Submitted:

17 December 2024

Posted:

17 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods and Approaches for Experiments

2.1. Materials and Solutions

2.2. Microstructure Analysis

2.3. Immersion Weight Loss Test

2.4. Electrochemical Testing

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Study on the Effect of Different Initial Organization States on Corrosion Behavior

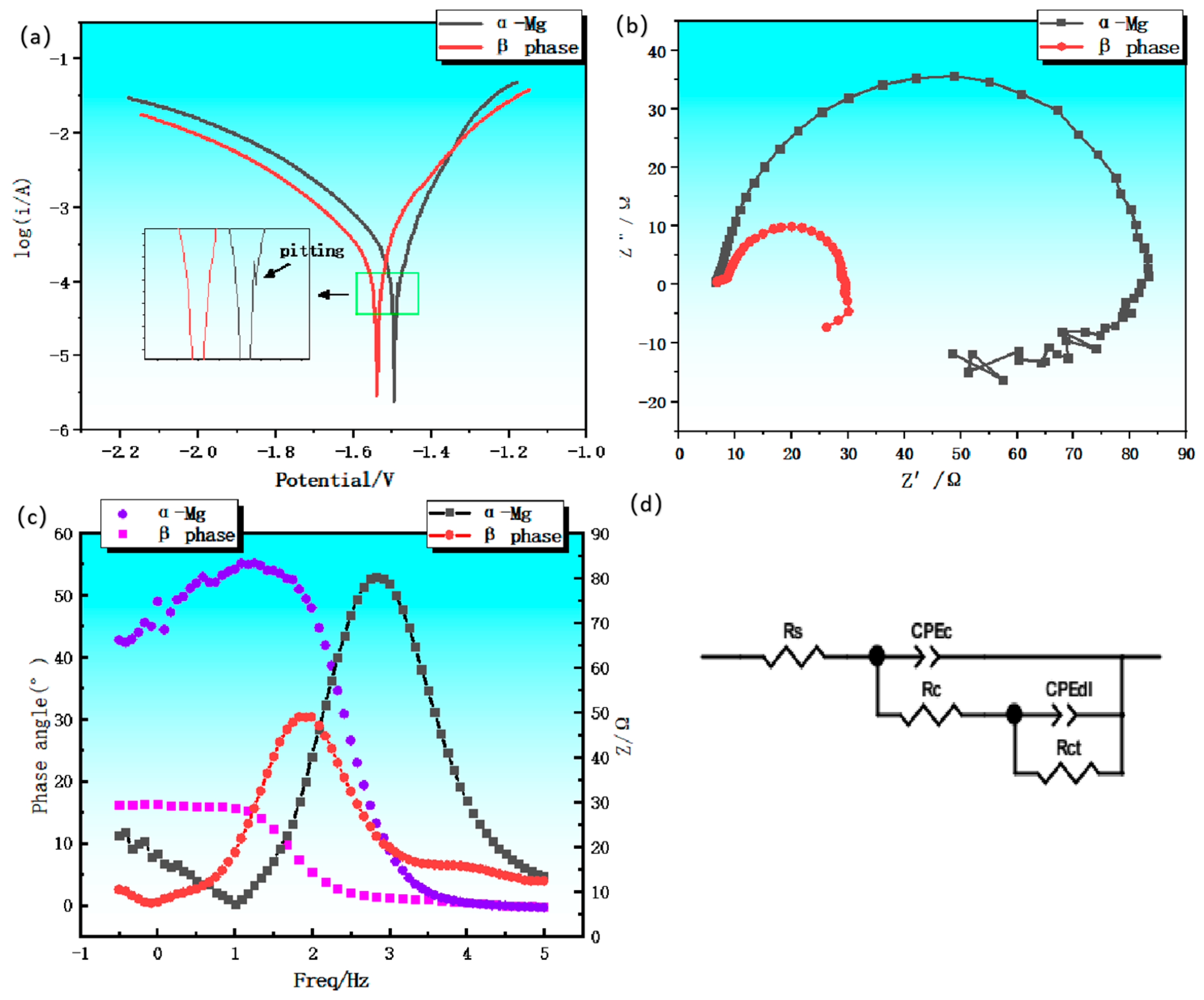

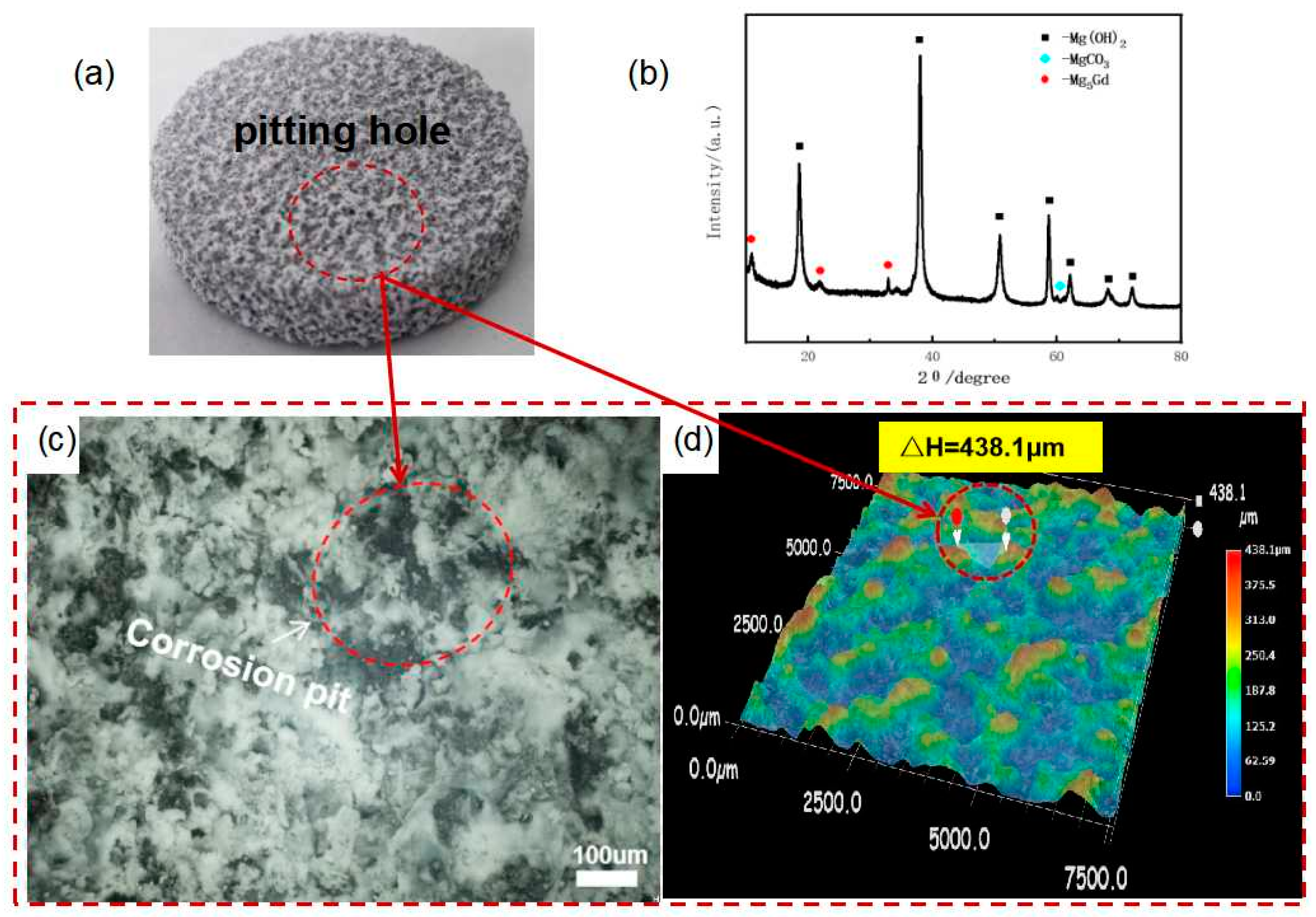

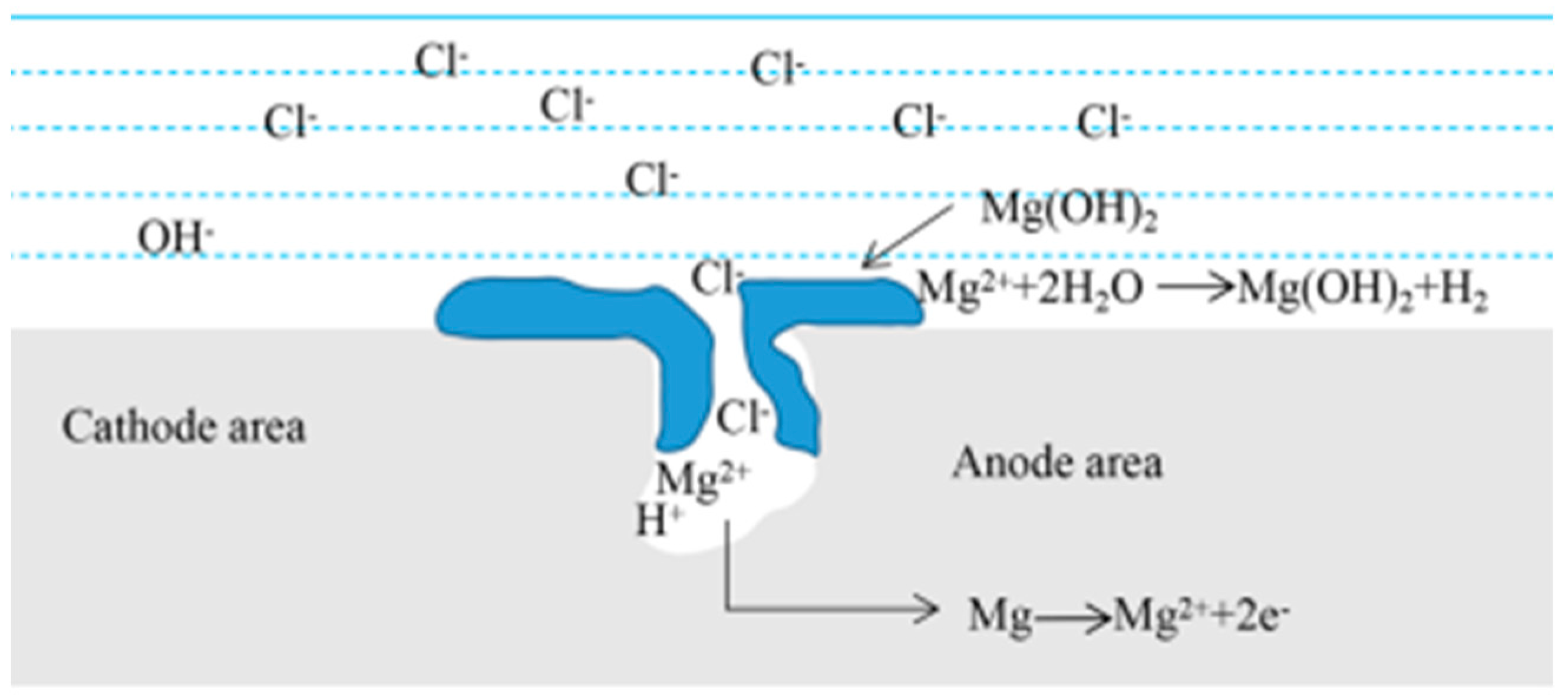

