Submitted:

27 August 2025

Posted:

28 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

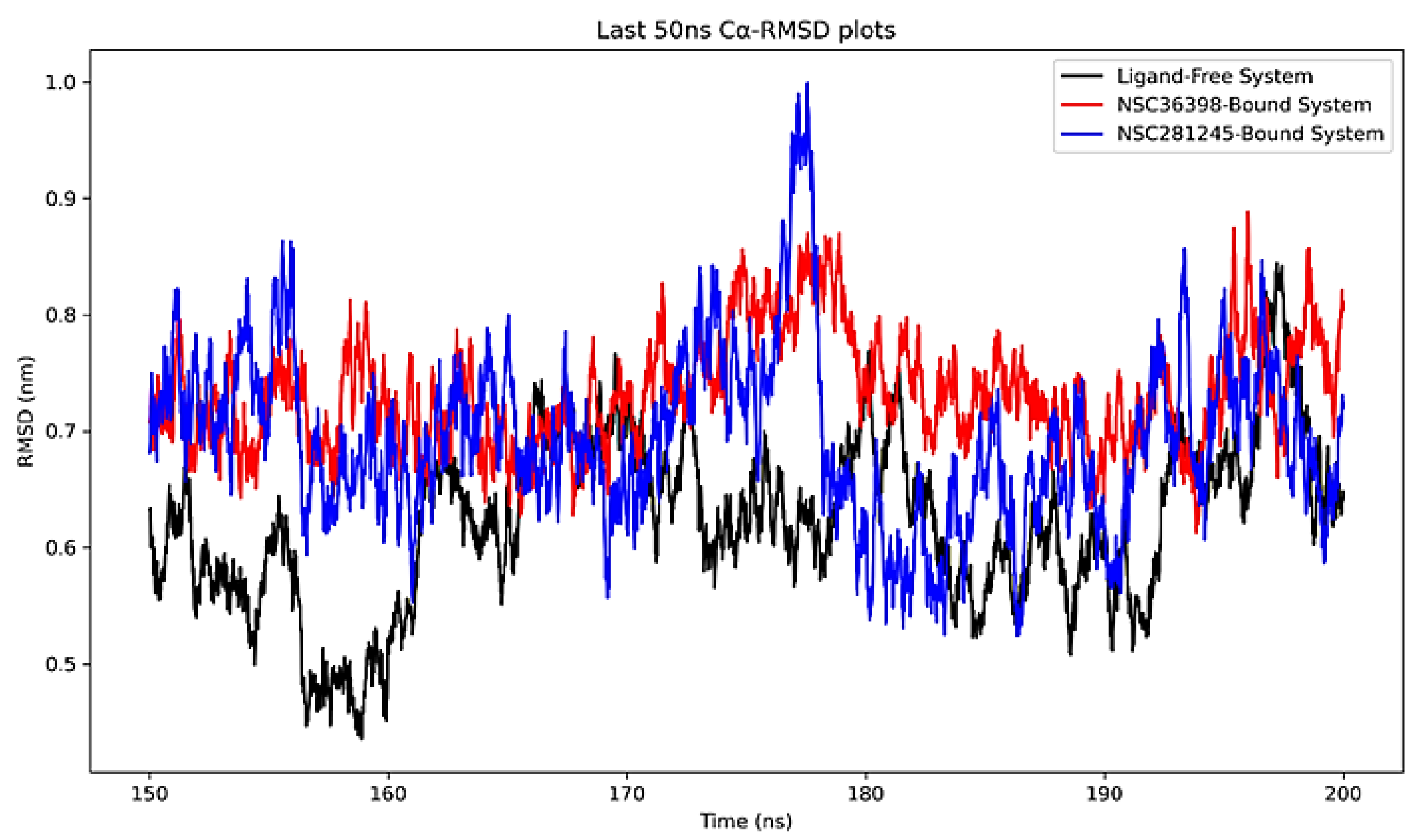

2.1. Initial Post-MD Analysis: KDE and C-alpha RMSD Analysis

2.2. Structural Analysis

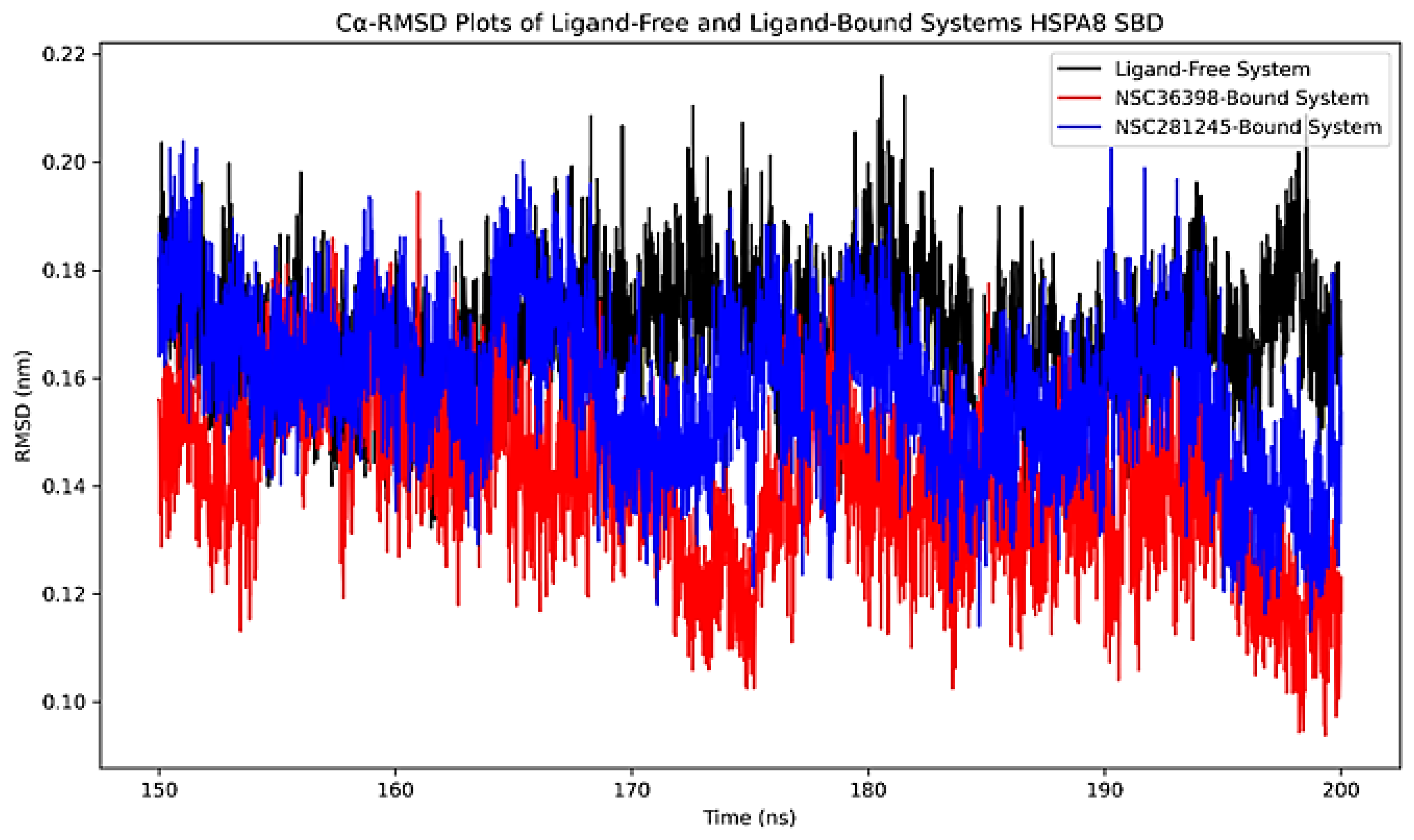

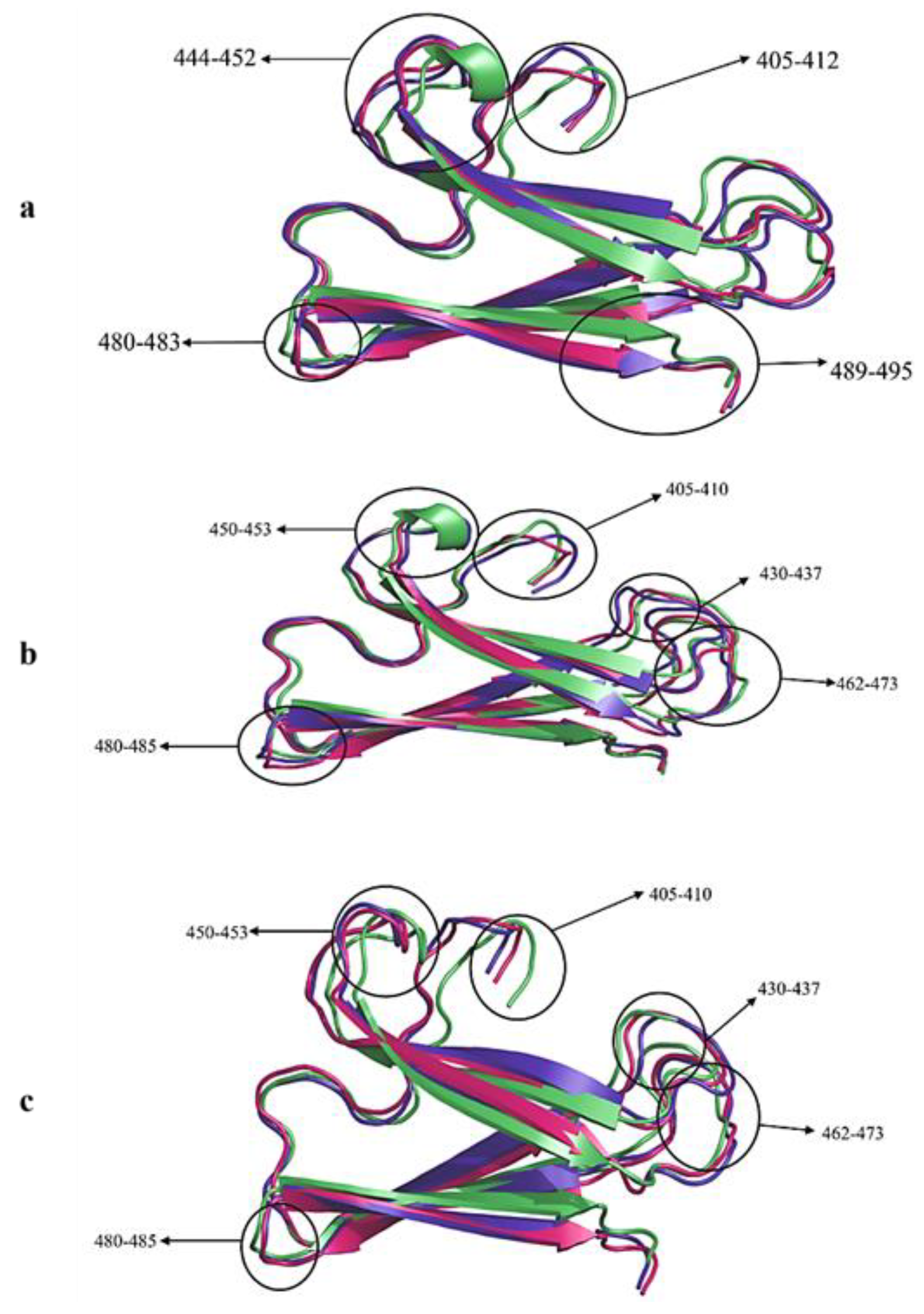

2.2.1. Cα-RMSD Analysis of Functional Domains: HSPA8 SBD

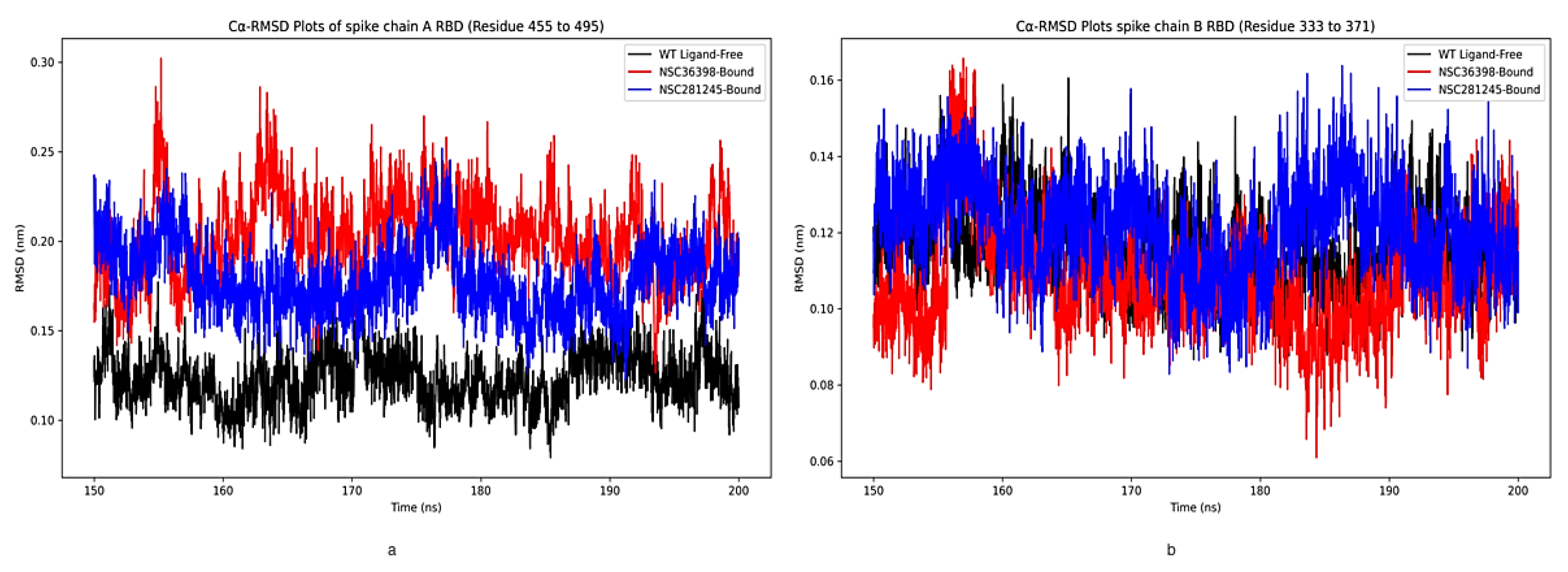

2.2.2. Cα-RMSD Analysis of Functional Domains: Spike Chain A and B RBD

