1. Introduction

The decline in physical activity among children and adolescents has emerged as a shared global educational challenge, thereby further underscoring the educational significance of elementary physical education [

1]. Elementary physical education must function not merely as a vehicle for providing physical activity but as a core subject that promotes healthy physical development and holistic growth in children [

2]. Within this process, Fundamental Movement Skills (FMS)—the foundation for participation in all physical activities and sports—are regarded as essential content that should be intensively taught during the primary years [

3]. FMS encompass locomotor, non-locomotor (stability), and object-control (manipulative) skills; children who fail to acquire these skills sufficiently may face constraints in subsequent sport participation and in sustaining lifelong physical activity [

4].

In actual elementary PE classrooms, however, an overreliance on gamification elements aimed at stimulating student interest has led to core content such as FMS being addressed only indirectly or marginalized without formal assessment. Activities that merely borrow superficial game features—such as point allocation or competitive rules—can blur instructional priorities, thereby weakening content-oriented instruction in elementary PE [

5,

6].

To overcome these issues, recent scholarship in physical education and educational technology has highlighted the pedagogical potential of Game-Based Learning (GBL), which is distinct from the mere use of game elements [

7]. GBL can operate as a structured instructional design strategy that scaffolds mastery of core content such as FMS [

8,

9]. Doing so, however, presupposes teacher expertise in instructional design; accordingly, the Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge (TPACK) framework has been emphasized as the theoretical foundation [

10]. TPACK supports teachers in designing instruction that integratively considers technological knowledge (TK), pedagogical knowledge (PK), and content knowledge (CK), thereby enabling both FMS-centered learning and digitally mediated engagement.

Key components of GBL include explicit goal setting, challenge and feedback, intrinsic motivation, provision of a narrative context, and calibrated progression of difficulty. These elements foster learner immersion and sustained participation, offering a structured learning experience that is qualitatively different from piecemeal adoption of game features [

11]. Notably, recent studies underscore emergent narrative—where learners enact roles and co-construct storylines through their actions—as a critical driver of immersion, suggesting strategic integration of storytelling in GBL design [

12].

GBL must be coupled with TPACK because the use of digital devices cannot remain at the level of simple technological adoption; it must be integratively designed in alignment with educational purposes and the instructional context. Educational impact cannot be expected merely by importing game formats; rather, GBL presupposes instructional design in which TK, PK, and CK are organically integrated. TPACK systematizes this integrative process; indeed, Hsu, Liang, and Su [

13] reported that teachers’ TPACK levels affect the effectiveness of game-based instruction. This implies that GBL is not simply tool use but an instructional strategy requiring context-sensitive, integrated design.

Meanwhile, the exponential pace of digital technology (often captured by “Moore’s law”) poses structural challenges to teachers’ agency in instructional design. artificial intelligence (AI) -based game content generation and automated feedback systems suggest that machines may partially substitute for the teacher’s role as curriculum implementer, signaling a critical juncture for rearticulating the professional expertise of elementary teachers [

14].

However, when TPACK-based GBL is overly organized as a means to an end, the essential attributes of play—voluntariness, fictiveness, rule-boundedness, and purposelessness—may be compromised, with “play” at risk of being instrumentalized into “work” [

15,

16]. To preserve and amplify the ludic qualities of GBL, a theoretical lens on play typologies is required. Accordingly, this study adopts Caillois’s [

16] four categories of play—competition (Agon), chance (Alea), simulation/role-play (Mimicry), and vertigo (Ilinx)—to explore lesson-design models that can be systematically linked with FMS.

Prior literature has examined GBL and TPACK, or FMS-focused instruction, largely in isolation. Casey et al. [

17] reported that GBL heightens engagement in elementary PE and positively affects the affective domain, whereas Trust et al. [

18] argued that TPACK-based instructional design can enhance teachers’ professional practice. Camacho-Sánchez et al. [

7] further suggested that GBL and gamification can operate complementarily, with features such as points, leveling, and quests serving as levers for sustained participation. Nevertheless, most existing studies privilege one among GBL, TPACK, or FMS, leaving integrated approaches underdeveloped. Discussions of the shifting role of PE teachers under technological change remain limited, and theoretical attempts to structure FMS-based lesson design through Caillois’s play theory are similarly scarce.

Against this backdrop, the present study undertakes a framework-design inquiry that integrates GBL, TPACK, Caillois’s play theory, and FMS into an actionable instructional framework and examines it against criteria of theoretical, technological, and curricular validity. Specifically, we (a) analyze how the TPACK components (CK, PK, TK) operate in an integrated manner within FMS-centered GBL lessons; (b) explore linkages between FMS domains (locomotor, non-locomotor, manipulative) and Caillois’s play types (Agon, Alea, Mimicry, Ilinx); and (c) synthesize—via multi-perspectival reviews with teachers and expert groups—the practical feasibility of classroom implementation and the technological conditions required for realization.

Employing the cyclical logic of Design-Based Research (DBR), this study develops a practice-oriented framework and proposes a theory–practice integration model that reasserts teacher-led design agency in GBL while securing the educational legitimacy of digitally mediated PE [

19]. The proposed framework offers actionable criteria for curriculum-centered design of digital PE lessons and is expected to provide a theoretical foundation for future research on game-based physical education.

2. Theoretical Background

This section discusses four core constructs that constitute the study’s theoretical foundation: FMS, GBL, the TPACK framework, and Caillois’s typology of play. It also examines the integrative potential among these constructs and the limitations identified in prior research to establish the theoretical warrant for the proposed GBL–TPACK–play-theory instructional design framework.

2.1. Fundamental Movement Skills (FMS) and Physical Education

FMS are foundational competencies for children’s physical activity and play a pivotal role in shaping subsequent sport participation and lifelong physical activity capacity [

3,

20]. FMS are typically classified into three domains—locomotor, stability (non-locomotor), and object control (manipulative) skills [

21]—each of which requires systematic instruction aligned with developmental stages.

Locomotor skills involve spatial displacement (e.g., running, jumping), stability skills entail control of static or axial positions (e.g., balancing, turning), and object-control skills encompass handling implements or projectiles (e.g., throwing, catching) [

4]. Mastery of FMS undergirds not only physical development but also holistic outcomes such as self-efficacy, social competence, and self-regulation [

2].

