Submitted:

18 September 2025

Posted:

22 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Multi Directional Forging

2.2. Microstructural Characterization

2.3. Mechanical Properties

2.4. Electrochemical Corrosion Testing

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Microstructure and Phase Evolution of the MDF Samples

3.2. Mechanical Response

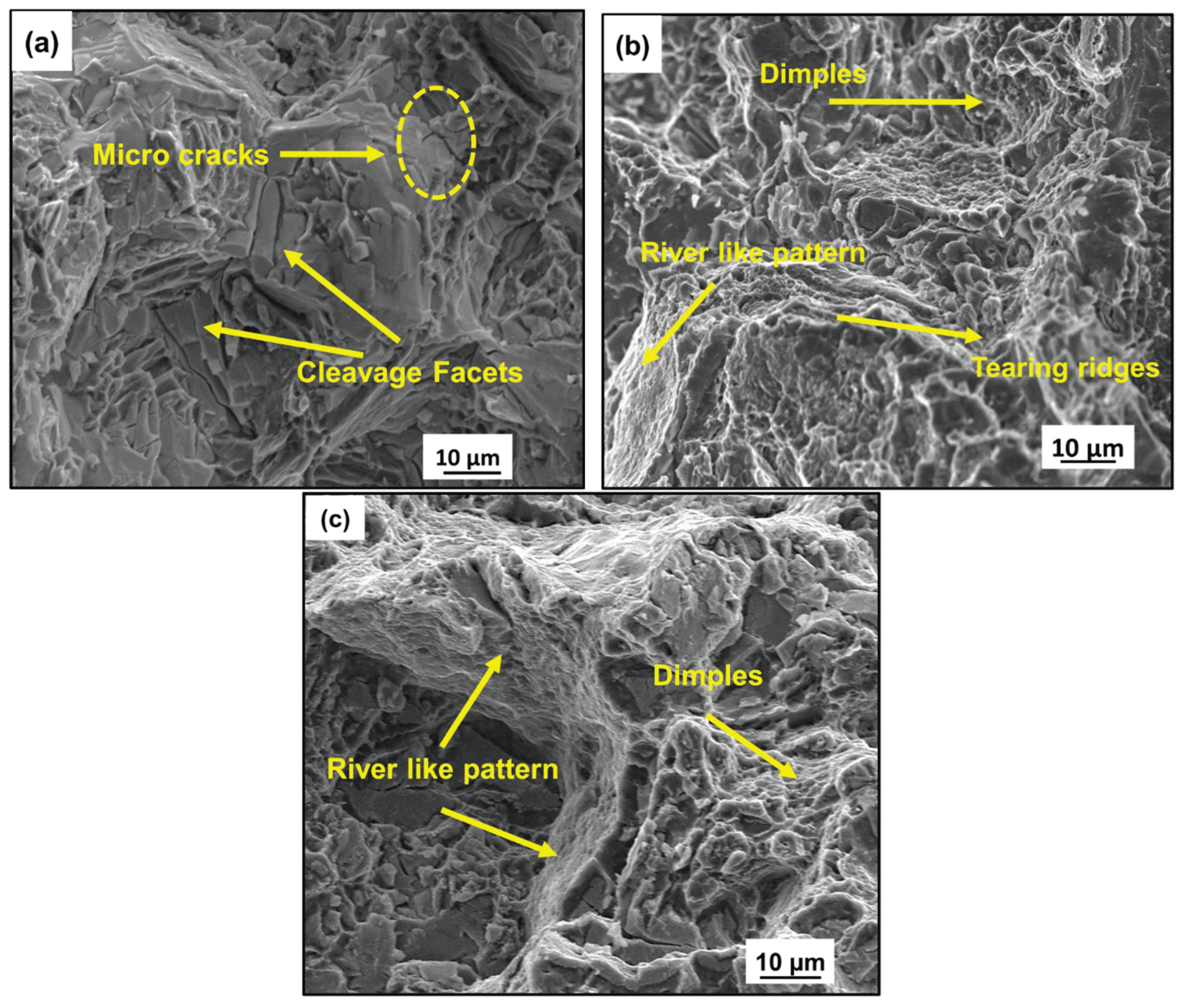

3.2.1. Tensile Behavior and Fracture Analysis

3.2.2. Microhardness Evolution

3.3. Electrochemical Corrosion Behavior

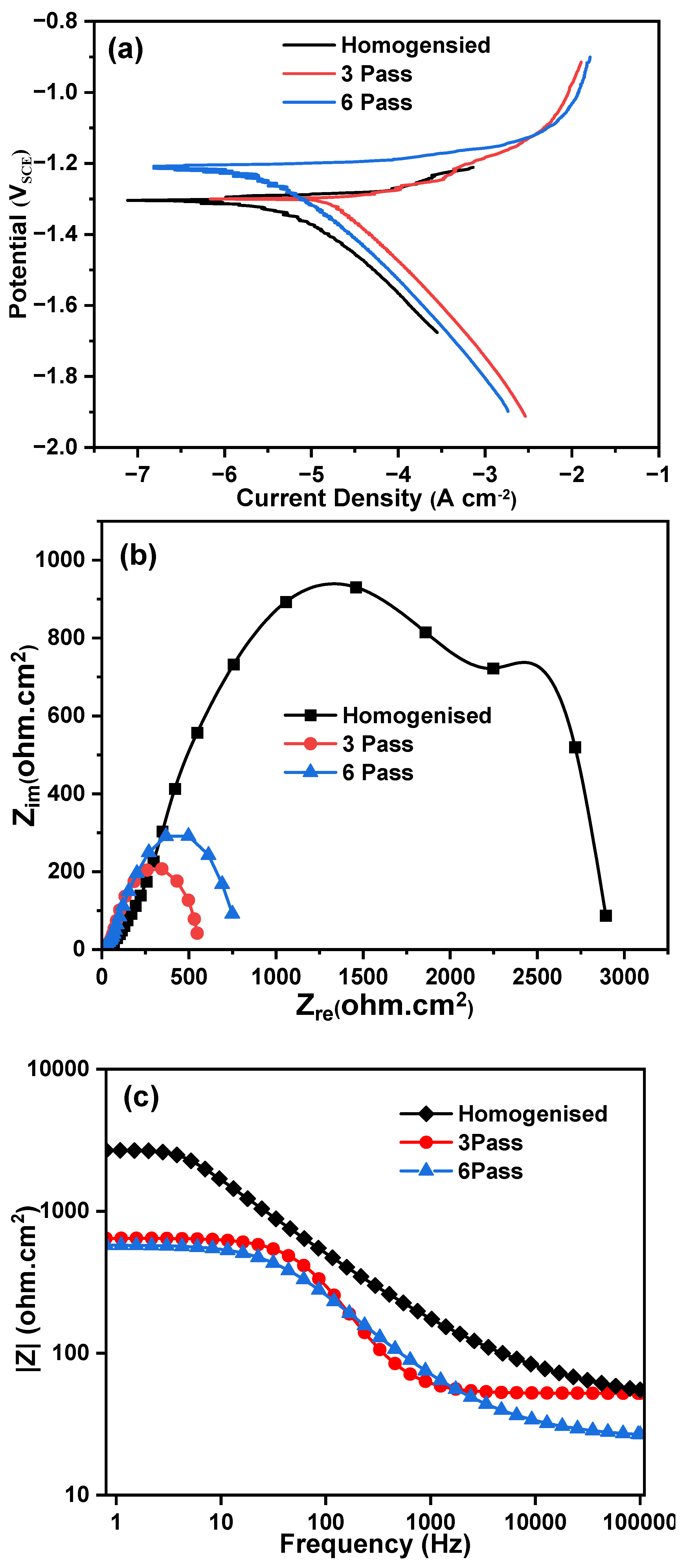

