Submitted:

25 August 2025

Posted:

26 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of the Blueberry Juices

- Moment 0 - the day before fermentation, when the cultures were added (M0),

- Moment 1 - the day when the fermented juices were obtained (M1),

- Moment 2 - 3 days after opening and keeping under refrigeration (M2),

- Moment 3 - 5 days after opening and keeping under refrigeration (M3).

2.2. pH Determination by the Potentiometric Method

2.3. Determination of the Refractive Index

2.4. Determination of Vitamin C by the Iodometric Method

2.5. Antioxidant Activity Determination

2.6. Determination of the Total Polyphenol Content

2.7. Microbiological Determinations

3. Results

3.1. pH Values Variation for the 4 Types of Blueberries Juices

3.2. Refractive Indices Variation for the 4 Types of Blueberries Juices

|

Bluberries juice code/ refractive index |

M0 | M1 | M2 | M3 |

| NPM | 1.3531±0.0002*a**,i*** | 1.3554±0.0002b,j | 1.3553±0.0002b,i | 1.3555±0.0002b,j |

| NP | 1.3542±0.0003a, j | 1.3553±0.0002b,j | 1.3552±0.0002b,i | 1.3551±0.0003b,ij |

| NC | 1.3554±0.0001b, l | 1.3552±0.0001a,ij | 1.3550±0.0002b,i | 1.3546±0.0003a,i |

| NCM | 1.3550±0.0002a, k | 1.3550±0.0002a,i | 1.3549±0.0003a,i | 1.3549±0.0004a,i |

3.3. The Variation of the Ascorbic Acid (AA) Concentration for the 4 Types of Blueberries Juices

|

Bluberries juice code/AA concen- tration, mg % |

M0 | M1 | M2 | M3 |

| NPM | 1.76±0.02*c**, i*** | 1.76±0.02 c, i | 1.32±0.02b, i | 0.88±0.03a, j |

| NP | 1.76±0.02b,i | 1.76±0.02b, i | 1.32±0.02a, i | 1.32±0.02 a. k |

| NCM | 1.76±0.02c,i | 1.32±0.03b, j | 1.32±0.03b, i | 0.44±0.02,a, i |

| NC | 1.76 ±0.02c, i | 1.76 ±0.02c, i | 1.32±0.03b, i | 1.32±0.01b, k |

3.4. Antioxidant Activity Variation for the 4 Types of Blueberries Juices

|

Bluberries juice code/anti- oxidant activity, % |

M0 | M1 | M2 | M3 |

| NPM | 38.55±0.87*c*,* i*** | 34.33±1.10 b,i | 46.23±0.96d, i | 18.37±0.48a, j |

| NP | 38.40±0.92a,i | 51.20±0.49d,k | 48,64±0.69 c, j | 47.74±0.41b, l |

| NCM | 41.41±0.56b,j | 48.64±0.87c,j | 49.39±0.98c, j | 16.71±0.62 a, i |

| NC | 40.88 ±0.90 a,j | 56.77 ±0.68c,l | 51.20±0.63b, k | 40.66±0.58a, k |

3.5. The variation of the polyphenols concentration for the 4 types of blueberries juices

|

Bluberries juice code/poly- phenols in mgEAG/100mL |

M0 | M1 | M2 | M3 |

| NPM | 125.61±1.02* b**, j*** | 127.41±1.18 b, i | 120.91±1.15a, j | 126.85±1.25 b, j |

| NP | 123.83±1.10 a, ij | 274.84±1.41 c, j | 122,72±1.25 a, j | 132.63±1.14 b, k |

| NCM | 123.74±1.31 c, i | 126.07±0.74 d, i | 114.34±1.35 a, i | 120.32±1.51 b, i |

| NC | 129.22 ±0.95 a, k | 275.83 ±1.48 c, j | 135.62±1.23 b, k | 130.74±1.08 a, k |