Notably, insufficient FMS proficiency during the primary years may lead to later activity avoidance and diminished confidence [

22]. Accordingly, national curricula across countries identify FMS as core content and structure teaching progressions by grade bands. For example, SHAPE America [

23] recommends iterative, cumulative instruction of all three skill groups across K–5, while the national curricula of England and Australia similarly organize early-stage learning around FMS [

24,

25]. This international orientation suggests that FMS instruction should be designed as a developmentally sequenced curriculum rather than as one-off activities [

26].

2.2. Game-Based Learning (GBL)

GBL is an instructional strategy that mobilizes core game elements—clear rules, challenge, feedback, calibrated difficulty, cooperation, and narrative structure—to enhance learner immersion and self-directed engagement [

27,

28]. Unlike gamification as a mere motivational overlay, GBL presupposes structured lesson design tightly coupled with learning objectives [

29].

The educational efficacy of GBL has been evidenced across cognitive immersion, affective engagement, and self-regulated learning [

12,

30,

31]. Iterative feedback and narrative-centric structures strengthen participation, fostering identification and self-monitoring within agentic learning contexts.

In physical education, GBL can effectively reinforce the affective domain by coupling physical activity with game architectures; real-time feedback and challenge-based tasks may heighten learning immersion [

17]. Effective enactment, however, relies on teacher expertise in instructional design and requires a context-sensitive approach that considers learners’ prior knowledge, motivation, and self-regulatory capacity [

32].

2.3. The TPACK Framework: An Integrative Structure for Technology–Pedagogy–Content

TPACK is a framework of teacher professional knowledge that supports the integrated use of TK, PK, and CK for coherent lesson design, emphasizing practical alignment in digital instruction [

10]. It rests on the premise that technology functions not as an isolated tool but as an element that yields impact when coherently coupled with content and pedagogical strategy.

CK concerns understanding of core disciplinary concepts [

33]; PK encompasses knowledge of learning theories and instructional strategies [

34]; TK refers to the ability to interpret and deploy digital tools for educational purposes. In PE contexts, TK may include the integration of video analysis, augmented reality (AR) content, and sensor-based feedback systems [

35].

These three forms of knowledge do not operate in isolation; rather, they interact and integrate to enhance lesson coherence, engagement, and effectiveness [

36]. Trust et al. [

18] highlighted that TPACK-informed design can elevate teachers’ self-efficacy and refine their pedagogical discrimination regarding digital technologies.

Nevertheless, concrete design guidelines for the technological dimension of TPACK remain underdeveloped in PE practice. In particular, the effective integration of emerging technologies (e.g., games, AR) requires systematic capacity-building to strengthen teachers’ TPACK [

37].

2.4. Caillois’s Play Typology and Its Potential for Lesson Structuring

Caillois [

16] classifies play into four types: competition (Agon), chance (Alea), simulation/role-play (Mimicry), and vertigo (Ilinx). This typology theorizes play according to structure, rules, roles, and outcome mechanisms and can serve as a meaningful design lens in PE.

Agon denotes rule-governed fair competition, aligning closely with locomotor and manipulative FMS; Alea privileges stochastic outcomes, creating conditions for equitable participation among learners of diverse ability levels; Mimicry promotes immersion and creativity through role-play and simulation, suiting lower-grade expressive activities; Ilinx entails sensory disruption (e.g., spinning, balance loss), which may support sensory integration capacities [

38].

Caillois’s theory is structurally compatible with FMS and offers a theoretical foundation for lesson designs that integrate cognitive, affective, and physical development [

39]. While maintaining the productive tension between rule-boundedness and spontaneity, structured play designs can further catalyze immersion and participation [

40]. The typology also coheres with core GBL elements (immersion, feedback, challenge), enabling a pedagogically grounded reinterpretation of play.

Moreover, across cultural philosophy, sociology, and pedagogy,

play–game–sport has been theorized as a continuum [41-44]. Accordingly, ‘game’ designs for PE should be anchored in play theory so that rules, roles, chance, and sensory stimulation are aligned with curricular aims [

45]. In this study, we therefore use play theory as the conceptual anchor for FMS-centered GBL.

2.5. Integrative Potential of the Four Constructs and Limitations in Prior Studies

Although prior studies have examined GBL, TPACK, FMS, and Caillois’s play theory, they have typically done so in isolation; instances of integrating all four into a coherent instructional framework are rare [

46]. Research that applies GBL–TPACK to PE remains emergent, and linkages to FMS or to play theory are even more limited. Research that applies GBL–TPACK to PE remains emergent, and linkages to FMS or to play theory are even more limited [

7,

35,

46].

Moreover, the accelerating pace of technological change risks attenuating teachers’ design agency and curricular interpretive capacity, creating structural challenges for high-quality GBL enactment [

37,

47]. Consequently, teachers are called to exercise compound professional roles—not merely as implementers but as content designers, feedback orchestrators, and data interpreters [

48]. Within this shift, TK should be redefined beyond tool operation to include the design–orchestration–evaluation of digital game-based learning grounded in play theory [

37,

47,

48].

In response, this study seeks to secure both the theoretical legitimacy and practical feasibility of PE lessons by proposing a teaching–learning structure that integrates GBL, TPACK, FMS, and Caillois’s theory. The framework aims to articulate a direction for designing digitally mediated elementary PE that is curriculum-centered and pedagogically robust. Furthermore, the framework operates as a design principle that articulates actionable pathways to SDGs 3, 4, and 10 across lesson-, school-, and policy-levels.

3. Materials and Methods

This study describes the methodology of a practice-oriented qualitative inquiry conducted to explore instructional design principles that integrate FMS, Caillois’s play theory, and a GBL–TPACK framework. The research design centered on analyses of authentic classroom cases, employing the cyclical logic of Design-Based Research (DBR) to interpret meanings emerging during implementation and to examine feasibility. Through this approach, we sought to derive practical implications for content-oriented lesson design.

3.1. Research Design

This practice-oriented qualitative study investigates the theoretical validity and classroom feasibility of GBL lesson design centered on FMS. We integrated Caillois’s play typology with the TPACK framework to develop an instructional design framework and applied it to elementary physical education lessons, adopting the iterative, exploratory cycles of DBR. DBR is considered well-suited for deriving actionable teaching–learning principles by organically coupling theory and practice [

49,

50].

