Submitted:

12 September 2025

Posted:

19 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Temperature Monitoring and Leather Degradation

Temperature Monitoring and Process Control

2.2. Microbial Characterisation: Bacterial Community Composition

2.2.1. Rarefaction, Alpha and Beta Diversity

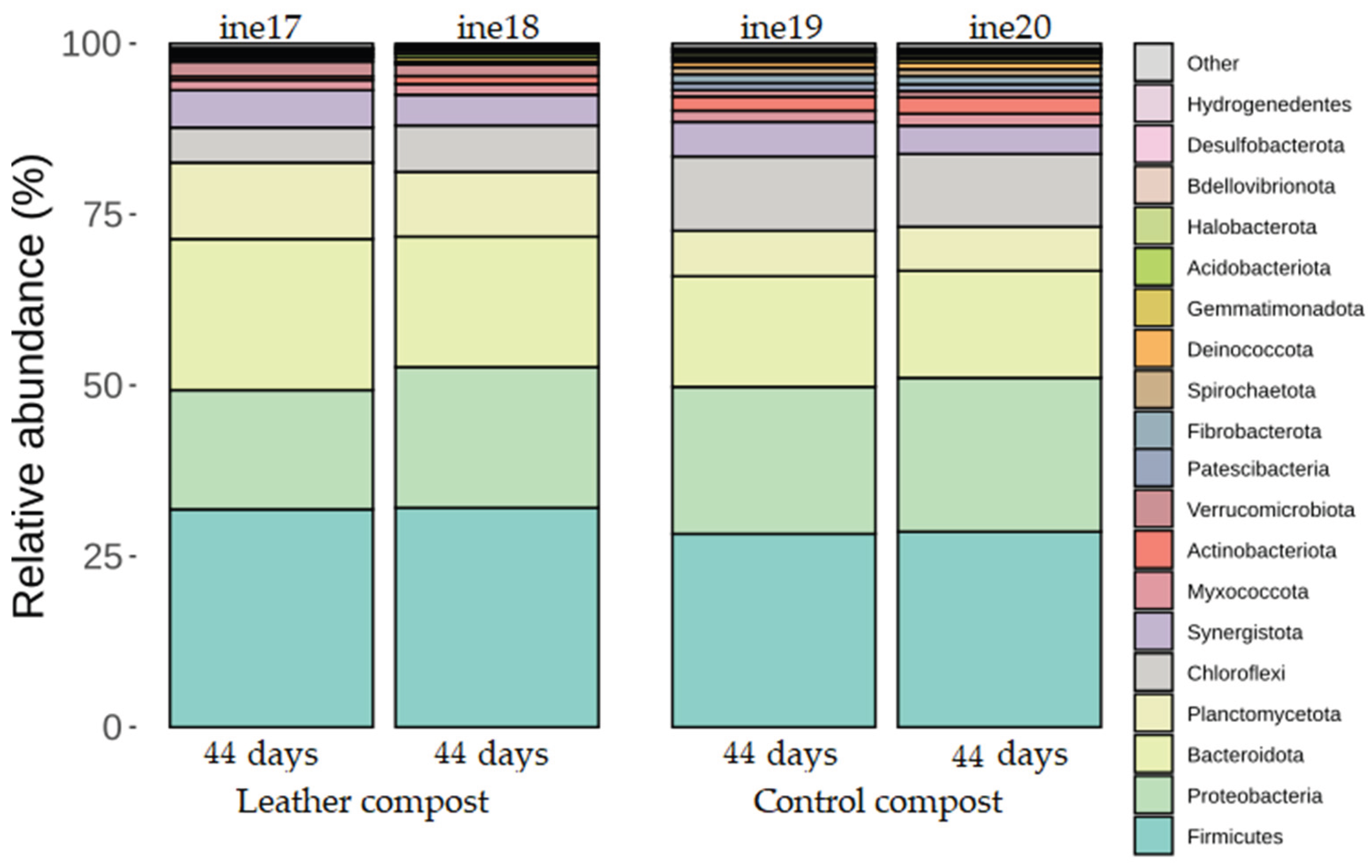

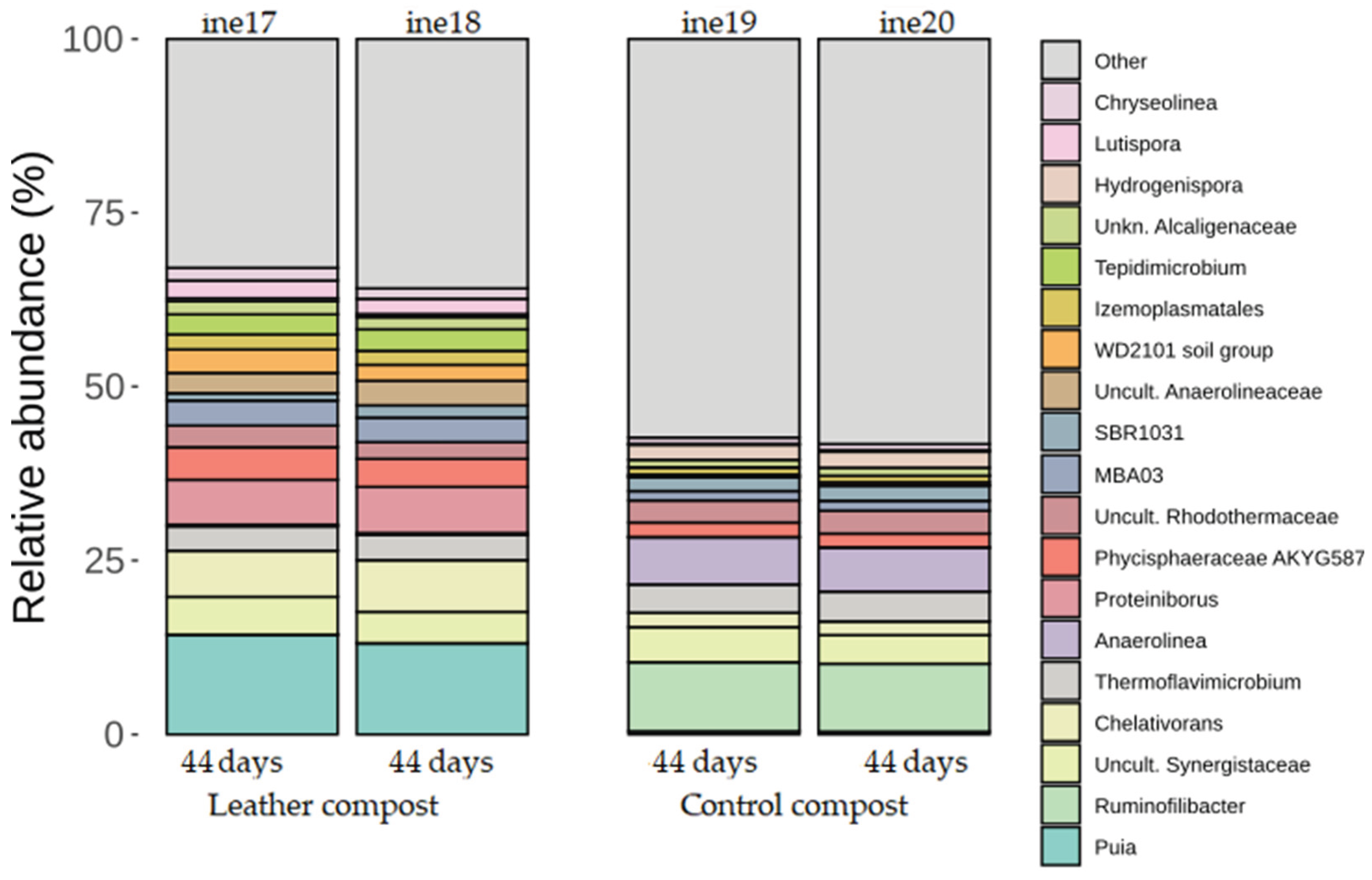

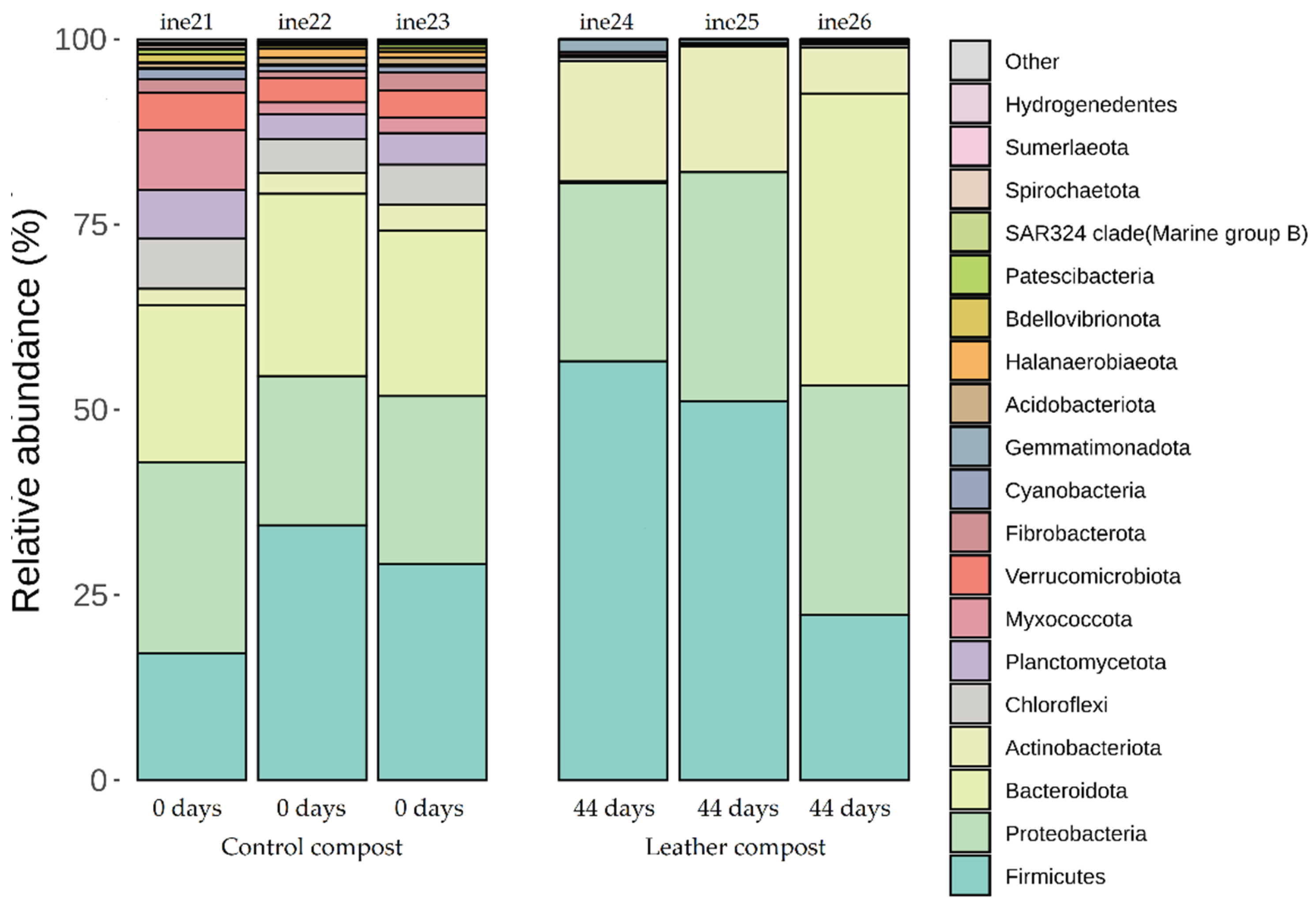

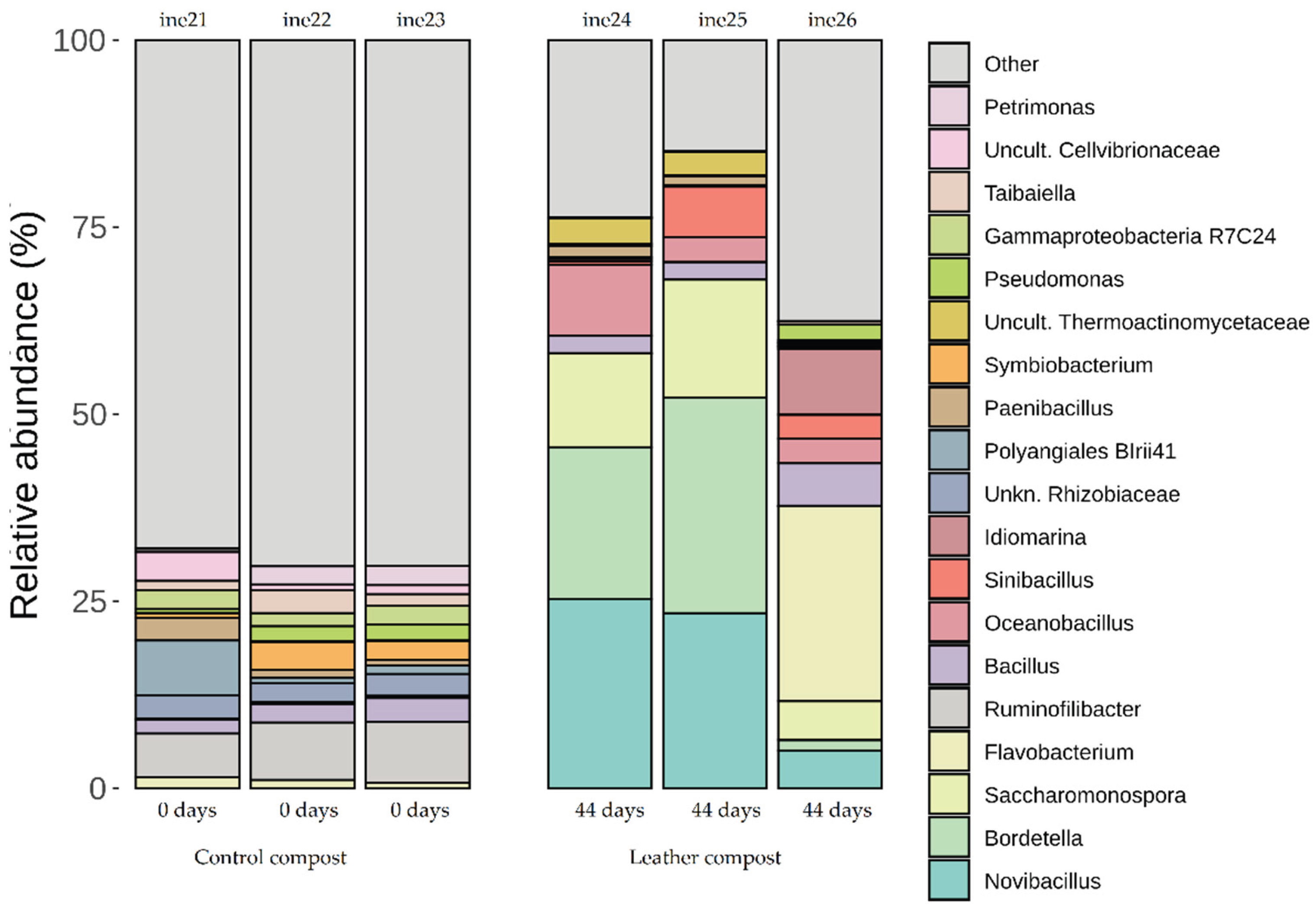

2.2.2. Taxonomic Distribution at Phylum and Genus Levels

2.3. Microbiota Characterisation: Fungal Community Dynamics