3.2. Study on the Effect of Corrosion Behavior of Rare-Earth-Rich Second Phase Alloys

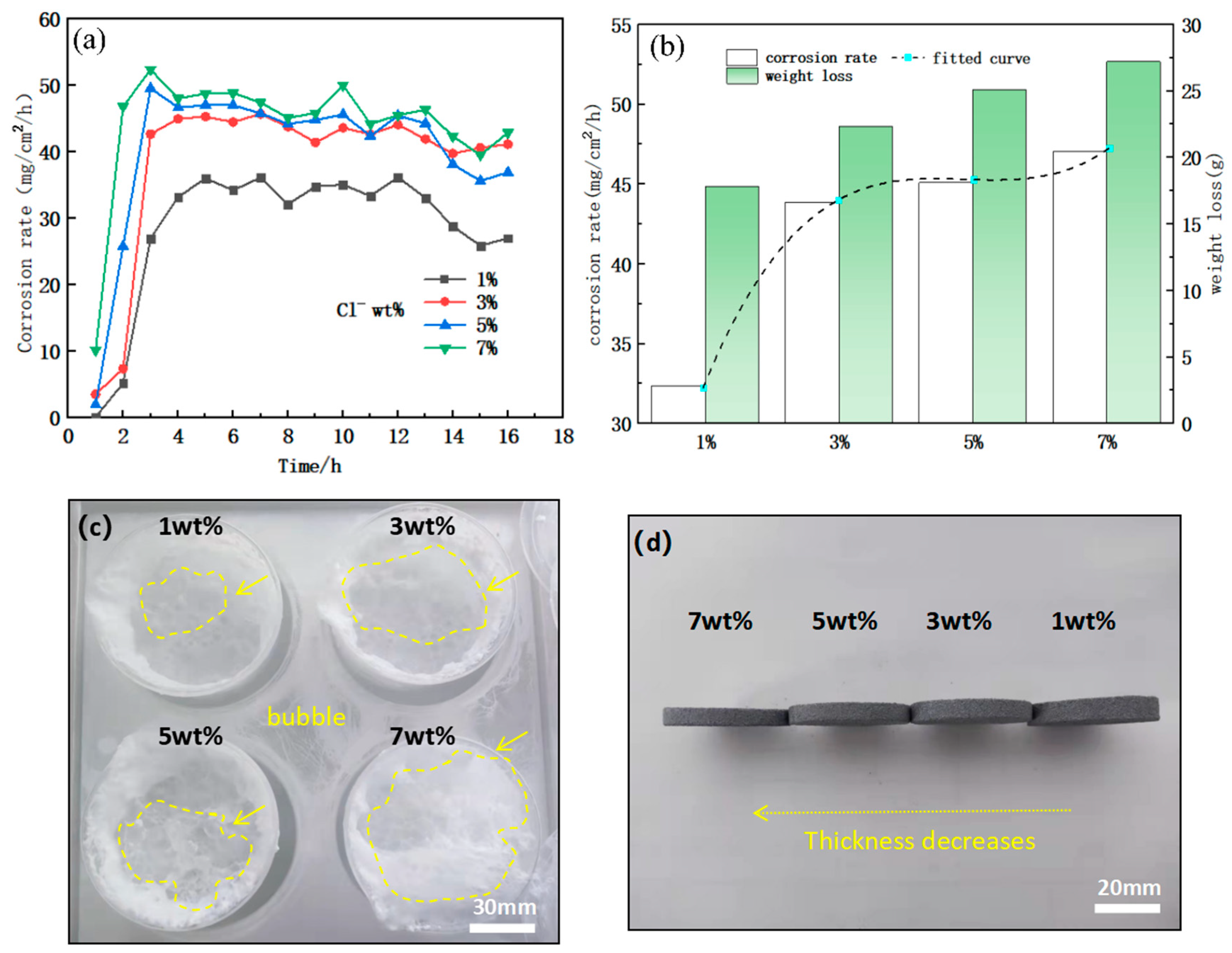

3.3. Study of the Effect of Cl- Concentration on the Corrosion Behavior of Alloys

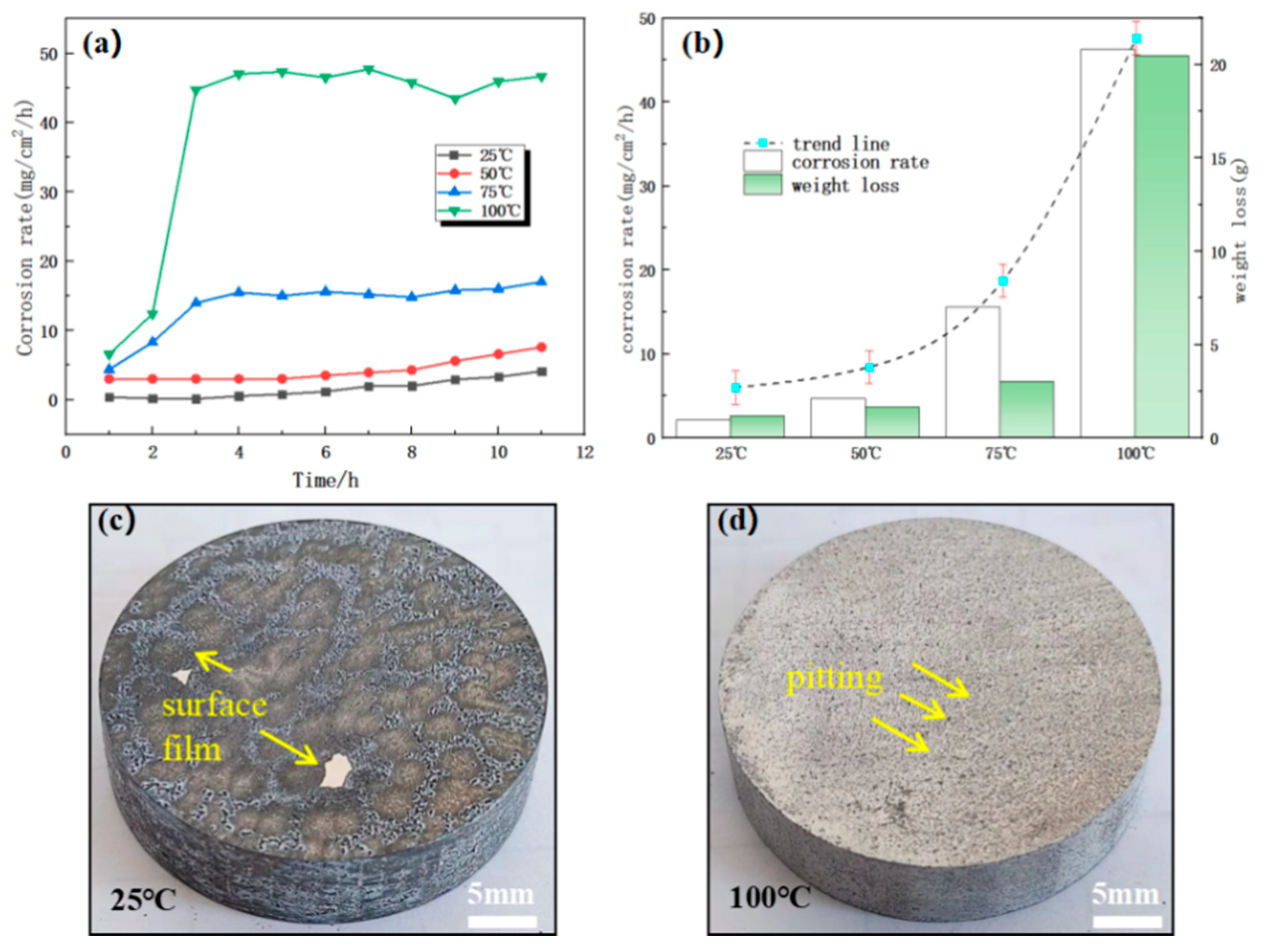

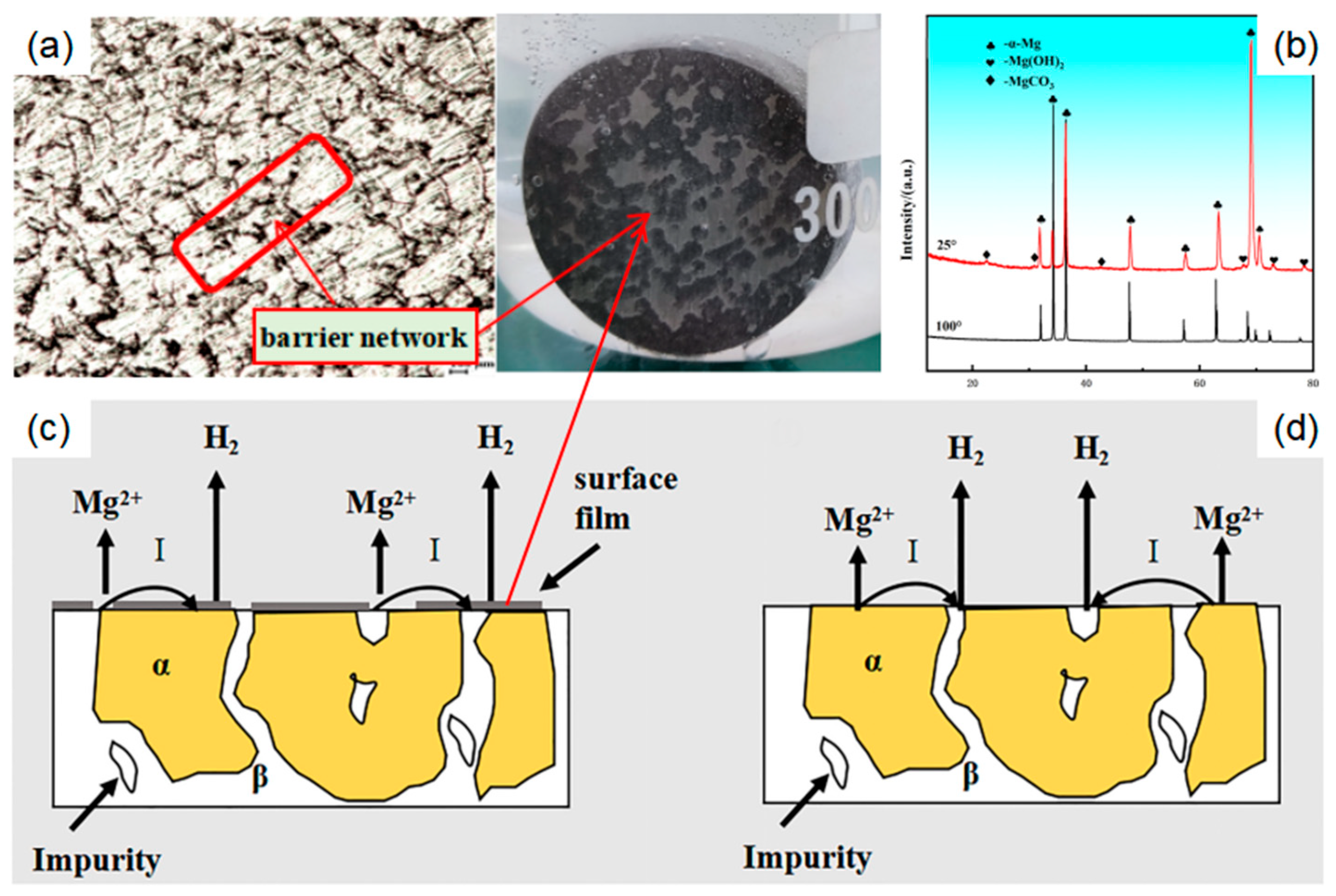

3.4. Study of the Effect of Temperature on the Corrosion Behavior of Alloys

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- The initial state of organization has a great influence on corrosion behavior. During the corrosion