1. Introduction

Vitamin C (L-ascorbic acid) is an essential nutrient that functions as a critical antioxidant and cofactor in numerous biochemical processes, including collagen synthesis, neurotransmitter production, and immune function.[

1] Its role extends to the modulation of cellular redox states, gene regulation via HIF-1α, and the maintenance of epigenetic stability in stem cells, underscoring its importance beyond simple nutritional requirements.[

2,

3,

4,

5,

6] Recent comprehensive reviews have emphasized vitamin C’s pleiotropic biological effects, demonstrating that beyond its well-established antioxidant properties, it exhibits complex dose-dependent behaviors, including pro-oxidant effects at high concentrations that are being investigated for therapeutic applications in cancer treatment. [

7,

8,

9] Furthermore, emerging research has revealed vitamin C’s pivotal role in promoting angiogenesis, enhancing extracellular matrix stabilization, and modulating tissue remodeling processes, particularly in cardiovascular health. [

10]

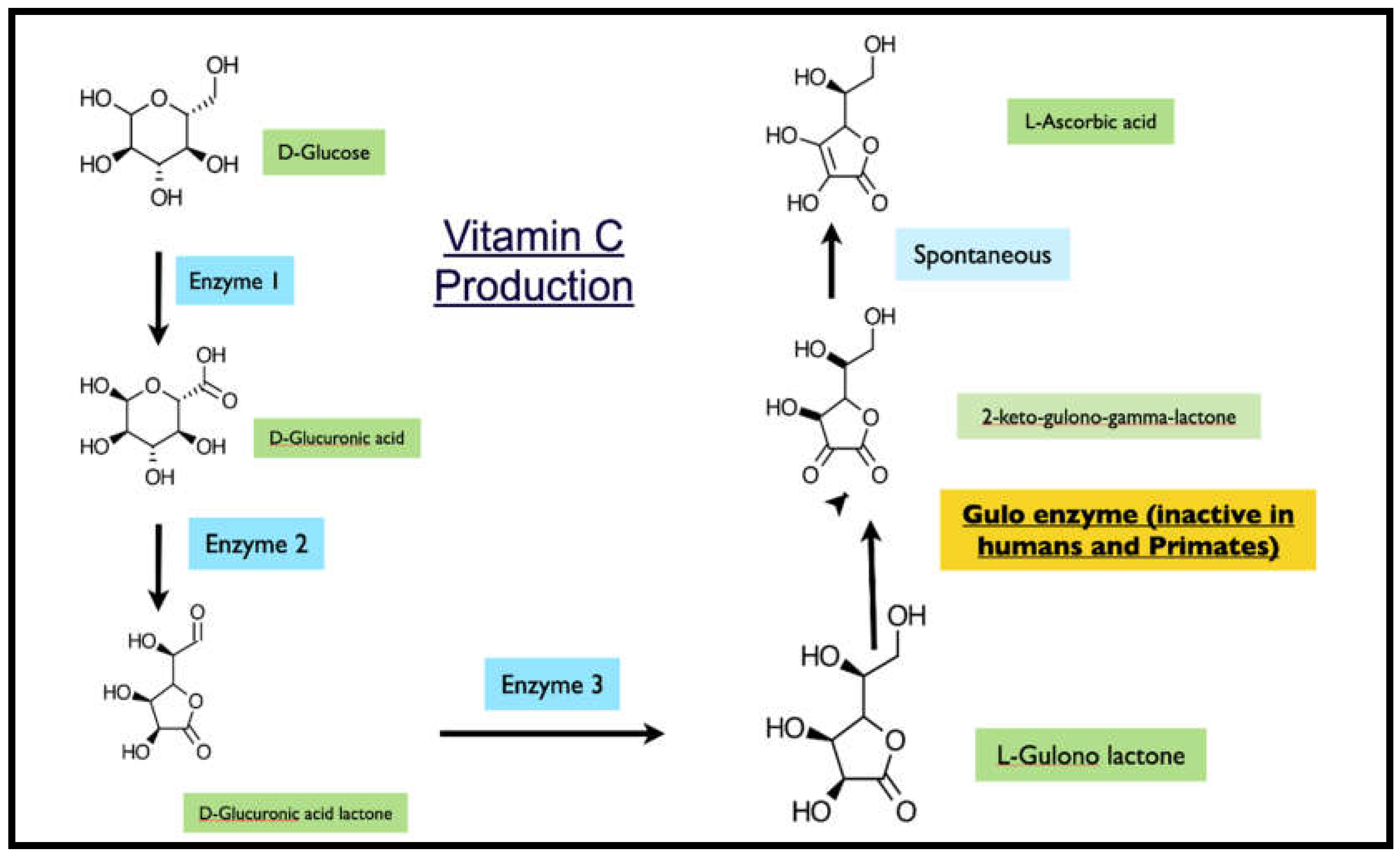

Most mammalian species can synthesize vitamin C endogenously through a four-enzyme pathway that converts glucose to ascorbic acid, with L-gulonolactone oxidase (GULO) catalyzing the terminal step.[

11] However, this biosynthetic capacity has been independently lost in several evolutionary lineages, including anthropoid primates (approximately 63 million years ago), guinea pigs (14 million years ago), and particular bat species, rendering these animals dependent on dietary sources of vitamin C.[

12] Recent molecular evolutionary studies have refined this timeline, demonstrating that the GULO gene was specifically deactivated 61 million years ago for Haplorrhini primates (the suborder of higher primates including humans), with chromosome 8 inversions and exon mutations confirming common evolutionary patterns among all primates, including Homo neanderthalensis.[

13] The GULO enzyme belongs to the aldonolactone oxidoreductases (AlORs) family and contains two highly conserved domains: an N-terminal FAD-binding region and a C-terminal HWXK motif capable of binding the flavin cofactor, with recent research demonstrating that even recombinant C-terminal fragments retain enzymatic activity.[

14] This evolutionary progression shows a transition from vitamin C synthesis in the kidneys to liver-based production in more advanced mammals, highlighting the complexity of this biosynthetic pathway’s evolutionary development.[

