Introduction

The low-fertility challenge is confronted by many countries now and is related to a major theoretical question arising in both demography and human evolutionary biology in the past decades: What are the relatively important factors underlying women’s low-fertility behavior in modern societies, when there are increased resources available for reproduction (1)? Taking China as an example, the country is now facing the challenge of lowest-low fertility rate, fast declining births, rapid population aging, and consequent shortage of labor force and pension deficit (2). According to a latest release, China’s total fertility rate was around 1.05 in 2023, i.e. just half of the replacement level (3). Thus, it is not strange that China relaxed its birth control policies again and again in the past 10 years to cope with the urgent challenge and since 2021, married couples have been universally allowed to have three children in their lifetime (4, 5). At the same time, there has been some debate in China: What are really important factors that have caused fertility limitation and thus, should be taken into account in designing countermeasures? Some studies argued that endogenous factors, i.e. spontaneous preference for small family size in reproductive-aged couples, could explain low fertility better than other factors and thus, the focus should be put on promoting high-fertility ideology (6-8); by contrast, others emphasized the importance of provision of convenient childcare services and parenting stipends (9). As will be shown in the theoretical section, a revisiting of the debate from an evolutionary perspective helps to provide new insights—not so evident from a demographic perspective—into it, which will naturally promote the solution of it.

In ranking fertility predictors, demographers and evolutionary anthropologists have different focuses. The former tend to focus on fertility intentions, rather than fertility behavior per se, whereas the opposite is true for the latter. One reason for demographers’ choice might be that fertility intention is proximate to actual childbearing behavior, easy to measure in a cross-sectional study and convenient to analyze comprehensively with the theory of planned behavior (TPB) in social psychology (10-12). According to the TPB, fertility intention is determined by fertility attitudes (personal favorable or unfavorable evaluation of fertility behavior), subjective norms (perceived social pressures on performing or not performing fertility behavior) and perceived behavioral controls (the ease or difficulty of performing fertility behavior). Influences of such factors on fertility intentions vary with parity (11, 13, 14). Subjective norms tend to be the most important predictor of an intention to have the first child: Childless couples have no direct experience of child-bearing and -rearing and thus, they will rely heavily on social custom of transition to parenthood regardless of perceived or practical constraints on reproduction (15, 16). By contrast, attitudes may have a larger effect on fertility intentions in cases of second- or higher-order births: Parents have direct reproductive experience now and thus, there will be more own evaluation of costs and benefits of having another child (17). For instances, reproductive attitudes were the leading predictor of fertility intentions in the nine European countries analyzed by Billari et al. (16) and Klobas (13). Generally, perceived economic constraints (i.e. economic control factors) are not the leading predictors of fertility intentions in low-fertility societies (13). Besides the TPB predictors, previous studies have also shown significant effects of some background factors on fertility intentions; in particular, age is a major or even the most important predictor (11, 18, 19).

Regarding actual fertility behavior, previous studies have also drawn some important conclusions. First, in demography, fertility intentions have been consistently found to be the most important predictor of actual fertility outcomes and they mediates substantially the effects of the TPB factors as well as background factors on fertility behavior. In their analysis of Italian population based on data from Generations and Gender Survey, Letizia et al. (20) found that once fertility intentions were controlled for, fertility attitudes, subjective norms and perceived behavioral controls showed no significant effects on fertility outcomes. Similarly, Kuhnt & Trappe (21) found that the effects of social pressures on fertility outcomes were mainly via their effects on fertility intentions. Second, tending to focus directly on fertility behavior rather than fertility intentions (22, 23), evolutionary anthropologists found that the factors studied by the typical evolutionary models about the causes of the demographic transition—i.e., child mortality, biased cultural transmission, and parental investment—all contributed to fertility choices (24, 25); further analyses indicated that investment factors seemed to explain them best (26, 27).

Currently, there are still some gaps in previous comparative analyses. First, few of them have conducted an integrative analysis of the fertility-related factors’ relative influences on both fertility intentions and fertility behavior, which can have dramatically different sensitivity to such factors. This raises a question: Will focusing just on one of them (intention vs. behavior) lead to misleading results of ranking relative importance? Although somewhat time-consuming in collection, longitudinal data on fertility intentions and their time-lagged realization are suitable for such an integrated analysis (28-30). Second, previous studies have often conceptualized ego-centric social networks as an undifferentiated whole, overlooking systematic variations in network members’ influences on the ego’s fertility choices, particularly between familial and non-familial ties.

From an evolutionary perspective, the current study aims to answer both theoretically and empirically the question mentioned at the beginning: What are the relatively important factors influencing women’s reproductive behavior in modern societies? The focus will be on one-child mothers’ intentions to have a second child and actual second-birth behavior, the key to understanding low-fertility pattern and its dynamics in China—even under the three-child policy (8)—and other low-fertility societies (31). The predictors considered include the TPB ones—the mother’s reproductive attitudes, subjective norms from family members and non-family members, perceived constraints on having a second child—as well as background factors like age. The dominance analysis is used to assess the relative importance of predictors.

The Theoretical Framework and Related Predictions

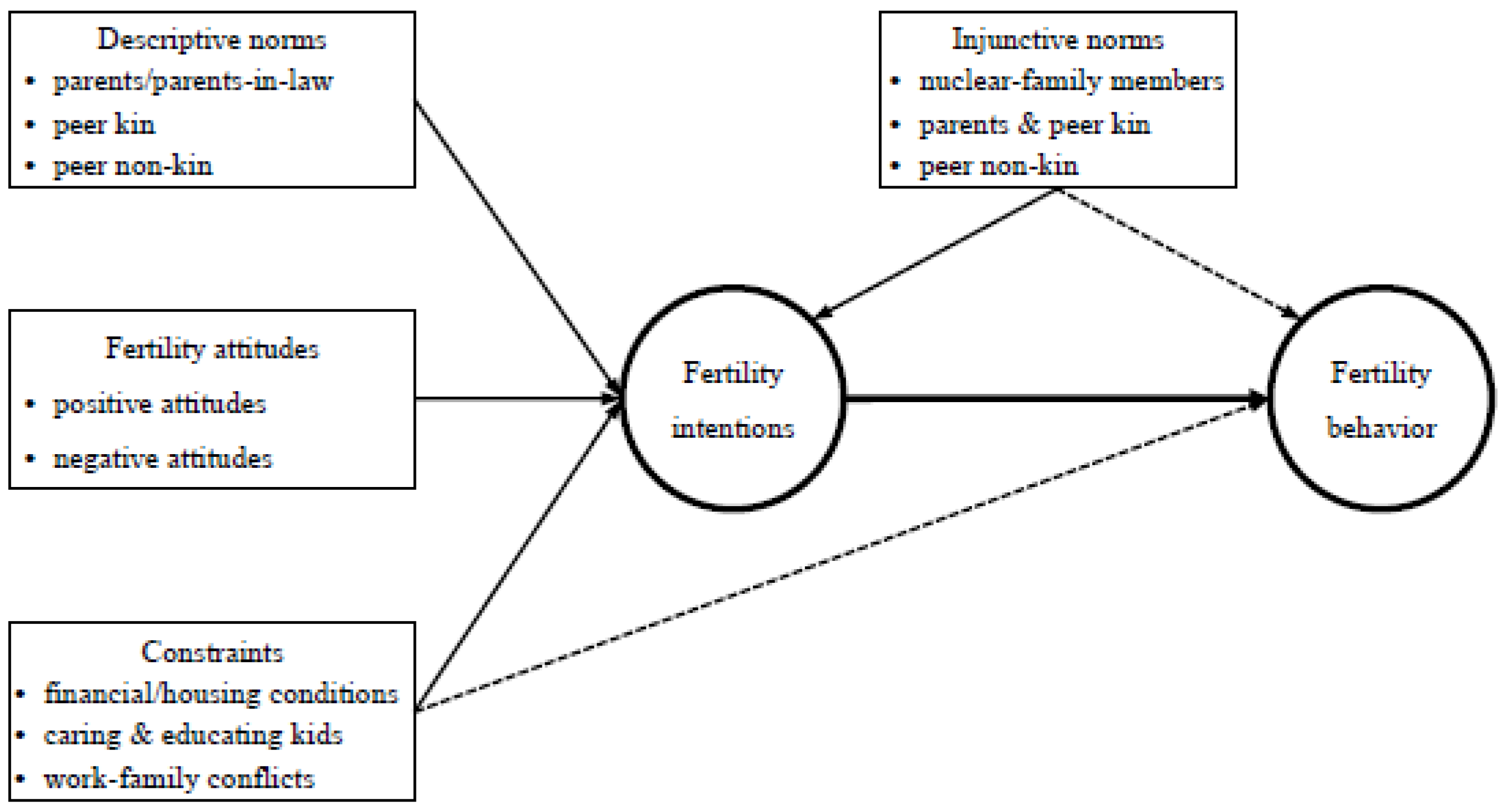

Based on the theory of planned behavior and relevant evolutionary theories, the author proposes an evolutionary framework of planned reproductive behavior (

Figure 1). The framework states that reproductive attitudes, descriptive norms and perceived constraints predict one’s fertility intention, which together with constraints predict actual fertility behavior. Injunctive norms play dual roles: On the one hand, they predict fertility intentions; on the other hand, they predict actual fertility behavior (at least for some members).

It is remarkable that the three categories of the TPB predictors—i.e. reproductive attitudes, norms and constraints—of fertility intentions and behavior can be interpreted and compared for their relative importance more insightfully from an evolutionary perspective. Specifically, attitudes and injunctive norms—two seemingly independent determinants of intentions in the TPB—can be given a unified interpretation from a behavioral ecology approach. Additionally, descriptive norms can be interpreted from a cultural evolution approach, and constraints from a behavioral ecology approach. Two further points are worth mentioning. First, if descriptive norms are not considered and social-network members are not differentiated, the framework will be more or less the same as Ajzen’s original version of the TPB (10). Second, if constraints are further excluded from the framework, i.e. both descriptive norms and constraints are not considered, the remaining structure or sub-system can be called a framework of collective reproductive decision-making (

Figure 1). The detailed reasoning is given below.