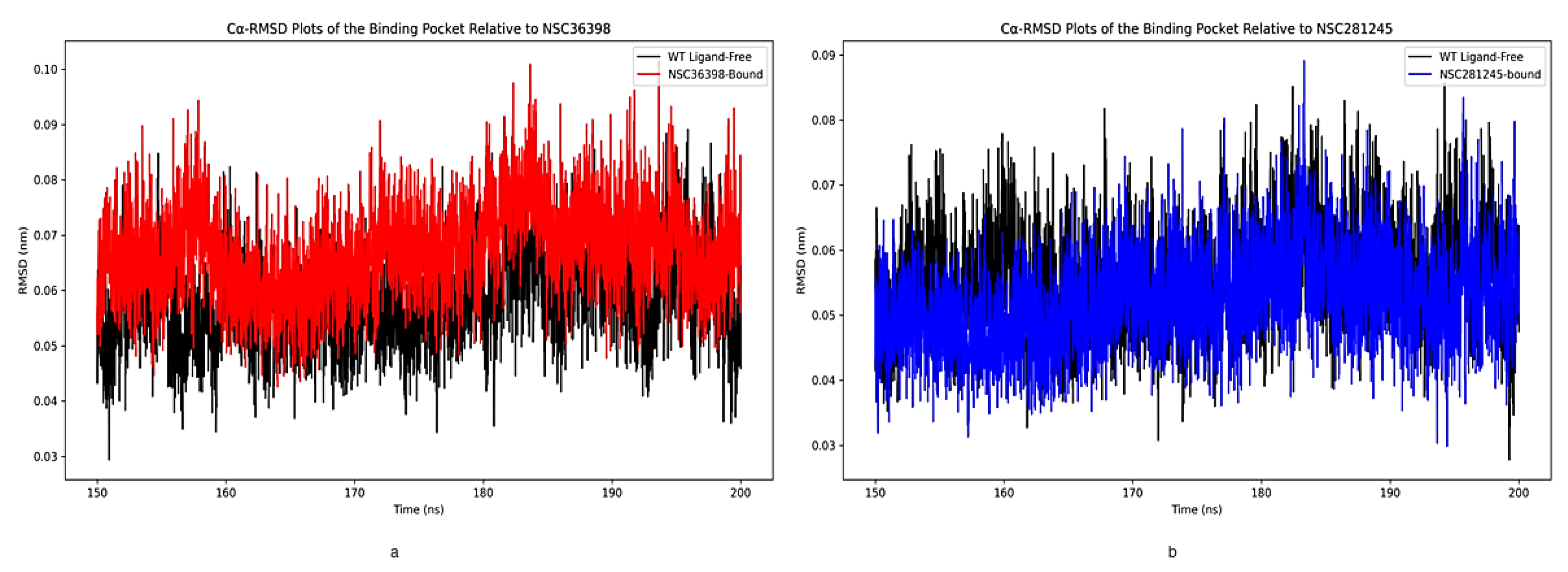

2.2.3. Cα-RMSD Analysis of Functional Domains: Binding Pocket Relative to NSC36398 and NSC281245

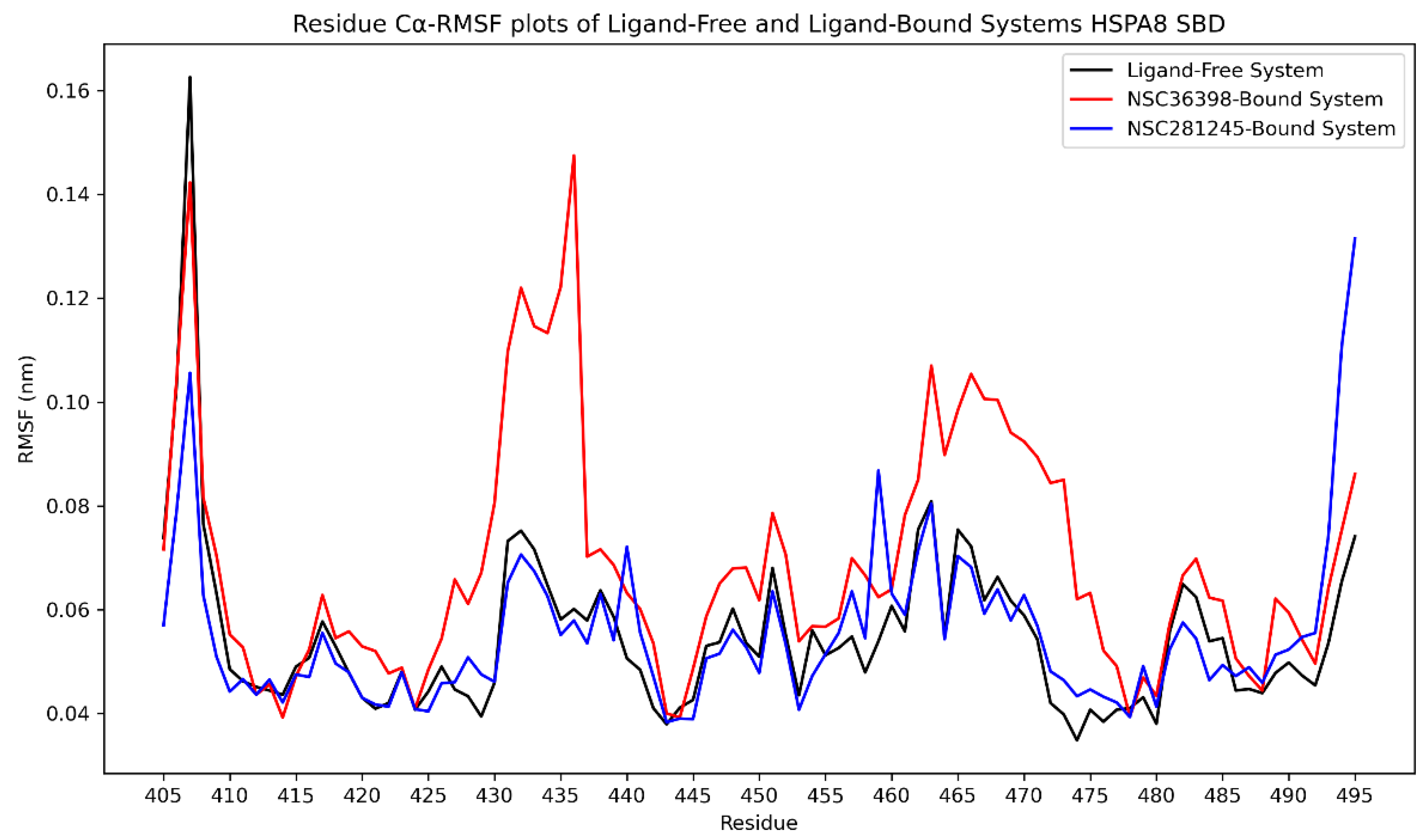

2.2.4. Cα-RMSF Analysis of Functional Domains: HSPA8 SBD

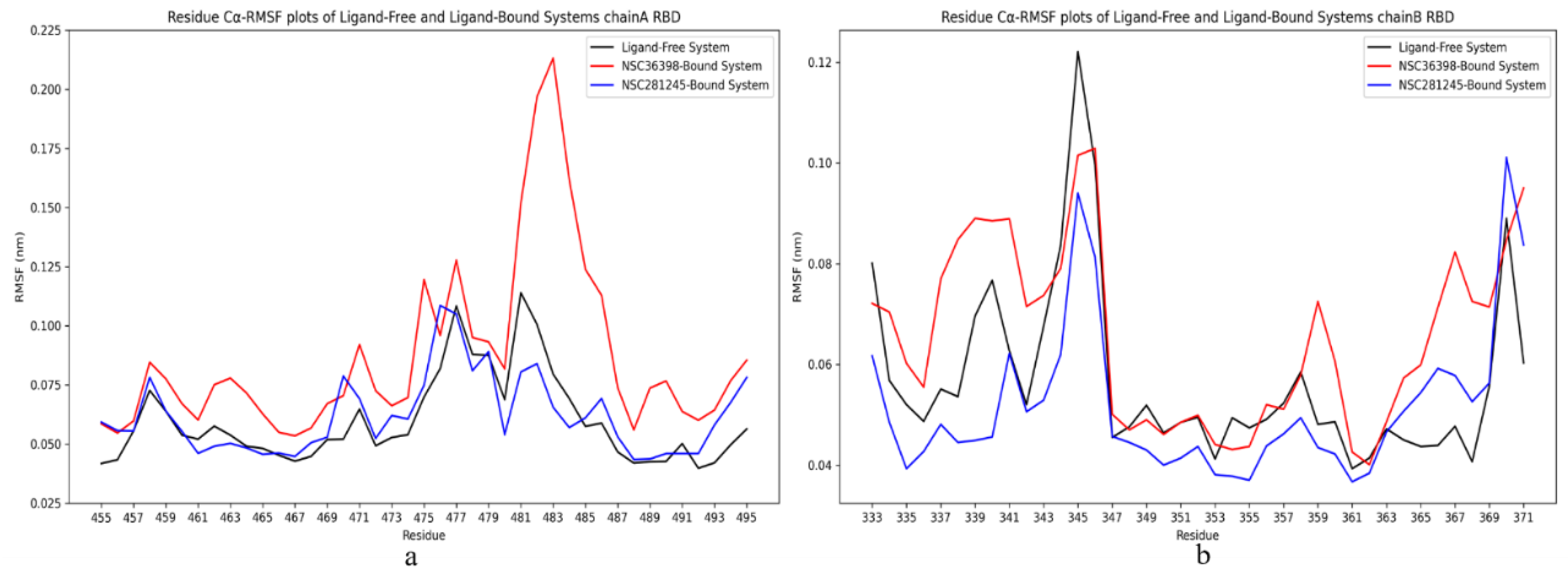

2.2.5. Cα-RMSF Analysis of Functional Domains: Spike Chain A and B RBD

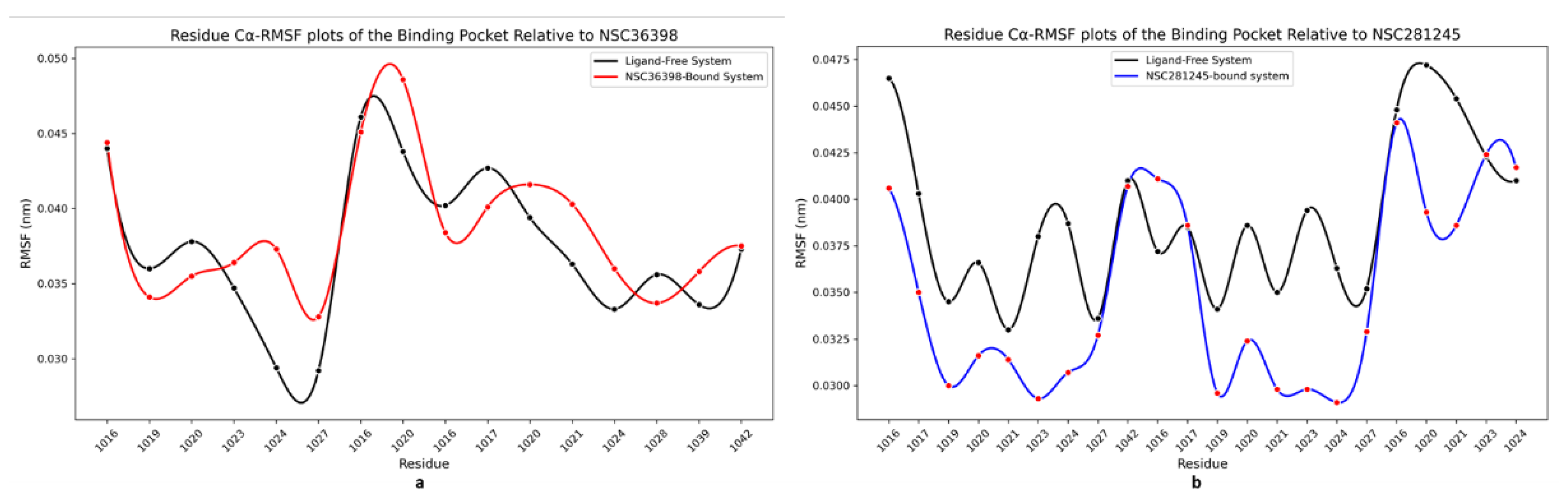

2.2.6. Cα-RMSF Analysis of Functional Domains: Binding Pocket Residues Relative to NSC36398 and NSC281245

