Submitted:

05 September 2025

Posted:

08 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Method

Results

Discussion

Conclusion

Conflicts of Interest

Ethical Approval

Declaration of Generative AI and AI-Assisted Technologies

Acknowledgments

References

- Jaworska, N.; MacQueen, G. Adolescence as a unique developmental period. Journal of psychiatry & neuroscience: JPN 2015, 40, 291. [Google Scholar]

- Klonsky, E.D.; Victor, S.E.; Saffer, B.Y. Nonsuicidal self-injury: what we know, and what we need to know. Can. J. Psychiatry. 2014, 59, 565–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nock, M.K. Self-injury. Annual review of clinical psychology 2010, 6, 339–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.-J.; Li, X.; Ng, C.H.; Xu, D.-W.; Hu, S.; Yuan, T.-F. Risk factors for non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) in adolescents: A meta-analysis. EClinicalMedicine 2022, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Chen, L.; Fan, H.; Sun, L.; Yang, T.; Liu, H.; Wang, K. Effects of rumination and emotional regulation on non-suicidal self-injury behaviors in depressed adolescents in China: a multicenter study. Psychology research and behavior management 2025, 18, 271–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Liang, Y.; Gao, Y.; Liu, X. Social support and non-suicidal self-injury in adolescents: The differential influences of family, friends, and teachers. Journal of youth and adolescence 2025, 54, 414–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Li, A.; Li, K.; Zhao, F. How Is Rejection Sensitivity Linked to Non-Suicidal Self-Injury? Exploring Social Anxiety and Regulatory Emotional Self-Efficacy as Explanatory Processes in a Longitudinal Study of Chinese Adolescents. Behavioral Sciences 2024, 14, 943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Y.; Ren, Y.; Liu, T.; You, J. Rejection sensitivity and adolescent non-suicidal self-injury: Mediation through depressive symptoms and moderation by fear of self-compassion. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice 2021, 94, 481–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downey, G.; Feldman, S.I. Implications of rejection sensitivity for intimate relationships. Journal of personality and social psychology 1996, 70, 1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Canyas, R.; Downey, G. Rejection sensitivity as a predictor of affective and behavioral responses to interpersonal stress: A defensive motivational system. In The Social Outcast; Psychology Press, 2013; pp. 131–154. [Google Scholar]

- Somerville, L.H. The teenage brain: Sensitivity to social evaluation. Current directions in psychological science 2013, 22, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gratz, K.L. Risk factors for and functions of deliberate self-harm: An empirical and conceptual review. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice 2003, 10, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olweus, D.; Hart, C. Bullies on the playground: The role of victimization. Children on playgrounds: Research perspectives and applications 1993, 85–128. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, J.S.; Espelage, D.L. A review of research on bullying and peer victimization in school: An ecological system analysis. Aggression and violent behavior 2012, 17, 311–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modecki, K.L.; Minchin, J.; Harbaugh, A.G.; Guerra, N.G.; Runions, K.C. Bullying prevalence across contexts: A meta-analysis measuring cyber and traditional bullying. Journal of Adolescent Health 2014, 55, 602–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samadieh, H.; Soleimani, S. Family Functioning and Bullying Experiences: The Mediating Role of Emotion Regulation Difficulties in Early Adolescence. 2025.

