Submitted:

10 September 2025

Posted:

10 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

I. Introduction

- Adaptive Spec Inference: We introduce an LLM-driven procedure to dynamically infer candidate sources and sinks from project-specific APIs, commit history, and natural language documentation, overcoming the rigidity of manually curated rule sets.

- Counterfactual Path Validation: We design a neuro-symbolic validation step that prunes infeasible flows and mitigates LLM hallucinations, complementing statistical FP filters with logical guarantees.

- Closed-Loop Analyzer Integration: We couple analyzer feedback with LLM prompting in a feedback-driven loop, enabling continuous refinement of taint specifications across diverse frameworks and codebases.

II. Related Work

A. Traditional Static Analysis

B. False Positive Mitigation Techniques

C. LLMs in Software Engineering

III. MethodIIlogy

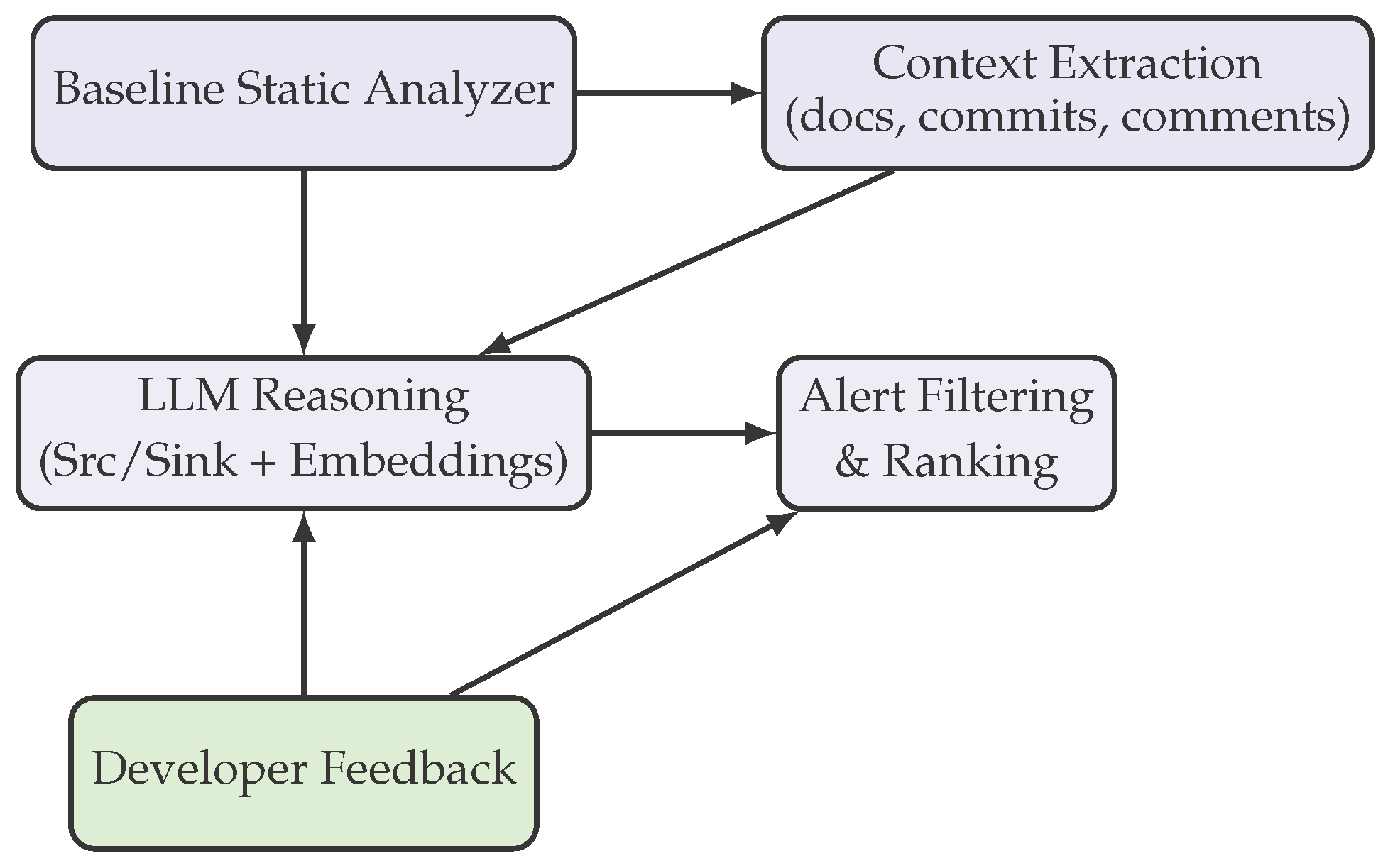

A. Overall Framework

- 1)

- Baseline Static Analyzer: A conventional taint-based static analyzer generates candidate alerts.