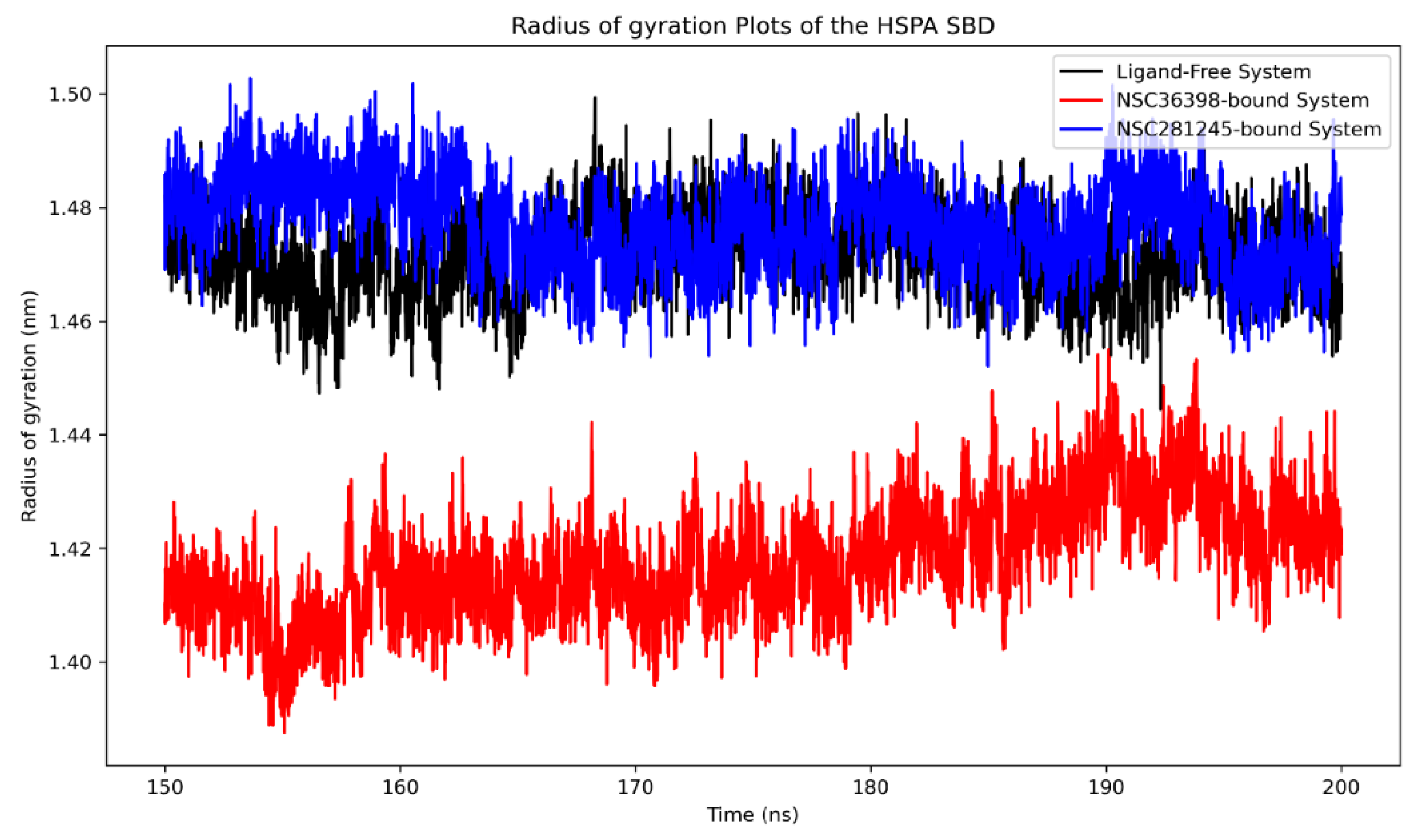

2.2.7. Radius of Gyration Analysis of Functional Domains: HSPA8 SBD

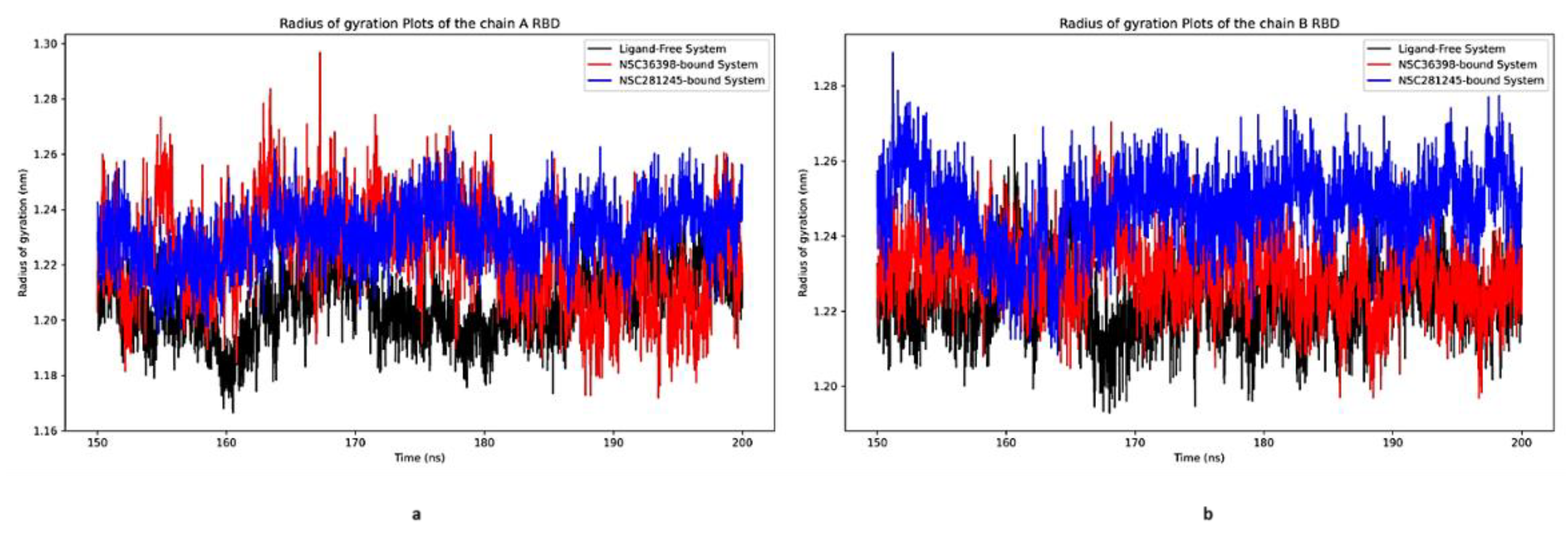

2.2.8. Radius of Gyration Analysis of Functional Domains: Spike Chain A and B RBD

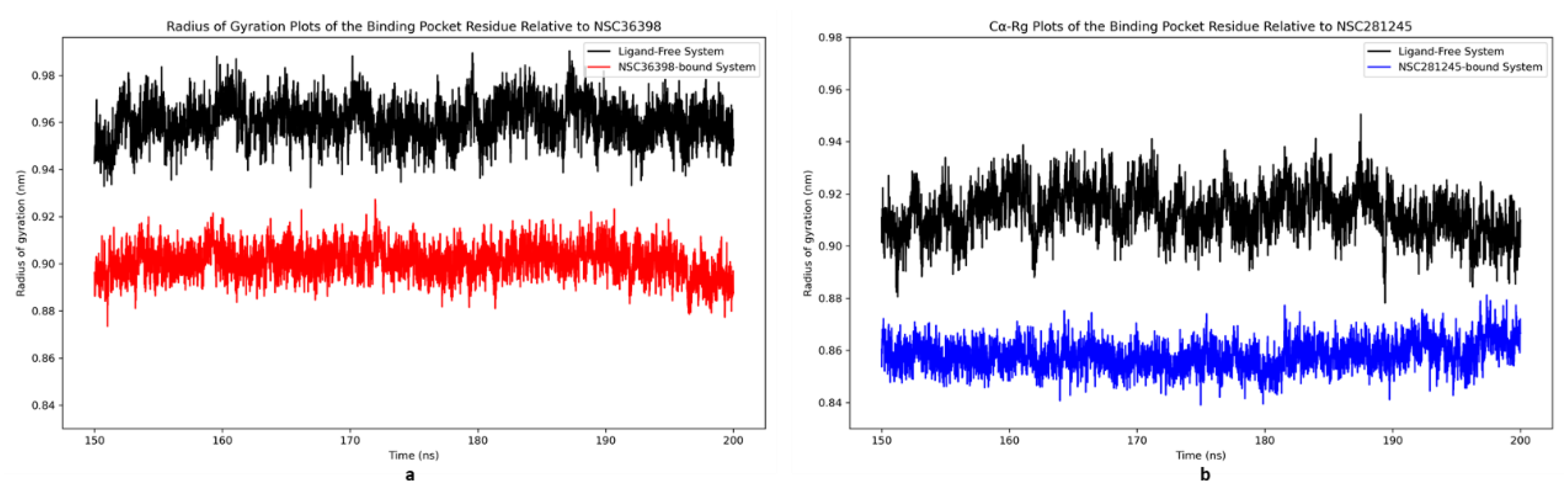

2.2.9. Radius of Gyration Analysis of Functional Domains: Binding Pocket Relative to NSC36398 and NSC281245

2.3. Conformational Dynamics Analysis

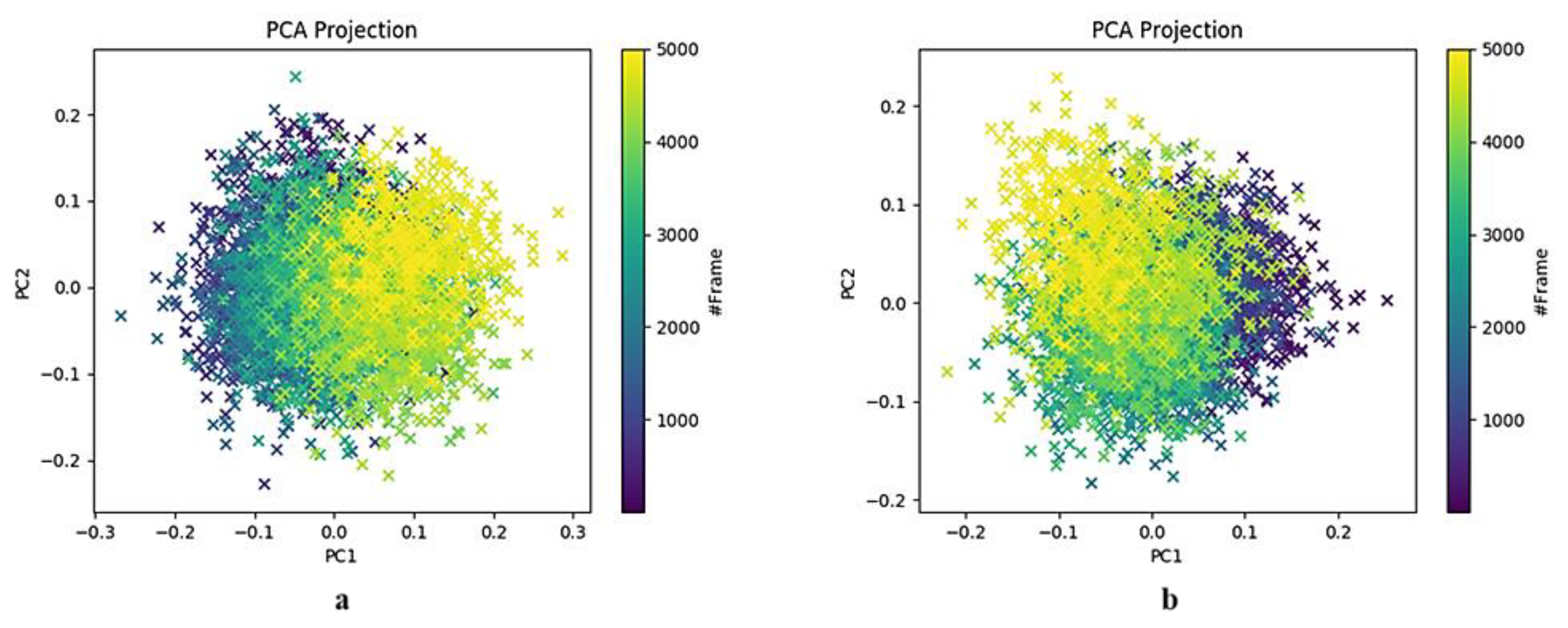