3.3.1. Potentiodynamic Polarization Studies

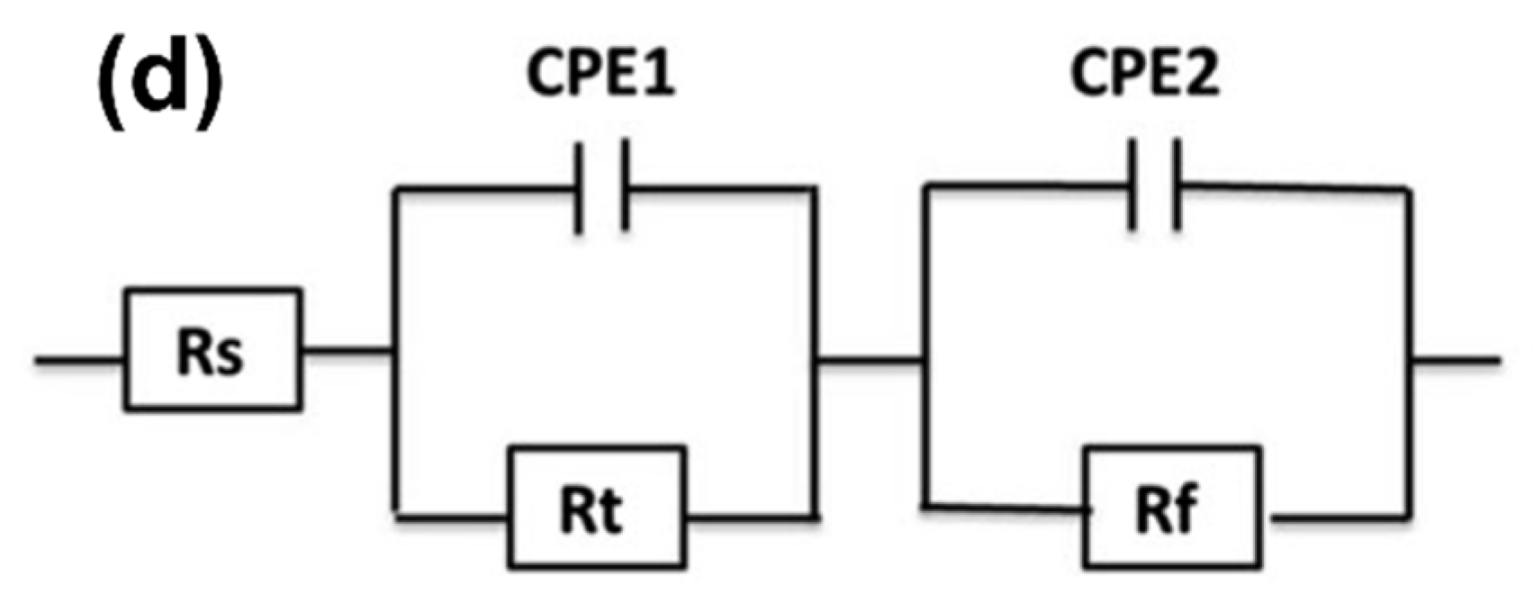

3.3.2. Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy

4. Conclusions

- Grain size reduced from 118 ± 5 µm in homogenized condition to 30 ± 10 µm after 6 passes with uniform distribution of Mg7Zn3 fine particles and semi-continuous Mg12Nd eutectic network.

- The microhardness of the 6 Pass MDF sample increased by 20 %, while UTS and YS exhibited significant enhancements of 59 % and 90 %, respectively compared to homogenized sample. This is due to the fact that the grain refinement, strain hardening and dispersion strengtherning from the second phase particles.

- Additionally, the ductility of the 6 Pass MDF sample improved remarkably, with a 44% increase in elongation, attributed to texture weakening and uniform distribution second phase distribution (resist premature failure).

- Homogenized sample exhibited better corrosion resistance compared to MDF processed samples. Although the corrosion rate of 6 Pass MDF processed sample (0.2499 mm/yr) is higher than that of homogenosed samples (0.1165 mm/yr), this remains within an acceptable range for biodegradable implant applications.