3.2. Participants

Six experts participated in the study: two elementary teachers with extensive experience in PE and GBL lessons, two curriculum specialists in elementary physical education, and two technology experts with experience in edtech-based game development. Teachers were selected based on documented experience designing and implementing FMS-based and digitally integrated lessons; curriculum experts held doctoral degrees in physical education and had experience in curriculum research and development; technology experts (a game designer and a software engineer) possessed experience designing game content and systems deployable in school settings. Consistent with qualitative research, purposive sampling was used to ensure contextual fit [

51].

Table 1.

Participant characteristics.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics.

| Role |

Name (Pseudonym) |

Age |

Experience |

Notes |

| Practitioner (Teacher) |

Robert |

41 |

15 years as elementary teacher |

Designed and implemented elementary PE lessons |

| James |

38 |

12 years as elementary teacher |

Designed and implemented elementary PE lessons |

| Curriculum Specialist |

Smith |

43 |

PhD (Physical Education) |

Research and development in PE curriculum |

| Micheal |

42 |

PhD (Physical Education) |

Research and development in PE curriculum |

| Technology Expert |

Wang |

58 |

CEO, digital physical-activity game company |

Edtech-based content development experience |

| Satya |

55 |

30+ years in educational content development |

School-oriented game content development |

3.3. Data Collection

Data were collected through three channels. First, we gathered practitioner artifacts from teacher participants, including implemented lesson plans, photos and videos of classroom activities, and reflective journals. These materials served as practice-based evidence of how the GBL–TPACK framework was enacted in situ.

Second, we conducted semi-structured interviews to examine theoretical coherence and practical applicability. Interviews were tailored to each expertise domain (teachers, curriculum specialists, technology experts), conducted individually, and held twice per participant (~60 minutes each session).

Teacher interviews focused on the strategic effects of the GBL–TPACK framework in classroom practice; on the integration of TPACK components (CK = FMS content, PK = pedagogy informed by play theory, TK = digital technologies); and on the influence of Caillois’s typology on learners’ immersion and participation. We also explored distinctions from conventional gamification, perceptions of technology acceptance, and sustainability of implementation.

Curriculum-expert interviews assessed the alignment of framework components with achievement standards and disciplinary competencies in the elementary PE curriculum, as well as the educational appropriateness of integrating FMS, play theory, and digital technologies.

Technology-expert interviews addressed the technical feasibility of the GBL lesson architecture, the digital enactment of curricular structures, and the applicability and limitations of AI-based feedback systems and sensor-based motion recognition.

All interviews were audio-recorded with prior informed consent, transcribed verbatim, and used as qualitative data. Research ethics were upheld by ensuring anonymity and strictly adhering to voluntary participation.

3.4. Data Analysis

We employed thematic analysis in tandem with theoretical coding. After iterative readings of interview transcripts and field artifacts to identify latent themes, we systematically coded the data by mapping to the three GBL–TPACK domains (TK, PK, CK) and to Caillois’s play types (Agon, Alea, Mimicry, Ilinx). The analytic sequence comprised: (1) familiarization, (2) initial code generation, (3) theme development, (4) theme naming and refinement, and (5) reporting. Cross-case comparisons across participant types yielded implications for design coherence, feasibility, and technical realizability.

To support triangulation [

52], we cross-checked multiple sources—including lesson plans, interview data, and reflective journals. Throughout analysis, ATLAS.ti was used to systematically categorize and visualize coded segments, thereby grounding interpretations in the data.2.5. Data Analysis

3.5. Limitations and Trustworthiness

As a qualitative, case-centered inquiry, the study does not aim for statistical generalization; the small, expert sample and depth-oriented analysis may introduce a degree of subjectivity in interpretation. The researcher’s participant–observer position may also pose risks to neutrality. Nevertheless, we sought to enhance transferability and interpretive trustworthiness through multi-source data collection, theoretical validation, participant diversification, and systematic analytic procedures.

Trustworthiness was ensured with reference to Lincoln and Guba’s [

53] four criteria—credibility, dependability, transferability, and confirmability. Credibility was addressed through systematic data collection and analysis; dependability through cross-source analyses, member checking, and expert feedback; transferability by providing thick description of participants’ instructional contexts and environments; and confirmability by minimizing researcher bias and making analytic warrants explicit. Dependability was strengthened via an audit trail (decision logs and codebook versioning), and confirmability through reflexive memos and, where applicable, external audit. The study was conducted following approval by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Korea National University of Education (Approval No.: KNUE-202508-SB-0578-01).

4. Results and Discussion

This section presents an integrated analysis of TPACK and Caillois’s play theory within FMS-centered GBL lesson design and, drawing on authentic lesson implementations and expert interviews, discusses the principal findings and implications. The discussion is organized around four subthemes.