2.3.1. HSPA8 Substrate-Binding Domain Principal Component Analysis

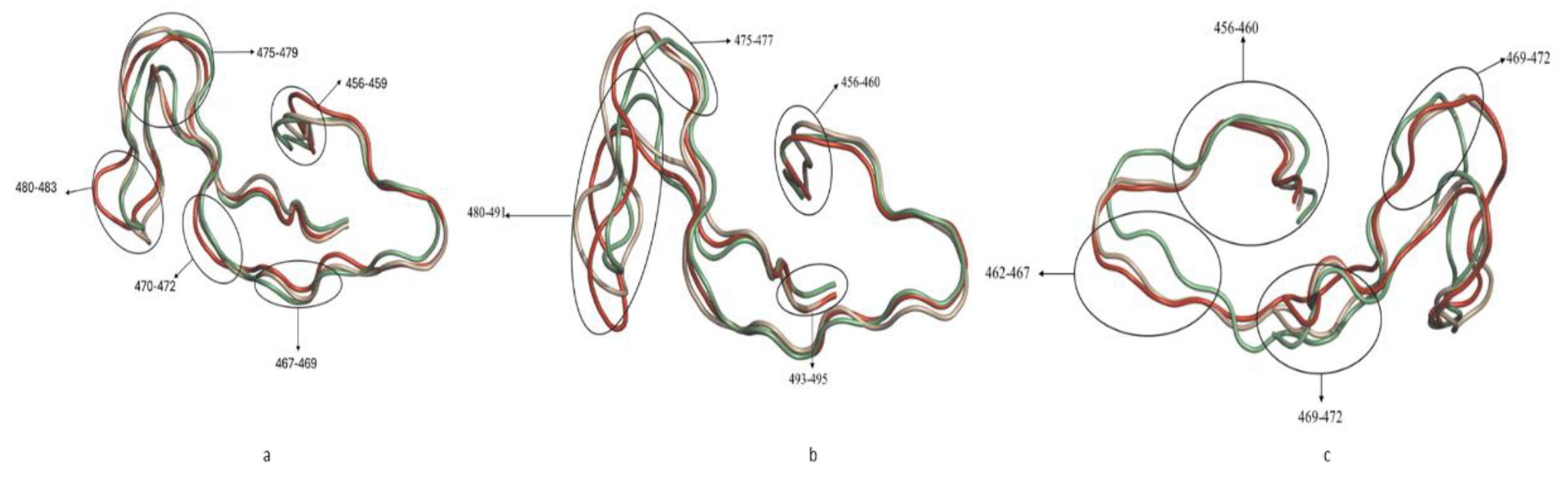

2.3.2. Spike Protein Chain A Receptor-Binding Domain Principal Component Analysis

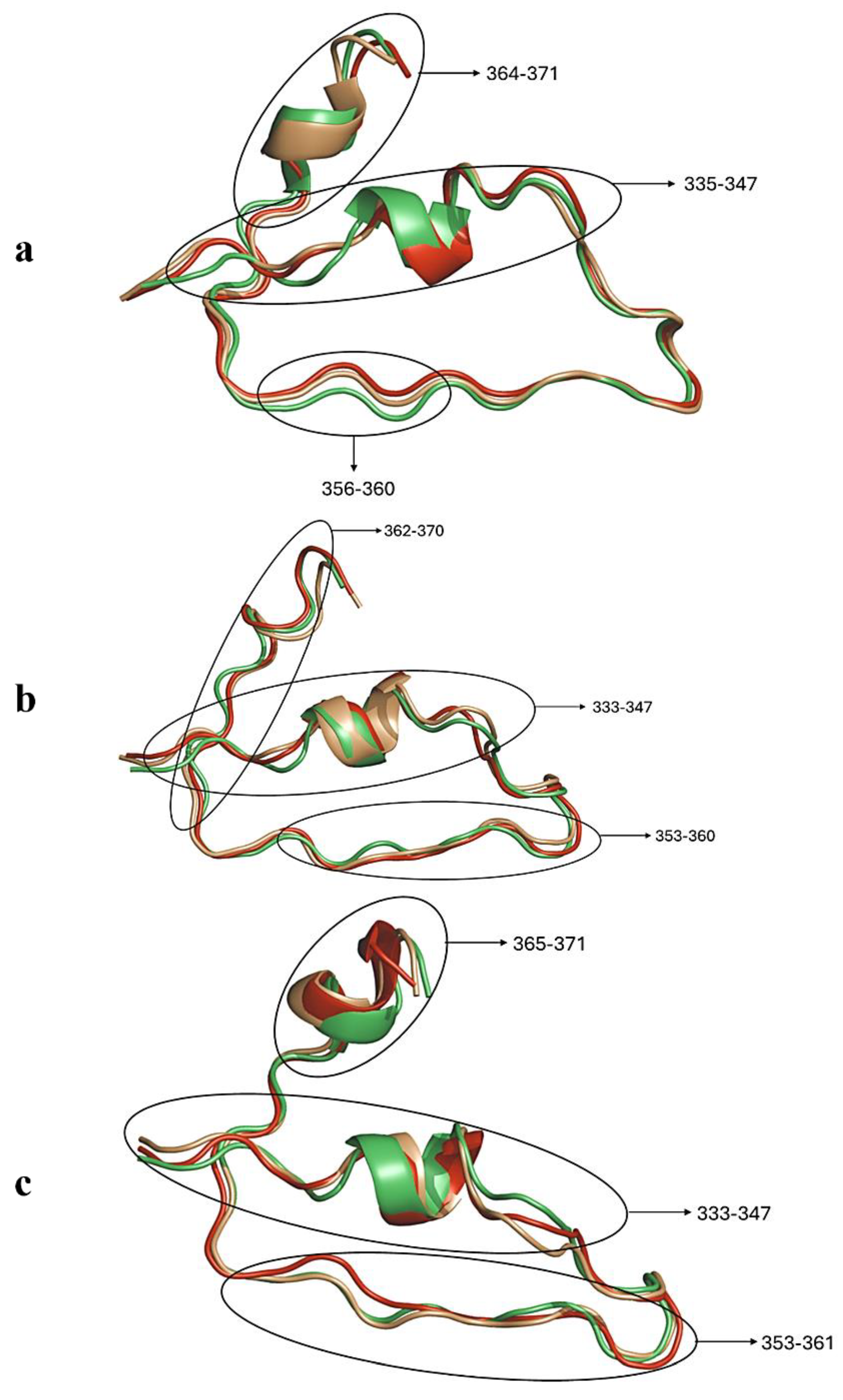

2.3.3. Spike Protein Chain B Receptor-Binding Domain Principal Component Analysis

2.3.4. Principal Component Analysis of the HSPA8–Spike Protein Complex Binding Pocket Relative to NSC36398

2.3.5. Principal Component Analysis of the HSPA8–Spike Protein Complex Binding Pocket Relative to NSC281245