2.3.1. Rarefaction, Alpha and Beta Diversity

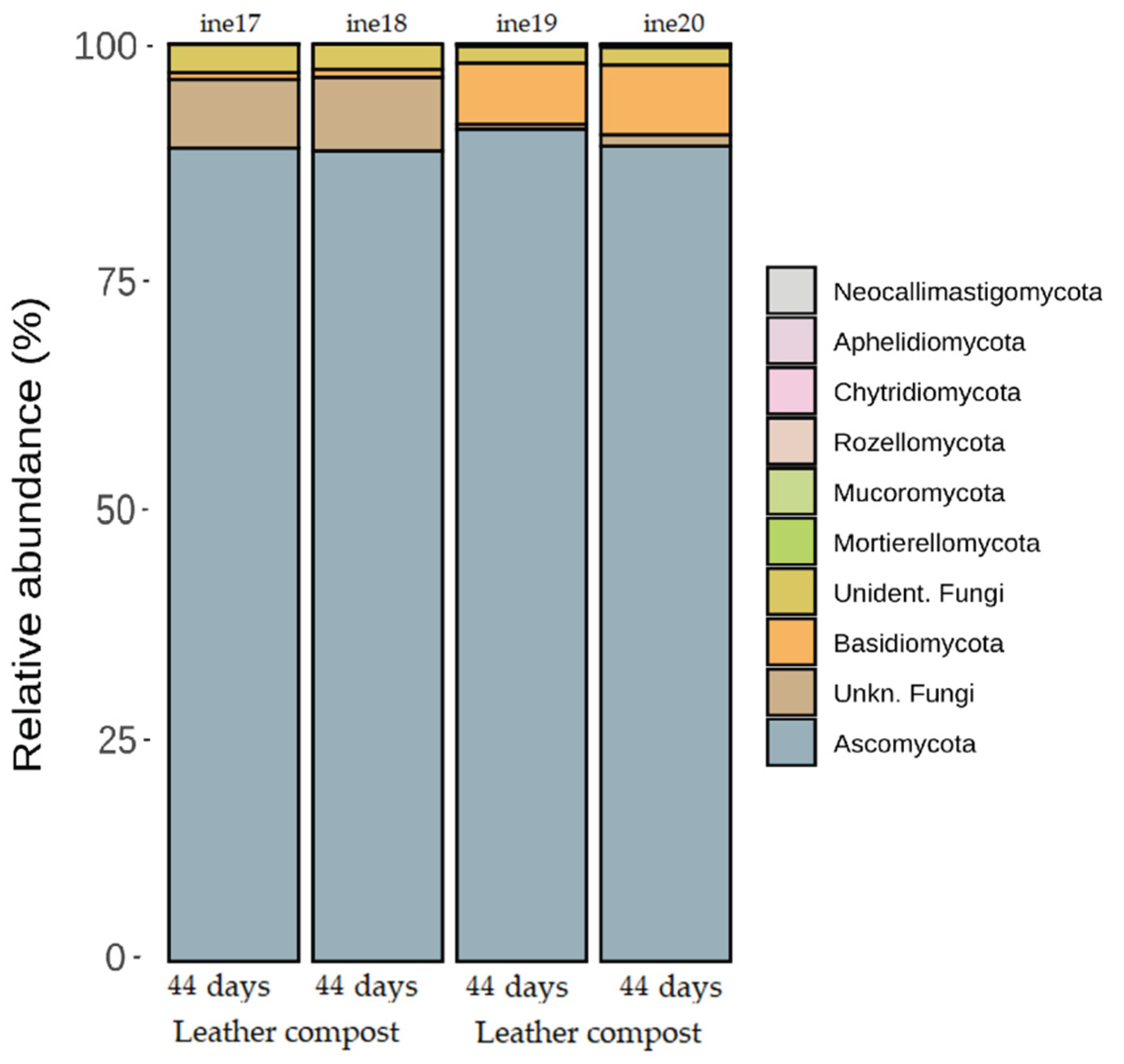

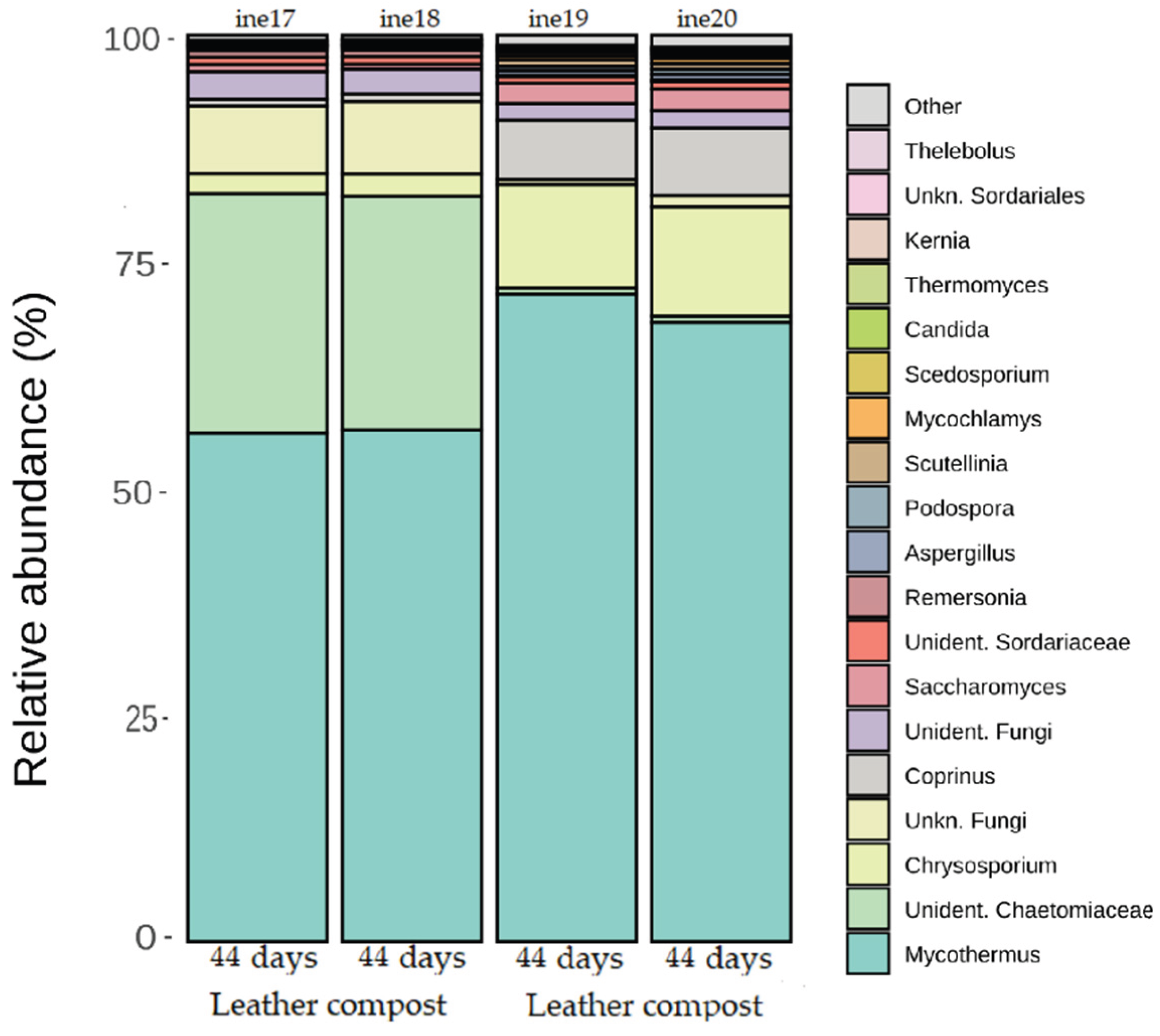

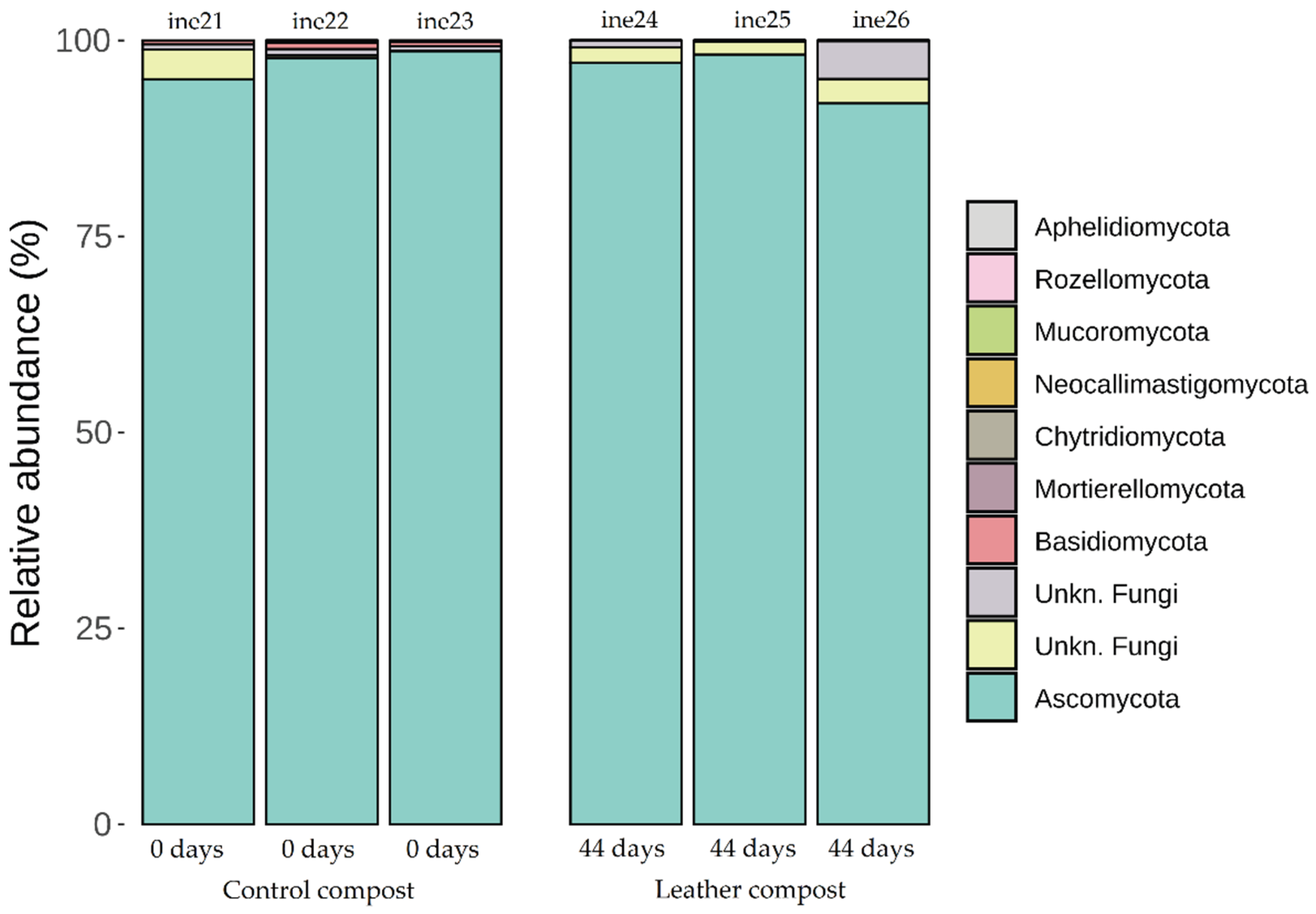

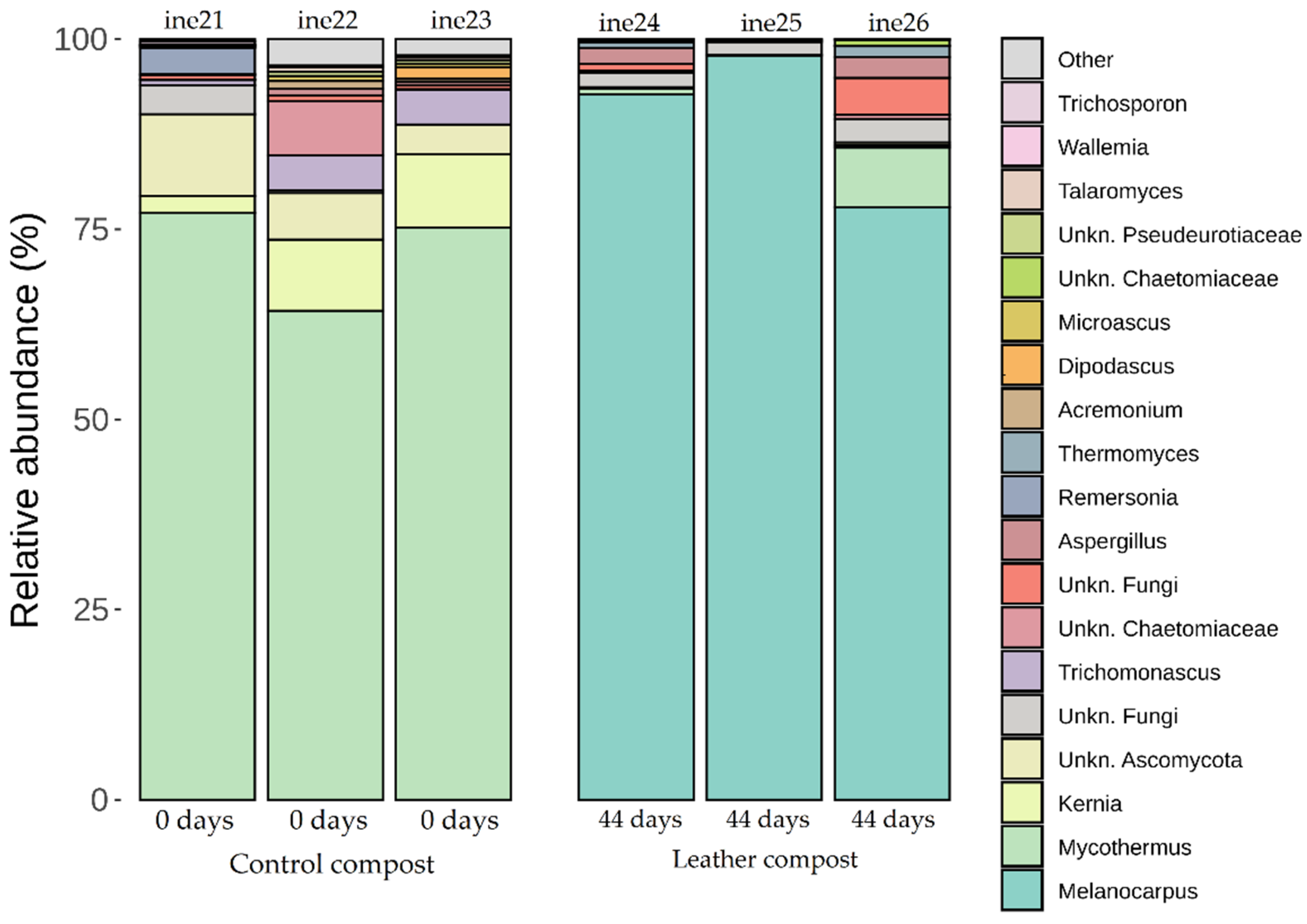

2.3.2. Taxonomic Distribution at Phylum and Genus Levels

2.4. Cultivable Bacterial and Fungal Species Identification

2.5. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) & Gravimetric Analysis: Leather Analysis

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Composting Leather Biodegradation: Small- and Large-Scale Approaches

4.2. Metagenomic DNA Extraction and Sequencing

