Introduction

The use of plants for medicinal purposes has been on the increase because of the high cost of living and prevailing perception that medicinal plants are naturally safe, easy to prepare, readily available and non-toxic. Medicinal plants are essential for human health and sustainable healthcare due to their diverse bioactive compounds (Asiminicesie et al., 2024) these includes alkaloids, flavonoids, terpenoids, polyphenols, known for their antioxidants, anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial and anti-cancer properties (Mpeka et al., 2024). They remain a significant resources for traditional medicine, particularly in regions with limited access to modern healthcare. Many pharmaceutical drugs have originated from these plants, inspiring the development of a new medication (Asiminicesie et al., 2024).

Medicinal plants such as Mango, Baobab, African birch, Tamarind, Neem and others are widely distributed around the study area, these plants are used for the treatment, prevention and healing of diseases and injuries by the people living around the area and beyond: Mango leaves and bark (ulcer, typhoid and fever), African birch (cough), Baobab bark and fruit pulp extract (Diabetes and metal toxicity), Neem (malaria) while others are used as food (mango fruit, tamarind fruit, baobab leaves and fruit pulp). Many medicinal plants are grown in developing countries, where pollution is often more severe due to lax environmental regulations (Asiminicesei et al., 2024).

Heavy metals are groups of dense, non-biodegradable toxic compound that are found in various environmental media. Exposure to elevated level of heavy metals such as cadmium, lead, and mercury have been found to have adverse effect on medicinal plants. Starting from metals exposure in soil, water or air, this leads to variability of plants responses, during induction of oxidative stress, up regulation of antioxidants compounds and potential diversion of resources (Riyazuddin et al., 2022). The biosynthesis of these secondary metabolites may eventually be impacted by the cultivation of medicinal plants in the heavy metals contaminated environments leading to dramatic alteration in quality and quantity of these compounds (Pandey et al., 2023). This can result in a shortage of high-quality medicinal plants, making it more difficult for people to access these natural remedies (Huzen, 2023). Consumption of such plants can cause toxicity in certain organs of the human body, such as nephrotoxicity, neurotoxicity, hepatotoxicity, skin toxicity, and cardiovascular toxicity among others things (Mitra et al., 2022).

Heavy metals contamination above the permissible limits has been reported by Dghaim et al. (2015), Mafulul et al. (2024), and Sulaiman et al. (2024) with various carcinogenic and non-carcinogenic health risk to consumers. However, when studying the medicinal plants much attention is given to metals concentrations and potential health risk of the plants sold in the markets without considering the pharmaceutical quality and safety of the plants in their natural environments. Therefore this study aimed to assess the phytochemical contents, heavy metals concentration and potential human health risk of the medicinal plants around Koka hill Kiru Kano state Nigeria.