reaction, the corrosion product film produced in the deformed state is not easy to be deposited on the surface of the magnesium alloy to hinder the corrosion process, which leads to a substantial increase in the reaction rate after two hours, and the measured weight loss rate is much higher than that of the cast magnesium alloy; from the viewpoint of the initial reaction and the synthesized phenomena of the reaction, the dissolution rate of the transformed soluble magnesium alloy is faster than that of the cast magnesium alloy.

- (2)

- There is a potential difference between the second phase Mg5Gd and the matrix α-Mg, which can form micro-electro-coupling corrosion to accelerate the corrosion rate of Mg-Gd-based soluble magnesium alloy. And for Mg-Gd-based soluble magnesium alloy for a variety of components of the mixture than a single component corrosion rate faster, adding a certain amount of rare earth element Gd is conducive to the dissolution rate.

- (3)

- With the increase of Cl- concentration and temperature, the corrosion rate of Mg-Gd-based soluble magnesium alloys is increasing, but none of them is linearly increasing. When the Cl- concentration is from 1% to 3%, the corrosion rate grows significantly; when the Cl- concentration is from 3% to 7%, the corrosion rate grows slower; for the temperature, when the corrosion temperature is lower than 75 °C, the temperature has less influence on the corrosion rate of the Mg-Gd-based alloy; and when it is more than 75 °C, the increase of the temperature has a significant effect on the corrosion rate.