3.6. The Microbiological Determinations Results of the 4 Types of Blueberries Juices

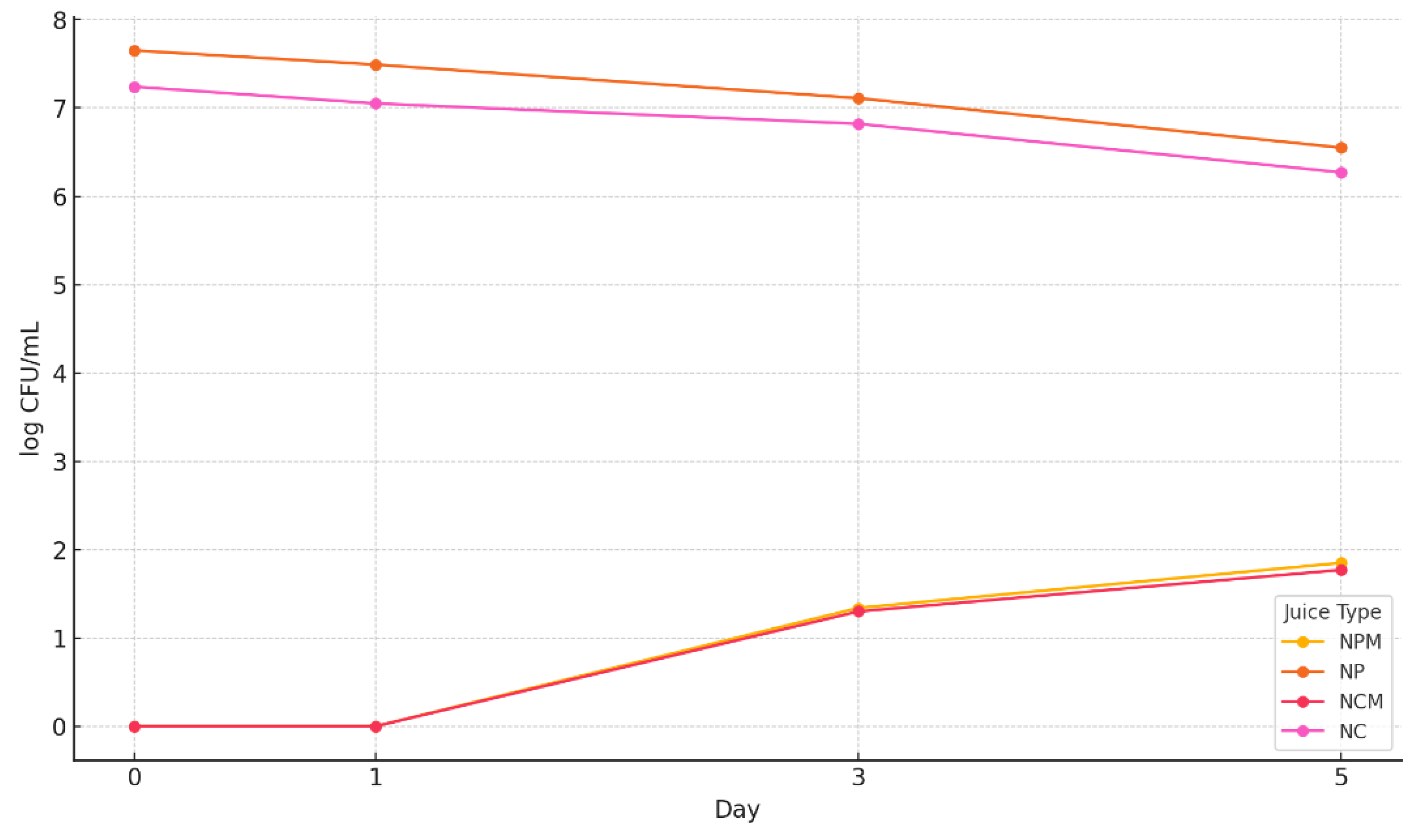

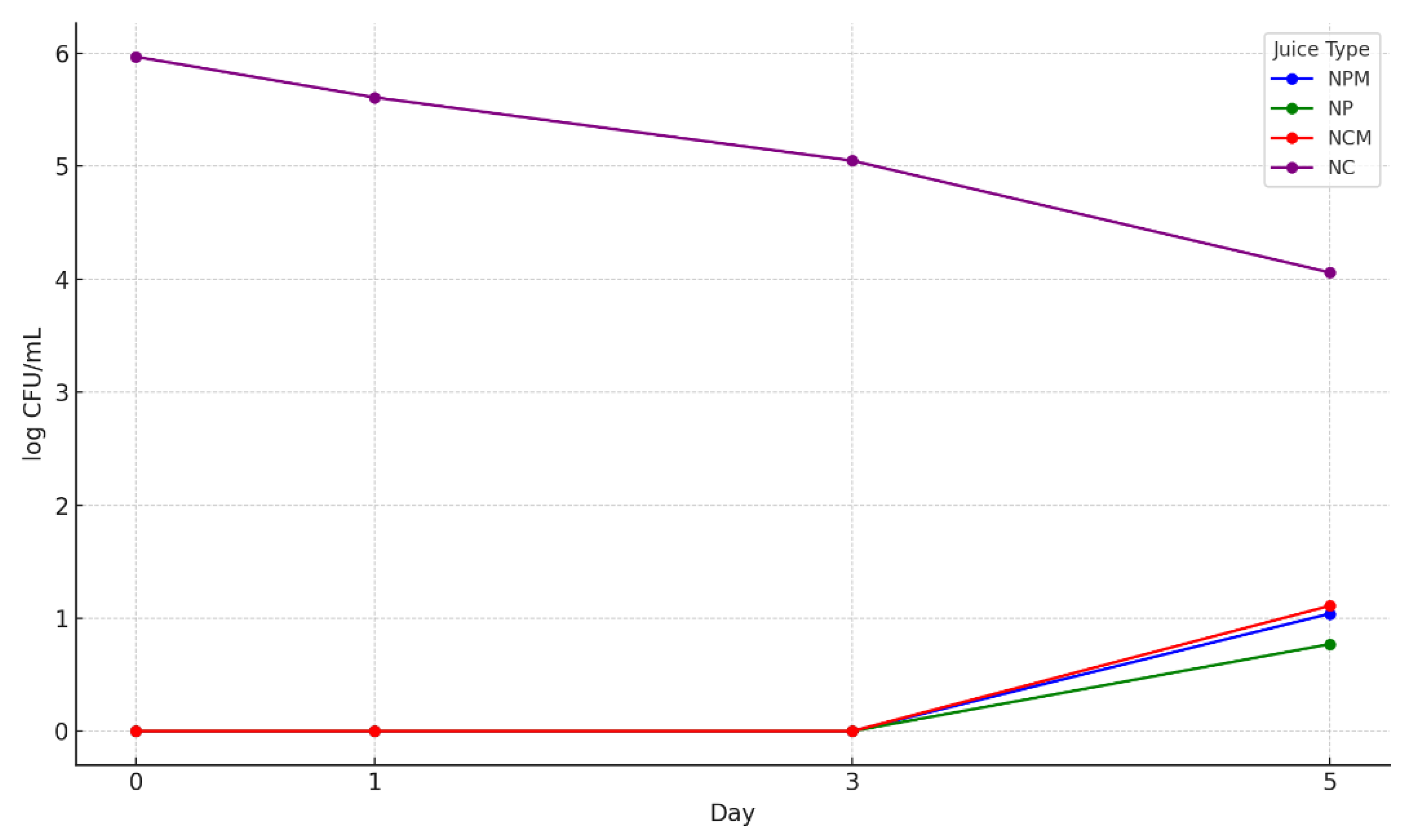

3.7.1. Determination of the Total Number of Aerobic Mesophilic Bacteria

3.7.2. The Total Yeast and Mold Counts

3.7.3. Detection of Staphylococcus sp. and Escherichia coli

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tobar-Bolaños, G.; Casas-Forero, N.; Orellana-Palma, P.; Petzold, G. Blueberry juice: Bioactive compounds, health impact, and concentration technologies—A review. J. Food Sci. 2021, 86, 5062–5077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, W.; Wei, Z.; Yin, B.; Man, C.; Jiang, Y. Enhancement of functional characteristics of blueberry juice fermented by Lactobacillus plantarum. LWT 2021, 139, 110590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Zang, H.; Guo, X.; Li, S.; Xin, X.; Li, Y. A systematic study on composition and antioxidant of 6 varieties of highbush blueberries by 3 soil matrixes in China. Food Chem. 2025, 472, 142974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinwari, K.J.; Rao, P.S. Stability of bioactive compounds in fruit jam and jelly during processing and storage: A review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 75, 181–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavefve, L.; Howard, L.R.; Carbonero, F. Berry polyphenols metabolism and impact on human gut microbiota and health. Food Funct. 2020, 11, 45–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pertuzatti, P.B.; Hermosín-Gutiérrez, I.; Godoy, H.T. Blueberries: Market, Cultivars, Chemical Composition and Antioxidant Capacity. In Blueberries: Harvesting Methods, Antioxidant Properties and Health Effects; Marsh, M., Ed.; Nova Science Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, S.; Costa, E.M.; Veiga, M.; Morais, R.M.; Calhau, C.; Pintado, M. Health promoting properties of blueberry: A review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 60, 181–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, Y.; Tarafdar, A.; Chaurasia, D.; Singh, A.; Bhargava, P.C.; Yang, J.; Li, Z.; Ni, X.; Tian, Y.; Li, H.; et al. Blueberry Fruit Valorization and Valuable Constituents: A Review. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2022, 381, 109890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.Q.; Han, T.Y.; Yang, H.; Lyu, L.F.; Li, W.L.; Wu, W.L. Known and potential health benefits and mechanisms of blueberry anthocyanins: A review. Food Biosci. 2023, 55, 103050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Zhang, A.; Yu, H.; Zeng, Q.; Liu, X. Postharvest application of ultraviolet-A and blue light irradiations boosted the accumulation of acetylated anthocyanins in the blueberry fruit and its potential regulatory mechanisms. Postharvest Biology and Technology. 2025, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Zhang, F.; Chai, Z.; Liu, M.; Battino, M.; Meng, X. Mixed fermentation of blueberry pomace with L. rhamnosus GG and L. plantarum-1: Enhance the active ingredient, antioxidant activity and health-promoting benefits. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2019, 131, 110541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, S.; Viana, S.; Rolo, A.; Palmeira, C.; André, A.; Cavadas, C.; Pintado, M.; Reis, F. Blueberry juice as a nutraceutical approach to prevent prediabetes progression in an animal model: Focus on hepatic steatosis. Eur. J. Public Health 2019, 29, ckz034-011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saud, S.; Xiaojuan, T.; Fahad, S. The Consequences of Fermentation Metabolism on the Qualitative Qualities and Biological Activity of Fermented Fruit and Vegetable Juices. Food Chem. X 2024, 21, 101209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paramithiotis, S.; Das, G.; Shin, H.-S.; Patra, J.K. Fate of Bioactive Compounds during Lactic Acid Fermentation of Fruits and Vegetables. Foods 2022, 11, 733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Küçükgöz, K.; Trząskowska, M. Nondairy probiotic products: Functional foods that require more attention. Nutrients 2022, 14, 753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiou, S.Y.; Sung, J.M.; Huang, P.W.; Lin, S.D. Antioxidant, antidiabetic, and antihypertensive properties of Echinacea purpurea flower extract and caffeic acid derivatives using in vitro models. J. Med. Food 2017, 20, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, X.; Wang, T.; Sun, L.; Qiao, Z.; Pan, H.; Zhong, Y.; Zhuang, Y. Recent advances of fermented fruits: A review on strains, fermentation strategies, and functional activities. Food Chem X 2024, 22, 101482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai W., Tang F., Zhao X., Guo Z., Zhang Z., Dong Y., Shan C. Different lactic acid bacteria strains affecting the flavor profile of fermented jujube juice. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2019, 43, e14095.

- Feng, T.; Cai, W.; Sun, W.; Yu, S.; Cao, J.; Sun, M.; Wang, H.; Yu, C.; Kang, W.; Yao, L. Co-Cultivation effects of Lactobacillus plantarum and Pichia pastoris on the key aroma components and non-volatile metabolites in fermented jujube juice. RSC Adv. 2025, 15, 10653–10662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, H.; Deng, L.; Zhao, M.; Tang, J.; Liu, T.; Zhang, H.; Feng, F. Probiotic-Fermented Blueberry Juice Prevents Obesity and Hyperglycemia in High Fat Diet-Fed Mice in Association with Modulating the Gut Microbiota. Food Funct. 2020, 11, 9192–9207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, J.; Ma, L.; Xu, Y.; Wu, J.; Li, L. Effects of probiotic litchi juice on immunomodulatory function and gut microbiota in mice. Food Res. Int. 2020, 137, 109433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Han, M.; Liang, J.; Zhang, M.; Bai, X.; Yue, T.; Gao, Z. Evaluating the changes in phytochemical composition, hypoglycemic effect, and influence on mice intestinal microbiota of fermented apple juice. Food Res. Int. 2022, 155, 110998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- International Federation of Fruit Juice Producers (IFU). Methods of Analysis; IFU: Zurich, Switzerland, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Varga, C.; Peter, A.; Ambrus, A.; Dunca, I. Practical Biochemistry Exercises. Part II; Risoprint Publishing House: Cluj-Napoca, Romania, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Tongnuanchan, P.; Benjakul, S.; Prodpran, T. Properties and antioxidant activity of fish skin gelatin film incorporated with citrus essential oils. Food Chem. 2012, 134, 1571–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singleton, V.L.; Orthofer, R.; Lamuela-Raventos, R.M. Analysis of total phenols and other oxidation substrates and antioxidants by means of Folin-Ciocalteu reagent. Method Enzymol. 1999, 299, 152–178. [Google Scholar]

