migrant labour and collective bargaining,

- Gender-specific vulnerabilities in factory and laboratory settings [22].

3.2.3. Eco-Design Checklist

4. Discussion

4.1. Processes and Material Efficiency

4.2. Supply-Chain Resilience

4.3. Worker and Operational Safety

4.4. Social and Environmental Responsibility

4.5. Gender Specific Risk Mitigation

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

| Use of Low impact material | Resource efficiency |

|

|

| Design for functionality | Design for recyclability |

|

|

| Contribution to health and social well-being | |

| |

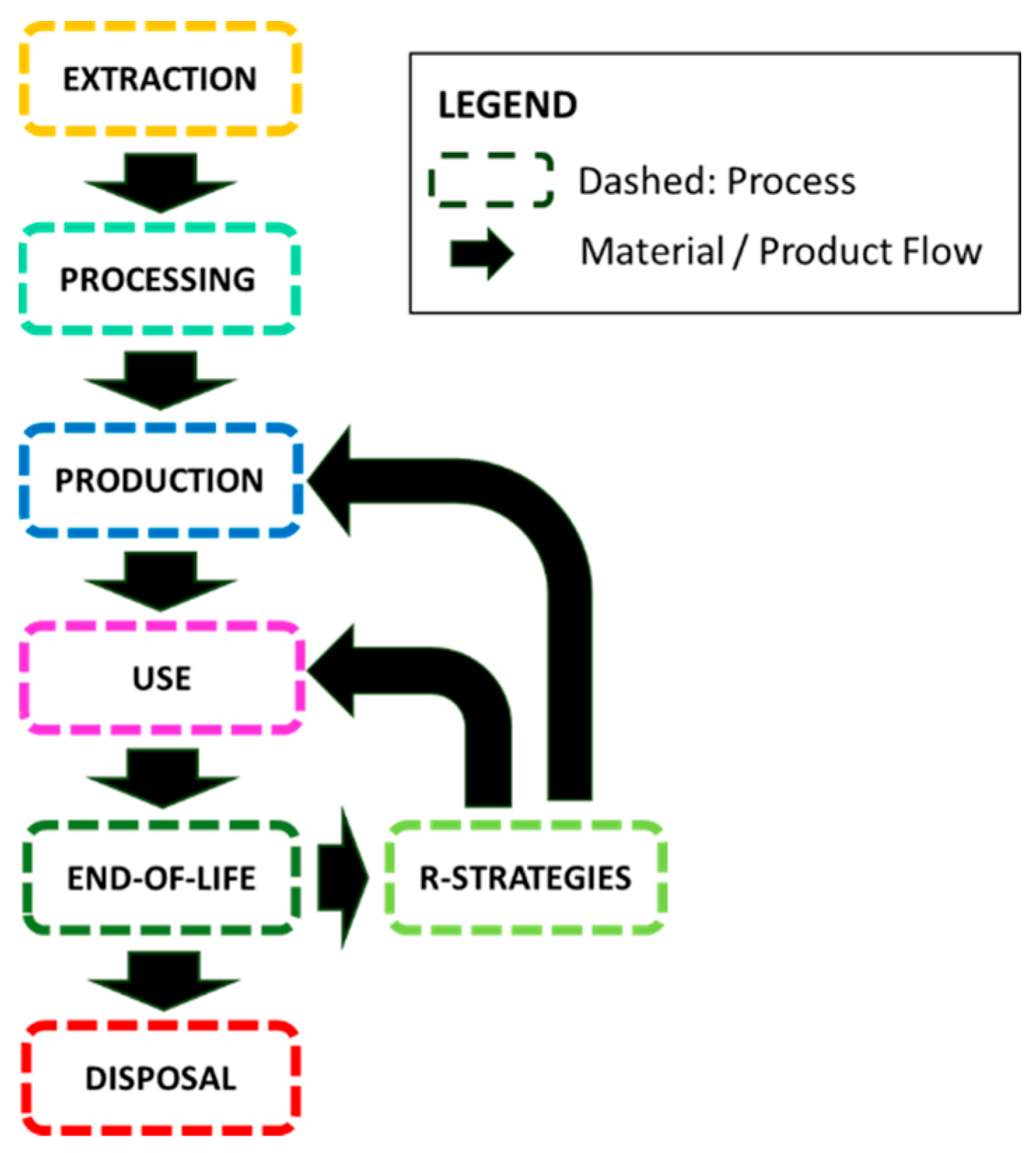

| Terminology | Description applied in the study |

|---|---|

| Extraction | Obtaining raw materials from the environment—through mining, drilling, or agriculture—and may include beneficiation at the extraction site. |