4.3. Bioinformatics and Statistical Analysis

4.4. Cultivable Bacterial and Fungal Species Identification

4.5. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) and Gravimetric Analysis: Leather Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Verma, S.K.; Sharma, P.C. Current trends in solid tannery waste management. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2023, 43, 805–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrzesińska-Jędrusiak, E.; Czarnecki, M.; Kazimierski, P.; Bandrów, P.; Szufa, S. The Circular Economy in the Management of Waste from Leather Processing. Energies 2023, 16, 564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- C Chojnacka, K.; Skrzypczak, D.; Mikula, K.; Witek-Krowiak, A.; Izydorczyk, G.; Kuligowski, K.; Bandrów, P.; Kułażyński, M. Progress in sustainable technologies of leather wastes valorization as solutions for the circular economy. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 313, 127902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomasset, A.; Benayoun, S. Review: Leather sustainability, an industrial ecology in process. J. Ind. Ecol. 2024, 28, 1842–1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abo Elazm, A.; Zaki, S.; Abd El-Rahim, W.M.; Rostom, M.; Sabbor, A.T.; Moawad, H.; Sedik, M.Z. Bioremediation of Hexavalent Chromium Widely Discharged in Leather Tanning Effluents. Egypt. J. Chem. 2020, 63, 2201–2212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakshi, A.; Panigrahi, A.K. Chromium Contamination in Soil and Its Bioremediation: An Overview. In Advances in Bioremediation and Phytoremediation for Sustainable Soil Management; Malik, J.A., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 229–248. ISBN 978-3-030-89984-4. [Google Scholar]