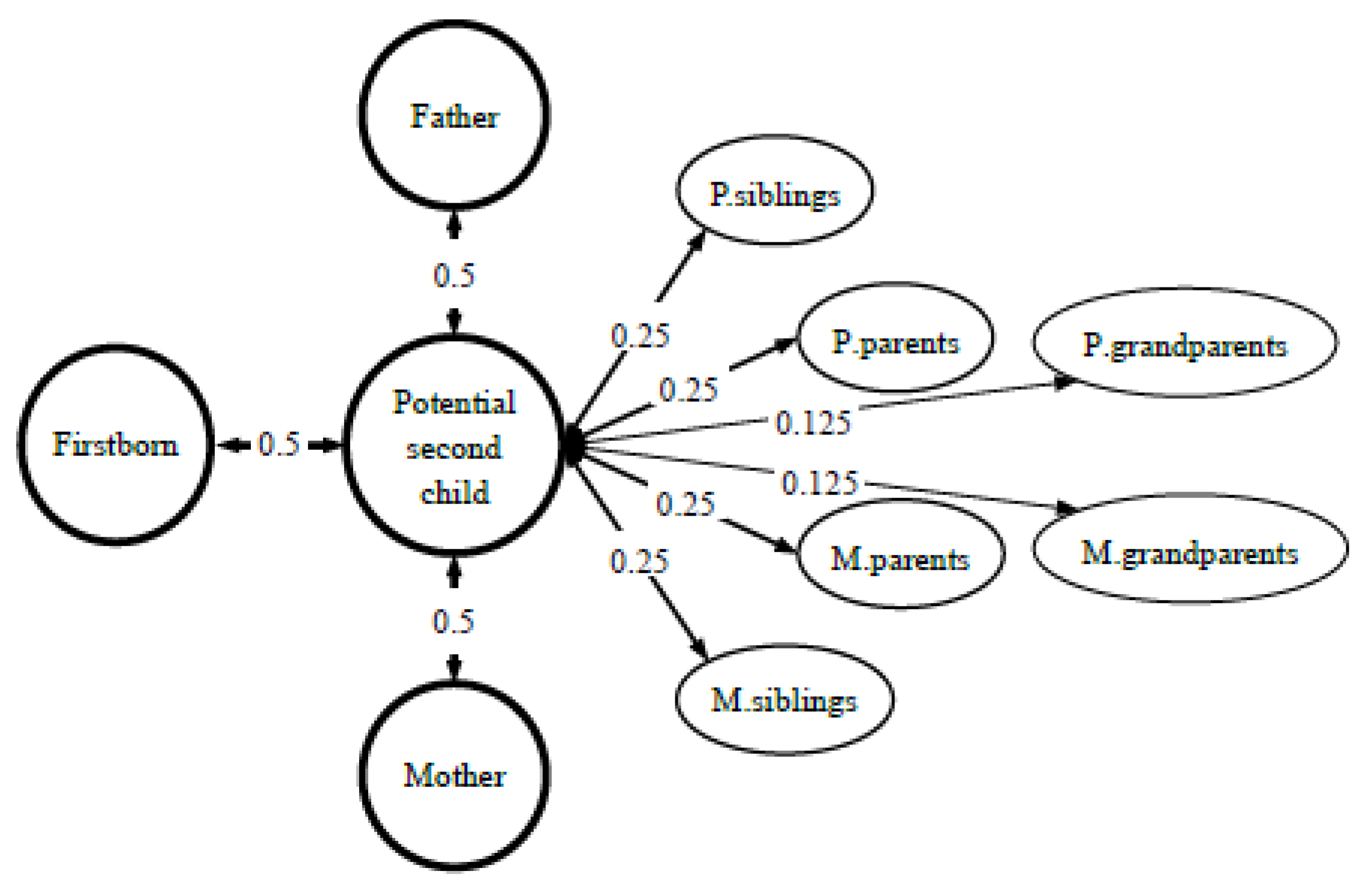

Within a behavioral ecology approach, there are two dimensions—the benefit dimension and the cost dimension—worth consideration in predicting the relative importance of nuclear-family members in fertility intentions and they will give the same predictions. As one of pillars of an evolutionary approach to social behavior, the kinship theory posits that for a given gene in the ego, there is a copy of it identical by descent in a relative at the probability of the degree of relatedness between them (32, 33); thus, the birth of a relative brings some genetic benefit. Another pillar theory, i.e. parental investment theory, posits that investment in an offspring is “at the cost of parent’s ability to invest in other offspring” (34); thus, the birth of an offspring brings some cost in terms of taking up investment resources such as food, time and protection (35). The theory also posits that parental investment is one of key factors limiting reproduction. Thus, it is reasonable to argue that larger investment means larger bargaining power in reproductive decision-making, which can be called an investment/cost dimension. From the dimension of genetic benefit, all members in nuclear family will play more or less the same important role in fertility decision-making, as they have an equal incentive for further reproduction: the mother, her husband, and their firstborn child all have a coefficient of genetic relatedness with the potential second child at 0.5 (32, 33) (

Figure 2). From the dimension of investment/cost, members in the nuclear family will also play more or less an equally important role in second-child decision-making, as the expected investment in the second child is likely the same for each of them (

Table 1). In a word,

the husband and the firstborn child will likely pay the same quantity of cost and gain the same quantity of benefit as the mother herself; thus, they are also the complete stakeholders of a potential second child. (Note: the information asymmetry, when the firstborn child does not know parents’ fertility plan timely or sufficiently, will be informally considered later.) Given the above consideration, we have the following group of predictions about relative importance of the nuclear-family members in fertility intentions:

Prediction P1a: A mother’s intention to have a second child is significantly influenced by the injunctive norms from her husband and firstborn child.

Prediction P1b: Both the effect of the injunctive norms from the mother’s husband on her second-child intention and that from her firstborn child are at the same size as the effect of her own reproductive attitudes.

Regarding the relative importance of nuclear-family members in actual fertility behavior, there seems a difference between their attitudes. According to the TPB, the mother’s own fertility attitudes tend not to affect fertility behavior directly (10). However, it has been indicated that the husband’s and the firstborn’s attitudes towards the second childbirth, i.e. the injunctive norms from them (36), play a dual role. On the one hand, such attitudes work as norms as those from non-family members and affect fertility behavior indirectly via fertility intentions; on the other hand, they work as constraints or behavioral control factors that facilitate or inhibit implementing one’s intention and thus, affect actual fertility behavior directly (11, 18, 30). We now have a group of Predictions about relative importance of the nuclear-family members at the stage of actual fertility behavior:

Prediction P2a: After the mother’s fertility intention is set up, the injunctive norms from her husband and firstborn child significantly influence actual fertility behavior.

Prediction P2b: After the mother’s fertility intention is set up, the injunctive norms from her husband and firstborn child are more important than her own fertility attitudes in influencing actual fertility behavior.

The above theoretical argument for fertility intentions can be generalized to members in the wider social network: the genetic/genealogical kin of the potential second child (i.e. the mother’s kin, including her genetic/genealogical kin and affinal kin; see also ref. 37); the members not related genetically to the potential child (i.e. the mother’s non-kin;

Figure 1;

Table 1). Firstly, from the benefit dimension, the higher a person’s genetic relatedness with the potential second child, the stronger the person will react to favorable or unfavorable things happening to it (e.g., birth or death); in other words, greater genetic relatedness or differential in it when considering an alternative outcome means greater selection pressure for the reaction (38, 39). Consequently, the injunctive norms from the mother’s kin, i.e. their attitudes about whether she should have the child or not, tend to influence her fertility decision-making: If she neglects completely such norms, conflicts will arise, just as the case when a stakeholder’s interest has not been considered sufficiently in an enterprise. In other words, balancing opinions from different stakeholders or kin weighted by their genetic relatedness to the potential child seems to be an optimal strategy in family reproductive decision-making, which is somewhat parallel to Pareto efficiency in collective decision-making in economy (40). By contrast, the injunctive norms from the social-network members not related genetically to the potential child—e.g., the mother’s colleagues, friends or community neighbors—will not influence the mother’s fertility decision-making much: They hold no genetic stake in the reproduction and thus, neglecting their attitudes will not cause much conflict. The above theoretical argument explains some interesting findings in previous studies: e.g., social pressure on reproduction mainly came from family members rather than non-family members (41, 42); receiving emotional support from partners or parents meant higher likelihood of a second birth in modern UK (43, 44); injunctive norms played a more important role in family planning in rural Highland Madagascar with a higher kin density than in urban area (45); in a sample of Dutch women, a slightly larger pressure to have children was perceived from parents than from friends (46). Given the above argument, we have a group of predictions about the mother’s kin vs. non-kin from the benefit dimension:

Prediction P3a: Similarly to the case of the mother’s husband and firstborn child, the injunctive norms from the potential second child’s other genetic/genealogical kin such as its grandparents and those of similar age as she (i.e. the mother’s peer genealogical and affinal kin) significantly influence her second-child intention, but those from the network members not related genetically to the potential child (i.e. her non-kin) do not.

Prediction P3b: Regarding influences of injunctive norms on the mother’s second-child intention, the relative-importance rankings of social-network members will be as follows: the mother’s husband and firstborn child > her parents/parents-in-law ≈ her other peer genealogical and affinal kin > her peer non-kin.

However, viewing from the investment/cost dimension will lead to predictions somewhat different from the above ones. Although the parental investment of the potential second child’s grandparents in it is probably smaller than that of the nuclear-family members, such investment will generally be larger than that of its other genetic kin, which is almost negligible in the context of nuclear family, e.g. in current China (

Table 1). Evidently, although some genetic kin of the potential second child—e.g., its uncles or aunts—are stakeholders of the second childbirth from the benefit dimension, they are not so from the cost dimension. In other words, only the nuclear-family members (the mother, her husband and their firstborn child) and those who will invest substantially in it can be seen as substantial stakeholders of the second childbirth. Given the above argument, we have a group of predictions about the mother’s kin and non-kin from the cost dimension:

Prediction P4a: Similarly to the case of the mother’s husband and firstborn child, the injunctive norms from her parents/parents-in-low significantly influence her second-child intention, but those from her other peer kin and non-kin do not.

Prediction P4b: Regarding influences of injunctive norms on the mother’s second-child intention, the relative-importance rankings of social-network members will be as follows: the mother’s husband and firstborn child > her parents/parents-in-law > her other peer kin ≈ her peer non-kin.

In the above discussion, we note—from both the benefit and the cost dimensions—that the mother’s non-kin will not influence her decision-making through their injunctive norms, but they can have an influence through descriptive norms, i.e. their own reproductive choices. According to the theory of cultural evolution, horizontal transmission of new cultural norms (e.g. peers’ choices) might be more efficient than vertical transmission (e.g. parents’ choices), owing to its timely response to ecological changes—thus shorter generation length—as well as one-to-many efficiency (47-49). Given the above argument, we have a group of predictions about horizontally versus vertically transmitted fertility norms:

Prediction P5a: Both the number of children in parents/parents-in-law and that among the mother’s peer genealogical and affinal kin and other social-network peers not related genetically to the potential child will significantly influence her second-child intention.