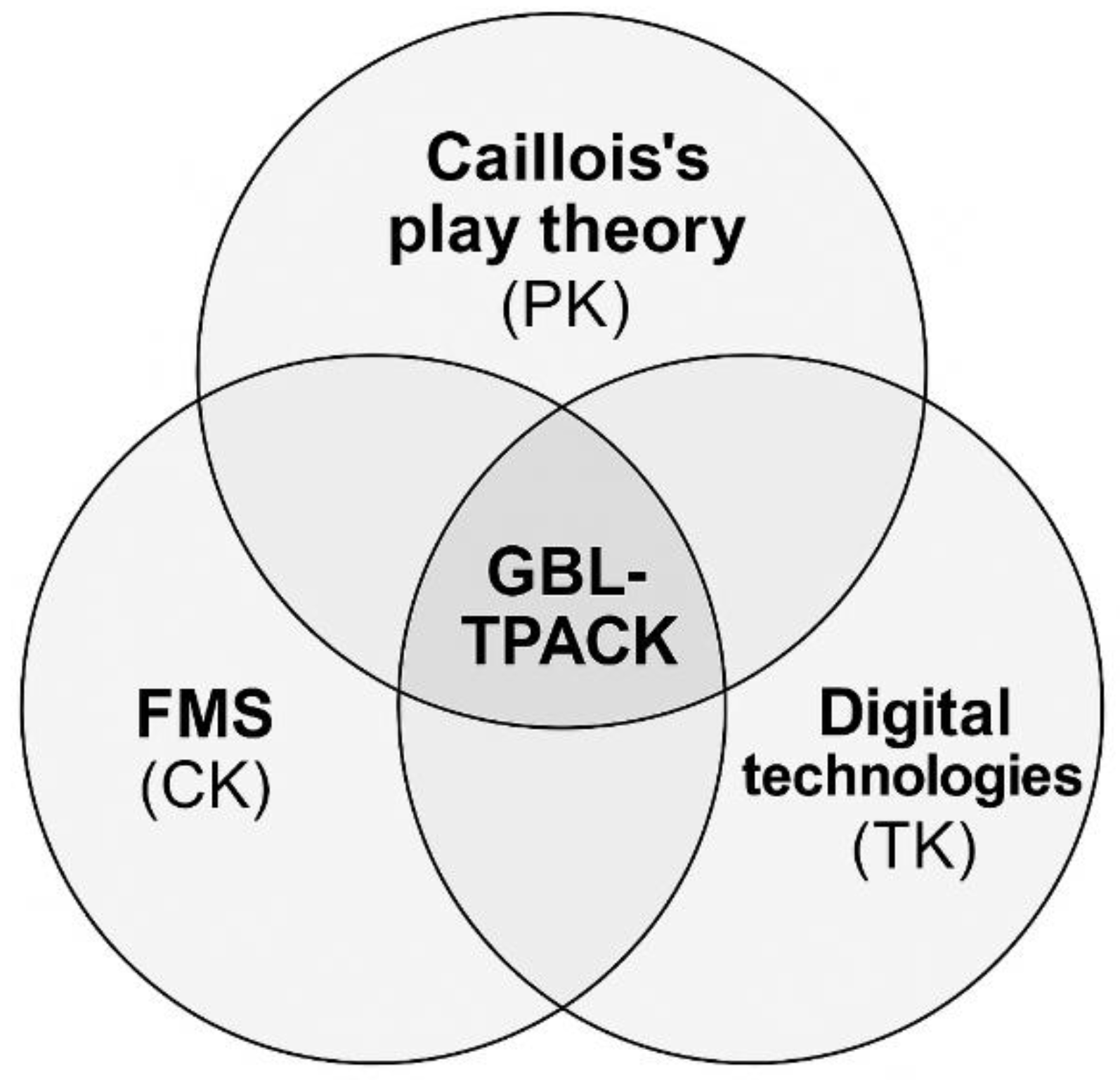

4.1. Components of the GBL–TPACK Framework and Their Linkage to Lesson Design

The TPACK framework [

10] conceptualizes teachers’ instructional design expertise as an interaction among TK, CK, and PK, thereby providing an integrated lens for judging the essential value of curricular content, the suitability of instructional strategies, and the appropriateness of technology use. Although TPACK originated as a general theory for technology-enhanced education, its application to physical education requires interpretations that reflect subject-specific characteristics, such as spatial use and the embodied nature of activity [

54,

55]. In this study, CK was operationalized as FMS (locomotor, stability, and object control), PK as Caillois’s play theory, and TK as digital game technologies; their integration served as the core framework for GBL lesson design.

Whereas elementary PE has traditionally emphasized PCK (Pedagogical Content Knowledge), the current context—in which digital technologies reshape lesson structures—renders TPACK indispensable. Instruction through digital games must move beyond mere tool use toward

technology integration, elevating digital literacy from device manipulation to an essential capability for interpreting learner data and reaffirming teacher decision-making authority [

37,

47].

GBL is not the simple use of games; rather, it is an approach that orchestrates core game structures (rules, feedback, challenge, narrative, cooperation, etc.) to create learner-centered, immersive experiences aligned with educational contexts. It is defined not as a strategy for interest alone but as an instructional design that, through psychologically grounded elements such as intrinsic motivation, iterative feedback, and challenge structures, promotes cognitive and affective learning [

8,

30].

By contrast,

gamification is a motivational strategy that employs surface-level game elements—points, badges, leaderboards. Because GBL embodies an internally coherent design anchored to learning goals and assessment structures, it is conceptually distinct from gamification [

56,

57]. Thus, the shift from gamification to genuine game-based learning in PE reflects the need for technology-integrated instruction.

For example, Teacher James leveraged a virtual reality (VR)-supported jumping game to strengthen locomotor skills while linking in-game scoring and real-time feedback to classroom assessment tools. Teacher Robert invited students to adjust game rules themselves to calibrate task difficulty and deepen immersion. Both shared the view that “what the game is designed to teach matters more than the technology itself.”

Such an instructional structure—integrating GBL, TPACK, FMS, and play theory—remains underexplored domestically and internationally [

46]; this study offers an early attempt to do so.

Table 2 visualizes how each TPACK component (CK, PK, TK) combines with GBL to yield practicable lesson structures, thereby illustrating the framework’s feasibility in situ.

This configuration can be visualized schematically in

Figure 1, which depicts at a glance the interactions among GBL–TPACK elements.

To concretize classroom feasibility, consider a sample lesson. Rather than using off-the-shelf VR content as is, the teacher redesigns it as GBL by aligning the activity with the achievement standards and by reconfiguring key game elements—rules, challenges, feedback, difficulty adjustment, collaboration, and narrative structure. For the Grade 3 achievement standard on “directional changes in running” within the “Foundations of Fundamental Movements,” students participate in team-based VR relay games in the school VR lab. The activity targets locomotor FMS through an Agon-type (competitive) play format and, via the VR platform, builds an immersive, collaborative environment. With in-game scoreboards, real-time feedback, and team strategy formation, the lesson exemplifies GBL by integrating achievement standards, game structures, and assessment components—moving beyond mere technology use. Technology expert Satya highlighted the system’s scalability through interoperability among diverse sensors and devices.

To enact such integration, teachers must simultaneously possess understanding of the curriculum (CK), the capacity to orchestrate play-based strategies (PK), and the ability to adapt digital technologies to pedagogical purposes (TK). When games are organically linked to learning objectives, methods, and assessment, GBL operates as a strategy that enhances educational effectiveness [

17,

36]. Furthermore, when curriculum-aligned game content is predeveloped, instruction can be delivered more efficiently, teacher preparation burdens can be reduced, and the reliability and validity of assessment can be strengthened. Operationally, the design is monitored via retention/attendance, moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA) minutes, health-literacy behaviors (self-monitoring/decision-making), accessibility/equity metrics (gender, disability, device access), teacher workload, and maintenance cost/uptime, thereby rendering SDG alignment actionable.