- Biškauskaitė, R.; Valeika, V. Wet Blue Enzymatic Treatment and Its Effect on Leather Properties and Post-Tanning Processes. Materials 2023, 16, 2301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ambone, T.; Joseph, S.; Deenadayalan, E.; Mishra, S.; Jaisankar, S.; Saravanan, P. Polylactic Acid (PLA) Biocomposites Filled with Waste Leather Buff (WLB). J. Polym. Environ. 2017, 25, 1099–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, R.J.; Agostini, D.L.S.; Cabrera, F.C.; Budemberg, E.R.; Job, A.E. Recycling Leather Waste: Preparing and Studying on the Microstructure, Mechanical, and Rheological Properties of Leather Waste/Rubber Composite. Polym. Compos. 2015, 36, 2275–2281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayele, M.; Limeneh, D.Y.; Tesfaye, T.; Mengie, W.; Abuhay, A.; Haile, A.; Gebino, G. A Review on Utilization Routes of the Leather Industry Biomass. Adv. mater. sci. eng. 2021, 1503524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigueto, C.V.T.; Rosseto, M.; Krein, D.D.C.; Ostwald, B.E.P.; Massuda, L.A.; Zanella, B.B.; Dettmer, A. Alternative uses for tannery wastes: a review of environmental, sustainability, and science. J. Leather Sci. Eng. 2020, 2, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moktadir, Md.A.; Ahmadi, H.B.; Sultana, R.; Zohra, F.-T.-; Liou, J.J.H.; Rezaei, J. Circular economy practices in the leather industry: A practical step towards sustainable development. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 251, 119737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, É.; de Aquim, P.M.; Gutterres, M. Environmental assessment of water, chemicals and effluents in leather post-tanning process: A review. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2021, 89, 106597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokač, T.; Valinger, D.; Benković, M.; Jurina, T.; Gajdoš Kljusurić, J.; Radojčić Redovniković, I.; Jurinjak Tušek, A. Application of Optimization and Modeling for the Composting Process Enhancement. Processes 2022, 10, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goswami, L.; Mukhopadhyay, R.; Bhattacharya, S.S.; Das, P.; Goswami, R. Detoxification of chromium-rich tannery industry sludge by Eudrillus eugeniae: Insight on compost quality fortification and microbial enrichment. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 266, 472–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vico, A.; Maestre-Lopez, M.I.; Arán-Ais, F.; Orgilés-Calpena, E.; Bertazzo, M.; Marhuenda-Egea, F.C. Assessment of the Biodegradability and Compostability of Finished Leathers: Analysis Using Spectroscopy and Thermal Methods. Polymers 2024, 16, 1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alugoju, P.; Rao, C.S.V.; Babu, R.; Thankappan, R. Assessment of Biodegradability of Synthetic Tanning Agents Used in Leather Tanning Process. International Journal of Engineering and Technology 2011, 3, 302–308. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, D.; Yao, C.; Meng, Q.; Zhao, R.; Wei, Z. Speciation, toxicity mechanism and remediation ways of heavy metals during composting: A novel theoretical microbial remediation method is proposed. J. Environ. Manage. 2020, 272, 111109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, W.; Liu, X.; Wang, Y. Amphoteric functional polymers for leather wet finishing auxiliaries: A review. Polym. Adv. Technol. 2021, 32, 1951–1964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieczorek, D.; Gendaszewska, D.; Miśkiewicz, K.; Słubik, A.; Ławińska, K. Biotransformation of Protein-Rich Waste by Yarrowia Lipolytica IPS21 to High-Value Products—Amino Acid Supernatants. Microbiol. Spectr. 2023, 11, e02749–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sardroudi, N.P.; Sorolla, S.; Casas, C.; Bacardit, A. A Study of the Composting Capacity of Different Kinds of Leathers, Leatherette and Alternative Materials. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosu, L.; Varganici, C.-D.; Crudu, A.-M.; Rosu, D. Influence of different tanning agents on bovine leather thermal degradation. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2018, 134, 583–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Codreanu (Manea), A.-M.N.; Stefan, D.S.; Kim, L.; Stefan, M. Depollution of Polymeric Leather Waste by Applying the Most Current Methods of Chromium Extraction. Polymers 2024, 16, 1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccin, J.S.; Feris, L.A.; Cooper, M.; Gutterres, M. Dye Adsorption by Leather Waste: Mechanism Diffusion, Nature Studies, and Thermodynamic Data. J. Chem. Eng. Data 2013, 58, 873–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halldórsdóttir, H.H.; Williams, R.; Greene, E.M.; Taylor, G. Rapid deterioration in buried leather: archaeological implications. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 3762–3770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, M.A.; Butt, M.Q.S.; Afroz, A.; Rasul, F.; Irfan, M.; Sajjad, M.; Zeeshan, N. Approach towards sustainable leather: Characterization and effective industrial application of proteases from Bacillus sps. for ecofriendly dehairing of leather hide. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 266, 131154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alibardi, L.; Cossu, R. Pre-treatment of tannery sludge for sustainable landfilling. Waste Manag. 2016, 52, 202–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanagaraj, J.; Panda, R.C.; Kumar, M.V. Trends and advancements in sustainable leather processing: Future directions and challenges—A review. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 104379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blair, E.M.; Dickson, K.L.; O’Malley, M.A. Microbial communities and their enzymes facilitate degradation of recalcitrant polymers in anaerobic digestion. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2021, 64, 100–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biyada, S.; Merzouki, M.; Dėmčėnko, T.; Vasiliauskienė, D.; Ivanec-Goranina, R.; Urbonavičius, J.; Marčiulaitienė, E.; Vasarevičius, S.; Benlemlih, M. Microbial community dynamics in the mesophilic and thermophilic phases of textile waste composting identified through next-generation sequencing. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 23624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finore, I.; Feola, A.; Russo, L.; Cattaneo, A.; Di Donato, P.; Nicolaus, B.; Poli, A.; Romano, I. Thermophilic bacteria and their thermozymes in composting processes: a review. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 2023, 10, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiniger, B.; Hupfauf, S.; Insam, H.; Schaum, C. Exploring Anaerobic Digestion from Mesophilic to Thermophilic Temperatures—Operational and Microbial Aspects. Fermentation 2023, 9, 798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nnaji, N.D.; Anyanwu, C.U.; Miri, T.; Onyeaka, H. Mechanisms of Heavy Metal Tolerance in Bacteria: A Review. Sustainability 2024, 16, 11124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azarbad, H.; van Gestel, C.A.M.; Niklińska, M.; Laskowski, R.; Röling, W.F.M.; van Straalen, N.M. Resilience of Soil Microbial Communities to Metals and Additional Stressors: DNA-Based Approaches for Assessing “Stress-on-Stress” Responses. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pal, A.; Paul, A.K. Microbial extracellular polymeric substances: central elements in heavy metal bioremediation. Indian J. Microbiol. 2008, 48, 49–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, D.; Jacquiod, S.; Herschend, J.; Wei, S.; Nesme, J.; Sørensen, S.J. Construction of Simplified Microbial Consortia to Degrade Recalcitrant Materials Based on Enrichment and Dilution-to-Extinction Cultures. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 10, 3010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Zhao, J.; Achinas, S.; Zhang, Z.; Krooneman, J.; Euverink, G.J.W. The biomethanation of cow manure in a continuous anaerobic digester can be boosted via a bioaugmentation culture containing Bathyarchaeota. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 745, 141042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Chen, J.; Zhou, S. Novibacillus thermophilus gen. nov., sp. nov., a Gram-staining-negative and moderately thermophilic member of the family Thermoactinomycetaceae. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2015, 65, 2591–2597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, W.; Lin, J.; Wang, W.; Huang, H.; Li, S. Biodegradation of aliphatic and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons by the thermophilic bioemulsifier-producing Aeribacillus pallidus strain SL-1. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2020, 189, 109994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomez del Pulgar, E.M.; Saadeddin, A. The cellulolytic system of Thermobifida fusca. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2014, 40, 236–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McFall, A.; Coughlin, S.A.; Hardiman, G.; Megaw, J. Strategies for biofilm optimization of plastic-degrading microorganisms and isolating biofilm formers from plastic-contaminated environments. Sustain. Microbiol. 2024, 1, qvae012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M.A.; Haroun, B.M.; Amara, A.A.; Serour, E.A. Production and Characterization of Keratinolytic Protease from New Wool-Degrading Bacillus Species Isolated from Egyptian Ecosystem. BioMed Res. Int. 2013, 2013, 175012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akram, F.; Haq, I. ul; Hayat, A.K.; Ahmed, Z.; Jabbar, Z.; Baig, I.M.; Akram, R. Keratinolytic Enzyme from a Thermotolerant Isolate Bacillus sp. NDS-10: An Efficient Green Biocatalyst for Poultry Waste Management, Laundry and Hide-dehairing Applications. Waste Biomass Valor 2021, 12, 5001–5018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McPhillips, K.; Waters, D.M.; Parlet, C.; Walsh, D.J.; Arendt, E.K.; Murray, P.G. Purification and Characterisation of a β-1,4-Xylanase from Remersonia Thermophila CBS 540.69 and Its Application in Bread Making. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2014, 172, 1747–1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van den Brink, J.; Facun, K.; de Vries, M.; Stielow, J.B. Thermophilic growth and enzymatic thermostability are polyphyletic traits within Chaetomiaceae. Fungal Biol. 2015, 119, 1255–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, Z.; Wang, X.; Wang, M.; Chai, L.; Wang, X.; Liu, D.; Shen, Q. Bacterial ecosystem functioning in organic matter biodegradation of different composting at the thermophilic phase. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 317, 123990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radhika, V.; Subramanian, S.; Natarajan, K.A. Bioremediation of zinc using Desulfotomaculum nigrificans: Bioprecipitation and characterization studies. Water Res. 2006, 40, 3628–3636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, A.B.; Singh, S.; Patel, A.; Jain, K.; Amin, S.; Madamwar, D. Synergistic biodegradation of phenanthrene and fluoranthene by mixed bacterial cultures. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 284, 115–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Wang, D.; Tang, W.; Wang, L.; Li, Q.; Lu, Z.; Liu, H.; Zhong, Y.; He, T.; Guo, S. Phytoremediation of cadmium-polluted soil assisted by D-gluconate-enhanced Enterobacter cloacae colonization in the Solanum nigrum L. rhizosphere. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 732, 139265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiiskinen, L.-L.; Palonen, H.; Linder, M.; Viikari, L.; Kruus, K. Laccase from Melanocarpus albomyces binds effectively to cellulose. FEBS Lett. 2004, 576, 251–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobrowolski, R.; Szcześ, A.; Czemierska, M.; Jarosz-Wikołazka, A. Studies of cadmium(II), lead(II), nickel(II), cobalt(II) and chromium(VI) sorption on extracellular polymeric substances produced by Rhodococcus opacus and Rhodococcus rhodochrous. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 225, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Efe, D. Potential Plant Growth-Promoting Bacteria with Heavy Metal Resistance. Curr. Microbiol. 2020, 77, 3861–3868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desoky, E.-S.M.; Merwad, A.-R.M.; Semida, W.M.; Ibrahim, S.A.; El-Saadony, M.T.; Rady, M.M. Heavy metals-resistant bacteria (HM-RB): Potential bioremediators of heavy metals-stressed Spinacia oleracea plant. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2020, 198, 110685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Brien, S.; Hodgson, D.J.; Buckling, A. Social evolution of toxic metal bioremediation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proc. R. Soc. B 2014, 281, 20140858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Zheng, Y.; Yu, X. Flocculation-bio-treatment of heavy metals-vacuum preloading of the river sediments. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2020, 201, 110810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, B.; Lv, L.; Pang, C.; Ye, F.; Shang, C. Optimization of Growth Conditions of Acinetobacter Sp. Cr1 for Removal of Heavy Metal Cr Using Central Composite Design. Curr Microbiol 2021, 78, 316–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.; Wang, Z.; Bhatnagar, A.; Jeyakumar, P.; Wang, H.; Wang, Y.; Li, X. Microorganisms-Carbonaceous Materials Immobilized Complexes: Synthesis, Adaptability and Environmental Applications. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 416, 125915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, A.; Gupta, A. Evaluation of Acinetobacter Sp. B9 for Cr (VI) Resistance and Detoxification with Potential Application in Bioremediation of Heavy-Metals-Rich Industrial Wastewater. Environ Sci Pollut Res 2013, 20, 6628–6637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Che Hussian, C.H.A.; Leong, W.Y. Thermostable enzyme research advances: a bibliometric analysis. J. Genet. Eng. Biotechnol. 2023, 21, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, B.; Shukla, P. A comparative analysis of heavy metal bioaccumulation and functional gene annotation towards multiple metal resistant potential by Ochrobactrum intermedium BPS-20 and Ochrobactrum ciceri BPS-26. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 320, 124330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Revathi, K.; Khanna, S. Biodegradation of cellulosic and lignocellulosic waste by Pseudoxanthomonas sp R-28. Carbohydr. Polym. 2015, 134, 761–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.-Y.; Cheng, Y.-C.; Yang, W.-L.; Wang, M.-Y. Surface Defect Detection of Wet-Blue Leather Using Hyperspectral Imaging. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 127685–127702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, M.; Naffa, R.; Maidment, C.; Holmes, G.; Waterland, M. Raman and Atr-Ftir Spectroscopy towards Classification of Wet Blue Bovine Leather Using Ratiometric and Chemometric Analysis. J. Leather Sci. Eng. 2020, 2, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NZYSoil gDNA Isolation Kit. Available online: https://www.nzytech.com/en/mb21802-nzy-soil-gdna-isolation-kit/ (accessed on 13 June 2024).