Materials and Methods

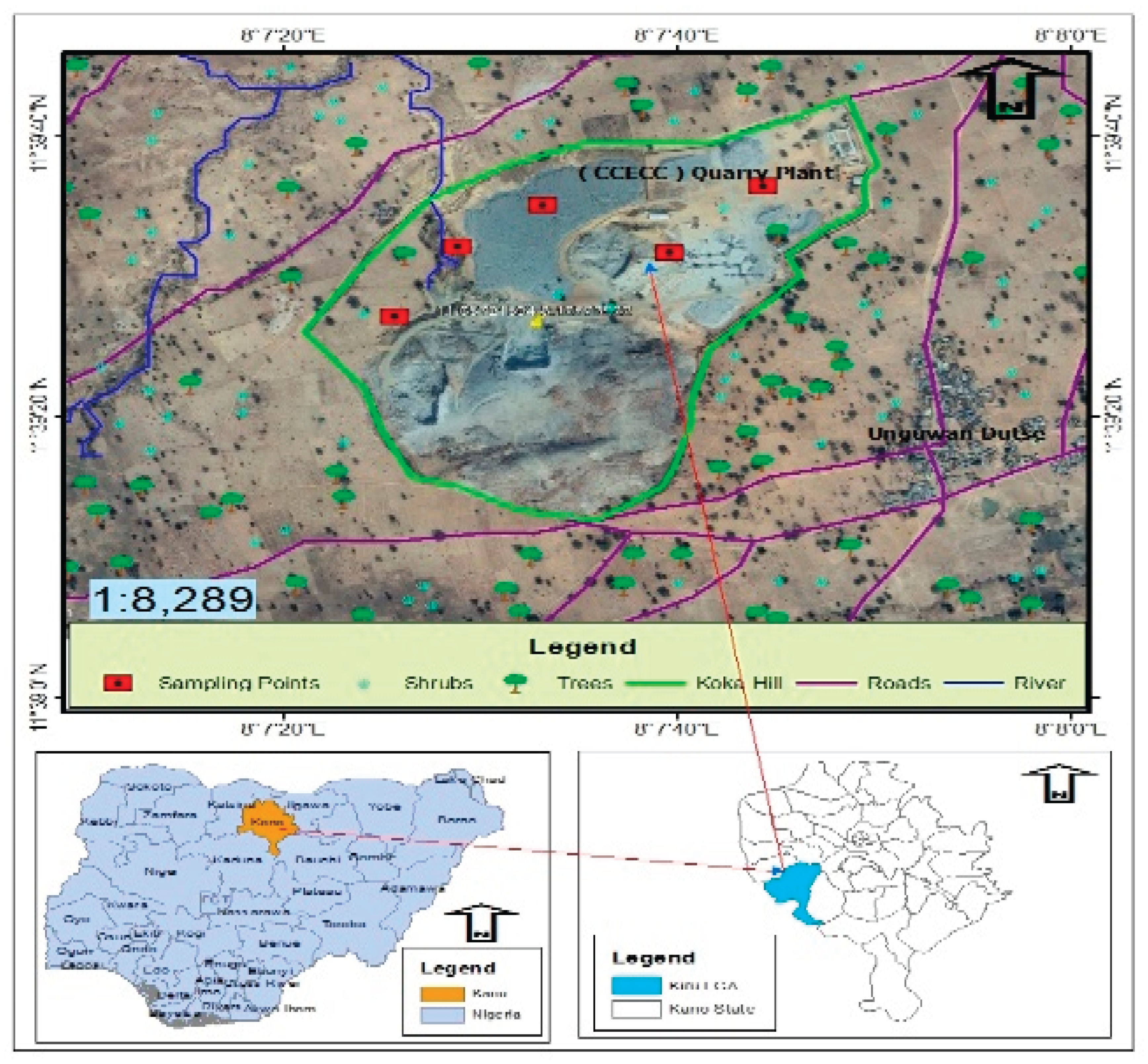

The study area is a rural settlement in Koka hill, Maraku ward Kiru local government area, which is located in the northern part of Kano state Nigeria (Figure 1.0). It has a land area of 927 Km2 and a population of about 264, 781 (NPC, 2006). On global scale the location lies between latitudes 11ᵒ43’408’’ to 11ᵒ43’590’’N and longitude 008ᵒ05’806’’ to 008ᵒ05’971’’E.

Figure 1.0.

Map of Koka Hill Kiru, Northwestern Nigeria.

Figure 1.0.

Map of Koka Hill Kiru, Northwestern Nigeria.

The medicinal plants samples were collected using composite sampling method, four medicinal trees Mango (Mangifera indica), Baobab (Adonsonia digitata), African birch (Anogeissus leiocarpus) and Neem (Azadirachta indica) leaves and barks were obtained. The samples were authenticated in the Herbarium department of Botany Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria. Each sample was thoroughly washed with distilled water and air dried for weeks.

The quantitative phytochemical assessment was conducted using the standard method described by AOAC, (2006). The flavonoid, alkaloid, saponin and phenol were determined in the leaves and bark of the plants.

Each powdered sample was digested according to standard method of digestion. 1g of the sample was weighed into 50 mL beaker; 2.5 mL of hydrochloric acid and 7.5 mL of nitric acid aqua regia solution (1:3) was added. The beaker containing the mixture were put on a hotplate set at a temperature range of 100-170 ℃ until when it was about to dry off or precipitate was observed. Removed and allow to cool, then added some drops of distilled water. The solution was mixed-up and transferred to funnel set with filter paper. The filtrate was measured and made up to 50 ml. Finally, digest were transferred to the sample bottle for AAS analysis.

