Submitted:

01 September 2025

Posted:

01 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

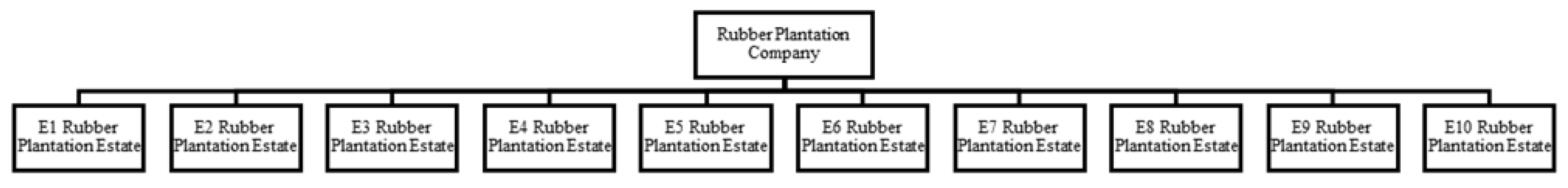

2.1. Study Area and Organizational Boundaries

2.2. Data Collection

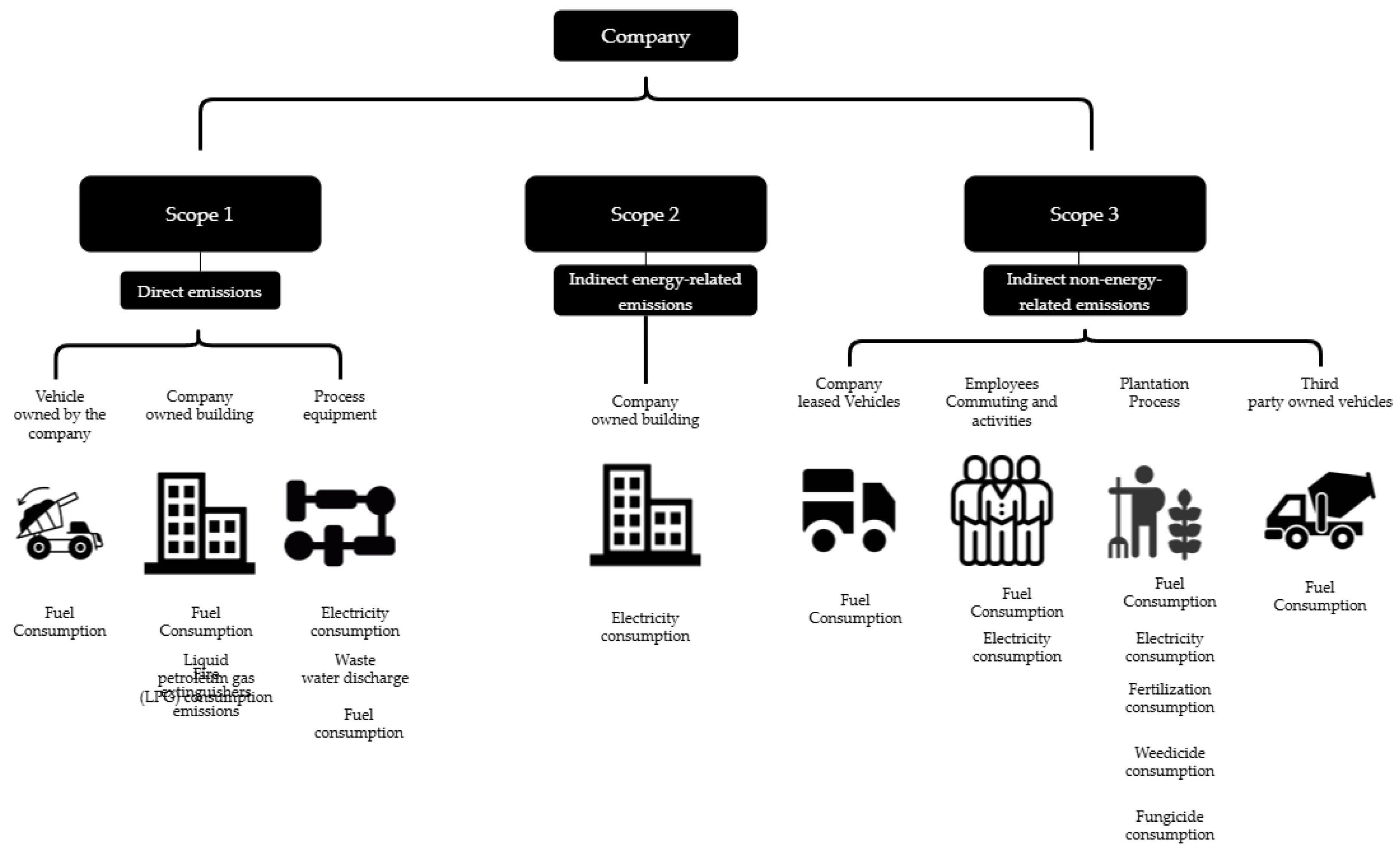

2.3. Carbon Footprint Methodology

2.4. Carbon Fixation Methodology

3. Results and Discussion

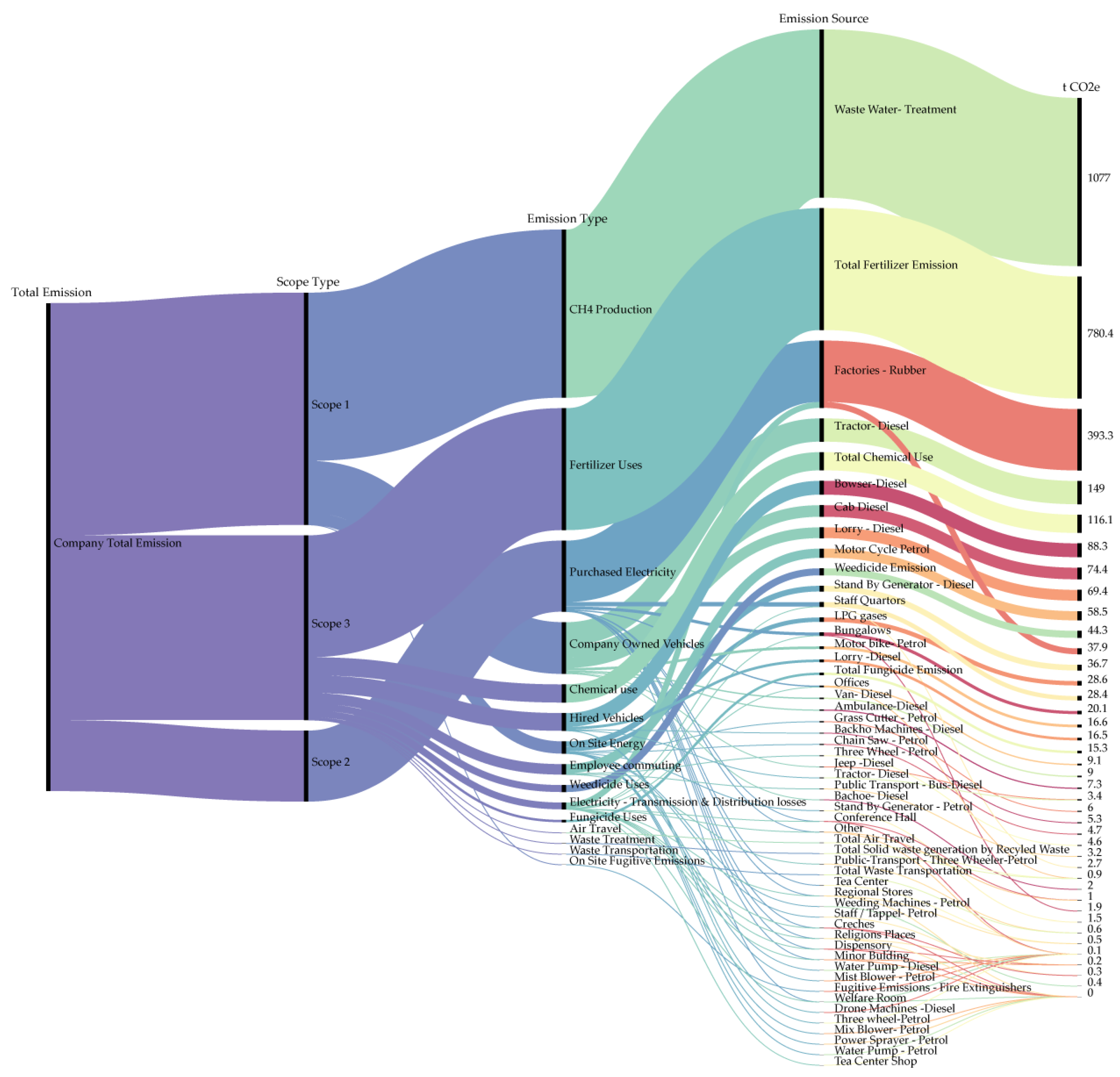

3.1. Organizational Carbon Footprint of Rubber Plantation Organization

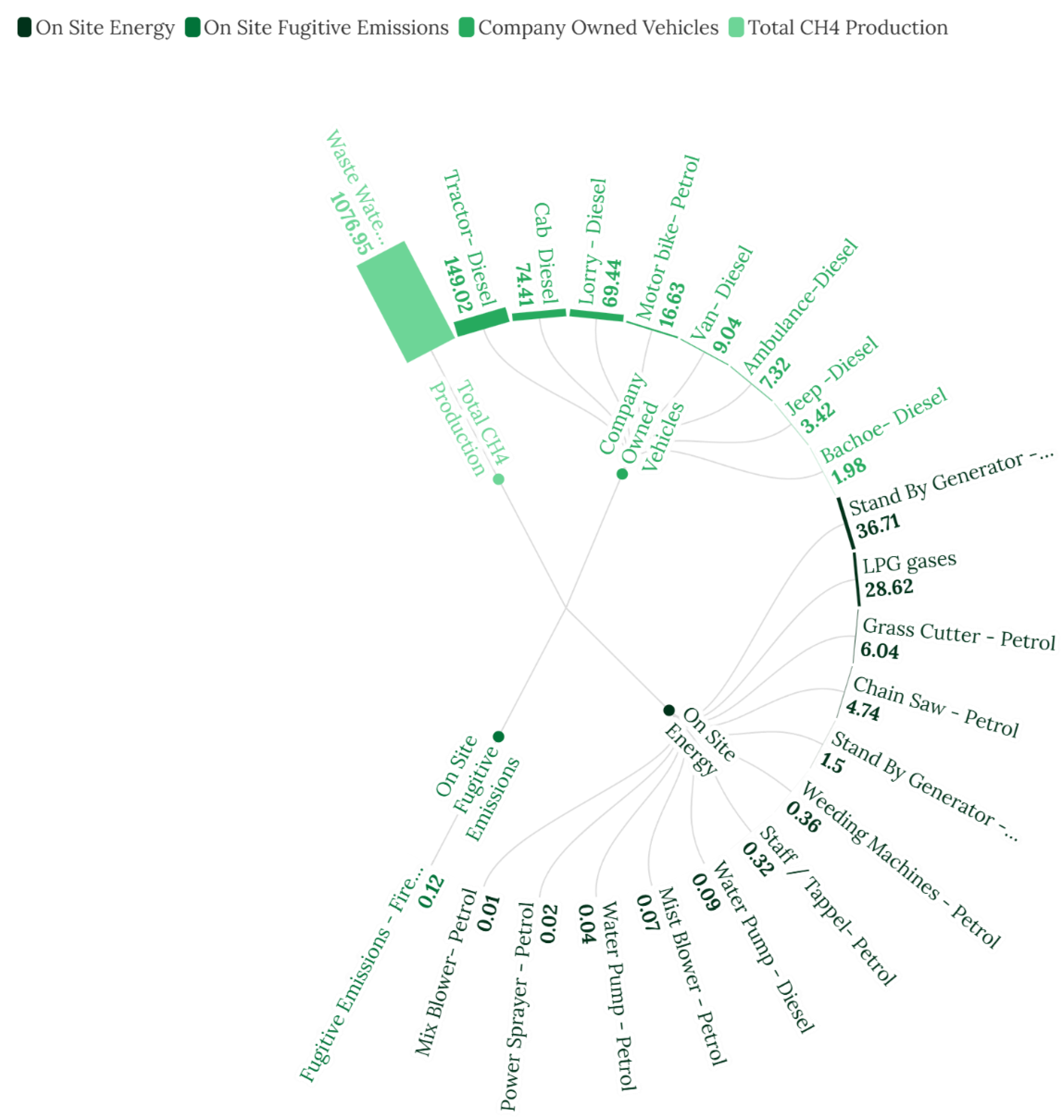

3.1.1. Scope 1 Emissions

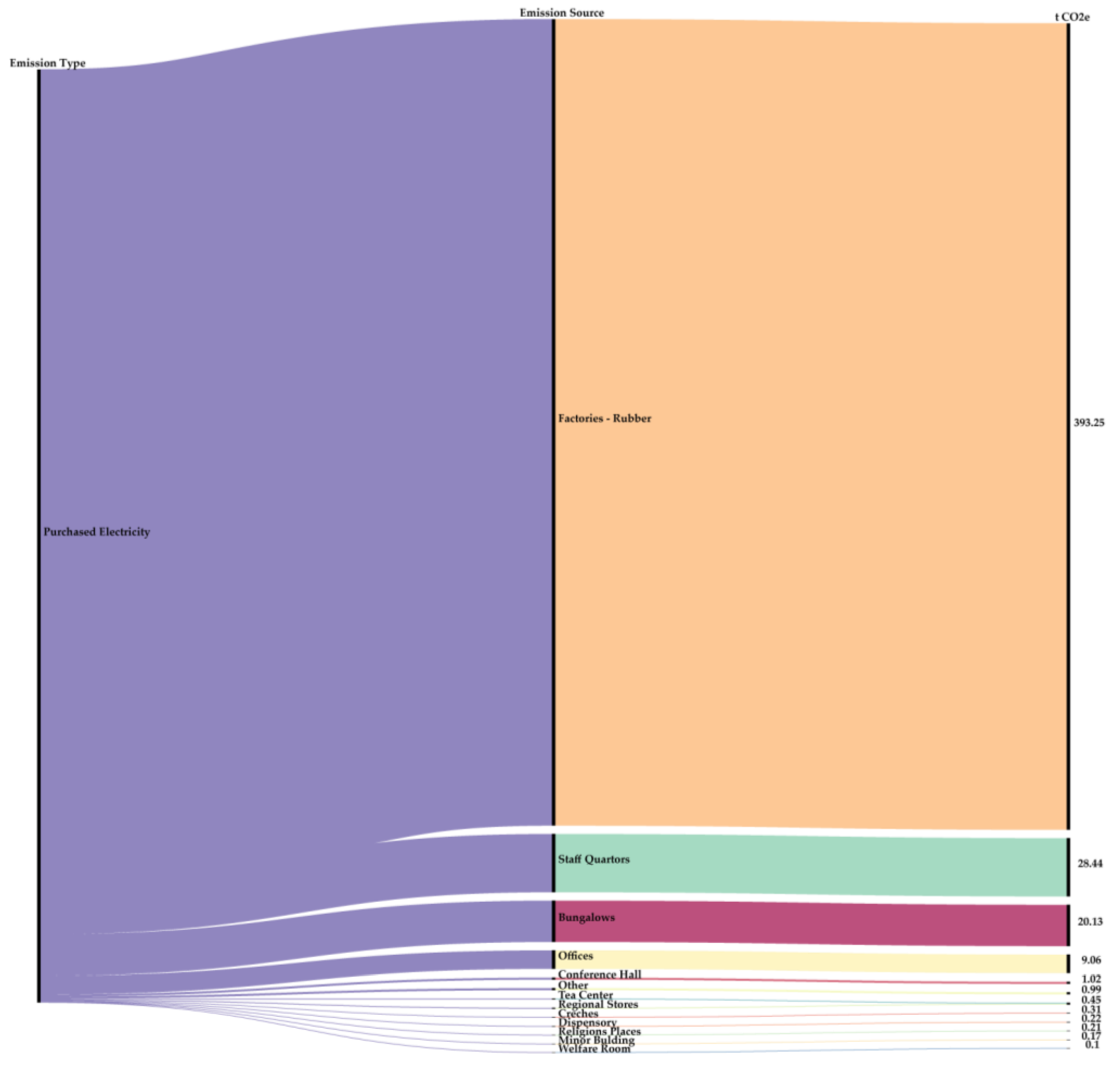

3.1.2. Scope 2 Emissions

3.1.3. Scope 3 Emissions