- Bronfenbrenner, U. The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design; Harvard university press, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Prinstein, M.J.; Boergers, J.; Vernberg, E.M. Overt and relational aggression in adolescents: Social-psychological adjustment of aggressors and victims. Journal of clinical child psychology 2001, 30, 479–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, A.; Shi, J.; Wu, N.; Yuan, L. The relationship between bullying victimization and non-suicidal self-injury in adolescents: a moderated mediation model. Current Psychology 2024, 43, 23779–23792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, Q.-N.; Liu, L.; Shen, G.-H.; Wu, Y.-W.; Yan, W.-J. Alexithymia and peer victimisation: interconnected pathways to adolescent non-suicidal self-injury. BJPsych open 2024, 10, e46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perlman, D.; Peplau, L.A. Toward a social psychology of loneliness. Personal relationships 1981, 3, 31–56. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, J.; Wu, Y.; Yuan, J.; Miao, J.; Wang, X.; Yang, Y.; Zang, S. Association between interpersonal sensitivity and loneliness in college nursing students based on a network approach. BMC nursing 2024, 23, 864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qualter, P.; Brown, S.L.; Rotenberg, K.J.; Vanhalst, J.; Harris, R.A.; Goossens, L.; Bangee, M.; Munn, P. Trajectories of loneliness during childhood and adolescence: Predictors and health outcomes. Journal of adolescence 2013, 36, 1283–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samadieh, H.; Rezaei, M. A serial mediation model of sense of belonging to university and life satisfaction: The role of social loneliness and depression. Acta Psychologica 2024, 250, 104562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, T.; Caspi, A.; Danese, A.; Fisher, H.L.; Moffitt, T.E.; Arseneault, L. A longitudinal twin study of victimization and loneliness from childhood to young adulthood. Development and psychopathology 2022, 34, 367–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reshvanloo, F.T.; Rezvani, T.S.; Samadiye, H.; Kareshki, H. Psychometric Properties of the Basic Need Satisfaction in Relationships with Friends Scale in University Students. Knowledge & Research in Applied Psychology 2023, 24, 121–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanhaye Reshvanloo, F.; Samadieh, H.; Goli, B. Psychometric Properties of the Sense of Belonging Instrument Among University Students: Testing the Theory of Human Relatedness. Social Psychology Research 2024, 14, 17–32. [Google Scholar]

- London, B.; Downey, G.; Bonica, C.; Paltin, I. Social causes and consequences of rejection sensitivity. Journal of Research on Adolescence 2007, 17, 481–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preece, D.A.; Goldenberg, A.; Becerra, R.; Boyes, M.; Hasking, P.; Gross, J.J. Loneliness and emotion regulation. Personality and Individual Differences 2021, 180, 110974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradi, M.; Ghanaei Chamanabad, A. Predicting Social and Emotional Loneliness in Students Based on Emotional Dysregulation: The Moderating Role of Gender. Recent Innovations in Psychology 2024, 1, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, B.; Zhang, W.; Sun, L.; Jiang, C.; Zhou, Y.; He, K. Relationship between alexithymia, loneliness, resilience and non-suicidal self-injury in adolescents with depression: a multi-center study. BMC psychiatry 2023, 23, 445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gazelle, H.; Rudolph, K.D. Moving toward and away from the world: Social approach and avoidance trajectories in anxious solitary youth. Child Development 2004, 75, 829–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kochenderfer, B.J.; Ladd, G.W. Peer victimization: Cause or consequence of school maladjustment? Child development 1996, 67, 1305–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boivin, M.; Hymel, S. Peer experiences and social self-perceptions: a sequential model. Developmental psychology 1997, 33, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, S.; Bellmore, A.D.; Mize, J. Peer victimization, aggression, and their co-occurrence in middle school: Pathways to adjustment problems. Journal of abnormal child psychology 2006, 34, 349–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storch, E.A.; Masia-Warner, C. The relationship of peer victimization to social anxiety and loneliness in adolescent females. Journal of adolescence 2004, 27, 351–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madsen, K.R.; Damsgaard, M.T.; Petersen, K.; Qualter, P.; Holstein, B.E. Bullying at school, cyberbullying, and loneliness: national representative study of adolescents in Denmark. International journal of environmental research and public health 2024, 21, 414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Orden, K.A.; Witte, T.K.; Cukrowicz, K.C.; Braithwaite, S.R.; Selby, E.A.; Joiner Jr, T.E. The interpersonal theory of suicide. Psychological review 2010, 117, 575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, P.J.; Jomar, K.; Dhingra, K.; Forrester, R.; Shahmalak, U.; Dickson, J.M. A meta-analysis of the prevalence of different functions of non-suicidal self-injury. Journal of affective disorders 2018, 227, 759–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, R.T.; Sheehan, A.E.; Walsh, R.F.; Sanzari, C.M.; Cheek, S.M.; Hernandez, E.M. Prevalence and correlates of non-suicidal self-injury among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender individuals: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical psychology review 2019, 74, 101783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritz, M.S.; MacKinnon, D.P. Required sample size to detect the mediated effect. Psychological science 2007, 18, 233–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadian, Y.; Mahaki, B.; Lavasani, F.F.; Dehghani, M.; Vahid, M.A. The psychometric properties of the Persian version of interpersonal sensitivity measure. Journal of Research in Medical Sciences 2017, 22, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olweus, D. Revised Olweus bully/victim questionnaire. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Solberg, M.E.; Olweus, D. Prevalence estimation of school bullying with the Olweus Bully/Victim Questionnaire. Aggressive Behavior: Official Journal of the International Society for Research on Aggression 2003, 29, 239–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezapour, M.; Soori, H.; Khodakarim, S. Testing psychometric properties of the perpetration of bullying and victimization scales with olweus bullying questionnaire in middle schools. ارتقای ایمنی و پیشگیری از مصدومیت ها 2014, 1, 212–221.