15]

Recent clinical studies have documented contemporary cases of scurvy in pediatric populations subsisting on processed diets devoid of fresh produce, with characteristic presentations including lower limb pain, subperiosteal hemorrhages, and distinctive radiographic findings.[

16] Furthermore, endogenous vitamin C synthesis in mammals often vastly exceeds amounts attainable through diet alone, with normal production ranging from 1,800 to 4,000 mg daily and surging further during periods of physiological stress. [

17] Recent cardiovascular research has elucidated specific mechanisms by which vitamin C deficiency contributes to disease pathogenesis, including impaired endothelial function through reduced tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4) protection, increased NADPH oxidase activity leading to elevated reactive oxygen species production, and compromised collagen synthesis affecting vascular integrity. [

18] Studies have quantified vitamin C’s therapeutic potential, demonstrating up to 33% increases in total antioxidant capacity in individuals with insulin resistance, while also showing protective effects against cardiovascular-kidney-metabolic syndrome progression.[

19] The vitamin’s role in neurodegeneration prevention has been further substantiated, with recent evidence indicating its capacity to reduce neuroinflammation, promote neurotransmitter production, and potentially lower Alzheimer’s disease risk through multiple molecular mechanisms including epigenetic modifications and immune system modulation.[

20] This gap highlights not only an evolutionary trade-off but an urgent contemporary challenge in achieving optimal antioxidant protection, with current recommendations suggesting consistent intake of approximately 200 mg daily through combined dietary sources and supplementation to maintain adequate physiological levels and prevent deficiency-related complications. [

21]

Metadichol, a patented nanoemulsion composed of long-chain saturated alcohols (C26, C28, and C30) derived from policosanol, represents a novel approach to addressing this deficiency.[

22] Clinical studies have demonstrated that Metadichol supplementation can elevate plasma vitamin C levels by 3–4 fold without direct exogenous administration, implying either pharmacological enhancement of biosynthetic or recycling pathways [