2.4. Interaction Analysis

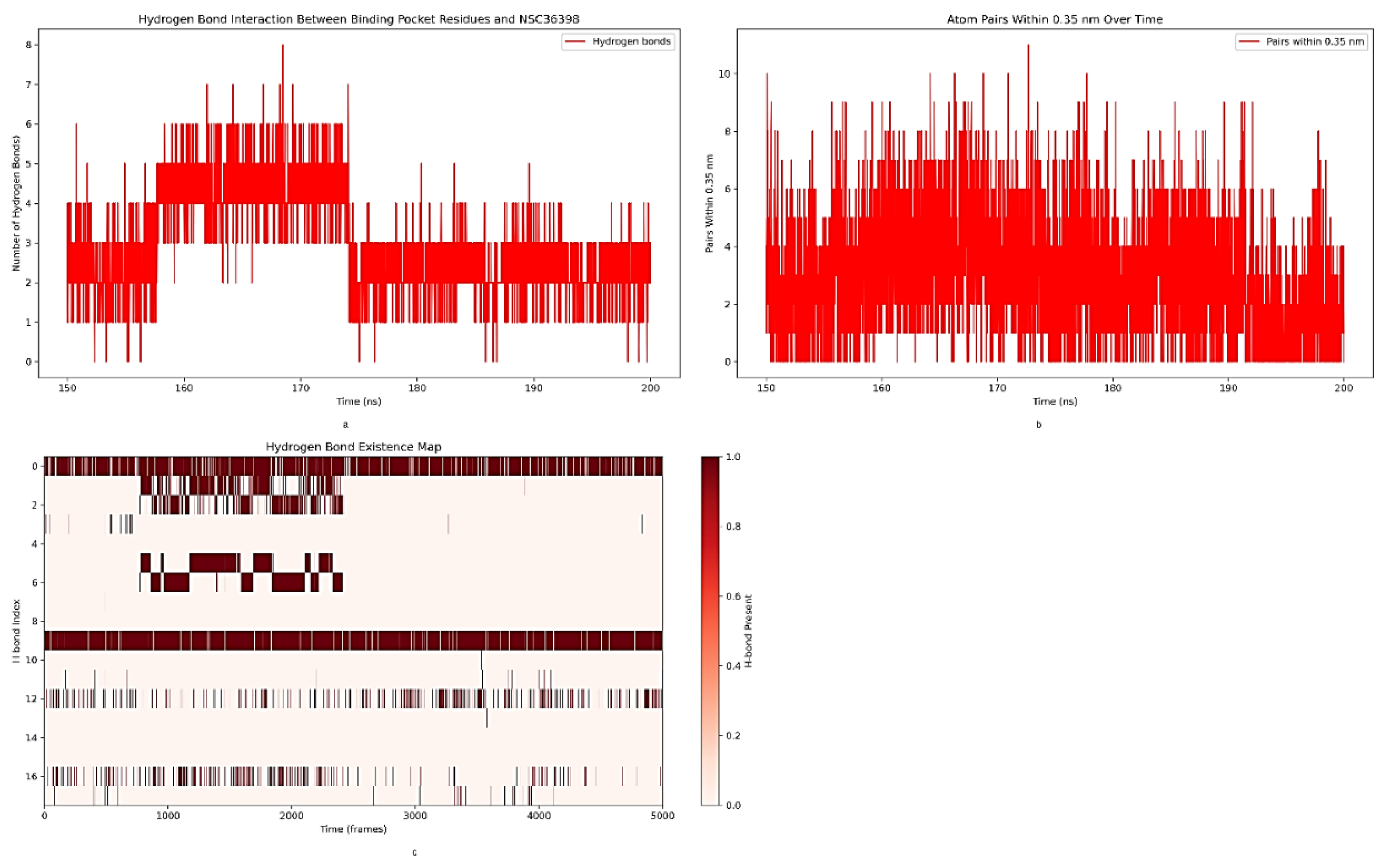

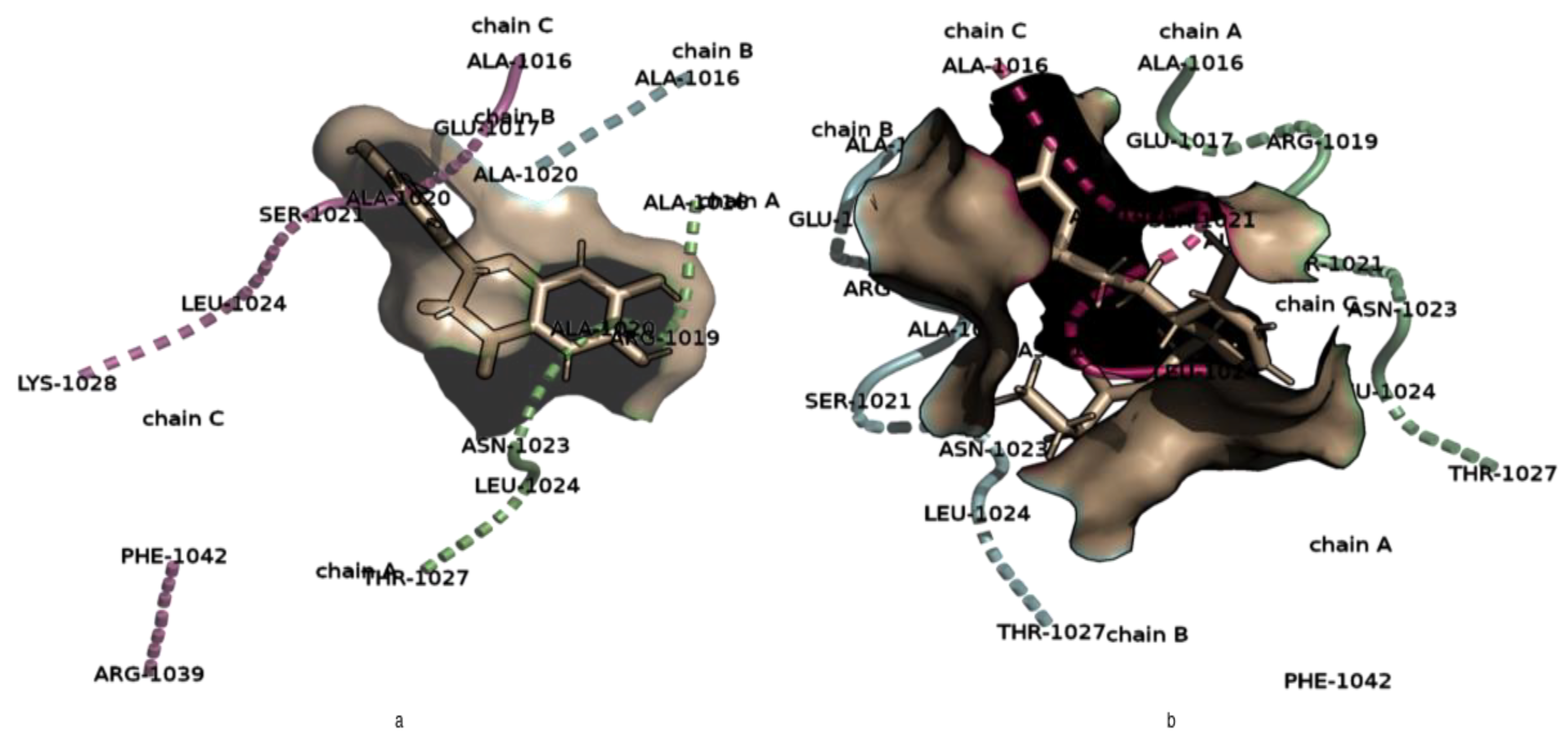

2.4.1. Analysis of Hydrogen Bond Interactions between the S2 Binding Pocket and NSC36398

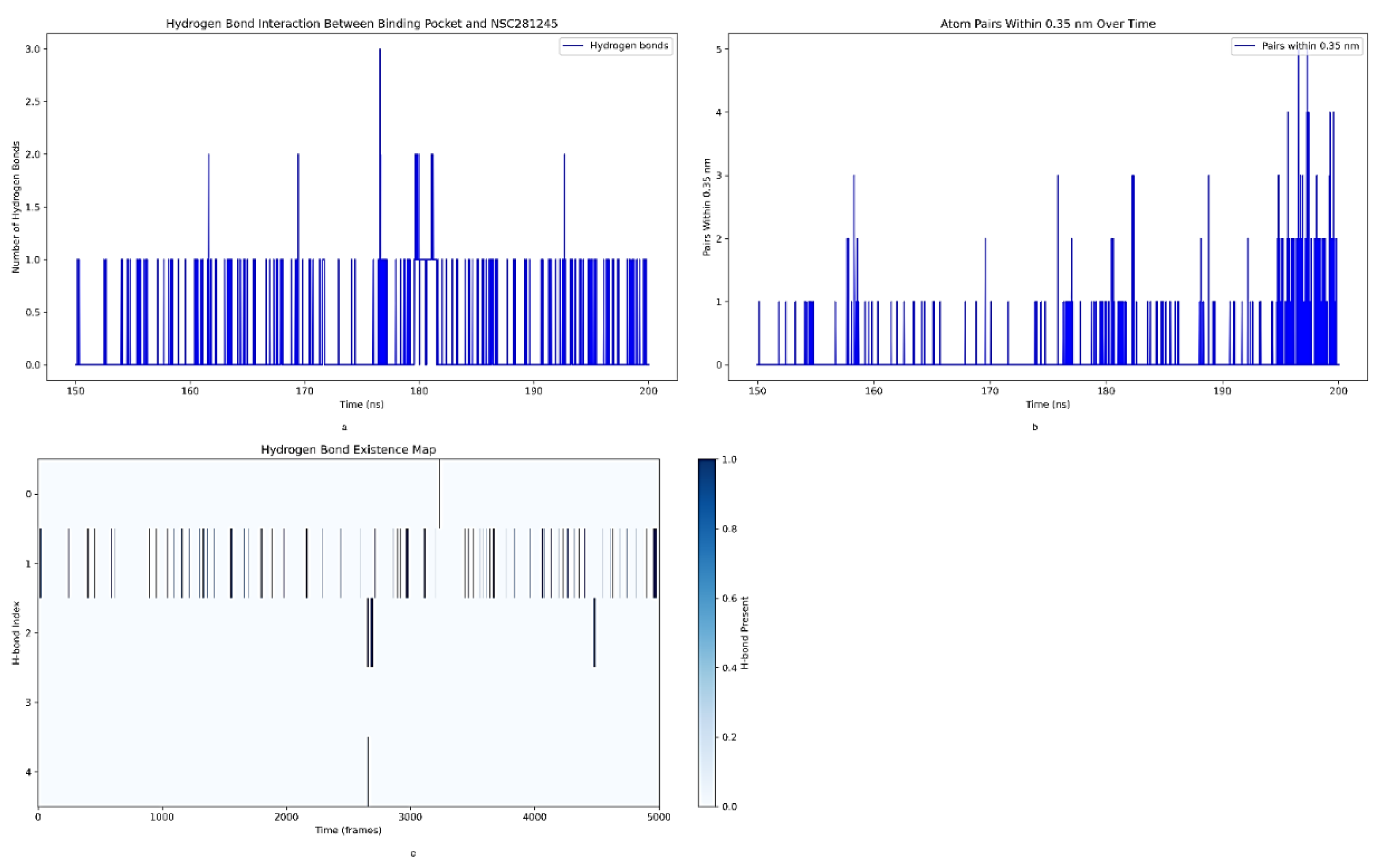

2.4.2. Analysis of Hydrogen Bond Interactions between the S2 Binding Pocket and NSC281245

2.5. Binding Free Energy Analysis

2.5.1. gmx_MMPBSA Binding Affinity Estimates

2.6. HawkDock Server 2 Binding Affinity Estimates

3. Discussion

3.1. Insights from Structural Analysis

3.2. Insights into Conformational Dynamics Analysis

3.3. Comparison of PCA Behaviour with Literature-Reported SARS-CoV-2 Mpro Inhibitors

3.4. Insights into Hydrogen Bond Interactions of the S2 Binding Pocket with NSC36398 and NSC281245

3.5. Implications of Binding Free Energy Calculation Results

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. MD System Preparation: Ligand-free and Ligand-bound System Parameter Definition