Acknowledgments

References

- Mordike B L, Ebert T. Magnesium: Properties applications potential[J]. Materials Science and Engineering: A, 2001, 302(1):37-45. [CrossRef]

- R.C. Zeng, L. Y. Cui and W. Ke, Biomedical Magnesium Alloys: Composition, Microstructure and Corrosion, Acta Metallurgica Sinica, 2018, Vol. 54, Issue 9, Pages 1215-1235, ISSN: 0412-1961. [CrossRef]

- Birbilis N, Easton M A, Sudholz A D, et al. On the corrosion of binary magnesium-rare earth alloys[J]. Corrosion Science, 2009, 51(3):683-689. [CrossRef]

- M. J. Anjum, V. Z. Asl, M. Tabish, Q. X. Yang, M. U. Malik, H. Ali, et al. A revieiw on understanding of corrcsion and protection strategies of magnesium and its alloys, Surface Review and Letters, 2022, Vol. 29, Issue 12, ISSN: 0218-625X. [CrossRef]

- J. S. Liao, M. Hotta and N. Yamamoto,Corrosion behavior of fine-grained AZ31B magnesium alloy, Corrosion Science, 2012, Vol. 61, Pages 208-214, ISSN: 0010-938X. [CrossRef]

- J. Sun, W. Du, J. Fu, K. Liu, S. Li, Z. Wang, et al. A review on magnesium alloys for application of degradable fracturing tools, Journal of Magnesium and Alloys, 2022, Vol. 10, Issue 10, Pages 2649-2672, ISSN: 2213-9567. [CrossRef]

- Niu H-Y, Deng K-K, Nie K-B, et al. Microstructure, mechanical properties and corrosion properties of Mg-4Zn-xNi alloys for degradable fracturing ball applications[J]. Journal of Alloys and Compounds, 2019, 787:1290-1300. [CrossRef]

- D. Bian, X. Chu, J. Xiao, Z. Tong, H. Huang, Q. Jia, et al. Design of single-phased magnesium alloys with typically high solubility rare earth elements for biomedical applications: Concept and proof, Bioactive Materials, 2023, Vol. 22, Pages 180-200,ISSN 2452-199X. [CrossRef]

- Y. X. Liu, Research Progress in Effect of Alloying on Electrochemical Corrosion Rates of Mg Alloys, Rare Metal Materials And Engineering, 2021, Vol. 50, Issue 1, Pages 361-372,ISSN: 1002-185X. WOS:000616982300050.

- Zhou M, Liu C, Xu S, et al. Accelerated degradation rate of AZ31 magnesium alloy by copper additions[J]. Materials and Corrosion, 2018, 69(6):760-769. [CrossRef]

- Y. Cai, H. Yan, M. Zhu, K. Zhang, X. Yi and R. Chen,High-temperature oxidation behavior and corrosion behavior of high strength Mg-xGd alloys with high Gd content, Corrosion Science, 2021, Vol. 193, Pages 109872, ISSN: 0010-938X. [CrossRef]

- Q. M. Peng, B. C. Ge, H. Fu, Y. Sun, Q. Zu and J. Y. Huang, Nanoscale coherent interface strengthening of Mg alloys, Nanoscale, 2018, Vol. 10, Issue 37, Pages 18028-18035, ISSN:2040-3364. [CrossRef]

- C. J. Shuai, B. Wang, S. Z. Bin, S. P. Peng and C. D. Gao, Interfacial strengthening by reduced graphene oxide coated with MgO in biodegradable Mg composites, Materials & Design, 2020, Vol. 191, ISSN: 0264-1275. [CrossRef]

- H. L. Huang and W. L. Yang,Corrosion behavior of AZ91D magnesium alloy in distilled water,Arabian Journal OF Chemistry,2020, Vol. 13, Issue 7, Pages 6044-6055,ISSN: 1878-5352. [CrossRef]

- Y. Wang, D. Zhang, S. Zhong, Q. Dai, J. Hua, Y. Luo, et al. Effect of minor Ni addition on the microstructure, mechanical properties and corrosion behavior of Mg–2Gd alloy, Journal of Materials Research and Technology, 2022, Vol. 20, Pages 3735-3749, ISSN: 2238-7854. [CrossRef]

- H. Pan, K. Pang, F. Z. Cui, F. Ge, C. Man, X. Wang, et al. Effect of alloyed Sr on the microstructure and corrosion behavior of biodegradable Mg-Zn-Mn alloy in Hanks' solution, Corrosion Science, 2019, Vol. 157, Pages 420-437, ISSN: 0010-938X. [CrossRef]

- J. Y. Zhang, M. Xu, X. Y. Teng and M. Zuo, Effect of Gd addition on microstructure and corrosion behaviors of Mg-Zn-Y alloy, Journal of Magnesium and Alloys, 2016, Vol. 4, Issue 4, Pages 319-325, ISSN: 2213-9567. [CrossRef]

- L. X. Sun, D. Q. Ma, Y. Liu, L. Liang, Q. W. Qin, S. T. Cheng, et al. Influence of corrosion products on the corrosion behaviors of Mg-Nd-Zn alloys, Materials Today Communications, 2022, Vol. 33, ISSN: 2352-4928. [CrossRef]

- Y. H. Duan, Y. Sun, J. H. He, Z. Z. Guo and D. S. Fang,Corrosion Behavior of As-Cast Pb-Mg-Al Alloys in 3.5% NaCl Solution,Corrosion, 2012, Vol. 68, Issue 9, Pages 822-826, ISSN: 0010-9312. [CrossRef]