- The slight reduction in corrosion resistance of the MDF processed samples can be attributed to high fraction of LAGB’s and fine second phase particles; however, it does not compromise the alloy’s suitability for biomedical use. Instead, the controlled degradation rate aligns well with the clinical requirements for biodegradable implants, where gradual material dissolution is essential for tissue regeneration.

Data Availability

Acknowledgements

References

- Zheng, L.; Zhao, S.; Li, Y.; Xu, J.; Yan, W.; Guo, B.; Xu, J.; Jiang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Wei, H.; et al. Engineered MgO nanoparticles for cartilage-bone synergistic therapy. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zan, R.; Shen, S.; Huang, Y.; Yu, H.; Liu, Y.; Yang, S. Smart Materials in Medicine Research hotspots and trends of biodegradable magnesium and its alloys. Smart Mater. Med. 2023, 4, 468–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kačarević, Ž.P.; Rider, P.; Elad, A.; Tadic, D.; Rothamel, D.; Sauer, G.; Bornert, F.; Windisch, P.; Hangyási, D.B.; Molnar, B.; et al. Biodegradable magnesium fixation screw for barrier membranes used in guided bone regeneration. Bioact. Mater. 2022, 14, 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, H.; Wee, D.; Toong, Y.; Chen, J.; Ng, K.; Ow, V.; Lu, S.; Poh, L.; En, P.; Wong, H.; et al. Polymer blends and polymer composites for cardiovascular implants. Eur. Polym. J. 2021, 146, 110249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middleton, J.C.; Tipton, A.J. Synthetic biodegradable polymers as orthopedic devices. Biomaterials 2000, 21, 2335–2346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- P. Taylor, M. Ribeiro, F.J. Monteiro, M.P. Ferraz, M. Ribeiro, F.J. Monteiro, M.P. Ferraz, studying bacterial-material interactions Infection of orthopedic implants with emphasis on bacterial adhesion process and techniques used in studying bacterial-material interactions, (n.d.) 37–41. [CrossRef]

- Loskill, P.; Zeitz, C.; Grandthyll, S.; Thewes, N.; Müller, F.; Bischoff, M.; Herrmann, M.; Jacobs, K. Reduced adhesion of oral bacteria on hydroxyapatite by fluoride treatment. Langmuir 2013, 29, 5528–5533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prakasam, M.; Locs, J.; Salma-Ancane, K.; Loca, D.; Largeteau, A.; Berzina-Cimdina, L. Biodegradable Materials and Metallic Implants—A Review. J. Funct. Biomater. 2017, 8, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, K.; Gill, R.S.; Batra, U. Challenges and opportunities for biodegradable magnesium alloy implants. Mater. Technol. 2018, 7857, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, G. Control of biodegradation of biocompatable magnesium alloys. Corros. Sci. 2007. [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Gu, X.; Lou, S.; Zheng, Y. The development of binary Mg-Ca alloys for use as biodegradable materials within bone. Biomaterials 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kottuparambil, R.R.; Bontha, S.; Rangarasaiah, R.M.; Arya, S.B.; Jana, A.; Das, M.; Balla, V.K.; Amrithalingam, S.; Prabhu, T.R. Effect of zinc and rare-earth element addition on mechanical, corrosion, and biological properties of magnesium. J. Mater. Res. 2018, 33, 3466–3478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehdizade, M.; Eivani, A.R.; Esmaielzadeh, O.; Tabatabaei, F. Fabrication of osteogenesis induced WE43 Mg-Hydroxyapatite composites with low biodegradability and increased biocompatibility for orthopedic implant applications. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 25, 4277–4298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, X.N.; Li, S.S.; Li, X.M.; Fan, Y.B. Magnesium based degradable biomaterials: A review. Front. Mater. Sci. 2014, 8, 200–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, F.; Song, G.L.; Atrens, A. Corrosion and passivation of magnesium alloys. Corros. Sci. 2016, 111, 835–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atrens, A.; Shi, Z.; Mehreen, S.U.; Johnston, S.; Song, G.; Chen, X.; Pan, F. Review of Mg alloy corrosion rates. J. Magnes. Alloy. 2020, 8, 989–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.C.; Zhao, Y.C.; Yin, D.F.; Wang, S.; Shangguan, Y.M.; Liu, C.; Tan, L.L.; Shuai, C.J.; Yang, K.; Atrens, A. Biodegradation Behavior of Coated As-Extruded Mg–Sr Alloy in Simulated Body Fluid. Acta Metall. Sin. (English Lett.) 2019, 32, 1195–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razzaghi, M.; Kasiri-Asgarani, M.; Bakhsheshi-Rad, H.R.; Ghayour, H. In Vitro Degradation, Antibacterial Activity and Cytotoxicity of Mg-3Zn-xAg Nanocomposites Synthesized by Mechanical Alloying for Implant Applications. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2019, 28, 1441–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A. Gungor, A. Incesu, Effects of alloying elements and thermomechanical process on the mechanical and corrosion properties of biodegradable Mg alloys, 9 (2021) 241–253. [CrossRef]