23,

24,

25] Emerging research suggests Metadichol exerts its multi-pathway effects as an inverse agonist of nuclear receptors, modulating the transcription of over 2,300 genes involved in diverse processes such as metabolism, immune response, and cellular stress tolerance. [

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34] The mechanisms underlying these effects are not fully delineated, but evidence points to coordinated activation of antioxidant and metabolic pathways, possibly including direct stimulation of the GULO enzyme in vitamin C-capable species.[

24,

25]

Recent advances in gene editing and cell reprogramming have re-ignited interest in restoring lost biosynthetic traits. Gene therapy studies in GULO knockout mice have successfully employed viral vectors to reinstate endogenous vitamin C production, validating the functional significance and therapeutic potential of this pathway.[

35,

36,

37] Against this backdrop, Metadichol offers an alternative, non-genetic approach to activating dormant or suppressed metabolic networks, leveraging pharmacological modulation rather than permanent gene alteration.

Despite significant progress, a comprehensive multi-species assessment of Metadichol’s impact on GULO expression has not been previously reported. The present study seeks to address this gap by systematically evaluating Metadichol’s effect on GULO gene expression across four mammalian cell lines: rat, mouse, bovine, and swine. This work aims to clarify dose-response relationships, species-specific sensitivities, and the broader implications for therapeutic reactivation of vitamin C biosynthesis machinery. By integrating cross-species cellular models and translational biomarker analysis, these findings may pave the way for precision nutritional interventions capable of overcoming entrenched genetic limitations.

This enrichment retains the original citations and structure but adds context on cellular defense, evolutionary implications, gene therapy advances, and future clinical relevance, providing a more comprehensive scientific foundation for the study.

Figure 1.

Glucose to Vitamin C pathway.

Figure 1.

Glucose to Vitamin C pathway.

1.1. Experimental

All work was outsourced to and carried out by commercial service provider Skanfa Labs, Bangalore, India. The primers were obtained from Eurofins Bangalore, India, and the other reagents and chemicals from Sigma-Aldrich Bangalore, India.

1.2. Cell Culture and Treatment

Four mammalian cell lines were utilized: L6 (rat skeletal muscle), C2C12 (mouse myoblast), bovine peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs), and swine PBMCs. Cells were maintained in DMEM or RPMI medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin-streptomycin at 37°C with 5% CO2. Cell density was adjusted to 1×106 cells/ml and seeded into 6-well plates. After 24-hour incubation, cells were treated with Metadichol at concentrations of 1 pg/ml, 100 pg/ml, one ng/ml, and 100 ng/ml for 24 hours. Control groups received a vehicle only.

1.3. Sample Preparation and RNA Isolation

The treated cells were dissociated, rinsed with sterile 1X PBS and centrifuged. The supernatant was decanted, and 0.1 ml of TRIzol was added and gently mixed by inversion for 1 min. The samples were allowed to stand for 10 min at room temperature. To this mixture, 0.75 ml of chloroform was added per 0.1 ml of TRIzol used. The contents were vortexed for 15 seconds. The tube was allowed to stand at room temperature for 5 mins. The resulting mixture was centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 15 min at 4°C. The upper aqueous phase was collected in a new sterile microcentrifuge tube, to which 0.25 ml of isopropanol was added, and the mixture was gently mixed by inverting the contents for 30 seconds and then incubated at -20°C for 20 minutes. The contents were subsequently centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 10 minutes at 4°C. The supernatant was discarded, and the RNA pellet was washed by adding 0.25 ml of 70% ethanol. The RNA mixture was subsequently centrifuged at 12,000 rpm at 4°C. The supernatant was carefully discarded, and the pellet was air dried. The RNA pellet was then resuspended in 20 μl of DEPC-treated water. The total RNA yield was quantified via a Spectra drop Spectramax i3x, Molecular Devices, USA. RNA integrity was confirmed through spectrophotometric analysis, and all samples yielded high-quality RNA suitable for qPCR.

1.4. RNA Yield/Quality and GAPDH Expression Stability

Total RNA yields were consistently high across all treatment groups, ranging from 324.5-572.1 ng/μl, with no significant differences between control and treated groups, indicating that Metadichol treatment did not adversely affect cell viability or RNA integrity. GAPDH expression remained stable across all treatment conditions in each species, with cycle threshold (Cq) values showing minimal variation (CV <5%), confirming its suitability as a reference gene for normalization.