| Material processing |

Converting these primary products into usable materials via processes such as smelting, purification, or leaching. |

| Production | The conventional manufacturing process defined for each use case, such as CNC machining or lost-wax injection moulding. |

| Post-processing | Operations after production, such as surface treatments, cleaning, testing, and inspection. In biomedical use cases, this also includes packing and gamma-ray sterilisation. |

| Installation | The assembly and integration of the final product to ensure its operability. |

| Use | The operational phase, including any maintenance required to retain functionality. |

| End-of-life | All processes following the product’s use phase, including disposal, recycling, or remanufacturing into new products. |

| R-strategies | Approaches include recycling, remanufacturing, reuse, refurbishing, and similar methods. |

| 1 | SDG 1: No Poverty, SDG 2: Zero Hunger, SDG 3: Good Health and Well-being, SDG 4: Quality Education, SDG 5: Gender Equality, SDG 6: Clean Water and Sanitation, SDG 7: Affordable and Clean Energy, SDG 8: Decent Work and Economic Growth, SDG 9: Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure, SDG 10: Reduced Inequalities, SDG 11: Sustainable Cities and Communities, SDG 12: Responsible Consumption and Production, SDG 13: Climate Action, SDG 14: Life Below Water, SDG 15: Life on Land, SDG 16: Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions, SDG 17: Partnerships for the Goals |

References

- Ge, M.; Friedrich, J.; Vigna, L. Where Do Emissions Come From? 4 Charts Explain Greenhouse Gas Emissions by Sector. World Resour. Inst. 2025, 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- IEA Tracking Industry - CO2 Emissions in the Industry Sector; 2022.

- United Nations Environment Programme Bend the Trend - Pathways to a Liveable Planet as Resource Use Spikes; 2024; ISBN 978-92-807-4128-5.

- Save the Children International Child Rights and Cobalt Supply Chain in DRC. Available online: https://resourcecentre.savethechildren.net/document/child-rights-and-cobalt-supply-chain-in-drc/.

- Frank, E.; Mühlhaus, R.; Mustelin, K.M.; Trilken, E.L.; Kreuz, N.K.; Bowes, L.C.; Backer, L.M.; von Wehrden, H. A Systematic Review of Peer-Reviewed Gender Literature in Sustainability Science. Sustain. Sci. 2024, 19, 1459–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, J.R.; Kemp, D.; Lechner, A.M.; Harris, J.; Zhang, R.; Lèbre, É. Energy Transition Minerals and Their Intersection with Land-Connected Peoples. Nat. Sustain. 2023, 6, 203–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission Safe and Sustainable by Design: Chemicals and Materials. Available online: https://environment.ec.europa.eu/strategy/chemicals-strategy_en.

- European Parliament Regulation (EU) 2024/1252, (Critical Raw Materials Act). Eur. Parliam. Counc. Eur. Union. Off. J. Eur. Union 2024, L (2024-05.

- European Commission Study on the Critical Raw Materials for the EU - Final Resport; 2023.

- Li, L.; Li, C.; Tang, Y.; Yi, Q. Influence Factors and Operational Strategies for Energy Efficiency Improvement of CNC Machining. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 161, 220–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Bi, G.; Yao, X.; Su, J.; Tan, C.; Feng, W.; Benakis, M.; Chew, Y.; Moon, S.K. In-Situ Process Monitoring and Adaptive Quality Enhancement in Laser Additive Manufacturing: A Critical Review. J. Manuf. Syst. 2024, 74, 527–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegab, H.; Khanna, N.; Monib, N.; Salem, A. Design for Sustainable Additive Manufacturing: A Review. Sustain. Mater. Technol. 2023, 35, e00576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, I.; Rosen, D.; Stucker, B. Additive Manufacturing Technologies 3D Printing, Rapid Prototyping, and Direct Digital Manufacturing; 2024; Vol. Part F3814; ISBN 9781493921126.

- Khairallah, S.A.; Anderson, A.T.; Rubenchik, A.; King, W.E. Laser Powder-Bed Fusion Additive Manufacturing: Physics of Complex Melt Flow and Formation Mechanisms of Pores, Spatter, and Denudation Zones. Acta Mater. 2016, 108, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulko, L.; Soldera, M.; Lasagni, A.F. Structuring and Functionalization of Non-Metallic Materials Using Direct Laser Interference Patterning: A Review. Nanophotonics 2022, 11, 203–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO ISO 14006: 2020 Environmental Management Systems - Guidelines for Incorporating Ecodesign; 2020.