Prediction P5b: In influencing the mother’s second-child intention, the number of children among her peers—peer kin and peer non-kin—will be more important than that in her parents/parents-in-law.

Lastly, some prediction can be set up with respect to socio-economic constraints. As mentioned above, such constraints tend to have no major influence on fertility intentions in low-fertility countries (13, 16). However, their influences may become larger from fertility decision-making to actual fertility behavior. For instance, although underestimated by decision-makers before conception, the care of a potential child grow more tangible and pressing over the pregnancy; sometimes, the pressure leads to prenatal or postnatal depression. Furthermore, evolutionary anthropologists argue that greater required investment in oneself and offspring in modern competitive societies will be associated with smaller family size (e.g., ref. 50). The above arguments have received empirical support in anthropological and demographic studies: Socio-economic resources available for parenting and investment in own and offspring education can be major factors limiting actual choice of family size (51-57). Given the above argument, we have the following prediction about the influence of constraints:

Prediction P6: After fertility intention is set up, constraints become more important in influencing actual fertility behavior.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Among the 262 mothers who had one child at the time of the baseline survey, 36 of them had a second child; in other words, during the 2.5 years of follow-up interval, the vast majority of mothers did not reproduce again. In the baseline survey, 57.25% of reproductive-aged mothers did not plan to have a second child (‘rather disagree’ or ‘completely disagree’). Although 70 mothers initially planned to have a second birth (‘completely agree’ or ‘rather agree’), only 24 of them really did so; among 42 mothers who had no clear fertility intention initially (‘neither agree nor disagree’), seven of them reproduced again; finally, among 150 mothers who initially did not plan to give another birth, five of them actually did so. The descriptive statistics of all other variables are shown in

SI Appendix A (Supplementary text) and SI Appendix B (Table A.2).

Predictors’ Effects on Fertility Intentions and Their Relative Importance

Among the five groups of predictors, the following ones were found to be significantly associated with the intention to have a second child at the time of the baseline survey (

Table 2). (1) Among the background factors, only age was a significant predictor: The mother’s intention not to have a second child increased by 0.053 for every one-year increase in age (

P < 0.001;

Table 2). (2) Among the fertility attitudes, the attitude towards the second childbirth’s benefits to personal/family well-being was a highly significant predictor: The more positive the attitude, the stronger would be the mother’s fertility intention (estimate

β = 0.295,

P < 0.001). Additionally, the mother’s recognition of a risk of lineage extinction, i.e. losing the only child, marginally significantly predicted a stronger intention to have a second child (

β = 0.134,

P < 0.10). (3) Among the injunctive norms, both husband’s and firstborn’s fertility attitudes were significantly associated with the mother’s fertility intention. For every unit increase in husband’s disagreement with the second childbirth, the mother’s intention not to have a second child increased by 0.275 unit (

P < 0.001). Compared to the case that a firstborn child was not inquired about his/her attitude towards the second childbirth, the mother’s intention to have a second child would increase by 0.629 when her firstborn thought she should reproduce again (

P < 0.01). None of the injunctive norms from parents/parents-in-law, peer relatives and friends/colleagues were significant. (4) Among the descriptive norms, the number of children among peer relatives and peer friends/colleagues emerged as significant predictors. Compared to the case where most of peer relatives had two or more children, a mother in other cases (e.g., few peer relatives had two or more children) had a stronger intention not to have a second child (

β = 0.514,

P < 0.05). Similarly, the case when most of friends/colleagues had two or more children was associated positively with an intention to have a second child in a mother (

β = 0.619,

P < 0.05). Neither the mother’s nor her husband’s number of siblings predicted significantly her fertility intention. (5) Among the economic constraints, only perceived difficulty in caring/educating children was linked significantly with the mother’s fertility intention, such that ‘feeling no clear difficulty’ meant a more positive intention (

β = -0.442,

P < 0.05). None of other constraints significantly predicted fertility intentions. The above estimates and their significance levels preliminarily suggest that significant predictors were important, but those non-significant ones were not so.

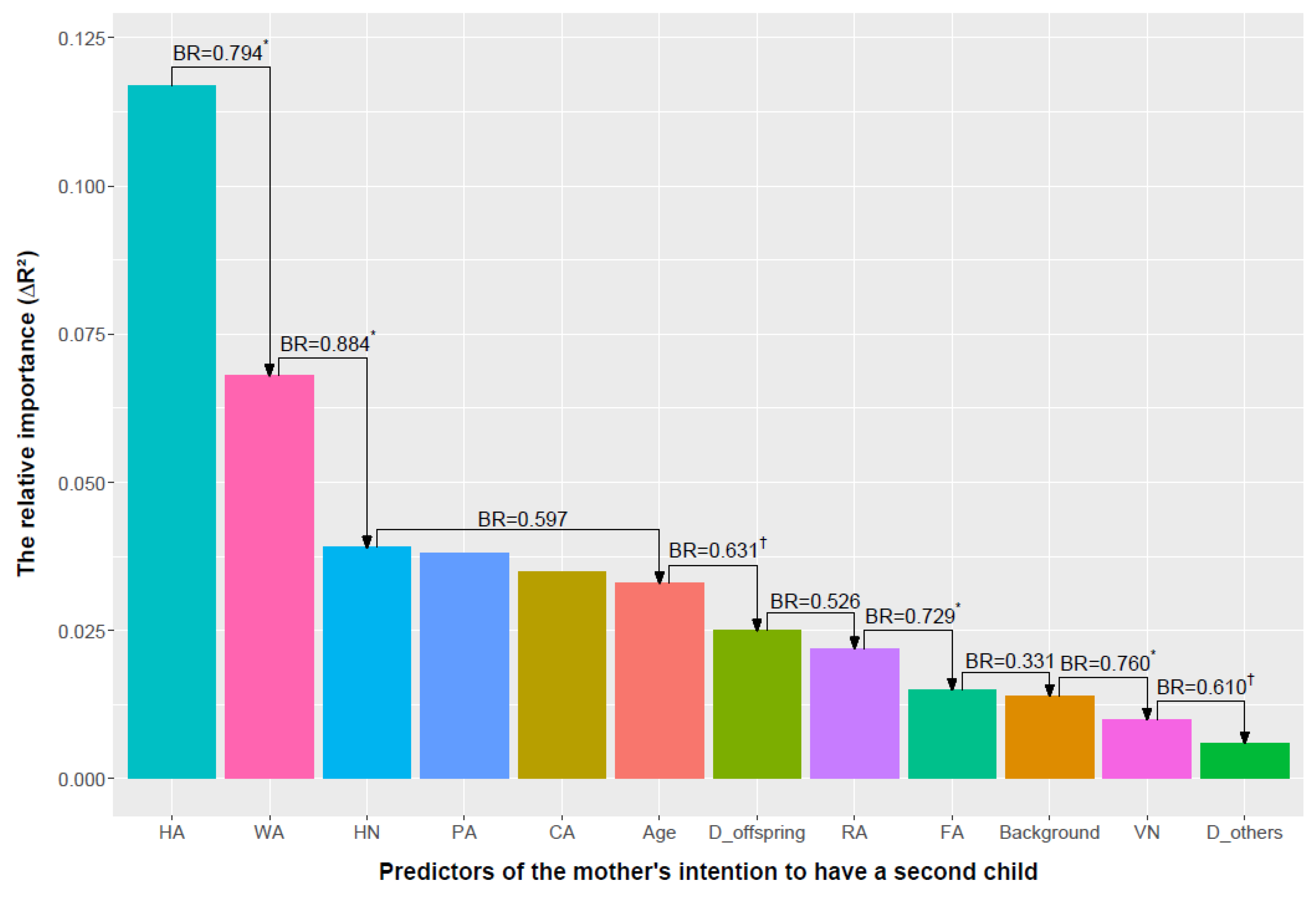

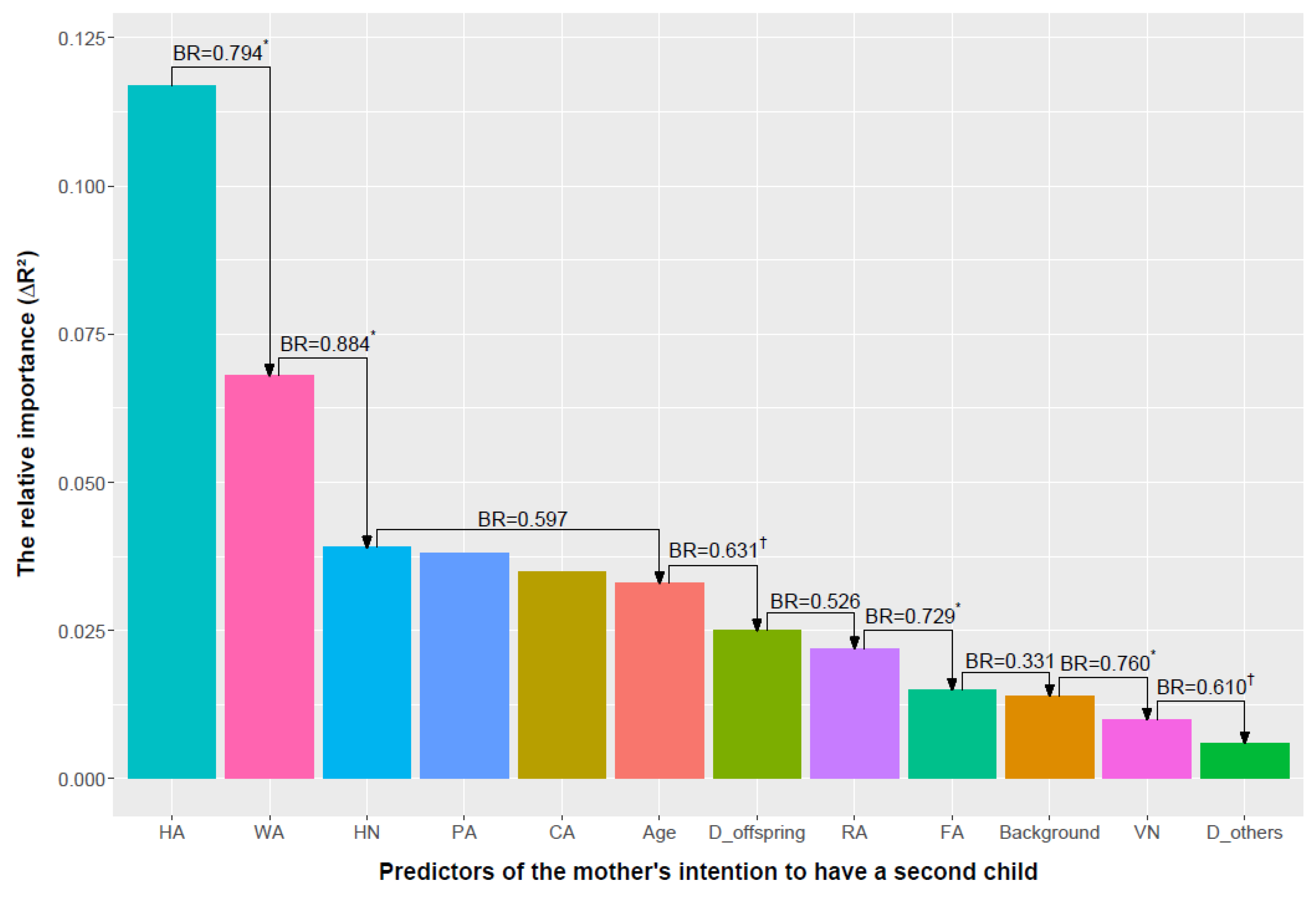

The formal dominance analysis indicates the relative-importance rankings of predictors of fertility intentions in the current sample, which was basically robust as can be seen from bootstrap resampling (