- L. Prince, X. Noirfalise, Y. Paint and M. Olivier, Corrosion mechanisms of AZ31 magnesium alloy: Importance of starting pH and its evolution, Materials and Corrosion-werkstoffe Und Korrosion, 2022, Vol. 73, Issue 10, Pages 1615-1630, ISSN:0947-5117. [CrossRef]

- L. Wang, T. Shinohara and B.-P. Zhang, Influence of chloride, sulfate and bicarbonate anions on the corrosion behavior of AZ31 magnesium alloy, Journal of Alloys and Compounds, 2010, Vol. 496, Issue 1, Pages 500-507, ISSN 0925-8388. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhang, X. Wang, Y. Kuang, B. Liu, K. Zhang and D. Fang, Enhanced mechanical properties and degradation rate of Mg-3Zn-1Y based alloy by Cu addition for degradable fracturing ball applications, Materials Letters, 2017, Vol. 195, Pages 194-197, ISSN: 0167-577X. [CrossRef]

- C. Peng, G. Cao, T. Gu, C. Wang, Z. Wang and C. Sun, The effect of dry/wet ratios on the corrosion process of the 6061 Al alloy in simulated Nansha marine atmosphere, Corrosion Science, 2023, Vol. 210, Pages 110840, ISSN: 0010-938X. [CrossRef]

- S. Oh, M. Kim, K. Eom, J. Kyung, D. Kim, E. Cho, et al. Design of Mg–Ni alloys for fast hydrogen generation from seawater and their application in polymer electrolyte membrane fuel cells, International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, 2016, Vol. 41, Issue 10, Pages 5296-5303, ISSN: 0360-3199. [CrossRef]

- Q. Jiang, D. Lu, L. Cheng, N. Liu and B. Hou, The corrosion characteristic and mechanism of Mg-5Y-1.5Nd-xZn-0.5Zr (x = 0, 2, 4, 6 wt.%) alloys in marine atmospheric environment, Journal of Magnesium and Alloys, Volume 12, Issue1, 2024, Pages 139-158, ISSN: 2213-9567. [CrossRef]

- Wang Z, Chen D, Fang Q, et al. Effects of finite temperature on the surface energy in Al alloys from first-principles calculations[J]. Applied Surface Science, 2019, 479:499-505. [CrossRef]

- H. L. Huang and W. L. Yang, Corrosion behavior of AZ91D magnesium alloy in distilled water, Arabian Journal of Chemistry, 2020, Vol. 13, Issue 7, Pages 6044-6055, ISSN:1878-5352. [CrossRef]

- Xie, H., Wang, J., Li, Y., Song, J., Hu, H., Qin, L., et al. Fast shot speed induced microstructure and mechanical property evolution of high pressure die casting Mg-Al-Zn-RE alloys, Journal of Materials Processing Technology, 2024, Vol. 331, Pages 118523, ISSN: 0924-0136. [CrossRef]

- Zou, J., Ma, L., Zhu, Y., Qin, L., & Yuan, Y,Gradient microstructure and superior strength–ductility synergy of AZ61 magnesium alloy bars processed by radial forging with different deformation temperatures, Journal of Materials Science & Technology, 2024, Vol. 170, Pages 65-77, ISSN: 0010-938X. [CrossRef]

- Qin, L., Du, W., Cipiccia, S., Bodey, A. J., Rau, C., & Mi, J.,Synchrotron X-ray operando study and multiphysics modelling of the solidification dynamics of intermetallic phases under electromagnetic pulses. Acta Materialia, 2024, Vol. 265, 119593, ISSN 2213-9567. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z., Khong, J. C., Koe, B., Luo, S., Huang, S., Qin, L., ... & Mi, J. (2021). Multiscale characterization of the 3D network structure of metal carbides in a Ni superalloy by synchrotron X-ray microtomography and ptychography. Scripta Materialia, 2021, Volume 193, Pages 71-76, ISSN 1359-6462. [CrossRef]

- Huang, S., Luo, S., Qin, L., Shu, D., Sun, B., Lunt, A. J., ... & Mi, J. (2022). 3D local atomic structure evolution in a solidifying Al-0.4 Sc dilute alloy melt revealed in operando by synchrotron X-ray total scattering and modelling. Scripta Materialia, 2022, Volume 211, 114484, ISSN 1359-6462. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., Huang, T., Zhou, Z., Li, M., Tan, L., Gan, B., ... & Liu, L. (2021). Variation of Homogenization Pores during Homogenization for Nickel-Based Single-Crystal Superalloys. Advanced Engineering Materials, 2021, Volume 23(6), 2001547. [CrossRef]

- Qin, L., Shen, J., Feng, Z., Shang, Z., & Fu, H. (2014). Microstructure evolution in directionally solidified Fe–Ni alloys under traveling magnetic field. Materials Letters, 2014, Volume 115, Pages 155-158, ISSN 0167-577X. [CrossRef]

- Ehsan Gerashi, Reza Alizadeh, Terence G. Langdon, Effect of crystallographic texture and twinning on the corrosion behavior of Mg alloys: A review, Journal of Magnesium and Alloys, 2022, Volume 10, Issue 2, Pages 313-325,ISSN 2213-9567. [CrossRef]