1.5. Primers and qPCR analysis

qRT-PCR was performed using SyBR Green I PCR Master Mix with species-specific primers for GULO and

GAPDH (housekeeping gene). Primer sequences (

Table 1) were designed to amplify products of 131-286 base pairs with optimal annealing temperatures. Thermal cycling conditions included initial denaturation at 95°C for 2 minutes, followed by 39 cycles of 95°C for 5 seconds and 30 seconds at the appropriate annealing temperature. The PCR mixture final volume of 20 μl contained 1.4 μl of cDNA, 10 μl of SYBR Green Master mix, and 1 μM complementary forward and reverse primers specific for the respective target genes. The reaction was carried out with enzyme activation at 95°C for 2 minutes, followed by a 2-step reaction with initial denaturation and an annealing-cum-extension step at 95°C for 5 seconds, annealing for 30 seconds at the appropriate respective temperature amplified for 39 cycles, followed by secondary denaturation at 95°C for 5 seconds, and 1 cycle with a melt curve capture step ranging from 65°C to 95°C for 5 seconds each. The obtained results were analyzed, and the fold change in expression or regulation was calculated.

The fold change was calculated via the following equation:

ΔΔ CT Method

The relative expression of the target gene in relation to the housekeeping gene β-actin and untreated control cells was determined via the comparative CT method.

The delta CT for each treatment was calculated via the following formula:

Delta Ct = Ct target gene – Ct reference gene

To compare the individual sample from the treatment with the untreated control, the delta CT of the sample was subtracted from the control to obtain a delta delta CT.

Delta delta Ct = delta Ct treatment group – delta Ct control group

The fold change in target gene expression for each treatment was calculated via the following formula:Fold change = 2^-deltadelta Ct

Key Features:

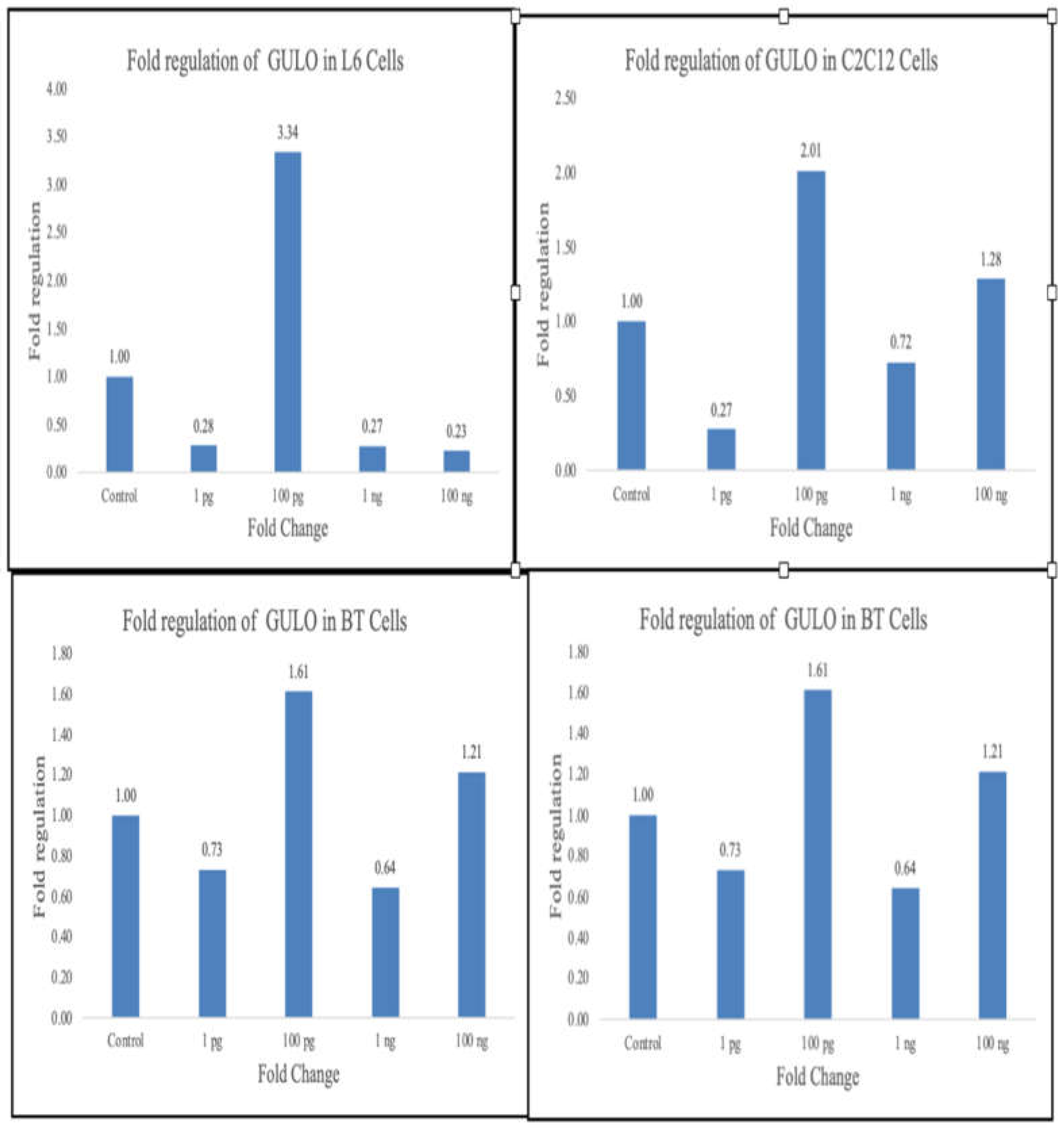

Main Results Table 2 and Figure 2. Complete dataset with all species and concentrations, clearly highlighting significant upregulation (≥1.5-fold)

Dose-Response Analysis:

Table 3. 3 Shows patterns across concentrations and identifies optimal dosing windows

Statistical Summary Table 4: Compares maximum responses and concentration ranges between species

Response Distribution Table 5: Analyzes how many species respond at each concentration level

Technical Data Table 6: Includes qPCR parameters for transparency and reproducibility

Rat Cells (L6)

Metadichol treatment produced differential effects on GULO expression in rat cells. The most significant upregulation occurred at 100 pg/ml concentration, resulting in a 3.34-fold increase compared to control (ΔΔCq = -1.74). Higher concentrations (1 ng/ml and 100 ng/ml) showed reduced expression (0.27-fold and 0.23-fold, respectively), while one pg/ml treatment resulted in decreased expression (0.28-fold).

Mouse Cells (C2C12)

Mouse cells demonstrated optimal GULO upregulation at 100 pg/ml (2.01-fold increase, ΔΔCq = -1.01) and showed sustained elevation at 100 ng/ml (1.28-fold increase). Lower concentrations produced mixed results, with one pg/ml showing decreased expression (0.27-fold) and one ng/ml producing a modest reduction (0.72-fold).

Bovine Cells

Bovine PBMCs exhibited more moderate but consistent responses, with upregulation observed at both 100 pg/ml (1.61-fold) and 100 ng/ml (1.21-fold) concentrations. Lower concentrations (1 pg/ml and one ng/ml) resulted in slight decreases in expression (0.73-fold and 0.64-fold, respectively).

Swine Cells

Swine cells showed the highest response at the lowest concentration tested, with 1.93-fold upregulation at one pg/ml. Higher concentrations generally produced decreased expression, with 100 pg/ml, one ng/ml, and 100 ng/ml showing 0.62-fold, 0.99-fold, and 0.81-fold changes, respectively.

Figure 2.

Summary of gulo expression changes.

Figure 2.

Summary of gulo expression changes.

