Submitted:

06 September 2025

Posted:

08 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection, Nucleic Acid Extraction, Library Preparation and Sequencing

2.2. Plastid Genome Assembly, Annotation, Alignment and Variant Calling

2.3. Identification of RNA Editing Sites

3. Results

3.1. Plastid Genome Assembly, Comparisons and Annotation

| Sample | Raw reads | Plastid genome | Plastid-mapped reads | Plastid mapping ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HS1_5B | 292305370 | 127702 bp | 16070696 | 0.0549 |

| HS2_6B | 252953068 | 127716 bp | 7911608 | 0.0312 |

| QC1_5B | 327037602 | 127670 bp | 19483022 | 0.0595 |

3.2. RNA-Seq Alignment

| Sample | Library | Raw reads | Plastid-mapped reads | Plastid mapping ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HS1_5B | Total RNA-seq | 127089854 | 32020931 | 25.19% |

| HS1_5B | rRNA-depleted RNA-seq | 70544244 | 23316279 | 33.05% |

| HS1_5B | mRNA-seq | 100743972 | 434781 | 0.43% |

| HS2_6B | Total RNA-seq | 123558206 | 25053748 | 20.27% |

| HS2_6B | rRNA-depleted RNA-seq | 63621904 | 14703453 | 23.11% |

| HS2_6B | mRNA-seq | 103140076 | 147072 | 0.14% |

| QC1_5B | Total RNA-seq | 112646262 | 33606579 | 29.83% |

| QC1_5B | rRNA-depleted RNA-seq | 66603282 | 26073981 | 39.14% |

| QC1_5B | mRNA-seq | 124564614 | 608462 | 0.48% |

4. Discussion

4.1. Divergent RNA Editing Landscapes Between Glycyrrhiza uralensis and Vigna radiata

4.2. Distinguishing Authentic RNA Editing from Multiple Sources of Technical Artefacts

4.3. Evaluating Library Strategies: Superior Performance of Total RNA-Seq and Utility of mRNA-Seq in RNA Editing Identification