- DiTommaso, E.; Brannen, C.; Best, L.A. Measurement and validity characteristics of the short version of the social and emotional loneliness scale for adults. Educational and Psychological Measurement 2004, 64, 99–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jowkar, B. Psychometric properties of the short form of the social and emotional loneliness scale for adults (SELSA-S). International Journal of Behavioral Sciences 2012, 5, 311–317. [Google Scholar]

- Sansone, R.A.; Wiederman, M.W.; Sansone, L.A. The self-harm inventory (SHI): Development of a scale for identifying self-destructive behaviors and borderline personality disorder. Journal of clinical psychology 1998, 54, 973–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyers, L.S.; Gamst, G.; Guarino, A.J. Applied multivariate research: Design and interpretation; Sage publications, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- West, S.G.; Finch, J.F.; Curran, P.J. Structural equation models with nonnormal variables: Problems and remedies. 1995.

- Stevens, J.P. Exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis. In Applied multivariate statistics for the social sciences; Routledge, 2012; pp. 337–406. [Google Scholar]

- Neter, J.; Kutner, M.H.; Nachtsheim, C.J.; Wasserman, W. Applied linear statistical models. 1996.

- Dill, E.J.; Vernberg, E.M.; Fonagy, P.; Twemlow, S.W.; Gamm, B.K. Negative affect in victimized children: The roles of social withdrawal, peer rejection, and attitudes toward bullying. Journal of abnormal child psychology 2004, 32, 159–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serafini, G.; Aguglia, A.; Amerio, A.; Canepa, G.; Adavastro, G.; Conigliaro, C.; Nebbia, J.; Franchi, L.; Flouri, E.; Amore, M. The relationship between bullying victimization and perpetration and non-suicidal self-injury: a systematic review. Child Psychiatry & Human Development 2023, 54, 154–175. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, X.; Liu, H.; Lan, Z.; Deng, F. The effect of loneliness on non-suicidal self-injury behavior in Chinese junior high school adolescents: A moderated mediation model. Psychology research and behavior management 2023, 1831–1843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qualter, P.; Vanhalst, J.; Harris, R.; Van Roekel, E.; Lodder, G.; Bangee, M.; Maes, M.; Verhagen, M. Loneliness across the life span. Perspectives on psychological science 2015, 10, 250–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolters, N.E.; Mobach, L.; Wuthrich, V.M.; Vonk, P.; Van der Heijde, C.M.; Wiers, R.W.; Rapee, R.M.; Klein, A.M. Emotional and social loneliness and their unique links with social isolation, depression and anxiety. Journal of Affective Disorders 2023, 329, 207–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeidi Rezvani, T.; Tanhaye Reshvanloo, F.; Samadiye, H.; Kareshki, H. Psychometric Properties of the General Belongingness Scale in University Students. Journal of Applied Psychological Research 2021, 11, 113–130. [Google Scholar]

- Guan, M.; Liu, J.; Li, X.; Cai, M.; Bi, J.; Zhou, P.; Wang, Z.; Wu, S.; Guo, L.; Wang, H. The impact of depressive and anxious symptoms on non-suicidal self-injury behavior in adolescents: a network analysis. BMC psychiatry 2024, 24, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 1. Rejection Sensitivity | 1 | |||