- Yamasaki, Y.; Yoshida, Y.; Okazaki, M.; Shimazu, A.; Kubo, T.; Akagawa, Y.; Uchida, T. Action of FGMgCO3Ap-collagen composite in promoting bone formation. Biomaterials 2003, 24, 4913–4920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rokkala, U.; Jana, A.; Bontha, S.; Ramesh, M.R.; Balla, V.K. Comparative investigation of coating and friction stir processing on mg-Zn-Dy alloy for improving antibacterial, bioactive and corrosion behaviour. Surf. Coatings Technol. 2021, 425, 127708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.F.; Rokkala, U. Development of high strength and corrosion resistance Mg-Zn-Dy/HA-Ag composite for temporary implant applications. Mater. Lett. 2023, 347, 134604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prithivirajan, S.; Narendranath, S.; Desai, V. Analysing the combined effect of crystallographic orientation and grain refinement on mechanical properties and corrosion behaviour of ECAPed ZE41 Mg alloy. J. Magnes. Alloy. 2020, 8, 1128–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahmani, A.; Arthanari, S.; Shin, K.S. Achieving a high corrosion resistant and high strength magnesium alloy using multi directional forging. J. Alloys Compd. 2021, 856, 158077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A. Kumar, F.K. MD, S.K. Panigrahi, G.P. Chaudhari, Microstructural evolution and corrosion behaviour of friction stir-processed QE22 magnesium alloy, 39 (2021) 351–360. [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Li, F.; Zhang, J.Y.; Niu, W.T.; Cao, M.Z. Mechanism of work hardening and softening behavior of AZ31 magnesium alloy sheets with hard plate accumulative roll bonding. J. Magnes. Alloy. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimi, M.; Wang, Q.; Attarilar, S. A comprehensive review of magnesium-based alloys and composites processed by cyclic extrusion compression and the related techniques. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2023, 131, 101016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- H. Miura, X. Yang, T. Sakai, Evolution of Ultra-Fine Grains in AZ31 and AZ61 Mg Alloys during Multi Directional Forging and Their Properties Temperature / K ( b ) Single pass, 49 (2008) 1015–1020. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Yuan, L.; Zheng, M.; Wei, Q.; Shan, D.; Guo, B. Achievement of high strength and good ductility in the large-size AZ80 Mg alloy using a designed multi-directional forging process and aging treatment. J. Mater. Process. Tech. 2023, 311, 117828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- G. Anne, R. Sampath, G. Kumar, Development, Characterization, Mechanical and Corrosion Behaviour Investigation of Multi-direction Forged Mg–Zn Alloy, (2019). [CrossRef]