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chateigner-Boutin, A.-L.; Small, I. Plant RNA editing. RNA Biology 2010, 7, 213–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takenaka, M.; Zehrmann, A.; Verbitskiy, D.; Härtel, B.; Brennicke, A. RNA Editing in Plants and Its Evolution. Annual Review of Genetics 2013, 47, 335–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knoop, V. C-to-U and U-to-C: RNA editing in plant organelles and beyond. Journal of Experimental Botany 2022, 74, 2273–2294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, T.; Firoz, A.; Ramadan, A.M. RNA Editing in Chloroplast: Advancements and Opportunities. Current Issues in Molecular Biology 2022, 44, 5593–5604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chateigner-Boutin, A.-L.; Small, I. Organellar RNA editing. WIREs RNA 2011, 2, 493–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Small, I.D.; Schallenberg-Rüdinger, M.; Takenaka, M.; Mireau, H.; Ostersetzer-Biran, O. Plant organellar RNA editing: what 30 years of research has revealed. The Plant Journal 2020, 101, 1040–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Q.; Dugardeyn, J.; Zhang, C.; Mühlenbock, P.; Eastmond, P.J.; Valcke, R.; De Coninck, B.; Öden, S.; Karampelias, M.; Cammue, B.P.A.; et al. The <em>Arabidopsis thaliana</em> RNA Editing Factor SLO2, which Affects the Mitochondrial Electron Transport Chain, Participates in Multiple Stress and Hormone Responses. Molecular Plant 2014, 7, 290–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, F.; Barbacioru, C.; Wang, Y.; Nordman, E.; Lee, C.; Xu, N.; Wang, X.; Bodeau, J.; Tuch, B.B.; Siddiqui, A.; et al. mRNA-Seq whole-transcriptome analysis of a single cell. Nature Methods 2009, 6, 377–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A.; Fang, J.; Zhang, X. Diversity of RNA editing in chloroplast transcripts across three main plant clades. Plant Systematics and Evolution 2023, 309, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adiconis, X.; Borges-Rivera, D.; Satija, R.; DeLuca, D.S.; Busby, M.A.; Berlin, A.M.; Sivachenko, A.; Thompson, D.A.; Wysoker, A.; Fennell, T.; et al. Comparative analysis of RNA sequencing methods for degraded or low-input samples. Nature Methods 2013, 10, 623–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, J.Z.; Yassour, M.; Adiconis, X.; Nusbaum, C.; Thompson, D.A.; Friedman, N.; Gnirke, A.; Regev, A. Comprehensive comparative analysis of strand-specific RNA sequencing methods. Nature Methods 2010, 7, 709–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ura, H.; Togi, S.; Niida, Y. A comparison of mRNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) library preparation methods for transcriptome analysis. BMC Genomics 2022, 23, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarantopoulou, D.; Tang, S.Y.; Ricciotti, E.; Lahens, N.F.; Lekkas, D.; Schug, J.; Guo, X.S.; Paschos, G.K.; FitzGerald, G.A.; Pack, A.I.; et al. Comparative evaluation of RNA-Seq library preparation methods for strand-specificity and low input. Scientific Reports 2019, 9, 13477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, C.P.; Ko, C.Y.; Kuo, C.I.; Liu, M.S.; Schafleitner, R.; Chen, L.F. Transcriptional Slippage and RNA Editing Increase the Diversity of Transcripts in Chloroplasts: Insight from Deep Sequencing of Vigna radiata Genome and Transcriptome. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0129396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawae, W.; Yundaeng, C.; Naktang, C.; Kongkachana, W.; Yoocha, T.; Sonthirod, C.; Narong, N.; Somta, P.; Laosatit, K.; Tangphatsornruang, S.; et al. The Genome and Transcriptome Analysis of the Vigna mungo Chloroplast. Plants (Basel) 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo Giudice, C.; Tangaro, M.A.; Pesole, G.; Picardi, E. Investigating RNA editing in deep transcriptome datasets with REDItools and REDIportal. Nature Protocols 2020, 15, 1098–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porebski, S.; Bailey, L.G.; Baum, B.R. Modification of a CTAB DNA extraction protocol for plants containing high polysaccharide and polyphenol components. Plant Molecular Biology Reporter 1997, 15, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S. Ultrafast one-pass FASTQ data preprocessing, quality control, and deduplication using fastp. iMeta 2023, 2, e107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.-J.; Yu, W.-B.; Yang, J.-B.; Song, Y.; dePamphilis, C.W.; Yi, T.-S.; Li, D.-Z. GetOrganelle: a fast and versatile toolkit for accurate de novo assembly of organelle genomes. Genome Biology 2020, 21, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, X.-J.; Moore, M.J.; Li, D.-Z.; Yi, T.-S. PGA: a software package for rapid, accurate, and flexible batch annotation of plastomes. Plant Methods 2019, 15, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, P.P.; Lin, B.Y.; Mak, A.J.; Lowe, T.M. tRNAscan-SE 2.0: improved detection and functional classification of transfer RNA genes. Nucleic Acids Research 2021, 49, 9077–9096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, T.; Yamada, K.D.; Tomii, K.; Katoh, K. Parallelization of MAFFT for large-scale multiple sequence alignments. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, 2490–2492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Suleski, M.; Sanderford, M.; Sharma, S.; Tamura, K. MEGA12: Molecular Evolutionary Genetic Analysis Version 12 for Adaptive and Green Computing. Molecular Biology and Evolution 2024, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D.; Paggi, J.M.; Park, C.; Bennett, C.; Salzberg, S.L. Graph-based genome alignment and genotyping with HISAT2 and HISAT-genotype. Nature Biotechnology 2019, 37, 907–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danecek, P.; Bonfield, J.K.; Liddle, J.; Marshall, J.; Ohan, V.; Pollard, M.O.; Whitwham, A.; Keane, T.; McCarthy, S.A.; Davies, R.M.; et al. Twelve years of SAMtools and BCFtools. GigaScience 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, J.T.; Thorvaldsdóttir, H.; Wenger, A.M.; Zehir, A.; Mesirov, J.P. Variant Review with the Integrative Genomics Viewer. Cancer Research 2017, 77, e31–e34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camacho, C.; Coulouris, G.; Avagyan, V.; Ma, N.; Papadopoulos, J.; Bealer, K.; Madden, T.L. BLAST+: architecture and applications. BMC Bioinformatics 2009, 10, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, W.; Liu, G.; Wang, W.; Shen, W.; Zhao, Y.; Sun, J.; Yang, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Fan, W.; Pei, S.; et al. RNA Editing and Its Roles in Plant Organelles. Frontiers in Genetics 2021, 12, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y. RNA editing of plastid-encoded genes. Photosynthetica 2018, 56, 48–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hein, A.; Polsakiewicz, M.; Knoop, V. Frequent chloroplast RNA editing in early-branching flowering plants: pilot studies on angiosperm-wide coexistence of editing sites and their nuclear specificity factors. BMC Evolutionary Biology 2016, 16, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldenkott, B.; Yang, Y.; Lesch, E.; Knoop, V.; Schallenberg-Rüdinger, M. Plant-type pentatricopeptide repeat proteins with a DYW domain drive C-to-U RNA editing in Escherichia coli. Communications Biology 2019, 2, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamori, W.; Makino, A.; Shikanai, T. A physiological role of cyclic electron transport around photosystem I in sustaining photosynthesis under fluctuating light in rice. Scientific Reports 2016, 6, 20147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.; Shuai, J.; Ran, Z.; Zhao, J.; Wu, Z.; Liao, R.; Wu, J.; Ma, W.; Lei, M. Structural insights into NDH-1 mediated cyclic electron transfer. Nature Communications 2020, 11, 888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- RUMEAU, D.; PELTIER, G.; COURNAC, L. Chlororespiration and cyclic electron flow around PSI during photosynthesis and plant stress response. Plant, Cell & Environment 2007, 30, 1041–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kleinman, C.L.; Majewski, J. Comment on “Widespread RNA and DNA Sequence Differences in the Human Transcriptome”. Science 2012, 335, 1302–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkhomchuk, D.; Borodina, T.; Amstislavskiy, V.; Banaru, M.; Hallen, L.; Krobitsch, S.; Lehrach, H.; Soldatov, A. Transcriptome analysis by strand-specific sequencing of complementary DNA. Nucleic Acids Research 2009, 37, e123–e123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Incarnato, D.; Oliviero, S. The RNA Epistructurome: Uncovering RNA Function by Studying Structure and Post-Transcriptional Modifications. Trends in Biotechnology 2017, 35, 318–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potapov, V.; Fu, X.; Dai, N.; Corrêa, I.R., Jr.; Tanner, N.A.; Ong, J.L. Base modifications affecting RNA polymerase and reverse transcriptase fidelity. Nucleic Acids Research 2018, 46, 5753–5763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.; Motorin, Y. Next-generation sequencing technologies for detection of modified nucleotides in RNAs. RNA Biology 2017, 14, 1124–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motorin, Y.; Helm, M. RNA nucleotide methylation. WIREs RNA 2011, 2, 611–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Mason, C.E. The Pivotal Regulatory Landscape of RNA Modifications. Annual Review of Genomics and Human Genetics 2014, 15, 127–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debnath, T.K.; Xhemalçe, B. Deciphering RNA modifications at base resolution: from chemistry to biology. Briefings in Functional Genomics 2021, 20, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piskol, R.; Peng, Z.; Wang, J.; Li, J.B. Lack of evidence for existence of noncanonical RNA editing. Nature Biotechnology 2013, 31, 19–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milenkovic, I.; Novoa, E.M. Dynamic rRNA modifications as a source of ribosome heterogeneity. Trends in Cell Biology 2025, 35, 604–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genuth, N.R.; Barna, M. The Discovery of Ribosome Heterogeneity and Its Implications for Gene Regulation and Organismal Life. Molecular Cell 2018, 71, 364–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schuster, G.; Lisitsky, I.; Klaff, P. Polyadenylation and Degradation of mRNA in the Chloroplast. Plant Physiology 1999, 120, 937–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rorbach, J.; Bobrowicz, A.; Pearce, S.; Minczuk, M. Polyadenylation in Bacteria and Organelles. In Polyadenylation: Methods and Protocols; Rorbach, J., Bobrowicz, A.J., Eds.; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, 2014; pp. 211–227. [Google Scholar]