| 2. Victimization | 0.30** | 1 | ||

| 3. Loneliness | 0.19** | 0.36** | 1 | |

| 4. Non-suicidal self-injury | 0.24** | 0.41** | 0.37** | 1 |

| Mean | 48.32 | 6.19 | 28.85 | 4.23 |

| Standard Deviation | 15.63 | 6.81 | 9.79 | 4.19 |

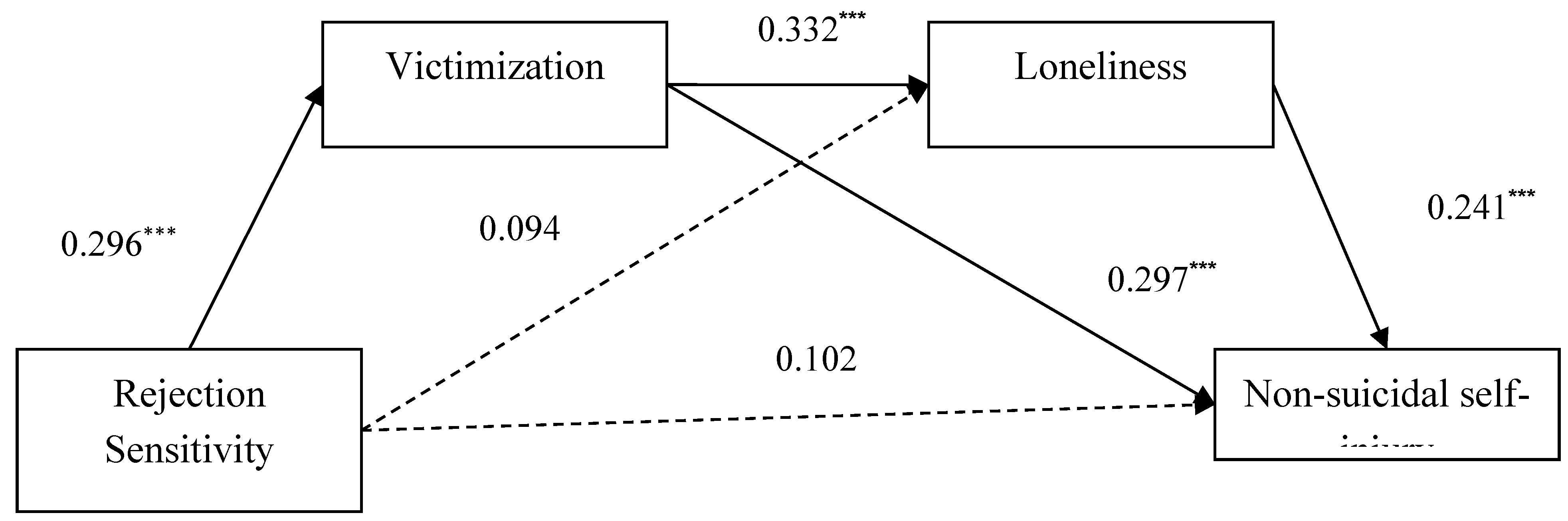

| Regression Equation (N = 297) | Fit Indicator | Coefficient and Significance | ||||

| Outcome Variable | Predictor Variables | R | R2 | F | β | t |

| Victimization | Rejection Sensitivity | 0.295 | 0.087 | 28.272 | 0.296*** | 5.317 |

| Loneliness | Rejection Sensitivity | 0.371 | 0.137 | 23.444 | 0.094 | 1.665 |

| Victimization | 0.332*** | 5.852 | ||||

| Non-suicidal self-injury | Rejection Sensitivity | 0.237 | 0.056 | 17.555 | 0.237*** | 4.189 |

| Non-suicidal self-injury | Rejection Sensitivity | 0.486 | 0.236 | 30.218 | 0.102 | 1.911 |

| Victimization | 0.297*** | 5.260 | ||||

| Loneliness | 0.241*** | 4.392 | ||||

| Effects | Boot SE | Boot LLCI | Boot ULCI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total effect | 0.063 | 0.015 | 0.033 | 0.093 |

| Direct effect | 0.027 | 0.014 | -0.0008 | 0.055 |

| Total indirect effect | 0.134 | 0.032 | 0.075 | 0.205 |

| Indirect effect 1 | 0.087 | 0.026 | 0.042 | 0.146 |

| Indirect effect 2 | 0.022 | 0.016 | -0.006 | 0.059 |

| Indirect effect 3 | 0.023 | 0.008 | 0.009 | 0.043 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).