3.2. Carbon Fixation

3.3. Proposal of Improvement Options

3.3.1. Option 1: Reduction in Fertilization

3.3.2. Option 2: Installation of Solar Panels and Implementation of Energy Efficiency Practices

3.3.3. Option 3: Use of Fenton Reagent and Activated Carbon for Wastewater Treatment

3.4. Evaluation of Potential Improvements

3.4.1. Option 1: Reduction in Fertilization

3.4.2. Option 2: Installation of Solar Panels and Implementation of Energy Efficiency Practices

3.4.3. Option 3: Use of Fenton Reagent and Activated Carbon for Wastewater Treatment

3.4.4. Combined Scenario: Application of Options 1, 2, and 3

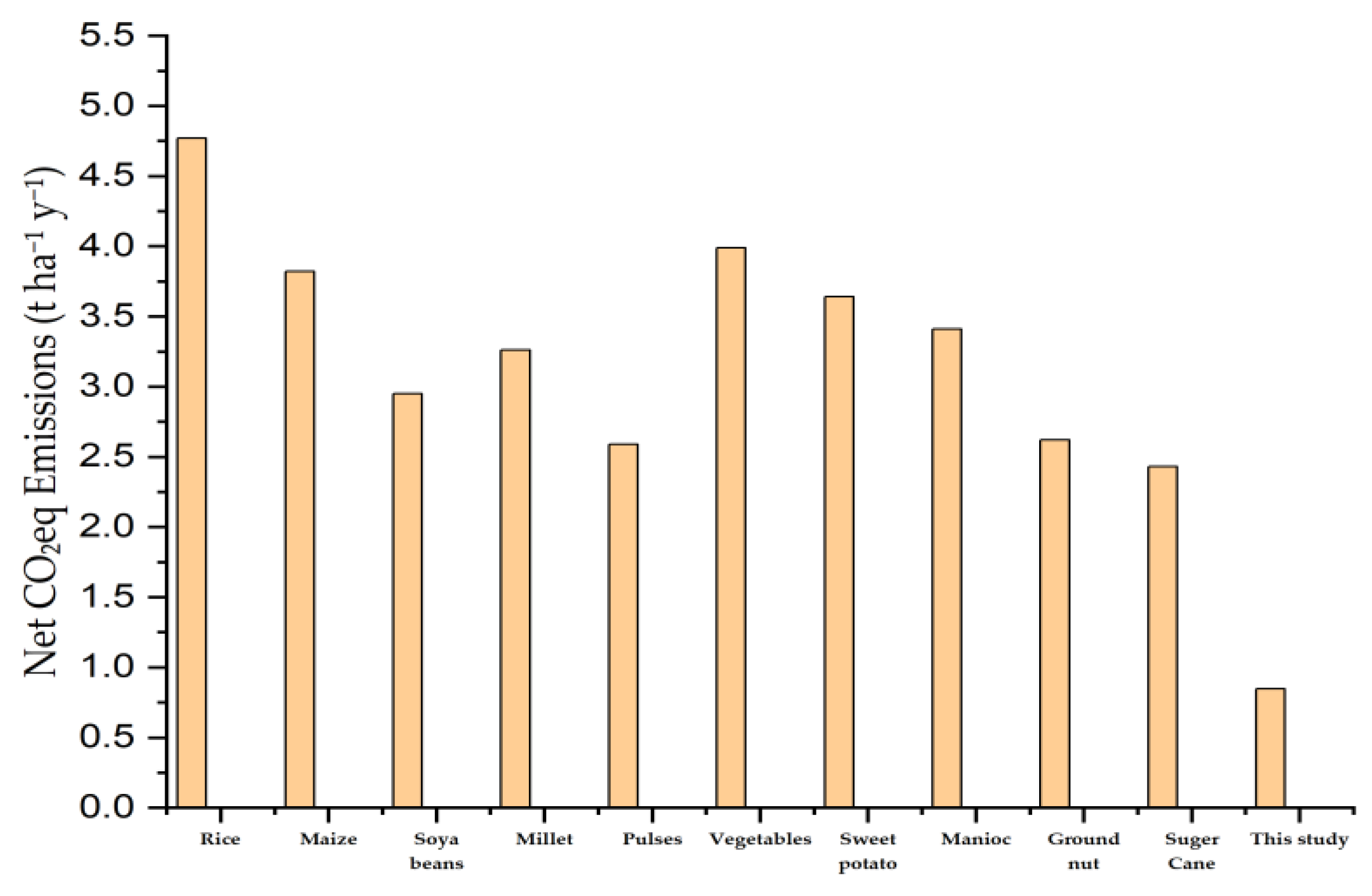

3.5. Comparative Analysis of Carbon Footprint with Other Studies

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gunathilaka, L.F.D.Z. The Impact of Green House Gas Emission on Corporate Climate Policies in Apparel Sector Organizations in Sri Lanka. Master of Science, University of Sri Jayewardenepura: Nugegoda, 2013.

- Ur Rahman, S.; Chwialkowska, A.; Hussain, N.; Bhatti, W.A.; Luomala, H. Cross-Cultural Perspective on Sustainable Consumption: Implications for Consumer Motivations and Promotion. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2023, 25, 997–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shivanna, K.R. Climate Change and Its Impact on Biodiversity and Human Welfare. Proc. Indian Natl. Sci. Acad. 2022, 88, 160–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bataleblu, A.A.; Rauch, E.; Cochran, D.S. Resilient Sustainability Assessment Framework from a Transdisciplinary System-of-Systems Perspective. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wassmann, R.; Van-Hung, N.; Yen, B.T.; Gummert, M.; Nelson, K.M.; Gheewala, S.H.; Sander, B.O. Carbon Footprint Calculator Customized for Rice Products: Concept and Characterization of Rice Value Chains in Southeast Asia. Sustainability 2021, 14, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adu Sarfo, P.; Zhang, J.; Nyantakyi, G.; Lassey, F.A.; Bruce, E.; Amankwah, O. Influence of Green Human Resource Management on Firm’s Environmental Performance: Green Employee Empowerment as a Mediating Factor. PLOS ONE 2024, 19, e0293957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čuček, L.; Klemeš, J.J.; Kravanja, Z. Overview of Environmental Footprints. In Assessing and Measuring Environmental Impact and Sustainability; Elsevier, 2015; pp. 131–193. ISBN 978-0-12-799968-5.