The health risk of ingesting the metals in each sample was assessed by evaluating; Estimated Daily Intake (EDI), Target Hazard Quotient (HQ), Hazard Index (HI) and Carcinogenic Risk (CR).

The average estimated daily intake (EDI) of heavy metals which depends on metal concentration in plants and the consumption degree of the particular plants was calculated using equation 1 (USEPA, 2011).

where EDI is the average daily intake or dose by ingestion (mg/kg body weight/day); C is the heavy metal concentration in the medicinal plants (mg/kg); IR is the daily consumption rate (0.02 and 0.01 mgkg

-1day

-1 for adult and children respectively). W is the average body weight (60 and 15 kg for adult and children respectively).

The hazard quotient (HQ) characterizes the human health risk posed by heavy metal exposure were calculated using equation 2.

where RfD is the safe level of oral exposure (USEPA, 2011):

Hazard index were calculated by summed of hazard quotient of all five metals in medicinal plants as showed in equation 3.

If HQ or HI is equal to or above 1, the risk were considered unacceptable. As the HQ or HI increases, the risk also does. An index under 1.0 is assumed as safe and above 1 is fatal.

Oral Slope Factor SFo is signifying cancer severity, only three heavy metals were proven with certain SFs: 6.1 for Cd, 1.5 for As and 0.0085 for Pb (USEPA, 1997; USEPA 2011). CR of these metals in the medicinal plant were summed up to give total CR (equation 4). The CR values within 10

-6 to 10

-4 indicating no possible cancer developments.

Cumulative carcinogenic risk index was determine by summing the CR of each metal in medicinal plants as shown in equation 4.

Phytochemical and heavy metals concentrations in plants data were analyzed using one-way Analysis of variance (ANOVA) and the mean difference was separated using Tukey-Kramer's Multiple Comparison.

Results and Discussions

The mean proportion of phytochemicals alkaloid, flavonoid, saponin and phenol is presented in

Table 1.0. There was a significant difference among the medicinal plants analyzed, the mean phytochemical contents in

Mangifera indica leaves and bark ranged from 9.97±0.14 to 10.19±0.14% for alkaloid, 13.82±0.15 to 19.11±0.16% for Flavonoid, 4.07±0.12 to 4.45±0.15% for phenol and 5.34±0.41 to 10.01±0.12% for saponin. There was significant difference in phytochemical contents between the parts investigated, high amount of alkaloid and saponin was observed in bark of

M. indica than leaves while the leaves has the high amount of flavonoid and saponin. This results are in line with the finding of Alhaji

et al. (2023) who reported that the

Mangifera indica parts; flower, leaves, stem and seeds are rich in tannin, saponin, flavonoid, terpenes, phenol, steroid and alkaloid. The quality and quantity of secondary metabolites in

Mangifera indica parts investigated were significantly differed, highest flavonoid in flower (18.35±0.02%), alkaloid in stem (6.35±0.05%), phenol in flower (11.69±0.9%), Saponin in stem (6.94±0.03%) and Tannin in flower (5.24±0.3%) respectively was observed (Alhaji

et al., 2023).

The average phytochemical contents in leaves of Azadirachta indica differ significantly. The alkaloid, flavonoid, phenol and saponin contents were 14.24±0.37, 18.04±0.15, 6.94±0.14 and 9.84±0.15% respectively. The result of all the phytochemicals investigated was higher than the control sample. Similar result was obtained by Ujah et al. (2021) who showed that saponins, steroids and terpenes were mostly present, while tannins and glycosides were moderately present, and alkaloids, flavonoids, phenols and oxalic acid were least present. The presence of these phytochemical could account for the therapeutic uses of Neem.

The mean concentration of the phytochemicals of Anogeissus leiocarpus leaves differ significantly. The proportion of alkaloid, flavonoid, phenol and saponin were 26.36±0.29%, 37.31±0.33%, 27.26±0.33% and 25.01±0.41% respectively. The concentration of all phytochemicals was significantly higher than control samples. Bello et al. (2023) reported that the bark of Anogeissus leiocarpus contain alkaloid, flavonoid, saponin, phenol and tannin which are responsible for its pharmaceutical value.

