Submitted:

28 August 2025

Posted:

29 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Microalgae Species and Growth Conditions

2.2. Total Lipid Content and Fatty Acid Analysis

2.3. D. melanogaster Assay

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Total Lipid and Fatty Acid Profile

3.2. Effect of Microalgae-Treated Food on D. melanogaster Physiological Parameters

3.2.1. Lifespan

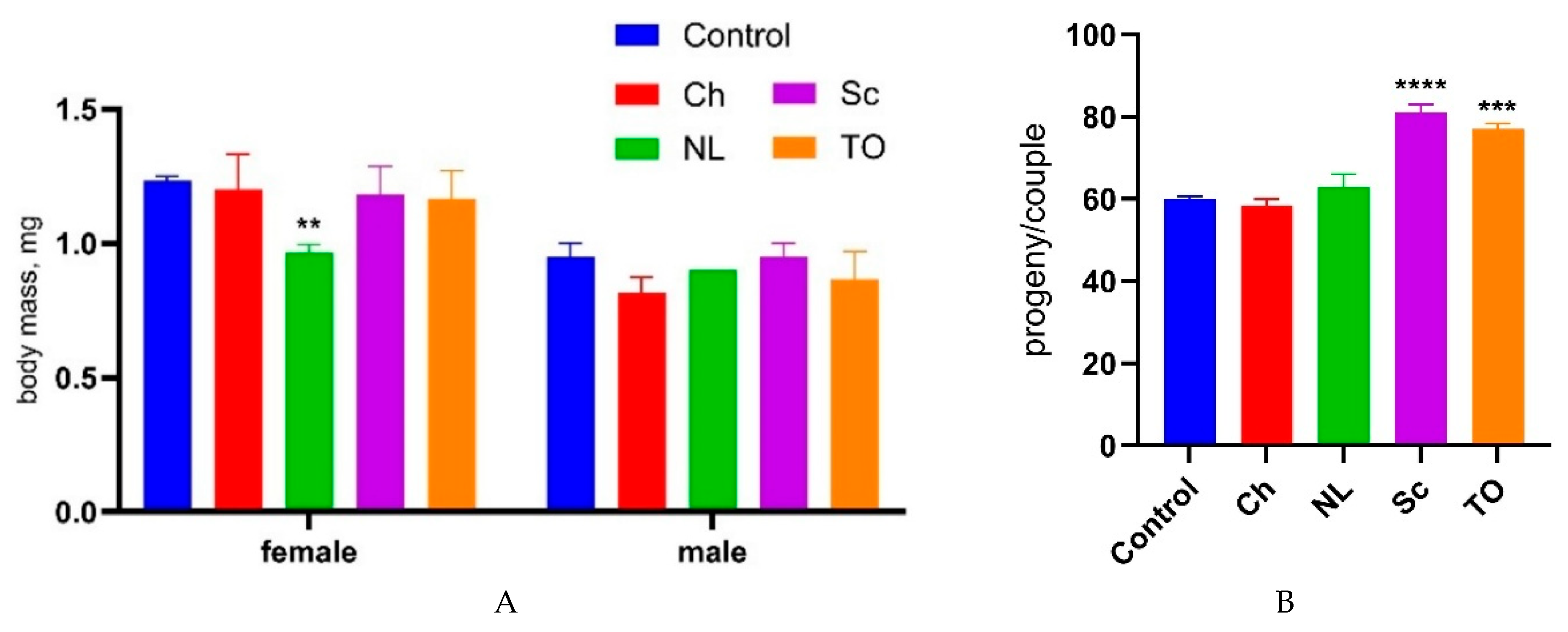

3.2.2. Body Mass and Fertility

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Krienitz, L.; Wirth, M. The High Content of Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids in Nannochloropsis Limnetica (Eustigmatophyceae) and Its Implication for Food Web Interactions, Freshwater Aquaculture and Biotechnology. Limnologica 2006, 36, 204–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira De Oliveira, A.P.; Bragotto, A.P.A. Microalgae-Based Products: Food and Public Health. Future Foods 2022, 6, 100157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, M.; Aflalo, C.; Bernard, O. Microalgal Lipids: A Review of Lipids Potential and Quantification for 95 Phytoplankton Species. Biomass and Bioenergy 2021, 150, 106108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shivakumar, S.; Serlini, N.; Esteves, S.M.; Miros, S.; Halim, R. Cell Walls of Lipid-Rich Microalgae: A Comprehensive Review on Characterisation, Ultrastructure, and Enzymatic Disruption. Fermentation 2024, 10, 608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slocombe, S.P.; Zhang, Q.; Ross, M.; Anderson, A.; Thomas, N.J.; Lapresa, Á.; Rad-Menéndez, C.; Campbell, C.N.; Black, K.D.; Stanley, M.S.; et al. Unlocking Nature’s Treasure-Chest: Screening for Oleaginous Algae. Sci Rep 2015, 5, 9844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staats, S.; Lüersen, K.; Wagner, A.E.; Rimbach, G. Drosophila Melanogaster as a Versatile Model Organism in Food and Nutrition Research. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2018, 66, 3737–3753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musselman, L.P.; Kühnlein, R.P. Drosophila as a Model to Study Obesity and Metabolic Disease. Journal of Experimental Biology 2018, 221, jeb163881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, S.; Shen, Y.; Zhang, L.; Ma, B.; Amadu, A.A.; Ge, S. Antioxidant Assessment of Wastewater-Cultivated Chlorella Sorokiniana in Drosophila Melanogaster. Algal Research 2020, 46, 101795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, S.; Wang, S.; Xiao, C.; Ge, S. Assessment of Microalgae as a New Feeding Additive for Fruit Fly Drosophila Melanogaster. Science of The Total Environment 2019, 667, 455–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harry W., Bischoff; Harold, C. Bold Phycological Studies IV. Some Soil Algae from Enchanted Rock and Related Algal Species; Department of Biology, Texas Lutheran College, Seguin, Texas.; 1963; Vol. No. 6318.