- Mahapatra, S.K.; Schoenherr, T.; Jayaram, J. An Assessment of Factors Contributing to Firms’ Carbon Footprint Reduction Efforts. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2021, 235, 108073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandola, D.M.; Asdrubali, F. A Methodology to Evaluate GHG Emissions for Large Sports Events. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waddell, C.J.; Hurteau, M.D.; Huntzinger, D. Product Carbon Footprinting: A Proposed Framework to Increase Confidence, Reduce Costs and Incorporate Profit Incentive. Carbon Manag. 2011, 2, 645–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groening, C.; Inman, J.J.; Ross, W.T. Carbon Footprints in the Sand: Marketing in the Age of Sustainability. Cust. Needs Solut. 2014, 1, 40–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, G.; Svanström, M.; Roos, S.; Sandin, G.; Zamani, B. Carbon Footprints in the Textile Industry. In Handbook of Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) of Textiles and Clothing; Elsevier, 2015; pp. 3–30. ISBN 978-0-08-100169-1.

- Green, J.F. Private Standards in the Climate Regime: The Greenhouse Gas Protocol. Bus. Polit. 2010, 12, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downie, J.; Stubbs, W. Corporate Carbon Strategies and Greenhouse Gas Emission Assessments: The Implications of Scope 3 Emission Factor Selection. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2012, 21, 412–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, S.; Rubio, A. Carbon Footprint in Green Public Procurement: A Case Study in the Services Sector. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 93, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, H.S.; Hendrickson, C.T.; Weber, C.L. The Importance of Carbon Footprint Estimation Boundaries. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2008, 42, 5839–5842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Central Bank of Sri Lanka Press Release External Sector Performance – December 2023 2024.

- Guinee, J.B. Handbook on Life Cycle Assessment Operational Guide to the ISO Standards. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2002, 7, 311–BF02978897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthukumarana, T.T.; Karunathilake, H.P.; Punchihewa, H.K.G.; Manthilake, M.M.I.D.; Hewage, K.N. Life Cycle Environmental Impacts of the Apparel Industry in Sri Lanka: Analysis of the Energy Sources. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 172, 1346–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhowmik, I. Impact of Rubber Plantations on the Environment of Tripura. SSRN Electron. J. 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.-J.; Ji, H.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, Y.-P.; Sha, L.-Q.; Liu, Y.-T.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, W.; Dong, Y.; Bai, X.-L.; et al. The Effects of Nitrogen Fertilization on N2O Emissions from a Rubber Plantation. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 28230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumara, P.R.; Munasinghe, E.S.; Rodrigo, V.H.L.; Karunaratna, A.S. Carbon Footprint of Rubber/Sugarcane Intercropping System in Sri Lanka: A Case Study. Procedia Food Sci. 2016, 6, 298–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunuwila, P.; Rodrigo, V.H.L.; Goto, N. Financial and Environmental Sustainability in Manufacturing of Crepe Rubber in Terms of Material Flow Analysis, Material Flow Cost Accounting and Life Cycle Assessment. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 182, 587–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunuwila, P.; Rodrigo, V.H.L.; Goto, N. Sustainability of Natural Rubber Processing Can Be Improved: A Case Study with Crepe Rubber Manufacturing in Sri Lanka. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 133, 417–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidanagama, J.; Lokupitiya, E. Energy Usage and Greenhouse Gas Emissions Associated with Tea and Rubber Manufacturing Processes in Sri Lanka. Environ. Dev. 2018, 26, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cucci, G.; Valentini, F.; Dorigato, A. Cradle to Gate Life Cycle Assessment of Tyre-Grade Natural Rubber Produced in Thailand. Sci. Total Environ. 2025, 987, 179653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Susilawati, H.L.; Setyanto, P. Opportunities to Mitigate Greenhouse Gas Emission from Paddy Rice Fields in Indonesia. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2018, 200, 012027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusoff, S.; Mohamed, Z.; Zuriani Ahmad, A. Environmental Impact Evaluation of Rubber Cultivation and Industry in Malaysia. In Climate Change and Agriculture; Hussain, S., Ed.; IntechOpen, 2019. ISBN 978-1-78985-667-5.

- Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs, D. for E.S. and N.Z. Greenhouse Gas Reporting: Conversion Factors 2023 2023.

- 2006 IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories; Eggleston, H.S., Ed.; Institute for Global Environmental Strategies: Hayama, Japan, 2006; ISBN 978-4-88788-032-0. [Google Scholar]

- The Greenhouse Gas Protocol: A Corporate Accounting and Reporting Standard; Smith, B., World Business Council for Sustainable Development, World Resources Institute, Eds.; revised ed; World Resources Institute and World Business Council for Sustainable Development: o.O, 2004; ISBN 978-1-56973-568-8. [Google Scholar]

- Ceylon Electricity Board CEB Statistical Digest Report 2021 2021.

- Sri Lanka Sustainable Energy Authority Sri Lanka Energy Balance 2021.

- India GHG Program India Specic Road Transport Emission Factors.