2. Discussion

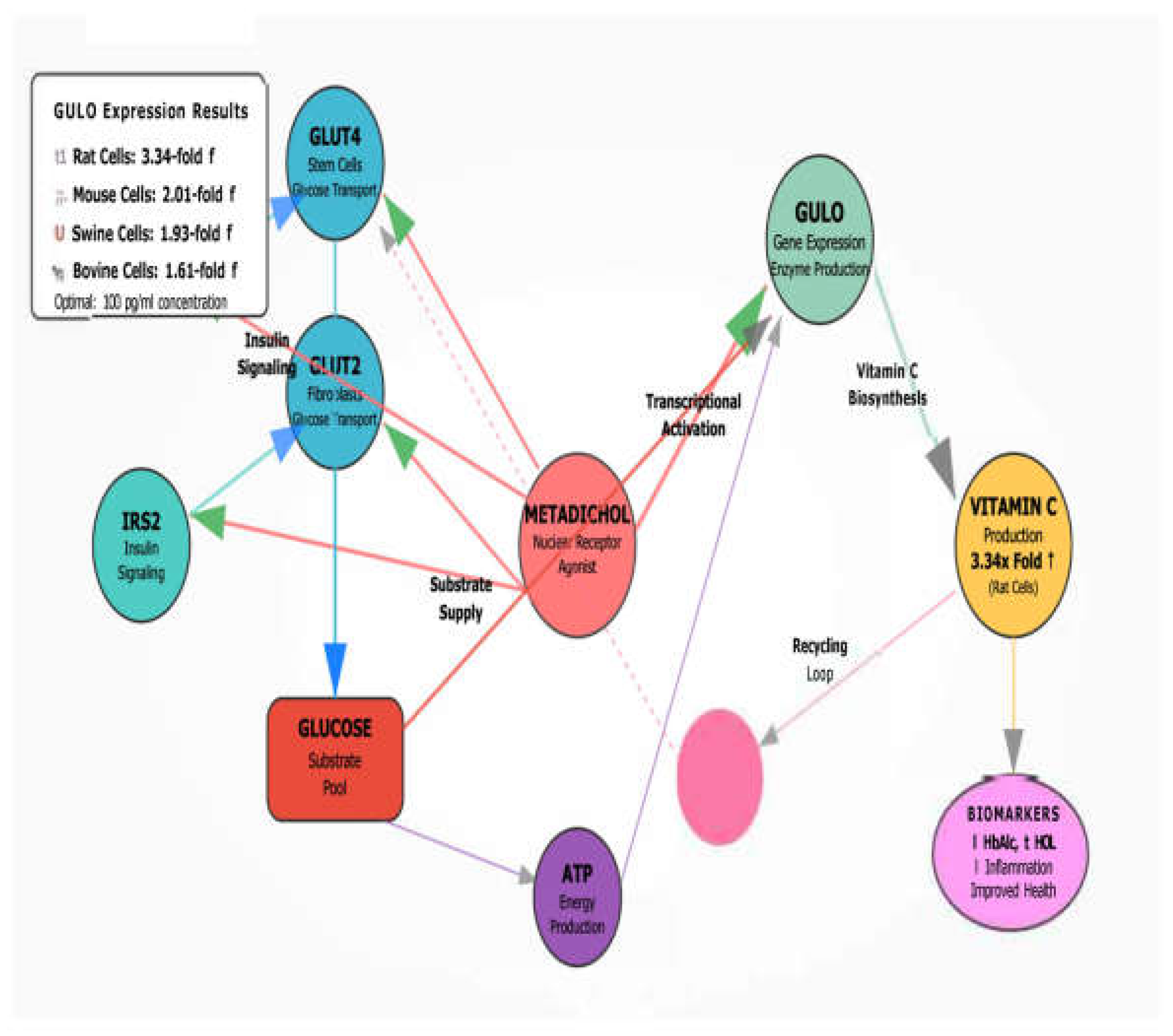

We have previously shown that Metadichol increases GULO expression [

25] in mouse adipocytes by 3.96-fold. This study provides the first comprehensive cross-species analysis of Metadichol’s ability to enhance GULO gene expression, demonstrating significant upregulation across multiple mammalian cell lines at picogram to nanogram concentrations. These findings have important implications for understanding the mechanisms underlying Metadichol’s documented ability to increase endogenous vitamin C levels in clinical studies [

23,

24].