The mean level of alkaloid, flavonoid, phenol and saponin in leaves and bark of Adansonia digitata differ significantly. The concentration of all investigated phytochemicals was significantly higher in bark than leaves, similar trend was observed between the leaves and bark of the control samples. The proportion of alkaloid, flavonoid, phenol and saponin in the leaves and bark of Adonsonia digitata ranged from 8.85±0.37 to 26.89±0.31, 17.70±0.34 to 37.86±0.31, 7.22±0.29 to 28.73±0.18 and 13.56±0.29 to 24.63±0.31% respectively. The result obtained in this study corroborated with finding of Silva et al. (2023) who reported that the Adonsonia digitata leaves, bark, root and fruits has significant amount of phytochemicals; alkaloid, phenol, flavonoid, glycosides and tannin. Similarly, Segunle et al. (2021) reported the quantitative phytochemical screening revealed that aqueous extract of Adonsonia digitata tree contained flavonoid (36.33 mg/100g), cardiac glycoside (31.46 mg/100g), saponin (23.26 mg/100g), alkaloid (24.86 mg/100g), tannin (19.28 mg/100g) and phenolic (17.06 mg/100g) respectively.

On comparison, the phytochemical contents of all the medicinal plants samples obtained from the study area were significantly higher than the control samples. This could be due to environmental stress such as quarry dust, heavy duty truck emission, machinery emission and other contaminants generated from the study area. Phytochemicals in the plants participates in the process of adaptation of the plants to environment and their quantity varies depending on the numerous ecological factors to which the plant was exposed (Zlatic et al., 2019). However, the heavy metals concentrations in the sample were also significantly higher than the control samples; this could also trigger the synthesis of these protective compounds for plants adaptation. In vitro study conducted by Ibrahim et al. (2017) reported that Cu and Cd enhance the synthesis of flavonoid, saponin, and phenolic, hence the medicinal important of Gynura procumbens as demonstrated by higher antibacterial activity under Cd and Cu stress. Moreover, Pandey et al. (2023) reported that the biosynthesis of these secondary metabolites may eventually be impacted by the cultivation of medicinal plants in heavy metals contaminated environments leading to dramatic alteration in quality and quantity of these substances.

Table 2.0 shows the result of heavy metals concentration (mgkg

-1) in the leaf and bark of the medicinal plants samples obtained from the study area. The level of Cd in the analyzed medicinal plant samples ranged from less than 0.0 to 0.78 mgkg

-1, the max concentration of cadmium in

Adansonia digitata bark and

Anogeissus leiocarpus leaves were found to be 0.06±0.11 and 0.78±0.11 mgkg

-1 respectively. The result obtained from this study showed that the Cd content in

Mangifera indica bark exceeded the maximum permissible limit set by WHO/FAO for medicinal plants.The levels of Cd in other samples were found to be below detection limit except

Anogeissus leiocarpus leave that were within the permissible limit set by WHO/FAO for metal in medicinal plants. The mean Cd concentration obtained in this study were in a close range of 0.24 to 0.93 mgkg

-1 reported by Al-Heety

et al. (2021) in the leaves of

Eucalyptus camaldulensis and

Conocarpus lancifolius grown adjacent to power generator in Ramadi city, Iraq. Similarly, Barbes

et al. (2023) reported that the Cd concentration in

Sambucus nigra and

Hypericum perforatum were 0.001-0.10 mgkg

-1 and 0.12-0.92 mgkg

-1 in various sampling unit in southeastern Romania. Cadmium is a toxic and carcinogenic metal. In addition to its carcinogenic properties, cadmium induces kidney disease, bone disease, and cardiovascular disease (Toxicological Profile for Cadmium, 2002). Low to moderate cadmium exposure resulted to hypertension, diabetes, carotid atherosclerosis, peripheral arterial disease, chronic kidney disease, myocardial infarction, stroke, and heart failure (Mitra

et al., 2022).