4.2. An Analysis of Alignment Between Caillois’s Play Theory and FMS

Caillois [

16] distinguishes four types of play: Agon, Alea, Mimicry, and Ilinx. We examined how these categories can be connected to FMS instruction. Agon integrates readily with locomotor and object-control skills (e.g., running, jumping, throwing) to structure competition-based games. Alea introduces probabilistic elements (e.g., dice, roulette), supplying unpredictability that can heighten immersion. Mimicry links expressive movement with stability skills through role-play or animal-movement imitation. Ilinx induces immersive sensory stimulation (e.g., spinning, balancing, jumping) and can be coupled with composite FMS tasks.

Crucially, Caillois’s framework situates play not as mere entertainment but as a cultural structure reflecting embodiment, affect, and role enactment, thereby offering educational extensibility [

38]. This provides a foundation for interpreting the affective functions of play, social interaction, and role learning in PE.

A developmental sequence from play → games → sport should be considered across schooling. Early childhood and lower elementary grades emphasize play; middle elementary grades emphasize games; and secondary and adult stages center on sport. In parallel, Caillois’s categories should tend to progress from Mimicry/Ilinx toward Agon/Alea. FMS content should likewise be sequenced from basic skill mastery (lower grades), to integration of composite skills (middle grades), to applied and tactical skills (upper grades), serving as a bridge to secondary-level sport techniques.

In practice, Teacher Robert combined stability skills with creative expression through a Mimicry-based “animal movement game,” while Teacher James employed a technology-enhanced Ilinx-based “roller-coaster game” to train balance alongside object-control skills. Both observed that “play functions as a mechanism for skill acquisition,” reporting that Caillois’s theory was a useful tool for specifying diverse manifestations of FMS in lesson design. Robert further noted that play-centered design bolstered students’ social interaction and self-efficacy. Such approaches suggest that play contributes positively not only to skill learning but also to affective stability, self-efficacy, and role learning [58-60]. Teachers emphasized meaningful effects of play-based lessons on emotion regulation, sustained participation, and peer cooperation, aligning with a broader, holistic interpretation of PE.

Table 3 structures how each of Caillois’s four types can be associated with particular FMS skills, providing concrete guidance for selecting play elements most closely tied to specific physical functions. However,

Table 3 is an illustrative (heuristic) alignment table for lesson design and should be adapted in practice with due consideration of learner characteristics, context, and safety.

Table 4 integrates grade-band developmental characteristics, FMS skill levels, and corresponding Caillois play types to inform curriculum-level planning. The following grade-band alignment is likewise presented as a design example grounded in curriculum interpretation and developmental characteristics, and it may be modified according to context, available resources, and learner proficiency levels.

In applying play types, curriculum expert Smith recommended explicitly aligning each play type’s essence with the essential characteristics of movement and expression (e.g., activity planning, expressive composition). Micheal advised designing for physical authenticity first—so that embodiment is not diluted—and then layering digital elements. These constitute concrete design guidelines for play-centered GBL.

4.3. Feasibility and Limitations of GBL–TPACK Lessons in Elementary PE: Perspectives of Teachers, Curriculum Experts, and Technologists

To obtain a broader understanding of design and implementation feasibility, we solicited input from two elementary teachers, two curriculum experts, and two technology experts. Their perspectives grounded our analysis of the framework’s affordances and constraints in authentic school settings.

First, teachers reported that GBL–TPACK lessons heightened student immersion and participation and promoted self-regulation and social interaction. Teacher James emphasized that “digital game–based lessons are more preparation-efficient than traditional lessons and elicit more active student participation,” while Teacher Robert highlighted contributions to social interaction and self-efficacy. These observations accord with findings that GBL fosters self-regulation and affective engagement [

8,

30].

Second, teachers identified potential technical issues and operational constraints. They noted that “technical glitches can disrupt lesson flow and reduce immersion,” underscoring the need for technical support and structured professional development. They also argued that digital use must be conceived holistically—design–implementation–assessment—consistent with Ertmer & Ottenbreit-Leftwich [

37]. Professional learning communities, as suggested by Trust et al. [

18], provide further support for capacity building and support structures.

Third, curriculum experts stressed clear linkages between achievement standards and play-theoretic elements. Smith noted the need to align each play type with FMS so that the essential characteristics of the movement and expression domains are preserved. Micheal advocated a staged approach: design lessons around physical authenticity first, then add digital features—an approach consonant with Atkinson’s [

38] view of play as a cultural structure integrating body, affect, and social norms, and with Martínková & Parry’s [

61] account of play’s functions in socialization, affective expression, and norm internalization.

Fourth, technology experts discussed technical prerequisites and scalability. Wang pointed to practical constraints (costs; school network upgrades) when introducing advanced technologies, while Satya highlighted the need to increase system scalability and interoperability across sensors and devices. They emphasized recognizing technical limits and addressing them incrementally so that digital tools integrate organically with learning goals, echoing Williamson & Eynon’s [

14] analysis of technology’s impact on PE teaching environments and teacher roles.

Collectively, these perspectives substantiate the practical value of structuring TPACK [

10] and FMS priorities [

3,

4] within authentic elementary PE contexts. They are also consistent with Molina’s account that play in PE spans physical, affective, and social dimensions [

58], and with Rillo-Albert et al. [

60], who report socio-emotional benefits of play-based PE beyond skill acquisition. In sum, despite acknowledging technical and operational constraints, the proposed GBL–TPACK framework demonstrates validity as a forward-looking instructional strategy that can boost student immersion and increase design flexibility—supporting integrated attainment of physical, affective, and social learning goals in elementary PE.

4.4. Teacher Capacities and Policy Implications for Enhancing the Quality of Game-Based Instruction

The effectiveness of game-based PE does not hinge solely on the presence of games or digital technologies. Lesson quality varies markedly with teachers’ design capacity, understanding of play theory, and digital literacy. Participating teachers consistently emphasized that clear educational intents—what, why, and how to teach—and careful design of game structures matter more than the devices themselves.