4.2. Molecular Dynamics Simulation Run

4.3. Post-MD Analysis

4.3.1. Structural Analysis

4.3.2. Conformational Dynamics Analysis

4.3.3. Hydrogen Bond Calculation Protocol

4.3.4. Binding Free Energy Calculations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACE2 | Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme 2 |

| ACPYPE | AnteChamber Python Parser Interface |

| ADMET | Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion and Toxicity |

| AMBER | Assisted Model Building with Energy Refinement |

| CHPC | Centre of High Computing |

| COVID-19 | Coronavirus Disease 2019 |

| GROMACS | GROningen MAchine for Chemical Simulations |

| HSP | Heat shock protein |

| HSPA8 | Heat Shock Protein Family A Member 8 |

| IBV | Infectious Bronchitis Virus |

| JEV | Japanese Encephalitis Virus |

| MD | Molecular Dynamics |

| MM/GBSA | Molecular Mechanics Generalised Born Surface Area |

| MM-PBSA | Molecular Mechanics Poisson-Boltzmann Surface Area |

| PC | Principal Component |

| PCA | Principal Component Analysis |

| RBD | Receptor-Binding Domain |

| RBM | Receptor-Binding Motif |

| Rg | Radius of Gyration |

| RMSD | Root Mean Square Deviation |

| RMSF | Root Mean Square Fluctuation |

| SARS-CoV-2 | Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 |

| SARS-CoV-2 Mpro | Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 Membrane Protease |

| SBD | Substrate-Binding Domain |

References

- Mallah, S.I.; Ghorab, O.K.; Al-Salmi, S.; Abdellatif, O.S.; Tharmaratnam, T.; Iskandar, M.A.; Sefen, J.A.N.; Sidhu, P.; Atallah, B.; El-Lababidi, R.; Al-Qahtani, M. COVID-19: Breaking Down a Global Health Crisis. Ann. Clin. Microbiol. Antimicrob. 2021, 20, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, G.A.; Sacco, O.; Mancino, E.; Cristiani, L.; Midulla, F. Differences and Similarities between SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2: Spike Receptor-Binding Domain Recognition and Host Cell Infection with Support of Cellular Serine Proteases. Infection 2020, 48, 665–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Cai, H.; Zhao, Y.; Li, Y.; Lai, Y.; Yao, H.; Liu, L.D.; Sun, Z.; van Vlissingen, M.F.; Kuiken, T.; GeurtsvanKessel, C.H. Uncovering a Conserved Vulnerability Site in SARS-CoV-2 by a Human Antibody. EMBO Mol. Med. 2021, 13, e14544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Guo, H.; Zhou, P.; Shi, Z.L. Characteristics of SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2021, 19, 141–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolhassani, A.; Agi, E. Heat Shock Proteins in Infection. Clin. Chim. Acta 2019, 498, 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makhoba, X.H.; Makumire, S. The Capture of Host Cell’s Resources: The Role of Heat Shock Proteins and Polyamines in SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) Pathway to Viral Infection. Biomol. Concepts 2022, 13, 220–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makhoba, X.H. Two Sides of the Same Coin: Heat Shock Proteins as Biomarkers and Therapeutic Targets for Some Complex Diseases. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2025, 12, 1491227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paladino, L.; Vitale, A.M.; Caruso Bavisotto, C.; Conway de Macario, E.; Cappello, F.; Macario, A.J.L.; Marino Gammazza, A. The Role of Molecular Chaperones in Virus Infection and Implications for Understanding and Treating COVID-19. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 3518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Q.; Chen, Y.; Bao, C.; Xiang, H.; Gao, Q.; Mao, L. Mechanism and Complex Roles of HSC70/HSPA8 in Viral Entry. Virus Res. 2024, 347, 199433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Li, Y.; Yang, X.; Zhao, J.; Cheng, Y.; Wang, J. Mechanism and Complex Roles of HSC70 in Viral Infections. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez, E.; López, S.; Cuadras, M.A.; Romero, P.; Arias, C.F. Entry of Rotaviruses Is a Multistep Process. Virology 1999, 263, 450–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, P.; Lv, C.; Fang, C.; Peng, X.; Sheng, H.; Xiao, P.; Kumar Ojha, N.; Yan, Y.; Liao, M.; Zhou, J. Heat Shock Protein Member 8 Is an Attachment Factor for Infectious Bronchitis Virus. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, J.; Ding, T.; Pan, Y.; Zhu, X.; Zhou, R.; Xie, M.; Wei, D.; Lu, M. Dysfunction of Cellular Proteostasis in Rotaviral Infection. Virol. J. 2007, 4, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuang, C.K.; Yang, T.H.; Hsiao, Y.J.; Ma, Y.P.; Syu, W.J.; Wang, Y.C. Cyclophilin A Interacts with Influenza A Virus M1 Protein and Impairs the Early Stage of Viral Replication. J. Gen. Virol. 2015, 96, 793–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navhaya, L.T.; Blessing, D.M.; Makumire, S.; Makhoba, X.H. HSP90B1 and HSP90AB1 Prevent Rotavirus Entry into Host Cells by Promoting Proteasome-Mediated Degradation of Heat Shock Cognate 70 (HSC70/HSPA8). Biomol. Concepts 2024, 15, 20220027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navhaya, L.T.; Blessing, D.M.; Makhoba, X.H. HSP70A1A (HSPA1A) Promotes Rotavirus Entry into Host Cells by Mediating Heat Shock Protein 90 (HSP90)-Dependent Folding of Heat Shock Cognate 70 (HSC70/HSPA8). Viruses 2024, 16, 1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durgam, L.; Guruprasad, L. Deciphering the Role of a Distant Exosite in Human Cyclophilin A for Shedding Coronavirus Spike Protein. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2023, 41, 3741–3751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manyumwa, C.V.; Tastan Bishop, Ö. Mechanism of Virus Inhibition and Immunomodulation by Antiviral Peptides toward SARS-CoV-2. Catalysts 2021, 11, 1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monama, M.Z.; Makhoba, X.H.; Abrahams, D. Phosphorylation Cascades Associated with Class I Phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase Isoforms. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 3313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharjee, A.; Kar, S.; Ojha, P.K. Unveiling G-Protein Coupled Receptor Kinase-5 Inhibitors to Explore Their Potency for COVID-19: A Combined Computational Study. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 269, 131784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leja, M.; Knutsson, R.; Hedenstierna, G.; Brufau, M.; Hajdu, J.; Lindahl, E.; Lindbom, L. T020 – Analyzing Molecular Dynamics Simulations to Extract Ion Binding Sites: An Educational Exercise. TeachOpenCADD 2021. [Online] Available from: https://projects.cosch.info/teaching-material/teachopencadd21/t020. (accessed on 18 April 2025).