- Cinelli, M.; Coles, S.R.; Kirwan, K. Analysis of the Potentials of Multi Criteria Decision Analysis Methods to Conduct Sustainability Assessment. Ecol. Indic. 2014, 46, 138–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cinelli, M.; Coles, S.R.; Kirwan, K.; Centre, I.M. Use of Multi Criteria Decision Analysis To Support Life Cycle Sustainability Assessment : An Analysis of the Appropriateness of the Available Methods. Lcm 2013 2013, 2003–2006. [Google Scholar]

- ISO ISO 209:2024 Wrought Aluminium and Aluminium Alloys — Chemical Composition. Int. Stand. Organ. 2024.

- DIN EN ISO 14040 Environmental Management – Life Cycle Assessment – Principles and Framework (ISO 14040:2009). DIN Dtsch. Inst. für Normung 2006.

- Owen, J.R.; Kemp, D.; Lechner, A.M.; Harris, J.; Zhang, R.; Lèbre, É. Author Correction: Energy Transition Minerals and Their Intersection with Land-Connected Peoples (Nature Sustainability, (2022), 6, 2, (203-211), 10.1038/S41893-022-00994-6). Nat. Sustain. 2023, 6, 1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollitzer, E. Why Gender Is Relevant to Materials Science and Engineering. MRS Commun. 2021, 11, 656–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Go Nano The Importance of Gender and Diversity in Nanotechnology Research and Innovation. 2020.

- ECHA Sustainable-by-Design Framework in Industrial Policy.

- Crul, M.R.M.; Diehl, J.C.; Lindqvist, T.; Ryan, C.; Tischner, U.; Vezzoli, C.; Boks, C.B.; Manzini, E.; Jegou, F.; Meroni, A.; et al. Design for Sustainable: A Step-by-Step Approach; 2009; ISBN 9280727117.

- EU Parliament DIRECTIVE 2009/125/EC OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL of 21 October 2009: Establishing a Framework for the Setting of Ecodesign Requirements for Energy-Related Products; 2009.

- ISO ISO 8079:2025 Aerospace Process — Anodic Treatment of Aluminium Alloys — Sulfuric Acid Process, Dyed Coating. Int. Stand. Organ. 2025.

- AIRBUS End-of-Life Reusing, Recycling, Rethinking. Available online: https://aircraft.airbus.com/en/newsroom/news/2022-11-end-of-life-reusing-recycling-rethinking?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- Rankin, W.J. Minerals, Metals and Sustainability; CSIRO Publishing, 2011; ISBN 978-0-643-10422-8.

- Gao, F.; Nie, Z.; Yang, D.; Sun, B.; Liu, Y.; Gong, X.; Wang, Z. Environmental Impacts Analysis of Titanium Sponge Production Using Kroll Process in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 174, 771–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coherent Market Insights Pvt Ltd Environmental Impact of Ilmenite Mining and Sustainable Practices in the Industry. Available online: https://www.coherentmarketinsights.com/blog/environmental-impact-of-ilmenite-mining-and-sustainable-practices-in-the-industry-1043 (accessed on 22 August 2025).

- Prasad, S.; Yadav, K.K.; Kumar, S.; Gupta, N.; Cabral-Pinto, M.M.S.; Rezania, S.; Radwan, N.; Alam, J. Chromium Contamination and Effect on Environmental Health and Its Remediation: A Sustainable Approaches. J. Environ. Manage. 2021, 285, 112174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rukini, A.; Rhamdhani, M.A.; Brooks, G.A.; Van den Bulck, A. Metals Production and Metal Oxides Reduction Using Hydrogen: A Review. J. Sustain. Metall. 2022, 8, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Bolan, S.; Mukherjee, S.; Zhou, P.; Yang, X.; White, J.C.; Zuverza-Mena, N.; Zhang, T.; Chen, J.; Xu, Q.; et al. Titanium: Metal of the Future or an Emerging Environmental Contaminant? Explor. Environ. Resour. 2025, 0, 025130027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delaie, C.; Cerlier, A.; Argenson, J.N.; Escudier, J.C.; Khakha, R.; Flecher, X.; Jacquet, C.; Ollivier, M. Ecological Burden of Modern Surgery: An Analysis of Total Knee Replacement’s Life Cycle. Arthroplast. Today 2023, 23, 101187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Aluminium Aluminium Production Energy Data & Red Mud Impacts. Available online: https://european-aluminium.eu.