TPACK-based expertise emerges as critical, requiring integrated design capability across TK–CK–PK rather than mere technical proficiency. For PE teachers, it is additionally essential to understand Caillois’s play theory and to link different play types appropriately with FMS. Beyond Agon-centered competition, teachers must be able to combine Mimicry, Alea, and Ilinx in ways that fit students’ developmental levels and lesson objectives. Molina [

58] identifies play as a key mechanism for affective socialization in PE, showing that teachers’ capacity to design play structures and to regulate emotions significantly shapes students’ affective security and positive self-efficacy.

Caillois [

16] also frames play as a cultural tool tied to socialization, emotion regulation, and norm acquisition; this is consonant with Martínková & Parry’s [

61] phenomenological account of play as socially meaningful praxis in PE. In ilinx-type (vertigo) play, design work that deliberately alternates sensory disequilibrium and re-equilibration can scaffold adaptation to controlled uncertainty [62-64]. PE-specific evidence further shows socio-emotional benefits of play-based lessons beyond skill acquisition—e.g., conflict reduction and improved peer cooperation [

60]—while school-wide social and emotional learning (SEL) ethnography reports gains in peer relations and emotional stability [

65]. Thus, teachers’ competence in designing play structures links not only to instructional goal attainment but also to students’ holistic development.

Concurrently, advances in AI are transforming instructional design and assessment. In PE, AI-enabled motion analytics, personalized feedback systems, and performance-prediction models recast teachers as designers, facilitators, and analysts [

18,

66]. In GBL, AI can assist by auto-generating game structures, adapting difficulty, and providing history-based feedback—shifting required competencies toward next-generation digital literacies that include AI literacy, data-informed lesson analytics, and ethical judgment [

10]. Human-centered approaches, such as Caillois’s play theory, can serve as counterweights to potential side effects of technology integration (e.g., over-immersion, affective detachment), maintaining educational balance [

61].

Such capacities, however, are not cultivated through one-off workshops. Trust et al. [

18] emphasize sustained, practice-centered professional development via professional learning communities (PLCs). Stable implementation of game-based instruction therefore requires collaborative environments in which teachers jointly reflect on classroom problems and iteratively redesign lessons, supported by regional and national professional development (PD) systems. PD should reflect a developmental sequence—play-centered for Grades 1–2, game-centered for Grades 3–4, and sport-transition–centered for Grades 5–6—so that FMS objectives and play-theory applications are carried forward coherently. Beyond technical skill, PD must develop integrated expertise in game-structure design, interpretation of play typologies, and strategies that connect instruction and assessment.

Policy change is likewise necessary. Rather than limiting support to device provisioning, systems should include digitalization of instructional resources, platform-based sharing infrastructures, and development of teacher-facing design and feedback tools. Curriculum–instruction–assessment resources provided as integrated packages will enable teachers to design and enact technology–play–content integration in real classrooms. To reduce regional disparities, digitalization of FMS-centered lesson content and development of standardized materials are also vital.

Ultimately, improving the quality of game-based PE requires integrated enhancement of teachers’ design expertise, theoretical understanding of play and game structures, and digital literacies—objectives unlikely to be realized without long-term PD strategies and policy support. Effective digital transformation of elementary PE will require multi-level collaboration among teachers, researchers, and policymakers to co-design future-oriented PE models in which technology, play, and content are meaningfully integrated.

5. Conclusion and Recommendations

This study explored the instructional principles of GBL centered on FMS in elementary physical education. To this end, we constructed a framework that integrates TPACK with Caillois’s play theory and analyzed its theoretical coherence and classroom feasibility through authentic lesson cases and semi-structured interviews with elementary teachers. This section summarizes the main findings and presents theoretical and practical implications, limitations, and directions for future research.

FMS are emphasized as foundational capacities for physical activity and are regarded as basic skills required for diverse sports and everyday movement [

3]. Yet in recent elementary PE practice, classes that borrow only the

form of games—i.e., gamification—are frequently implemented, rendering FMS instruction indirect or peripheral. This tendency weakens the essential purposes of PE and is linked to insufficient professional capacity in instructional design. To address these issues, the present study argued for establishing the theoretical warrant and feasibility of GBL and for structuring it as a set of principles for instructional design.

Accordingly, we operationalized TPACK as a framework of teacher professional knowledge, assigning FMS to CK, Caillois’s play theory to PK, and digital game technologies to TK, thereby building a GBL–TPACK framework. Notably, Caillois’s [

16] four play types—Agon (competition), Alea (chance), Mimicry (role-play), and Ilinx (vertigo)—can be meaningfully connected with locomotor, stability (non-locomotor), and object-control skills, offering theoretically grounded and practicable guidance for lesson design in elementary PE.

The findings were threefold. First, the GBL–TPACK framework effectively systematized lesson design by organically integrating teachers’ CK, PK, and TK. Second, Caillois’s play theory provided not merely entertainment value but a pedagogical base that can be integrated with lesson objectives and assessment elements. Third, teachers and experts judged that the framework enhances classroom feasibility and positively affects students’ active participation and self-regulation.

Teachers consistently reported that GBL-based design—relative to traditional, repetition-centered instruction—promoted social interaction and immersion. In particular, activities employing Agon and Alea were viewed as effective not only for motor skill mastery but also for fostering cooperation and social interaction, while the integration of digital technologies played an important role in heightening self-regulation and immersive experiences. These observations align with prior evidence on the educational effectiveness of GBL [

8,

30].

Taken together, the findings indicate that the proposed GBL–TPACK framework has both theoretical validity and practical feasibility as a future-oriented instructional approach for elementary physical education. By moving beyond PCK, the study legitimizes a TPACK-based approach that integrates digital technologies within curricular contexts. Moreover, by linking Caillois’s play theory to FMS, it clarifies the developmental sequencing across the play–game–sport continuum and specifies grade-band design logics aligned with curricular goals, thereby enhancing theoretical extensibility. In sum, the integrated GBL–TPACK–FMS–play framework offers design guidance for sustainable digital physical education, meeting core requirements—long-term participation, health literacy, equity, and scalability/maintainability—while advancing the educational realization of SDGs 3, 4, and 10.

Practically, the study underscores the need to enhance elementary PE teachers’ professional competencies and to develop sustained teacher professional development programs. Systematic and durable strategies are required to integratively cultivate teachers’ instructional design capacity, understanding of play theory, and digital literacy [

18]—efforts that are unlikely to succeed without policy-level support from national and regional education authorities. With the introduction of state-of-the-art digital tools, including AI, teachers must move beyond technical fluency to acquire next-generation digital literacies encompassing data-informed lesson analytics and ethical judgment [

66].

