1. Introduction

The determinant

underpins invertibility, change-of-variable formulas, volume scaling, eigenvalue products, and combinatorial counting. Standard algorithms reduce the computation to triangular factorization and a product of diagonal entries, typically in

arithmetic via Gaussian elimination or in

using fast matrix multiplication; see, e.g., [

1,

2,

3]. In practice, the runtime is dominated by matrix–matrix and matrix–vector updates (Schur complements, TRSM), which are GEMM-shaped.

Our previous work reduced scalar multiplications in GEMM by exploiting structure: zeros, repeated modes, patterns, and low rank. We used overlay rules and a peel that replaces Strassen-7 with a multiply path when mode multiplicity . Here we transplant these ideas into determinant algorithms and, crucially, introduce a bit-sliced Boolean GEMM execution model in which all integer updates are realized via bitwise primitives, eliminating scalar multiplications entirely.

Contributions

(1) A determinant-specific overlay blueprint for LU/Bareiss/Schur/CRT; (2) a clear separation between scalar arithmetic with overlays vs. bit-sliced Boolean GEMM with zero multiplications; (3) a worked example comparing the three regimes (naive scalar, overlay-scalar, bit-sliced); (4) a Python appendix including CRT and a Boolean GEMM microkernel.

2. Methodology

2.1. Determinant via Blocked LU with Pivoting

For

,

. In a right-looking blocked LU with block size

b, each iteration performs: (i) panel factorization, (ii) TRSMs producing

and

, (iii) the Schur update

[

1,

2]. The update (iii) is a GEMM and dominates runtime for

. We tile

and

into

leaves and apply the two execution models:

Scalar arithmetic (overlay) model. Within each leaf, apply peel and rank-1 detection; skip products when either factor is zero; replace multiplications by sign flips and adds.