- Halim, R.; Papachristou, I.; Kubisch, C.; Nazarova, N.; Wüstner, R.; Steinbach, D.; Chen, G.Q.; Deng, H.; Frey, W.; Posten, C.; et al. Hypotonic Osmotic Shock Treatment to Enhance Lipid and Protein Recoveries from Concentrated Saltwater Nannochloropsis Slurries. Fuel 2021, 287, 119442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiani, H.; Ma, Q.; Xiao, M.; Li, Y.; Brooke, F.J.; Mulcahy, S.; Miros, S.; Halim, R. Growth and Fatty Acid Profile of Nannochloropsis Oceanica Cultivated on Nano-Filtered Whey Permeate. J Appl Phycol 2024, 36, 2503–2516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liubertas, T.; Poderys, J.; Vilma, Z.; Capkauskiene, S.; Viskelis, P. Impact of Dietary Potassium Nitrate on the Life Span of Drosophila Melanogaster. Processes 2021, 9, 1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freire, I.; Cortina-Burgueño, A.; Grille, P.; Arizcun Arizcun, M.; Abellán, E.; Segura, M.; Witt Sousa, F.; Otero, A. Nannochloropsis Limnetica: A Freshwater Microalga for Marine Aquaculture. Aquaculture 2016, 459, 124–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, B.K.; Garcia-Vaquero, M. Nutraceuticals from Algae: Current View and Prospects from a Research Perspective. Marine Drugs 2022, 20, 671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arora, N.; Philippidis, G.P. Insights into the Physiology of Chlorella Vulgaris Cultivated in Sweet Sorghum Bagasse Hydrolysate for Sustainable Algal Biomass and Lipid Production. Sci Rep 2021, 11, 6779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeh, K.; Chang, J. Nitrogen Starvation Strategies and Photobioreactor Design for Enhancing Lipid Content and Lipid Production of a Newly Isolated Microalga Chlorella Vulgaris ESP-31: Implications for Biofuels. Biotechnology Journal 2011, 6, 1358–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, T.; Chen, Z.; Xiao, Y.; Yuan, M.; Zhou, C.; Liu, G.; Fang, J.; Yang, B. Biochemical and Morphological Changes Triggered by Nitrogen Stress in the Oleaginous Microalga Chlorella Vulgaris. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimi, M.; Webley, P.A.; Martin, G.J.O.; Halim, R. Nitrogen Starvation for Fuel Production from Nannochloropsis: A Trade-off between Calorific Lipid Accumulation and Energy Loss for Cell Disruption. Chemical Engineering Journal Advances 2025, 23, 100812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freire, I.; Cortina-Burgueño, A.; Grille, P.; Arizcun Arizcun, M.; Abellán, E.; Segura, M.; Witt Sousa, F.; Otero, A. Nannochloropsis Limnetica: A Freshwater Microalga for Marine Aquaculture. Aquaculture 2016, 459, 124–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fardous Ara Mukta; Helena Khatoon; Mohammad Redwanur Rahman; Mahima RanjanAcharjee; Subeda Newase; Zannatul Nayma; Razia Sultana; Shanur Jahedul Hasan Effect of Different Nitrogen Concentrationson the Growth, Proximate and Biochemical Composition of Freshwater Microalgae Scenedesmus Communis. Journal of Energy and Environmental Sustainability 11 & 12, 36–42.