- Munasinghe, E.S.; Rodrigo, V.H.L.; Gunawardena, U.A.D.P. MODUS OPERANDI IN ASSESSING BIOMASS AND CARBON IN RUBBER PLANTATIONS UNDER VARYING CLIMATIC CONDITIONS. Exp. Agric. 2014, 50, 40–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chompu-inwai, R.; Jaimjit, B.; Premsuriyanunt, P. A Combination of Material Flow Cost Accounting and Design of Experiments Techniques in an SME: The Case of a Wood Products Manufacturing Company in Northern Thailand. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 108, 1352–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jawjit, W.; Pavasant, P.; Kroeze, C.; Tuffrey, J. Evaluation of the Potential Environmental Impacts of Condom Production in Thailand. J. Integr. Environ. Sci. 2021, 18, 89–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunuwila, P.; Rodrigo, V.H.L.; Goto, N. Improving Financial and Environmental Sustainability in Concentrated Latex Manufacture. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 255, 120202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Industrial Work, Ministry of Industry. Industrial Sector Codes of Practice for Pollution PREVENTION (Cleaner Technology) - Concentrated Latex and Blocked Rubber (STR 20) 2001.

- Emilia Agustina, T.; Jefri Sirait, E.; Silalahi, H. TREATMENT OF RUBBER INDUSTRY WASTEWATER BY USING FENTON REAGENT AND ACTIVATED CARBON. J. Teknol. 2017, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Central Environmental Authority Waste_Water_Discharge_standards.

- Cabot, M.I.; Lado, J.; Bautista, I.; Ribal, J.; Sanjuán, N. On the Relevance of Site Specificity and Temporal Variability in Agricultural LCA: A Case Study on Mandarin in North Uruguay. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2023, 28, 1516–1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iriarte, A.; Yáñez, P.; Villalobos, P.; Huenchuleo, C.; Rebolledo-Leiva, R. Carbon Footprint of Southern Hemisphere Fruit Exported to Europe: The Case of Chilean Apple to the UK. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 293, 126118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathnayake, H.; Mizunoya, T. A Study on GHG Emission Assessment in Agricultural Areas in Sri Lanka: The Case of Mahaweli H Agricultural Region. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 88180–88196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ms, S.; Pn, K.; G, N.; H, S. The Role of Agricultural Engineering in Enhanced Food Security. Int. J. Res. Agron. 2024, 7, 691–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogwu, M.C.; Kosoe, E.A. Integrating Green Infrastructure into Sustainable Agriculture to Enhance Soil Health, Biodiversity, and Microclimate Resilience. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, K.; Chugan, P.K. Green HRM in Pursuit of Environmentally Sustainable Business. Univers. J. Ind. Bus. Manag. 2015, 3, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghuwanshi, S.; Acharya, Dr.S. GREEN HRM–STRATEGIES FOR GREENING PEOPLE. Int. J. Tech. Res. Sci. 2020, 5, 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, B.B.; Afsar, B.; Hafeez, S.; Khan, I.; Tahir, M.; Afridi, M.A. Promoting Employee’s Proenvironmental Behavior through Green Human Resource Management Practices. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 26, 424–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Emission type | Activity | Data | Unit | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scope 1 | Use of the diesel generator | 13,804 | L | Running chart |

| Use of the petrol generator | 645 | L | Running chart | |

| Use of the LPG gases | 10 | tonnes | Running chart | |

| Use of petrol equipment’s and machines | 4,983 | L | Running chart | |

| Use of fugitive emissions - fire extinguishers | 120 | kg | Running chart | |

| Use of factory owned diesel vehicles | 118,621 | L | Running chart | |

| Use of factory owned petrol motor bike | 7,093 | L | Running chart | |

| Discharge of waste water | 75,479,359 | L | Running chart | |

| Scope 2 | Purchased electricity | 1,063,145 | kWh | Electricity bills |

| Scope 3 | Consumption of weedicide | 4,527 | kg | Running chart |

| Consumption of fungicide | 1,446 | kg | Running chart | |

| Consumption of fertilizer | 468,107 | kg | Running chart | |

| employee commuting use of staff own vehicles | 26,905 | L | Questionnaire | |

| Employee commuting use of public transport | 218,405 | km | Questionnaire | |

| Hired vehicles | 42,736 | L | Invoices | |

| Air travel | 2 | Number of travels | Invoices | |

| Waste transportation | 967 | km | Questionnaire | |

| Solid waste generation | 43 | tonnes | Invoices | |

| Chemical use | 141,117 | kg | Running chart |

| Emission source | Amount of consumption | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| On site energy | ||