The level of Cr in the analyzed samples ranged between 23.25±0.39 and 36.30 ±0.39 mgkg-1. The max concentration of Cr in Mangifera indica, Adansonia digitata and Anogeissus leiocarpus were 36.30±0.39, 29.10±0.39 and 28.50±0.39 mgkg-1 respectively. The regulatory limit for Cr in consumed medicinal plants is not yet established by WHO/FAO. However, according to Rufa’i et al. (2019) the standard limit for Cr set by Canadian government is 1 ppm, when compared with the result obtained in this study, 90% of the analyzed samples exceed that limit. High concentration of Cr has been reported in African countries. The mean concentration of Cr in Azadirachta indica, Mangifera indica and Newbouldia laevis grown in the University of Ibadan Nigeria was 2.42, 1.53 and 1.84 ppm respectively (Rufa’I et al., 2019). Chromium is a toxic compound that has effect on different organ. Contact with chromium causes a variety of acute and chronic severe dermatological consequences, including contact dermatitis, systemic contact dermatitis, and skin cancer (Mitra et al., 2022).

The Cu concentration varied between 0.6±0.37 mgkg-1 and 8.16±0.37 mgkg-1. The max level of Cu in Anogesus leucarpus, Mangifera indica and Adansonia digitata was 8.16±0.37, 3.5±0.37 and 2.80±0.37 mgkg-1 respectively. The max concentration for Cu in consumed medicinal plants set by WHO/FAO is 10 mg/kg. The results obtained showed that 100% of the analyzed samples were within the permissible limit. The mean level of Cu in most commonly consumed herbs in UAE ranged between 1.44 and 156.24 mgkg-1 respectively (Dghaim et al., 2015). Copper is recognized as one of the vital micronutrient for living organism, however elevated exposure causes liver toxicity. Copper is well known to accumulate in the liver due to Wilson’s disease. Increased levels of copper may cause oxidative stress; therefore, hepatic copper deposition is not only pathognomonic, but also pathogenic (Mitra et al., 2022). Elevated hepatic copper levels are also observed in cholestatic liver diseases. However, they result from diminished biliary excretion of copper and are not a cause of hepatic infection (Deering et al., 1977: Yu et al., 2019).

The concentration of Pb in the analyzed samples ranged from 15.0±0.23 to 34.02±0.23 mgkg-1. The maximum concentration of lead in A. digitata bark, A. leiocarpus leaves, A. indica leaves and M. indica leaves was found to be 21.30±0.23, 24.00±0.23, 34.02±0.23 and 15.00±0.23 mgkg-1 respectively. The FAO/WHO max permissible limit of lead in consumed medicinal plants and herbs is 10 mgkg-1 (Dghaim et al., 2015). The obtained results shows that 66.6% of the analyzed samples exceed that limit. The level of lead in A. digitata leaves, M. indica bark and control samples was below detection limit. High concentration of Pb above permissible limit in medicinal plants and herbs has been reported in many countries: the mean concentration of Pb in most commonly used traditional herbs in UAE was 16.15, 21.76, 18.06 and 23.56 mgkg-1 in basil, sage, oregano, and thyme respectively (Dghaim et al., 2015). On contrary, the mean Pb concentrations in this study were significantly higher than 5.4 to 6.99 mgkg-1 reported by Al-Heety et al. (2021) in the leaves of Albizia lebbeck, Ficus microcarpa, Ziziphus spina-christi, Dodonaea viscose, Eucalyptus camaldulensis and Conocarpus lancifolius grown adjacent to power generator in Ramadi city, Iraq. ). Acute and chronic lead exposure leads to several toxic effects on the immune system and causes many immune responses, such as increased allergies, infectious diseases, and autoimmunity, as well as cancer (Hsiao et al., 2011). A high risk of lung, stomach, and bladder cancer in several demographic groups has been linked to lead exposure (Rousseau et al., 2007).

The concentration of Zn in the analyzed samples ranged between 33.63±0.40 to 5.90±0.40 mgkg-1. The max concentration in Azadirachta indica, Mangifera indica and Anogeissus leiocarpus was found to be 17.03±0.40, 19.02±0.40 and 33.63±0.40 mgkg-1 respectively. The obtained results revealed that the concentration of Zn in all the samples analyzed was below 50 mgkg-1 permissible limit set by FAO/WHO for consumed medicinal plants and herbs. Zinc is an essential micronutrient that is needed for physiological and biochemical processes, it is associated with plenty of enzymatic reactions via acting as a cofactor (Mitra et al., 2022). However, high zinc intake beyond permissible limits produces toxic effects on the immune system, blood lipoprotein levels, and copper level (ATSDR, 2007).