This qualitative, case-centered study has limitations, including a small sample and a participant group inclined toward technology, which constrain generalizability. Moreover, schools with limited technological access may face barriers to implementing the framework.

Future studies should apply the GBL–TPACK–play-theory design across grades and contexts to test its validity and should employ quantitative analyses to examine impacts on physical activity competence, lesson satisfaction, and self-regulation. International comparative or cross-cultural research is also needed to assess the framework’s generalizability and contextual fit.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Korea National University of Education (KNUE IRB; protocol code KNUE-202508-SB-0578-01.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and received an exemption from ethical review by the Institutional Review Board of Korea National University of Education.

Informed Consent Statement

All participants and their legal guardians provided written informed consent prior to participation in the study. Written informed consent was also obtained for the publication of anonymized data.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to restrictions related to personal information protection.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the participating teachers for their time, insight, and commitment to this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Uddin, R.; Khan, A.; Islam, M.T.; Tremblay, M.S.; Khan, S.R. Physical Education Class Participation Is Associated with Physical Activity among Adolescents in 65 Countries. Scientific Reports 2020, 10, 22128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poitras, V.J.; Gray, C.E.; Borghese, M.M.; Carson, V.; Chaput, J.P.; Janssen, I.; et al. Systematic Review of the Relationships between Objectively Measured Physical Activity and Health Indicators in School-Aged Children and Youth. Applied Physiology, Nutrition, and Metabolism 2016, 41, S197–S239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, L.M.; Lai, S.K.; Veldman, S.L.C.; Hardy, L.L.; Cliff, D.P.; Morgan, P.J.; Okely, A.D. Correlates of gross motor competence in children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Medicine 2016, 46, 1663–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holfelder, B.; Schott, N. Relationship of Fundamental Movement Skills and Physical Activity in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review. Psychology of Sport and Exercise 2014, 15, 382–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arufe-Giráldez, V.; Sanmiguel-Rodríguez, A.; Zurita-Ortega, F.; González-Valero, G. Gamification in physical education: A systematic review. Education Sciences 2022, 12, 540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, C.H.S.; Ha, A.S.C.; Lander, N.; Ng, J.Y.Y. Understanding the Teaching and Learning of Fundamental Movement Skills in the Primary Physical Education Setting: A Qualitative Study. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education 2022, 42, 621–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camacho-Sánchez, R.; Manzano-León, A.; Rodríguez-Ferrer, J.M.; Serna, J.; Lavega Burgués, P. Game Based Learning and Gamification in Physical Education: A Systematic Review. Education Sciences 2023, 13, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plass, J.L.; Homer, B.D.; Kinzer, C.K. Foundations of Game-Based Learning. Educational Psychologist 2015, 50, 258–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Jones, B.; Smith, J.J.; Morgan, P.; Eather, N. A Systematic Review Investigating the Effects of Implementing Game-Based Approaches in School-Based Physical Education among Primary School Children. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education 2023, 42, 573–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koehler, M.J.; Mishra, P. What Is Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge (TPACK)? Contemporary Issues in Technology and Teacher Education 2009, 9, 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subhash, S.; Cudney, E.A. Gamified Learning in Higher Education: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Computers in Human Behavior 2018, 87, 192–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, W.J.; Arjoranta, J.; Hitchens, M.; Peterson, J.; Torner, E.; Walton, J. Tabletop Role-Playing Games. In Role-Playing Game Studies: Transmedia Foundations; Deterding, S., Zagal, J.P., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 63–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.-Y.; Liang, J.-C.; Su, Y.-C. The Role of the TPACK in Game-Based Teaching: Does Instructional Sequence Matter? Asia-Pacific Education Researcher 2015, 24, 463–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, B.; Eynon, R. Historical Threads, Missing Links, and Future Directions in AI in Education. Learning, Media and Technology 2020, 45, 223–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brock, T. Roger Caillois and e-sports: On the problems of treating play as work. Games and Culture 2017, 12, 321–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caillois, R. Man, Play and Games (M. Barash, Trans.); Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Casey, A.; Goodyear, V.A.; Armour, K.M. Digital Technologies and Learning in Physical Education: Pedagogical Cases; Routledge: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Trust, T.; Krutka, D.G.; Carpenter, J.P. “Together We Are Better”: Professional Learning Networks for Teachers. Computers & Education 2016, 102, 15–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeves, T.C. Design Research from a Technology Perspective. In Educational Design Research; van den Akker, J., Gravemeijer, K., McKenney, S., Nieveen, N., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2006; pp. 52–66. [Google Scholar]

- Logan, S.W.; Webster, E.K.; Getchell, N.; Pfeiffer, K.A.; Robinson, L.E. Relationship between Fundamental Motor Skill Competence and Physical Activity during Childhood and Adolescence: A Systematic Review. Kinesiology Review 2015, 4, 416–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallahue, D.L.; Ozmun, J.C. Understanding Motor Development: Infants, Children, Adolescents, Adults, 6th ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Stodden, D.F.; Goodway, J.D.; Langendorfer, S.J.; Roberton, M.A.; Rudisill, M.E.; Garcia, C.; Garcia, L.E. A Developmental Perspective on the Role of Motor Skill Competence in Physical Activity: An Emergent Relationship. Quest 2008, 60, 290–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SHAPE America. National Physical Education Standards: Grade-Span Learning Indicators [PDF]; SHAPE America: Reston, VA, USA, 2024; Available online: https://www.shapeamerica.org/standards (accessed on 3 August 2025).

- Department for Education. National Curriculum in England: Physical Education Programmes of Study; 2013. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/national-curriculum-in-england-physical-education-programmes-of-study (accessed on 23 June 2025).

- Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority (ACARA). The Australian Curriculum: Health and Physical Education; 2022. Available online: https://v9.australiancurriculum.edu.au/ (accessed on 23 August 2025).