- L. Li, W. Liu, F. Qi, D. Wu and Z. Zhang, Effects of deformation twins on microstructure evolution, mechanical properties and corrosion behaviors in magnesium alloys - A review, Journal of Magnesium and Alloys, 2022, Vol. 10, Issue 9, Pages 2334-2353, ISSN 2213-9567. [CrossRef]

- Y. Lu, J. Wang, X. Li, W. Li, R. Li and D. Zhou,Effects of pre-deformation on the microstructures and corrosion behavior of 2219 aluminum alloys,Materials Science and Engineering: A, 2018, Vol. 723, Pages 204-211, ISSN: 0921-5093. [CrossRef]

- B. Feng, G. Liu, P. Yang, S. Huang, D. Qi, P. Chen, et al. Different role of second phase in the micro-galvanic corrosion of WE43 Mg alloy in NaCl and Na2SO4 solution, Journal of Magnesium and Alloys, 2022, Vol. 10, Issue 6, Pages 1598-1608, ISSN: 2213-9567. [CrossRef]

- H.R. J. Nodooshan, W. Liu, G. Wu, Y. Rao, C. Zhou, S. He, et al. Effect of Gd content on microstructure and mechanical properties of Mg–Gd–Y–Zr alloys under peak-aged conditio,Materials Science and Engineering: A, 2014, Vol. 615, Pages 79-86, ISSN: 0921-5093. [CrossRef]

- H. Yu, Y. Hongge, C. Jihua, S. Bin, Z. Yi, S. Yanjin, et al. Effects of minor Gd addition on microstructures and mechanical properties of the high strain-rate rolled Mg–Zn–Zr alloys, Journal of Alloys and Compounds, 2014, Vol. 586, Pages 757-765, ISSN: 0925-8388. [CrossRef]

- D. Filotás, B.M. Fernández-Pérez, L. Nagy, G. Nagy, R.M. Souto, Investigation of anomalous hydrogen evolution from anodized magnesium using a polarization routine for scanning electrochemical microscopy, Journal of Electroanalytical Chemistry, 2021, Vol. 895, Pages 115538, ISSN:1572-6657. [CrossRef]

- S. Oh, M. Kim, K. Eom, J. Kyung, D. Kim, E. Cho, et al. Design of Mg–Ni alloys for fast hydrogen generation from seawater and their application in polymer electrolyte membrane fuel cells, International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, 2016, Vol. 41, Issue 10, Pages 5296-5303, ISSN:0360-3199. [CrossRef]

- L. H. Yang, C. G. Lin, H. P. Gao, W. C. Xu, Y. T. Li, B. R. Hou, et al. Corrosion Behaviour of AZ63 Magnesium Alloy in Natural Seawater and 3.5 wt.% NaCl Aqueous Solution, INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF ELECTROCHEMICAL SCIENCE, 2018 ,Vol. 13, Issue 8, Pages 8084-8093, ISSN:1452-3981. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhu, C. Hao, Z. Li, J. Zou, L. Qin, Y. Niu, et al. First-principles study of binary and ternary phases in Mg-Gd-Ni alloys,Physica B: Condensed Matter, 2024, Vol. 685, Pages 416065, ISSN: 0921-4526. [CrossRef]

- M. Yamasaki, S. Izumi, Y. Kawamura and H. Habazaki, Corrosion and passivation behavior of Mg–Zn–Y–Al alloys prepared by cooling rate-controlled solidification, Applied Surface Science, 2011, Vol. 257, Issue 19, Pages 8258-8267, ISSN: 0169-4332. [CrossRef]

| Element | Gd | Ni | Cu | Fe | Si | Mg |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Content(wt%) | 1.85 | 0.15 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 | Balance |

| experimental material | Temperature /°C | KCl concentration /% | Timing/h | Corresponding results analysis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mg-Gd alloys in cast form | 93 | 3 | 12 | Figure 3a,Figure 4 |

| Metamorphic Mg-Gd alloys | 93 | 3 | 12 | Figure 3b,Figure 4 |

| matrix phase α-Mg | 93 | 3 | 8 | Figure 6 |

| the second phase Mg5Gd | 93 | 3 | 8 | Figure 6 |

| Metamorphic Mg-Gd alloys | 93 | 1, 3, 5, 7 | 16 | Figure 8 |

| Metamorphic Mg-Gd alloys | 25, 50, 75, 100 | 3 | 11 | Figure 11 |

| Sample | 0 min | 1 h | 1.5 h |

|---|---|---|---|

| α-Mg | -1.705 | -1.662 | -1.661 |

| Mg5Gd | -1.684 | -1.651 | -1.647 |

| Sample | RS[Ω/CM-2] | RCT[Ω/CM-2] | YDL[ΩCM-2SN] | NDL |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| α-Mg | 6.757±0.08 | 79.41 | (1.96±0.03)×10-5 | 0.915±0.003 |

| Mg5Gd | 5.862±0.08 | 27.44 | (0.07±0.03)×10-5 | 0.883±0.003 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).