- Srivastava, M.; Rathod, P.; Monama, M.Z.; Goswami, D.; Makhoba, X.H. An Integrative Virtual Screening Methodology to Identify Novel Anti-COVID-19 Compounds Utilizing Both Sequence and Structure of 3CLpro (Mpro) Target. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 34289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Penkler, D.L.; Kruger, P.G.; Smith, M.T.; Smith, M.C.; Eksomtramage, T.; Patel, H.; Barnes, J.; Markel, E.J.; van Deventer, H.; Jordaan, M. Investigating the Global Dynamics of a Clade 2 Influenza A Neuraminidase Reveals a Shift in Low Frequency Motions upon Drug Binding. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1600. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattarai, A.; Rohamare, S.; Kim, D.; Oh, K.S. Reassessment of the Binding Modes of OXA-66 with OXA-51-Like and OXA-23-Like Proteins in Acinetobacter baumannii Using Accelerated Molecular Dynamics Simulation. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2023, 41, 13438–13453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Z.W.; Tan, T.K.; Tria, M.A.; Pang, M.Y.; Yue, B.Y.; Ho, B.; Ding, J.L. Human Bone Marrow Endothelial Progenitor Cells: A Novel Target for Flavivirus Infections. Structure 2022, 30, 590–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaofi, A.L.; Shahid, M. SARS-CoV-2 Hotspot Mutations Associated with the Pathogenesis of COVID-19. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahamad, S.; Akhtar, N.; Alam, P.; Kumar, R.; Shahab, U. Updated Drug Repurposing for 2019-nCov/SARS-CoV-2. 3 Biotech 2022, 12, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dokainish, H.M.; Re, S.; Clouser, A.F.; Mattos, C. Adaptive Pathways of the TRP Channel through Cooling and Heating Reveals Mechanistic Insights via Molecular Dynamics Simulations. eLife 2022, 11, e75720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toelzer, C.; Gupta, K.; Yadav, S.K.N.; Borucu, U.; Davidson, A.D.; Kavanagh Williamson, M.; Shoemark, D.K.; Garzoni, F.; Staufer, O.; Milligan, R.; Capin, J.; Mulholland, A.J.; Spatz, J.P.; Fitzgerald, D.; Berger, I.; Schaffitzel, C.; Laue, E.D. Free Fatty Acid Binding Pocket in the Locked Structure of SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein. Science 2020, 370, 725–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.; Tao, P. Exploring the Binding of SF2523 Analogues with PI3K-α Protein: How Different Binding Modes Affect Conformational Dynamics and Protein Stabilization. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2021, 39, 6705–6712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stank, A.; Kokh, D.B.; Fuller, J.C.; Wade, R.C. Protein Binding Pocket Dynamics. Acc. Chem. Res. 2016, 49, 809–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kneller, D.W.; Phillips, G.; O’Neill, H.M.; Jedrzejczak, R.; Stols, L.; Langan, P.; Joachimiak, A.; Coates, L.; Kovalevsky, A. Structural Plasticity of SARS-CoV-2 3CL M<sup>pro</sup> Active Site Cavity Revealed by Room Temperature X-Ray Crystallography. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 3202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, S.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, M.; Lan, Q.; Xu, W.; Wu, Y.; Ying, T.; Liu, S.; Shi, Z.; Jiang, S.; Lu, L. Fusion Mechanism of 2019-nCoV and Fusion Inhibitors Targeting HR1 Domain in Spike Protein. Cell Res. 2020, 30, 343–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borisevich, S.S.; Kirpichnikov, M.P.; Grischenko, A.B.; Moshkovskii, S.A.; Dymova, O.A.; Eremina, E.A.; Ivanova, O.V.; Tuzikov, F.V.; Potemkin, S.A. HSP70-Targeting Inhibitors Enhance the Efficacy of an Oncolytic Adenovirus in Glioblastoma Therapy. Viruses 2022, 14, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safaeeardebili, E. Analysis of CD147 Inhibitors Using Molecular Dynamics, Quantum and Pharmacophore Approaches. Ph.D. Thesis, Politecnico di Torino, Turin, Italy, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, C.B.; Farzan, M.; Chen, B.; Choe, H. Mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2 Entry into Cells. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2022, 23, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, X. Domains and Functions of Spike Protein in SARS-CoV-2 in Context of Vaccine Design. Viruses 2021, 13, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wankowicz, S.A.; de Oliveira, S.H.; Hogan, D.W.; van den Bedem, H.; Fraser, J.S. Ligand Binding Remodels Protein Side-Chain Conformational Heterogeneity. eLife 2022, 11, e74114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradi, S.; Evora, L.; Menezes, R.; Mahdavifar, M.D.; Forli, E.; Soares, T.A. Exploration of Druggable Cavities within SARS-CoV-2 Spike Glycoprotein. Comput. Biol. Med. 2024, 183, 109245. [Google Scholar]

- Valério, M.; Sampaio, F.M.; Sterpone, F. A Multiscale In Silico Modeling for SARS-CoV-2 Research (MISCORE). Front. Med. Technol. 2022, 4, 1009451. [Google Scholar]

- Amamuddy, O.S.; Glenister, M.; Tshabalala, T.; Bishop, Ö.T. MDM-TASK-Web: MD-TASK and MODE-TASK Web Server for Analyzing Protein Dynamics. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2021, 19, 5059–5071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amusengeri, A.; Singh, A.; Bishnoi, S.; Makhoba, X.H. In Silico Discovery and Molecular Mechanistic Insight into Drugs as Potential Inhibitors of IKBKE in the Treatment of COVID-19. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 5574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sankar, K.; Magarkar, A.; Malik, R.; Raghunandan, D.; Nag, A.; Agrawal, V. Sulfobetaine-Containing Lipid Bilayers: Insights from a Molecular Dynamics Simulation. J. Chem. Phys. 2015, 143, 245103. [Google Scholar]

- Melero, R.; Grubaugh, N.D.; Wyss, R.; Subramaniam, S.; Chacon, P.; Borgnia, M.J. Continuous Flexibility Analysis of SARS-CoV-2 Spike Prefusion Structures. IUCrJ 2014, 7, 1059–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, D.; Jia, R.; Zucker, J.; Verma, S.; Cho, W.; Tao, P.; Bowen, J.D.; Hartman, M.G.; Bloom, M.E.; Kapoor, T.M.; Rao, Z.; Iyengar, R. Structural Insights into the Small Molecule Antiviral Compound Arbidol and SARS-CoV-2 S-Protein Interaction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2021, 118, e2100943118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luque, I.; Freire, E. Structure of Proteins: Energy, Entropy and Free Energy. Proteins 2000, 41 (Suppl. 4), 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gowo, P. In Silico Identification of Potential Vaccine Targets for the Prevention of Clinical Dengue Fever. Ph.D. Thesis, Rhodes University, 2021.

- Csermely, P.; Sandhu, K.S.; Hazai, E.; Hoksza, Z.; Kiss, H.J.; Miozzo, F.; Olbei, M.; Rákhely, Z.; Szalay, M.S.; Veres, D.V. Disordered Proteins and Network Disorder in Network Descriptions of Protein Structure, Dynamics and Function: Hypotheses and Facts. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2010, 35, 539–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nussinov, R.; Tsai, C.-J. Allostery in Disease and in Drug Discovery. Biophys. Chem. 2014, 186, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravasio, R.; Romanovski, V.; Maritan, A.; Micheletti, C. Inferring Contact Energies from a Two-Dimensional Gaussian Graph Model of the Protein Structure. Biophys. J. 2019, 117, 1954–1962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, B.R.; McGee, T.D.; Swails, J.M.; Homeyer, N.; Gohlke, H.; Roitberg, A.E. MMPBSA.py: An efficient program for end-state free energy calculations. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2012, 8, 3314–3321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Xiao, T.; Cai, Y.; Chen, B. Structure of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2021, 50, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandal, M.; Mandal, S. MM/GB(PB)SA integrated with molecular docking and ADMET approach to inhibit the fat-mass-and-obesity-associated protein using bioactive compounds derived from food plants used in traditional Chinese medicine. Pharmacol. Res. Mod. Chin. Med. 2024, 11, 100435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, P.; Garg, S.; Mani, S.; Shoaib, R.; Jakhar, K.; Almuqdadi, H.T.A.; Sonar, S.; Marothia, M.; Behl, A.; Biswas, S.; Singhal, J. Targeting host inducible-heat shock protein 70 with PES-Cl is a promising antiviral strategy against SARS-CoV-2 infection and pathogenesis. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 279, 135069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verkhivker, G.M.; Di Paola, L. Dynamic network modeling of allosteric interactions and communication pathways in the SARS-CoV-2 spike trimer mutants: differential modulation of conformational landscapes and signal transmission via cascades of regulatory switches. J. Phys. Chem. B 2021, 125, 850–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amadei, A.; Linssen, A.B.; Berendsen, H.J.C. Essential dynamics of proteins. Proteins 1993, 17, 412–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhattacharya, S. Small molecule inhibitors. In Spatially Variable Genes in Cancer: Development, Progression, and Treatment Response; Raghavan, R., Ed.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2024; p. 447. [Google Scholar]

- Abraham, M.J.; Murtola, T.; Schulz, R.; Páll, S.; Smith, J.C.; Hess, B.; Lindahl, E. GROMACS: High performance molecular simulations through multi-level parallelism from laptops to supercomputers. SoftwareX 2015, 1, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa da Silva, A.W.; Vranken, W.F. ACPYPE—AnteChamber PYthon Parser interfacE. BMC Res. Notes 2012, 5, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasidharan, S.; Shukla, R.; Tripathi, T.; Saudagar, P. pH-based molecular dynamics simulation for analysing protein structure and folding. In Protein Folding Dynamics and Stability: Experimental and Computational Methods; Saudagar, P., Tripathi, T., Eds.; Springer Nature Singapore: Singapore, 2023; pp. 203–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piplani, S.; Singh, P.K.; Winkler, D.A.; Petrovsky, N. In silico comparison of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein-ACE2 binding affinities across species and implications for virus origin. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 13063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, G.; Xi, W.; Nussinov, R.; Ma, B. Protein ensembles: how does nature harness thermodynamic fluctuations for life? Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 6516–6551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdés-Tresanco, M.S.; Valdés-Tresanco, M.E.; Valiente, P.A.; Moreno, E. gmx_MMPBSA: A new tool to perform end-state free energy calculations with GROMACS. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2021, 17, 6281–6291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onufriev, A.; Bashford, D.; Case, D.A. Exploring protein native states and large-scale conformational changes with a modified generalized Born model. Proteins 2004, 55, 383–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Energy Component | ΔEnergy (Complex–Receptor–Ligand) (kcal/mol) |

SEM |

|---|---|---|

| ΔVDWAALS | –10.35 | 0.05 |

| ΔEEL | –9.45 | 0.08 |

| ΔEGB | 14.88 | 0.06 |

| ΔESURF | –2.15 | 0.00 |

| ΔGGAS | –19.80 | 0.08 |

| ΔGSOLV | 12.72 | 0.06 |

| ΔTOTAL/BIND | –7.07 | 0.04 |

| Energy Component | ΔEnergy (Complex–Receptor–Ligand) (kcal/mol) |

SEM |

|---|---|---|

| ΔVDWAALS | –37.80 | 0.07 |

| ΔEEL | –12.99 | 0.13 |

| ΔEGB | 28.72 | 0.11 |

| ΔESURF | –5.56 | 0.01 |

| ΔGGAS | –50.79 | 0.14 |

| ΔGSOLV | 23.16 | 0.11 |

| ΔTOTAL/BIND | –27.63 | 0.07 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).