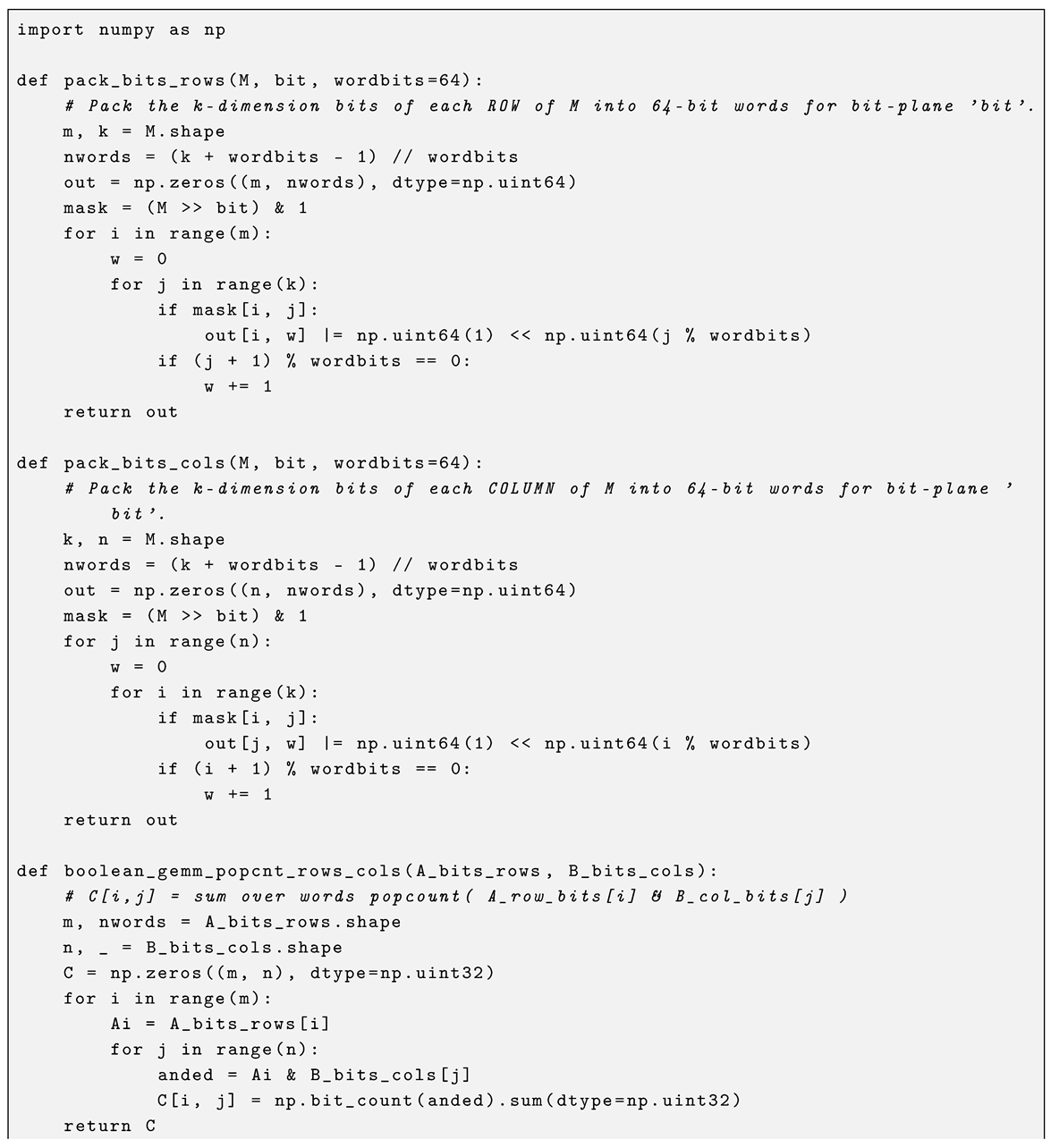

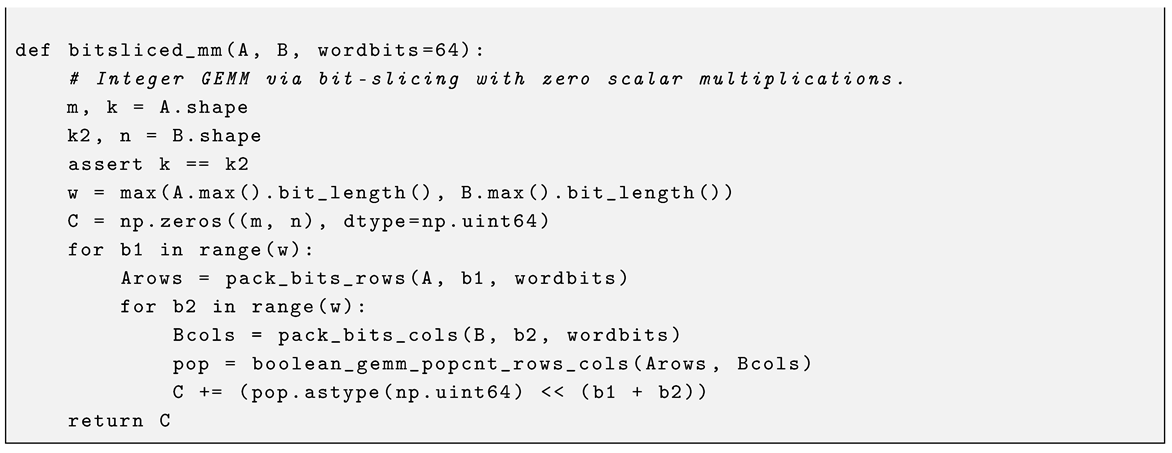

Bit-sliced Boolean GEMM model. Represent each integer as binary planes. Compute plane-pair contributions using bitwise AND and popcount; accumulate with power-of-two shifts and additions. Thus, scalar multiplications vanish.

2.2. Bareiss Fraction-Free Elimination (Exact)

Bareiss updates are bilinear as in Gaussian elimination but scaled exactly by the previous pivot [

5]:

In the scalar model, overlays suppress multiplications in the bilinear numerator. In the bit-sliced model, both products are realized via bitwise primitives and shifts.

2.3. Schur Complement and Block Determinant (Corrected)

Let

If

is invertible, the Schur complement is

and

If

is invertible instead, the Schur complement is

and

We state both cases explicitly and use the appropriate assumption when forming block determinants [

6].