- Tsurukawa, N.; Prakash, S.; Manhart, A. Social Impacts of Artisanal Cobalt Mining in Katanga, Democratic Republic of Congo. Öko-Institut eV - Inst. Appl. Ecol. Freibg. 2011, 49, 65. [Google Scholar]

- Iguma Wakenge, C.; Bashwira Nyenyezi, M.R.; Bergh, S.I.; Cuvelier, J. From ‘Conflict Minerals’ to Peace? Reviewing Mining Reforms, Gender, and State Performance in Eastern Democratic Republic of Congo. Extr. Ind. Soc. 2021, 8, 100894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uter, W.; Schnuch, A.; Geier, J.; Frosch, P.J. Epidemiology of Contact Dermatitis. The Information Network of Departments of Dermatology (IVDK) in Germany. Eur. J. Dermatol. 1998, 8, 36–40. [Google Scholar]

- Thyssen, J.P.; Menné, T. Metal Allergys-A Review on Exposures, Penetration, Genetics, Prevalence, and Clinical Implications. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2010, 23, 309–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koščová, M.; Hellmer, M.; Anyona, S.; Gvozdkova, T. Geo-Environmental Problems of Open Pit Mining: Classification and Solutions. E3S Web Conf. 2018, 41, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samir, M.; Alama, F.; Buysse, P.; Van Nylen, T.; Ostanin, O. Disposal of Mining Waste: Classification and International Recycling Experience. E3S Web Conf. 2018, 41, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, S.; Despeisse, M.; Viljakainen, A. Extending Product Life through Additive Manufacturing : The Sustainability Implications Extending Product Life through Additive Manufacturing : The Sustainability Implications. 2015.

- Cai, Q.; Xu, J.; Lian, Z.; Yu, Z.; Yu, H.; Yang, S.; Li, J. Laser-Induced Slippery Liquid-Infused Surfaces with Anticorrosion and Wear Resistance Properties on Aluminum Alloy Substrates. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 28160–28172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzipanagiotou, K.R.; Petrakli, F.; Steck, J.; Philippot, C.; Artous, S.; Koumoulos, E.P. Towards Safe and Sustainable by Design Nanomaterials: Risk and Sustainability Assessment on Two Nanomaterial Case Studies at Early Stages of Development. Sustain. Futur. 2025, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soeteman-Hernández, L.G.; Tickner, J.A.; Dierckx, A.; Kümmerer, K.; Apel, C.; Strömberg, E. Accelerating the Industrial Transition with Safe-and-Sustainable-by-Design (SSbD). RSC Sustain. 2025, 3, 2185–2191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mugoni, E.; Kanyepe, J.; Tukuta, M. Sustainable Supply Chain Management Practices (SSCMPS) and Environmental Performance: A Systematic Review. Sustain. Technol. Entrep. 2024, 3, 100050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katiyar, R.; Meena, P.L.; Barua, M.K.; Tibrewala, R.; Kumar, G. Impact of Sustainability and Manufacturing Practices on Supply Chain Performance: Findings from an Emerging Economy. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2018, 197, 303–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadzadeh Sanandaji, M.; Mollick, R.; Ratner, A.; Ding, H. Laser-Enabled Organic Coating for Sustainable PFAS-Free Metal Surfaces. Manuf. Lett. 2025, 45, 8–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamaludin, N.F.; Hashim, H.; Muis, Z.A.; Zakaria, Z.Y.; Jusoh, M.; Yunus, A.; Abdul Murad, S.M. A Sustainability Performance Assessment Framework for Palm Oil Mills. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 174, 1679–1693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.T.; Safder, U.; Kim, J.I.; Heo, S.K.; Yoo, C.K. An Adaptive Safety-Risk Mitigation Plan at Process-Level for Sustainable Production in Chemical Industries: An Integrated Fuzzy-HAZOP-Best-Worst Approach. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 339, 130780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Criterion | Definition | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Material Criticality |

It is represented using the Supply Risk (SR) and Economic Importance (EI) scores from the EU 2023 Critical Raw Materials Report. | [9] |

| Energy | Refer to the total energy required to operate a given process. This includes: fuels, particularly for extraction processes; heat energy, often needed during material processing; and electricity required for operations such as electrolysis or the use of machinery (e.g., CNC machines in production). | [2,7] |

| Toxins (Wastes/Emissions) | Include all solid waste and gaseous emissions released during a process: hazardous or non-hazardous. This category also includes thermal pollution, such as heat discharged via cooling water. | [3] |

| Environmental impacts | Focus primarily on land-related effects, including changes in land use and their consequences for vegetation, wildlife, and ecosystems. | [21] |