Figure 3). The injunctive fertility norms from the mother’s husband were the most important predictor of her fertility intention (Δ

=0.117), followed by the mother’s own fertility attitudes (Δ

=0.068). These two factors made larger contribution to variance of fertility intention than any other one. Following these two factors, the number of children among peer relatives and friends/colleagues (Δ

=0.039), the injunctive norms from parents/parents-in-law (Δ

=0.038), the injunctive norms from the firstborn child (Δ

=0.035) and age (Δ

=0.033) were of similar size in relative importance, as can be seen from the bootstrap resampling: The reproducibility of dominance comparison between any pair of them was lower than 60%. The difference in dominance of age and perceived difficulty in rearing and educating offspring (Δ

=0.025) was marginally significant. The dominance of the latter was of similar size as that of the injunctive norms from peer relatives (Δ

=0.022), which was further significantly larger than those of friends/colleagues (Δ

=0.015) and background factors (Δ

=0.014). The number of children in parents or parents-in-law and other perceived difficulties were the least important in predicting mother’s fertility intention (Δ

=0.010 and 0.006, respectively).

Based on the regression analysis and dominance analysis, it can be seen that the predictions P1a and P5b are fully supported, but other predictions on fertility intentions are not. The prediction P1b is not supported: The dominance of the mother’s own, her husband’s, the firstborn child’s fertility attitudes was not comparable; instead, it showed a clear gradient. The prediction P3a is only partly supported: Indeed, the mother’s peer non-kin did not significantly influence her intention to have a second child; however, the injunctive norms from her other kin (parents/parents-in-law and peer kin) did not either. The prediction P3b is basically not supported: The firstborn child and parents/parents-in-law were of similar importance in influencing the mother’s fertility intention; also, not as predicted, the injunctive norms from parents/parents-in-law were more important than those of peer kin (BR=0.812). Evidently, the predictions P4a and P4b fare better: Although the predictions about parents/parents-in-law were not fully supported, other predictions including those on peer kin and peer non-kin were fully supported. Finally, the prediction P5a is only partly supported, as the number of children in parents/parents-in-law did not significantly influence the mother’s fertility intention.

Predictors’ Effects on Fertility Behavior and Their Relative Importance

The following predictors were found to be significantly associated with the actual second-birth behavior during the interval between two surveys (

Table 2). (1) Fertility intentions. When controlling for other predictions, for every unit increase in the mother’s intention not to have a second child, the probit of second childbirth decreased by 0.546 (

P < 0.001). Based on the estimate, there is an intuitive way to see the effect of fertility intention: When fertility intention changed from ‘completely agree’ to ‘completely disagree,’ the probability or cumulative distribution function (CDF) of having a second child would decline from 35.27% (probit = 0.168 - 0.546 × 1) to 0.520% (probit = 0.168 - 0.546 × 5), a value close to zero. (Notes: a. 0.168 was the intercept when other predictors were controlled for at their mean values; b. compare 35.27% with 24/70 mentioned above to see their proximity.) (2) Injunctive norms. Compared to the case when the firstborn child was not inquired about his/her attitude, the probit of second childbirth increased by 0.957 when the firstborn child thought his/her mother should have a second child (

P < 0.05); in other words, when controlling for other predictors, the probability of having a second child would increase from 1.769% to 12.569% (see above computation of CDF). Both the mother’s own and her husband’s fertility attitudes did not predict significantly second-birth behavior. (3) Descriptive norms. Compared to the case when a mother was an only child of her parents, the probit of second childbirth decreased by 0.848 when she had siblings (

P < 0.05). (4) Perceived constraints. Compared to the case when the mother perceived potential difficulty in rearing and educating two children, the probit of having a second child would increase by 0.717 when such a difficulty was not perceived (

P < 0.05). Besides the above predictors which significantly predicted the actual fertility behavior, there were also some marginally significant predictors, including the mother’s education, husband’s number of siblings, and other two categories of perceived constraints.