- 2)

- Context Extraction: We collect semantic and contextual signals from the project, including API documentation, commit history, inline code comments, and usage examples.

- 3)

- LLM-Based Reasoning: A large language model processes the extracted contexts and produces two outputs: (a) updated source–sink rules and (b) semantic embeddings of alerts.

- 4)

- Alert Filtering and Prioritization: A downstream classifier, trained with LLM embeddings, ranks and filters alerts to reduce false positives.

B. Adaptive Source–Sink Identification

1) Candidate Generation

- Lexical Cues: Names like getInput, readFile, or sendRequest suggest source/sink roles.

- Docstrings & Comments: LLMs analyze natural-language documentation to infer semantics.

- Commit History: Security-related commits (e.g., “sanitize user input”) highlight functions requiring classification.

2) LLM-Based Classification

To mitigate hallucination, we cross-check results across multiple prompts and apply majority voting.“Given the following function signature and documentation, determine whether this function acts as an untrusted input source, a sensitive sink, or neither. Justify briefly.”

C. False Positive Mitigation

- 1)

- Alert Embedding Generation: Each analyzer alert is represented by combining code snippet embeddings (from an LLM) with static features such as path length, presence of sanitization, and control-flow feasibility.

- 2)

- Learning-Based Filtering: A binary classifier (we experimented with logistic regression and gradient-boosted trees) is trained to distinguish true vulnerabilities from spurious ones. Training labels come from (a) ground truth in benchmarks and (b) manual inspection in real-world projects.

D. Iterative Feedback Loop

E. Complexity Considerations

- LLM Query Overhead: Each source–sink classification involves ≈50 tokens, making the process affordable for medium-scale projects.

- Alert Filtering: Once embeddings are pre-computed, filtering is with respect to the number of alerts.

IV. Experiments

A. Experimental Setup

- Baseline: Static analyzer without LLM augmentation.

- LLM-Augmented (no filter): Adaptive source–sink discovery only.

- Proposed (full): Source–sink discovery + false positive filtering.

B. Datasets

- Juliet Test Suite (CWE-based): Over 64,000 test cases across 118 CWEs.

- SV-COMP Benchmarks: Large collection of verification tasks for memory safety, concurrency, and numerical analysis.

- Open-Source Projects: Apache HTTP Server, Node.js, and three medium-sized GitHub repositories with known CVEs.

C. Metrics

- Precision, Recall, F1-score.

- False Positive Rate (FPR).

- Developer Triage Time: Average time taken by developers to classify alerts, measured in a user study with 12 participants.

D. Case Studies

- In Apache HTTP Server, our system identified a custom parseRequest() function as a source, which was overlooked by the baseline analyzer. This led to detection of a path to a sink (execCommand()) that corresponded to a real CVE.

- In Node.js, our system correctly suppressed over 40 false alerts caused by double sanitization, where input was validated both in the middleware and before execution.

E. Developer Study

F. Quantitative Results

G. Ablation Study

| Configuration | Precision | Recall | F1 | FPR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full System | 84.3 | 75.4 | 79.6 | 17.5 |

| – Source/Sink Adaptation | 82.9 | 67.5 | 74.0 | 19.1 |

| – FP Filtering | 68.4 | 76.2 | 72.1 | 35.7 |

| Weak LLM (CodeLlama) | 79.5 | 71.8 | 75.4 | 22.6 |

H. Developer Study

V. Discussion

VI. Conclusion

References

- H. J. Kang, K. L. Aw, and D. Lo, “Detecting false alarms from automatic static analysis tools: How far are we?,” in ICSE, 2022.

- Z. Guo, T. Tan, S. Liu, X. Xia, D. Lo, and Z. Xing, “Mitigating false positive static analysis warnings: Progress, challenges, and opportunities,” IEEE Transactions on Software Engineering, 2023.

- H. Liu, J. Zhang, C. Zhang, X. Zhang, K. Li, S. Chen, S.-W. Lin, Y. Chen, X. Li, and Y. Liu, “Finewave: Fine-grained warning verification of bugs for automated static analysis tools,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2403.16032, 2024.

- B. Rozière, J. Gehring, F. Gloeckle, S. Sootla, I. Gat, and et al., “Code llama: Open foundation models for code,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2308.12950, 2023.

- R. Li, L. von Werra, T. Wolf, and et al., “Starcoder: May the source be with you!,” TMLR, 2023.

- Y. Wang, H. Le, A. D. Gotmare, N. D. Q. Bui, J. Li, and S. C. H. Hoi, “Codet5+: Open code large language models for code understanding and generation,” in EMNLP, 2023.

- A. Lozhkov, A. Velković, and et al., “Starcoder 2 and the stack v2: The next generation,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.19173, 2024.

- Z. Li, S. Dutta, and M. Naik, “Iris: Llm-assisted static analysis for detecting security vulnerabilities,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.17238, 2024.