- Kirk, D. Physical Education Futures; Routledge: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Pacheco-Velázquez, E.; Rodés, V.; Salinas-Navarro, D. Developing Learning Skills through Game-Based Learning in Complex Scenarios: A Case in Undergraduate Logistics Education. Journal of Technology and Science Education 2024, 14, 169–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedwell, W.L.; Pavlas, D.; Heyne, K.; Lazzara, E.H.; Salas, E. Toward a taxonomy linking game attributes to learning: An empirical study. Simulation & Gaming 2012, 43, 729–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landers, R.N. Developing a Theory of Gamified Learning: Linking Serious Games and Gamification of Learning. Simulation & Gaming 2014, 45, 752–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garris, R.; Ahlers, R.; Driskell, J.E. Games, Motivation, and Learning: A Research and Practice Model. Simulation & Gaming 2002, 33, 441–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitzmann, T. A Meta-Analytic Examination of the Instructional Effectiveness of Computer-Based Simulation Games. Personnel Psychology 2011, 64, 489–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, F.-H.; Yu, K.-C.; Hsiao, H.-S. Exploring the Factors Influencing Learning Effectiveness in Digital Game-Based Learning. Journal of Educational Technology & Society 2012, 15, 240–250. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/jeductechsoci.15.3.240 (accessed on 23 June 2025).

- Mishra, P.; Koehler, M.J. Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge: A Framework for Teacher Knowledge. Teachers College Record 2006, 108, 1017–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shulman, L.S. Those Who Understand: Knowledge Growth in Teaching. Educational Researcher 1986, 15, 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koekoek, J.; van Hilvoorde, I. (Eds.) Digital Technology in Physical Education: Global Perspectives; Routledge: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modra, C.; Domokos, M.; Petracovschi, S. The Use of Digital Technologies in the Physical Education Lesson: A Systematic Analysis of Scientific Literature. Timisoara Physical Education and Rehabilitation Journal 2021, 14, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertmer, P.A.; Ottenbreit-Leftwich, A.T. Teacher Technology Change: How Knowledge, Confidence, Beliefs, and Culture Intersect. Journal of Research on Technology in Education 2010, 42, 255–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, M. Fell running and voluptuous panic: On Caillois and post-sport physical cultures. American Journal of Play 2011, 4, 100–120. [Google Scholar]

- Henricks, T.S. Caillois’s Man, Play, and Games: An Appreciation and Evaluation. American Journal of Play 2010, 3, 157–185. [Google Scholar]

- Sæther, S.; Borgen, J.S.; Leirhaug, P.E. Structuring Play in Physical Education. Sport, Education and Society 2023, 30, 88–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huizinga, J. Homo Ludens: A Study of the Play-Element in Culture; Routledge & Kegan Paul: London, UK, 1949. [Google Scholar]

- Suits, B. The Grasshopper: Games, Life and Utopia; Broadview Press: Peterborough, ON, Canada, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kretchmar, R.S. Practical Philosophy of Sport and Physical Activity, 2nd ed.; Human Kinetics: Champaign, IL, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Parlebas, P. Games, Sports and Society: A Lexicon of Motor Praxiology; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Salen, K.; Zimmerman, E. Rules of Play: Game Design Fundamentals; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Sargent, J.; Calderón, A. Technology-Enhanced Learning in Physical Education? A Critical Review of the Literature. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education 2021, 41, 689–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selwyn, N. Should Robots Replace Teachers? AI and the Future of Education; Polity: Cambridge, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Voogt, J.; Fisser, P.; Roblin, N.P.; Tondeur, J.; van Braak, J. Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge—A Review of the Literature. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning 2012, 29, 109–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A. Design Research in Education: A Practical Guide for Early Career Researchers; Routledge: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Barab, S.; Squire, K. Design-based research: Putting a stake in the ground. The Journal of the Learning Sciences 2004, 13, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, M.Q. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods, 3rd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Denzin, N.K. The Research Act: A Theoretical Introduction to Sociological Methods, 2nd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln, Y.S.; Guba, E.G. Naturalistic Inquiry; Sage: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Niess, M.L. Investigating TPACK: Knowledge Growth in Teaching with Technology. Journal of Educational Computing Research 2011, 44, 299–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, C.-S.; Koh, J.H.-L.; Tsai, C.-C. A Review of Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge. Educational Technology & Society 2013, 16, 31–51. [Google Scholar]

- Deterding, S.; Dixon, D.; Khaled, R.; Nacke, L. From Game Design Elements to Gamefulness: Defining Gamification. In Proceedings of the 15th International Academic MindTrek Conference: Envisioning Future Media Environments, Tampere, Finland, 28–30 September 2011; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Song, K.; Lockee, B.; Burton, J. Gamification in Learning and Education: Enjoy Learning Like Gaming; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina, F. La Enseñanza en la Educación Física: La Socialización, el Juego y las Emociones. Electronic Journal of Research in Educational Psychology 2012, 10, 755–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavega, P.; Alonso, J.I.; Etxebeste, J.; Lagardera, F.; March, J. Relationship between Traditional Games and the Intensity of Emotions Experienced by Participants. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport 2014, 85, 457–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rillo-Albert, A.; Sáez de Ocáriz, U.; Costes, A.; Lavega-Burgués, P. From Conflict to Socio-Emotional Well-Being. Application of the GIAM Model through Traditional Sporting Games. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínková, I.; Parry, J. An Introduction to the Phenomenological Study of Sport. Sport, Ethics and Philosophy 2011, 5, 185–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, R.; Marshall, J.; Mueller, F.F. Designing the Vertigo Experience: Vertigo as a Design Resource for Digital Bodily Play. In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Tangible, Embedded, and Embodied Interaction; ACM: Eindhoven, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 296–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, R.; Marshall, J.; Mueller, F.F. Designing Digital Vertigo Experiences. ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction 2020, 27, 296–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, S.; Andersen, M.; Roepstorff, A. Play, Reflection, and the Quest for Uncertainty. In Uncertainty: A Catalyst for Creativity, Learning and Development; Beghetto, R.A., Jaeger, G.J., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 37–55. [Google Scholar]

- Romero-Rodríguez, S.; Moreno-Morilla, C.; Muñoz-Villaraviz, D.; Resurrección-Pérez, M. Career Exploration as Social and Emotional Learning: A Collaborative Ethnography with Spanish Children from Low-Income Contexts. Education Sciences 2021, 11, 431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, X. Artificial Intelligence in Physical Education: Comprehensive Review and Future Teacher Training Strategies. Frontiers in Public Health 2024, 12, 1484848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).