| Social | Cover both the risks and impacts on workers and local communities where specific life cycle activities occur. It captures aspects such as the likelihood and severity of unsafe working conditions and the broader social impacts on nearby populations, particularly vulnerable groups such as children, women, and the aged. | [4,5] |

| Gender | Specifically evaluates gender-differentiated risks and impacts, focusing on how each gender may be uniquely affected by conditions at each life cycle stage. | [22,23] |

| Category | Score 1 | Score 10 |

|---|---|---|

| Material | Consumption of materials with low environmental and/or human health toxicity. | Use of materials with significant environmental and/or human health toxicity. |

| Energy | Low relative energy consumption, defined as kJ/ kg processed. | High relative energy consumption, defined as kJ/kg processed. |

| Toxins (Waste/Emissions) | Low risk of releasing non-hazardous waste or emissions. | Risk of releasing highly hazardous waste or emissions. |

| Environmental | Minimal impact on surrounding land, small facility footprint, and negligible effects on vegetation and animal populations. | Significant land impact, large facility footprint, and major damage to vegetation and animal populations. |

| Social/Gender | Standard procedures with low occupational health and safety risks and minimal impact on local populations, especially vulnerable groups such as women, children, and indigenous peoples. | Poor and unsafe working conditions violate regulations or have significant negative impacts on local vulnerable populations. |

| Upstream and extraction stages | Processing and manufacturing |

| Women involved in artisanal and small-scale mining (ASM), often working alongside children in hazardous tasks like bagging and sorting minerals, face unsafe environments, wage disparities, and perpetuated poverty than the men [4,37]. Broader social impacts affect women disproportionately, including resource scarcity, land dispossession, and insecure, low-wage employment with poor legal protections, especially for indigenous communities affected by forced resettlement due to mining [5,38]. Women and girls often bear the burden of water collection, especially where industrial activities deplete or pollute sources, increasing time demands and exposure to harassment risks, which reduce opportunities for education and personal development [21]. |

A significant share of materials in use cases are processed in China, where both genders experience high exposure to hazardous chemicals with limited access to personal protective equipment (PPE) [5,22] In most cases, the women constitute a large part of the factory workforce. Women workers, particularly migrants, often face longer hours, precarious job security and limited access to well-fitting women's PPEs than men. Social vulnerabilities such as wage gaps, limited training and promotion opportunities, childcare deficiencies, and sexual harassment are further compounded risks for women in these settings [5,22]. |

| Metal-allergy risks (use phase) | Chemical exposure risks(Production and post-production) |

| Women show a notably higher prevalence of contact allergies to metals - especially nickel, cobalt, and chromium - with prevalence estimates between 17–22% for nickel allergy in women versus 3–5% in men. [39,40]. Allergic reactions can arise during material handling and manufacturing stages due to repeated occupational exposure, causing dermatitis and other allergic responses [40]. For medical devices like knee implants using cobalt-chromium alloys, women’s higher hypersensitivity rates contribute to clinically relevant local or systemic reactions, potentially impacting implant success [40]. |

Occupational exposure to process chemicals (e.g., solvents, acids, and anodising baths) in manufacturing and finishing stages poses health risks. Both men and women may have increased sensitivity due to biological factors and higher cumulative exposure from both workplace and daily life activities (e.g., household chemical use) [5,22]. |

| Eco-design question: | Are the materials being used toxic to humans? |

|---|---|

| Processing Stage: | Material toxicity is highest during the processing stage. Harmful and toxic chemicals are used in multiple processing steps, e.g., H2SO4 (cobalt, vanadium), H2S (vanadium), HF (Hall–Héroult process for aluminium). Hydrogen fluoride (HF) is highly toxic. TiCl4, generated during carbo-chlorination and used in the Kroll process for titanium, is a toxic, corrosive, water-reactive chemical that, upon contact with water, rapidly forms toxic hydrochloric acid (HCl). |

| Manufacturing Stage: | Material toxicity during manufacturing (CNC machining) is limited, mainly arising from coolant use. Coolant typically consists of water with mineral oil, but still requires proper handling and personal protective equipment (PPE). |

| Recommendations for improvement based on eco-design checklist: | |

| Reduce the use of materials requiring harmful chemicals (e.g., cobalt, vanadium) or highly toxic chemicals (e.g., aluminium, titanium) via improved resource efficiency — for example, by adopting additive manufacturing in place of CNC machining. | |

| Minimise material wastage in downstream processes, thereby reducing the quantity of toxic and harmful chemicals consumed in upstream processing. | |

| Eliminate the generation of toxic, corrosive, water-reactive TiCl4 during titanium processing through material substitution and implementation. | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).