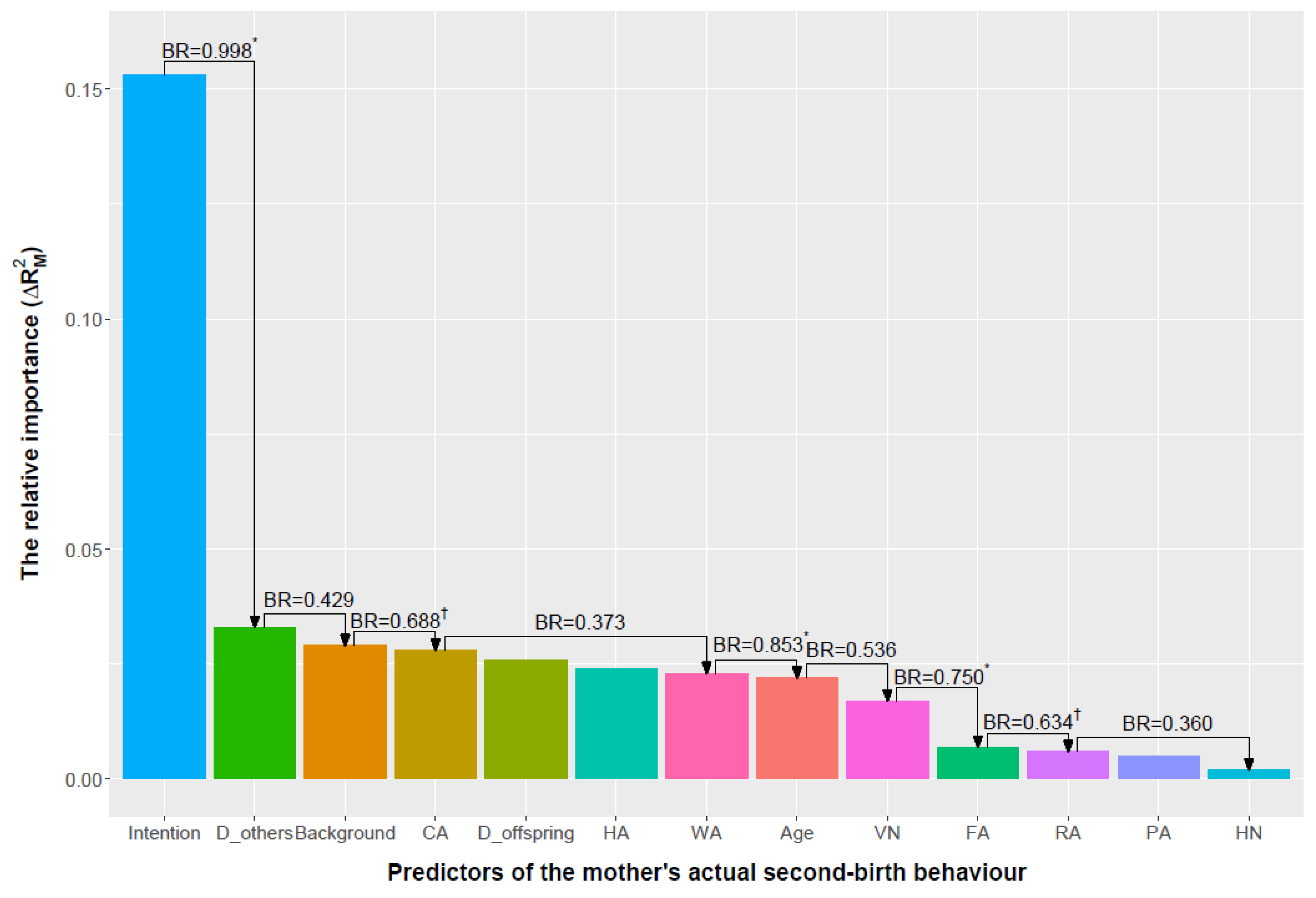

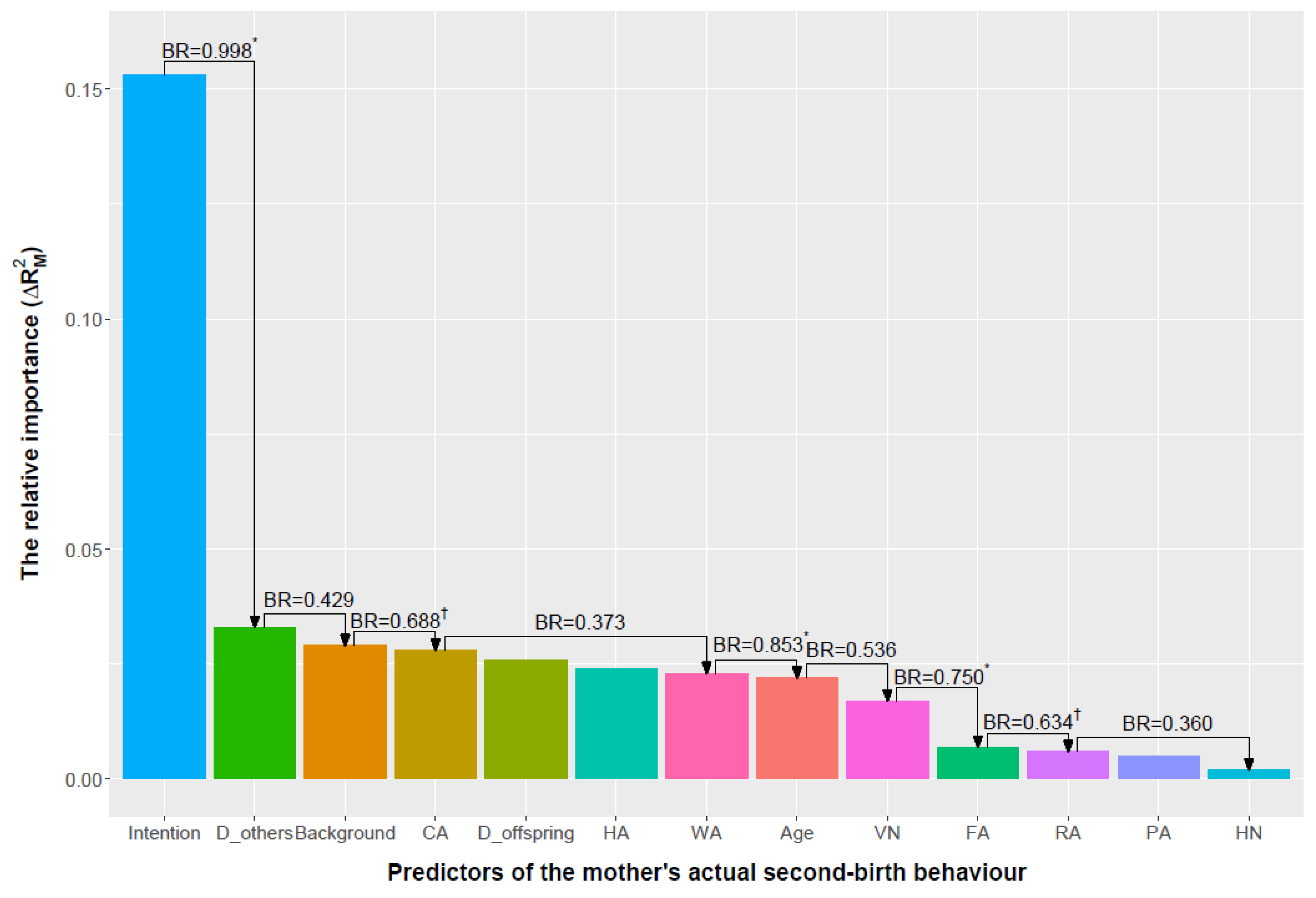

The formal dominance analysis indicates the relative-importance rankings of predictors of actual fertility behavior in the current sample (

Figure 4). Fertility intentions were evidently the most important predictor of the mother’s actual fertility behavior (Δ

=0.153). Following it, there were two other important predictors: perceived difficulties in family economy and house and work-family balance (Δ

=0.033); background factors (Δ

=0.029). Bootstrap resampling indicated that these two categories of factors were similarly important. Following them, there were four important predictors: the firstborn child’s fertility attitude (Δ

=0.028), perceived difficulty in rearing and educating two children (Δ

=0.026), husband’s attitude (Δ

=0.024), and the mother’s own attitudes (Δ

=0.023); they were similarly important predictors of fertility behavior, as the ranking of relative importance or dominance between any pair of them was not reproducible in more than 60% of bootstrap samples. Finally, consistent with the GLM, the non-significant predictors were also the least important predictors of the actual second-birth behavior between the two surveys: the injunctive norms from friends/colleagues (Δ

=0.007), the injunctive norms from peer relatives (Δ

=0.006), the injunctive norms from parents/parents-in-law (Δ

=0.005), and the number of children among peer relatives and friends/colleagues (Δ

=0.002).

Discussion

By integrating the theory of planned behavior in social psychology and two different evolutionary approaches to human behavior, i.e. behavioral ecology and cultural evolution, the author proposes the evolutionary framework of planned reproductive behavior and a series of theoretical predictions about the relative contributions of different fertility-related factors to mothers’ second-birth behavior. The longitudinal survey data from China fully or partly support eight of 11 predictions. The findings from the study might have some potential implications for understanding low-fertility behavior in modern societies.

Firstly, the relationship between fertility intention and actual fertility behavior has two contrasting implications. On the one hand, fertility intention was the central predictor of fertility behavior and substantially mediated the effects of some key predictors such as age and the descriptive norms from peer relatives and friends/colleagues, which were mainly significant and important at the intention stage (

Table 2). Thus, it is helpful to analyze fertility intentions or motivation in behavioral analysis: Significant predictors of a mediator have a higher power to be detected than those of ultimate response (58). In other words, if we just focus on fertility behavior itself, many important predictors might be hard to detect. For example, husband’s fertility attitude was not a

direct significant predictor of fertility behavior, but it was the most important predictor of fertility intentions. In the light that previous motivation analyses were mainly conducted in population studies, some anthropologists have called for an effort to reach an evolutionary understanding of the motivational mechanisms underlying human fertility (22, 23). The current study represents a small step towards the goal. On the other hand, fertility behavior is generally not completely intention driven or under volitional control (59); thus, important predictors of intentions and actual behavior may differ. Consequently, it is also not advisable to substitute the analysis of fertility intentions for that of fertility behavior. Rather, it is better to have a comprehensive analysis of both phases.

Secondly, the current study substantiates both theoretically and empirically the idea of collective decision-making in family reproduction. Previously, Smith’s anthropological study of Igbo-speaking Nigeria well illustrated “fertility decision-making…cannot be understood as individual or even dyadic, because a much wider spectrum of voices and interests have a say and must be considered in the social reproduction of families” (60). Unfortunately, although economists and demographers have touched on collective decision-making in fertility, their focus has been mainly on couples (40, 61, 62). For example, Browning and Chiappori (40) proposed a model on (two-person) household behavior such as fertility, savings and portfolio choices; according to this model, intra-household collective decision-making was a process of maximization of the sum of two persons’ utility weighted by their decision-making power, which was a response to external economic environment like relative income. By contrast, the argument here for collective decision-making in family reproduction takes an inclusive view and considers more stakeholders of reproduction, from both the genetic benefit and the parental-investment cost dimensions. Evidently, the generalized investment/cost dimension—i.e., there are a number of investors/stakeholders and a given stakeholder’s bargaining power in reproductive decision-making is associated with his/her parental investment, including not only money but also time, food, protection, etc.—gained more support from empirical data: Those investing more displayed larger power and those investing nothing showed no power. For instance, in influencing the mother’s fertility intention, the injunctive norms from parents/parents-in-law, who generally invest substantially in grandchildren in Chinese context, were evidently more important than those from peer relatives and friends/colleagues, who basically invest nothing in her offspring (

Figure 3;

Table 1). The generalized investment/cost dimension will be more justifiable, if we further notice some results in eusocial insects. Here, both queens, who lay the eggs, and workers—who undertake the task of rearing eggs and consequently invest more in offspring—can manipulate sex ratio in offspring: The former accomplish this through changing the primary sex ratio, while the latter by changing the secondary sex ratio (63, 64). As reviewed by Mehdiabadi et al. (65), “decades of research on sex-ratio conflict largely supported worker control” (e.g., refs. 66, 67).

There is an original finding as a corollary of the framework of collective decision-making in family reproduction: Already-born children could play a major role both in reproductive intentions and in actual behavior, which matched or was even more important than those factors emphasized by demographers e.g. age and education. It has been noticed for a long time that children should have a position in family decision-making, but they do not have one in reality: “Children are customarily excluded from the set of decision-making agents in the family, though they may be recognized as consumers of goods chosen and provided by loving or dutiful parents.” (68) As can be seen from dominance analysis, the firstborn child had an important role at the stage of fertility intention, but the role was evidently less important than that of the mother and her husband (

Figure 3). Only at the stage of actual fertility behavior, the firstborn child’s role matched that of his/her parents; in other words, at the stage of planning a further birth, couples could have not considered sufficiently the child’s attitude, but they were forced to do so at the latter stage, presumably owing to larger age and consciousness of the child as well as some tactics played by it (33, 69). The finding on the firstborn child’s role in family reproduction has an important implication for understanding the demographic transition in humans. As shown in

Table 1, the investment cost of further reproduction incurred for an already-born child would increase with the decline in total number of already-born children. In other words, with the progress of the demographic transition, an already-born child especially the firstborn one would act more and more as a player of the game of fertility limitation, besides husband and wife (e.g., ref. 70). By contrast, in a time of natural fertility when a family generally had a large size and inter-birth interval was less than three years (71, 72), a firstborn even did not speak at the time of second-birth and thus had no chance to express his/her attitude towards further reproduction; even if he can speak later, his role was not as large as the case analyzed in the current study, as his role was discounted by the total number of children.

Thirdly, our study helps to clarify kin influence on women’s fertility and its role in human demographic transition. Newson et al. (73) once proposed an influential hypothesis: Social development promoted more contact with non-kin, who generally tended to give less pronatal advice (i.e., injunctive norms), which through the process of cultural evolution promoted declining fertility in modern societies. Their key idea about pronatal kin and less pronatal non-kin was somewhat reflected in the following statement: “people bias what they

say about reproduction, depending on who is

listening and whether or not they are genetically related.” According to the framework of collective decision-making, the more reasonable logic seems like this: “people bias what they

listen about reproduction, depending on who is

saying and whether or not the speaker would invest in their children.” In other words, through injunctive norms, kin influence surely matters, but might not work exactly in the way as proposed by these scholars. Actually, the sample in the current study showed no sufficient evidence for that kin were more pronatal than non-kin: The proportions of supportive norms were similar in peer kin and friends/colleagues and both were about 50%, a value higher than that in the inquired firstborn children (

SI Appendix B: Table A.2). Presumably, Newson et al. (73) mainly considered common genetic interests between kin in reproduction, but did not give sufficient attention to possible conflicts (e.g., refs. 44, 69, 74, 75). To conclude, this study does not fully support either theoretically or empirically the pronatal kin hypothesis for fertility decline in the demographic transition.

Fourthly, the analysis of the 2×2 cross of kin vs. non-kin in one dimension with injunctive norm vs. descriptive norm in the other one, illustrates cultural evolution of Chinese women’s fertility, a mechanism that cannot be easily predicted by behavioral ecology. At the time of the baseline survey, two years had passed since the implementation of the universal two-child policy in 2016 and a few mothers had been surrounded by two-child peers (

SI Appendix B: Table A.2). It is not strange that the mother then made second-child decisions not completely by asocial learning but partly by referring to peers; in other words, horizontal transmission, through frequency-dependent or conformist bias, played a role in diffusing the new two-child norm. Although in a reverse direction, such diffusion was similar as that of fertility-limitation norms during the demographic transition (49). Notice that the significance and importance of number of siblings in predicting fertility behavior might not be due to vertical cultural transmission; rather, the negative effect could be due to sibling competition for grandparental help in childcare (

Table 2; see ref. 30).