- Ramesh, S.; Anne, G.; Nayaka, H.S.; Sahu, S.; Ramesh, M.R. Influence of Multidirectional Forging on Microstructural, Mechanical, and Corrosion Behavior of Mg-Zn Alloy. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, F.; Deng, K.; Nie, K.; Kang, J.; Niu, H. Microstructure and corrosion properties of Mg-4Zn-2Gd-0.5Ca alloy influenced by multidirectional forging. J. Alloys Compd. 2019, 770, 1208–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.-C.; Liu, M.; Song, G.-L.; Atrens, A. Influence of pH and chloride ion concentration on the corrosion of Mg alloy ZE41. Corros. Sci. 2008, 50, 3168–3178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Han, Q.; Han, X.; Yi, X. Strength – ductility synergy in Mg-Gd-Y-Zr alloys via texture engineering in bi-directional forging. J. Magnes. Alloy. 2024, 12, 4709–4721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R. Wang, F. Yan, J. Sun, W. Xing, S. Li, Microstructural Evolution and Mechanical Properties of Extruded AZ80 Magnesium Alloy during Room Temperature Multidirectional Forging Based on Twin Deformation Mode, (2024).

- Mohammed, S.M.A.K.; Nisar, A.; John, D.; Sukumaran, A.K.; Fu, Y.; Paul, T.; Hernandez, A.; Seal, S.; Agarwal, A. Boron nitride nanotubes induced strengthening in aluminum 7075 composite via cryomilling and spark plasma sintering. Adv. Compos. Hybrid Mater. 2025, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Microstructure Optimization and Strengthening Mechanisms of in-situ TiB2/Al-Cu Composite after Six-Passes Multi-directional Forging. Int. J. Miner. Metall. Mater. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Kang, Z.; Zhou, L. Microstructure evolution and mechanical properties of Mg-Gd-Nd-Zn-Zr alloy processed by equal channel angular pressing. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2015, 647, 184–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, F.; Panigrahi, S.K. Achieving excellent superplasticity in an ultra fi ne-grained QE22 alloy at both high strain rate and low-temperature regimes. J. Alloys Compd. 2018, 747, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rokkala, U.; Bontha, S.; Ramesh, M.R.; Balla, V.K.; Srinivasan, A.; Kailas, S.V. Tailoring surface characteristics of bioabsorbable Mg-Zn-Dy alloy using friction stir processing for improved wettability and degradation behavior. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2021, 12, 1530–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MD, F.K.; Karthik, G.M.; Panigrahi, S.K.; Janaki Ram, G.D. Friction stir processing of QE22 magnesium alloy to achieve ultrafine-grained microstructure with enhanced room temperature ductility and texture weakening. Mater. Charact. 2019, 147, 365–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, R.; Zheng, X.; Liu, Z.; Liu, D.; Qiu, R.; Li, Z.; Liu, Q. Microstructure and texture evolution of an Mg–Gd–Y–Nd–Zr alloy during friction stir processing. J. Alloys Compd. 2016, 659, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rokkala, U.; Bontha, S.; Ramesh, M.R.; Krishna, V.; Srinivasan, A.; Kailas, S. V Tailoring surface characteristics of bioabsorbable Mg-Zn-Dy alloy using friction stir processing for improved wettability and degradation behavior. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2021, 12, 1530–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U. Rokkala, S. Bontha, Influence of friction stir processing on microstructure , mechanical properties and corrosion behaviour of Mg-Zn-Dy alloy, (2023). [CrossRef]