| Stand by generator - diesel | 13804.00 | L |

| Stand by generator - petrol | 645.00 | L |

| Water pump - diesel | 35.00 | L |

| LPG gases | 9.74 | tonnes |

| Grass cutter - petrol | 2574 | L |

| Chain saw - petrol | 2022.75 | L |

| Mix blower- petrol | 4.00 | L |

| Power sprayer - petrol | 10.00 | L |

| Staff / tappel - petrol | 137.50 | L |

| Mist blower - petrol | 28.00 | L |

| Weeding machines - petrol | 155.50 | L |

| Water pump - petrol | 16.00 | L |

| Fugitive emissions | ||

| Fire extinguishers | 120.00 | kg |

| Company owned vehicles | ||

| Ambulance - diesel | 2751.40 | L |

| Lorry - diesel | 26112.00 | L |

| Cab - diesel | 28291.57 | L |

| Tractor - diesel | 56037.00 | L |

| Motor bike - petrol | 7092.82 | L |

| Jeep - diesel | 1286.00 | L |

| Van - diesel | 3400.40 | L |

| Bachoe - diesel | 743.00 | L |

| Wastewater treatment | ||

| CH4 | 38462.61 | kg |

| Emission Source | Amount of consumption | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| Purchased electricity | ||

| Bungalows | 47050 | kWh |

| Staff quarters | 66489 | kWh |

| Offices | 21179 | kWh |

| Religions places | 495 | kWh |

| Factories - rubber | 919243 | kWh |

| Creches | 719 | kWh |

| Conference hall | 2389 | kWh |

| Tea center | 1059 | kWh |

| Dispensary | 512 | kWh |

| Other | 2319 | kWh |

| Welfare room | 223 | kWh |

| Regional stores | 1063 | kWh |

| Minor building | 404 | kWh |

| Emission Source | Amount of consumption | Unit | Emissions of carbon dioxide tCO₂e |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electricity - transmission & distribution losses | |||

| Bungalows | 4539.91 | kWh | 1.94 |

| Staff quartos | 6415.61 | kWh | 2.75 |

| Offices | 2043.64 | kWh | 0.87 |

| Religions places | 47.76 | kWh | 0.02 |

| Factories - rubber | 88698.89 | kWh | 37.95 |

| Creches | 69.38 | kWh | 0.03 |

| Conference hall | 230.52 | kWh | 0.10 |

| Tea center shop | 102.23 | kWh | 0.04 |

| Dispensary | 49.40 | kWh | 0.02 |

| Other | 223.76 | kWh | 0.10 |

| Welfare room | 21.52 | kWh | 0.01 |

| Regional stores | 102.57 | kWh | 0.04 |

| Minor building | 38.98 | kWh | 0.02 |

| Electricity - transmission & distribution losses | 102584.17 | kWh | 43.89 |

| Weedicide use | 4526.70 | kg | 44.32 |

| Fungicide use | 1446.00 | kg | 15.31 |

| Fertilizer use | 468106.50 | kg | 780.41 |

| Staff own vehicle transport | |||

| Motor cycle petrol | 24952.30 | L | 58.51 |

| Three wheel - petrol | 1953.00 | L | 4.58 |

| Public transport | |||

| Bus-diesel | 213287.20 | km | 3.23 |

| Three-wheeler-petrol | 5118.00 | km | 0.58 |

| Hired vehicles | |||

| Bowser-diesel | 33211.00 | L | 88.32 |

| Backho machines - diesel | 1985.00 | L | 5.28 |

| Drone machines -diesel | 20.00 | L | 0.05 |

| Tractor- diesel | 1278.00 | L | 3.40 |

| Lorry -diesel | 6207.50 | L | 16.51 |

| Three wheel-petrol | 34.00 | L | 0.08 |

| Air travel | 2.00 | travel | 0.88 |

| Waste transportation | 966.70 | km | 0.57 |

| Solid waste generation by waste recycled (rain guard polytene) waste |

42.59 | tonnes | 0.91 |

| Chemical use | 141117.12 | kg | 116.14 |

| Emission Type/source | Emissions of carbon dioxide tCO₂e |

% of total | Cumulative percentage [%] |

|---|---|---|---|

| CH4 | 1077 | 34.5 | 34.5 |

| Fertilizer | 780 | 25.0 | 59.4 |

| Purchased electricity | 455 | 14.6 | 74.0 |

| Owned vehicles transport | 331 | 10.6 | 84.6 |

| Chemical use | 116 | 3.7 | 88.3 |

| Hired vehicles | 114 | 3.6 | 92.0 |

| On site energy | 78 | 2.5 | 94.5 |

| Employee commuting | 67 | 2.1 | 96.6 |

| Weedicide | 44 | 1.4 | 98.0 |

| Electricity transmission & distribution losses | 44 | 1.4 | 99.4 |

| Fungicide | 15 | 0.5 | 99.9 |

| Waste | 1 | 0.0 | 99.9 |

| Air Travel | 1 | 0.0 | 100.0 |

| Total | 3125 | 100 | 100.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).