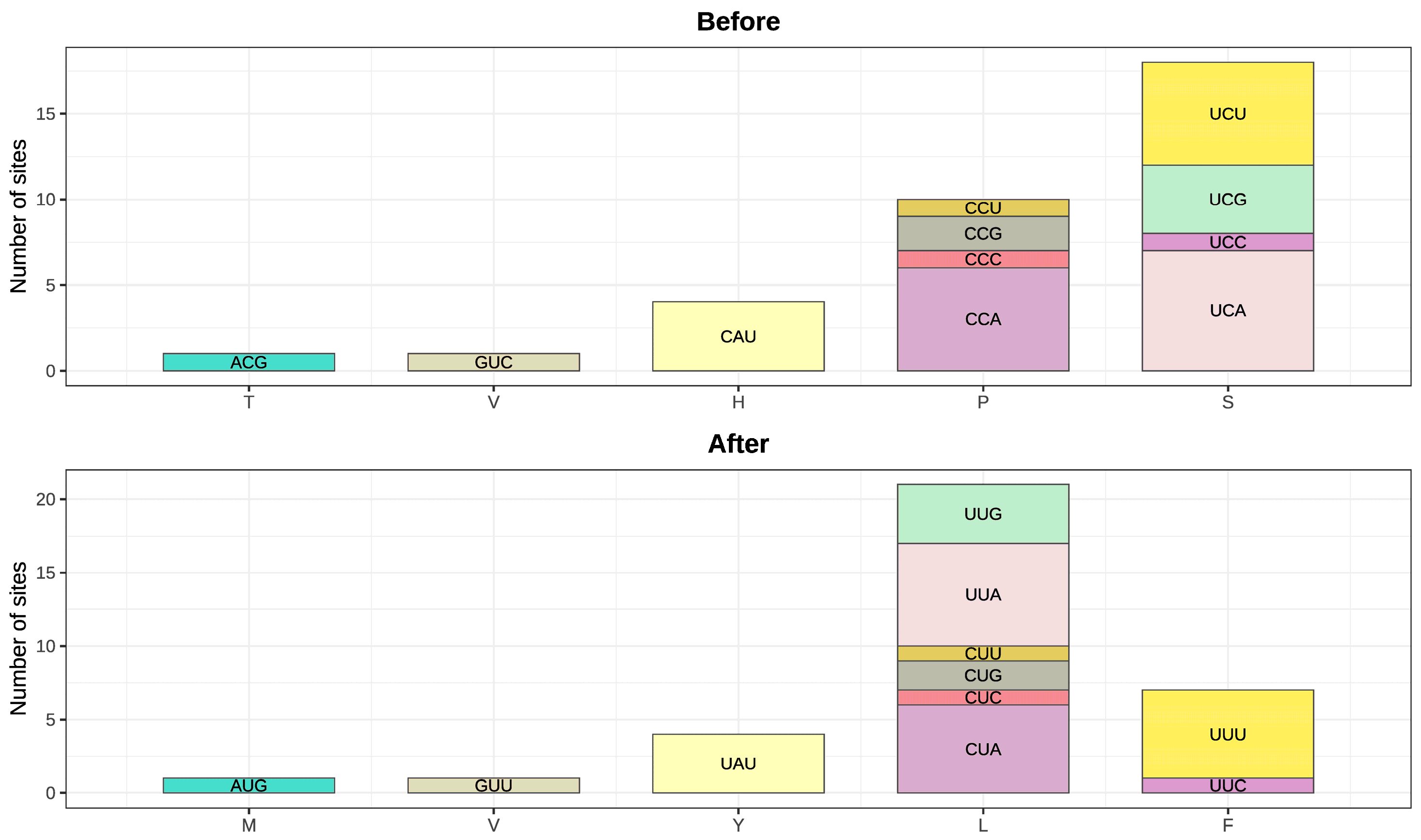

| Gene | Position on Gene |

Codon Change |

Amino Acid Change |

Codon Position |

Editing Efficiency |

Supporting reads |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| accD | 794 | TCG→TTG | S→L | 2 | 0.34~0.53 | 362~1036 |