- Dong, B.; Che, X.; Zhang, Z.; Yu, J.; Meng, M. Microstructure evolution and microhardness of Mg-13Gd-4Y e 2Zn- 0. 5Zr alloy via pre-solution and multi-directional forging ( MDF ) process. J. Alloys Compd. 2021, 853, 157066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhao, X.; Li, S.; Yu, J. Strengthening mechanism based on dislocation-twin interaction under room temperature multi-directional forging of AZ80 Mg alloy. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 29, 3656–3672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MD, F.K.; Panigrahi, S.K. Achieving excellent superplasticity in an ultrafine-grained QE22 alloy at both high strain rate and low-temperature regimes. J. Alloys Compd. 2018, 747, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Q.; Yuan, L.; Ma, X.; Zheng, M.; Shan, D.; Guo, B. Strengthening of low-cost rare earth magnesium alloy Mg-7Gd-2Y–1Zn-0.5Zr through multi-directional forging. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2022, 831, 142144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Q.; Yuan, L.; Shan, D.; Guo, B. Study on the microstructure and mechanical properties of ZK60 magnesium alloy with submicron twins and precipitates obtained by room temperature multi-directional forging. J. Mater. Sci. 2023, 58, 13236–13250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaleghi, A.A.; Salevati, M.A.; Sabbaghian, M.; Fekete-Horváth, K.; Drozdenko, D.; Máthis, K.; Akbaripanah, F. Comparing the microstructural and mechanical improvements of AZ80/SiC nanocomposite using DECLE and MDF processes. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2024, 892, 146020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; He, Z.; Fu, P.; Wu, Y.; Peng, L.; Ding, W. Heat treatment and mechanical properties of a high-strength cast Mg-Gd-Zn alloy. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2016, 651, 745–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, S.M.A.K.; Chen, D.L.; Liu, Z.Y.; Ni, D.R.; Wang, Q.Z.; Xiao, B.L.; Ma, Z.Y. Deformation behavior and strengthening mechanisms in a CNT-reinforced bimodal-grained aluminum matrix nanocomposite. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2021, 817, 141370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Praveen, T.R.; Shivananda Nayaka, H.; Swaroop, S.; Gopi, K.R. Strength enhancement of magnesium alloy through equal channel angular pressing and laser shock peening. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2020, 512, 145755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, R.; Luo, Y.; Zuo, A.; Gao, J.; Liu, Q. Texture effect on corrosion behavior of AZ31 Mg alloy in simulated physiological environment. Mater. Lett. 2012, 72, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- G. Song, The Effect of Texture on the Corrosion Behavior of AZ31 Mg Alloy, 64 (2012) 671–679. [CrossRef]

- Maric, M.; Muránsky, O.; Karatchevtseva, I.; Ungár, T.; Hester, J.; Studer, A.; Scales, N.; Ribárik, G.; Primig, S.; Hill, M.R. The effect of cold-rolling on the microstructure and corrosion behaviour of 316L alloy in FLiNaK molten salt. Corros. Sci. 2018, 142, 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Q.; Yi, D.; Wang, H.; Zhang, J.; Xu, J.; Wang, B. Effects of grain size and secondary phase on corrosion behavior and electrochemical performance of Mg-3Al-5Pb-1Ga-Y sacrificial anode. J. Rare Earths 2019, 37, 1341–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahmani, A.; Lotfpour, M.; Taghizadeh, M.; Kim, W. Corrosion behavior of severely plastically deformed Mg and Mg alloys. J. Magnes. Alloy. 2022, 10, 2607–2648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jana, A.; Balla, V.K.; Das, M. In-vitro corrosion and biocompatibility properties of heat treated Mg-4Y-2.25Nd-0.5Zr alloy. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2023, 304, 127873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, V.; Li, W.; Andersson, J.; Li, N. Enhancing grain refinement and corrosion behavior in AZ31B magnesium alloy via stationary shoulder friction stir processing. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2022, 17, 3150–3156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Element | Zn | Nd | Gd | Zr | Mg |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Composition (wt.%) | 3.07 | 1.70 | 1.40 | 0.95 | Balance |

| Sample Condition | Icorr (mA/cm2) | Ecorr (V) | βa | βc | CR (mm/y) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Homogenized | 0.0051 | -1.2799 | 0.0071 | -0.1987 | 0.1165 |

| 3 Pass | 0.0199 | -1.2967 | 0.0285 | -0.2557 | 0.4560 |

| 6 Pass | 0.0109 | -1.1999 | 0.0044 | -0.2606 | 0.2499 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).