Health Risk Assessments

Non-Carcinogenic Risk

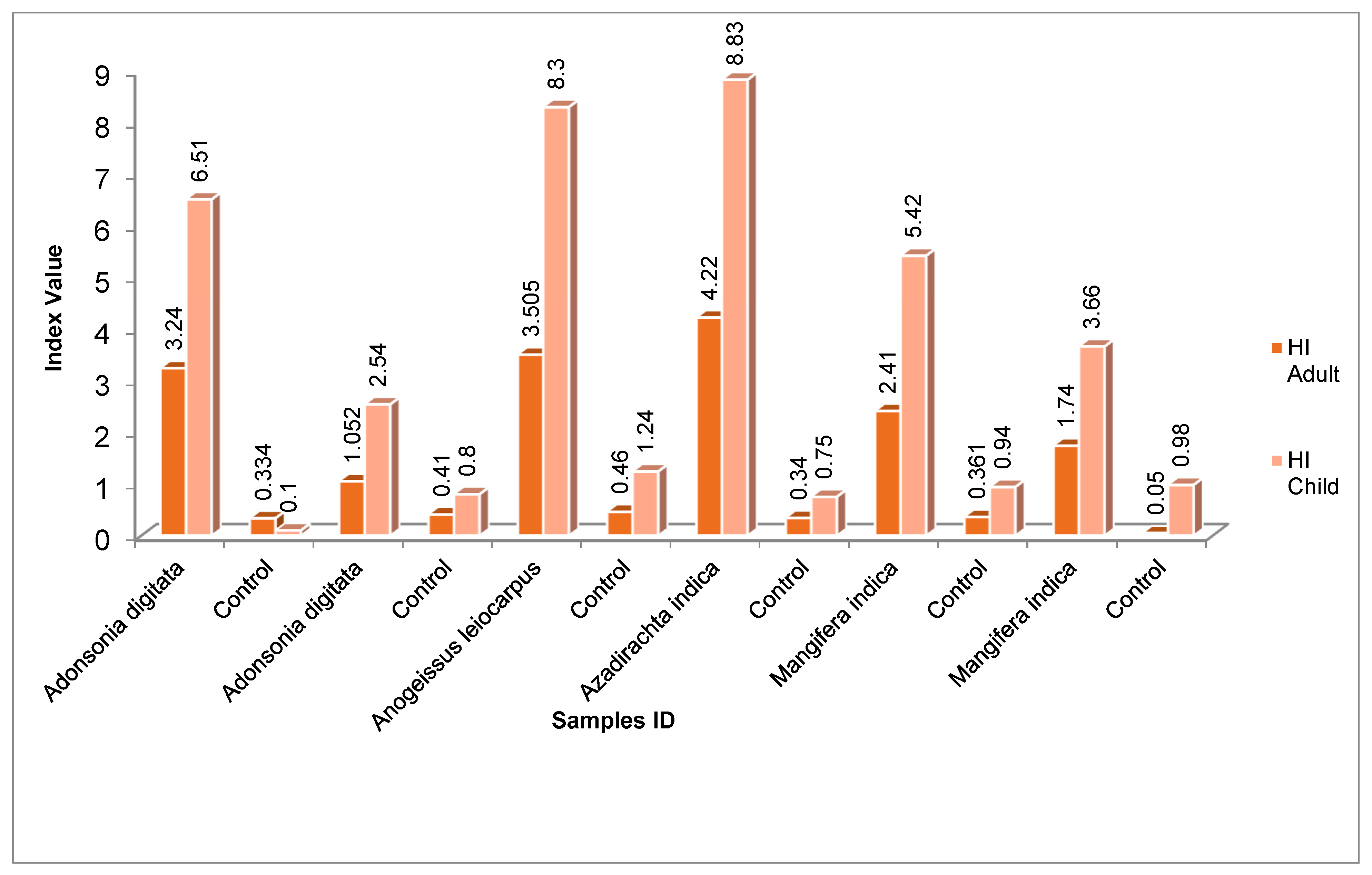

The non-carcinogenic risk of consumption of medicinal plants contaminate with heavy metals was estimated based on hazard quotients (HQ) and hazard index (HI). The mean HQ values of each metal analyzed ranged between <1 to 3.24 for adult and 0.10 to 6.57 for children. Among the metals; Pb and Cr have higher HQ values, the Max and Min HQ value for Pb was found in Azadirachta indica and Mangifera indica leaves 3.24 and 1.43 for adult and 6.57 and 4.57 for children respectively. However, the HQ values for other metal in the control samples were less than 1. The mean hazard index (HI) values in the analyzed medicinal plants ranged between 4.22 and 1.05 for adult and 2.54 to 8.30 for children, this indicated that consumption of these plants can pose a significant health threat especially among children. The finding conformed with the results of Mafulul et al. (2024) who reported that the HI values for all eight heavy metals in the studied medicinal plants were greater than 1, with V. amygdalina (47.3) recording the highest value for children and P. guajava (9.63) recording the lowest value for adults, the risk for children was 5 times higher than for adults. The obtained result however contradicted with findings of Suleiman et al. (2024) who reported that the HQ and HI values of the medicinal plants sold in Nigeria were below 1.

Table 3.0.

Hazard Quotient and Health Risk Index for Adults in the Medicinal Plants.

Table 3.0.

Hazard Quotient and Health Risk Index for Adults in the Medicinal Plants.

| Sample ID |

Plant

Part |

Hazard Quotients (mg/kg/day) |

Hazard

Index |

| Cd |

Cr |

Cu |

Pb |

Zn |

| Adonsonia digitata |

Bark |

* |

1.200 |

5×10-3

|

2.03 |

6.3×10-3

|

3.24 |

| Control |

|

* |

0.330 |

1.6×10-3

|

* |

2.16×10-3

|

0.334 |

| Adonsonia digitata |