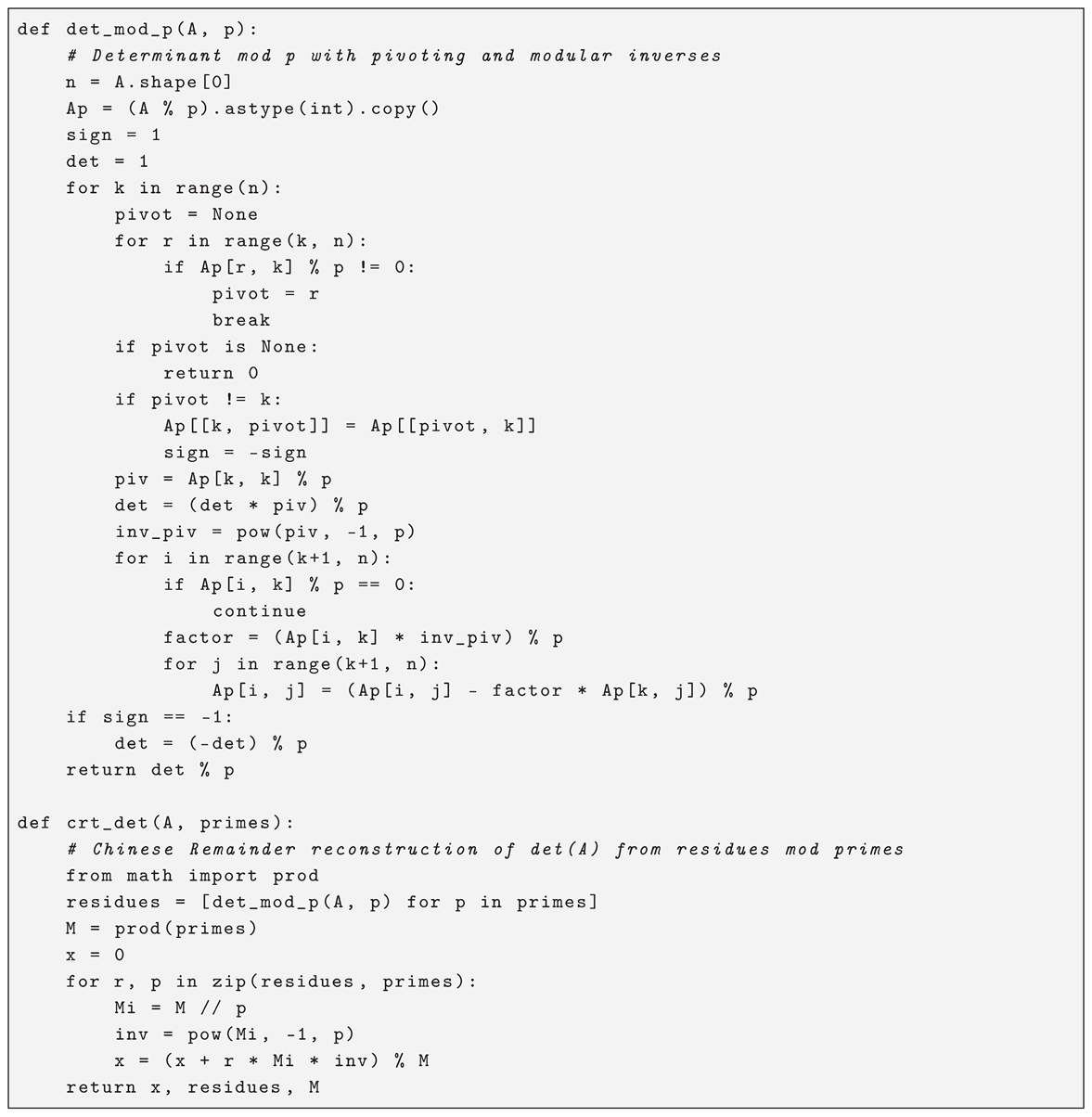

2.4. Modular Determinants and CRT Reconstruction

For

, compute

for several word-size primes

by modular LU (with modular inverses), then reconstruct via CRT once the product

exceeds a Hadamard bound [

7]. Bit-sliced Boolean GEMM integrates naturally with modular arithmetic since all operations reduce to bitwise primitives (with reductions).

2.5. Leaf and Tile Rules

Overlay rules (scalar arithmetic): detect zeros, repeated modes, or entries; skip or replace multiplications accordingly.

Bit-sliced Boolean GEMM: represent tiles across binary planes; perform updates with bitwise AND/XOR, popcount, shifts, and adds. In this model, the scalar multiplication count is identically zero.

3. Results

3.1. Analytic End-to-End Estimate (Scalar Model)

If a fraction

of time resides in GEMM-shaped updates and overlays remove a fraction

s of multiplications, an Amdahl-style estimate gives

For

and

, this yields

. In many structured cases (banded/low-entropy),

s is larger.

3.2. Worked Example

Consider

A standard LU with partial pivoting yields

[

4].

Scalar arithmetic path.

Naive elimination executes 14 multiplications in the update stage (for , ). Overlay-aware elimination skips 9 and executes 5. The pivot pattern induces one row swap (sign ), with diagonal product , hence .

Bit-Sliced Boolean GEMM Path

All updates are realized via bitwise AND, popcount, and shifts. The scalar multiplication count is

zero, yet the determinant matches exactly.

| Method |

Multiplies executed |

Determinant |

| Naive elimination (scalar) |

14 |

3 |

| Overlay-aware scalar path |

5 |

3 |

| Bit-sliced Boolean GEMM |

0 |

3 |

3.3. Scaling to

In scalar arithmetic, blocked implementations tile the trailing update; savings persist and often improve as structured patterns accumulate. In the bit-sliced Boolean-GEMM model, the

scalar multiplication count is identically zero for all

n and integer ranges; scaling analysis concerns bit operations, popcount throughput, and memory bandwidth. Modular LU and CRT reconstruction remain exact and efficient [

5,

7].