- P. J. Chapman, C. Rubio-González, and A. V. Thakur, “Interleaving static analysis and llm prompting,” in SOAP ’24: ACM SIGPLAN International Workshop on the State Of the Art in Program Analysis, 2024. [CrossRef]

- C. Wen, Y. Cai, B. Zhang, J. Su, Z. Xu, D. Liu, S. Qin, Z. Ming, and T. Cong, “Automatically inspecting thousands of static bug warnings with large language model: How far are we?,” in ACM TKDD, 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. Ullah, M. Han, S. Pujar, H. Pearce, A. K. Coskun, and G. Stringhini, “Llms cannot reliably identify and reason about security vulnerabilities (yet?): A comprehensive evaluation, framework, and benchmarks,” in IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy, 2024.

- Y. Liu, L. Gao, M. Yang, Y. Xie, P. Chen, X. Zhang, and W. Chen, “Vuldetectbench: Evaluating the deep capability of vulnerability detection with large language models,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2406.07595, 2024.

- C. Wang and H. T. Quach, “Exploring the effect of sequence smoothness on machine learning accuracy,” in International Conference On Innovative Computing And Communication, pp. 475–494, Springer Nature Singapore Singapore, 2024.

- C. Li, H. Zheng, Y. Sun, C. Wang, L. Yu, C. Chang, X. Tian, and B. Liu, “Enhancing multi-hop knowledge graph reasoning through reward shaping techniques,” in 2024 4th International Conference on Machine Learning and Intelligent Systems Engineering (MLISE), pp. 1–5, IEEE, 2024.

- N. Quach, Q. Wang, Z. Gao, Q. Sun, B. Guan, and L. Floyd, “Reinforcement learning approach for integrating compressed contexts into knowledge graphs,” in 2024 5th International Conference on Computer Vision, Image and Deep Learning (CVIDL), pp. 862–866, 2024.

- M. Liu, M. Sui, Y. Nian, C. Wang, and Z. Zhou, “Ca-bert: Leveraging context awareness for enhanced multi-turn chat interaction,” in 2024 5th International Conference on Big Data & Artificial Intelligence & Software Engineering (ICBASE), pp. 388–392, IEEE, 2024.

- T. Wu, Y. Wang, and N. Quach, “Advancements in natural language processing: Exploring transformer-based architectures for text understanding,” in 2025 5th International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Industrial Technology Applications (AIITA), pp. 1384–1388, IEEE, 2025.

- C. Wang, Y. Yang, R. Li, D. Sun, R. Cai, Y. Zhang, and C. Fu, “Adapting llms for efficient context processing through soft prompt compression,” in Proceedings of the International Conference on Modeling, Natural Language Processing and Machine Learning, pp. 91–97, 2024.

- Z. Gao, “Feedback-to-text alignment: Llm learning consistent natural language generation from user ratings and loyalty data,” 2025.

- Z. Gao, “Theoretical limits of feedback alignment in preference-based fine-tuning of ai models,” 2025.

- Y. Sang, “Robustness of fine-tuned llms under noisy retrieval inputs,” 2025.

- Y. Sang, “Towards explainable rag: Interpreting the influence of retrieved passages on generation,” 2025.

- C. Wang, M. Sui, D. Sun, Z. Zhang, and Y. Zhou, “Theoretical analysis of meta reinforcement learning: Generalization bounds and convergence guarantees,” in Proceedings of the International Conference on Modeling, Natural Language Processing and Machine Learning, pp. 153–159, 2024.

- Z. Gao, “Modeling reasoning as markov decision processes: A theoretical investigation into nlp transformer models,” 2025.

- A. Murali, J. Santhosh, M. A. Khelil, M. Bagherzadeh, M. Nagappan, K. Salem, R. G. Steffan, K. Balasubramaniam, and M. Xu, “Fuzzslice: Pruning false positives in static analysis through targeted fuzzing,” in ACM ESEC/FSE, 2023.

- Z. Zhang, “Unified operator fusion for heterogeneous hardware in ml inference frameworks,” 2025.

| Method | Precision | Recall | F1 | FPR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Static Analyzer Only | 62.1 | 71.3 | 66.4 | 38.7 |

| FineWAVE [3] | 73.2 | 72.0 | 72.6 | 27.8 |

| FuzzSlice [25] | 75.1 | 70.9 | 72.9 | 24.5 |

| LLM4SA [10] | 78.5 | 73.9 | 76.1 | 21.2 |

| IRIS [8] | 81.2 | 74.8 | 77.8 | 19.3 |

| Proposed (AdaTaint) | 84.3 | 75.4 | 79.6 | 17.5 |

| Metric | Baseline Analyzer | Proposed System |

|---|---|---|

| Avg. Triage Time (s/alert) | 42.3 | 29.1 |

| Trust Score (1–5 Likert) | 2.7 | 4.1 |

| Perceived Noise Level (1–5) | 4.3 | 2.1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).