Leaves |

* |

1.040 |

2.3×10-2

|

* |

1.01×10-2

|

1.073 |

| Control |

|

* |

0.384 |

7.7×10-3

|

* |

3.8×10-3

|

0.395 |

| Anogeissus leiocarpus |

Leaves |

0.02 |

1.140 |

6.8×10-2

|

2.30 |

3.7×10-2

|

3.565 |

| Control |

|

* |

0.380 |

2.26×10-2

|

* |

1.25×10-2

|

0.415 |

| Azadirachta indica |

Leaves |

* |

0.934 |

1.75×10-2

|

3.24 |

2.1×10-2

|

4.212 |

| Control |

|

* |

0.313 |

5.8×10-3

|

* |

7×10-3

|

0.340 |

| Mangifera indica |

Leaves |

* |

0.925 |

2.9×10-2

|

1.43 |

1.87×10-2

|

2.410 |

| Control |

|

* |

0.325 |

1.4×10-2

|

* |

6.3×10-3

|

0.361 |

| Mangifera indica |

Bark |

0.26 |

1.46 |

1.0×102

|

* |

8×10-3

|

1.740 |

| Control |

|

* |

0.485 |

3.3×10-4

|

* |

2.7×10-3

|

0.050 |

Figure 1.0.

Hazard Index for HM intake in Medicinal Plants for Adults and Children.

Figure 1.0.

Hazard Index for HM intake in Medicinal Plants for Adults and Children.

The result of the carcinogenic risk assessment of medicinal plants grown around the study area is presented in

Table 4.0. The average CR values ranged from 9.6×10

-5 to 1.53×10

-3;

Mangifera indica bark (1.58×10

-3) has the highest CR value indicating a significant possible cancer development for adults, while the CR values for other samples were within the threshold value of 1×10

-6 to 1×10

-4 indicated no possible cancer development (USEPA, 2011). The finding in this study corroborated with that of Barbes

et al. (2023) who reported that the calculated CR were 2.69×10

-5 to 7.57×10

-3 for children and 8.66×10

-6 to 1.62×10

-3 for adults in medicinal plants in southeastern Romania. This result however contradicted with the finding of Suleiman

et al. (2024) who reported that the CR value in medicinal plants sold in northern Nigeria ranged from 9.27×10

-8 to 1.48×10

-5 signifying no possible cancer development.