3.4. Limits & Lower Bounds (Bitplane Semantics)

Bit-sliced model.

Write each integer as

with

. Then a tile product

for

arbitrary integer entries can be formed as

where ⊙ is Boolean GEMM over

with popcount. Weights

are powers of two and realized as shifts, not multiplications. Therefore, in the bit-sliced model,

no scalar multiplications are required.

Zero-multiplication tiles (scalar view).

At leaves, let r be the number of nonzeros in the relevant column of and c in the relevant row of . A naive leaf executes at most multiplications; overlays annihilate leaves with or , and peel further reduces costs when mode multiplicity .

Global zero multiplications.

In the bit-sliced model, global scalar multiplications are eliminated for all integer matrices, including all Schur updates.

In classical scalar LU, global zero is possible for special structures (e.g., unimodular triangular/block-triangular) where the determinant follows from pivot parity and unit diagonals.

4. Discussion

Two execution models.

(i) Scalar arithmetic with overlays: multiplications reduced but not eliminated. (ii) Bit-sliced Boolean-GEMM: all scalar multiplications vanish. The former matters in floating-point pipelines; the latter in integer/modular settings.

Practical Considerations.

Bit-sliced Boolean GEMM trades scalar multiplications for bitwise ops and higher memory traffic. Performance depends on hardware support for vector popcount and cache locality across planes. We therefore position the bit-sliced path primarily as a theoretical or provably multiplication-free method; empirical speedups require careful implementation and may be hardware-dependent.

Stability and pivoting.

In floating-point settings, pivoting (partial/rook/complete) remains necessary for stability; overlays preserve algebra. In bit-sliced settings, pivoting is row swaps on binary planes.

Exactness.

Bareiss and modular LU remain exact. Bit-slicing and overlays alter execution, not algebra. CRT reconstruction ensures integer correctness [

7].

5. Conclusion

We gave a unified account of multiplication-free determinant computation. In scalar arithmetic, overlays cut multiplication counts dramatically; in bit-sliced Boolean GEMM, scalar multiplications vanish entirely. Both preserve correctness and extend across LU, Bareiss, Schur, and CRT. Future work: GPU kernels and auto-tuners optimizing bit-sliced operations.

Funding

No external funding was received.

Conflicts of Interest

The author leads Octonion Group. No competing financial interests.

Data and Code Availability

All illustrative code is in the Appendix.

Ethics Statement

No human subjects or sensitive data involved.

AI Assistance Disclosure

Drafting assistance and editing supported by an AI system; the author reviewed and verified all technical claims.