| accD | 1403 | CCT→CTT | P→L | 2 | 0.57~0.84 | 273~1684 |

| atpA | 791 | CCC→CTC | P→L | 2 | 0.79~0.89 | 611~3605 |

| ndhA | 341 | TCA→TTA | S→L | 2 | 0.57~0.9 | 156~3556 |

| ndhA | 1073 | TCT→TTT | S→F | 2 | 0.42~0.71 | 193~3303 |

| ndhB | 95 | TCA→TTA | S→L | 2 | 0.45~0.77 | 188~2474 |

| ndhB | 413 | CCA→CTA | P→L | 2 | 0.38~0.78 | 129~1469 |

| ndhB | 532 | CAT→TAT | H→Y | 1 | 0.16~0.31 | 47~751 |

| ndhB | 692 | TCT→TTT | S→F | 2 | 0.42~0.79 | 182~2172 |

| ndhB | 782 | TCA→TTA | S→L | 2 | 0.18~0.64 | 81~1491 |

| ndhB | 1058 | TCA→TTA | S→L | 2 | 0.34~0.75 | 157~2515 |

| ndhB | 1201 | CAT→TAT | H→Y | 1 | 0.19~0.49 | 87~1711 |

| ndhB | 1427 | CCA→CTA | P→L | 2 | 0.35~0.68 | 234~2531 |

| ndhD | 383 | CCA→CTA | P→L | 2 | 0.13~0.31 | 18~538 |

| ndhD | 674 | TCG→TTG | S→L | 2 | 0.2~0.58 | 81~438 |

| ndhD | 878 | TCA→TTA | S→L | 2 | 0.33~0.53 | 51~696 |

| ndhE | 230 | CCG→CTG | P→L | 2 | 0.4~0.88 | 546~3135 |

| ndhF | 290 | TCA→TTA | S→L | 2 | 0.69~0.89 | 38~199 |

| ndhG | 50 | TCG→TTG | S→L | 2 | 0.4~0.86 | 393~1980 |

| ndhG | 347 | CCA→CTA | P→L | 2 | 0.45~0.71 | 253~3126 |

| ndhH | 505 | CAT→TAT | H→Y | 1 | 0.5~0.68 | 246~702 |

| petB | 12 | GTC→GTT | V→V | 3 | 0.12~0.2 | 446~3317 |

| petB | 611 | CCA→CTA | P→L | 2 | 0.92~0.98 | 3888~19280 |

| petL | 5 | CCG→CTG | P→L | 2 | 0.36~0.5 | 147~2038 |

| psaI | 79 | CAT→TAT | H→Y | 1 | 0.38~0.62 | 484~2556 |

| psbF | 77 | TCT→TTT | S→F | 2 | 0.66~0.86 | 1960~6852 |

| psbL | 2 | ACG→ATG | T→M | 2 | 0.93~0.96 | 2429~9780 |

| psbZ | 50 | TCC→TTC | S→F | 2 | 0.27~0.74 | 376~6873 |

| rpoA | 200 | TCT→TTT | S→F | 2 | 0.71~0.9 | 206~889 |

| rpoB | 338 | TCT→TTT | S→F | 2 | 0.51~0.82 | 68~361 |

| rpoB | 551 | TCA→TTA | S→L | 2 | 0.55~0.8 | 62~442 |

| rpoB | 566 | TCG→TTG | S→L | 2 | 0.51~0.76 | 66~620 |

| rpoB | 2000 | TCT→TTT | S→F | 2 | 0.68~0.79 | 59~382 |

| rps14 | 80 | CCA→CTA | P→L | 2 | 0.93~0.98 | 4660~14663 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).