Finally, the findings in this study help to solve the debate mentioned at the beginning—what are really important factors underlying low-fertility behavior—and thus, have clear implications for population policies. Both views, i.e. ideational factors vs. constraints in raising children, make some sense; however, neither one is inclusive. On the one hand, the mother’s own fertility ideology was just one of the important predictors of her fertility intention and it cannot explain most of variance either in fertility intention or in fertility behavior. On the other hand, the frequently mentioned constraints in raising children were also not the most important predictors of fertility intentions; e.g., the firstborn child’s attitude explained more variance, but it has not received sufficient attention from either scholars or policy-makers. It is reasonable to say that the biases in two views stem from the omitting-variable problem, which further illustrates the merit of integrating different evolutionary approaches to the low-fertility issue and its countermeasures. From such an integrated view, all the important factors relevant to either fertility intentions or fertility behavior should be given due attention, which is advisable to be proportional to their relative importance. Only in this way, can the fertility-friendly policies be both inclusive and potentially effective in alleviating the challenge of lowest-low fertility.

There are some limitations with the study. First, the analyzed sample is not large and confined to China, which could have limited the power of statistical inferences and generalization of conclusions. Second, looking from a long-term perspective, a 2.5-year follow-up study is essentially a cross-sectional one; thus, it is hard to capture the dynamics of relative importance of fertility-related factors with time. The fertility transition—either to lower fertility or to higher fertility—has three different stages, i.e. origin, spread and maintenance (49); as a result, some factors, e.g. the family planning norm, that have only a limited effect on fertility at the stage of origin might have a major one at later stages (76). Hopefully, future studies can expand the current one, based on the data spanning a longer time period and broader geographic regions.

Materials & Methods

The Baseline and Follow-Up Surveys

The study was based on the longitudinal data from two waves of a fertility survey. The baseline survey was conducted in the Xi’an metropolitan area, Shaanxi Province of China, from December, 2017 to February, 2018, when the so-called universal two-child policy—i.e., almost all married couples were allowed to have two children (77)—had been implemented for about two years. According to the seventh National Population Census, the total fertility rate in the province was about 1.16 and that in the city was just 1.03 in 2020, reflecting the lowest-low fertility pattern in China (78). The respondents in the baseline survey were the mothers with one child, not pregnant with the second child yet, and 20‒44 years old. Before questionnaire survey, a judgmental sampling was implemented so that the final sample can roughly represent the Xi’an population at that time. All qualified mothers from 17 communities/villages in nine streets/towns belonging to four districts (two in main city, one in inner suburb and the last one in outer suburb) were sampled. Then, the selected mothers were interviewed by telephone and 541 effective questionnaires were collected in total. The follow-up survey was conducted from January to August, 2020 (this survey lasted for a long time, owing to the COVID-19 pandemic); in other words, it was about two and a half years after the baseline survey. All 541 mothers interviewed in the baseline survey were re-contacted by telephone, and 262 effective questionnaires were collected (i.e., effective follow-up rate ≈ 48%). There was no sign that follow-up attrition changed substantially characteristics of the mothers; e.g. mean values of age and fertility intention in the full baseline sample were specifically 33.53 years and 3.57, close to those values in the final follow-up sample (

SI Appendix B: Table A.2).

Fertility behavior, i.e. whether a one-child mother had a second child between the baseline and follow-up surveys, was measured with a question in the follow-up survey, ‘how many children do you have now?’ The mother’s fertility intention at the time of the baseline survey was measured with a Likert scale, ‘do you agree with the following statement: you have a plan to have a second child in the next two years? (Options: 1–completely agree; 2–rather agree; 3–neither agree nor disagree; 4–rather disagree; 5–completely disagree)’ The measurements of predictors in the baseline survey can be found in

SI Appendix A (Supplementary text) and SI Appendix B (Table A.1; Table A.2). They were classified into five groups: background factors; the mother’s fertility attitudes; the injunctive norms from the nuclear-family members, other kin and non-kin; the descriptive norms from parents, parents-in-law, peer relatives and peer non-kin; constraints (

SI Appendix B: Table A.2). Given that two surveys asked different questions, there was no problem of panel conditioning.

The two waves of the survey were approved by the Biomedical Ethics Committee of Xi’an Jiaotong University (Approval Nos. NO2017100 and NO2020002). Their conduction was in line with the Declaration of Helsinki and before a questionnaire survey, each interviewee was informed of the research purpose and expressed her consent to take part in it.

Statistical Modeling

Fertility intention was modelled as a continuous response variable in regression analysis and the OLS (ordinary least square) was used to estimate effects of predictors. It was predicted by the five groups of predictors mentioned above and together with such predictors, it predicted the actual second-birth behavior during the interval between two surveys.

Table 2 shows the coding of predictors in modeling.

The Likert scale of fertility intention was not collapsed into a binary variable as by some researchers, for the following three reasons. First, it has been suggested that such a scale meets the assumption of interval measurement, i.e. equal distance between points (79, 80). Second, modeling fertility intention as a continuous variable can take advantage of full information on the fine changes between categories that would otherwise be lost in collapsing (81, 82). Thirdly, modeling fertility intention as a continuous variable has a higher statistical power for detecting the effect of a given predictor (83, 84).

Given that most mothers did not produce a second child, a small proportion did, and only one mother produced more than one child (twins) during the between-survey interval, fertility behavior was modeled as a binary response variable: ‘0—still having only one child now’ vs. ‘1—having two or three children now.’ To analyze predictors’ effects on actual fertility behavior, the GLM (generalized linear modeling) was used and based on probit transformation rather than logit transformation, as the former led to a lower AIC value.

The dominance analysis was used to evaluate the relative importance of predictors of fertility intentions and the actual fertility behavior. The platform was R 4.4.1 (85) and the package used was dominanceanalysis (86). It is known that a given predictor’s contribution to explaining response variable, e.g. R2 in an OLS regression model, depends on the predictor’s sequence in entering the model and its association with other predictors (87). Dominance analysis calculates its contributions in all possible subset models, e.g. a model including just the predictor, a model including both the predictor and another predictor, etc. (88-90). By averaging these contribution values, dominance analysis gives an assessment of a predictor’s general contribution or general dominance. Through this way, dominance analysis gives a reasonable and intuitive estimation of predictors’ contribution, in the sense of being positive, robust to correlation between predictors, a decomposition of model’s goodness-of-fit index like R2, and able to evaluate relative importance of groups of predictors; thus, it is a recommended statistical tool for analyzing relative importance of predictors (87, 88). For the OLS regression models, dominance analysis uses explained R2 to represent a predictor’s relative importance. For the GLM models, it uses a series of pseudo-R2; Azen & Traxel (89) especially recommended McFadden’s index. The robustness of general dominance was evaluated by bootstrap re-sampling for 1,000 times, to see if the rankings of predictors’ relative importance could be reproducible reasonably well (i.e. the reproducibility ≥ 70%; see ref. 89).

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

J.L. designed the study, coordinated data collection, performed analyses, and wrote the paper.

Funding

This work was supported by National Social Science Fund of China (Grant Number 24BRK026) and Xi’an Municipal Government (Grant Numbers S2016102 & S2019155).

Data Availability Statement

R code for analyses is available at:

https://www.preprints.org/manuscript/202509.0246 (with detailed output of statistical analyses). For the sake of participants’ privacy, the raw data cannot be made public, but can be requested from the author under certain ethics agreement.

Acknowledgments

The author sincerely thanks Min Chen and Ling Xu for their help in collecting the data analyzed in the current work, Min Chen and Tongtong Shen for confirming the quality of such data in their master dissertation work, and Wenfang Dong for comments.

Conflicts of Interest

There are no competing interests to declare.

References

- M. Borgerhoff Mulder, The demographic transition: Are we any closer to an evolutionary explanation? Trends Ecol Evol. 1998, 13, 266–270. [CrossRef]

- X. Qiao, China’s population development, changes and current situation, reference to data of the Seventh Population Census. Popul Dev 2021, 27, 74–88.

- National Bureau of Statistics‚ Department of Population and Employment Statistics. China population & employment statistical yearbook 2023; China Statistics Press: Beijing, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Xinhua News Agency. China releases decision on third-child policy, supporting measures. 2021. Available online: http://english.www.gov.cn/policies/latestreleases/202107/20/content_WS60f6c308c6d0df57f98dd491.html (accessed on 21 July 2022).

- Liu, J.; Zhang, L. Fertility intention-based birth forecasting in the context of China’s universal two-child policy: an algorithm and empirical study in Xi’an City. J Biosoc Sci 2022, 54, 516–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Wu, S. From “fertility cost constraint” to “happiness value orientation”: the changes of the fertility concept of the urban “post-70s”, “post-80s” and “post-90s”. Northwest Popul J 2021, 42, 36–46. [Google Scholar]

- Mu, G.; Lin, J. The fertility-friendly society - risk and governance in the era of endogenous low fertility. Explor Free Views 2021, 56–69+178. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, X. The three-child policy and the construction of the new fertility culture. J Xinjiang Norm Univ (Edit Philos Soc Sci) 2022, 43, 76–83. [Google Scholar]

- Song, J.; et al. Deciphering and promoting constructive and accommodating measures in support of the three-child policy. J Chin Women’s Stud 2021, 48–82. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen. The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Hum Dec. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, J. Klobas, Fertility intentions: an approach based on the theory of planned behavior. Demogr Res. 2013, 29, 203–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, W. B. Differences between fertility desires and intentions: implications for theory, research and policy. Vienna Yearb Popul Res 2011, 9, 75–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klobas, J. Social psychological influences on fertility intentions: a study of eight countries in different social, economic and policy contexts. 2010. Available online: https://researchportal.murdoch.edu.au/esploro/outputs/report/Social-psychological-influences-on-fertility-intentionsA/991005544790207891#file-0 (accessed on 7 December 2023).