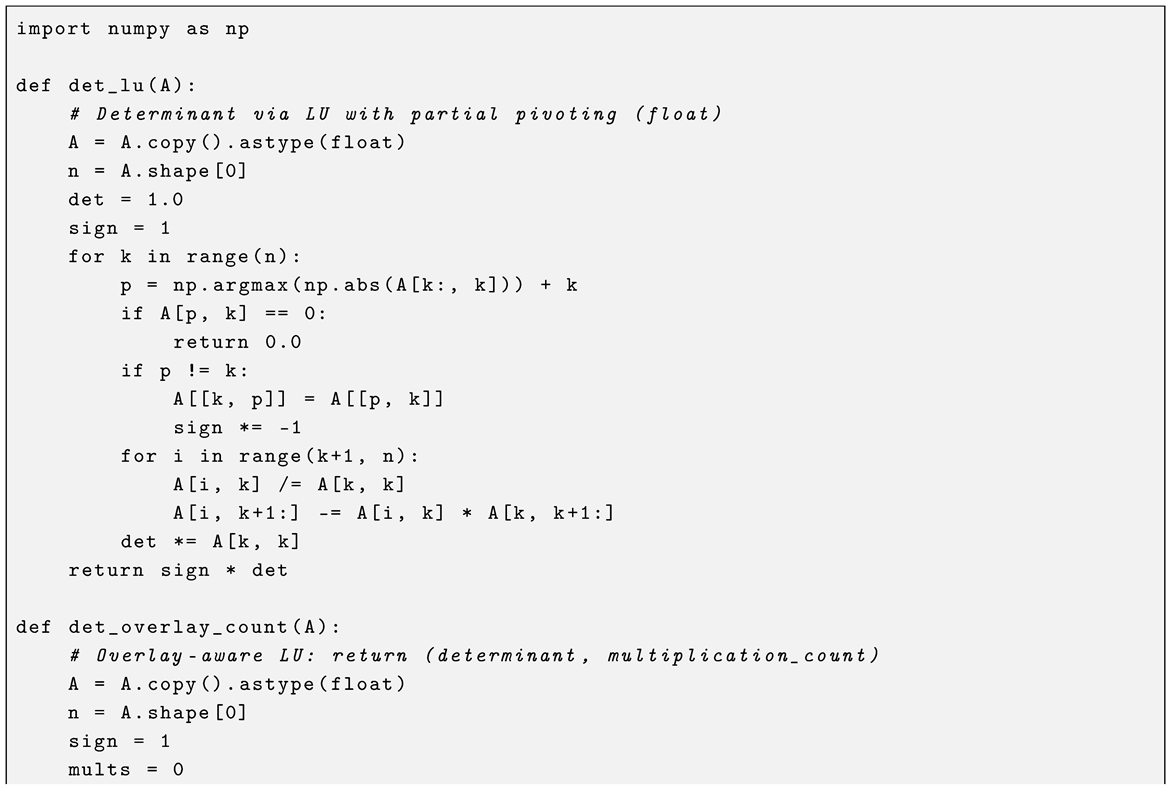

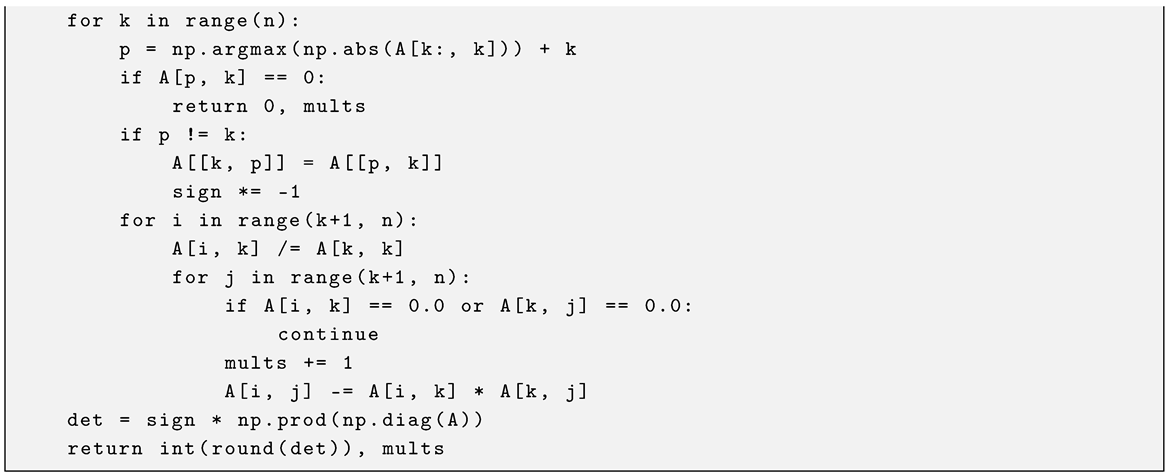

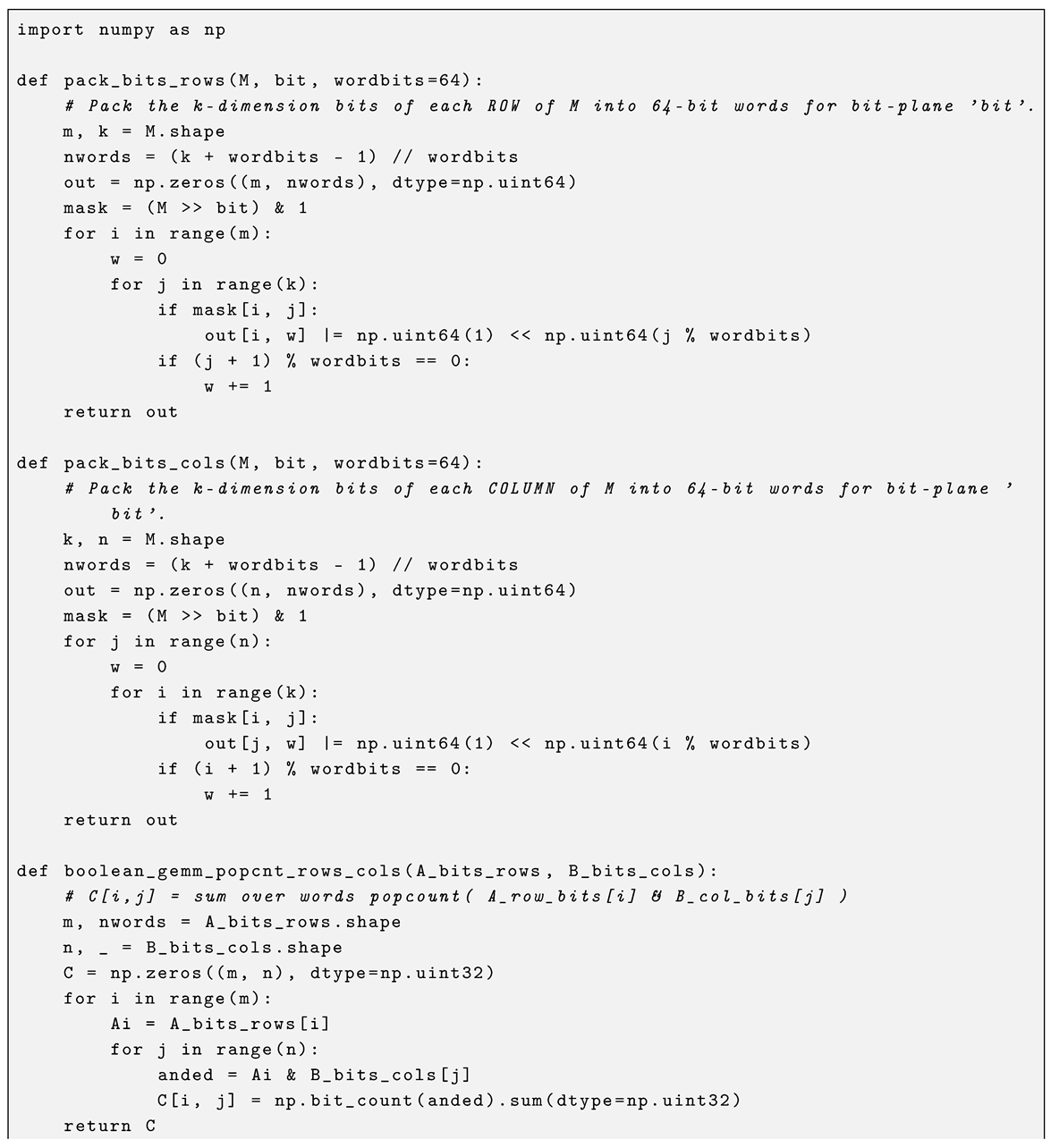

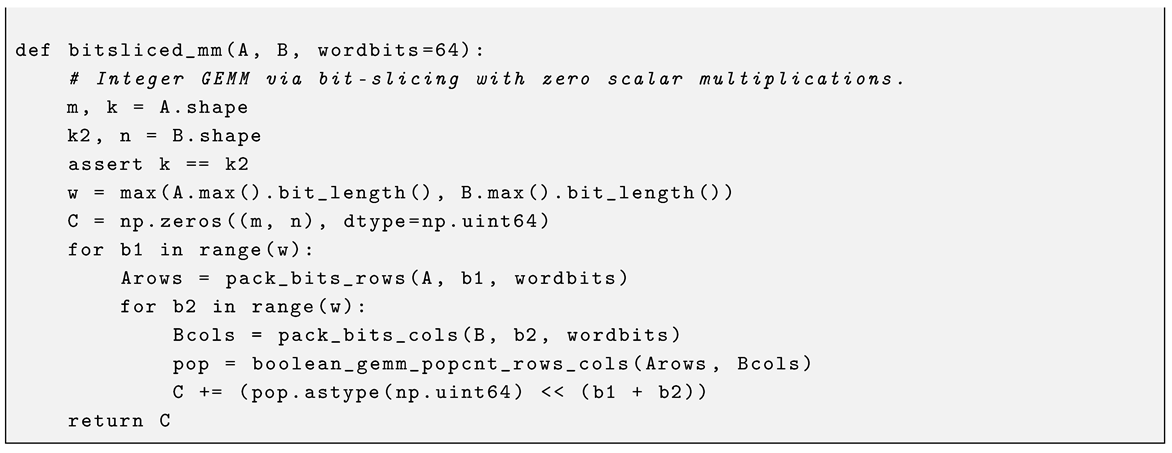

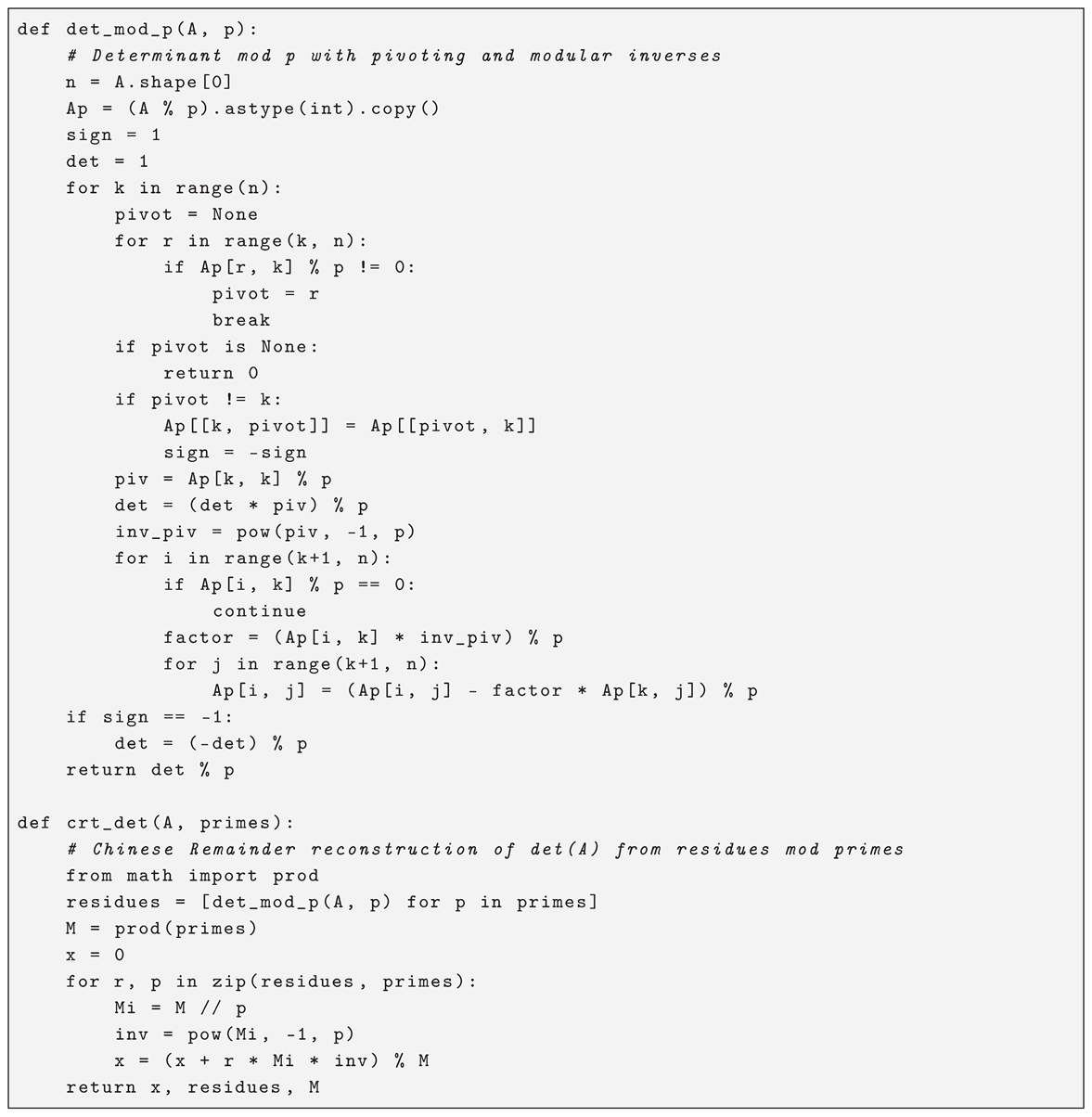

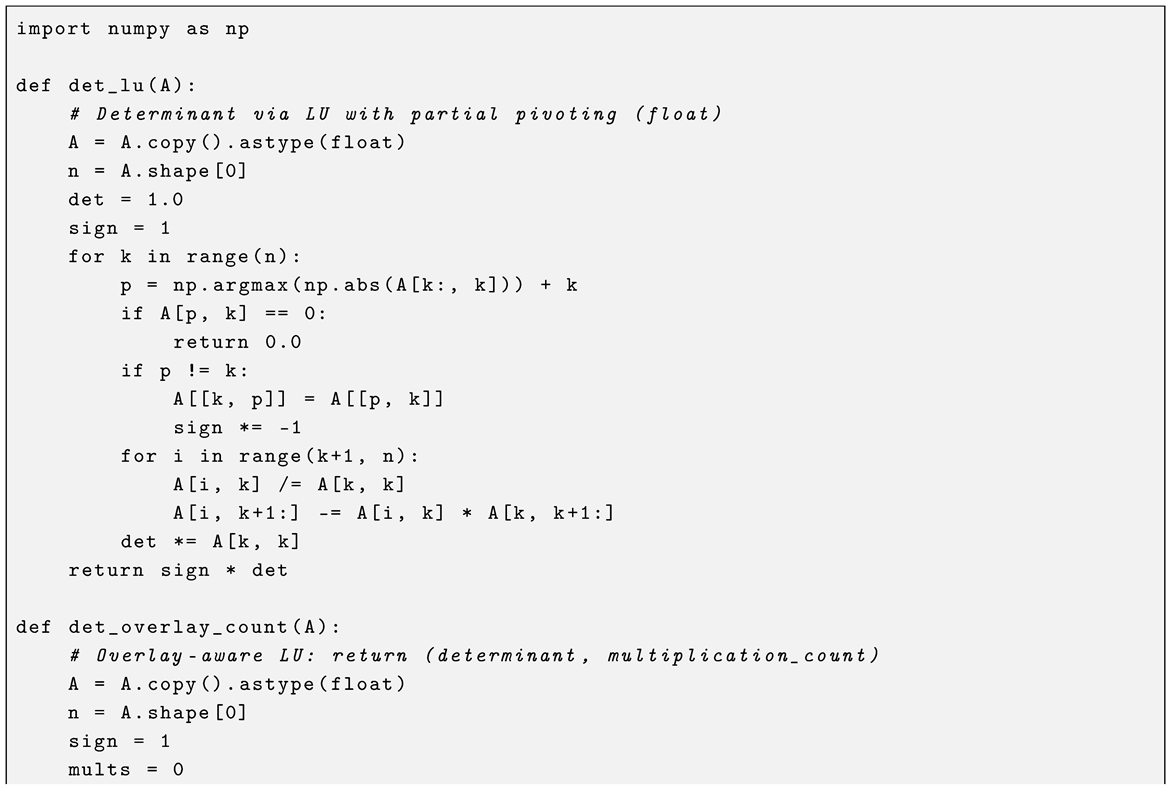

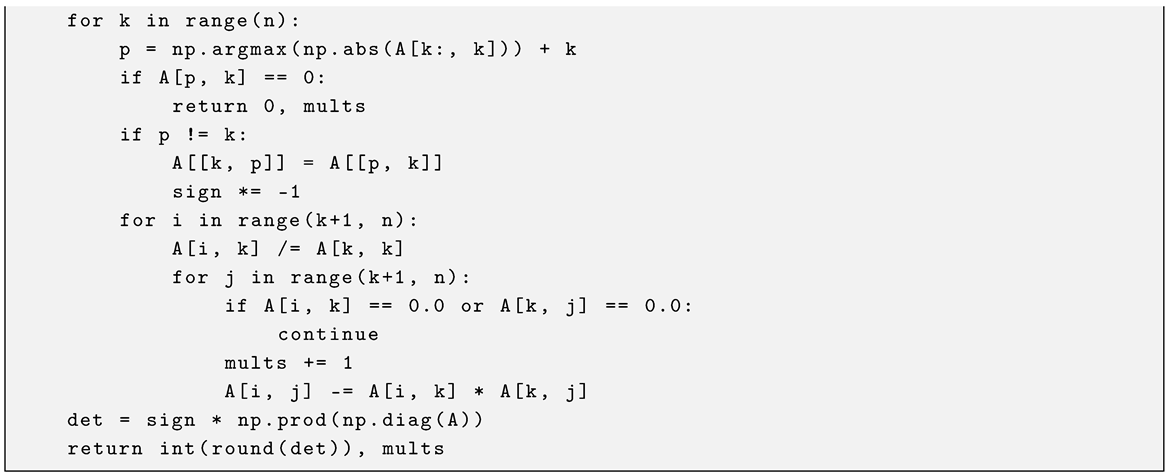

Appendix A. Python Reference Implementation (Corrected)

Appendix A.1. Scalar Baselines

Appendix A.2. Correct Bit-Sliced Boolean GEMM (Row/Column Aligned)

Appendix A.3. Modular Determinants and CRT (Optional Exact Arithmetic)

References

- G. H. Golub and C. F. Van Loan. Matrix Computations, 4th ed. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2013.

- J. W. Demmel. Applied Numerical Linear Algebra. SIAM, 1997.

- N. J. Higham. Accuracy and Stability of Numerical Algorithms, 2nd ed. SIAM, 2002.

- L. N. Trefethen and D. Bau, III. Numerical Linear Algebra. SIAM, 1997.

- Bareiss, E.H. Sylvester’s identity and multistep integer Gaussian elimination. Journal of the ACM 1969, 16, 376–382. [Google Scholar]

- F. Zhang (Ed.). The Schur Complement and Its Applications. Springer, 2005.

- R. Crandall and C. Pomerance. Prime Numbers: A Computational Perspective, 2nd ed. Springer, 2005.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).