- Church, D.L.; Cerutti, L.; Gürtler, A.; Griener, T.; Zelazny, A.; Emler, S. Performance and Application of 16S rRNA Gene Cycle Sequencing for Routine Identification of Bacteria in the Clinical Microbiology Laboratory. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2020, 33, e00053–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sykes, J.E.; Rankin, S.C. Chapter 4 - Isolation and Identification of Fungi. In Canine and Feline Infectious Diseases, 1st ed.; Sykes, J.E., Ed.; W.B. Saunders: Saint Louis, 2014; pp. 29–36. ISBN 978-1-4377-0795-3. [Google Scholar]

- Satari, L.; Guillén, A.; Vidal-Verdú, À.; Porcar, M. The wasted chewing gum bacteriome. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 16846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolyen, E.; Rideout, J.R.; Dillon, M.R.; Bokulich, N.A.; Abnet, C.C.; Al-Ghalith, G.A.; Alexander, H.; Alm, E.J.; Arumugam, M.; Asnicar, F.; et al. Reproducible, interactive, scalable and extensible microbiome data science using QIIME 2. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 852–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quast, C.; Pruesse, E.; Yilmaz, P.; Gerken, J.; Schweer, T.; Yarza, P.; Peplies, J.; Glöckner, F.O. The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 41, D590–D596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMurdie, P.J.; Holmes, S. phyloseq: An R Package for Reproducible Interactive Analysis and Graphics of Microbiome Census Data. PLoS One 2013, 8, e61217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oksanen, J.; Blanchet, F.G.; Friendly, M.; Kindt, R.; Legendre, P.; McGlinn, D.; Minchin, P.R.; O’hara, R.B.; Simpson, G.L.; Solymos, P. vegan: Community Ecology Package. R Package Version 2.5-7. 2020. Preprint at 2022, 3–1.

- Love, M.I.; Huber, W.; Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardersen, S.; La Porta, G. Never underestimate biodiversity: how undersampling affects Bray–Curtis similarity estimates and a possible countermeasure. Eur. Zool. J. 2023, 90, 660–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrido-Martín, D.; Calvo, M.; Reverter, F.; Guigó, R. A fast non-parametric test of association for multiple traits. Genome Biol. 2023, 24, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nucleotide BLAST: Search Nucleotide Databases Using a Nucleotide Query. Available online: https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi?PROGRAM=blastn&BLAST_SPEC=GeoBlast&PAGE_TYPE=BlastSearch (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Vyskočilová, G.; Carşote, C.; Ševčík, R.; Badea, E. Burial-induced deterioration in leather: A FTIR-ATR, DSC, TG/DTG, MHT and SEM study. Herit. Sci. 2022, 10, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Closest Species | Medium | Temp. | Similarity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rhodococcus rhodochrous, NBRC 16069 | R2A | 30ºC | 98.50 |

| Mammaliicoccus sciuri, DSM 20345 | R2A | 30ºC | 99.84 |

| Bacillus zhangzhouensis, DW5-4 | R2A | 30ºC | 98.87 |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa, JCM 5962 | R2A | 30ºC | 99.69 |

| Leuconostoc mesenteroides subsp. mesenteroides, ATCC 8293 | R2A | 30ºC | 99.32 |

| Empedobacter brevis, LMG 4011 | TSA | 30ºC | 98.85 |

| Bacillus tequilensis, KCTC 13622 | TSA | 30ºC | 99.53 |

| Acinetobacter beijerinckii, CIP 110307 | TSA | 30ºC | 99.14 |

| Glutamicibacter mishrai S5-52 | TSA | 30ºC | 99.36 |

| Bacillus siamensis KCTC 13613 | TSA | 30ºC | 99.28 |

| Bacillus smithii DSM 4216 | YM | 55ºC | 99.20 |

| Paenibacillus typhae CGMCC 1.11012 | YM | 55ºC | 99.25 |

| Aneurinibacillus thermoaerophilus DSM 10154 | YM | 55ºC | 99.28 |

| Ureibacillus suwonensis DSM 16752 | TSA | 55ºC | 99.09 |

| Chelatococcus composti PC-2 | TSA | 55ºC | 99.66 |

| Caldibacillus hisashii N-11 | GYM | 55ºC | 98.02 |

| Aeribacillus pallidus KCTC 3564 | GYM | 55ºC | 98.83 |

| Chelativorans composti, Nis 3 | GYM | 55ºC | 99.40 |

| Thermomyces lanuginosus (hongo) | YM | 55ºC | 100 |

| Brucella ciceri, Ca-34 | R2A | 30ºC | 97.89 |

| Chryseobacterium bernardetii, NCTC 13530 | R2A | 30ºC | 99.67 |

| Brevibacillus parabrevis, NRRL NRS 605 | R2A | 30ºC | 96.59 |

| Bacillus paralicheniformis, KJ-16 | TSA | 55ºC | 99.10 |

| Aeribacillus composti, N.8 | NAI | 55ºC | 99.25 |

| Bacillus aerius, 24K | YM | 55ºC | 94.03 |

| Weizmannia coagulans, ATCC 7050 | YM | 55ªC | 97.25 |

| Ureibacillus thermosphaericus, DSM 10633 | TSA | 55ªC | 99.81 |

| Aeribacillus pallidus, KCTC 3564 | TSA | 55ªC | 3.4 |

| SAMPLE NAME | VESSEL | TYPE | TIME (days) |

|---|---|---|---|

| ine17 | 2L | Composted leather | 44 |

| ine18 | 2L | Composted leather | 44 |

| ine19 | 2L | Control compost | 44 |

| ine20 | 2L | Control compost | 44 |

| ine21 | 40L | Control compost | 0 |

| ine22 | 40L | Control compost | 0 |

| ine23 | 40L | Control compost | 0 |

| ine24 | 40L | Composted leather | 44 |

| ine25 | 40L | Composted leather | 44 |

| ine26 | 40L | Composted leather | 44 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).