- Erfani. Low fertility in Tehran, Iran: the role of attitudes, norms and perceived behavioural control. J Biosoc Sci 2017, 49, 292–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciritel, A.-A.; Rose, A. D.; Arezzo, M. F. Childbearing intentions in a low fertility context: the case of Romania. Genus 2019, 75, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billari, F. C.; Philipov, D.; Testa, M. R. Attitudes, norms and perceived behavioural control: explaining fertility intentions in Bulgaria. Eur J Popul. 2009, 25, 439–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dommermuth, L.; Klobas, J.; Lappegård, T. Now or later? The theory of planned behavior and timing of fertility intentions. Adv Life Course Res 2011, 16, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Lummaa, V. Whether to have a second child or not? An integrative approach to women’s reproductive decision-making in current China. Evol Hum Behav 2019, 40, 194–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llorente-Marrón, M.; Díaz-Fernández, M.; Méndez-Rodríguez, P. Ranking fertility predictors in Spain: a multicriteria decision approach. Ann Oper Res 2022, 311, 771–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letizia, M.; Daniele, V.; Anna, G. Fertility intentions and outcomes: implementing the theory of planned behavior with graphical models. Adv Life Course Res 2015, 23, 14–28. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhnt, A.-K.; Trappe, H. Channels of social influence on the realization of short-term fertility intentions in Germany. Adv Life Course Res 2016, 27, 16–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Međedović, J. Evolutionary behavioral ecology and psychopathy; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Mcallister, L. S.; Pepper, G. V.; Virgo, S.; Coall, D. A. The evolved psychological mechanisms of fertility motivation: hunting for causation in a sea of correlation. Philos Trans R Soc B-Biol Sci 2016, 371, 20150151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Borgerhoff Mulder, Tradeoffs and sexual conflict over women’s fertility preferences in Mpimbwe. Am J Hum Biol. 2009, 21, 478–487. [CrossRef]

- Shenk, M. K. Testing three evolutionary models of the demographic transition: patterns of fertility and age at marriage in urban south India. Am J Hum Biol 2009, 21, 501–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shenk, M. K.; Towner, M. C.; Kress, H. C.; Alam, N. A model comparison approach shows stronger support for economic models of fertility decline. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2013, 110, 8045–8050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snopkowski, K.; Kaplan, H. A synthetic biosocial model of fertility transition: testing the relative contribution of embodied capital theory, changing cultural norms, and women’s labor force participation. Am J Phys Anthropol 2014, 154, 322–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutigliano, R.; Lozano, M. Do I want more if you help me? The impact of grandparental involvement on men’s and women’s fertility intentions. Genus 2022, 78, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P. G.; Zhan, H. J.; Liu, J.; Barrett, P. M. Does the one-child generation want more than one child at their fertility age? Fam Relat 2022, 71, 494–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Liu, J.; Lummaa, V. Intention to have a second child, family support and actual fertility behavior in current China: an evolutionary perspective. Am J Hum Biol 2022, 34, e23669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harknett, K.; Billari, F.C.; Medalia, C. Do family support environments influence fertility? Evidence from 20 European countries. Eur J Popul 2014, 30, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, W. D. The genetical evolution of social behaviour. I. J. Theor. Biol. 1964a, 7, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trivers, R.L. Social evolution; The Benjamin/Cummings Publishing Company, Inc.: Menlo Park, CA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Trivers, R. L. Parental investment and sexual selection. Sexual selection and the descent of man, 1871–1971; Campbell, B., Ed.; Aldine: Chicago, IL, 1972; pp. 52–95. [Google Scholar]

- Sear, R. Parenting and families. In Evolutionary psychology: a critical introduction, ed Swami V; Wiley-Blackwell: Oxford, England, 2011; pp. 215–250. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen. Constructing a TPB questionnaire: conceptual and methodological considerations. 2002. Available online: http://www-unix.oit.umass.edu/~aizen/pdf/tpb.measurement.pdf (accessed on 10 November 2022).

- Miu, E.; Colleran, H. Female friendship and the cultural transmission of low-fertility values: Evidence from rural Poland. PNAS Nexus 2025, 4, pgaf113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cant, M. A.; Johnstone, R. A. Reproductive conflict and the separation of reproductive generations in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2008, 105, 5332–5336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahdenperä, M.; Gillespie, D. O. S.; Lummaa, V.; Russell, A. F. Severe intergenerational reproductive conflict and the evolution of menopause. Ecol Lett 2012, 15, 1283–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browning, M.; Chiappori, P. A. Efficient intra-household allocations: a general characterization and empirical tests. Econometrica 1998, 66, 1241–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavas, S.; De Jong, J. Exploring the mechanisms through which social ties affect fertility decisions in Turkey. J Marriage Fam 2020, 82, 1250–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samandari, G.; Speizer, I. S.; O’connell, K. The role of social support and parity on contraceptive use in Cambodia. Int Perspect Sex Reprod Health 2010, 36, 122–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaffnit, S. B.; Sear, R. Support for new mothers and fertility in the United Kingdom: Not all support is equal in the decision to have a second child. Popul Stud-J Demogr 2017, 71, 345–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sear, R. Family and fertility: Does kin help influence women’s fertility, and how does this vary worldwide? Popul Horiz 2018, 14, 18–34. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, E. D. Sarotra ny fiainana: fertility, family planning, and social networks in Highland Madagascar. Doctor of Philosophy, University of California, Berkeley, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Stulp, G.; Barrett, L. Do data from large personal networks support cultural evolutionary ideas about kin and fertility? Soc Sci-Basel 2021, 10, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, R.; Richerson, J. Culture and the evolutionaryprocess 1985.

- Cavalli-Sforza, L. L. M. W. Feldman, Cultural transmission and evolution; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Colleran, H. The cultural evolution of fertility decline. Philos Trans R Soc B-Biol Sci 2016, 371, 20150152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, H.; Lancaster, J. B.; Tucker, W. T.; Anderson, K. G. Evolutionary approach to below replacement fertility. Am J Hum Biol 2002, 14, 233–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mace, R. When to have another baby: a dynamic model of reproductive decision-making and evidence from Gabbra pastoralists. Ethol Sociobiol 1996, 17, 263–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgerhoff Mulder, M. Optimizing offspring: the quantity-quality tradeoff in agropastoral Kipsigis. Evol Hum Behav 2000, 21, 391–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berrington, S. Pattaro, Educational differences in fertility desires, intentions and behaviour: a life course perspective. Adv Life Course Res. 2014, 21, 10–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hašková, H.; Pospíšilová, K. Factors contributing to unfulfilment of and changes in fertility intentions in Czechia. Anthropol Res Stud 2019, 15–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, S.; Bookstein, F. L.; Fieder, M. Socioeconomic status, education, and reproduction in modern women: an evolutionary perspective. Am J Hum Biol 2010, 22, 578–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, M. Contemporary topics in low fertility: late transitions to parenthood and low fertility in East Asia; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lawson, D. W.; Mace, R. Optimizing modern family size. Hum. Nat.-Interdiscip. Biosoc. Perspect. 2010, 21, 39–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kenny, D. A.; Judd, C. M. Power anomalies in testing mediation. Psychol Sci 2014, 25, 334–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen. From intentions to actions: a theory of planned behavior. In Action control: from cognition to behavior; Kuhl, J, Beckmann, J, Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 1985; pp. 11–39. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, D. J. Having people: fertility, family and modernity in Igbo-speaking Nigeria. Doctor of Philosophy, Emory University, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Testa, M. R.; Bolano, D. When partners’ disagreement prevents childbearing: a couple-level analysis in Australia. Demogr Res 2021, 44, 811–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, E.; Mcdonald, E.; Bumpass, L. L. Fertility desires and fertility - hers, his, and theirs. Demography 1990, 27, 579–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- W. D. Hamilton, The genetical evolution of social behaviour. J. Theor. Biol. 1964b, 7, 17–52. [CrossRef]

- Passera, L.; Aron, S.; Vargo, E. L.; Keller, L. Queen control of sex ratio in fire ants. Science 2001, 293, 1308–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehdiabadi, N. J.; Reeve, H. K.; Mueller, U. G. Queens versus workers: sex-ratio conflict in eusocial Hymenoptera. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2003, 18, 88–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivers, R.L.; Hare, H. Haplodiploidy and evolution of social insects. Science 1976, 191, 249–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sundström, L.; Chapuisat, M.; Keller, L. Conditional manipulation of sex ratios by ant workers: A test of kin selection theory. Science 1996, 274, 993–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lundberg, S.; Pollak, R. A. Bargaining and distribution in marriage. J Econ Perspect 1996, 10, 139–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Duan, C.; Lummaa, V. Parent-offspring conflict over family size in current China. Am J Hum Biol 2017, 29, e22946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Lummaa, V. An evolutionary approach to change of status-fertility relationship in human fertility transition. Behav Ecol 2014, 25, 102–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, L. Some data on natural fertility. Eugen Quart 1961, 8, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sear, R.; Mace, R. Who keeps children alive? A review of the effects of kin on child survival. Evol Hum Behav 2008, 29, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newson, L.; Postmes, T.; Lea, S. E. G.; Webley, P. Why are modern families small? Toward an evolutionary and cultural explanation for the demographic transition. Pers Soc Psychol Rev 2005, 9, 360–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; et al. Post-marital residence patterns and the timing of reproduction: evidence from a matrilineal society. Proc R Soc B-Biol Sci 2023, 290, 20230159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, T.; et al. Reproductive competition between females in the matrilineal Mosuo of southwestern China. Philos Trans R Soc B-Biol Sci 2013, 368, 20130081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, K. L.; Hackman, J.; Schacht, R.; Davis, H. E. Effects of family planning on fertility behaviour across the demographic transition. Sci Rep 2021, 11, 8835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xinhua News Agency. The CPC Central Committee recommendations for the 13th five-year plan for economic and social development. 2015. Available online: www.china.org.cn/chinese/2015-11/03/content_36969613.htm (accessed on 30 July 2020).

-

Office of the Leading Group of the State Council for the Seventh National Population Census, China Population Census Yearbook 2020, Book 3; China Statistics Press: Beijing, China, 2022.

- Thomson, E.; Brandreth, Y. Measuring fertility demand. Demography 1995, 32, 81–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kan, M. Are gender attitudes and gender division of housework and childcare related to fertility intentions in Kazakhstan? Genus 2023, 79, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, P.; et al. Awareness, intention, (in)action: individuals’ reactions to data breaches. ACM Trans Comput-Hum Interact 2023, 30, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atalay, K.; Li, A.; Whelan, S. Housing wealth and fertility: Australian evidence. In The University of Sydney Economics Working Paper Series; ed Sydney Uo (Camperdown), 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Shentu, Y.; Xie, M. G. A note on dichotomization of continuous response variable in the presence of contamination and model misspecification. Stat Med 2010, 29, 2200–2214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedorov, V.; Mannino, F.; Zhang, R. M. Consequences of dichotomization. Pharm Stat 2009, 8, 50–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: a language and environment for statistical computing version 4.4.1. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Bustos Navarrete, C.; Coutinho Soares, F. dominanceanalysis: dominance analysis), R package version 2.1.0. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, X.; Gu, X. Evaluation of predictors’ relative importance: methods and applications. Adv Psychol Sci 2023, 31, 145–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azen, R.; Budescu, D. V. The dominance analysis approach for comparing predictors in multiple regression. Psychol Methods 2003, 8, 129–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azen, R.; Traxel, N. Using dominance analysis to determine predictor importance in logistic regression. J Educ Behav Stat. 2009, 34, 319–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coutinho Soares, F. Exploring predictors’ importance in binomial logistic regressions. 2024. Available online: https://mirrors.cqu.edu.cn/CRAN/web/packages/dominanceanalysis/vignettes/da-logistic-regression.html (accessed on 20 October 2024).