- Shen, P.-L.; Wang, H.-T.; Pan, Y.-F.; Meng, Y.-Y.; Wu, P.-C.; Xue, S. Identification of Characteristic Fatty Acids to Quantify Triacylglycerols in Microalgae. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breuer, G.; Lamers, P.P.; Martens, D.E.; Draaisma, R.B.; Wijffels, R.H. Effect of Light Intensity, pH, and Temperature on Triacylglycerol (TAG) Accumulation Induced by Nitrogen Starvation in Scenedesmus Obliquus. Bioresource Technology 2013, 143, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farag, M.A.; Gad, M.Z. Omega-9 Fatty Acids: Potential Roles in Inflammation and Cancer Management. Journal of Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology 2022, 20, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M. Omega-3, Omega-6 and Omega-9 Fatty Acids: Implications for Cardiovascular and Other Diseases. J Glycomics Lipidomics 2014, 04. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venn-Watson, S.; Schork, N.J. Pentadecanoic Acid (C15:0), an Essential Fatty Acid, Shares Clinically Relevant Cell-Based Activities with Leading Longevity-Enhancing Compounds. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emmanuel, B. The Relative Contribution of Propionate, and Long-Chain Even-Numbered Fatty Acids to the Production of Long-Chain Odd-Numbered Fatty Acids in Rumen Bacteria. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Lipids and Lipid Metabolism 1978, 528, 239–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lints, F.A.; Bourgois, M.; Delalieux, A.; Stoll, J.; Lints, C.V. Does the Female Life Span Exceed That of the Male. Gerontology 1983, 29, 336–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Component, % DW | C. vulgaris | N. limnetica | S. communis | T. obliquus |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Lipids | 26.7 ± 2.8A | 27.2 ± 0.9A | 16.6 ± 3.0B | 22.6 ± 0.9AB |

| Total Fatty Acids | 8.0 ± 0.9A | 7.7 ± 0.7AB | 2.9 ± 0.8BC | 3.7 ± 1.6C |

| Fatty acids, (% TFA) | ||||

| Saturated | ||||

| C14:0 | – | 1.6 ± 0.1 | – | – |

| C15:0 | 16.2 ± 7.6 | 15.9 ± 5.8 | 41.7 ±13.0 | 38.4 ± 12.1 |

| C16:0 | 17 ± 1.5 | 14.9 ±1.4 | 13.8 ± 6.3 | 11.9 ± 2.1 |

| C18:0 | 4.1 ± 0.2 | 2.9 ± 0.1 | – | – |

| Monounsaturated | ||||

| C16:1 | 5.4 ± 0.3 | 3.9 ± 0.2 | – | – |

| C18:1n9 Omega-9 | 46.0 ± 0.6 | 43.7 ± 1.2 | 28.9 ± 4.1 | 41.0 ± 0.6 |

| C18:2n6 Omega-6 | 15.9 ± 0.4 | 21.2 ± 0.2 | 15.5 ± 2.7 | 17.3 ± 2.8 |

| Variant | Females | Males | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Survival Days | Median lifespan change (% vs. control) |

Survival Days | Median lifespan change (% vs. control) |

|||||

| Median | Mean | Max | Median | Mean | Max | |||

| Control | 18.5 | 17,2 | 35 | 0A | 12 | 13.8 | 30 | 0A |

| C. vulgaris | 27.0 | 24.5 | 41 | +45.9B | 21 | 18.9 | 32 | +75.0B |

| N. limnetica | 18.5 | 18.9 | 32 | 0.0A | 15 | 15.3 | 30 | +25.0B |

| S. communis | 20.0 | 20.0 | 36 | +8.1B | 15.5 | 15.0 | 29 | +29.2B |

| T. obliquus | 23.5 | 24.1 | 44 | +27.0B | 18 | 16.8 | 31 | +50.0B |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).