The species-specific differences in optimal concentrations may reflect variations in receptor expression profiles, cellular uptake mechanisms, or metabolic processing of Metadichol. The biphasic dose-response observed in some species, where higher concentrations produced reduced effects, suggests potential receptor saturation or activation of inhibitory pathways at supraphysiological doses.

While humans possess only a nonfunctional GULO pseudogene, these results have several important clinical implications. First, they provide mechanistic validation for Metadichol’s documented effects on vitamin C levels [

25,

26] which may involve enhancement of alternative biosynthetic pathways or improved recycling mechanisms.

The therapeutic potential of restoring vitamin C biosynthesis has been demonstrated in gene therapy studies using GULO knockout mice, where viral vector-mediated GULO expression successfully restored endogenous vitamin C production. [

38,

39]

The loss of GULO function in specific mammalian lineages represents a fascinating evolutionary phenomenon that has been extensively studied. [

40,

41]Our results suggest that pharmacological reactivation of vitamin C biosynthesis machinery is possible in species retaining functional genes, potentially offering insights into the evolutionary pressures that led to GULO gene loss.

The observed effects align with clinical studies showing 3-4 fold increases in plasma vitamin C levels following Metadichol supplementation in humans. [

25,

26,

27] While the mechanism in humans likely differs due to the absence of functional GULO, the consistent theme of enhanced vitamin C availability supports the compound’s potential therapeutic value.

Biomarker results (

Table 7 in the Zucker diabetic rat studies [

22] provide strong mechanistic validation for the GULO upregulation findings. The key connections are:

Direct validation: The biomarker table shows increased vitamin C, which directly confirms that GULO upregulation translates to functional vitamin C production in vivo.

Integrated antioxidant response: The combination of increased vitamin C, increased glutathione, and decreased protein oxidation suggests a coordinated antioxidant defense system activation, with GULO being a key component.

Metabolic optimization: The numerous metabolic improvements (glucose control, insulin sensitivity, and lipid profile) create an optimal cellular environment for gene expression, including GULO.

Anti-inflammatory environment: The inhibition of inflammatory pathways (TNFα, NFκB, hSCRP, MCP1) removes barriers to beneficial gene expression.

Nuclear receptor coordination: The broad spectrum of biomarker changes suggests coordinated nuclear receptor activation, with GULO upregulation being part of a comprehensive transcriptional program.

This provides a much richer context for understanding why the GULO upregulation observed in the cell culture studies is biologically meaningful and translates to therapeutic benefits in animal models.

The biomarker profile reveals Metadichol orchestrates a comprehensive antioxidant response:

Increases Vitamin C (direct GULO product)

Increased Glutathione Levels (master antioxidant)

Decreased Protein Oxidation (protection from oxidative damage)

This suggests GULO upregulation is part of a coordinated cellular antioxidant defense strategy, not an isolated effect. The metabolic improvements create ideal conditions for GULO upregulation:

Key Advantage

This integrated approach creates synergistic effects where multiple metabolic pathways work together, resulting in amplified vitamin C production that exceeds the sum of individual pathway enhancements.

Result: Coordinated metabolic optimization that maximizes both vitamin C synthesis capacity and antioxidant availability at the cellular level.

Self-Reinforcing Metabolic Cycle

Metadichol creates a positive feedback loop through 5 integrated steps:

1. Enhanced Glucose Uptake → GLUT4/GLUT2 provides substrate

2. Improved Insulin Signaling → IRS1/IRS2 supports transcription

3. GULO upregulation → Increases vitamin C synthesis capacity

4. Enhanced Vitamin C Recycling → Maximizes antioxidant availability

5. Reduced Oxidative Stress → Supports continued optimal gene expression

Metadichol’s effectiveness stems from optimizing the complete metabolic infrastructure supporting vitamin C production, creating coordinated enhancement that far exceeds isolated gene upregulation alone.

Figure 3 is a graphical depiction of our results and discussion and the many genes and transcription factors that are involved in GULO expression in species where Gulo is functional.