- Kaplan, H.; Hill, K.; Lancaster, J.; Hurtado, A. M. A theory of human life history evolution: diet, intelligence, and longevity. Evol Anthropol 2000, 9, 156–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Zhang, Y. Parental childcare support, sibship status, and mothers’ second-child plans in urban China. Demogr Res 2019, 41, 1315–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L. A study on the characteristics, trend, and problems of family structural changes in China: Based on the analysis of the national census micro-data. J Peking Univ (Philos Soc Sci) 2024, 61, 140–151. [Google Scholar]

Figure 1.

The evolutionary framework of planned reproductive behavior. Each solid arrow refers to a direct effect; a dashed arrow indicates that a predictor could bypass intention to exert a potential direct influence on behavior. Within each category of predictors, details are listed in bullets. For the relationships between the framework and Ajzen’s theory of planned behavior, and between it and the framework of collective reproductive decision-making, see the text.

Figure 1.

The evolutionary framework of planned reproductive behavior. Each solid arrow refers to a direct effect; a dashed arrow indicates that a predictor could bypass intention to exert a potential direct influence on behavior. Within each category of predictors, details are listed in bullets. For the relationships between the framework and Ajzen’s theory of planned behavior, and between it and the framework of collective reproductive decision-making, see the text.

Figure 2.

The illustration of some kin of a potential second child. For each double-headed arrow, the number on it refers to the coefficient of genetic relatedness between two persons at the ends of it (half-sibling and false paternity are not considered here); width and length of it are proportional and inversely proportional to the coefficient, respectively. P.—paternal/father’s. M.—maternal/mother’s.

Figure 2.

The illustration of some kin of a potential second child. For each double-headed arrow, the number on it refers to the coefficient of genetic relatedness between two persons at the ends of it (half-sibling and false paternity are not considered here); width and length of it are proportional and inversely proportional to the coefficient, respectively. P.—paternal/father’s. M.—maternal/mother’s.

Figure 3.

The relative importance or dominance of predictors of the mother’s second-child intention in terms of their contribution to the goodness-of-fit of the OLS regression (the sum of each predictor’s contribution Σ(Δ) = model’s R2 = 0.422). BR—reproducibility of the rankings of given predictors’ relative importance in 1,000 bootstrap samples; when more than two predictors are included under a BR connection line, none of BRs of pairs of predictors are above 0.60 (parallel to marginal significance, a BR between 0.60 and 0.70 is denoted as marginally significant and marked with a dagger; a BR ≥ 0.70 is denoted as significant and marked with an asterisk). HA—husband’s attitude towards second childbirth, i.e. whether the mother under question should reproduce a second child or not. WA—the mother’s own fertility attitudes. HN—number of children among horizontal or peer social-network members (peer relatives; peer friends/colleagues). PA—attitudes of parents/parents-in-law towards second childbirth. CA—the firstborn child’s attitude towards second childbirth. Age—the mother’s age at the time of the baseline survey. D_offspring—perceived potential difficulty in rearing and educating two children. RA—peer relatives’ attitudes towards second childbirth. FA—peer friends/colleagues’ attitudes towards second childbirth. Background—personal and family background factors, including family settlement, the mother’s education, household disposable income in the last year and the firstborn child’s sex. VN—number of children in vertical or parental generation members, i.e. parents or parents in law. D_others—perceived difficulties other than those in rearing and educating two children (more specifically, financial & housing conditions and work-family conflicts).

Figure 3.

The relative importance or dominance of predictors of the mother’s second-child intention in terms of their contribution to the goodness-of-fit of the OLS regression (the sum of each predictor’s contribution Σ(Δ) = model’s R2 = 0.422). BR—reproducibility of the rankings of given predictors’ relative importance in 1,000 bootstrap samples; when more than two predictors are included under a BR connection line, none of BRs of pairs of predictors are above 0.60 (parallel to marginal significance, a BR between 0.60 and 0.70 is denoted as marginally significant and marked with a dagger; a BR ≥ 0.70 is denoted as significant and marked with an asterisk). HA—husband’s attitude towards second childbirth, i.e. whether the mother under question should reproduce a second child or not. WA—the mother’s own fertility attitudes. HN—number of children among horizontal or peer social-network members (peer relatives; peer friends/colleagues). PA—attitudes of parents/parents-in-law towards second childbirth. CA—the firstborn child’s attitude towards second childbirth. Age—the mother’s age at the time of the baseline survey. D_offspring—perceived potential difficulty in rearing and educating two children. RA—peer relatives’ attitudes towards second childbirth. FA—peer friends/colleagues’ attitudes towards second childbirth. Background—personal and family background factors, including family settlement, the mother’s education, household disposable income in the last year and the firstborn child’s sex. VN—number of children in vertical or parental generation members, i.e. parents or parents in law. D_others—perceived difficulties other than those in rearing and educating two children (more specifically, financial & housing conditions and work-family conflicts).

Figure 4.

The relative importance or dominance of predictors of the mother’s second-birth behavior in terms of their contribution to the goodness-of-fit of the GLM regression (the sum of each predictor’s contribution Σ(Δ) = the model’s McFadden’s = 0.375). Intention—the mother’s intention to have a second child at the time of the baseline survey. For other notes (BR, D_others, Background, etc.), see the legend of Figure 3. Based on the regression analysis and dominance analysis, it can be seen that the prediction P6 is supported. At the stage of second-child intention, only perceived difficulty in rearing and educating two children was a significant predictor; it was ranked the seventh one among the predictors analyzed and accounted for about 5.931% of total R2. However, at the stage of actual fertility behavior, all three kinds of perceived difficulties or constraints were significant or marginally significant predictors; they were ranked second and fourth ones (with parallel ranks); together, they accounted for about 15.733% of total . The prediction P2a is partly supported: Only the firstborn child’s but not the husband’s fertility attitude significantly affected the mother’s actual second-birth behavior. Finally, the prediction P2b is not supported: There was no sufficient evidence, in terms of the reproducibility higher than 60% in bootstrap samples, that injunctive norms from the mother’s husband and firstborn child were more important than her own fertility attitudes in predicting the actual fertility behavior. Based on the regression analysis and dominance analysis, it can be seen that the prediction P6 is supported. At the stage of second-child intention, only perceived difficulty in rearing and educating two children was a significant predictor; it was ranked the seventh one among the predictors analyzed and accounted for about 5.931% of total R2. However, at the stage of actual fertility behavior, all three kinds of perceived difficulties or constraints were significant or marginally significant predictors; they were ranked second and fourth ones (with parallel ranks); together, they accounted for about 15.733% of total . The prediction P2a is partly supported: Only the firstborn child’s but not the husband’s fertility attitude significantly affected the mother’s actual second-birth behavior. Finally, the prediction P2b is not supported: There was no sufficient evidence, in terms of the reproducibility higher than 60% in bootstrap samples, that injunctive norms from the mother’s husband and firstborn child were more important than her own fertility attitudes in predicting the actual fertility behavior.

Figure 4.

The relative importance or dominance of predictors of the mother’s second-birth behavior in terms of their contribution to the goodness-of-fit of the GLM regression (the sum of each predictor’s contribution Σ(Δ) = the model’s McFadden’s = 0.375). Intention—the mother’s intention to have a second child at the time of the baseline survey. For other notes (BR, D_others, Background, etc.), see the legend of Figure 3. Based on the regression analysis and dominance analysis, it can be seen that the prediction P6 is supported. At the stage of second-child intention, only perceived difficulty in rearing and educating two children was a significant predictor; it was ranked the seventh one among the predictors analyzed and accounted for about 5.931% of total R2. However, at the stage of actual fertility behavior, all three kinds of perceived difficulties or constraints were significant or marginally significant predictors; they were ranked second and fourth ones (with parallel ranks); together, they accounted for about 15.733% of total . The prediction P2a is partly supported: Only the firstborn child’s but not the husband’s fertility attitude significantly affected the mother’s actual second-birth behavior. Finally, the prediction P2b is not supported: There was no sufficient evidence, in terms of the reproducibility higher than 60% in bootstrap samples, that injunctive norms from the mother’s husband and firstborn child were more important than her own fertility attitudes in predicting the actual fertility behavior. Based on the regression analysis and dominance analysis, it can be seen that the prediction P6 is supported. At the stage of second-child intention, only perceived difficulty in rearing and educating two children was a significant predictor; it was ranked the seventh one among the predictors analyzed and accounted for about 5.931% of total R2. However, at the stage of actual fertility behavior, all three kinds of perceived difficulties or constraints were significant or marginally significant predictors; they were ranked second and fourth ones (with parallel ranks); together, they accounted for about 15.733% of total . The prediction P2a is partly supported: Only the firstborn child’s but not the husband’s fertility attitude significantly affected the mother’s actual second-birth behavior. Finally, the prediction P2b is not supported: There was no sufficient evidence, in terms of the reproducibility higher than 60% in bootstrap samples, that injunctive norms from the mother’s husband and firstborn child were more important than her own fertility attitudes in predicting the actual fertility behavior.

Table 1.

The expectation of parental investment in a potential second child by the mother and members in her social network.

Table 1.

The expectation of parental investment in a potential second child by the mother and members in her social network.

| The relationship with the mother |

Investment |

| The mother herself |

≈C/2a

|

| The mother’s partner |

≈C/2 |

| The mother’s firstborn child |

≈C/2b

|

| The mother’s parents/parents-in-law |

< C/2c

|

| The mother’s siblings |

<< C/2d

|

| The mother’s partner’s siblings |

<< C/2 |

| The mother’s friends |

0e

|

| The mother’s colleagues |

0 |

Table 2.

The estimation of the effects on the mother’s fertility intention and behaviora.

Table 2.

The estimation of the effects on the mother’s fertility intention and behaviora.

| Predictor |

Fertility intentionb

|

Fertility behaviorc

|

|

βd

|

CI.Le

|

CI.U |

β |

CI.L |

CI.U |

| Intention to have a second child in the baseline survey |

— |

— |

— |

-0.546***

|

-0.818 |

-0.304 |

| Settlement (ref. = urban communityf) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| rural village |

0.192 |

-0.167 |

0.551 |

0.345 |

-0.312 |

1.016 |

| Age |

0.053***

|

0.023 |

0.082 |

-0.052 |

-0.120 |

0.011 |

| Education (ref. = pre-college level) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| College level or above |

-0.117 |

-0.483 |

0.248 |

0.586†

|

-0.033 |

1.234 |

| Household disposable income in the last yearg

|

-0.020 |

-0.121 |

0.082 |

0.074 |

-0.108 |

0.261 |