- Bunea, A.; Rugină, D.O.; Pintea, A.M.; Sconţa, Z.; Bunea, C.I.; Socaciu, C. Comparative Polyphenolic Content and Antioxidant Activities of Some Wild and Cultivated Blueberries from Romania. Not. Bot. Horti Agrobo. 2011, 39, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desiderio, F.; Szilagyi, S.; Békefi, Z.; Boronkay, G.; Usenik, V.; Milić, B.; Mihali, C.; Giurgiulescu, L. Polyphenolic and fruit colorimetric analysis of Hungarian sour cherry genebank accessions. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Organization for Standardization. Microbiology of the Food Chain—Horizontal Method for the Enumeration of Microorganisms—Part 1: Colony Count at 30 Degrees C by the Pour Plate Technique; ISO 4833-1:2013; ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- International Organization for Standardization. Microbiology of Food and Animal Feeding Stuffs—Horizontal Method for the Enumeration of Yeasts and Moulds—Part 1: Colony Count Technique in Products with Water Activity Greater than 0.95; ISO 21527-1:2008; ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- International Organization for Standardization. Microbiology of the Food Chain—Horizontal Method for the Enumeration of Coagulase-Positive Staphylococci (Staphylococcus aureus and Other Species)—Part 1: Method Using Baird-Parker Agar Medium; ISO 6888-1:2021; ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- International Organization for Standardization. Microbiology of Food and Animal Feeding Stuffs—Horizontal Method for the Detection and Enumeration of Escherichia coli β-Glucuronidase Positive; ISO 16649-2:2007; ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Khouryieh, H.A.; Aramouni, F.M.; Herald, T.J. Physical, Chemical and Sensory Properties of Sugar-Free Jelly. J. Food Qual. 2005, 28, 179–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaunsar, J. S.; Pavuluri, S. R. Stability of bioactive compounds in fruit jam and jelly during processing and storage: A review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 75, 181–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwaw, E.; Ma, Y.; Tchabo, W.; Apaliya, M. T.; Xiao, L.; Li, X. Effect of fermentation parameters and their optimization on the phytochemical properties of lactic-acid-fermented mulberry juice. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2017, 11(3), 1462–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Xiao, G.; Xu, Y.; Yu, Y.; Wu, J.; Zou, B. High hydrostatic pressure and co-fermentation by Lactobacillus rhamnosus and gluconacetobacter xylinus improve flavor of yacon-litchi-longan juice. Foods 2019, 8, 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Presti, I.; D’Orazio, G.; Labra, M.; La Ferla, B.; Mezzasalma, V.; Bizzaro, G.; Giardina, S.; Michelotti, A.; Tursi, F.; Vassallo, M.; Di Gennaro, P. Evaluation of the probiotic properties of new Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium strains and their in vitro effect. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2015, 99, 5613–5626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaprasob, R.; Kerdchoechuen, O.; Laohakunjit, N.; Somboonpanyakul, P. B Vitamins and prebiotic fructooligosaccharides of cashew apple fermented with probiotic strains Lactobacillus spp., Leuconostoc mesenteroides and Bifidobacterium longum. Process Biochem. 2018, 70, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevindik, O.; Guclu, G.; Agirman, B.; Selli, S.; Kadiroglu, P.; Bordiga, M.; Capanoglu, E.; Kelebek, H. Impacts of selected lactic acid bacteria strains on the aroma and bioactive compositions of fermented gilaburu (Viburnum opulus) juices. Food Chem. 2022, 378, 132079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Li, D.; Tian, Q.; Ding, Y.; Jiang, H.; Xin, G.; Cheng, S.; Tang, S.; Jin, C.; Tian, J.; Li, B. The Effect of kiwi berry (Actinidia arguta) on preventing and alleviating loperamide-induced constipation. Food Innov. Adv. 2023, 1, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madeira Junior, J.V.; Teixeira, C.B.; Macedo, G.A. Biotransformation and Bioconversion of Phenolic Compounds Obtainment: An Overview. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2015, 35, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Wang, R.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Sun, X.; Zhang, Q.; Yang, N. Biotransformation of phenolics and metabolites and the change in antioxidant activity in kiwifruit induced by Lactobacillus plantarum fermentation. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2020, 100, 3283–3290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muhialdin, B.J.; Meor Hussin, A.S.; Kadum, H.; Abdul Hamid, A.; Jaafar, A.H. Metabolomic Changes and biological activities during the lacto-fermentation of jackfruit juice using Lactobacillus casei ATCC334. LWT–Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 141, 110940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melini, F.; Melini, V. Impact of fermentation on phenolic compounds and antioxidant capacity of quinoa. Fermentation 2021, 7, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Chen, C.; Ni, D.; Yang, Y.; Tian, J.; Li, Y.; Chen, S.; Ye, X.; Wang, L. Effects of Fermentation on Bioactivity and the Composition of Polyphenols Contained in Polyphenol-Rich Foods: A Review. Foods 2023, 12, 3315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, F.; Wang, L.; Li, S. Enhancement in the physicochemical properties, antioxidant activity, volatile compounds, and non-volatile compounds of watermelon juices through Lactobacillus plantarum JHT78 fermentation. Food Chem. 2023, 420, 136146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Wu, T.; Chu, X.; Tang, S.; Cao, W.; Liang, F.; Fang, Y.; Pan, S.; Xu, X. Fermented blueberry pomace with antioxidant properties improves fecal microbiota community structure and short chain fatty acids production in an in vitro mode. LWT 2020, 125, 109260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Gomez, J.; Varo, M.A.; Merida, J.; Serratosa, M.P. Influence of drying processes on anthocyanin profiles, total phenolic compounds and antioxidant activities of blueberry (Vaccinium corymbosum). LWT–Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 120, 108897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nualkaekul, S.; Charalampopoulos, D. Survival of Lactobacillus plantarum in model solutions and fruit juices. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2011, 146, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plessas, S. Advancements in the use of fermented fruit juices by lactic acid bacteria as functional foods: Prospects and challenges of Lactiplantibacillus (Lpb.) plantarum subsp. plantarum application. Fermentation 2022, 8, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzi, F.; Juan, B.; Espadaler-Mazo, J.; Capellas, M.; Huedo, P. Lactiplantibacillus plantarum KABP051: Stability in fruit juices and production of bioactive compounds during their fermentation. Foods 2024, 13, 3851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.S.; Emon, D.D.; Toma, M.A.; Nupur, A.H.; Karmoker, P.; Iqbal, A.; Aziz, M.G.; Alim, M.A. Recent advances in probiotication of fruit and vegetable juices. J. Adv. Vet. Anim. Res. 2023, 10, 522–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maia, M.S.; Domingos, M.M.; de São José, J.F.B. Viability of probiotic microorganisms and the effect of their addition to fruit and vegetable juices. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandha, J.; Shumoy, H.; Matemu, A.O.; Raes, K. Characterization of fruit juices and effect of pasteurization and storage conditions on their microbial, physicochemical, and nutritional quality. Food Biosci. 2023, 51, 102335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tournas, V.H.; Heeres, J.; Burgess, L. Moulds and yeast in fruit salads and fruit juices. Food Microbiol. 2006, 23, 684–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, L.; Martynenko, A.; Doucette, C.; Hughes, T.; Fillmore, S. Microbial quality and shelf life of blueberry purée developed using cavitation technology. J. Food Sci. 2018, 83, 732–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, P.; Zhou, B.; Zou, H.; Wang, Y.; Liao, X.; Hu, X.; Zhang, Y. High pressure homogenization inactivation of Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus in phosphate buffered saline, milk and apple juice. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2021, 73, 159–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Lavalle, L.; Carrasco, E.; Valero, A. Strategies for microbial decontamination of fresh blueberries and derived products. Foods 2020, 9, 1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lacombe, A.; Wu, V.C.; White, J.; Tadepalli, S.; Andre, E.E. The Antimicrobial properties of the lowbush blueberry (Vaccinium angustifolium) fractional components against foodborne pathogens and the conservation of probiotic Lactobacillus rhamnosus. Food Microbiol. 2012, 30, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Bluberries juice code/pH | M0 | M1 | M2 | M3 |

| NPM | 3.66±0.01*a**, i*** | 3.67±0.02c, i | 3.86±0.02c,j | 3.93±0.03b, j |

| NP | 3.67±0.01 a,i | 3.94±0.02b,j | 3,94±0.03b,k | 3.95±0.02b,j |

| NCM | 3.86±0.02 b,j | 3.67±0.03a, i | 3.64±0.03a,i | 3.65±0.02a, i |

| NC | 3.93 ±0.02 b,k | 3.65 ±0.02a,i | 3.65±0.02a,i | 3.66±0.03a, i |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).